Ethics Explainer: Vulnerability

In philosophy, vulnerability describes the ways in which people are less self-sufficient than they think.

It explains how factors beyond our control – like other people, events, and circumstances – can impact our ability to live our best lives. The implications of vulnerability for ethics are considerable and wide reaching.

Vulnerability isn’t a new idea. The ancient Greeks recognised tuche – luck – as a goddess with considerable power. Their plays often show how a person’s circumstances alter on the whim of the gods or a random twist of luck (or, if you like, a twist of fate).

This might seem obvious to many people. Of course, external events can affect our lives. If an air conditioning unit falls out of an apartment and lands on my head tomorrow, it’s going to change my circumstances pretty dramatically. But this isn’t the kind of luck philosophers argue is relevant to ethics.

A question of character

The Stoics, a group of ancient Greek philosophers (who are experiencing a revival today) thought only our own choices could affect our character or wellbeing. If I lose my job, my happiness is only affected if I choose to react to my new circumstances badly. The Stoics thought we could control our reactions and overcome our emotions.

The Stoics, much like Buddhist philosophy, thought our main problem was one of attachment. The more attached to external things – jobs, wealth, even loved ones – the more we risk suffering if we lose those things. Instead, they recommended we only be concerned with what we can control – our own personal virtue. For Stoics, we aren’t vulnerable because the only thing that matters can’t be taken away from us: our virtue.

Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant had similar thoughts. He believed the only thing that mattered for ethics was that we act with good will. Whatever happened to us or around us, so long as we act with the intention of fulfilling our duties, we’d be in the clear, ethically speaking. It’s our rational nature – our ability to think – that defines us ethically. And thinking is completely within our control.

Both Kant and the Stoics believed the ethical life was invulnerable. External circumstances, like luck or other people, couldn’t affect our ability to make good or bad choices. As a result, whether or not we are ethical is up to us.

Can one ever be self-sufficient?

This idea of self-sufficiency has faced challenges more recently. Many philosophers simply don’t think it’s possible to be self-sufficient to the degree that the Stoics and Kant believed. But some go further – seeing a measure of virtue in vulnerability. For example, vulnerability has become a popular term among psychologists and self-help gurus like Brené Brown. They argue vulnerability, dependency, and luck make up important parts of who we are.

Several thinkers, such as Bernard Williams, Thomas Nagel, and Martha Nussbaum have criticised the idea of self-sufficiency. Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, for example, argues that dependency is in our nature.

We’re all born completely dependent on other people and will reach a similar level of dependency if we live long enough. In the meantime, we’ll be somewhat independent but will still rely on other people for help, for community, and to give meaning to our lives.

MacIntyre thinks this is true even if Kant is right and rational adults are invulnerable to luck (at least in terms of choosing to do their duty). However, against Kant, MacIntyre argues that our capacity for rationality is honed by education and the quality of our education is often beyond our control… as we are dependent on the judgement and circumstances of our parents, society, and so on. Thus, we remain vulnerable in important ways.

Mutual vulnerability

Dr Simon Longstaff, the CEO of The Ethics Centre, has made a different argument in favour of vulnerability. He argues, after Thomas Hobbes, that the reality of mutual vulnerability lies at the heart of how and why we form social bonds. As a result, he argues those who seek to eliminate all forms of vulnerability risk creating a world in which the ‘invulnerable’ show no restraint in their treatment of the vulnerable.

All of this might seem like another academic debate but our understanding of vulnerability has significant consequences for the way we judge ourselves and others. If vulnerability matters, we’re less likely to judge people based on their circumstances. We won’t expect the poor always to lift themselves out of poverty (because unlucky circumstances may deny them the means to do so) nor assume every person struggling with an addiction is necessarily morally deficient. They may simply be stuck with the outcome of events that were (at least initially) beyond their control.

We may also be a little less self-congratulatory. Recognising the ways bad luck can affect people means also seeing how we’ve benefitted from good luck. Rather than assuming all our fortune is the product of hard work and personal virtue, we might be moved by vulnerability to acknowledge how factors beyond our control have worked in our favour.

Finally, vulnerability is one of the concepts that underpins modern debates about privilege and identity politics. If we think people are self-sufficient, we’re less likely to think past injustices have any effect on their present lives. However, if we think factors beyond our control can affect not just our lives but also our character and wellbeing, we might see the claims of minorities in a more open light.

There is a final sense in which vulnerability might be important to ethics. The ‘invulnerable’ person may come to believe their judgement is perfectly formed. They might become ‘immune to doubt’. If people open themselves to the possibility they might be wrong, they live an ‘examined life’ – that is, an ethical life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn denies women’s human rights

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The anti-diversity brigade is ruled by fear

The anti-diversity brigade is ruled by fear

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith The Ethics Centre 8 MAY 2017

To some men, the presence of a woman at work seems like an unexploded grenade, ticking away, just waiting to blow up their careers.

The Deputy US President, Mike Pence, famously refuses to eat alone with a woman who is not his wife for fear he may be “compromised”. His inspiration in this, the recently “departed” evangelist Billy Graham, even reportedly refused to be alone in a lift with one.

Since the tidal wave of #MeToo sexual harassment claims surged around the world’s workplaces over the past few months, there has been a backlash of complaints on mainstream and social media that men are now afraid that an act – that once seemed innocuous to them – would now return to destroy them.

Outside a function to raise support for Movember – a men’s health foundation – former INXS guitarist Kirk Pengilly vocalised the angst with this reply to a question about the sexual harassment allegations that fell movie producer Harvey Weinstein and gardening TV star Don Burke:

“I really loved the ’60s and ’70s when life was so simple and you could slap a woman on the butt and it was taken as a compliment, not as sexual harassment.”

Diversity initiatives have also attracted their share of pushback. Google recently fired an engineer who wrote a 10 page memo against the company’s affirmative action programs. The engineer has now filed a lawsuit alleging discrimination against white people, men and political conservatives.

The engineer claimed women are underrepresented in the tech industry “largely because of their innate biological differences from men – their ‘stronger interest in people rather than things’, their propensity for ‘neuroticism’, their higher levels of anxiety”.

How nervous are they?

Does this backlash indicate that men are becoming afraid of women, as some media reports claim? That women now have too much power and an inclination to take men’s jobs? Just how nervous are they?

One of Australia’s foremost experts on men and masculinity, Dr Michael Flood, says speculation about men’s growing trepidation around women has been overstated.

“For many men, the primary reaction has been one of disinterest. They don’t see the these as issues of direct concern to them”, says Flood, a sociologist and associate professor at the Queensland University of Technology School of Justice.

Flood’s research shows that men are widely supportive of gender equality initiatives, however, they are also less likely than women to recognise discrimination when it occurs.

Fewer than one third of women in Australia think men and women are treated equally at work, compared with 50 percent of men who said the same, according to the Australian Women’s Working Futures 2017 report from the University of Sydney.

Belief of false accusations

Despite the overwhelming support for the idea of equality, some men find the new workplace gender politics threatening.

“I think [#MeToo] is going to push some men’s buttons. I think there is a widespread perception, a false perception, that women make up allegations of sexual harassment and that draws on a very old stereotype of the lying, vindictive woman – a very long standing sexist stereotype”, Flood says.

“And so that belief that false accusations of domestic violence and sexual assault are common, then plays itself out in fears about men being falsely accused of sexual harassment.”

False reporting of rape and sexual assault are between two percent and six percent in the UK, Europe, and the US.

US sociologist and masculinity researcher Dr Michael Kimmel, says Mike Pence’s solution makes him the “American equivalent of the Taliban”.

The logic is that women are so tempting and that men are so incapable of control, they cannot be trusted to interact in the workplace, says Kimmel, Distinguished Professor of Sociology at the Stony Brook University in New York and author of Angry White Men: American Masculinity at the End of an Era.

“This is a way of punishing women for men’s predatory behaviour. It is just evangelical Talibanism.”

Punishing women for men’s behaviour

Kimmel says he has heard men in companies claim that the situation is so perilous they will not hire a woman, go to a meeting with a woman, have a meal or a drink with a woman in case they are accused of sexual harassment.

“My analogy to this is the crazy straight guys who are afraid that every gay guy is going to hit on them. It is not going to happen. You are just not that interesting”, he says.

Kimmel says he also hears from men that they do not know what to do, are worried about saying the wrong thing or feel like they are “walking on eggshells” in their interactions with women.

“I regard this as relatively good news because what most men are saying is, ‘I don’t want to be a jerk. I don’t know what the right thing to do is anymore, but I don’t want to do the wrong one’.”

“That is a good start.”

Flood agrees, saying he welcomes the fact that many men are asking themselves some difficult questions about how they treat women.

“I think that is probably, in some, leading to more respectful, more equitable and more enjoyable relations among women and men in workplaces.”

Kimmel takes some comfort from research that shows younger men are savvier about what is acceptable behaviour around women in the workplace.

“The rules have changed. The old Don Draper [1950s Mad Men] rules no longer apply and many of us, who are aged 60 and above, were raised on those Don Draper rules and so we kind of don’t know what to do now.

“Age is a missing variable in the conversation and it needs to be discussed.”

However, this is not to say that older men cannot adapt. “I think we don’t give men enough credit sometimes. Most of us have adapted [to the new rules] just fine. Why? Because we actually like it. It is better.”

Flood cautions that it is important not to dismiss the trepidation of those who do feel threatened.

“We need to listen to men’s fear and work with it, but that doesn’t mean we give it a space or legitimacy that it doesn’t deserve”, he says.

If those fears are not dealt with, those men tend to “dig themselves in to resistance and defensiveness”.

Kimmel says we are now in a transitional period where neither men or women are comfortable in the workplace.

“The reason I am so sanguine about this is because I know young people. Young people are coming into the workplace and they already know the rules have changed.

“The Millennials are far more equal when they come in, they are far more capable of working in teams, they have far more cross-sex friendships. Yes, it is going to be discomforting – we all understand that – but I also think it is going to be fine.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Accepting sponsorship without selling your soul

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is debt learnt behaviour?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Is technology destroying your workplace culture?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAY 2017

If you’ve read the Harry Potter series – and let’s face it, many of us have – you will have gained insight into a number of things: the value of friendship, the nature of heroism, the redeeming power of love… the list goes on.

But amidst all the magic, there’s one lesson you might have missed – a lesson which is crucial to the way we think and talk about ethics. In Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Harry is able to secure the titular stone and keep it away from the villainous Voldemort for one simple reason. Even though the stone is powerful, Harry has no desire to use it.

Genius wizard Dumbledore protects the stone with an enchantment. Any person who wanted to use the stone to become immortal would never be able to access it. Only someone who wanted the stone for the right reasons would be successful. The benefits, in other words, were only available to people who didn’t want them.

If your only reasons for committing to ethics are external – because of what ethics will give you – then your motivation will come and go.

Working in ethics, it’s tempting to present the external benefits the ethical life provides to people. In convincing people to set aside self interest and do what’s right, we sometimes appeal to people’s self interest. We use the very logic we’re trying to unwind.

For example, we convince a business to take ethics seriously because it’ll enable them to recruit and keep better staff (it does). We tell a person that living ethically is more likely to make them popular, employable and happy, which it might.

The problem is, if we’re serious about getting people to live ethically, even if we win the argument, we’ve failed in achieving our goal. As soon as someone commits to acting ethically for instrumental reasons – to make money, become popular or whatever – they’re no longer doing it because they think it’s right, they’re doing it because they think it’s effective.

This is a problem. If your only reasons for committing to ethics are external – because of what ethics will give you – then your motivation will come and go. The moment ethics doesn’t help you keep staff or stay popular, your reasons for committing to living an ethical disappear.

Genuine ethical behaviour isn’t only about doing the right thing, it’s about doing it for the right reasons. It means doing what’s ethical because it’s ethical, not because it’ll give us some other advantages.

The debates around torture are a good example of this. Recently, many opponents to torture have argued ‘torture doesn’t work’, so we shouldn’t do it. But this suggests that if torture did work, we wouldn’t have any problem with it. The logic of the argument supports abandoning torture but it also supports undertaking further research to find forms of torture that do work.

But the ethical argument against torture isn’t that it doesn’t work, it’s that even if it did work, it would be wrong. In whatever walk of life you apply it, ethical demands are at their strongest when they force you to choose between what’s beneficial and what’s right.

When someone starts to use the language of ethics to pursue their own ends, they often reveal themselves through hypocrisy. Often, they abandon their so-called values when the costs get too high.

It’s easy to do the right thing when it benefits you. Ethics asks you to set aside what’s convenient, profitable or comfortable and do what’s right. Genuine ethical behaviour isn’t only about doing the right thing, it’s about doing it for the right reasons. It means doing what’s ethical because it’s ethical, not because it’ll give us some other advantages.

In short, ethics is a totally different language to that of self interest, efficiency or effectiveness. It uses different arguments, demands a different kind of thinking and asks us to reconsider our priorities.

It’s only those who are authentically committed to ethics for its own sake who inspire support and trust in the long term.

The reason this is tricky for ethicists is because ethics is a Philosopher’s Stone of sorts. It does offer lots of benefits. But like the enchanted stone in Harry Potter, these benefits are only available to the people for whom ethics isn’t about achieving them.

People value authenticity and loathe hypocrisy. When someone starts to use the language of ethics to pursue their own ends, they often reveal themselves through hypocrisy. Often they abandon their so called values when the costs get too high. When this happens, the good will and support offered by others will disappear.

It’s only those who are authentically committed to ethics for its own sake who inspire support and trust in the long term. Like the magic stone, the benefits of ethics don’t come to those who seek them, they are given to those who deserve them.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Stopping domestic violence means rethinking masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Trust

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

United Airlines shows it’s time to reframe the conversation about ethics

United Airlines shows it’s time to reframe the conversation about ethics

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 5 MAY 2017

Have you ever felt like the kind of person who people always go to for advice but never invite out for drinks?

It’s not a lot of fun being the friend they turn to in bad times and the one they forget to call when the going’s good.

Imagine how ethicists feel.

Most people think of ethics when something goes awry, when people don’t know what to do or when someone’s done the wrong thing. Just like the advice-giving friend, ethicists are useful when stuff’s gone wrong but they’re also worth chatting to when things are going well.

It’s true, ethics – and ethicists – helps in those kinds of situations. But the association between ethics and negative circumstances is restrictive. It prevents people from looking for ethical issues before circumstances force them to do so.

This isn’t a campaign for an ‘International Hug an Ethicist Day’ (although it’d be nice). We just want to show how ethics can create meaning and value in the world.

Take the case of United Airlines. Dr David Dao was dragged off an overbooked flight after refusing to give up his seat. United offered hotel rooms and cash to encourage people to volunteer their spot but nobody took the bait. Dao and three other passengers were then randomly chosen and reassigned to another flight.

You don’t need to wait for something to go wrong to check whether you’ve got your ethical house in order.

Dao claimed he had patients to see the next day and refused to move. Video footage emerged of officers dragging him off the plane with a bloodied face. As it turns out, the reason United had to remove passengers was to create space for their own employees.

The reaction was huge. #BoycottUnitedAirlines trended on Twitter and United lost $1.4 billion dollars in share value.

After initially standing firm, United CEO Oscar Munoz apologised on behalf of the airline. The two parties reached a legal settlement. Policies were changed to ensure this wouldn’t happen again. Not long afterward, Munoz sent an email to customers, explaining how it had happened:

It happened because our corporate policies were placed ahead of our shared values. Our procedures got in the way of our employees doing what they know is right.

This isn’t uncommon. Indeed, it’s a danger many organisations and people risk falling into. That United have reached this conclusion and acknowledged it publicly is a step in the right direction.

What is unfortunate is that it took such an unpleasant and commercially damaging incident – not to mention Dao’s suffering – for them to get here. You don’t need to wait for something to go wrong to check whether you’ve got your ethical house in order.

Those who think proactively about ethics are more able to anticipate and overcome challenges. They create a culture where employees regularly flex their ‘ethical muscles’ and are given the freedom to do so.

Engaging in ethics is a proactive process. It’s about identifying what you stand for, what you want to achieve and the right way to do it. At least, it can be.

Instead, it’s often invoked reactively, trying to identify what went wrong and how it can be avoided in the future.

Prevention is better than a cure. Those who think proactively about ethics are better able to anticipate and overcome challenges. They create a culture where employees regularly flex their ‘ethical muscles’ and are given the freedom to do so. Instead of deferring to abstract policies, they’re able to use their judgement to do what’s right according to what the organisation stands for.

This is important considering United’s response. Munoz emphasises the steps United have taken to change their policies to prevent anyone from being thrown off a flight again. But he said the heavy role of company rules was the problem to begin with, saying “our corporate policies were placed ahead of our shared values”.

It’s tempting to think the solution to ethical failure is more rules and stricter codes of conduct. While it’s true sometimes bad policy will be responsible for unethical behaviour, oftentimes more rules can make the problem worse.

Rulebooks are external tools for regulating behaviour. Even though people might be doing the right thing, their capacity to reflect on how they should live can diminish because their ‘ethical muscles’ aren’t strong. Rules and policies can relieve you from thinking about what to do because you can just follow orders and do it.

Our executive director Simon Longstaff explains this with an analogy. If you put someone in a full plaster cast, they’ll stand up straight. However, inside the cast their body will become weaker and weaker until they can’t stand up on their own. Eventually, when the cast comes off or is damaged, they’ll crumple in a heap.

All of this reveals the need to reframe the way we think about ethics. Instead of being about stopping what’s bad, think of it as creating something good.

Relying only on policies to govern behaviour has a similar unintentional weakening effect. Longstaff explains such a system increases risk to itself by reducing the capacity of any single actor to make good decisions when the things are working exactly as they should.

All of this reveals the need to reframe the way we think about ethics. Instead of being about stopping what’s bad, think of it as creating something good.

Encouragingly, there is some evidence United are moving in this direction. As well as acknowledging the need to prevent similar failures in future, Munoz takes the time to imagine a more proactive, ethical role for United:

I believe we must go further in redefining what United’s corporate citizenship looks like in our society. If our chief good as a company is only getting you to and from your destination, that would show a lack of moral imagination on our part. You can and ought to expect more from us, and we intend to live up to those higher expectations in the way we embody social responsibility and civic leadership everywhere we operate.

Of course, as with any commitment to ethical change, words must be followed with action. Yet these sentiments signify a possible shift in the way United thinks about ethics itself. Not only as a way of avoiding bad decisions but as a way of imagining and creating a better organisation and contributing to a better world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Following a year of scandals, what’s the future for boards?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Business + Leadership

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 2 MAY 2017

Kwame Anthony Appiah (1954-current) is a British born, American-Ghanaian philosopher.

He is best known for his work on cosmopolitanism, a philosophy that holds all human beings as members of a single, global community. A professor of philosophy and law at New York University, he also writes the popular everyday advice column ‘The Ethicist’ in the New York Times.

We’re responsible for every human being

Because Appiah is a cosmopolitan (meaning “citizen of the world”), he believes we have just as much moral responsibility to our neighbours as we do those halfway across the world. Our obligations to other people transcend national borders, the same way they bypass political ideas and religious beliefs.

However, these obligations shouldn’t mean treating yourself unjustly. Appiah doesn’t advocate for giving everything away so you are worse off than the people you are trying to help.

By focussing too much on eliminating everything bad from the world, Appiah worries we’d fulfil our duties to others at the expense of our duties to ourselves. We’d let go of everything that makes life worth living and meaningful.

He also thinks we’re more productive when we work together. He sees our duties to others as collective rather than individual. The best way to help other people is to unite and ensure nations can provide citizens with what they need to live a good life. This means working with international aid organisations and governments. We’re all in this together.

What unites us is stronger than what divides us

For Appiah, the other basic principle of cosmopolitanism is valuing people’s differences.

“Because there are so many human possibilities worth exploring, we neither expect nor demand that every person or every society should converge on a single mode of life.”

It’s not enough to campaign for international human rights for everyone. These matter, but we should also care about the specific things that give people’s lives meaning – culture, religion, art and so on.

Besides, underneath cultural differences are often shared values and practices. Whether it’s art, friendship, norms of respect or a belief in good and evil, the things that seem so different are often based in ideas we all share.

Moral progress isn’t made by argument

In The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen Appiah argues that seriously unjust practices aren’t defeated by new moral arguments. Instead, they’re defeated by changing attitudes about what’s honourable or shameful.

Appiah points to the overthrow of slavery in Britain and the US as being largely a product of honour. Even though slave owners and traders were aware of moral arguments defending the humanity of their so called stock, that didn’t provide the impetus to change. What really overthrew it was public criticism. The appeal to honour had far more influence than any moral and philosophical ideals.

We can see honour as the middle ground between narrow self interest and self sacrificing altruism. Appiah’s point is a powerful one for people wanting to make change in the world. It would be great if everyone did the right thing for its own sake but sometimes we need a push. Honour, praise and shame can be just the thing.

It’s important to note Appiah thinks honour and ethics are separate. What is seen as honourable isn’t always the same as what’s right. Killing someone in defence of your honour is one clear example.

What’s more, as anyone who has ever logged onto Twitter knows, praise and shame can be abused. Because they are so effective at changing people’s behaviour, it’s tempting to use them when it’s entirely inappropriate. And sometimes this has disastrous effects.

The deeper point is we aren’t purely rational creatures. We work on emotion and our thoughts and actions are driven by cultural attitudes and judgements.

Being aware of this means we might be able harness our communal nature as a force for good and speak both to people’s heads and hearts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ad Hominem Fallacy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Now is the time to talk about the Voice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Pat Stokes The Ethics Centre 26 APR 2017

‘Identity politics’, much like ‘political correctness’, is being battered in the public square.

Rather than becoming a serious category of political critique, its obscurity of meaning makes it a useful tool for opposing political ideologies. It is used as a pejorative for the political left and, at the same time, as a euphemism for white supremacy (‘white identity’). Now, even notionally left-leaning figures have started railing against identity politics, calling it divisive.

The hackneyed left/right distinction will not help us to understand the debate over identity politics. Indeed, this conflict may well reflect and reveal deep, structural features of what it is to be a human.

What is identity politics?

Identity politics seeks to give political weight to the ways in which particular groups are marginalised by the structures of society. To be a woman, a person of colour, transgender or Indigenous is to be born into a set of social meanings and power relations that constrain what sort of life is possible for you.

Your experience of the world will be conditioned in very different ways from those on the other side of social power. Identity politics, at its simplest, is an attempt to expose and respond politically to this reality.

Importantly, identity politics has always been a reaction to liberalism, although both frameworks have the same end goals of equality and ending oppression. A liberal approach to social justice sees the demand for political equality as emanating from a shared human dignity. As such, it de-emphasises difference. If only we look past the superficial things that divide us, we’re told, we see a common humanity. It washes away any justifications for discrimination on the basis of race, gender or orientation.

But liberalism can tend to mask the circumstances that make us need liberating in the first place. By focusing on universalism – the ways in which you and I are the same – I may well become more aware of our shared human equality and less sensitive to how different our lived experiences may be. So the forms of privilege I enjoy and you lack remain invisible to me.

Liberalism at its most strident treats every person as a sort of abstract locus of radical freedom and rationality. Identity politics resists that abstraction – an abstraction which, as identity politics points out, implicitly serves those on the privileged end of power imbalances. In doing so, liberalism makes it harder for us to see and dismantle the structures that perpetuate inequality.

The real gulf here isn’t between left and right or between minority and majority, it’s between two conceptions of how human beings stand in relation to their historical and cultural background. Are we defined by our place within society or do we somehow transcend it?

The philosophy of identity

“What are we?” should be the simplest question to answer, yet it is one of the most annoyingly intractable problems in philosophy. Are we minded animals or embodied minds? Are we souls? Bodies? Brains? Particular bits of brains? All of these answers have been tried, and all answer some of our everyday assumptions about personal identity while running afoul of others.

What they all have in common is they treat selves or persons as a type of object. They all regard the person from a third-person perspective. That’s the perspective we take on other people all the time, both in our everyday interactions and in trying to influence human behaviour via psychology, medicine, marketing, politics and so on. And we can take a third-person perspective on ourselves, too. Whenever you ask, “Why did I act like that?” you’re viewing yourself as an object and wondering what forces made you act one way instead of another.

Yet in your self-reflection you never, to borrow a phrase from Jean-Paul Sartre, ‘coincide’ with yourself. You view yourself as an object. Just by doing that you go beyond yourself, make yourself something different to the self you’re contemplating. Just as the eye can never catch sight of itself (but only, at best, a reflection of itself), you can only see yourself by being something more than yourself, so to speak.

You detach from all that you are – your history, your memory, your character – in order to observe yourself. That ability to detach is precisely what makes reflective endorsement or rejection of your concrete identity possible at all.

So which one are we? The observer or the observed? The object we contemplate in a field of other objects and forces – a mass of psychological drives subject to cause and effect – or the conscious subject that somehow detaches from all that? The answer has to be ‘both’. We are pretty clearly physical objects, prone to various forms of constraint, influence and control.

Yet we cannot simply disavow our past, our language or the identities society imposes on us either. But we are also something more, something that can step back from what we are, something that appears to itself as free. We’re doomed to be both these things. Our destiny is internal division.

Making sense of the identity politics debate

How does any of this relate to the issue of identity politics? Well, consider the two political anthropologies sketched above – one view says we’re constrained by the identities we find ourselves born or built into, the other that we’re all free, rational, autonomous agents.

These are exaggerations of course – most liberals don’t think we’re completely unaffected by our social situation and most proponents of identity politics don’t think we’re completely lacking in autonomy. But they pick out a genuine point of disagreement.

Both identity politics and universalism answer different but real dimensions of human existence.

One way to think of that disagreement is as a clash between the type of self we might take ourselves to be – as an object determined by history and society, or as a free, undetached locus of consciousness. That is not the whole story, but it opens up one useful way to think about it. Both identity politics and universalism answer to different but real dimensions of human existence.

Rather than simply insisting on one approach to the complete exclusion of the other, we should consider how both might be responses to irreducible and contradictory aspects of what we are.

The question is where we go from there.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Sunlight Test

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If you condemn homosexuals, are you betraying Jesus?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Freedom and disagreement: How we move forward

BY Pat Stokes

Dr Patrick Stokes is a senior lecturer in Philosophy at Deakin University. Follow him on Twitter – @patstokes.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Easter and the humility revolution

Easter and the humility revolution

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Natasha Moore The Ethics Centre 13 APR 2017

Whether you’re sceptical there’s a man upstairs, are a lapsed Christian, or have another faith, you’re likely to be celebrating Easter. You might swap church for chocolate and paid leave, but it’s a celebration nonetheless.

For people who believe Jesus is the Son of God, the next few days mark the most important time of the year. From Holy Thursday to Easter Sunday, Christians will reflect on the death and resurrection of Christ.

It’s a story that “transformed the world we live in” according to Natasha Moore, research fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity. Moore says some of the character traits we value so highly today have their origins in what is said to have happened in those few days in Jerusalem. She takes us through the significance of Easter.

Humility: “Your Lord and teacher has washed your feet”

“The big one is humility”, Moore explains. “The fact that we today value humility and we think about leadership as service to those under your power – we trace that back entirely to Jesus.”

This all stems from the central message of Easter and of Christianity itself: God became a man and allowed himself to be killed to redeem humanity.

This was revolutionary when you compare it to the prevailing ideas about power and leadership at the time.

We have to think differently about hierarchy, privilege, power, service, leadership, and all those things.

Before Christianity, there was no real sense that humility was a virtue. Although the Ancient Greeks had a sense of hubris – excessive pride that would be punished by the gods – there was still a firm emphasis on achievement, power and status as the ways to determine someone’s moral worth.

“In the ancient world, humility was indistinguishable from humiliation … It would be horrifying that someone with power would come down to the level of someone below them,” says Moore. “If our god could submit to death and even a shameful death [like crucifixion] … we have to think differently about hierarchy, privilege, power, service, leadership and all those things.”

Tonight, priests at local parishes all the way up to the Pope himself will try to recreate these lessons. They will humble themselves by washing the feet of their congregation members.

“You see someone like the Pope doing that – power voluntarily lowering itself – and there’s something really compelling about that still,” says Moore.

Reflections on humility, service and leadership today seem appropriate. In Australia, there have been challenges posed to politicians around their use of entitlements and whether they’re being used to serve the community. We’ve witnessed populist political campaigns trying to take down ‘the elite’, suggesting the time is right for a robust conversation on what it means to lead.

Gratitude: “Give thanks to the Lord”

One of the more striking differences between the messages in the Easter story and our modern values is how people feel about being in debt. For most of us, debt is a bad thing. Whether financial or otherwise, we feel uncomfortable when we owe somebody something.

Writer Erin Joy Henry gives voice to this tendency, as she recalls declining help when moving houses despite feeling completely overwhelmed. “I didn’t want to feel that I owed anyone anything, and I constantly needed to prove to myself that I was completely self-sufficient,” she says.

Easter is a time when Christians reflect and give thanks for a debt they could never repay. They believe humanity could never redeem itself from its past sins. Instead, Jesus came to Earth and “wiped the slate clean” on behalf of humanity. “That leaves us with a massive debt of gratitude”, Moore says.

We are completely interdependent on so many other humans and so many other human activities.

This state of debt runs deep for Christians. “If God has created us, if every breath we breathe is his air into the lungs he’s given us, we owe God from the start,” Moore explains.

There’s a universal truth here. The idea of self-sufficiency is “by and large, an illusion”.

Despite the value we place on independence and autonomy, Moore thinks “we are completely interdependent on so many other humans and so many other human activities”.

Instead of avoiding debts and trying to live independently, she thinks we should lean in to interdependence and be thankful for the support we receive.

“Gratitude is an impulse that makes us happier and healthier. It’s how we’re made. I don’t think there’s a downside.

Non-violence: “He who lives by the sword dies by the sword”

“Jesus up-ended hierarchies but he also up-ended conflict … Instead of responding to violence and hostility in kind, he counselled his followers to turn the other cheek, go the extra mile and to love their enemies,” says Moore.

Although this seems “counterintuitive and incredible difficult to do,” there’s evidence to suggest it’s effective.

In Why Civil Resistance Works, researchers Maria J. Stephan and Erica Chenoweth studied a range of activist movements between 1900 and 2006. Moore summarises their findings and says that “non-violent resistance is twice as effective as violence in achieving the goals of the campaign.”

This non-violent approach has often been criticised. Many think by refusing to fight injustice, we allow it to prosper. As Barack Obama said while accepting the Nobel Peace Prize, “A non-violent movement could not have halted Hitler’s armies. Negotiations cannot convince Al-Qaeda’s leaders to lay down their arms.”

For Moore, the evidence says something different. “That sort of action can be really powerful and challenge injustice in a way violent resistance doesn’t necessarily achieve”.

It also has important lessons today. We are increasingly hostile in dealing with disagreement. From debates around punching political opponents in the face to the general tone of online discussions, perhaps non-violence is the path forward.

“Is there a way to respond to abuse and hostility online in ways that break the cycle of outrage, criticising and abusing one another?” Moore asks.

“Jesus really offers a model – you have to break that cycle”.

Reading the story today

“I would encourage somebody who isn’t religious to read the story, because it’s so culturally significant,” says Moore. However, she cautions against seeing Easter as a fictional story. It matters historically and theologically that people believe Jesus was God.

“He wouldn’t have upended the hierarchies of the ancient world and made us think the poor and the despised and the executed are still people who are immeasurably valuable … if we didn’t think he was God.”

This doesn’t mean we have to convert to the faith to get any meaning out of the story, but it might require us to be open to all possibilities.

“The story is open to anybody. It invites us to figure out what we think.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Now is the time to talk about the Voice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

BY Natasha Moore

Dr Natasha Moore is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity. She has a PhD in English Literature from the University of Cambridge.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: John Rawls

Is there a way to really get our societies to be fair for everyone?

This was the question John Rawls (1921-2002), American political philosopher and author of A Theory of Justice, attempted to answer. His work centres on social justice, privilege, and the distribution of resources in a society.

Rawl’s cake

Imagine it’s your birthday. Your parents decide to throw a party for you and your friends. When it’s time to cut the cake, your mother tells you, “You can cut the cake in whatever way you want to but you can’t choose the slice that you’ll get to have”.

Maybe you’d like a bigger slice of that cake. But since you don’t want to risk getting a small slice, you decide to cut equal sizes for everyone. Now you and your friends are happily munching away, knowing the cake was distributed as fairly as possible.

Fairness demands ignorance

Rawls thought most people’s definition of justice reflected what was good for them instead of anything shared or universal. You might think justice means owning the resources you’ve inherited, or you might think justice is about redistributing them. Whether intentionally or not, we all define justice in a way that gets us a little higher on the ladder. (Big slice for you, small slice for everyone else.)

To get to the core of things, Rawls asks us to imagine a situation where society doesn’t exist yet and no one knows where they will end up in life. What kind of society would you join knowing you could be somehow disadvantaged? If you entered this new world with no parents from childhood, a physical disability, intellectual impairment, financial hardship, or no access to school, what would you want it to be like?

If we each play along with Rawl’s hypothetical, we are likely to imagine fairness in a particular way. Rawls thought we would only join a society where everyone, no matter what circumstances we were born in, has their needs met.

Inequality needs to benefit everybody

Rawls’ conception of justice was based on society’s equal distribution of resources according to two principles.

The first principle is the equality principle. This says everyone should have access to the broadest possible range of civil liberties. Here the only limitation on our freedoms is what is necessary to give other people the same level of freedom. For this system to be fair, you can only be as free as everyone else.

The second principle is the difference principle. Any inequalities in society are only justified under two conditions:

1. There must be equality of opportunity. If there are going to be inequalities – like some people earning more money than others – they should be available to everyone. For example, if access to education increases people’s earning capacity, everyone should have the same access to education so everyone has the same chance to grow their wealth.

2. If there are any social disadvantages, they need to benefit the least advantaged people most. Rawls thought we should only be permitted to grow our personal wealth if we used it to benefit the poor. He wanted to keep the socioeconomically disadvantaged within a reasonable distance of the financially elite by redistributing resources. This was what he saw to be the fairest possible system.

If we were to imagine what the difference principle might look like in practice, it could be policies permitting people to leave inheritance to their children if the state is allowed to tax and distribute it to the poor.

Rawls’ challenge for political philosophy is to question whether a merit based system is as fair as people think. Was it only your work that got you to where you are today or did luck also play a role? If it was the latter, what does that tell us about justice?

Be consistent

Rawls was dedicated to finding the most reasonable political system possible. He believed the first step was to fill our parliaments with reasonable people. It might sound like a no brainer, but by reasonable he meant those with consistency and coherence between their various opinions and beliefs. He called this “reflective equilibrium”.

Imagine someone believes if employees do the same work, they should receive the same wage. Imagine they also opposed striving for pay parity between men and women. Rawls would say this person’s political beliefs are incompatible and therefore unreasonable. To achieve reflective equilibrium, one of these views will have to shift.

In fact, Rawls thought achieving genuine reflective equilibrium was impossible. Instead, we should try to get as near as we can to perfect synergy.

For those of us interested in ethics and politics, the reflective equilibrium is an important idea. We often form opinions based on gut reaction, instinct, or by focussing on the specifics of a situation.

Each of these approaches can at times be unreasonable and inconsistent. By forcing us to test how our different beliefs fit together, Rawls encourages us to do something very basic but very important: make sure our set of beliefs make sense.

First published March 2017. Updated August 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Berejiklian Conflict

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY The Ethics Centre 1 MAR 2017

“Find a job you’ll love and you’ll never work a day in your life!” There are different claims about who coined this phrase but it’s stood the test of time. Like most one-liners, it’s easier said than done.

Most people need two things from their work. They need to earn enough to support all the other areas of their life and they need to feel dignified while doing it. Neither is an easy find.

We tend to know how much income we need but a sense of dignity and meaning can be elusive. You might want creative output, a good work/life balance or a sense of achievement earned through a ‘hard day’s work’. It’s easier to know what kind of work will suit you if you’ve taken Socrates’ advice: know thyself.

Still, insights from philosophy and psychology can help us spot some of the things that tend to give people a sense of meaning in their jobs.

You’ve gotta want it

This is the basic idea behind the ‘find a job you love’ proverb. If you’re doing something you enjoy, it won’t feel like a chore. If you’re motivated by income, prestige or something external, it will be hard to find the work itself fulfilling.

The philosopher Bernard Williams distinguishes ‘internal’ and ‘external’ motivations. We have an external motivation to do something if it would be good for us to do it, whether we want to or not. Internal motivations are things we personally want to do.

For example, if we’re sick, it is good for us to take medicine – that’s an external motivation. If we actually want to get better, we’ve also got an internal motivation. If we want a few more days off work, there’s no internal motive to get better, even though being healthy is better than being sick, generally speaking.

Williams thought external motivations alone couldn’t make us do something. We need some internal motivators to get us off the couch. Williams might not be right. Lots of people probably show up to work because they need to make ends meet but there’s still a lesson in his distinction. Salaries, prestige or fringe benefits won’t be enough to give us a lasting sense of meaning – we need to feel personally engaged with what we’re doing.

Look beyond official duties

Sometimes the core activities of our work won’t give us internal motivation. It might be some unofficial role our job enables us to fulfil.

Psychologist Barry Schwartz uses the example of Luke, a hospital janitor (his official title was “hospital custodian”). It’s unlikely Luke wakes up passionate about working light bulbs and shiny urinals. He found meaning in the parts of his work that extended beyond his official duties:

“The researchers asked the custodians to talk about their jobs, and the custodians began to tell them stories about what they did. Luke’s stories told them that his “official” duties were only one part of his real job, and that another central part of his job was to make the patients and their families feel comfortable, to cheer them up when they were down, to encourage them and divert them from their pain and fear, and to give them a willing ear if they felt like talking.”

The meaningful work Luke performed sat outside he things the hospital paid him for. Despite this, it still gave him enough satisfaction to keep showing up.

See your role in the bigger picture

Hospital janitors are a font of wisdom. Schwartz also describes how Ben and Corey, also janitors, found meaning. They recognised their role within the broader purpose of the hospital – to provide care for people who need it:

“Luke, Ben, and Corey were not generic custodians. They were hospital custodians. They saw themselves as playing an important role in an institution whose aim is to see to the care and welfare of patients.”

They would stop mopping floors if patients were walking the corridors for rehab or hold off from vacuuming when family were sleeping in the patient lounge. They weren’t just keeping things tidy and in working order. In a hospital, cleanliness staves off infection and can save lives. The context and purpose of their work gave it new meaning.

Find space for choice

Peter Cochrane, entrepreneur and technologist, thinks many jobs are taking what’s human out of their human employees. In the documentary The Future of Work and Death, he says, “When I go into companies I often ask the question, ‘Why are you employing people? You could get monkeys or robots to do this job.’ The people are not allowed to think – they are processing. They’re just like a machine.”

At an absolute minimum, feeling dignified at work means feeling like our humanity is being recognised. We want to be treated as people, not things. It’s important we find spaces in our work where we can be autonomous: making decisions for ourselves, exercising our creativity and asserting our ability to think freely.

It’s not a perfect fix

We must acknowledge the limitations of this advice. Our basic needs for food, housing, and the rest require many of us to persevere with work we find undignifying or meaningless.

But if you’re lucky enough to enjoy some choice in where you work and are unhappy in your current role, take a second to think – are you missing one of the above? At least you’ll know what to look for next time!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Teachers, moral injury and a cry for fierce compassion

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Volt Bank: Creating a lasting cultural impact

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ask the ethicist: Is it ok to tell a lie if the recipient is complicit?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

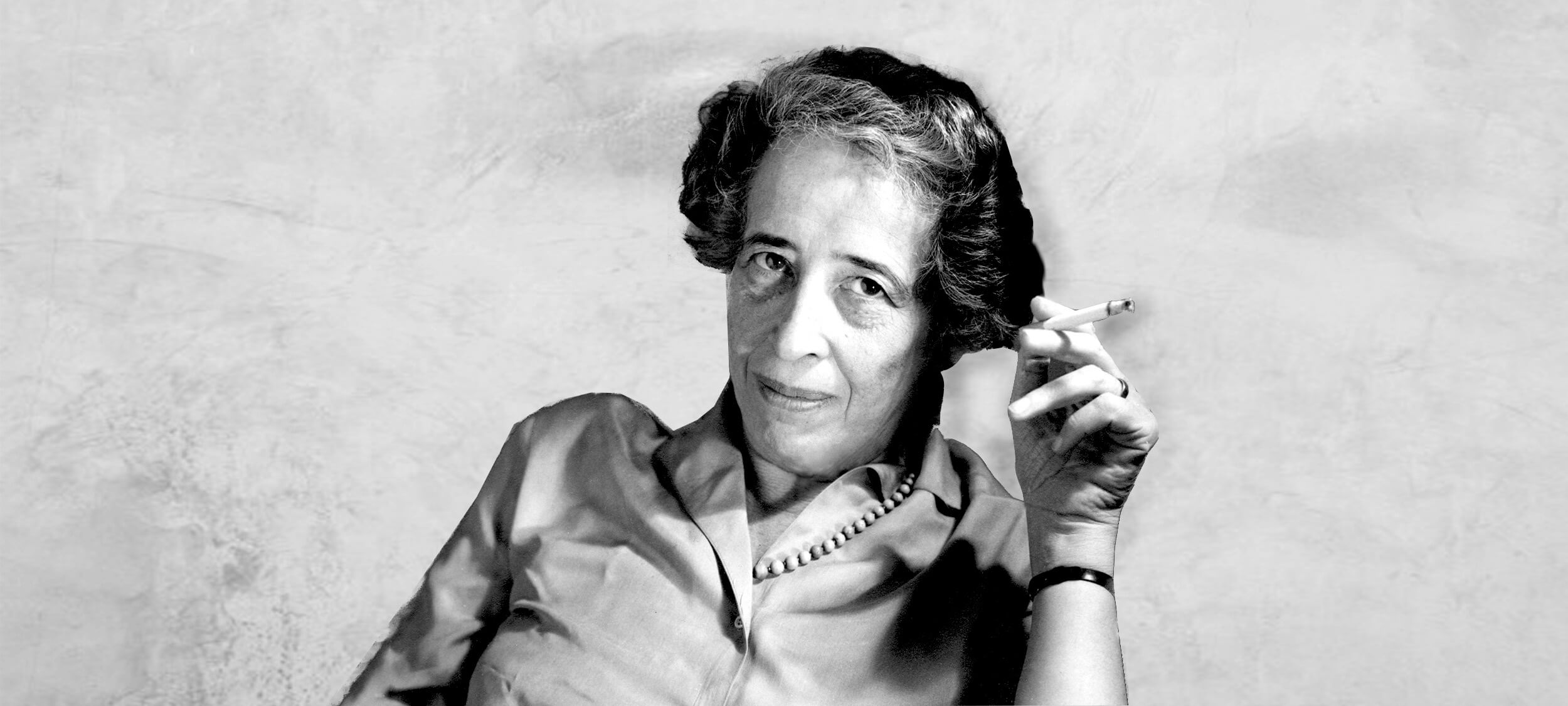

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Johannah “Hannah” Arendt (1906 – 1975) was a German Jewish political philosopher who left life under the Nazi regime for nearby European countries before settling in the United States. Informed by the two world wars she lived through, her reflections on totalitarianism, evil, and labour have been influential for decades.

We are still learning from this seminal political theorist. Her book The Origins of Totalitarianism sold out on Amazon in 2017, more than 60 years after it was first published.

Evil doesn’t need malicious intentions

Arendt’s most well known idea is “the banality of evil”. She explored this in 1963 in a piece for The New Yorker that covered the trial of a Nazi bureaucrat who shared the first name of Hitler, Adolf Eichmann. This later became a book called Eichmann in Jerusalem: Reflections on the Banality of Evil.

In Eichmann, Arendt found a man whose greatest crime was a lack of thinking. His role was to transport Jewish people from German occupied areas to concentration camps in Poland. Eichmann did not kill anyone first hand. He was not involved in designing Hitler’s final solution. But he oversaw the trains that took millions of people to their deaths. They were gassed in chambers or died along the way or in camps due to starvation, overwork, illness, cold, heat, or brutality. Eichmann’s only defence for his involvement in this atrocity was obedience to the law and fulfilling his duty.

Eichmann was so steadfast with this line of reasoning he even referenced the philosopher Immanuel Kant and his theory of moral duty. Kant argued morality was acting on your obligations, not your emotions or what will bring you benefit. For Kant, the person who helps the beggar out of empathy or a belief assisting is a pathway to heaven is not doing an act of good. Kant felt everyone is morally obliged to help the beggar, and they are especially virtuous if they act on this duty despite feeling repulsed or no rewarding sense of doing good.

This does not really suit Eichmann’s argument because Kant was emphasising our ability to reason above emotion. This is precisely where Eichmann failed. We can only guess but it seems likely he did his job without asking questions while feeling a sense of comfort in the safety of his salary and senior position during volatile times.

Arendt believed it was this lack of true thinking and questioning that paved the way to genocide. Evil on the scale of Nazism required far more Adolf Eichmanns than Adolf Hitlers.

Totalitarianism needs political apathy

In studying the causes of WWII, Arendt came across “the masses”. She believed totalitarian regimes needed this to succeed.

By “the masses”, she meant the enormous group of people who are politically disconnected from other members of society. They don’t identify with a particular class, religion, or group. Their lack of group membership deprives them of common interests to demand from government. These people have no interest in politics because they don’t have political clout. They are an unorganised cohort with different, often conflicting desires whose needs are easily disregarded by politicians.

But although these people take no active interest in politics they still hold expectations for the state. If politicians fail those expectations they face “the loss of the silent consent and support of the unorganised masses”. In response, they “shed their apathy” and look for an outlet “to voice their new violent opposition”.

The totalitarian leader emerges from this “structureless mass of furious individuals”. With the political apathy of the masses turned to hostility, leaders will rise by breaking established norms and ignoring the way politics is usually done. Arendt dramatically says they prefer “methods which end in death rather than persuasion”. In short, they’re less likely to build politics up than they are to tear it down because that’s what the masses want.

If this all sounds depressing, there is a solution embedded in Arendt’s writing: political engagement. The masses arise when individuals are lonely and politically disconnected. They are defined by a lack of solidarity or responsibility with other citizens.

By revitalising our political community we can recreate what Arendt sees as good politics. This is when people feel a sense of personal and political responsibility for the nation and are able to band together with other citizens who have common interests. When citizens are connected in solidarity with one another, the mass never occurs and totalitarianism is held at bay.

When work defines you, unemployment is a curse

Not all Arendt’s work was concerned with war and totalitarianism. In The Human Condition, she also offers a general critique of modernity. Drawing on Karl Marx, Arendt thought the industrial age transformed humanity from thinkers into “working animals”.

She thought most people had come to define themselves by their work – reducing themselves to economic robots. Although it’s not a central point of Arendt’s analysis, this reduction is a product of the same forces she sees in the banality of evil. It’s a triumph of ‘doing’ over ‘thinking’ and of humans finding easy ways to define themselves.

Arendt wasn’t just concerned because people were reducing themselves to working drones. She also worried the industrial age which had just redefined them was also about to rob them of their new identities. She believed within a few decades, technology would replace factory jobs. Many people’s work would vanish.

“What we are confronted with is the prospect of a society of labourers without labour, that is, without the only activity left to them. Surely, nothing could be worse.”

In a time when automation now threatens over half of jobs on average in OECD countries, Arendt’s predictions seem timely. Can we shift our identity away from work in time to survive the massive job reduction to come?

Published February 2017. Updated August 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is every billionaire a policy failure?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Social Contract

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Confucius

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights