Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz on diversity and urban sustainability

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz on diversity and urban sustainability

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 16 NOV 2022

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz is the CEO of Mirvac, one of Australia’s largest and most respected property groups. Driven by the company’s purpose, to Reimagine Urban Life, Susan talks about how we can redefine the landscape and create more sustainable, connected and vibrant urban environments, leaving a legacy for generations to come.

“When you’re in high school you can only imagine doing the jobs you can see – you can think about being a doctor, a nurse, a lawyer because those jobs exist. But I always say to my own children that the jobs that they’re going to do don’t even exist yet.”

Susan’s parents took a huge risk when they migrated from Belfast in Northern Ireland to Australia, during the Winter of Discontent in 1978 which was characterised by widespread strikes in the public and private sector. At the time she didn’t think much of it, but upon reflection admires the sacrifices her parents made to give her a better life. First in her family to attend university, Susan completed an undergraduate law degree, but upon completion the notion of being a full time lawyer didn’t appeal to her. Deciding to study urban geography, completing a thesis on the migration of Icelanders to Australia, she says it was this rather left field thesis that set her on the path to become the CEO of Mirvac.

“In one of those moments of serendipity I called my university supervisor and said “what does someone like me do for a job?” And he said he’d had a call that very day from Knight Frank, who were looking for a researcher. And I thought, I don’t know the first thing about real estate, but I can analyse, I can write, so why not? And I jumped into real estate and 30 plus years later I’m still in the industry, having worked all around the world for iconic companies. And it was all just that one moment, one phone call to my supervisor launched me off in this direction.”

Striving for a more diverse workplace

“At Mirvac I have tried very hard to ensure we are as gender diverse as possible, and not just gender diversity, gender is just one element of it – we have a full diversity and inclusion effort going on all the time.”

The academic research into diversity is clear: diverse groups make better decisions than homogeneous ones. It’s proven across cultures, across times and across industries. Susan believes that business leaders must be absolutely conscious at all times about diversity within their work force, because if you don’t play close attention, people default to the practice of hiring those most like them. The problem is, that while some elements of diversity are easily marked, diversity of ideas and thought is a lot harder to measure, she says, “it’s not just about having 50% females at the table, it’s a lot deeper than that. You can only measure the things that are obvious, like cultural background or sexual orientation or gender. You can measure those things, and just hope that they all bring some diversity of thought.”

“I’m very, very proud that at Mirvac we have a zero like for like gender pay gap and have maintained that for six years. And it is very hard to maintain if you if you take your eye off for one minute, the gender pay gap, with all the best intentioned in the world comes creeping back into the organisation.”

What keeps Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz up at night?

“The pace of house price growth is simply unsustainable, many multiples of times greater than wage inflation, which is very anaemic. So it is something that does need urgently to be addressed.”

Housing affordability is one of the most important challenges of our time, and Susan believes the problem lies with supply, “We simply don’t do enough dwellings for the growth of household formation in this country. It is a very serious problem and better or worse in different parts of Australia.” When thinking about solutions to the housing crisis and how we might build the cities of the future, Susan has proven that she thinks very much outside the box, conceiving of the idea of “a house with no bills”. “Imagine if you could live in a house and never pay another energy or water bill. Wouldn’t it be transformational for millions of people. What if we could design a different way of building homes so that we were creating no waste?”

A shift towards a more sustainable future

“The business of business is not just business. It is a lot broader than that. People sign up for a noble mission.”

Ten years ago when Mirvac launched the “This Changes Everything” sustainability strategy, with the goal of being net positive in waste water energy by 2030 (without yet having the technology to do so) people thought she was mad. “senior members of industry said you should never set targets that you don’t know how to meet”. Despite the opposition, Susan doggedly pushed on, and fast forward to 2022, Mirvac is now net positive in scope one, and in scope two emissions are 9 years ahead of schedule. She speaks about how rapidly the notion of sustainability is changing at every level of business from the C-suite to the consumer, “our residential customers who ten years ago, if you were talking to them about sustainability upgrades in their home or apartment, they would hear corporate spin and greenwash. And now they buy sustainability upgrades because they have a desire to live in a more impactful way and with a better impact on the planet.”

“Mirvac people generally don’t wake up in the morning and think, I’m going to go generate some earnings per share today. But they do get up in the morning and think about the legacy that they’re going to leave, how they’re going to push forward design and how they’re going to think about how we can design out our waste from our sites. Those are the things that get Mirvac people motivated, and they’re an extremely passionate group of people dedicated to leaving the world a better place than when we found it.”

AUDIO: Listen to the full podcast discussion above

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz was appointed Chief Executive Officer & Managing Director in August 2012 and a Director of Mirvac Board in November 2012. Prior to this Susan was Managing Director at LaSalle Investment Management. Susan has also held senior executive positions at MGPA, Macquarie Group and Lend Lease Corporation, working in Australia, the US and Europe.

Susan is a Director of the Business Council of Australia, member of the NSW Public Service Commission Advisory Board, a member of the INSEAD Global Board, a Trustee of the Australian Museum Foundation, and the immediate past Chair of the Green Building Council of Australia. She holds a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) from the University of Sydney and an MBA (Distinction) from INSEAD (France).

Find out more about other conversations in the Leading with Purpose podcast. Delve into more articles and podcasts like this by signing up to our Professional Ethics Quarterly newsletter.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How can Financial Advisers rebuild trust?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Roshni Hegerman on creativity and constructing an empowered culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Doing good for the right reasons: AMP Capital’s ethical foundations

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Tim Walker on finding the right leader

Tim Walker on finding the right leader

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 16 NOV 2022

Tim Walker was Former Chief Executive and Artistic Director of the London Philharmonic Orchestra for over twenty years. Balancing its long and distinguished history with a reputation as one of the UK’s most adventurous and forward-looking orchestras, Walker discusses what it takes to grow a profitable business and find the right leader.

Tim Walker was nine when he started learning how to play the piano, and it was only upon attending his very first orchestra, that he realised how much more fun it was to play with other people. So that night, when he arrived home Tim promptly begged his parents to let him start learning the violin too. As a child, Tim was part of the youth orchestra at school, but after a while found it wasn’t really for him… but it was the notion of managing an orchestra, a job which still had that sense of creativity and community which had stolen his heart.

Finding the right leader

“Yes the conductor holds the musicians together but he or she is also using his or her knowledge and intellect to take the written note of the composer and turn it into something that communicates with us in the audience in a very visceral sense, I would say, because it’s not only something that should hit the heart, I think it also needs to hit the head as well.”

While the musicians in the London Philharmonic Orchestra are some of the most talented in the world, it’s the addition of the right conductor that really helps the players shine. The conductor’s role is to unify all the players to one single interpretation of the music, and while the experience of being in a symphony is entirely collaborative, someone needs to ensure everything is flowing seamlessly. But finding the right person for the job hasn’t always been easy. Traditionally in the 19th and 20th centuries, it wasn’t uncommon for a conductor to lead with an iron fist, however as times have changed, so too have conductor styles.

Growing a profitable business

“Interestingly, the London Philharmonic is one of the few orchestras in the world that actually made money from international touring.”

Before Tim joined the London Philharmonic, the company was solely focused on pursuing profit – the board justified each decision by demonstrating how it would contribute to the bottom line. According to Tim, many people make the mistake of thinking just because the individual elements of an enterprise can pay for themselves, then the sum total will be a sustainable enterprise. However, Tim says there are some avenues that need to be pursued not because they generate profit, but rather because doing those things positions the orchestra for the future. As a result, under Tim’s guidance the London Philharmonic recorded all the national anthems for the London Olympics and played at the Queen’s jubilee, not because they were profitable – but because they intrinsically felt like the right thing to do.

Do people still care about orchestras?

“I think, the people do take for granted a lot of the music in their lives as being sort of like wallpaper. I remember when I was talking to somebody who may not know the London Philharmonic, but as soon as I say we recorded all the soundtracks for The Lord of the Rings, suddenly they understand… But they don’t really.”

Over Tim’s twenty year tenure as Artistic Director and Chief Executive of the London Philharmonic, he reveals the hardest part of the job was just keeping everything going. The dilemma is though some would argue that enjoying art is a necessity, music is not the equivalent of food and basic services, so the purchasing of a concert ticket is something that in times of financial stress slows or stops altogether. “You can’t let the institution die on your watch… you’re responsible for 150 full time and 75 part time employees all dependent on ensuring that they can pay their mortgages and put bread on the table.”

Tim highlights that these last few years with COVID-19 have been particularly challenging as audiences are not flocking back as they had hoped.

Tim believes the way to forge a path out of the pandemic is to remind audiences that real people are making this music. The need for live music will never go away, but when you have 200 people whose livelihoods rely on ticket sales, then large orchestras won’t be around for a long time unless we start buying tickets.

“When you care for something, you’ve also got to care for how it’s maintained. So there needs to be a cost to care. And the care for orchestras is in people making the effort to actually go to concerts and appreciate what they have.”

AUDIO: Listen to the full podcast discussion above

Timothy Walker CBE AM Hon RCM was Chief Executive and Artistic Director of the London Philharmonic Orchestra. He was formerly the founder and Chief Executive of World Orchestras and prior General Manager of the Australian Chamber Orchestra. Mr Walker was on the Board of the International Society for the Performing Arts and was Chair of the Association of British Orchestras.

He was an inaugural member of the Australian International Cultural Council, and has served as a director of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Henry Wood Hall Trust and the Rachmaninoff Foundation.

Mr Walker has an honours degree in Arts, a Diploma of Music and a Diploma of Education from the University of Tasmania and a Diploma of Financial Management from the University of New England. He has been a consultant to the Australia Council, Create NSW, Creative Victoria, The Australian Ballet, the Australian Festival of Chamber Music, the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra, the Sydney Conservatorium of Music and the Orcquestra Sinfonica do Estado de Sao Paulo.

Find out more about other conversations in the Leading with Purpose podcast. Delve into more articles and podcasts like this by signing up to our Professional Ethics Quarterly newsletter.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Roshni Hegerman on creativity and constructing an empowered culture

Roshni Hegerman on creativity and constructing an empowered culture

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 16 NOV 2022

Roshni Hegerman is one of the most awarded strategic thinkers globally. Currently JPAC Market Maker and Experience Director across sustainability and people with Oracle, she discusses creativity, psychological safety and how to construct an empowered culture.

When Roshni was a little girl growing up in India, she didn’t have dreams of being an executive or a director, she had much more humble aspirations to be a social worker. Though her parents didn’t feel it was a career path that could support a family long term, Roshni had her heart set on working with people at a local level.

With this in mind, she studied sociology and psychology in college, but then drifted into journalism and communications, which is where her marketing and communications career really begun. Although, she never did realise the goal of becoming a social worker, the ethos of social work and community has informed all of her decision making she says, “I get realy excited by the power of ideas and how they can connect with people and actually drive either a shift in perception or a shift in behaviour or give people a different lens to kind of view the world through that they wouldn’t have typically viewed it through.”

Be a radiator, not a drain

“I think that the traditional sense of creativity probably isn’t as valued as it could be. I think the use of creativity is to innovate and to do things differently and to think about how you’re going to connect in and change things in a positive way. So from that perspective, I actually think that creative thinking is the only thing that cannot be automated.”

Roshni believes that in the modern workplace, as we shift full speed into the world of automation, creativity and the capacity to think outside the box will actually be the most important skill set for young leaders and changemakers of the future.

One of the things that has stuck with her throughout her professional career is to “be a radiator not a drain”. Rather than be a drain she says, sucking the energy out of the room by sticking to the rules and following traditions, we should be radiators – empowering others, generating ideas, and inspiring new ways of thinking. “I think people are starting to realise that if you’re going to continue to do the same thing and get the same result, and the end and it’s not a positive one, then something has to change.”

Roshni often reflects on her professional practice asking a few key questions:

- How can I use my influence to be more of a radiator?

- Is there a more interesting or different direction we could consider?

- What’s stopping us from being more passionate about a project?

- How can I generate enthusiasm in my team?

- Embrace new and innovative ideas

She suggests that if you can be more of a radiator in your workplace, then people will naturally gravitate towards you, there will be less resistance to your ideas.

People who feel safe have the best ideas

“It’s when you feel like you have to meet a quota and you have to get something done that you tend to revert back to what you know and you don’t feel safe to kind of go out of that box and try something different. It’s when you have an organisation where employees feel safe to kind of give something a go and they’re empowered to be able to do that.”

In order to truly embrace one’s inner radiator, one must feel safe and confident within their team to share their ideas without fear of criticism.

Throughout her career, Roshni has explored the idea of psychological safety in the workplace environment. She suggests as leaders it’s important to create a space of safety in the workplace that allows people to feel more open to being more vulnerable whilst confident enough to have their ideas challenged.

She says, “I think it is very important to create an environment where where you don’t feel threatened by the ideas that you have. There needs to be an environment that allows you to feel at ease with sharing kind of a strong point of view, regardless of which direction you come from.”

Roshi works hard to identity the natural unconscious biases that stop team members from being curious because they believe they already know the answer. She emphasises that it’s important to consciously ask pointed questions and embed curiosity and innovation into every element of organisational structure and process in order to force people to look at things from a different perspective.

“I think it helps create a culture of discovery, empathy, curiosity, and opens up different possibilities of pathways that could be considered. So that’s one of the things I feel really excited by is going, ‘how do we consciously think about these things and what can we do to ask the right questions so that we are having the right conversations so that we can engage people’s curious mind to think about things differently?”

Contributing to a better world

“You need to be willing to have a lived experience. You can’t just say that you care about indigenous people or homeless people. You need to see it from their perspective and understand what they’re going through in order to be able to help in the way that they need you to help them, not how you want to help them.”

Despite diverting from the pathway to a career in social work all those years ago, Roshni maintains that the notion of caring for others and celebrating a sense of community has never left her. It’s important to consider the lived experience of different people, rather than assume what people need, you should strive to constantly be out in different communities and speaking to people directly in order to enrich your own perspective.

Roshni suggests it all comes down to realising that at the end of the day, we are all humans who want to be treated with dignity and respect. She believes in giving those who are underrepresented a voice, and a platform so they can get the help that they need. Her advice for the business leaders of the future is: It’s important to understand that it’s not all about you, that the world is about others, that you occupy it with. So how can you actually help make things better, not just for yourself, but for the people around you?

AUDIO: Listen to the full podcast discussion above

Roshni Hegerman is a force of nature with an unstoppable passion to move businesses and people, creating positive impact and change. Roshni currently is JAPAC Market Maker, Experience Director, with Oracle across Sustainability and People; and is founder of her own strategic creative consultancy, PinchofMasla. Roshni is global citizen unafraid of traversing new and unchartered terrain, in fact she relishes in it – working and thriving in United States, China, India and now Australia – with three beautiful children in tow. Roshni helped launch the iPhone in China, start-up BBH and BBDO in India; grow Coca-Cola’s footprint across Asia.

Roshni is a champion for diversity and inclusion and one of the most awarded strategic creative thinkers globally. She has started her own Women in Leadership networking group – “Ladies that Lunch,” to bring like-minded female leaders together to make meaningful change and collaborates closely with Igniting Change and Campfire X, tiny but meaningful organisations that spark big positive change. Roshni launched “Creating Meaningful Change” while at McCann Australia, a 365-day initiative, that puts conscious inclusion at the centre of the agency’s strategic and creative operating system.

Roshni believes that magic is found in the intersection of humanity, creativity and technology.

Find out more about other conversations in the Leading with Purpose podcast. Delve into more articles and podcasts like this by signing up to our Professional Ethics Quarterly newsletter.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

No justice, no peace in healing Trump’s America

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Things you might like to know about the rich

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Shadow values: What really lies beneath?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 16 NOV 2022

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock are the partners in business and life who strive to build wiser future through culture, space and community. With a unique and innovative approach to business, the pair uncover the realities of being a leader, the importance of failure and fostering a wiser culture.

As a performer, Sylvie Barbier has a real passion for community. Her work is a tenacious exploration of the idea of “art as a conversation” and it’s these thematics of life, discussion, and unity which has equipped her to establish the Life Itself initiative. Together with her partner Rufus, a creative technologist and economist, the two have built a collective based in the half way space between Silicon Valley and the Plum Village in the South of France, which is engaged with creating a weller and wiser world.

On defining leadership

“There is an incredible thirst for leadership, not necessarily leaders – but for leadership.”

The world is in a moment of transition. There is an impending climate crisis, widening inequality as well as a huge amount of disunity and civil unrest, and Rufus believes that we must harness this specific moment in time to interrupt our current archaic notions of what constitutes a leader to craft something new and innovative. He suggests, “we are at a cultural moment where leadership is badly needed, but hugely undermined in part because of these past traumas that we are healing from.”

The reality of being leaders

“There’s always going to be a problem, you’re either not doing enough, or you’re doing too much and being oppressive.”

Having led multiple different initiatives through tech, art and community, both Sylvie and Rufus have learnt a lot about the process of leading. Now that they jointly lead Life Itself, they are encountering a whole new suite of hurdles and challenges as part of running the collaborative residency programs. The programs bring a collection of thinkers, creators, technologists and spiritualists together over an extended period to time to debate and engage with the challenges of the modern world.

Rufus says the hardest part is finding the balance as a leader, “invariably after three months there is some sort of crisis – someone is imposing too many rules, someone has to cook too often – and ultimately you are trying to facilitate the group to engage in a transformation and face these issues, what people must learn is that we need to engage with failure. We have an allergy to failure, but it’s these breakdowns which are the most valuable.”

When leaders fail

Capitalist culture dictates that when a company has some major failing – it is generally the CEO who must hand in their resignation. That the decks must be cleared for fresh blood and new ideas to flush out the old. However Rufus fears we may have gone too far, suggesting that we’ve descended into conducting “ritualised executions” when we decide someone needs to take the blame – just because the leader has left their position doesn’t mean the company will be any better off. Rufus suggests that it’s important to identify the source of the problem, and to think about the duties and responsibilities of leaders more holistically.

In reflecting on their own careers both Rufus and Sylvie acknowledge that they have made some mistakes, and at times mismanaged things. As he continues to learn about leadership, Rufus has let go of trying to achieve everything himself, saying, “leadership is about creating a space in which other people can flourish. I think more and more for myself, based on a huge number of errors, it is the act of creating space versus doing it myself which is central.”

Sylvie agrees, adding her biggest obstacle was she had a tendency to pursue ideals without being grounded in the reality of the world and the reality of who she is. She explores her issues with reconciling these two ideas, “sometimes I felt that the vision I had almost became a burden because it was my responsibility to make it happen. And if it doesn’t happen it’s my fault.”

In the past she was characterised by the ruthless pursuit of intangible goals, but found she was ultimately dissatisfied with this way of leading because when she achieved these goals she would immediately need to move on to something else and it felt particularly dissatisfying.

She concludes, “the world is already perfect the way it is, it doesn’t need to be any different than the way it is right now. And in a moment of radical acceptance, I realised I was already in paradise.”

AUDIO: Listen to the full podcast discussion above

Sylvie ‘Shiwei’ Barbier is a French-Taiwanese performance artist, entrepreneur and educator. Her work synthesizes Eastern and Western philosophies and aesthetics. She co-founded Life Itself to build a wiser future through culture, space and community. Her performance art pieces are contemporary rituals, where the audience is invited to take an active and interactive role. She uses language such as Koans as a bridge for the mind into the spiritual realm, by pushing us beyond the bounds of the intellect into a space of greater wholeness and connection.

Rufus Pollock is a technologist, entrepreneur, writer and long-term zen practitioner. He is the founder of Open Knowledge, an award-winning international digital non-profit. Formerly a Shuttleworth Fellow, Ashoka Fellow and a Mead Fellow in Economics at Cambridge University. His book the Open Revolution sets out a vision for a open, free and free information economy and has been translated into multiple languages. As a co-founder of Life Itself he brings curiosity and rigour to ongoing inquiry into how we can create a radically wiser, weller world for all.

Find out more about other conversations in the Leading with Purpose podcast. Delve into more articles and podcasts like this by signing up to our Professional Ethics Quarterly newsletter.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Is it ok to use data for good?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Truth & Honesty

How do we know we’re telling the truth? If someone asks you for the time, do you ever consider the accuracy of your response?

In everyday life, truth is often thought of as a simple concept. Something is factual, false, or unknown. Similarly, honesty is usually seen as the difference between ‘telling the truth’ and lying (with some grey areas like white lies or equivocations in between). ‘Telling the truth’ is somewhat of a misnomer, though. Since honesty is mostly about sincerity, people can be honest without being accurate about the truth.

In philosophy, truth is anything but simple and weaves itself into a host of other areas. In epistemology, for example, philosophers interrogate the nature of truth by looking at it through the lens of knowledge.

After all, if we want to be truthful, we need to know what is true.

Figuring that out can be hard, not just practically, but metaphysically.

Theories of Truth

There are several competing theories that attempt to explain what truth is, the most popular of which is the correspondence theory. Correspondence refers to the way our minds relate to reality. In it, truth is a belief or statement that corresponds to how the world ‘really’ is independent of our minds or perceptions of it. As popular as this theory is, it does prompt the question: how do we know what the world is like outside of our experience of it?

Many people, especially scientists and philosophers, have to grapple with the idea that we are limited in our ability to understand reality. For every new discovery, there seems to be another question left unanswered. This being the case, the correspondence theory leads us to a problem of not being able to speak about things being true because we don’t have an accurate understanding of reality.

Another theory of truth is the coherence theory. This states that truth is a matter of coherence within and between systems of beliefs. Rather than the truth of our beliefs relying on a relation to the external world, it relies on their consistency with other beliefs within a system.

The strength of this theory is that it doesn’t depend on us having an accurate understanding of reality in order for us to speak about something being true. The weakness is that we can imagine there being several different comprehensive and cohesive system of beliefs that, and thus different people having different ‘true’ beliefs that are impossible to adjudicate between.

Yet another theory of truth is pragmatist, although there are a couple of varieties, as with pragmatism in general. Broadly, we can think of pragmatist truth as a more lenient and practical correspondence theory.

For pragmatists, what the world is ‘really’ like only matters as far as it impacts the usefulness of our beliefs in practice.

So, pragmatist truth is in a sense malleable; it, like the scientific method it’s closely linked with, sees truth as a useful tool for understanding the world, but recognises that with new information and experiment the ‘truth’ will change.

Ethical aspects of truth and honesty

Regardless of the theory of truth that you subscribe to, there are practical applications of truth that have a significant impact on how to behave ethically. One of these applications is honesty.

Honesty, in a simple sense, is speaking what we wholeheartedly believe to be true.

Honesty comes up a lot in classical ethical frameworks and, as with lots of ethical concepts, isn’t as straightforward as it seems.

In Aristotelian virtue ethics, honesty permeates many other virtues, like friendship, but is also a virtue in itself that lies between habitual lying and boastfulness or callousness. So, a virtue ethicist might say a severe lack of honesty would result in someone who is untrustworthy or misleading, while too much honesty might result in someone who says unnecessary truthful things at the expense of people’s feelings.

A classic example is a friend who asks you for your opinion on what they’re wearing. Let’s say you don’t think what they’re wearing is nice or flattering. You could be overly honest and hurt their feelings, you could lie and potentially embarrass them, or you could frame your honesty in a way that is moderate and constructive, like “I think this other colour/fit suits you better”.

This middle ground is also often where consequentialism lands on these kinds of interpersonal truth dynamics because of its focus on consequences. Broadly, the truth is important for social cohesion, but consequentialism might tell us to act with a bit more or a bit less honesty depending on the individual situations and outcomes, like if the truth would cause significant harm.

Deontology, on the other hand, following in the footsteps of Immanuel Kant, holds honesty as an absolute moral obligation. Kant was known to say that honesty was imperative even if a murderer was at your door asking where your friend was!

Outside of the general moral frameworks, there are some interesting ethical questions we can ask about the nature of our obligations to truth. Do certain people or relations have a stronger right to the truth? For example, many people find it acceptable and even useful to lie to children, especially when they’re young. Does this imply age or maturity has an impact on our right to the truth? If the answer to this is that it’s okay in a paternalistic capacity, then why doesn’t that usually fly with adults?

What about if we compare strangers to friends and family? Why do we intuitively feel that our close friends or family ‘deserve’ the truth from us, while someone off the street doesn’t?

If we do have a moral obligation towards the truth, does this also imply an obligation to keep ourselves well-informed so that we can be truthful in a meaningful way?

The nature of truth remains elusive, yet the way we treat it in our interpersonal lives is still as relevant as ever. Honesty is a useful and easier way of framing lots of conversations about truth, although it has its own complexities to be aware of, like the limits of its virtue.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

James Hird In Conversation Q&A

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Appreciation or appropriation? The impacts of stealing culture

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 28 OCT 2022

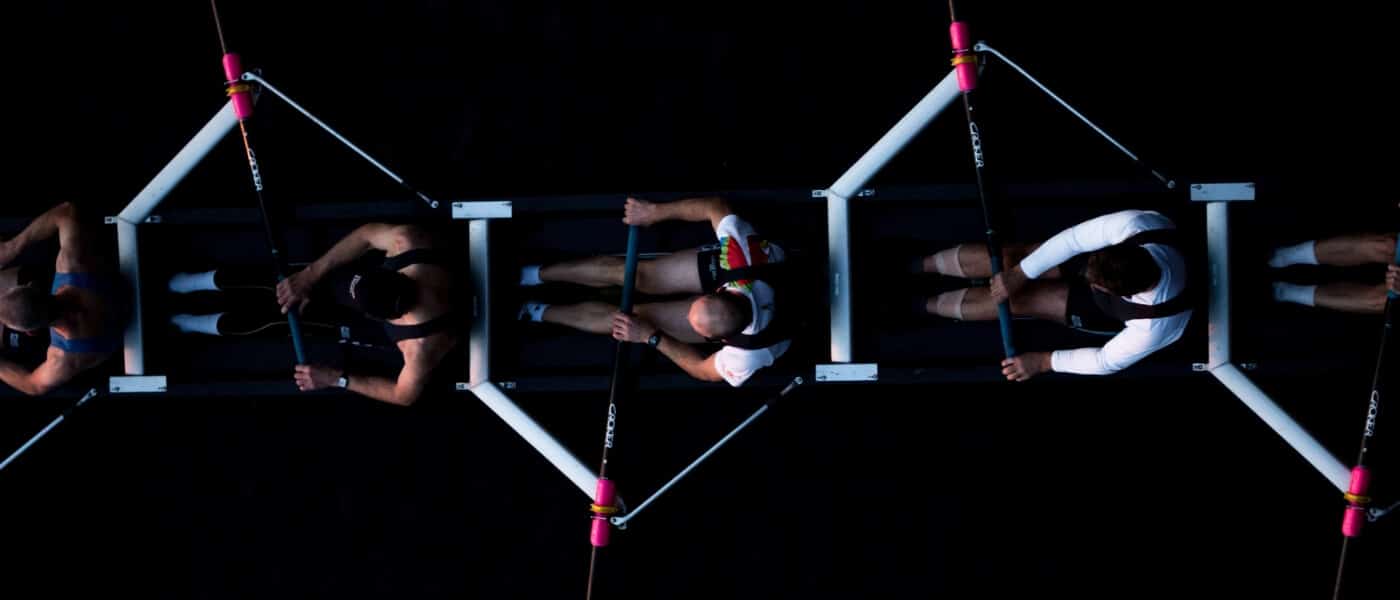

More sporting and arts bodies are thinking hard about whom they’re willing to accept funding or sponsorship deals from. But how are they to weigh the competing interests of their organisations, players and artists, and the general public?

When First Nations netballer Donnell Wallam spoke out to seek an exemption from wearing the logo of major sponsor, Hancock Prospecting, she sparked a national conversation around the role of sponsorship in sport, and what voice players ought to have in choosing which sponsors they accept and which logos they wear on their jerseys.

In the case of Wallam, Netball Australia had just signed at $15 million sponsorship deal with Hancock Prospecting, run by Gina Reinhart, the daughter of the founder, Lang Hancock. This was seen by Netball Australia as a much-needed injection of funding to compensate for the multi-million dollar debt the sport’s governing body had accrued during years of COVID-19 lockdowns and travel restrictions.

But Wallam saw something else. Front of mind for her were comments made by Lang Hancock in a 1984 documentary where he advocated that any Indigenous peoples who had not been assimilated ought to be rounded up and sterilised.

After a weeks of debate and negotiation, Hancock Prospecting withdrew from the sponsorship deal, offering short-term funding until the sporting body could find a new sponsor. In a parting shot, the company released a statement saying “it is unnecessary for sports organisations to be used as the vehicle for social or political causes” and that “there are more targeted and genuine ways to progress social or political causes without virtue signalling or for self-publicity”.

However, there is good reason to believe that Wallam and Netball Australia’s actions were more than a ‘virtue signalling’ exercise, but rather part of an increasing trend of sporting bodies and other organisations thinking carefully about whom they accept funding from and which industries they are willing to be associated with.

In recent times, a group of high-profile Freemantle Dockers players and supporters have called for the club to drop oil and gas company Woodside Energy over concerns about climate change. Australian test cricket captain, Pat Cummins, has also declined to appear in any promotional material for Cricket Australia sponsor Alinta Energy, a move backed by former Wallabies captain, and ACT senator, David Pockock.

Arts organisations have been wrestling with similar questions for some years, prompted by incidents such as the Sydney Biennale in 2014 severing its relationship with Transfield, which operated immigration detention centres, after an artist boycott, and the Sydney Festival in 2022 deciding to suspend all funding agreements with foreign governments after an artist boycott due to a sponsorship agreement with the Israeli embassy.

So how should businesses and other organisations, including sporting and arts bodies, decide whom to accept money from? How should they weigh the interests of players, artists, supporters and the wider public with their financial needs and their organisational values? How do they avoid making rash decisions that themselves trigger a backlash?

How to decide

These are difficult questions to answer, which is why The Ethics Centre has developed a specialised decision-making approach, Decision Lab, to help businesses and other organisations navigate difficult ethical terrain and make better decisions.

The Decision Lab process is designed to bring implicit thinking and buried assumptions to the surface so they can be discussed and debated in the open, providing tools to evaluate decisions before they are committed to so that key considerations are not overlooked.

The foundation of the Decision Lab is gaining a deeper understanding of the organisation’s foundational purpose for being, its values and the principles that guide it. These ought to be the starting point of any big decision, but published mission statements and codes of ethics are often overwhelmed in practice by the organisation’s Shadow Values, which are woven into the unspoken culture. The Decision Lab seeks to bring these values to the surface so they can scrutinised, revised and applied as needed.

The Decision Lab also employs a decision-making model that follows a step-by-step process that covers all the elements necessary to make a comprehensive and defendable decision. This includes factoring in what is known, unknown and assumed, such as how the funding might positively or negatively impact the community, or how it might help to promote a cause that the organisation doesn’t believe in.

It also considers the impacts of a decision on all stakeholders, including the wider community and future generations, and not just those who are closely connected to the decision.

The process also teases out the specific clash of values and principles around a particular decision, which is useful because many dilemmas follow a similar form. So if an organisation has an existing solution to one problem, it might find it already has the necessary reasoning and jusification to respond to another situation that follows the same pattern.

Finally, the Decision Lab applies a ‘no regrets’ test to ensure that nothing has been overlooked. This helps avoid situations where a decision is made yet it runs into problems that could have been forseen if the organisation had applied a more rigorous decision making process, such as a counter-backlash by other segments of their community.

The Decision Lab supports the executive team to align their decisions with the organisation’s ethics framework and helps to communicate with all the key stakeholders the rationale for decisions. By applying a more rigorous decision-making process, an organisation is better able to balance competing interests, resulting in more ethical decisions aligned to its purpose, values and principles that will hold up in the face of scrutiny.

The Ethics Centre is a thought leader in assessing organisational cultural health and building leadership capability to make good ethical decisions. To find our more about Decision Lab, or arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Image by Nigel Owen / Action Plus Sports Images / Alamy

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Political aggression worsens during hung parliaments

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sir Geoff Mulgan on what makes a good leader

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Kimberlé Crenshaw

Kimberlé Crenshaw (1959-present) is one of the most influential feminist philosophers of our time. She is known for her advocacy for American civil rights, being a leading scholar of critical race theory, and pioneering what we now know as the third wave of feminism.

Crenshaw was born in Ohio, US in 1959. As a child, she grew up through the US civil rights and second wave feminist movements, both which occured throughout the 1960s and 70s. This time of revolutionary movements towards equality influenced how Crenshaw was raised.

“My mom was a little bit more radical and confrontational and my father was a little bit more Martin Luther King and ‘find common ground’. Which is probably why there are strains of both of those in my work.”

In 1984, Crenshaw graduated from Harvard Law School. At this time, there was only one woman and one Black professor of the 60 who were tenured. She is now a tenured professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and splits her time there with the Columbia School of Law in NYC.

Where do race and gender meet?

“I argue that Black women are sometimes excluded from feminist theory and antiracist policy discourse because both are predicated on a discrete set of experiences that often does not accurately reflect the interaction of race and gender.”

Crenshaw is most notable for coining the term “intersectionality,” which refers to the idea that when someone has multiple identities, it causes them to experience different and compounded forms of oppression. Rather than oppression being additive across multiple identities, intersectionality tells us that the experience of oppression will be multiplied. For example, a Black woman will experience discrimination because she is Black, because she is a woman, and also because she is a Black woman – which is a different kind of discrimination altogether.

“Because the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that does not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the particular manner in which Black women are subordinated.”

In the academic world, the term intersectionality debuted in Crenshaw’s 1989 paper Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. Many scholars would say that the publishing of this paper catalysed the third wave of feminism, which is characterised by advocates demanding a more wholistic type of equality for people of all genders, races, socioeconomic backgrounds, abilities, ages, and in all countries.

Two years after the paper was published, Crenshaw assisted Professor Anita Hill’s legal team during Judge Clarence Thomas’s confirmation hearing to the US Supreme Court in October of 1991. In an interview with the Guardian, she reflects that the experience cemented the need for an intersectional theory of social justice. It was clear that “race was playing a role in making some women vulnerable to heightened patterns of sexual abuse [a]nd … anti-racism wasn’t very good at dealing with that issue.”

Intersectionality finally appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary in 2015, where it is defined as “the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.”

A founder of critical race theory

“You can’t fix a problem you can’t name.”

Crenshaw has also spent a large part of her academic career developing and writing about what is now known as critical race theory. In its purest form, critical race theory is a 40-year-old academic framework that concerns itself with defining and understanding the plethora of ways that race impacts American institutions and systems, and how American institutions and culture uphold racist ideals. Crenshaw’s own definition, however, is more of a verb than a noun. For her, critical race theory is “a way of seeing, attending to, accounting for, tracing and analysing the ways that race is produced.”

One of the big cultural issues in the 21st century in America has been whether to teach critical race theory in public schools across the country. Parents and politicians across America have fought to remove what they think critical race theory is out of children’s education. They have argued that CRT is racist and teaches kids to “hate their own country.” Crenshaw now says she sees her work “as talking back against those who would normalise and neutralise intolerable conditions in our lives.”

Where to now?

Crenshaw continues to educate and inspire the next generation by teaching classes in Advanced Critical Race Theory, Civil Rights, Intersectional Perspectives on Race, Gender and the Criminalization of Women & Girls, and Race, Law and Representation at UCLA. At Columbia, she continues to work on the AAPF and through the forum, co-authored a paper in 2015 with Andrea Richie entitled Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women.

She regularly writes for a number of publications and provides commentary for the new outlets MSNBC and NPR. Crenshaw also hosts her own podcast Intersectionality Matters.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Reports

Politics + Human Rights

The Cloven Giant: Reclaiming Intrinsic Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Antisocial media: Should we be judging the private lives of politicians?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to improve your organisation’s ethical decision-making

How to improve your organisation’s ethical decision-making

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 4 OCT 2022

Are you confident in your organisation’s ability to negotiate difficult ethical terrain? The Ethics Centre’s Decision Lab is a robust process that can help expand your ethical decision-making capability.

Imagine you run a not-for-profit that helps people experiencing problem gambling. You are approached by a high-net-worth individual connected to the gambling industry who is interested in making a substantial donation to your organisation. Funding is always hard to come by and you know you could reach many more people in need with this money. Do you accept the donation?

Or imagine you are the CEO of a publicly listed consulting firm that is deciding whether to take on a new client in the fossil fuel industry. You suspect it would be unpopular with younger members of your staff and some of your other clients, but it’s a very lucrative contract and it would significantly boost your bottom line ahead of reporting season. Do you take on the client?

What if you sat on the board of a major corporation that is planning to make a public statement urging the government to adopt a new progressive social policy. The proposed policy does not impact your business directly, but a majority of your staff support it. However, you personally have misgivings about the policy and suspect some other employees do as well. Do you put your name on the public statement?

What would you do in each of these situations? If you do have an answer, could you explain how you arrived at your decision? Could you defend it in public? Could you defend it on the front page of the newspaper?

Dealing with ethically-charged situations like these is never easy. Not only do our decisions have a material impact on multiple stakeholders, but we also need to be able to communicate and justify them. This is complicated by the fact that many of the influences on our ethical decision-making are implicit, meaning we risk making decisions based on unexamined values or we might struggle to explain how we arrived at a particular conclusion.

This is why The Ethics Centre has developed Decision Lab, a comprehensive ethical decision-making toolkit that surfaces the implicit elements in ethical decision-making and provides a robust process to navigate the ethical dimensions of critical decisions for organisations big and small.

Decision Lab

The Decision Lab process begins by clarifying the organisation’s core purpose, values and principles. The purpose includes the organisation’s overall mission, which is what it is aiming to achieve, and its vision, which is what the world looks like when it has achieved it. The values are what the organisation believes to be good and the principles are the guiderails that guide decision-making.

Even organisations that have published mission statements and codes of conduct will find that employees will have different understandings of purpose, values and principles, and these differences can influence ethical decision-making in a profound way. By bringing these perspectives to the surface, the Decision Lab process enables the diversity to be recognised and engaged with constructively rather than leaving it implicit and having different individuals pulling in different directions.

The Decision Lab also explores the process of decision-making, testing critical assumptions and taking multiple perspectives into account to ensure no key elements are overlooked. Take the hypothetical above about the not-for-profit. It would be easy to focus on the issue of whether it is hypocritical to accept money from those associated with gambling in order to fight problem gambling. But it is also crucial to consider the impact on other stakeholders, such as the beneficiaries of the not-for-profit’s services, their families and communities, or consider whether the perception of hypocrisy might affect future fundraising.

Shadow values

The process also acknowledges common biases and influences that can derail decision-making. A common one is the organisation’s Shadow Values which are the hidden uncodified norms and expectations promoted often out of awareness that can influence how the entire organisation operates. For example, many organisations explicitly subscribe to values such as integrity, but the shadow values might promote loyalty, which could prevent an employee from calling out a senior manager who is misrepresenting the work being done for a client.

The Decision Lab then provides a checklist for decisions that can be used as a ‘no regrets test,’ ensuring that all relevant elements have been considered. For example, should the consulting firm reject the contract with the fossil fuel company, it could suffer a backlash from shareholders, who argue that the board has a responsibility to create value for shareholders within the law rather than pursue political agendas. The Decision Lab checklist would ensure that such eventualities are considered before the decision was made.

The decision-making process is then stress tested against a variety of hypothetical scenarios, such as those above, that are tailored to the organisation’s mission and circumstances. This allows participants to put ethical decision-making into practice, engage in constructive deliberation and learn how to evaluate options and develop implementation plans as a team.

On completion of the Decision Lab, The Ethics Centre provides a customised decision-making framework that is tailored to the organisation and its needs for future reference.

Open book

The Decision Lab is a powerful and practical tool for any organisation looking to improve its ethical decision-making. It also has other benefits, such as increases awareness of the lived organisational culture, including the beliefs, attitudes and practices shared amongst its people. It identifies how the current culture and systems are enabling or constraining the realisation of the organisation’s goals.

By unifying employees around a common purpose and encouraging values-aligned behaviour, it ensures that the entire organisation is working as a unit towards a shared vision. The deliberative process also helps to build a climate of trust within the organisation, which aids in avoiding and resolving conflicts, as well as promoting good decision-making.

Individuals and organisations are constantly making decisions that have wide-reaching impacts. The question is: are you doing it well? The Decision Lab can ensure that your organisation’s decision-making is done in an open, robust and constructive manner, producing more ethical decisions and contributing to a positive work culture.

The Ethics Centre is a thought leader in assessing organisational cultural health and building leadership capability to make good ethical decisions. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Or visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The value of principle over prescription

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

We are on the cusp of a brilliant future, only if we choose to embrace it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

MIT Media Lab: look at the money and morality behind the machine

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 20 SEP 2022

Crime, culture, contempt and change – this year our Festival of Dangerous Ideas speakers covered some of the dangerous issues, dilemmas and ideas of our time.

Here are 5 things we learnt from FODI22:

1. Humans are key to combating misinformation

Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen says the world’s biggest social media platform’s slide into a cesspit of fake news, clickbait and shouty trolling was no accident – “Facebook gives the most reach to the most extreme ideas – and we got here through a series of individual decisions made for business reasons.”

While there are design tools that will drive down the spread of misinformation and we can mobilise as customers to put pressure on the companies to implement them, Haugen says the best thing we can do is have humans involved in the decision-making process about where to focus our attention, as AI and computers will automatically opt for the most extreme content that gets the most clicks and eyeballs.

2. We must allow ourselves to be vulnerable

In an impassioned love letter “to the man who bashed me”, poet and gender non-conforming artist, Alok teaches us the power of vulnerability, empathy and telling our own stories. “What’s missing in this world is a grief ritual – we carry so much pain inside of us, and we have nowhere to put the pain so we put it in each other.”

The more specific our words are the more universally we resonate, Alok says, “what we’re looking for as a people is permission – permission not just to tell our stories, but also to exist.”

3. We have to know ourselves better than machines do

Tech columnist and podcaster, Kevin Roose says “we are all different now as a result of our encounters with the internet.” From ‘recommended for you’ pages to personalisation algorithms, every time we pick up our phones, listen to music, watch Netflix, these persuasive features are sitting on the other side of our screens, attempting to change who we are and what we do. Roose says we must push back on handing all control to AI, even if it’s time consuming or makes us feel uncomfortable.

“We need a deeper understanding of the forces that try to manipulate us online – how they work, and how to engage wisely with them is the key not only to maintaining our independence and our sense of selves, but also to our survival as a species.”

4. We can use shame to change behaviour

Described by writer Jess Hill as “the worst feeling a human can possibly have”, the World Without Rape the panel discuss the universal theme of shame when it comes to sexual violence and its use as a method of control.

Instead of it being a weight for victims to bear, historian Joanna Bourke talks about shame as a tool to change perpetrator behaviour. “Rapists have extremely high levels of alcohol abuse and drug addictions because they actually do feel shame… if we have feminists affirming that you ought to feel shame then we can use that to change behaviour.”

5. Reason, science and humanism are the key to human progress

Steven Pinker believes in progress, arguing that the Enlightenment values of reason, science and humanism have transformed the world for the better, liberating billions of people from poverty, toil and conflict and producing a world of unprecedented prosperity, health and safety.

But that doesn’t mean that progress is inevitable. We still face major problems like climate change and nuclear war, as well as the lure of competing belief systems that reject reason, science and humanism. If we remain committed to Enlightenment values, we can solve these problems too. “Progress can continue if we remain committed to reason, science and humanism. But if we don’t, it may not.”

Catch up on select FODI22 sessions, streaming on demand for a limited time only.

Photography by Ken Leanfore

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Absolutism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The etiquette of gift giving

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Is technology destroying your workplace culture?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 12 SEP 2022

Critical Race Theory (CRT) seeks to explain the multitude of ways that race and racism have become embedded in modern societies. The core idea is that we need to look beyond individual acts of racism and make structural changes to prevent and remedy racial discrimination.

History

Despite debates about Critical Race Theory hitting the headlines relatively recently, the theory has been around for over 30 years. It was originally developed in the 1980s by Derrick Bell, a prominent civil rights activist and legal scholar. Bell argued that racial discrimination didn’t just occur because of individual prejudices but also because of systemic forces, including discriminatory laws, regulations and institutional biases in education, welfare and healthcare.

During the 1950s and 1960s in America, there were many legal changes that moved the country towards racial equality. Some of the most significant legal changes include the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which explicitly banned racial apartheid in American schools, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

These rulings and laws formally criminalised segregation, legalised interracial marriage and reduced restrictions in access to the ballot box that had been commonplace in many parts of America since the 1870s. There was also a concerted effort across education and the media to combat racially discriminatory beliefs and attitudes.

However, legal scholars noticed that even in spite of these prominent efforts, racism persisted throughout the country. How could racial equality be legislated by the highest court in America, and yet racial discrimination still occur every day?

Overview

Critical race theory, often shortened to CRT, is an academic framework that was developed out of legal scholarship that wanted to explain how institutions like the law perpetuates racial discrimination. The theory evolved to have an additional focus on how to change structures and institutions to produce a more equitable world. Today, CRT is mostly confined to academia, and while some elements of CRT may inform parts of primary and secondary education, very few schools teach CRT in its full form.

Some of the foundational principles of CRT are:

- CRT asserts that race is socially constructed. This means that the social and behavioural differences we see between different racialised groups are products of the society that they live in, not something biological or “natural.”

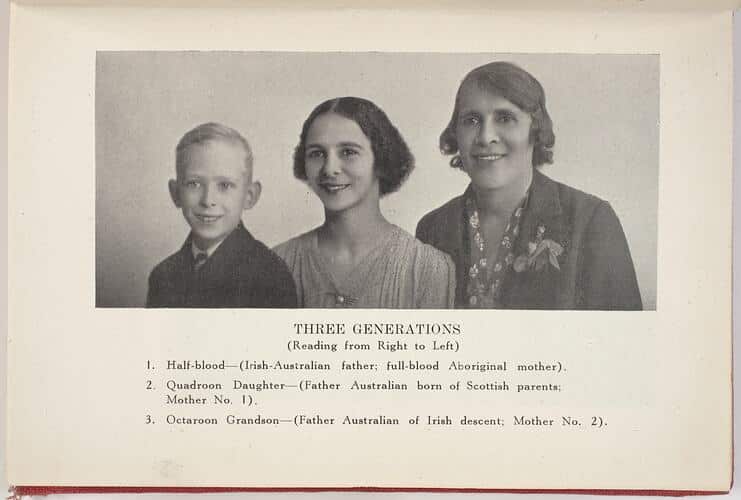

There is a long history of people using science to attempt to prove that there were significant social and psychological differences among people of different racial groups. They claimed these differences justified the poor treatment of people of different ‘inferior races’, or the ‘breeding out’ of certain races. This is how white Australians justified the atrocities committed in the Stolen Generations, such as the attempted ‘breeding out’ of Aboriginal people.

2. Racism is systemic and institutional. Imagine if everyone in the world magically erased all their racial biases. Racism would still exist, because there are systems and institutions that uphold racial discrimination, even if the people within them aren’t necessarily racist.

There are many examples of systemic and institutional racism around the world. They become evident when a system doesn’t have anything explicitly racist or discriminatory about it, but there are still differences in who benefits from that system. One example is the education system: it’s not explicitly racist, but students of different racial backgrounds have different educational outcomes and levels of attainment. In the US, this occurs because public schools are funded by both local and state governments, which means that children going to school in lower socioeconomic areas will be attending schools that receive less funding. Statistically, people of colour are more likely to live in lower socioeconomic areas of America. So, even though the education system isn’t explicitly racist (i.e., treating students of one racial background differently from students of a different racial background), their racial background still impacts their educational outcomes.

3. There is often more than one part of identity that can impact a person’s interaction with systems and institutions in society. Race is just one of many parts of identity that influences how a person will interact with the world. Different identities, including race, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, religion and ability, intersect with each other and compound. This is an idea known as “intersectionality.”

Most of the time, it’s not just one part of a person’s identity that is impacting their experiences in the world. Someone who is a Black woman will experience racism differently from a Black man, because gender will impact experience, just like race. A wealthy Chinese-Australian person will have a different experience living in Australia than a working class Chinese-Australian person. Ultimately, CRT tells us that we need to look at race in conjunction with other facets of identity that impact a person’s experience.

Critical Race Theory and racism in Australia

As Australians, it’s easy to point the finger at the US and think “well, at least we aren’t as bad as them.” However, this mentality of only focusing on the worst instances of racism means we often ignore the happenings closer to home. A 2021 survey conducted by the ABC found that 76% of Australians from a non-European background reported experiencing racial discrimination. One-third of all Australians have experienced racism in the workplace and two-thirds of students from non-Anglo backgrounds have experienced racism in school.

In addition to frequent instances of racism, Australia’s history is fraught with racism that is predominantly left out of high school history textbooks. From our early colonial history to racial discrimination during the gold rush in the 1850s to anti-immigration rhetoric today, we don’t need to look far for examples of racial discrimination. A little known part of Australian history is that non-British immigrants from 1901 until the 1960s were told that if they moved to Australia, they had to shed their languages and culture.

Even though CRT originates in the US, it is a useful framework for encouraging a closer analysis of Australia’s racist history and how this has caused the imbalances and inequalities we see today. And once we understand the systemic and institutional forces that promote or sustain racial injustice, we can take measures to correct them to produce more equitable outcomes for all.

If you want to learn more about how race has impacted the world today, here are some good places to start:

- Nell Painter’s Soul Murder and Slavery – her work has focused on the generational psychological impact of the trauma of slavery. Here is an interview where Painter talks a little bit about her work.

- Nikole Hannah-Jones’ 1619 Project, with the New York Times – you can listen to the podcast on Spotify, which has six great episodes on some of the less reported ways that slavery has impacted the functioning of US society.

- Dear White People – a Netflix show that deals with some of the complications of race on a US college campus.

- Ladies in Black – a movie about Sydney c. 1950s, shows many instances of the casual racism towards refugees and immigrants from Europe.

For a deeper dive on Critical Race Theory, Claire G. Coleman presents Words Are Weapons and Sisonke Msimang and Stan Grant present Precious White Lives as Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Constitution is incomplete. So let’s finish the job

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Scepticism

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships