Ethics Explainer: Lying

Lying is something we’ve all done at some point and we tend to take its meaning for granted, but what are we really doing when we lie, and is it ever okay?

A person lies when they:

- knowingly communicate something false

- purposely communicate it as if it was true

- do so with an intention to deceive.

The intention to deceive is an essential component of lying. Take a comedian, for example – they might intentionally present a made-up story as true when telling a joke, engaging in satire, etc. However, the comedian’s purpose is not to deceive but to entertain.

Lying should be distinguished from other deviations from the truth like:

- Falsehoods – false claims we make while believing what we say to be true

- Equivocations – the use of ambiguous language that allows a person to persist in holding a false belief.

While these are different to lying, they can be equally problematic. Accidentally communicating false information can still result in disastrous consequences. People in positions of power (e.g., government ministers) have an obligation to inform themselves about matters under their control or influence and to minimise the spread of falsehoods. Having a disregard for accuracy, while it is not lying, should be considered wrong – especially when as a result of negligence or indifference.

The same can be said of equivocation. The intention is still there, but the quality of exchange is different. Some might argue that purposeful equivocation is akin to “lying by omission”, where you don’t actively tell a lie, but instead simply choose not to correct someone else’s misunderstanding.

Despite lying being fairly common, most of our lives are structured around the belief that people typically don’t do it.

We believe our friends when we ask them the time, we believe meteorologists when they tell us the weather, we believe what doctors say about our health. There are exceptions, of course, but for the most part we assume people aren’t lying. If we didn’t, we’d spend half our days trying to verify what everyone says!

In some cases, our assumption of honesty is especially important. Democracies, for example, only function legitimately when the government has the consent of its citizens. This consent needs to be:

- free (not coerced)

- prior (given before the event needing consent)

- informed (based on true and accessible information)

Crucially, informed consent can’t be given if politicians lie in any aspects of their governance.

So, when is lying okay? Can it be justified?

Some philosophers, notably Immanuel Kant, argue that lying is always wrong – regardless of the consequences. Kant’s position rests on something called the “categorical imperative”, which views lying as immoral because:

- it would be fundamentally contradictory (and therefore irrational) to make a general rule that allows lying because it would cause the concepts of lies and truths to lose their meaning

- it treats people as a means rather than as autonomous beings with their own ends

In contrast, consequentialists are less concerned with universal obligations. Instead, their foundation for moral judgement rests on consequences that flow from different acts or rules. If a lie will cause good outcomes overall, then (broadly speaking) a consequentialist would think it was justified.

There are other things we might want to consider by themselves, outside the confines of a moral framework. For example, we might think that sometimes people aren’t entitled to the truth in principle. For example, during a war, most people would intuit that the enemy isn’t entitled to the truth about plans and deployment details, etc. This leads to a more general question: in what circumstances do people forfeit their right to the truth?

What about “white lies”? These lies usually benefit others (sometimes at the liar’s expense!) or are about trivial things. They’re usually socially acceptable or at least tolerated because they have harmless or even positive consequences. For example, telling someone their food is delicious (even though it’s not) because you know they’ve had a long day and wouldn’t want to hurt their feelings.

Here are some things to ask yourself if you’re about to tell a white lie:

- Is there a better response that is truthful?

- Does the person have a legitimate right to receive an honest answer?

- What is at stake if you give a false or misleading answer? Will the person assume you’re telling the truth and potentially harm themselves as a result of your lie? Will you be at fault?

- Is trust at the foundation of the relationship – and will it be damaged or broken if the white lie is found out?

- Is there a way to communicate the truth while minimising the hurt that might be caused? For example, does the best response to a question about an embarrassing haircut begin with a smile and a hug before the potentially hurtful response?

Lying is a more complex phenomenon than most people consider. Essentially, our general moral aversion to it comes down to its ability to inhibit or destroy communication and cooperation – requirements for human flourishing. Whether you care about duties, consequences or something else, it’s always worth questioning your intentions to check if you are following your moral compass.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Get mad and get calm: the paradox of happiness

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Epistemology

Mostly, we take “knowledge” or “knowing” for granted, but the philosophical study of knowledge has had a long and detailed history that continues today.

We constantly claim to ‘know things’. We know the sun will rise tomorrow. We know when we drop something, it will fall. We know a factoid we read in a magazine. We know our friend’s cousin’s girlfriend’s friend saw a UFO that one time.

You might think that some of these claims aren’t very good examples of knowledge, and that they’d be better characterised as “beliefs” – or more specifically, unjustified beliefs. Well, it turns out that’s a pretty important distinction.

“Epistemology” comes from the Greek words “episteme” and “logos”. Translations vary slightly, but the general meaning is “account of knowledge”, meaning that epistemology is interested in figuring out things like what knowledge is, what counts as knowledge, how we come to understand things and how we justify our beliefs. In turn, this links to questions about the nature of ‘truth’.

So, what is knowledge?

A well-known, though still widely contentious, view of knowledge is that it is justified true belief.

This idea dates all the way back to Plato, who wrote that merely having a true belief isn’t sufficient for knowledge. Imagine that you are sick. You have no medical expertise and have not asked for any professional advice and yet you believe that you will get better because you’re a generally optimistic person. Even if you do get better, it doesn’t follow that you knew you were going to get better – only that your belief coincidentally happened to be true.

So, Plato suggested, what if we added the need for a rational justification for our belief on top of it being true? In order for us to know something, it doesn’t just need to be true, it also needs to be something we can justify with good reason.

Justification comes with its own unique problems, though. What counts as a good reason? What counts as a solid foundation for knowledge building?

The two classical views in epistemology are that we should rely on the perceptual experiences we gain through our senses (empiricism) or that we should rely first and foremost on pure reason because our senses can deceive us (rationalism). Well-known empiricists include John Locke and David Hume; well-known rationalists include René Descartes and Baruch Spinoza.

Though Plato didn’t stand by the justified true belief view of knowledge, it became quite popular up until the 20th century, when Edmund Gettier blew the problem wide open again with his paper “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?”.

Since then, there has been very little consensus on the definition, with many philosophers claiming that it’s impossible to create a definition of knowledge without exceptions.

Some more modern subfields within epistemology are concerned with the mechanics of knowledge between people. Feminist epistemology, and social epistemology more broadly, deals with a lot of issues that raise ethical questions about how we communicate and perceive knowledge from others.

Prominent philosophers in this field include Miranda Fricker and José Medina. Fricker developed the concept of “epistemic injustice”, referring to injustices that involve the production, communication and understanding of knowledge.

One type of knowledge-based injustice that Fricker focuses on, and that has large ethical considerations, is testimonial injustice. These are injustices of a kind that involve issues in the way that testimonies – the act of telling people things – are communicated, understood, believed. It largely involves the interrogation of prejudices that unfairly shape the credibility of speakers.

Sometimes we give people too much credibility because they are attractive, charismatic or hold a position of power. Sometimes we don’t give people enough credibility because of a race, gender, class or other forms of bias related to identity.

These types of distinctions are at the core of ethical communication and decision-making.

When we interrogate our own views and the views of others, we want to be asking ourselves questions such as: Have I made any unfair assumptions about the person speaking? Are my thoughts about this person and their views justified? Is this person qualified? Did I get my information from a reliable source?

In short, a healthy degree of scepticism (and self-examination) should be used to filter through information that we receive from others and to question our initial attitudes towards information that we sometimes take for granted or ignore. In doing this, we can minimise misinformation and make sure that we’re appropriately treating those who have historically been and continue to be silenced and ignored.

Ethics draws attention to the quality and character of the decisions we make. We typically hold that decisions are better if well-informed … which is another way of saying that when it comes to ethics, knowledge matters!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Sometimes life can seem overwhelming. Often, it’s because we can’t help focusing on the bad stuff and forgetting about the good.

Don’t feel too bad. We’re hard-wired to be more impacted by negative events, feelings and thoughts than those things that are positive. Surprisingly, when experiencing two experiences that have equal intensity, we’ll get stuck on the negative rather than the positive.

This psychological phenomenon is called negativity bias, which is a type of unconscious bias. Unconscious biases are attitude and judgements that aren’t obvious or known to us but still affect our thinking and actions. They are often in play despite the fact we may consciously hold a different view. They’re not called unconscious for nothing.

This is an especially tricky aspect of negativity bias since we tend not to notice ourselves latching onto the negative aspects of any given situation, which makes preventing a psychological spiral all the more difficult.

We’ve all experienced how easy it is to spiral due to the one hater who pops up in in our Insta or Twitter feed despite the many positive comments we could be basking in. This is the pernicious power of negativity bias – we are disproportionately affected by negative experiences rather than the positive.

Remember that time a co-worker or friend said something irritating to you near the beginning of the day and it remained in your mind the whole day, despite other positive things happening like being complimented by a stranger and getting lots of work done? Of course you remember it. Because our memories are also drawn like a magnet to those negative experiences even when far outweighed by the positive experiences that surrounded it. You might have finished that day still feeling down because you hadn’t been able to forget about the comment, despite the day on the whole having been pretty good.

Something that’s been prevalent for the past two years is negativity around various COVID-19 measures. It’s easy for us to focus on the frustration of forgetting to take our mask with us somewhere or the inconvenience of constantly checking-in. Often these small things can linger in our minds or affect our moods, while small positive things will go almost unnoticed.

Negativity bias can also affect things outside our mood. It can affect our perceptions of people and our decision making.

It also causes us to focus on or amplify the negative aspects of someone’s character, resulting in us expecting the worst of them or seeing them in a broadly negative light. Assuming someone’s intentions are negative is a common way that arguments and misunderstandings occur.

It can also heavily affect our decision-making process, an effect demonstrated by Nobel Prize winners Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who were groundbreakers in uncovering the role of unconscious bias. Over-emphasising negative aspects of situations can, for example, cause us to misperceive risk and act in ways we normally wouldn’t. Imagine walking down the street and losing $50. How does that feel? Now imagine walking down that same street and finding $50. How different does it feel to find, rather than lose $50? Kahneman used this experiment to show that we are loss averse – even though the amount is the same, most people will feel worse having lost something than having found something, even when it is of equal value.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. Research suggests that this bias comes from our early need to be attentive to danger, and there are various ways we can remain attentive to possible threats while stemming the effect of negativity on our mental state.

Minimising negativity bias can be difficult, especially when we focus on compounding problems, but here are a few things to remind ourselves of that can help combat negativity spirals.

- Make the most of positive moments. It’s easy to fall into a habit of glossing over small victories but taking a few minutes to slow down and appreciate a sunny day, or a compliment from a friend, or a nice meal can help to take the negative winds out of our sails.

- Actively self-reflect. This can include things like recognising and acknowledging negative self-talk, trying to reframe the way you speak about things to others in a more positive light and double-checking that when you do interpret something as negative that it is proportionate to the threat or harm it poses. If it’s not, take some time to reassess.

- Develop new habits. In combination with making an effort to recognise negative thought patterns, we can develop habits that help to counteract them. Pay attention to what activities give you mental space or clarity, or tend to make you happy, and try to do them when you can’t quite shake the negativity off. It could be as simple as going for a walk, reading a book, or listening to feel-good music.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Blame

In an age of ubiquitous media coverage on anything and everything, most people see blaming behaviour every day. But what exactly is blame? How do we do it? Why do we do it?

During the 2019-20 bushfires, the Prime Minister Scott Morrison was blamed for taking a vacation during an environmental crisis. During a peak in the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, protestors in Australia blamed individual police and the government at large for the historical and present violent mistreatment of First Nations people.

Maybe you still blame your overly angry high school teacher for making you an anxious person. Maybe you blamed your co-worker recently for standing you up on your weekly Zoom call.

Whatever the stakes, we are all familiar with blaming, but could you explain what it is?

At a very basic level, blame is considered a negative reaction that we have towards someone we perceive as having broken a moral norm, leaving us feeling wronged.

There are several theories of blame that explore different interpretations of how exactly it works, but an overarching distinction is that of how or whether it’s communicated.

On the one hand, we have communicative blame – this is the outward behaviour that indicates one person blames another for something. When we yell at someone for running a red light, scold a politician on social media, or tell someone we are disappointed with their actions, we are communicating blame. Sometimes blame can even be communicated subtly, in the small ways we speak or act.

Some people think that it’s necessary for blame to be communicated – that blame without this overt aspect isn’t quite blame. On the other hand, some people think that there can be internal blame, where a person never outwardly acknowledges that they blame someone for something but still holds an internalised judgement and emotion or desire – imagine someone who holds a grudge against a friend who moved across the world but doesn’t speak to them anymore.

When we think about blame, we have to ask ourselves why do we blame, what does it do and when is it ok?

A common answer looks towards history and especially religion. In the Bible, for example, blame is often seen to hold us to account and discourage dissent. Blame has often been (and is still) used as a social and political indicator of what’s acceptable to citizens and/or governments.

This is more obvious when we consider communicative blame. Take for example, the way that the Australian public and news media communicated their blame of the Prime Minister during his bushfire vacation. These expressions ranged from simply showing dissatisfaction, to more complex indications of a desire for change and a serious acknowledgement of a moral failing.

And it also goes the other way. During the 2021 daily COVID-19 press conferences, various politicians have been quick to communicate their blame towards various groups of people flouting public health orders.

But is this type behaviour always okay? Is it always effective? These are the kinds of questions ethicists ask and attempt to answer when thinking at things like blame. One way to think about these questions is to look at them through different ethical frameworks.

Consequentialism tells us to pay attention to the outcomes of our actions, dispositions, attitudes, etc. A consequentialist might argue that we shouldn’t communicate blame if it would cause worse consequences than if we kept it to ourselves.

For example, if a child does something wrong, a consequentialist might say that sometimes it’s better to not outwardly blame them and instead do something else. Perhaps give them the tools to fix the mistake or praise them for a different aspect of the situation that they did well.

Less intuitively, though, is the implication that sometimes it will be wrong to blame someone for something, even if they deserve it! Say you have a friend who is very contrarian and does the wrong thing on purpose to get attention. Some consequentialists might say that it is wrong to communicate blame to them because under these circumstances you’re encouraging the behaviour, since they want the attention of being blamed. This might be a frustrating conclusion for people who think others get what they deserve by being blamed.

A deontologist might help them here and say that if someone is blameworthy then they deserve to be blamed and it is our duty to blame them, regardless of the consequences. Some deontologists might say that as long as our intentions are good, then we have a responsibility to blame wrongdoers and show them their moral failing.

Some different issues arise with that. Does this mean we are obligated to blame someone who “deserves it”? What about in situations where blaming would have really bad consequences? Is it still our duty to blame them for their wrongdoing?

Next time you go to blame someone, think about your intentions and what you are hoping to achieve by taking that action. It might be that you’re better off keeping it to yourself or finding a more positive way to frame the situation. Maybe the best consequences are to be gained by blaming or maybe you do just deserve to get that frustration off your chest.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why hard conversations matter

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

ExplainerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 23 JUL 2021

Imagine waking up in a bed, disoriented, bleary-eyed and confused.

You can’t remember how you got to there, and the bed you’re in doesn’t feel familiar. As you start to get a sense of your surroundings, you notice a bunch of medical equipment around. You notice plugs and tubes coming out of your body and realise you’re back-to-back with another person.

A glimpse in the mirror tells you the person you’re attached to is a world-famous violinist – one with a fatal kidney ailment. And now, you start to realise what’s happened. Last night, you were invited to be the guest of honour at an event hosted by the Society of Music Lovers. During the event, they told you about this violinist – whose prodigious talent would be taken from the world too soon if they couldn’t find a way to fix him.

It looks like, based on the medical records strewn around the room, the Society of Music Lovers have been scouring the globe for someone whose blood type and genetic markers are a match with the violinist.

A doctor enters the room, looking distressed. She informs you that the Society of Music Lovers drugged and kidnapped you, and had your circulatory system hooked you up to the violinist. That way, your healthy kidney can extract the poisons from the blood and the violinist will be cured – and you’ll be completely healthy at the end of the process. Unfortunately, the procedure is going to take approximately 40 weeks to complete.

“Look, we’re sorry the Society of Music Lovers did this to you–we would never have permitted it if we had known,” the doctor apologises to you. “But still, they did it, and the violinist is now plugged into you. To unplug you would be to kill him. But never mind, it’s only for nine months. By then he will have recovered from his ailment and can safely be unplugged from you.”

After all, the doctor explains, “all persons have a right to life, and violinists are persons. Granted you have a right to decide what happens in and to your body, but a person’s right to life outweighs your right to decide what happens in and to your body. So you cannot be unplugged from him.”

This thought experiment originates in American philosopher Judith Jarvis Thompson’s famous paper ‘In Defence of Abortion’ and, in case you hadn’t figured it out, aims to recreate some of the conditions of pregnancy in a different scenario. The goal is to test how some of the moral claims around abortion apply to a morally similar, contextually different situation.

Thomson’s question is simple: “Is it morally incumbent on you to accede to this situation?” Do you have to stay plugged in? “No doubt it would be very nice of you if you did, a great kindness. But do you have to accede to it?” Thomson asks.

Thomson believes most people would be outraged at the suggestion that someone could be subjected to nine months of medical interconnectedness as a result of being drugged and kidnapped. Yet, Thomson explains, this is more-or-less what people who object to abortion – even in cases where the pregnancy occurred as a result of rape – are claiming.

Part of what makes the thought experiment so compelling is that we can tweak the variables to mirror more closely a bunch of different situations – for instance, one where the person’s life is at risk by being attached to the violinist. Another where they are made to feel very unwell, or are bed-ridden for nine months… the list goes on.

But Thomson’s main goal isn’t to tweak an admittedly absurd scenario in a million different ways to decide on a case-by-case basis whether an abortion is OK or not. Instead, her thought experiment is intended to show the implausibility of the doctor’s final argument: that because the violinist has a right to life, you are therefore obligated to be bound to him for nine months.

“This argument treats the right to life as if it were unproblematic. It is not, and this seems to me to be precisely the source of the mistake,” she writes.

Instead, Thomson argues that the right to life is, actually, a right ‘not to be killed unjustly’.

Otherwise, as the thought experiment shows us, the right to life leads to a situation where we can make unjust claims on other people.

For example, if someone needs a kidney transplant and they have the absolute right to life – which Thomson understands as “a right to be given at least the bare minimum one needs for continued life” – then someone who refused to donate their kidney would be doing something wrong.

Thinking about a “right to life” leads us to weird conclusions, like that if my kidneys got sick, I might have some entitlement to someone else’s organs, which intuitively seems weird and wrong, though if I ever need a kidney, I reserve the right to change my mind.

Interestingly, Thomson’s argument – written in 1971 – does leave open the possibility of some ethical judgements around abortion. She tweaks her thought experiment so that instead of being connected to the violinist for nine months, you need only be connected for an hour. In this case, given the relatively minor inconvenience, wouldn’t it be wrong to let the violinist die?

Thomson thinks it would, but not because the violinist has a right to use your circulatory system. It would be wrong for reasons more familiar to virtue ethics – that it was selfish, callous, cruel etc…

Part of the power of Thomson’s thought experiment is to enable a sincere, careful discussion over a complex, loaded issue in a relatively safe environment. It gives us a sense of psychological distance from the real issue. Of course, this is only valuable if Thomson has created a meaningful analogy between the famous violinist and what an actual unwanted pregnancy is like. Lots of abortion critics and defenders alike would want to reject aspects of Thomson’s argument.

Nevertheless, Thomson’s paper continues to be taught not only as an important contribution to the ethical debate around abortion, but as an excellent example of how to build a careful, convincing argument.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

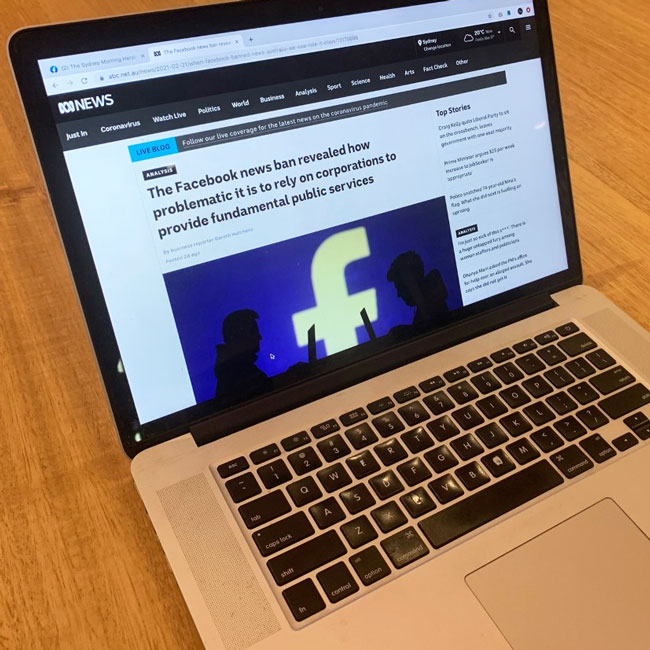

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

COP26: The choice of our lives

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Love and morality

Love has historically played a big role in how we understand the task of treating other people well. Many moral systems hold that love is foundational to doing right.

The Bible, for example, commands us to “love thy neighbour” – not merely to respect or value them, but to love them. Thousands of years later, philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch wrote that “loving attention” is the core of morality.

In our contemporary understanding of the word, love seems to involve partiality. In all kinds of settings from romantic love to the love in friendship or familial love, loving people seems to mean not loving others. We love our wife, not our neighbours’ wife. We love our friends and our parents, not our boss’ friends or our bus drivers’ father.

In fact, we might think that someone does not love their spouse in any meaningful sense of the word if they also say they love all other people equally – the celebrated essence of love seems to involve choosing some people over others.

This partiality affects our actions as well as our emotions: our parents, friends, and spouses receive more prioritisation, gifts, and emotional attention from us than strangers. This is a celebrated and joyful feature of human life.

Could love in fact be immoral – or amoral? Could behaving lovingly and behaving ethically be two separate tasks – tasks that might sometimes come into conflict?

Morality, has often been thought of as essentially neutral. That is, the moral gaze looks at everyone as equals; not favouring one person over another simply because of our relationship with them. Kantian ethicists, for instance, hold that all people deserve ethical treatment simply because they are persons.

Anyone who is a person deserves to have others not lie to them, disrespect them, enslave their body or seize their property. Thus, the only thing the moral gaze is concerned with is whether someone is a person – and since all people are persons, the moral gaze looks upon all of us equally.

Consequentialist ethics contains a similar commitment to neutrality. For a consequentialist, the moral measure of an action is whether it maximises value. Whose value is maximised has no special claim to our attention; the more value, the better, whether it accrues to my mother or to yours. Since the moral gaze looks to creating the most happiness, it looks at all people equally – as equal vectors of possible happiness.

If morality contains a commitment to neutrality – and if love contains a commitment to partiality – then the moral gaze and the loving gaze might conflict. It might even be the case that love demands acting in ways that morality seems to forbid.

Imagine that you are on a ship which begins to sink. You have held onto the railing but other passengers have not been so lucky, and in the water before you are several strangers struggling to stay afloat. Also in the water, struggling alongside the strangers, is your wife. Are you permitted to throw your wife the one remaining life jacket? Or is her right to life no stronger than any of the strangers’? Love seems to demand that we save our wife, but morality, if it is neutral, seems to offer no automatic reason why we should.

The philosopher Bernard Williams saw a way out of this puzzle. He argued that any person standing on the boat in this situation, who starts thinking about what morality demands, might reasonably be charged with having “one thought too many”. The person should not think “my wife is in the water – what does morality require I do?”. They should simply think “my wife is in the water,” and throw the life jacket.

Williams’ view was that a morally good person is not always thinking about what is morally justifiable. Perhaps, counterintuitively, being a truly ethical person means not always looking through the moral gaze. The question still remains – do love and morality ask us for different things?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is existentialism due for a comeback?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

WATCH

Relationships

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Particularism

When we ask ‘what is it ethical for me to do here?’, ethicists usually start by zooming out.

We look for an overarching framework or set of principles that will produce an answer for our particular problem. For instance, if our ethical dilemma is about eating meat, or telling a white lie, we first think about an overarching claim – “eating meat is bad”, or “telling lies is not permissible”.

Then, we think through what could make that overarching claim true: what exactly is badness? The hope is that we will be able to come up with an independently-justified, holistic view that can spit out a verdict about any particular situation. Thus, our ethical reasoning usually descends from the universal to the particular: badness comes from causing harm, eating meat causes harm, therefore eating meat is bad, therefore I should not eat this meat in front of me.

This methodology has led to the development of many grand unifying ethical systems; frameworks that offer answers to the zoomed-out question “what is it right to do everywhere?”. Some emphasise maximising value; others doing your duty, perfecting your virtue, or acting with love and care. Despite their different answers, all these approaches start from the same question: what is the correct system of ethics?

One striking feature of this mode of ethical enquiry is how little it has agreed on over 4,000 years. Great thinkers have been wondering about ethics for at least as long as they have wondered about mathematics or physics, but unlike mathematicians or natural scientists, ethicists do not count many more principles as ‘solid fact’ now than their counterparts did in Ancient Greece.

Particularists say this shows where ethics has been going wrong. The hunt for the correct system of ethics was doomed before it set out: by the time we ask “what’s the right thing to do everywhere?”, we have already made a mistake.

According to a particularist, the reason we cannot settle which moral system is best is that these grand unifying moral principles simply do not exist.

There is no such thing as a rule or a set of principles that will get the right answer in all situations. What would such an ethical system be – what would it look like; what is its function? So that when choosing between this theory or that theory we could ask ‘how well does it match what we expect of an ethical system?’.

According to the particularist, there is no satisfactory answer. There is therefore no reason to believe that these big, general ethical systems and principles exist. There can only be ethical verdicts that apply to particular situations and sets of contexts: they cannot be unified into a grand system of rules. We should therefore stop expecting our ethical verdicts to have a universal-feeling structure, like “don’t lie, because lying creates more harm than good”.

What should we expect our ethical verdicts to feel like instead? What does particularism say about the moment when we ask ourselves “what should I do?”. The particularist’s answer is mainly methodological.

First, we should start by refining the question so that it becomes more particular to our situation. Instead of asking “should I eat meat?” we ask “should I eat this meat?”. The second thing we should do is look for more information – not by zooming out, but by looking around. That is, we should take in more about our exact situation. What is the history of this moment? Who, specifically, is involved? Is this moment part of a trend, or an isolated incident?

All these factors are relevant, and they are relevant on their own: not because they exemplify some grand principle. “Occasion by occasion, one knows what to do, if one does, not by applying universal principles, but by being a certain kind of person: one who sees situations in a certain distinctive way”, wrote John McDowell.

Particularism, therefore, leaves a great deal up to us. It conceives of being ethical as the task of honing an individual capacity to judge particular situations for their particulars. It does not give us a manual – the only thing it tells us for certain is that we will fail if we try to use one.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Thought Experiment: The Last Man on Earth

Thought Experiment: The Last Man on Earth

ExplainerClimate + Environment

BY The Ethics Centre 18 MAY 2021

Imagine for a second that the entire human race has gone extinct, with the exception of one man.

There is no hope for humankind to continue. We know, as a matter of certainty, that when this person dies, so too does the human race.

Got it? Good. Now, imagine that this last person spends their remaining time on Earth as an arbiter of extinction. Being themselves functionally extinct, they make it their purpose to eliminate, painlessly and efficiently, as much life on Earth as possible. Every living thing: animal, plant, microbe is meticulously and painlessly put down when this person finds it.

Intuitively, it seems like this man is doing something wrong. But according to New Zealand philosopher Richard Sylvan (though his argument was published under the name Richard Routley before he took his wife’s name when he married in 1983), traditional ethical theories struggle to articulate exactly why what they’re doing is wrong.

Sylvan, developing this argument in the 1960’s, argues that traditional Western ethics – which at the time consisted largely of variations of utilitarianism and deontology – rested on a single “super-ethic”, which states that people should be able to do what they wish, so long as they don’t harm anyone – or harm themselves irreparably.

A result of this super-ethic is that the dominant Western ethical traditions are “simply inconsistent with an environmental ethic; for according to it nature is the dominion of man and he is free to deal with it as he pleases,” according to Sylvan. And he has a point: traditional formulations of Western ethics have tended to exclude non-human animals (and even some humans) from the sphere of ethical concern.

Traditional formulations of Western ethics have tended to exclude non-human animals (and even some humans) from the sphere of ethical concern.

In fairness, utilitarianism has a better history with considering non-human animals. The founder of the theory, Jeremy Bentham, insisted that since animals can suffer, they deserve moral concern. But even that can’t criticise the actions of our last person, who delivers painless death, free of suffering.

Plus, most versions of utilitarianism focus on the instrumental value of things (basically, their usefulness). Rarely do we consider the fact that when we ask “is it useful?” we’re making an assumption about the user – that they’re human.

Immanuel Kant’s deontology begins with the belief that it is human reason that gives rise to our dignity and autonomy. This means any ethical responsibilities and claims only exist for those who have the right kind of ability: to reason.

Now, some Kantian scholars will argue that we still shouldn’t treat animals or the environment badly because it would make us worse people, ethically speaking. But that’s different to saying that the environment deserves our ethical consideration in its own right. It’s like saying bullying is wrong because it makes you a bad person, instead of saying bullying is wrong because it causes another person to suffer. It’s not all about you!

Sylvan describes this view as “human chauvinism”. Today, it’s usually called “anthropocentrism”, and it’s at the heart of Sylvan’s critique. What kind of a theory can condone the kind of pointless destruction that the Last Man thought experiment describes?

Since Sylvan published, a lot has changed – especially with regard to the animal rights movement. Indeed, Australian philosopher Peter Singer developed his own version of consequentialism precisely so he could address some of the problems the theory had in explaining the moral value of animals. And we can now pretty easily say that modern ethical theories would condemn the wholesale extinction of animal life from the planet, just because humans were gone.

But the questions go deeper than this. American philosopher Mary Anne Warren creates a similar thought experiment. Imagine a lab-grown virus gone wrong, that wipes out all human and animal life. That would be bad. Now, imagine the same virus, but one that wiped out all human, animal and plant life. That would, she thinks, be worse. But why?

What is it that gives plants their ethical status? Do they have intrinsic value – a value in and of themselves, or is their value instrumental – meaning they’re good because they help other things that really matter?

One way to think about this is to imagine a garden on a planet with no sentient life. Is it better, all things considered, for this garden to exist than not? Does it matter if this garden withers and dies?

Or to use a real-life example: who suffered as a result of the destruction of the Jukaan Gorge – a sacred site to the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people? Western thought conceptualises this as wrong to destroy this site because it was sacred to people. But for Indigenous philosophical traditions, the destruction was a harm done to the land itself. The land was murdered. The suffering of people is secondary.

Sylvan and others who call for an ecological ethic, believe the failure for Western ethical thought to conceptualise of murdered land or what is good for plants is an obvious shortcoming.

This is revealed by our intuition that the careless destruction of the Last Man on Earth is wrong, even if we can’t quite say why.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

This is what comes after climate grief

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment

Why it was wrong to kill Harambe

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Society + Culture

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Moral Relativism

Moral relativism is the idea that there are no absolute rules to determine whether something is right or wrong. Unlike moral absolutists, moral relativists argue that good and bad are relative concepts – whether something is considered right or wrong can change depending on opinion, social context, culture or a number of other factors.

Moral relativists argue that there is more than one valid system of morality. A quick glance around the world or through history will reveal that no matter what we happen to believe is morally right and wrong, there is at least one person or culture that believes differently, and holds their belief with as much conviction as we do.

This existence of widespread moral diversity throughout history, between cultures and even within cultures, has led some philosophers to argue that morality is not absolute, but rather that there might be many valid moral systems: that morality is relative.

Understanding Moral Relativism

It’s worth pointing out that the philosophical notion of moral relativism is quite different from how the term is often used in everyday conversation. Many people have been known to say that others are entitled to their views and that we have no right to impose our view of morality on them.

This might look like moral relativism, but in many cases it’s really just an appeal for tolerance in a pragmatic or diplomatic sense, while the speaker quietly remains committed to their particular moral views. Should that person be confronted with what they consider a genuine moral violation, their apparent tolerance is likely to collapse back into absolutism.

Moral relativism is also often used as a term of derision to refer to the idea that morality is relative to whatever someone happens to believe is right and wrong at the time. This implies a kind of radical anything-goes moral nihilism that few, if any, major philosophers have supported. Rather, philosophers who have advocated for moral relativism of some sort or another have offered far more nuanced views. One reason to take moral relativism seriously is the idea that there might be some moral disagreements that cannot be conclusively resolved one way or the other.

If we can imagine that even idealised individuals, with perfect rationality and access to all the relevant facts, might still disagree over at least some contentious moral matters – like whether suicide is permissible, if revenge is ever justified, or whether loyalty to friends and family could ever justify lying – then this would cast doubt on the idea that there is a single morality that applies to all people at all times in favour of some kind of moral relativism.

Exploring Relativity

The key question for a moral relativist is what morality ought to be relative to. Gilbert Harman, for example, argues that morality is relative to an agreement made among a particular group of people to behave in a particular way. So “moral right and wrong (good and bad, justice and injustice, virtue and vice, etc.) are always relative to a choice of moral framework. What is morally right in relation to one moral framework can be morally wrong in relation to a different moral framework.

And no moral framework is objectively privileged as the one true morality.

It’s like different groups playing different codes of football, wherein one code a handball might be allowed but in another, it’s prohibited. So whether handball is wrong is simply relative to which code the group has agreed to play.

Another philosopher, David Wong, argues for “pluralistic relativism,” whereby different societies can abide by very different moral systems. So morality is relative to the particular system they have constructed to solve internal conflicts and respond to the social challenges their society faces.

However, there are objective facts about human nature and wellbeing that constrain what a valid moral system can look like, and these constraints “are not enough to eliminate all but one morality as meeting those needs.” They do eliminate perverse systems, like Nazi morality that would justify genocide, but allow for a wide range of other valid moral views.

Moral relativism is a much misunderstood philosophical view. But there is a range of sophisticated views that attempt to take seriously the great diversity of moral systems and attitudes that exist around the world, and attempts to put them in the context of the social and moral problems that each society faces, rather than suggesting there is a single moral code that ought to apply to everyone at all times.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Senior Philosopher at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr Tim Dean 18 JAN 2021

Liberalism is founded on the belief that individual freedom should be the basis of a just society.

Who should decide how you live your life: where you reside; what career you choose; whom you can marry; and which gods you worship? Should it be your parents? Or your religious or community leaders? Should it be determined by the circumstances of your birth? Or perhaps by your government? Or should you ultimately be the one to decide these things for yourself?

If you answered the latter, then you’re endorsing the values of liberalism, at least in the broadest sense. Liberalism is, at its heart, the belief that each individual person has moral priority over their community or society when it comes to determining the course of their life.

This primacy of individual freedom and self-determination might seem self-evident to people living in modern liberal democracies, but it is actually a relatively recent innovation.

The Birth of Liberalism

In most societies throughout history and prehistory, one’s beliefs, values and social role were imposed on them by their community. Indeed, in many societies since agricultural times, people were considered to be the property of their parents or their rulers, with next to no-one having genuine freedom or the power of self-determination.

Brave (or foolhardy) was the medieval serf who took it upon themselves to defy their local church to practice their own religion, or defy their family tradition to seek out their dream job, or defy their clan to marry whomever their heart desired.

The seeds of modern liberalism were planted in England in the 13th century with the signing of the Magna Carta, which weakened the unilateral power of the King over his minions. This started a process that eventually enshrined a number of individual rights in English law, such as a right to trial by jury and equality before the law.

Soon even rulers – whether monarch or government – came to receive their legitimacy not from divine authority, tradition or fiat but from the will of the people. If the rulers didn’t operate in the interests of the people, the people had the right to strip that legitimacy from them. This made democracy a natural fit for nations with liberal sensibilities.

The other motivating force for liberalism was the horrifically destructive religious wars that wracked Europe after the Reformation, culminating in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. Given the millions of lives lost due to religious and ideological differences, many people came to see that tolerance of different beliefs and religious practices might be a better alternative to imposing one’s beliefs on others by force.

Modern Liberalism

Liberalism was fleshed out as a comprehensive political philosophy by thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Locke and John Stuart Mill, and more recently by John Rawls. While they differed in their emphases and recommendations, all liberal thinkers were committed to the core idea that individuals were – and ought to be – fundamentally free to live as they choose.

Philosopher John Locke argued that liberalism stemmed from our very nature, arguing that all people are essentially in “a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of Nature, without asking leave or depending upon the will of any other man.”

Most liberal thinkers argued that individual freedom should only be limited in very special circumstances.

One of those limitations was not impinging upon the freedom of others to live according to their own beliefs and values, hence the importance of tolerance and preventing harm against others. As they say, your freedom to swing your arm ends where another person’s nose begins.

One common theme of liberalism is the importance of free speech. John Stuart Mill, for example, argued that each individual ought to be able to seek the truth for themselves rather than being obliged to accept the views imposed on them by authorities or tradition.

And in order to seek truth, they need to be able to explore, express and interrogate all beliefs and arguments. And the only way to do that was to allow wide-ranging free speech. “There ought to exist the fullest liberty of professing and discussing, as a matter of ethical conviction, any doctrine, however immoral it may be considered,” he wrote.

This freedom of speech should be limited only in very particular circumstances, such as when that speech is likely to cause direct harm to others. So shouting “fire” in a packed theatre when no such fire exists is an abuse of free speech.

This “harm principle” is still a topic of considerable debate amongst liberals and their opponents, especially around what ought to be considered sufficient harm to justify suppressing speech.

Other liberal thinkers emphasised the fact that not every person was equally able to exercise their freedom through no fault of their own. Poverty, sexism, racial discrimination and other systemic barriers mean that freedom and power are unequally distributed.

This led to what is often called “social justice” liberalism, which seeks to remove those social barriers and enable all people to exercise their freedom to the fullest extent. Some focused on economic redistribution, such as the liberal socialists, while others focused on social barriers, like feminists and anti-discrimination campaigners.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Deontology

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Can robots solve our aged care crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership