We can help older Australians by asking them for help

We can help older Australians by asking them for help

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 26 AUG 2022

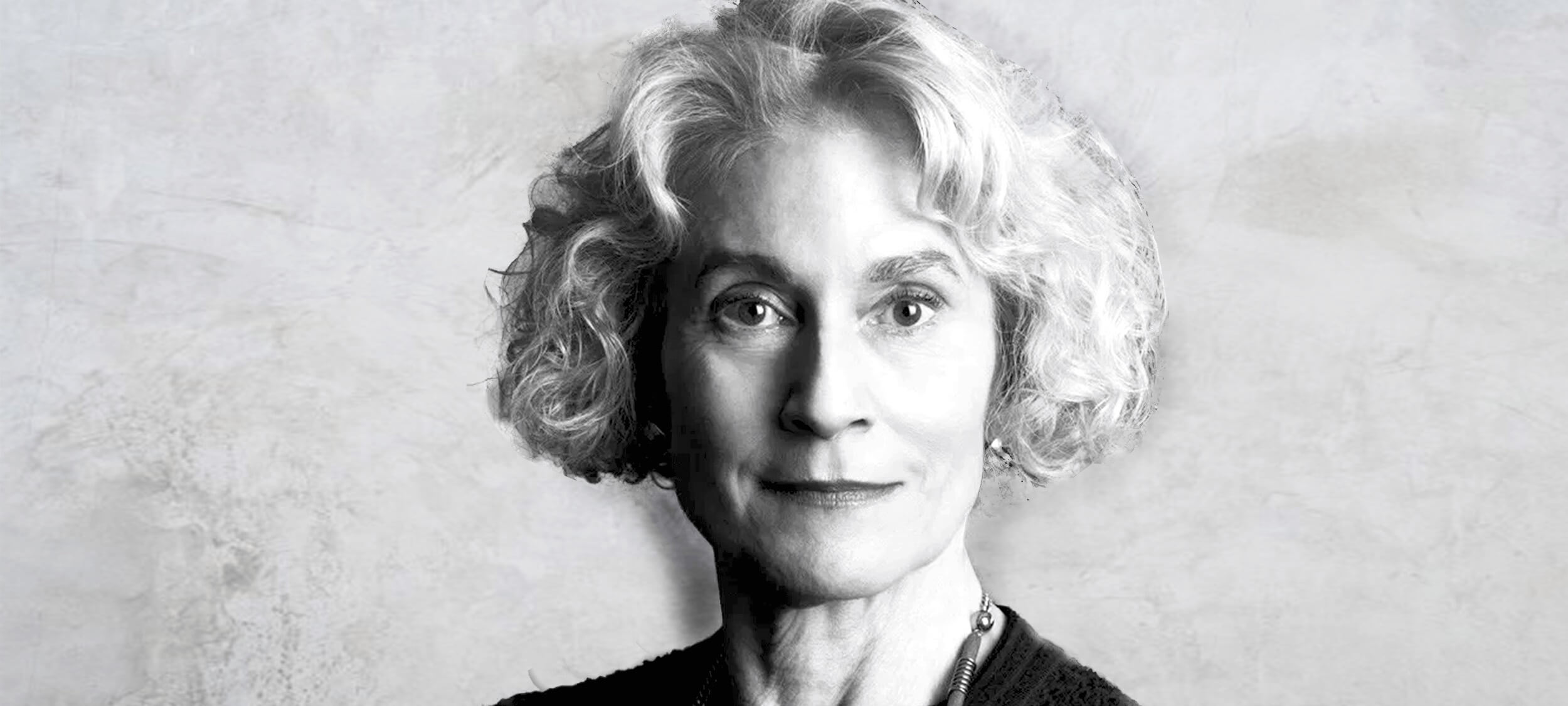

Older people are often undervalued and overlooked in our society – to their detriment, and ours.

A stranger knocked on our door the other day. She was promoting a service for older people who live alone. To counter the risk of an accident or sudden illness going unnoticed, a person could sign up to have a Red Cross volunteer call them every day.

It was heart-warming and heart-breaking; wonderful that an organisation was intervening to address the frightening risk of solitary suffering, terrible that the risk was so pervasive that it warranted an organisation intervening.

I was reminded of an initiative based in Africa that I’d heard about on Maya Shanka’s podcast A Slight Change of Plans, one that wasn’t designed to help older people, but to enlist their help.

The Friendship Bench was started in Zimbabwe by psychiatrist Dr Dixon Chibanda. Its goal was to alleviate pressure on the country’s health system by training ‘grandmothers’ (respected older women in the community) to meet people with common mild-to-moderate mental health disorders at a park bench, let them talk through their problems, and help them choose just one to try and solve.

Prospective volunteers, not to mention many of Chibanda’s peers, were sceptical at first, but he didn’t just train the grandmothers—he let them train him.

As a psychiatrist, Chibanda was schooled to avoid telling his own story or being vulnerable; his volunteers taught him the key to connecting with a person and building trust was a willingness to bend this rule.

They also told him that calling the park benches where the therapy took place ‘mental health benches’ as he’d planned would create such a stigma that no one would show up. Taking their advice, he renamed them ‘friendship benches’.

Randomised control trials have since shown therapy from trained community grandmothers to be remarkably effective. Better still, the volunteers benefit richly, gaining “a profound sense of purpose and a sense of belonging” from the work. “It’s a win/win,” Chibanda told Shanka. The “grandmothers” are helping people, “but it’s helping them too”.

Chibanda says one of the things he’s learned from the Friendship Bench is just how important connection is. The therapy doesn’t really start, he says, until the moment people connect.

The scheme has since been rolled out elsewhere; Chibanda says he’d like to see friendship benches all over the world. But I suspect the barriers in places like Australia would be even greater than those faced in Africa; not because of stigma surrounding mental health, but because of stigma surrounding “the elderly”.

Chibanda says his volunteers were considered custodians of local wisdom and culture. But in more individualistic, materialistic cultures, there’s a tendency to depict older people as burdensome instead.

From useless to used

Sarah Holland-Batt’s 2020 essay Magical Thinking and the Aged-care Crisis explores this tendency. She discusses inheritance impatience, elder abuse and mandated euthanasia in dystopian fiction, then declares: “the apocalypse has already arrived for Australia’s elderly”.

“We treat older people as a separate and subhuman class, frequently viewing them as a burden on their families, the community and the state,” she writes.

Immanuel Kant argued against treating people as mere resources, but according to Holland-Batt, our aged-care industry does precisely this; it mines people for profit. If Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre was right when he said the way we treat “the very young and the very old, the sick, the injured, and the otherwise disabled” is an important indicator of a community’s flourishing, ours is falling short.

I think of the way I’ve heard Indigenous people speak about their elders—with reverence and respect; of the biblical command to honour one’s parents; of the proverb that describes grey hair as a ‘crown of glory’.

When did assuming people have nothing more to offer once they’re ‘old’ become acceptable? When did we stop treasuring the kind of wisdom that builds with experience? And how dearly has it cost us?

A closer relationship, a broader perspective

What I loved most about the Friendship Bench was the image it evoked of people from different generations sitting side by side. I loved the underlying assumption that the elderly among us still have much to offer: an offering so unique they were the key to the initiative’s success. I also loved the idea the therapy took place not under fluorescent light, but shining sun.

The fact the volunteers benefited just as much as those they were there to help did not surprise me. Who doesn’t want to put the lessons learnt over the years to use? To see somebody suffering, and help? Not all, I grant, but many—maybe most.

If only Australia’s discussions about aged care were less reactive and more proactive. If only there were less talk of problems and more of potential.

Yes, as we grow old, we grow more dependent and less capable; we cannot deny the reality of declining physical and sometimes mental functioning. But our bodies will impose enough limits without generalised assumptions based on age imposing more. I know of people in their nineties who still work as volunteers. We’re all unique; our ageing and its timing will be too. And even when age does stop us from helping, makes us start depending more, it cannot take our value, our worthiness of care, respect, and love.

The biggest game-changer I can imagine when it comes to the way our society views and treats its older members, is a rise in intergenerational connection—better still, friendship.

In some respects, our society is more connected than ever before, but not in the ways that count the most. If we want to tackle loneliness, depression and despair, this must change. We not only have to change the way we act, we must change the way we think. ‘The elderly’ need us, and we need them.

Examine what it means to age and grow older, and how this impacts all our lives. Join us for The Ethics of Being Old on Thur 24 Oct 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Epistemology

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Come join the Circle of Chairs

More than thirty years ago, philosopher and Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, Dr Simon Longstaff AO placed a dozen chairs in a circle in Martin Place in the centre of Sydney’s busy CBD. Next to them he put up a sign that said: “If you would like to discuss ideas with a philosopher join the circle”.

At first, the circle attracted little more than sidelong glances from curious passers-by. But it wasn’t long before people paused to read the sign, a few of them taking up the offer to occupy one of the chairs and start a conversation. Soon the circle was full and the discussion buzzing.

Simon discovered that many people had an unsated appetite for a different kind of conversation than the one that usually unfolded with friends, family and colleagues or, heaven forbid, online.

This was a kind of conversation where they could open up and express their deepest beliefs and attitudes, where they could ask questions without people presuming the worst about them, where they could have their ideas challenged without feeling judged or threatened, and where they could explore a topic before making up their mind.

Simon returned regularly to Martin Place with his circle of chairs, and each time more and more people stopped by to discuss ideas with him and the others seated around the circle. People started to come from far and wide to join in the conversation, having heard about it from friends or family. Rarely were chairs left empty.

With his Circle of Chairs, Simon had effectively created a space where people were safe to talk about difficult and challenging subjects. What made it work was that it wasn’t just free and unregulated discourse. Simon was able to bring his skills as a philosopher to facilitate the conversation and set appropriate norms that enabled people to speak and listen in good faith in ways that are difficult to achieve in everyday conversations.

This exercise all those years ago served as a crucial spark that led to the creation of The Ethics Centre, which still works to create safe spaces to discuss difficult and important subjects to this day.

Welcome to the conversation

Presented by The Ethics Centre, Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) is Australia’s original disruptive festival. By holding uncomfortable ideas up to the light and challenging thinking on some of the most persevering and difficult issues of our time, FODI aims to question our deepest held beliefs and desires.

Which is why Dr Simon Longstaff’s original vision of a Circle of Chairs is returning to this year’s FODI, in partnership with JobLink Plus. With six sessions held over the two days, we’re inviting festival goers to take up a chair and sit shoulder to shoulder with leading philosophers Dr Simon Longstaff, Dr Tim Dean and Dr Kelly Hamilton, who will be joined by special guest conversationalists to unpick some of modern life’s most dangerous ethical dilemmas.

Will you agree with your fellow FODI attendee’s views? Pull up a chair and join or simply watch the guided conversations unfold as together we examine how we’re really feeling, thinking and doing.

We hope to see more safe spaces opening up outside of FODI to help us all have the opportunity to share our authentic views and tackle the most challenging, and important, questions that we face today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Freedom and disagreement: How we move forward

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 1 AUG 2022

There are certain things that some of us choose and do not choose, to tell those who we work with.

You come in on a Monday, and you stand around the coffee machine (the modern-day equivalent of the water cooler), and somebody asks you: “so, what did you get up to this weekend?”

Then you have a choice. If you fought with your partner, do you tell your colleague that? If you had sex, do you tell them that? If your mother is sick, or you’re dealing with a stress that society has broadly considered “intimate” to reveal, do you say something? And if you do, do you change the nature of the work relationship? Do you, in a phrase, “freak people out?”

These social conditions – norms, established and maintained by systems – are not specific to work, of course. Most spaces that we enter into and share with other people have an implicit code of conduct. We learn these codes as children – usually by breaking the rules of the codes, and then being corrected. And then, for the rest of our lives, we maintain these codes, often without explicitly realising what we are doing.

There are things you don’t say at church. There are things you do say in a therapist’s office. This is a version of what is called, in the world of politics, the “Overton Window”, a term used to describe the range of ideas that are considered “normal” or “acceptable” to be discussed publicly.

These social conditions are formed by us, and are entirely contingent – we could collectively decide to change them if we wanted to. But usually – at most workplaces, importantly not all – we don’t. Moreover, these conditions go past certain other considerations, about, say honesty. It doesn’t matter that some of us spend more time around our colleagues than those we call our partners. This decision about what to withhold in the office is frequently described as a choice about “professionalism”, which is usually a code word for “politeness.”

Severance, the new Apple television show which has been met with broad critical acclaim, takes the way that these concepts of professionalism and politeness shape us to its natural endpoint. The sci-fi show depicts an office, Lumon Industries, where employees are implanted with a chip that creates “innie” and “outie” selves.

Their innie self is their work self – the one who moves through the office building, and engages in the shadowy and disreputable jobs required by their employer. Their outie self is who they are when they leave the office doors. These two selves do not have any contact with, or knowledge of each other. They could be, for all intents and purposes, strangers, even though they are – on at least one reading – the “same person.”

The chip is thus a signifier for a contingent code of social practices. It takes something that is implicit in most workplaces, and makes it explicit. We might not consider it a “big deal” when we don’t tell Roy from accounts that, moments before we walked in the front door of the office, we had a massive blow-up over the phone with our partner. Which may help Roy understand why we are so ‘tetchy’ this morning. But it is, in some ways, a practice that shapes who we are.

According to the social practices of most businesses, it is “professional” – as in “polite” – not to, say, sob openly at one’s desk. But what if we want to sob? When we choose not to, we are being shaped into a very particular kind of thing, by a very particular form of etiquette which is tied explicitly to labor.

And because these forms of etiquette shape who we are, they also shapes what we know. This is the line pushed by Miranda Fricker, the leading feminist philosopher and pioneer in the field of social epistemology – the study of how we are constructed socially, and how that feeds into how we understand and process the world.

For Fricker, social forces alter the knowledge that we have access to. Fricker is thinking, in particular, about how being a woman, or a man, or a non-binary person, changes the words we have access to in order to explain ourselves, and thus how we understand things. That access is shaped by how we are socially built, and when we are blocked from access, we develop epistemic blindspots that we are often not even aware that we have.

In Severance, these social forces that bar access are the forces of capitalism. And these forces make the lives of the characters swamped with blindspots. Mark, the show’s hero, has two sides – his innie, and his outie. Things that the innie Mark does hurt and frustrate the desires of the outie Mark.

Both versions of him have such significant blindspots, that these “separate” characters are actively at odds. Much of the show’s first few episodes see these two separate versions of the same person having to fight, and challenge one another, with Mark striving for victory over outie Mark.

The forces of etiquette are always for the benefit of those in power. We, the workers at certain organisations, might maintain them, but their end result is that they meaningfully commodify us – make us into streamlined, more effective and efficient workers.

So many of us have worked a job that has asked us to sacrifice, or shape and change certain parts of ourselves, so as to be more “professional”. Which is a way of saying that these jobs have turned us into vessels for labour – emphasised the parts of us that increase productivity, and snipped off the parts that do not.

The employees of Lumon live sad, confused lives full of pain, riddled with hallucinations. The benefit of the code of etiquette is never to them. They get paid, sure. But they spend their time hurting each other, or attempting suicide, or losing their minds. Their titular severance helps the company, never them.

This is what the theorist Mark Fisher refers to when he writes about the work of Franz Kafka, one of our greatest writers when it comes to the way that politeness is weaponised against the vulnerable and the marginalized. As Fisher points out, Kafka’s work examines a world in which the powerful can manipulate those that they rule and control through the establishment of social conduct; polite and impolite; nice and not nice.

Thus, when the worker does something that fights back against their having become a vessel for labour, the worker can be “shamed”, the structure of etiquette used against them. This happens all the time in the world of Severance. As the season progresses, and the characters get involved in complex plots that involve both their innie and outie selves, the threat is always that the code of conduct will be weaponised against them, in a way that further strips down their personality; turns them into more of a vessel.

And, as Fisher again points out, because these systems of etiquette are for the benefit of the powerful, the powerful are “unembarrassable.” Because they are powerful – because they are the employer – whatever they do is “right” and “correct” and “polite.” Again, the rules of the game are contingent, which means that they are flexible. This is what makes them so dangerous. They can be rewritten underneath our feet, to the benefit of those in charge.

Moreover, in the world of the show, the characters “choose” to strip themselves of agency and autonomy, because of the dangling carrot of profit. This sharpens the satirical edge of Severance. It’s not just that the snaking rules of the game that we talk about when we talk about “good manners” make them different people. It’s that the characters of the show submit to these rules. They themselves maintain them.

Nobody’s being “forced”, in the traditional sense of that word, into becoming vessels for labour. This is not the picture of worker in chains. They are “choosing” to take the chip, and to work for Lumon. But are they truly free? What is the other alternative? Poverty? And what, actually, makes Lumon so different? A swathe of companies have these rules of etiquette. Which means a swathe of companies do precisely the same thing.

This is a depressing thought. But the freedom from this punishment lies, as it usually does, in the concept of contingency. Etiquette enforces itself; it punishes, through social isolation and exclusion, those who break its rules.

But these rules are not written on a stone tablet. And the people who are maintaining them are, in fact, all of us. Which means that we can change them. We can be “unprofessional.” We can be “impolite”. We can ignore the person who wants to alter our behaviour by telling us that we are “being rude.” And in doing so, we can fight back against the forces that want to make us one kind of vessel. And we can become whatever we’d like to be.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Can we celebrate Anzac Day without glorifying war?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Joanna Bourke

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 28 JUL 2022

We’re hurtling into a new age where the notion of evidence and knowledge has become muddied and distorted. So which rabbit hole is the right one to click through?

Our world is deeply divided, and we have found ourselves in a unique moment in history where the idea of rational thought seems to have been dissolved. It’s no longer as clear cut what is right and just to believe….So what does it mean to truly know something anymore?

According to Emerson, the number one AI chat bot in the world, “rational thought is the process of forming judgements based on evidence” which sounds simple enough. It’s easy to form judgements based on evidence when the object of judgement is tangible — this cheese pizza is delicious, a cat playing a keyboard wearing glasses is funny. These are ideas on which people from all sides of the political spectrum can come to some form of agreement (with a little friendly debate).

But what happens when the ideas become a little more lofty? It’s human nature to believe that our one’s ideas are rational, well reasoned, and based on evidence. But what constitutes evidence in these information rich times?

We’re hurtling into a new age where even the notion of “evidence” has become muddied and distorted.

So where do we even begin — which news is the real news and what’s the responsible way to respond to the news that someone as intelligent as you, in possession of as much evidence as you, believes a different conclusion?

Philosopher Eleanor Gordon-Smith suggests, “There are many, many circumstances in which we decline to avail ourselves of certain beliefs or certain candidate truths because we’re being very Cartesionally responsible and we’re declining to encounter the possibility of doubt. And meanwhile, those of us who are sort of warriors for the enlightenment of being very epistemically polite and trying to only believe those things that we’re allowed to do so on. The conspiracy theorists, meanwhile, consider themselves a veil of knowledge, which then they deploy in a very different way.”

Who gets to be smart?

Before the Enlightenment, the common man had no real business in the pursuit of knowledge, knowledge was very fiercely guarded by the Church and the Crown. But once it dawned on those honest folk that they could in fact have knowledge, it almost became a moral imperative to seize it, regardless of the obstacles.

Nowadays avoiding knowledge is an impossibility impossible. Access to information has been wholly democratised, if you’ve got a smart phone handy, any Google search will result in billions of possible pages and answers. It’s now your choice to determine which rabbit hole is the right one to click. To the untrained eye, there’s no differentiating between information that is thoroughly researched and fact checked and fake news. And according to Eleanor Gordon-Smith it is this saturation of knowledge has come to define our generation. So much so that the value of knowledge “has been subject to a kind of inflation”.

She asks, “how do you restore the emancipatory potential of knowledge that the Enlightenment founders saw? How do you get back the kind of bravery, the self development, the political resistance, the independence in the act of knowing in this particular moment…is there a way to restore the bravery and the value of knowledge in an environment where it’s so cheap and so readily available?”

It is this saturation of knowledge has come to define our generation. So much so that the value of knowledge “has been subject to a kind of inflation”.

Philosopher Slavoj Žižek suggests that perhaps our mistake is putting the Englightment on a pedestal, that those involved in the Enlightment’s pursuit of knowledge mischaracterised those who came before them as naive idiots. “Modernity is not just knowledge. It’s also on the other side, a certain regression to primitivity. The first lesson of good enlightenment is don’t simply fight your opponent. And that’s what’s happening today.”

Perhaps ignorance really is bliss

In the age of disinformation, misinformation and everything in between, admitting you don’t know something almost feels like an act of rebellion. American philosopher Stanley Cavell, boldly asked “how do we learn that what we need is not more knowledge but the willingness to forgo knowledge” (it’s worth noting that this line of questioning saw his publications banned from a number of American university libraries).

Sometimes it is better to be ignorant because, “true knowledge hurts. Basically, we don’t want to know too much. If we get to know too much about it, we will objectivise ourselves, we will lose our personal dignity, so to retain our freedom it’s better not to know too much.” – Žižek

Žižek however admits that we are in a the middle of the fight. We are not at the end of the story. We cannot afford ourselves this retroactive view in the sense of: who cares what is done is already done? “Philosophers have only interpreted the world, we have to change it. We tried to change the world too quickly without really adequately interpreting it. And my motto would have been that 20th century leftists were just trying to change the world. The time is also to interpret it differently. That’s the challenge.”

When the AI chat bot Emerson is asked, “how can you know if something is true” it responds, “truth is a matter of opinion” and given these tumultuous and divided times we are living through, there is perhaps no truer statement.

To delve deeper into the speakers and themes discussed in this article, tune into FODI: The In-Between The Age of Doubt, Reason and Conspiracy.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Joanna Bourke

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Agape

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Enough with the ancients: it's time to listen to young people

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Daniel Finlay Anna Goodman 6 JUL 2022

Nearly 20% of Australia’s population is between the ages of 10 and 24, yet their social and political voices are almost unheard. In our effort to amplify these voices, The Ethics Centre will be hosting a series of workshops where young people can help us better understand the challenges they face and the best ways for us to help. We’re listening.

You’re sitting at the dinner table at a big family gathering. Conversation starts to die down and suddenly your uncle says: “Have you seen that Greta girl on the news? I understand that climate change is a big deal, but the kids these days are so angry and loud. They’d get more done if they showed some respect.”

Many people under 25 have been in this position and had to make a choice about how to respond. This decision is often more difficult than it seems because there doesn’t seem to be a preferable option. Philosopher and feminist theorist Marilyn Frye gave a name to this kind of situation: a double-bind. In her essay Oppression, she defines the double-bind as a “situation in which options are reduced to a very few and all of them expose one to penalty, censure, or deprivation.”

Frye originally used the double-bind to talk about how women often found themselves in situations where they were going to be criticised equally for engaging with or ignoring gender stereotypes. The double-bind can be used to explain the difficult positions that anyone who experiences a negative stereotype finds themselves in and provides insight into why people with important perspectives often feel the need to censor themselves.

Let’s say we do choose to speak up. We can justify our anger. There are so many huge issues that impact the world – climate change, the pandemic, rampant inequality, and so on – and it feels like things are changing far too slowly.

Young people especially should be allowed to be angry, because this is the world we will inherit.

Unfortunately, it’s a common experience for younger generations to feel that their voices aren’t listened to or respected. Even though these reasons should more than justify the anger and frustration of young people, emotion can often (unjustly) obfuscate the reality of what we say.

So, let’s try the other way. We choose to not engage and instead let the comment slide. However, then we’re at risk of being seen as the “apathetic teen,” a narrative that has been perpetuated ad nauseam claiming that young people don’t really care about anything (which we know isn’t true).

Young people care about a lot, and have a lot to care about. Not only do they care, they act. A recent survey of 7,000 young people found that two-thirds of respondents seek out ways to get involved in issues they care about, and 64% believe that it is their personal responsibility to get involved in important issues. So, it’s not always easy to just let your uncle’s tone-policing go when you feel passionate about a topic, especially when staying silent can be as damaging as speaking up.

Here we see the double-bind in action: neither of the most obvious responses to the situation are favourable or even preferable. Because of a build-up of social and cultural assumptions and expectations, we’re often placed in a position where we seem to lose in some way no matter what we decide to do.

The Australian youth experience

Unfortunately, age discrimination towards young people doesn’t end at the dinner table. A 2022 survey conducted by Greens Senator Jordon Steele-John found that “overwhelmingly, young people are feeling ignored and overlooked”. Gen Z (people born between 1995 and 2010) are more likely to be viewed as “entitled, coddled, inexperienced and lazy,” which is having negative effects on young people’s confidence in the workplace. It doesn’t help that young people are hugely underrepresented in the Australian government and positions of power in the private sector.

Young people should not have to convince everyone that their voices are worth listening to. The combination of endless global issues and lack of representation in positions of power, which is compounded by a culture that doesn’t give appropriate weight to their contributions, creates a climate that leaves young people feeling frustrated and disempowered.

So, what can we do? As with most social issues, there isn’t one simple fix to the underrepresentation and misrepresentation of youth because it stems from a few different things that are ingrained in our society and culture. We can question our assumptions and those of others by recognising that “youth” as a social or cultural category isn’t really coherent anymore. There has been an enormous rise in the number of subcultures that are increasingly interconnected thanks to mass media and the internet, meaning that “young people” are more diverse than ever before.

Most importantly, we can bring young people together and into spaces where their voices will be heard by people who are in a position to make change.

As part of our mission to do just that, The Ethics Centre is developing a growing number of youth initiatives, like the Youth Advisory Council and the Young Writer’s Competition.

Through these initiatives, we are starting an ongoing conversation with young people about the areas in their lives and futures that they think ethics is needed the most.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 29 JUN 2022

In October of 2021, The New York Times published a long article called ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’, a story of kidney donations, poetic license, and vicious authors falling over one another to write damning words about those they publicly called their friends. Within hours of it hitting the internet, it had become the story of the day. And then the day after that. And then the day after that.

The thrust of ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ is simple. Seven years ago, an aspiring author named Dawn Dorland donated a kidney, a selfless act motivated – at least on first glance – by pure charity. Rather than let this act remain anonymous, Dorland instead posted about it frequently across the internet, particularly in a digital writer’s group she was part of. One of the members of that group, Sonya Larson, began murmuring to other authors about what she saw as Dorland’s shameless desire for attention, turning Dorland and her donation into a particularly damning punchline.

But rather than keep her takedowns to private messages, Larson wrote a not-so-veiled short fiction story about Dorland and her perceived bent towards self-celebration. Titled ‘The Kindest’, the story draws heavily on Dorland’s life, and turns her into a warped and twisted version of herself; too arrogant and self-involved to behave in a genuinely charitable way, motivated only by pride and sickening grandiosity. Flash forward a few years, and Dorland had launched legal action against Larson over the story, a protracted battle that serves as the climax for ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’

There is a good reason that the fallout between the two writers so firmly captured the attention of the internet. It’s not just the tone of ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’, the writing is unabashedly gossipy, filled with back-and-forths between Larson and Dorland that are laced with enough invective to make your toes curl. It’s that the story provided an opportunity for the internet to agonize over a very old argument, given new life in the era of streaming and a fixation on true crime: who has the right to tell another’s story?

This Is Your Life

We tend to believe that we are the authors of our own life story – that we have an essential and inalienable hold over our own narratives. There is nothing, so one cultural myth goes, as sacrosanct and personal as our identity.

As such, those who adopt this view on identity consider the act of turning another human being’s life into art to be one steeped in ethical conundrums: an issue of consent and privacy, where the wishes of the subject must be valued over the artistic decisions of the author.

These are the people who took Dorland’s side in the ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ argument. They are also the people who have a bone to pick with the recent glut of “ripped from the headlines” media content, from Hulu’s Pam & Tommy, a fictionalised version of the media fallout after the release of Pamela Anderson’s sex tape, to Inventing Anna, a series following the rise and fall of Anna Delvey (real name Sorokin), a socialite who scammed her way through America’s upper class.

In each of these cases, a real-life story – with, in many cases, real-life victims – has been shaped into fiction, often without the subject’s consent.

Anderson herself pushed against Pam & Tommy being made, while Sorokin wrote an angry letter about the series from her jail cell.

But to believe that you – and only you – can tell your own story is to believe in a shaky foundational premise. Such an argument rests on the idea that each of us is hermetically sealed away from the world, and hold important and relevant insight into ourselves that no others hold.

It is the case that we know certain things about our lives that others do not. But we are embedded in a web of social relations, and in the imaginations and minds of all those we encounter. We are not, in fact, the faultless experts on ourselves. Our personality, such as it is, is shaped and tested in the minds of those who receive us. The delineations between “my story” and “your story” or “our story” are shakier than it might first appear. We are constructed by the world, not sat in opposition to it.

Why This Argument? Why Now?

People’s sacrosanct belief in the importance of their own personal identity – treated as though our narratives about ourselves are delicate pieces of crystal we hold close to our chests, too fragile to let anyone else hold, is tied to a growing retreat from structural and systemic issues, and an embracing of personal ones. The ultimate social currency is often not based in the story of many, but the story of one. “I am me, and nobody else could be me, and for that reason, nobody else could tell my story but me.”

On the whole, the creative scope of the streaming giants, particularly Netflix, and major Western movie studios, has changed tremendously, from the cultural to the individual. Adam Curtis, the documentarian, has pointed this out, bemoaning the fact that there are few artists looking to describe how life right now feels. In America, Australia and the UK in particular, mainstream creatives have limited desire to capture any experience that expands beyond very particular lived ones, that are presented as isolated, and unique.

The theorist and philosopher Christopher Lasch covered this decades ago, in his groundbreaking work The Culture of Narcissism. He addressed what he saw as a tendency to go inwards: faced by a souring political climate, Lasch argued Americans had traded a hope for big change, with a fixation on smaller, more intimate and cosmetic shifts.

It is no surprise then that, though arguments around the ethics of storytelling have been waging for decades, they have been given new poignancy by the frequency of creative projects that fixate on only one life, and the increasingly popular belief that we are alone, and lonely, and utterly unlike even those from our same cultural and class background.

The beauty of art is that it need never be blinkered in this way. I am not advocating for only one type of art, the cultural instead of the personal – and I don’t believe that Curtis or Lasch are either. That’s one way of falling into precisely the artistic stalemate we find ourselves in. It’s not hopping from one mode of storytelling to another, it’s mixing the two, providing a rich, mainstream creative palette.

In fact, the problem is a creative fixation, one that has begun to dominate swathes of cultural discourse and entertainment. A generation of storytellers have settled themselves into a rut, hashing the same old beats over and over, telling stories with the same foundational premise – we are not like each other. In turn, that means our questions about so much mainstream art are becoming repetitive, the discourses surrounding ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ and Pam & Tommy and Inventing Anna just familiar talking points shot weakly through with a desperate, failing dose of adrenaline.

The question, asked over and over again, is: “Who can tell my story?” But perhaps we should ask why we even consider it “my” story in the first place.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What are we afraid of? Horror movies and our collective fears

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith 24 JUN 2022

In April 2021, partly in response to a series of high-profile sexual assault allegations, the Commonwealth government funded a set of educational videos about sexual consent. Safe to say, they did not do the job.

There was the infamous milkshake video, in which a girl smears ice cream on her partner’s face with a devious grin; one in which a taco is distinguished from a person by the fact that a taco cannot have preferences, and one set at a swimming pool, in which the desire to go for a swim is compared to the desire (or not) to have sex. The videos were condemned in ringing terms by educators and activists – they were “problematic”, an insult to students’ intelligence, or too flippant for the gravity of the subject.

Anyone who has sat through workplace or educational training about harassment and sexual boundaries knows what a difficult feat these videos had to pull off. It’s hard to talk about sex, because sex is not one thing – even between partners, much less across the population. This makes it hard, in turn, to talk about sexual ethics — there are many more ethical lenses available than the ethics of consent.

Sex ranges from the grave and the intimate to the flippant and the casual, from the depths of taboo to the frothiest of frivolities, from power and domination to play and healing, from authentic self-expression to pantomimed degradation. It is such a chimerical experience that it’s no wonder we struggle to talk about its morality in clear and unambiguous terms. No wonder our sexual ethics education materials can fall into a kind of “uncanny valley” – videos depicting wooden interactions between characters who at once are blithely unaware of sexual norms and calmly receptive to learning them, or oddly literal exchanges that feel like they’re discussing an experience almost, but not quite, entirely unlike sex.

How can sex be so operatic and so stone quotidian, so universal and so private, so dangerous and so familiar?

Why, when our sexual experiences are so many and so varied, do we hope that an ethics of consent will be able to accommodate them all?

If we wanted a more holistic approach to sexual ethics and education, which moral frameworks would we turn to?

Time was, if you wanted an ethics of sex, the psychoanalysts were the place to turn. Freudian analyses of desire located it squarely in the individual and the underbelly of their consciousness. Desire was seldom understood as something about which one could ask the questions of justice – Is it fair? Who deserves it? – or as a candidate for political analysis. But beginning in the 20th Century, a feminist perspective rejected this picture. Feminist philosophers and legal scholars like Catherine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin argued that desire was both an expression of and a means of enforcing the prevailing hierarchies of power. In Mackinnon’s “Pleasure Under Patriarchy”, she quotes poet Adrienne Rich’s Dialogues: “I do not know who I was when I did those things, or whether I willed to feel what I had read about”.

Once the questions of justice had been asked around sex – once it was pointed out that power and hierarchy do not stop at the door to the home or the bedroom – there emerged uneasy questions about how sexual unfairness could create demands of sexual fairness: for instance, does anyone have a right to sex? (This question has been explored by Oxford Professor Amia Srinivisan at length). Or can a person have a moral complaint when over and over again, they are rejected for sex; unable – through the aggregation of other people’s choices – to access an experience that everyone else says is one of life’s central joys?

Sexual desire has long discriminated along racial and disability lines – as Srinivasan notes, Asian men on dating apps or disabled people are frequently told to their faces that they are instantly rejected as prospective sexual partners because I would never sleep with someone like you. How can we make sense of the utter rigidity of the rule that nobody should have sex with anyone they don’t want to – alongside the possibility that those choices en masse enact a prejudice that each of us might individually deny? One more mystery for the ethics of sex; for the challenge of bringing justice to something as fraught as desire. As Srinivasan so memorably writes: “There is nothing else so riven with politics and yet so inviolably personal.”

In this morass of ethical grey, the concept of consent seemed to promise some black-and-white. We might not know the full list of our sexual rights, but an ethics of consent at least clearly names the sexual wrongs. The centrality of consent to sexual ethics is in fact a relatively recent development; the concept gained traction in the 1980s, at roughly the same time as the autonomous individual became the main character of political analysis. It was not long before then that “informed consent” was still a foreign notion in healthcare ethics, and that rape of a sex worker was often understood not as a violation of consent, but as theft of services.

Perhaps consent education reaches for simple metaphors like milkshakes, tacos, or cups of tea because an ethics of consent is simple – so simple we can say it in the familiar truism: “No means no”. But the trouble with centering consent in our sexual ethics is that it risks confusing ‘not-capital-B-Bad’ with ‘good’. Plenty of consensual sex is also cruel, harmful, selfish, painful, alienating, or subordinating.

Consensual sex is not necessarily ethical, nor even necessarily good. By treating non-consensual sex as the primary case about which to do sexual ethics – the jumping off point for our analysis and education – we risk introducing young people to sexual morality primarily through the category of wrong and how to avoid it, instead of through the lens of sexual joy and how to share it. Sex can be a way to connect with one another, to know, to be vulnerable, to give, to reveal, to trust – the intelligibility of aspiring to sex like this can be lost when the highest aspiration of our sexual ethics is “getting consent”.

By treating non-consensual sex as the primary case about which to do sexual ethics – the jumping off point for our analysis and education – we risk introducing young people to sexual morality primarily through the category of wrong and how to avoid it, instead of through the lens of sexual joy and how to share it.

One of the central tasks of an ethical life is to distinguish between the realm of duty – what can be demanded of us, and the realm of benevolence, what we can freely give, and to realise that the person who thinks only about their duties is in some ways a moral miser. An ethics of sex which prioritises duty by emphasising consent and permission can accidentally obscure the possibility of an ethics of benevolence – one which would not stop after asking what we owe to one another, but would carry on, asking how we might help them flourish.

To live an ethical life is more than avoiding wrong – how strange it would be to forget that in our most vivid encounters with others.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Is it ok to visit someone in need during COVID-19?

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 14 JUN 2022

We have built ourselves a lonely world but there are ways to forge the genuine human connections that we all need to flourish.

We live in a strange world. Consider the skill that many of us have carefully cultivated over years of city living of actively ignoring other people around us while hoping that those people will actively ignore us in return.

Think about how you enter a lift in a busy shopping centre or an office building. Perhaps a quick glance at those already standing inside, a small shuffle to ensure you’re not standing too close to anyone else, a quick tap of the “open door” button to allow a latecomer to enter, a fleeting smile to acknowledge that they almost missed it, and then you diligently stare into space desperately hoping no-one starts a conversation. Some lifts even mercifully include little screens displaying the weather and news headlines that offer everyone inside a sink for their collective attention.

This is a textbook example of what the Canadian sociologist Ervin Goffman called “civil inattention”. This is our tendency to actively not engage with those around us while not ignoring them entirely.

Civil inattention enables us to ensconce ourselves in a protective bubble of anonymity even while we’re shoulder-to-shoulder with other people. It’s both a defence mechanism that prevents us from having to constantly expend social energy interacting with every individual we encounter while also being a social lubricant that allows millions of strangers to coexist in relative peace.

The price of this unwritten social contract of non-engagement is loneliness. Indeed, it’s easier to feel isolated and disconnected from others in the middle of a bustling city than it is in a small town.

And with the growth of high density living over the last several decades so too has loneliness spread, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Loneliness was already prevalent prior to the advent social distancing and enforced lockdowns, but recent surveys have revealed a sharp increase, with over half of respondents reporting they have experienced loneliness during the pandemic.

Contrast the civilly inattentive world to the social world that our minds have evolved to expect. That is a world laced with rich social interaction, one where our very identities are interlaced with those around us. It’s a world that our ancestors dwelt in for thousands of generations, a world that shaped our minds, and one that only changed with the advent of high density living.

The anthropologist Lorna Marshall vividly described the intimate connectedness among one small-scale society, the Nyae Nyae !Kung people of the Kalahari desert.

“Their need to avoid loneliness, I think, is actually visible in the way families cluster together in their werfs and in the way people sit, often touching someone else, shoulder against shoulder, ankle across ankle. Comfort and security for them lie in belonging to their group, free from hostility or rejection,” she wrote.

This is the world where belonging is a given and it’s almost impossible to be alone. It’s the world that many modern folk seek out through social media, popular culture, the bustle of city life or even religion. These give the trappings of connectedness but they’re all ultimately based on illusion. What we yearn for is the opposite of loneliness: genuine connection.

The good news is that there are ways to build genuine connection. One way to do so is just by having better conversations.

You can think about Goffman’s civil inattention as being a mask of civility that we wear in public that presents the face that society expects us to have but also covers our deeper self. It’s a defence mechanism but it’s also a barrier to genuine connection.

We can see this in many of the conversations we have with friends and colleagues, where we’re expected to talk about how well we’re doing, about our successes and triumphs. This tendency is only amplified on social media, where we have even greater opportunity – and expectation – to curate a positive image or flex about our privilege (#blessed).

But to really connect with someone, we need to go beyond our respective masks to reach the whole person underneath, including their strengths and their vulnerabilities, their successes and their failures, their hopes as well as their fears. It’s in the mutual recognition that we’re all complex and flawed beings, often stumbling our way through life, that we can build genuine connection.

This doesn’t mean we should be opening up to strangers about our greatest blunders in a lift, but it does mean allowing ourselves to lower the mask a little at a time around friends, acknowledging some of our vulnerabilities and helping them to feel comfortable doing the same. It means asking questions about more than just what they did on the weekend or which footy team won or lost. It means asking how they felt about it, what they hope for, what they regret or what they learnt. And it means shutting up and really listening to them, withholding judgement and validating how they feel.

You might be surprised at how quickly a good conversation, one where you lower your mask even a little, can build a connection that is meaningful and lasting. Sharing a little of our deeper self and getting to know a little of others’ deeper selves can feel confronting, it can challenge societal norms of what polite conversations look like, but they are also one of the greatest – and easiest – antidotes to loneliness. I call it “uncivil attention”.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Steven Pinker

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There’s no good reason to keep women off the front lines

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 7 JUN 2022

From The Matrix to Euphoria, writer, philosopher and poet Joseph Earp has profiled some of the greatest philosophers, TV shows, films, music and pop culture moments to date, discussing what they can tell us about ourselves and the world.

Which is why we’re excited to share we’ve recently appointed Joseph as an Ethics Centre Fellow. Currently undertaking his PhD at The University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume, we sat down with Joseph for a brief get-to-know-you chat to discuss ethics, his favourite philosophers, and the role of pop culture in society.

Tell us, what attracted you to becoming a philosopher?

You learn the language of institutional philosophy by reading it, and – as long as your financial and geographical circumstances allow for it – by studying it in an academic setting. But the central questions that drive philosophical work are innate to almost all people, regardless of academic study.

I am a pragmatist, so I don’t believe that philosophers hold insight that stretches beyond the understanding of those who haven’t studied the discipline. As philosophers, we are merely using a certain vocabulary to ask our questions. I grew to love that vocabulary in my late twenties through university study, under the guidance of my honours and PhD supervisor, Anik Waldow and those academics I studied closely with throughout my undergraduate degree. Most notably, these academics include Caroline West, who I believe to be one of our country’s most unique, inspired, and challenging thinkers – even and especially as I disagree with her – and David Macarthur. My study with these people is what drew me to being a philosopher in the strictest sense. But I think we philosophers are, thankfully, just doing what everyone else is doing.

Do you specialise in any key areas?

Generally, I write about popular culture, emotion, and virtue ethics, but my key area of specialisation is the philosophy of sex. I think that we sadly retain, in many cultures, a suspicion and fear of sex – one that infringes on our ability to self-describe and live our most flourishing lives.

I often think of a story about Pablo Picasso. Towards the end of his life, he was so rich and famous that he could draw any object in the world, whether it be a Ferrari or a mansion, and his drawing would be worth more than the object itself. He could sell a sketch of an object, and use the accrued capital to buy that object – which is a way of saying he could create changes by charting what he felt had already changed. It seems to me that’s the potential, and the potential harm, of philosophical thinking. We construct the world by calling it what we think it is, and for a long time, our views on sexuality have created a world that contains a lot of fear and sexual repression, both internally and externally maintained.

Your honours thesis focuses on emotional contagion. What place does emotion have when it comes to ethics?

Personally, I think it’s emotion all the way down when it comes to ethics, as with most things. David Hume is the philosopher that much of my work has operated in the framework of, and I agree with Hume that when we talk about “rationality” – a word that is sometimes conceived as being opposed to emotion – we are really just talking about a certain kind of emotional work.

What have you been working on this year?

One of the most profound experiences of both my intellectual and personal life has been connecting with a community of thinkers whom I met largely through my university work – all of them world-class philosophers, some of them write for, and work with, the Ethics Centre; and some of them no longer consider themselves strictly philosophers at all. In particular, Georgia Fagan, Danielle Turnbull, Finola Laughren, Eleanor Gordon-Smith, Grace Sharkey, Oscar Sannen, Mitch Flitcroft, Alexi Barnstone, Elle Lewis, Mitchell Stirzaker, Henry Barlow, Zach Wilkinson, Finn Bryson, and Henry Hulme.

All of these people have work that you can, and should, find online through an easy Google search, and work which I believe in every case benefits the world, and drives real change. What else is philosophy for? I am continually astonished by the intellect and bravery of these collaborators and friends. I consider myself useless without them. When I think about the real work that I have done this year, it is not anything I have written, but conversations with these people, and the ways I have learnt from them.

Do you have a favourite philosopher or writer?

Hume is the philosopher whose writing I know best, but I believe the thinker you apply the greatest amount of study to is usually the one who you have the strangest, most frequently frustrated relationship with. So my favourite – as in, the philosopher who serves as the background to almost all of what I think and do, and who I have the most uncomplicated connection to – is the pragmatist Richard Rorty. It’s Rorty who cuts through the chaff by asking, again and again, one of the simplest questions: what is the real-world application of our work? And it’s Rorty who tells us that we should remember we can make ourselves whoever we want to be.

Your writing covers a lot of tv series, films and music. Why is pop culture important?

Again – it’s Rorty. Rorty believed that social change isn’t led by philosophers, particularly those analytic philosophers who consider their work to be sorting through “falsehoods” and “truths”. For Rorty, philosophers inspire prophets and poets, and prophets and poets are the ones who do the work of change. That is, for me, the importance of pop culture. That form of art is guided by philosophical questions, and led by prophets and poets, and represents a way of understanding a culture and a vocabulary. It’s how lives are changed, and possibilities for self-description are opened up

What are you reading, watching or listening to at the moment?

The poetry collection The Cipher, by Molly Brodak, a writer who means a great deal to me; the pornographic film Corruption by perennial sadsack and visionary Roger Watkins, which I try to return to every month or so; and the song ‘Lark’ by Angel Olsen, often enough that I should probably take a break.

Let’s finish up close to home. What does ethics mean to you?

We all play the game of ethics, and we all want to play it better, and we’ll never play it well. That, in fact, is the joy – the trying, and the starting again.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

11 books, films and series on the ethics of wealth and power

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

You won't be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 2 JUN 2022

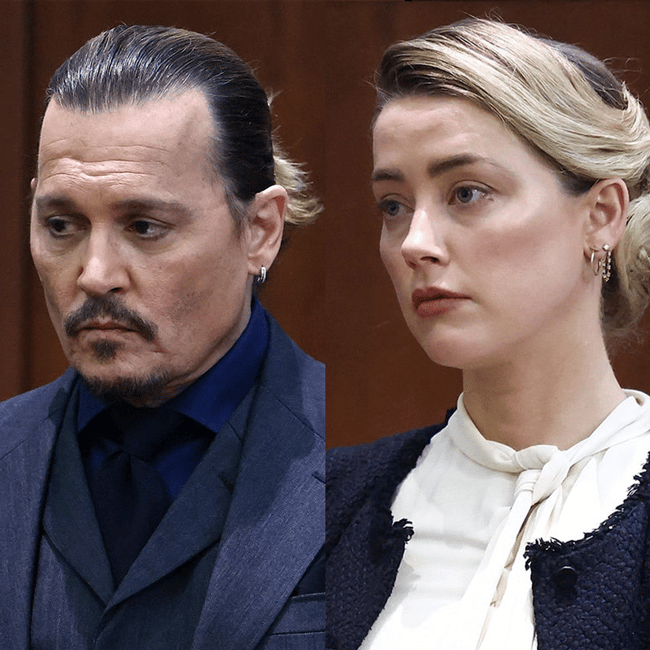

The Johnny Depp and Amber Heard defamation trial is now over.

Heard has been found guilty of defaming the actor with an op-ed she wrote – that did not name him explicitly – about being a survivor of domestic violence. Depp’s legal team too has been found guilty of defamation, but the amount that Heard has to now pay Depp is a much higher figure than he has to pay her.

The proceedings are done. But the media reaction to the trial – both from traditional outlets, and the deluge of posts about it crowding every single social platform like ants across an old plate of food – will linger.

This is because, in many circles, the all-too public spectacle has been treated like an unprecedented event. Pored over ad nauseum, it has been subject to endless thinkpieces, YouTube breakdowns, and Twitch streams. Twitter is awash with “fan edits”, compilations of carefully selected moments cut to the jaunty music usually associated with dance trends, or videos of dogs playing with each other in suburban backyards. There’s no use blocking keywords associated with it on social media. Videos still find a way to slip through, because the trial is everywhere.

This isn’t so surprising. The trial is on one level, a glimpse into the personal lives of the usually alien upper class. On another, it is shocking and disturbing enough – whichever side one takes – that it provides the vicious thrills that a culture which has become obsessed with true crime obsessively seeks out. This is all information, content. But how much of it do we need to make an informed decision about the outcome of the trial? And more than that, is this a useful kind of information? Where does it lead us? What does it give us?

The trial is foreign, it’s taboo, it’s ugly, and it’s glossy. What it isn’t, however, is quite as novel as it first seems.

Old Stories; New Faces

Much like the O.J. Simpson trial, or the proceedings against Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton, the Australian woman who claimed a dingo ate her baby, the Depp/Heard case is an example of a media-captivated society channeling abstract arguments through the lens of a high stakes legal proceeding, populated by faces that viewers have already developed complex parasocial relationships with. And, importantly, in each case, there has been an intense public scrutiny on how the figures in these cases should act – a fixation on their body language, their expressions, and the way they sound out words.

During the Simpson trial, the abstract arguments at play concerned race relations. Now, the tensions underlying the Depp/Heard trial are to do with what is sometimes referred to as our “post-metoo world”, a culture that has seen abusers reckoned with, and vast systems of deception that protect those abusers brought to light.

All of these court cases represented, and now represent, an opportunity for the public at large to discuss topics they might not normally have considered polite to bring up at the dinner table, or around the water cooler. “Is O.J. guilty?” was a way of saying, “tell me what you think about race and class in this country.” “Is Amber Heard a liar?” is now a way of saying, “what do you think abuse looks like? And what do we do about it?”

But there is at least one way that the Depp/Heard trial is involved with a trend that is breaking new ground. Unlike the Simpson trial, or the case against Chamberlain-Creighton, most viewers are watching the case through the internet. In turn, that means viewers have a unique ability to craft their own content about the proceedings, filtering key moments pulled from hours of footage through whatever pre-existing narrative they have constructed about the hero and the villain of this painful, and very sad story.

These content creators, who are often cutting together their videos in their spare time for no gain except rallying their audience around them, can watch over the trial’s footage as frequently as they like. They can scrutinize the same few seconds over and over; slow stretches of it down; freeze them in place.

In turn, that has turned a growing number of these amateur video essayists into amateur psychologists. A large subset of Depp/Heard content creators have come to believe that they can work out which of the players are lying by closely watching their expressions, unpacking their body language, and picking over the slightest tic, or absent gaze. For these sleuths, the case’s conclusion is as clear as Heard’s grimace, or the smile unfurling in the corner of Depp’s lips.

The Face Of A Liar

Those who seek to excavate the “truth” hiding beneath the trial by studying the body language and facial expressions of Depp and Heard start from a justifiable philosophical position. It was the philosopher Baruch Spinoza, a famous monist, who believed that every bodily state is underwritten by a mental state. For Spinoza, all things are of the one matter – variously called “nature”, or “God” by his intellectual interpreters. On this view, there is no distinction between any two substances, let alone a distinction between the way we hold ourselves, and what we think. The mind is the body, and the body is the mind.

From this starting point, it makes some sense to believe that the flesh might hold some insight into the secret thoughts and desires of two people who are very famous and very rich – and thus largely inaccessible, because nothing buys privacy like money and influence. Or, if not insight, then evidence gathered as post-hoc justification. Decisions as to guilt change based on a variety of factors – but they’re sometimes made early, and data can be gathered after those decisions have already been made, propping up pre-existing positions.

The mistake, however, is to generalise what these embodied states look like, and thus to generalise the emotional and mental states they are tied to.

There is, quite simply, no one way that all of us look when we lie, or are distressed, or happy. We are distinct in the way that we consider the world around us, and thus distinct in the way that we physically appear when we do.

Many of the “tell-tale signs” that get neurotically returned to, over and over again, on social media – Heard’s tone of voice, Depp’s drawl – could have any number of associated affective states, from anxiety, to pain, to yes, perhaps, the desire to lie. “It can be tough to accurately interpret someone through their body language since someone may feel tense or look uneasy for so many reasons,” said the therapist and author Dr. Jenny Taitz.

If we follow Spinoza, we will believe that our bodies and our thoughts are intertwined – but that’s not the same as saying the former will reveal the latter. These are slabs of affect, expressed both physically and mentally, but they are not as easily comprehensible as that makes them sound.

Indeed, psychological studies have proved for decades that none of us are skilled when it comes to weeding out those spinning “falsehoods”, and those not. A 2004 study of lying found that “agents of the FBI, the CIA and the National Security Agency – as well as judges, local police, federal polygraph operators, psychiatrists and laymen – performed no better at detecting lies than if they had guessed randomly.”

There is, after all, an immense social advantage to picking liars. If we could do it, and do it reliably, then that would be an invaluable skill, one we would expect to spread and be adopted across communities quickly. The fact that there is no dominant method of analysing the way our bodies twist and pose when speaking in itself speaks to the impossibility of using faces to get at what we mean when we talk about “the truth.”

Moreover, even most “body language experts” – an increasingly popular and media-saturated sub-set of pop psychologists, who have almost no science to back up their claims – admit that we need to get a baseline of our subject’s physical reactions before we can even attempt the fraught and mostly doomed work of trying to understand if they’re lying.

Which is to say, we need to at least know what people look like when they’re telling the truth before we can tell if they’re not. And we don’t know Johnny Depp, or Amber Heard, despite the illusion of closeness granted by social media. We don’t have enough data about how they move through the world, or what they look like when they do. How could we possibly guess at the motives and thoughts of utter strangers?

The Actors

Heard’s critics in particular have developed the line that she is a “performer”, going through the mere motions of grief and trauma – and not particularly well. They highlight a moment in which Heard appeared to pause while waiting for a cameraperson to snap a picture of her pained face, and another in which she seemed to flicker, composing herself for her next line as an actress on set would.

Of course, Heard is performing, on some level. But she is not performing in a way different to Depp. Though his defenders do not often note it, he too is signaling to the cameras, and to the jury – his smiles, and asides to his legal team, make that clear.

Nor, even, are these two distinct from the rest of us. We are all performing. We are social creatures, who have the ability to tell when we are being watched by others. Theory of mind, the term used to describe our understanding that other human beings see and think like we do, means that we can throw ourselves into the perspective of our observers. We do this constantly. It is part of what it means to have a body, and to be a person.

As philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre pointed out, we don’t even have to be actively watched to know that we could be watched. We carry with us the sense that we are what Sartre called a “thing in the world” – an entity that, at any time, could be stumbled across, and studied. As a result, we are always aware of ourselves, and how we might appear. Even when we are totally alone, we are never really alone. We are always with others – whether they’re flesh and blood observers, or ones we’ve made up in our head.

Where The Truth Lies

None of this has been an attempt to argue that Depp is telling the truth over Heard, or vice versa. It is not even a question of “truth”, as that word has been contemporaneously used.

The binary between the “real” and the “fake”, aggressively emphasised in media reactions to the trial, is itself overly simplistic, an outdated harbinger dangerously trickled down into the culture by analytic philosophy.

That is not to diminish the hurt, or the trauma, that clearly sits at the centre of the trial. That pain is real. That pain can be understood, but only when we look at the evidence in totality – the actual evidence, not the faces on the stand – and then causally tie it to certain parties.

We should, however, remember there is no objective state of affairs – no perfect place from which, like God, we can dispel the lies and embrace the world as it really is. The judge overseeing the Depp/Heard trial is not neutral. None of us are. At best, in this case as in so many others, we should, like the great pragmatist Richard Rorty, argue for ethnocentric justification for our claims, rather than tying them to a standpoint that sits outside of history, and belief, and bias. In doing so, we can embrace the changeability of our own positions – not on guilt and innocence, exactly, but the societal pressures that are so at play here – and examine them, seeing them as the flexible systems of thought that they are.

Throughout, however, we should remember that whatever we’re looking for when we hope to untangle a messy and painful relationship between two strangers who we will almost certainly never meet, it will not be found in their faces.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology