‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 18 MAR 2016

Warning – general plot spoilers to follow.

Collateral damage

Eye in the Sky begins as a joint British and US surveillance operation against known terrorists in Nairobi. During the operation, it becomes clear a terrorist attack is imminent, so the goals shift from surveillance to seek and destroy.

Moments before firing on the compound, drone pilots Steve Watts (Aaron Paul) and Carrie Gershon (Phoebe Fox) see a young girl setting up a bread stand near the target. Is her life acceptable collateral damage if her death saves many more people?

In military ethics, the question of collateral damage is a central point of discussion. The principle of ‘non-combatant immunity’ requires no civilian be intentionally targeted, but it doesn’t follow from this that all civilian casualties are unethical.

Most scholars and some Eye in the Sky characters, such as Colonel Katherine Powell (Helen Mirren), accept even foreseeable casualties can be justified under certain conditions – for instance, if the attack is necessary, the military benefits outweigh the negative side effects and all reasonable measures have been taken to avoid civilian casualties.

Risk-free warfare

The military and ethical advantages of drone strikes are obvious. By operating remotely, we prevent the risk of our military men and women being physically harmed. Drone strikes are also becoming increasingly precise and surveillance resources mean collateral damage can be minimised.

However, the damage radius of a missile strike drastically exceeds most infantry weapons – meaning the tools used by drones are often less discriminate than soldiers on the ground carrying rifles. If collateral damage is only justified when reasonable measures have been taken to reduce the risk to civilians, is drone warfare morally justified, or does it simply shift the risk away from our war fighters to the civilian population? The key question here is what counts as a reasonable measure – how much are we permitted to reduce the risk to our own troops?

Eye in the Sky forces us to confront the ethical complexity of war.

Reducing risk can also have consequences for the morale of soldiers. Christian Enemark, for example, suggests that drone warfare marks “the end of courage”. He wonders in what sense we can call drone pilots ‘warriors’ at all.

The risk-free nature of a drone strike means that he or she requires none of the courage that for millennia has distinguished the warrior from all other kinds of killers.

How then should drone operators be regarded? Are these grounded aviators merely technicians of death, at best deserving only admiration for their competent application of technical skills? If not, by what measure can they be reasonably compared to warriors?

Moral costs of killing

Throughout the film, military commanders Catherine Powell and Frank Benson (Alan Rickman) make a compelling consequentialist argument for killing the terrorists despite the fact it will kill the innocent girl. The suicide bombers, if allowed to escape, are likely to kill dozens of innocent people. If the cost of stopping them is one life, the ‘moral maths’ seems to check out.

Ultimately it is the pilot, Steve Watts, who has to take the shot. If he fires, it is by his hand a girl will die. This knowledge carries a serious ethical and psychological toll, even if he thinks it was the right thing to do.

There is evidence suggesting drone pilots suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other forms of trauma at the same rates as pilots of manned aircraft. This can arise even if they haven’t killed any civilians. Drone pilots not only kill their targets, they observe them for weeks beforehand, coming to know their targets’ habits, families and communities. This means they humanise their targets in a way many manned pilots do not – and this too has psychological implications.

Who is responsible?

Modern military ethics insist all warriors have a moral obligation to refuse illegal or unethical orders. This sits in contrast to older approaches, by which soldiers had an absolute duty to obey. St Augustine, an early writer on the ethics of war, called soldiers “swords in the hand” of their commanders.

In a sense, drone pilots are treated in the same way. In Eye in the Sky, a huge number of senior decision-makers debate whether or not to take the shot. However, as Powell laments, “no one wants to take responsibility for pulling the trigger”. Who is responsible? The pilot who has to press the button? The highest authority in the ‘kill chain’? Or the terrorists for putting everyone in this position to begin with?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Power without restraint: juvenile justice in the Northern Territory

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 15 MAR 2016

The naturalistic fallacy is an informal logical fallacy which argues that if something is ‘natural’ it must be good. It is closely related to the is/ought fallacy – when someone tries to infer what ‘ought’ to be done from what ‘is’.

The is/ought fallacy is when statements of fact (or ‘is’) jump to statements of value (or ‘ought’), without explanation. First discussed by Scottish philosopher, David Hume, he observed a range of different arguments where writers would be using the terms ‘is’ and ‘is not’ and suddenly, start saying ‘ought’ and ‘ought not’.

For Hume, it was inconceivable that philosophers could jump from ‘is’ to ‘ought’ without showing how the two concepts were connected. What were their justifications?

If this seems weird, consider the following example where someone might say:

- It is true that smoking is harmful to your health.

- Therefore, you ought not to smoke.

The claim that you ‘ought’ not to smoke is not just saying it would be unhealthy for you to smoke. It says it would be unethical. Why? Lots of ‘unhealthy’ things are perfectly ethical. The assumption that facts lead us directly to value claims is what makes the is/ought argument a fallacy.

As it is, the argument above is unsound – much more is needed. Hume thought no matter what you add to the argument, it would be impossible to make the leap from ‘is’ to ‘ought’ because ‘is’ is based on evidence (facts) and ‘ought’ is always a matter of reason (at best) and opinion or prejudice (at worst).

Later, another philosopher named G.E. Moore coined the term naturalistic fallacy. He said arguments that used nature, or natural terms like ‘pleasant’, ‘satisfying’ or ‘healthy’ to make ethical claims, were unsound.

The naturalistic fallacy looks like this:

- Breastfeeding is the natural way to feed children.

- Therefore, mothers ought to breastfeed their children and ought not to use baby formula (because it is unnatural).

This is a fallacy. We act against nature all the time – with vaccinations, electricity, medicine – many of which are ethical. Lots of things that are natural are good, but not all unnatural things are unethical. This is what the naturalistic fallacy argues.

Philosophers still debate this issue. For example, G. E. Moore believed in moral realism – that some things are objectively ‘good’ or ‘bad’, ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. This suggests there might be ‘ethical facts’ from which we can make value claims and which are different from ordinary facts. But that’s a whole new topic of discussion.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Should I have children? Here’s what the philosophers say

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is existentialism due for a comeback?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Plato

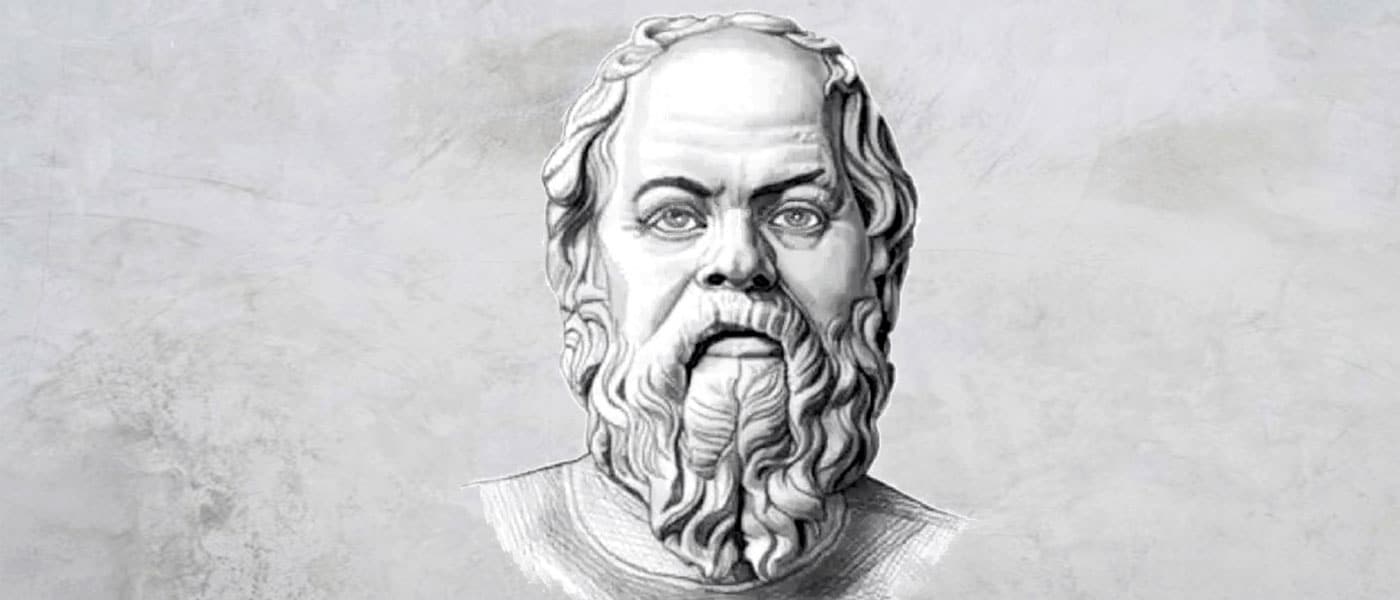

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Socrates

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Jane Hunt The Ethics Centre 14 MAR 2016

During the last year, I have listened and talked with practitioners, policy makers, adoptees, adoptive parents, children and young people in care, and birth families.

I have heard of the best and worst of human beings. My heart has constricted hearing about the profound harm some have experienced, and it has swelled in joy at the love that human beings can have for each other.

Research shows unequivocally that multiple placements have a negative impact on children.

Adoption in Australia has become fraught in all aspects – politics, policy and practice. It is a complex social issue that presents ethical and moral dilemmas for Government, the NGOs working with vulnerable and at-risk children, and for the broader community. It is complex and nuanced, with no clear response that will work in all cases. And it is highly emotionally charged.

In Australia, there are more than 43,000 children in ‘out of home care’. These children are identified as being ‘at risk’ and cannot remain in the care of their biological parents. They have been removed by child protection practitioners and, depending on the child’s circumstances, have been placed in the care of extended family, or with a guardian, or in short-term foster care.

Once children have been removed, the efforts of the child protection workers and other support services are framed to support the birth parents and to help them to reunify with their children. And this is where one of many ethical dilemmas emerges for the practitioners, policy makers and legislators.

How many opportunities should biological parents be given to demonstrate they are able keep their children safe and parent them? What level of support and services should they receive? And in the meantime, how long should a child stay in temporary care? How many placements is it tolerable for a child to experience?

These are difficult decisions for practitioners to make – each child’s situation is different. One practitioner described weighing up whether to return a child to their birth family against the risk of harm to the child as one of his hardest challenges. Having worked overseas, he believed that in Australia, the scales have tipped toward ‘restoration’ with birth families at all costs. This is not appropriately counter-balanced with an assessment of the risk of harm to children in the process.

Adoption in Australia has become fraught in all aspects – politics, policy and practice.

Compounding the situation is the problem of the availability and quality of foster carers able to care for vulnerable children. One practitioner in a regional town told me of a situation where she had to make a decision not to remove a child from a harmful situation because they did not have an appropriate foster carer available. The fact the child remained in an abusive family environment weighed heavily on the practitioner’s conscience.

Adoption, child protection and out of home care policy and legislation are founded on the assumption that decisions must be made in the ‘best interests of the child’. There is, however, no universally agreed upon definition of what this means.

Foster care is, by nature, temporary. There is always the possibility for the child that their relationship with their carers will end. This means some children experience multiple placements in foster care.

Sometimes the reasons for a change of placement are compelling – to be nearer their school, with siblings or nearer extended family members. However, research shows unequivocally that multiple placements have a negative impact on children.

Lack of security and attachment can have profound impacts on development. I’ve been told that multiple moves teach children that adults ‘come and go’ and cannot be trusted – a view corroborated by some young people in foster care who report feeling they ‘don’t belong’ anywhere.

Even the ‘Permanent Care Orders’ preferred in Victoria, which enable a child to live with a family until they are 18, fall short of providing a child or young person with the psychological and legal security of a family forever.

Why in Australia do we continue to provide a system that fails to meet children’s long term needs?

At the heart of this discussion lies a paralysing ethical dilemma – when a decision needs to be made to remove a child from their biological parents due to harm, neglect or abuse or when it’s not been successful, whose rights should be protected?

The right of the parent to keep their children, or the rights of the children to the conditions that will help them feel safe, secure and loved? Whose pain takes precedence? The parents’ loss and grief or the child’s trauma and pain?

The trauma caused by the historical practices of forced and closed adoptions has made many practitioners and politicians highly attuned to the needs of birth families. We need to learn from the profound hurt and trauma inflicted on many women who were coerced into relinquishing their children.

Adoption is not a panacea – it won’t be in the best interest of every child in long-term care.

The voices of adult adoptees who experienced secrecy, stigma and shame around their adoptions are deserving of understanding and compassion.

But considering or advocating for children to have access to adoption does not deny or ignore these experiences. It is important to learn from the impact of past practices and develop open adoption practices ensuring transparency and honesty for all involved, and provide support services that assist all parties involved in adoption.

It is also important to recognise that attempting to deal with an historical wrong – forced adoption – by loading the policy scales against adoption, creates a situation where everyone loses.

Adoption is not a panacea – it won’t be in the best interest of every child in long-term care, but it should be an option considered for all children that need permanent loving families. This then allows a decision to be made that is child focused and in their best interest.

There are many policy makers, practitioners, legislators, and families trying to acknowledge and navigate the ethical complexities of child protection, foster care and adoption. It is critical we continue in this direction, without being subsumed by the shame of our cultural past, to put the needs of vulnerable and at risk children first.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Can beggars be choosers?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Narcissists aren’t born, they’re made

Reports

Politics + Human Rights

The Cloven Giant: Reclaiming Intrinsic Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Brian Draper The Ethics Centre 9 MAR 2016

“This is a worldwide phenomenon in which men die at four times the rate of women. The four to one ratio gets closer to six or seven to one as people get older.”

That’s Professor Brian Draper, describing one of the most common causes of death among men: Suicide.

Suicide is the cause of death with the highest gender disparity in Australia – an experience replicated in most places around the world, according to Draper.

So what is going on? Draper is keen to avoid debased speculation – there are a lot of theories but not much we can say with certainty. “We can describe it, but we can’t understand it,” he says. One thing that seems clear to Draper is it’s not a coincidence so many more men die by suicide than women.

If you are raised by damaged parents, it could be damaging to you.

“It comes back to masculinity – it seems to be something about being male,” he says.

“I think every country has its own way of expressing masculinity. In the Australian context not talking about feelings and emotions, not connecting with intimate partners are factors…”

The issue of social connection is also thought to be connected in some way. “There is broad reluctance by many men to connect emotionally or build relationships outside their intimate partners – women have several intimate relationships, men have a handful at most,” Draper says.

You hear this reflection fairly often. Peter Munro’s feature in the most recent edition of Good Weekend on suicide deaths among trade workers tells a similar story.

Mark, an interviewee, describes writing a suicide note and feeling completely alone until a Facebook conversation with his girlfriend “took the weight of his shoulders”. What would have happened if Mark had lost Alex? Did he have anyone else?

None of this, Draper cautions, means we can reduce the problem to idiosyncrasies of Aussie masculinity – toughness, ‘sucking it up’, alcohol… It’s a global issue.

“I’m a strong believer in looking at things globally and not in isolation. Every country will do it differently, but you’ll see these issues in the way men interact – I think it’s more about masculinity and the way men interact.”

Another piece of the puzzle might – Draper suggests – be early childhood. If your parents have suffered severe trauma, it’s likely to have an effect.

“If you are raised by damaged parents, it could be damaging to you. Children of survivors of concentration camps, horrendous experiences like the killing fields in Cambodia or in Australia the Stolen Generations…”

It comes back to masculinity – it seems to be something about being male.

There is research backing this up. For instance, between 1988 and 1996 the children of Vietnam War veterans died by suicide at over three times the national average.

Draper is careful not to overstate it – there’s still so much we don’t know, but he does believe there’s something to early childhood experiences. “Sexual abuse in childhood still conveys suicide risk in your 70s and 80s … but there’s also emotional trauma from living with a person who’s not coping with their own demons.”

“I’m not sure we fully understand these processes.” The amount we still need to understand is becoming a theme.

What we don’t know is a source of optimism for Draper. “We’ve talked a lot about factors that might increase your risk but there’s a reverse side to that story.”

“A lot of our research is focussed predominantly on risk rather than protection. We don’t look at why things have changed for the better … For example, there’s been a massive reduction in suicides in men between 45-70 in the last 50 years.”

“Understanding what’s happened in those age groups would help.”

It’s pretty clear we need to keep talking – researchers, family, friends, support workers and those in need of support can’t act on what they don’t know.

If you or someone you know needs support, contact:

-

Lifeline 13 11 14

-

Men’s Line 1300 78 99 78

-

beyondblue 1300 224 636

-

Kids Helpline 1800 551 800

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to help your kid flex their ethical muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

BY Brian Draper

Professor Brian Draper is Senior Old Age Psychiatrist in the South East Sydney Local Health Network and Conjoint Professor in the School of Psychiatry at UNSW.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

ExplainerHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAR 2016

A logical fallacy occurs when an argument contains flawed reasoning. These arguments cannot be relied on to make truth claims. There are two general kinds of logical fallacies: formal and informal.

First off, let’s define some terms.

- Argument: a group of statements made up of one or more premises and one conclusion.

- Premise: a statement that provides reason or support for the conclusion

- Truth: a property of statements, i.e. that they are the case

- Validity: a property of arguments, i.e. that they are logically structured

- Soundness: a property of statements and arguments, i.e. that they are valid and true

- Conclusion: the final statement in an argument that indicates the idea the arguer is trying to prove

Formal logical fallacies

These are arguments with true premises, but a flaw in its logical structure. Here’s an example:

- Premise 1: In summer, the weather is hot.

- Premise 2: The weather is hot.

- Conclusion: Therefore, it is summer.

Even though statement 1 and 2 are true, the argument goes in circles. By using an effect to determine a cause, the argument becomes invalid. Therefore, statement 3 (the conclusion) can’t be trusted.

Informal logical fallacies

These are arguments with false premises. They are based on claims that are not even true. Even if the logical structure is valid, it becomes unsound. For example:

- Premise 1: All men have hairy beards.

- Premise 2: Tim is a man.

- Conclusion: Therefore, Tim has a hairy beard.

Statement 1 is false – there are plenty of men without hairy beards. Statement 2 is true. Though the logical structure is valid (it doesn’t go in circles), the argument is still unsound. The conclusion is false.

A famous example of an argument that is both valid, true, and sound is as follows.

- Premise 1: All men are mortal.

- Premise 2: Socrates is a man.

- Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

It’s important to look out for logical fallacies in the arguments people make. Bad arguments can lead to true conclusions, but there is no reason for us to trust the argument that got us to the conclusion. We might have missed something or it might not always be the case.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Democracy is hidden in the data

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to deal with an ethical crisis

How to deal with an ethical crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 8 MAR 2016

The recent dissection of CommInsure’s heartless treatment of some of its policy holders (including fellow employees) by Fairfax Media and ABC’s 4 Corners program reinforced every bad stereotype there is about the world of banking and finance.

The people whose stories were featured in the reports were treated in a manner that made me wince. You’d think that people of even moderate decency would have realised that what was being done was wrong. Yet the evidence is incontrovertible.

Basic decency was set aside in favour of the financial interests of the corporation and, one suspects, the people making the decisions. Until now, the cost of this has been borne by those whose claims were denied.

Now the price is being paid by the Commonwealth Bank and the vast majority of innocent employees who will have been appalled and ashamed by what has been revealed.

Now that the issues have been exposed, the first order of business should be to remedy the harms that were caused to individuals who had a right to expect that their legitimate interests would not be sacrificed for commercial gain.

The particular vulnerabilities of those affected make for especially chilling stories. No person, whatever their circumstances, should have the careful parsing of the language of insurance policies turned against them. We all buy insurance in the expectation that it will be available when we really need it. It is just plain ‘tricky’ when loopholes are used to deny our reasonable expectations.

It is time that we developed a more mature understanding of what it means to live an ethical life as an individual or as an organisation.

The second order of business must be to rescue the concept of ‘ethics’ in banking and finance. In recent months, I have spoken to a number of senior leaders in the banking and finance industry about their signing the Banking + Finance Oath. As things stand, about 600 people have made a personal commitment to the tenets of the Oath. Every person with whom I have spoken supports what the Oath says and stands for.

However, quite a few are reluctant to sign for fear that something might go wrong – and that in the face of evidence of ‘ethical failure’ they will be accused of hypocrisy.

Their misgivings are understandable – especially after the CommInsure scandal. It was only at the CBA’s last AGM that the Chairman and CEO both raised the issue of ethics – making a commitment to become an “ethical bank“. At the time, cynics scoffed at the idea. In recent days, and quite predictably, the CBA has been ‘hit over the head’ (clobbered is probably the better word) with this aspiration. No wonder people are nervous about making a public commitment to ethics!

The Ethics Centre worked extensively with the CBA in late 2014 and early 2015 (but not with CommInsure) and I have a high regard for the sincerity with which they laid out a path for ethical development at the 2015 AGM. What was said then should not be dismissed out of hand – and especially not because of recent events. Rather, we should ensure that the standard by which we assess the CBA is a reasonable one – and then judge accordingly.

To think that any individual (other than a saint) can achieve ethical perfection is unfair and unrealistic. I certainly wouldn’t measure up to that standard. To think that an organisation of 50,000 people will be perfect is just ridiculous. What we can (and should) expect is that an ethical organisation will distinguish itself with a number of key features.

First, it will actively seek to reinforce the application of its values and principles – not just at the rhetorical level but as part of an ongoing program to root out and eliminate all systems, policies and structures that might subtly (and not so subtly) lead people to act in a manner that is unethical.

Second, it will build a culture of open communications in which people are rewarded (and certainly not punished) for drawing attention to practices that appear to be inconsistent with the organisation’s declared ethical framework.

Third, an ethical organisation will be marked by the quality and character of its response to ethical failure. For example, it will own up to its own failings. It will remediate and compensate for any harms done. It will ensure that the lessons to be learned are widely published for the benefit of others. It will aim to do what is right – and not just the minimum that it is required to do.

This third aspect was evident in Ian Narev’s response to questioning on Four Corners. I believe his expressions of concern were sincere and that he will follow up, personally, with the affected individuals. Beyond this, I have no doubt (but no certain knowledge) that he is leading a process that will meet the expectations outlined above. That CBA follows this path will be a surer indication of its commitment to ethics than the fact that this shameful series of events occured in the first place. And that is what we need to evaluate.

An ethical organisation will be marked by the quality and character of its response to ethical failure.

It is time that we, in society, developed a more mature understanding of what it means to live an ethical life as an individual or as an organisation. If we cannot be perfect, then we can at least be held to account for the sincerity with which we make our best efforts to act, in good conscience, in conformance with our chosen values and principles.

And second, we should be accountable for the competence we bring to bear in our ethical decision-making – it’s a skill that cannot be taken for granted and needs development through active, reflective practice.

If this (rather than perfection) was the standard we insisted on – for ourselves and others – then more people in the world of banking and finance might publicly commit to what they know, in their heart-of-hearts, to be right and good.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Shadow values: What really lies beneath?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Our regulators are set up to fail by design

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Service for sale: Why privatising public services doesn’t work

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Shannon Kennedy The Ethics Centre 4 MAR 2016

On his interest in ‘Mankind – Deconstructing Masculinity’:

Masculinity is something I’ve been thinking about a bit lately. I’ve been raising my boy for the past year and a half and having your first kid makes you wonder about the things you’ve learned and the things you want to pass on.

There are a lot of things I learned that I don’t want to pass on, and even more stuff I never really considered before I became a dad – things I don’t have the answers for.

On being a full-time dad:

I’ve had to come to grips with the challenges of being a stay-at-home dad.

Support and network groups are almost entirely set up for mums. Our entire parenting language is set up around mums. We have ‘mothers’ groups’ or in my case ‘mums’ surfers groups’ so someone could watch my son while I went for a surf. I felt really excluded from a lot of these activities.

It’s the hardest work I’ve ever done but it’s still not considered a man’s work.

There’s a patronising assumption about men in parenting roles. My boy had a meltdown at swimming the other day and other parents looked at me as though I wasn’t used to it. They said things like “Oh, you’re doing so well”, and I thought “Thanks, I’ve been doing this full time for a year and a half”. It felt pretty patronising.

Like a lot of men, I defined myself by my work, which has taken a back seat lately. I’ve been dealing with the shifting definitions of my own identity. It’s weird, because it’s the hardest work I’ve ever done but it’s still not considered a man’s work.

On the pressure fathers face to teach their sons ‘what it means to be a man’:

I think it’s probably the same for most men. I’m assuming it was for my dad – he didn’t have those answers for me when I was growing up. A lot of it gets left to outside sources to inform you.

I didn’t really take much of that on board. I just tried to keep my head down at school and get out of there. The way the school approached masculinity was completely at odds with the way my parents were trying to raise me and my brothers.

I’ve only recently realised the influence of all this. In a few years’ time my son is going to get picked on, get into fights, and ask me the same kind of questions.

On his journey toward hip hop:

The school I went to was very sort of ‘jock’, and I wasn’t like that at all. My journey into hip hop was a way of dealing with that and overcoming the trauma. It was a defensive mechanism – my parents didn’t instil this in me – but you do need to fight in one way or another. Words became my weapons. It’s only recently that I’ve realised that was a big influence in leading me into hip hop.

On masculinity and sexism in Australian hip hop:

Like a lot of the music industry, hip hop has been male dominated, although it hasn’t been part of my experience – aside from a few years of battle rapping, which was part of my journey to establish some boundaries. Battling was a way to make up for my time at school and I wish I’d been able to use those skills to create space around me.

There is a lot of very macho and sexist culture around hip hop music, but I don’t think it’s exclusively that way, and I think it’s been changing, in lots of ways, The Herd was a challenge to that whole notion of hip hop.

On The Herd’s re-imagination of Redgum’s ‘I Was Only 19’:

War is an extension of those more negative aspects of masculinity. It’s almost the biggest manifestation of them. There was a lot of anger around the Vietnam War – seeing these patterns repeated. I think the original is quite angry in its own folksy way.

I know from hanging out with John Schumann that the people he was writing about, and writing for, were certainly angry about the way they’d been treated.

War is an extension of those negative aspects of masculinity.

On veterans:

There’s a notion, especially in Australia – it probably comes from the Anglo tradition – that you should just “suck it up and get on with it”. I think it’s one of the most damaging parts of male identity in this country and a big contribution to high youth suicide rates, drug abuse and mental health issues.

There have been big campaigns to move that along, but generally men are still supposed to cop it on the chin and move on. I think that’s a major issue for a lot of returned soldiers and other men. It’s still considered fairly awkward to delve into your feelings with other men.

On radicalisation and alcohol violence among young people:

It’s all part of the same thing. I think a lot of kids involved with radical organisations are pretty stupid, but kids tend to be.

You do need to fight in one way or another. For me, words became my weapons.

These kids are caught between two worlds. Being a young male, I think feeling anger, learning to deal with it, and finding an outlet for it is really important. Anger does express itself in different ways, but not having a culture where it’s acceptable to show anger non-physically leads to a number of issues.

Combine all this with the fact that the one space where it is acceptable to be emotional is when you’re pissed, and it’s not surprising to see the problems we do.

For me, hip hop – when I was a teenager – was my angry refuge. The sort of stuff I listened to when I was a teenager isn’t stuff I listen to these days. The music is still nostalgic, but kind of embarrassing. It’s the stuff that attracts young men though. It resonates with something inside them or gives them a bit of an outlet.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Values

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The morals, aesthetics and ethics of art

The morals, aesthetics and ethics of art

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio The Ethics Centre 25 FEB 2016

People love a good story. As Aristotle said, we are story-telling animals. By engaging with stories we can consider different points of view and empathise with others – including fictional characters.

Stories let us reflect on how we would feel or act if we were in the shoes of another. They might even help us be more compassionate in real life.

Truth and Story-telling

True stories are among the narratives that grab our attention. Reality TV has become a phenomenon, while dramatic portrayals of the lives of famous people, and retelling real life events are increasingly popular. Perhaps the it’s driven by our desire to better understand human nature.

But how real are these representations? The idea of reality TV as scripted surely doesn’t surprise many viewers, but what about biopics like The Wolf of Wall Street, Spotlight or The Big Short?

Overt ethical messages in such movies are made all the more powerful if the audience sees these films as factual.

Any film based on reality will have a tough job conveying a person’s life or a series of events that unfolded over a number of years into a 120-minute linear narrative. There are important decisions to be made such as what to include or exclude, and from which perspective to tell the tale. Then there is the element of ‘moralising’ – sending a ‘take home message’ to the audience.

Overt ethical messages in such movies are made all the more powerful if the audience sees these films as factual. So does that mean filmmakers are obliged to be truthful in biopics, or are they only bound by what makes a good story?

Aestheticism – art for art’s sake

There is a strong historical precedent for separating the moral from the aesthetic value of artworks. Oscar Wilde’s famous quote from the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray states, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.”

This sums up a philosophical position known as ‘Aestheticism’, which argues that the only relevant factor when judging the quality of an artwork is its aesthetic value. Wilde explicitly categorises himself as an ‘Aestheticist’, yet he is well-known as a moralist. What’s going on here?

The reason people watch films or read is primarily for enjoyment – to tap into this so-called aesthetic experience. This involves enjoying the beauty or creativity of an artwork for its own sake. Aesthetic value is unique to artworks, so Aestheticists claim this should be the sole basis for aesthetic judgement. Any moral message in the work should not, therefore, affect the overall value of the artwork, either positively or negatively.

Aestheticists like Wilde may also want to protect art from censorship. If an artwork is judged only on the basis of its aesthetic qualities, it should not be condemned for its moral message. This concern harks all the way back to Ancient Greece when Plato was worrying in The Republic that the poets might corrupt the youth.

Moralism – the message behind the masterpiece

Artists are often well placed to critically engage with moral themes. Wilde’s novels and plays satirised the social norms of his day, and the best way he could protect his artistic right to free speech was to claim that the only thing one should judge is an artwork’s aesthetic merit.

However, to take this further and say artists are not concerned with moral, economic or political concerns is, I believe, mistaken. Of course artists need to consider real world concerns. Partly because they need to make a living and survive in the world in order to continue making their art.

Society also needs artists to help explore diverse perspectives. Artworks can be informative, influential and possibly even transform social attitudes about certain issues. However, sometimes the moral and aesthetic judgements of an artwork will clash.

Leni Riefenstahl’s film Triumph of the Will is often described as aesthetically beautiful but morally evil.

The infamous 1935 propaganda documentary was commissioned by Adolf Hitler. In it, director Riefenstahl portrays the 1934 Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg, Germany as a glorious event and Hitler himself as God-like with a positive vision for his country. Unnervingly, the film is majestic, with beautiful cinematography and an emotive soundtrack underscored by nationalistic Wagner (who else?). It is awe-inspiring in its beauty and chilling in the way it glorifies the fascist Nazis.

In Triumph of the Will, the ‘immoral’ message – that Nazism is good and positive – interrupts our aesthetic appreciation of the work. It is difficult not to devalue Riefenstahl’s work based on its moral content.

Philosophers would generally rather teach people to think for themselves than apply strict censorship rules to artworks.

The moralist would claim that the moral value of an artwork does impact on our overall aesthetic judgement of the work. So does this mean artworks with a good moral message are elevated by their ethical content?

Moralists worry about the influence propaganda films may have in rallying impressionable people to harmful causes – like Nazism. Hitler was likely well aware of this when he commissioned the film. Correspondingly, artists’ concerns about censorship are also valid, if we consider who dictates what should or should not be seen.

Philosophers would generally rather teach people to think for themselves than apply strict censorship rules to artworks. That way, spectators are encouraged to engage critically with the messages they are receiving.

Critical spectatorship

Critical spectatorship is important in the case of biopics like The Big Short. The movie depicts a moral message we may well support, and the mass-market nature of film means it’s a powerful way to quickly take that message to a large number of people. But does it matter if the audience is viewing this narrative as they might a news story? Perhaps we should consider how viewers engage with the news.

Even when watching the broadcast news, viewers should be critical and consider what’s being shown or left out, from whose point of view the story is being told, and with whom or ‘what side’ we’re being positioned to identify. We need to constantly analyse or fact-check what we are told, particularly as we exist in a 24-hour news cycle and receive so much more information than previously.

As social media encourages quick likes and shares, it really is worth pausing to consider the impact such stories may have on others, on society and on our collective cultural myths. This is not to say that we should cease telling all the stories, far from it. But let’s also receive them critically, compassionately and open them up for discussion.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Barbie and what it means to be human

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Georgie Bright The Ethics Centre 23 FEB 2016

On February 8, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced the appointment of Philip Ruddock – the former immigration minister who presided over the Howard government’s notorious “Pacific Solution” to divert asylum seekers from its shores – as Australia’s first special envoy for human rights.

This surprising recycling of Ruddock is part of the government’s campaign for a seat at the United Nations Human Rights Council for the 2018-2020 term.

Not too long ago, then Prime Minister Tony Abbott said Australia was “sick of being lectured to” by the United Nations. But even the new government is demonstrating a willingness to dismiss inconvenient human rights obligations. In Human Rights Watch’s annual World Report – which documents human rights practices in more than 90 countries – Australia’s human rights record over the last year showed how far the country has to go.

It is difficult not to be disillusioned by the state of human rights in Australia. This is especially the case regarding the treatment of migrants and asylum seekers, and the discrimination faced by Indigenous Australians.

Australia’s candidacy for a seat at the Human Rights Council provides an important opportunity for Australia to address its domestic human rights issues.

Australia’s position on refugee protection has been to undermine and ignore international standards rather than uphold them. The country maintains a harsh boat turn-back policy, returning migrants and asylum seekers to countries including Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam after only the most cursory of screenings.

Australia has a policy of mandatory detention for all unauthorised arrivals, transferring migrants and asylum seekers to offshore processing sites in less-equipped countries such as Nauru and Papua New Guinea. An independent review and a report by the Australian Human Rights Commission found evidence of sexual and physical abuse of children on Nauru.

Instead of trying to ensure the safety of the asylum seekers and refugees in Australian immigration detention facilities, the government acted to limit public discussion of important refugee and migrant issues. It passed a law that makes it a crime punishable by two years jail if immigration service providers disclose “protected information”.

Following a ruling by the High Court, 267 asylum seekers in Australia, including 91 children, faced involuntary transfer to Nauru and Manus Island. The High Court ruled on narrow statutory grounds and did not consider Australia’s compliance with international refugee law.

Another area where Australia is falling behind is Indigenous rights. In November 2015, Australia appeared before the UN Human Rights Council to defend its rights record as part of the Universal Periodic Review process. Many countries urged Australia to address disadvantage and discrimination faced by Indigenous Australians. The government’s “Closing the Gap” report for 2016 highlighted mixed progress in meeting targets in education and health, with Indigenous Australians still living on average 10 years less than non-Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous Australians remain disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system, with Aboriginal women being the fastest growing prisoner demographic. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children under the age of 18 are overrepresented in youth detention facilities—representing more than half of child detainees.

Australia’s candidacy for a seat at the Human Rights Council provides an important opportunity for Australia to address its domestic human rights issues.

Australia is a vibrant democracy with a multicultural society and a solid history of protecting and promoting human rights values. Following the horror of World War II, Australia played an integral role in the development of the United Nations. In 1948, Australia’s Dr Herbert Vere Evatt, as president of the General Assembly, oversaw the adoption of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights.

But to regain the moral high ground and respect international law, Australia should urgently address these and other shortcomings in its human rights record. For starters, the government should stop transferring migrants and asylum seekers offshore, and provide them with fair and timely refugee status determination in Australia.

On Indigenous rights, it needs to intensify its commitment to addressing the underlying causes of gaps in opportunities and outcomes in health, education, housing and employment between Indigenous and non-indigenous and do more to address the high incarceration rate.

Australia once was an international human rights leader – and should be again.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Employee activism is forcing business to adapt quickly

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Has passivity contributed to the rise of corrupt lawyers?

BY Georgie Bright

Georgie Bright is the Australia Associate Director for Development and Outreach at Human Rights Watch. Prior to joining Human Rights Watch, she worked in criminal law at Legal Aid Queensland. Georgie holds a law degree from Queensland University of Technology and obtained her Masters in International Human Rights Law at the University of York.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Deontology

Deontology is an ethical theory that says actions are good or bad according to a clear set of rules.

Its name comes from the Greek word deon, meaning duty. Actions that align with these rules are ethical, while actions that don’t aren’t. This ethical theory is most closely associated with German philosopher, Immanuel Kant.

His work on personhood is an example of deontology in practice. Kant believed the ability to use reason was what defined a person.

From an ethical perspective, personhood creates a range of rights and obligations because every person has inherent dignity – something that is fundamental to and is held in equal measure by each and every person.

This dignity creates an ethical ‘line in the sand’ that prevents us from acting in certain ways either toward other people or toward ourselves (because we have dignity as well). Most importantly, Kant argues that we may never treat a person merely as a means to an end (never just as a resource or instrument).

Kant’s ethics isn’t the only example of deontology. Any system involving a clear set of rules is a form of deontology, which is why some people call it a “rule-based ethic”. The Ten Commandments is an example, as is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Most deontologists say there are two different kinds of ethical duties, perfect duties and imperfect duties. A perfect duty is inflexible. “Do not kill innocent people” is an example of a perfect duty. You can’t obey it a little bit – either you kill innocent people or you don’t. There’s no middle-ground.

Imperfect duties do allow for some middle ground. “Learn about the world around you” is an imperfect duty because we can all spend different amounts of time on education and each be fulfilling our obligation. How much we commit to imperfect duties is up to us.

Our reason for doing the right thing (which Kant called a maxim) is also important.

We should do our duty for no other reason than because it’s the right thing to do.

Obeying the rules for self-interest, because it will lead to better consequences or even because it makes us happy is not, for deontologists, an ethical reason for acting. We should be motivated by our respect for the moral law itself.

Deontologists require us to follow universal rules we give to ourselves. These rules must be in accordance with reason – in particular, they must be logically consistent and not give rise to contradictions.

It’s worth mentioning that deontology is often seen as being strongly opposed to consequentialism. This is because in emphasising the intention to act in accordance with our duties, deontology believes the consequences of our actions have no ethical relevance at all – a similar sentiment to that captured in the phrase “Let justice be done, though the heavens may fall”.

The appeal of deontology lies in its consistency. By applying ethical duties to all people in all situations the theory is readily applied to most practical situations. By focussing on a person’s intentions, it also places ethics entirely within our control – we can’t always control or predict the outcomes of our actions, but we are in complete control of our intentions.

Others criticise deontology for being inflexible. By ignoring what’s at stake in terms of consequences, some say it misses a serious element of ethical decision-making. De-emphasising consequences has other implications too – can it make us guilty of ‘crimes of omission’? Kant, for example, argued it would be unethical to lie about the location of our friend, even to a person trying to murder them! For many, this seems intuitively false.

One way of resolving this problem is through an idea called threshold deontology, which argues we should always obey the rules unless in an emergency situation, at which point we should revert to a consequentialist approach.

But is this a cop-out? How do we define ‘emergency’?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership

Political promises and the problem of ‘dirty hands’

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The rights of children

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights