How to build a successful culture

How to build a successful culture

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 2 MAR 2020

They say that what gets measured, gets managed (or improved). But when it comes to measuring corporate culture, that’s an idea that needs unpacking.

The corporate sector has traditionally taken a quantitative approach to risk management and governance. Compliance, regulation, risk and legislative frameworks are applied, analysed, audited and reported-on to varying degrees of accuracy and certainty.

Unfortunately, these management mechanisms do not in themselves lead to effective governance as evidenced by a multitude of corporate scandals and collapses. Overconfidence in the science of risk management can lead to faulty corporate governance – and could well lead to disaster.

The art of risk management and governance lies in the capability of directors and executives to navigate and understand the highly complex and unpredictable set of human behaviours and interactions that make up a modern organisation.

The current scientific approach to risk management is insufficient when seeking to mitigate non-financial risks to business success – leaving companies vulnerable to catastrophic levels of exposure. There is now a shift in thinking and an appreciation that the intangible qualities of culture are critical to the issue of risk management and corporate governance.

Can you measure culture?

The subtle aspects of an organisation, such as values, motivations and political dynamics, are difficult to measure, influence and describe, let alone govern effectively. Performance management and processes, culture and engagement surveys, leadership competency assessments and organisational development initiatives are designed to create visibility of these aspects of organisations, but they often fall short by not accounting for the hidden, unspoken and un-self-aware aspects of human agents and the social systems in which they operate.

For over 20 years The Ethics Centre has been developing a unique approach to navigating these complexities – and, in the process, to accurately measure and understand culture.

Our Everest process assesses the level to which an organisation’s lived culture, and the actual systems and processes that drive the business, align with their intended ethical framework. Through in-depth exploration and analysis, gaps between the ideal and the actual culture of a business emerge, along with areas where formal systems and behaviours are misaligned to the stated values and principles.

Everest digs far deeper than a standard organisational review, identifying themes that relate to experiences over time and between groups of people, and reflecting them against the organisation’s formal policies and procedures. It enables companies to build a climate of trust for clients, shareholders and regulators; to unify employees around a common purpose and encourage values-aligned behaviour; to develop consistency between what you say you believe in and how you act; and to enable consistent decision making. Ultimately reducing the risk of ethical failure and poor decisions.

The Ethics Centre’s Everest process is a tried and tested methodology that produces invaluable insights and recommendations for change. In just the past five years, Everest has been deployed to assess the organisational culture of one of Australia’s largest banks, a major superannuation fund, a leading energy company, a major telco, a mining company and a wagering company – amongst many others.

Transforming organisations

Whilst most of our clients have chosen to keep their Everest reports confidential, two recent clients – The Australian Olympic Committee and Cricket Australia – elected to publicly release the reports into their organisations.

In both instances, these acts of “radical transparency” acted as a circuit-breaker following periods of widespread negative coverage. The release of these reports allowed the organisations to re-boot with renewed purpose and energy.

According to Matt Carroll, the widely-respected CEO of the AOC, “the review conducted by The Ethics Centre provided us with the platform to reset the organisation. We are committed to building a culture that is fit for purpose and aligned to our values and principles.”

Our report on Cricket Australia – following the infamous ball-tampering incident in 2018 – ran to 147 pages and contained 42 detailed recommendations. Our key finding was that a focus on winning had led to the erosion of the organisation’s culture and a neglect of some important values. Aspects of Cricket Australia’s player management had served to encourage negative behaviours.

It was clear, with the release of the report, that many things needed to change at Cricket Australia. And change they did. Cricket Australia committed to enacting 41 of the 42 recommendations made in the report, along with widespread renewal of their executive team and board.

“With culture, it’s something you’ve got to keep working at, keep your eye on, keep nurturing,” says CA’s chairman Earl Eddings. “It’s not: we’ve done the ethics report, so now we’re right.”

Most of the corporate collapses and scandals that have occurred lately were not the result of inadequate risk management, poorly crafted strategy or an absence of appropriate policies. Nor were they caused by incompetence or poorly trained staff.

In almost every case, it is becoming apparent that the causes lay in the psychology, ethics and beliefs of individuals and in an organisational culture that rewards short term value extraction over long term, sustainable value creation.

This misalignment between the espoused purpose, values and principles of an organisation and the real-time decisions being made each day can increase reputational and conduct risk leading to an erosion of trust, disengagement and poor customer outcomes.

Even companies with no burning platform benefit from the rigorous corporate health-check that Everest provides. To quote Ian Silk, CEO of another Everest client Australian Super:

“In my darkest moments I just wondered if we had all drunk the Kool-Aid, and whether the staff surveys reflected the facts. So I thought a really good way to test this would be to get The Ethics Centre to come in and do an entirely independent, entirely objective test of the culture and the ethics in the organisation.”

If you are interested in discussing any of the topics raised in this article in more depth with The Ethics Centre’s consulting team, please make an enquiry via our website.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Banks now have an incentive to change

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The Royal Commission has forced us to ask, what is business good for?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Capitalism is global, but is it ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Activist CEO’s. Is it any of your business?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ready or not – the future is coming

Ready or not – the future is coming

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 2 MAR 2020

We are living in an exceptional era of human history. In a blink of the historical time scale, our species now have the skills to explore the universe, map and modify human genes and develop forms of intelligence that may far surpass their creators.

In fact, given the speed, unpredictability and sheer scale of what was previously unthinkable change, it’s actually better to talk of the future in the plural rather than the singular: the ‘futures’ are coming.

With the convergence of genetic engineering, AI and neurotechnology, entirely unique challenges arise that could test our assumptions about human identity and what connects us together as a species. What does the human experience mean in an era of augmentation, implantation, enhancement and editing of the very building blocks of our being in the future? What happens when we not only hack the human body, but the human mind?

The possible futures that are coming will arrive with such speed that those not ready for them will find themselves struggling to know how to navigate and respond to a world unlike the one we currently know. Those that invest in exploring what the future holds will be well placed to proactively shape their current and future state so they can traverse the complexity, weather the challenges, and maximise the opportunities the future presents.

The Ethics Centre’s Future State Framework is a tailored, future-focused platform for change management, cultural alignment and staff engagement. It draws on futuring methodologies, including trend mapping and future scenario casting, alongside a number of design thinking and innovation methodologies. What sets Future State apart is that it incorporates ethics as the bedrock for strategic and organisational assessment and design. Ethics underpins every aspect of an organisation. An organisation’s purpose, values and principles set the foundation for its culture, gives guidance to leadership, and sets the compass needed to execute strategy.

The future world we inhabit will be built on the choices we make in the present. Yet due to the sheer complexity of the multitudes of decisions we make every day, it’s a future that is both unpredictable and emergent. The laws, processes, methods and current ways of thinking in the present may not serve us well in the future, nor contribute best to the future that we want to create. By envisioning the challenges of the future through an ethics-centred design process, the Future State Framework ensures that organisations and their culture are future-proof.

The Future State Framework has supported numerous organisations in reimagining their purpose and their unique economic and social role in a world where profit is rapidly and radically being redefined. Shareholder demand is moving beyond financial return, and social expectations toward the role of corporations are shifting dramatically into the future.

The methodology helps organisations chart a course through this transformation by mapping and targeting their desired future state and developing pathways for realising it. It been designed to support and guide both organisations facing an imminent burning platform and those wanting to be future forward and leading – giving them the insight to act with purpose – fit for the many possibilities the future might hold.

If you are interested in discussing any of the topics raised in this article in more depth with The Ethics Centre’s consulting team, please make an enquiry via our website.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Who are corporations willing to sacrifice in order to retain their reputation?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Economic reform must start with ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

Explainer, READ

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Moral hazards

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in the Boardroom

Ethics in the Boardroom: A Decision-Making Guide for Directors

Ethics in the Boardroom: A Decision-Making Guide for Directors

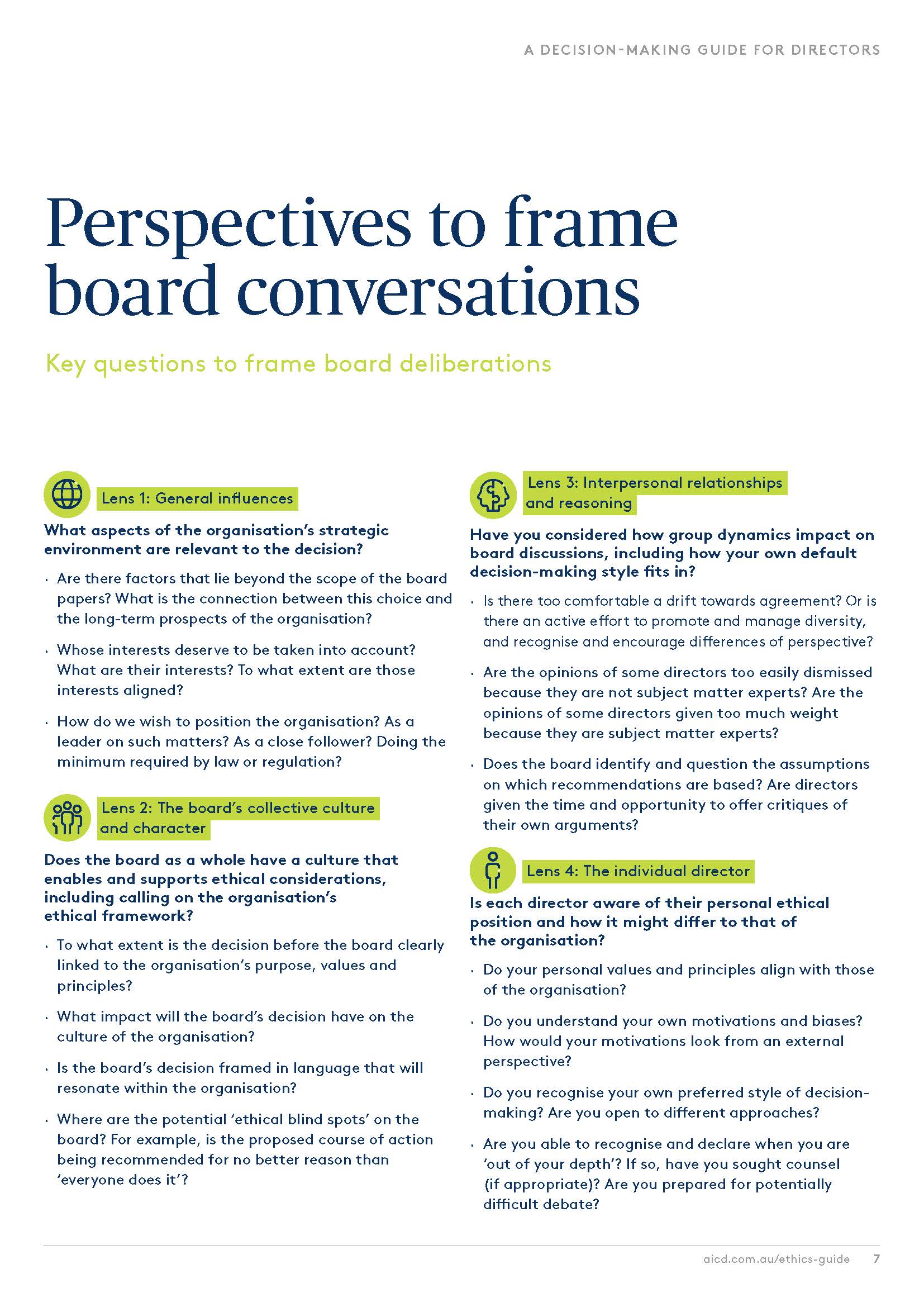

The role of a director in governing an organisation is made more complex by a myriad of ethical issues that impact on board decision-making. Boardroom practices are also central to setting the right tone and values throughout an organisation.

Ethics in the Boardroom: A Decision-Making Guide has been developed in collaboration with the Australian Institute of Company Directors. Designed to support directors in considering ethical issues as they discharge their duties, it invites them to view the decisions they come up against through four key lenses.

This report is a vital resource for directors as a general reference, should be utilised by boards to strengthen their capacity in ethics, and by individual directors and boards alike to inform conversations about the complex issues they encounter in their roles.

"The the board of a corporation is, in effect, its mind and conscience. All that a corporation does and its effects on the world, is ultimately traced back to directors and their deliberations."

DR SIMON LONGSTAFF AO

WHATS INSIDE?

Understanding Ethics

Perspectives to frame board conversations

A decision making framework

General influences

The board’s collective culture and character

Interpersonal relationships and reasoning

The individual director

Practical Examples

Whats inside the guide?

AUTHORS

Authors

The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing and delivering innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of personal and professional life. Our activities span ethics consulting and leadership for organisations from all sectors and of all sizes, Ethi-call, our free ethics helpline, live events, and advocacy campaigns. Our work brings people together to build their skills and capacity to live and act according to their values.

Australian Institute of Company Directors

The Australian Institute of Company Directors is committed to strengthening society through world-class governance. They aim to be the independent and trusted voice of governance, building the capability of a community of leaders for the benefit of society. Their membership of more than 45,000, includes directors and senior leaders from business, government and the not-for-profit sectors.

DOWNLOAD A COPY

You may also be interested in...

Nothing found.

Extending the education pathway

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 16 JAN 2020

In the course of 2019, The Ethics Centre reviewed and adopted a new strategy for the five years to 2024.

The key insight to emerge from the strategic planning process was that the Centre should focus on growing its impact through innovation, partnerships, platforms and pathways.

We focus here on just one of those factors – ‘pathways’ and, in particular, the education pathway.

The Ethics Centre is not new to the education game. To this day, the establishment of Primary Ethics – which teaches tens of thousands of primary students every week in NSW – is one of our most significant achievements.

As Primary Ethics continues to break new ground, we feel it’s time to bring our collective skills to bear along the broader education pathway.

With this in mind, we’re delighted to report that The Ethics Centre and NSW Department of Education and Training have signed a partnership to develop curriculum resources and materials to support the teaching and learning of ethical deliberation skills in NSW schools, including within existing key learning areas.

This exciting project will see us working with and through the Department’s Catalyst Innovation Lab alongside gifted teachers and curriculum experts – rather than merely seeking to influence from the outside.

In addition, we have also formed a further partnership with one of the Centre’s Ethics Alliance members, Knox Grammar School. This will involve the establishment of an ‘Ethicist-in-residence’ at the school, the application of new approaches to exploring ethical challenges faced by young adults, and the development of a pilot program where students in their final years of secondary education undertake an ethics fellowship at the Centre.

In due course, we hope that the work pioneered in these two partnerships and others will produce scalable platforms that can be extended across Australia. Detailed plans come next, and we believe the potential for impact along this pathway is significant.

We believe ethics education is a central component of lifelong learning – extending from the earliest days of schooling through secondary schooling, higher education and into the workplace.

The broadening of the education pathway therefore provides new opportunities for The Ethics Centre and Primary Ethics to work together – sharing our complementary skills and experience in service of our shared objectives, for the common good.

If you have an interest in supporting this work, at any point along the pathway, then please contact Dr Simon Longstaff at The Ethics Centre, or Evan Hannah, who leads the team at Primary Ethics.

Dr Simon Longstaff is Executive Director of The Ethics Centre: www.ethics.org.au

Evan Hannah can be contacted via Primary Ethics at: www.primaryethics.com.au

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Online grief and the digital dead

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How can Financial Advisers rebuild trust?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Housing affordability crisis: The elephant in the room stomping young Australians

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The thorny ethics of corporate sponsorships

The thorny ethics of corporate sponsorships

WATCHBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance The Ethics Centre 10 DEC 2019

With a workforce that increasingly prizes purpose led organisations, how can businesses make mutually beneficial brand alignments as an extension of their own values?

And what should they do if it all goes horribly wrong? In this series of short interviews, The Ethics Alliance draw on the experiences of organisations who have successfully overseen hugely profitable and meaningful partnerships and weathered the crisis of negative associations to pave a way forward.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A new guide for SME’s to connect with purpose

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Myths about diversity for employers to watch

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Leaders, be the change you want to see.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ready or not – the future is coming

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Explainer: Getting to know Richard Branson's B Team

Explainer: Getting to know Richard Branson’s B Team

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance Cris 5 DEC 2019

If you ever dreamed of rubbing shoulders with the brightest shining stars of business, you probably couldn’t turn down an invitation to join Richard Branson’s B Team.

The team of luminaries was launched by the Virgin Group founder in 2013 to power a movement to use business to build a better world.

Its goals

The B Team aims to “confront the crisis of conformity in leadership”.

“We need bold and brave leaders, willing and able to transform their own practices by embracing purpose-driven and holistic leadership, with humanity at the heart, aligned with the principles of sustainability, equality and accountability,” according to its website.

“Plan A – where business has been motivated primarily by profit – is no longer an option. We knew this when we came together in 2013. United in the belief that the private sector can, and must, redefine both its responsibilities and its own terms of success, we imagined a ‘Plan B’ – for concerted, positive action to ensure business becomes a driving force for social, environmental and economic benefit.

“We are focused on driving action to achieve this vision by starting ‘at home’ in our own companies, taking collective action to scale systemic solutions and using our voice where we can make a difference.”

Membership

Aside from Branson himself, who has charisma to burn, his hand-picked team of leaders include:

- Co-founder and former Puma chair, Jochen Zeitz

- Chairman & CEO of Kering, François-Henri Pinault

- Chairman Emeritus, Tata Sons, Ratan Tata

- Chairman, Yunus Centre, Professor Muhammad Yunus

- General Secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation Sharan Burrow

- President and CEO, Mastercard, Ajay Banga

- Founder and CEO of Thrive Global, Arianna Huffington

- Former Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Dow Chemical and DowDuPont, Andrew Liveris

Its influence

Branson is a master of marketing, and has long cultivated an image of a fun-loving, brilliant, rule-breaking entrepreneur with a socially-responsible heart. He has launched around 400 companies and has become one of the world’s most influential leaders, with a personal wealth estimated at $7.7 billion.

A stay at his luxury resort Necker Island in the British Virgin Islands is the modern-day equivalent of Charlie Bucket’s “golden ticket” to the chocolate factory (from the Roald Dahl children’s book). It was, for instance, the first holiday destination for the Obama family after they left the White House in 2017.

Branson has long harnessed his star power to humanitarian ventures and he has now provided B Team “vehicles” for others to do the same.

Its projects

The B Team has three causes:

Climate: committing to a just transition to net-zero emissions by 2050.

Workplace equality: creating working environments that recognise and respect the human rights and talents of all people.

Governance: raising the bar on what good governance looks like – and keeping accountability, sustainability and equality at the centre of these efforts.

Recent achievements

At the UN Climate Action Summit in September, B Team Leader and Allianz CEO Oliver Bäte led a group of 12 asset owners with $A3.5 trillion in assets under management in committing to net-zero emissions by 2050—a target aligned with a pathway to 1.5°C warming – and helping companies within their portfolios to achieve the same goal. They join the 87 companies who also made this commitment.

In 2015, The B Team was instrumental in ensuring that a commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050 was included in the text of the Paris Agreement.

In Australia

The local arm of the B Team launched in October 2018 and includes Branson, Sharan Burrow as vice-chair, ANZ Bank chair David Gonski as co-chair, and Chief Executive Women director Lynette Mayne as co-chair. Other members are:

- Scentre Group CEO Peter Allan

- Suncorp Group CEO Michael Cameron

- Former Chairman and CEO of Dow Chemical, Andrew Liveris

- CEO of MLC, Geoff Lloyd

- CEO of Mirvac Susan Lloyd Hurwitz

- Australian Council for International Development president Sam Mostyn

- Chairman of the Light Warrior Group Radek Sali

- Executive Chairman of Carnival Australia Ann Sherry

- EnergyAustralia managing director Catherine Tanna.

MLC’s Lloyd says the group aims to use the power of its influence to make the conversations “go viral”.

“It is about a core group of leaders who will represent those principles and drive those initiatives and connect through to the global B Team. We are trying to create a conversation and lead that conversation through the individuals in those businesses that are part of it.

“The principles are really all there to help leaders lead their businesses and provide a course, if you like, direction, some guidance as to how we should think very differently about work.

“There is a community expectation that business is there to do good.”

The 100% Human project

This initiative brings together more than 150 organisations around the world to shape and identify the elements that define a 100% Human organisation: respect, equality, growth, belonging and purpose. The aim is to recruit to the cause one million companies globally.

100% Human has been collecting examples of innovative thinking in its published Experiments Collection, which provides details of around 200 workplace initiatives, which are trying out new ways of working. These “experiments” include: providing opportunities for refugees and migrants; championing diversity, inclusion and belonging; and supporting employees’ mental health and wellbeing.

The initiative was launched in Australia in June, 2019 with the five principles of: strategically planning for technology, creating career growth opportunities, focusing on the whole person, establishing support networks, and being publicly accountable.

The former CEO of Perpetual Ltd, Lloyd joined MLC Wealth a year ago to engineer its separation from the National Australia Bank. He says he introduced some of 100% Human’s leadership philosophies to Perpetual in 2015 and is now using them to help develop a new, individual workplace culture at MLC.

“At MLC, we’re reviewing all of our people processes and policies and aligning our culture towards that of allowing people to be 100% human at work,” he says. “So, that’s from our leave policies, our carer leave, our flexibility, the way in which we lead ourselves, the way in which our leadership team really do express, and understand that our team have complex lives and needs.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Our regulators are set up to fail by design

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: How to approach differing work ethics between generations?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY Cris

Pay up: income inequity breeds resentment

Pay up: income inequity breeds resentment

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith Cris 5 DEC 2019

Public outrage over multi-million dollar CEO salaries will never go away when employees are underpaid. It offends our sense of fairness and the increasingly threadbare notion of Australia as an egalitarian nation.

This point is not lost on many who read about Woolworths’ admission it underpaid nearly 6,000 staff over ten years by a total $300 million.

The supermarket chain had failed to account for the actual hours that staff were working, with out-of-business-hours work patterns attracting penalty rates, which were not being added to their salaries.

Other companies which have been caught out with similar underpayments include Qantas, ABC, Commonwealth Bank, Bunnings, Super Retail Group and Michael Hill Jewellers.

While some business leaders laid blame on the complexity of modern awards, Fair Work Ombudsman, Sandra Parker said employers were at fault with “ineffective governance combined with complacency and carelessness toward employee entitlements”.

Human resources leader, Alec Bashinsky, was succinct in his response: “This is 101 stuff and not acceptable in any scenario”. For 14 years, Bashinsky was Asia Pacific talent leader for Deloitte, which employed more than 3,000 people in Australia alone.

Revelations such as the underpayments just add more fuel to the conflagration of distrust and anger, which has led to the rise of anti-establishment political movements around the world.

In Australia, it builds on a mountain of evidence of businesses behaving badly, following revelations of the deliberate underpayments and worker exploitation in the franchising sector and the litany of unethical decision-making unearthed in the recent Royal Commission into financial services.

CEO’s get richer, worker pay stagnates

While company reputations have been trashed over the past couple of years, business leaders have continued to prosper. Company boards responded to public resentment over CEO salaries by reducing the pay of incoming CEO’s… while handing out the second-biggest bonuses of the past 18 years.

Thanks to those bonuses, the median realised pay for an ASX100 CEO reached $4.5m in the last financial year, according to a report by the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors.

Leaders whose companies were directly involved in recent scandals have been punished. Big bank CEO’s saw their remuneration fall over the past year. However, total remuneration for top 50 CEO’s increased by 4 per cent on average, compared to general wage growth at 2.2 per cent, according to the Australian Financial Review.

Macquarie Bank’s Shemara Wikramanayake was the highest paid with $18 million, followed by Goodman Group’s Gregory Goodman with $12.8 million.

Labor MP and economist, Andrew Leigh says the growing gap between the leaders and the led poses a threat to the Australian ethic of egalitarianism.

“Australia is a country where we don’t have private areas on the beaches, we like to say ‘mate’ rather than ‘sir’, we sit in the front seat of taxis and we don’t stand up when the prime minister enters the room,” says Leigh, who is also Deputy Chairman of the Parliamentary Economics Committee.

Former chairman of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, Allan Fels, has written: “The increase in pay levels for CEO’s has occurred at a time when public trust in business is at a low ebb and wages growth in the broader economy can best be described as anaemic”.

The rising levels of income inequality create serious social harm, according to the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS).

Someone in the highest one per cent now earns more in a fortnight than someone in the lowest 5 per cent earns in an entire year.

“Excessive inequality in any society is harmful. When people with low incomes and wealth are left behind, they struggle to reach a socially acceptable living standard and to participate in society. This causes divisions in our society,” according to ACOSS, after the release of its Inequality in Australia report in July.

“Too much inequality is also bad for the economy. When resources and power are concentrated in fewer hands, or people are too impoverished to participate effectively in the paid workforce, or acquire the skills to do so, economic growth is diminished.”

Reining in the excesses

Investors have a mechanism to act if they believe boards have been overly-generous in executive remuneration. In 2018, 12 companies in the ASX200 had shareholders vote down board remuneration reports in a “first strike” action. A further seven were close to experiencing a first strike.

According to the “two-strike rule”, if subsequent remuneration reports are voted down by at least 25 per cent of shareholders, the board positions may be subject to a spill motion. At this point, no company has experienced a board spill as a result of this rule.

The two-strike rule came into effect in 2011 after a Productivity Commission Inquiry into Executive Remuneration found that executive pay went up over 250 per cent from 1993 to 2007.

Labor went into the last Federal election with a policy aimed at encouraging more moderation in executive pay, requiring companies to publish the ratio of the CEO remuneration to the median workers’ pay.

At present, ASX-listed companies have to publish their policies for determining the nature and amount of remuneration paid to key management personnel. However, without a requirement to divulge what the median worker is paid, a ratio cannot be calculated.

The United Kingdom and the United States have both introduced new regulation to require their biggest listed companies to divulge and justify the difference between executive salaries and average annual pay for their employees.

This is going to put more pressure on CEO salaries as the public gets a clear picture. Research in the US shows, for instance, that the average person thinks the pay ratio is 30:1 when the average is actually closer to 300:1.

Those disclosures can have material impacts on a business. The US city of Portland has imposed a 10 per cent tax surcharge on companies with top executives making more than 100 times what their median worker is paid and a 20 per cent surcharge if pay gaps exceed 250 to one.

Leigh says the top 50 CEO’s in Australia are now earning packages at a ratio of around 150 or 200 of median wages in their organisations.

“Those ratios are truly out of whack. If you go back to the 1950s, and 1960s, workers at Australia’s largest firms could earn in a decade what the CEO earned in a year.

“Now, it would take multiple careers for workers in many firms to earn what the CEO earns in a year.”

Setting a fair pay formula

When you have these two issues running concurrently – ever-rising CEO pay and underpayment of workers – it seems appropriate to take a new look at what fair pay looks like.

Some companies have tried to ensure fairness by setting CEO pay as a multiple of the salary of an organisation’s lowest-paid worker.

Mondragon is a Spanish co-op famous for its egalitarian principles. Its CEO is paid nine times more than what its lowest-paid worker earns. In comparison, the CEO of an average FTSE 100 company is paid 129 times what their lowest-paid worker earns.

Mondragon is not well-known in Australia, but is a vast global enterprise, employing more than 75,000 people in 35 countries and with sales of more than Euro12 billion per year – equivalent to Kellogg or Visa.

US ice cream company Ben & Jerry’s took inspiration from Mondragon, setting a five-to-one salary ratio when it started in 1985.

Writing in their book Ben Jerry’s Double Dip: How to Run a Values Led Business and Make Money Too, the founders Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield say: “The compressed salary ratio dealt with an issue that’s at the core of people’s concerns about business and their alienation from their jobs: the people at the bottom of the ladder, the people who do all the actual physical work, are paid very poorly compared to the people at the top of the ladder.

“When we started our business, we were the people at the bottom. That’s whom we identified with. So we were happy to put into place a system whereby anytime the people on the top of the organisation wanted to give themselves a raise, they’d have to give the people on the bottom a raise as well.”

Ben & Jerry’s kept that arrangement in place for 16 years but, when Cohen wanted to retire, attracting a replacement CEO meant raising the rate to a seven-to-one ratio.

“ … as the company grew, the salary ratio became problematic. Some people in upper-level management believed that we couldn’t afford to raise everyone’s salaries, and the salary ratio was, therefore, limiting the offers we could make to the top people we could recruit,” wrote the founders in 1998.

“Other people – Ben included – thought money wasn’t the problem, and that we’d always had problems with our recruitment process. Ben points out frequently that eliminating the salary ratio, which we did in 1995, has not eliminated our recruiting problems.”

The New Zealand Shareholders Association has also called (in 2014) for CEO base pay to be capped at no more than 20 times the average wage.

Fairness is important to us

Leigh, who wrote a book Battlers and Billionaires on inequality, says people naturally benchmark themselves against those around them: “That is how we figure out what we are worth”.

The point is that people care less about the dollar figure they are paid than they do about how it compares to others. If they think it is unfair, their attitude at work and motivation suffers.

“People work less hard when they feel they have not been adequately recognised within the firm,” says Leigh.

Pay transparency – making salaries public knowledge – can be a two-edged sword. People further down the “pecking order” feel worse when they see how others are paid more. However, people should be able to find out where they stand and what they need to do to climb the salary ladder.

“If you are running a firm where the pay structure is only sustainable because you are keeping it secret, then you are walking on eggshells. Ultimately, good managers should be able to be transparent with their staff. Secrecy shouldn’t be a way of doing business,” says Leigh.

“If you are playing football with David Beckham, you don’t begrudge the fact that David Beckham is pulling in a higher salary package than you. The problem arises when there are inequities that aren’t related to performance.

“People are comfortable with the fact that a full-time worker will earn more than a part-time worker, that someone who has another 20 years’ experience gets rewarded for that experience. But, if you are being paid more just because you are family friends with the CEO or you share the same race as the CEO or the same gender, then that is not fair.

“So pay transparency can produce fairer workplaces.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Survivors are talking, but what’s changing?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Office flings and firings

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How ‘ordinary’ people became heroes during the bushfires

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY Cris

Taking the bias out of recruitment

Taking the bias out of recruitment

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith Cris 5 DEC 2019

When recruiters sift through job applications, they take less than 10 seconds to decide whether someone will be lucky enough to get through to the next round. If your CV doesn’t grab their attention immediately, you’re done.

“Millions of people are getting hired and fired every single day,” says Kate Glazebrook, CEO and founder of the Applied recruitment platform.

“And if you look at your average hiring process, it involves usually 40 to 70 candidates applying to a particular job.”

Decisions made at this speed require shortcuts. They rely on gut feelings, which essentially are a collection of biases. Without even being conscious that they are doing it, recruiters and hiring managers discriminate because they are human, and they are in a hurry.

Glazebrook says most hiring decisions are made in the “fast brain”, which is fast, instinctive and emotional. “That’s the automatic part of our brain, the part of the brain uses fewer kilojoules so we can make hot, fast decisions,” she says.

“We’re often not even aware of the decisions we take with our fast brain.” The fast brain/slow brain concept references work by Nobel Prize-winning psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman, who studied cognitive biases.

The “slow brain” refers to thought processes that are slower, more deliberative and more logical.

“And I think it’s clear that when you’re 69 candidates down, it’s 5pm on a Friday, you’re definitely less likely to be using your slow, deliberative part of your brain, and much more likely to be using your fast brain,” Glazebrook says.

‘We all overlook people who don’t look the part’

The inherent biases in traditional recruitment practices go some way to explaining the slow and limited progress of diversity and inclusion in our organisations.

“There’s, sadly, lots of meta-analyses showing just how systematically we all overlook people who don’t tend to look the part,” she says. “And there’s evidence to suggest that minority groups of all kinds are overlooked, even when they’re equally qualified for the job.”

Bias against people with non-Anglo sounding names was famously demonstrated in an Australian National University study of 4,000 fictitious job applications for entry-level jobs.

“To get as many interviews as an Anglo applicant with an Anglo-sounding name, an Indigenous person must submit 35 per cent more applications, a Chinese person must submit 68 per cent more applications, an Italian person must submit 12 per cent more applications, and a Middle Eastern person 64 per cent more applications,” wrote the authors of the 2013 study.

Lack of diversity is a business risk. According to Applied, diverse teams bring different ideas to the table, so that teams don’t approach problems in the same way. This tends to make diverse teams better at solving complex problems.

Consequently, an increasing number of employers are committing to “anonymised recruiting”. Also known as “blind recruitment”, this process removes all identifying details from a job application until the final interviews.

In the initial candidate “sifting process”, recruiters and hiring managers do not know the name, gender, or age of the applicants. They can also not make any judgements based on the name of the university or high school the applicants attended or their home address.

When the State Government of Victoria trialled anonymised recruiting for two years, it discovered overseas-born job seekers were 8 per cent more likely to be shortlisted, women were 8 per cent more likely to be shortlisted and hired, and applicants from lower socio-economic suburbs were 9.4 per cent more likely to progress through the selection process and receive a job offer.

According to academics researching the trial, “… at the Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance we found that before de-identifying CVs men were 33 per cent more likely to be hired than women. After de-identification, this flipped and women were eight per cent more likely to be hired than men”.

Connecting to brain function

Glazebrook is an Australian-born behavioural economist working in the UK’s Behavioural Science Team, when she co-founded Applied in 2016 with Richard Marr. They aimed to use their understanding of how the brain works to offer a beginning-to-end anonymised hiring.

Applied runs the whole process, from crafting bias-free job specifications and advertising, to candidate testing and selection. Beyond removing identifying details, the company also breaks up assessment tasks among a team of people and randomises the order in which elements are looked at – to minimise the impact of other cognitive biases.

Applied’s clients include the British Civil Service, Penguin Random House and engineering firm the Carey Group. In the past three years, the company has dealt with more than 130,000 candidates.

“We’ve seen a two to four times increase in the rate at which ethnically diverse candidates are applying to jobs and getting jobs through the platform,” she says.

More than half of the candidates who have received job offers are women and there have been “significant uplifts” in diversity in other dimensions, such as disability and economic status.

Glazebrook says US companies spend $US8 billion annually on anti-bias, diversity and inclusion training. However, even with the best intentions of everyone involved, it seems to have limited effectiveness.

“The rate of change is quite slow,” she says.

There is even some evidence that anti-bias training can backfire. Glazebrook says a concept called moral licensing is a concern: “Once you do the training, you tick a box in your brain that says ‘Great. I’m de-biased. Excellent. Moving on’.

“And, actually, you are free to be more biased than you were before because we’re led to believe we have overcome that particular bias,” she says.

Studies show companies openly committed to diversity are as likely to discriminate as those who aren’t.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How ‘ordinary’ people became heroes during the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

It’s time to increase racial literacy within our organisations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY Cris

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 28 NOV 2019

As I look back on the week of turmoil that has engulfed Westpac, my overwhelming feeling is one of sadness.

I am sad for the children whose lives may have been savaged by sexual predators using the bank’s faulty systems. I am sad for the tens of thousands of Westpac employees who may feel tainted by association with the bank’s failings. I am sad for individuals, like Brian Hartzer and Lindsay Maxsted, whom I believe will be remembered more for the manner of their parting from the bank than for all the good that they did along the way. All of them deserve better.

None of this lessens my judgement about the seriousness of the faults identified by Austrac. Nor is sadness a reason for limiting the adverse consequences borne by individuals and the company.

Rather, in the pell-mell of the moment – super-charged by media and politicians enjoying a ‘gotcha’ moment – it is easy to forget the human dimension of what has occurred – whether it be the impact on the victims of sexual exploitation or the person whose pride in their employer has been dented.

Behind the headlines, beyond the outrage, there are people whose lives are in turmoil. Some are very powerful. Some are amongst the most vulnerable in the world. They are united by the fact that they are all hurt by failures of this magnitude.

For Westpac’s part, the company has not sought to downplay the seriousness of what has occurred. There has not been any deflection of blame. There has been no attempt to bury the truth. If anything, the bank’s commitment to a thorough investigation of underlying causes has worked to its disadvantage – especially in a world that demands that the acceptance of responsibility be immediate and consequential.

The issue of responsibility has two dimensions in this particular case: one particular to Westpac and the other more general. First, there are some people who are revelling in Westpac’s fall from grace. Many in this group oppose Westpac’s consistently progressive position on issues like sustainability, Indigenous affairs, etc. Some take particular delight in seeing the virtuous stumble. However, this relatively small group is dwarfed by the vast number of people who engage with the second dimension – the sense that we have passed beyond the days of responsible leadership of any kind.

I suspect that Westpac and its leadership are part of the ‘collateral damage’ caused by the destruction of public trust in institutions and leadership more generally.

When was the last time a government minister, of any party in any Australian government, resigned because of a failure in their department? Why are business leaders responsible for everything good done by a company – but never any of its failures?

Some people think that the general public doesn’t notice this … or that they do not care. They’re wrong on both counts. I suspect that the general public has had a gut-full of the hypocrisy. They want to know why the powerless constantly being held to account while the powerful escape all sanction?

I think that this is the fuel that fed the searing heat applied to Westpac and its leadership earlier this week. The issues in Westpac were always going to invite criticism but this was amplified by a certain schadenfreude amongst Westpac’s critics and the general public’s anger at leaders who refuse to accept responsibility.

So, what are we to make of this?

One of the lessons that people should keep in mind when they volunteer for a leadership role is that strategic leaders are always responsible; even when they are not personally culpable for what goes wrong on their watch. This is not fair. It’s not fair that a government minister be presumed to know of everything that is going on in their department. It’s not fair to expect company directors or executives to know all that is done in their name. It is not fair.

However, it is necessary that this completely unrealistic expectation, this ‘fiction’, be maintained and that leaders act as if it were true. Otherwise, the governance of complex organisations and institutions will collapse. Then things that are far worse than our necessary fictions will emerge to fill the void; the grim alternatives of anarchy or autocracy.

It’s sad that we have come to a point where this even needs to be said.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Business + Leadership

Big Thinker: Karl Marx

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Renewing the culture of cricket

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 26 NOV 2019

On March 24, 2018, at Newlands field in South Africa, Australian cricketer Cameron Bancroft was captured on camera tampering with the match ball with a piece of sandpaper in the middle of a test match.

It later emerged that the Australian team captain Steve Smith and vice-captain David Warner were complicit in the plan. The cheating was a clear breach of the rules of the game – and the global reaction to Bancroft’s act was explosive. International media seized on the story as commentators sought to unpack cricket’s arcane rules and its code of good sportsmanship. From backyard barbeques to current and former prime ministers, everyone had an opinion on the story.

For the players involved, retribution was swift. Smith and Warner received 12-month suspensions from Cricket Australia, whilst Bancroft received a nine-month suspension. The coach of the Australian team, Darren Lehman, quit his post before he had even left South Africa.

But it didn’t stop there. Within nine months, Cricket Australia lost four board directors – Bob Every, Chairman David Peever, Tony Harrison and former test cricket captain Mark Taylor – and saw the resignation of longstanding CEO James Sutherland as well as two of his most senior executives, Ben Amarfio and Pat Howard.

So, what happened between March and November? How did an ill-advised action on the part of a sportsman on the other side of the world lead to this spectacular implosion in the leadership ranks of a $400 million organisation?

The answer lies in the idea of “organisational culture,” and an independent review of the culture and governance of Cricket Australia by our organisation – The Ethics Centre.

Cricket Australia sits at the centre of a complex ecosystem that includes professional contract players, state and territory associations, amateur players (including many thousands of school children), broadcasters, sponsors, fans and hundreds of full-time staff. As such, the organisation carries responsibility for the success of our national teams, the popularity of the sport and the financial stability of the organisation.

In the aftermath of the Newland’s incident, many wanted to know whether the culture of Cricket Australia had in some way encouraged or sanctioned such a flagrant breach of the sport’s rules and codes of conduct.

Our Everest process was employed to measure Cricket Australia’s culture, by seeking to identify the gaps between the organisations “ethical framework” (its purpose, values and principles) and it’s lived behaviours.

We spoke at length with board members, current and former test cricketers, administrators and sponsors. We extensively reviewed policies, player and executive remuneration, ethical frameworks and codes of conduct.

Our final report, A Matter of Balance – which Cricket Australia chose to make public – ran to 147 pages and contained 42 detailed recommendations. Our key finding was that a focus on winning had led to the erosion of the organisation’s culture and a neglect of some important values. Aspects of Cricket Australia’s player management had served to encourage negative behaviours.

It was clear, with the release of the report, that many things needed to change at Cricket Australia. And change they did.

Cricket Australia committed to enacting 41 of the 42 recommendations made in the report.

In a recent cover story in Company Director magazine – a detailed examination of the way Cricket Australia responded in the aftermath of The Ethics Centre’s report – Cricket Australia’s new chairman Earl Eddings has this to say:

“With culture, it’s something you’ve got to keep working at, keep your eye on, keep nurturing. It’s not: we’ve done the ethics report, so now we’re right.”

Now, one year after the release of The Ethics Centre’s report, the culture of Cricket Australia is making a strong recovery. At the same time as our men’s team are rapidly regaining their mojo (it’s probably worth noting that our women’s team never lost it – but that’s another story).

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships