Our dollar is our voice: The ethics of boycotting

Our dollar is our voice: The ethics of boycotting

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 FEB 2026

Boycotts can be an effective mechanism for making change. But they can also be weaponised or harmful. Here are some tips to ensure your spending aligns with your values.

There I was, strolling through campus as an undergraduate in the 1990s, casually enjoying a KitKat, when I was accosted by a friend who sternly rebuked me for my choice of snack. Didn’t I know that we were boycotting Nestlé? Didn’t I know about all the terrible things Nestlé was doing by aggressively promoting its baby formula in the developing world, thus discouraging natural breastfeeding?

Well, I did now. And so I took a break from KitKats for many years. Until I discovered the boycott had started and been lifted years before my run-in with my activist friend. As it turned out, a decade prior to my campus encounter, Nestlé had already responded to the boycotters’ concerns and had subsequently signed on to a World Health Organization code that limited the way infant formula could be marketed. So, while my friend was a little behind on the news, it seemed the boycott had worked after all.

Boycotts are no less popular today. In late 2025, dozens of artists pulled their work from Spotify and thousands of listeners cancelled their accounts after discovering that the company’s CEO, Daniel Ek, invested over 100 million Euros into a German military technology company that is developing artificial intelligence systems. In 2023, Bud Light lost its spot as the top-selling beer in the United States after drinkers boycotted it following a social media promotion involving transgender personality, Dylan Mulvaney. The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement has been promoting boycotts of Israeli products and companies that support Israel for over a decade, gaining greater momentum since the 2023 war in Gaza. And there are many more.

As individuals, we may not have the power to rectify many of the great ills we perceive in the world today, but as agents in a capitalist market, we do have power to choose which products and services to buy.

In this regard, our dollar is our voice, and we can choose to use that voice to protest against things we find morally problematic. Some people – like my KitKat-critical friend – also stress that we must take responsibility for where our money flows, and we have an obligation to not support companies that are doing harm in the world.

However, thinking about whom we support with our purchases puts a significant ethical burden on our shoulders. How should we decide which companies to support and which to avoid? Do we have a responsibility to research every product and every company before handing over our money? How can we be confident that our boycott won’t do more harm than good?

Buyer beware

Boycotts don’t just impose a cost on us – primarily by depriving us of something we would otherwise purchase – they impose a cost on the producer, so it’s important to be confident that this cost is justified.

If buying the product would directly support practices that you oppose, such as damaging the environment or employing workers in sweatshops, then a boycott can contribute to preventing those harms. We can also choose to boycott for other reasons, including showing our opposition to a company’s support for a social issue, raising awareness of injustices or protesting the actions of individuals within an organisation. However, if we’re boycotting something that was produced by thousands of people, such as a film, because of the actions of just one person involved, then we might be unfairly imposing a cost on everyone involved, including those who were not involved in the wrongdoing.

Boycotts can also be used threaten, intimidate or exclude people, such as those directed against minorities, ethnic or religious groups, or against vulnerable peoples. We need to be confident that our boycott will target those responsible for the harms while not impinging on the basic rights or liberties of people who are not involved.

There are also risks in joining a boycott movement, especially if we feel pressured into doing so or if activists have manipulated the narrative to promote their perspective over alternatives. Take the Spotify boycott, for example. It is true that Spotify’s CEO invested in a military technology company. However, many people claimed that company was supplying weapons to Israel, and that was a key justification for them pulling their support for Spotify. However, Helsing had no contracts with Israel and was, instead, focusing its work on the defence of Ukraine and Europe – a cause that many boycotters might even support.

Know your enemy

The risk of acting on misinformation or biased perspectives places greater pressure on us to do our own research, and it’s here that we need to consider how much homework we’re actually willing or able to do.

In the course of writing this article, I delved back into the history of the Nestlé boycott only to find that another group has been encouraging people to avoid Nestle products because it doesn’t believe that the company is conforming to its own revised marketing policies. Even then, uncovering the details and the evidence is not a trivial undertaking. As such, I’m still not entirely sure where I stand on KitKats.

While we all have an ethical responsibility to act on our values and principles, and make sure that we’re reasonably well informed about the companies and products that we interact with, it’s unreasonable to expect us to do exhaustive research on everything that we buy. That said, if there is reliable information that a company is doing harm, then we have a responsibility to not ignore it and should adjust our purchasing decisions accordingly.

Boycotts also shouldn’t last for ever; an ethical boycott should aim to make itself redundant. Before blacklisting a company, consider what reasonable measures it could take for you to lift your boycott. That might be ceasing harmful practices, compensating those who were impacted, and/or apologising for harms done. If you set the bar too high, there’s a risk that you’re engaging in the boycott to satisfy your sense of outrage rather than seeking to make the world a better place. And if the company clears the bar, then you should have good reason to drop the boycott.

Finally, even though a coordinated boycott can be highly effective, be wary of judging others too harshly for their choice to not participate. Different people value different things, and have different budgets regarding how much cost they are willing to bear when considering what they purchase. Informing others about the harms you believe a company is causing is one thing, but browbeating them for not joining a boycott risks tipping over into moralising.

Boycotts can be a powerful tool for change. But they can also be weaponised or implemented hastily or with malicious intent, so we want to ensure we’re making conscious and ethical decisions for the right reasons. We often lament the lack of power that we have individually to make the world a better place. But if there’s one thing that money is good at, it’s sending a message.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why certain things shouldn’t be “owned”

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

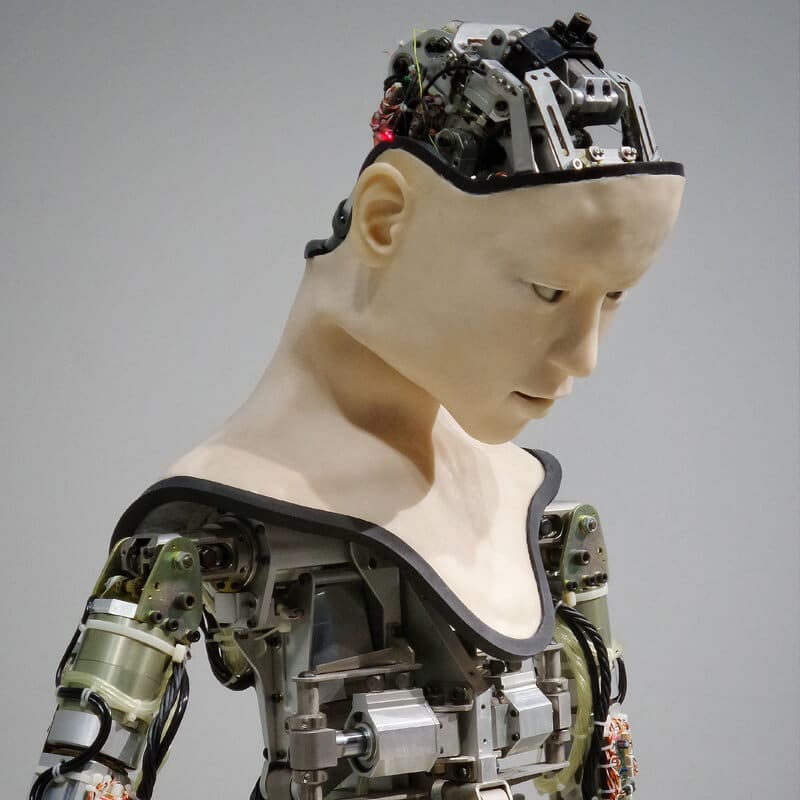

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + Leadership

BY Dia Bianca Lao 24 NOV 2025

“If a human worker does $50,000 worth of work in a factory, that income is taxed. If a robot comes in to do the same thing, you’d think we’d tax the robot at a similar level,” Bill Gates famously said. His call raises an urgent ethical question now facing Australia: When AI replaces human labour, who pays for the social cost?

As AI becomes a cheaper alternative to human labour, the question is no longer if it will dramatically reshape the workforce, but how quickly, and whether the nation’s labour market can adapt in time.

New technology always seems like the stuff of science fiction until its seamless transition from novelty to necessity. Today AI is past its infancy and is now shaping real-world industries. The simultaneous emergence of its diverse use cases and the maturing of automation technology underscores how rapidly it’s evolving, transforming this threat into reality sooner than we think.

Historically, automation tended to focus on routine physical tasks, but today’s frontier extends into cognitive domains. Unlike past innovations that still relied on human oversight, the autonomous nature of emerging technologies threatens to make human labour obsolete with its broader capabilities.

While history shows that technological revolutions have ultimately improved output, productivity, and wages in the long-term, the present wave may prove more disruptive than those before. In 2017, Bill Gates foresaw this looming paradigm shift and famously argued for companies to pay a ‘robot tax’ to moderate the pace at which AI impacts human jobs and help fund other employment types.

Without any formal measures, the costs of AI-driven displacement will likely mostly fall on workers and society, while companies reap the benefits with little accountability.

According to the World Economic Forum, while AI is predicted to create 69 million new jobs, 83 million existing jobs may be phased out by 2027, resulting in a net decrease of 14 million jobs or approximately 2% of current employment. They also projected that 23% of jobs globally will evolve in the next five years, driven by advancements in technology. While the full impact is not yet visible in official employment statistics, the shift toward reducing reliance on human labour through automation and AI is already underway, with entry-level roles and jobs involving logistics, manufacturing, admin, and customer service being the most impacted.

For example, Aurora’s self-driving trucks are officially making regular roundtrips on public roads delivering time- and temperature-sensitive freight in the U.S., while Meituan is making drone deliveries increasingly common in China’s major cities. We now live in a world where you can get your boba milk tea delivered by a drone in less than 20 minutes in places like Shenzhen. Meanwhile in Australia, Rio Tinto has also deployed fully autonomous trains and autonomous haul trucks across its Pilbara iron ore mines, increasing operational time and contributing to a 15% reduction in operating costs.

Companies have already begun recalibrating their workforce, and there is no stopping this train. In the past 12 months, CBA and Bankwest have cut hundreds of jobs across various departments despite rising profits. Forty-five of these roles were replaced by an AI chatbot handling customer queries, while the permanent closure of all Bankwest branches has seen the bank transition to a digital bank, with no intention of bringing back the lost positions. While some argue that redeployment opportunities exist or new jobs might emerge, details remain vague.

Is it possible to fully automate an economy and eliminate the need for jobs? Elon Musk certainly thinks so. It’s no wonder that a growing number of tech elite are investing heavily to replace human labour with AI. From copywriting to coding, AI has proven its versatility in speeding up productivity in all aspects of our lives. Its potential for accelerating innovation, improving living standards and economic growth is unparalleled, but at what cost?

What counts as good for the economy has historically benefited a select few, with technology frequently being a catalyst for this dynamic. For example, the benefits of the Industrial Revolution, including the creation of new industries and increased productivity, were initially concentrated in the hands of those who owned the machinery and capital, while the widespread benefits trickled down later. Without ethical frameworks in place, AI is positioned to compound this inequality.

Some proposals argue that if we make taxes on human labour cheaper while increasing taxes on AI machines and tools, this could encourage companies to view AI as complementary instead of a replacement for human workers. This levy could be a means for governments to distribute AI’s socioeconomic impacts more fairly, potentially funding retraining or income support for displaced workers.

If a robot tax is such a good idea, then why did the European Parliament reject it? Many argue that taxing productivity tools could hinder competitiveness. Without global coordination to implement this, if one country taxes AI and others don’t, it may create an uneven playing field and stifle innovation. How would policymakers even define how companies would qualify for this levy or measure how much to tax, when it’s hard to attribute profits derived from AI? Unlike human workers’ earnings, taxing AI isn’t as straightforward.

The challenge of developing policies that incentivise innovation while ensuring that its benefits and burdens are shared responsibly across society persists. The government’s focus on retraining and upskilling workers to help with this transition is a good start, but they cannot address all the challenges of automation fast enough. Relying solely on these programs risk overlooking structural inequities, such as the disproportionate impact on lower-income or older workers in certain industries, and long-term displacement, where entire job categories may vanish faster than workers can be retrained.

Our fiscal policies should adapt to the evolving economic landscape to help smooth this shift and fund social safety nets. A reduction in human labour’s share in production will significantly impact government revenue unless new measures of taxing capital are introduced.

While a blanket “robot tax” is impractical at this stage, incremental changes to existing taxation policies to target sectors that are most vulnerable to disruption is a possibility. Ideally, policies should distinguish the treatment between technologies that substitute for human labour, and those that complement them, to only disincentivise the former. While this distinction can be challenging, it offers a way to slow down job displacement, giving workers and welfare systems more time to adapt and generate revenue to help with the transition without hindering productivity.

As Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella warns, “With this empowerment comes greater human responsibility — all of us who build, deploy, and use AI have a collective obligation to do so responsibly and safely, so AI evolves in alignment with our social, cultural, and legal norms. We have to take the unintended consequences of any new technology along with all the benefits, and think about them simultaneously.”

The challenge in integrating AI more equitably into the economy is ensuring that its broad societal benefits are amplified, while reducing its unintended negative consequences. AI has the potential to fundamentally accelerate innovation for public good but only if progress is tied to equitable frameworks and its ethical adoption.

Australia already regulates specific harms of AI, protecting privacy and personal information through the Privacy Act 1988 and addressing bias through the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs). These examples show that targeted regulation is possible. However, the next step should include ethical guardrails for AI-driven job displacement, such as exploring more equitable taxation, redistribution policies, and accountability frameworks before it’s too late. This transformation will require joint collaboration from governments, companies, and global organisations to collectively build a resilient and inclusive AI-powered future.

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future by Dia Bianca Lao is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ 2025 Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

BY Dia Bianca Lao

Dia Bianca Lao is a marketer by trade but a writer at heart, with a passion for exploring how ethics, communication, and culture shape society. Through writing, she seeks to make sense of complexity and spark thoughtful dialogue.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Making the tough calls: Decisions in the boardroom

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Ukraine hacktivism

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 4 NOV 2025

We’re thrilled to introduce Aubrey Blanche, our new Director of Ethical Advisory & Strategic Partnerships, who will lead our engagements with organisational partners looking to operate with the highest standards of ethical governance and leadership.

Aubrey is a responsible governance executive with 15 years of impact. An expert in issues of workplace fairness and the ethics of artificial intelligence, her experience spans HR, ESG, communications, and go-to-market strategy. She seeks to question and reimagine the systems that surround us to ensure that all can build a better world. A regular speaker and writer on issues of ethical business, finance, and technology, she has appeared on stages and in media outlets all over the world.

To better understand the work she’ll be doing with The Ethics Centre, we sat down with Aubrey to discuss her views on AI, corporate responsibility, and sustainability.

We’ve seen the proliferation of AI impact the way in which we work. What does responsible AI use look like to you – for both individuals and organisations?

I think that the first step to responsibility in AI is questioning whether we use it at all! While I believe it is and will be a transformative technology, there are major downsides I don’t think we talk about enough. We know that it’s not quite as effective as many people running frontier AI labs aim to make us believe, and it uses an incredible amount of natural resources for what can sometimes be mediocre returns.

Next, I think that to really achieve responsibility we need partnerships between the public and private sector. I think that we need to ensure that we’re applying existing regulation to this technology, whether that’s copyright law in the case of training, consumer protection in the case of chatbots interacting with children, or criminal prosecution regarding deepfake pornography. We also need business leaders to take ethics seriously, and to build safeguards into every stage from design to deployment. We need enterprises to refuse to buy from vendors that can’t show their investments in ensuring their products are safe.

And last, we need civil society to actively participate in incentivising those actors to behave in ways that are of benefit to all of society (not just shareholders or wealthy donors). That means voting for politicians that support policies that support collective wellbeing, boycotting companies complicit in harms, and having conversations within their communities about how these technologies can be used safely.

In a time where public trust is low in businesses, how can they operate fairly and responsibly?

I think the best way that businesses can build responsibility is to be more specific. I think people are tired of hearing “We’re committed to…”. There’s just been too much greenwashing, too much ethics washing, and too many “commitments” to diversity that haven’t been backed up by real investment or progress. The way through that is to define the specific objectives you have in relation to responsibility topics, publish your specific goals, and regularly report on your progress – even if it’s modest.

And most importantly, do this even when trust is low. In a time of disillusionment, you’ll need to have the moral courage to do the right thing even when there is less short-term “credit” for it.

How can we incentivise corporations to take responsible action on environmental issues?

I think that regulation can be a powerful motivator. I’m really excited that the Australian Accounting Standards Board is bringing new requirements into force that, at least for large companies, will force them to proactively manage climate risks and their impacts. While I don’t think it’s the whole answer, a regulatory “push” can be what’s needed for executives to see that actively thinking about climate in the context of their operations can be broadly beneficial to operations.

What are you most excited about sinking your teeth into at The Ethics Centre?

There’s so much to be excited about! But something that I’ve found wildly inspiring is working with our Young Ambassadors – early career professionals in banking and financial services who are working with us to develop their ethical leadership skills. While I have enjoyed working with our members – and have spent the last 15 years working with leaders in various areas of corporate responsibility – there nothing quite like the optimism you get when learning from people who care so much and who show us what future is possible.

Lastly – the big one, what does ethics mean to you?

A former boss of mine once told me that leadership is not about making the right choice when you have one: it’s about making the best choice you can when you have terrible ones and living with that choice. I think in many cases that’s what ethics is. It gives us a framework not to do the right thing when the answer is clear, but to align ourselves as closely as we can with our values and the greater good when our options are messy, complicated, or confusing.

Personally, I’ve spent a deep amount of time thinking about my values, and if I were forced to distill them down to two, I would wholeheartedly choose justice and compassion. I have found that when I consider choices through those frames, I both feel more like myself and like I’ve made choices that are a net good in the world. And I’ve been lucky enough to spend my career in roles where I got to live those values – that’s a privilege I don’t take for granted, and one of the reasons I’m so thrilled to be in this new role with The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

A framework for ethical AI

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is debt learnt behaviour?

Teachers, moral injury and a cry for fierce compassion

Teachers, moral injury and a cry for fierce compassion

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY Lee-Anne Courtney 20 OCT 2025

I first came across the term moral injury during a work break, scrolling through Bond University’s research page, my casual employer at the time.

It sounded vaguely religious and a bit dramatic, and it sparked my curiosity. The article explained that moral injury is a term given to a form of psychological trauma experienced when someone is exposed to events that violate or transgress their deeply held beliefs of right and wrong, leading to biopsychosocial suffering.

First used in relation to military service, moral injury was coined by military psychiatrist Jonathan Shay (2014) when he realised that therapy designed to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) wasn’t effective for all service members. Shay used the term moral injury to describe a deeper wound carried by his patients, not from fear for their physical safety, but from violating their own morals or having them violated by leaders. The suffering experienced from exposure to violence was compounded by the damage to their identity and feeling like they’d lost their worth or goodness in the eyes of society and themselves. Insight into this hidden cost of trauma was an epiphany for me.

I’m a secondary teacher by profession, but I’ve not been employed in the classroom for over 10 years. In fact, I haven’t been employed doing anything other than the occasional casual project since that time. Why? Was it burnout, stress, compassion fatigue, lack of resilience, or the ever-handy catch-all, poor mental health? No matter which explanation I considered, the result was the same: a growing sense of personal failure and creeping doubt about whether I’m cut out for any kind of paid work. Being introduced to the term moral injury was like turning a kaleidoscope; all the same colours tumbled into a dazzlingly different pattern. It gave me a fresh lens through which to view my painful experience of leaving the teaching profession. I needed to know more about moral injury, not only for myself, but also for my colleagues, the students and the profession that I love.

If just a glimpse of moral injury gave me hope that my distress in my role as a teacher wasn’t simply personal failure, imagine the impact a deep, shared understanding could have on our education system and wider community.

Within the month, I had written and submitted a research proposal to empirically investigate the impact of moral injury on teacher wellbeing in Australia.

I discovered moral injury, while well-studied in various workforce populations, had received limited but significant empirical attention in the teaching profession. My research clearly showed that moral injury has a serious negative impact on teachers’ wellbeing and professional function. Crucially, it offered insight into why many teachers were experiencing intense psychological distress and a growing urge to leave the profession, even when poor working conditions and eroding public respect were the subject of policy and practice reform.

What makes an event or situation potentially morally injurious is when it transgresses a deeply held value or belief about what is right or wrong. Research exploring moral injury in the teaching practice suggests that teachers hold shared values and beliefs about what good teaching means. Education researchers such as Thomas Albright, Lisa Gonzalves, Ellis Reid and Meira Levinson affirm that teachers aim to guide all students in gaining knowledge and skills while shaping their thinking and behaviour with an awareness of right and wrong, promoting social justice and challenging injustice. Researcher Yibing Quek highlights the development of respectful, critical thinking as a core educational goal that supports students in navigating life’s challenges. Scholars such as Erin Sugrue, Rachel Briggs, and L. Callid Keef-Perry emphasise that the goals of education are only achievable through relationships rooted in deep care, where teachers are responsive to students’ complex learning and wellbeing needs and attuned to ethical dilemmas requiring both compassion and justice. Though ethical dilemmas are inherent in teaching, researcher Dana Cohen-Lissman argues that many are generated from externally imposed policies, potentially leading to moral injury among teachers.

Studies assert that teachers experience moral injury when systemic barriers and practice arrangements keep them from aligning their actions with their professional identity, educational goals, and core teaching values. Teachers exposed to the shortcomings of education and other systems often feel they are complicit in the harm inflicted on students. Researchers have consistently identified neoliberalism, social and educational inequities, racism, and student trauma as key factors contributing to experiences that lead to moral injury for teachers. These systemic problems place crippling pressure on individual teachers, both in the classroom and in leadership, to achieve the stated goals of education, despite policies that provide insufficient and unevenly distributed resources to do so.

Furthermore, the high-stakes accountability demanded of individual employees fails to recognise the collective, community-oriented, interdependent nature of the work of teaching. The problem is that the gap between what is expected of teachers and what they can do is often blamed on them, and over time, they start to believe it of themselves. Naturally, these morally injurious experiences cause emotional distress, hinder job performance, and gradually erode teachers’ wellbeing and job satisfaction.

Experiencing moral distress, witnessing harm to children, feeling betrayed by policymakers and the public, powerless to make meaningful change, and working without the rewards of service, teachers face difficult choices. They can respond to moral injury by quietly resisting, speaking out to demand understanding and systemic change or take what they believe to be the only ethical choice – leave the profession of teaching. But what if, instead of facing these difficult choices, teachers resorted to reductive moral reasoning – simplifying the complex ethical dilemmas piling up around them or ignoring them altogether – so they wouldn’t be disturbed by them? Numbing ethical sensitivity just to keep a job creates even more problems.

Moral injury goes beyond personal failure or inadequacy; it acknowledges the broader systemic conditions that place teachers in situations where their ethical commitments increasingly clash with the neoliberal forces currently shaping education. Moral injury offers a language of lament, an explanation for the anguish experienced in the practice of teaching. An understanding of moral injury in the education sector invites society, collectively, to offer teachers fierce compassion and moral repair by restructuring the social systems that create these conditions. Adding moral injury to the discourse around teacher shortages may even help teachers offer fierce compassion to themselves. It did for me.

BY Lee-Anne Courtney

Lee-Anne Courtney is a secondary teacher with over 30 years of experience in the education sector. She is conducting PhD research with a team at Bond University aimed at uncovering the impact of moral injury on teacher wellbeing in Australia.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Following a year of scandals, what’s the future for boards?

Big thinker

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

Reports

Business + Leadership

A Guide to Purpose, Values, Principles

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Big thinkerSociety + CultureBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 7 OCT 2025

Ayn Rand (born Alissa Rosenbaum, 1905-1982) was a Russian-born American writer & philosopher best known for her work on Objectivism, a philosophy she called “the virtue of selfishness”.

From a young age, Rand proved to be gifted, and after teaching herself to read at age 6, she decided she wanted to be a fiction writer by age 9.

During her teenage years, she witnessed both the Kerensky Revolution in February of 1917, which saw Tsar Nicholas II removed from power, and the Bolshevik Revolution in October of 1917. The victory of the Communist party brought the confiscation of her father’s pharmacy, driving her family to near starvation and away from their home. These experiences likely laid the groundwork for her contempt for the idea of the collective good.

In 1924, Rand graduated from the University of Petrograd, studying history, literature and philosophy. She was approved for a visa to visit family in the US, and she decided to stay and pursue a career in play and fiction writing, using it as a medium to express her philosophical beliefs.

Objectivism

“My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.” – Appendix of Atlas Shrugged

Rand developed her core philosophical idea of Objectivism, which maintains that there is no greater moral goal than achieving one’s happiness. To achieve this happiness, however, we are required to be rational and logical about the facts of reality, including the facts about our human nature and needs.

Objectivism has four pillars:

- Objective reality – there is a world that exists independent of how we each perceive it

- Direct realism – the only way we can make sense of this objective world is through logic and rationality

- Ethical egoism – an action is morally right if it promotes our own self-interest (rejecting the altruistic beliefs that we should act in the interest of other people)

- Capitalism – a political system that respects the individual rights and interests of the individual person, rather than a collective.

Given her beliefs on individualism and the morality of selfishness, Rand found that the only political system that was compatible was Laissez-Faire Capitalism. Protecting individual freedom with as little regulation and government interference would ensure that people can be rationally selfish.

A person subscribing to Objectivism will make decisions based on what is rational to them, not out of obligation to friends or family or their community. Rand believes that these people end up contributing more to the world around them, because they are more creative, learned, and can challenge the status quo.

Writing

She explored these concepts in her most well-known pieces of fiction: The Fountainhead, published in 1943, and Atlas Shrugged, published in 1957. The Fountainhead follows Howard Roark, an anti-establishment architect who refuses to conform to traditional styles and popular taste. She introduces the reader to the concept of “second-handedness”, which she defines living through others’ and their ideas, rather than through independent thought and reason.

The character Roark personifies Rand’s Objectivist ideals, of rational independence, productivity and integrity. Her magnum opus, Atlas Shrugged, builds on these ideas of rational, selfish, creative individuals as the “prime movers” of a society. Set in a dystopian America, where productivity, creativity, and entrepreneurship stagnate due to over-regulation and an “overly altruistic society”, the novel describes this as disincentivising ambitious, money-driven people.

Even though Atlas Shrugged quickly became a bestseller, its reception was controversial. It has tended to be applauded by conservatives, while dismissed as “silly,’ “rambling” and “philosophically flawed” by liberals.

Controversy

Ayn Rand remains a controversial figure, given her pro-capitalist, individual-centred definition of an ideal society. So much of how we understand ethics is around what we can do for other people and the societies we live in, using various frameworks to understand how we can maximise positive outcomes, or discern the best action. Objectivism turns this on its head, claiming that the best thing we can do for ourselves and the world is act within our own rational self-interest.

“Why do they always teach us that it’s easy and evil to do what we want and that we need discipline to restrain ourselves? It’s the hardest thing in the world–to do what we want. And it takes the greatest kind of courage. I mean, what we really want.”

Rand’s work remains hotly debated and contested, although today it is being read in a vastly different context. Tech billionaires and CEOs such as Peter Thiel and Steve Jobs are said to have used her philosophy as their “guiding stars,” and her work tends to gain traction during times of political and economic instability, such as during the 2008 financial crisis. Ultimately, whether embraced as inspiration or rejected as ideology, Rand’s legacy continues to grapple with the extent to which individual freedom drives a society forward.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Measuring culture and radical transparency

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Is your workplace turning into a cult?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Service for sale: Why privatising public services doesn’t work

Service for sale: Why privatising public services doesn’t work

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY Dr Kathryn MacKay 1 OCT 2025

What do the recent Optus 000-incidents, childcare centre abuse allegations, and the Northern Beaches Hospital deaths have in common?

Each of these incidents plausibly resulted from the privatisation of public services, in which the government has systematically disinvested funds and withdrawn oversight.

On the 18th of September, Optus’ 000 service went down for the second time in two years. This time, the outage affected people in Western Australia, and as a result of not being able to get through to the 000 service, it appears that three people have died.

This highlights a more general issue that we see in Australia across a range of public services, including emergency, hospital, and childcare services. The government has sought to privatise important parts of the care economy that are badly suited to generating private profits, leading to moral and practical problems.

Privatisation of public services

Governments in Australia follow economic strategies that can be described as neoliberal. This means that they prefer limited government intervention and favour market solutions to match the value that people are willing to pay with the value that people want to charge for goods and services.

As a result, public goods and services like healthcare, energy, and telecommunications have been gradually sold off in Australia to private companies. This is because, firstly, it’s not considered within the government’s remit to provide them, and secondly, policy makers think the market will provide more efficient solutions for consumers than the government can.

We see then, for example, a proliferation of energy suppliers popping up, offering the most competitive rates they can for consumers against the real cost of energy production. And we see telecommunications companies, like Telstra and Optus, emerging to compete for consumers in the market of cellular and internet services.

So far, so good. In principle, these systems of competition should drive companies to provide the best possible services for the lowest competitive rates, which would mean real advantages for consumers. Indeed, many have argued that governments can’t provide similar advantages for consumers, given that they end up with no competition and no drive for technical improvements.

However, the picture in reality is not so rosy.

Public services: Some things just can’t be privatised

There’s a term in economics called ‘market failure’. This describes a situation where, for a few different possible reasons, the market fails to efficiently respond to supply and demand flows, affecting the nature of public goods and services.

A classic public good has two features: it is non-rival, and non-excludable. A non-rival good is one where one person’s use doesn’t deplete how much of that good is left for others – so we are not rivals because there is enough for everyone. A non-excludable good is one where my use of it doesn’t prevent anyone else from using it either. So, I can’t claim this good because I’m using it right now; it remains open to others to use.

Consider a jumper. This is a rival and excludable good. If I purchase a jumper out of a stock of jumpers, there are fewer jumpers for you and everyone else who wants one. The jumper is a rival good. When I buy the jumper and wear it, no one else can buy it or wear it; it is an excludable good.

Now, consider the 000 service. In theory, if you and I are both facing an emergency, we can both call 000 and get through to an operator. The 000 service is a non-rival, non-excludable good. It is not the sort of thing that anyone can deplete the stock of, nor can anyone exclude anyone else from using it.

Such goods and services present a problem for the market. Private companies have little reason to provide public goods or services, like roads, street lights, 000 services, clean air, or public health care. That’s because these sorts of goods don’t return them much of a profit. There is little or no reason that anyone would pay to use these services when they can’t be excluded from their use and their stock won’t be depleted. Of course, that has not stopped governments from trying to privatise these things anyway, as we see from toll roads, 000, and private care.

Public goods, private incentives

The primary moral problem that arises in the privatisation of public goods and services is two-fold. First, it puts the provision of important goods and services in the hands of companies whose interests directly oppose the nature of the goods to be provided. Second, people are made vulnerable to an unreliable system of private provision of public goods and services.

A private company’s main objective is to make the most possible profit for shareholders. Given that public goods will not make much of a profit, there is little incentive for a private company to give them attention. This means that essential goods and services, like the 000 service, are deprioritised in favour of those other services that will make the company more of a profit.

Further, people become vulnerable to unreliable service providers, as proper oversight and governance undercuts the profit of private companies. Any time a company has to pay for staff re-training, for revision of protocols, or firing and replacing an employee, they make their profits smaller. So, private companies have incentives to cut corners where they can, and oversight, governance, and quality control seem to be the most frequent things to go.

Most of the time, these cut corners go unnoticed. Until, that is, something goes wrong with the service and people get hurt, or worse.

So why does this system continue?

Successive governments have made the decision to privatise goods and services, making their public expenditures smaller and therefore also making it look like they are being more ‘responsible’ with tax revenues. It’s an attractive look for the neoliberal government, which emphasises how small and non-interventionist it is. But is it working for Australians?

It seems like the government’s quest for a smaller bottom line is at odds with the needs of Australian people. The stable provision of a 000 service, safe hospitals with appropriate oversight, and reliable childcare services with proper governance are all essential goods that Australians want, and which private companies consistently seem unable to provide.

It’s a moral – if not economic – imperative that Australian governments reverse course and begin to provide essential goods and services again. The 000 service, the childcare system, and hospitals provide only a few examples of where the government’s involvement in providing public services is very obviously missing. People are getting hurt, and people are dying, for the sake of private profits.

BY Dr Kathryn MacKay

Kathryn is a Senior Lecturer at Sydney Health Ethics, University of Sydney. Her background is in philosophy and bioethics, and her research involves examining issues of human flourishing at the intersection of ethics, feminist theory and political philosophy. Kathryn’s research is mainly focussed on developing a theory of virtue for public health ethics, and on the ethics of public health communication. Her book Public Health Virtue Ethics is forthcoming with Routledge.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Twitter made me do it!

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Corporate whistleblowing: Balancing moral courage with moral responsibility

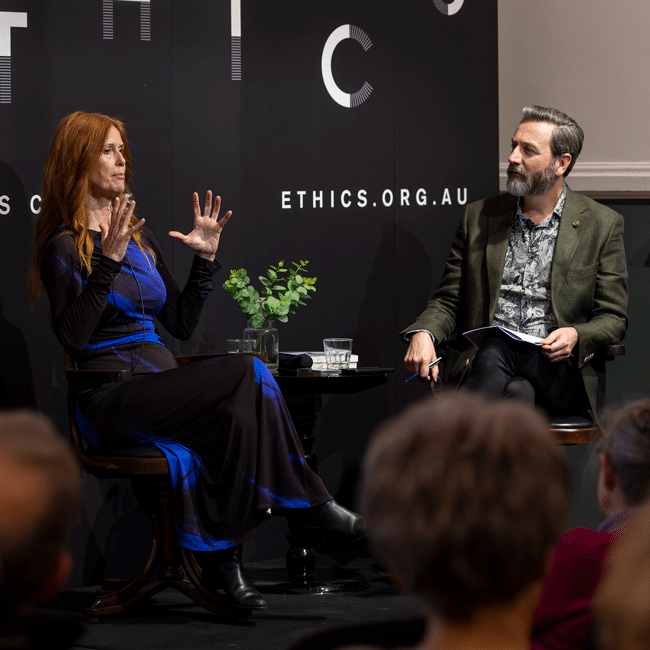

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 17 SEP 2025

As artificial intelligence is becoming increasingly accessible and integrated into our daily lives, what responsibilities do we bear when engaging with and designing this technology? Is it just a tool? Will it take our jobs? In The Ethics of AI, philosopher Dr Tim Dean and global ethicist and trailblazer in AI, Dr Catriona Wallace, sat down to explore the ethical challenges posed by this rapidly evolving technology and its costs on both a global and personal level.

Missed the session? No worries, we’ve got you covered. Here are 3 things we learnt from the event, The Ethics of AI:

We need to think about AI in a way we haven’t thought about other tools or technology

In 2023, The CEO of Google, Sundar Pichai described AI as more important than the invention of fire, claiming it even surpassed great leaps in technology such as electricity. Catriona takes this further, calling AI “a new species”, because “we don’t really know where it’s all going”.

So is AI just another tool, or an entirely new entity?

When AI is designed, it’s programmed with algorithms and fed with data. But as Catriona explains, AI begins to mirror users’ inputs and make autonomous decisions – often in ways even the original coders can’t fully explain.

Tim points out that we tend to think of technology instrumentally, as a value neutral tool at our disposal. But drawing from German philosopher Martin Heidegger, he reminds us that we’re already underthinking tools and what they can do – tools have affordances, they shape our environment and steer our behaviour. So “when we add in this idea of agency and intentionality” Tim says, “it’s no longer the fusion of you and the tool having intentionality – the tool itself might have its own intentions, goals and interests”.

AI will force us to reevaluate our relationship with work

The 2025 Future of Jobs Report from The World Economic Forum estimates that by 2030, AI will replace 92 million current jobs but 170 million new jobs will be created. While we’ve already seen this kind of displacement during technological revolutions, Catriona warns that the unemployed workers most likely won’t be retrained into the new roles.

“We’re looking at mass unemployment for front line entry-level positions which is a real problem.”

A universal basic income might be necessary to alleviate the effects of automation-driven unemployment.

So if we all were to receive a foundational payment, what does the world look like when we’re liberated from work? Since many of us tie our identity to our jobs and what we do, who are we if we find fulfilment in other types of meaning?

Tim explains, “work is often viewed as paid employment, and we know – particularly women – that not all work is paid, recognised or acknowledged. Anyone who has a hobby knows that some work can be deeply meaningful, particularly if you have no expectation of being paid”.

Catriona agrees, “done well, AI could free us from the tie to labour that we’ve had for so long, and allow a freedom for leisure, philosophy, art, creativity, supporting others, caring for loving, and connection to nature”.

Tech companies have a responsibility to embed human-centred values at their core

From harmful health advice to fabricating vital information, the implications of AI hallucinations have been widely reported.

The Responsible AI Index reveals a huge disconnect between businesses leaders’ understanding of AI ethics, with only 30% of organisations knowing how to implement ethical and responsible AI. Catriona explains this is a problem because “if we can’t create an AI agent or tool that is always going to make ethical recommendations, then when an AI tool makes a decision, there will always be somebody who’s held accountable”.

She points out that within organisations, executives, investors, and directors often don’t understand ethics deeply and pass decision making down to engineers and coders — who then have to draw the ethical lines. “It can’t just be a top-down approach; we have to be training everybody in the organisation.”

So what can businesses do?

AI must be carefully designed with purpose, developed to be ethical and regulated responsibly. The Ethics Centre’s Ethical by Design framework can guide the development of any kind of technology to ensure it conforms to essential ethical standards. This framework can be used by those developing AI, by governments to guide AI regulation, and by the general public as a benchmark to assess whether AI conforms to the ethical standards they have every right to expect.

The Ethics of AI can be streamed On Demand until 25 September, book your ticket here. For a deeper dive into AI, visit our range of articles here.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Georg Kell on climate and misinformation

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + Leadership

BY Daniel Finlay 8 SEP 2025

My workplace is starting to implement AI usage in a lot of ways. I’ve heard so many mixed messages about how good or bad it is. I don’t know whether I should use it, or to what extent. What should I do?

Artificial intelligence (AI) is quickly becoming unavoidable in our daily lives. Google something, and you’ll be met with an “AI overview” before you’re able to read the first result. Open up almost any social media platform and you’ll be met with an AI chat bot or prompted to use their proprietary AI to help you write your message or create an image.

Unsurprisingly, this ubiquity has rapidly extended to the workplace. So, what do you do if AI tools are becoming the norm but you’re not sure how you feel about it? Maybe you’re part of the 36% of Australians who aren’t sure if the benefits of AI outweigh the harms. Luckily, there’s a few ethical frameworks to help guide your reasoning.

Outcomes

A lot of people care about what AI is going to do for them, or conversely how it will harm them or those they care about. Consequentialism is a framework that tells us to think about ethics in terms of outcomes – often the outcomes of our actions, but really there are lots of types of consequentialism.

Some tell us to care about the outcomes of rules we make, beliefs or attitudes we hold, habits we develop or preferences we have (or all of the above!). The common thread is the idea that we should base our ethics around trying to make good things happen.

This might seem simple enough, but ethics is rarely simple.

AI usage is having and is likely to have many different competing consequences, short and long-term, direct and indirect.

Say your workplace is starting to use AI tools. Maybe they’re using email and document summaries, or using AI to create images, or using ChatGPT like they would use Google. Should you follow suit?

If you look at the direct consequences, you might decide yes. Plenty of AI tools give you an edge in the workplace or give businesses a leg up over others. Being able to analyse data more quickly, get assistance writing a document or generate images out of thin air has a pretty big impact on our quality of life at work.

On the other hand, there are some potentially serious direct consequences of relying on AI too. Most public large language model (LLM) chatbots have had countless issues with hallucinations. This is the phenomenon where AI perceives patterns that cause it to confidently produce false or inaccurate information. Given how anthropomorphised chatbots are, which lends them an even higher degree of our confidence and trust, these hallucinations can be very damaging to people on both a personal and business level.

Indirect consequences need to be considered too. The exponential increase in AI use, particularly LLM generative AI like ChatGPT, threatens to undo the work of climate change solutions by more than doubling our electricity needs, increasing our water footprint, greenhouse gas emissions and putting unneeded pressure on the transition to renewable energy. This energy usage is predicted to double or triple again over the next few years.

How would you weigh up those consequences against the personal consequences for yourself or your work?

Rights and responsibilities

A different way of looking at things, that can often help us bridge the gap between comparing different sets of consequences, is deontology. This is an ethical framework that focuses on rights (ways we should be treated) and duties (ways we should treat others).

One of the major challenges that generative AI has brought to the fore is how to protect creative rights while still being able to innovate this technology on a large scale. AI isn’t capable of creating ‘new’ things in the same way that humans can use their personal experiences to shape their creations. Generative AI is ‘trained’ by giving the models access to trillions of data points. In the case of generative AI, these data points are real people’s writing, artwork, music, etc. OpenAI (creator of ChatGPT) has explicitly said that it would be impossible to create these tools without the access to and use of copyrighted material.

In 2023, the Writers Guild of America went on a five-month strike to secure better pay and protections against the exploitation of their material in AI model training and subsequent job replacement or pay decreases. In 2025, Anthropic settled for $1.5 billion in a lawsuit over their illegal piracy of over 500,000 books used to train their AI model.

Creative rights present a fundamental challenge to the ethics of using generative AI, especially at work. The ability to create imagery for free or at a very low cost with AI means businesses now have the choice to sidestep hiring or commissioning real artists – an especially fraught decision point if the imagery is being used with a profit motive, as it is arguably being made with the labour of hundreds or thousands of uncompensated artists.

What kind of person do you want to be?

Maybe you’re not in an office, though. Maybe your work is in a lab or field research, where AI tools are being used to do things like speed up the development of life-changing drugs or enable better climate change solutions.

Intuitively, these uses might feel more ethically salient, and a virtue ethics point of view could help make sense of that. Virtue ethics is about finding the valuable middle ground between extreme sets of characteristics – the virtues that a good person, or the best version of yourself, would embody.

On the one hand, it’s easy to see how this framework would encourage use of AI that helps others. A strong sense of purpose, altruism, compassion, care, justice – these are all virtues that can be lived out by using AI to make life-changing developments in science and medicine for the benefit of society.

On the other hand, generative AI puts another spanner in the works. There is an increasing body of research looking at the negative effects of generative AI on our ability to think critically. Overreliance and overconfidence in AI chatbots can lead to the erosion of critical thinking, problem solving and independent decision making skills. With this in mind, virtue ethics could also lead us to be wary of the way that we use particular kinds of AI, lest we become intellectually lazy or incompetent.

The devil in the detail

AI, in all its various capacities, is revolutionising the way we work and is clearly here to stay. Whether you opt in or not is hopefully still up to you in your workplace, but using a few different ethical frameworks, you can prioritise your values and principles and decide whether and what type of AI usage feels right to you and your purpose.

Whether you’re looking at the short and long-term impacts of frequent AI chatbot usage, the rights people have to their intellectual property, the good you can do with AI tools or the type of person you want to be, maintaining a level of critical reflection is integral to making your decision ethical.

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

An ethical dilemma for accountants

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is employee surveillance creepy or clever?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Following a year of scandals, what’s the future for boards?

Explainer

Science + Technology

Thought experiment: “Chinese room” argument

AI and rediscovering our humanity

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 2 SEP 2025

With each passing day, advances in artificial intelligence (AI) bring us closer to a world of general automation.

In many cases, this will be the realisation of utopian dreams that stretch back millennia – imagined worlds, like the Garden of Eden, in which all of humanity’s needs are provided for without reliance on the ‘sweat of our brows’. Indeed, it was with the explicit hope that humans would recover our dominion over nature that, in 1620, Sir Francis Bacon published his Novum Organum. It was here that Bacon laid the foundations for modern science – the fountainhead of AI, robotics and a stack of related technologies that are set to revolutionise the way we live.

It is easy to underestimate the impact that AI will have on the way people will work and live in societies able to afford its services. Since the Industrial Revolution, there has been a tendency to make humans accommodate the demands of industry. In many cases, this has led to people being treated as just another ‘resource’ to be deployed in service of profitable enterprise – often regarded as little more than ‘cogs in the machine’. In turn, this has prompted an affirmation of the ‘dignity of labour’, the rise of Labor unions and with the extension of the voting franchise in liberal democracies, to legislation regulating working hours, standards of safety, etc. Even so, in an economy that relies on humans to provide the majority of labour required to drive a productive economy, too much work still exposes people to dirt, danger and mind-numbing drudgery.

We should celebrate the reassignment of such work to machines that cannot ‘suffer’ as we do. However, the economic drivers behind the widescale adoption of AI will not stop at alleviating human suffering arising out of burdensome employment. The pressing need for greater efficiency and effectiveness will also lead to a wholesale displacement of people from any task that can be done better by an expert system. Many of those tasks have been well-remunerated, ‘white collar’ jobs in professions and industries like banking, insurance, and so on. So, the change to come will probably have an even larger effect on the middle class rather than working class people. And that will be a very significant challenge to liberal democracies around the world.

Change to the extent I foresee, does not need to be a source of disquiet. With effective planning and broad community engagement, it should be possible to use increasingly powerful technologies in a constructive manner that is for the common good. However, to achieve this, I think we will need to rediscover what is unique about the human condition. That is, what is it that cannot be done by a machine – no matter how sophisticated? It is beyond the scope of this article to offer a comprehensive answer to this question. However, I can offer a starting point by way of an example.

As things stand today, AI can diagnose the presence of some cancers with a speed and effectiveness that exceeds anything that can be done by a human doctor. In fact, radiologists, pathologists, etc are amongst the earliest of those who will be made redundant by the application of expert systems. However, what AI cannot do replace a human when it comes to conveying to a patient news of an illness. This is because the consoling touch of a doctor has a special meaning due to the doctor knowing what it means to be mortal. A machine might be able to offer a convincing simulation of such understanding – but it cannot really know. That is because the machine inhabits a digital world whereas we humans are wholly analogue. No matter how close a digital approximation of the analogue might be, it is never complete. So, one obvious place where humans might retain their edge is in the area of personal care – where the performance of even an apparently routine function might take on special meaning precisely because another human has chosen to care. Something as simple as a touch, a smile, or the willingness to listen could be transformative.

Moving from the profound to the apparently trivial, more generally one can imagine a growing preference for things that bear the mark of their human maker. For example, such preferences are revealed in purchases of goods made by artisanal brewers, bakers, etc. Even the humble potato has been affected by this trend – as evidenced by the rise of the ‘hand-cut chip’.

In order to ‘unlock’ latent human potential, we may need to make a much sharper distinction between ‘work’ and ‘jobs’.

That is, there may be a considerable amount of work that people can do – even if there are very few opportunities to be employed in a job for that purpose. This is not an unfamiliar state of affairs. For many centuries, people (usually women) have performed the work of child-rearing without being employed to do so. Elders and artists, in diverse communities, have done the work of sustaining culture – without their doing so being part of a ‘job’ in any traditional sense. The need for a ‘job’ is not so that we can engage in meaningful work. Rather, jobs are needed primarily in order to earn the income we need to go about our lives.

And this gives rise to what may turn out to be the greatest challenge posed by the widescale adoption of AI. How, as a society, will we fund the work that only humans can do once the vast majority of jobs are being done by machines?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Corporate tax avoidance: you pay, why won’t they?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Economic reform must start with ethics

Our regulators are set up to fail by design

Our regulators are set up to fail by design

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker 25 AUG 2025

Our society is built on trust. Most of the time, we trust institutions and the government to do what they say they will. But when they break that trust – by not keeping their promises or acting unfairly – that’s when things start to fall apart. The system stops working for the people it’s supposed to serve.

As a result, we trust regulators to protect the things that matter in our society most. Whether it’s holding institutions to account, or ensuring our food, water and transport are safe, a regulator’s role is to ensure society’s safety net.

But when something goes wrong, the finger usually points straight at the regulator. And while it’s tempting to blame regulators about why things have failed, new policy research from former Chairman of ASIC, James Shipton, suggests we’re asking the wrong question.

The real issue isn’t just who’s doing the job, it’s how the whole system is built.

Shipton is working towards optimising regulation by improving regulatory design, strategy and governance. As a Fellow of The Ethics Centre, he has engaged with industry to develop a better understanding of regulators and the regulated. This work aims to crystalise the purpose of regulation and create a pathway where that purpose is most likely to be achieved.

Shipton’s paper, The Regulatory State: Faults, Flaws and False Assumptions, takes the entire regulatory system in Australia into account. His core message is simple but urgent: our regulators are set up to fail by design.

Right now, most regulators operate in a system that lacks clear direction, support, and accountability. Many don’t have a clearly defined purpose in law. That means the people enforcing the rules aren’t always sure what they’re meant to achieve.

This confusion creates a dangerous “expectations gap” where the public thinks regulators are responsible for outcomes they were never actually empowered to deliver. When regulators fall short, they wear the blame, even when the system itself is broken.

Shipton identifies twelve major flaws in our regulatory system and while they might sound technical, they have real-world consequences. He starts with the concept that our regulators are monopolies by design. Each regulator is the only body responsible for its area – there’s no competition, no pressure to innovate, and very little incentive to improve. In the private sector, companies that fail lose customers and reputations, and customers are free to go elsewhere. In regulation, there’s no alternative.

The heart of Shipton’s argument is this: credibility is key. It’s not enough for a regulator to have legal authority, they need public trust. And that trust only comes when the system they work within is built for clarity, accountability, and ethical responsibility.

For example, in aviation, everyone from pilots to engineers shares a common goal: safety. The whole sector becomes a partner in regulation. But in most industries, that kind of alignment doesn’t exist, often because the system hasn’t been designed to make it happen.

Shipton stresses that design matters. Regulators need clear goals, realistic expectations, regular performance reviews, and laws that actually match the industries they oversee. We don’t need another inquiry into regulatory failure. We need to ask why failure keeps happening in the first place. And the answer, Shipton says, is clear: the entire regulatory architecture in Australia needs redesigning from the ground up.

This doesn’t mean tearing everything down. It means recognising that public trust is earned through structure. It means giving regulators the tools, support, and clarity they need to do their job well and making sure they’re accountable for how they use that power.

If we want fairness, safety, and integrity in the things that matter most, we need a regulatory system we can trust. And as Shipton makes clear, trust starts with design.

James Shipton is a Senior Fellow, Melbourne Law School, The University of Melbourne, Fellow, The Ethics Centre, and Visiting Senior Practitioner, Commercial Law Centre, the University of Oxford.

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to deal with an ethical crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The truth isn’t in the numbers

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights