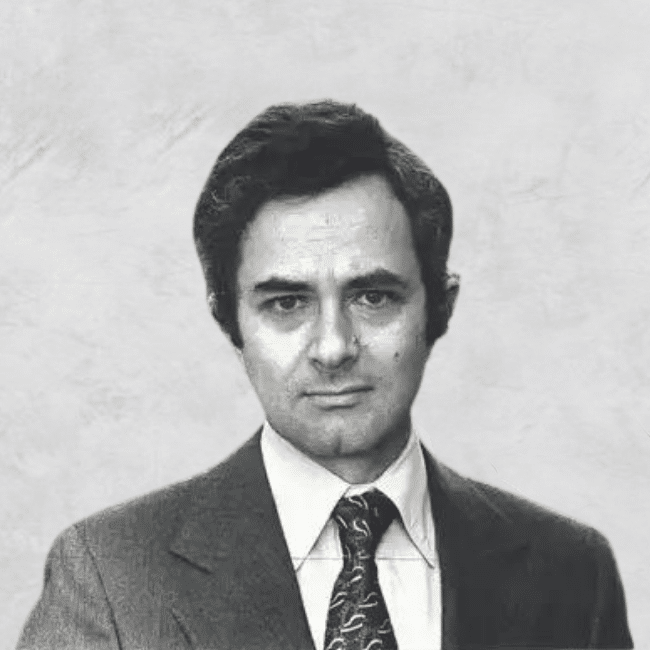

Big Thinker: David Hume

There are few philosophers whose work has ranged over such vast territory as David Hume (1711—1776).

If you’ve ever felt underappreciated in your time, let the story of David Hume console you: despite being one of the most original and profound thinkers of his or any era, the Scottish philosopher never held an academic post. Indeed, he described his magnum opus, A Treatise of Human Nature, as falling “stillborn from the press.” When he was recognized at all during his lifetime, it was primarily as a historian – his multi-volume work on the history of the British monarchy was heralded in France, while in his native country, he was branded a heretic and a pariah for his atheistic views.

Yet, in the many years since his passing, Hume has been retroactively recognised as one the most important writers of the Early Modern era. His works, which touch on everything from ethics, religion, metaphysics, economics, politics and history, continue to inspire fierce debate and admiration in equal measure. It’s not hard to see why. The years haven’t cooled off the bracing inventiveness of Hume’s writing one bit – he is as frenetic, wide-ranging and profound as he ever was.

Empathy

The foundation of Hume’s ethical system is his emphasis on empathy, sometimes referred to as “fellow-feeling” in his writing. Hume believed that we are constantly being shaped and influenced by those around us, via both an imaginative, perspective-taking form of empathy – putting ourselves in other’s shoes – and a “mechanical” form of empathy, now called emotional contagion.

Ever walked into a room of laughing people and found yourself smiling, even though you don’t know what’s being laughed at? That’s emotional contagion, a means by which we unconsciously pick up on the emotional states of those around us.

Hume emphasised these forms of fellow-feeling as the means by which we navigate our surroundings and make ethical decisions. No individual is disconnected from the world – no one is able to move through life without the emotional states of their friends, lovers, family members and even strangers getting under their skin. So, when we act, it is rarely in a self-interested manner – we are too tied up with others to ever behave in a way that serves only ourselves.

The Nature of the Self

Hume is also known for his controversial views on the self. For Hume, there is no stable, internalised marker of identity – no unchanging “me”. When Hume tried to search inside himself for the steady and constant “David Hume” he had heard so much about, he found only sensations – the feeling of being too hot, of being hungry. The sense of self that others seemed so certain of seemed utterly artificial to him, a tool of mental processing that could just as easily be dispatched.

Hume was no fool – he knew that agents have “character traits” and often behave in dependable ways. We all have that funny friend who reliably cracks a joke, the morose friend who sees the worst in everything. But Hume didn’t think that these character traits were evidence of stable identities. He considered them more like trends, habits towards certain behaviours formed over the course of a lifetime.

Such a view had profound impacts on Hume’s ethics, and fell in line with his arguments concerning empathy. After all, if there is no self – if the line between you and I is much blurrier than either of us initially imagined – then what could be seen as selfish behaviours actually become selfless ones. Doing something for you also means doing something for me, and vice versa.

On Hume’s view, we are much less autonomous, sure, forever buffeted around by a world of agents whose emotional states we can’t help but catch, no sense of stable identity to fall back on. But we’re also closer to others; more tied up in a complex social web of relationships, changing every day.

Moral Motivation

Prior to Hume, the most common picture of moral motivation – one initially drawn by Plato – was of rationality as a carriage driver, whipping and controlling the horses of desire. According to this picture, we act after we decide what is logical, and our desires then fall into place – we think through our problems, rather than feeling through them.

Hume, by contrast, argued that the inverse was true. In his ethical system, it is desire that drives the carriage, and logic is its servant. We are only ever motivated by these irrational appetites, Hume tells us – we are victims of our wants, not of our mind at its most rational.

Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.

At the time, this was seen as a shocking inversion. But much of modern psychology bears Hume out. Consider the work of Sigmund Freud, who understood human behaviour as guided by a roiling and uncontrollable id. Or consider the situation where you know the “right” thing to do, but act in a way inconsistent with that rational belief – hating a successful friend and acting to sabotage them, even when on some level you understand that jealousy is ugly.

There are some who might find Hume’s ethics somewhat depressing. After all, it is not pleasant to imagine yourself as little more than a constantly changing series of emotions, many of which you catch from others – and often without even wanting to. But there is great beauty to be found in his ethical system too. Hume believed he lived in a world in which human beings are not isolated, but deeply bound up with each other, driven by their desires and acting in ways that profoundly affect even total strangers.

Given we are so often told our world is only growing more disconnected, belief in the possibility to shape those around you – and therefore the world – has a certain beauty all of its own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Send in the clowns: The ethics of comedy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Are there any powerful swear words left?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The self and the other: Squid Game's ultimate choice

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 25 NOV 2021

In the world of Netflix’s smash hit Squid Game, a collection of desperate people must make a terrible choice: they can either keep living their lives, which are filled with debt and suffering, or they can submit to the titular competition, a series of contests based on children’s games. If they win these contests, their debts will be absolved. If they lose, they will die.

*Spoiler warning for Squid Game

The Australian philosopher Peter Singer would call this an “ultimate choice.” Although on the surface, it is a decision as to whether or not to live with debt, in a much deeper sense, it’s a decision about how to live. The very foundational beliefs of Squid Game’s frantic characters are being challenged. What matters to these people? What do they want out of life? And, just as importantly, how far will they go to get it?

The State of Nature

Squid Game depicts a world of pure barbarism: guided by their desperation, its characters form alliances only when it is mutually beneficial to them, and are often as quick to betray one another. In episode three, for instance, Sang-woo uses insider knowledge of the next contest to get himself ahead, concealing from his supposed allies that he is already aware of what is about to occur.

True acts of kindness sometimes flash through like fish glimpsed at the bottom of a river – consider Hwang Jun-ho, whose participation in the world of Squid Game is guided by the love of his brother – but such moments of empathy are few and far between.

The depiction of such a blood-thirsty, self-interested world is one the philosopher Thomas Hobbes played upon in his construction of the “state of nature.” According to Hobbes, human beings who exist in this state live in a way that is “nasty, brutish, and short.” In such a primal state, one without government, there is no centralised means of understanding or enforcing what is right and wrong, and self-interest is the name of the game.

“So long a man is in the condition of mere nature, (which is a condition of war,)” Hobbes wrote, “private appetite is the measure of good and evil.”

Hobbes believed that the only way to avoid this state of nature was to submit to a governing force – to hand oneself over to a power that could create and enforce a set of rules, known as the social contract. The world of Squid Game contains such a governing force, the shadowy world of the VIPs, who run the games for their own amusement.

But rather than guiding the games’ participants out of the state of nature, the VIPs further deepen and enforce it. The rules that they develop are explicitly designed to keep the desperate players in a world of confusion and barbarism, where self-interest is rewarded, and chaos is the name of the game. The lives of the participants are nasty, brutish, and short, and their spurning of ethics in favour of desperate attempts to get ahead is actively rewarded by a system that runs, above all else, on violence.

The suspension of the moral code

This system, vicious as it is, pushes ordinary people to extraordinary lengths. The characters of Squid Game are, for the most part, simply and vividly drawn – they are defined above all else by their desire to absolve their debts and live freely. That one desire is all it takes for them to suspend the usual moral code that most of us live by, and to act in frequently horrific ways.

Even Sang-Woo, one of the more honorable characters in the show, ends up making deeply immoral choices, culminating in his decision to hurl the glassmaker off a platform in a final act of desperation. He has no stable set of ethics – his code is shaped by a system that thrives on horror and pushes human beings to consider their fellow brethren as little more than tools to be used and discarded at whim.

In this way, Squid Game offers a gleefully cruel riposte to the notion of virtue ethics. Its characters do not act in consistent, moral ways, as virtue ethics imagines that agents do. Although it takes a combination of financial ruin and a system deliberately designed to sow mistrust and horror for them to abandon their usual moral principles, it still brings up some uncomfortable questions about how easily we might abandon our ethics in the real world.

With a kind of horrifying elegance, the show also reveals just how fragile our notion of solidarity can be. We might want to believe that there are bonds between ourselves and even total strangers that cannot be broken – a kind of communal well-spring of trust that stops abject violence from breaking out. But dangle the mere proposition of a debt-free life in front of people willing to do anything to save themselves and their families, and this sense of community breaks horribly down. The show’s participants are alienated not only from their own moral code, but from each other. They are strangers in the deepest sense of the term, the simple, child-like games of the show’s title obliterating any sense of shared humanity.

But can these participants be blamed for their actions? Derek Parfit, the English philosopher, would argue not. It was he who developed the notion of “blameless immorality”, conditions under which people can be forced into vicious actions for which they are not culpable. The heroes of Squid Game are propping up a system that perpetuates further horror, certainly, but their autonomy has been radically diminished. They are little more than puppets, guided by powers outside of their control, their actions no longer their own.

Ethics Versus Self-Interest: The False Choice

Squid Game rests on the principle that self-interest and ethics are at loggerheads with one another – that choosing to do good for others leads necessarily to a sacrifice for oneself. Yet, it’s worth analysing this supposed dichotomy between self-interest and a good, ethical life.

Certainly, the notion that helping others requires us to sacrifice something for ourselves is an old, pervasive myth – it’s why we can view do-gooders as suckers, wasting time on the help of others instead of getting ahead. As Singer notes, such a view was particularly prevalent in the ‘80s with the rise of Wall Street, a world where duping the market – and even your supposed friends – had considerable benefits.

Act immorally – lie, cheat and steal – and you too could become a power player, with more wealth than you dreamed of.

But is there really such a distinction between being self-interested and acting ethically? Could it not be that this is merely an old capitalist myth, designed to perpetuate a system that thrives on “othering” and isolation? After all, viewing our interests as separate from those around us requires us to believe that we are sealed off from the social world, that there is some kind of line to be drawn between behaviours that are meaningfully “ours” and those that belong to others.

In actual fact, it is worth moving away from such an individualist notion of the self, and towards a more communal one. As it happens, the characters of Squid Game are actively hurt by the ways that they are forced to view themselves as alienated from their fellow competitors. It benefits only the show’s mysterious villains, explicitly capitalist and murderous sociopaths, for the heroes of Squid Game to believe in the line between what will help them, and what will help their friends. When, in the penultimate episode, Gi-hun suggests to Sae-byeok that they team up against Sang-Woo, Gi-hun makes the fatal mistake of believing that she has anything to gain through Sang-Woo’s misfortunes.

Such a move away from individuation is not easy. Indeed, Squid Game has a breathtaking nihilism to it –there is no easy way for the characters to escape this deep alienation from one another. The system does not permit it. In the words of Audre Lorde:

“…the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

As philosopher Mark Fisher once wrote in his explication of capitalist realism (the notion that capitalism has pervaded every aspect of human life and is now essentially inescapable), even the ways in which Squid Game’s doomed characters attempt to overthrow their bonds are subsumed as part of those very bonds themselves.

Just as anti-capitalism becomes tainted by capitalism, the means of overthrowing the system sold as one more product, the characters of Squid Game have no recourse by which to escape the individuation that they are fatally trapped in. Their very attempts to connect with one another are undermined by the rules of each game, like the marble game, where voluntarily made pairs are then forced to kill each other.

Squid Game is thus a word of warning. In its terror and violence, it is a reminder to always strive for community, away from individuation and towards a system in which we see fellow agents as more alike us than not. Hope might not be possible for the show’s protagonists, whose very rebellion is neutered at every turn. But, if we resist the moral alienation and deep individuation thrust upon us by capitalism, it might be possible for us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 22 NOV 2021

Autonomy is the capacity to form beliefs and desires that are authentic and in our best interests, and then act on them.

What is it that makes a person autonomous? Intuitively, it feels like a person with a gun held to their head is likely to have less autonomy than a person enjoying a meandering walk, peacefully making a choice between the coastal track or the inland trail. But what exactly are the conditions which determine someone’s autonomy?

Is autonomy just a measure of how free a person is to make choices? How might a person’s upbringing influence their autonomy, and their subsequent capacity to act freely? Exploring the concept of autonomy can help us better understand the decisions people make, especially those we might disagree with.

The definition debate

Autonomy, broadly speaking, refers to a person’s capacity to adequately self-govern their beliefs and actions. All people are in some way influenced by powers outside of themselves, through laws, their upbringing, and other influences. Philosophers aim to distinguish the degree to which various conditions impact our understanding of someone’s autonomy.

There remain many competing theories of autonomy.

These debates are relevant to a whole host of important social concerns that hinge on someone’s independent decision-making capability. This often results in people using autonomy as a means of justifying or rebuking particular behaviours. For example, “Her boss made her do it, so I don’t blame her” and “She is capable of leaving her boyfriend, so it’s her decision to keep suffering the abuse” are both statements that indirectly assess the autonomy of the subject in question.

In the first case, an employee is deemed to lack the autonomy to do otherwise and is therefore taken to not be blameworthy. In the latter case, the opposite conclusion is reached. In both, an assessment of the subject’s relative autonomy determines how their actions are evaluated by an onlooker.

Autonomy often appears to be synonymous with freedom, but the two concepts come apart in important ways.

Autonomy and freedom

There are numerous accounts of both concepts, so in some cases there is overlap, but for the most part autonomy and freedom can be distinguished.

Freedom tends to broader and more overt. It usually speaks to constraints on our ability to act on our desires. This is sometimes also referred to as negative freedom. Autonomy speaks to the independence and authenticity of the desires themselves, which directly inform the acts that we choose to take. This is has lots in common with positive freedom.

For example, we can imagine a person who has the freedom to vote for any party in an election, but was raised and surrounded solely by passionate social conservatives. As a member of a liberal democracy, they have the freedom to vote differently from the rest of their family and friends, but they have never felt comfortable researching other political viewpoints, and greatly fear social rejection.

If autonomy is the capacity a person has to self-govern their beliefs and decisions, this voter’s capacity to self-govern would be considered limited or undermined (to some degree) by social, cultural and psychological factors.

Relational theories of autonomy focus on the ways we relate to others and how they can affect our self-conceptions and ability to deliberate and reason independently.

Relational theories of autonomy were originally proposed by feminist philosophers, aiming to provide a less individualistic way of thinking about autonomy. In the above case, the voter is taken to lack autonomy due to their limited exposure to differing perspectives and fear of ostracism. In other words, the way they relate to people around them has limited their capacity to reflect on their own beliefs, values and principles.

One relational approach to autonomy focuses on this capacity for internal reflection. This approach is part of what is known as the ‘procedural theory of relational autonomy’. If the woman in the abusive relationship is capable of critical reflection, she is thought to be autonomous regardless of her decision.

However, competing theories of autonomy argue that this capacity isn’t enough. These theories say that there are a range of external factors that can shape, warp and limit our decision-making abilities, and failing to take these into account is failing to fully grasp autonomy. These factors can include things like upbringing, indoctrination, lack of diverse experiences, poor mental health, addiction, etc., which all affect the independence of our desires in various ways.

Critics of this view might argue that a conception of autonomy is that is broad makes it difficult to determine whether a person is blameworthy or culpable for their actions, as no individual remains untouched by social and cultural influences. Given this, some philosophers reject the idea that we need to determine the particular conditions which render a person’s actions truly ‘their own’.

Maybe autonomy is best thought of as merely one important part of a larger picture. Establishing a more comprehensively equitable society could lessen the pressure on debates around what is required for autonomous action. Doing so might allow for a broadening of the debate, focusing instead on whether particular choices are compatible with the maintenance of desirable societies, rather than tirelessly examining whether or not the choices a person makes are wholly their own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We can help older Australians by asking them for help

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Lying is something we’ve all done at some point and we tend to take its meaning for granted, but what are we really doing when we lie, and is it ever okay?

A person lies when they:

- knowingly communicate something false

- purposely communicate it as if it was true

- do so with an intention to deceive.

The intention to deceive is an essential component of lying. Take a comedian, for example – they might intentionally present a made-up story as true when telling a joke, engaging in satire, etc. However, the comedian’s purpose is not to deceive but to entertain.

Lying should be distinguished from other deviations from the truth like:

- Falsehoods – false claims we make while believing what we say to be true

- Equivocations – the use of ambiguous language that allows a person to persist in holding a false belief.

While these are different to lying, they can be equally problematic. Accidentally communicating false information can still result in disastrous consequences. People in positions of power (e.g., government ministers) have an obligation to inform themselves about matters under their control or influence and to minimise the spread of falsehoods. Having a disregard for accuracy, while it is not lying, should be considered wrong – especially when as a result of negligence or indifference.

The same can be said of equivocation. The intention is still there, but the quality of exchange is different. Some might argue that purposeful equivocation is akin to “lying by omission”, where you don’t actively tell a lie, but instead simply choose not to correct someone else’s misunderstanding.

Despite lying being fairly common, most of our lives are structured around the belief that people typically don’t do it.

We believe our friends when we ask them the time, we believe meteorologists when they tell us the weather, we believe what doctors say about our health. There are exceptions, of course, but for the most part we assume people aren’t lying. If we didn’t, we’d spend half our days trying to verify what everyone says!

In some cases, our assumption of honesty is especially important. Democracies, for example, only function legitimately when the government has the consent of its citizens. This consent needs to be:

- free (not coerced)

- prior (given before the event needing consent)

- informed (based on true and accessible information)

Crucially, informed consent can’t be given if politicians lie in any aspects of their governance.

So, when is lying okay? Can it be justified?

Some philosophers, notably Immanuel Kant, argue that lying is always wrong – regardless of the consequences. Kant’s position rests on something called the “categorical imperative”, which views lying as immoral because:

- it would be fundamentally contradictory (and therefore irrational) to make a general rule that allows lying because it would cause the concepts of lies and truths to lose their meaning

- it treats people as a means rather than as autonomous beings with their own ends

In contrast, consequentialists are less concerned with universal obligations. Instead, their foundation for moral judgement rests on consequences that flow from different acts or rules. If a lie will cause good outcomes overall, then (broadly speaking) a consequentialist would think it was justified.

There are other things we might want to consider by themselves, outside the confines of a moral framework. For example, we might think that sometimes people aren’t entitled to the truth in principle. For example, during a war, most people would intuit that the enemy isn’t entitled to the truth about plans and deployment details, etc. This leads to a more general question: in what circumstances do people forfeit their right to the truth?

What about “white lies”? These lies usually benefit others (sometimes at the liar’s expense!) or are about trivial things. They’re usually socially acceptable or at least tolerated because they have harmless or even positive consequences. For example, telling someone their food is delicious (even though it’s not) because you know they’ve had a long day and wouldn’t want to hurt their feelings.

Here are some things to ask yourself if you’re about to tell a white lie:

- Is there a better response that is truthful?

- Does the person have a legitimate right to receive an honest answer?

- What is at stake if you give a false or misleading answer? Will the person assume you’re telling the truth and potentially harm themselves as a result of your lie? Will you be at fault?

- Is trust at the foundation of the relationship – and will it be damaged or broken if the white lie is found out?

- Is there a way to communicate the truth while minimising the hurt that might be caused? For example, does the best response to a question about an embarrassing haircut begin with a smile and a hug before the potentially hurtful response?

Lying is a more complex phenomenon than most people consider. Essentially, our general moral aversion to it comes down to its ability to inhibit or destroy communication and cooperation – requirements for human flourishing. Whether you care about duties, consequences or something else, it’s always worth questioning your intentions to check if you are following your moral compass.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ad Hominem Fallacy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn and feminism

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Buddha

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Anti-natalism: The case for not existing

Partway through the New Yorker’s profile of leading philosopher David Benatar, there is an anecdote that sums up his ethical position neatly.

A colleague at Benatar’s university announces to the department that she is pregnant. Benatar is pushed by the colleague as to whether he is happy about the news. Benatar thinks, then replies: “I am happy,” he says. “For you.”

Benatar is a leading advocate for the philosophical school known as anti-natalism. For such thinkers, being born is a harm. As it is so cleanly put in the title of his best-known work, Benatar believes that for each of us, it would have been better for us to never have been – non-existence is preferable to existence. Benatar might be happy for his colleague, but he is not happy for the conceived child who now faces a future of pain, distress and fear.

For such a seemingly pessimistic outlook, Benatar’s arguments in favour of anti-natalism are shockingly elegant. Take, for instance, his foundational view: the asymmetry of pleasure and pain. According to Benatar, pain is bad; pleasure is good. An absence of pain is good. But an absence of pleasure is not bad for the person for whom that absence is not a deprivation.

Imagine, for instance, that one day, on a morning stroll, you encounter a branching path. You take the left road. A few metres ahead, you spot a $100 bill lying on the ground. This brings you a deep pleasure. But now let’s say that you never took the left road – that you instead veered right. In this possible world, you do not encounter the $100 bill. If you had taken the left path, you would have. But you don’t know that. You have not been promised any money; you are not aware of what you have lost. Thus, Benatar thinks, you have not been harmed.

This is the key to the anti-natalist position. The child who is never born does not know that they are missing out on the pleasures of life; there is no entity who has been deprived, because there is no entity that exists. Moreover, the child who is born might encounter these pleasures, but they will also encounter a great number of pains. For Benatar, life is a myriad of tiny, complicated discomforts, from being hungry to needing the bathroom. Not bringing a child into the world means avoiding the perpetuation of suffering, saving an entity from a long, painful life for which the only escape – suicide, death, illness – is more pain.

These views may sound, for some, deeply psychologically distressing, and Benatar acknowledges that these are not easy pills to swallow. But he believes that they are necessary truths; that they are, in a sense, inevitable conclusions to be drawn from the nature of being a conscious entity in the world.

“I think that there is something hopeless and psychologically distressing about the nature of sentient life that makes anti-natalism the correct position to hold,” he explains.

Benatar’s position has been criticised by a number of thinkers, most recently by the stoic philosopher Massimo Pigliucci, who argued against the asymmetry of pleasure and pain in a recent blog post. According to Pigliucci, pain need not be morally bad; pleasure need not be morally good. For the stoic, these are “indifferents”, their moral value neutral.

But Benatar believes that Pigliuicci has misattributed claims to him. “The asymmetry I describe is not itself a moral claim – even though it supports moral claims about the ethics of procreation,” he explains. “My claims about pain and pleasure are claims about their prudential value for the person whose pain and pleasure they are – or would be.”

“Anybody – and I am not suggesting that Professor Pigliucci is among them – who denies that pain is intrinsically bad for the person whose pain it is, and that pleasure is intrinsically good for the person whose pleasure it is, does not understand what pain and pleasure are, and how and why they arose evolutionarily. If pain does not feel bad, it is not pain. If pleasure does not feel good, it is not pleasure.”

Others still have compared Benatar’s positions to those held by ecofascists, thinkers who believe that humanity is a virus that is wreaking a havoc on the natural world, and that the only way to avoid this suffering is to force the extinction of the human race. Indeed, there is at least some overlap between ecofascist beliefs and anti-natalist ones – both argue in favour of the end of human life – but Benatar is untroubled by such a connection, for the same reason that “those of us opposed to smoking should not be troubled that the Nazis were also opposed to smoking.”

“Even though (some) anti-natalists think that humans are bad for the environment, this shows only that they agree with the ‘eco’ part of ‘ecofascism’,” Benatar explains. “Anti-natalists are not committed to the ‘fascism’ part – and should, I argue, be opposed to it.”

Benatar’s position might seem deeply cynical, even nihilistic, but there is a strange kind of hope in it too. “Part of the reason why some people may find anti-natalism unthinkable is that they cannot correctly imagine what a world without sentient life would be like,” he explains. For the anti-natalist, there is some comfort to be taken in this potential, consciousness-free world – a world without suffering, without pain, without suicide or famine or death. After all, what, paradoxically, is more optimistic than that?

David Benatar presents The Case for Not Having Children at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2024. Tickets on sale now.

Image by Aarón Blanco Tejedor

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Scepticism

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Pragmatism

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

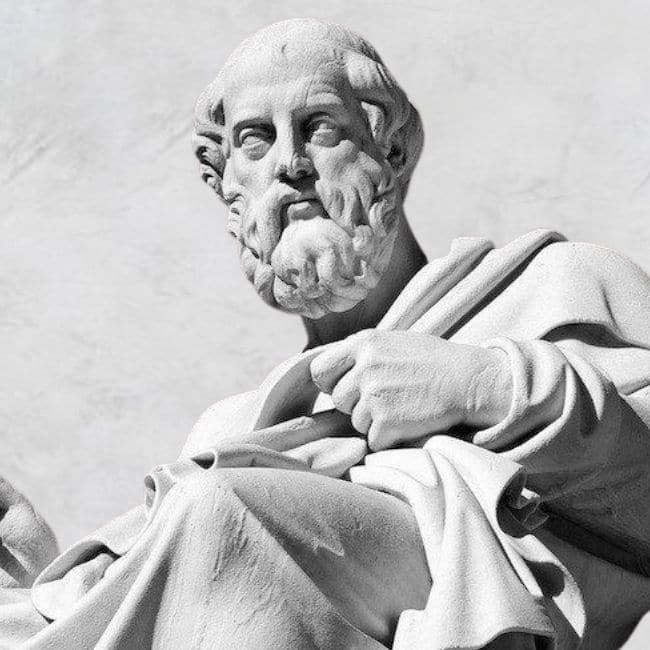

Big Thinker: Plato

Plato (~428 BCE—348 BCE) is commonly considered to be one of the most influential writers in the history of philosophy.

Along with his teacher, Socrates, and student, Aristotle, Plato is among the most famous names in Western philosophy – and for good reason. He is one of the only ancient philosophers whose entire body of work has passed through history in-tact over the last 2,400 years, which has influenced an incredibly wide array of fields including ethics, epistemology, politics and mathematics.

Plato was a citizen of Athens with high status, born to an influential, aristocratic family. This led him to be well-educated in several fields – though he was also a wrestler!

Influences and writing

Plato was hugely influenced by his teacher, Socrates. Luckily, too, because a large portion of what we know about Socrates comes from Plato’s writings. In fact, Plato dedicated an entire text, The Apology of Socrates, to giving a defense of Socrates during his trial and execution.

The vast majority of Plato’s work is written in the form of a dialogue – a running exchange between a few (often just two) people.

Socrates is frequently the main speaker in these dialogues, where he uses consistent questioning to tease out thoughts, reasons and lessons from his “interlocutors”. You might have heard this referred to as the “Socratic method”.

This method of dialogue where one person develops a conversation with another through questioning is also referred to as dialectical. This sort of dialogue is supposed to be a way to criticise someone’s reasoning by forcing them to reflect on their assumptions or implicit arguments. It’s also argued to be a method of intuition and sometimes simply to cause puzzlement in the reader because it’s unclear whether some questions are asked with a sense of irony.

Plato’s revolutionary ideas span many fields. In epistemology, he contrasts knowledge (episteme) with opinion (doxa). Interestingly, he says that knowledge is a matter of recollection rather than discovery. He is also said to be the first person to suggest a definition of knowledge as “justified true belief”.

Plato was also very vocal about politics, though many of his thoughts are difficult to attribute to him given the third person dialogue form of his writings. Regardless, he seems to have had very impactful perspectives on the importance of philosophy in politics:

“Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequately philosophize, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide, while the many natures who at present pursue either one exclusively are forcibly prevented from doing so, cities will have no rest from evils, … nor, I think, will the human race.”

Allegories

You might have also heard of The Allegory of the Cave. Plato reflected on the idea that most people aren’t interested in lengthy philosophical discourse and are more drawn to storytelling. The Allegory of the Cave is one of several stories that Plato created with the intent to impart moral or political questions or lessons to the reader.

The Ring of Gyges is another story of Plato’s that revolves around a ring with the ability to make the wearer invisible. A character in the Republic proposes this idea and uses it to discuss the ethical consequences of the item – namely, whether the wearer would be happy to commit injustices with the anonymity of the ring.

This kind of ethical dilemma mirrors contemporary debates about superpowers or anonymity on the internet. If we aren’t able to be held accountable, and we know it, how is that likely to change our feelings about right and wrong?

The Academy

The Academy was the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. It was founded by Plato some time after he turned 30, after inheriting the property. It was free and open to the public, at least during Plato’s time, and study there consisted of conversations and problems posed by Plato and other senior members, as well as the occasional lecture. The Academy is famously where Aristotle was educated.

After Plato’s death, the Academy continued to be led by various philosophers until it was destroyed in 86 BC during the First Mithridatic War. However, Platonism (the philosophy of Plato) continued to be taught and revived in various ways and has had a lasting impact on many areas of life continuing today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Big thinker

Relationships

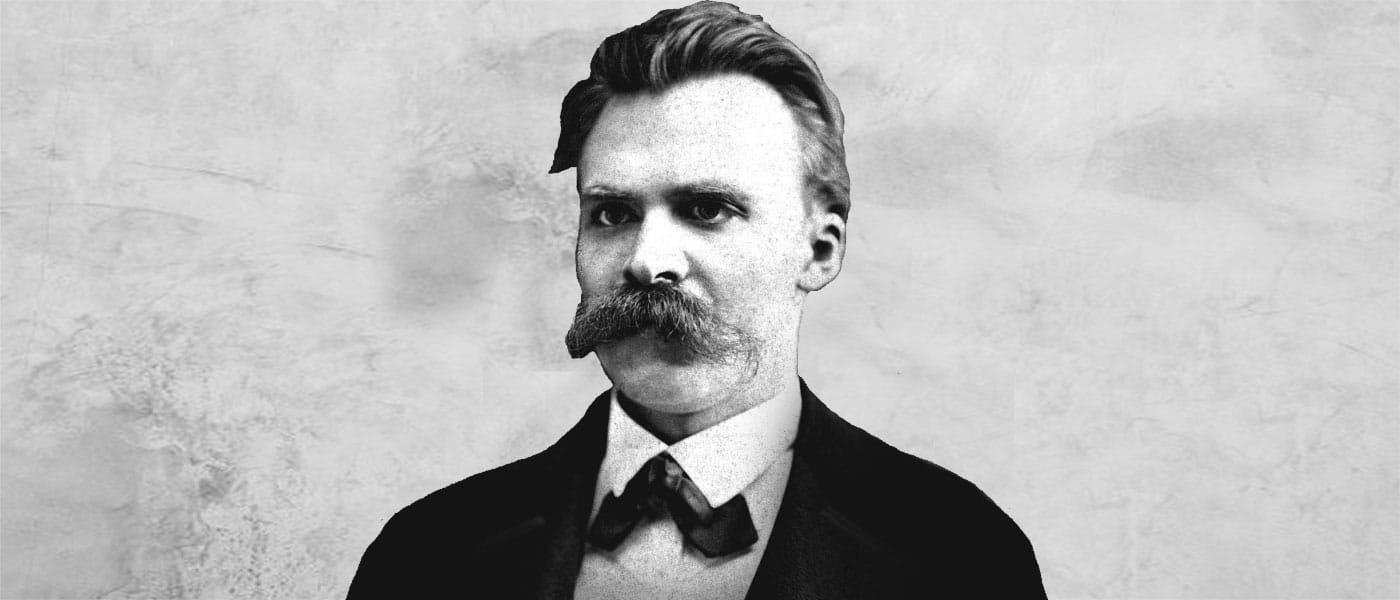

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Epistemology

Mostly, we take “knowledge” or “knowing” for granted, but the philosophical study of knowledge has had a long and detailed history that continues today.

We constantly claim to ‘know things’. We know the sun will rise tomorrow. We know when we drop something, it will fall. We know a factoid we read in a magazine. We know our friend’s cousin’s girlfriend’s friend saw a UFO that one time.

You might think that some of these claims aren’t very good examples of knowledge, and that they’d be better characterised as “beliefs” – or more specifically, unjustified beliefs. Well, it turns out that’s a pretty important distinction.

“Epistemology” comes from the Greek words “episteme” and “logos”. Translations vary slightly, but the general meaning is “account of knowledge”, meaning that epistemology is interested in figuring out things like what knowledge is, what counts as knowledge, how we come to understand things and how we justify our beliefs. In turn, this links to questions about the nature of ‘truth’.

So, what is knowledge?

A well-known, though still widely contentious, view of knowledge is that it is justified true belief.

This idea dates all the way back to Plato, who wrote that merely having a true belief isn’t sufficient for knowledge. Imagine that you are sick. You have no medical expertise and have not asked for any professional advice and yet you believe that you will get better because you’re a generally optimistic person. Even if you do get better, it doesn’t follow that you knew you were going to get better – only that your belief coincidentally happened to be true.

So, Plato suggested, what if we added the need for a rational justification for our belief on top of it being true? In order for us to know something, it doesn’t just need to be true, it also needs to be something we can justify with good reason.

Justification comes with its own unique problems, though. What counts as a good reason? What counts as a solid foundation for knowledge building?

The two classical views in epistemology are that we should rely on the perceptual experiences we gain through our senses (empiricism) or that we should rely first and foremost on pure reason because our senses can deceive us (rationalism). Well-known empiricists include John Locke and David Hume; well-known rationalists include René Descartes and Baruch Spinoza.

Though Plato didn’t stand by the justified true belief view of knowledge, it became quite popular up until the 20th century, when Edmund Gettier blew the problem wide open again with his paper “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?”.

Since then, there has been very little consensus on the definition, with many philosophers claiming that it’s impossible to create a definition of knowledge without exceptions.

Some more modern subfields within epistemology are concerned with the mechanics of knowledge between people. Feminist epistemology, and social epistemology more broadly, deals with a lot of issues that raise ethical questions about how we communicate and perceive knowledge from others.

Prominent philosophers in this field include Miranda Fricker and José Medina. Fricker developed the concept of “epistemic injustice”, referring to injustices that involve the production, communication and understanding of knowledge.

One type of knowledge-based injustice that Fricker focuses on, and that has large ethical considerations, is testimonial injustice. These are injustices of a kind that involve issues in the way that testimonies – the act of telling people things – are communicated, understood, believed. It largely involves the interrogation of prejudices that unfairly shape the credibility of speakers.

Sometimes we give people too much credibility because they are attractive, charismatic or hold a position of power. Sometimes we don’t give people enough credibility because of a race, gender, class or other forms of bias related to identity.

These types of distinctions are at the core of ethical communication and decision-making.

When we interrogate our own views and the views of others, we want to be asking ourselves questions such as: Have I made any unfair assumptions about the person speaking? Are my thoughts about this person and their views justified? Is this person qualified? Did I get my information from a reliable source?

In short, a healthy degree of scepticism (and self-examination) should be used to filter through information that we receive from others and to question our initial attitudes towards information that we sometimes take for granted or ignore. In doing this, we can minimise misinformation and make sure that we’re appropriately treating those who have historically been and continue to be silenced and ignored.

Ethics draws attention to the quality and character of the decisions we make. We typically hold that decisions are better if well-informed … which is another way of saying that when it comes to ethics, knowledge matters!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Anti-natalism: The case for not existing

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Power and the social network

In science, power has a very precise definition. It is the rate at which energy is being transferred – a relationship that is captured in a formula and can be thought of more informally as the amount of “work” being done.

So, in a scientific context – specifically physics, the meaning of power is clear. In contrast, power is a far more complex concept in social sciences – as revealed within a diverse range of human interactions.

There are two prevailing views on the nature of power. The first regards power predominantly as a tool for subjugation, while the second acknowledges its potential for harmful use while also pointing to its potential role in maintaining balance.

Thomas Hobbes championed the first notion, conceptualising one man’s gain in power as another man’s loss. A straightforward illustration of this can be seen in a wrestling match where two people compete, with one eventually winning. That outcome is incompatible with both having equal power. Even if they do so initially, a relative increase in power eventually accrues to the victor.

The second perspective on power is provided by Michel Foucault, who considered its nature to be more subtle and varied. He proposed that power assumes many forms and is invested in many things. This latent power only arises when an individual engages in conversation around ‘regimes of truth’ or understanding. Foucault’s definition of power is thus more charitable. He thinks of power as an entity that resides in all things rather than a structure through which people/things can mobilise control. He notes that power is synonymous with knowledge and fact.

In older structures, such as government and politics, it’s challenging for an individual to lose power entirely. A benefit of having power is that can enhance the credibility and longevity of a person’s philosophy. Even though someone may lose their position and ability to make decisions in government, they often retain their power to exercise influence within their social circles provided their personal credibility remains intact. This is how ‘informal’ power (influence) can shape the exercise of formal power.

This permanence of power is an important determinant of the behaviour of those in power. Confidence in the enduring nature of power (and its ability to ward off adverse consequences) often leads the powerful to make choices that advance their personal interests.

Social media has begun to redefine the nature of power. The dominant platforms have gained tremendous traction over the past decade, and gradually personal identity has become synonymous with online presence. Widespread fame and the attainment of a quasi-celebrity status has given key ‘influencers’ the ability to exercise ‘informal’ (but none the less real) power through the vector of their online followers. But social media fame is even more fickle than that gained through traditional means as its basis is intrinsically unpredictable.

As such, social media provides some useful insights into the new dynamics of power within a technological setting. For example, in the case of social media, power is actually being exercised by those who offer a response to what ‘influencers’ post. When you use social media, you use and direct your power through likes and comments offered in response to what has been posted. However, if you disapprove of something you’ve observed, you can withhold your endorsement or even actively express your disdain through dislikes and critical comments – in other words actively withdrawing your support can be part of a conscious act to diminish the power. So, where does power lie? With the influencers or their potentially fickle followers?

The technology that underpins social media platforms has also ‘democratised’ power in that almost anyone can gain a following and thus have the potential to exert a degree of influence.

It’s much easier now to establish a position of power online than it was traditionally – because of ease of access and the fact that there is no limit to the number of people who can have a platform and broadcast their views widely.

But this increase in access to power is a double-edged sword because, as quick as it is for someone to gain power through today’s media, they can just as easily lose it.

As a result, many ‘celebrities’ have short-lived fame. The fleeting nature of power has extended beyond the realm of social media into the offline world. For example, the twenty-four-hour media cycle and the need to feed an insatiable media ‘beast’ means that politicians now operate under an intense and unceasing public gaze. Even the slightest whiff of scandal can end a career – and end access to a formal source of power.

In modern societies, scrutiny drives and confers power by facilitating influence.

Online power is probably best conceptualised as a mixture of Foucault’s and Hobbes’ descriptions of power.

Overall, we see how our old structures of power perhaps do not adapt easily to the online world. The reachability and balance of the internet make it easier to comment on those in power and hold them accountable for their actions. Ultimately, the dynamic is shifting; while the factors that give people power – influence, connection, and money – remain prevalent on the internet, the power they generate is no longer as enduring.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

BY Mehhma Malhi

Mehhma recently graduated from NYU having majored in Philosophy and minoring in Politics, Bioethics, and Art. She is now continuing her study at Columbia University and pursuing a Masters of Science in Bioethics. She is interested in refocusing the news to discuss why and how people form their personal opinions.

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 OCT 2021

At The Ethics Centre, we firmly believe ethics is a joint effort. It’s a conversation about how we should act, live, treat others and be treated in return.

That means we need a range of people participating in the conversation. That’s why we’re excited to share that we have recently appointed Joshua Pearl as a Fellow. CFA-accredited, and with a Master of Science in Economics and Philosophy from the London School of Economics, Josh is currently a director at Pembroke Advisory. He also has extensive experience as a banking analyst, commercial advisor and political advisor – diverse perspectives that inform his writing.

To welcome him on board and introduce him to you, our community, we sat down for a brief get-to-know-you chat.

You have a background in finance, economics and government, and also completed a Master of Science in Economics and Philosophy – what attracted you to the field of philosophy?

I had always read a lot of political philosophy but when I first worked as a political advisor, it really dawned on me how little I actually knew. I figured what better way to learn more than by studying philosophy at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Tell us a little bit about your background in finance, and how that shapes your approach to philosophy.

My undergraduate degree was in economics and finance and my first job out of university was with an investment bank. Later on, I worked for an infrastructure development and investment firm. I’ve really enjoyed my professional experience, especially later in my career, though there were times early on when I questioned whether I was sufficiently contributing to society. And in truth, I probably wasn’t.

One way working in finance has helped the way I think about philosophy is that finance is practical. It’s a vocation. So when I think about philosophy I try to answer the “so what” questions. Why should we care about a certain issue? What are the practical implications?

In the context of finance, there are so many practical philosophical questions worth asking. What harm am I responsible for as an investor in a company that manufactures or owns poker machines? Should shareholders be advocating for corporate and regulatory change to help combat climate change? What are the implications of a misalignment between my investments and my personal values? And in the context of economics, philosophical questions are everywhere. What does a fair taxation system look like? How are markets equitable? Is it a problem that central bank policies increase social inequality?

These are super interesting issues (or at least I think so!) that have practical implications.

You mentioned you worked in government as a political advisor – what did you take out of that experience?

It was an amazing experience in so many ways. It was fantastic to work with really interesting people from a variety of backgrounds and have the opportunity to meet so many different members of the community, whom I wouldn’t normally have the opportunity to meet. I also felt very lucky to work for a woman whom I have a lot of respect for. Someone from a non-traditional background who has not only been very successful in her political career but has also contributed to society in a really positive way.

One of my biggest learnings from the experience was how important it is to try and consider issues from a range of multiple perspectives, with the hope of getting closer to some objective view. As part of this process, you realise the legitimate plurality of views that exist and the intellectual and moral uncertainty associated with your own views.

Do you have a favourite philosopher or thinker?

Thomas Nagel is a rockstar. He is in his eighties now and is still teaching at New York University. He is a really clear thinker whose writing is accessible and entertaining, and he isn’t afraid to challenge the orthodox views of society, including in areas such as science, religion and economics.

Nagel is a prolific writer who has undertaken philosophical inquiries across a range of fields such as taxation (the Myth of Ownership), evolution (Mind and Cosmos), and epistemology and ethics (The View from Nowhere). His most famous piece is probably What is it like to be a bat?, a journal article that is a must read for anyone interested in human consciousness.

If I could add a reasonably close second it would be Toby Ord. Ord is a young Australian whose work has already had huge real-world impacts in effective altruism (how can philanthropy be most effective) and the way society thinks about existential human risks. His recent book, The Precipice, was published in 2019 and analysed risks such as comet collisions with Earth, unaligned artificial intelligence and pandemics…

Covid restrictions have of course played havoc on the economy and our personal lives in the past 18 months – how have you been coping personally with lockdowns?

I arrived back in Australia on the very day mandatory hotel quarantine was introduced, so in some sense, everything since then has been a breeze! But to be honest, lockdown hasn’t affected me that much and I’m lucky to live with a really amazing partner. Over the course of lockdown, I’ve read a little more, written a little more, played tennis a little more… and spent way too much time trying to do cryptic crosswords.

Do you see any fundamental changes to our economic systems coming about as a result of the pandemic?

I don’t know that there will be fundamental changes, but I do hope there will be positive incremental changes. One is central bank policy. It seems inevitable that at some stage there will be a review of the RBA and with luck we follow the Kiwis’ lead and ask the RBA to consider how their policies inflate financial asset and house prices – the results of which add substantial risk to the financial system and increase social inequality. The second is what happens if (or perhaps when) Australia considers how to reduce the COVID fiscal debt. I am hopeful that we will consider land and inheritance taxes for reasons of fairness, rather than simply taxing people more for doing productive things like going to work.

As a consultant and Fellow of The Ethics Centre, what does a normal day look like for you?

My days are pretty structured, but the work is really variable.

My consulting focus is on issues at the intersection of finance, economics and government, such as sustainable and ethical business and investment. That might be working on an infrastructure project with an investment bank or government; undertaking a taxation system review for a not-for-profit; or working on ethical and sustainable investing frameworks and opportunities with various institutions, including with The Ethics Centre, which has been fantastic.

As a Fellow of The Ethics Centre, my primary involvement is through writing articles on public policy issues, with the aim of teasing out the relevant philosophical components. Questioning purpose, meaning and morality is part of being human. And it is also something we all do, all of the time. Yet there are very few forums to engage on these topics in a constructive and meaningful way. The Ethics Centre provides a forum to have these conversations and debates, and does so outside of any particular political, corporate or media lens. I think this is a huge contribution that really strengthens the Australian social fabric, so I feel really lucky to be involved with The Ethics Centre community.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

That certainly is the big one! I tend to think about ethics on both a personal and social basis.

On a personal basis, to me, ethics is about determining how best to live your life, informed by such things as your family’s values, social norms, logic and religion. Determining your “ideal life” so to speak. It is then about the decisions made in trying to achieve that ideal, failing to achieve that ideal, and then trying again.

On a social basis, to me, a large part of ethics is the fairness of our social institutions. Our political institutions, legal frameworks, economic systems and corporate structures, as examples. Pretty cool areas, I think.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ANZAC day lie

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Plato’s Cave

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Ethics Centre Nominated for a UNAA Media Peace Award

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 OCT 2021

Judith Butler (1956—present) is an American academic and activist, who has made considerable contributions to philosophy, literature, gender and feminist studies.

They are the Maxine Elliot Professor in the Department of Comparative Literature and the Program of Critical Theory at the University of California, Berkeley and holds the Hannah Arendt Chair at the European Graduate School in Sass Fee, Switzerland.

Although Butler has an impressive number of publications to their name, they are best known for their book, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1989; 1990).

Gender Trouble

Gender Trouble explores the traditional understandings of sex and gender in feminist theory. Butler argues against the view that gender is based on (or follows from) our biology, claiming instead that gender is produced by performance – that we construct gender by behaving and expressing ourselves in certain ways.

This “gender performativity” has been interpreted in different ways. Some have taken performativity to mean that gender is determined by society and therefore completely outside of the individual’s control (i.e., you are the gender you have been assigned).

Others have understood performativity to mean that gender can be chosen or changed at will, since it has no biological basis. Members of the trans community have critiqued this understanding, saying that conceiving of gender as something that can be changed voluntarily makes it seem superficial or fake and risks undermining how important someone’s gender identity can be to their sense of self.

More recently, Butler has clarified their own understanding of gender performativity, stating:

Butler’s understanding of gender performativity lies somewhere in between the two previous views. For Butler, gender is not something that is fixed by society and unalterable on an individual level, but it is also not something superficial that can be changed like a piece of clothing. Instead, gender is created through sustained practices that make gender appear as though it’s something natural or internal to us, but really these practices are influenced and regulated by society and culture. By recognising this, Butler says, we can collectively start to change gender norms so that we can each find a way to live more authentically.

Though the term ‘non-binary’ did not exist at the time Butler published Gender Trouble, in recent years Butler has changed their legal gender to non-binary and uses she/they pronouns.

After Gender Trouble

Gender Trouble had a profound influence over the development of feminist theory and is widely considered to be one of the founding texts of queer theory. Since its publication in 1989, Gender Trouble has been translated into 27 languages and has become a staple text for feminist and gender studies courses all over the world.

As a result, Butler has achieved a fame that transcends the academic community – and it hasn’t always been positive.

For some people, Butler’s views are considered dangerous or threatening to the traditional way of life. In 2017, evangelical Christian protestors burnt an effigy of Butler outside an academic conference they were attending in Brazil, while chanting “take your ideology to hell.”

Despite this, Butler continues to write and speak about gender, feminist and queer issues and is active in the resistance against the anti-gender movement – an international movement that opposes gender equality, LGBTQIA+ rights and sexual and reproductive freedoms.

Butler has, for many years, been a vocal advocate for the rights of marginalised people and has been active in anti-war and anti-racism movements.

Their most recent book, The Force of Non-violence: An Ethico-Political Bind (2020), argues that social inequality cannot be separated from our understanding of violence. For Butler, violence is not just swinging fists and wielding weapons. Violence is any action (or inaction) that harms another – including public policies and institutional practices that create social inequalities.

In response to this kind of violence, Butler advocates nonviolence. Importantly, however, Butler does not understand nonviolence as something passive. Nonviolence requires an aggressive commitment to radical equality and an “opposition to biopolitical forms of racism and war logics that regularly distinguish lives worth safeguarding from those that are not.”

Butler wants us to recognise that we are all in this together and build a world that is reflective of this – a world that is committed to radical equality.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships