Do we have to choose between being a good parent and good at our job?

Do we have to choose between being a good parent and good at our job?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 6 NOV 2019

I’m half writing this, half thinking about whether it is the best use of a few precious, toddler-free moments.

“Framing the issue of work-life balance – as if the two were dramatically opposed – practically ensures work will lose out. Who would ever choose work over life?” writes work-life guru Sheryl Sandberg.

Who indeed?

Well, for one, those who can’t afford to walk away from a job. Unless you’re living very comfortably, you’ll usually be forced to choose work over life. But even setting aside the many people who find themselves in that situation, it’s not clear we live in a world that enables people to choose life over work. Take me, for example.

Today is Friday. It’s the beginning of my three-day weekend. Thanks to flexible working arrangements, Friday is my father-son day. We go to the park, get errands done, pop out to the zoo – it’s brilliant, and I wouldn’t swap it for anything. You’d think I’m the perfect demonstration of Sandberg’s argument, but I’ve got itchy feet. So here I am, writing an op-ed.

Or rather, I’m half writing, half thinking about whether this is the best use of a few precious, toddler-free moments. Would I rather get things done around the house and revel in the simple, domestic bliss of a clean kitchen or a floor free of stickers, marbles and other paraphernalia?

I feel this back-and-forth all the time. It’s a war of identities: the professional version of me is ambitious, busy, focused and demanding; domestic me is patient, spontaneous and calm (for the most part). To be honest, it’s exhausting, and it’s beginning to make me think we haven’t fully figured out what work-life balance really means.

At the moment, we think about work-life balance in terms of the way we allocate our time. A well-balanced life is one in which you can leave work at a reasonable hour, spend enough time on parental or annual leave with loved ones, and where parents can balance care obligations to enable both people to have flourishing lives and careers.

“A well-balanced life is one in which you can leave work at a reasonable hour, spend enough time on parental or annual leave with loved ones, and where parents can balance care obligations to enable both people to have flourishing lives and careers.”

A look at recent proposals in the work-life balance seems to support this: the four-day working week, gender-balanced leave policies, email restrictions and unlimited annual leave all march to the beat of the time-maximisation drum.

This is where I think Sandberg is right – there is something wrong with painting work and life as diametrically opposed, but it’s not what she thinks. It’s because it permits a world in which “work” and “life” are kept totally separate and are permitted to operate according to different norms and values.

My favourite example of this is the unintended viral sensation Robert Kelly, his kids Marion and James and his wife Jung-a Kim, who together conspired to make the best couple of minutes of television in BBC history. After the incident, Kelly copped criticism from some circles for failing to be a good father because he didn’t scoop his daughter up and pop her on his knee during an international broadcast interview. By contrast, the BBC praised Kelly for his professionalism.

Whether Kelly did the right thing or not depends on how you define him in that precise moment. Was he a father or a professor? For Kelly, in the midst of that moment, the dilemma is the same: who should he choose to be, right now?

Unfortunately, based on our current norms around professionalism, he can’t be both at the same time. According to the scripts he seems to have been judged by, Kelly needed to be detached, rational and stoic and simultaneously warm, unconditionally affectionate and responsive. And this is why I think the work-life balance discussion needs to go beyond time and begin to think about identity. We need to permit people to express their domestic identities in the workplace – to redefine what it means to be professional so that it’s not unrecognisable to the people who know us in our personal lives.

These are all good things, but I’m not sure they can do the job on their own. Australian men often don’t take all the parental leave they’re entitled to. There’s little point giving people all this time if those people don’t know what to do with it, or aren’t equipped to use it as they should.

“As we continue to deconstruct unhelpful, gendered divisions of labour that force women to take on domestic and emotional labour and leave men to seek paid employment, there’s a good chance more people are going to start facing these choices – between professional and domestic life.”

“As we continue to deconstruct unhelpful, gendered divisions of labour that force women to take on domestic and emotional labour and leave men to seek paid employment, there’s a good chance more people are going to start facing these choices – between professional and domestic life.”

This isn’t just important for wellbeing. Bringing “domestic virtues” of emotional expressiveness, vulnerability and the like into the workforce helps shape people’s character. Our environments shape who we are. The more we’re encouraged to be competitive, ambitious or whatever else in the workplace, the harder it will be to switch gears and express patience, humility or generosity at home.

The purpose of work-life balance is to help people to flourish, live happy lives outside of work and develop into well-rounded human beings. If we’re going to do that, we need to let people be well-rounded at work too.

This article was written for, and first published by The Guardian. Republished with permission.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Raewyn Connell The Ethics Centre 15 OCT 2019

If we ask the question, ‘are men fragile?’ my answer would be that quite a number certainly are.

We can see this in the health data. Men, compared with women, have higher levels of some kinds of mental health problem – especially alcoholism and sociopathic disorders. Men, again compared with women, have higher levels of occupational injury and coronary heart disease, higher rates of completed suicide, and – especially young men – much higher rates of injury and death on the road.

These are all long-standing patterns, and society should provide support in the form of men’s health programmes. We should also ask why these patterns exist – given that men’s bodies are not notably weaker than women’s bodies. Which leads us to the question of masculinity.

If we ask the question, ‘is masculinity fragile?’ the answer looks different. Masculinity is a social pattern, and our societies usually define its hegemonic form in terms of power, aggression, wealth and authority. So it’s mainly men who are recruited to run the world.

We may celebrate a first female leader of some country or firm, but the enormous majority of Presidents, Prime Ministers and CEOs are actually blokes in suits. (93.4% of the CEOs of Fortune 500 corporations this year, for instance.) There have not been all that many women Popes, archbishops, chief muftis, abbots, generals, admirals, Treasurers or Directors of the CIA.

There’s a robust social basis for these patterns. Part of it is economic – for the real “gender gap”, look at the superannuation statistics. Part of it is institutional – even in our lovely universities, four-fifths of full professors are blokes, though admittedly some of them don’t wear suits.

Part of it is cultural – turn on the television, and you are likely to see a screen full of extremely fit young men giving a display of professional skill and force. Those who do it best become famous role models and are given a lot of money. Last year Cristiano Ronaldo took home 61 million dollars in salary from Real Madrid, plus 47 million in endorsements. And he was only the second highest paid footballer.

Of course there are other patterns of masculinity – we should really speak of masculinities in the plural. When the media speak of “toxic masculinity” they are pointing to a specific pattern of masculinity that is bidding for the dominant place by putting down alternatives. We have a spectacular example in the career of Mr Trump – it’s hard to miss the element of resentment and revenge in his story.

The patriarchal gender order is not a perfectly-functioning machine. Indeed, since the days of President Eisenhower and Sir Robert Menzies it has seen a deep erosion of legitimacy. What would they have made of the gay marriage survey! Well, we get a glimpse in the current authoritarian backlash around the world. Which goes to show, not that masculinity is fragile, but that gender orders change. They can change for the worse; I live in hope they will change for the better.

Raewyn Connell was one of the speakers at our IQ2 Debate ‘Masculinity – is it really so fragile?’. The debate took place at Sydney Town Hall Wednesday 23 October. She was joined by Catharine Lumby, Zac Seidler and David Leser. Watch the full debate here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If you condemn homosexuals, are you betraying Jesus?

BY Raewyn Connell

is one of Australia’s leading social scientists, specialising in class, gender, education, global patterns in knowledge, and most prominently, masculinity. She is one of four speakers at our upcoming debate, 'Masculinity – is it really so fragile'.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Free speech has failed us

I used to believe in free speech. I used to believe in the power of rational discourse.

I used to believe in what Jurgen Habermas called the “unforced force” of the better argument. I used to believe in John Stuart Mill’s riff that free speech is what keeps superstition and stifling tradition at bay. I used to believe the solution to an abundance of bad speech was more speech.

However, I’m currently going through a somewhat unsettling process of reconsidering these deeply held views. The last two decades has been one long demonstration of the failures of public discourse to drive towards better solutions to the problems we face.

I hardly need to cite the failure of public discourse to prevent the folly of the wars following September 11 and the catastrophic regional destabilisation they caused, or to reform the economic institutions that caused the Global Financial Crisis, or to improve the response to it that ended up bailing out the perpetrators at the expense of the victims, or bring peace to the escalating culture wars that are fracturing nations, or prevent the national self immolation that is Brexit, or stop the election of a dangerously ill-informed narcissist of dubious moral character to the Presidency of the United States, or combat the ongoing misinformation campaign that is resisting action on one of the world’s most urgent challenges: dealing with climate change. And that’s not even an exhaustive list.

Free speech has failed to live up to its liberal promise. It has failed to float the best reasons and arguments to the top and sink the worst ones to the bottom.

Free speech has failed to live up to its liberal promise. It has failed to float the best reasons and arguments to the top and sink the worst ones to the bottom. It has failed to prevent those who actively work to pervert speech from winning over the voting public. It has empowered those who would wilfully employ their reach to promote their ideological agenda. Meanwhile, those who stick to the rules of rational discourse are left shuffling footnotes and politely yelling reasons into the void.

So when The Conversation announced recently that it will be taking a “zero-tolerance approach to moderating climate change deniers, and sceptics” in the comments on its articles, I was not shocked.

Once upon a time, we viewed #ClimateChange sceptics as merely frustrating. Not anymore.

As a publisher, we won’t perpetuate ideas that will destroy the planet.@mishaketch explains @ConversationEDU‘s zero-tolerance for climate deniers: https://t.co/VbRmFWWycC

— The Conversation (@ConversationEDU) September 18, 2019

Only a year ago, I would have agreed with the ABC’s Media Watch that “The Conversation is wrong to ban anyone’s views, unless they’re abusive, hateful or inciting violence.” I would have defended the right of the ignorant, misinformed and outright malicious to say their piece and have it shredded by other less ignorant, more informed and hopefully charitable readers.

After all, what’s the alternative? We shut down speech and enable one particular narrative to dominate? Who’s in charge of that narrative? Can we trust them to have more reliable access to the truth? What do we do if that narrative is wrong?

I’m still painfully aware of the importance of these questions, and how hard they are to answer in any satisfying way. And yet, the evidence is clear to me now that in many cases more speech is not always in the best interests of truth or humanity.

In good faith

What has fundamentally changed in recent months is the way I think about free speech and the possibility of rational discourse in general.

Free speech is not an absolute good; it is not an end unto itself. Free speech is an instrumental good, one that promotes a higher good: seeking the truth. That’s the canonical account from John Stuart Mill that still underlies much of our thinking around free speech today.

But free speech only fulfils its truth-seeking function when all agents are speaking in good faith: when they all agree that the truth is the goal of the conversation, that the facts matter, that there are certain standards of evidence and argumentation that are admissible, that speakers have a duty to be open to criticism, and that there are many modes of discourse that are inadmissible, such as intimidation, insults, threats and the wilful spread of misinformation. Mill assumed all too readily that such good will was commonplace.

But free speech only fulfils its truth-seeking function when all agents are speaking in good faith.

This doesn’t mean that all speech is truth-seeking. In fact, most everyday speech is not about the truth at all. Usually the correct answer to “does my bum look big in this” is “no”, irrespective of the truth. Most speech is about reinforcing relationships, establishing identity or passing the time. Some speech is about subjective issues or values which may not admit true or false answers. Free speech protects this too. But for some speech, the facts do matter, and that’s where free speech is failing us.

In order for truth-seeking free speech to work, we need strong social norms that promote good faith. And it’s precisely these norms that have broken down in recent years (not that they were ever very strong). And this is because humans are not nearly as rational as we (or Mill) would like to think. And we’re painfully easy to manipulate.

When I teach critical thinking, I give the usual cautionary spiel about not flinging out argumentative fallacies, like the old ad hominem, ad populum or slippery slope. But the very fact that I have to give that spiel is because these fallacies work. When employed effectively, you’ll “win” a lot more arguments using fallacies than by playing by the rules – if you consider persuading/intimidating/misleading someone to accept your point of view a “win.”

I similarly caution students to be wary of the power of appeals to emotion and the force of social pressure, and to be mindful of cognitive biases that can lead our thinking astray. Again, these are important because they are the mechanisms that actually motivate many of our beliefs and that can be most effectively used to persuade others.

What I don’t say – but maybe I should – is that critical thinking is useful when it comes to policing one’s own thoughts, but it’s pitifully impotent when it comes to changing others’ minds. If you start throwing syllogisms across the dinner table, or politely point out that someone is affirming the consequent at the pub, or hope that revealing the contradictions embedded in someone’s assumptions in a comment thread on Facebook is going to change their mind, you’re quickly going to find out you’ve joined the ranks of those politely yelling reasons into the void. I know only too well what that feels like.

Anti-social media

Compounding this is the fact that we have gone to great lengths to build new technologies that promote the worst features of bad faith discourse. If you wanted to design a means of communication that made rational argumentation as difficult as possible yet rewarded the use of every argumentative fallacy under the sun, you’d be hard pressed to top Twitter. It only allows enough characters to express conclusions, not premises. The Like button gives the same weight to the expert as the ignoramus. Status is earned through number of followers, which is like institutionalising the fallacy of ad populum.

Facebook is just as bad for different reasons. Not long ago, if you had a penchant for conspiracy theories, racial vilification or fringe anti-science theories, you’d be hard pressed to find enough like-minded nutjobs in your neighbourhood to hold a bi-monthly tin foil hat dinner. Now, you can join with thousands of like-minded cranks from all around the world on a daily basis to reinforce and radicalise your views.

There’s also evidence that a group of people with diverse views will tend to gravitate towards the most extreme views in the group. And that people who believe one conspiracy theory tend to believe in and share many. And that cultivating outrage only promotes more animosity towards one’s perceived opponents and encourages greater retributive invective and bad faith.

There’s also abundant evidence that people find falsehoods to be more credible the more often they encounter them, even if they’re posted by someone who’s debunking them. As such, falsehoods spread more easily on social media than facts. So the outrage industry is self-sustaining, as even those raging against them share them with their friends, thus spreading the poison even further. (This is why I urge everyone to STOP SHARING GARBAGE on social media, even if you’re intending to debunk it, but particularly if it just pisses you off. The beast feeds on your friends’ eyeballs.)

Add the well known bubble effect, which filters out dissenting views and reinforces in-group identity, and bad faith is all but guaranteed. Free speech in this context only facilitates a slide away from the truth.

That being so, it’s with some alarm that I note that Facebook is now exempting politicians from its normal community standards – the same standards that are intended to prevent bad faith discourse like hate speech and harassment. According to Facebook’s new VP of Global Affairs and Communications, the former UK politician Nick Clegg, it’s because Facebook’s crew “are champions of free speech and defend it in the face of attempts to restrict it. Censoring or stifling political discourse would be at odds with what we are about.”

Clegg invokes a tennis analogy to describe Facebook’s approach to speech: “our job is to make sure the court is ready – the surface is flat, the lines painted, the net at the correct height. But we don’t pick up a racket and start playing. How the players play the game is up to them, not us.”

Here’s a better analogy. The court was never flat. Human psychology means it started off warped, and it’s twisted even more by the technology created by Facebook itself. The players know this, and some are exploiting it to their advantage, and to humanity’s disadvantage. If free speech is meant to do anything at all positive, then it takes active intervention to flatten the court, not a hands-off wilful abdication of responsibility.

If free speech is meant to do anything at all positive, then it takes active intervention to flatten the court, not a hands-off wilful abdication of responsibility.

Hit prediction: this policy is going to be a disaster, and Facebook will revoke it with grievous apologies either before or after the 2020 US Presidential election after a spate of heinous posts by politicians are left to fester on our feeds.

What worries me the most is that those who understand the failings of free speech the best are the ones who know how to use speech to manipulate us to their ends. It’s the political operatives, the Cambridge Analytica’s, the climate change deniers, the alt-right meme machines, the political demagogues. They are the ones who benefit the most from free speech, not the experts, not the scientists, not the academics, not those individuals who are willing to do some homework and engage in good faith with an open mind.

So, to those who care about facts, evidence and the power of rational discourse to help us arrive at the truth, I say: WAKE UP. We’re losing, and with us, truth and humanity. The mongers of misinformation and agents of bad faith are driving us into the dirt, and we’re down here tilling the very soil that allows the weeds to flourish.

Shut it down

Free speech has failed us. That’s why I think The Conversation is justified in banning certain forms of well established misinformation on its site, whether it’s delivered by trolls or people who are misguided enough to believe it.

The Conversation as a website is predicated on the importance of expertise. It only publishes articles by qualified academics, and only allows them to write on areas in which they are experts. It encourages a diversity of views and debate amongst its authors. I know, because (full disclosure) I used to work there, editing the science and technology section. True to its name, The Conversation also wants to encourage discussion and debate amongst readers. But it is in no way obliged to give a platform to anyone. It is able to determine the standards of discourse in its own domain.

So if the “conversation” in the comments section slips well outside the bounds of respect for evidence, reason or good faith discourse that The Conversation seeks to promote, then it ought to be allowed to disqualify it. It’s not like the readers can’t spread their views on other platforms with lower standards. Sadly, there’s an abundance of those around these days. Freedom of speech doesn’t require everyone to allow just anyone to walk into in their garden and plant whatever they want.

Freedom of speech doesn’t require everyone to allow just anyone to walk into in their garden and plant whatever they want.

That said, I am convinced that we need some forums where free speech can operate in an expansive way. At the moment, I think universities are the best candidates, which is why I resist the deplatforming of academics or speakers on campus, no matter how controversial their views. Universities need to get better at managing this, because they’re one of the last bastions of truly open enquiry.

But I’m increasingly coming to believe that we need to get real about the failures of free speech in many public forums, and fight back against those who would pollute discourse with bad faith. I’m not convinced we should go as far as Herbert Marcuse, who argued that civil discussion was futile, so all that’s left is violence. But I do think we can’t maintain the naive position that “more speech is always a good thing.”

The paradox of free speech

I’ll be the first to say I don’t know what to do. But I have some initial ideas. I suspect there’s a short term and a long term solution. In the long term, we want to rehabilitate public discourse by encouraging good faith. That’s a decades long project, and one that will require the rebuilding of a great deal of social capital that has been degrading over decades.

This is not necessarily a project that is conducted through rational discourse itself. Rather, it’s something that requires constructive social discourse. It requires relationship building, the restoration of trust, the separation of belief from identity, and the buttressing of social norms that make rational discourse a possibility.

And in the short term, I’m increasingly open to shutting down speech that is not only conducted in bad faith, but is polluting discourse itself, so encouraging more bad faith. The problem of dealing with speech that corrupts speech is related to Karl Popper’s famed “paradox of tolerance.” If we believe that tolerance is good, how should we treat those who are intolerant? If we tolerate them, won’t they end tolerance? And if we don’t tolerate them, doesn’t that make us intolerant?

The solution to this paradox is elegantly expressed by Peter Godfrey-Smith and Benjamin Kerr in an article published on – ironically enough – The Conversation. Godfrey-Smith argues that in order to protect “first-order” of tolerance of individual actions – say, certain religious practices or having a homosexual relationship – means we must be “second-order” intolerant of actions that are themselves intolerant of these actions, and it’s in no way contradictory or hypocritical to do so. That’s why we have anti-discrimination laws that are explicitly intolerant of intolerance.

Similarly, in order to protect the power of free speech to help seek the truth, I think we need to be more intolerant of speech that subverts the very possibility of speech to seek the truth. Crucially, that doesn’t mean shutting down speech by people who are just ignorant or wrong. What it does mean is shutting down bad faith speech that muddies the waters, that spreads misinformation, that threatens or coerces, or that exploits known psychological biases to mislead.

in order to protect the power of free speech to help seek the truth, I think we need to be more intolerant of speech that subverts the very possibility of speech to seek the truth.

There’ll be a price to shutting down certain types of discourse in some forums. Some legitimate speech may be hampered. But if the price of not doing it is more polluted discourse, more bad faith, more wars, more Brexits, more Trumps, and a world that is more than 4 degrees warmer, then I know which side of the trade-off I prefer.

I still believe in the potential of free speech to seek the truth. I still believe it ought to be practiced in some forums. I still believe it’s something worth fighting to enable and preserve. But I think you only need to look at the last two decades – and speculate about the two decades to come – to realise that our current approach to free speech has failed. And the stakes are high.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

LGBT…Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio The Ethics Centre 8 OCT 2019

Most people believe it is a good idea to help out others in need, if and when we can. If someone falls over in front of us, we usually stop to see if they need a hand or to check if they are OK.

Donating to charity is also considered to be helping others in need, but we may not always see the person we are helping in this case. Even so, charitable donations are viewed as praiseworthy in our society. We receive a sticker for placing spare change into a coin collection tin, and our donations are tax deductible.

Yet most people see donating to charity as a ‘nice thing to do’, but perhaps not a ‘duty’, obligation or requirement. In Kantian terms, it is ‘supererogatory’, meaning that it is praiseworthy, but above and beyond the call of duty.

However, Peter Singer defends a stronger stance. He argues that we should help others – however we can. All of us. This may look different for different people. It could involve donating money, time, signing petitions, or passing along old clothes to those who need them, for example.

If we can help, then we should, Singer argues, because it results in the greatest overall good. The small efforts of those who can do something greatly reduce the pain and suffering of those who need welfare.

In order to illustrate this argument, Singer provides us with a compelling thought experiment.

The ‘drowning child’ thought experiment

From his 1972 article, ‘Famine, Affluence, and Morality’, Singer starts with a basic principle:

“if it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.”

This seems reasonable. He backs this claim up with the following concrete example:

“An application of this principle would be as follows: if I am walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning in it, I ought to wade in and pull the child out. This will mean getting my clothes muddy, but this is insignificant, while the death of the child would presumably be a very bad thing”.

Obviously, we agree, we should save the child from drowning, even if it comes with the inconvenience and cost of ruining some of our favourite, expensive clothes and shoes. The moral ‘weight’ of saving a life far outweighs the cost in this scenario.

Yet, Singer extends this claim even further.

He notes that if we agree with this principle, then what follows from it is quite radical. If we act on the idea that we should always prevent very bad things from happening, provided we are not sacrificing anything too costly to ourselves, this makes a moral demand upon us.

The biggest implication is that, for Singer, it does not matter whether the drowning child is right in front of us, or in another country on the other side of the world. The principle is one of impartiality, universalizability and equality.

I can easily donate the cost of a new pair of shoes to a respected charitable organisation and save a life with the funds from that donation. In the same way as a moral agent would wade into the pond to rescue the drowning child, we can make some relatively small effort that prevents a very bad thing from occurring.

The ‘very bad thing’ may be that a child in a developing country starves to death or dies because their family cannot afford the treatment for a simple disease.

The expanding moral circle

Now, even for those in favour of charitable giving, some may argue that our duty to help does not extend beyond national borders. It is easier to help the child ‘right in front of us’, they may say. Our moral circle of concern includes our family and friends, and perhaps our fellow Australians.

But I am convinced by Singer’s argument that we ought to expand our moral circle of consideration to those in other countries, to those who live on planet Earth with us. The moral obligation to alleviate suffering has no borders.

And we are now most certainly ‘global citizens’. Thanks to our technology and growing awareness of what occurs around the globe, we have outgrown a nationalistic model and clearly inhabit an international world.

Global Citizens

In his 2002 book, One World: the ethics of globalisation, Singer supports the notion of the global citizen which views all human beings as members of a single, global community. The global citizen is someone who recognises others as more similar to rather than different from oneself, even while taking seriously individual, social, cultural and political differences between people.

In a pragmatic sense, global citizens will support policies that extend aid beyond national borders and cultivate respectful and reciprocal relationships with others regardless of geographical distance or other differences (such as those related to race, religion, ethnicity, disability, sexuality, or gender identification).

For a long time now, Singer has also been pointing out that we are all responsible for important issues that are affecting each and every one of us. Back in 1972, he claimed, “unfortunately, most of the major evils – poverty, overpopulation, pollution – are problems in which everyone is almost equally involved.”

And, with our technology, media and the 24 hour news cycle, we are now confronted with the pain and suffering of those distant others in ways that ensure they are immediately present to us. We can no longer claim ignorance of the help required by others, as social media brings their images and pleas directly to our handheld devices.

So, do we have an obligation to alleviate suffering wherever it is found? Does this obligation extend beyond national borders? Should we do what we can to prevent very bad things from happening, provided in doing so we do not have to sacrifice anything too drastic or comparable? (for instance, we need not reduce ourselves to the levels of poverty of those we seek to assist in doing so).

If you answered yes, then you may already think of yourself as a global citizen.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Agape

How many people do you think we can love? Can we love everyone? Can we love everyone equally? The answers to these questions obviously depend on what the nature of this kind of love is, and what it looks like or demands of us in practice.

“Love is all you need”

Agape is a form of love that is commonly referred to as ‘neighbourly love’, the love ethic, or sometimes ‘universal love’. It rests on the idea that all people are our ‘brothers and sisters’ who deserve our care and respect. Agape invites us to actively consider and act upon the interests of other people, in more-or-less the same proportion as you consider (and usually act upon) your own interests.

We can trace the concept back to Ancient Greece, a time in which they had more than one word to describe various kinds of love. Commonly, useful distinctions can be made between eros, philia, and agape.

Eros is the kind of love we most often associate with romantic partners, particularly in the early stages of a love affair. It’s the source of English words like ‘erotic’ and ‘erotica’.

Philia generally refers to the affection felt between friends or family members. It is non-sexual in nature and usually reciprocal. It is characterised by a mutual good will that manifests in friendship.

Although both eros and philia have others as their focus, they can both entail a kind of self-interest or self-gratification (after all, in an ideal world our friends and lovers both give us pleasure).

Agape is often contrasted to these kinds of love because it lacks self-interest, self-gratification or self-preservation. It is motivated by the interest and welfare of all others. It is global and compassionate, rather than focussed on a single individual or a few people.

Another significant difference between agape and other forms of love is that we choose and cultivate agape. It’s not something that ‘happens’ to us like becoming a friend or falling romantically in love, it’s something we work toward. It is often considered praiseworthy and holds the lover to a high moral standard.

Agape is a form of love that values each person regardless of their individual characteristics or behaviour. In this way it is usually contrasted to eros or philia, where we usually value and like a person because of their characteristics.

Agape in traditional texts

The concept of agape we now have has been strongly influenced by the Christian tradition. It symbolises the love God has for people, and the love we (should) have for God in return. By extension, if we love our ‘neighbours’ (others) as we do God, then we should also love everyone else in a universal and unconditional manner, simply because they are created in the likeness of God.

The Jesus narrative asks followers to act with love (agape) regardless of how they feel. This early Christian ethical tradition encourages us to “love thy neighbour as thyself”. In the Buddhist tradition K’ung Fu-tzu (Confucius) similarly says, “Work for the good of others as you would work for your own good.”

Another great exponent of this ethic of love is Mahatma Gandhi who lived, worked, and died to keep this transcendent idea of universal love alive. Gandhi was known for saying, “Hate the sin, love the sinner”.

Advocates for non-violent resistance and pacifism that include Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and John Lennon and Yoko Ono also refer to the power of love as a unifying force that can overcome hate and remind us of our common humanity, regardless of our individual differences.

Such ideology rests on principles that are resonant with agape, urging us to love all people and forgive them for whatever wrongs we believe they have committed. In this way, agape sets a very high moral standard for us to follow.

However, this idea of generalised, unconditional love leaves us with an important and challenging question: is it possible for human beings to achieve? And if so, how far may it extend? Can we really love the whole of humanity?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to deal with people who aren’t doing their bit to flatten the curve

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Now is the time to talk about the Voice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 18 SEP 2019

I recently came across a quote from philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau, talking about what it means to live well:

“To live is not to breathe but to act. It is to make use of our organs, our senses, our faculties, of all the parts of ourselves which give us the sentiment of our existence. The man who has lived the most is not he who has counted the most years but he who has most felt life. Men have been buried at one hundred who have died at their birth.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I found myself nodding sagely along as I read. Because life isn’t something we have, it’s something we do. It is a set of activities that we can fuse with meaning. There doesn’t seem much value to living if all we do with it is exist. More is demanded of us.

Rousseau’s quote isn’t just sage; it’s inspiring. It makes us want to live better – more fully. It captures an idea that moral philosophers have been exploring for thousands of years: what it means to ‘live well’ – to have a life worth living.

Unfortunately, it also illustrates a bigger problem. Because in our current reality, not everyone is able to live the way Rousseau outlines as being the gold standard for Really Good LivingTM.

This is a reality that professionals working in the aged care sector should know all too well. They work directly with people who don’t have full use of their organs, their faculties or their senses. And yet when I presented Rousseau’s thought to a room full of aged care professionals recently, they felt the same inspiration and agreement that I’d felt.

That’s a problem.

If the good life looks like a robust, activity-filled life, what does that tell us about the possibility for the elderly to live well? And if we don’t believe that the elderly can live well, what does that mean for aged care?

If you have been following the testimony around the Aged Care Royal Commission, you’ll be aware of the galling evidence of misconduct, negligence and at times outright abuse. The most vulnerable members of our communities, and our families, have been subject to mistreatment due in part to a commercial drive to increase the profitability of aged care facilities at the expense of person-centred care .

Absent from the discussion thus far has been the question of ‘the good life’. That’s understandable given the range of much more immediate and serious concerns facing the aged care sector, but it is one that cannot be ignored.

In 2015, celebrity chef and aged care advocate Maggie Beer told The Ethics Centre that she wanted “to create a sense of outrage about [elderly people] who are merely existing”. Since then she has gone on to provide evidence to the Royal Commission, because she believes that food is about so much more than nutrition. It’s about memory, community, pleasure and taking care and pride in your work.

Consider the evidence given around food standards in aged care. There have been suggestions that uneaten food is being collected and reused in the kitchens for the next meal; that there is a “race to the bottom” to cut costs of meals at the expense of quality, and that the retailers selling to aged care facilities wildly inflate their prices. The result? Bad food for premium prices.

We should be disturbed by this. This food doesn’t even permit people to exist, let alone flourish. It leaves them wasting away, undernourished. It’s abhorrent. But what should be the appropriate standard for food within aged care? How should we determine what’s acceptable? Do we need food that is merely nutritious and of an acceptable standard, or does it need to do more than that?

Answering that question requires us to confront an underlying question:

Do we believe aged care is simply about providing people’s basic needs until they eventually die?

Or is it much more than that? Is it about ensuring that every remaining moment of life provides the “sentiment of existence” that Rousseau was concerned with?

When you look at the approximately 190,000 words of testimony that’s been given to the Royal Commission thus far, a clear answer begins to emerge. Alongside terms like ‘rights’, ‘harms’ and ‘fairness’ –which capture the bare minimum of ethical treatment for other people – appear words such as ‘empathy’, ‘love’ and ‘connection’. These words capture more than basic respect for persons, they capture a higher standard of how we should relate to other people. They’re compassionate words. People are expressing a demand not just for the elderly to be cared for, but to be cared about.

Counsel assisting the Royal Commission, Peter Gray QC, recently told the commission that “a philosophical shift is required, placing the people receiving care at the centre of quality and safety regulation. This means a new system, empowering them and respecting their rights.”

It’s clear that a philosophical shift is necessary. However, I would argue that what’s not clear is if ‘person-centred care’ is enough. Because unless we are able to confront the underlying social belief that at a certain age, all that remains for you in life is to die, we won’t be able to provide the kind of empowerment you felt reading Rousseau at the start of this article.

There is an ageist belief embedded within our society that all of the things that make life worth living are unavailable to the elderly. As long as we accept that to be true, we’ll be satisfied providing a level of care that simply avoids harm, rather than one that provides for a rich, meaningful and satisfying life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jelaluddin Rumi

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: bell hooks

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 22 AUG 2019

What was your first lesson in courage? The first time someone told you to be brave – or explained to you that fear was something to be overcome, not something that should control you?

I can’t remember the very first moment I encountered the idea of courage, but the first I can remember – and the one that has stayed with me the longest – is this: “being brave doesn’t mean we looking for trouble.”

It is, of course, from Disney’s The Lion King. Mufasa, moments after saving his son, Simba, from ravenous hyenas, chastises his boy for putting himself and his friend in danger.

Simba’s journey in The Lion King is really a treatise on courage. From a reckless, thrill-seeking child, Simba loses his father and, believing himself responsible, flees from the social judgement that might bring.

Simba takes his father’s lesson too far: he doesn’t look for trouble, but when it finds him, he runs from it. He lives as an exile in a hedonistic paradise. Comfortable, apathetic, safe. For all his physical prowess, Simba is a coward.

Of course, by the end of the film Simba has found courage. He accepts his identity as the true king, admits his shame publicly, defeats Scar (his true enemy) and takes his place in the circle of life, complete with staggering musical accompaniment.

As well as having a soundtrack that’s jam-packed with bangers, it turns out the Lion King has a strong philosophical pedigree.

Courage as a virtue

The Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that courage was as virtue – a marker of moral excellence. More specifically, it was the virtue that moderated our instincts toward recklessness on one hand and cowardice on the other.

He believed the courageous person feared only things that are worthy of fear. Courage means knowing what to fear and responding appropriately to that fear.

For Aristotle, what mattered isn’t just whether you face your fears, but why you face them and what it is that you fear.

There is something important here. Your reasons for overcoming fear matter. They can be the difference between courage, cowardice and recklessness.

For instance, in Homer’s Iliad, the Trojan prince Hector threatens to punish any soldier he sees fleeing from the fight. In World War I, soldiers who deserted were executed.

Were these soldiers courageous? The only reason they risk death from the enemy is because they’re guaranteed to be killed if they don’t. The fear of death is still what drives them.

More courageous, says Aristotle, is the soldier who freely chooses to fight despite having no personal reason to do so besides honour and nobility. In fact, for Aristotle, this is the highest form of courage – it faces the greatest fear (death) for the most selfless reason (the nation).

Of course, Aristotle was an Ancient Greek bloke, so we should take his prioritising of military virtue with a grain of salt. Is death at war really to be so highly prized?

For one thing, in a culture like Ancient Greece or Troy, the failure to be an excellent warrior would be met with enormous dishonour. How many soldiers went to war for fear of dishonour? Is dishonour something to be rightly feared? And if so, whose dishonour should we fear?

Surely not that of a society whose moral compass prioritises victory over justice – risking your life to support a cause like that is reckless.

If courage means fearing dishonour from those who are morally corrupt, then a courageous enemy is worse than a cowardly one. Courage becomes like a superpower – making some people into heroes and others villains.

But there’s a deeper reason to doubt Aristotle’s idea of the highest courage. Whilst most of us do fear death, it’s not clear that it’s the thing we fear most. Even if we do fear death, we have a range of different reasons for doing so.

Our deepest fears

Perhaps my most visceral fear is of drowning. The thought of it is enough to make me feel short of breath. Perhaps that’s because of an experience when I was younger – when I was overseas I learned that my Dad nearly drowned. It was perhaps the first time I really had to come to grips with the fact he was mortal – and so was I – and all that I loved.

Today, I fear death because it would mean never seeing my children grow up. Never holding them one last time. Seeing my son’s first days at school. Hearing my daughter’s first words.

Worse, I wouldn’t be sure that they were safe and flourishing. If someone could guarantee that, perhaps I’d be less fearful of death. It’s not the death I fear; it’s what it represents: an incomplete life, failed commitments, unending love brought to a close.

Aristotle didn’t consider courage in the face of existential anxieties like these. What does it mean to live courageously in a world where all our loves, passions and projects expose us to pain and loss? To live is to have a nerve constantly exposed to the world – always vulnerable to suffering.

The French psychoanalyst and philosopher Anne Dufourmantelle argues that risk is an inherent part of living fully in the world. Risk-free living, she argues, is not living at all. Courage is as much about living despite knowing the exposed nerve of love and passion could trigger chest-tightening pain at any moment.

Yet so often we close ourselves from the world to keep ourselves safe. We self-censor not because we think we might be wrong, but because we fear upsetting the wrong person. We withdraw from relationships because we don’t want to be the one to take the leap. We tell ourselves stories in the shower of all the things we could do – could be – if only the world let us.

Existentialist philosophers have a name for this kind of self-deception: bad faith – a kind of failure to engage with the world as it really is and accepting ourselves as we are and as we could be.

Too often we think of courage purely as facing up to our fears. What that misses is how deeply connected our fears are with deeper beliefs about who we are, who we want to be, who we love and what we wish the world was.

A courageous truth

Maybe the truth of courage is that it’s all about truth. It’s about looking reality in the face and having the force of will not to turn away, despite the pain, the unpleasantness and the risk.

Maybe it’s about looking for long enough to see the joy in the pain; the beauty in the ugliness and the comfort that lies in the little risks we take every day.

Perhaps it’s only then we can know what’s worth dying for – and what’s worth living for. Certainly, Dufourmantelle gives us some hope of this. In 2017, she died in rough seas off the coast of France, having swum out to rescue two children caught in the surf.

The children survived, but how many of us would have dived in? How many would have hoped for a lifeguard? A stronger swimmer? For the children to rescue themselves?

I want to encourage you to think: are there rough waters you’re not jumping into for fear of the waves? Do you tend to dive in without counting the costs?

Dr Matt Beard was the host of The Ethics of Courage, alongside Saxon Mullins and Benjamin Law at The Ethics Centre on 21 August. This is a transcript of his opening address.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Pragmatism

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

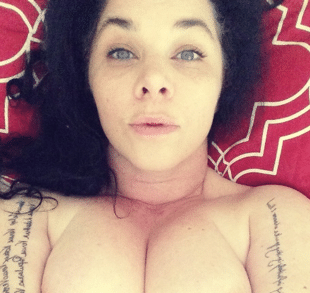

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Amy Gray 22 AUG 2019

The continuing moral panic over women’s naked selfies is fundamentally misframed. By emphasising the potential for women to be made victims, we ignore the ways a woman’s body can be an expression of power.

According to the prevailing moral panic of the day, young women take naked selfies in order to please others and not themselves. This, we’re told, leaves them vulnerable to exploitation because women must always be vulnerable.

It’s as though the only mystery afforded to women is not their thoughts or talents but what lies underneath their clothes. Go no deeper than the skin. Deny any complexity that might present her as a human with needs separate from what men may want.

This seems to be a narrative we teach teenagers. My daughter was taught that not only was there no legal recourse for photos shared without consent (untrue) but that the effects on women were so catastrophic that they should never send a naked photo (also, untrue). This happened on International Women’s Day, as if to remind us of our to-do list.

Inevitably, they learn what we teach. When I worked with teens on a short film, they told me how boys pestered every girl in their class for naked selfies. The girls didn’t even think it was sexual; more of a competitive collection like Pokemon Go but for undeveloped breasts. The requests were thought of as frustrating but normal, because “that’s just how they are”. Yet despite the mundanity of such a frequent request, the same teens sincerely believed leaked selfies would hound a woman to her grave.

Naked selfies carry many gendered clashes. I’ve always gasped at the difference between gendered aesthetics: I’ll rush to clean my room, groom and put on makeup before getting into an appropriate outfit of sorts before painstakingly composing shots; men just send a close-up photo of their cock jutting from a thicket of pubes.

It’s an effective example of the differences between the male and female gaze. A woman prepares because she is conditioned to know what men find attractive and that she is expected to deliver that. Men, conditioned to expect immediate access regardless of merit, put almost zero thought into their selfies. In the rare case they do, they project an image of themselves they want to see, rather than women who mirror what men want to see.

This positioning reinforces the power dynamic in heterosexual sexting. Men expect entertainment and women entertain at threat of exposure (also expected).

But why does the power lie with men?

On image sharing site Imgur, men enthusiastically share photos of naked women, even creating themed days for certain ‘types’ of women. But the images presented reflect the male gaze – photos taken of women, not by women.

Generally, whenever women posted selfies on Imgur, sexualised or not, she was immediately inundated with caustic remarks to stop being an exhibitionist (a polite euphemism for attention whore). That these are the same men who think nothing of going into a woman’s DMs to ask for naked photos is just another layer to it all. There is a clear mode of production, where women are the object and men remain in control of when and how they are seen. This is where the phrase “tits or get the fuck out” shows its intent: give us the body parts, not the entire body.

Perhaps this is because it is easier to sexually appreciate an object that has not been humanised or seen as an individual. When things are anonymised or presented in such a volume that they lose all semblance of individuality, they become an object that can be appreciated or abused without shame.

The power balance still rests with men – naked women are objects men readily expect, and demand to be presented in anticipated service of them. In this position of power, men expect women to arouse them, yet rarely consider whether women are aroused. Amazingly, we rarely discuss whether women find joy or pleasure in taking naked selfies, whether for themselves or others because we can’t move past women’s seemingly inevitable victimhood.

I’ve taken naked selfies for well over a decade. I first worried if photos might leak but, somewhat ironically, this concern has disappeared as I do more work in public. In Doing It: Women Tell the Truth About Great Sex, an anthology about sex, I wrote of how selfies can become graphic storytelling that not only builds intimacy but also an understanding of my sexuality and my sexual aesthetic pleasure. It is a power I never want to give up, so the book also contains a naked photo of me I had taken for a lover. It is a deliberate attempt to interrupt the means of production and also claim space within my sexuality, one that is defined by myself, not others.

When the photo was republished (with consent) by SBS, I wrote that “this is not some wishy-washy Stockholm syndrome masquerading as empowerment – there is ferocity in my choice”. It remains true today. By claiming my agency as an individual who feels pleasure and expression, I realise that confidence is not only crucial for my personal survival under patriarchy framed solely for men, but it is also a political act I can define as I choose. It makes me aware that my body, choices and actions are decided by me without reference to others’ expectations and that I contain greater complexity the roles of servant or victim that society allows.

Around this time, Mia Freedman wrote an article entitled ‘The conversation we have to have: Stop taking nude selfies’. Promoting the article on Twitter, Freedman wrote “taking nude selfies is your absolute right. So is smoking. Both come with massive risks.” In response, I took another naked selfie, but this time with a cigarette draped from my mouth and ‘fuck off’ written on my chest in black lipstick. I posted it everywhere without care because – again – my body, choices and actions are decided by me. I made the choice that and every day is that I will not have victims presented as complicit in their abuse. Because the fault will always be with the abuser, not the abused.

An act of power

Despite their conflicting emotions, publishing naked selfies taken in either arousal or anger are fearsome in their power. They are as much a rejection of victimhood as they are an opportunity for retribution. People can try to weaponise my body against me, but I will do it first and use it against them because I know its power.

This is why patriarchal structures and men condition women into submissive disempowerment. Women’s bodies are defined narrowly as vessels for pleasures and service for others, not ourselves. Such narrow and compliant definitions intentionally belie the power and complexity we contain.

Stories abound throughout history of the malevolent power of women’s bodies, so profound was male unease surrounding bloods and births. Women were told their vaginas ruined ship rope or their menstruation damned success. This was an admission women’s bodies were terrifying in their otherness but was also an excuse to contain them to the home rather than out in the community where they might gain power or control.

But history tells us many women believed in the power of their bodies. Balkan women would stand out in the fields, flashing their vaginas to the sky to quell thunderstorms. The Finnish believed in the magic of harakointi, using their exposed bodies to bless or curse on whim. Sheela-na-gigs (carvings of women often found in European architecture) embraced their power by spreading their labia, not to please or welcome men, but scare off evil. Women would lift their skirts to make others laugh in feasts for Roman gods and goddesses or lure lovers. More recently, women have exposed their bodies to protest petroleum in Nigeria or civil war in Liberia in acts of political, angry anasyrma.

Reframing the dialogue

The continuing moral panic over women’s naked selfies is fundamentally misframed. Women are presented as passively-defensive vessels in a state of perpetual victimhood. We are tasked with hiding our shameful-yet-coveted nakedness from people who expect to see us but only under their strict conditions.

A truer representation is that power exerts in all manners of life, including how we sexually communicate as equal, consenting partners. The moral panic should focus on when power corrupts that balance and how to correct it, not how to maintain the same corruption.

Join us as on 18 September for an an intimate conversation with Sexologist, Nikki Goldstein and art curator Jackie Dunn to unwrap the ethical dimensions of being nude. Get your ticket to The Ethics of Nudity here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The power of community to bring change

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Absolutism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We can help older Australians by asking them for help

Join our newsletter

BY Amy Gray

Amy Gray is a Melbourne-based writer interested in feminism, popular and digital culture and parenting. follow her on twitter @_AmyGray_

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 30 JUL 2019

Until last week, you would have been forgiven for thinking a meme couldn’t trigger fears about international security.

But since the widespread concerns over FaceApp last week, many are asking renewed questions about privacy, data ownership and transparency in the tech sector. But most of the reportage hasn’t gotten to the biggest ethical risk the FaceApp case reveals.

What is FaceApp?

In case you weren’t in the know, FaceApp is a ‘neural transformation filter’.

Basically, it uses AI to take a photo of your face and make it look different. The recent controversy centred on its ability to age people, pretty realistically, in just a short photo. Use of the app was widespread, creating a viral trend – there were clicks and engagements to be made out of the app, so everyone started to hop on board.

Where does your data go?

With the increasing popularity comes increasing scrutiny. A number of people soon noticed that FaceApp’s terms of use seemed to give them a huge range of rights to access and use the photos they’d collected. There were fears the app could access all the photos in your photo stream, not just the one you chose to upload.

There were questions about how you could delete your data from the service. And worst of all for many, the makers of the app, Wireless Labs, are based in Russia. US Minority Leader Chuck Schumer even asked the FBI to investigate the app.

The media commentary has been pretty widespread, suggesting that the app sends data back to Russia, lacks transparency about how it will or won’t be used and has no accessible data ethics principles. At least two of those are true. There isn’t much in FaceApp’s disclosure that would give a user any sense of confidence in the app’s security or respect for privacy.

Unsurprisingly, this hasn’t amounted to much. Giving away our data in irresponsible ways has become a bit like comfort eating. You know it’s bad, but you’re still going to do it.

The reasons are likely similar to the reasons we indulge other petty vices: the benefits are obvious and immediate; the harms are distant and abstract. And whilst we’d all like to think we’ve got more self-control than the kids in those delayed gratification psychology experiments, more often than not our desire for fun or curiosity trumps any concern we have over how our data is used.

Should you be worried?

Is this a problem? To the extent that this data – easily accessed – can be used for a range of goals we likely don’t support, yes. It also gives rise to a range of complex ethical questions concerning our responsibility.

Let’s say I willingly give my data to FaceApp. This data is then aggregated and on-sold in a data marketplace. A dataset comprising of millions of facial photos is then used to train facial recognition AI, which is used to track down political dissidents in Russia. To what extent should I consider myself responsible for political oppression on the other side of the world?

In climate change ethics, there is a school of thought that suggests even if our actions can’t change an outcome – for instance, by making a meaningful reduction to emissions – we still have a moral obligation not to make the problem worse.

It might be true that a dataset would still be on sold without our input, but that alone doesn’t seem to justify adding our information or throwing up our arms and giving up. In this hypothetical, giving up – or not caring – means abandoning my (admittedly small) role in human rights violations and political injustice.

A troubling peek into the future

In reality, it’s really unlikely that’s what FaceApp is actually using your data to do. It’s far more likely, according to the MIT Technology Review, that your face might be used to train FaceApp to get even better at what it does.

It might use your face to help improve software that analyses faces to determine age and gender. Or it might be used – perhaps most scarily – to train AI to create deepfakes or faces of people who don’t exist. All of this is a far cry from the nightmare scenario sketched out above.

But even if my horror story was accurate, would it matter? It seems unlikely.

By the time tech journalists were talking about the potential data issues with FaceApp, millions had already uploaded their photos into the app. The ship had sailed, and it set off with barely a question asked of it. It’s also likely that plenty of people read about the data issues and then installed the app just to see what all the fuss is about.

Who is responsible?

I’m pulled in two directions when I wonder who we should hold responsible here. Of course, designers are clever and intentionally design their apps in ways that make them smooth and easy to use. They eliminate the friction points that facilitate serious thinking and reflection.

But that speed and efficiency is partly there because we want it to be there. We don’t want to actually read the terms of use agreement, and the company willingly give us a quick way to avoid doing so (whilst lying, and saying we have).

This is a Faustian pact – we let tech companies sell us stuff that’s potentially bad for us, so long as it’s fun.

The important reflection around FaceApp isn’t that the Russians are coming for us – a view that, as Kaitlyn Tiffany noted for Vox, smacks slightly of racism and xenophobia. The reflection is how easily we give up our principled commitments to ethics, privacy and wokeful use of technology as soon as someone flashes some viral content at us.

In Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology, Simon Longstaff and I made the point that technology isn’t just a thing we build and use. It’s a world view. When we see the world technologically, our central values are things like efficiency, effectiveness and control. That is, we’re more interesting in how we do things than what we’re doing.

Two sides of the story

For me, that’s the FaceApp story. The question wasn’t ‘is this app safe to use?’ (probably no less so than most other photo apps), but ‘how much fun will I have?’ It’s a worldview where we’re happy to pay any price for our kicks, so long as that price is hidden from us. FaceApp might not have used this impulse for maniacal ends, but it has demonstrated a pretty clear vulnerability.

Is this how the world ends, not with a bang, but with a chuckle and a hashtag?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Should we abolish the institution of marriage?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Big Thinker: Jeremy Bentham

The consequences of our actions are important and we should weigh these up when we consider what we should do.

Some philosophers have taken this idea even further, claiming that outcomes are the only criteria by which the moral worth of an action should be judged.

Jeremy Bentham (1748—1832) was the father of utilitarianism, a moral theory that argues that actions should be judged right or wrong to the extent they increase or decrease human well-being or ‘utility’.

He advocated that if the consequences of an action are good, then the act is moral and if the consequences are bad, the act is immoral.

Central to his argument was a belief that it is human nature to desire that which is pleasurable, and to avoid that which is painful. As a self-proclaimed atheist, he wanted to place morality on a firm, secular foundation. At the beginning of his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Bentham wrote:

“Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do.”

It is because of this emphasis on pleasure that his theory is known as hedonic utilitarianism. But this doesn’t mean we can do whatever we like. Importantly, for Bentham, it is not just one’s own happiness or pleasure that matters.

He notes, “Ethics at large may be defined, the art of directing men’s actions to the production of the greatest possible quantity of happiness.” The moral agent will perform the action that maximises happiness or pleasure for everyone involved.

Can we measure happiness?

Bentham defended an objective form of morality that could be measured in a scientific way. As an empiricist, he came up with a way to ‘weigh’ or quantify pleasures and pains as the consequences of an action.

He called this set of metaphorical scales the ‘hedonic’ or ‘felicific calculus’, allowing a rational moral agent to think through, and then act on, the right – moral– thing to do.

The ‘hedonic calculus’ is used to measure how much pain or pleasure an action will cause. It takes into consideration how near or far away the consequence will be, how intense it will be and how long it will last, if it will lead on to further pleasures or pains, and how certain we are that this consequence will result from the action under consideration.

The moral decision maker is meant to act as an ‘impartial observer’ or ‘disinterested bystander’, to be as objective as they can be and choose the action that will produce the greatest amount of good.

Do the ends justify the means?

There are some practical applications of utilitarianism. For instance, if you’re a politician in charge of making decisions that effects a large group of people, you should act in a way that maximises happiness and minimises pain and suffering. In this way, the hedonic calculus supports a welfare system that reduces unfair outcomes by redistributing wealth and resources.

Yet there are tricky aspects to the theory that must also be considered. Contemplate the saying “the ends justify the means” – what immoral action may be justified by (predicted) good consequences?

This is where ethicists start to ask tricky questions like, ‘would you kill Hitler?’. And if you answer ‘um, sure, because that will prevent a LOT of deaths’, then they will ask, ‘would you kill baby Hitler?’. You can see how it starts to get complicated.

Bentham’s theory relies on accurately predicting outcomes, and as such holds the moral agent accountable for moral luck. One might intend to do a good deed, but if an unpredictable result occurs, leading to a negative outcome, then they are still to be held morally responsible.

Visit Bentham in London

His theories were popular at University College London (UCL), where Behtham’s followers called themselves ‘Benthamites’. Among these were James Mill and his son, John Stuart Mill. J. S. Mill (1806 –1873) worried that Bentham’s theory was too hedonistic as it did not prioritise the ‘higher’ pleasures of the intellect. He added the criteria of ‘quality’ to Bentham’s calculus in order to create ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ quality pleasures.

A final, fun fact: Bentham willed his body to be preserved and displayed at UCL after his death. A visit to the philosophy department will see him in a busy hallway, merrily seated in a glass fronted mahogany case.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture