The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 9 JUL 2019

Dr Simon Longstaff, Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, opened the recent AGSM Professional Forum: Ethical Leadership in an Accelerating World by acknowledging today’s leaders are confronted with a pace of change that is increasingly rapid, complex and deep in its implications.

They are grappling with multiple dynamic forces as they make strategic business decisions, uncover new market opportunities, and maintain their sense of purpose.

And, as we move into the Age of Purpose, they must measure up to the moral expectations of their employees, stakeholders and the public – while building trust in an increasingly sceptical environment.

As one of Australia’s leading ethicists and philosophers, Dr Longstaff said he believes ethics need to be intrinsic within leaders, especially in a time where civilisation is going through enormous change. And this starts with leaders in the boardroom. “I’d like to reframe leadership itself as an ethical practice. You can’t just add ethics into leadership. If that’s what you’re doing, you’ve misunderstood what leadership is,” he said.

Strengthening the decision-making muscle

Historically, decision-making in organisations has been heavily regulated – and Dr Longstaff says that makes it due for an overhaul. Only then can more robust ethical practices flourish throughout organisations.

“For 30 years or more, leaders have been trying to manage the rate, complexity and depth of change through the exercise of control,” said Dr Longstaff. “In this country the most prolific regulators are not in parliaments or at APRA. They’re in the boardrooms of Australia.”

He says the system has been so finely meshed that no one can choose to do anything wrong. And as a result we’ve begun to create new forms of systemic risk.

“Inside corporations, there are measures designed to make it safe. But if you create a world in which no one can choose to do anything wrong, it also means no one can choose to do anything right,” said Dr Longstaff. “If you don’t choose – you comply. And like any skill, if this muscle isn’t used and flexed, it withers away.”

This systemic impact was most clearly demonstrated in the findings of the recent Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry. The findings uncovered the implications of inaction and the way leadership behaviour can detrimentally impact stakeholder sentiment and damage trust in an organisation.

“In many cases of a compliant culture, when asked why a certain decision has been made, the answer is ‘that’s the way things have always been done’,” said Dr Longstaff. “But the fact we can do something doesn’t mean we should do it. To do so is a sign of a cultural failure, where ethical restraint should have been exercised.”

This is what Dr Longstaff calls ‘unintended negative strategic effect’: Something that can only be rectified by progressive and collaborative leaders.

“People are inherently good,” he said. “Leaders don’t wake up thinking ‘today I’m going to see how much hypocrisy I can engage in’. They are susceptible to the greater threat of unthinking custom and practice. And this must change,” he said.

Leading with moral courage and strategic vision

To create more ethical practices, Dr Longstaff suggests leaders guide their organisations through a process of ‘constructive subversion’ – to break the cycle of ‘going with the flow’ and embedding reflective practice within its culture.

“To subvert unthinking custom and practice, decision-making processes need to come back to the notion of purpose, values and principles,” says Dr Longstaff.

An organisation must have the right intent if it is to achieve its goals. To manage this, Dr Longstaff says leaders need these three key qualities:

- Moral courage – “Leaders need to have courage at the right time in the right way to offer the practice and skills to subvert unthinking.”

- Imagination – “Great leaders can imagine what it’s like to be somebody else, whether friend or foe, and understand how they see the world.”

- Strategic vision – “Leaders need the capacity to invent or discover inflection points – knowing when it’s time to action significant change.”

If leaders can set an organisation’s intention to realise its purpose-led potential, then their people can exercise their own discretion once they adopt this belief. This breaks the cycle of unthinking practice that leads to distrust from stakeholders and shareholders.

“Trust is not hard to build or sustain – there’s no real mystery about it. It’s created when individuals or organisations can declare publicly ‘this is who we are and this is what we stand for’ and act in a manner that is consistent with that’,” said Dr Longstaff.

In his keynote’s conclusion, Dr Longstaff came back to purpose and the existing structures that are in need of an overhaul.

“What is the purpose of a bank? A corporation? A market? Limited liability? All of them have purposes – and almost all of these have been forgotten,” said Dr Longstaff.

“As a society of citizens and colleagues, when we think about ethical leadership, we have to ask ourselves what we want and what will we settle for? A world of control, compliance and surveillance? Even if that was to work, would it diminish who we are as human beings?”

This article was originally published by UNSW, republished with permission.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Power play: How the big guys are making you wait for your money

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Volt Bank: Creating a lasting cultural impact

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

If you condemn homosexuals, are you betraying Jesus?

If you condemn homosexuals, are you betraying Jesus?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 3 JUL 2019

The controversy surrounding Israel Folau’s Instagram posts has tended to focus on questions of free speech, religious freedom and employers’ rights. But I want to ask a deeper question: is Folau’s position consistent with the teachings and example of Christianity’s founder, Jesus of Nazareth?

In thinking about how one might answer this question, I make the following assumptions:

- that, as the incarnation of the divine, Jesus was incapable of error;

- that Jesus’s life and teachings are the ultimate source of authority for Christians;

- that the words and deeds of Jesus, as recorded in the four canonical Gospels, take precedence over those of any other theologian or interpreter (including Paul the Apostle); and

- that the New Testament has priority over the Old Testament ― to the extent that there is any disagreement.

So, what is the essence of Jesus’s life and teaching as revealed in the Gospels? Traditionally, the focus has been on Jesus’s offer of unconditional love and the associated blessing of healing ― both physical and spiritual (the latter through forgiveness of sins).

Jesus does not present himself as breaking with Judaism. He says explicitly that he has not come to overturn the Mosaic Law of his Jewish forebears, but to bring it to its fulfilment, to reveal its essence. On two occasions ― during the Sermon on the Mount and at the Last Supper ― Jesus speaks directly of the core principles on which the Torah is founded. On the earlier occasion, Jesus explicitly states that all of the law is expressed in the two “greatest” commandments: to love God with all one’s heart; to love one’s neighbour as oneself.

However, in the Gospel of John, Jesus goes one step further. John writes that, at the Last Supper, Jesus presents to his immediate disciples a final encapsulation of all his teaching. Affirming his direct connection with the Father, telling them that he is to ascend to heaven but will send a guide in the form of the Holy Spirit, Jesus issues his disciples with a new commandment. This is what John (13:33-35) reports Jesus to have said:

Whither I go, ye cannot come; so now I say to you. A new commandment I give unto you, That ye love one another; as I have loved you, that ye also love one another. By this shall all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye have love one to another.

Unlike the great commandment, with its appeal to the self-love of each person, the new standard for agape (the non-erotic love one bears for another) is to be Jesus’s love for his disciples ― his friends ― and, presumably, for humanity at large.

If the claims of Christians are to be accepted, then Jesus’s new commandment is not a mere act of prophecy, no matter how inspired. It is not an interpretation of a revelatory experience. If you accept the Gospel of John (as I think Christians do), then Jesus has uttered a direct commandment from God; inscribed not on stone but in the hearts and minds of those present. Jesus’s new law is to “love one another as I have loved you.” How then does Jesus love others?

First, each of the Gospels present Jesus as loving unconditionally. Not once does he set a threshold to be crossed before he bestows his love. He heals people without requiring them to become his disciples. He forgives without first requiring a renunciation of sin. He may counsel a better life, but does not make that a precondition of his love. Indeed, he specifically cautions “the righteous” to avoid judging others ― to refrain from casting the first stone.

This is not to say that Jesus is indifferent to sin. In common with the Jewish tradition, Jesus recognises sin as a form of ‘moral servitude’, a loss of freedom. However, there is nothing in the Nazarene’s ministry that condemns homosexuals to eternal damnation ― nor anyone else. Jesus even prays for the forgiveness of those who have ordered and undertaken his torture at Calvary.

Most importantly, Jesus does not merely tolerate those whom others hold in contempt ― he cosies up to them. He touches them. He shares meals with them. He defies the rituals and customs of ‘purity’, even those prescribed in the Old Testament. In doing so, Jesus offends the prevailing piety and invites the censure of those who withdraw from all that is deemed to be ‘unclean’.

How, then, does Christianity in our time become a religion so quick to judge and condemn, and so reluctant to love others without qualification? How do Christians, like Israel Folau, come to invoke contempt for others, to believe it acceptable to cast the first stone ― from the safe distance of a social media account? Would not a Christian follow Jesus’s example and offer hospitality to those who others treat with disgust ― share a meal, feel their humanity, offer companionship, without any strings attached?

Why, in other words, are many Christians ignoring Jesus? Perhaps interpreters and theologians, like the Apostle Paul, were more eloquent. Perhaps preachers have come to enjoy a measure of success by playing to the underlying prejudices of their audience. Perhaps human beings find it too hard to embrace Jesus’s message of radical love and forgiveness. As Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor explains ― somewhat apologetically ― in The Brothers Karamazov, if Jesus was to walk the earth today, he would have to be destroyed all over again. The world ― including his church – finds Jesus just too difficult to cope with.

Or, perhaps the truth is something darker. Has a deep and ingrained sense of disgust ― about sex in general, and homosexuality in particular ― bound some Christians in chains even stronger than sin?

While I understand that there is no monolithic “Christian” point of view about homosexuality, I am genuinely confused by the notion that any Christian can see matters as Israel Folau does. This is not to doubt the sincerity of Folau and his Christian supporters. But sincerity does not excuse fundamental error.

Surely modern Christians can grasp that a person’s sexual orientation is not something simply chosen. We are born “hard wired” with our preferences. To say that a homosexual person is destined for hell is to claim that each such person is born an abomination in the sight of God. That is an obscene suggestion ― not only in the eyes of a secular society, but, if the Gospels are to be believed, in the eyes of the founder of Christianity itself. Not once does Jesus indicate contempt for any person.

So, again I ask, how is it that a church founded on the commitment to unconditional love has become home to the demons of righteous indignation? In whose name has that been done? Don’t tell me it is Jesus. If unconditional love, free from any condemnation, is offered to the man who nails you to a cross, then how can it be withheld from someone whose only sin is to have not been born a heterosexual?

In the same spirit, perhaps it’s time to call a truce in the proxy war over free speech and religious freedom. It’s time for his detractors to practice what Jesus preached and reach out to Israel Folau; to extend to him friendship and understanding; to share a meal with him and offer him unconditional forgiveness ― for he knows not what he does.

This article was originally published by ABC , republished with permission.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

You are more than your job

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Allan Waddell 27 JUN 2019

The great promise of artificial intelligence is efficiency. The finely tuned mechanics of AI will free up societies to explore new, softer skills while industries thrive on automation.

However, if we’ve learned anything from the great promise of the Internet – which was supposed to bring equality by leveling the playing field – it’s clear new technologies can be rife with complications unwittingly introduced by the humans who created them.

The rise of artificial intelligence is exciting, but the drive toward efficiency must not happen without a corresponding push for strong ethics to guide the process. Otherwise, the advancements of AI will be undercut by human fallibility and biases. This is as true for AI’s application in the pursuit of social justice as it is in basic business practices like customer service.

Empathy

The ethical questions surrounding AI have long been the subject of science fiction, but today they are quickly becoming real-world concerns. Human intelligence has a direct relationship to human empathy. If this sensitivity doesn’t translate into artificial intelligence the consequences could be dire. We must examine how humans learn in order to build an ethical education process for AI.

AI is not merely programmed – it is trained like a human. If AI doesn’t learn the right lessons, ethical problems will inevitably arise. We’ve already seen examples, such as the tendency of facial recognition software to misidentify people of colour as criminals.

Biased AI

In the United States, a piece of software called Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (Compas) was used to assess the risk of defendants reoffending and had an impact on their sentencing. Compas was found to be twice as likely to misclassify non-white defendants as higher risk offenders, while white defendants were misclassified as lower risk much more often than non-white defendants. This is a training issue. If AI is predominantly trained in Caucasian faces, it will disadvantage minorities.

This example might seem far removed from us here in Australia but consider the consequences if it were in place here. What if a similar technology was being used at airports for customs checks, or part of a pre-screening process used by recruiters and employment agencies?

“Human intelligence has a direct relationship to human empathy.”

If racism and other forms of discrimination are unintentionally programmed into AI, not only will it mirror many of the failings of analog society, but it could magnify them.

While heightened instances of injustice are obviously unacceptable outcomes for AI, there are additional possibilities that don’t serve our best interests and should be avoided. The foremost example of this is in customer service.

AI vs human customer service

Every business wants the most efficient and productive processes possible but sometimes better is actually worse. Eventually, an AI solution will do a better job at making appointments, answering questions, and handling phone calls. When that time comes, AI might not always be the right solution.

Particularly with more complex matters, humans want to talk to other humans. Not only do they want their problem resolved, but they want to feel like they’ve been heard. They want empathy. This is something AI cannot do.

AI is inevitable. In fact, you’re probably already using it without being aware of it. There is no doubt that the proper application of AI will make us more efficient as a society, but the temptation to rely blindly on AI is unadvisable.

We must be aware of our biases when creating new technologies and do everything in our power to ensure they aren’t baked into algorithms. As more functions are handed over to AI, we must also remember that sometimes there’s no substitute for human-to-human interaction.

After all, we’re only human.

Allan Waddell is founder and Co-CEO of Kablamo, an Australian cloud based tech software company.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Ukraine hacktivism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Can robots solve our aged care crisis?

BY Allan Waddell

Allan Waddell is founder and Co-CEO of Kablamo, an Australian cloud based tech software company.

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 27 JUN 2019

I spent this weekend hearing from all corners what a wonderful Dad I am. It was quite lovely, and I’d very much like for it to happen more often.

This weekend I was effectively a sole parent as my wife was rendered bedridden by illness. For two days, I was in charge of a seven-week-old baby and almost three-year-old toddler.

Miracle of miracles – they didn’t die. In fact, I managed to feed and bath them, plus made sure they slept. I even packed them both up in the car and took them to a birthday party and back again.

An uneven playing field?

This is the Herculean labour that earned me torrents of praise. In fact, it didn’t just earn me praise – people messaged my bed-ridden wife not only with well-wishes, but to tell her how lucky she was. Oh, to have a co-parent like him!

I can’t imagine how frustrating these messages are for her to receive. I spend four days a week at work, which means she has the kids solo for those four days. In that time, she takes them to doctors appointments, libraries, playgrounds, feeds them, does an enormous amount of housework and manages, somehow, to keep herself alive.

What I did this weekend amounts to about 50% of what she does week in, week out. Guess how many people have texted me to say how lucky I am?

Less effort but more praise?

The double-standards here are staggering. They’re also incredibly unfair. To see someone receive more praise for less effort is profoundly invalidating – something about which women have been increasingly outspoken. It also makes social progress difficult – the more we see men’s modest contributions as incredibly generous and praiseworthy, the harder it is for women to ask more (even though what they’re asking for is entirely reasonable – lest we forget the last census, which reports that one in four men do zero housework).

What’s been less widely addressed is just how bad this double-standard is for men. I, and I would imagine most dads, want to be a great parent and partner. But that’s not helped by receiving praise for every little thing I do – it gives a false impression of exactly where I am on the spectrum: am I doing a great job, a terrible one, or just a mediocre one? It’s hard to tell through all the well-intended, generous praise.

Praise can be a double-edged sword

Praise is a powerful tool for behavioural change and moral growth. It can be used to help encourage people to do the right thing, remind them when they’ve slipped up and point out whose behaviour is a good example to follow. But that only works if the people offering praise have a clear idea of what’s actually worth praising – the praise in itself means nothing if it’s not properly calibrated.

And this is why the kind of praise I received is a problem. Taking care of your children is not exceptional, parenting-wise. It’s just what you’re supposed to do. Ditto, doing the laundry, cooking for the family, organising tradesmen to come and fix the house, planning birthday parties and all the other domestic activities that women do thanklessly and men do heroically. Or, at least, some men – again, one in four do no chores.

The sheer mass of men not pulling their weight makes it so easy for mediocrity to look amazing. The comedian Hannah Gadsby talks about how there is a line in the sand between ‘good men’ and ‘bad men’, but how it tends to be men who determine where that line is drawn. Similarly, as a dad I can always find a dad who isn’t doing quite as much as me and use that to determine how much I’m contributing. And, good news, I’m likely to have my self-image reinforced by praise and gratitude at every turn.

What’s more, there’s a social message embedded in that praise. Just as the text message said, women are told they should be grateful to have a partner who is not one of those who does no housework. Maybe he doesn’t do much – but it’s not nothing, so lucky you. Obviously, these narratives are very bad for equality.

They’re also, as I said, very bad for men who want to be great partners, parents and people. The school of ethical thought that most focusses on the kinds of questions I’m asking here is known as ‘virtue ethics’. Virtue ethics focusses on the kinds of character traits that are most likely to make people good and the kinds of activities that are likely to develop and model those characteristics.

Thinking in this way, we might be inclined to say that being a good parent requires the development of a bunch of different character traits – like compassion – and then practising those character traits by, say, holding a child gently while they have an emotional meltdown.

However, one the key ways we learn the virtues is by emulating role models. That means who we single out as role models is really important and – as we’ve said – what counts as ‘exemplary’ parenting can, for dads, be a pretty low bar. Not only does this leave a lot of cleaning up for the co-parents of men who have been sold this story, it undermines their ability to become who they really want to be: great dads.

What do we do about this? Well, for one thing, we should stop giving blokes a cookie just because they showed up. Reserve our praise for when it’s really deserved – and then hand it out equally. Great parenting is great parenting – just because it’s more common to see women in that role doesn’t mean they’re unworthy of praise.

Second, I think men have got to be critical about the kinds of feedback they receive. Before letting it stoke our egos, we need to consider whether or not it’s warranted. In an age of allyship and leaning in, social brownie points are pretty easy to come by for men. But we need to hold ourselves to a higher standard. As the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah writes, “a person of honour cares first of all not about being respected but about being worthy of respect.”

Matt Beard is a tired, okay dad.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

“I’m sorry *if* I offended you”: How to apologise better in an emotionally avoidant world

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Israel Folau: appeals to conscience cut both ways

Israel Folau: appeals to conscience cut both ways

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 26 JUN 2019

Israel Folau’s now infamous post in which he called on a range of “sinners” to repent, turn to Jesus Christ and thus be saved from an eternity in Hell has had more consequences than I suspect he anticipated.

It has led to his loss of employment. It has elevated his status to that of a champion for conservative Christian beliefs.

Finally, it has prompted widespread debate about the intersection between religious belief and the world of work.

It is this last issue that deserves further discussion.

Religious freedom comes in four basic forms: freedom of belief, freedom of worship, freedom to act in good conscience (which includes freedom from coercion in matters of religion) and finally freedom to proselytise (which includes the right to educate one’s children in the faith). Folau’s case involves the third and fourth of these freedoms.

What Folau believes and how he worships have not been challenged. Rather, he has been sanctioned for what he has done and said — not as a believer, but in his role as an elite rugby player representing Australia. However, can the two roles of “believer” and “contracted player” be so easily separated? That is the question at the heart of this issue.

What are Folau’s rights?

As a committed Christian, Folau obviously feels compelled to act on his beliefs — in this case by posting tweets and instagram posts directed at those who risk damnation. Within his world view, he is simply following the scriptural injunction to: “Go into all the world and proclaim the gospel to the whole creation. Whoever believes and is baptised will be saved, but whoever does not believe will be condemned.” (Mark16:15)

So, we might ask if it is right and proper that a person of such sincere religious beliefs has lost his job and been denied at least one platform for fundraising to defend his interests before the courts.

As a general rule, there is only one group of employers — faith groups — who claim a right to dismiss people from employment because of their religious beliefs. For example, a number of religious organisations have argued that their schools should be allowed to deny employment to otherwise competent people who do not practise their religion. It follows from this that employees who renounce the faith of the school would be open to dismissal.

No other employer may discriminate against a person based on their religious beliefs. So, given that rugby is not a religion (despite what some claim), how did Folau come to lose his lucrative employment — a risk that is now faced by his wife, Maria Folau, one of Australasia’s preeminent netball athletes and a Christian who supports her husband’s views?

Brands have a right to protect their interests

In order to broaden the debate, let’s consider the case of a Christian who believes that the Pope is the Antichrist and that Roman Catholics are all destined for Hell. Such views are not “hypothetical”. They were openly held by the Northern Ireland religious and political leader, the Reverend Ian Paisley.

In 1958, he condemned Princess Margaret and the Queen Mother for “committing spiritual fornication and adultery with the Antichrist” after they met with Pope John XXIII. Thirty years later, Paisley denounced Pope John Paul II as the Antichrist — to his face — while the latter addressed the European Union Parliament.

Now suppose an employee is of a mind similar to Paisley — so publishes a tweet attacking the head of the Catholic Church and all of its adherents in equivalent terms. Suppose the employee does so on the basis of what he considers to be a well-founded and sincere religious belief. However, in this case, it’s not just a vulnerable minority group who’s affected — but more than a billion Roman Catholics and their immensely wealthy and powerful church.

Let’s suppose that the “Paisleyite” employee is a prominent brand ambassador working for a major bank. After the tweet, all hell breaks loose. Upset employees threaten to resign, customers threaten to close their accounts, investors begin to dump the stock, etc.

Would an employer be justified in calling such a person to account? Or should the bank respect the expression of sincere, religious belief and defend the right of the brand ambassador to express such views — no matter what damage is done?

It seems reasonable that employers be free to take steps to protect themselves from the kind of strategic risk caused by well-intentioned, loose cannons like the hypothetical brand ambassador sketched above.

This should allow employers to put in place measures designed to protect their interests — and then ask their employees to act accordingly.

Employees have a right to choose too

There is an important point to be noted here. The employer has a right to define how its interests are to be protected. However, it falls to the employee to accept (or not) the relevant conditions of employment.

Any person who truly feels unable to accept those conditions should either not accept an offer of employment or if already part of the organisation, then they should consider resigning in order to find a place of employment better aligned with their moral compass.

This brings us back to the ethical core of the problem raised by the Folau case. Is it ever right for an employer to demand that an employee leave their conscience at the door? I think that the answer is no.

However, if the conscience of an employee should be respected, then so should that of the employer. No individual or organisation is required to be complicit in conduct that it sincerely believes to be wrong.

This is the ground on which Rugby Australia and GoFundMe have both stood. They have decided not to enable the propagation of views that they hold to be ethically objectionable. Rugby Australia’s employment of Folau as one of Australia’s elite sportsmen afforded him (and his views about sin) a prominence that others do not enjoy. They have denied him access to the platform they had provided to him.

Folau was never just a player. He has always been, in part, a brand ambassador. GoFundMe denied Folau its platform after he allegedly violated its terms of service.

Folau chose religion

What both sides of this debate need to consider are the requirements for even-handedness and proportionality. Those who act in the name of conscience — employees and employers — need to be sincere. They need to protect their position with the minimal restrictions necessary. They need to be even-handed — treating like issues and persons in a like manner. And they need to accept the reasonable consequences of their actions.

Folau must have known that labelling homosexuals (among others) as sinners destined for Hell would be incendiary — and risk damaging Rugby Australia.

After all, this was not the first time he had been vocal in his views. In the end, his choice was between what he understood to be his duty to his employer and what he understood to be his duty to his God. Folau chose to put his religion first.

Conscience is not a convenient friend. It often comes with consequences; some good, some ill.

Neither Rugby Australia nor GoFundMe has silenced Folau. He is still acting and speaking in accordance with his religious beliefs. He is still able to raise funds for his defence — as demonstrated by the swift offer of support provided by the Australian Christian Lobby. Folau still has a public platform — which he continues to utilise, as is his right.

Kicked out of the temple, Israel Folau remains free to preach in the public square.

Dr Simon Longstaff originally wrote this piece for ABC News. Photo credit: David Molloy

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe to our pets

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

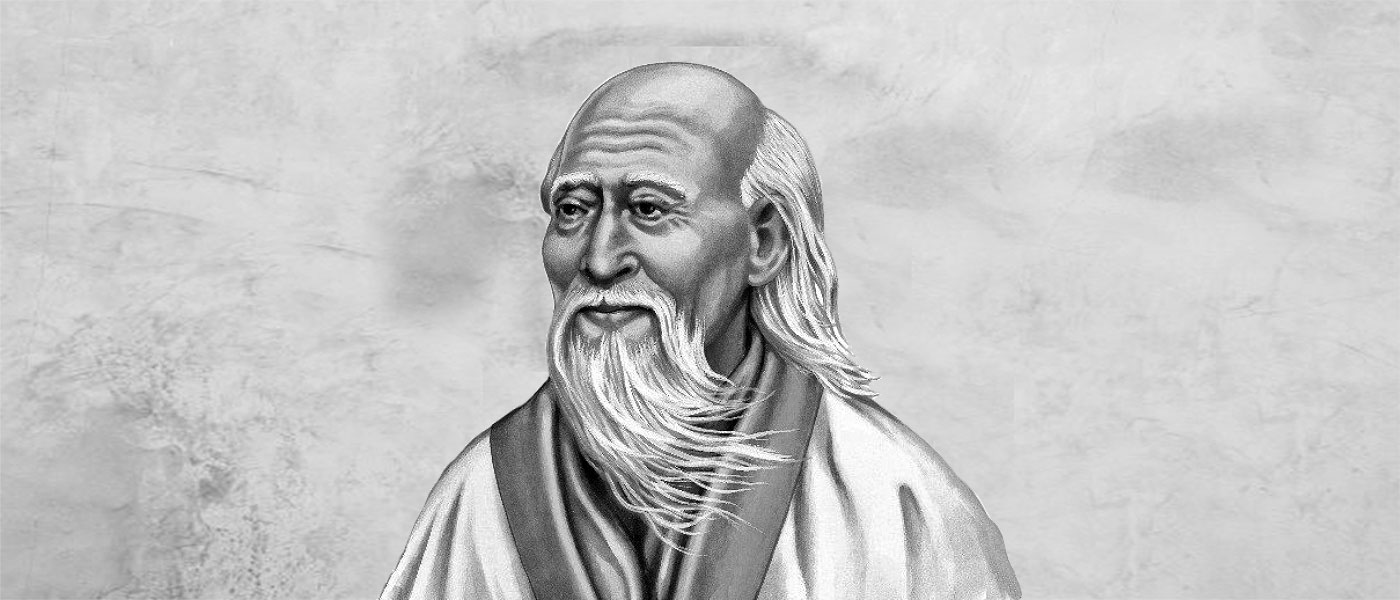

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

Daoism is one of the three pillars of Chinese philosophy, and its founders Laozi and Zhuangzi implore us to unshackle ourselves from the constraints of the way we think and live a spontaneous, authentic life.

When many of us think of “philosophy”, we conjure images of toga-wearing Greeks debating in the agora in Athens. Or Renaissance thinkers like René Descartes contemplating consciousness in his armchair. Or perhaps Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre smoking Gauloises in the cafés of post-war Paris.

But there is another tradition of philosophy that comes out of China that is just as deep and diverse, with just as long a history. It has considered many of the same questions as Western philosophy, such as the nature of reality, the possibility of knowledge and how to live a good life, but has sought to answer these questions in very different ways to many Western thinkers.

There are generally considered to be three pillars to Chinese philosophy: Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism. All three have mixed and intermingled over centuries to deeply influence Chinese culture and thinking to this day.

Daoist spontaneity and playfulness

In many ways, Daoism was a reaction against Confucianist thinking, which has strict rules on how we are supposed to live our lives, on the social roles and responsibilities we are supposed to take on, and has a strong emphasis on order and ritual. Daoism was a total rejection of these things, and is much more about living spontaneously, intuitively and experiencing a direct connection with nature and existence.

Daoism has two great masters, Laozi, who wrote the Daodejing, and Zhuangzi, who wrote the eponymous Zhuangzi. Both of these thinkers are believed to have lived between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, but while there are many stories about their lives, it’s difficult to separate fact from legend.

Both the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi are very playful texts, quite unlike most Western philosophy. Instead of outlining abstract theories supported by dry logical arguments, both were written in the form of sayings or stories that are often irreverent or absurd. They encourage the reader to reflect on life in a creative rather than analytic way.

For example, there’s a passage where Zhuangzi wakes up after dreaming he was a butterfly. But then he can’t be certain that he’s not right now a butterfly dreaming he’s a man. A similar sentiment was expressed by René Descartes, although far less poetically.

The three daos

The term “dao” itself is often translated to mean “way” or “path,” but it’s not an easy concept to pin down, which is by design. In a sense, the dao is like the natural order of the world, and following the dao is to be living in accordance with nature.

There are typically considered to be three daos:

- The human dao: the world of words, judgements and society

- The natural dao: the natural processes and regularities of the world, like the laws of nature

- The grand dao: the sum total of all things in the universe

These have a complex relationship, and Laozi wanted to make sure we don’t make the mistake of thinking the human dao is the only dao there is. For while we automatically use words and concepts to carve the world up into discrete things, nature itself is continuous. And while we can be judgemental, nature itself is free from judgement.

A central tenet of Daoism is embracing these opposite and contradictory states simultaneously. We can see some if this reflected in the yin/yang symbol, taijitu. It is at once a unitary thing, but it’s also composed of two opposites: the yin and the yang. This can be interpreted as representing the divisions that emerge within human thought – the separation of the one natural world into light/dark, hard/soft, active/passive, good/bad – but also shows how these things are complementary and all part of a greater whole.

There are even some Western thinkers who have wholeheartedly embraced this notion of complementarity. Notably, the Danish quantum physicist Niels Bohr argued that the seemingly contradictory quantum and classical accounts of reality weren’t in opposition but were complementary. He even chose the taijitu symbol for his coat of arms when he was knighted by the King of Denmark.

Many of the lines in the Daodejing and Zhuangzi challenge us to unshackle ourselves from the human dao and to contemplate the natural and the grand dao, and to realise that they’re all really one and the same.

For example, one translation of the opening line of the Daodejing is “the dao that can be spoken is not the true dao.” (In Chinese, it’s even more obtuse, being: “the dao that you can dao is not the true dao”.) If that’s so, then why speak or write this at all? And yet this realisation could only have come from writing this in the first place. Thus does a core paradox of daoism enter our minds to do its noble work.

Just be

Daoism teaches us to practice emptiness and non-action, which sits in stark contrast to many philosophical traditions that teach us to fill our minds with knowledge and to act with intent. Daoism tells us that things in the world just are, we are also in the world and just are, but we have this irritating habit of forgetting to just be and instead think and reflect on what we are, and then are guided by what we think we are instead of just being what we really are. It’s that simple.

“Therefore the sage dwells in the midst of non-action and practices the wordless teaching” – Laozi

Laozi and Zhuangzi are often cheeky, irreverent, playful and inscrutable. In a way, they are urging us to encounter nature directly, not mediated by words, and definitely not by rituals and rigid social roles.

This is not an easy thing to do, which is why the text encourages – or nags – us to snap us out of our complacent reliance on abstract concepts rather than experience concrete reality.

Dr Tim Dean is a philosopher, writer, honorary associate with the University of Sydney, editor of the Universal Commons, and faculty with The School of Life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Metaphysical myth busting: The cowardice of ‘post-truth’

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

We need to talk about ageism

There’s growing evidence of change afoot in attitudes toward age, ageing and older people and it’s about time.

After decades of pondering – and usually catastrophising – about the impact on society of the dreaded ‘ageing population’, we may just be reaching a tipping point.

This term, tipping point, is described by Malcolm Gladwell in his bestselling book of that title as the “magic moment when an idea, trend, or social behaviour crosses a threshold, tips, and spreads like wildfire”.

US ageism activist, Ashton Applewhite, suggests we might be there. She is the author of This Chair Rocks – A Manifesto Against Ageism and will be visiting Australia in November this year.

“The Guardian has just appointed a Longevity Reporter, for example,” she said, “who interviewed me at length and kept asking whether the culture was at a turning point”.

Applewhite argues most people are looking to cash in on the ‘longevity economy’ by selling products and services to a generation that controls most of the disposable income in the developed world.

“But there are also a zillion conversations going on about intergenerational initiatives, older women coming into our power, teaching medical students about age bias, incorporating age into diversity and inclusion training, fetishising of the old-and-fashionable, and many more domains.”

This is happening because people everywhere are waking up to the fact that no domain – from healthcare, to entertainment, to business, technology, the built environment – will be unaltered by the permanent, global and unprecedented phenomenon of population ageing. It carries fascinating social, economic, and ethical implications.

The big lag

One of the biggest challenges of population ageing stems from the fact that the roles and institutions around us – with all their underpinning assumptions, attitudes and behaviours – were created when lives were shorter and very different. And they haven’t had time to properly catch up.

A coalition of diverse Australian organisations and individuals have committed to address this lag with EveryAGE Counts, a long term advocacy campaign to change these destructive, outdated, yet deeply engrained attitudes and assumptions about ageing and older people. The coalition includes the Australian Human Rights Commission, COTA Australia, National Seniors, the Federation of Ethnic Communities Councils, and the Regional Australia Institute.

“Research shows that many of society’s views about older people – the views and assumptions that drive all the negativity around ageing – are based on outdated myths and stereotypes that simply do not apply in this era of prolonged good health and increased longevity,” says EveryAGE Counts campaign co-chair, Robert Tickner.

“People are being prevented from living the productive, healthy, engaged lives they want to live as they get older because our society tends to devalue and marginalise older people,” he says.

“And these negative stereotypes are so pervasive and deeply ingrained – in our language, in representations in the media and in popular culture – that many of us have bought into them without question. So we actually contribute to our own marginalisation as we grow older. It’s why ageism is often described as prejudice and discrimination against your future self!”

The EveryAGE Counts campaign aims to end ageism. It is working to make it as unacceptable as other forms of prejudice and discrimination in our community.

“Terms like sexism, racism and homophobia are well understood and have become embedded in our societal norms. Ageism is not. Racist, sexist and homophobic behaviours are easy to spot, ageist behaviours, less so,” said Tickner.

Ageism is a bit different to other ‘isms’. Racist or sexist attitudes and behaviours, for example, are usually based on prejudices and assumptions about a person or a group that is ‘different’ to us – a different race, a different gender.

“The great irony is that ageism can affect us all, regardless of race, gender, religion, size, shape or our favourite music! It is discrimination against yourself, albeit your future self, for each and every one of us… should we be fortunate to live beyond our youth,” Tickner said.

There have been some great efforts in the last couple of decades, in Australia and internationally, to raise consciousness levels about ageism and its many negative impacts. Applewhite is trying to do this by urging us to swap ‘women’ for ‘older people’ when thinking about some of our attitudes and assumptions. Would you use a sweeping generalisation for an entire gender? Do you think ‘older people’ who may span 30 to 50 years in age, are all the same?

Many are comfortable calling out racism, sexism or homophobia. Yet jokes about older people are less likely to attract reprimand. I encourage you to check out the EveryAGE Counts campaign, take the ‘Am I Ageist?’ quiz and sign our campaign pledge:

I/we stand for a world without ageism where all people of all ages are valued and respected and their contributions are acknowledged. I/we commit to speak out and take action to ensure older people can participate on equal terms with others in all aspects of life.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Fiona Smith 31 MAY 2019

In the wake of the Financial Services Royal Commission, many employers are asking whether they should award bonuses to people who choose to do the right thing.

Boards and CEOs are discussing whether people need an incentive to make ethical decisions and how “ethical incentives” could avoid the risk of encouraging unintended behaviours.

Incentives have a tarnished reputation, with poorly-constructed programs blamed for driving a culture of greed in banks and insurance companies. The international anti-corruption organisation, Transparency International, says performance incentives should not just focus on getting sales, for instance, but also consider how those sales are achieved.

“ … incentive schemes should move beyond mere alignment with values and ethical codes and actively encourage ethical behaviour,” according to the authors of Transparency International’s 2015 report Incentivising Ethics: Managing incentives to encourage good and deter bad behaviour.

“This means that they should not be based solely on financial targets, but should contain non-financial targets that reflect and drive ethical behaviour. Ultimately, this mix of incentives should support the long-term sustainability and success of the company.”

Senior principal advisory at research company Gartner, Arj Bagga, says the Royal Commission has sparked many conversations with his clients, who want to know if they can use ethical behaviour as a measure in the “performance systems” they use to encourage the best work from their people.

A limit on rewards?

Bagga says they can – but within limits. Financial rewards or goods (such as restaurant vouchers) are only effective up to the value of $300, he says.

“Anything over $300 has an incrementally lower benefit on employee performance.”

The reason for this is that financial rewards are an “extrinsic” motivator, meaning that it comes from outside the person, and are much less effective than an “intrinsic” motivator (an inner desire).

“After $300, it starts to extrinsically motivate them too much, whereby they just associate ethical behaviour with financial reward, which is not what you want,” says Bagga.

“You actually want them to be intrinsically-motivated, because, if you remove the reward down the line, because of cost cutting or whatever it might be, employees will then stop acting ethically, just because they’re not being rewarded.

“What we want to do is have a balance between the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.”

Recognition vs cold hard cash

The most intrinsic powerful motivator is recognition – commending people for their ethical behaviour. Such public recognition can increase employee performance by up to 3 per cent, he says.

However, the effect of that recognition can be supercharged by attaching a financial reward “which we found can increase performance by a further 5 per cent”.

While research has shown that the effectiveness of financial rewards can quickly fade, Bagga says the impact of the small reward can be sustained by using ethical behaviour as a measure in performance reviews.

Because their promotions depend on it, people will continue to try to display the desired behaviours, he says.

Making the right choice

A further question is how to identify ethical behaviour, when it is essentially just doing what would be expected of a decent person. Bagga says managers can reward those instances where people make ethical choices in situations where there is no clear answer.

This could be when, for instance, a salesperson sells a product that earns a lower commission, or no commission, but is a better choice for the customer.

Transparency International, while supporting the use of incentives, points out some of the risks around trying to identify and reward ethical behaviour: the measures are subjective, corrupt employees may be convincing actors, not all ethical acts will be recognised which could cause resentment, and discussion about behaviours may lead to some difficult performance review discussions.

Bagga says ethical behaviour is a good business strategy. If organisations can ensure their people recognise what ethical behaviour is, adopt an ethical mindset and then act upon it, they can increase employee performance by up to 12 percent, he says.

Short term pain, long term gain

Some employers may not be sympathetic to the idea their people forego revenue as they look for the best option for customers. However, Bagga says that view would be myopic.

“It may impact you in the very short term but, longer term, it will actually increase your brand awareness in the marketplace and it will increase your ability to attract talent,” he says.

“In Australia, specifically, ethical behaviour is one of the core reasons a person chooses to join an organisation.”

Australian survey respondents rank “ethics” and “respect for the organisation” higher than manager quality and future career opportunity when they are assessing career paths.

Bagga says that it is not just the financial services companies that are interested in the idea of “incentivising” ethical behaviour.

“I’ve also had conversations with mining companies and telecommunications companies, who are trying to get on the front foot of this and make sure they are bullet proofing themselves against any unethical behaviour that could occur in their organisations because they understand, through the Royal Commission, what the implications of those could be on the performance of their business and the perception of their brand.”

Cashless recognition

- Introducing ethics and values measures into performance reviews

- Good ethical conduct being a prerequisite for promotion.

- Spot awards for good ethical practice, recognising special contributions as they occur, usually over a relatively short-term period.

- Awards for people who speak up or challenge questionable conduct.

- Recognition and/or prizes for people who excel in ethics and compliance training.

- Recognition for outstanding contribution to the ethics and compliance programme.

- A company-wide ethics award scheme.

- Coverage of examples of good ethical or anti-corruption practice in the company newsletter.

- Thank you letters from the CEO or senior managers for people who display ethical behaviour.

- Dinner with the CEO as a prize for people who demonstrate ethical behaviour.

Source: Transparency International

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. The Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

Reports

Business + Leadership

Thought Leadership: Ethics at Work, a 2018 Survey of Employees

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Tyson Yunkaporta

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY The Ethics Alliance 31 MAY 2019

“How am I doing?” is a question that has helped graphic design platform, Canva, to become one of Australia’s most talked-about startups.

In May, the six-year-old company announced it had raised $70 million from US venture capital firm General Catalyst (valuing Canva at $3.6 billion) and acquired two stock photography firms.

Its workplace culture has also received acclaim – with top employer awards from Great Place To Work and LinkedIn last year – and its workforce has at least doubled every year.

In answer to the question above, it seems like Canva is doing very well, thank you.

The practise of asking for feedback is a core part of Canva’s culture and performance strategies. We need to know how we are going so we can improve, however most of us hate the assessment.

New York University research at a major consultancy looked at our aversion to criticism and discovered that people are equally anxious, whether they are giving the feedback or receiving it.

One of the co-authors of the study, psychologist and NeuroLeadership Institute senior scientist, Tessa West, says the best way to develop a “feedback culture” is to train people to ask for it – rather than wait for it to be delivered.

By requesting the assessment of their performance, individuals feel a sense of control and certainty and can steer the discussion where they want. The people giving the feedback will also feel more relaxed, because they no longer have to guess what is wanted from them.

The head of people at Canva, Zach Kitschke, says new hires are introduced to the feedback culture through an “onboarding boot camp”, featuring sessions from the three founders of the company – Melanie Perkins, Cliff Obrecht and Cameron Adams.

“Having a feedback conversation can be challenging and quite tricky, but we have a workshop that everyone goes through to learn how to do feedback and act in a constructive, supportive way,” Kitschke says.

“We have the philosophy that if everyone is constantly asking what they did well, or how they went in the meeting or what could they do better or how could they grow, then people are more open and more ready to hear feedback and people are more likely to give it as well.”

Kitschke has been with Canva for six years, from when it was a small startup with seven people to its present workforce of 600 in three offices in Sydney, Manila and Beijing.

Executive coach, Sarah Nanclares, joined the company as an internal coach last year and writes in a Canva blog: “… asking for feedback is a bit like exercising a muscle: the more you use it, the easier it becomes, and before you know it seeking regular feedback is no longer a scary task. In fact, it becomes welcomed.”

Points of difference

1.Skin in the game: Every employee is given equity options and becomes an owner of the business. Employees get a bonus of $5,000 if they successfully introduce a new hire to the business.

2. The Fix-It form: This form can be used to notify the founders and other senior executives of any problems.

3. Right fit: Recruits are screened for the values: Be a force for good, be a good human, set crazy big goals and make them happen, empower others, pursue excellence, and make complex things simple.

4. Someone to watch over me: Every new person gets paired with a mentor from the same area or discipline. Anyone can receive training to be a mentor.

5. Businesses within the business: Within Canva are 15 groups that function as their own startups, running independently, with the ability to move quickly.

6. Breaking bread: The teams stop for lunch every day and sit together at long tables so that no-one has to eat alone. A chef prepares shared serving plates and anything not eaten at lunch is refrigerated for people to take home for dinner. Ingredients come from a Canva-owned farm and the bar is open all day.

7. Open door: Employees are welcome to bring their dogs and children to work.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. The Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

David Gonski on corporate responsibility

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

From capitalism to communism, explained

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Want men to stop hitting women? Stop talking about “real men”

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Alison Hill 28 MAY 2019

We’ve all fucked up before. Big mistakes and small, regrettable misdemeanours.

I have a penchant for saying things that are funny inside my head but come out all wrong. I know I’ve unintentionally offended and hurt people by blurting out the first thing that comes to mind. If I’ve become aware of it, I’ve tried to make amends. But it’s never been big, public or career ending. So, being honest, part of my interest in going along to ‘The Ethics of Fucking Up’ was schadenfreude.

I wanted to hear how Sam Dastyari and Mel Greig, who shared their stories of the ‘Chinese political donor scandal’ and the ‘Royal prank call’ had stuffed up. In truth, I wanted to revel in it just a little, to tell myself that at least it had never been that bad for me. I wanted to identify with Paul McDermott, whose fuck ups had never made the front pages or ruined lives.

I watched the crowd enter the sold-out venue in inner Sydney, thinking that every single one of these people who looked so smart, privileged and self-possessed had done at least one monumentally stupid thing in their lives. Had they come looking for redemption? For confirmation that what they did was okay? Because we all fuck up, whether we’re being naïve and thoughtless or doing something dastardly.

Pizza, wine and dark confessions

So what did I take away from a night that was variously funny, intelligent, shocking and sad, with pizza and wine thrown in for good measure?

It seems the biggest fuck ups come about when there is a combination two things: individuals being encouraged to act without first thinking through their decisions, and institutions not living by an ethical framework – or not having one at all. Add to that the speed at which we act in the tech era and it’s no wonder we’ve hurtled into our present state.

As Sam described it, ‘We’re heading backwards with our morality, with our acceptance and empathy for others, with our responsibility for the planet, while fear, selfishness and xenophobia are controlling our political decisions’.

So despite not being able to condone what he did in the ‘Chinese political donor scandal’, my heart ached for him when he described how, in the midst of the scandal, he lay in bed at 3am alone with his thoughts, realising he was solely responsible for the mess.

Rethinking forgiveness

Nobody deserves this unless they have committed some monstrous crime. I decided that I will accept mea culpas and requests for forgiveness more graciously, in my personal life and by public figures. When somebody shows true remorse, I’ll forgive them, because I’m more aware how we all fuck up from time to time, in big and small ways. It’s only human.

We love to hold individuals to account, especially when they are public figures. Perhaps we should be harder on institutions. Mel Greig told us how the broadcast organisation’s processes and ethical judgements went unquestioned during the ‘Royal prank call’.

To recap: the call to the London hospital caring for the Duchess of Cambridge ended in the suicide of nurse Jacintha Saldanha, who fell for the joke thinking it was the Queen and Prince Charles. A chain of decisions meant the prank call was broadcast in full – although Mel tried to stop this happening.

Yet Mel had to wear all the blame. Her description of the trolling she endured afterwards, which included death threats, made the room go quiet. Tears shone in the eyes of the person next to me. Public shaming, relentlessly negative and disparaging media coverage and the non-stop blast of social media are damaging people like never before. At no time has it been easier to broadcast judgment on individuals, instantly and loudly. But institutions are never made to suffer in the same way. Think banking royal commission.

How would I survive if this happened to me, I wondered?

A call to arms against the trolls

Would I be brave and resilient like Mel, and use the horrible experience to start a conversation to help other people, as she did by starting Troll Free Day? Would I have been strong enough to front up to the inquest into nurse Jacintha Saldanha’s death, look her children in the eye and say sorry? Would I stop looking for scapegoats and accept blame, as Sam did, learning to live with what he called ‘the darkest shit in the world’?

As always, a discussion about ethics goes on long after the lights have been turned off. Listening to this conversation about the ethics of fucking up has encouraged me to start conversations about it with friends and family. I realised we all draw the line about what we will and won’t forgive somewhere different, one of the things that defines our personal ethics.

The crowd drifted into the street to the sounds of Paul Kelly’s I’ve Done All the Dumb Things and Cher’s If I Could Turn Back Time. Neither has ever been on my playlist, but I heard them in a new way. Opening your ears to things you think you already know is good thing.

I’ll certainly go back for The Ethics Centre’s conversations on desire, lying, courage and nudity.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING