Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Amy Gray 22 AUG 2019

The continuing moral panic over women’s naked selfies is fundamentally misframed. By emphasising the potential for women to be made victims, we ignore the ways a woman’s body can be an expression of power.

According to the prevailing moral panic of the day, young women take naked selfies in order to please others and not themselves. This, we’re told, leaves them vulnerable to exploitation because women must always be vulnerable.

It’s as though the only mystery afforded to women is not their thoughts or talents but what lies underneath their clothes. Go no deeper than the skin. Deny any complexity that might present her as a human with needs separate from what men may want.

This seems to be a narrative we teach teenagers. My daughter was taught that not only was there no legal recourse for photos shared without consent (untrue) but that the effects on women were so catastrophic that they should never send a naked photo (also, untrue). This happened on International Women’s Day, as if to remind us of our to-do list.

Inevitably, they learn what we teach. When I worked with teens on a short film, they told me how boys pestered every girl in their class for naked selfies. The girls didn’t even think it was sexual; more of a competitive collection like Pokemon Go but for undeveloped breasts. The requests were thought of as frustrating but normal, because “that’s just how they are”. Yet despite the mundanity of such a frequent request, the same teens sincerely believed leaked selfies would hound a woman to her grave.

Naked selfies carry many gendered clashes. I’ve always gasped at the difference between gendered aesthetics: I’ll rush to clean my room, groom and put on makeup before getting into an appropriate outfit of sorts before painstakingly composing shots; men just send a close-up photo of their cock jutting from a thicket of pubes.

It’s an effective example of the differences between the male and female gaze. A woman prepares because she is conditioned to know what men find attractive and that she is expected to deliver that. Men, conditioned to expect immediate access regardless of merit, put almost zero thought into their selfies. In the rare case they do, they project an image of themselves they want to see, rather than women who mirror what men want to see.

This positioning reinforces the power dynamic in heterosexual sexting. Men expect entertainment and women entertain at threat of exposure (also expected).

But why does the power lie with men?

On image sharing site Imgur, men enthusiastically share photos of naked women, even creating themed days for certain ‘types’ of women. But the images presented reflect the male gaze – photos taken of women, not by women.

Generally, whenever women posted selfies on Imgur, sexualised or not, she was immediately inundated with caustic remarks to stop being an exhibitionist (a polite euphemism for attention whore). That these are the same men who think nothing of going into a woman’s DMs to ask for naked photos is just another layer to it all. There is a clear mode of production, where women are the object and men remain in control of when and how they are seen. This is where the phrase “tits or get the fuck out” shows its intent: give us the body parts, not the entire body.

Perhaps this is because it is easier to sexually appreciate an object that has not been humanised or seen as an individual. When things are anonymised or presented in such a volume that they lose all semblance of individuality, they become an object that can be appreciated or abused without shame.

The power balance still rests with men – naked women are objects men readily expect, and demand to be presented in anticipated service of them. In this position of power, men expect women to arouse them, yet rarely consider whether women are aroused. Amazingly, we rarely discuss whether women find joy or pleasure in taking naked selfies, whether for themselves or others because we can’t move past women’s seemingly inevitable victimhood.

I’ve taken naked selfies for well over a decade. I first worried if photos might leak but, somewhat ironically, this concern has disappeared as I do more work in public. In Doing It: Women Tell the Truth About Great Sex, an anthology about sex, I wrote of how selfies can become graphic storytelling that not only builds intimacy but also an understanding of my sexuality and my sexual aesthetic pleasure. It is a power I never want to give up, so the book also contains a naked photo of me I had taken for a lover. It is a deliberate attempt to interrupt the means of production and also claim space within my sexuality, one that is defined by myself, not others.

When the photo was republished (with consent) by SBS, I wrote that “this is not some wishy-washy Stockholm syndrome masquerading as empowerment – there is ferocity in my choice”. It remains true today. By claiming my agency as an individual who feels pleasure and expression, I realise that confidence is not only crucial for my personal survival under patriarchy framed solely for men, but it is also a political act I can define as I choose. It makes me aware that my body, choices and actions are decided by me without reference to others’ expectations and that I contain greater complexity the roles of servant or victim that society allows.

Around this time, Mia Freedman wrote an article entitled ‘The conversation we have to have: Stop taking nude selfies’. Promoting the article on Twitter, Freedman wrote “taking nude selfies is your absolute right. So is smoking. Both come with massive risks.” In response, I took another naked selfie, but this time with a cigarette draped from my mouth and ‘fuck off’ written on my chest in black lipstick. I posted it everywhere without care because – again – my body, choices and actions are decided by me. I made the choice that and every day is that I will not have victims presented as complicit in their abuse. Because the fault will always be with the abuser, not the abused.

An act of power

Despite their conflicting emotions, publishing naked selfies taken in either arousal or anger are fearsome in their power. They are as much a rejection of victimhood as they are an opportunity for retribution. People can try to weaponise my body against me, but I will do it first and use it against them because I know its power.

This is why patriarchal structures and men condition women into submissive disempowerment. Women’s bodies are defined narrowly as vessels for pleasures and service for others, not ourselves. Such narrow and compliant definitions intentionally belie the power and complexity we contain.

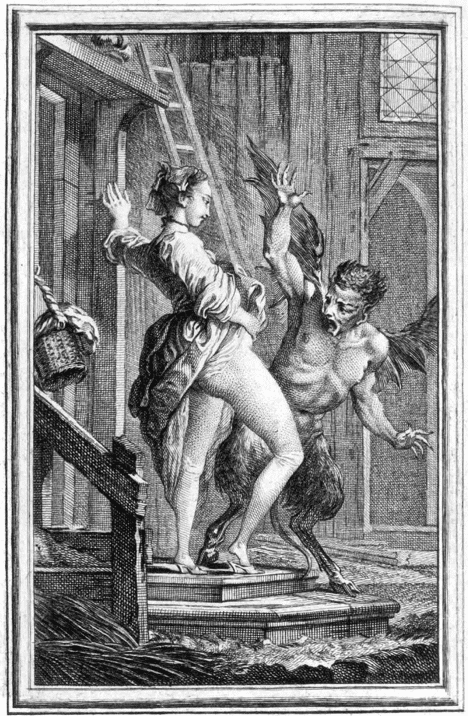

Stories abound throughout history of the malevolent power of women’s bodies, so profound was male unease surrounding bloods and births. Women were told their vaginas ruined ship rope or their menstruation damned success. This was an admission women’s bodies were terrifying in their otherness but was also an excuse to contain them to the home rather than out in the community where they might gain power or control.

But history tells us many women believed in the power of their bodies. Balkan women would stand out in the fields, flashing their vaginas to the sky to quell thunderstorms. The Finnish believed in the magic of harakointi, using their exposed bodies to bless or curse on whim. Sheela-na-gigs (carvings of women often found in European architecture) embraced their power by spreading their labia, not to please or welcome men, but scare off evil. Women would lift their skirts to make others laugh in feasts for Roman gods and goddesses or lure lovers. More recently, women have exposed their bodies to protest petroleum in Nigeria or civil war in Liberia in acts of political, angry anasyrma.

Reframing the dialogue

The continuing moral panic over women’s naked selfies is fundamentally misframed. Women are presented as passively-defensive vessels in a state of perpetual victimhood. We are tasked with hiding our shameful-yet-coveted nakedness from people who expect to see us but only under their strict conditions.

A truer representation is that power exerts in all manners of life, including how we sexually communicate as equal, consenting partners. The moral panic should focus on when power corrupts that balance and how to correct it, not how to maintain the same corruption.

Join us as on 18 September for an an intimate conversation with Sexologist, Nikki Goldstein and art curator Jackie Dunn to unwrap the ethical dimensions of being nude. Get your ticket to The Ethics of Nudity here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

You are more than your job

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Join our newsletter

BY Amy Gray

Amy Gray is a Melbourne-based writer interested in feminism, popular and digital culture and parenting. follow her on twitter @_AmyGray_

Save the date: FODI returns in 2020!

Save the date: FODI returns in 2020!

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 7 AUG 2019

Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI), Australia’s original provocative ideas festival, returns in 2020 for its 10th festival. April 3 to 5 will be a milestone weekend of provocation, contemplation, critical thinking and preparation for the battles of the next decade.

Presented by The Ethics Centre, FODI 2020 will once again feature leading thinkers from Australia and around the world to interrogate the issues of today and prepare for the major shifts of tomorrow.

FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey said: “Over the past decade the number of avenues for people to talk and share their opinions has steadily increased, we are more connected than ever with like-minded people, but the cost has been significant. We are losing the ability to listen.

“Without the tools to listen to other opinions and contemplate new ideas, society risks fracturing like never before.”

“Without the tools to listen to other opinions and contemplate new ideas, society risks fracturing like never before. The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has always been an opportunity for deep thinking, carving out precious space for disagreement, difference of opinion and critical thinking.

“As we brace for 2020, FODI will celebrate its 10th anniversary by looking again to the future and presenting a cohort of FODI alumni, representing the world’s best thinkers, journalists, creators and specialists, giving Sydneysiders an opportunity to listen to what will be shaping the world tomorrow.”

The Ethics Centre Executive Director, Dr Simon Longstaff said:

“The Ethics Centre is thrilled to once again be presenting the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. One of The Ethics Centre’s strategic priorities is to build and sustain the ‘ethical infrastructure’ that underpins a free, dynamic and democratic society.

“Fragile societies break apart when challenged. The resilient cohere around a common desire to face the truth – even if it is hard to bear.”

“Fragile societies break apart when challenged. The resilient cohere around a common desire to face the truth – even if it is hard to bear. FODI tests the truth of the claim that we are a ‘civil’ society – and proves that even in moments of profound disagreement – we have the strength to live an ‘examined life’.”

Last year’s sell-out festival featured Stephen Fry, Rukmini Callimachi, Niall Ferguson, Megan Phelps-Roper, Chuck Klosterman and Toby Walsh.

More information, including the full program and festival venue, will be announced in the coming months. Visit festivalofdangerousideas.com to subscribe to be the first to hear our news.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 6 AUG 2019

The Ethics Centre (TEC) has made a submission to the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) regarding its discussion paper, The Regulation of Lobbying, Access and Influence in NSW: A Chance To Have Your Say.

Released in April 2019 as part of Operation Eclipse, it’s public review into how lobbying activities in NSW should be regulated.

As a result of the submission TEC Executive Director, Dr Simon Longstaff has been invited to bear witness at the inquiry, which will also consider the need to rebuild public trust in government institutions and parliamentarians.

Our submission acknowledged the decline in trust in government as part of a broader crisis experienced across our institutional landscape – including the private sector, the media and the NGO sector. It is TEC’s view that the time has come to take deliberate and comprehensive action to restore the ethical infrastructure of society.

We support the principles being applied to the regulation of lobbying: transparency, integrity, fairness and freedom.

Key points within The Ethics Centres submission include:

-

- There is a difference between making representations to government on one’s own behalf and the practice of paying another person or party with informal government connections to advocate to government. TEC views the latter to be ‘lobbying’

-

- Lobbying has the potential to allow the government to be influenced more by wealthier parties, and interfere with the duty of officials and parliamentarians to act in the public interest

-

- No amount of compliance requirements can compensate for a poor decision making culture or an inability of officials, at any level, to make ethical decisions. While an awareness and understanding of an official’s obligations is necessary, it is not sufficient. There is a need to build their capacity to make ethical decisions and support an ethical decision making culture.

You can read the full submission here.

Update

Dr Simon Longstaff, Executive Director at The Ethics Centre, presented as a witness to the Commission on Monday 5 August. You can read the public transcript on the ICAC website here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY David Burfoot 6 MAY 2019

Corruption and probity are hot topics in Australia’s public sector. Even a cursory glance at recent cases brought before corruption watchdogs shows this.

The long running stories and court cases that follow have become a staple of national news bulletins. Any time a state asset is built, sold or disposed of, there are serious questions to be asked.

Probity – which is a corporate noun for ethics or honesty and decency – has established its place in the architecture of technical services that assess, assure and measure high-risk public sector projects. Probity advising and auditing is crucial when how a project is executed is just as important as any intended outcome.

As the line separating public and private sector accountabilities becomes less clear, non-government actors are increasingly looking to probity professionals to help ensure – and show – integrity in their dealings. However, before doing so it is important the probity professionals themselves improve the integrity of their process and gain a more sophisticated understanding of ethical frameworks.

Probity services are provided both by large accounting firms and a growing band of smaller boutique operators. Probity plans (documents that set out how the project will be run to ensure the integrity of the process) are now a mandatory requirement for many public projects.

Probity professionals use a number of lenses to monitor and promote ethical decision making in execution, typically through the following fundamentals:

Value for money: Was the market tested adequately to ensure an organisation was achieving the most competitive result, which made the best use of resources?

Conflicts of interest and impartiality: Were processes in place to manage any actual, perceived or potential conflicts of interests?

Accountability and transparency: Was an auditable trail maintained to provide evidence of the integrity of the process? Was enough information made available to promote confidence – for example, were selection criteria and time lines for decision making adequately communicated?

Confidentiality: When sensitive information from stakeholders is received, such as private or business-in-confidence information, was there a process in place to identify and protect this information?

The growth of probity services over the last 30 years undoubtedly reflects their ability to add value to projects. However, over that same period there has been concern that practitioners have at times diminished, rather than promoted, probity fundamentals. Some of the critical factors include:

- Relying too heavily on compliance monitoring at the expense of ethical considerations

- Allowing their duties to be too narrowly defined by clients

- Lacking the confidence to challenge impropriety

- Allowing themselves to be “shopped” (much like “legal advice shopping,” clients can go from one probity advisor to another until they get the advice they want).

There is also concern that public sector agencies can overuse these services, having the effect of “contracting out” their probity obligations in their regular operations.

To some extent these are symptoms of the unregulated nature of probity services. There are no formal qualifications required for probity advisors and auditors and no professional standard governing them.

Their difference from traditional audits or investigations has led to some misunderstanding of their role and judgements which can lead to unfair criticism of probity professionals, but also to exploitation by both clients and probity practitioners.

To tackle these problems and prepare for a broader role in guiding business dealings, probity practitioners need to acknowledge their own industry’s need for an ethical framework and an increasingly robust standard for professional practice.

This framework would acknowledge their implied obligation to society to be more than a mere compliance check, and, on behalf of the average Joe on the street, to be the one in the room to ask a simple pub test question: after all the boxes have been ticked, does it look and sound like an ethical process?

To do this, the profession needs to imagine its duty in broader terms than self-interest or the interest of clients, but to society in general, in line with other professions tasked with acting in the public interest.

For some time, probity professionals have used policy documents such as the NSW Code of Practice for Procurement to gauge the ethical performance of government projects. However, as their duty and work expands to different sectors and in line with changing community expectations, they will need to be able to identify the ethical frameworks peculiar to those sectors and to the organisations they are commissioned by.

Used effectively, an ethical framework is the foundation of an organisation’s culture.

When requested to provide probity related advice, The Ethics Centre includes the ethical framework amongst its list of fundamentals. This allows our clients to do more than tick boxes. It allows them to assess whether they have lived up to their ethical obligations, the values they proport to uphold and their promise to the community.

In a world in which trust is in deficit, these are important skills to have.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The 6 ways corporate values fail

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Who’s your daddy?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The rights of children

BY David Burfoot

David has worked in the not-for-profit, public and private sectors domestically and internationally for organisations as diverse as the United Nations Development Program, Deloitte, the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption and Sydney University. He has been an anti-corruption specialist with a number of government agencies and held senior positions responsible for corporate planning, change and internal communications.

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipClimate + EnvironmentSociety + Culture

BY David Burfoot 30 APR 2019

Papua New Guinea is known as one of the most corrupt countries in the world.

Yet through delivering ethical leadership training to public officials there, The Ethics Centre is seeing a natural aptitude for ethics that government and corporations are struggling to nurture in Australia.

It has one of the most diverse cultures with over 850 known languages spoken. It is rich in minerals, gas and forestry.

Yet despite its natural wealth, Papua New Guinea suffers the ‘paradox of plenty’ or ‘resource curse’. This is where countries endowed with rich natural resources struggle to make effective use of them and end up with lower levels of economic development than countries without those natural resources. How could this be?

PNG is plagued by what the United Nations Development Program claim to be the most crippling ethical failure in international development: corruption.

Transparency International ranks PNG as one of the most corrupt countries in the world. Its PNG chapter states, “There is massive disrespect for rule of law in Papua New Guinea. Public servants and citizens alike lack the integrity to adhere to proper processes and respectful ways of conduct”.

Such assessments may however overlook some important strengths amongst PNG’s people, ones which may in time prove instrumental in corruption control.

The Ethics Centre delivers a broad range of ethics educational programs, including one package being delivering to senior PNG Officials, funded by Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Contrary to what some might guess, this training does not lecture participants about what is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. Instead, it identifies what is meant by ‘ethics’, what gets in the way of ethical decision making and mechanisms to integrate ethics into the governance of organisations and their various activities.

More research is showing the power of ethical leadership in building strong organisational cultures that are able to resist ethical failure (like corruption) and enhance corporate performance.

The program links personal and organisational ethical frameworks. Different factors are identified as influential to the ‘PNG mindset’ and decision making of public officials:

- Christian values

- Clan values

- Government values

- Global values

At times the training also includes instruction on specific techniques, such as conflicts of interest management and probity reviewing.

Instruction in these skills is growing in demand in Australia and abroad as government and corporations alike search for ways of winning back public trust and confidence.

In contrast to the past problematic approach of corporate leaders to ethics in the West, that is, as non-essential and nice-to-have, PNG officials demonstrated a sophisticated appreciation of the instrumental and social value of ethics in administration.

As facilitators, we learnt much about the ethical dilemmas and challenges confronting PNG officials, often on a scale many Australians would have difficulty comprehending. A person’s relationship with a clan, family, profession and government at times present complex dilemmas.

Yet these officials’ enthusiasm for honouring all these duties and appreciating their tangible and intangible worth appears undiminished. They appear to have missed the economic rationalist memo. And this is a real strength for PNG, something some commentators may be overlooking.

To help preserve this strength and to take advantage of it in countering corruption and other PNG challenges, The Ethics Centre is talking to potential partners about co-designing content with local officials and developing a train-the-trainer program.

We know local officials are enthusiastic for more of this training, indeed, it was the PNG Department of Personnel Management who requested education in ethical decision making for public servants. The average Net Promotor Score from participants on the program is 88 (of a score between -100 and +100), indicating high levels of satisfaction. We look forward to continuing our work with the Australian Government and the Government and people of PNG on this important initiative.

Lead photo by Stefan Krasowski

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The pivot: ‘I think I’ve been offered a bribe’

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

BY David Burfoot

David has worked in the not-for-profit, public and private sectors domestically and internationally for organisations as diverse as the United Nations Development Program, Deloitte, the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption and Sydney University. He has been an anti-corruption specialist with a number of government agencies and held senior positions responsible for corporate planning, change and internal communications.

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY David Burfoot 28 APR 2019

The Ethics Centre (TEC) has often been called upon to assist sporting organisations with ethical crisis.

The Ethics Centre recently took advantage of an opportunity to discuss two recent cases regarding ethical sport dilemmas with a group of HR Sport Executives. It was an enlightening experience and we’d like to share it with you.

As a reminder, TEC undertook two high-profile reviews of sporting organisations over the last 18 months, the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) and Cricket Australia (CA).

The first of these explored the comparison between sportsmanship and the ‘pragmatic’ or even gamesmanship* approach to its administration. Bringing the two approaches was problematic and culminated in disenchantment, frustration and an organisational culture that neither represented the best of sport or organisational administration.

The Centre delivered a warts-and-all report with 17 recommendations, all of which were accepted. Recent discussions with AOC reveal a major shift in the culture of the organisation over the last 12 months, under the leadership of CEO Matt Carroll and the Head of People and Culture, Amie Wallis. AOC staff need to be congratulated for what they have achieved.

The other engagement was with Cricket Australia, a culture and governance review in response to the ball-tampering incident at the Newlands Ground in South Africa during an international test match in March 2018. It was clearly against the rules.

The initial attempts of the players to conceal what they were doing is testament to this. But it wasn’t as clean-cut as that. The incident seemed to represent an attack on something sacred to Australians. Many fans reacted as if they were personally afflicted.

Our interviews and surveys of CA staff, players, cricket officials, sponsors and members of the public often explored the difference between sportsmanship and gamesmanship. Comparisons were drawn between ball-tampering, sledging and the underarm bowling incident in 1981 during a One Day International cricket match between Australia and New Zealand.

We recently had the good fortunate of being invited to a discussion about such issues with a group of HR executives, representing some of the major professional sporting organisations in Australia, from Horse Racing to Rugby, organised by Mercer Australia.

And of course we accepted.

We put to them the observation that when there is fraud in government, the actions are often labelled corruption, as they signify a greater social betrayal than a breach of the law. Fraud in the private sector doesn’t attract the same moral outrage and avoids the ‘corruption’ label, with one exception: sport. Sport also uses the word ‘corruption’ to describe fraudulent behaviour. We asked why.

The group started with the suggestion that people take sport personally, as we all feel part of it and we all feel like we own it. We play it to pursue the best in us, we barrack for our team, we involve our children in it and we use it as a tool to teach our children about values, about what is important in life.

We all feel obliged to have an opinion about it, perhaps as Australians. This is probably why people feel fraud in sport is a moral issue that goes beyond compliance with the law, a social ‘evil’ that the word ‘corruption’ better conveys. There was also the feeling that corruption is used because it reveals the interconnected network that comes with fraud in sport.

When asked about the dilemmas in sport more broadly, many spoke about the challenge players experience balancing their need to win and earn income, with their long-term wellbeing.

Players often hide their injuries to avoid being dropped from teams. These injuries are often physical, but sometimes they are mental. The period where an athlete is most successful financially is narrow. The pressure to sacrifice their long-term health as a result is real.

As HR professionals they also spoke of their dilemmas, when they need to balance advocacy for the individual player with the best interests of the company or business side of the sport. They spoke of this also in relation to the management of the team, when the coach feels the need to let someone play because their family is present, even though it may not be in the best interest of a win.

They spoke about how officials are tempted to overlook bad leadership of team leaders when the characters themselves raise the winning morale of the team. Some spoke about the challenges of being considerate of a person’s background, but also being clear that it did not excuse bad behaviour such as sexual harassment.

We see related dilemmas in other sectors currently under the public spotlight. It is accepted that the unique relationship between sport and ethics has been neglected by philosophers.

There may be much to be learnt by our experience of sport, and how its values are brought to the wider theatre of life. These discussions help us reach a better understanding about these relationships.

* Gamesmanship is built on the principle that winning is everything. Athletes and coaches are encouraged to bend the rules wherever possible in order to gain a competitive advantage over an opponent.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccines: compulsory or conditional?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Duties of care: How to find balance in the care you give

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Freedom of expression, the art of…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Capitalism is global, but is it ethical?

BY David Burfoot

David has worked in the not-for-profit, public and private sectors domestically and internationally for organisations as diverse as the United Nations Development Program, Deloitte, the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption and Sydney University. He has been an anti-corruption specialist with a number of government agencies and held senior positions responsible for corporate planning, change and internal communications.

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY David Burfoot 22 MAR 2019

Play fair or play to win. The interests of an individual player versus the team. Bad leaders who get good results.

These are just some of the common ethical tensions occurring throughout elite Australian sport. And they lead to corruption.

The Ethics Centre undertook two high profile reviews of sporting organisations over the past 18 months, the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) and Cricket Australia (CA).

Australian Olympic Committee

Our AOC review explored the comparison between sportsmanship and gamesmanship. Sportsmanship is the fair, honest and decent treatment of others in competition. Gamesmanship, on the other hand, is built on the principle that winning is everything. Athletes and coaches are encouraged to plot, ploy and bend the rules wherever possible in order to gain a competitive advantage over opponents.

Bridging the two approaches was problematic. It culminated in disenchantment, frustration and an organisational culture within AOC that neither represented the best of sport or organisational administration.

The Ethics Centre delivered a warts-and-all report with 17 recommendations, all of which were accepted.

Recent discussions with AOC reveal a major shift in the culture of the organisation over the last 12 months, under the leadership of CEO Matt Carroll and the head of people and culture, Amie Wallis. AOC staff need to be congratulated for their achievements.

Ball tampering and Cricket Australia

The other engagement was with Cricket Australia – a culture and governance review in response to the ball tampering incident in South Africa in March 2018, something that was clearly against the rules.

Initial attempts by players to conceal what they were doing was testament to this, but it wasn’t as clean cut as that. The incident seemed to represent an attack on something sacred to Australians. Many fans reacted as if they were personally afflicted.

Our subsequent interviews and surveys with CA staff, players, officials, sponsors and members of the public often explored the difference between sportsmanship and gamesmanship.

Comparisons were drawn between ball tampering, sledging and the underarm bowling incident in 1981 during a One Day International cricket match between Australia and New Zealand.

Sporting HR executives

We recently had the good fortunate of being invited to a discussion about such issues with a group of HR executives, representing some of the major professional sporting organisations in Australia, from Horse Racing to Rugby, organised by Mercer Australia.

We put to them the observation that when there is fraud in government, the actions are often labelled corruption, as they signify a greater social betrayal than a breach of the law. Fraud in the private sector doesn’t attract the same moral outrage and avoids the label of corruption. But there is one exception. Sport also uses the word corruption to describe fraudulent behaviour. We asked why.

The group started with the suggestion people take sport personally, as we all feel part of it and like we own it. We play it to pursue the best in us, we barrack for our team, our kids play it, and we use it as a tool to teach our children about values and what is important in life. We feel obliged to have an opinion about it, perhaps as Australians.

This is probably why people feel fraud in sport is a moral issue that goes beyond compliance with the law, a social ‘evil’ that the word ‘corruption’ better conveys. There was also the feeling that corruption is used because it reveals the interconnected network that comes with fraud in sport.

When asked about the dilemmas in sport more broadly, many spoke about the challenge players experience balancing their need to win and earn income, with their long-term wellbeing. Players often hide injuries to avoid being dropped from teams. These injuries are often physical, and sometimes mental. The period where an athlete is most successful financially is narrow. This creates pressure to sacrifice long-term health.

As HR professionals they also spoke of their dilemmas, when they need to balance advocacy for the individual player with the best interests of the company or business side of the sport. They spoke of this also in relation to the management of the team, when the coach feels the need to let someone play because their family is present, even though it may not be in the best interest of a win.

They spoke about how officials can overlook bad leadership when the characters themselves raise the winning morale of teams. Some spoke about the challenges of being considerate of a person’s background, but also being clear that it did not excuse bad behaviour such as sexual harassment.

We see related dilemmas in other sectors currently under the public spotlight. It is accepted that the unique relationship between sport and ethics has been neglected by philosophers.

There may be much to be learned by our experience of sport, and how its values are brought to the wider theatre of life. These discussions help us reach a better understanding about these relationships.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

BY David Burfoot

David has worked in the not-for-profit, public and private sectors domestically and internationally for organisations as diverse as the United Nations Development Program, Deloitte, the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption and Sydney University. He has been an anti-corruption specialist with a number of government agencies and held senior positions responsible for corporate planning, change and internal communications.

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 14 FEB 2019

James Baldwin was one of the great American writers of the twentieth century.

His elegant, articulate and keenly perceptive work bore witness to the hostile, day-to-day realities in which African Americans lived, and the psychological implications of racism for society as a whole.

His fifth novel, If Beale Street Could Talk, is no exception. Forty-four years after it was published, Moonlight director Barry Jenkins has adapted it for the screen.

A different type of love story

A hypnotic, visually sumptuous and intimate love story, Beale Street has little of the structure of a traditional romance. The film begins, for instance, with the generic arc of courtship already complete. We first see the two young protagonists – Tish Rivers and her boyfriend Alfonzo ‘Fonny’ Hunt – walking slowly together in a park, their affections clear and perfectly mirrored. Growing up as childhood friends in the Bronx, there was never a time they did not love each other.

The story instead bears testimony to the resilience of love, and the strength it endows those who have faith in it. Here, we witness its many forms arrayed against a vast, malicious and coldly impersonal system which is rigged to destroy black lives and fracture the most precious of bonds.

Barely a minute into screen time, the plot throws Fonny (Stephan James) behind a glass wall. He’s in jail after being accused of rape. To his accuser and certainly the police, his innocence is irrelevant. As a black man, his identity in the white cultural imagination is as a violent savage – he was always-already condemned, regardless of his actions. It is through this transparent barrier that Tish (KiKi Layne) tells him that she is carrying his child.

When the past and present merge

Following this revelation, the story diverges in two interweaving streams of past and present. One, filled with hope and secret joys, sees the young couple come to understand each other as man and woman, while nursing dreams of a future together. In the second narrative, hope is not a simple impulse but an inviolable duty, as their baby swells in Tish’s womb, Fonny’s case stagnates and despair threatens. Each scene is freighted with the viewer’s knowledge that the lovers’ destiny is not their own.

Tish’s tale

This second narrative is also very much Tish’s story, and shifts its focus to a different kind of love. Beale Street is most affecting in its portrait of the Rivers family, who support Tish wholly and will do whatever they must to fight for her and the new life within her. Regina King won a Golden Globe for her portrayal of Tish’s mother Sharon, who embodies a fierce, calm and indominable maternal courage. Her father Joseph (played with a rich, growling warmth by Colman Domingo) and older sister Ernestine (Teyonah Parris) readily take on the role of advocate and defender.

Their unity has its foil in Fonny’s family, the Hunts, who refuse to partake in any struggle they did not ask for. Headed by a spiteful and Godfearing mother, who curses her unborn grandchild and rationalises prison as a place in which Fonny can find the Lord, theirs is a pride born of self-serving weakness. The Rivers’ contrasting pride is one born of unassailable dignity and a determination to act, in spite of the odds arrayed against them.

“What do you think is going to happen?” asks Mr Hunt when Joseph lays out a plan for them to steal from their workplaces to help their children.

“What we make happen.”

“Easy to say,” Hunt protests.

“Not if you mean it,” Joseph levelly responds.

Emotional explotation

Through these characters, Beale Street puts forward the case for love as the single most steadfast bastion against the dehumanising machine of systemic oppression. Those characters without this vital force are vulnerable to emotional exploitation – betraying family and friends to protect themselves. Hunt’s mother sacrifices her son rather than align herself with his fate.

Fonny’s old friend Daniel also deserts him when his words could have saved him, his integrity broken by the terror of returning to a prison that broke him. And Fonny’s accuser is so traumatised, she is locked in a prison of her own pain, insensible and insensitive the suffering of others.

None of these individuals are free. Living in a constant wash of fear without refuge or reprieve has deprived them of their integrity, transforming them into actively complicit agents in the perpetuation of a racist structure. This, Baldwin’s story reveals, is perhaps the most wretched and insidiously effective mechanism of tyranny.

Racial tensions

Daniel is sure that white man is the devil. But Beale Street itself doesn’t espouse this view. At crucial junctures, white allies take risks to intercede against social, economic, police and court racial injustice. A Jewish real estate agent grants the lovers a path to an affordable home. An old storekeeper stands up to a reptilian policeman. And Fonny’s lawyer is a ‘white boy just out of college’.

At two hours, the film is languid and poetic, with gorgeous cinematography by James Laxton. The deliberate slow pacing and the use of frequent close-ups demands of the viewer they recognise the central (and very beautiful) characters as subjects. In a culture which frequently effaces black bodies, fetishises them, or arbitrarily fashions them into villains, these images are quietly radical. The film plays out between the steady gaze of the two lovers, and plays within the gaze of an audience that can’t look away.

Quietly significant too, is the film’s inclusion of moments which are superfluous to the plot, but vital to the immersive legacy of Beale Street. One, impossible to forget: Tish’s parents swaying before a jazz record in the family loungeroom, holding each other close, smiling in the new knowledge of themselves as grandparents to be.

Final thoughts

Opening in Australia on Valentine’s Day, Jenkins’ film is a tender dream of two lovers trapped in a too-real nightmare. It is not difficult to remember that this nightmare still torments the freedoms of racial minorities in America, ‘the land of the free’, and other nations too – whether they characterise themselves as progressive democracies or not.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How far should you go for what you believe in?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Nihilism

LISTEN

Relationships, Society + Culture

Little Bad Thing

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Banking royal commission: The world of loopholes has ended

Banking royal commission: The world of loopholes has ended

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 6 FEB 2019

Following the release of Commissioner Hayne’s royal commission final report on the banking and financial services sector, our Executive Director shares his take on the findings for the Australian Financial Review.

The Final Report of the Hayne Royal Commission is both unsparing and inspired.

Mr Hayne casts a wide net in his analysis of what went wrong in Australia’s banking and finance industry. However, there is one group on whom he pins ultimate accountability; the boards and senior executives of the entities whom he found to be at fault, “Nothing that is said in this Report should be understood as diminishing that responsibility. Everything that is said in this Report is to be understood in the light of that one undeniable fact …”

That is the unsparing part of the Report.

Kenneth Hayne is inspired in his injunction to all Australian business that it must apply some underlying principles, “These norms of conduct are fundamental precepts. Each is well-established, widely accepted, and easily understood.”

- Obey the law;

- Do not mislead or deceive;

- Act fairly;

- Provide services that are fit for purpose;

- Deliver services with reasonable care and skill; and

- When acting for another, act in the best interests of that other.

A dominant theme in Mr Hayne’s final report is that it is time to eliminate the law’s own exceptions to these principles – a series of ‘loopholes’ – often the product of political convenience – that allow the underlying principles to be violated by those with the wit, means and licence to do so.

There is a subtle quality to Mr Hayne’s arguments on this point. At no time does he suggest that ethical commitments should be elevated above compliance with the law. Indeed, he is clear that he opposes that approach. However, he makes it clear that the Law must conform with ethics – in the form of ‘underlying principle’.

The implications of this for the targets of his harshest criticism – boards and senior executives – are profound. For too long, it has been possible to ease through a loophole and take comfort from the fact that questionable (and profitable) conduct was ‘strictly legal’. That approach has cost us all dearly.

The fact that a loophole was available to be exploited does not mean that it should have been. The capacity to exercise ethical restraint (not to do everything that is possible) was always latent within the ranks of boards and senior management.

To be fair, we should acknowledge that boards and senior management have often exercised that capacity. We will never know (and credit will never be given) for the many cases of good judgement that have prevailed. Unfortunately, in the current environment, a multitude of good decisions counts for little when compared to the relatively few, but emblematic, cases of ethical failure – some of which may also have been unlawful.

Ethical failure occurs when core purposes, values and principles are betrayed. On some occasions this is done in a knowing and deliberate manner. More often, the cause is a failure of culture and governance (both intimately linked) that leads an organisation to ‘sleep walk’ into an ethical ‘death pit’.

Recognising this, Commissioner Hayne recommends that:

All financial services entities should, as often as reasonably possible, take proper steps to:

- Assess the entity’s culture and its governance

- Identify any problems with that culture and governance

- Deal with those problems, and

- Determine whether the changes it has made have been effective

In doing so, Hayne supports and extends the approach already adopted by APRA and ASIC by looking beyond ‘risk culture’ to evaluate the whole.

The Ethics Centre is a pioneer in the development and application of world-class tools for undertaking precisely the kind of evaluation being recommended by Hayne. This approach should not be limited to banking and financial services. It is essential for all organisations – whether in the private or public sectors.

The trouble is that boards and senior managers are often deeply reluctant to look into a well-polished mirror that reveals the truth about their organisation. Instead, they look to those who offer a ‘magic mirror’ that always reflects the comforting myth that you are the ‘fairest of them all’. It takes a certain kind of moral courage to ask for the truth. Perhaps Kenneth Hayne has strengthened the sinews of corporate Australia.

We will see!

Australia was one of the first countries to develop an ethical framework for banking and finance. The Banking + Finance Oath was created in the aftermath of the global financial crisis – at a time when all seemed to be relatively rosy on the domestic front.

The great disappointment was that so few people took up the opportunity to commit to the ‘underlying principles’ on which the BFO is based. Perhaps too many people saw that reality fell too short of the ideal.

If ever there was a time to make something better, it is now. In the wake of the Hayne royal commission, it is time for the ethical majority, working within banking and finance, to step up. Whatever your role or seniority – it’s time to own what is noble in the aims of banking and finance and to give life to its ideals.

Embrace underlying principle, measure and achieve alignment, exercise ethical restraint, regain trust. Do so in the expectation of profit and to earn that most elusive of rewards: a good name.

That is the opportunity that lies latent in the recommendations of the Hayne Report.

Dr Simon Longstaff is executive director of The Ethics Centre

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Between frenzy and despair: navigating our new political era

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics Explainer: Aesthetics

Aesthetics is the philosophical study of art. If you think about what is enjoyable, or valuable about artworks, and why art is important, then you are considering issues to do with aesthetics.

The study of aesthetics is tricky because there are so many different kinds of artworks and it is difficult to think about what they have in common or how they should be categorised or judged. A seminal question in the field of aesthetics is ‘what is art?’ – how ought art be defined? And this question alone has various answers depending on which theory is being applied.

Art defined.

Art includes sculpture, painting, plays, films, novels, dance and music. And it isn’t always clear what the category of art excludes – in large part because artists are always pushing boundaries. The creative nature of art sees works or objects being considered as ‘Art’ that provoke shock, outrage, censorship or exclamations of ‘That’s not Art!’.

Just think about the first time Marcel Duchamp tried to display an artwork called ‘Fountain’ in 1917. The urinal, a ‘found object’ was signed by the artist ‘R. Mutt, 1917’, and caused a riot of disagreement as to whether art must be created or made with one’s own hands or whether it can be intentionally chosen and displayed.

Is it the creation or the reception of the artwork that matters the most?

Who decides whether something is a work of art? Is it ‘the artworld’ of experts and critics? Is it the artist? Or is it the viewer? Many viewers may not understand what they are seeing or may not truly appreciate the skill involved in creating a particular artwork.

For instance, the first time one looks at a Rothko painting, which may appear as a blank canvas painted with a couple of coloured squares, a viewer may think, ‘I could have painted that!’ It is only with an understanding of Rothko’s technique that one may start to appreciate the effort he put in to create it.

And even if we appreciate the skill and effort an artist exerts, we may or may not feel any particular ‘aesthetic experience’ when looking at a piece of abstract or contemporary art, while watching an opera, or while reading a novel by Dostoevsky.

An individual perspective

One’s experience of art is subjective as individual tastes differ. And yet, if we are to claim that some artworks are better than others, or explain why some artworks stand the test of time and are valued by generations, we need to refer to some standards by which to judge them. Are there any features artworks must have to be considered as art? Should artworks be beautiful? Do they need to be moral? And who decides whether or not they meet this criteria?

Despite the historical interference by political and religious leaders who worry about the influence art may have in a society, debates as to what constitutes good art, aesthetically and even morally, has been a matter for debate for aestheticians.

Sometimes it takes time for something to be considered art, let alone to be considered aesthetically valuable. Think about Banksy’s graffiti art. It has been the case that unsuspecting council workers have removed graffiti from the side of a building only to later discover they have inadvertently eliminated a valuable artwork. And yet, not all graffiti is considered art or deemed valuable.

In fact, the opposite is true!

What makes Banksy an exception?

View this post on Instagram. "The urge to destroy is also a creative urge" – Picasso

A post shared by Banksy (@banksy) on

Definitions of art have changed over time. Traditional views of art usually cited ‘beauty’ as an important feature of artworks, but that has since altered. Indeed, is one meant to find the displayed urinal ‘beautiful’? An artwork need not be beautiful to be skilfully executed, meaningful and valuable.

The value of art in society

The defenders of art and its unique role in society usually claim art should be valued for its own sake. Aesthetic value is not to be valued instrumentally, for its financial value or for its status, or even for what we can learn from it or because it is deemed morally ‘good’. It may do any and/or all of these things, or none! Art is valuable because it affords an aesthetic experience.

In its creation and reception, as a form of self expression, imaginative engagement, cognitive as well as affective experience, source of individual and social reflection and contemplation, art has always been central to human life. If it is true that the arts capture and express something unique, and aesthetic experience is intrinsically valuable, then we should consider the place for the arts in society and support and value artists for the important contribution they make.

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is a senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING