Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Daniel Finlay 8 JAN 2026

As a 16-year-old, I argued with my vegan friend about the various faults in his logic: how he couldn’t possibly be healthy, how we were meant to eat animals, and all the rest. I never could have imagined how embarrassed it would make me many years later.

I wasn’t particularly familiar with veganism as a teenager, but I have always loved animals. While the fervour to prove it wrong dissipated, my knowledge and exposure to it remained very minimal, like most people’s. A little later, I briefly dated someone who was vegetarian, who inevitably but mostly passively increased my exposure and knowledge. I decided to start looking into the validity of my confident preconceptions and realised that they were either completely unfounded or just exaggerated. It wasn’t many years later when I woke up in the middle of the night and decided that I needed to change my actions.

Veganuary

Coincidentally, 2014 was the year that I began changing my lifestyle to better reflect my values – the same year that a British nonprofit began an annual challenge called Veganuary: a call for people to try eating as if they were vegan for the first month of the year. You sign up for free and are provided with daily emails for a month that include information like recipes, cookbook pages, meal plans and general advice for how to navigate the change in habits.

All of this is well and good if you’re already curious about the idea of reducing your animal consumption, but what if you’re not? Let me try and pique your curiosity.

Why you should care

You might already consider yourself someone who cares. Most people do love animals in theory. If you see an injured bird, a run-over kangaroo, or an abused dog, you’re likely to have a compassionate response. But decades of socialisation, billions of dollars in misrepresentative marketing, and the ever-increasing distance between consumers and production means it’s easier than ever to ignore how our values contradict our everyday actions.

So please indulge me by considering the following responses to common arguments for eating animals.

To begin, let’s get the practical stuff out of the way:

Where will I get my protein? We need meat/dairy/eggs to give us all the nutrients we need.

This argument is as unfounded as it is ubiquitous, and one I wasn’t immune to earlier in my life either. Unfortunately, agricultural lobbying groups are much better at getting into the minds of average consumers, otherwise it would be common knowledge that all major dietetic associations agree on the safety (and benefits) of balanced vegan diets (and all types of vegetarian diets). That’s not to demonise the health of any other kind of balanced diet – you can be perfectly healthy on a regular omnivorous diet – but the ethical argument for showing compassion to animals doesn’t require it to be healthier than eating animals, only that it’s not bad for us. The overwhelming evidence shows that it is not.

The question is not “can I?” but “how would I like to?” That’s why something like Veganuary is such a good introduction, because having the initial support to change your shopping and eating habits makes the transition much easier.

It’s too hard.

Maintaining a balanced omnivorous diet is also too hard for most Australians – doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try! Sometimes we have to do difficult things for our own good or the good of others. You will likely find though, as I did, that the hardest part of changing your lifestyle is the social aspect. People can be judgemental, defensive, aggressive, and downright cruel despite your best attempts to minimise the impact that your choices have on others. Contrastingly, changing habits can be difficult in the short term but they soon become second nature. Staple recipes are easily replaced and substituted with similar-tasting alternatives.

Okay so maybe it won’t make my life worse personally, but it’s so bad for the environment. All those almond trees and soy crops use so much water and cause deforestation. We need animals to feed everyone.

Almond water usage obsession arose initially during the early-mid 2010s Californian droughts, where the majority of the world’s almonds are grown, at a time when almond consumption was skyrocketing. I’m not going to rush to almond’s defense, as we should definitely be prioritising mass consumption of soy and oat milk instead, but if we do want to compare it to the animal-derived alternative then almond is still better, using almost half the amount of water and causing almost five times less CO2 emissions.

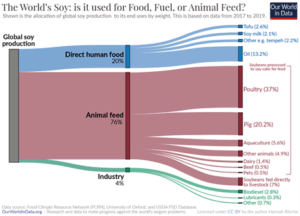

The idea that the soy used for soy milk, tofu, tempeh, etc is driving deforestation is another common myth:

“In fact, more than three-quarters (77%) of global soy is fed to livestock for meat and dairy production. Most of the rest is used for biofuels, industry, or vegetable oils. Just 7% of soy is used directly for human food products such as tofu, soy milk, edamame beans, and tempeh.”

Even further than this, the amount of land cleared for cow pastures is over 7 times that for total soy production. If you’re worried about the environment, reducing or eliminating your animal consumption is the best place to start.

I’ve heard that farming vegetables kills more animals (mice, insects, etc) than eating meat, so if we care about animals, we should really keep eating them.

As we’ve seen, most of these crops go to feeding farmed animals, which means that it is still much preferable to consume these crops ourselves, rather than producing magnitudes more to feed other animals to be killed. The same logic applies if you’re someone who would like to argue that plants have feelings, too.

If you’d like to read more about the arguments against veganism, please see here.

Starting the year right

The overarching consideration here from an ethical standpoint is to reduce unnecessary suffering. For me, this comes mainly from a consequentialist perspective. Suffering is bad, we want to see and contribute to less of it. Eating meat, dairy and eggs necessitates immense amounts of unnecessary suffering and death (even if you think killing an animal that lived a good life is okay, we cannot feed the world with that kind of production – factory farms exist to fill the demand). Therefore, we should stop contributing to that demand.

My suggestion isn’t to make a permanent change overnight, but simply to try something new. You can join millions of other people around the world who are trying out a month of reduced animal harm through Veganuary. Or maybe you’re someone who says things like “I could go vegan except I love cheese too much”. Well, use the start of this year to try being vegan except for cheese. You’ll probably find that the hardest part of doing good is taking the first uncomfortable step.

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why compulsory voting undermines democracy

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

The Bondi massacre: A national response

The Bondi massacre: A national response

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 2 JAN 2026

What is the best response to the massacre of Jewish people at Bondi Beach? I ask that question knowing that the best response may not be the most popular.

For example, the debate about whether or not there should be a Federal Royal Commission has made it abundantly clear that people can reasonably and sincerely disagree about what should be done. The same debate has also revealed that some people have deliberately (and others inadvertently) politicised what should be a matter of broad national consensus – with the ideal response being of a kind that meets a number of core criteria. If ever there was a time to set politics aside in favour of a singular compassion for the Jewish Community and a high regard for the national (rather than partisan) interest, then this was it.

Although united in grief and anger, the Jewish Community is not of a single mind about what should now be done. Differences of opinion are to be expected. It is wrong to expect any group of people to hold a common position simply because they share aspects of identity. Furthermore, while the Jewish Community was the explicit target of the terrorists’ attack – and bore the brunt of the carnage – they are not the only Australians to have been wounded by the murderous rampage that took place on the first night of Hanukkah. The whole nation has been scarred … and now a host of other communities are left to ask, “What caused this to happen? What can be done to prevent this in the future? Who’s next?”.

Bearing all of this in mind, I have come to the conclusion that the best possible response cannot lie in a single measure. Instead, I think the whole nation will be best served by a multi-layered approach. Importantly, such an approach would see the Commonwealth Government go well beyond where it currently stands – but in a direction that, I propose, eclipses what has been called for so far.

Each element of our national response needs to be ‘fit-for-purpose’; tailored to meet a specific need. So, what are those needs? First, the Jewish Community needs answers about what caused the Bondi Massacre – and how it might have been prevented. Second, the nation needs to know if there is anything more that could have been done by our national intelligence and security services to identify and therefore prevent the terrorists from acting. Third, we all need to understand the genesis of hate-crimes (of which antisemitism is an especially virulent, but not the only, form) in Australia – and how this might be combatted in favour of resilient bonds of social cohesion that would enable us to maintain a vibrant, multicultural society in which every person can flourish, free from fear or prejudice.

The first need will be met by the proposed NSW Royal Commission that enjoys the unfettered support of the Commonwealth Government and its departments and agencies. That support needs to be offered with the whole-hearted endorsement of the Prime Minister and unwavering direction from his Cabinet. The Commonwealth should offer binding undertakings to hold to account any of its officers, including members of past and present Commonwealth governments, who are found by the Royal Commission to have contributed to the events in Bondi – either by act or omission. Under these conditions, the proposed NSW Royal Commission will be in a position to address all of the issues arising out of the specific terrorist attack of 14 December.

The second need will be met by the Richardson Review. It will be focused and completed within a relatively short period of time. Anyone who knows or who has worked with Dennis Richardson AC knows that the inquiry will be thorough and exacting. The general public may not see all that he finds and recommends – as national-security considerations will take priority for the sake of us all. However, we can trust that nothing will be overlooked.

The third need can be answered by a National Commission of Inquiry. Unlike a Royal Commission that has a defined legal form – and often seeks to find fault and punish wrongdoers – this Commission would be required to look at the deeper causes of which the Bondi Massacre is a treacherous and violent eruption. Those causes affect multiple communities – indeed, they are a cancer eating away at the soul of Australia. The Commission should have broad powers – but it should especially be enabled to convene individuals and groups from across the nation – to hear the stories of what is happening, the impact of hatred and what can be done to prevent this from metastasising into violence.

In my opinion, we should also put the lens on multiculturalism so that rather than merely celebrating the worthy characteristics of separate communities, we learn how to strengthen the bonds between them – and commit to doing so in practice.

I know that there will be some people in the community, especially the Jewish Community, who would prefer to see the Prime Minister establish a Royal Commission to investigate the scourge of antisemitism. There is something distinctive about the hatred directed at Jews – almost unfathomable given its dark persistence over millennia. However, what I have in mind would allow the Jewish experience to be given full voice – but in conditions where we see how it relates to the experience of others in the community. In itself, that will help forge common bonds – as always happens when we see ourselves reflected in the lives of others. Given the searing nature of events, a proposed Commission should prioritise its examination of antisemitism, before all else, reporting on this within twelve months of being established.

In putting forward this proposal, I sincerely believe that nothing will be lost – and much will be gained. I hope that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese might establish a Commission that embraces the whole nation – in all of its marvellous diversity – in order to find light at this terrible moment of darkness.

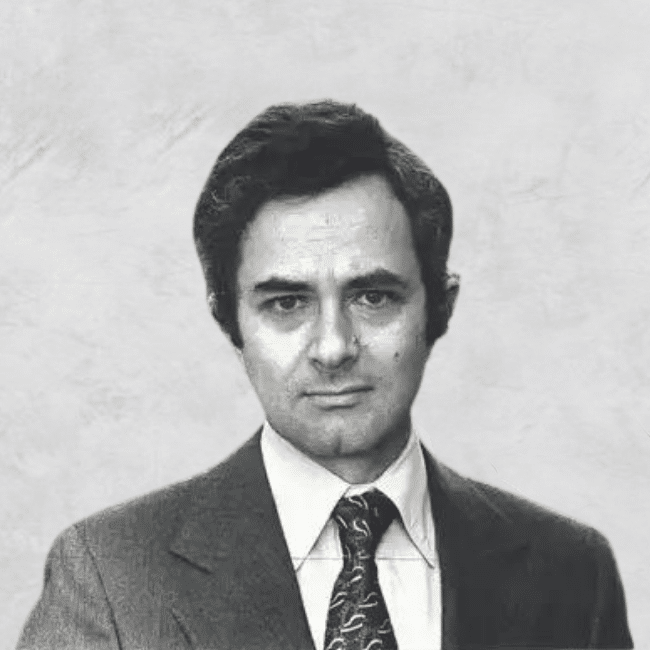

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

What comes after Stan Grant’s speech?

Feeling our way through tragedy

The emotions we feel in the wake of a tragedy, like the Bondi Beach shooting, are as intense as they are natural. What matters is how we act on them.

It was a typical relaxed summer Sunday evening. We had just finished dinner and I was on the couch watching TV while my wife was in the other room catching up with family over a video call. Then a wayward notification caused me to idly glance at my phone. A headline popped up on the screen, I caught my breath and switched on the news.

And in a matter of moments, the peace was shattered as the news came in that two men had opened fire on a group of people enjoying their own relaxed summer Sunday evening celebrating Hanukkah on Bondi Beach. A wave of emotions followed: horror, grief and outrage, followed by a gnawing sense of uncertainty. Were any of my friends or family there? What could drive someone to commit such an atrocity? Is anywhere safe?

These are typical emotions when confronted by sights such as these. The feelings well up from our bellies, fill our chest, overwhelm our minds. They are as primitive as they are potent. And they demand closure.

Yet emotions like these can be channelled in many different ways. Some forms of emotional closure are healthy. But other courses can end up causing more harm, either to ourselves or to others. And while it is easy to let these types of emotions consume us, it is crucial that we act on them ethically.

Horror and hope

Many creatures experience fear. It is a natural response to threat, and a potent motivator to remove ourselves from its presence. But our species is unique – as far as we know – in our ability to experience horror. Horror is also bound up with shock, disgust and dread. It is a response to the most acute violations of our humanity. The thing is, we don’t only experience horror when we are under threat, but when someone else is threatened. Underneath horror is a recognition of our shared sacred humanity and a revulsion at its desecration.

The problem is that the sense of horror triggered by an attack such as that at Bondi Beach on 14 December 2025 can change the way we see the world. In our aroused state, we become hyper vigilant to cues that might indicate future threats. And those cues will be associated with the location of the shooting, perhaps making us reluctant to go to Bondi Beach, or even causing us to fear going out in public at all.

If we allow emotion to take over, it can make the world feel less safe and other people seem more threatening.

But that response overlooks the fact that, despite the magnitude of the atrocity, this is an incredibly rare event perpetrated by only a few people. The fact that our feeling of horror is shared by millions of others around Australia and the world should serve as a reminder that the vast majority of us care deeply about our shared humanity, and it is those people that make the world safe. Should we retreat from the world out of fear, we do ourselves, and every decent horrified person around us, a disservice.

Following horror might be an overwhelming grief at the pain and suffering inflicted upon innocent people. This grief can lead to a feeling of powerlessness and despondency, one that again nudges us to retreat from the world. But, as painful as it is, our grief is proportional to our love. If we didn’t care for the lives of others – even people we have never met and will never know – then we wouldn’t feel grief. So we needn’t let grief strip us of our agency. Instead, we can let it remind us to lean into love and motivate us to reach out to others with greater patience and understanding.

A fire for justice

Possibly the most dangerous emotion in this list is outrage. This is another primitive emotion that motivates us to correct wrongdoing and punish wrongdoers. Outrage demands satisfaction, but it’s often not fussy about how that satisfaction is achieved. Great evils have been committed at the hand of outrage, and great injustices perpetrated to satisfy its call.

We must acknowledge when we feel outrage but be wary of its call to immediately find someone to blame and punish. Within an hour of the shooting, the media was already mentioning a name of one of the attackers, feeding the audience’s hunger for justice. But in its haste, it caught up an innocent man who then experienced unwarranted threats. Others rushed to blame the authorities for failing to prevent the attack or refusing to combat antisemitism.

Even when things look clear at first glance, we must remind ourselves that it’s all too easy to blame the wrong person or seek punishment just for the sake of satisfaction. And sometimes there is no one person to blame. Sometimes the causes of an atrocity are complex and interlaced. Sometimes there were multiple causes and nothing anyone could have done to prevent it. So we must temper outrage with a deeper commitment to genuine justice, lowering the temperature and working to understand the whole picture before calling for punishment.

I acknowledge that it can be difficult to pause in the heat of the moment, especially when we only have a fragmentary grasp of what’s going on and what caused it.

In times of uncertainty or ambiguity, we crave clarity and certainty. We seek out and latch on to the first available narrative that seems to make sense of a great tragedy. We like the feeling of being certain more than we like doing the work to interrogate our beliefs to ensure they warrant certainty.

We thus have a tendency to be drawn to narratives that align with our pre-existing beliefs or biases. Uncertainty and ambiguity can be like a Rorschach test. The patterns we see tell us more about ourselves than reality. If we don’t want to exacerbate injustice by generating or sharing false narratives that can cause real harm, we need to learn to sit with the uncertainty and dwell in the ambiguity. We are not naturally inclined to do so, but that only means we need to practice getting better at it.

The very fact we typically experience emotions like horror, grief, outrage and uncertainty speak to our deeper humanity. They speak to how much we care about others and living in a world where everyone deserves to be safe and thrive. If we allow the better angels of our nature to rise to the surface, and resist the temptation to satisfy our emotions in ways that cause more harm, we can respond in a genuinely ethical way.

Image by ZUMA Press, Inc / Alamy

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: WEIRD ethics

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

A message from Dr Simon Longstaff AO on the Bondi attack

A message from Dr Simon Longstaff AO on the Bondi attack

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 15 DEC 2025

On behalf of everyone who works at The Ethics Centre – our board, staff and volunteers – I am writing to all of our members and supporters to offer our heartfelt sympathy to those affected by the terrorist attack that took place, in Bondi, last night.

Some might observe that this is not the biggest atrocity to have taken place in the world this year. However, I do not believe that atrocities should be ranked according to the numbers of people killed and maimed. What defines such events, as evil, lies in the perpetrator’s intent to harm people; not because of what they have done, or what they believe – but simply because of who they are.

Last night was not an indiscriminate act of terror. People were targeted merely for being Jewish – men, women, children … people of every type and description. Whether you lived or died had nothing to do with one’s politics or opinions about the world. Simply being Jewish – indeed, simply being in the midst of the Jewish community – was enough for you to be targeted. This was antisemitism in its most violent form.

As I write this note, we still do not know what motivated the terrorists. However, nothing can make good what they did – cold-blooded murder can never be justified … no matter who does the killing, no matter who is the victim, no matter how many reasons are advanced.

Now, I fear that the cycle will take another turn for the worse. Members of other communities will fear that they will be tarred with the same brush as the terrorists – no matter what they have done, no matter what they believe – but simply because of who they are.

Surely, surely it is time to stop this vicious wheel from turning.

At The Ethics Centre, we believe in the intrinsic dignity of all persons – without exception. This recognition has no boundaries and, difficult as it may be, must extend even to those who visit terror upon us. At times like this, we should embrace our common humanity – and not give way to those who would stoke and exploit divisions for their own ends.

Many people will be hurting today – even if far removed from the carnage. Many will be angry or confused, or feeling helpless or just numb. I think I have felt all of those emotions since the tragic events of last evening began to unfold. However, in the midst of all of this, we can hold onto the fact that what happens next is not inevitable.

Our governments will take the lead in providing security – but only we, the people, can create the conditions of ‘belonging’ in which every person can feel safe in the warm embrace of a society that recognises the intrinsic dignity of all. In this, let’s not forget the bravery of those who confronted the gunmen, who rendered first aid, who comforted the dying or offered sanctuary within their homes. These people show what is possible when the good in us comes forth.

Making and sustaining just such a society – even in the face of terror – is what each of us can do. I hold onto that – and in the midst of pain and confusion hope you might do the same.

Image: Paul Lovelace / Alamy

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What happens when the progressive idea of cultural ‘safety’ turns on itself?

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Aubrey Blanche 20 NOV 2025

In an age where emotionally charged information travels faster than ever, the ability to critically evaluate what we read, watch, and share is the cornerstone of responsible citizenship. It’s essential that we’re able to strengthen our media literacy skills to detect bias, maintain trust and safeguard the integrity of public discourse.

Since the rise of generative AI, we have become inundated with content. It’s easier to generate and disseminate information than ever before. When content is cheap, it’s curation and discernment that becomes ever more critical.

And this matters – how information travels influences policy, the bounds of acceptable discourse, and ultimately how our society functions. This means that each of us, whether a social media user, producer of a major national news program, or just someone chatting with a friend, has an obligation to ensure that the truth we share contributes to human flourishing.

What is verifiable?

The reality is that a huge amount of the information we have access to is, well, fake. Media literacy equips people to recognise bias, detect misinformation, and understand the motives behind content creation. Without these skills, we and those around us become vulnerable to manipulation, whether through sensational headlines, deepfakes, or algorithm-driven echo chambers.

Verifying information before sharing is a critical part of media literacy. Every click and share amplifies a message, whether true or false. For example, deepfakes of Scott Morrison and other politicians have been used to perpetuate investment scams. When inaccurate information spreads unchecked, it can fuel polarisation, erode trust in institutions, and even endanger lives. Taking a moment to analyse the source, check for corroboration in other trusted places, and question the credibility of a claim is a small act with enormous impact. It transforms passive consumers into active participants in a healthier information ecosystem.

Whose truth?

What we see as objective is intrinsically shaped by the voices we are exposed to, and how often. This is as true for our social media feeds as it is for the nightly news. The messages that reach us are all in some way biased, meaning that they possess some kind of embedded agenda. But what we most often mean when we talk about bias, is a systematic and repeated filtering or skewing of information to conform to a particular or narrow agenda or worldview.

Because of this, we should be wary of potential bias when issues are covered by individuals or organisations with financial or political interests at stake. For example, jurisdictions around the world are currently wrestling with questions of how training large language models (LLMs) relates to fair use of copyrighted work. In Australia, the government recently ruled out a special exception for AI models to be trained on Australian works without explicit permission or payment. While there was public consultation conducted, prominent voices didn’t all agree with protecting the labor and output of creators as a priority.

Before the federal government made the determination, powerful members of the technology industry were consulted by journalists for their views on how the interests of AI labs and creators should be considered. These voices included those whose financial holdings include investments in the type of AI companies (and their methods) being discussed. Platforming voices with these interests has important implications for setting the terms of the debate as potentially more pro-technology, rather than encouraging a balance of perspectives.

While this specific issue is critical because it’s an issue that affects all of us, it also illustrates a way that we can practice media responsibly.

When we are sharing information, we should consider the interests and ideological alignment of those who are sharing.

Where possible, we should seek to provide a balanced set of perspectives, and ideally one in which any conflicts of interest are clear and disclosed.

Who gets platformed?

There is no free marketplace of ideas. The question of what voices and perspectives are platformed and held up as truth, whether in the media or on our feeds, greatly impacts our our own narratives of events. For example, since October 2023, more than 67,000 Gazans have been killed by Israeli forces. While the genocide has received significant media coverage, the perspectives of people impacted haven’t been equitably represented in mainstream media sources. Recently, a study found that only one Palestinian guest had been booked to share their views on major US Sunday news shows (which set the national agenda) in the last 2 years. In the same period, 48 Israeli guests had been given airtime.

If we assume that Israeli guests do not have a monopoly on the truth, this pattern looks alarming. While this study didn’t speak to the views of the guests, a reasonable person would assume that such a skew in the identities and affiliations represented present a rather one-sided view of events on the ground.

In this case, the platforming also speaks to the relative power of the perspectives. Despite the Palestinian community having the greatest lived experience of harm, their voices are effectively silenced. As we consider from whom we share information, we should always consider the following questions:

- Which individuals or groups have greater access to institutions – media or otherwise – to share their experience?

- In the case of conflict, are opposing forces equally powerful (eg in terms of financial resources, alliances, etc)?

- Who is marginalised, and what is the impact of not platforming that voice?

In today’s media environment, we are flooded with information. This means that the responsibly each of us must take in our sphere of influence has increased proportionally. In order to act as responsible members of our community, we must question which voices we’re highlighting.

BY Aubrey Blanche

Aubrey Blanche is a responsible governance executive with 15 years of impact. An expert in issues of workplace fairness and the ethics of artificial intelligence, her experience spans HR, ESG, communications, and go-to-market strategy. She seeks to question and reimagine the systems that surround us to ensure that all can build a better world. A regular speaker and writer on issues of responsible business, finance, and technology, Blanche has appeared on stages and in media outlets all over the world. As Director of Ethical Advisory & Strategic Partnerships, she leads our engagements with organisational partners looking to bring ethics to the centre of their operations.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ethics on your bookshelf

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Should we be afraid of consensus? Pluribus and the horrors of mainstream happiness

Should we be afraid of consensus? Pluribus and the horrors of mainstream happiness

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 12 NOV 2025

Partway through Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the author neatly summarises one of the more troubling questions that undercuts civilisation: is it ethical for widespread happiness to come at the expense of the discontent of select individuals? Or, to put it simply: do the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few?

“Let’s assume that you were called upon to build the edifice of human destiny so that men would finally be happy”, the troubled Ivan Karamazov says. “If you knew that, in order to attain this, you would have to torture just one single creature, would you agree to do it?”

That one question has been probed and explored time and time again in the years since Karamazov was published, most notably in Ursula LeGuin’s sci-fi story The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, in which the happiness of a flourishing city depends totally on the torture of a young girl. But it has perhaps never been as thoroughly – not to mention amusingly – explored to the extent that it is in Pluribus, the new sci-fi show from Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan.

In Gilligan’s re-telling, near-global happiness is an external force: a virus of sorts, which turns the world’s population into a hive mind of mutually contented drones. The one miserable, unlucky individual whose perpetual unhappiness sets her apart from the mainstream: Carol Sturka (Rhea Seehorn), who appears to be immune to the virus. Or rather, temporarily immune, given much of the early episodes of the show follows the rising, blackly comic threat of the hive mind searching for ways to make Carol one of them.

“Once you see how wonderful it is….” a member of the hive mind tells Carol early on, speaking to her directly from her television set. The hive promises happiness, peace and the end of all human conflict. What they also represent: the tyranny of mainstream thought, an enforced and established consensus where majority rules, no matter how discontented outliers might be. And where happiness itself is dangerously considered the main goal of all human existence.

The problem with happiness

One of Gilligan’s masterstrokes is to set Carol out of the mainstream even before the virus spreads. When we meet her, she’s a beloved romantasy author who can’t stand either the mindless content that she churns out, or the horde of rabid fans who adore her. In the first episode, her business/life partner Helen (Miriam Shor) mocks Carol’s dislike of adulation, teasing that she’s a perpetual miser, illogically rejecting the good time that’s being offered to her.

But when the mainstream offers mere happiness, we should reject it, as both Gilligan and Dostoyevsky seem to suggest. A life of contentment and fitting in with the crowd isn’t an ethical good in and of itself. As the rise of increasingly deranged social media slop proves – the kind of quick dopamine fix provided by TikTok – there’s so much more to life than merely being entertained.

The person who sits in their room all day watching Instagram reels could conceivably be very happy, but wouldn’t we all suggest that they might want more? Should they in fact pursue something greater and more important than simply having a good time?

This is the threat posed by Pluribus’ hive. In an ideal world, happiness should be a kind of side effect of good, not something to be pursued blindly for its own sake. As in, happiness should be what happens when we achieve virtuous behaviours – when we care for others, or pursue a flourishing life. And it certainly should not be enforced by the mainstream at the expense of individual freedoms and wants.

Even as Pluribus’ plot progresses, and it is revealed that Carol’s unhappiness is a very literal threat to the hive – when she lashes out at them, members of the hive abruptly die – the needs of those who sit in the mainstream should never be held above the deep unhappiness of those who also must operate within the world. Not only because enforcing the desires of the collective onto the individual is a harm in itself, but because sometimes – maybe even often – the desires of the collective aren’t particularly desirable.

In praise of conflict

Pluribus slowly encourages us to be suspicious of the idea that the hive are actually as happy as they claim to be. Do we really think that happiness is only a flood of dopamine throughout our body? If so, then as the philosopher Robert Nozick once asked, wouldn’t we therefore choose to step into a machine that did nothing but probe our dopamine receptors for all eternity, living an artificial life where we submit to being little more than switches that can be flipped in order to produce joy?

It doesn’t seem like many of us consider happiness only that. Happiness is what happens when we go to the other side of hardship; when we set ourselves goals and then achieve them. Ultimately, it’s a response to conflict and unhappiness, not the absence of conflict and unhappiness altogether.

Enforced mainstream happiness isn’t just ethically harmful for those who have it enforced upon them; it might be harmful to those who actively want it.

In the age of AI, these issues have never been more timely. In fact, Gilligan himself seems aware of this: each episode of Pluribus ends with a message, hidden in the credits, that reads, “this show was made by humans”.

We live in an era where tech companies constantly promise us that AI will bring ease, contentment, and the ability to fit in with our co-workers, friends and family – with the collective. Even if AI can do our jobs for us, or write tricky text messages to our loved ones, decreasing our discomfort, why would we even want that?

Now more than ever, we should follow Carol’s lead and become perpetual sourpusses. As it turns out, being a grump might be one of the most ethical things of all.

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Society + Culture

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Sex ed: 12 books, shows and podcasts to strengthen your sexual ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Isha Desai 27 OCT 2025

I’m sitting on a low brick wall at a party next to my date. Twenty-something boys and girls mill around, drink in hand, most of them in couples. One man clocks the boy sitting next to me, approaching us with a wide grin: “he’s a good one”.

The man is talking to me. Minutes later a girl rushes over, taking my hand in hers with a squeeze: “he’s one of the nice ones”. It would take another four months of dating before I realise that being a ‘good guy’ is very different from being a kind one.

The terms ‘good guy’ or ‘nice guy’ have been in my consciousness for two decades: a blanket seal of approval given to people (typically men) who display surface-level qualities of respect, decency and likeability.

In The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, bell hooks characterises this as a mask. The ‘good guy’ mold can distort participation in oppressive patriarchal systems. One of the largest ethical implications of this term is that it paints men as a binary. They are either a ‘good guy’ or they are a ‘bad guy’. It creates cognitive dissonance when a ‘good guy’ is complicit in the exact structures they claim to reject. The implication of this is a lack of accountability, a sense of confusion and feeling attacked when these men are presented with information that misaligns with their internalised and reaffirmed sense of self.

I always wondered, why is simply being ‘good’ heralded as praise for men? As if the expectation is that they are bad, and when they surprise us with respect they jump to a pedestal as “one of the good ones”.

In October 2024, Graham Norton was joined by Saoirse Ronan, Paul Mescal, Eddie Redmayne and Denzel Washington on his panel talk show. When discussing the concept of using a phone as a self-defence tool, Paul Mescal quipped, “Who’s actually going to think about that? If someone attacked me, I’m not going to go – phone.” Mescal humorously reached into his back pocket as the audience burst into laughter. The men added various comments until Saoirse Ronan cut through their voices, “That’s what girls have to think about all the time. Am I right ladies?” The audience quickly changed tone, cheering her for speaking up whilst the men nodded quietly.

This twenty-second exchange went viral. Publications from Vogue, The Guardian and the BBC all praised Ronan’s truthful outspokenness. However, many drew attention to the men on the show, in particular Paul Mescal. An often-characterised soft boi, Paul Mescal is known for his sensitivity, emotional depth and embracing of feminine traits. He later praised that Saoirse Ronan was “spot on” for calling out women’s safety. But it served as an important reminder that the societally termed ‘good bloke’ is not exempt from bad moments.

Australian philosopher Kate Manne shows us the worst consequences of the ‘golden boy’ trope. In Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, she introduces the term ‘himpathy’, used to describe excessive sympathy towards male perpetrators of sexual violence. She describes the reluctance to believe women who testify against established ‘golden boys’, citing the 2015 People v Turner case as her primary study. In 2015, Chanel Miller (formerly Emily Doe) accused Standford freshman Brock Turner of five counts of felony sexual assault. In this case, testimony from a female friend that Brock Turner was “caring, sweet and respectful to her” corroborated the Judge’s assessment of Turner’s character.

Manne reveals himpathy’s dangerous ethical implication: “Good guys aren’t rapists. Brock Turner is a good guy. Therefore, Brock Turner is not a rapist”. The case culminated in six months of jail time and three years of probation; however, Turner was released from jail after three months on good behaviour.

In the manosphere, ‘Nice Guy Syndrome’ has also been used to describe people who are nice with the aim of obtaining or maintaining a sexual relationship with another person. In this case, being ‘good’ is currency for an ulterior agenda where the person exhibiting ‘nice guy’ qualities builds a sense of entitlement that they are owed a romantic or sexual relationship. When the other person rejects them, the ‘nice guy’ can become disdainful or irrationally angry because they were not given what they are ‘owed’. Whilst the ‘good guy’ mold and ‘nice guy syndrome’ are inextricably linked, many individuals equate being good with being kind, when they are sometimes two very different things.

When engaging with an average well-intentioned man, the ethical implications are often nuanced. Dr Glenn R. Schiraldi outlines childhood adversity including neglect, abandonment or abuse as root causes of the insecurity that leads to being passive and overly dependent on others/women for approval. This can create the ‘good guy’ who would rather maintain a likeable façade than engage in conflict.

I’ve often sat with friends after hearing stories where a ‘good guy’ didn’t have the emotional maturity to initiate a hard conversation for fear of appearing unlikeable. And we always came back to the same questions. Having good intentions should not be disincentivised, but where does being good fall and being kind succeed? What does it mean to be kind?

The first time the difference between being good and being kind was articulated to me was in The Imperfects Podcast, where psychologist Dr Emily Musgrove framed it as choosing truth versus harmony. When we want to do the ‘good’ thing, we choose the option that will keep the relationship in harmony. However, in the long term, we don’t achieve harmony through continually sacrificing the hard truth over having a harmonious relationship. Sometimes, delivering a hard truth is kinder than maintaining short term harmony.

I was in my early twenties when I learnt that being kind meant you might have to let someone down. I was in my mid-twenties when I realised that a man being ‘good’ to me didn’t mean he was being ‘kind’ to me. This principle applies to everyone but is one that prevails amongst men that care more about having a ‘good guy’ reputation than leading with integrity.

The fizziness of my cider travels straight to my brain as my legs dangle over the concrete pavement. I giggle, laugh and tipsily dance until the early hours of the morning, meeting his friends for the first time. What no one had told me was how he would keep important secrets from me for fear of hurting my feelings, which would only hurt me more. How he would withdraw when he wasn’t happy with me and how I would respond in frustration, confused and demanding answers. How he would carry antiquated views that would never come to full light because after all, he was a good guy.

We need to eliminate the ‘good guy’ trope as a seal of approval. We need to end the binary that people are either good or bad and start operating on the foundation that everyone is a person with the potential to be good and bad in moments. Instead of being ‘nice’, we should strive to be authentic, truthful and kind, even in the moments where it doesn’t make us look good.

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind by Isha Desai is the winning essay in our Young Writers’ 2025 Competition (18-30 age category). Find out more about the competition here.

BY Isha Desai

Isha Desai is a writer, researcher and analyst, graduated from the University of Sydney in Politics and International Relations. She was the 2024 Indo Pacific Fellow for Young Australians in International Affairs (YAIA) and currently works in social impact policy at Penguin Random House ANZ.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe our friends

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ethics programs work in practise

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Values

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

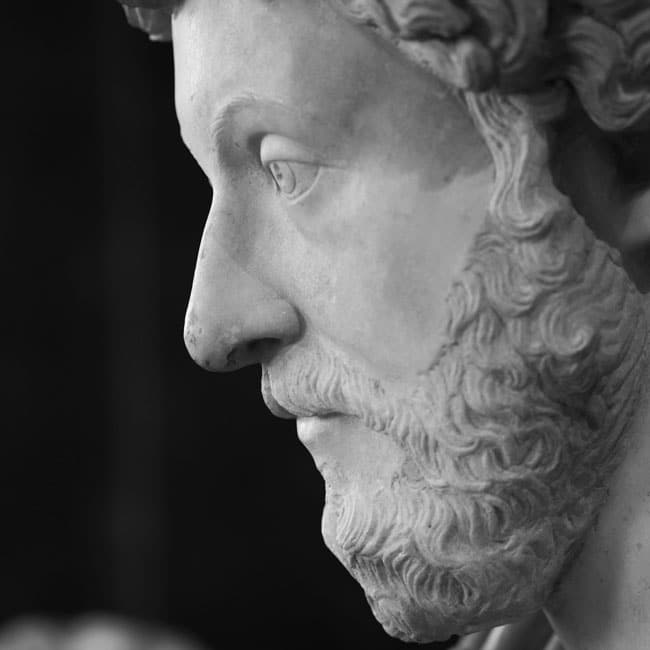

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Big thinkerSociety + CultureBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 7 OCT 2025

Ayn Rand (born Alissa Rosenbaum, 1905-1982) was a Russian-born American writer & philosopher best known for her work on Objectivism, a philosophy she called “the virtue of selfishness”.

From a young age, Rand proved to be gifted, and after teaching herself to read at age 6, she decided she wanted to be a fiction writer by age 9.

During her teenage years, she witnessed both the Kerensky Revolution in February of 1917, which saw Tsar Nicholas II removed from power, and the Bolshevik Revolution in October of 1917. The victory of the Communist party brought the confiscation of her father’s pharmacy, driving her family to near starvation and away from their home. These experiences likely laid the groundwork for her contempt for the idea of the collective good.

In 1924, Rand graduated from the University of Petrograd, studying history, literature and philosophy. She was approved for a visa to visit family in the US, and she decided to stay and pursue a career in play and fiction writing, using it as a medium to express her philosophical beliefs.

Objectivism

“My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.” – Appendix of Atlas Shrugged

Rand developed her core philosophical idea of Objectivism, which maintains that there is no greater moral goal than achieving one’s happiness. To achieve this happiness, however, we are required to be rational and logical about the facts of reality, including the facts about our human nature and needs.

Objectivism has four pillars:

- Objective reality – there is a world that exists independent of how we each perceive it

- Direct realism – the only way we can make sense of this objective world is through logic and rationality

- Ethical egoism – an action is morally right if it promotes our own self-interest (rejecting the altruistic beliefs that we should act in the interest of other people)

- Capitalism – a political system that respects the individual rights and interests of the individual person, rather than a collective.

Given her beliefs on individualism and the morality of selfishness, Rand found that the only political system that was compatible was Laissez-Faire Capitalism. Protecting individual freedom with as little regulation and government interference would ensure that people can be rationally selfish.

A person subscribing to Objectivism will make decisions based on what is rational to them, not out of obligation to friends or family or their community. Rand believes that these people end up contributing more to the world around them, because they are more creative, learned, and can challenge the status quo.

Writing

She explored these concepts in her most well-known pieces of fiction: The Fountainhead, published in 1943, and Atlas Shrugged, published in 1957. The Fountainhead follows Howard Roark, an anti-establishment architect who refuses to conform to traditional styles and popular taste. She introduces the reader to the concept of “second-handedness”, which she defines living through others’ and their ideas, rather than through independent thought and reason.

The character Roark personifies Rand’s Objectivist ideals, of rational independence, productivity and integrity. Her magnum opus, Atlas Shrugged, builds on these ideas of rational, selfish, creative individuals as the “prime movers” of a society. Set in a dystopian America, where productivity, creativity, and entrepreneurship stagnate due to over-regulation and an “overly altruistic society”, the novel describes this as disincentivising ambitious, money-driven people.

Even though Atlas Shrugged quickly became a bestseller, its reception was controversial. It has tended to be applauded by conservatives, while dismissed as “silly,’ “rambling” and “philosophically flawed” by liberals.

Controversy

Ayn Rand remains a controversial figure, given her pro-capitalist, individual-centred definition of an ideal society. So much of how we understand ethics is around what we can do for other people and the societies we live in, using various frameworks to understand how we can maximise positive outcomes, or discern the best action. Objectivism turns this on its head, claiming that the best thing we can do for ourselves and the world is act within our own rational self-interest.

“Why do they always teach us that it’s easy and evil to do what we want and that we need discipline to restrain ourselves? It’s the hardest thing in the world–to do what we want. And it takes the greatest kind of courage. I mean, what we really want.”

Rand’s work remains hotly debated and contested, although today it is being read in a vastly different context. Tech billionaires and CEOs such as Peter Thiel and Steve Jobs are said to have used her philosophy as their “guiding stars,” and her work tends to gain traction during times of political and economic instability, such as during the 2008 financial crisis. Ultimately, whether embraced as inspiration or rejected as ideology, Rand’s legacy continues to grapple with the extent to which individual freedom drives a society forward.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

The business who cried ‘woke’: The ethics of corporate moral grandstanding

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

No justice, no peace in healing Trump’s America

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Things you might like to know about the rich

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 23 SEP 2025

When I facilitate a Circle of Chairs conversation at The Ethics Centre, I always pause before starting and remind myself that I’m about to enter a potentially dangerous space. There are few domains that are as hotly contested and emotionally charged as ethics.

In this space, people might have their deepest values questioned, their most cherished views challenged, and they are likely to encounter people who hold radically different moral and political beliefs to their own.

Yet, after stepping into many Circles, I can’t think of a single time when I haven’t stepped out having witnessed a rich, deep and often challenging conversation that has left everyone feeling closer together as humans, even if they remain far apart in their views.

This is because we don’t just encourage any kind of speech in a Circle of Chairs. We do acknowledge the importance of free speech, not least because it’s our best means of challenging conventional wisdom, correcting errors and seeking the truth. But we also recognise that just protecting free speech sets a perilously low bar for the quality of discourse.

Now seems like a good time to talk about how we talk to each other. Especially so in the wake of conservative commentator, Charlie Kirk’s, assassination in the United States. That horrific event, coupled with two late night talk show hosts being taken off air in recent months, ostensibly due to comments made that have offended the Trump administration and its ideological allies, has sparked numerous conversations about the nature of good faith debate and the limits of free speech.

But if we just limit ourselves to removing speech that is directly harmful, hateful or incites violence, it still leaves a lot of room for speech that can be deceptive, offensive, divisive and dehumanising. Which is why at The Ethics Centre, we treat free speech as a baseline and add other norms on top that serve to promote constructive discourse.

These norms enable people to engage with views that are vastly different to their own – including arguing for their own perspectives and challenging those they believe are wrong – without things slipping into vitriol or worse.

I wonder if these norms might be useful when it comes to think about how we ought to speak to each other. And I stress: these are norms, not laws. They are expectations around how to behave. They’re not intended to be used to silence or punish those who fail to conform to them. They are offered as a guide for those who want to break out of the cycles of polarising and vilifying speech that we see all too often today.

Respect

The first norm is in some ways the simplest, but also the most important: respect. It states that we should always recognise others’ inherent humanity, no matter how obtuse or perverse their beliefs.

What this means is that we might choose not to say something if we think doing so will disrespect or injure their dignity as a person. We already do this in many domains of our lives. If someone has just lost a loved one, we might refrain from criticising the deceased, even if we have a genuine grievance. Likewise, we might choose not to say something we believe is true if it might dehumanise or objectify someone. As they say, “honesty without compassion is cruelty”.

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strongly challenge others’ beliefs, especially if we feel they are false or harmful. Sometimes, we should do so even if it might offend them. But there’s a pragmatic element: without mutual respect, our challenges will likely fall on deaf ears, triggering defensiveness rather than encouraging openness.

Showing respect to someone you disagree with is a powerful tool to build the kind of trust that is necessary to have them actually listen to what you have to say. And the more trust and respect you build, the less chance you have of being seen to be disrespectful, and the more frank you can afford to be when you speak.

Good faith

The second norm is to always speak in good faith. This has two elements. The first is that we speak with good intention, with the aim to understand, find the truth and make the world a better place, rather than speaking to intimidate, self-aggrandise or hide an insecurity. The second element is that we speak with intellectual honesty, acknowledging our fallibility and being open to the possibility of being wrong.

We all know it’s all too easy to slip into bad faith, especially when emotions run high or we feel threatened. We might utter a barbed comment, or defend a position we don’t really understand, or we dig in our heels so we don’t look dumb. We also know what it’s like to encounter bad faith, like when you dismantle someone’s argument only to discover they haven’t changed their mind. It’s infuriating, and it can rapidly devolve a conversation into mutual bad faith attacks. You know, like what we see on social media.

Charity

The third norm is charity, which is just the flip side of good faith. Charity means we assume good faith on behalf of the person we’re speaking to rather than assuming the worst about them and their beliefs. It means filling in the blanks with the best possible version of their argument instead of jumping to attack the weakest possible version.

Charity also means giving people an on-ramp back to good faith if we do discover they are speaking in bad faith. Rather than writing them off, we try to show respect and find some mote of common ground – a shared value or belief – and build on that until we can better understand where we diverge, and talk about that.

These norms don’t guarantee all speech will be constructive. They’re not always easy to implement – especially in the unregulated wilderness of social media. But see them as being more aspirational, a kind of soft expectation that we place on ourselves and hope to demonstrate to others through the way we speak.

When we’re mindful of them, they can change conversations. I’ve seen it happen many times. I’ve seen political opponents really listen to each other and acknowledge that the other has a point. I’ve seen a climate denier and an environmental activist hug after a long conversation. I’ve seen an anti-vaxxer thank a science journalist for disagreeing without calling them names. It won’t always go like that. But in a world where we’re thrust into proximity with those we disagree with, where the threat of political violence will always hover in the wings, ready to take the stage when speech fails, I’m convinced these three norms can make a difference.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

‘The Zone of Interest’ and the lengths we’ll go to ignore evil

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A note on Anti-Semitism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

What happens when the progressive idea of cultural ‘safety’ turns on itself?

What happens when the progressive idea of cultural ‘safety’ turns on itself?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Hugh Breakey 4 SEP 2025

In mid-August, controversy enveloped the Bendigo Writers Festival. Just days before it began, festival organisers sent a code of conduct to its speakers – a code that drove more than 50 authors to make the difficult decision to pull out.

The code was intended to ensure the event’s safety, with a requirement to “avoid language or topics that could be considered inflammatory, divisive, or disrespectful”. Yet distressed speakers argued it made them feel culturally unsafe. Speakers on panels presented by La Trobe university were also required to employ a contested definition of antisemitism.

The incident is the most recent in a series of controversies in which progressive writers and artists have faced restrictions and cancellations, with organisations citing “safety” as the reason. They include libraries cancelling invited speakers and asking writers to avoid discussing Gaza, Palestine and Israel.

How did speech rules developed and promoted by the progressive left – rules promoting cultural safety and safe spaces – become tools that could be wielded against it?

Applying ‘safety’ to speech

Over recent years, “safety” – including in terms like “safe spaces” and “cultural safety” – has become a commonly raised ethical concern. Safe-speech norms often arise in the context of public deliberation, education and political speech.

“Safe spaces” are places where marginalised groups are protected against harassment, oppression and discrimination, including through speech like microaggressions, unthinking stereotypes and misgendering. Within safe spaces, protected groups are encouraged and empowered to speak about their experiences and needs.

Similarly, “cultural safety” refers to environments where there is no challenge or denial of people’s identities, allowing them to be genuinely heard. This can be crucial for First Nations communities, especially in health and legal contexts.

Safe-speech norms are therefore complex. They involve the freedom to speak, but also freedom from speech.

This way of thinking takes a broad view of the kinds of speech that can be interpreted as harmful or violent. Harmful speech does not just include hate speech and incitement. It also includes speech with unintended consequences and speech that challenges a person’s perceived identity.

These safe-speech norms, increasingly adopted in universities and other broadly progressive organisations, should be distinguished from “psychological safety”. This earlier concept refers to creating environments – such as workplaces – where it is safe to speak up, including to raise concerns or ask questions.

While psychological safety is a general norm protecting all parties, the more recent safe-speech norms protect specific marginalised groups. They aim to push back against larger systemic forces like racism or misogyny that would otherwise render those groups oppressed or unsafe. In some cases, the prioritisation of safety has led to deplatforming of speakers at universities.

With this special focus on oppressed minorities and heightened sensitivity to speech’s negative impacts, applying these norms has become a familiar part of progressive social justice efforts (sometimes pejoratively called “wokism”). Now, conservatives and others are employing the language of cultural safety to close down discussion of topics such as the war in Gaza.

Are safe-speech norms controversial?

By constraining what can be said, safe speech norms impinge on other potentially relevant ethical norms, such as those of public deliberation. These “town square” norms aim to encourage a diversity of views and allow space for a robust dialogue between different perspectives.

Public deliberation norms might be defended as part of the human right to free speech, or because arguing and deliberating with other people can be an important way of respecting them.

Alternatively, public deliberation can be defended by appeal to democracy, which requires more than merely casting votes. Citizens must be able to hear and voice different perspectives and arguments.

Those in favour of free speech and the public square will look suspiciously at safe-speech norms, worrying that they give rise to the well known risks of political censorship. Thinkers like Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff explicitly criticise “safetyism”, arguing the prioritisation of emotional safety inappropriately coddles young people.

Supporters of safe-speech norms might respond in different ways to these objections. One response might be that safety doesn’t intrude very much on dialogue anyway (at least, not on the type of dialogue worth having). Another response might be to challenge the value of public debate itself, seeing any system that does not explicitly work to support the marginalised as inherently oppressive.

Yet another response might be to query whether writers festivals are an apt place for public debate. Most speakers want an enjoyable experience and to promote their book (even when such books explore contentious ideas). Many in the audience will be supportive of the authors’ ideas and positions. Some will even be fans. Maybe it’s not so bad if most festival sessions are “love-ins”.

Prohibited vs. protected

In order to protect and empower specific marginalised groups, safe-speech norms both support and restrain speech. So long as the views of these protected groups are relatively aligned with each other, these norms work coherently. The speech that is being prohibited doesn’t overlap with the speech that is being protected.

But what happens when members of two marginalised groups have stridently opposed views and the words they use to decry injustice are called unsafe by their opponents? Once this happens, the speech that one group needs to be protected is the same speech that the other group needs prohibited.

Perhaps it was inevitable that the internal contradictions of safe-speech norms would eventually create such problems. In Australia, like many countries, this was triggered by the October 7 Hamas atrocity and Israel’s unrelenting and brutal military response. Jews and Palestinians are both vulnerable minorities who face the well known bigotries of antisemitism and Islamophobia respectively. They both can reasonably demand the protection of safe-speech norms.

However, is each side interested in respecting the other’s right to such norms? Author and academic Randa Abdel-Fattah has reportedly alleged on social media, that if you are a Zionist, “you have no claim or right to cultural safety”. In turn, she says she has been harrassed and threatened over her views on the war in Gaza, and public institutions hosting her “have been targeted with letters defaming me and demanding I be disinvited”.

Perhaps the time has come to acknowledge that safe speech norms were never as straightforward or innocuous as they first appeared. They require a form of censorship that not only involves choosing political sides, but inevitably making fine-grained judgements between which opposing minority deserves protection at the expense of the other.

Indeed, safe speech norms may themselves be exclusionary. The US organisation “Third Way” advocates for moderation and centre left policies. In a recent memo it said research among focus groups had consistently found ordinary people interpreted key terms from progressive political language as alienating and arrogant.

According to Third Way, the term “safe space” (among others) communicates the sense that, “I’m more empathetic than you, and you are callous to hurting others’ feelings.”

With all this in mind, I find it hard to disagree with author Waleed Aly’s recent reflection that “in arenas dedicated to public debate, safety makes a poor organising principle”. Efforts to support and include marginalised voices are laudable. However, safe-speech norms are a deeply problematic – and perhaps ultimately contradictory – tool to use in pursuing that worthy goal.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

BY Hugh Breakey

Hugh is Deputy Director at Griffith University’s Institute for Ethics, Governance and Law. His research spans the philosophical subdisciplines of political philosophy, normative ethics, moral psychology, governance studies and applied philosophy. His works explore the ethical challenges arising in such diverse fields as peacekeeping, institutional governance, climate change, sustainable tourism, safety industries, private property, medicine, and international law, published in journals including The Philosophical Quarterly, The Modern Law Review and Political Studies. He has taught philosophy and ethics at the University of Queensland, Queensland University of Technology and Bond University. Since 2013, Hugh has served as President of the Australian Association for Professional and Applied Ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia Day and #changethedate – a tale of two truths

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture