Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

ExplainerRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 28 JUL 2020

Have you ever seen a situation that seems flatly wrong, but when asked to explain why you find yourself struggling for words? Perhaps you’ve got a strong sense that something is wrong – an immediate, powerful instinct about what should or shouldn’t happen. In ethics, we refer to these as moral intuitions.

Moral intuitions go by a number of different names. Some of us talk about ‘gut instinct’ or whether something passes the ‘sniff test’. Both terms suggest that there is some strong, basic belief about right and wrong that we can use to ground our judgements.

The problem is, despite the speed and strength of these intuitions, they are only as valuable as their source. Our intuitions can come from a range of sources: personal and family history, unconscious biases, custom, culture or a strong, stable and well-founded sense of what’s right.

Opinions differ on what we should do with our moral intuitions. Should we follow them, trusting them as a different kind of knowledge that draws on subconscious, non-rational and emotional cues? Should we ignore them, seeing them as irrational, unjustifiable claims about what’s right or wrong? Or should we treat them as one piece of evidence among many when we’re making a decision?

Resolving these questions requires us to work out what kind of intuitions we’re having. Some of our judgements about ethics can be based in a sense of disgust or ideas about what’s taboo (for instance, thinking about lab-grown meat), they can be the product of psychological biases like availability bias or halo effect, or social prejudices like racism, sexism, ableism or class-based moralities.

However, other intuitions may be based in our emotional response to a situation. Many of our emotions can reflect and inform our rational judgements. If something makes us angry, that’s information worthy of considering. If something makes us proud, that’s data we can use to help shape an opinion. Standing alone, ‘this made me feel sick’ isn’t sufficient information to form a moral judgement. But, the fact that learning about or witnessing something made you feel physically ill also isn’t something you should ignore lightly.

From the Nazis to ISIS, history is littered with groups who have encouraged their members to dismiss the evidence of their minds and bodies – such as feeling of disgust or shame at committing acts of murder – in order to serve some ‘higher’ goal. Dismissing the morally informative role of emotions can be used as a tool to pave the way to atrocity.

Whilst emotions alone should not be taken as sufficient for forming judgement, some believe there are kinds of intuitions that can, in and of themselves, reveal something ethically important to us.

For instance, we might have an intuition that all people are to be treated fairly, that it is wrong to intentionally harm an innocent person for no reason or that all people are to be treated with dignity. These are beliefs that moral intuitionists claim to be self-evident. These ideas don’t need to be justified or proven true, they just are. A moral intuitionist would argue that any person who disputes them is simply wrong.

Of course, not everyone accepts that there are self-evident principles on which to build an ethical system. These people, who are often associated with a philosophical school of thought known as rationalism, prioritise analytic reason, and hold that intuitions should be ignored. The only basis on which we should make ethical judgements is a rationally constructed argument. If, for instance, we think all people should be treated equally, we should make an argument to that effect. If we can’t, we don’t have good reasons to hold that belief.

What intuitionists and rationalists agree on is that making an ethical judgement is distinct from having a moral intuition. Our strong, immediate judgements about a situation are rarely – if ever – enough for us to make a decent appraisal of a situation.

However, the rationalist goal of eliminating emotion and intuition from the realm of ethical judgement is also false. Critical feminist and race scholars have highlighted the way that rationalists tend to paint a male, Western approach to thinking as a ‘universal’ rationality. In doing so, they tend to understate and invalidate other knowledge traditions and sources of moral judgement, including emotion.

For example, psychologist Laurence Kohlberg used a rationalist model of ethical decision-making to develop a stage theory of moral development. He thought rational, theoretical decision-making was more mature than decisions based on emotion, care and relationships. As a result, he concluded that boys tended to be more morally mature than their same-age female peers.

It took his student, feminist scholar Carol Gilligan, to point out that not only was Kohlberg’s assumption about rationality unjustified (it ignored, for example, the work of scholars like David Hume), it painted the difference between male and female moral reasoning as a deficiency in women rather than as a simple difference.

Perhaps we should take guidance from both rationalists and intuitionists. From the rationalist we can learn the understanding that our first judgement of a situation should not be our last. However, intuitionists remind us not to dismiss our initial judgements out of hand, but to interrogate and understand them. That way, next time, our intuitions will be a little closer to the mark.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

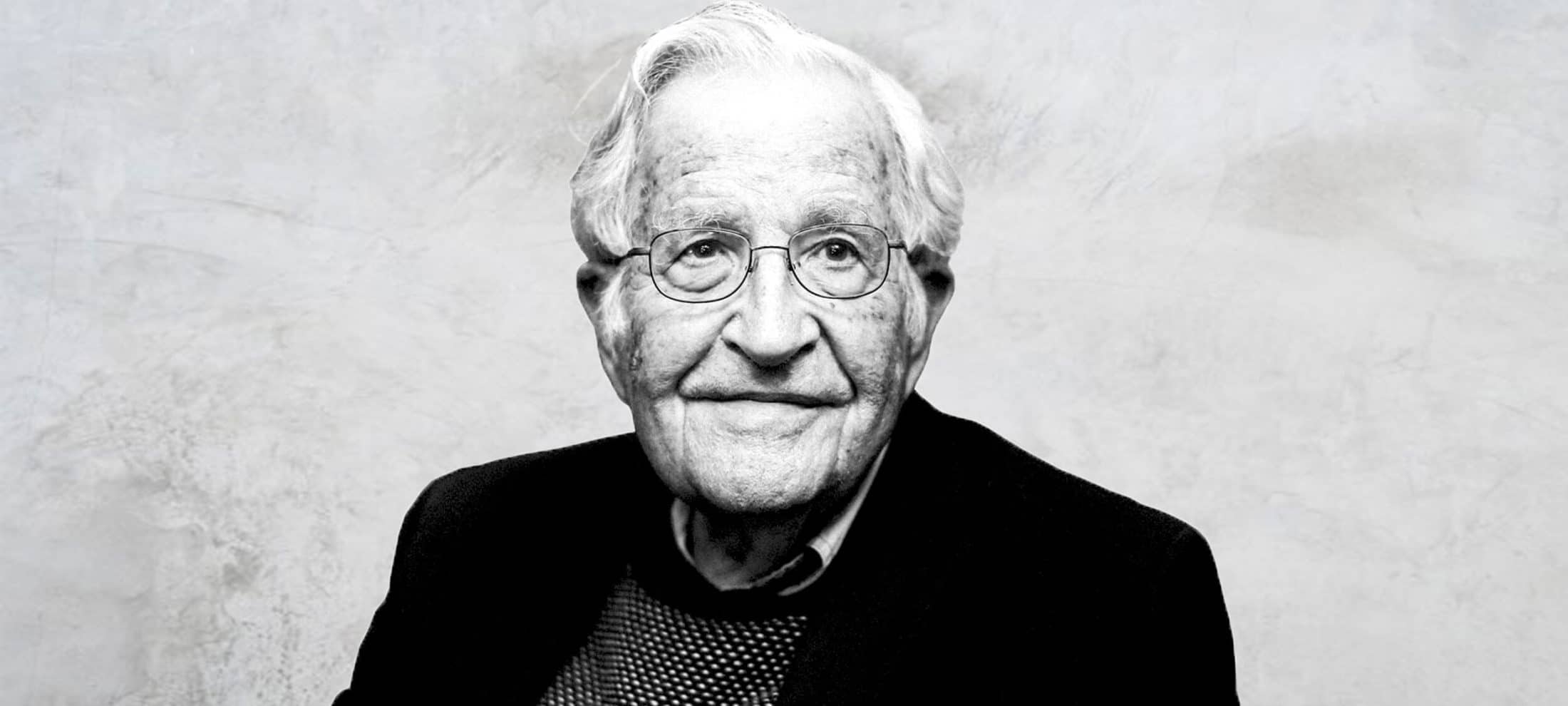

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Agape

How many people do you think we can love? Can we love everyone? Can we love everyone equally? The answers to these questions obviously depend on what the nature of this kind of love is, and what it looks like or demands of us in practice.

“Love is all you need”

Agape is a form of love that is commonly referred to as ‘neighbourly love’, the love ethic, or sometimes ‘universal love’. It rests on the idea that all people are our ‘brothers and sisters’ who deserve our care and respect. Agape invites us to actively consider and act upon the interests of other people, in more-or-less the same proportion as you consider (and usually act upon) your own interests.

We can trace the concept back to Ancient Greece, a time in which they had more than one word to describe various kinds of love. Commonly, useful distinctions can be made between eros, philia, and agape.

Eros is the kind of love we most often associate with romantic partners, particularly in the early stages of a love affair. It’s the source of English words like ‘erotic’ and ‘erotica’.

Philia generally refers to the affection felt between friends or family members. It is non-sexual in nature and usually reciprocal. It is characterised by a mutual good will that manifests in friendship.

Although both eros and philia have others as their focus, they can both entail a kind of self-interest or self-gratification (after all, in an ideal world our friends and lovers both give us pleasure).

Agape is often contrasted to these kinds of love because it lacks self-interest, self-gratification or self-preservation. It is motivated by the interest and welfare of all others. It is global and compassionate, rather than focussed on a single individual or a few people.

Another significant difference between agape and other forms of love is that we choose and cultivate agape. It’s not something that ‘happens’ to us like becoming a friend or falling romantically in love, it’s something we work toward. It is often considered praiseworthy and holds the lover to a high moral standard.

Agape is a form of love that values each person regardless of their individual characteristics or behaviour. In this way it is usually contrasted to eros or philia, where we usually value and like a person because of their characteristics.

Agape in traditional texts

The concept of agape we now have has been strongly influenced by the Christian tradition. It symbolises the love God has for people, and the love we (should) have for God in return. By extension, if we love our ‘neighbours’ (others) as we do God, then we should also love everyone else in a universal and unconditional manner, simply because they are created in the likeness of God.

The Jesus narrative asks followers to act with love (agape) regardless of how they feel. This early Christian ethical tradition encourages us to “love thy neighbour as thyself”. In the Buddhist tradition K’ung Fu-tzu (Confucius) similarly says, “Work for the good of others as you would work for your own good.”

Another great exponent of this ethic of love is Mahatma Gandhi who lived, worked, and died to keep this transcendent idea of universal love alive. Gandhi was known for saying, “Hate the sin, love the sinner”.

Advocates for non-violent resistance and pacifism that include Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and John Lennon and Yoko Ono also refer to the power of love as a unifying force that can overcome hate and remind us of our common humanity, regardless of our individual differences.

Such ideology rests on principles that are resonant with agape, urging us to love all people and forgive them for whatever wrongs we believe they have committed. In this way, agape sets a very high moral standard for us to follow.

However, this idea of generalised, unconditional love leaves us with an important and challenging question: is it possible for human beings to achieve? And if so, how far may it extend? Can we really love the whole of humanity?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

5 ethical life hacks

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

WATCH

Relationships

What is the difference between ethics, morality and the law?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

Ethics of care is a feminist approach to ethics. It challenges traditional moral theories as male-centric and problematic to the extent they omit or downplay values and virtues usually culturally associated with women or with roles that are often cast as ‘feminine’.

The best example of this may be seen in how ethics of care differs from two dominant normative moral theories of the 18th and 19th century. The first is deontology, best associated with Immanuel Kant’s ethics. The second is consequentialism, best associated with Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism and improved upon by John Stuart Mill.

Each of these moral theories require or encourage the moral agent to be unemotional. Moral decision-making is expected to be rational and logical, with a focus on universal, objective rules. In contrast, ethics of care defends some emotions, such as care or compassion, as moral.

On this view, there isn’t a dichotomy between reason and the emotions, as some emotions can be reasonable, morally appropriate or even helpful in guiding good decisions or actions. Feminist ethics also recognises that rules must be applied in a context, and real life moral decision-making is influenced by the relationships we have with those around us.

Instead of asking the moral decision-maker to be unbiased, the caring moral agent will consider that one’s duty may be greater to those they have particular bonds with, or to others who are powerless rather than powerful.

In a Different Voice

Traditional proponents of feminist care ethics include 20th century theorists Carol Gilligan and Nel Noddings. Gilligan’s influential 1982 book, In a Different Voice, claimed that Sigmund Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis and Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of moral development were biased and male-oriented.

On these dominant psychological accounts of human development, male development is taken as standard, and female development is often judged as inferior in various ways.

Gilligan argued if women are ‘more emotional’ than men, and pay more attention to relationships rather than rules, this is not a sign of them being less ethical, but, rather, of different values that are equally valuable. While Gilligan may have deemed these differences to be ‘natural’ and associated with sex rather than gender, these differences may well have been socially constructed and therefore the result of upbringing.

How might the ethics of care theorist resolve the classical ‘Heinz’ dilemma: Should a moral agent steal the required medicine he cannot afford to buy to give to his very sick wife, or stick to the rule ‘do not steal’, regardless of the circumstances? A tricky dilemma, to be sure, as there are competing duties here (namely, a positive duty to help those in need as well as a negative duty to avoid stealing).

Arguably, the caring person would place the relationship with one’s spouse above any relationship they may or may not have with the pharmacist, and care or compassion or love would outweigh a rule (or a law) in this case, leading to the conclusion that the right thing to do is to steal the medicine.

It’s worth noting that a utilitarian might also claim a moral agent should steal the medicine because saving the wife’s life is a better outcome than whatever negative consequences may result from stealing. However, the reasoning that leads to this conclusion is based on unemotional weighing of costs and benefits, rather than a consideration of the relationships involved and asking what love might demand.

Writing at the same time as Gilligan, Noddings also defended care as a particular form of moral relationship. She asserted that caring was “ethically basic” to humans and that it can be seen in children’s behaviour. While Noddings does not rule men out from being caring, it is usually women who feature in her examples of caregivers.

Noddings, like Gilligan, prioritises relationships that are between specific individuals in a particular context as the basis for ethical behaviour. This stands in contrast to the idea that morality involves following universal, abstract or purely logical moral rules.

Who cares?

Ethics of care has been influential in areas like education, counselling, nursing and medicine. Yet there have also been feminist criticisms. Some worry that it maintains a sexist stereotype and encourages or assumes women nurture others, even while society fails to value carers as they should.

Noddings and Gilligan both argue against this, saying that the capacity for care is a general human strength, and while it is empowering to acknowledge it as a positive capacity in women, it should be encouraged regardless of gender.

Join us for a timely conversation on the unseen perspectives, ethical dilemmas, and shifting cultural expectations around care – one of the most fundamental aspects of being human. The Ethics of Care is live and online on Thursday 28 August 2025 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Corporate whistleblowing: Balancing moral courage with moral responsibility

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Steven Pinker

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

Ethics Explainer: Plato's Cave

Plato’s allegory of the cave is a classical philosophical thought experiment designed to probe our intuitions about epistemology – the study of knowledge.

This story offers the reader an insight into one of Plato’s central concepts, namely, that eternal and unchanging ideas exist in an intellectual realm which we can only access through pure Reason.

Western philosophy may be traced back to Ancient Greece. We have a record of Socrates’ (469-399 BCE) oral teachings through the writings of his student, Plato (427-347 BCE). In these Socratic Dialogues, Socrates argues with his interlocutors in an effort to seek truth, meaning, and knowledge. Plato’s Republic is the best known of these and, in book VII, Socrates presents Glaucon (Plato’s older brother) with an unusual image:

Imagine a number of people living in an underground cave, which has an entrance that opens towards the daylight. The people have been in this dwelling since childhood, shackled by the legs and neck, such that they cannot move nor turn their heads to look around. There is a fire behind them, and between these prisoners and the fire, there is a low wall.

Rather like a shadow puppet play, objects are carried before the fire, from behind the low wall, casting shadows on the wall of the cave for the prisoners to see. Those carrying the objects may be talking, or making noises, or they may be silent. What might the prisoners make of these shadows, of the noises, when they can never turn their heads to see the objects or what is behind them?

Socrates and Glaucon agree that the prisoners would believe the shadows are making the sounds they hear. They imagine the prisoners playing games that include naming and identifying the shadows as objects – such as a book, for instance – when its corresponding shadow flickers against the cave wall. But the only experience of a ‘book’ that these people have is its shadow.

After suggesting that these prisoners are much like us – like all human beings – the narrative continues. Socrates tells of one prisoner being unshackled and released, turning to see the low wall, the objects that cast the shadows, the source of the noises as well as the fire.

While the prisoner’s eyes would take some time to adjust, it is imagined that they now feel they have a better understanding of what was causing the shadows, the noises, and they may feel superior to the other prisoners.

This first stage of freedom is further enhanced as the former prisoner leaves the cave (they must be forced, as they do not wish to leave that which they know), initially painfully blinded by the bright light of the sun.

The liberated one stumbles around, looking firstly only at reflections of things, such as in the water, then at the flowers and trees themselves, and, eventually, at the sun. They would feel as though they now have an even better understanding of the world.

Yet, if this same person returned to the dimly lit cave, they would struggle to see what they previously took for granted as all that existed. They may no longer be any good at the game of guessing what the shadows were – because they are only pale imitations of actual objects in the world.

The other prisoners may pity them, thinking they have lost rather than gained knowledge. If this free individual tried to tell the other prisoners of what they had seen, would they be believed? Could they ever return to be like the others?

The remaining prisoners certainly would not wish to be like the individual who returned, suddenly not knowing anything about the shadows on the cave wall!

Socrates concludes that the prisoners would surely try to kill one who tried to release them, forcing them into the painful, glaring sun, talking of such things that had never been seen or experienced by those in the cave.

Interpreting the Allegory of the Cave

There are multiple readings of this allegory. The text demonstrates that the Idea of the Good (Plato capitalises these concepts in order to elevate their significance and refer to the idea in itself rather than any one particular instantiation of that concept), which we are all seeking, is only grasped with much effort.

Our initial experience is only of the good as reflected in an earthly, embodied manner. It is only by reflecting on these instantiations of what we see to be good, that we can start to consider what may be good in itself. The closest we can come to truly understanding such Forms (the name he gives these concepts), is through our intellect.

Human beings are aiming at the Good, which Medieval philosophers and theologians equated with God, but working out what the good life consists of is not easy! Plato claims each Soul (or mind) chooses what is good, saying:

“But, whether true or false, my opinion is that in the world of knowledge the idea of good appears last of all, and is seen only with an effort.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Appreciation or appropriation? The impacts of stealing culture

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How should I divvy up my estate in my will?

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

Ethics Explainer: Aesthetics

Aesthetics is the philosophical study of art. If you think about what is enjoyable, or valuable about artworks, and why art is important, then you are considering issues to do with aesthetics.

The study of aesthetics is tricky because there are so many different kinds of artworks and it is difficult to think about what they have in common or how they should be categorised or judged. A seminal question in the field of aesthetics is ‘what is art?’ – how ought art be defined? And this question alone has various answers depending on which theory is being applied.

Art defined.

Art includes sculpture, painting, plays, films, novels, dance and music. And it isn’t always clear what the category of art excludes – in large part because artists are always pushing boundaries. The creative nature of art sees works or objects being considered as ‘Art’ that provoke shock, outrage, censorship or exclamations of ‘That’s not Art!’.

Just think about the first time Marcel Duchamp tried to display an artwork called ‘Fountain’ in 1917. The urinal, a ‘found object’ was signed by the artist ‘R. Mutt, 1917’, and caused a riot of disagreement as to whether art must be created or made with one’s own hands or whether it can be intentionally chosen and displayed.

Is it the creation or the reception of the artwork that matters the most?

Who decides whether something is a work of art? Is it ‘the artworld’ of experts and critics? Is it the artist? Or is it the viewer? Many viewers may not understand what they are seeing or may not truly appreciate the skill involved in creating a particular artwork.

For instance, the first time one looks at a Rothko painting, which may appear as a blank canvas painted with a couple of coloured squares, a viewer may think, ‘I could have painted that!’ It is only with an understanding of Rothko’s technique that one may start to appreciate the effort he put in to create it.

And even if we appreciate the skill and effort an artist exerts, we may or may not feel any particular ‘aesthetic experience’ when looking at a piece of abstract or contemporary art, while watching an opera, or while reading a novel by Dostoevsky.

An individual perspective

One’s experience of art is subjective as individual tastes differ. And yet, if we are to claim that some artworks are better than others, or explain why some artworks stand the test of time and are valued by generations, we need to refer to some standards by which to judge them. Are there any features artworks must have to be considered as art? Should artworks be beautiful? Do they need to be moral? And who decides whether or not they meet this criteria?

Despite the historical interference by political and religious leaders who worry about the influence art may have in a society, debates as to what constitutes good art, aesthetically and even morally, has been a matter for debate for aestheticians.

Sometimes it takes time for something to be considered art, let alone to be considered aesthetically valuable. Think about Banksy’s graffiti art. It has been the case that unsuspecting council workers have removed graffiti from the side of a building only to later discover they have inadvertently eliminated a valuable artwork. And yet, not all graffiti is considered art or deemed valuable.

In fact, the opposite is true!

What makes Banksy an exception?

View this post on Instagram. "The urge to destroy is also a creative urge" – Picasso

A post shared by Banksy (@banksy) on

Definitions of art have changed over time. Traditional views of art usually cited ‘beauty’ as an important feature of artworks, but that has since altered. Indeed, is one meant to find the displayed urinal ‘beautiful’? An artwork need not be beautiful to be skilfully executed, meaningful and valuable.

The value of art in society

The defenders of art and its unique role in society usually claim art should be valued for its own sake. Aesthetic value is not to be valued instrumentally, for its financial value or for its status, or even for what we can learn from it or because it is deemed morally ‘good’. It may do any and/or all of these things, or none! Art is valuable because it affords an aesthetic experience.

In its creation and reception, as a form of self expression, imaginative engagement, cognitive as well as affective experience, source of individual and social reflection and contemplation, art has always been central to human life. If it is true that the arts capture and express something unique, and aesthetic experience is intrinsically valuable, then we should consider the place for the arts in society and support and value artists for the important contribution they make.

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is a senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Ethics in engineering makes good foundations

ArticleBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Has passivity contributed to the rise of corrupt lawyers?

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY ethics

Ethics Explainer: Existentialism

If you’ve ever pondered the meaning of existence or questioned your purpose in life, you’ve partaken in existentialist philosophy.

It would be hard to find someone who hasn’t asked themselves the big questions. What is the meaning of life? What is my purpose? Why do I exist? For thousands of years, these questions were happily answered by the belief your purpose in life was assigned prior to your creation. The existentialists, however, disagreed.

Existentialism is the philosophical belief we are each responsible for creating purpose or meaning in our own lives. Our individual purpose and meaning is not given to us by Gods, governments, teachers or other authorities.

In order to fully understand the thinking that underpins existentialism, we must first explore the idea it contradicts – essentialism.

Essentialism

Essentialism was founded by the Greek philosopher Aristotle who posited everything had an essence, including us. An essence is “a certain set of core properties that are necessary, or essential for a thing to be what it is”. A book’s essence, for example, is its pages. It could have pictures or words or be blank, be paperback or hardcover, tell a fictional story or provide factual information. Without pages though, it would cease to be a book. Aristotle claimed essence was created prior to existence. For people, this means we’re born with a predetermined purpose.

This idea seems to imply, whether you’re aware of it or not, that your purpose in life has been determined prior to your birth. And as you live your life, the decisions you make on a daily basis are contributing to your ultimate purpose, whatever that happens to be.

This was an immensely popular belief for thousands of years and gave considerable weight to religious thought that placed emphasis on an omnipotent God who created each being with a predetermined plan in mind.

If you agreed with this thinking, then you really didn’t have to challenge the meaning of life or search for your purpose. Your God already provided it for you.

Existence precedes essence

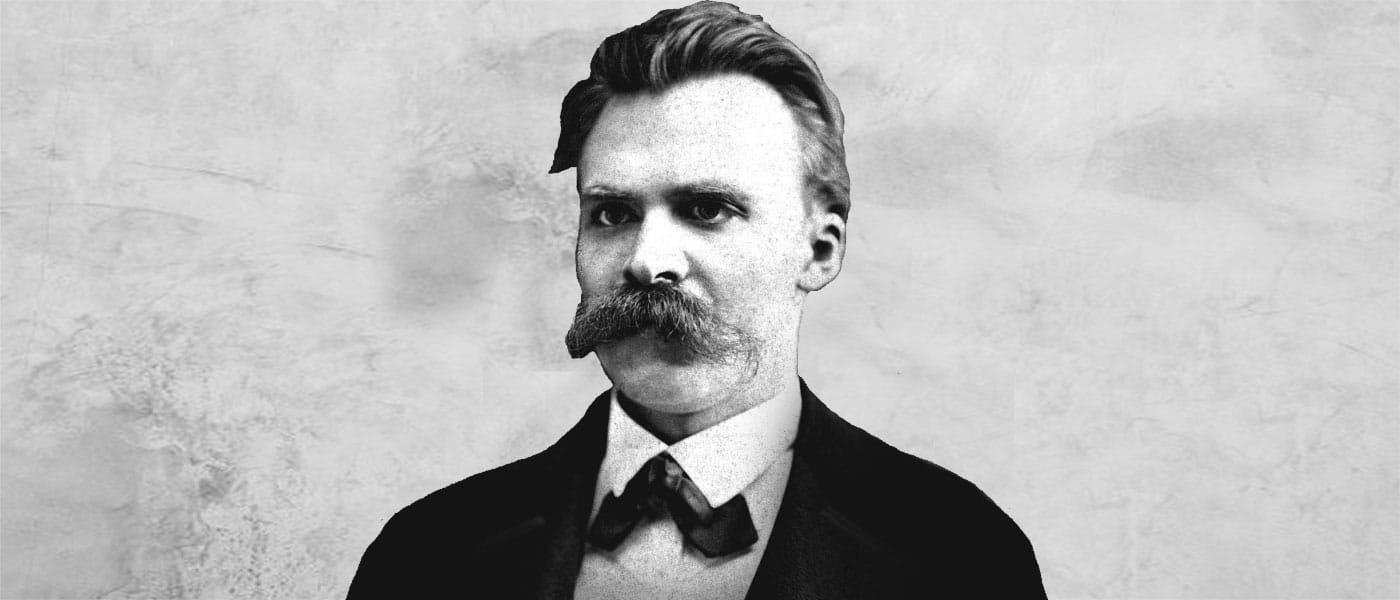

While philosophers including Søren Kierkegaard, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Friedrich Nietzsche questioned essentialism in the 19th century, existentialism was popularised by Jean-Paul Sartre in the mid-20th century following the horrific events of World War II.

As people questioned how something as catastrophically terrible as the Holocaust could have a predetermined purpose, existentialism provided a possible answer that perhaps it is the individual who determines their essence, not an omnipotent being.

The existentialist movement asked, “What if we exist first?”

At the time it was a revolutionary thought. You were created as a blank slate, tabula rasa, and it is up to you to discover your life’s purpose or meaning.

While not necessarily atheist, existentialists believe there is no divine intervention, fate or outside forces actively pushing you in particular directions. Every decision you make is yours. You create your own purpose through your actions.

The burden of too much freedom

This personal responsibility to shape your own life’s meaning carries significant anxiety-inducing weight. Many of us experience the so-called existential crisis where we find ourselves questioning our choices, career, relationships and the point of it all. We have so many options. How do we pick the right ones to create a meaningful and fulfilling life?

“Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does” – John-Paul Sartre

Freedom is usually presented positively but Sartre posed that your level of freedom is so great it’s “painful”. To fully comprehend your freedom, you have to accept that only you are responsible for creating or failing to create your personal purpose. Without rules or order to guide you, you have so much choice that freedom is overwhelming.

The absurd

Life can be silly. But this isn’t quite what existentialists mean when they talk about the absurd. They define absurdity as the search for answers in an answerless world. It’s the idea of being born into a meaningless place that then requires you to make meaning.

The absurd posits there is no one truth, no inherent rules or guidelines. This means you have to develop your own moral code to live by. Sartre cautioned looking to authority for guidance and answers because no one has them and there is no one truth.

Living authentically and bad faith

Coined by Sartre, the phrase “living authentically” means to live with the understanding of your responsibility to control your freedom despite the absurd. Any purpose or meaning in your life is created by you.

If you choose to live by someone else’s rules, be that anywhere between religion and the wishes of your parents, then you are refusing to accept the absurd. Sartre named this refusal “bad faith”, as you are choosing to live by someone else’s definition of meaning and purpose – not your own.

So, what’s the meaning of life?

If you’re now thinking like an existentialist, then the answer to this question is both elementary and infinitely complex. You have the answer, you just have to own it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Do we have to choose between being a good parent and good at our job?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Hope

We hope for fine weather on weekends and the best for our buddies – an obvious statement that hardly screams ethics.

But within our everyday desires for good things, lies a duty to each other and ourselves to only act on reasonably held hopes.

The ethics of hope

One of Immanuel Kant’s simple but resonant maxims is ‘ought implies can’. In other words, if you believe someone has an ethical responsibility to do something, it must be possible. No person is under any obligation to do what is impossible. You might call me a bad person for failing to fly through the sky and save someone falling from a great height. But your condemnation will be rejected as ill-founded for the simple reason only fictional characters can perform that feat.

Many other things – including extremely difficult things – are reasonably expected of others. A person might promise to climb Mount Everest (or at least make a serious attempt) prior to their 50thbirthday. This might present the greatest challenge imaginable. Yet we know scaling the heights of Everest is possible. As such, the person who made this promise is bound to honour their commitment.

Of course, at the time of making such a promise, no person can know with absolute certainty they will be able to meet the obligation they have taken on. There are just too many variables outside of their control that can frustrate their best laid plans. Weather conditions might lead to the closure of the mountain. The need to provide personal care to a loved one could extend well beyond any anticipated period. Given this, our ethical commitments are almost always tinged with a measure of hope.

What is hope?

Hope is an expectation that some desirable circumstance will arise. Hope sometimes blends into something closer to ‘faith’ – where belief about a state of affairs cannot be proven. However, for most people, most of the time, ‘hope’ is a reasonable expectation.

For example, if a person makes commitments that critically depend on other people keeping their promises, that person cannot know for certain they can honour their word. Yet, if these people are known and trusted, perhaps based on past experience, then a hopeful dependence on their performance would be reasonable.

The same can be said of other commitments, such as promising to meet for a picnic on a particular day. You might make the plan in the hopeful expectation of fine weather and do so with good grounds based on a checked forecast predicting clear skies.

There are two things to be noted here. First, some aspects of hope depend (for their reasonableness) on the ethical commitments of other people (for example, to keep promises). It follows there will often be a reciprocal ethical aspect to the practice of ‘reasonable’ hoping.

Second, it’s not enough to be naively hopeful. Instead, one needs to take reasonable efforts to ensure there is some basis for relying on a hoped-for circumstance. This is especially so if the hoped-for circumstance is of critical importance to matters of grave ethical significance – such as making a promise to someone.

Given this, there may be good grounds to calibrate commitments in line with the degree to which you might reasonably hope for a particular circumstance to prevail. For example, rather than making an open commitment to meet for a particular picnic on a particular day it might be better to qualify the point by saying, “I promise to meet you if the weather is fine”.

‘It’s not enough to be naively hopeful.’

We often see the absence of this kind of forethought when it comes to the promises made by politicians during elections. They will make promises – probably based on hopeful projections about the future – only to find themselves accused of lying or having acted in bad faith when the promise is not honoured.

It’s insufficient for the politician to say they merely ‘hoped’ to be able to keep their word and that they now find their situation to be unexpectedly different. It would have been far better and far more responsible to qualify the promise in line with what might explicitly and reasonably be hoped for.

Two final comments. First, it should be understood a person often has some control over whether or not their hopes can be realised. As such, each person is responsible for those of their actions that impinge on the way they meet their obligations – we are not simply ‘bystanders’ who can idly hope for certain outcomes without lifting a finger to make them manifest.

Second, given our inability to know what the future holds, hope always plays a role in the process of making ethical commitments. The key thing is to be reasonable in what we hope for and to calibrate our commitments accordingly.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Anarchy

Anarchy isn’t just street protests and railing against the establishment.

It’s a serious political philosophy that believes people will flourish in a leaderless society without a centralised government. It may sound like a crazy ideal, but it’s almost worked before.

A hastily circled letter Aetched into bus windows and spray painted on walls. The vigilante anarchist character known only as V from V for Vendetta. The Sex Pistols’ Johnny Rotten singing, “I wanna be anarchy”.

Think of anarchy and you might just imagine an 80s punk throwing a Molotov cocktail in a street protest. Easily conjuring rich imagery with a railing-against-the-orthodoxy rebelliousness, there’s more to anarchy than cool cachet. At the heart of this ideology is decentralisation.

Disorder versus political philosophy

The word anarchy is often used as an adjective to describe a state of public chaos. You’ll hear it dropped in news reports of civil unrest and riots with flavours of vandalism and violence. But anarchists aren’t traditionally looters throwing bricks through shop windows.

Anarchy is a political philosophy. Philographics – a series that defines complex philosophical concepts with a short sentence and simple graphic – describes anarchy as:

“A range of views that oppose the idea of the state as a means of governance, instead advocating a society based on non-hierarchical relationships.”

Instead of structured governments enforcing laws, anarchists believe people should be free to voluntarily organise and cooperate as they please. And because governments around the world are already established states with legal systems, many anarchists see their work is to abolish them.

The word anarchy derives from the ancient Greek term anarchia, which basically means “without leader” or “without authority”. Some literal translations put it as “not hierarchy”.

That may conjure notions of disorder, but the founder of anarchy imagined it to be a peaceful, cooperative thing.

“Anarchy is order without power” – Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the ‘father of anarchy’

The “father of anarchy”

The first known anarchist was French philosopher and politician Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. It’s perhaps notable he took office after the French Revolution of 1848 overthrew the monarchy. Eight years prior, Proudhon published the defining theoretical text that influenced later anarchist movements.

“Property is theft!”, Proudhon declared in his book, What is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government. His starting point for this argument was the Christian point of view that God gave Earth to all people.

This idea that natural resources are for equal share and use is also referred to as the universal commons. Proudhon felt it followed that private ownership meant land was stolen from everyone who had a right to benefit from it.

This premise is a crucial basis to Proudhon’s anarchist thesis because it meant people weren’t rightfully free to move in and use lands as they wished or required. Their means of production had been taken from them.

Anarchy’s heyday: the Spanish Civil War

Anarchy has usually been a European pursuit and it has waxed and waned in popularity. It had its most influence and reach in the years leading up to and during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), a time of great unrest and inequality between the working classes and ruling elite – which turned out to be a breeding ground for revolutionary thought.

Like the communist and socialist movements that grew alongside them, anarchists opposed the monarchy, land owning oligarchs and the military general Francisco Franco, who eventually took power.

Many different threads of the ideology gained popularity across Spain – some of it militant, some of it peaceful – and its sentiment was widely shared among everyday people.

Anarchist terrorists

While violence was never part of Proudhon’s ideal, it did become a key feature of some of the more well known examples of anarchy. First there was Spain which, perhaps by the nature of a civil war, saw many violent clashes between armed anarchists and the military.

Then there were the anarchist bomb attackers who operated around the world, perhaps most notably in late 19thand early 20thcentury America. They were basically yesteryear’s lone wolf terrorists.

Luigi Galleani was an Italian pro-violence anarchist based in the United States. He was eventually deported for taking part in and inspiring many bomb attacks. Reportedly, his followers, called Galleanists, were behind the 1920 Wall Street bombing that killed over 30 people and injured hundreds – the most severe terror attack in the US at the time.

No one ever claimed responsibility or was arrested for this bombing but fingers have long pointed at anti-capitalist anarchists inspired by post WWI conditions.

Could it come back?

While the law-breaking mayhem that can accompany a protest and the chaos of a collapsing society are labelled anarchy, there’s more to this sociopolitical philosophy. And if the conditions are right, we may just see another anarchist age.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Freedom of Speech

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Feminist porn stars debunked

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

Ethics Explainer: Scepticism

Scepticism is an attitude that treats every claim to truth as up for debate.

Religion, philosophy, science, history, psychology – generally, sceptics believe every source of knowledge has its limits, and it’s up to us to figure out what those are.

Sometimes confused with cynicism, a general suspicion of people and their motives, ethical scepticism is about questioning if something is right just because others say it is. If not, what will make it so?

Scepticism has played a crucial role in refining our basic understandings of ourselves and the world we live in. It is behind how we know everything is made of atoms, time isn’t linear, and that since Earth is a sphere, it’s quicker for planes to fly towards either pole instead of in a straight line.

Ancient ideas

In Ancient Greece, some sceptics went so far as to argue since nothing can claim truth it’s best to suspend judgement as long as possible. This enjoyed a revival in 17th century Europe, prompting one of the Western canon’s most famous philosophers, René Descartes, to mount a forceful critique. But before doing so, he wanted to argue for scepticism in as holistic a fashion as possible.

Descartes wanted to prove certain truths were innate and could not be contested. To do so, he started to pick out every claim to truth he could think of – including how we see the world – and challenge it.

For Descartes, perception was unreliable. You might think the world around you is real because you can experience it through your senses, but how do you know you’re not dreaming? After all, dreams certainly feel real when you’re in them. For a little modern twist, who’s to say you’re not a brain in a vat connected up to a supercomputer, living in a virtual reality uploaded into your buzzing synapses?

This line of thinking led Descartes to question his own existence. In the midst of a deeply valuable intellectual freak out, he eventually came to realise an irrefutable claim – his doubting proved he was thinking. From here, he deduced that ‘if I think’, then I exist.

“I think, therefore I am.”

It’s the quote you see plastered over t-shirts, mugs, and advertising for schools and universities. In Latin it reads, “Cogito ergo sum”.

Through a process of elimination, Descartes created a system of verifying truth claims through deduction and logic. He promoted this and quiet reflection as a way of living and came to be known as a rationalist.

The arrival of the empiricist

In the 18th century, a powerful case was made against rationalism by David Hume, an empiricist. Hume was sceptical of logical deduction’s ability to direct how people live and see the world. According to Hume, all claims to truth arise from experiences, custom and habit – not reason.

If we followed Descartes’ argument to its conclusion and assessed every single claim to truth logically, we wouldn’t be able to function. Navigating throughout the world requires a degree of trust based on past experiences. We don’t know for sure that the ground beneath us will stay solid. But considering it generally does, we trust (through inductive reasoning) that it will stay that way.

Hume argued memories and “passions” always, eventually, overrule reason. We are not what we think, but what we experience.

Perhaps you don’t question the nature of existence at the level of Descartes, but on some level, we are all sceptics. Scepticism is how we figure out who to confide in, what our triggers are, or if the next wellness fad is worth trying out. Acknowledging how powerful our habits and emotions are is key to recognising when we’re tempted to overlook the facts in favour of how something makes us feel.

But part of being a sceptic is knowing what argument will convince you. Otherwise, it can be tempting to reduce every claim to truth as a challenge to your personal autonomy.

Scepticism, in its best form, has opened up mind-boggling ways of thinking about ourselves and the world around us. Using it to be combative is a shortsighted and corrosive way to undermine the difficult task of living a well examined life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

What do boxers, political figures, and that guy who’s addicted to Reddit all have in common?

They’ve probably employed the techniques of stoicism. It’s an ancient Greek philosophy that offers to answer that million dollar question, what is the best life we can live?

Hard work, altruism, prayer or relationships don’t take the top dog spot for the stoic. Instead, they zoom out and divide the world (if you’ll forgive the simplicity) into black and white: what you can control and what you can’t.

It’s the lemonade school of philosophy. The central tenet being:

“When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.”

Stoics believe that everything around us operates according to the law of cause and effect, creating a rational structure of the universe called logos. This structure meant that something as awful as all your worldly possessions sinking into the ocean (Zeno of Cyprus), or as annoying as missing the last bus by a quarter of a minute, don’t make your life any worse. Your life remains as it is, nothing more, nothing less.

If you suffer, you suffer because of the judgements you’ve made about them. The ideal life where that didn’t happen is a fantasy, and there’s no point focusing on it. Just expect that pain, grief, disappointment and injustice are going to happen. It’s what you do in response to them that counts.

This philosophy was founded by said Zeno, who preached the virtues of tolerance and self control on a stone colonnade called the stoa poikile. It’s where stoicism found its name. It flourished in the Roman empire, with one of its most famous students being the emperor himself, Marcus Aurelius. Fragments of his personal writing survive in Meditations, revealing counsel remarkably humble and chastising for a man of his power.

Stoicism on emotion

Emotion presents an opportunity. There’s a reactive, immediate response, like blaming others when you feel ashamed, or panicking when you feel anxious. But there is a better reaction the stoics aim for. It matches the degree of impact, is appropriate for the context, is rationally sound, and in line with a good character.

Being angry at your partner for forgetting to put away the dishes isn’t the same as being angry at an oppressive government for torturing its citizens. But if it’s the emotion you focus on, all your good intentions aren’t guaranteed to stop you from messing up. After all, the red haze is formidable.

By practising this “slow thinking” and making it a habit, you can cultivate the same self discipline to develop virtues like courage and justice. It’s these that will ultimately give your life meaning.

For others, emotions are more like the weather. It rains and it shines, and you just deal with it.

Stoicism assumes that focusing on control and analysing emotion is how virtues are forged. But some critics, including philosopher Martha Nussbaum, say that approach misses a fundamental part of being human. After all, control is transient too. Emotions – loving and caring for someone or something to such an extent that losing it devastates you – doesn’t make you less human. It’s part of being human in the first place.

Other critics say that it leads to apathy, something collective political action can’t afford. Sandy Grant, philosopher at University of Cambridge, says stoicism’s “control fantasy” is ridiculous in our interdependent, globalised world. “It is no longer a matter of ‘What can I control?’ but rather of ‘Given that I, as all others, am implicated, what should I do?”

Controlling emotion to navigate through life cautiously may not be desirable to you. But it is easy to see how channelling stoicism in certain situations can help us manage life’s unfortunate moments – whether they be missing the bus or something more harrowing.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Big thinker

Relationships