Ethics Explainer: Teleology

Often, when we try to understand something, we ask questions like “What is it for?”. Knowing something’s purpose or end-goal is commonly seen as integral to comprehending or constructing it. This is the practice or viewpoint of teleology.

Teleology comes from two Greek words: telos, meaning “end, purpose or goal”, and logos, meaning “explanation or reason”.

From this, we get teleology: an explanation of something that refers to its end, purpose or goal.

For example, take a kitchen knife. We might ask why a knife takes the form and features that it does. If we referred to the past – to the process of its making, for example – that would be a causal (etiological) explanation. But a teleological explanation would be something that refers to its end, like: “Its purpose is to cut”. Someone might then ask: “But what makes a good knife?”, and the answer would be: “A good knife is a knife that cuts well.” It’s this guiding principle – knowing and focusing on the purpose – that allows knife-makers to make confident decisions in the smithing process and know that their knife is good, even if it’s never used.

What once was an acorn…

In Western philosophy, teleology originated in the writings and ideas of Plato and then Aristotle. For the Ancient Greeks, telos was a bit more grounded in the inherent nature of things compared to the man-made example of a knife.

For example, a seed’s telos is to grow into an adult plant. An acorn’s telos is to grow into an oak tree. A chair’s telos is to be sat on. For Aristotle, a telos didn’t necessarily need to involve any deliberation, intention or intelligence.

However, this is where teleological explanations have caused issue.

Teleological explanations are sometimes used in evolutionary biology as a kind of shorthand, much to the dismay of many scientists. This is because the teleological phrasing of biological traits can falsely present the facts as supporting some kind of intelligent design.

For example, take the long neck of giraffes. A shorthand teleological explanation of this trait might be that “evolution gave giraffes long necks for the purpose of reaching less competitive food sources”. However, this explanation wrongly implies some kind of forward-looking purpose for evolved traits, or that there is some kind of intention baked into evolution.

Instead, evolutionary biology suggests that giraffes with short necks were less likely to survive, leaving the longer-necked giraffes to breed and pass on their long-neck genes, eventually increasing the average length of their necks.

Notice how the accurate explanation doesn’t refer to any purpose or goal. This kind of description is needed when talking about things like nature or people (at least, if you don’t believe in gods), though teleological explanations can still be useful elsewhere.

Ethics and decision-making

Teleology is more helpful and impactful in ethics, or decision-making in general.

Aristotle was a big proponent of human teleology, seen in the concept of eudaimonia (flourishing). He believed that human flourishing was the goal or purpose of each person, and that we could all strive towards this “life well-lived” by living in moderation, according to various virtues.

Teleology is also often compared or confused with consequentialism, but they are not the same. If you were to take a business that specialises in home security, for example, a consequentialist would tell you to look at the consequences of your service to see if it is effective and good. Sometimes, though, it will be hard to tell if the outcome (e.g., fewer break-ins or attempted break-ins) can be attributed to your business and not other factors, like changes in laws, policing, homelessness, etc., or you might not yet have any outcomes to analyse.

Instead, teleological approaches to business decision-making would have you focus on the purpose of your service i.e., to prevent home intrusion and ensure security. With that in mind, you could construct your services to meet these goals in a variety of ways, keeping this purpose in mind when making hiring decisions, planning redundancies, etc., and be confident that your service would fulfil its purpose well (even if it is never needed!).

But how do we decide what a good purpose is?

Simply using a teleological lens doesn’t make us ethical. If we’re trying to be ethical, we want to make sure that our purpose itself is good. One option to do this is to find a purpose that is intrinsically good – things like justice, security, health and happiness, rather than things that are a means to an end, like profit or personal gain.

This viewpoint needn’t only apply to business. In trying to be better, more ethical people, we can employ these same teleological views and principles to inform our own decisions and actions. Rather than thinking about the consequences of our actions, we can instead think about what purpose we’re trying to achieve, and then form our decisions based on whether they align with that purpose.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Steven Pinker

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Violence and technology: a shared fate

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Power

Ethics Explainer: Power

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 11 MAR 2022

“If a white man wants to lynch me, that’s his problem. If he’s got the power to lynch me, that’s my problem. It’s not a question of attitude; it’s a question of power.” – Stokely Carmichael

A central concern of justice is who has power and how they should be allowed to use it. A central concern of the rest of us is how people with power in fact do use it. Both questions have animated ethicists and activists for hundreds of years, and their insights may help us as we try to create a just society.

A classic formulation is given by the eminent sociologist Max Weber, for whom power is “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance”. Michel Foucault, one of the century’s most prominent theorists of power, seems to echo this view: “if we speak of the structures or the mechanisms of power, it is only insofar as we suppose that certain persons exercise power over others”.

A rival view holds that instead of being a relation, power is a resource: like water, food, or money, power is a resource that a particular person or institution can accrue and it can therefore be justly or unjustly distributed. This view has been especially popular among feminist theorists who have used economic models of resource distribution to talk about gendered inequalities in social resources, including and especially power.

Susan Moller Okin is one prominent voice in this tradition:

“When we look seriously at the distribution of such critical social goods as power, self-esteem, opportunities for self-development … we find socially constructed inequalities between them, right down the list”.

What’s the difference between these two views? Why care? One answer is that our efforts to make power more just in society will depend on what kind of thing it is: if it’s a resource, such that problems of unfair power are problems of unequal distribution, we might be able to improve things by removing some power from some people – that way, they would no longer have more than others. This strategy would be less likely to work if power was a relation.

In addition to working out what power is, there are important moral questions about when it can be ethically used. This is a pressing question: As long as we live in societies, under democratic governments, or in states that use police forces and militaries to secure our goals, there will be at least one form of power to which everyone is subject: the power of the state.

The state is one of the only legitimate bearers of the power to use violence. If anyone else uses a weapon or a threat of imprisonment to secure their goals, we think they’re behaving illegitimately, but when the state does these things, we think it is – or can be – legitimate.

Since Plato, democracies have agreed that we need to allow and centralise some coercive power if we are to enforce our laws. Given the state’s unique power to use violence, it’s especially important that that power be just and fair. However, it’s challenging to spell what fair power is inside a democracy or how to design a system that will trend towards exemplifying it.

As Douglas Adams once wrote:

“The major problem with governing people – one of the major problems, for there are many – is that no-one capable of getting themselves elected should on any account be allowed to do the job”.

One recurring question for ‘fairness’ in political power is whether the people governed by the relevant political authority have a to obey that authority. When a state has the power to set laws and enforce them, for instance, does this issue a correlate duty for citizens to obey those laws? The state has duties to its people because it has so much power; but do people have reciprocal duties to their state, also rooted in its power?

Transposing this question into our personal lives, it’s sometimes thought that each of us has a kind of moral power to extract behaviour from others. If you don’t keep your promise, I can blame or sanction you into doing what you said you would. In other words, I can exercise my moral power to make claims of you. Does this sort of power work in the same way as political power? Is it possible for me to abuse my moral power over you; using it in ways that are unjust or unfair – and might you have a duty to obey that moral power?

Finally, we can ask valuable questions about what it is to be powerless. It’s certainly a site of complaint: many of us protest or object when we feel powerless. But how should we best understand it? Is powerlessness about actually being interfered with by others, or simply being susceptible to it, or vulnerable to it? For prominent philosopher Philip Pettit (AC), it’s the latter – to be “unfree” is to be vulnerable or susceptible to the other people’s whims, irrespective of whether they actually use their power against us.

If we want a more ethically ordered society, it’s important to understand how power works – and what goes wrong when it doesn’t.

Join us for the Ethics of Power on Thurs 14 March, 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Tolerance

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Despite codes of conduct, unethical behaviour happens: why bother?

Big thinker

Relationships

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

Research shows that physical appearance can affect everything from the grades of students to the sentencing of convicted criminals – are looks and morality somehow related?

Ancient philosophers spoke of beauty as a supreme value, akin to goodness and truth. The word itself alluded to far more than aesthetic appeal, implying nobility and honour – it’s counterpart, ugliness, made all the more shameful in comparison.

From the writings of Plato to Heraclitus, beautiful things were argued to be vital links between finite humans and the infinite divine. Indeed, across various cultures and epochs, beauty was praised as a virtue in and of itself; to be beautiful was to be good and to be good was to be beautiful.

When people first began to ask, ‘what makes something (or someone) beautiful?’, they came up with some weird ideas – think Pythagorean triangles and golden ratios as opposed to pretty colours and chiselled abs. Such aesthetic ideals of order and harmony contrasted with the chaos of the time and are present throughout art history.

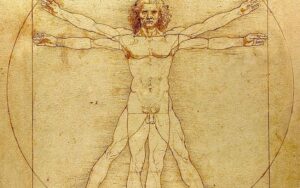

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, c.1490

These days, a more artificial understanding of beauty as a mere observable quality shared by supermodels and idyllic sunsets reigns supreme.

This is because the rise of modern science necessitated a reappraisal of many important philosophical concepts. Beauty lost relevance as a supreme value of moral significance in a time when empirical knowledge and reason triumphed over religion and emotion.

Yet, as the emergence of a unique branch of philosophy, aesthetics, revealed, many still wondered what made something beautiful to look at – even if, in the modern sense, beauty is only skin deep.

Beauty: in the eye of the beholder?

In the ancient and medieval era, it was widely understood that certain things were beautiful not because of how they were perceived, but rather because of an independent quality that appealed universally and was unequivocally good. According to thinkers such as Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, this was determined by forces beyond human control and understanding.

Over time, this idea of beauty as entirely objective became demonstrably flawed. After all, if this truly were the case, then controversy wouldn’t exist over whether things are beautiful or not. For instance, to some, the Mona Lisa is a truly wonderful piece of art – to others, evidence that Da Vinci urgently needed an eye check.

Consequently, definitions of beauty that accounted for these differences in opinion began to gain credence. David Hume famously quipped that beauty “exists merely in the mind which contemplates”. To him and many others, the enjoyable experience associated with the consumption of beautiful things was derived from personal taste, making the concept inherently subjective.

This idea of beauty as a fundamentally pleasurable emotional response is perhaps the closest thing we have to a consensus among philosophers with otherwise divergent understandings of the concept.

Returning to the debate at hand: if beauty is not at least somewhat universal, then why do hundreds and thousands of people every year visit art galleries and cosmetic surgeons in pursuit of it? How can advertising companies sell us products on the premise that they will make us more beautiful if everyone has a different idea of what that looks like? Neither subjectivist nor objectivist accounts of the concept seem to adequately explain reality.

According to philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and Francis Hutcheson, the answer must lie somewhere in the middle. Essentially, they argue that a mind that can distance itself from its own individual beliefs can also recognize if something is beautiful in a general, objective sense. Hume suggests that this seemingly universal standard of beauty arises when the tastes of multiple, credible experts align. And yet, whether or not this so-called beautiful thing evokes feelings of pleasure is ultimately contingent upon the subjective interpretation of the viewer themselves.

Looking good vs being good

If this seemingly endless debate has only reinforced your belief that beauty is a trivial concern, then you are not alone! During modernity and postmodernity, philosophers largely abandoned the concept in pursuit of more pressing matters – read: nuclear bombs and existential dread. Artists also expressed their disdain for beauty, perceived as a largely inaccessible relic of tired ways of thinking, through an expression of the anti-aesthetic.

Nevertheless, we should not dismiss the important role beauty plays in our day-to-day life. Whilst its association with morality has long been out of vogue among philosophers, this is not true of broader society. Psychological studies continually observe a ‘halo effect’ around beautiful people and things that see us interpret them in a more favourable light, leading them to be paid higher wages and receive better loans than their less attractive peers.

Social media makes it easy to feel that we are not good enough, particularly when it comes to looks. Perhaps uncoincidentally, we are, on average, increasing our relative spending on cosmetics, clothing, and other beauty-related goods and services.

Turning to philosophy may help us avoid getting caught in a hamster wheel of constant comparison. From a classical perspective, the best way to achieve beauty is to be a good person. Or maybe you side with the subjectivists, who tell us that being beautiful is meaningless anyway. Irrespective, beauty is complicated, ever-important, and wonderful – so long as we do not let it unfairly cloud our judgements.

Step through the mirror and examine what makes someone (or something) beautiful and how this impacts all our lives. Join us for the Ethics of Beauty on Thur 29 Feb 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical school of thought that, broadly, is interested in the effects and usefulness of theories and claims.

Pragmatism is a distinct school of philosophical thought that began at Harvard University in the late 19th century. Charles Sanders Pierce and William James were members of the university’s ‘Metaphysical Club’ and both came to believe that many disputes taking place between its members were empty concerns. In response, the two began to form a ‘Pragmatic Method’ that aimed to dissolve seemingly endless metaphysical disputes by revealing that there was nothing to argue about in the first place.

How it came to be

Pragmatism is best understood as a school of thought born from a rejection of metaphysical thinking and the traditional philosophical pursuits of truth and objectivity. The Socratic and Platonic theories that form the basis of a large portion of Western philosophical thought aim to find and explain the “essences” of reality and undercover truths that are believed to be obscured from our immediate senses.

This Platonic aim for objectivity, in which knowledge is taken to be an uncovering of truth, is one which would have been shared by many members of Pierce and James’ ‘Metaphysical Club’. In one of his lectures, James offers an example of a metaphysical dispute:

A squirrel is situated on one side of a tree trunk, while a person stands on the other. The person quickly circles the tree hoping to catch sight of the squirrel, but the squirrel also circles the tree at an equal pace, such that the two never enter one another’s sight. The grand metaphysical question that follows? Does the man go round the squirrel or not?

Seeing his friends ferociously arguing for their distinct position led James to suggest that the correctness of any position simply turns on what someone practically means when they say, ‘go round’. In this way, the answer to the question has no essential, objectively correct response. Instead, the correctness of the response is contingent on how we understand the relevant features of the question.

Truth and reality

Metaphysics often talks about truth as a correspondence to or reflection of a particular feature of “reality”. In this way, the metaphysical philosopher takes truth to be a process of uncovering (through philosophical debate or scientific enquiry) the relevant feature of reality.

On the other hand, pragmatism is more interested in how useful any given truth is. Instead of thinking of truth as an ultimately achievable end where the facts perfectly mirror some external objective reality, pragmatism instead regards truth as functional or instrumental (James) or the goal of inquiry where communal understanding converges (Pierce).

Take gravity, for example. Pragmatism doesn’t view it as true because it’s the ‘perfect’ understanding and explanation for the phenomenon, but it does view it as true insofar as it lets us make extremely reliable predictions and it is where vast communal understanding has landed. It’s still useful and pragmatic to view gravity as a true scientific concept even if in some external, objective, all-knowing sense it isn’t the perfect explanation or representation of what’s going on.

In this sense, truth is capable of changing and is contextually contingent, unlike traditional views.. Pragmatism argues that what is considered ‘true’ may shift or multiply when new groups come along with new vocabularies and new ways of seeing the world.

To reconcile these constantly changing states of language and belief, Pierce constructed a ‘Pragmatic Maxim’ to act as a method by which thinkers can clarify the meaning of the concepts embedded in particular hypotheses. One formation of the maxim is:

Consider what effects, which might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of those effects is the whole of our conception of the object.

In other words, Pierce is saying that the disagreement in any conceptual dispute should be describable in a way which impacts the practical consequences of what is being debated. Pragmatic conceptions of truth take seriously this commitment to practicality. Richard Rorty, who is considered a neopragmatist, writes extensively on a particular pragmatic conception of truth.

Rorty argues that the concept of ‘truth’ is not dissimilar to the concept of ‘God’, in the way that there is very little one can say definitively about God. Rorty suggests that rather than aiming to uncover truths of the world, communities should instead attempt to garner as much intersubjective agreement as possible on matters they agree are important.

Rorty wants us to stop asking questions like, ‘Do human beings have inalienable human rights?’, and begin asking questions like, ‘Should we work towards obtaining equal standards of living for all humans?’. The first question is at risk of leading us down the garden path of metaphysical disputes in ways the second is not. As the pragmatist is concerned with practical outcomes, questions which deal in ‘shoulds’ are more aligned with positing future directed action than those which get stuck in metaphysical mud.

Perhaps the pragmatists simply want us to ask ourselves: Is the question we’re asking, or hypothesis that we’re posing, going to make a useful difference to addressing the problem at hand? Useful, as Rorty puts it, is simply that which gets us more of what we want, and less of what we don’t want. If what we want is collective understanding and successful communication, we can get it by testing whether the questions we are asking get us closer to that goal, not further away.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Only love deserves loyalty, not countries or ideologies

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 22 NOV 2021

Autonomy is the capacity to form beliefs and desires that are authentic and in our best interests, and then act on them.

What is it that makes a person autonomous? Intuitively, it feels like a person with a gun held to their head is likely to have less autonomy than a person enjoying a meandering walk, peacefully making a choice between the coastal track or the inland trail. But what exactly are the conditions which determine someone’s autonomy?

Is autonomy just a measure of how free a person is to make choices? How might a person’s upbringing influence their autonomy, and their subsequent capacity to act freely? Exploring the concept of autonomy can help us better understand the decisions people make, especially those we might disagree with.

The definition debate

Autonomy, broadly speaking, refers to a person’s capacity to adequately self-govern their beliefs and actions. All people are in some way influenced by powers outside of themselves, through laws, their upbringing, and other influences. Philosophers aim to distinguish the degree to which various conditions impact our understanding of someone’s autonomy.

There remain many competing theories of autonomy.

These debates are relevant to a whole host of important social concerns that hinge on someone’s independent decision-making capability. This often results in people using autonomy as a means of justifying or rebuking particular behaviours. For example, “Her boss made her do it, so I don’t blame her” and “She is capable of leaving her boyfriend, so it’s her decision to keep suffering the abuse” are both statements that indirectly assess the autonomy of the subject in question.

In the first case, an employee is deemed to lack the autonomy to do otherwise and is therefore taken to not be blameworthy. In the latter case, the opposite conclusion is reached. In both, an assessment of the subject’s relative autonomy determines how their actions are evaluated by an onlooker.

Autonomy often appears to be synonymous with freedom, but the two concepts come apart in important ways.

Autonomy and freedom

There are numerous accounts of both concepts, so in some cases there is overlap, but for the most part autonomy and freedom can be distinguished.

Freedom tends to broader and more overt. It usually speaks to constraints on our ability to act on our desires. This is sometimes also referred to as negative freedom. Autonomy speaks to the independence and authenticity of the desires themselves, which directly inform the acts that we choose to take. This is has lots in common with positive freedom.

For example, we can imagine a person who has the freedom to vote for any party in an election, but was raised and surrounded solely by passionate social conservatives. As a member of a liberal democracy, they have the freedom to vote differently from the rest of their family and friends, but they have never felt comfortable researching other political viewpoints, and greatly fear social rejection.

If autonomy is the capacity a person has to self-govern their beliefs and decisions, this voter’s capacity to self-govern would be considered limited or undermined (to some degree) by social, cultural and psychological factors.

Relational theories of autonomy focus on the ways we relate to others and how they can affect our self-conceptions and ability to deliberate and reason independently.

Relational theories of autonomy were originally proposed by feminist philosophers, aiming to provide a less individualistic way of thinking about autonomy. In the above case, the voter is taken to lack autonomy due to their limited exposure to differing perspectives and fear of ostracism. In other words, the way they relate to people around them has limited their capacity to reflect on their own beliefs, values and principles.

One relational approach to autonomy focuses on this capacity for internal reflection. This approach is part of what is known as the ‘procedural theory of relational autonomy’. If the woman in the abusive relationship is capable of critical reflection, she is thought to be autonomous regardless of her decision.

However, competing theories of autonomy argue that this capacity isn’t enough. These theories say that there are a range of external factors that can shape, warp and limit our decision-making abilities, and failing to take these into account is failing to fully grasp autonomy. These factors can include things like upbringing, indoctrination, lack of diverse experiences, poor mental health, addiction, etc., which all affect the independence of our desires in various ways.

Critics of this view might argue that a conception of autonomy is that is broad makes it difficult to determine whether a person is blameworthy or culpable for their actions, as no individual remains untouched by social and cultural influences. Given this, some philosophers reject the idea that we need to determine the particular conditions which render a person’s actions truly ‘their own’.

Maybe autonomy is best thought of as merely one important part of a larger picture. Establishing a more comprehensively equitable society could lessen the pressure on debates around what is required for autonomous action. Doing so might allow for a broadening of the debate, focusing instead on whether particular choices are compatible with the maintenance of desirable societies, rather than tirelessly examining whether or not the choices a person makes are wholly their own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

“Animal rights should trump human interests” – what’s the debate?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Lying is something we’ve all done at some point and we tend to take its meaning for granted, but what are we really doing when we lie, and is it ever okay?

A person lies when they:

- knowingly communicate something false

- purposely communicate it as if it was true

- do so with an intention to deceive.

The intention to deceive is an essential component of lying. Take a comedian, for example – they might intentionally present a made-up story as true when telling a joke, engaging in satire, etc. However, the comedian’s purpose is not to deceive but to entertain.

Lying should be distinguished from other deviations from the truth like:

- Falsehoods – false claims we make while believing what we say to be true

- Equivocations – the use of ambiguous language that allows a person to persist in holding a false belief.

While these are different to lying, they can be equally problematic. Accidentally communicating false information can still result in disastrous consequences. People in positions of power (e.g., government ministers) have an obligation to inform themselves about matters under their control or influence and to minimise the spread of falsehoods. Having a disregard for accuracy, while it is not lying, should be considered wrong – especially when as a result of negligence or indifference.

The same can be said of equivocation. The intention is still there, but the quality of exchange is different. Some might argue that purposeful equivocation is akin to “lying by omission”, where you don’t actively tell a lie, but instead simply choose not to correct someone else’s misunderstanding.

Despite lying being fairly common, most of our lives are structured around the belief that people typically don’t do it.

We believe our friends when we ask them the time, we believe meteorologists when they tell us the weather, we believe what doctors say about our health. There are exceptions, of course, but for the most part we assume people aren’t lying. If we didn’t, we’d spend half our days trying to verify what everyone says!

In some cases, our assumption of honesty is especially important. Democracies, for example, only function legitimately when the government has the consent of its citizens. This consent needs to be:

- free (not coerced)

- prior (given before the event needing consent)

- informed (based on true and accessible information)

Crucially, informed consent can’t be given if politicians lie in any aspects of their governance.

So, when is lying okay? Can it be justified?

Some philosophers, notably Immanuel Kant, argue that lying is always wrong – regardless of the consequences. Kant’s position rests on something called the “categorical imperative”, which views lying as immoral because:

- it would be fundamentally contradictory (and therefore irrational) to make a general rule that allows lying because it would cause the concepts of lies and truths to lose their meaning

- it treats people as a means rather than as autonomous beings with their own ends

In contrast, consequentialists are less concerned with universal obligations. Instead, their foundation for moral judgement rests on consequences that flow from different acts or rules. If a lie will cause good outcomes overall, then (broadly speaking) a consequentialist would think it was justified.

There are other things we might want to consider by themselves, outside the confines of a moral framework. For example, we might think that sometimes people aren’t entitled to the truth in principle. For example, during a war, most people would intuit that the enemy isn’t entitled to the truth about plans and deployment details, etc. This leads to a more general question: in what circumstances do people forfeit their right to the truth?

What about “white lies”? These lies usually benefit others (sometimes at the liar’s expense!) or are about trivial things. They’re usually socially acceptable or at least tolerated because they have harmless or even positive consequences. For example, telling someone their food is delicious (even though it’s not) because you know they’ve had a long day and wouldn’t want to hurt their feelings.

Here are some things to ask yourself if you’re about to tell a white lie:

- Is there a better response that is truthful?

- Does the person have a legitimate right to receive an honest answer?

- What is at stake if you give a false or misleading answer? Will the person assume you’re telling the truth and potentially harm themselves as a result of your lie? Will you be at fault?

- Is trust at the foundation of the relationship – and will it be damaged or broken if the white lie is found out?

- Is there a way to communicate the truth while minimising the hurt that might be caused? For example, does the best response to a question about an embarrassing haircut begin with a smile and a hug before the potentially hurtful response?

Lying is a more complex phenomenon than most people consider. Essentially, our general moral aversion to it comes down to its ability to inhibit or destroy communication and cooperation – requirements for human flourishing. Whether you care about duties, consequences or something else, it’s always worth questioning your intentions to check if you are following your moral compass.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Big Thinker: Baruch Spinoza

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Epistemology

Mostly, we take “knowledge” or “knowing” for granted, but the philosophical study of knowledge has had a long and detailed history that continues today.

We constantly claim to ‘know things’. We know the sun will rise tomorrow. We know when we drop something, it will fall. We know a factoid we read in a magazine. We know our friend’s cousin’s girlfriend’s friend saw a UFO that one time.

You might think that some of these claims aren’t very good examples of knowledge, and that they’d be better characterised as “beliefs” – or more specifically, unjustified beliefs. Well, it turns out that’s a pretty important distinction.

“Epistemology” comes from the Greek words “episteme” and “logos”. Translations vary slightly, but the general meaning is “account of knowledge”, meaning that epistemology is interested in figuring out things like what knowledge is, what counts as knowledge, how we come to understand things and how we justify our beliefs. In turn, this links to questions about the nature of ‘truth’.

So, what is knowledge?

A well-known, though still widely contentious, view of knowledge is that it is justified true belief.

This idea dates all the way back to Plato, who wrote that merely having a true belief isn’t sufficient for knowledge. Imagine that you are sick. You have no medical expertise and have not asked for any professional advice and yet you believe that you will get better because you’re a generally optimistic person. Even if you do get better, it doesn’t follow that you knew you were going to get better – only that your belief coincidentally happened to be true.

So, Plato suggested, what if we added the need for a rational justification for our belief on top of it being true? In order for us to know something, it doesn’t just need to be true, it also needs to be something we can justify with good reason.

Justification comes with its own unique problems, though. What counts as a good reason? What counts as a solid foundation for knowledge building?

The two classical views in epistemology are that we should rely on the perceptual experiences we gain through our senses (empiricism) or that we should rely first and foremost on pure reason because our senses can deceive us (rationalism). Well-known empiricists include John Locke and David Hume; well-known rationalists include René Descartes and Baruch Spinoza.

Though Plato didn’t stand by the justified true belief view of knowledge, it became quite popular up until the 20th century, when Edmund Gettier blew the problem wide open again with his paper “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?”.

Since then, there has been very little consensus on the definition, with many philosophers claiming that it’s impossible to create a definition of knowledge without exceptions.

Some more modern subfields within epistemology are concerned with the mechanics of knowledge between people. Feminist epistemology, and social epistemology more broadly, deals with a lot of issues that raise ethical questions about how we communicate and perceive knowledge from others.

Prominent philosophers in this field include Miranda Fricker and José Medina. Fricker developed the concept of “epistemic injustice”, referring to injustices that involve the production, communication and understanding of knowledge.

One type of knowledge-based injustice that Fricker focuses on, and that has large ethical considerations, is testimonial injustice. These are injustices of a kind that involve issues in the way that testimonies – the act of telling people things – are communicated, understood, believed. It largely involves the interrogation of prejudices that unfairly shape the credibility of speakers.

Sometimes we give people too much credibility because they are attractive, charismatic or hold a position of power. Sometimes we don’t give people enough credibility because of a race, gender, class or other forms of bias related to identity.

These types of distinctions are at the core of ethical communication and decision-making.

When we interrogate our own views and the views of others, we want to be asking ourselves questions such as: Have I made any unfair assumptions about the person speaking? Are my thoughts about this person and their views justified? Is this person qualified? Did I get my information from a reliable source?

In short, a healthy degree of scepticism (and self-examination) should be used to filter through information that we receive from others and to question our initial attitudes towards information that we sometimes take for granted or ignore. In doing this, we can minimise misinformation and make sure that we’re appropriately treating those who have historically been and continue to be silenced and ignored.

Ethics draws attention to the quality and character of the decisions we make. We typically hold that decisions are better if well-informed … which is another way of saying that when it comes to ethics, knowledge matters!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Sometimes life can seem overwhelming. Often, it’s because we can’t help focusing on the bad stuff and forgetting about the good.

Don’t feel too bad. We’re hard-wired to be more impacted by negative events, feelings and thoughts than those things that are positive. Surprisingly, when experiencing two experiences that have equal intensity, we’ll get stuck on the negative rather than the positive.

This psychological phenomenon is called negativity bias, which is a type of unconscious bias. Unconscious biases are attitude and judgements that aren’t obvious or known to us but still affect our thinking and actions. They are often in play despite the fact we may consciously hold a different view. They’re not called unconscious for nothing.

This is an especially tricky aspect of negativity bias since we tend not to notice ourselves latching onto the negative aspects of any given situation, which makes preventing a psychological spiral all the more difficult.

We’ve all experienced how easy it is to spiral due to the one hater who pops up in in our Insta or Twitter feed despite the many positive comments we could be basking in. This is the pernicious power of negativity bias – we are disproportionately affected by negative experiences rather than the positive.

Remember that time a co-worker or friend said something irritating to you near the beginning of the day and it remained in your mind the whole day, despite other positive things happening like being complimented by a stranger and getting lots of work done? Of course you remember it. Because our memories are also drawn like a magnet to those negative experiences even when far outweighed by the positive experiences that surrounded it. You might have finished that day still feeling down because you hadn’t been able to forget about the comment, despite the day on the whole having been pretty good.

Something that’s been prevalent for the past two years is negativity around various COVID-19 measures. It’s easy for us to focus on the frustration of forgetting to take our mask with us somewhere or the inconvenience of constantly checking-in. Often these small things can linger in our minds or affect our moods, while small positive things will go almost unnoticed.

Negativity bias can also affect things outside our mood. It can affect our perceptions of people and our decision making.

It also causes us to focus on or amplify the negative aspects of someone’s character, resulting in us expecting the worst of them or seeing them in a broadly negative light. Assuming someone’s intentions are negative is a common way that arguments and misunderstandings occur.

It can also heavily affect our decision-making process, an effect demonstrated by Nobel Prize winners Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who were groundbreakers in uncovering the role of unconscious bias. Over-emphasising negative aspects of situations can, for example, cause us to misperceive risk and act in ways we normally wouldn’t. Imagine walking down the street and losing $50. How does that feel? Now imagine walking down that same street and finding $50. How different does it feel to find, rather than lose $50? Kahneman used this experiment to show that we are loss averse – even though the amount is the same, most people will feel worse having lost something than having found something, even when it is of equal value.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. Research suggests that this bias comes from our early need to be attentive to danger, and there are various ways we can remain attentive to possible threats while stemming the effect of negativity on our mental state.

Minimising negativity bias can be difficult, especially when we focus on compounding problems, but here are a few things to remind ourselves of that can help combat negativity spirals.

- Make the most of positive moments. It’s easy to fall into a habit of glossing over small victories but taking a few minutes to slow down and appreciate a sunny day, or a compliment from a friend, or a nice meal can help to take the negative winds out of our sails.

- Actively self-reflect. This can include things like recognising and acknowledging negative self-talk, trying to reframe the way you speak about things to others in a more positive light and double-checking that when you do interpret something as negative that it is proportionate to the threat or harm it poses. If it’s not, take some time to reassess.

- Develop new habits. In combination with making an effort to recognise negative thought patterns, we can develop habits that help to counteract them. Pay attention to what activities give you mental space or clarity, or tend to make you happy, and try to do them when you can’t quite shake the negativity off. It could be as simple as going for a walk, reading a book, or listening to feel-good music.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Education is more than an employment outcome

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Relativism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Blame

In an age of ubiquitous media coverage on anything and everything, most people see blaming behaviour every day. But what exactly is blame? How do we do it? Why do we do it?

During the 2019-20 bushfires, the Prime Minister Scott Morrison was blamed for taking a vacation during an environmental crisis. During a peak in the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, protestors in Australia blamed individual police and the government at large for the historical and present violent mistreatment of First Nations people.

Maybe you still blame your overly angry high school teacher for making you an anxious person. Maybe you blamed your co-worker recently for standing you up on your weekly Zoom call.

Whatever the stakes, we are all familiar with blaming, but could you explain what it is?

At a very basic level, blame is considered a negative reaction that we have towards someone we perceive as having broken a moral norm, leaving us feeling wronged.

There are several theories of blame that explore different interpretations of how exactly it works, but an overarching distinction is that of how or whether it’s communicated.

On the one hand, we have communicative blame – this is the outward behaviour that indicates one person blames another for something. When we yell at someone for running a red light, scold a politician on social media, or tell someone we are disappointed with their actions, we are communicating blame. Sometimes blame can even be communicated subtly, in the small ways we speak or act.

Some people think that it’s necessary for blame to be communicated – that blame without this overt aspect isn’t quite blame. On the other hand, some people think that there can be internal blame, where a person never outwardly acknowledges that they blame someone for something but still holds an internalised judgement and emotion or desire – imagine someone who holds a grudge against a friend who moved across the world but doesn’t speak to them anymore.

When we think about blame, we have to ask ourselves why do we blame, what does it do and when is it ok?

A common answer looks towards history and especially religion. In the Bible, for example, blame is often seen to hold us to account and discourage dissent. Blame has often been (and is still) used as a social and political indicator of what’s acceptable to citizens and/or governments.

This is more obvious when we consider communicative blame. Take for example, the way that the Australian public and news media communicated their blame of the Prime Minister during his bushfire vacation. These expressions ranged from simply showing dissatisfaction, to more complex indications of a desire for change and a serious acknowledgement of a moral failing.

And it also goes the other way. During the 2021 daily COVID-19 press conferences, various politicians have been quick to communicate their blame towards various groups of people flouting public health orders.

But is this type behaviour always okay? Is it always effective? These are the kinds of questions ethicists ask and attempt to answer when thinking at things like blame. One way to think about these questions is to look at them through different ethical frameworks.

Consequentialism tells us to pay attention to the outcomes of our actions, dispositions, attitudes, etc. A consequentialist might argue that we shouldn’t communicate blame if it would cause worse consequences than if we kept it to ourselves.

For example, if a child does something wrong, a consequentialist might say that sometimes it’s better to not outwardly blame them and instead do something else. Perhaps give them the tools to fix the mistake or praise them for a different aspect of the situation that they did well.

Less intuitively, though, is the implication that sometimes it will be wrong to blame someone for something, even if they deserve it! Say you have a friend who is very contrarian and does the wrong thing on purpose to get attention. Some consequentialists might say that it is wrong to communicate blame to them because under these circumstances you’re encouraging the behaviour, since they want the attention of being blamed. This might be a frustrating conclusion for people who think others get what they deserve by being blamed.

A deontologist might help them here and say that if someone is blameworthy then they deserve to be blamed and it is our duty to blame them, regardless of the consequences. Some deontologists might say that as long as our intentions are good, then we have a responsibility to blame wrongdoers and show them their moral failing.

Some different issues arise with that. Does this mean we are obligated to blame someone who “deserves it”? What about in situations where blaming would have really bad consequences? Is it still our duty to blame them for their wrongdoing?

Next time you go to blame someone, think about your intentions and what you are hoping to achieve by taking that action. It might be that you’re better off keeping it to yourself or finding a more positive way to frame the situation. Maybe the best consequences are to be gained by blaming or maybe you do just deserve to get that frustration off your chest.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Deontology

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Easter and the humility revolution

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jeremy Bentham

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

ExplainerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 23 JUL 2021

Imagine waking up in a bed, disoriented, bleary-eyed and confused.

You can’t remember how you got to there, and the bed you’re in doesn’t feel familiar. As you start to get a sense of your surroundings, you notice a bunch of medical equipment around. You notice plugs and tubes coming out of your body and realise you’re back-to-back with another person.

A glimpse in the mirror tells you the person you’re attached to is a world-famous violinist – one with a fatal kidney ailment. And now, you start to realise what’s happened. Last night, you were invited to be the guest of honour at an event hosted by the Society of Music Lovers. During the event, they told you about this violinist – whose prodigious talent would be taken from the world too soon if they couldn’t find a way to fix him.

It looks like, based on the medical records strewn around the room, the Society of Music Lovers have been scouring the globe for someone whose blood type and genetic markers are a match with the violinist.

A doctor enters the room, looking distressed. She informs you that the Society of Music Lovers drugged and kidnapped you, and had your circulatory system hooked you up to the violinist. That way, your healthy kidney can extract the poisons from the blood and the violinist will be cured – and you’ll be completely healthy at the end of the process. Unfortunately, the procedure is going to take approximately 40 weeks to complete.

“Look, we’re sorry the Society of Music Lovers did this to you–we would never have permitted it if we had known,” the doctor apologises to you. “But still, they did it, and the violinist is now plugged into you. To unplug you would be to kill him. But never mind, it’s only for nine months. By then he will have recovered from his ailment and can safely be unplugged from you.”

After all, the doctor explains, “all persons have a right to life, and violinists are persons. Granted you have a right to decide what happens in and to your body, but a person’s right to life outweighs your right to decide what happens in and to your body. So you cannot be unplugged from him.”

This thought experiment originates in American philosopher Judith Jarvis Thompson’s famous paper ‘In Defence of Abortion’ and, in case you hadn’t figured it out, aims to recreate some of the conditions of pregnancy in a different scenario. The goal is to test how some of the moral claims around abortion apply to a morally similar, contextually different situation.

Thomson’s question is simple: “Is it morally incumbent on you to accede to this situation?” Do you have to stay plugged in? “No doubt it would be very nice of you if you did, a great kindness. But do you have to accede to it?” Thomson asks.

Thomson believes most people would be outraged at the suggestion that someone could be subjected to nine months of medical interconnectedness as a result of being drugged and kidnapped. Yet, Thomson explains, this is more-or-less what people who object to abortion – even in cases where the pregnancy occurred as a result of rape – are claiming.

Part of what makes the thought experiment so compelling is that we can tweak the variables to mirror more closely a bunch of different situations – for instance, one where the person’s life is at risk by being attached to the violinist. Another where they are made to feel very unwell, or are bed-ridden for nine months… the list goes on.

But Thomson’s main goal isn’t to tweak an admittedly absurd scenario in a million different ways to decide on a case-by-case basis whether an abortion is OK or not. Instead, her thought experiment is intended to show the implausibility of the doctor’s final argument: that because the violinist has a right to life, you are therefore obligated to be bound to him for nine months.

“This argument treats the right to life as if it were unproblematic. It is not, and this seems to me to be precisely the source of the mistake,” she writes.

Instead, Thomson argues that the right to life is, actually, a right ‘not to be killed unjustly’.

Otherwise, as the thought experiment shows us, the right to life leads to a situation where we can make unjust claims on other people.

For example, if someone needs a kidney transplant and they have the absolute right to life – which Thomson understands as “a right to be given at least the bare minimum one needs for continued life” – then someone who refused to donate their kidney would be doing something wrong.

Thinking about a “right to life” leads us to weird conclusions, like that if my kidneys got sick, I might have some entitlement to someone else’s organs, which intuitively seems weird and wrong, though if I ever need a kidney, I reserve the right to change my mind.

Interestingly, Thomson’s argument – written in 1971 – does leave open the possibility of some ethical judgements around abortion. She tweaks her thought experiment so that instead of being connected to the violinist for nine months, you need only be connected for an hour. In this case, given the relatively minor inconvenience, wouldn’t it be wrong to let the violinist die?

Thomson thinks it would, but not because the violinist has a right to use your circulatory system. It would be wrong for reasons more familiar to virtue ethics – that it was selfish, callous, cruel etc…

Part of the power of Thomson’s thought experiment is to enable a sincere, careful discussion over a complex, loaded issue in a relatively safe environment. It gives us a sense of psychological distance from the real issue. Of course, this is only valuable if Thomson has created a meaningful analogy between the famous violinist and what an actual unwanted pregnancy is like. Lots of abortion critics and defenders alike would want to reject aspects of Thomson’s argument.

Nevertheless, Thomson’s paper continues to be taught not only as an important contribution to the ethical debate around abortion, but as an excellent example of how to build a careful, convincing argument.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

A foot in the door: The ethics of internships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology