Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz on diversity and urban sustainability

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz on diversity and urban sustainability

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 16 NOV 2022

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz is the CEO of Mirvac, one of Australia’s largest and most respected property groups. Driven by the company’s purpose, to Reimagine Urban Life, Susan talks about how we can redefine the landscape and create more sustainable, connected and vibrant urban environments, leaving a legacy for generations to come.

“When you’re in high school you can only imagine doing the jobs you can see – you can think about being a doctor, a nurse, a lawyer because those jobs exist. But I always say to my own children that the jobs that they’re going to do don’t even exist yet.”

Susan’s parents took a huge risk when they migrated from Belfast in Northern Ireland to Australia, during the Winter of Discontent in 1978 which was characterised by widespread strikes in the public and private sector. At the time she didn’t think much of it, but upon reflection admires the sacrifices her parents made to give her a better life. First in her family to attend university, Susan completed an undergraduate law degree, but upon completion the notion of being a full time lawyer didn’t appeal to her. Deciding to study urban geography, completing a thesis on the migration of Icelanders to Australia, she says it was this rather left field thesis that set her on the path to become the CEO of Mirvac.

“In one of those moments of serendipity I called my university supervisor and said “what does someone like me do for a job?” And he said he’d had a call that very day from Knight Frank, who were looking for a researcher. And I thought, I don’t know the first thing about real estate, but I can analyse, I can write, so why not? And I jumped into real estate and 30 plus years later I’m still in the industry, having worked all around the world for iconic companies. And it was all just that one moment, one phone call to my supervisor launched me off in this direction.”

Striving for a more diverse workplace

“At Mirvac I have tried very hard to ensure we are as gender diverse as possible, and not just gender diversity, gender is just one element of it – we have a full diversity and inclusion effort going on all the time.”

The academic research into diversity is clear: diverse groups make better decisions than homogeneous ones. It’s proven across cultures, across times and across industries. Susan believes that business leaders must be absolutely conscious at all times about diversity within their work force, because if you don’t play close attention, people default to the practice of hiring those most like them. The problem is, that while some elements of diversity are easily marked, diversity of ideas and thought is a lot harder to measure, she says, “it’s not just about having 50% females at the table, it’s a lot deeper than that. You can only measure the things that are obvious, like cultural background or sexual orientation or gender. You can measure those things, and just hope that they all bring some diversity of thought.”

“I’m very, very proud that at Mirvac we have a zero like for like gender pay gap and have maintained that for six years. And it is very hard to maintain if you if you take your eye off for one minute, the gender pay gap, with all the best intentioned in the world comes creeping back into the organisation.”

What keeps Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz up at night?

“The pace of house price growth is simply unsustainable, many multiples of times greater than wage inflation, which is very anaemic. So it is something that does need urgently to be addressed.”

Housing affordability is one of the most important challenges of our time, and Susan believes the problem lies with supply, “We simply don’t do enough dwellings for the growth of household formation in this country. It is a very serious problem and better or worse in different parts of Australia.” When thinking about solutions to the housing crisis and how we might build the cities of the future, Susan has proven that she thinks very much outside the box, conceiving of the idea of “a house with no bills”. “Imagine if you could live in a house and never pay another energy or water bill. Wouldn’t it be transformational for millions of people. What if we could design a different way of building homes so that we were creating no waste?”

A shift towards a more sustainable future

“The business of business is not just business. It is a lot broader than that. People sign up for a noble mission.”

Ten years ago when Mirvac launched the “This Changes Everything” sustainability strategy, with the goal of being net positive in waste water energy by 2030 (without yet having the technology to do so) people thought she was mad. “senior members of industry said you should never set targets that you don’t know how to meet”. Despite the opposition, Susan doggedly pushed on, and fast forward to 2022, Mirvac is now net positive in scope one, and in scope two emissions are 9 years ahead of schedule. She speaks about how rapidly the notion of sustainability is changing at every level of business from the C-suite to the consumer, “our residential customers who ten years ago, if you were talking to them about sustainability upgrades in their home or apartment, they would hear corporate spin and greenwash. And now they buy sustainability upgrades because they have a desire to live in a more impactful way and with a better impact on the planet.”

“Mirvac people generally don’t wake up in the morning and think, I’m going to go generate some earnings per share today. But they do get up in the morning and think about the legacy that they’re going to leave, how they’re going to push forward design and how they’re going to think about how we can design out our waste from our sites. Those are the things that get Mirvac people motivated, and they’re an extremely passionate group of people dedicated to leaving the world a better place than when we found it.”

AUDIO: Listen to the full podcast discussion above

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz was appointed Chief Executive Officer & Managing Director in August 2012 and a Director of Mirvac Board in November 2012. Prior to this Susan was Managing Director at LaSalle Investment Management. Susan has also held senior executive positions at MGPA, Macquarie Group and Lend Lease Corporation, working in Australia, the US and Europe.

Susan is a Director of the Business Council of Australia, member of the NSW Public Service Commission Advisory Board, a member of the INSEAD Global Board, a Trustee of the Australian Museum Foundation, and the immediate past Chair of the Green Building Council of Australia. She holds a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) from the University of Sydney and an MBA (Distinction) from INSEAD (France).

Find out more about other conversations in the Leading with Purpose podcast. Delve into more articles and podcasts like this by signing up to our Professional Ethics Quarterly newsletter.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How ‘ordinary’ people became heroes during the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Accepting sponsorship without selling your soul

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Has passivity contributed to the rise of corrupt lawyers?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership

Political promises and the problem of ‘dirty hands’

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Tim Walker on finding the right leader

Tim Walker on finding the right leader

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 16 NOV 2022

Tim Walker was Former Chief Executive and Artistic Director of the London Philharmonic Orchestra for over twenty years. Balancing its long and distinguished history with a reputation as one of the UK’s most adventurous and forward-looking orchestras, Walker discusses what it takes to grow a profitable business and find the right leader.

Tim Walker was nine when he started learning how to play the piano, and it was only upon attending his very first orchestra, that he realised how much more fun it was to play with other people. So that night, when he arrived home Tim promptly begged his parents to let him start learning the violin too. As a child, Tim was part of the youth orchestra at school, but after a while found it wasn’t really for him… but it was the notion of managing an orchestra, a job which still had that sense of creativity and community which had stolen his heart.

Finding the right leader

“Yes the conductor holds the musicians together but he or she is also using his or her knowledge and intellect to take the written note of the composer and turn it into something that communicates with us in the audience in a very visceral sense, I would say, because it’s not only something that should hit the heart, I think it also needs to hit the head as well.”

While the musicians in the London Philharmonic Orchestra are some of the most talented in the world, it’s the addition of the right conductor that really helps the players shine. The conductor’s role is to unify all the players to one single interpretation of the music, and while the experience of being in a symphony is entirely collaborative, someone needs to ensure everything is flowing seamlessly. But finding the right person for the job hasn’t always been easy. Traditionally in the 19th and 20th centuries, it wasn’t uncommon for a conductor to lead with an iron fist, however as times have changed, so too have conductor styles.

Growing a profitable business

“Interestingly, the London Philharmonic is one of the few orchestras in the world that actually made money from international touring.”

Before Tim joined the London Philharmonic, the company was solely focused on pursuing profit – the board justified each decision by demonstrating how it would contribute to the bottom line. According to Tim, many people make the mistake of thinking just because the individual elements of an enterprise can pay for themselves, then the sum total will be a sustainable enterprise. However, Tim says there are some avenues that need to be pursued not because they generate profit, but rather because doing those things positions the orchestra for the future. As a result, under Tim’s guidance the London Philharmonic recorded all the national anthems for the London Olympics and played at the Queen’s jubilee, not because they were profitable – but because they intrinsically felt like the right thing to do.

Do people still care about orchestras?

“I think, the people do take for granted a lot of the music in their lives as being sort of like wallpaper. I remember when I was talking to somebody who may not know the London Philharmonic, but as soon as I say we recorded all the soundtracks for The Lord of the Rings, suddenly they understand… But they don’t really.”

Over Tim’s twenty year tenure as Artistic Director and Chief Executive of the London Philharmonic, he reveals the hardest part of the job was just keeping everything going. The dilemma is though some would argue that enjoying art is a necessity, music is not the equivalent of food and basic services, so the purchasing of a concert ticket is something that in times of financial stress slows or stops altogether. “You can’t let the institution die on your watch… you’re responsible for 150 full time and 75 part time employees all dependent on ensuring that they can pay their mortgages and put bread on the table.”

Tim highlights that these last few years with COVID-19 have been particularly challenging as audiences are not flocking back as they had hoped.

Tim believes the way to forge a path out of the pandemic is to remind audiences that real people are making this music. The need for live music will never go away, but when you have 200 people whose livelihoods rely on ticket sales, then large orchestras won’t be around for a long time unless we start buying tickets.

“When you care for something, you’ve also got to care for how it’s maintained. So there needs to be a cost to care. And the care for orchestras is in people making the effort to actually go to concerts and appreciate what they have.”

AUDIO: Listen to the full podcast discussion above

Timothy Walker CBE AM Hon RCM was Chief Executive and Artistic Director of the London Philharmonic Orchestra. He was formerly the founder and Chief Executive of World Orchestras and prior General Manager of the Australian Chamber Orchestra. Mr Walker was on the Board of the International Society for the Performing Arts and was Chair of the Association of British Orchestras.

He was an inaugural member of the Australian International Cultural Council, and has served as a director of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Henry Wood Hall Trust and the Rachmaninoff Foundation.

Mr Walker has an honours degree in Arts, a Diploma of Music and a Diploma of Education from the University of Tasmania and a Diploma of Financial Management from the University of New England. He has been a consultant to the Australia Council, Create NSW, Creative Victoria, The Australian Ballet, the Australian Festival of Chamber Music, the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra, the Sydney Conservatorium of Music and the Orcquestra Sinfonica do Estado de Sao Paulo.

Find out more about other conversations in the Leading with Purpose podcast. Delve into more articles and podcasts like this by signing up to our Professional Ethics Quarterly newsletter.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

A foot in the door: The ethics of internships

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethics of workplace drinks, when we’re collectively drinking less

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Roshni Hegerman on creativity and constructing an empowered culture

Roshni Hegerman on creativity and constructing an empowered culture

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 16 NOV 2022

Roshni Hegerman is one of the most awarded strategic thinkers globally. Currently JPAC Market Maker and Experience Director across sustainability and people with Oracle, she discusses creativity, psychological safety and how to construct an empowered culture.

When Roshni was a little girl growing up in India, she didn’t have dreams of being an executive or a director, she had much more humble aspirations to be a social worker. Though her parents didn’t feel it was a career path that could support a family long term, Roshni had her heart set on working with people at a local level.

With this in mind, she studied sociology and psychology in college, but then drifted into journalism and communications, which is where her marketing and communications career really begun. Although, she never did realise the goal of becoming a social worker, the ethos of social work and community has informed all of her decision making she says, “I get realy excited by the power of ideas and how they can connect with people and actually drive either a shift in perception or a shift in behaviour or give people a different lens to kind of view the world through that they wouldn’t have typically viewed it through.”

Be a radiator, not a drain

“I think that the traditional sense of creativity probably isn’t as valued as it could be. I think the use of creativity is to innovate and to do things differently and to think about how you’re going to connect in and change things in a positive way. So from that perspective, I actually think that creative thinking is the only thing that cannot be automated.”

Roshni believes that in the modern workplace, as we shift full speed into the world of automation, creativity and the capacity to think outside the box will actually be the most important skill set for young leaders and changemakers of the future.

One of the things that has stuck with her throughout her professional career is to “be a radiator not a drain”. Rather than be a drain she says, sucking the energy out of the room by sticking to the rules and following traditions, we should be radiators – empowering others, generating ideas, and inspiring new ways of thinking. “I think people are starting to realise that if you’re going to continue to do the same thing and get the same result, and the end and it’s not a positive one, then something has to change.”

Roshni often reflects on her professional practice asking a few key questions:

- How can I use my influence to be more of a radiator?

- Is there a more interesting or different direction we could consider?

- What’s stopping us from being more passionate about a project?

- How can I generate enthusiasm in my team?

- Embrace new and innovative ideas

She suggests that if you can be more of a radiator in your workplace, then people will naturally gravitate towards you, there will be less resistance to your ideas.

People who feel safe have the best ideas

“It’s when you feel like you have to meet a quota and you have to get something done that you tend to revert back to what you know and you don’t feel safe to kind of go out of that box and try something different. It’s when you have an organisation where employees feel safe to kind of give something a go and they’re empowered to be able to do that.”

In order to truly embrace one’s inner radiator, one must feel safe and confident within their team to share their ideas without fear of criticism.

Throughout her career, Roshni has explored the idea of psychological safety in the workplace environment. She suggests as leaders it’s important to create a space of safety in the workplace that allows people to feel more open to being more vulnerable whilst confident enough to have their ideas challenged.

She says, “I think it is very important to create an environment where where you don’t feel threatened by the ideas that you have. There needs to be an environment that allows you to feel at ease with sharing kind of a strong point of view, regardless of which direction you come from.”

Roshi works hard to identity the natural unconscious biases that stop team members from being curious because they believe they already know the answer. She emphasises that it’s important to consciously ask pointed questions and embed curiosity and innovation into every element of organisational structure and process in order to force people to look at things from a different perspective.

“I think it helps create a culture of discovery, empathy, curiosity, and opens up different possibilities of pathways that could be considered. So that’s one of the things I feel really excited by is going, ‘how do we consciously think about these things and what can we do to ask the right questions so that we are having the right conversations so that we can engage people’s curious mind to think about things differently?”

Contributing to a better world

“You need to be willing to have a lived experience. You can’t just say that you care about indigenous people or homeless people. You need to see it from their perspective and understand what they’re going through in order to be able to help in the way that they need you to help them, not how you want to help them.”

Despite diverting from the pathway to a career in social work all those years ago, Roshni maintains that the notion of caring for others and celebrating a sense of community has never left her. It’s important to consider the lived experience of different people, rather than assume what people need, you should strive to constantly be out in different communities and speaking to people directly in order to enrich your own perspective.

Roshni suggests it all comes down to realising that at the end of the day, we are all humans who want to be treated with dignity and respect. She believes in giving those who are underrepresented a voice, and a platform so they can get the help that they need. Her advice for the business leaders of the future is: It’s important to understand that it’s not all about you, that the world is about others, that you occupy it with. So how can you actually help make things better, not just for yourself, but for the people around you?

AUDIO: Listen to the full podcast discussion above

Roshni Hegerman is a force of nature with an unstoppable passion to move businesses and people, creating positive impact and change. Roshni currently is JAPAC Market Maker, Experience Director, with Oracle across Sustainability and People; and is founder of her own strategic creative consultancy, PinchofMasla. Roshni is global citizen unafraid of traversing new and unchartered terrain, in fact she relishes in it – working and thriving in United States, China, India and now Australia – with three beautiful children in tow. Roshni helped launch the iPhone in China, start-up BBH and BBDO in India; grow Coca-Cola’s footprint across Asia.

Roshni is a champion for diversity and inclusion and one of the most awarded strategic creative thinkers globally. She has started her own Women in Leadership networking group – “Ladies that Lunch,” to bring like-minded female leaders together to make meaningful change and collaborates closely with Igniting Change and Campfire X, tiny but meaningful organisations that spark big positive change. Roshni launched “Creating Meaningful Change” while at McCann Australia, a 365-day initiative, that puts conscious inclusion at the centre of the agency’s strategic and creative operating system.

Roshni believes that magic is found in the intersection of humanity, creativity and technology.

Find out more about other conversations in the Leading with Purpose podcast. Delve into more articles and podcasts like this by signing up to our Professional Ethics Quarterly newsletter.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Our economy needs Australians to trust more. How should we do it?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The role of ethics in commercial and professional relationships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to improve your organisation’s ethical decision-making

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 16 NOV 2022

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock are the partners in business and life who strive to build wiser future through culture, space and community. With a unique and innovative approach to business, the pair uncover the realities of being a leader, the importance of failure and fostering a wiser culture.

As a performer, Sylvie Barbier has a real passion for community. Her work is a tenacious exploration of the idea of “art as a conversation” and it’s these thematics of life, discussion, and unity which has equipped her to establish the Life Itself initiative. Together with her partner Rufus, a creative technologist and economist, the two have built a collective based in the half way space between Silicon Valley and the Plum Village in the South of France, which is engaged with creating a weller and wiser world.

On defining leadership

“There is an incredible thirst for leadership, not necessarily leaders – but for leadership.”

The world is in a moment of transition. There is an impending climate crisis, widening inequality as well as a huge amount of disunity and civil unrest, and Rufus believes that we must harness this specific moment in time to interrupt our current archaic notions of what constitutes a leader to craft something new and innovative. He suggests, “we are at a cultural moment where leadership is badly needed, but hugely undermined in part because of these past traumas that we are healing from.”

The reality of being leaders

“There’s always going to be a problem, you’re either not doing enough, or you’re doing too much and being oppressive.”

Having led multiple different initiatives through tech, art and community, both Sylvie and Rufus have learnt a lot about the process of leading. Now that they jointly lead Life Itself, they are encountering a whole new suite of hurdles and challenges as part of running the collaborative residency programs. The programs bring a collection of thinkers, creators, technologists and spiritualists together over an extended period to time to debate and engage with the challenges of the modern world.

Rufus says the hardest part is finding the balance as a leader, “invariably after three months there is some sort of crisis – someone is imposing too many rules, someone has to cook too often – and ultimately you are trying to facilitate the group to engage in a transformation and face these issues, what people must learn is that we need to engage with failure. We have an allergy to failure, but it’s these breakdowns which are the most valuable.”

When leaders fail

Capitalist culture dictates that when a company has some major failing – it is generally the CEO who must hand in their resignation. That the decks must be cleared for fresh blood and new ideas to flush out the old. However Rufus fears we may have gone too far, suggesting that we’ve descended into conducting “ritualised executions” when we decide someone needs to take the blame – just because the leader has left their position doesn’t mean the company will be any better off. Rufus suggests that it’s important to identify the source of the problem, and to think about the duties and responsibilities of leaders more holistically.

In reflecting on their own careers both Rufus and Sylvie acknowledge that they have made some mistakes, and at times mismanaged things. As he continues to learn about leadership, Rufus has let go of trying to achieve everything himself, saying, “leadership is about creating a space in which other people can flourish. I think more and more for myself, based on a huge number of errors, it is the act of creating space versus doing it myself which is central.”

Sylvie agrees, adding her biggest obstacle was she had a tendency to pursue ideals without being grounded in the reality of the world and the reality of who she is. She explores her issues with reconciling these two ideas, “sometimes I felt that the vision I had almost became a burden because it was my responsibility to make it happen. And if it doesn’t happen it’s my fault.”

In the past she was characterised by the ruthless pursuit of intangible goals, but found she was ultimately dissatisfied with this way of leading because when she achieved these goals she would immediately need to move on to something else and it felt particularly dissatisfying.

She concludes, “the world is already perfect the way it is, it doesn’t need to be any different than the way it is right now. And in a moment of radical acceptance, I realised I was already in paradise.”

AUDIO: Listen to the full podcast discussion above

Sylvie ‘Shiwei’ Barbier is a French-Taiwanese performance artist, entrepreneur and educator. Her work synthesizes Eastern and Western philosophies and aesthetics. She co-founded Life Itself to build a wiser future through culture, space and community. Her performance art pieces are contemporary rituals, where the audience is invited to take an active and interactive role. She uses language such as Koans as a bridge for the mind into the spiritual realm, by pushing us beyond the bounds of the intellect into a space of greater wholeness and connection.

Rufus Pollock is a technologist, entrepreneur, writer and long-term zen practitioner. He is the founder of Open Knowledge, an award-winning international digital non-profit. Formerly a Shuttleworth Fellow, Ashoka Fellow and a Mead Fellow in Economics at Cambridge University. His book the Open Revolution sets out a vision for a open, free and free information economy and has been translated into multiple languages. As a co-founder of Life Itself he brings curiosity and rigour to ongoing inquiry into how we can create a radically wiser, weller world for all.

Find out more about other conversations in the Leading with Purpose podcast. Delve into more articles and podcasts like this by signing up to our Professional Ethics Quarterly newsletter.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Our economy needs Australians to trust more. How should we do it?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why do good people do bad things?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + Analysis

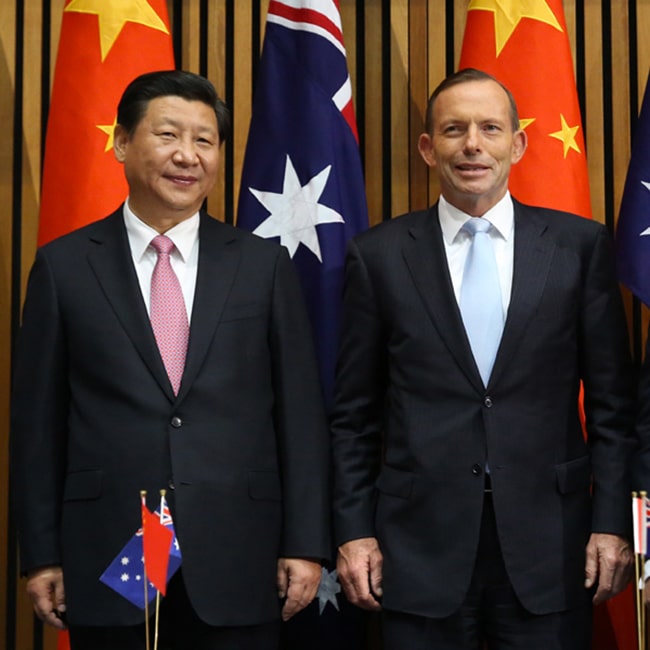

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Sportswashing: How money and politics are corrupting sport

Sportswashing: How money and politics are corrupting sport

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr Tim Dean 9 NOV 2022

Many believe that sport transcends politics. But it can also be used as a political tool to distract attention from human rights abuses, making sportspeople and fans complicit.

Legions of football fans with faces daubed in their national colours fill the spotless new stadium and explode into a roar when their team lands the ball in the back of net at the FIFA World Cup 2022 in Qatar.

From the promotional video alone, the scene seems to exemplify what people love about big sporting events: the emotional highs and lows; the vibrant carnivale atmosphere; the fierce competitive spirit; the skill of the athletes.

But to the millions of migrant workers in Qatar, many of whom helped build the very stadiums that are to host the games, the World Cup likely means something very different.

Qatar has long been criticised for the kafala system of sponsorship-based employment for foreign workers, which has led to underpayment, wage theft and unsafe working conditions, leaving workers powerless to change their employment circumstances. Qatar also has a history of women’s oppression, with women requiring permission from a male guardian to exercise many basic rights, such as pursuing higher education, working in certain jobs or traveling abroad. LGBTI people have also been subject to discrimination and abuse in the country, even on the lead-up to the World Cup.

So it is no accident Qatar is spending billions to host the World Cup, with estimates suggesting the government has pumped over $US 220 billion into the event – more than fifty times what Germany spent in 2006 when it hosted.

This is ‘sportswashing.’ The Qatari government is hoping it can appropriate the positive associations fans have with football to elevate its own status on the international stage and distract from its ongoing human rights violations.

And Qatar is not alone in the practice: Saudi Arabia, another nation with a problematic human rights record, has spent over $US 2 billion on its LIV Tour for golf; and China, criticised for its ongoing persecution and internment of its Uyghur minority, spent billions hosting the 2022 Winter Olympic Games.

But what’s so bad about a country with a troubling human rights record supporting or hosting an unrelated sporting competition? Does watching or travelling to that country to attend the competition make spectators complicit in human rights abuses? And shouldn’t sport be kept separate from politics? To answer these questions, we first need to be clear about what sportswashing is.

What is sportwashing?

Sportswashing refers to states – sometimes individiuals or corporations – that seek to use sport to bolster their image by distracting from their wrongdoing. It’s typically not just a matter of hosting games or supporting a national team but rather pumping money into sport specifically to change people’s attitudes about them.

Why sport?

Sport is more than just entertainment. It exemplifies what many people believe to be noble or aspirational virtues: discipline, hard work, individual excellence, teamwork. For spectators, sport generates intense feelings of belonging and a shared identity that verges on the sacred; a win for one’s team elevates oneself and one’s whole community. Sport also reaches a wide audience, including people who may not actively follow politics or world affairs.

So if a regime wants to bolster its reputation around the world, it’s hard to beat tapping into the positive associations people have with sport, especially high profile sports like golf, football or the Olympics. And all you need to do it is enough money. But what does all this money really achieve?

First impressions

What springs to mind when you think of Qatar? For many people whatever it is will be informed by what’s in the media. And if the media has been focusing on Qatar’s human rights violations, it’s these that can define their impression of the country.

This is why nations like Qatar are so keen to offer you new impressions. One function of sportswashing is to saturate the news – and internet search results – with topics other than human rights. If people know little about Qatar, and the World Cup pushes its human rights violations to the second page of Google’s search results, then fewer people will be made aware of them.

There’s another upshot of sportswashing: given many people have powerful feelings about sport, if the majority of the news they hear about Qatar is connected to their beloved game, then their feelings for sport can bleed over into their impression of the country.

Once that positive connection with sport is established, it can come to clash with negative associations they have about human rights violations, causing cognitive dissonance, which describes a tension between two opposing ideas. Most people tend to dislike the feeling of dissonance and will seek to eliminate it, often by ejecting one of the dissonant thoughts. Sportswashing nations hope that the ejected thought is the one about human rights rather than sport.

This is where sportswashing becomes ethically problematic. To the degree that it distracts from wrongdoing, such as human rights violations, it can contribute to the perpetuation of that wrongdoing. Countries are often motivated to enact reforms when they experience pressure from other states, especially large democractic states that are reacting to internal public pressure. If the population is distracted by sport, then public pressure can wane.

Just not cricket

Sportswashing is insidious, as it co-opts something that is otherwise benign and makes those who innocently endorse it complicit in achieving a political end.

But just because someone was not aware of, or chose to ignore, the political dimension of the sporting event, that doesn’t mean they are absolved of responsibility. Sadly, sportswashing makes anyone involved in it complicit to some degree.

If we believe that our ethical obligations extend to those parts of the world that we affect through our actions, then we must consider how our spectating or participating in a sportswashing event might contribute to perpetuating human rights abuses. If we are paying to attend a sportswashed event, we are contributing financially to enabling that event to take place, and through our attendance, we are normalising that activity for others.

There is an even greater ethical weight placed on the shoulders of sportspeople, who are often viewed as role models and whose behaviour can be seen to normalise certain values. This is why we place such emphasis on sportspeople behaving responsibly on and off the field, such as in nightclubs or in their private relationships.

If a sportsperson accepts money to participate in a sportswashed event, that sets a standard for others. And if they are aware of the ethically problematic nature of their hosts, then this opens them to a charge of hypocrisy, as in the case of Phil Mickelson, one of the world’s top golfers, who accepted $US 200 million to join the LIV Tour despite admitting he was aware of Saudi Arabia’s “horrible record on human rights”.

Washing sport

However, there are ways of pushing back against sportswashing. The first is to refuse to support it financially, such as by not buying tickets to the events or subscriptions to the coverage in the media. For some, this will mean missing out on watching a sacred sporting event, and it’s important not to understate how big a cost that might be for them.

However, if they choose to watch, they can consider how to reduce or nullify the impact of the sportswashing. That could involve informing themselves and others about the true state of affairs, reducing the informational distortion caused by sportswashing. In fact, there is evidence that Qatar’s World Cup sportswashing gambit may be backfiring by drawing attention to the very human rights issues it hopes to distract from.

Sportspeople have an even greater responsibility but also a greater potential impact for good. Some have refused to participate in sportswashed events, such as golfer Tiger Woods, who reportedly turned down an offer in excess of $US 700 million to join the Saudi-backed LIV Tour.

In some cases, participating in a sportswashed event can be offset if the individuals work to counter the sportswashed narrative, as in the case of the Australian Soccerros, who released a protest video about human rights in Qatar. While they are playing in the World Cup, they have used their platform to support migrant workers and the decriminalisation of same-sex relationships in Qatar. Football Australia also released a similar written statement. Arguably, more Australians now know about Qatar’s human rights record than if the state had never been chosen to host the World Cup.

When states are involved in funding sport, then sport can no longer be said to be removed from politics. Through sportswashing it becomes a political tool. If we want to maintain sport as a pure and sacred pursuit, then we must consider how we choose to engage with it and how we might avoid or counteract the power of sportswashing to distract or normalise wrongdoing.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

When are secrets best kept?

Throughout the ages, people subject to the torments of even the most oppressive regimes have found solace in the fact that even when their bodies are controlled, their minds can remain free.

People have the capacity to hold information and beliefs that cannot be discerned by any mind other than their own. Of course, in many cases (but not all) the mental reserves needed to preserve a secret can be destroyed by those who employ torture. However, only the most vicious and desperate resort to such despicable acts – and even then, they can never be sure that what they are told is actually true. But that is another topic for another time.

For now, I want to highlight the remarkable strength of secrets – a strength conferred by their retention in regions of the human mind that are inaccessible to others.

The fact that we cannot ‘read minds’ allows each of us a particular kind of freedom.

However, it would be a lonely existence if we were not also endowed with the capacity to share our thinking with others through all of the forms of communication available to us – physical, verbal, literal, and symbolic. So, for the most part, we liberally share our thoughts, feelings and beliefs in word and deed – while retaining some things entirely to ourselves.

While this is the context in which secrets exist, it’s important to note the distinction between ‘having’ and ‘holding’ secrets. In the first case, secrets can be our own – something that we know we choose not to disclose to others. In the second case, secrets can ‘belong’ to someone else who has shared them with us – on the condition we preserve the secrecy of what has been disclosed.

There are many examples of both kinds of secret. For example, a person may have suffered some kind of sexual assault in their youth but, for a range of reasons, may never disclose this to another soul. It will be their secret – and they will take it to the grave. Alternatively, if they share this secret with another person – on the condition that no other person ever know this truth – then the latter person will have agreed to hold the secret for as long as required to do so by the person whose secret has been shared with them.

It’s easy to see in this example just some of the problems with secrets. Let’s suppose that the person who abused the youth is still at large – possibly still offending. Does the person who ‘holds’ the secret have an obligation to prevent harm that is greater than the obligation to protect their friend’s secret? One might hope that the friend would agree to reveal the identity of the malefactor. However, what if they refuse? What if a person at risk of abuse asks a direct question about the person whom you know to be a threat to them? Are you required to lie or to dissemble in order to keep the secret?

Of course, the ability to have and to hold secrets can also enable great evil. For example, some secrets can obscure damaging, false beliefs that – even if sincerely held – present grave risks to individuals or whole communities. We can see such ‘secret knowledge’ at work in certain cults and conspiracy theories. Because secret, these sometimes deadly false beliefs cannot be challenged or amended by exposure to the ‘sunlight’ of open enquiry and debate. Deadly secrets can fester and grow in the dark to the point where they can poison whole sections of the community.

What’s more, perverse forms of secrecy can be employed by powerful interests as a tool to control others. Whole regimes have been propped up by ‘secret police’, the cloaking of wrongdoing behind the veil of ‘official secrets’, and so on.

The ethics of secrets have a practical bearing on matters affecting individuals, groups and whole societies. Core questions include: Is there a distinction between a ‘confidence’ and a ‘secret’? Do certain people have a right to know information that others wish to keep secret? Are we ever obliged to disclose another person’s secret? What, if anything, is a ‘legitimate secret’? Who decides questions of legitimacy? How does one balance the interests of individuals and society?

Join Dr Simon Longstaff on Thur 23 Nov as he lifts the lid on secrets and their role in living an ethical life. The Ethics of Secrets tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

This is what comes after climate grief

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Particularism

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 4 NOV 2022

In 2021, the star of the US iteration of The Bachelorette, Katie Thurston, made international news off the back of one thirty second clip. In it, Thurston, all smiles and fey giggles, announced that she was forbidding the male contestants searching for her endless love from masturbating.

“I kind of had this idea I thought would be fun, where the guys in the house all have to agree to withhold their self-care as long as possible, if you know what I mean,” Thurston told the show’s two hosts, to a great deal of laughter and blushing. What was she was doing was what Bachelorette stars – and indeed many of those who feature in that brand of modern reality television focused on love and sex – have done for years.

Namely, she was upholding the show’s characteristic, and very strange, mix of euphemism and the explicit stating of norms that are so well-trodden in the culture that they’re not even acknowledged as norms at all.

Indeed, the most surprising thing about the clip was that it generated chatter, from both mainstream outlets and social media, in the first place. The Bachelorette’s habit of not so much ignoring the elephant in the corner, but ignoring the corner, and the walls connected to the corner, and perhaps even the entire room, has been part of its fabric from its very conception.

This is a show ostensibly about desire and love – which is a way of saying that it is about different states that circle around, and often lead to or follow from, sex – that shirks desperately away from most of the ways that we understand these things.

All we get on the desire front is a lot of people who pay a certain kind of attention to their bodies, occasionally – extremely occasionally – kissing one another. And all we get on the love front is a lot of talk about forever and eternity, along with roses, champagne flutes, and tears. Sex, meanwhile, lies far beyond the show’s window of acceptable or even conceivable behaviours. It’s there but it’s not there, a part of the very foundation of the show that’s still so taboo that if someone dares speak it aloud, as Thurston did, they’ll be the odd one.

This backlash to a bizarre norm constructed and maintained by the cameras was taken to an extreme in the case of Abbie Chatfield, a contestant on the Australian version of the show. For daring to tell Bachelor Matt Agnew that she “really wanted” to have sex with him, and admitting that she was “really horny”, Chatfield drew ire from not only the usual anti-sex bores, but from the so-called “sensible mainstream centre.” She was called a slut; her behaviour designated outrageous.

Such a backlash wasn’t just a policing of women’s bodies, though it was that. It was also a policing of the very standards of desire, part of a long attempt to prettify and clean up matters of sex and love, into “good” (read: socially acceptable) talk about these matters, and “bad” (read: unhinged, dangerous, impolite) talk about them.

In a society with a healthier understanding of sexuality, Chatfield wouldn’t be the deviation. The whole strange apparatus around her would be.

Whose Normal?

What makes The Bachelor and The Bachelorette such fascinating, internally frustrated objects is that their restating of the normal reaches such a volume, and resists so many specifics, that it reveals how utterly not-normal, arbitrary, and ill-defined most normal stuff is.

For instance, there is much talk in The Bachelor and The Bachelorette about romantic “compatibility”, a bizarre standard frequently talked about in the culture without ever being actually, you know, talked about. On this compatibility view of love, the pursuit of a significant other is a process of finding someone to fit into your life, as though you have one goal for how you want to be, and only one person who can help you achieve that. It’s that popular meme of the human being as an incomplete jigsaw puzzle, picking up pieces, one by one, and trying to slot them in.

What The Bachelor and The Bachelorette usually reveal, however, is that actually working out who is “the one” for you is much more difficult than the show’s own repeated emphasis on compatibility implies.

The stars of these shows frequently love and desire multiple people at the same time – the entire dramatic tension of the show comes from their final selection of a partner being surprising and tense.

If this compatibility stuff was as simple as it often described – or even clearly explicated – then we’d know after thirty seconds spent between potential two life partners that they’d end up together. There’d be no hook; no narrative arc. Eyes would lock, hearts would flutter, and the puzzle piece would just slot in.

In actuality, on both of these shows, the decision to pick one person over another frequently feels deeply random, and the always vague star usually has to blur their explanations even further into the abstract to justify why they want to be with him, and not with him, or with him.

The Bachelor and The Bachelorette are supposedly triumphant testaments to monogamy – almost all seasons of the show, except the one starring Nick Cummins, the Honey Badger, end with two and only two people walking off together.

But actually, in their typically confused way, they also end up explicating the benefits of polyamory. Often, the stars of these shows have a lot of fun, and derive a lot of pleasure and purpose from being intimate and romantic with a number of people at the same time. When it comes time to choose their “one”, it is frequently with tears – on a number of occasions, the stars have said, in so many words, “why not both?”

Get Those Freaks Away From Me

And why not both? Or more than both? The season of The Bachelor where no contestant is eliminated, everyone goes on dates together, and they all end up having sex and falling in love with one another, is no stranger than the season where only two walk into the sunset.

Monogamy is a norm, which is to say that it is an utterly arbitrary thing spoken loudly enough to seem iron-wrought. Norms are forceful; they tell us that things are the way they are, and could be no other way. In fact, they are so forceful that they have to state not only their own definitional boundaries, but also the boundaries of the thing that they are not – not just pushing the alien away, but the very act of designating things alien in the first place.

It was the philosopher Michel Foucault who noted this habit of branding certain objects, habits, or people as “other” in order to better understand and designate the normal. The Bachelor and The Bachelorette do this both frequently and implicitly, never drawing attention to the hand that is forever sketching abrupt and hurried lines in the sand.

Just consider the things that would be astonishing in the shows’ worlds, without even having to be taboo. For instance, imagine a star being perfectly happy committing to none of the contestants, and merely having sex with a few of them, one after the other. Or a star choosing a contestant but, rather than speaking of their flawless connection together, emphasising “mere” fun, or “mere” pleasure.

None of the preceding critique of these shows is a call to eradicate romantic and sexual norms altogether, if such an definitional cleansing were even possible. We have to make decisions about how we navigate the world together, and norms become a shorthand way of describing these decisions. What we should remember throughout, however, is that we are free to change this shorthand up whenever we like. And more than that, we should resist, wherever possible, the urge to create the other.

After all, if The Bachelor and The Bachelorette tell us anything, it’s that those regular folks are the real sickos.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When identity is used as a weapon

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is modesty an outdated virtue?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Appreciation or appropriation? The impacts of stealing culture

Appreciation or appropriation? The impacts of stealing culture

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Paul-Mikhail Catapang Podosky 31 OCT 2022

It’s Halloween season. Perhaps your child has just watched Encanto and they’ve asked to wear Bruno’s ruana as a costume for trick-or-treating. Deciding how to answer requires traversing murky moral territory and unpacking the term ‘cultural appropriation.’

Recently, there has been a serious shift in thinking about what makes for an ethically appropriate costume, attracting considerable media attention from the likes of The New York Times, The Atlantic, and The Conversation. The primary concern is that when white people dress-up in outfits removed from their original cultural context, this constitutes cultural appropriation. But what exactly makes cultural appropriation ethically problematic? And does this mean that certain Halloween costumes, such as Bruno’s ruana, are off-the-table for white people?

At the Festival of Dangerous Ideas in September 2022, the session ‘Stealing Culture’ questioned whether cultural appropriation is an important ethical concept at all. This sounds like a strange enquiry since the answer seems like a clear ‘yes’. However, Luara Ferracioli, a philosopher at the University of Sydney, gave a surprising response: while charges of appropriation target serious moral wrongs, “we don’t need an umbrella term like ‘cultural appropriation’”. It is merely a catch-all phrase for a range of problematic behaviour that doesn’t capture anything morally distinctive.

When there is something genuinely wrong that a charge of cultural appropriation aims to pick out, Luara argues that we would do better simply to help ourselves to the variety of familiar and more precise ethical concepts already at our disposal, such as exploitation, misrepresentation, and causing offense. This results in a striking conclusion: the term ‘cultural appropriation’ is redundant, so we should eliminate it from our moral vocabulary.

I disagree with Luara. The concept of cultural appropriation is an important resource for moral thinking because it allows us to identify a very specific way that marginalised cultures are subjected to erosion by outsiders and subsumed within dominant ways of life. And with Halloween just around the corner, we should be especially worried about the appropriation of culturally significant outfits.

So what is cultural appropriation?

Starting with the second part of the term, appropriation involves taking something for one’s own use, often without permission. Cultural appropriation occurs when what is taken belongs to a culture that is not one’s own. A distinctive watermark of our time is the salience of this phenomenon in the public’s moral imagination, tending to focus on situations where a cultural material is taken out of context and worn solely for looks.

Overwhelmingly, the moral concern of appropriation has been directed at the practices of white people, such as Justin Bieber’s wearing of dreadlocks, Timna Woollard’s mimicking of Indigenous art, and the use of tribal symbolism by the Washington ‘Redskins’. As we approach Halloween, costumes are becoming a primary source of worry. Animated films such as Moana, Coco, Aladdin, and Mulan are extremely popular with children, and a spring of inspiration for potential ‘costumes’—such as the ruana worn by Bruno in Encanto. The main characters of these films are not white. And the films track the stories of protagonists engaging with distinctive forms of life, and the particular problems that emerge within them, may be quite unfamiliar to the typical white person.

When a white child wears, say, a ruana to resemble Bruno, what causes uneasiness is not just that it might be offensive. Rather, what makes it troubling is its connection to the historical oppression responsible for existing systems of unjust hierarchy, such as egregious histories of settler colonialism, on-going practices of ethnic discrimination, and growing material inequalities that track skin-colour.

What makes cultural appropriation ethically problematic?

Cultural appropriation is ethically problematic because of its unique way of exacerbating conditions of unjust inequality. Because of this, we must be extremely judicious about our choice of Halloween costume.

When a white person wears a ruana as a costume, each instance might not appear to require much moral attention. But when these acts are repeated over time, what emerges is something dangerous. A causal feedback loop between the taker and the cultural material results in changing the material’s significance. For example, the ruana, which is native to Colombia, and initially made by its indigenous and Mestizo people, risks transformation from being a garment contained within Colombian culture and history, to a ‘costume’ available for white people to imbue with new cultural meaning.

This is what make cultural appropriation a unique moral issue. Because cultural materials partly define the identity of a cultural group, such as the kippah for Jewish people or the kimono in Japanese culture, when these materials are appropriated by another group and imbued with new cultural meaning, the boundaries between the groups start to blur.

It becomes difficult to locate the fault lines between the culture that has taken and the culture that has been taken from. Continuing with our example, if the ruana becomes forcibly transfigured to meet the costume-related desires of white society, this will result in the ruana becoming a ‘shared’ cultural material; something that neither belongs to just one culture, but a common artefact that partly defines both.

Perhaps this doesn’t seem like such a bad thing. Cultural exchange can be mutually beneficial, after all. But in the context of historical oppression, cultural appropriation is morally alarming. Consider Colombia. It was colonised by the Spanish in the 1500s, and with this came violence, genocide, disease and environmental destruction. The impacts of this history are still felt today, with socio-economic disparities, compromised life opportunities, insecurity and violence, political instability, mass displacement, and a struggle for the recognition and respect of indigenous peoples.

Being sensitive to the history of oppression and its present impact means we must be morally on-guard against appropriation.

Colonisation in particular requires a special kind of wariness. Given how cultural appropriation can erode and obscure cultural identity boundaries, it is instrumental in furthering colonising projects. Specifically, the effect of cultural appropriation on cultures is asymmetrical: marginalised cultures become ‘subsumed’ within dominant ways of life. For example, the ruana, if continuously used by white people, could become a shared cultural artefact dominantly understood as a colourful ‘poncho’ to be worn at Halloween, rather than something at the heart of Colombian cultural practices.

This unique way of exacerbating conditions of inequality means that cultural appropriation is a moral concept worth holding onto. Contrary to Luara’s scepticism, there isn’t anything else in our bag of moral terminology up to the task of capturing the distinctive wrong that historically marginalised cultures face when they are subjected to changes from the outside.

Appreciate, but not appropriate

Does this mean we can never engage with unfamiliar cultural materials? In order to answer, we must consider the distinction between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation. Where the former erodes cultural boundaries, the latter respects them. But appreciating culture takes considered effort.

Firstly, it’s important to learn the cultural significance of a material and whether its use is a contribution to an existing cultural practice, rather than playing a role in establishing a new one. Secondly, we should understand whether others will interpret their use of a cultural material in the same way as them. For example, when one wears a ruana to a traditional Colombian festival, one contributes to existing cultural practices, and one can be seen by others to be participating in this way. This keeps the ruana within its cultural domain rather than giving it new meaning that overshadows it original significance.

When it comes to a child requesting to wear a culturally significant outfit for Halloween we need to be mindful of the context in which it is worn, and if it’s taken outside of its cultural context, then consider whether it could be a case of cultural appropriation.

And remember that there are kinds of costume that do not risk diluting other cultures or reinforcing historical injustices. By practising cultural awareness, we can enjoy events like Halloween and do so in a way that respects and appreciates other cultures.

Visit FODI on demand for more provocative ideas, articles, podcasts and videos.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

From capitalism to communism, explained

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

LGBT…Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Values

BY Paul-Mikhail Catapang Podosky

Paul-Mikhail Catapang Podosky (he/they) is a Filipinx philosopher, passionate about all things related to human drama. His research investigates the limits of conceptual engineering as a tool for promoting social justice, and in the critical philosophy of race and gender, he explores the politics of classification, with a specific focus on mixed-race identity. Previously, he was Global Perspectives on Society Fellow at New York University, and he is presently Lecturer in Philosophy at Macquarie University.

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 28 OCT 2022

More sporting and arts bodies are thinking hard about whom they’re willing to accept funding or sponsorship deals from. But how are they to weigh the competing interests of their organisations, players and artists, and the general public?

When First Nations netballer Donnell Wallam spoke out to seek an exemption from wearing the logo of major sponsor, Hancock Prospecting, she sparked a national conversation around the role of sponsorship in sport, and what voice players ought to have in choosing which sponsors they accept and which logos they wear on their jerseys.

In the case of Wallam, Netball Australia had just signed at $15 million sponsorship deal with Hancock Prospecting, run by Gina Reinhart, the daughter of the founder, Lang Hancock. This was seen by Netball Australia as a much-needed injection of funding to compensate for the multi-million dollar debt the sport’s governing body had accrued during years of COVID-19 lockdowns and travel restrictions.

But Wallam saw something else. Front of mind for her were comments made by Lang Hancock in a 1984 documentary where he advocated that any Indigenous peoples who had not been assimilated ought to be rounded up and sterilised.

After a weeks of debate and negotiation, Hancock Prospecting withdrew from the sponsorship deal, offering short-term funding until the sporting body could find a new sponsor. In a parting shot, the company released a statement saying “it is unnecessary for sports organisations to be used as the vehicle for social or political causes” and that “there are more targeted and genuine ways to progress social or political causes without virtue signalling or for self-publicity”.

However, there is good reason to believe that Wallam and Netball Australia’s actions were more than a ‘virtue signalling’ exercise, but rather part of an increasing trend of sporting bodies and other organisations thinking carefully about whom they accept funding from and which industries they are willing to be associated with.

In recent times, a group of high-profile Freemantle Dockers players and supporters have called for the club to drop oil and gas company Woodside Energy over concerns about climate change. Australian test cricket captain, Pat Cummins, has also declined to appear in any promotional material for Cricket Australia sponsor Alinta Energy, a move backed by former Wallabies captain, and ACT senator, David Pockock.

Arts organisations have been wrestling with similar questions for some years, prompted by incidents such as the Sydney Biennale in 2014 severing its relationship with Transfield, which operated immigration detention centres, after an artist boycott, and the Sydney Festival in 2022 deciding to suspend all funding agreements with foreign governments after an artist boycott due to a sponsorship agreement with the Israeli embassy.

So how should businesses and other organisations, including sporting and arts bodies, decide whom to accept money from? How should they weigh the interests of players, artists, supporters and the wider public with their financial needs and their organisational values? How do they avoid making rash decisions that themselves trigger a backlash?

How to decide

These are difficult questions to answer, which is why The Ethics Centre has developed a specialised decision-making approach, Decision Lab, to help businesses and other organisations navigate difficult ethical terrain and make better decisions.

The Decision Lab process is designed to bring implicit thinking and buried assumptions to the surface so they can be discussed and debated in the open, providing tools to evaluate decisions before they are committed to so that key considerations are not overlooked.

The foundation of the Decision Lab is gaining a deeper understanding of the organisation’s foundational purpose for being, its values and the principles that guide it. These ought to be the starting point of any big decision, but published mission statements and codes of ethics are often overwhelmed in practice by the organisation’s Shadow Values, which are woven into the unspoken culture. The Decision Lab seeks to bring these values to the surface so they can scrutinised, revised and applied as needed.

The Decision Lab also employs a decision-making model that follows a step-by-step process that covers all the elements necessary to make a comprehensive and defendable decision. This includes factoring in what is known, unknown and assumed, such as how the funding might positively or negatively impact the community, or how it might help to promote a cause that the organisation doesn’t believe in.

It also considers the impacts of a decision on all stakeholders, including the wider community and future generations, and not just those who are closely connected to the decision.

The process also teases out the specific clash of values and principles around a particular decision, which is useful because many dilemmas follow a similar form. So if an organisation has an existing solution to one problem, it might find it already has the necessary reasoning and jusification to respond to another situation that follows the same pattern.

Finally, the Decision Lab applies a ‘no regrets’ test to ensure that nothing has been overlooked. This helps avoid situations where a decision is made yet it runs into problems that could have been forseen if the organisation had applied a more rigorous decision making process, such as a counter-backlash by other segments of their community.

The Decision Lab supports the executive team to align their decisions with the organisation’s ethics framework and helps to communicate with all the key stakeholders the rationale for decisions. By applying a more rigorous decision-making process, an organisation is better able to balance competing interests, resulting in more ethical decisions aligned to its purpose, values and principles that will hold up in the face of scrutiny.

The Ethics Centre is a thought leader in assessing organisational cultural health and building leadership capability to make good ethical decisions. To find our more about Decision Lab, or arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Image by Nigel Owen / Action Plus Sports Images / Alamy

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Moral injury is a new test for employers

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Between frenzy and despair: navigating our new political era

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Should corporate Australia have a voice?

Should corporate Australia have a voice?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Alliance Emma Elsworthy 24 OCT 2022

The Albanese government is preparing for the fight of its life to convince Australians an Indigenous advisory body, known as the Voice to Parliament, should receive a simple “yes” in a referendum due to take place in October 2023. But whether the Australian business community should abstain or pick a side in the campaign is a little more complex.

Some business leaders have already openly backed the Voice. CSL’s Brian McNamee called embedding Indigenous people into our Constitution for the first time nothing less than a “greater need” for the nation. Lendlease’s CEO Tony Lombardo said his company was “right behind” the Uluru Statement from the Heart and had urged his staff to think deeply about the constitutional amendment and the benefits for our First Nations peoples and the broader Australian community.

But business taking a public stance wasn’t always so. In decades prior, corporations strained to stay impartial by not weighing in on heavily politicised or social issues, seeing it as a polarising death wish amid the cohort of its customers who may err to the other side (though big political donations were a telling exception to this unofficial rule).

But the rise of social media in the era where progressive politics has assembled earth-shaking movements like Black Lives Matter, #MeToo and the fight to stop climate change has created a corporate environment where it’s not only expected companies to weigh in on big-ticket items – it’s great for business if they do.

Nearly 80% of Australians believe big brands should use their power to make an impact for real-world change on social and workplace inequality, according to research conducted by Nine and cultural insights agency FiftyFive5 – and it can turn into big bucks for corporations.

When beloved ice cream brand Ben & Jerry’s, which accounts for 3% of the worldwide market, announced in 2021 that it was stopping sales “in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT)” because it was “inconsistent with our values”, Ben & Jerry’s sales saw a 9% yearly growth (though frustrated parent company Unilever denied the two were linked).

And it seems the Albanese government is all but expecting corporate Australia to take a stance on the Voice one way or another. In 2019, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese declared to the Business Council of Australia that business should feel free to speak out on social issues that align with their values.

“The most successful businesses operate in ways that reflect the values of their employees and their customers,” the then-opposition leader said.

“You are not just takers of profit – you see yourselves as part of the community.”

Albanese’s comments followed a heated speech from Scott Morrison’s assistant minister Ben Morton declaring chief executives “too often succumb or pander to similar pressures from noisy, highly orchestrated campaigns of elites typified by groups such as GetUp or activist shareholders”, foreshadowing the Teal uprising in the May federal election.

But corporate activism doesn’t have to mean go woke or go broke – as long as a company is seen as being consistent with its long-held values, a customer base or wider community will accept a more conservative position on a social or political issue too, as Daniel Korschun and N. Craig Smith write for the Harvard Business Review.

“People are surprisingly accepting of a company’s political viewpoints as long as they believe that it is being forthright,” the pair write.

“When a company makes sudden changes to its procedures or identity, it can raise red flags, especially with consumers for whom reliability is essential.”

To this end, a corporate in Australia that openly supports the “Yes” campaign for the Voice to Parliament may first quietly seek to understand the company’s own history with Indigenous Australia to avoid damning accusations of “woke washing” from the public.

Director of The Ethics Alliance, Cris Parker suggests leaders seek the answer to questions like: how many First Nations people are employed at the organisation, and is it far less than the 3% in wider society? Has the organisation proactively supported these staff, providing a culturally sensitive environment that recognises Indigenous rights?

“Basically, are you living the values of whatever social issue internally that you are considering speaking out about publicly?” Parker says.

For instance, when Nike released its “Dream Crazy” campaign to support Colin Kaepernick taking a knee during the American national anthem to protest police brutality, some were quick to point out Nike’s own reputation for using the sweatshop labour of people of colour abroad in countries like China.

Further, hot-button issues can polarise people not only within the customer base but within the work culture. Parker suggests that a corporation may add the most value during this time by fostering an environment where people can respectfully share ideas and reflect on issues together.

“Perhaps standing on a pedestal isn’t the approach which will have the greatest impact. Perhaps the impact of corporations is to demonstrate the ability to create spaces where there can be civil and informed debate – not to provide the decision or choice but to impartially inform employees and encourage intelligent enquiry,” Parker continues.

“When organisations shift to a specific advocacy position, particularly if it’s about members of our community, they risk disempowering those members and really we should be supporting self-determination.”