Your kid’s favourite ethics podcast drops a new season to start 2021 right

Your kid’s favourite ethics podcast drops a new season to start 2021 right

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Matthew Beard 21 JAN 2021

If your kids are anything like mine, the holidays have officially hit the ‘we’ve dragged on too long’ stage.

Your children drift like bored zombies from room to room, looking for another screen or toy to give them a fresh dopamine hit.

They don’t want to admit it, but they’re ready for school to go back. You’re all hanging out for that first day.

Good news! You can stop waiting. You don’t need to let the boredom drag on until school goes back. You can get your child’s – and your own – synapses firing right now and sharpen your ethical sensibilities in the process, thanks to a new season of Short & Curly, the award-winning, chart-topping ethics podcast produced by the ABC, and featuring Ethics Centre fellow Matt Beard (that’s me).

The podcast, now in its 13th season, is a playful, light-hearted and engaging exploration of ethics. It’s driven by the central belief that ethics is a team sport, and each twenty-minute episode features a number of ‘thinking questions’ where listeners are encouraged to pause the show to talk about some big ideas with the people around them. This isn’t just a podcast for your kids – it’s one for you as well!

The latest season comprises of five episodes on a wide range of topics and settings, including:

- A class being held back by an angry teacher hell-bent on finding out who stole her cookies, prompting us to ask: is collective punishment is ever justified?

- An impromptu beach trip is cancelled thanks to a fear of sharks – should we cull sharks to make sure that swimmers can enjoy the ocean free of fear?

- Frozen and The Avengers turn a casual trivia night into a discussion of one of the oldest questions in ethics: do the ends ever justify the means?

- As the Amazon – the lungs of the world – continues to burn, putting all of us an increased threat to climate change, we go on a tour of the Amazon and ask who owns the rainforest, and who should decide how to treat it?

- We take a tour of the wonderful world of robots! Looking at the various ways that robots could replace humans in the future, and ask whether or not they should.

One of the pitfalls of parenting is making ‘doing the right thing’ seem like the opponent of fun. If our kids see ethics as more closely connected to discipline than it is to curiosity, we risk setting them up for a mode of thinking that doesn’t serve them or the world they’ll help build.

Whether or not you’re tuning into the podcast, try to make imagination, creativity and curiosity your default settings when discussing ethics with your kids. Do your best not to close off discussion by giving your ‘authoritative’ view. Discussions don’t work well under hierarchies. And if you need some more pointers, check out our handy guide to talking to kids about ethics here.

Oh, and there may be some extremely bad rapping in one of the episodes. I won’t tell you which one, but be on the lookout!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

WATCH

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Is your workplace turning into a cult?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

No justice, no peace in healing Trump's America

No justice, no peace in healing Trump’s America

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 21 JAN 2021

What fate should be reserved for Donald Trump following his impeachment by the US House of Representatives for his role in inciting insurrection?

Trump’s rusted-on supporters believe him to be without blame and will continue to lionise him as a paragon of virtue. Trump’s equally rusted-on opponents see only fault and wish him to be ground under the heel of history.

However, there is a large body of people who approach the question with an open mind – only to remain genuinely confused about what should come next.

On the one hand, there is an abiding fear that punishing Trump will fan the flames that animate his angry supporters elevating Trump’s status to that of ‘martyr-to-his-cause’. Rather than bind wounds and allow the process of healing to begin, the divisions that rend American society will only be deepened.

On the other hand, people believe that Trump deserves to be punished for violating his Oath of Office. They too want the wounds to be bound – but doubt that there can be healing without justice. Only then will people of goodwill be able to come together and, perhaps, find common ground.

There is merit in both positions. So, how might we decide where the balance of judgement should lie?

To begin, I think it unrealistic to hope for the emergence of a new set of harmonious relationships between the now three warring political tribes, the Republicans, Democrats and Trumpians. The disagreements between these three groups are visceral and persistent.

Rather than hope for harmony, the US polity should insist on peace.

Indeed, it is the value of ‘peace’ that has been most significantly undermined in the weeks since the Presidential election result was called into question by Donald Trump and his supporters. Rather than anticipate a ‘peaceful transition of power’ – which is the hallmark of democracy – the United States has been confronted by the reality of violent insurrection.

As it happens, I think that President Trump’s recent conduct needs to be evaluated against an index of peace – not just in general terms but specifically in light of what occurred on January 6th when a mob of his supporters, acting in the President’s name, broke into and occupied the US Capitol buildings – spilling blood and bringing death inside its hallowed chambers.

There is a particular type of peace that can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxon legal codes that provide the foundation for many of the laws we take for granted today. The King’s Peace originally applied to the monarch’s household – not just the physical location but also the ruler, their family, friends and retainers. It was a serious crime to disturb the ‘King’s Peace’. Over time, the scope of the King’s Peace was extended to cover certain times of the year and a wider set of locations (e.g. all highways were considered to be subject to fall under the King’s jurisdiction). Following the Norman Conquest, there was a steady expansion of the monarch’s remit until it covered all times and places – standing as a general guarantee of the good order and safety of the realm.

The relevance of all of this to Donald Trump lies in the ethical (and not just legal) effect of the King’s Peace. Prior to its extension, whatever ‘justice’ existed was based on the power of local magnates. In many (if not most places) disputes were settled on the principle of ‘might was right’.

The coming of the King’s Peace meant that only the ruler (and their agents) had the right to settle disputes, impose penalties, etc. The older baronial courts were closed down – leaving the monarch as the fountainhead of all secular justice. In a nutshell, individuals and groups could no longer take the law into their own hands – no matter how powerful they might be.

These ideas should immediately be familiar to us – especially if we live in nations (like the US and Australia) that received and have built upon the English Common Law. It is this idea that underpins what it means to speak of the Rule of Law – and everything, from the framing of the United States Constitution to the decisions of the US Supreme Court depend on our common acceptance that we may not secure our ends, no matter how just we think our cause, through the private application of force.

As should by now be obvious, those who want to forgive Donald Trump for the sake of peace are confronted by what I think is an insurmountable paradox. Trump’s actions fomented insurrection of the kind that fundamentally broke the peace – indeed makes it impossible to sustain. The insurrectionists took the law into their own hands and declared that ‘might is right’ … and they did so with the encouragement of Donald Trump and those who stood by him and whipped up the crowd in the days leading up to and on that fateful day when the Capitol was stormed.

There literally can be no peace – and therefore no healing – unless the instigators of this insurrection are held to account.

Finally, this is not to say that Donald Trump must suffer his punishment. There is no need for retribution or a restoration, through suffering, of a notional balance between ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. It may be enough to declare Donald Trump guilty of the ‘high crime and misdemeanour’ for which he was impeached. And if he remains without either shame or remorse, then it may also be necessary to protect the Republic from him ever again holding elected office – not to harm him but, instead, to protect the body politic.

Given all of this, I think that healing is possible … but only if built on a foundation of peace based on justice without retribution.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Tim Walker on finding the right leader

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

David Gonski on corporate responsibility

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 15 DEC 2020

Imagine if every school in Australia introduced comprehensive surveillance technology coupled with facial recognition, and was able to assign a score to each student based on how good a “school citizen” they were.

Students could access an app that provided them with feedback on things they’d done, or failed to do, throughout the day. The day-to-day data could then be collected and a general character assessment made of the child on, let’s say, a year-by-year basis. At the end of the year, maybe at presentation night, students would be told if they’d been “good” school citizens or not.

I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest most people would find this idea pretty repugnant. Many would see echoes of China’s oppressive social credit system. Words like “Orwellian” would be thrown around with reckless abandon.

Just don’t tell that to the families around the world for whom Christmas involves a character check from Santa Claus. Certainly don’t tell the 11 million-odd who have “adopted’” an Elf on the Shelf and will have dusted it off for the season.

If you haven’t heard of it, the Elf on the Shelf explains how Santa is able to see you when you’re sleeping and know when you’re awake. Manufactured by Creatively Classic Activities and Books, the Elf on the Shelf is a tool used by families to add some more wonder and fun to the Christmas season.

Parents move the elf around, and kids look to see where it will appear next. They’re often also told that because they don’t know where the elf is or what the elf is watching, they’d better make sure they’re behaving themselves. After all, the elf’s job is to report back to Santa.

That’s right. Santa has an army of tiny, surprisingly mobile little snitches embedded in every home, watching, collecting data, feeding it back to the big guy. For some families, the elf also leaves handy notes for the kids, to make sure they stay on St Nick’s good side. “I don’t like it when you don’t share your toys. I don’t want to have to tell Santa about this behaviour,” reads one note a parent shared online.

Social credit be damned. Santa had it figured out this whole time!

We tend to be more sceptical of surveillance when it comes to our kids. For instance, recent trials of facial recognition in Victorian schools have been met with human rights concerns and academic criticism. When Mattel developed Aristotle, a digital assistant to be given to newborn children who would grow and develop alongside them, it was pulled from the market for privacy concerns. Even tools like GPS tracking apps are the subject of general debate and controversy.

There are good reasons for these concerns. Law professor Julie E Cohen argues that “privacy fosters self-determination” and that it is “shorthand for breathing room to engage in the processes of boundary management that enable and constitute self-development”.

So, not only does the collection of children’s data put them at risk if that data falls into the wrong hands, there’s a stifling effect on children’s development when they feel like they’re continually being watched.

But the Elf on the Shelf isn’t quite analogous to China’s mass surveillance. For one thing, Santa only has about 11 million elves out there, which is amateur hour compared to China’s “Skynet” of over 200m cameras. For another, the Elf on the Shelf doesn’t use fear and promises of safety to gain people’s comfort with surveillance and data gathering; it uses fun.

Less like a social credit system, more Facebook. Esteemed company indeed.

Of course, Elf on the Shelf isn’t actually surveillance because – spoiler alert – it’s based on a myth. I’ve no doubt plenty of parents will dismiss what I’m saying here as unnecessary scaremongering over something that’s actually fine, fun and basically a bit of stupid play at Christmas time.

While this wouldn’t be the first time a philosopher has been accused of sucking the fun out of a situation, I’m not sure that argument cuts it.

First, the rise of “sharenting” and the pushback from children against parents who post too much information about them online indicates parents are not always the best custodians of their kids’ privacy. In general, a generation prone to oversharing on social media may not be the best judges of what lessons Elf on the Shelf is teaching.

Second, and more importantly, the effects of surveillance work even if the surveillance isn’t really happening. This was the genius of the infamous Panopticon – a prison designed by British philosopher Jeremy Bentham, where a guard tower could potentially observe any prisoner at any given time, but no prisoner could see the guard tower. It was always possible that you were being observed, which meant you behaved as though you were being observed at all times.

This logic is, of course, very creepy. It’s also very common – as another philosopher, Michel Foucault, later pointed out. You can build workplaces, schools, mental health institutions and yes, nationwide mass surveillance networks on similar principles. The concept is that the possibility of observation and judgement means there’s no need to force people to conform – they do it themselves. Arguably, China’s social credit system is the high-water mark of the logic of the Panopticon.

But the rhetoric – intentional or not – behind Elf on the Shelf has echoes of the Panopticon. It reads from the same playbook. The elf appears at random times and in random locations. It’s always possibly watching.

Whether that’s the goal parents are trying to achieve or not, we ought to be concerned about the effects of introducing and normalising this kind of behaviour monitoring and observation to kids.

As Olly Thorn, the philosopher behind Philosophy Tube tweeted: “He sees you when you’re sleeping He knows, when you’re awake, It’s a subtle, calculated technology of subjection.”

This isn’t necessarily a reason to ditch the tradition, but we can do away with the creepiness – especially as the myth becomes more and more like reality. It’s entirely possible to have an Elf on the Shelf and not play this game. Maybe the elf is just waiting for Santa to come and deliver the presents – and helps him unload the gifts. Perhaps you don’t use the elf as a tool for discipline but as a game and a story that’s played together.

Maybe you don’t need to tell the Santa story at all, but that’s another matter.

This article was first published in The Guardian Australia on 16 December, 2019.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is modesty an outdated virtue?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Market logic can’t survive a pandemic

Market logic can’t survive a pandemic

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Dr Richard Denniss 8 DEC 2020

For decades, neoliberalism has fuelled enormous scepticism about the role of government.

Whereas the ‘invisible hand’ of market forces is used as a synonym for efficiency and progress, the ‘dead hand’ of bureaucracy congers up waste and delay. But after decades of bad press, the Covid-19 pandemic seems to be restoring Australia’s faith in government.

Almost nobody, in Australia at least, trusts the market to solve a pandemic. Over the past 10 months, Australians have assumed that their elected representatives, and the bureaucracies they oversee, will solve all manner of problems on our behalf. And, by and large, the Australian public’s faith in government has been well placed.

It was the federal government, not the travel industry, that suddenly closed our international borders on March 2020 to slow the spread of the virus into Australia. It was the state premiers who closed our state borders to slow the spread within Australia. And, via the formation of the National Cabinet, our state and national leaders have delivered clearer messages, simpler rules, and more effective policies than almost any other government in the world.

Needless to say, mistakes were made. Passengers should not have disembarked from the Ruby Princess, Melbourne’s hotel quarantine system should have been better, aged care homes should have been provided with better information and more support, and the tracing app developed by the federal health department has been a waste of time and money.

But, despite the mistakes, Australia is largely virus-free with an economy that is starting to grow again. And trust in Australian political leaders has risen to record levels. State premiers, in particular, have surged in popularity as they stepped in to protect their residents.

Nobody thinks that ‘market forces’ could have done a better job of protecting Australians from Covid-19. Indeed, the sharpest criticism from the Coalition of Daniel Andrews is that he relied too heavily on private security guards and didn’t rely heavily enough on the Commonwealth’s offer to provide troops to guard the hotels. Think about that. Daniel Andrews is being criticised for not relying on the public sector enough!

When a vaccine finally arrives, how will we decide who gets it first? Will we ‘leave it to the market’ and let drug companies set whatever price they want or will we develop clear (bureaucratic) rules for which vulnerable groups and key workers will get it first at zero price?

Governments aren’t perfect, and neither are markets. We have always relied heavily on governments to provide health, education and transport infrastructure and we have always relied heavily on markets to provide food, clothing and entertainment. Different countries, at different points in time, make different choices about how and when to rely on the government, with voters ultimately having the final say.

While it is clear that the Covid-19 pandemic will have a lasting impact on Australia’s economy, society and democracy, what is not clear is what shape that impact will be. Will we wind back the deregulation of our privatised aged care system that led to the untimely death of so many vulnerable Australians? Will we invest more heavily in public health? Will we expand and modernise our public transport system to make it less crowded? Or will we just go back to cutting taxes and cutting spending on services?

The economic language of neoliberalism has had a profound impact on our public debates, our public institutions, and perhaps most importantly, our collective expectations of what governments can and can’t do.

But as any Australian who has watched the enormous death toll and economic destruction taking place in the US and much of Europe can see, the Covid-19 pandemic has made it clear that government intervention, political leadership and a strong sense of community are essential for addressing some problems.

It’s not inevitable that Australians will translate their new-found faith in governments into support for more government action on issues like climate change, inequality or the liveability of our cities. But it’s not impossible.

After decades of hearing that governments are the problem, Australians have just seen for themselves how effective governments can sometimes be.

Despite the Covid-19 crisis, Australia is one of the richest countries in the world, and while we can afford to do anything we want, we can’t afford to do everything we want.

Neoliberal rhetoric about the inherent inefficiency of government action has for decades stifled debate about which problems we would like the government to fix and which problems we are happy to leave to the market. But the new reality is that everyone agrees that governments have an important role to play in solving big problems.

Should we have a ‘gas fired recovery’ or a ‘green new deal’. Should we invest heavily in public housing or provide tax breaks for individual property investors? While it shouldn’t have taken a pandemic to provide it, at least we finally have room in our public debate to ask such questions.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethical issues and human resource development: some thoughts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Leaders, be the change you want to see.

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Give them a piggy bank: Why every child should learn to navigate money with ethics

BY Dr Richard Denniss

Dr Ricahrd Denniss is Chief economist and former Executive Director of the Australia Institute. Richard is a prominent Australian economist, author and public policy commentator, and has spent the last twenty years moving between policy-focused roles in academia, federal politics and think-tanks. He was also a Lecturer in Economics at the university of Newcastle and former Associate Professor in the Crawford School of Public Policy at ANU. He is a regular contributor to The Monthly and the author of several books including: Econobabble, Curing Affluenza and Dead Right: How Neoliberalism Ate Itself and What Comes Next?

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Eva Cox 8 DEC 2020

My 1995 ABC Boyer Lectures, ‘A Truly Civil Society’, outlined the ill effects of the then decade-plus political paradigm shift to neoliberalism.

In the years following WW2, governments implemented policy changes to ensure well-functioning societies that delivered social fairness. This was to avoid a repetition of the pre-war rise of dictatorships, such as happened in Germany and Italy where democracies were overthrown by the fascists. Much of this reconstruction included expanding health, education and welfare for communities to balance the existing inequities of market wealth creation.

From the 1980s, the failing USSR and the globalising of finance via petrodollars allowed big business to shift the paradigm to market forces and reduce the scope of governments. The effects were becoming evident while I was writing the Boyer’s in 1995, as neoliberalism was exacerbating the cuts to social goals and public funding. Growing distrust of democracy was also becoming apparent in many countries, including Australia.

Now, twenty-five years of policy shifts later, including a market-created Global Financial Crisis in 2008, these changes continue to have ill-effects on democratic governance and trust. Policies such as unfair distributions of taxes that favour businesses and the better-off have exacerbated this, as has the privatising of public services and public ownership of utilities and institutions. The promise that the private model of competition and wealth creation would create trickle-down wealth failed to eventuate. Nor did we see any sign of the market lowering prices for these services, as is promised by this model. Citizens, redefined now as just customers of what were once public services, have not found the market more efficient or effective.

Prioritising growth and profits over community needs and connections exacerbates distrust of those in power.

Finding jobs becomes more difficult as growth slows, and low wages remain for many of the often-feminised essential services, such as nursing and child care. The new gig-economy has also increased feelings of insecurity. Ergo, it has not been surprising that over the last decades there have been growing feelings amongst many people in democracies, including Australia, that those in power are not to be trusted.

Now that the neoliberal paradigm shift is obviously failing, we need to devise and define alternatives. The failure has created a fertile ground for the increasingly irrational ‘strong men’ leaders to grab power. These strong men undermine the idea of democracy and surge in on a wave of distrust. We now have in Australia, as elsewhere, increasing beliefs that society is unfair, feelings of real anger and despair, and a deep distrust of the political system. It is this unfairness that is the damaging cause of most of our problems.

The range of inequities in our current system include politics and policies that respond mainly to business demands and neglect community needs. The recent budget is a good example, where subsidies were available to incentivise businesses to hire more people, even if there were too few customers. Yet much-needed jobs in community and public spheres were barely mentioned.

We need changes that create a sense of fairness by providing good social and public services. People need to feel that they live in societies where they and their contributions are valued and their voice matters. We are social beings, connected, and need to feel safe and involved.

Assuming wealth inequality is a causal factor fails to recognise the real causes: self-interested economic goals that ignore and exclude the values of fairness and trust that are necessary to create a truly civil society.

The national cabinet’s response to the pandemic, an effective public health collaboration, reminded people what good governance looks like. Consequently, it has improved the levels of voter trust. There are now signs of reversal as the PM reverts to a private sector, economic-led recovery.

Now it’s up to us. We need policies that set social goals, fix environmental damage, and create fairness and long-term well-being. Here are some radical ideas: stop privatising community services and utilities, fix the messy unfair welfare system (perhaps introduce a universal social dividend), engage communities in planning for their needs, reform the tax system so that it’s fairer in the redistribution of resources, pass the Uluru Statement from the Heart. This way, everybody should get a fair go.

Outrageous ideas? Maybe, but replacing greed and self interest with fairness requires optimism and another paradigm shift!

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How BlueRock uses culture to attract top talent

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The Royal Commission has forced us to ask, what is business good for?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The 6 ways corporate values fail

BY Eva Cox

Eva Cox AO is an Adjunct Professor at The Jumbunna Institute of Research, University of Technology Sydney, looking at the problems of Indigenous policies. She has worked as political advisor, market researcher, academic and activist, with a high media profile. She delivered the ABC Boyer Lectures in 1995 on the theme A Truly Civil Society, on the need for trust as our social glue.

Narcissists aren’t born, they’re made

President elect Joe Biden won the recent United States election with 306 electoral college votes to Donald Trump’s 232. Biden also won the popular vote around 80 million to 73 million.

Trump has alleged the election is “rigged” and fraudulent, claims based on no evidence whatsoever, while his legal challenges have been thrown out by one court after another. In an attempted coup d’état, Trump has refused for weeks to concede defeat or to willingly undertake the essential part of the democratic process assisting the transition to the new administration before vacating the White House. It is hard to find a worse example of narcissistic entitlement.

Lack of empathy is at the heart of narcissism too, and there has been a breathtaking callousness in Trump’s indifference to the Covid catastrophe unfolding in the US and his persistent refusal to act. There are more than 12 million Covid cases in the US, among the very highest infection rates per million people in the world. More than a quarter of a million people have died.

On Friday November 20, new cases topped 200,000 in one day and there were more than 2000 deaths, adding to the horrific 250,000 plus death toll. The need for decisive action could not be more urgent. The extreme self-focus, the ‘All About Me’ aspect of narcissism, is evident as Trump plays golf, idly suggests war with Iran, and tweets self-pityingly about being cheated of his “rightful” victory.

One can see the origins of Trump’s narcissism growing up spoiled and overindulged in a wealthy but emotionally harsh and cold family. Donald’s father, Fred Trump, a real estate mogul, would berate him; “Be a Killer not a Loser.” That was the family ethos, the motto. To show kindness, care or admit vulnerability was to be a “loser.” His father not only encouraged Donald in his cruel bullying of siblings but also joined in. Both bear responsibility for the destruction of Donald’s elder brother, Fred Trump junior.

In the Trump family, only making money was valued. Fred was a highly skilled commercial airline pilot who was jeered at as nothing more than a “chauffeur in the sky,” and treated as beneath contempt because his profession did not earn the megabucks that real estate did. Fred was driven to alcoholism, depression, and died early at 42, suicide by drinking. It wasn’t just his toxic family, however, that created the malignant narcissist who refuses to leave the White House.

They call it the “asshole effect.” Stunning new research by the University of California’s Paul Piff shows that wealth increases narcissistic behaviour.

Piff conducted a series of real-life experiments which showed for example, that people driving new model and more expensive cars were 4 times more likely to cut drivers of lower status vehicles off at a crossing. They were three times less likely to yield at a pedestrian crossing. Drivers of the least expensive cars all gave way to pedestrians.

Intrigued by this, Piff did lab experiments and found “the richer the meaner” effect. The richest students were meaner and more likely to consider “stealing or benefiting from things which they were not entitled” than those from lower-class backgrounds. Piff said that “upper-class individuals feel more entitled, are less concerned with the needs of others, and at times were prepared to behave selfishly, even unethically, to get ahead.”

That is deeply concerning in times of mounting inequality. Wealthier people were more likely to agree with statements such as “I honestly just feel more deserving than other people.” They were also vainer, more likely to rush to a mirror and check themselves out if a photograph was being taken. They drew larger circles to represent themselves than they drew to represent other people.

If you think of yourself as bigger and more important than others, it’s not surprising that you have an excessive sense of entitlement and exploit others. They simply don’t matter as much as you do.

Trump is notorious for being cheap and cheating his employees of appropriate payments, as well as ruthlessly getting rid of them once they have passed their use-by date.

Piff’s laboratory experiments revealed that even when poorer people were simply primed to think of themselves as wealthy, this increased feelings of superiority and entitlement, and they began to behave selfishly. When people look down on others, “they tend to acquire the belief that they are better than others, more important and deserving.”

This led to bad behaviour, for example helping themselves to more sweets meant for children in a lab next door, than if they were primed to feel disadvantaged. “That suggests it is more the psychological effects of wealth than the money itself,” Piff said.

Strikingly, Piff found that in unequal societies, higher-income people were richer and meaner – less likely to give money to charity than poorer people – than in more equal societies.

It is not only wealth which can increase narcissistic behaviour. Patriarchal society asserts the superiority of men over women and gives them greater entitlements. Hardly surprising then that research shows that narcissism is higher in men than women. Research also shows that male entitlement and a sense of superiority can have appalling consequences for increased sexual aggression and predation and is a key factor in domestic violence.

Fame increases narcissism and male sexual entitlement, as we can see by the numbers of high-profile powerful men like Harvey Weinstein called out and brought to justice by the Me Too movement. Donald Trump infamously said “I’m automatically attracted to beautiful — I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. Just kiss. I don’t even wait. When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything!”

It’s not just rich and famous men who can behave like that. The scandal over a so-called “Triwizard Shorenament,” organised by privileged boys at the elite Sydney private boys school Shore, which charges $30,000 in annual fees, reeked of entitlement. Their plans for Muck Up day were racist, misogynist and cruel; “Spit on a homeless man”, “have sex with a woman over 80 kilograms,” or a woman who “scored” a lowly 3 out of 10 for looks, have sex with “an Asian chick”, and shit on a train.

So what is the answer?

There are clear lessons from the research on narcissism. Anything which leads to a sense of superiority and entitlement is bad news. Hierarchies among human beings based on wealth, race, sexuality or gender need to be challenged. Economic inequality leads to more narcissistic behaviour than exists in more equal societies. In parenting and education, we should beware the narcissistic pitfalls of privilege.

A sense of superiority and entitlement leads to exploitative and even cruel behaviour. If lack of empathy is a core component of narcissism with devastating results, then we need to engage in programs proven to raise empathy in schools. And we desperately need anti-entitlement programs asserting an ethic of care for others, instead of “Me First” as an ideal to live by.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

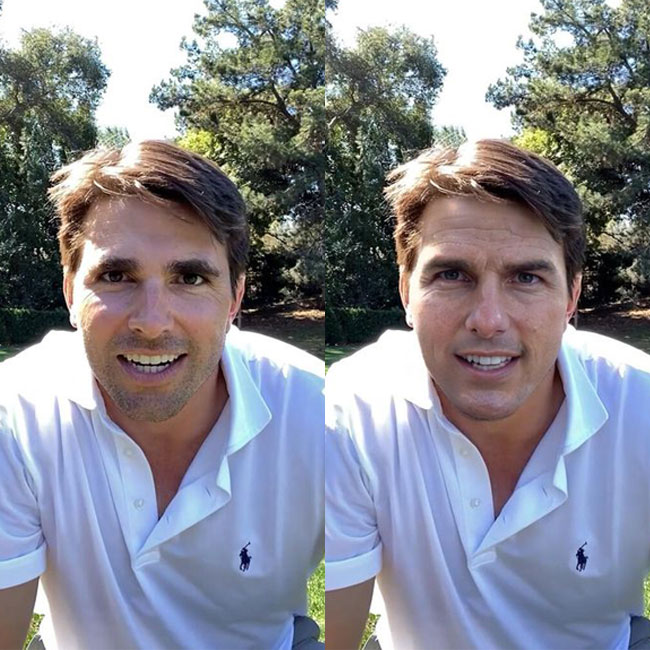

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

BY Anne Manne

Anne Manne is a cultural critic, essayist and writer. A former columnist for the Australian and the Age, she now mainly writes longer essays for The Monthly magazine on contemporary social issues. Her works include Motherhood (2005), a Quarterly Essay: Love and Money; The Family and The Free Market (2008) and her bestselling The Life of I: the new culture of narcissism. ( 2014, 2015) She is writing a new book on child sexual abuse in the Anglican Diocese of Newcastle.

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Tim Soutphommasane 25 NOV 2020

Citizenship isn’t often the stuff of inspiration. We tend to talk about it only when we are thinking of passports, as when migrants take out citizenship and gain new entitlements to travel.

When we do talk about the substance of citizenship, it often veers into legal technicalities or tedium. Think of the debates about section 44 of the Constitution or boring classes about the history of Federation at school. Hardly the stuff that gets the blood pumping.

Yet not everything that’s important is going to be exciting. The idea of citizenship is a critical foundation of a democratic society. To be a citizen is not merely to belong to such a society, and to enjoy certain rights and privileges; it goes beyond the right to have a passport and to cast a vote at an election.

To be a citizen includes certain responsibilities to that society – not least to fellow citizens, and to the common life that we live.

Citizenship, in this sense, involves not just a status. It also involves a practice.

And as with all practices, it can be judged according to a notion of excellence. There is a way to be a citizen or, to be precise, to be a good citizen. Of course, what good or virtuous citizenship must mean naturally invites debate or disagreement. But in my view, it must involve a number of things.

There’s first a certain requirement of political intelligence. A good citizen must possess a certain literacy about their political society, and be prepared to participate in politics and government. This needn’t mean that you can only be a good citizen if you’ve run for an elected office.

But a good citizen isn’t apathetic, or content to be a bystander on public issues. They’re able to take part in debate, and to do so guided by knowledge, reason and fairness. A good citizen is prepared to listen to, and weigh up the evidence. They are able to listen to views they disagree with, even seeing the merit in other views.

This brings me to the second quality of good citizenship: courage. Citizenship isn’t a cerebral exercise. A good citizen isn’t a bookworm or someone given to consider matters only in the abstract. Rather, a good citizen is prepared to act.

They are willing to speak out on issues, to express their views, and to be part of disagreements. They are willing to speak truth to power and willing to break with received wisdom.

And finally, good citizenship requires commitment. When a good citizen acts, they do so not primarily in order to advance their own interest; they do what they consider is best for the common good.

They are prepared to make some personal sacrifice and to make compromises, if that is what the common good requires. The good citizen is motivated by something like patriotism – a love of country, a loyalty to the community, a desire to make their society a better place.

How attainable is such an ideal of citizenship? Is this picture of citizenship an unrealistic conception?

You’d hope not. But civic virtue of the sort I’ve described has perhaps become more difficult to realise. The conditions of good citizenship are growing more elusive. The rise of disinformation, particularly through social media, has undermined a public debate regulated by reason and conducted with fidelity to the truth.

Tribalism and polarisation have made it more difficult to have civil disagreements, or the courage to cross political divides. With the rise of nationalist populism and white supremacy, patriotism has taken an illiberal overtone that leaves little room for diversity.

And while good citizenship requires practice, it can all too often collapse into curated performance and disguised narcissism: in our digital age, some of us want to give the impression of virtue, rather than exhibit it more truly.

Moreover, good citizenship and good institutions go hand in hand.

Virtue doesn’t emerge from nowhere. It needs to be seen, and it needs to be modeled.

But where are our well-led institutions right now? In just about every arena of society – politics, government, business, the military – institutional culture has become defined by ethical breaches, misconduct and indifference to standards.

And where can we in fact see examples of the common good guiding behaviour and conduct? In a society where public goods have been increasingly privatised, we have perhaps forgotten the meaning of public things. Our language has become economistic, with a need to justify the economic value of all things, as though the dollar were the ultimate measure of worth.

When we do think about the public, we think of what we can extract from it rather than what we can contribute to it.

We’ve stopped being citizens, and have started becoming taxpayers seeking a return. It’s as though we’re in perpetual search of a dividend, as though our tax were a private investment. As one jurist once put it, tax is better understood as the price we pay for civilisation.

But our present moment is a time for us to reset. The public response to COVID-19 has been remarkable precisely because it is one of the few times where we see people doing things that are for the common good. And good citizens, everywhere, are rightly asking what post-pandemic society should look like.

The answers aren’t yet clear, and we all should consider how we shape those answers. It may just be the right time for us to take citizenship seriously again.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The truth isn’t in the numbers

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Economic reform must start with ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

It’s time to talk about life and debt

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

BY Tim Soutphommasane

Tim Soutphommasane is a political theorist and Professor in the School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Sydney, where he is also Director, Culture Strategy. From 2013 to 2018 he was Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission. He is the author of five books, including The Virtuous Citizen (2012) and most recently, On Hate (2019).

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Bryan Mukandi 25 NOV 2020

The wing of the philosophy department that I occupied during my PhD studies is known as ‘Continental’ philosophy. You see, in Australia, in all but the most progressive institutions, colonial chauvinism so prevails that philosophy is by definition, Western.

A domestic dispute, however, means that most aspiring academic philosophers must choose between the Anglo-American tradition, or the Continental European one. I chose the latter because of what struck me as the suffocating rigidity of the former. Yet while Continental philosophy is slightly more forgiving, it generally demands that one pick a master and devote oneself to the study of the works of this (almost always dead, white, and usually male) person.

I chose for my master a white man of questionable whiteness. Born and raised on African soil, Jacques Derrida was someone who caused discomfort as a thinker in part because of his illegitimate origins. In response, Derrida worked so hard to be accepted that one of the emerging masters of the discipline wrote an approving book about him titled The Purest of Bastards. I, not wanting to undergo this baptism in bleach, ran away into the custody of a Black man, Frantz Fanon.

Born in Martinique, even further in the peripheries of empire than Derrida; a qualified medical practitioner and specialist psychiatrist rather than armchair thinker; and worst of all, someone who cast his lot with anti-colonial fighters – Fanon remains a most impure bastard. My move towards him was therefore a moment of the exercise of what Paul Beatty calls ‘Unmitigated Blackness’ – the refusal to ape and parrot white people despite the knowledge that such refusal, from the point of view of those invested in whiteness, ‘is a seeming unwillingness to succeed’.

It’s not that I didn’t want to succeed. Rather, I found Fanon’s words compelling. The Black, he laments, ought not be faced with the dilemma: ‘whiten yourself or disappear’. I didn’t want to have to put on whiteface each morning. I didn’t want to have to translate myself or my knowledge for the benefit of white comprehension, because that work of translation often disfigures both the work and the translator.

I couldn’t stomach the conflation of white cultural norms with professionalism; the false belief that familiarity with (white) canonical texts amounts to learning, or worse, intelligence; or the assessment of my worth on the basis of my learnt domesticity.

The mistake I made, though, was to assume that moving to the Faculty of Medicine would exempt me from the demand to whiten.

Do you know that sticker, the one you’ll sometimes see on the back of a ute, and often a ute bearing a faux-scrotum at the bottom of the tow bar: “Australia! Love It or Leave It!”? I don’t think that’s a bad summation of the dominant political philosophy in this country. It comes close. Were I to correct the authors of that sticker, I would suggest: “Australia: whiten, or disappear!” This, I think, is the overarching ethos of the country, emanating as much from faux-scrotum laden utes, to philosophy departments, medical institutions, and I suspect board rooms and even the halls of parliament.

What else does, for example, Closing the Gap mean? Doesn’t it boil down to ‘whiten or disappear’, with both reduction to sameness and annihilation constituting paths to statistical equivalence?

I marvel at the ways in which Indigenous organisations manoeuvre the policy, but I suppose First Nations peoples have been manoeuvring genocidal impulses cast in terms of beneficence – ‘bringing Christian enlightenment’, ‘comforting a dying race’, ‘absorption into the only viable community’ – since 1788.

Furthermore, speak privately to Australians from black and brown migrant backgrounds, and ask how many really think the White Australia Policy is a thing of the past. Or just read Helen Ngo’s article on Footscray Primary School’s decision to abolish its Vietnamese bilingual program in favour of an Italian one. As generous as she is, it’s difficult to read the school’s position as anything but the idea that Vietnamese is fine for those with Vietnamese heritage; but at a broader level, for the sake of academic outcomes, linguistic development and cultural enrichment, Italian is the self-evidently superior language.

The difference between the two? One is Asian, while the other is European, where Europe designates a repository into which the desire for superiority is poured, and from which assurance of such is drawn. Alexis Wright says it all far better than I can in The Swan Book.

There sadly prevails in this country the brutal conflation of the acceptance of others into whiteness; with tolerance, openness or even justice.

The Italian-speaking Vietnamese child supposedly attests to ‘our’ inclusivity. Similarly, so long as the visible Muslim woman isn’t (too) veiled, refrains from speaking anything but English in public, and is unflinching throughout the enactment of all things haram (forbidden) – provided that her performance of Islam remains within the bounds of whiteness, she is welcome.

This is why so many the medical students whom I now teach claim to be motivated by the hope of tending to Indigenous, ethnically diverse, differently-abled and poor people. Yet only a small fraction of those same students are genuinely willing to learn how to approach those patients on those patients’ terms, rather than those of a medical establishment steeped in whiteness. To them, the idea of the ‘radical reconfiguration of power’ that Chelsea Bond and David Singh have put forward – that there are life affirming approaches, terms of engagement, even ways of being beyond those conceivable from the horizon of whiteness – is anathema.

Here, we come to the crux of the matter: a radical reconfiguration is called for. Please allow me to be pedantic for a moment. In her Raw Law, Tanganekald and Meintangk Law Professor, Irene Watson, writes about the ‘groundwork’ to be done in order to bring about a more just state of affairs. This is unlike German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s Groundwork for a Metaphysics of Morals, by my reading a demonstration of the boundlessness of white presumption and white power, disguised as the exercise of reason. Instead, like African philosopher Omedi Ochieng’s Groundwork for the Practice of a Good Life, but also unlike that text, Watson’s is a call to the labour of excavation, overturning, loosening.

As explained in Asian-Australian philosopher Helen Ngo’s The Habits of Racism, a necessary precondition and outcome of this groundwork – particularly among us settlers, long-standing and more recent, who would upturn others’ lands – is the ongoing labour of ethical, relational reorientation.

Only then, when investment in and satisfaction with whiteness are undermined, can all of us sit together honestly, and begin to work out terms.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Epistemology

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

But how do you know? Hijack and the ethics of risk

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

BY Bryan Mukandi

is an academic philosopher with a medical background. He is currently an ARC DECRA Research Fellow working on Seeing the Black Child (DE210101089).

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 25 NOV 2020

This is the moment when I’m finally going to get my Advanced Level Irony Badge. I’m going to write an opinion piece on why we shouldn’t have so many opinions.

I’ve spent the majority of this week digesting the findings from the IDGAF Afghanistan Inquiry Report. I’m still making sense of the scope and scale of what was done, the depth of the harm inflicted on the Afghan victims and their community at large and how Australian warfighters were able to commit and permit crimes of this nature to occur.

My academic expertise is in military ethics, so I’ve got an unfair advantage when it comes to getting a handle on this issue quickly, but still, I was late to the opinion party. Within an hour or so of the report’s publication, opinions abounded on social media about what had happened, why and who was to blame. This, despite the report being over five hundred pages long.

We spend a lot of time today fearing misinformation. We usually think about the kind that’s deliberate – ‘fake news’ – but the virality of opinions, often underinformed, is also damaging and unhelpful. It makes us confuse speed and certainty with clarity and understanding. And in complex cases, it isn’t helpful.

More than this, the proliferation of opinions creates pressure for us to do the same. When everyone else has a strong view on what’s happened, what does it say about us that we don’t?

We live in a time when it’s not enough to know what is happening in the world, we need to have a view on whether that thing is good or bad – and if we can’t have both, we’ll choose opinion over knowledge most times.

It’s bad for us. It makes us miserable and morally immature. It creates a culture in which we’re not encouraged to hold opinions for their value as ways of explaining the world. Instead, their job is to be exchanged – a way of identifying us as a particular kind of person: a thinker.

If you’re someone who spends a lot of time reading media, you’ve probably done this – and seen other people do this. In conversations about an issue of the day, people exchange views on the subject – but most of them aren’t their views. They are the views of someone else.

Some columnist, a Twitter account they follow, what they heard on Waleed Aly’s latest monologue on The Project. And they then trade these views like grown-up Pokémon cards, fighting battles they have no stake in, whose outcome doesn’t matter to them.

This is one of many things the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard had in mind when he wrote about the problems with the mass media almost two centuries ago. Kierkegaard, borrowing the phrase “renters of opinion” from fellow philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, wrote that journalism:

“makes people doubly ridiculous. First, by making them believe it is necessary to have an opinion – and this is perhaps the most ridiculous aspect of the matter: one of those unhappy, inoffensive citizens who could have such an easy life, and then the journalist makes him believe it is necessary to have an opinion. And then to rent them an opinion which, despite its inconsistent quality, is nevertheless put on and carried around as an article of necessity.”

What Kierkegaard spotted then is just as true today – the mass media wants us to have opinions. It wants us to be emotional, outraged, moved by what happens. Moreover, the uneasy relationship between social media platforms and media companies makes this worse.

Social media platforms also want us to have strong opinions. They want us to keep sharing content, returning to their site, following moment-by-moment for updates.

Part of the problem, of course, is that so many of these opinions are just bad. For every straight-to-camera monologue, must-read op-ed or ground-breaking 7:30 report, there is a myriad of stuff that doesn’t add anything to our understanding. Not only that, it gets in the way. It exhausts us, overwhelms us and obstructs real understanding, which takes time, information and (usually) expert analysis.

Again, Kierkegaard sees this problem unrolling in his own time. “Everyone today can write a fairly decent article about all and everything; but no one can or will bear the strenuous work of following through a single solitary thought into the most tenuous logical ramifications.”

We just don’t have the patience today to sit with an issue for long enough to resolve it. Before we’ve gotten a proper answer to one issue, the media, the public and everyone else chasing eyes, ears, hearts and minds has moved on to whatever’s next on the List of Things to Care About.

So, if you’re reading the news today and wondering what you should make of it, I release you. You don’t have to have the answers. You can be an excellent citizen and person without needing something interesting to say about everything.

If you find yourself in a conversation with your colleagues, mates or even your kids, you don’t need to have the answers. Sometimes, a good question will do more to help you both work out what you do and don’t know.

This is not an argument to stop caring about the world around us. Instead, it’s an argument to suggest that we need to rethink the way we’ve connected caring about something with having an opinion about something.

Caring about a person, or a community means entering into a relationship with them that enables them to flourish. When we look at the way our fast-paced media engages with people – reducing a woman, daughter, friend and victim of a crime to her profession, for instance – it’s not obvious this is making us care. It’s selling us a watered-down version of care that frees us of the responsibility to do anything other than feel.

Of course, this is possible. Journalistic interventions, powerful opinion-driven content and social media movements can – and have – made meaningful change in society. They have made people care.

I wonder if those moments are striking precisely because they are infrequent. By making opinions part of our social and economic capital, we’ve increased the frequency with which we’re told to have them, but alongside everything else, it might have diluted their power to do anything significant.

This article was first published on 21 August, 2019.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

There’s something Australia can do to add $45b to the economy. It involves ethics.

There’s something Australia can do to add $45b to the economy. It involves ethics.

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 29 OCT 2020

Australia faces a perfect storm. An economic deficit, a global pandemic, an uncertain future of work, and long-term social and environmental change around the climate crisis and reconciliation with Indigenous Australians to name but a few.

Adding to this magnitude of challenges are the low levels of trust Australians have in our leaders and our neighbours. In fact, research has found that only 54% of Australians generally trust people they interact with, and as a nation we score ‘somewhat ethical’ on the Governance Institute’s Ethics Index.

How do we navigate the road ahead? One thing is abundantly clear: we need better ethics. That’s why we commissioned Deloitte Access Economics to find out the economic benefits of improving ethics in Australia.

The outcome is The Ethical Advantage, a report that uses three new types of economic modelling and a review of extensive data sets and research sources to mount the case for pursuing higher levels of ethical behaviour across society.

For the first time, the report quantifies the benefits of ethics for individuals and for the nation. The ethical advantage is in, and the findings are compelling. They include:

A stronger economy: If Australia was to improve ethical behaviour, leading to an increase in trust, – average annual incomes would increase by approximately $1,800. This in turn would equate to a net increase in total incomes of approximately $45 billion.

More money in Australians pockets: Improved ethics leads to higher wages, consistent with an improvement in labour and business productivity. A 10% increase in ethical behaviour is associated with up to a 6.6% in individual wages.

Better returns for Australian businesses: Unethical behaviour leads to poorer financial outcomes for business. Increasing a firm’s performance based on ethical perceptions, can increase return on assets by approximately 7%.

Increased human flourishing: People would benefit from improved mental and physical health. There is evidence that a 10% improvement in awareness of others’ ethical behaviour is associated with a greater understanding one’s own mental health.

The report’s lead author and Deloitte Access Economics partner, Mr John O’Mahony, said:

“No one would seriously argue that pursuing higher levels of ethical behaviour and focus was a bad thing, but articulating the benefits of stronger ethics is more challenging.”

“Our report examines the case for improving ethics as a way of addressing these broader economic and social challenges – and the nature and extent of the benefits that would accrue to the nation if we got this right.”

The report also identifies five inter–linked areas for improvement for Australia and its approach to ethics, supported by 30 individual initiatives:

- Developing an Ethical Infrastructure Index

- Elevating public discussions about ethics

- Strengthening ethics in education

- Embedding ethics within institutions

- Supporting ethics in government and the regulatory framework

The findings and recommendations demonstrate the value of The Ethics Centre’s continued contribution to Australian life. For thirty years, The Ethics Centre has aimed to elevate ethics within public debate, organisations, education programs and public policy. Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, Dr Simon Longstaff said the findings validate the impact of those activities and reveals the potential that can be unlocked with greater support.

“The compelling moral argument that ethical behaviour binds a society and its institutions in a common good is now, thanks to Deloitte Access Economics’ research and modelling, also a compelling economic argument. Best of all, we need not be perfect – just better.”

A copy of The Ethical Advantage can be found at this link.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Should we be afraid of consensus? Pluribus and the horrors of mainstream happiness

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights