The virtues of Christmas

The virtues of Christmas

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 20 DEC 2019

Christmas is upon us. It’s a time of giving. A time for celebrating with family and love ones. And a time to navigate a number of sticky ethical challenges.

It starts early in the morning; the gifts are distributed, and you unwrap Grandma’s exquisitely wrapped parcel only to reveal a hideous pair of underwear that may have once been in fashion during the great depression. You immediately call on your best poker face, but it may have already betrayed your disappointment. Should you lie and say, ‘thanks Nan, I really love them?’

Next comes the Christmas lunch tirade; you’re seated next to an opinionated uncle you only see once a year at Christmas who, predictably, after too many of his favourite Christmas beverages begins an annual festive diatribe that escalates rapidly from the opinionated to the offensive. Do you speak your mind?

Finally, the inevitable clash with your mother in law; she cannot help being critical about everything surrounding the festivities. The inevitable flare-up will happen after clearing away lunch, which you like to refer to it as the annual arm wrestle, a well-worn conflict over everything from how to stack the dishwasher to how the kids can and cannot play. This year will no doubt be worse as you are hosting the event. Do you stand your ground?

Most of us ask “What should I do?” when we think about ethics. However, we can approach it another way by asking, “What kind of person should I be?” Philosophical thinkers in this tradition turn to virtue ethics for the answers.

While it’s one thing to ask what kind of person should I be, it’s another thing to know how to live as that person. For Aristotle the answer to both of these questions is to act virtuously. Acting as though we already possess the best virtues is how we develop a virtuous character.

And if ever there was a time to test out the virtues of our character, it’s Christmas.

Virtue ethics, unlike other approaches, does not provide specific rules for addressing ethical questions. Instead, good actions are those that a person of good character would display. Aristotle, one of the most influential philosophers in this tradition, developed a comprehensive system of virtue ethics.

Let’s take a look at how it can help us navigate the minefield of Christmas’ annual dilemmas.

The underwear from Grandma? If asking what should you do, you might take a lead from consequentialism. You could simply smile and say ‘I love it Grandma’. After all, she meant well, a white lie makes her happy, keeps the economy ticking and doesn’t rock the family emotional boat. It produces the best overall outcome.

Other philosophers might suggest a different approach. Those in the deontological tradition, such as Immanuel Kant would argue that lying of any kind is unethical, even those white lies that are intended to spare someone’s feelings.

Unlike other approaches to ethics, virtue ethics does not rely on rules to guide action. While ‘do not lie,’ is a rule, ‘being honest’ is a virtue.

However, a virtue, on its own, doesn’t tell us too much that is helpful because virtues are interrelated, you can’t have one virtue without having others. To have a virtue is to be a particular type of person with a particular mindset and outlook on life. They are what’s called a ‘multi-track disposition’ – they go all the way down.

Honesty is not the only virtue at stake here. Acting virtuously requires us to calibrate between virtues. Because Grandma has the best intentions, she will no doubt take your honesty to heart. Honestly speaking your mind could be selfish at one extreme, and while a white lie at the other end might be considered selfless. What sits between these extremes Aristotle called the Golden Mean.

What would a fair person do? They might tell Grandma that they appreciate the thought but would like to do justice to her intentions by exchanging the gift for something that they will like, wear and remember Grandma every time they put it on.

So, let’s see what virtue ethics can teach us about managing that outspoken uncle. Imagine that dessert is now served and your uncle has flipped the switch to obnoxious. You try and avoid engaging with his tirades every year, but this year he is particularly offensive. His views are not only a dampener on the festive feels, but several members of the family are visibly hurt and upset by some of his more extreme views.

All families have their patterns that play out when people come together and the pre-determined roles we all play are difficult to shift.

What would we do if we were already a virtuous person? By imagining what a virtuous character would do in this situation we can start to practically explore how to become the best version of ourselves.

In the virtue ethics approach imagination is important in helping to shift unthinking and prescribed patterns of behaviours. What would we do if we were already a virtuous person? By imagining what a virtuous character would do in this situation we can start to practically explore how to become the best version of ourselves.

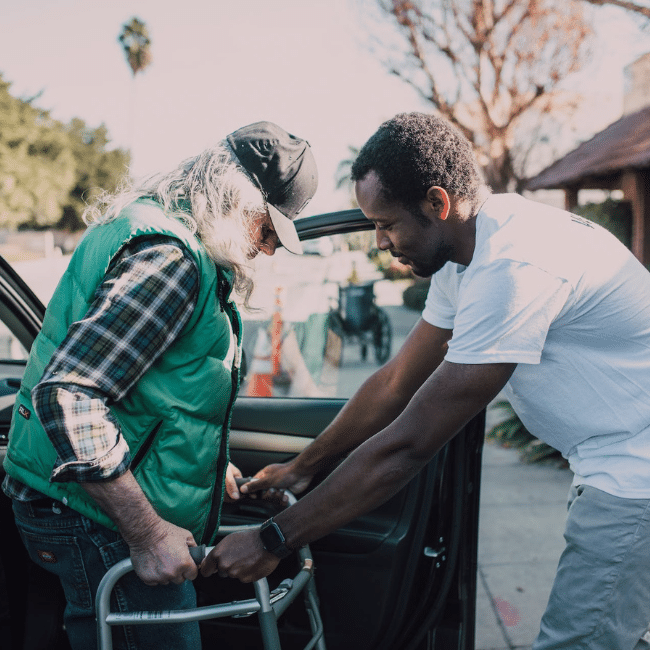

A virtuous person might ask themselves ‘how would I like to be treated if I were them?’ This particular uncle may not have many opportunities in their daily life to be heard. In many of the virtue ethics traditions compassion is a cardinal virtue. Exercising the virtue of compassion allows us to not only avoid rushing to judgement, but also gives us space to disarm the triggers that usually fire off in response to his toxic views.

The virtue of temperance – self-control and restraint – also helps here. While his views may trigger you strongly, appealing to logic with counterarguments will most likely not be effective.

It is almost impossible to change a person’s strongly held views with counter-logic. Paraphrasing back the points and emotions they are expressing not only lets them know their experience matters but also provides a circuit breaker by reflecting back their views. Research suggests that engaging in this way can make someone feel more understood and, as a result, less defensive or difficult.

When unsure about what the best virtue looks like in practice, virtue ethics suggests looking to someone of good character for direction by imagining how they would act in the same situation. Moral exemplars are an important feature of virtue ethics. Ethics is messy and no decision procedure provides a precise algorithm which will tell us definitively what to do when faced with difficult choices. Moral exemplars are people in our world who possess the best form of the virtues. Knowing what to do is not simply a matter of internalising a rule; for Aristotle virtue ethics it is about doing the right thing at the right time, in the right way and for the right reason. Moral exemplars help show us the way.

So, when it comes to the inevitable clash with your mother in law, imagine what someone you admire most would do. A moral exemplar might act intentionally with the virtues of humility, grace and generosity, showing her that what is important in hosting Christmas is not the power struggle to control the day but respecting differences and others’ boundaries. They might find ways to include some of her traditions in the day.

The development of character is at the heart of virtue ethics. We develop that character throughout our life through the virtues and in doing so we make wise choices.

This Christmas people may be looking at you to be that person.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to deal with people who aren’t doing their bit to flatten the curve

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Duties of care: How to find balance in the care you give

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 DEC 2019

If you’re looking for ways to support a more ethical life, here are five simple lifestyle changes that can help get you there.

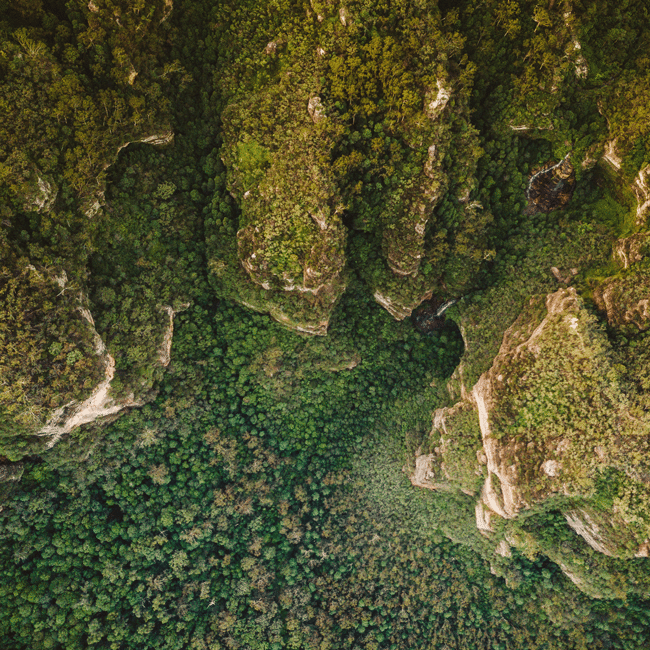

Get back to nature

Aristotle believed everything in nature contains “something of the marvellous”. It turns out nature might also help make us a bit more marvellous. Research by Jia Wei Zhang and colleagues revealed how “perceiving natural beauty” (basically, looking at nature and recognising how wonderful it is) can make you more prosocial. Specifically, it can make you more helpful, trusting and generous. Nice one, trees.

The apparent reason for this is because a connection with nature leads to an increase in the experience of positive emotions. People are happier when they are connected with nature and other research suggests happy people tend to be more prosocial. Inadvertently, Zhang and his colleagues learned, this means nature helps make us better team players.

Read literature to develop ‘Theory of Mind’

In psychology, ‘Theory of Mind’ refers to the ability to understand the emotions, intentions and mental states of other people and to understand other people’s mental states are different from our own. It’s a crucial component of empathy. Like most things, our Theory of Mind improves with practice.

David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano think one way of practising and developing Theory of Mind is by reading literary fiction. They believe literature “uniquely engages the psychological processes needed to gain access to characters’ subjective experiences” because it doesn’t aim to entertain readers but challenge them.

Work up a sweat

As well as the health benefits it brings, exercise can make you a more virtuous person. Philosopher Damon Young believes exercise brings about “subtle changes to our character: we are more proud, humble, generous or constant”.

Pride is usually seen as a vice but exercise can give us a healthy sense of pride, which Young defines as “taking pleasure in yourself”. Taking pleasure in ourselves and recognising ourselves as valuable has obvious benefits for self-esteem, but it also gives us a heightened sense of responsibility. By taking pride in the work we’ve invested in ourselves, we acknowledge the role we have making change in the world, a feeling with applications far broader than the gym.

Take meal breaks when you’re making decisions

In 2011, an Israeli parole board had to consider several cases on the same day. Among them were two Arab-Israelis, each of them serving 30 months for fraud. One of them received parole, the other didn’t. The only difference? One of their hearings was at the start of the day, the other at the end.

Researcher Shai Danzigner and co-authors concluded “decision fatigue” explained the difference in the judges’ decisions. They found the rate of favourable rulings were around 65% just after meal breaks at the start of the day and lunch time, but they diminished to 0% by the end of the session.

There’s some good news though. The research suggests a meal break can put your decision making back on track. Maybe it’s time to stop taking lunch at your desk.

Get a good night’s sleep

We’ve been starting to pay more attention to the social costs of exhaustion. In NSW, public awareness campaigns now list fatigue as one of the ‘big three’ factors in road fatalities alongside speeding and drink driving. It turns out even if it doesn’t kill you, exhaustion can lead to ethical compromises and slip ups in the workplace.

In 2011, Christopher Barnes and his colleagues released a study suggesting “employees are less likely to resist the temptation to engage in unethical behaviour when they are low on sleep”. When we’re tired we experience ‘ego depletion’ – weakening our self-control. Experiments conducted by Barnes’ team suggest when we’re tired we’re vulnerable to cutting corners and cheating. So, if you’re thinking of doing something dodgy, sleep on it first.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Sally Haslanger

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 19 DEC 2019

The kids are on school holidays but the lessons don’t have to end there. Christmas time offers a great opportunity to teach our kids about ethics. Philosopher Dr Matt Beard shares his top stories for sharing ethical ideas with your children.

1. How the Grinch Stole Christmas – Doctor Seuss

The Grinch is a lonely monster who lives by himself on Mt Crumpit. Bothered by the Christmas noise from nearby Whoville he decides to spoil their fun. Disguised as a particularly ugly Santa Clause, the Grinch sneaks down the chimneys of the people of Whoville and steals their gifts. But to the Grinch’s surprise, he can’t dent the Whos’ Christmas spirit and his heart starts to melt.

“What if Christmas, he thought, doesn’t come from a store? What if Christmas… perhaps… means a little bit more?”

This classic by Doctor Seuss is more relevant than ever for kids growing up in an age when the holiday season is increasingly commercialised. The Whos lose all their ‘stuff’ but don’t lose their sense of Christmas. How would you or your kids feel if there were no presents at Christmas? What would you celebrate?

2. The Selfish Giant – Oscar Wilde

Not technically a Christmas story, but still a lovely one for this time of year. It’s the tale of a selfish giant who first refuses to allow children to play in his gardens and then has a change of heart.

This story has extra resonance for readers within the Christian tradition (and kids may need an explainer as to what the ending means), but the message does transcend religion. Talk to your kids about how selfishness can be isolating, joys shared are joys multiplied and the importance of showing kindness to whomever we meet – strong, weak, tall, clever or otherwise.

3. The Lump of Coal – Lemony Snicket

Coal is the perennial threat against children – bad kids get given coal. But what happens when a lump of coal is good? What happens if the child who receives it wants to make art? And do all kids who receive a lump of coal turn out rotten?

Lemony Snicket’s short story big questions of authenticity and purpose through a living lump of coal that flees a barbeque in search of it’s own purpose. After some failed endeavours he meets a department store Santa who puts him into his ‘bratty’ son’s stocking.

But his son doesn’t feel punished. Together with the lump of coal they become successful artists and open a restaurant in Korea.

“It is a miracle if you can find true friends, and it is a miracle if you have enough food to eat, and it is a miracle if you get to spend your days and evenings doing whatever it is you like to do.”

It’s not your typical Christmas story, but that’s part of the appeal. Are we forced to be the people we’re born as? The Lump of Coal teaches us gratitude for the everyday and an ability to overcome social origins of birth.

4. The Gift of the Magi – O Henry

This is a personal favourite and a good one to read before you take your kids off for a last minute Christmas shop. A married couple, both hard up for money, are desperate to buy each other wonderful gifts. Della wants to buy James a superb chain for his watch, which is his prized possession. To pay for it she sells her hair – her pride and joy, and James’ too. She buys James a fetching chain only to learn he has sold his watch to buy her a new set of combs!

“But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest. Of all who give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest. Everywhere they are wisest. They are the magi.”

The Gift of the Magi could seem absurd to some – to highlight the pointlessness of our obsession with giving. But that wasn’t the message O Henry hoped readers would take away. He wanted to highlight the true meaning of gift giving – a thoughtful gesture to rekindle a connection to the other person.

5. The Original Christmas Story

Whether or not you’re religious, the origins of Christmas lie in the same story – of a baby in a manger, surrounded by shepherds, angels and wise men. Props aside there are universal messages to be gleaned from religious stories and traditions.

The Christian story holds that the world’s saviour arrived as a newborn child into a stable for farm animals. It’s worth having a talk about how this image contrasts with our usual ideas about power.

Do we sometimes dismiss people because of where they’ve come from or how much money they have?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

How to live a good life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to deal with people who aren’t doing their bit to flatten the curve

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Do we have to choose between being a good parent and good at our job?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Metaphysical myth busting: The cowardice of ‘post-truth’

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 17 DEC 2019

Don’t be distracted by the exploding sheds, steamrolled silverware and factory pressed field of poppies.

Many of the best works in Cornelia Parker’s exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) are small and unassuming. They are the quiet pieces that ask us to contemplate the nature of the technology we use in acts of violence.

A small pile of dust, some short leads of wire, a child’s doll split in two. These found object artworks – sculptures, just not those carved into marble or clay – are less about the state you see them in, but the journey they have taken.

On closer inspection (and with a little gallery guidance) we find intentional transformations of objects often associated with brutal violence: a gun, its bullets, the blade of a guillotine.

But don’t be alarmed. There is a dark sense of humour at play here. The disemboweled doll, a ginger-haired child in his newsboy cap and overalls, has a cartoon quality to his expression that echoes less of screams of pain than the shock of a bee sting. The boy has been severed at the waist by a guillotine. The very same guillotine that beheaded the infamous Queen of France, Marie Antoinette.

We understand a guillotine as a tool of violence and power, designed to distribute French revolutionary justice at speed to behead the head of state. Here Parker has used the same tool that once transformed European history, to split a stuffed toy of Oliver Twist. Its title suggests a shared fate, that this piece of technology link the iconic Dickensian poor boy and the poster woman for opulence.

Shared Fate (Oliver), Cornelia Parker (2008)

The works on display in the gallery often ask us to consider what these tools of violence are used for, and our role in using them.

Sawn Up Sawn Off Shotgun (2015) has a similar tale of transformation. The story goes: a factory manufactured a shotgun, a criminal cut off its barrel to make it deadlier. He used it to murder an innocent person. It was collected as evidence by police to convict the man, before being decommissioned by being cut into smaller segments. It sits lifeless in front of us now in this quartered state.

In what way was the gun designed to kill? How did the modifications by each person impact its deadliness? And how does its use reflect on the ethics and values of those who designed, manufactured and modified this once-deadly artefact? It’s a neat example that calls to mind some of The Ethics Centre’s the principles for the ethics of design.

The design of the original shotgun, manufactured and distributed legally, embodied a set of values. Options include: the ‘good’ of farmers protecting their livestock from predators or the ‘good’ sporting competition using firearms. However, it was also a feature of the shotgun that beyond shooting ducks and foxes, it had the capacity to take a human life including during the commission of crimes. To what extent was that violent possibility actively noted and considered? Did the designer and manufacturer take any steps to protect against unintended uses?

Of course, we know also that the shotgun was modified and used beyond its intended purpose. By cutting off the barrel, the gun was deliberately modified to aid concealment and increase its deadly effect at close range. Whatever values might have been explicit in the original design are subverted by the modification where the explicit aim becomes to maim and kill in confined spaces.

This is what we consider the post-phenomenology of technology. We describe this in Ethics by Design: Principles for Good Technology as “…when a hitman picks up a firearm, he sets the purpose of the gun as a murder weapon. However, he also uses the gun to constitute himself as a murderer.”

We are told that the user in this case used this shotgun for just that purpose and in doing so made himself a murderer.

In its final transformation the design is changed once more. Using the same means as the criminal, cutting the shotgun again, the police officers have rendered it effectively useless. It no longer possesses the affordances of a weapon: no trigger to pull, no barrel to aim. It is a disembodied mess of its former designs, purpose and values. Here then the police constitute themselves as peace-keepers, because by destroying the deadly weapon they embody law and order.

Embryo Firearms (1995) Cornelia Parker.

If you take away from this the mantra that ‘guns don’t kill people, people kill people’ then there is another piece we are challenged to consider. Embryo Firearms (1995) presents two solid lumps of metal in the crude shape of pistols. At this point in their manufacturing they are absolutely harmless, resembling the type of gun you might cut from wood as a prop. These ‘guns’ are mere symbols – no more dangerous than any other lump of metal of equivalent heft.

We are informed though that this metal was intended to become a Colt firearm; one of millions produced each year.

The fact that any resulting weapon of this production process could be used for multiple purposes does not mean that it is ethically ‘neutral’. While guns themselves don’t have agency or intentions, their design and function shapes the user’s agency and open up a range of possible value-laden activities.

In their embryonic state these handguns provide as much agency as any slab of metal. We know at some point though, as the barrel is hollowed out, the firing pin is placed and the trigger is pulled, a tool of violent potential is born.

Transformation of intended design and purpose is taking place throughout Cornelia Parker’s works. Bullets are reduced to metal threads used to create geometric patterns, murder weapons are reduced to harmless dust via chemical precipitation, and our expectations about technology, art and violence are flipped on their heads.

The Ethics Centre is presenting The Ethics of Art and Violence a special event inspired by the work of acclaimed British artist Cornelia Parker currently on exhibition at the MCA. For more about the event click here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Agree to disagree: 7 lessons on the ethics of disagreement

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 17 DEC 2019

If you’re gifted with downtime this holiday season, we’ve curated some big ideas for you to read, watch or listen to. These top picks will challenge your thinking over the holiday break.

-

The lost the art disagreement

In his keynote at the last Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Stephen Fry told us that “a Grand Canyon has opened up in our world and the crack grows wider every day. As it widens, enemies speak more and more incontinently about the other side.” Within this great fissure lies the lost art of disagreement. Hear how Fry suggests we begin to navigate through a world of seemingly opposing ideas.

-

Curb immigration, curb growth

Our cities are overcrowded, and our ecosystems are degrading at a rapid rate. Is population growth to blame? This year’s first IQ2 Debate: Curb Immigration, heard from environmental scientist Dr Jonathan Sobels, journalist Satyajet Marar, counter terrorism expert Dr Anne Aly and urban planner Professor Nicole Gurran. Watch the debate and hear their perspective on issues from urban planning and government policy, to environmental impacts and economic advantages.

-

An age of anger

Anarchy, resentment and the urge to smash the system seem to be spreading. What caused us to become so angry? How can we understand and navigate interactions with those who are? Author and academic Pankaj Mishra explains why society seems to be so quick to become outraged, and how transformative thinking might solve the epidemic.

-

Politics and populism

We are seeing a rise of nationalism, racism and authoritarian regimes across the world. Will democracy survive the new decade? At last year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas Niall Ferguson contemplated the future of populist movements. Pankaj Mishra, Angela Nagle and Tim Soutphommasane joined a panel to explore if freedom is just too heavy a burden in the new world in the ‘Rehearsal for Fascism’.

-

Masculinity is not so fragile

Following the fallout of the #MeToo movement, many men feel that masculinity is unfairly under attack. David Leser, Zac Seidler, Raewyn Connell and Cath Lumby joined our IQ2 debate: Masculinity is it really so fragile, to share their views on modern masculinity and unpack the dangers or virtues of male normative behaviour.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas returns in 2020, bringing a host of big thinkers and new perspectives to the dangerous issues we face. Gift vouchers are on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Agree to disagree: 7 lessons on the ethics of disagreement

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

How to have a conversation about politics without losing friends

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does ethical porn exist?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 17 DEC 2019

Todd Phillip’s Joker has left audiences around the world outraged, moved and confused with its rewriting of the comic book lore surrounding The Joker.

The film tells the story of Arthur Fleck, a downtrodden man with an unspecified mental illness and an uncontrollable tendency to burst out laughing – whose treatment by society leads him down the path of moral nihilism and violence until he becomes the infamous Clown Prince of Crime.

It has received its share of controversy. Joker won the prestigious Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, is receiving early Oscar Buzz and has clocked over $850 million in the worldwide box office.

It’s also been heavily criticised for being overly sympathetic to the perpetrators of mass violence. Many critics Fleck’s turn from reserved, alienated performing clown to theatrical mass murderer as analogy for the lives of a number of real-world mass shooters.

Couple this with Joker’s depiction of systemic social forces, not individual people, as the true villains of our time, and it can be argued that the film offers an apology for people who use violence – often against women and people of colour – as a way of expressing their dissatisfaction with a world that hasn’t given them what they want.

The film is shot from Fleck’s perspective, and therefore casts huge doubt on what is real and what’s just happening in Fleck’s mind. Not long after watching it, I found myself trying to piece it all together. Did the climactic final act actually happen?

The genius and mischief of unreliable narrator motifs – think of Inception for example – is that we find ourselves looking for a definitive reading, but none exists. Not even the director is able to close the debate – theirs is just another interpretation.

Interestingly, the unreliable narrator question in Joker serves as a handy metaphor for broader confusion about the ethics and politics of the film. If the critical commentary and public discourse are anything to go by, the film left audiences confused not only about the reality of the story, but about its morality as well.

And here’s the central rub with Joker as a political and ethical challenge. It’s rife with ambiguity. What does it stand for? Who is the villain and who – if anybody – is the hero? Are we meant to empathise with Fleck or judge him? Should we join the masses in being furious at the uber-rich and uber-callous Thomas Wayne, or should we be concerned at the accelerating rate of violence?

Just like we don’t know for sure what was in Fleck’s mind and what really happened in the film, it’s hard to know what the film wants us to think about the events of Joker.

Warner Bros themselves tried to pre-load people’s expectations of the film by saying “make no mistake: neither the fictional character Joker, nor the film, is an endorsement of real-world violence of any kind. It is not the intention of the film, the filmmakers or the studio to hold this character up as a hero.”

Despite this effort, most viewers will have arrived at the film with pre-conceived ideas, because the critical conversations around Joker have been relentless. From the first trailers released and a leaked script, people have been speculating about the political effects it would have. Some critics – even some who think the film has artistic merit – wonder if it should have been made.

There is something interesting going on here. On the one hand, we have people experiencing Joker in wildly different ways. On the other hand, we have critics – and the film developers – moulding people’s views of the film before they’ve even seen it.

Then we have the film itself, which is concerned with how easy it is for people to get swept up in movements. How quickly agency can be taken away. And how recklessly people can fight to reclaim that agency.

In Joker, Fleck is entirely without agency. He can’t control his random outbursts of laughter, he can’t make himself understood to his stand-up audiences and even as he begins to embrace his Joker identity, many of the systemic impacts of his actions aren’t through his design. When Fleck does try to seize some agency over his life, he – like the lower-class Gothamites who burn their city in violent riots – does so recklessly, callously and irresponsibly.

Zooming out to the discourse around the film, you can see life mirroring art. Audiences have been systematically deprived of the agency they need to form their own views around the film.

This happened well before the first trailer dropped. Arguably, it began with the rise of comic book movies more generally.

We live in an age where it’s easy to treat films as just another form of content. Just like we binge through streaming services and mindlessly scroll social media feed, we can let films wash over us without ever actively engaging with the material. Sure, we follow the plot and might have a view on whether we enjoyed the film or not, but that’s not the same as allowing a film (or a series, or whatever) to make us think.

The comic book movie is the embodiment of this trend. The heroes and villains are mapped out in advance. We know what will happen and we watch to find out how it will happen. Consider Avengers: Endgame. We knew Thanos would be defeated and that the heroes who had been snapped out of existence would return – after all, a bunch of them already had sequels in the calendar. There’s no moral ambiguity; just a good story.

Of course, that’s fine. The Marvel Cinematic Universe makes up for in fun what it lacks in moral complexity. But Joker is different. Despite appearing in the guise of a comic book film, it’s not a comic book movie at all. It didn’t need to be about the rise of The Joker. What that’s highlighted is how a generation raised on comic book movies have been left unprepared to engage with a film so rife with complexity.

Many are still trying to do so. Like Immanuel Kant encouraged in ‘What is Enlightment?’, they’re daring to think for themselves. Kant saw this enlightenment as liberating – a freedom from intellectual immaturity. But it might also be reckless – particularly if it ends up with people decided that Warner Bros are wrong and Fleck is the hero of the story.

But the best way to guard against this isn’t to avoid films like Joker, or to be too heavy-handed in how people interpret the film. It’s to create more space in our content consumption for things that are more than just fairy floss for our brains. To put the Iron Mans and Flashes of the world in their proper place and find some balance so that we can enjoy the fun for what it is without dulling our senses when something more complex comes along.

The Ethics Centre is presenting a panel discussion on The Ethics of Art and Violence at the MCA on 12 February. Tickets on sale now. For further information click here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Explainer: Getting to know Richard Branson's B Team

Explainer: Getting to know Richard Branson’s B Team

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance Cris 5 DEC 2019

If you ever dreamed of rubbing shoulders with the brightest shining stars of business, you probably couldn’t turn down an invitation to join Richard Branson’s B Team.

The team of luminaries was launched by the Virgin Group founder in 2013 to power a movement to use business to build a better world.

Its goals

The B Team aims to “confront the crisis of conformity in leadership”.

“We need bold and brave leaders, willing and able to transform their own practices by embracing purpose-driven and holistic leadership, with humanity at the heart, aligned with the principles of sustainability, equality and accountability,” according to its website.

“Plan A – where business has been motivated primarily by profit – is no longer an option. We knew this when we came together in 2013. United in the belief that the private sector can, and must, redefine both its responsibilities and its own terms of success, we imagined a ‘Plan B’ – for concerted, positive action to ensure business becomes a driving force for social, environmental and economic benefit.

“We are focused on driving action to achieve this vision by starting ‘at home’ in our own companies, taking collective action to scale systemic solutions and using our voice where we can make a difference.”

Membership

Aside from Branson himself, who has charisma to burn, his hand-picked team of leaders include:

- Co-founder and former Puma chair, Jochen Zeitz

- Chairman & CEO of Kering, François-Henri Pinault

- Chairman Emeritus, Tata Sons, Ratan Tata

- Chairman, Yunus Centre, Professor Muhammad Yunus

- General Secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation Sharan Burrow

- President and CEO, Mastercard, Ajay Banga

- Founder and CEO of Thrive Global, Arianna Huffington

- Former Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Dow Chemical and DowDuPont, Andrew Liveris

Its influence

Branson is a master of marketing, and has long cultivated an image of a fun-loving, brilliant, rule-breaking entrepreneur with a socially-responsible heart. He has launched around 400 companies and has become one of the world’s most influential leaders, with a personal wealth estimated at $7.7 billion.

A stay at his luxury resort Necker Island in the British Virgin Islands is the modern-day equivalent of Charlie Bucket’s “golden ticket” to the chocolate factory (from the Roald Dahl children’s book). It was, for instance, the first holiday destination for the Obama family after they left the White House in 2017.

Branson has long harnessed his star power to humanitarian ventures and he has now provided B Team “vehicles” for others to do the same.

Its projects

The B Team has three causes:

Climate: committing to a just transition to net-zero emissions by 2050.

Workplace equality: creating working environments that recognise and respect the human rights and talents of all people.

Governance: raising the bar on what good governance looks like – and keeping accountability, sustainability and equality at the centre of these efforts.

Recent achievements

At the UN Climate Action Summit in September, B Team Leader and Allianz CEO Oliver Bäte led a group of 12 asset owners with $A3.5 trillion in assets under management in committing to net-zero emissions by 2050—a target aligned with a pathway to 1.5°C warming – and helping companies within their portfolios to achieve the same goal. They join the 87 companies who also made this commitment.

In 2015, The B Team was instrumental in ensuring that a commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050 was included in the text of the Paris Agreement.

In Australia

The local arm of the B Team launched in October 2018 and includes Branson, Sharan Burrow as vice-chair, ANZ Bank chair David Gonski as co-chair, and Chief Executive Women director Lynette Mayne as co-chair. Other members are:

- Scentre Group CEO Peter Allan

- Suncorp Group CEO Michael Cameron

- Former Chairman and CEO of Dow Chemical, Andrew Liveris

- CEO of MLC, Geoff Lloyd

- CEO of Mirvac Susan Lloyd Hurwitz

- Australian Council for International Development president Sam Mostyn

- Chairman of the Light Warrior Group Radek Sali

- Executive Chairman of Carnival Australia Ann Sherry

- EnergyAustralia managing director Catherine Tanna.

MLC’s Lloyd says the group aims to use the power of its influence to make the conversations “go viral”.

“It is about a core group of leaders who will represent those principles and drive those initiatives and connect through to the global B Team. We are trying to create a conversation and lead that conversation through the individuals in those businesses that are part of it.

“The principles are really all there to help leaders lead their businesses and provide a course, if you like, direction, some guidance as to how we should think very differently about work.

“There is a community expectation that business is there to do good.”

The 100% Human project

This initiative brings together more than 150 organisations around the world to shape and identify the elements that define a 100% Human organisation: respect, equality, growth, belonging and purpose. The aim is to recruit to the cause one million companies globally.

100% Human has been collecting examples of innovative thinking in its published Experiments Collection, which provides details of around 200 workplace initiatives, which are trying out new ways of working. These “experiments” include: providing opportunities for refugees and migrants; championing diversity, inclusion and belonging; and supporting employees’ mental health and wellbeing.

The initiative was launched in Australia in June, 2019 with the five principles of: strategically planning for technology, creating career growth opportunities, focusing on the whole person, establishing support networks, and being publicly accountable.

The former CEO of Perpetual Ltd, Lloyd joined MLC Wealth a year ago to engineer its separation from the National Australia Bank. He says he introduced some of 100% Human’s leadership philosophies to Perpetual in 2015 and is now using them to help develop a new, individual workplace culture at MLC.

“At MLC, we’re reviewing all of our people processes and policies and aligning our culture towards that of allowing people to be 100% human at work,” he says. “So, that’s from our leave policies, our carer leave, our flexibility, the way in which we lead ourselves, the way in which our leadership team really do express, and understand that our team have complex lives and needs.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: How to approach differing work ethics between generations?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Beyond the shadows: ethics and resilience in the post-pandemic environment

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

John Elkington on business sustainability and ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Volt Bank: Creating a lasting cultural impact

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY Cris

Pay up: income inequity breeds resentment

Pay up: income inequity breeds resentment

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith Cris 5 DEC 2019

Public outrage over multi-million dollar CEO salaries will never go away when employees are underpaid. It offends our sense of fairness and the increasingly threadbare notion of Australia as an egalitarian nation.

This point is not lost on many who read about Woolworths’ admission it underpaid nearly 6,000 staff over ten years by a total $300 million.

The supermarket chain had failed to account for the actual hours that staff were working, with out-of-business-hours work patterns attracting penalty rates, which were not being added to their salaries.

Other companies which have been caught out with similar underpayments include Qantas, ABC, Commonwealth Bank, Bunnings, Super Retail Group and Michael Hill Jewellers.

While some business leaders laid blame on the complexity of modern awards, Fair Work Ombudsman, Sandra Parker said employers were at fault with “ineffective governance combined with complacency and carelessness toward employee entitlements”.

Human resources leader, Alec Bashinsky, was succinct in his response: “This is 101 stuff and not acceptable in any scenario”. For 14 years, Bashinsky was Asia Pacific talent leader for Deloitte, which employed more than 3,000 people in Australia alone.

Revelations such as the underpayments just add more fuel to the conflagration of distrust and anger, which has led to the rise of anti-establishment political movements around the world.

In Australia, it builds on a mountain of evidence of businesses behaving badly, following revelations of the deliberate underpayments and worker exploitation in the franchising sector and the litany of unethical decision-making unearthed in the recent Royal Commission into financial services.

CEO’s get richer, worker pay stagnates

While company reputations have been trashed over the past couple of years, business leaders have continued to prosper. Company boards responded to public resentment over CEO salaries by reducing the pay of incoming CEO’s… while handing out the second-biggest bonuses of the past 18 years.

Thanks to those bonuses, the median realised pay for an ASX100 CEO reached $4.5m in the last financial year, according to a report by the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors.

Leaders whose companies were directly involved in recent scandals have been punished. Big bank CEO’s saw their remuneration fall over the past year. However, total remuneration for top 50 CEO’s increased by 4 per cent on average, compared to general wage growth at 2.2 per cent, according to the Australian Financial Review.

Macquarie Bank’s Shemara Wikramanayake was the highest paid with $18 million, followed by Goodman Group’s Gregory Goodman with $12.8 million.

Labor MP and economist, Andrew Leigh says the growing gap between the leaders and the led poses a threat to the Australian ethic of egalitarianism.

“Australia is a country where we don’t have private areas on the beaches, we like to say ‘mate’ rather than ‘sir’, we sit in the front seat of taxis and we don’t stand up when the prime minister enters the room,” says Leigh, who is also Deputy Chairman of the Parliamentary Economics Committee.

Former chairman of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, Allan Fels, has written: “The increase in pay levels for CEO’s has occurred at a time when public trust in business is at a low ebb and wages growth in the broader economy can best be described as anaemic”.

The rising levels of income inequality create serious social harm, according to the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS).

Someone in the highest one per cent now earns more in a fortnight than someone in the lowest 5 per cent earns in an entire year.

“Excessive inequality in any society is harmful. When people with low incomes and wealth are left behind, they struggle to reach a socially acceptable living standard and to participate in society. This causes divisions in our society,” according to ACOSS, after the release of its Inequality in Australia report in July.

“Too much inequality is also bad for the economy. When resources and power are concentrated in fewer hands, or people are too impoverished to participate effectively in the paid workforce, or acquire the skills to do so, economic growth is diminished.”

Reining in the excesses

Investors have a mechanism to act if they believe boards have been overly-generous in executive remuneration. In 2018, 12 companies in the ASX200 had shareholders vote down board remuneration reports in a “first strike” action. A further seven were close to experiencing a first strike.

According to the “two-strike rule”, if subsequent remuneration reports are voted down by at least 25 per cent of shareholders, the board positions may be subject to a spill motion. At this point, no company has experienced a board spill as a result of this rule.

The two-strike rule came into effect in 2011 after a Productivity Commission Inquiry into Executive Remuneration found that executive pay went up over 250 per cent from 1993 to 2007.

Labor went into the last Federal election with a policy aimed at encouraging more moderation in executive pay, requiring companies to publish the ratio of the CEO remuneration to the median workers’ pay.

At present, ASX-listed companies have to publish their policies for determining the nature and amount of remuneration paid to key management personnel. However, without a requirement to divulge what the median worker is paid, a ratio cannot be calculated.

The United Kingdom and the United States have both introduced new regulation to require their biggest listed companies to divulge and justify the difference between executive salaries and average annual pay for their employees.

This is going to put more pressure on CEO salaries as the public gets a clear picture. Research in the US shows, for instance, that the average person thinks the pay ratio is 30:1 when the average is actually closer to 300:1.

Those disclosures can have material impacts on a business. The US city of Portland has imposed a 10 per cent tax surcharge on companies with top executives making more than 100 times what their median worker is paid and a 20 per cent surcharge if pay gaps exceed 250 to one.

Leigh says the top 50 CEO’s in Australia are now earning packages at a ratio of around 150 or 200 of median wages in their organisations.

“Those ratios are truly out of whack. If you go back to the 1950s, and 1960s, workers at Australia’s largest firms could earn in a decade what the CEO earned in a year.

“Now, it would take multiple careers for workers in many firms to earn what the CEO earns in a year.”

Setting a fair pay formula

When you have these two issues running concurrently – ever-rising CEO pay and underpayment of workers – it seems appropriate to take a new look at what fair pay looks like.

Some companies have tried to ensure fairness by setting CEO pay as a multiple of the salary of an organisation’s lowest-paid worker.

Mondragon is a Spanish co-op famous for its egalitarian principles. Its CEO is paid nine times more than what its lowest-paid worker earns. In comparison, the CEO of an average FTSE 100 company is paid 129 times what their lowest-paid worker earns.

Mondragon is not well-known in Australia, but is a vast global enterprise, employing more than 75,000 people in 35 countries and with sales of more than Euro12 billion per year – equivalent to Kellogg or Visa.

US ice cream company Ben & Jerry’s took inspiration from Mondragon, setting a five-to-one salary ratio when it started in 1985.

Writing in their book Ben Jerry’s Double Dip: How to Run a Values Led Business and Make Money Too, the founders Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield say: “The compressed salary ratio dealt with an issue that’s at the core of people’s concerns about business and their alienation from their jobs: the people at the bottom of the ladder, the people who do all the actual physical work, are paid very poorly compared to the people at the top of the ladder.

“When we started our business, we were the people at the bottom. That’s whom we identified with. So we were happy to put into place a system whereby anytime the people on the top of the organisation wanted to give themselves a raise, they’d have to give the people on the bottom a raise as well.”

Ben & Jerry’s kept that arrangement in place for 16 years but, when Cohen wanted to retire, attracting a replacement CEO meant raising the rate to a seven-to-one ratio.

“ … as the company grew, the salary ratio became problematic. Some people in upper-level management believed that we couldn’t afford to raise everyone’s salaries, and the salary ratio was, therefore, limiting the offers we could make to the top people we could recruit,” wrote the founders in 1998.

“Other people – Ben included – thought money wasn’t the problem, and that we’d always had problems with our recruitment process. Ben points out frequently that eliminating the salary ratio, which we did in 1995, has not eliminated our recruiting problems.”

The New Zealand Shareholders Association has also called (in 2014) for CEO base pay to be capped at no more than 20 times the average wage.

Fairness is important to us

Leigh, who wrote a book Battlers and Billionaires on inequality, says people naturally benchmark themselves against those around them: “That is how we figure out what we are worth”.

The point is that people care less about the dollar figure they are paid than they do about how it compares to others. If they think it is unfair, their attitude at work and motivation suffers.

“People work less hard when they feel they have not been adequately recognised within the firm,” says Leigh.

Pay transparency – making salaries public knowledge – can be a two-edged sword. People further down the “pecking order” feel worse when they see how others are paid more. However, people should be able to find out where they stand and what they need to do to climb the salary ladder.

“If you are running a firm where the pay structure is only sustainable because you are keeping it secret, then you are walking on eggshells. Ultimately, good managers should be able to be transparent with their staff. Secrecy shouldn’t be a way of doing business,” says Leigh.

“If you are playing football with David Beckham, you don’t begrudge the fact that David Beckham is pulling in a higher salary package than you. The problem arises when there are inequities that aren’t related to performance.

“People are comfortable with the fact that a full-time worker will earn more than a part-time worker, that someone who has another 20 years’ experience gets rewarded for that experience. But, if you are being paid more just because you are family friends with the CEO or you share the same race as the CEO or the same gender, then that is not fair.

“So pay transparency can produce fairer workplaces.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Does Australian politics need more than just female quotas?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Workplace ethics frameworks

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Productivity isn’t working, so why not try being more ethical?

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY Cris

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 5 DEC 2019

This article was written for, and first published by The Guardian. Republished with permission.

Once technology is released, it’s like herding cats. Why do we continue to let the tech sector manage its own mess?

We haven’t yet seen a clear frontrunner emerge as the Democratic candidate for the 2020 US election. But I’ve been interested in another race – the race to see which buzzword is going to be a pivotal issue in political reporting, hot takes and the general political introspection that elections bring. In 2016 it was “fake news”. “Deepfake” is shoring up as one of the leading candidates for 2020.

This week the US House of Representatives intelligence committee asked Facebook, Twitter and Google what they were planning to do to combat deepfakes in the 2020 election. And it’s a fair question. With a bit of work, deepfakes could be convincing and misleading enough to make fake news look like child’s play.

Deepfake, a portmanteau of “deep learning” and “fake”, refers to AI software that can superimpose a digital composite face on to an existing video (and sometimes audio) of a person.

The term first rose to prominence when Motherboard reported on a Reddit user who was using AI to superimpose the faces of film stars on to existing porn videos, creating (with varying degrees of realness) porn starring Emma Watson, Gal Gadot, Scarlett Johansson and an array of other female celebrities.

However, there are also a range of political possibilities. Filmmaker Jordan Peele highlighted some of the harmful potential in an eerie video produced with Buzzfeed, in which he literally puts his words in Barack Obama’s mouth. Satisfying or not, hearing Obama call US president Trump a “total and complete dipshit” is concerning, given he never said it.

Just as concerning as the potential for deepfakes to be abused is that tech platforms are struggling to deal with them. For one thing, their content moderation issues are well documented. Most recently, a doctored video of Nancy Pelosi, slowed and pitch-edited to make her appear drunk, was tweeted by Trump. Twitter did not remove the video, YouTube did, and Facebook de-ranked it in the news feed.

For another, they have already tried, and failed, to moderate deepfakes. In a laudably fast response to the non-consensual pornographic deepfakes, Twitter, Gfycat, Pornhub and other platforms quickly acted to remove them and develop technology to help them do it.

However, once technology is released it’s like herding cats. Deepfakes are a moving feast and as soon as moderators find a way of detecting them, people will find a workaround.

But while there are important questions about how to deal with deepfakes, we’re making a mistake by siloing it off from broader questions and looking for exclusively technological solutions. We made the same mistake with fake news, where the prime offender was seen to be tech platforms rather than the politicians and journalists who had created an environment where lies could flourish.

The furore over deepfakes is a microcosm for the larger social discussion about the ethics of technology. It’s pretty clear the software shouldn’t have been developed and has led – and will continue to lead – to disproportionately more harm than good. And the lesson wasn’t learned. Recently the creator of an app called “DeepNude”, designed to give a realistic approximation of how a woman would look naked based on a clothed image, cancelled the launch fearing “the probability that people will misuse it is too high”.

What the legitimate use for this app is, I don’t know, but the response is revealing in how predictable it is. Reporting triggers some level of public outcry, at which suddenly tech developers realise the error of their ways. Theirs is the conscience of hindsight: feeling bad after the fact rather than proactively looking for ways to advance the common good, treat people fairly and minimise potential harm. By now we should know better and expect more.

“Technology is a way of seeing the world. It’s a kind of promise – that we can bring the world under our control and bend it to our will.”

Why then do we continue to let the tech sector manage its own mess? Partly it’s because it is difficult, but it’s also because we’re still addicted to the promise of technology even as we come to criticise it. Technology is a way of seeing the world. It’s a kind of promise – that we can bring the world under our control and bend it to our will. Deepfakes afford us the ability to manipulate a person’s image. We can make them speak and move as we please, with a ready-made, if weak, moral defence: “No people were harmed in the making of this deepfake.”

But in asking for a technological fix to deepfakes, we’re fuelling the same logic that brought us here. Want to solve Silicon Valley? There’s an app for that! Eventually, maybe, that app will work. But we’re still treating the symptoms, not the cause.

The discussion around ethics and regulation in technology needs to expand to include more existential questions. How should we respond to the promises of technology? Do we really want the world to be completely under our control? What are the moral costs of doing this? What does it mean to see every unfulfilled desire as something that can be solved with an app?

Yes, we need to think about the bad actors who are going to use technology to manipulate, harm and abuse. We need to consider the now obvious fact that if a technology exists, someone is going to use it to optimise their orgasms. But we also need to consider what it means when the only place we can turn to solve the problems of technology is itself technological.

Big tech firms have an enormous set of moral and political responsibilities and it’s good they’re being asked to live up to them. An industry-wide commitment to basic legal standards, significant regulation and technological ethics will go a long way to solving the immediate harms of bad tech design. But it won’t get us out of the technological paradigm we seem to be stuck in. For that we don’t just need tech developers to read some moral philosophy. We need our politicians and citizens to do the same.

“At the moment we’re dancing around the edges of the issue, playing whack-a-mole as new technologies arise.”

At the moment we’re dancing around the edges of the issue, playing whack-a-mole as new technologies arise. We treat tech design and development like it’s inevitable. As a result, we aim to minimise risks rather than look more deeply at the values, goals and moral commitments built into the technology. As well as asking how we stop deepfakes, we need to ask why someone thought they’d be a good idea to begin with. There’s no app for that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

On plagiarism, fairness and AI

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

Explainer, READ

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Taking the bias out of recruitment

Taking the bias out of recruitment

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith Cris 5 DEC 2019

When recruiters sift through job applications, they take less than 10 seconds to decide whether someone will be lucky enough to get through to the next round. If your CV doesn’t grab their attention immediately, you’re done.

“Millions of people are getting hired and fired every single day,” says Kate Glazebrook, CEO and founder of the Applied recruitment platform.

“And if you look at your average hiring process, it involves usually 40 to 70 candidates applying to a particular job.”

Decisions made at this speed require shortcuts. They rely on gut feelings, which essentially are a collection of biases. Without even being conscious that they are doing it, recruiters and hiring managers discriminate because they are human, and they are in a hurry.

Glazebrook says most hiring decisions are made in the “fast brain”, which is fast, instinctive and emotional. “That’s the automatic part of our brain, the part of the brain uses fewer kilojoules so we can make hot, fast decisions,” she says.

“We’re often not even aware of the decisions we take with our fast brain.” The fast brain/slow brain concept references work by Nobel Prize-winning psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman, who studied cognitive biases.

The “slow brain” refers to thought processes that are slower, more deliberative and more logical.

“And I think it’s clear that when you’re 69 candidates down, it’s 5pm on a Friday, you’re definitely less likely to be using your slow, deliberative part of your brain, and much more likely to be using your fast brain,” Glazebrook says.

‘We all overlook people who don’t look the part’

The inherent biases in traditional recruitment practices go some way to explaining the slow and limited progress of diversity and inclusion in our organisations.

“There’s, sadly, lots of meta-analyses showing just how systematically we all overlook people who don’t tend to look the part,” she says. “And there’s evidence to suggest that minority groups of all kinds are overlooked, even when they’re equally qualified for the job.”

Bias against people with non-Anglo sounding names was famously demonstrated in an Australian National University study of 4,000 fictitious job applications for entry-level jobs.

“To get as many interviews as an Anglo applicant with an Anglo-sounding name, an Indigenous person must submit 35 per cent more applications, a Chinese person must submit 68 per cent more applications, an Italian person must submit 12 per cent more applications, and a Middle Eastern person 64 per cent more applications,” wrote the authors of the 2013 study.

Lack of diversity is a business risk. According to Applied, diverse teams bring different ideas to the table, so that teams don’t approach problems in the same way. This tends to make diverse teams better at solving complex problems.

Consequently, an increasing number of employers are committing to “anonymised recruiting”. Also known as “blind recruitment”, this process removes all identifying details from a job application until the final interviews.

In the initial candidate “sifting process”, recruiters and hiring managers do not know the name, gender, or age of the applicants. They can also not make any judgements based on the name of the university or high school the applicants attended or their home address.

When the State Government of Victoria trialled anonymised recruiting for two years, it discovered overseas-born job seekers were 8 per cent more likely to be shortlisted, women were 8 per cent more likely to be shortlisted and hired, and applicants from lower socio-economic suburbs were 9.4 per cent more likely to progress through the selection process and receive a job offer.

According to academics researching the trial, “… at the Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance we found that before de-identifying CVs men were 33 per cent more likely to be hired than women. After de-identification, this flipped and women were eight per cent more likely to be hired than men”.

Connecting to brain function

Glazebrook is an Australian-born behavioural economist working in the UK’s Behavioural Science Team, when she co-founded Applied in 2016 with Richard Marr. They aimed to use their understanding of how the brain works to offer a beginning-to-end anonymised hiring.

Applied runs the whole process, from crafting bias-free job specifications and advertising, to candidate testing and selection. Beyond removing identifying details, the company also breaks up assessment tasks among a team of people and randomises the order in which elements are looked at – to minimise the impact of other cognitive biases.

Applied’s clients include the British Civil Service, Penguin Random House and engineering firm the Carey Group. In the past three years, the company has dealt with more than 130,000 candidates.

“We’ve seen a two to four times increase in the rate at which ethnically diverse candidates are applying to jobs and getting jobs through the platform,” she says.

More than half of the candidates who have received job offers are women and there have been “significant uplifts” in diversity in other dimensions, such as disability and economic status.

Glazebrook says US companies spend $US8 billion annually on anti-bias, diversity and inclusion training. However, even with the best intentions of everyone involved, it seems to have limited effectiveness.

“The rate of change is quite slow,” she says.

There is even some evidence that anti-bias training can backfire. Glazebrook says a concept called moral licensing is a concern: “Once you do the training, you tick a box in your brain that says ‘Great. I’m de-biased. Excellent. Moving on’.

“And, actually, you are free to be more biased than you were before because we’re led to believe we have overcome that particular bias,” she says.

Studies show companies openly committed to diversity are as likely to discriminate as those who aren’t.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Should corporate Australia have a voice?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Getting the job done is not nearly enough

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Beyond the shadows: ethics and resilience in the post-pandemic environment

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights