If you condemn homosexuals, are you betraying Jesus?

If you condemn homosexuals, are you betraying Jesus?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 3 JUL 2019

The controversy surrounding Israel Folau’s Instagram posts has tended to focus on questions of free speech, religious freedom and employers’ rights. But I want to ask a deeper question: is Folau’s position consistent with the teachings and example of Christianity’s founder, Jesus of Nazareth?

In thinking about how one might answer this question, I make the following assumptions:

- that, as the incarnation of the divine, Jesus was incapable of error;

- that Jesus’s life and teachings are the ultimate source of authority for Christians;

- that the words and deeds of Jesus, as recorded in the four canonical Gospels, take precedence over those of any other theologian or interpreter (including Paul the Apostle); and

- that the New Testament has priority over the Old Testament ― to the extent that there is any disagreement.

So, what is the essence of Jesus’s life and teaching as revealed in the Gospels? Traditionally, the focus has been on Jesus’s offer of unconditional love and the associated blessing of healing ― both physical and spiritual (the latter through forgiveness of sins).

Jesus does not present himself as breaking with Judaism. He says explicitly that he has not come to overturn the Mosaic Law of his Jewish forebears, but to bring it to its fulfilment, to reveal its essence. On two occasions ― during the Sermon on the Mount and at the Last Supper ― Jesus speaks directly of the core principles on which the Torah is founded. On the earlier occasion, Jesus explicitly states that all of the law is expressed in the two “greatest” commandments: to love God with all one’s heart; to love one’s neighbour as oneself.

However, in the Gospel of John, Jesus goes one step further. John writes that, at the Last Supper, Jesus presents to his immediate disciples a final encapsulation of all his teaching. Affirming his direct connection with the Father, telling them that he is to ascend to heaven but will send a guide in the form of the Holy Spirit, Jesus issues his disciples with a new commandment. This is what John (13:33-35) reports Jesus to have said:

Whither I go, ye cannot come; so now I say to you. A new commandment I give unto you, That ye love one another; as I have loved you, that ye also love one another. By this shall all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye have love one to another.

Unlike the great commandment, with its appeal to the self-love of each person, the new standard for agape (the non-erotic love one bears for another) is to be Jesus’s love for his disciples ― his friends ― and, presumably, for humanity at large.

If the claims of Christians are to be accepted, then Jesus’s new commandment is not a mere act of prophecy, no matter how inspired. It is not an interpretation of a revelatory experience. If you accept the Gospel of John (as I think Christians do), then Jesus has uttered a direct commandment from God; inscribed not on stone but in the hearts and minds of those present. Jesus’s new law is to “love one another as I have loved you.” How then does Jesus love others?

First, each of the Gospels present Jesus as loving unconditionally. Not once does he set a threshold to be crossed before he bestows his love. He heals people without requiring them to become his disciples. He forgives without first requiring a renunciation of sin. He may counsel a better life, but does not make that a precondition of his love. Indeed, he specifically cautions “the righteous” to avoid judging others ― to refrain from casting the first stone.

This is not to say that Jesus is indifferent to sin. In common with the Jewish tradition, Jesus recognises sin as a form of ‘moral servitude’, a loss of freedom. However, there is nothing in the Nazarene’s ministry that condemns homosexuals to eternal damnation ― nor anyone else. Jesus even prays for the forgiveness of those who have ordered and undertaken his torture at Calvary.

Most importantly, Jesus does not merely tolerate those whom others hold in contempt ― he cosies up to them. He touches them. He shares meals with them. He defies the rituals and customs of ‘purity’, even those prescribed in the Old Testament. In doing so, Jesus offends the prevailing piety and invites the censure of those who withdraw from all that is deemed to be ‘unclean’.

How, then, does Christianity in our time become a religion so quick to judge and condemn, and so reluctant to love others without qualification? How do Christians, like Israel Folau, come to invoke contempt for others, to believe it acceptable to cast the first stone ― from the safe distance of a social media account? Would not a Christian follow Jesus’s example and offer hospitality to those who others treat with disgust ― share a meal, feel their humanity, offer companionship, without any strings attached?

Why, in other words, are many Christians ignoring Jesus? Perhaps interpreters and theologians, like the Apostle Paul, were more eloquent. Perhaps preachers have come to enjoy a measure of success by playing to the underlying prejudices of their audience. Perhaps human beings find it too hard to embrace Jesus’s message of radical love and forgiveness. As Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor explains ― somewhat apologetically ― in The Brothers Karamazov, if Jesus was to walk the earth today, he would have to be destroyed all over again. The world ― including his church – finds Jesus just too difficult to cope with.

Or, perhaps the truth is something darker. Has a deep and ingrained sense of disgust ― about sex in general, and homosexuality in particular ― bound some Christians in chains even stronger than sin?

While I understand that there is no monolithic “Christian” point of view about homosexuality, I am genuinely confused by the notion that any Christian can see matters as Israel Folau does. This is not to doubt the sincerity of Folau and his Christian supporters. But sincerity does not excuse fundamental error.

Surely modern Christians can grasp that a person’s sexual orientation is not something simply chosen. We are born “hard wired” with our preferences. To say that a homosexual person is destined for hell is to claim that each such person is born an abomination in the sight of God. That is an obscene suggestion ― not only in the eyes of a secular society, but, if the Gospels are to be believed, in the eyes of the founder of Christianity itself. Not once does Jesus indicate contempt for any person.

So, again I ask, how is it that a church founded on the commitment to unconditional love has become home to the demons of righteous indignation? In whose name has that been done? Don’t tell me it is Jesus. If unconditional love, free from any condemnation, is offered to the man who nails you to a cross, then how can it be withheld from someone whose only sin is to have not been born a heterosexual?

In the same spirit, perhaps it’s time to call a truce in the proxy war over free speech and religious freedom. It’s time for his detractors to practice what Jesus preached and reach out to Israel Folau; to extend to him friendship and understanding; to share a meal with him and offer him unconditional forgiveness ― for he knows not what he does.

This article was originally published by ABC , republished with permission.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jeremy Bentham

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Double-Effect Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Allan Waddell 27 JUN 2019

The great promise of artificial intelligence is efficiency. The finely tuned mechanics of AI will free up societies to explore new, softer skills while industries thrive on automation.

However, if we’ve learned anything from the great promise of the Internet – which was supposed to bring equality by leveling the playing field – it’s clear new technologies can be rife with complications unwittingly introduced by the humans who created them.

The rise of artificial intelligence is exciting, but the drive toward efficiency must not happen without a corresponding push for strong ethics to guide the process. Otherwise, the advancements of AI will be undercut by human fallibility and biases. This is as true for AI’s application in the pursuit of social justice as it is in basic business practices like customer service.

Empathy

The ethical questions surrounding AI have long been the subject of science fiction, but today they are quickly becoming real-world concerns. Human intelligence has a direct relationship to human empathy. If this sensitivity doesn’t translate into artificial intelligence the consequences could be dire. We must examine how humans learn in order to build an ethical education process for AI.

AI is not merely programmed – it is trained like a human. If AI doesn’t learn the right lessons, ethical problems will inevitably arise. We’ve already seen examples, such as the tendency of facial recognition software to misidentify people of colour as criminals.

Biased AI

In the United States, a piece of software called Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (Compas) was used to assess the risk of defendants reoffending and had an impact on their sentencing. Compas was found to be twice as likely to misclassify non-white defendants as higher risk offenders, while white defendants were misclassified as lower risk much more often than non-white defendants. This is a training issue. If AI is predominantly trained in Caucasian faces, it will disadvantage minorities.

This example might seem far removed from us here in Australia but consider the consequences if it were in place here. What if a similar technology was being used at airports for customs checks, or part of a pre-screening process used by recruiters and employment agencies?

“Human intelligence has a direct relationship to human empathy.”

If racism and other forms of discrimination are unintentionally programmed into AI, not only will it mirror many of the failings of analog society, but it could magnify them.

While heightened instances of injustice are obviously unacceptable outcomes for AI, there are additional possibilities that don’t serve our best interests and should be avoided. The foremost example of this is in customer service.

AI vs human customer service

Every business wants the most efficient and productive processes possible but sometimes better is actually worse. Eventually, an AI solution will do a better job at making appointments, answering questions, and handling phone calls. When that time comes, AI might not always be the right solution.

Particularly with more complex matters, humans want to talk to other humans. Not only do they want their problem resolved, but they want to feel like they’ve been heard. They want empathy. This is something AI cannot do.

AI is inevitable. In fact, you’re probably already using it without being aware of it. There is no doubt that the proper application of AI will make us more efficient as a society, but the temptation to rely blindly on AI is unadvisable.

We must be aware of our biases when creating new technologies and do everything in our power to ensure they aren’t baked into algorithms. As more functions are handed over to AI, we must also remember that sometimes there’s no substitute for human-to-human interaction.

After all, we’re only human.

Allan Waddell is founder and Co-CEO of Kablamo, an Australian cloud based tech software company.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Online grief and the digital dead

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

BY Allan Waddell

Allan Waddell is founder and Co-CEO of Kablamo, an Australian cloud based tech software company.

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 27 JUN 2019

I spent this weekend hearing from all corners what a wonderful Dad I am. It was quite lovely, and I’d very much like for it to happen more often.

This weekend I was effectively a sole parent as my wife was rendered bedridden by illness. For two days, I was in charge of a seven-week-old baby and almost three-year-old toddler.

Miracle of miracles – they didn’t die. In fact, I managed to feed and bath them, plus made sure they slept. I even packed them both up in the car and took them to a birthday party and back again.

An uneven playing field?

This is the Herculean labour that earned me torrents of praise. In fact, it didn’t just earn me praise – people messaged my bed-ridden wife not only with well-wishes, but to tell her how lucky she was. Oh, to have a co-parent like him!

I can’t imagine how frustrating these messages are for her to receive. I spend four days a week at work, which means she has the kids solo for those four days. In that time, she takes them to doctors appointments, libraries, playgrounds, feeds them, does an enormous amount of housework and manages, somehow, to keep herself alive.

What I did this weekend amounts to about 50% of what she does week in, week out. Guess how many people have texted me to say how lucky I am?

Less effort but more praise?

The double-standards here are staggering. They’re also incredibly unfair. To see someone receive more praise for less effort is profoundly invalidating – something about which women have been increasingly outspoken. It also makes social progress difficult – the more we see men’s modest contributions as incredibly generous and praiseworthy, the harder it is for women to ask more (even though what they’re asking for is entirely reasonable – lest we forget the last census, which reports that one in four men do zero housework).

What’s been less widely addressed is just how bad this double-standard is for men. I, and I would imagine most dads, want to be a great parent and partner. But that’s not helped by receiving praise for every little thing I do – it gives a false impression of exactly where I am on the spectrum: am I doing a great job, a terrible one, or just a mediocre one? It’s hard to tell through all the well-intended, generous praise.

Praise can be a double-edged sword

Praise is a powerful tool for behavioural change and moral growth. It can be used to help encourage people to do the right thing, remind them when they’ve slipped up and point out whose behaviour is a good example to follow. But that only works if the people offering praise have a clear idea of what’s actually worth praising – the praise in itself means nothing if it’s not properly calibrated.

And this is why the kind of praise I received is a problem. Taking care of your children is not exceptional, parenting-wise. It’s just what you’re supposed to do. Ditto, doing the laundry, cooking for the family, organising tradesmen to come and fix the house, planning birthday parties and all the other domestic activities that women do thanklessly and men do heroically. Or, at least, some men – again, one in four do no chores.

The sheer mass of men not pulling their weight makes it so easy for mediocrity to look amazing. The comedian Hannah Gadsby talks about how there is a line in the sand between ‘good men’ and ‘bad men’, but how it tends to be men who determine where that line is drawn. Similarly, as a dad I can always find a dad who isn’t doing quite as much as me and use that to determine how much I’m contributing. And, good news, I’m likely to have my self-image reinforced by praise and gratitude at every turn.

What’s more, there’s a social message embedded in that praise. Just as the text message said, women are told they should be grateful to have a partner who is not one of those who does no housework. Maybe he doesn’t do much – but it’s not nothing, so lucky you. Obviously, these narratives are very bad for equality.

They’re also, as I said, very bad for men who want to be great partners, parents and people. The school of ethical thought that most focusses on the kinds of questions I’m asking here is known as ‘virtue ethics’. Virtue ethics focusses on the kinds of character traits that are most likely to make people good and the kinds of activities that are likely to develop and model those characteristics.

Thinking in this way, we might be inclined to say that being a good parent requires the development of a bunch of different character traits – like compassion – and then practising those character traits by, say, holding a child gently while they have an emotional meltdown.

However, one the key ways we learn the virtues is by emulating role models. That means who we single out as role models is really important and – as we’ve said – what counts as ‘exemplary’ parenting can, for dads, be a pretty low bar. Not only does this leave a lot of cleaning up for the co-parents of men who have been sold this story, it undermines their ability to become who they really want to be: great dads.

What do we do about this? Well, for one thing, we should stop giving blokes a cookie just because they showed up. Reserve our praise for when it’s really deserved – and then hand it out equally. Great parenting is great parenting – just because it’s more common to see women in that role doesn’t mean they’re unworthy of praise.

Second, I think men have got to be critical about the kinds of feedback they receive. Before letting it stoke our egos, we need to consider whether or not it’s warranted. In an age of allyship and leaning in, social brownie points are pretty easy to come by for men. But we need to hold ourselves to a higher standard. As the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah writes, “a person of honour cares first of all not about being respected but about being worthy of respect.”

Matt Beard is a tired, okay dad.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethical dilemma: how important is the truth?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When identity is used as a weapon

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Israel Folau: appeals to conscience cut both ways

Israel Folau: appeals to conscience cut both ways

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 26 JUN 2019

Israel Folau’s now infamous post in which he called on a range of “sinners” to repent, turn to Jesus Christ and thus be saved from an eternity in Hell has had more consequences than I suspect he anticipated.

It has led to his loss of employment. It has elevated his status to that of a champion for conservative Christian beliefs.

Finally, it has prompted widespread debate about the intersection between religious belief and the world of work.

It is this last issue that deserves further discussion.

Religious freedom comes in four basic forms: freedom of belief, freedom of worship, freedom to act in good conscience (which includes freedom from coercion in matters of religion) and finally freedom to proselytise (which includes the right to educate one’s children in the faith). Folau’s case involves the third and fourth of these freedoms.

What Folau believes and how he worships have not been challenged. Rather, he has been sanctioned for what he has done and said — not as a believer, but in his role as an elite rugby player representing Australia. However, can the two roles of “believer” and “contracted player” be so easily separated? That is the question at the heart of this issue.

What are Folau’s rights?

As a committed Christian, Folau obviously feels compelled to act on his beliefs — in this case by posting tweets and instagram posts directed at those who risk damnation. Within his world view, he is simply following the scriptural injunction to: “Go into all the world and proclaim the gospel to the whole creation. Whoever believes and is baptised will be saved, but whoever does not believe will be condemned.” (Mark16:15)

So, we might ask if it is right and proper that a person of such sincere religious beliefs has lost his job and been denied at least one platform for fundraising to defend his interests before the courts.

As a general rule, there is only one group of employers — faith groups — who claim a right to dismiss people from employment because of their religious beliefs. For example, a number of religious organisations have argued that their schools should be allowed to deny employment to otherwise competent people who do not practise their religion. It follows from this that employees who renounce the faith of the school would be open to dismissal.

No other employer may discriminate against a person based on their religious beliefs. So, given that rugby is not a religion (despite what some claim), how did Folau come to lose his lucrative employment — a risk that is now faced by his wife, Maria Folau, one of Australasia’s preeminent netball athletes and a Christian who supports her husband’s views?

Brands have a right to protect their interests

In order to broaden the debate, let’s consider the case of a Christian who believes that the Pope is the Antichrist and that Roman Catholics are all destined for Hell. Such views are not “hypothetical”. They were openly held by the Northern Ireland religious and political leader, the Reverend Ian Paisley.

In 1958, he condemned Princess Margaret and the Queen Mother for “committing spiritual fornication and adultery with the Antichrist” after they met with Pope John XXIII. Thirty years later, Paisley denounced Pope John Paul II as the Antichrist — to his face — while the latter addressed the European Union Parliament.

Now suppose an employee is of a mind similar to Paisley — so publishes a tweet attacking the head of the Catholic Church and all of its adherents in equivalent terms. Suppose the employee does so on the basis of what he considers to be a well-founded and sincere religious belief. However, in this case, it’s not just a vulnerable minority group who’s affected — but more than a billion Roman Catholics and their immensely wealthy and powerful church.

Let’s suppose that the “Paisleyite” employee is a prominent brand ambassador working for a major bank. After the tweet, all hell breaks loose. Upset employees threaten to resign, customers threaten to close their accounts, investors begin to dump the stock, etc.

Would an employer be justified in calling such a person to account? Or should the bank respect the expression of sincere, religious belief and defend the right of the brand ambassador to express such views — no matter what damage is done?

It seems reasonable that employers be free to take steps to protect themselves from the kind of strategic risk caused by well-intentioned, loose cannons like the hypothetical brand ambassador sketched above.

This should allow employers to put in place measures designed to protect their interests — and then ask their employees to act accordingly.

Employees have a right to choose too

There is an important point to be noted here. The employer has a right to define how its interests are to be protected. However, it falls to the employee to accept (or not) the relevant conditions of employment.

Any person who truly feels unable to accept those conditions should either not accept an offer of employment or if already part of the organisation, then they should consider resigning in order to find a place of employment better aligned with their moral compass.

This brings us back to the ethical core of the problem raised by the Folau case. Is it ever right for an employer to demand that an employee leave their conscience at the door? I think that the answer is no.

However, if the conscience of an employee should be respected, then so should that of the employer. No individual or organisation is required to be complicit in conduct that it sincerely believes to be wrong.

This is the ground on which Rugby Australia and GoFundMe have both stood. They have decided not to enable the propagation of views that they hold to be ethically objectionable. Rugby Australia’s employment of Folau as one of Australia’s elite sportsmen afforded him (and his views about sin) a prominence that others do not enjoy. They have denied him access to the platform they had provided to him.

Folau was never just a player. He has always been, in part, a brand ambassador. GoFundMe denied Folau its platform after he allegedly violated its terms of service.

Folau chose religion

What both sides of this debate need to consider are the requirements for even-handedness and proportionality. Those who act in the name of conscience — employees and employers — need to be sincere. They need to protect their position with the minimal restrictions necessary. They need to be even-handed — treating like issues and persons in a like manner. And they need to accept the reasonable consequences of their actions.

Folau must have known that labelling homosexuals (among others) as sinners destined for Hell would be incendiary — and risk damaging Rugby Australia.

After all, this was not the first time he had been vocal in his views. In the end, his choice was between what he understood to be his duty to his employer and what he understood to be his duty to his God. Folau chose to put his religion first.

Conscience is not a convenient friend. It often comes with consequences; some good, some ill.

Neither Rugby Australia nor GoFundMe has silenced Folau. He is still acting and speaking in accordance with his religious beliefs. He is still able to raise funds for his defence — as demonstrated by the swift offer of support provided by the Australian Christian Lobby. Folau still has a public platform — which he continues to utilise, as is his right.

Kicked out of the temple, Israel Folau remains free to preach in the public square.

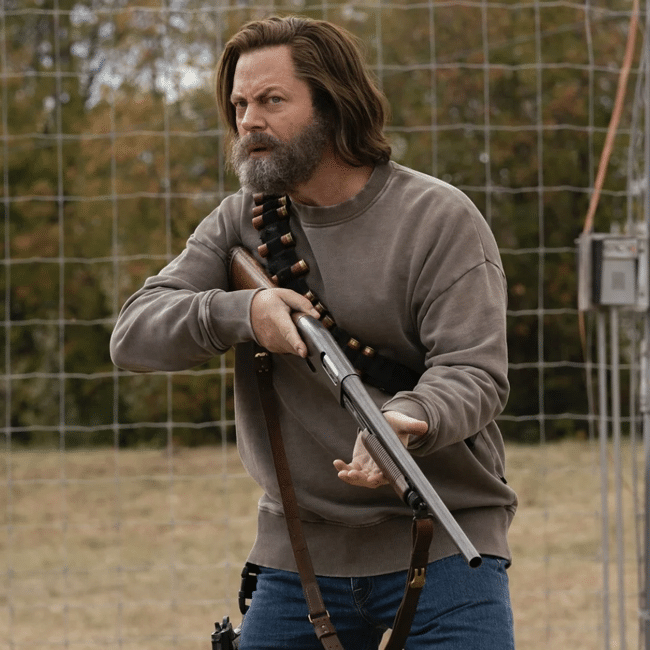

Dr Simon Longstaff originally wrote this piece for ABC News. Photo credit: David Molloy

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

We need to talk about ageism

There’s growing evidence of change afoot in attitudes toward age, ageing and older people and it’s about time.

After decades of pondering – and usually catastrophising – about the impact on society of the dreaded ‘ageing population’, we may just be reaching a tipping point.

This term, tipping point, is described by Malcolm Gladwell in his bestselling book of that title as the “magic moment when an idea, trend, or social behaviour crosses a threshold, tips, and spreads like wildfire”.

US ageism activist, Ashton Applewhite, suggests we might be there. She is the author of This Chair Rocks – A Manifesto Against Ageism and will be visiting Australia in November this year.

“The Guardian has just appointed a Longevity Reporter, for example,” she said, “who interviewed me at length and kept asking whether the culture was at a turning point”.

Applewhite argues most people are looking to cash in on the ‘longevity economy’ by selling products and services to a generation that controls most of the disposable income in the developed world.

“But there are also a zillion conversations going on about intergenerational initiatives, older women coming into our power, teaching medical students about age bias, incorporating age into diversity and inclusion training, fetishising of the old-and-fashionable, and many more domains.”

This is happening because people everywhere are waking up to the fact that no domain – from healthcare, to entertainment, to business, technology, the built environment – will be unaltered by the permanent, global and unprecedented phenomenon of population ageing. It carries fascinating social, economic, and ethical implications.

The big lag

One of the biggest challenges of population ageing stems from the fact that the roles and institutions around us – with all their underpinning assumptions, attitudes and behaviours – were created when lives were shorter and very different. And they haven’t had time to properly catch up.

A coalition of diverse Australian organisations and individuals have committed to address this lag with EveryAGE Counts, a long term advocacy campaign to change these destructive, outdated, yet deeply engrained attitudes and assumptions about ageing and older people. The coalition includes the Australian Human Rights Commission, COTA Australia, National Seniors, the Federation of Ethnic Communities Councils, and the Regional Australia Institute.

“Research shows that many of society’s views about older people – the views and assumptions that drive all the negativity around ageing – are based on outdated myths and stereotypes that simply do not apply in this era of prolonged good health and increased longevity,” says EveryAGE Counts campaign co-chair, Robert Tickner.

“People are being prevented from living the productive, healthy, engaged lives they want to live as they get older because our society tends to devalue and marginalise older people,” he says.

“And these negative stereotypes are so pervasive and deeply ingrained – in our language, in representations in the media and in popular culture – that many of us have bought into them without question. So we actually contribute to our own marginalisation as we grow older. It’s why ageism is often described as prejudice and discrimination against your future self!”

The EveryAGE Counts campaign aims to end ageism. It is working to make it as unacceptable as other forms of prejudice and discrimination in our community.

“Terms like sexism, racism and homophobia are well understood and have become embedded in our societal norms. Ageism is not. Racist, sexist and homophobic behaviours are easy to spot, ageist behaviours, less so,” said Tickner.

Ageism is a bit different to other ‘isms’. Racist or sexist attitudes and behaviours, for example, are usually based on prejudices and assumptions about a person or a group that is ‘different’ to us – a different race, a different gender.

“The great irony is that ageism can affect us all, regardless of race, gender, religion, size, shape or our favourite music! It is discrimination against yourself, albeit your future self, for each and every one of us… should we be fortunate to live beyond our youth,” Tickner said.

There have been some great efforts in the last couple of decades, in Australia and internationally, to raise consciousness levels about ageism and its many negative impacts. Applewhite is trying to do this by urging us to swap ‘women’ for ‘older people’ when thinking about some of our attitudes and assumptions. Would you use a sweeping generalisation for an entire gender? Do you think ‘older people’ who may span 30 to 50 years in age, are all the same?

Many are comfortable calling out racism, sexism or homophobia. Yet jokes about older people are less likely to attract reprimand. I encourage you to check out the EveryAGE Counts campaign, take the ‘Am I Ageist?’ quiz and sign our campaign pledge:

I/we stand for a world without ageism where all people of all ages are valued and respected and their contributions are acknowledged. I/we commit to speak out and take action to ensure older people can participate on equal terms with others in all aspects of life.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Article

Ethics Explainer: Respect

ArticleBeing Human

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Kym Middleton 6 JUN 2019

IQ2 Australia debates whether we need to ‘Stop Idolising Youth’ on 12 June.

Advertisers market to youth despite boomers having the strongest buying power. Unlike professions such as law and medicine, the creative industries prefer ‘digital natives’ over experience.

Young actors play mature aged characters. Yet openly teasing the young for being entitled and lazy is a popular social sport. Are the ageism insults flung both ways?

1. Why do marketers hate old people?

Ad Contrarian, Bob Hoffman / 2 December 2013

An oldie but a goodie. Bob Hoffman is the entertainingly acerbic critic of marketing and author of books like Laughing@Advertising. In this blog post he aims a crossbow at the seemingly senseless predilection of advertisers for using youth to market their products when older generations have more money and buy more stuff.

“Almost everyone you see in a car commercial is between the ages of 18 and 24,” he says. “And yet, people 75 to dead buy five times as many new cars as people 18 to 24.” He makes a solid argument.

2. It’s time to stop kvetching about ‘disengaged’ millennials

Ben Law, The Sydney Morning Herald / 27 October 2017

Ben Law asks, “Aren’t adults the ones who deserve the contempt of young people?” He argues it is older generations with influence and power who are not addressing things as big as the non-age-discriminatory climate crisis. He also shares some anecdotes about politically engaged and polite public transport riding kids.

You might regard a couple of the jokes in this piece leaning toward ageist quips but Law is also making them at his own expense. He points out millennials – the generation to which he belongs and the usual target for jokes about entitled youth – are nearing middle age.

3. Let’s end ageism

Ashton Applewhite, TED Talk / April 2017

There’s something very likeable about Ashton Applewhite – beyond her endearing name. This is even though she opens her TEDTalk with the confronting fact the one thing we all have in common is we’re always getting older. Sure, we’re not all lucky enough to get old, but we constantly age.

In pointing to this shared aspect of humanity, Applewhite makes the case against ageism. This typically TED nugget of feel good inspiration is great for every age. And if you’re anywhere between late 20s and early 70s, you’ll love the happiness bell curve. In a nutshell: it gets better!

4. Instagram’s most popular nan

Baddiewinkle, Instagram/ Helen Van Winkle

Her tagline is “stealing ur man since 1928”. Get lost in a delightful scroll through fun, colourful images from a social media personality who does not give a flying fajita for “age appropriate” dressing or demeanours. Baddie Winkle was born Helen Ruth Elam Van Winkle in Kentucky over 90 years ago.

Her internet stardom began age 85 when her great granddaughter Kennedy Lewis posted a photo of her in cut-off jeans and a tie-dye tee. Now Winkle’s granddaughter Dawn Lewis manages her profile and bookings. Her 3.8 million followers show us audiences aren’t only interested young social media influencers. “They want to be me when they get older,” Winkle says. Damn right we do.

Event info

IQ2 Australia makes public debate smart, civil and fun. On 12 June two teams will argue for and against the statement, ‘Stop Idolising Youth’. Ad writer Jane Caro and mature aged model Fred Douglas take on TV writer Ben Jenkins and author Nayuka Gorrie. Tickets here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Article

Ethics Explainer: Respect

ArticleBeing Human

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

The dark side of the Australian workplace

The dark side of the Australian workplace

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 5 JUN 2019

The founder of a law firm recently explained long working days under high pressure at his firm, saying: “People come here with the knowledge and expectation that they’re going to have to work hard”.

He could have been speaking for any number of employers in high-stress industries.

As young graduates leave university to work in top-tier law firms, in hospitals, merchant banks and professional services, they are already well acquainted with hard work and competition. They have strived to become the best and brightest through many years of education, often polishing their resumes with extra-curricular achievements in sport, music and volunteer work – all the while supporting themselves with part-time jobs.

These young people know what it is like to “burn the candle at both ends”, to run themselves ragged getting ahead of the competition so they can get one of the prized entry-level jobs that may lead to continued success.

They expect to be worked hard. They probably don’t expect to be worked to death.

Two leading law firms have recently been investigated over complaints about “extreme working conditions”, where one solicitor warned that it had reached a “point someone will die or have some other physical or mental health episode’’.

An unprecedented move by WorkSafe

In one well-publicised example, WorkSafe Victoria had launched an investigation into King & Wood Mallesons in Melbourne after a similar complaint regarding overwork and exhaustion, particularly during the Banking and Finance Royal Commission.

King & Wood Mallesons chief executive partner, Berkeley Cox, says the legal industry is paying much closer attention to the issue of work stress.

“We have learnt so much over the past year and recognise that there is a lot more that law firms can and should be doing to improve the everyday work experience for individuals and the systematic issues at an organisational and industry-wide level,” he says.

“While we have much more to do on our journey, we want our workplace to be one where every individual has the opportunity to flourish.”

WorkSafe’s action is regarded as unprecedented in the legal industry and some pundits have nominated it as a “death knell” for the concept of the “billable hour” – whereby firms charge clients for each hour their lawyers work.

The billable hours system means that workers are incentivised to work longer, rather than smarter.

Certainly, the statistics around mental health in the legal profession are alarming.

Around 50 per cent of law students, 33 per cent of solicitors and 20 per cent of barristers report they have experienced depression. Further, 11 per cent of lawyers contemplate suicide each month, according to research published on the website of legal mental health charity, Minds Count (formerly the Tristan Jepson Memorial Foundation).

A punishing rite of passage

Investigating the causes of this crisis and exploring possible solutions usually leads back to an industry culture of being always-available to clients, unreasonable demands for fast turnarounds and the “billable hour”. There is also a long-held belief in the professions that young people will work punishing hours as a “rite of passage” that will pay off in the long run.

In the legal industry, Royal Commissions tend to amp up the pressure, with work going on in 24-hour cycles in 15-hour shifts, seven days per week, in an environment that is intolerant of mistakes or human frailties.

As it is, lawyers work longer overtime than professionals in any other field in Australia, according to a position paper by The Legal Forecast, a not-for-profit group that provides support for students and early-career lawyers.

Under discussion at a recent event, hosted by The Legal Forecast, was the exacting timetabling of the Hayne Royal Commission and the impact it had on lawyers, particularly junior staff.

DLA Piper Australia co-managing partner and Minds Count board member, Melinda Upton, asked: “Was it worth the sacrifice when you look at statistics on people committing suicide and entering depression? Did it have to be done that quickly?”.

This point was picked up by Scarlet Reid, a partner at McCullough Robertson Lawyers, who said she worked on the Hayne Royal Commission and is now working on this year’s Aged Care Royal Commission.

Reid said the Aged Care commission was proceeding at a “much slower pace” and questioned whether the banking Royal Commission really had to be completed in one year.

“Politics drives that as well,” she said. “We could slow down.”

She said many of the organisations involved in giving evidence to the Aged Care Royal Commission were not-for-profits that did not have the funds to pay for large legal teams – a factor that puts a brake on the pace.

Need to slow down

Partner at legal recruitment firm ECP Legal, Justin Whealing, said a senior banking corporate counsel told him he wished the law firms and their clients had teamed up to ask the commissioner for more time.

“I think the legal profession could do that better, in terms of presenting a united front to speak in one voice about how meaningful changes can be made for the betterment of the profession. Clients would get better advice as well and it would be more sustainable for the people in it,” Whealing said. He also advocated having an industry-wide standard, setting out conditions such as maximum work hours and mandatory breaks and using targets.

Reid acknowledged the bind that law firms find themselves in: “It’s very difficult when you’ve got clients needing to meet deadlines, getting into witness boxes. And, you know, it’s a balance”.

Some firms are using contract lawyers to help manage workload over peak times, says the head of Innovation and Project Delivery at Pinsent Masons, Alison Laird. Even without being involved in a Royal Commission, there are huge deadlines that must be met. “So we ramp up the team, and then we ramp them down again,” she says.

Getting rid of ‘billable hours’

Laird said things will not improve until law firms change the way they remunerate their people and get rid of the “billable hour” system, which drives lawyers to bill a certain number of hours per year to the detriment of their mental wellbeing. “It is the one thing that impacts innovation more than anything else,” she says.

At least one top tier firm, Corrs Chambers Westgarth, is dumping the billable hour concept (while adding an extra week of annual leave) and replacing them with annual billing targets, which allow for peaks and troughs of client-billed activity.

However, Melinda Upton warned that replacing the billable hours system cannot happen without the support of clients, who are likely to push back on any change. Member of The Legal Forecast NSW, Edwin Montoya Zorrilla, supports a move away from billable hours and offers more remedies: the automation of various legal tasks and integrating long-term thinking into practice management and recruitment.

“This discussion also includes more specific strategies such as optimising systems of delegation and work sharing, better communication with clients, and using technology-assisted project management tools,” he writes in an article for Westlaw.

“Yet, none of these strategies, however innovative, take effect overnight, and there remains a tendency to return to traditional means of meeting the bottom line.”

Encourage safe work

Upton said it is a responsibility of law firm partners and management to educate the partners about staff wellbeing and “to call it out when they don’t come to the table on it”.

They can also highlight examples where enforcing or encouraging safe work practices has worked well.

“Usually it means your attrition rates have improved, you’ve got a much happier team, you’ve got succession and talent mapping and progression going on, you get good client feedback. And clients really don’t care where you work.”

Reid says working shorter hours may mean that law partners have to accept they will make less money.

When partners discuss remuneration structures at a firm-wide level, they need to be talking about encouraging the sharing of work between teams, the use of contract lawyers and other ways to create a sustainable work environment.

“There is an element of almost a corporate greed associated with the driving of long hours … unless you’re going to change the remuneration structure, then it’s going to be hard to drive behaviour,” she says.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. The Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Measuring culture and radical transparency

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Market logic can’t survive a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The value of principle over prescription

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why the future is workless

Predictions for the future of work are grim – depending on your point of view. Many of our jobs are being automated out of existence, but it looks like we’ll have much more free time.

Writer and Doctor of Philosophy, Tim Dunlop, says people and governments are going to have to rethink how we support ourselves when there isn’t enough paid work to go around.

Dunlop does not ascribe to the view often put forward by economists that technology will generate enough jobs to replace the ones that are destroyed by robotics and artificial intelligence.

“I don’t know if that’s necessarily true in the medium term… I think there’s going to be a really nasty transition for more than a generation,” says Dunlop, the author of Why the Future is Workless and The Future of Everything.

“We are going through this huge period of transition at the moment and we don’t really know where it’s heading. We’re at the bottom of the curve, in terms of what [new technologies] are going to be capable of.”

Dunlop says framing question around the future of work as “will a robot take my job?”, is reductive. Instead, we should be looking at what sort of job will be available and what the conditions will be for the jobs that are offered.

“If we are working less hours, or there is less work, or the economy just needs fewer people, and then we don’t have a technology problem, we’ve got a distribution problem,” he says.

The “hollowing out” of the job market means that middle-skilled jobs are disappearing because they can be automated. Trying to “upskill” people who have been displaced, or redirect them into jobs that need a human touch (such as caring jobs) is not an answer for everyone.

“Not everybody can have a high-skill, high-paid sort of job. You need those middle-level jobs as well. And if you don’t have those, then society’s got a problem.” he says.

Dunlop says one way of addressing the issue is a universal basic income: where everybody gets a standard payment to cover their basic needs.

“I don’t think you can rely on wages to distribute wealth in an equitable way, in the way that might have been in the recent past,” he says.

The idea of a Universal Basic Income has been around since the 16th Century and is unconditional – not based on household income.

In Australia, the single-person pension (now just over $24,000 per annum) might be seen as an appropriate level of payment, according to Dunlop, in an article written for the Inside Story website.

“It is basic also in the sense that it provides an income floor below which no one can fall. The payment is unconditional in that no one has to fulfil any obligations in order to receive it, and even if you earn other income you’re still eligible. That makes it universal, equally available to the poorest member of society as it is to the start-up billionaire,” he writes.

Much of the discomfort often voiced about such a scheme centres around the idea that people are being paid to “do nothing” and that it removes the incentive to work.

However, trials show that in developing countries, people use the money to improve their situation, starting businesses, sending children to school and avoiding prostitution. In Europe and Canada, people receiving the payment tend to stay in their jobs and entrepreneurship increases.

Trials of the Universal Basic Income are now taking place globally – from Switzerland to Canada to Kenya – but most are limited to the unemployed or financially needy, rather than being universal.

Dunlop says that, rather than worrying about whether people “deserve” the payment, we should accept the concept of “shared citizenship”. Whether we do paid work, or not, we are all contributing to the overall wealth of society.

Inequality comes when wealth gets divided up by those who do work that is paid and those who own the means of production. With a Universal Basic Income, everybody’s contribution is valued and people get a benefit from the roles they play in the formal and informal economy, he says.

So what will we be doing in the future if we are not doing paid work? Dunlop says we will still have our hobbies, passions and families – and we can derive just as much (if not more) meaning from those things as we do from our jobs.

We are already seeing evidence of efforts to reduce the hours of work, with companies trying four-day work weeks (paid for five), the Swedish Government trialling a six-hour workday, a French law banning work emails after hours.

Dunlop says a “work ethic” culture makes it hard for these reforms to succeed and unions tend to see a push for reduced hours as a “trojan horse” threat of increasing casualisation and insecure work.

“That’s where things like the French rule about emails probably comes in handy. It sets some parameters around what society sees as acceptable and maybe it needs some government leadership in this area.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

John Elkington on business sustainability and ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The value of principle over prescription

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Fiona Smith 31 MAY 2019

In the wake of the Financial Services Royal Commission, many employers are asking whether they should award bonuses to people who choose to do the right thing.

Boards and CEOs are discussing whether people need an incentive to make ethical decisions and how “ethical incentives” could avoid the risk of encouraging unintended behaviours.

Incentives have a tarnished reputation, with poorly-constructed programs blamed for driving a culture of greed in banks and insurance companies. The international anti-corruption organisation, Transparency International, says performance incentives should not just focus on getting sales, for instance, but also consider how those sales are achieved.

“ … incentive schemes should move beyond mere alignment with values and ethical codes and actively encourage ethical behaviour,” according to the authors of Transparency International’s 2015 report Incentivising Ethics: Managing incentives to encourage good and deter bad behaviour.

“This means that they should not be based solely on financial targets, but should contain non-financial targets that reflect and drive ethical behaviour. Ultimately, this mix of incentives should support the long-term sustainability and success of the company.”

Senior principal advisory at research company Gartner, Arj Bagga, says the Royal Commission has sparked many conversations with his clients, who want to know if they can use ethical behaviour as a measure in the “performance systems” they use to encourage the best work from their people.

A limit on rewards?

Bagga says they can – but within limits. Financial rewards or goods (such as restaurant vouchers) are only effective up to the value of $300, he says.

“Anything over $300 has an incrementally lower benefit on employee performance.”

The reason for this is that financial rewards are an “extrinsic” motivator, meaning that it comes from outside the person, and are much less effective than an “intrinsic” motivator (an inner desire).

“After $300, it starts to extrinsically motivate them too much, whereby they just associate ethical behaviour with financial reward, which is not what you want,” says Bagga.

“You actually want them to be intrinsically-motivated, because, if you remove the reward down the line, because of cost cutting or whatever it might be, employees will then stop acting ethically, just because they’re not being rewarded.

“What we want to do is have a balance between the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.”

Recognition vs cold hard cash

The most intrinsic powerful motivator is recognition – commending people for their ethical behaviour. Such public recognition can increase employee performance by up to 3 per cent, he says.

However, the effect of that recognition can be supercharged by attaching a financial reward “which we found can increase performance by a further 5 per cent”.

While research has shown that the effectiveness of financial rewards can quickly fade, Bagga says the impact of the small reward can be sustained by using ethical behaviour as a measure in performance reviews.

Because their promotions depend on it, people will continue to try to display the desired behaviours, he says.

Making the right choice

A further question is how to identify ethical behaviour, when it is essentially just doing what would be expected of a decent person. Bagga says managers can reward those instances where people make ethical choices in situations where there is no clear answer.

This could be when, for instance, a salesperson sells a product that earns a lower commission, or no commission, but is a better choice for the customer.

Transparency International, while supporting the use of incentives, points out some of the risks around trying to identify and reward ethical behaviour: the measures are subjective, corrupt employees may be convincing actors, not all ethical acts will be recognised which could cause resentment, and discussion about behaviours may lead to some difficult performance review discussions.

Bagga says ethical behaviour is a good business strategy. If organisations can ensure their people recognise what ethical behaviour is, adopt an ethical mindset and then act upon it, they can increase employee performance by up to 12 percent, he says.

Short term pain, long term gain

Some employers may not be sympathetic to the idea their people forego revenue as they look for the best option for customers. However, Bagga says that view would be myopic.

“It may impact you in the very short term but, longer term, it will actually increase your brand awareness in the marketplace and it will increase your ability to attract talent,” he says.

“In Australia, specifically, ethical behaviour is one of the core reasons a person chooses to join an organisation.”

Australian survey respondents rank “ethics” and “respect for the organisation” higher than manager quality and future career opportunity when they are assessing career paths.

Bagga says that it is not just the financial services companies that are interested in the idea of “incentivising” ethical behaviour.

“I’ve also had conversations with mining companies and telecommunications companies, who are trying to get on the front foot of this and make sure they are bullet proofing themselves against any unethical behaviour that could occur in their organisations because they understand, through the Royal Commission, what the implications of those could be on the performance of their business and the perception of their brand.”

Cashless recognition

- Introducing ethics and values measures into performance reviews

- Good ethical conduct being a prerequisite for promotion.

- Spot awards for good ethical practice, recognising special contributions as they occur, usually over a relatively short-term period.

- Awards for people who speak up or challenge questionable conduct.

- Recognition and/or prizes for people who excel in ethics and compliance training.

- Recognition for outstanding contribution to the ethics and compliance programme.

- A company-wide ethics award scheme.

- Coverage of examples of good ethical or anti-corruption practice in the company newsletter.

- Thank you letters from the CEO or senior managers for people who display ethical behaviour.

- Dinner with the CEO as a prize for people who demonstrate ethical behaviour.

Source: Transparency International

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. The Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY The Ethics Alliance 31 MAY 2019

“How am I doing?” is a question that has helped graphic design platform, Canva, to become one of Australia’s most talked-about startups.

In May, the six-year-old company announced it had raised $70 million from US venture capital firm General Catalyst (valuing Canva at $3.6 billion) and acquired two stock photography firms.

Its workplace culture has also received acclaim – with top employer awards from Great Place To Work and LinkedIn last year – and its workforce has at least doubled every year.

In answer to the question above, it seems like Canva is doing very well, thank you.

The practise of asking for feedback is a core part of Canva’s culture and performance strategies. We need to know how we are going so we can improve, however most of us hate the assessment.

New York University research at a major consultancy looked at our aversion to criticism and discovered that people are equally anxious, whether they are giving the feedback or receiving it.

One of the co-authors of the study, psychologist and NeuroLeadership Institute senior scientist, Tessa West, says the best way to develop a “feedback culture” is to train people to ask for it – rather than wait for it to be delivered.

By requesting the assessment of their performance, individuals feel a sense of control and certainty and can steer the discussion where they want. The people giving the feedback will also feel more relaxed, because they no longer have to guess what is wanted from them.

The head of people at Canva, Zach Kitschke, says new hires are introduced to the feedback culture through an “onboarding boot camp”, featuring sessions from the three founders of the company – Melanie Perkins, Cliff Obrecht and Cameron Adams.

“Having a feedback conversation can be challenging and quite tricky, but we have a workshop that everyone goes through to learn how to do feedback and act in a constructive, supportive way,” Kitschke says.

“We have the philosophy that if everyone is constantly asking what they did well, or how they went in the meeting or what could they do better or how could they grow, then people are more open and more ready to hear feedback and people are more likely to give it as well.”

Kitschke has been with Canva for six years, from when it was a small startup with seven people to its present workforce of 600 in three offices in Sydney, Manila and Beijing.

Executive coach, Sarah Nanclares, joined the company as an internal coach last year and writes in a Canva blog: “… asking for feedback is a bit like exercising a muscle: the more you use it, the easier it becomes, and before you know it seeking regular feedback is no longer a scary task. In fact, it becomes welcomed.”

Points of difference

1.Skin in the game: Every employee is given equity options and becomes an owner of the business. Employees get a bonus of $5,000 if they successfully introduce a new hire to the business.

2. The Fix-It form: This form can be used to notify the founders and other senior executives of any problems.

3. Right fit: Recruits are screened for the values: Be a force for good, be a good human, set crazy big goals and make them happen, empower others, pursue excellence, and make complex things simple.

4. Someone to watch over me: Every new person gets paired with a mentor from the same area or discipline. Anyone can receive training to be a mentor.

5. Businesses within the business: Within Canva are 15 groups that function as their own startups, running independently, with the ability to move quickly.

6. Breaking bread: The teams stop for lunch every day and sit together at long tables so that no-one has to eat alone. A chef prepares shared serving plates and anything not eaten at lunch is refrigerated for people to take home for dinner. Ingredients come from a Canva-owned farm and the bar is open all day.

7. Open door: Employees are welcome to bring their dogs and children to work.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. The Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Moral injury is a new test for employers

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Do Australian corporations have the courage to rebuild public trust?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment