What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 16 APR 2019

Free Will describes our capacity to make choices that are genuinely our own. With free will comes moral responsibility – our ownership of our good and bad deeds.

That ownership indicates that if we make a choice that is good, we deserve the resulting rewards. If in turn we make a choice that is bad, we probably deserve those consequences as well. In the case of a really bad choice, such as committing murder, we may have to accept severe punishment.

The link between free will and responsibility has both theological and philosophical roots.

Within theology, for example, the claim that humans are ‘made in the image of God’ (a central tenet of major religions like Judaism, Christianity and Islam) is not that they are the physical image of their creator.

Rather, the claim is made that humans are made in the ‘moral image’ of God – which is to say that they are endowed with the ‘divine’ capacity to exercise free will.

Of course, the experience of free will is not limited to those who hold a religious belief. Philosophers also argue that it would be unjust to blame someone for a choice over which they have no control.

Determinism is the belief that all choices are determined by an unbroken chain of cause and effect. Those who believe in ‘determinism’ oppose free will, arguing that that the belief that we are the authors of our own actions is a delusion.

Whereas scientific evidence has found there is brain activity prior to the sensation of having made a choice, we’re unable to resolve the question of which account is correct.

Should that gap close – and free will be proven to be an illusion, then the basis for ascribing guilt to those who act unethically (including criminals) will also be destroyed.

How could we justify punishing a person who claims that they had no choice but to do evil?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We can help older Australians by asking them for help

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anzac Day: militarism and masculinity don’t mix well in modern Australia

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What is it like to be a bat?

“What is it like to be a bat?” is the intriguing question philosopher Thomas Nagel asks in his 1974 article, first published in The Philosophical Review.

Nagel’s argument goes something like this:

“We can imagine what it might be like to be nocturnal, to have webbing on our arms, to be able to fly, to have poor vision and perceive the world through high frequency sound signals, and to spend our time hanging upside down.”

“But even if we can imagine all of these things, it only tells us what it is like for me to be a bat, or for me to behave as a bat behaves. It does not tell us what it is like for a bat to be a bat.”

More than meets the eye

Is Nagel correct?

Nagel is pointing out that there is a subjective character of conscious experience that is not captured by physical descriptions of the brain or observable behaviours. He is taking issue with the reductive materialist or physicalist account that denies the so called gap between ‘mind’ and brain in the mind-body problem.

The mind-body problem comes about because we often subjectively feel as though our mind, with which we often identify the most, is somehow so much more than just our physical brain. Our mind sometimes also feels separable (even if not detached) from our body!

For example, we may forget that we are sitting on a bus, riding to work, and instead be transported back to an earlier time through the use of our memory. There is also the sense that my experiences are truly unique to me, and no one else can understand them in quite the same way.

The materialist denies the gap between mind and brain by arguing that the mind and consciousness is explainable entirely by physical processes. This position they defend is known as monism, and stands in contrast to dualism.

Note that René Descartes was a Dualist, due to his account of mind and body as two different substances. He equated the mind with the soul – an immaterial substance.

Mind over matter?

While Nagel is not committed to dualism, he claims that physicalism, if it is to be convincing, needs to account for both objective and subjective experience. Both are required to understand the mind-body problem. He contends, “Without consciousness the mind-body problem would be much less interesting. With consciousness it seems hopeless’”!

Nagel doesn’t think we can easily explain consciousness by simply describing a person or animal’s experience or set of behaviours.

This raises the troubling question: if I cannot embody a particular perspective, for instance, I cannot actually be anyone other than myself, then how can I truly understand it?

How can I ever know what it is like to be a bat, a dog, a cat, a horse, or even another person? Can I only ever truly understand what it is like to be me?

Nagel highlights the fact that there’s something mysterious about consciousness that cannot simply be explained away.

Nagel’s argument has been met with criticism. Daniel Dennett is one such critic, even while acknowledging this paper as “The most widely cited and influential thought experiment about consciousness”.

Dennett denies Nagel’s claim that the bat’s consciousness is inaccessible. He says the most important features of a bat’s consciousness would be accessible in some way to third person (that is, ‘objective’ or empirical) observation. In this way, information about what it is like to be a bat could be gleaned using scientific experiments.

Does it feel the same to you?

Yet this thought experiment still captures the imagination and plays on our fears of existing in a solipsistic universe. With our desire to be understood, we want to know that others understand what it is like for us, and, similarly, we them.

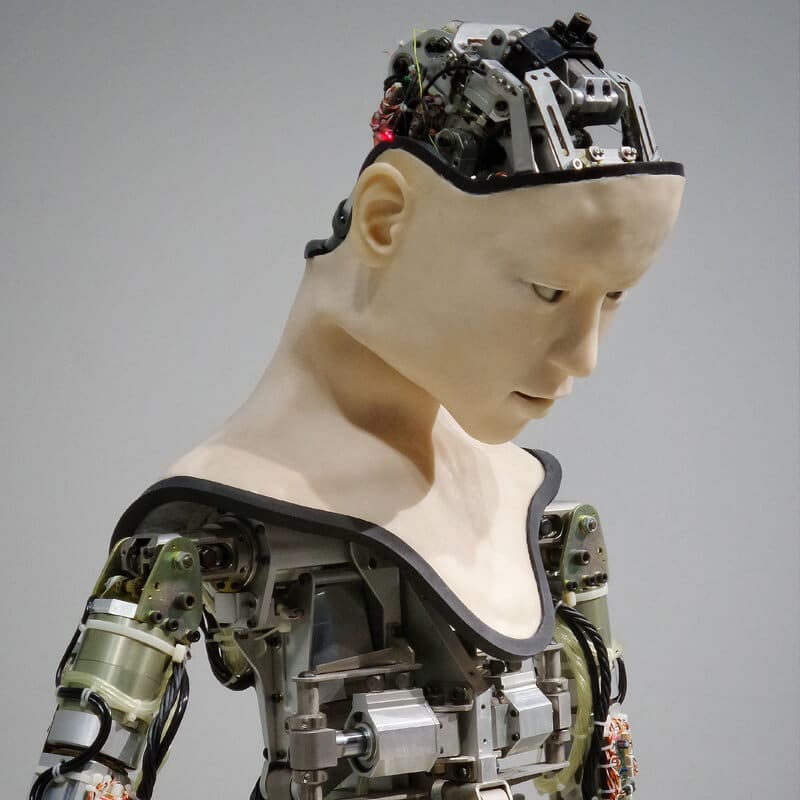

Plus, we can go further. With the development of artificial intelligence (AI), how can we know when a computer becomes conscious? And if it is conscious, could we understand what that is like?

Isn’t this important if we develop conscious robots who could be harmed by what we require of them (for example, to fight in wars)?

More simply, if you have ever wondered whether the sky you see as blue is the same experience had by your friend (assuming they are not colour blind), or whether the sweet strawberry tastes the same to your partner, then you are playing with this idea of subjective conscious experience.

Can we ever truly know what it is like for someone or something else?

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

Why ethics matters for autonomous cars

Why ethics matters for autonomous cars

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 14 APR 2019

Whether a car is driven by a human or a machine, the choices to be made may have fatal consequences for people using the vehicle or others who are within its reach.

A self-driving car must play dual roles – that of the driver and of the vehicle. As such, there is a ‘de-coupling’ of the factors of responsibility that would normally link a human actor to the actions of a machine under his or her control. That is decision to act and the action itself are both carried out by the vehicle.

Autonomous systems are designed to make choices without regard to the personal preferences of human beings, those who would normally exercise control over decision-making.

Given this, people are naturally invested in understanding how their best interests will be assessed by such a machine (or at least the algorithms that shape – if not determine – its behaviour).

In-built ethics from the ground up

There is a growing demand that the designers, manufacturers and marketers of autonomous vehicles embed ethics into the core design – and then ensure that they are not weakened or neutralised by subsequent owners.

We can accept that humans make stupid decisions all the time, but, we hold autonomous systems to a higher standard.

This is easier said than done – especially when one understands that autonomous vehicles are unlikely ever to be entirely self-sufficient. For example, autonomous vehicles will often be integrated into a network (e.g. geospatial positioning systems) that complements their integrated, onboard systems.

A complicated problem

This will exacerbate the difficulty of assigning responsibility in an already complex network of interdependencies.

If there is a failure, will the fault lie with the designer of the hardware, or the software, or the system architecture…or some combination of these and others? What standard of care will count as being sufficient when the actions of each part affects the others and the whole?

This suggests that each design element needs to be informed by the same ethical principles – so as to ensure as much ethical integrity as possible. There is also a need to ensure that human beings are not reduced to the status of being mere ‘network’ elements.

What we mean by this is to ensure the complexity of human interests are not simply weighed in the balance by an expert system that can never really feel the moral weight of the decisions it must make.

For more insights on ethical technology, make sure you download our ‘Ethical by Design‘ guide where we take a detailed look at the principles companies need to consider when designing ethical technology.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

The undeserved doubt of the anti-vaxxer

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How can Financial Advisers rebuild trust?

How can Financial Advisers rebuild trust?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 12 APR 2019

It would be no exaggeration to say the Australian financial advice industry is going through a difficult time.

Following years of scandals, and shocking evidence brought to light by the Hayne royal commission, urgent steps are now being taken to “professionalise” the banking and finance sector.

Amongst the headlines: embattled financial services giant AMP is setting aside an eye watering $290 million to compensate customers who received poor financial advice, and a further $35 million annually to improve compliance structures.

All of the major banks have announced their plans to “amputate” financial advice and wealth management from their portfolio of vertically integrated activities.

Many advisers have already lost their jobs. And many more have already announced their intention to leave the industry rather than face greater scrutiny and a new compliance burden.

For those operators planning to stay in business, there’s a new sheriff in town. The Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority (FASEA) was established by the Federal Government in 2017 to set the education, training and ethical standards of licensed financial advisers in Australia.

FASEA requirements for mandatory education and Continuous Professional Development (CPD) are unlike anything the industry has ever seen.

The push to professionalise the sector is moving with speed. Starting this year, advisers will be required to undertake formal education, in the form of either a full degree or bridging course, plus nine hours of continuing professional development (CDP) annually. Advisers will be required to pass an exam to earn their license and continue to operate.

What’s the problem?

While the standards mentioned above might sound perfectly reasonable to someone already working within a well established profession such as accountancy or the law, this is unfamiliar territory for many financial advisers.

Many advisers who have been working for years or even decades will be daunted by the demand for serious study and a formal academic qualification. Some advisers have already expressed concern at the financial burden of course fees and lost income. Many others will be daunted by the sheer number of hours required each year to meet FASEA’s standards.

It’s little wonder the industry is going through a crisis of confidence. And while the emphasis has rightly been placed on the rights of the customer, and the many people who have received poor advice, it’s also worth pausing to think about the impact this has on individual advisers – some of whom have been operating honestly and ethically for many years. For such people, and there are many, the avalanche of bad press and community outcry has been difficult to bear.

We know many people become financial advisers because they are passionate about the financial wellbeing of their family, friends and community. They aspire to help people secure economic stability and security whilst avoiding the abundant pitfalls and bad products.

Of Gallup’s Five Essential Elements of Well-being, financial security is at the centre. Practiced ethically and professionally, the work of a financial adviser supports and protects other critical areas of a person’s life.

This leads to some interesting questions about the overarching purpose of a financial adviser.

Why does this role exist? What purpose does it serve individuals, communities and society at large? What is the overarching public good that can be achieved from a profession that supports, protects and grows a person’s financial wealth?

Or to look at it another way, what would the world look like without financial advice? If all of the competent advisers were to leave the industry, where does that leave the community?

Advisers who are on the fence about their future should take time to work out what the role of financial advice means to them. Whilst the reputation of the industry may be at its lowest point, it’s a great time to get back to basics and think about the purpose and impact of this type of work.

What is the solution?

The Ethics Centre has had quite a bit of involvement in this story as it’s unfolded. When the scandal first began to erupt three years ago, we worked with some of the largest advice firms to develop in-house training programs for financial advisers.

We’ve helped inform FASEA’s thinking on ethical standards for the industry. We’re currently working on building a course on ethics and professionalism to be delivered by universities.

We also offer free counselling to individuals via our Ethi-call service – and that includes financial advisers struggling at a career crossroads.

For those advisers currently at this point, we’d advise some clear headed thinking about career purpose and priorities. If you think you’d benefit from talking through your dilemma with an impartial counsellor, you are welcome to call Ethi-call.

The service is a free, appointment-based telephone counselling service offered by The Ethics Centre to help people navigate some of life’s toughest decisions.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The Ethics of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF)

The Ethics of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF)

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 8 APR 2019

To understand the ethics of IVF (In vitro fertilisation) we must first consider the ethical status of an embryo.

This is because there is an important distinction to be made between when a ‘human life’ begins and when a ‘person’ begins.

The former (‘human life’) is a biological question – and our best understanding is that human life begins when the human egg is fertilised by sperm or otherwise stimulated to cause cell division to begin.

The latter is an ethical question – as the concept of ‘person’ relates to a being capable of bearing the full range of moral rights and responsibilities.

There are a range of other ethical issues IVF gives rise to:

- the quality of consent obtained from the parties

- the motivation of the parents

- the uses and implications of pre-implantation genetic diagnosis

- the permissibility of sex-selection (or the choice of embryos for other traits)

- the storage and fate of surplus embryos.

For most of human history, it was held that a human only became a person after birth. Then, as the science of embryology advanced, it was argued that personhood arose at the moment of conception – a view that made sense given the knowledge of the time.

However, more recent advances in embryology have shown that there is a period (of up to about 14 days after conception) during which it is impossible to ascribe identity to an embryo as the cells lack differentiation.

Given this, even the most conservative ethical position (such as those grounded in religious conviction) should not disallow the creation of an embryo (and even its possible destruction if surplus to the parents’ needs) within the first 14 day window.

Let’s further explore the grounds of some more common objections. Some people object to the artificial creation of a life that would not be possible if left entirely to nature. Or they might object on the grounds that ‘natural selection’ should be left to do its work. Others object to conception being placed in the hands of mortals (rather than left to God or some other supernatural being).

When covering these objection it’s important to draw attention existing moral values and principles. For example, human beings regularly intervene with natural causes – especially in the realm of medicine – by performing surgery, administering pharmaceuticals and applying other medical technologies.

A critic of IVF would therefore need to demonstrate why all other cases of intervention should be allowed – but not this.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

License to misbehave: The ethics of virtual gaming

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Australia, we urgently need to talk about data ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is technology destroying your workplace culture?

Is technology destroying your workplace culture?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 6 APR 2019

If you were to put together a list of all the buzzwords and hot topics in business today, you’d be hard pressed to leave off culture, innovation or disruption.

They might even be the top three. In an environment of constant technological change, we’re continuously promised a new edge. We can have sleeker service, faster communication or better teamwork.

This all makes sense. Technology is the future of work. Whether it’s remote work, agile work flows or AI enhanced research, we’re going to be able to do more with less, and do it better.

For organisations who are doing good work, that’s great. And if those organisations are working for the good of society (as they should), that’s great for us all.

Without looking a gift horse in the mouth though, we should be careful technology enhances our work rather than distracting us from it.

Most of us can probably think of a time when our office suddenly had to work with a totally new, totally pointless bit of software. Out of nowhere, you’ve got a new chatbot, all your info has been moved to ‘the cloud’ or customer emails are now automated.

This is usually the result of what the comedian Eddie Izzard calls “techno-joy”. It’s the unthinking optimism that technology is a cure for all woes.

Unfortunately, it’s not. Techno-joyful managers are more headache than helper. But more than that, they can also put your culture – or worse, your ethics – in a tricky spot.

Here’s the thing about technology. It’s more than hardware or code. Technology carries a set of values with it. This happens in a few ways.

Techno-logic

All technology works through a worldview we call ‘techno-logic’. Basically, technology aims to help us control things by making the world more efficient and effective. As we explained in our recent publication, Ethical by Design:

Techno-logic sees the world as though it is something we can shape, control, measure, store and ultimately use. According to this view, techno-logic is the ‘logic of control’. No matter the question, techno-logic has one overriding concern: how can we measure, alter, control or use this to serve our goals?

Whenever you’re engaging with technology, you’re being invited and encouraged to see the world in a really narrow way. That can be useful – problem solving happens by ignoring what doesn’t matter and focussing on what’s important. But it can also mean we ignore stuff that matters more than just getting the job done as fast or effectively as we can.

A great example of this comes from Up in the Air, a film in which Ryan Bingham (George Clooney) works for a company who specialise in sacking people. When there are mass layoffs to be made, Bingham is there. Until technology comes to call. Research suggests video conferencing would be cheaper and more effective. Why fly people around America when you can sack someone from the comfort of your own office?

As Bingham points out, you do it because sometimes making something efficient destroys it. Imagine going on an efficient date or keeping every conversation as efficient as possible. We’d lose something essential, something rich and human.

With so much technology available to help with recruitment, performance management and customer relations, we need to be mindful that technology is fit for purpose. It’s very easy for us to be sucked into the logic of technology until suddenly, it’s not serving us, we’re serving it. Just look at journalism.

Drinking the affordance Kool-Aid

Journalism has always evolved alongside media. From newspaper to radio, podcasting and online, it’s a (sometimes) great example of an industry adapting to technological change. But at times, it over adapts, and the technological cart starts to pull the journalistic horse.

Today, online articles are ‘optimised’ to drive engagement and audience. This means stories are designed to hit a sweet spot in word count to ensure people don’t tune out, they’re given titles that are likely to generate clicks and traffic, and the kinds of things people are likely to read tend to get more attention.

A lot of that is common sense, but when it turns out that what drives engagement is emotion and conflict, this can put journalists in a bind. Are they impartial reporters of truth, lacking an audience, or do they massage journalistic principles a little so they can get the most readers they can?

I’ll leave it to you to decide which way journalism as an industry has gone. What’s worth noting is that many working in media weren’t aware of some of these changes whilst they were happening. That’s partly because they’re so close to the day-to-day work, but it can also be explained by something called ‘affordance theory’.

Affordance theory suggests that technological design contains little prompts, suggesting to users how they should interact with it. They invite users to behave in certain ways and not others. For example, Facebook makes it easier for you to respond to an article with feelings than thinking. How? All you need to do to ‘like’ a post is click a button but typing out a thought requires work.

Worse, Facebook doesn’t require you to read an article at all before you respond. It encourages quick, emotional, instinctive reactions and discourages slow thinking (through features like automatic updates to feeds and infinite scroll).

These affordances are the water we swim in when we’re using technology. As users, we need to be aware of them, but we also need to be mindful of how they can affect purpose.

Technology isn’t just a tool, it’s loaded with values, invitations and ethical judgements. If organisations don’t know what kind of ethical judgements are in the tools they’re using, they shouldn’t be surprised when they end up building something they don’t like.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is it fair to expect Australian banks to reimburse us if we’ve been scammed?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

An ethical dilemma for accountants

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Productivity isn’t working, so why not try being more ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Beyond the shadows: ethics and resilience in the post-pandemic environment

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY David Burfoot 22 MAR 2019

Play fair or play to win. The interests of an individual player versus the team. Bad leaders who get good results.

These are just some of the common ethical tensions occurring throughout elite Australian sport. And they lead to corruption.

The Ethics Centre undertook two high profile reviews of sporting organisations over the past 18 months, the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) and Cricket Australia (CA).

Australian Olympic Committee

Our AOC review explored the comparison between sportsmanship and gamesmanship. Sportsmanship is the fair, honest and decent treatment of others in competition. Gamesmanship, on the other hand, is built on the principle that winning is everything. Athletes and coaches are encouraged to plot, ploy and bend the rules wherever possible in order to gain a competitive advantage over opponents.

Bridging the two approaches was problematic. It culminated in disenchantment, frustration and an organisational culture within AOC that neither represented the best of sport or organisational administration.

The Ethics Centre delivered a warts-and-all report with 17 recommendations, all of which were accepted.

Recent discussions with AOC reveal a major shift in the culture of the organisation over the last 12 months, under the leadership of CEO Matt Carroll and the head of people and culture, Amie Wallis. AOC staff need to be congratulated for their achievements.

Ball tampering and Cricket Australia

The other engagement was with Cricket Australia – a culture and governance review in response to the ball tampering incident in South Africa in March 2018, something that was clearly against the rules.

Initial attempts by players to conceal what they were doing was testament to this, but it wasn’t as clean cut as that. The incident seemed to represent an attack on something sacred to Australians. Many fans reacted as if they were personally afflicted.

Our subsequent interviews and surveys with CA staff, players, officials, sponsors and members of the public often explored the difference between sportsmanship and gamesmanship.

Comparisons were drawn between ball tampering, sledging and the underarm bowling incident in 1981 during a One Day International cricket match between Australia and New Zealand.

Sporting HR executives

We recently had the good fortunate of being invited to a discussion about such issues with a group of HR executives, representing some of the major professional sporting organisations in Australia, from Horse Racing to Rugby, organised by Mercer Australia.

We put to them the observation that when there is fraud in government, the actions are often labelled corruption, as they signify a greater social betrayal than a breach of the law. Fraud in the private sector doesn’t attract the same moral outrage and avoids the label of corruption. But there is one exception. Sport also uses the word corruption to describe fraudulent behaviour. We asked why.

The group started with the suggestion people take sport personally, as we all feel part of it and like we own it. We play it to pursue the best in us, we barrack for our team, our kids play it, and we use it as a tool to teach our children about values and what is important in life. We feel obliged to have an opinion about it, perhaps as Australians.

This is probably why people feel fraud in sport is a moral issue that goes beyond compliance with the law, a social ‘evil’ that the word ‘corruption’ better conveys. There was also the feeling that corruption is used because it reveals the interconnected network that comes with fraud in sport.

When asked about the dilemmas in sport more broadly, many spoke about the challenge players experience balancing their need to win and earn income, with their long-term wellbeing. Players often hide injuries to avoid being dropped from teams. These injuries are often physical, and sometimes mental. The period where an athlete is most successful financially is narrow. This creates pressure to sacrifice long-term health.

As HR professionals they also spoke of their dilemmas, when they need to balance advocacy for the individual player with the best interests of the company or business side of the sport. They spoke of this also in relation to the management of the team, when the coach feels the need to let someone play because their family is present, even though it may not be in the best interest of a win.

They spoke about how officials can overlook bad leadership when the characters themselves raise the winning morale of teams. Some spoke about the challenges of being considerate of a person’s background, but also being clear that it did not excuse bad behaviour such as sexual harassment.

We see related dilemmas in other sectors currently under the public spotlight. It is accepted that the unique relationship between sport and ethics has been neglected by philosophers.

There may be much to be learned by our experience of sport, and how its values are brought to the wider theatre of life. These discussions help us reach a better understanding about these relationships.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The role of ethics in commercial and professional relationships

LISTEN

Society + Culture

Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI)

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Eudaimonia

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

BY David Burfoot

David has worked in the not-for-profit, public and private sectors domestically and internationally for organisations as diverse as the United Nations Development Program, Deloitte, the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption and Sydney University. He has been an anti-corruption specialist with a number of government agencies and held senior positions responsible for corporate planning, change and internal communications.

Can robots solve our aged care crisis?

Can robots solve our aged care crisis?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingScience + Technology

BY Fiona Smith 21 MAR 2019

Would you trust a robot to look after the people who brought you into this world?

While most of us would want our parents and grandparents to have the attention of a kindly human when they need assistance, we may have to make do with technology.

The reason is: there are just not enough flesh-and-blood carers around. We have more seniors entering aged care than ever before, living longer and with complex needs, and we cannot adequately staff our aged care facilities.

The percentage of the Australian population aged over 85 is expected to double by 2066 and the aged care workforce would need to increase between two and three times before 2050 to provide care.

The looming dilemma

With aged care workers among the worst-paid in our society, there is no hope of filling that kind of demand. The Royal Commission into aged care quality and safety is now underway and we are facing a year of revelations about the impacts of understaffing, underfunding and inadequate training.

Some of the complaints already aired in the commission include unacceptably high rates of malnutrition among residents, lack of individualised care and cost-cutting that results in rationing necessities such as incontinence pads.

While the development of “assistance robots” promises to help improve services and the quality of life for those in aged care facilities, there are concerns that technology should not be used as a substitute for human contact.

Connection and interactivity

Human interaction is a critical source of intangible value for the development of human beings, according to Dr Costantino Grasso, Assistant Professor in Law at Coventry University and Global Module Leader for Corporate Governance and Ethics at the University of London.

“Such form of interaction is enjoyed by patients on every occasion in which a nurse interacts with them. The very presence of a human entails the patient value recognising him or her as a unique individual rather than an impersonal entity.

“This cannot be replaced by a robot because of its ‘mechanical’, ‘pre-programmed’ and thus ‘neutral’ way to interact with patients,” Grasso writes in The Corporate Social Responsibility And Business Ethics Blog.

The loss of privacy and autonomy?

An overview of research into this area by Canada’s McMaster University shows older adults worry the use of socially assistive robots may lead to a dehumanised society and a decrease in human contact.

“Also, despite their preference for a robot capable of interacting as a real person, they perceived the relationship with a humanoid robot as counterfeit, a deception,” according to the university.

Older adults also perceived the surveillance function of socially assistive robots as a threat to their autonomy and privacy.

A potential solution to the crisis

The ElliQ, a “home robot” now on the market, is a device that looks like a lamp (with a head that nods and moves) that is voice activated and can be the interface between the owner and their computer or mobile phone.

It can be used to remind people to take their medication or go for a walk, it can read out emails and texts, make phone calls and video calls and its video surveillance camera can trigger calls for assistance if the resident falls or has a medical problem.

The manufacturer, Intuition Robotics, says issues of privacy are sorted out “well in advance”, so that the resident decides whether family or anyone else should be notified about medical matters, such as erratic behaviour.

Despite having a “personality” of a helpful friend (who willingly shoulders the blame for any misunderstandings, such as unclear instructions from the user), it is not humanoid in appearance.

While ElliQ does not pretend to be anything but “technology”, other assistance robots are humanoid in appearance or may take the form of a cuddly animal. There are particular concerns about the use of assistance robots for people who are cognitively impaired, affected by dementia, for instance.

While it is a guiding principle in the artificial intelligence community that the robots should not be deceptive, some have argued that it should not matter if someone with dementia believes their cuddly assistance robot is alive, if it brings them comfort.

Ten tech developments in Aged Care

1. Robotic transport trolleys:

The Lamson RoboCart delivers meals, medication, laundry, waste and supplies.

2. Humanoid companions:

AvatarMind’s iPal is a constant companion that supplements personal care services and provides security with alerts for many medical emergencies such as falling down. Zora, a robot the size of a big doll, is overseen by a nurse with a laptop. Researchers in Australia found that it improved the mood of some patients, and got them more involved in activities, but required significant technical support.

3. Emotional support:

Paro is an interactive robotic baby seal that responds to touch, noise, light and temperature by moving its head and legs or making sounds. The robot has helped to improve the mood of its users, as well as offers some relief from the strains of anxiety and depression. It is used in Australia by RSL LifeCare.

4. Memory recovery:

Dthera Sciences has built a therapy that uses music and images to help patients recover memories. It analyses facial expressions to monitor the emotional impact on patients.

5. Korongee village:

This is a $25 million Tasmania facility for people with dementia, comprising 15 homes set within a small town context, with streets, a supermarket, cinema, café, beauty salon and gardens. Inspired by the dementia village of De Hogeweyk in the Netherlands, where residents have been found to live longer, eat better, and take fewer medications.

6. Pub for people with dementia:

Derwen Ward, part of Cefn Coed Hospital in Wales, opened the Derwen Arms last year to provide residents with a safe, but familiar, environment. The pub serves (non-alcoholic) beer, and has a pool table, and a dart board.

7. Pain detection:

PainChek is a facial recognition software that can detect pain in the elderly and people living with dementia. The tool has provided a significant improvement in data handling and simplification of reporting.

8. Providing sight:

IrisVision involves a Samsung smartphone and a virtual reality (VR) headset to help people with vision impairment see more clearly.

9. Holographic doctors:

Community health provider Silver Chain has been working on technology that uses “holographic doctors” to visit patients in their homes, creating a virtual clinic where healthcare professionals can have access to data and doctors.

10. Robotic suit:

A battery-powered soft exoskeleton helps people walk to restore mobility and independence.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Article

Ethics Explainer: Respect

ArticleBeing Human

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Kym Middleton 21 MAR 2019

Immigration is the hot election issue connecting everything from mismanaged water and mass fish deaths in the Murray Darling to congested cities and unaffordable housing.

The 2019 IQ2 season kicks off with ‘Curb Immigration’ on 26 March. It’s something Prime Minister Scott Morrison promised to do today if re-elected and opposition leader Bill Shorten has committed to considering.

Here’s a collection of ideas, research, articles and arguments covering the debate.

New migrants to go regional for permanent residency, under PM’s plan

Scott Morrison, SBS News / 20 March 2019

Prime Minister Scott Morrison revealed his immigration plan today. He confirmed reports he will lower the cap on Australia’s immigration intake from 190,000 to 160,000 for the next four years. He announced 23,000 visa places that require people to live and work in regional Australia for three years before they can apply for permanent residency. “It is about incentives to get people taking up the opportunities outside our big cities” and “it’s about busting congestion in our cities”, Morrison said.

————

Australian attitudes to immigration: a love / hate relationship

The Ethics Centre, The New Daily / 24 January 2019

You’ll hear Australians talk about our country as either a multicultural utopia or intolerant mess. This article charts many recent surveys on our attitudes to immigration. The results show almost equal majorities of us love and hate it for different reasons, suggesting individual people both support and reject immigration at the same time. We’re complex creatures.

————

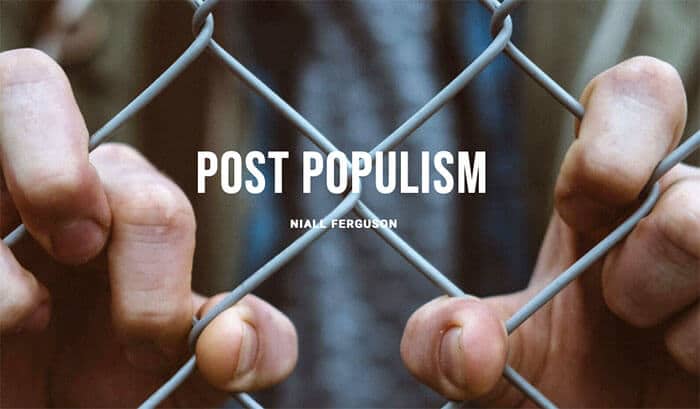

Post Populism

Niall Ferguson, Festival of Dangerous Ideas / 4 November 2018

At the Festival of Dangerous Ideas on Cockatoo Island, Niall Ferguson presented his take on the five ingredients that have bred the nationalistic populism sweeping the western world today. Point one: increased immigration. Listen to the podcast or watch the video highlights. Elsewhere, Ferguson points to Brexit and the European migrant crisis and predicts, “the issue of migration will be seen by future historians as the fatal solvent of the EU”.

————

Human Flow movie

Ai Weiwei / 2017

Part documentary and part advocacy, Human Flow is a film by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei that “gives a powerful visual expression” to the 65 million people displaced from their homes by climate change, war or famine. It is not the story of ‘orderly migration’ based on skilled visas or spatial planning policies, but rather, one of mass flows across countries and continents.

————

Government needs to wake up to impact of population boom

PM, ABC RN / 23 February 2018

IQ2 guest and human geographer Dr Jonathan Sobels is interviewed by Linda Mottram on the impact of Australia’s population growth on the continent’s natural environment. He’s not the only person concerned about this. A 2019 study by ANU found 75 percent of Australians agree the environment is already under too much pressure with the current population size.

————

Counter-terrorism expert Anne Aly: ‘I dream of a future in which I’m no longer needed’

Greg Callaghan, The Sydney Morning Herald / 18 November 2016

Dr Anne Aly is a counter terrorism expert come politician with “instant relatability”, according to this feature piece on her. Get to know more about her interesting life and career before catching her at IQ2 where she’ll argue against the motion ‘Curb Immigration’. Aly is the Labor Member for the West Australian electorate of Cowan and first female Muslim parliamentarian in Australia.

————

Event info

Get your IQ2 ‘Curb Immigration’ tickets here

Satya Marar & Jinathan Sobels vs Anne Aly & Nicole Gurran

27 March 2019 | Sydney Town Hall

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Article

Ethics Explainer: Respect

ArticleBeing Human

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Cris Parker 20 MAR 2019

“I am a trusted advisor.” That is how the man described himself when he approached me at the end of a conference.

We had gathered to discuss the implications of the Royal Commission into banking and finance and how that industry could emerge with a stronger ethical backbone.

“What is the best way to get that ethical message across?” asked the man in front of me.

Well, part of the problem was right there on his business card. You can’t self-nominate trust. You have to earn it. You can’t appropriate it yourself with a wishful job title or marketing slogan. You have to do the work and leave it to others to decide if you can be trusted. Or not.

A greater focus on trust itself

Trust has been seen as a top business priority and growing in importance over the past few years, especially after the Global Financial Crisis of 2007 where people’s life savings were misused by the people in institutions that had promised to take care of them. The rise of the populist Occupy movement four years later was a warning shot to those in power that resonated globally.

However, much of the conversation since then about the poor reputation of business has failed to come to terms with the enormity of the task ahead. Trust is often spoken about as the currency that allows companies the privilege of taking care of another person’s wealth.

Not so much is said about the process of getting there – or even whether trust is the outcome companies should be focused on.

After all, having people’s trust does not necessarily mean that you are trustworthy.

Dealing in deception

Why should “trust” not be an end in itself? Well, US stockbroker and financial advisor Bernie Madoff was widely trusted by his wealthy investors before they realised they had been collectively fleeced of $US64.8 billion in the largest Ponzi scheme in history.

Closer to home in Australia, conman Hamish McLaren took $7.66 million from 15 separate victims – many of whom were referred to him by friends and family. McLaren was so trusted that one woman handed over her divorce settlement without even asking his last name.

McLaren is the subject of The Australian newspaper’s most recent podcast series “Who the Hell is Hamish?”.

Trust, by itself, is not always what it is cracked up to be.

Restoring confidence and trust

So the question is not “How can we get people to trust us again?”, but should be instead “What can we do to become trustworthy?”. Organisations need to focus on the process of getting there, rather than the result. It will take time, there needs to be consistency in behaviour and there’s an element of forgiveness that needs to be addressed.

Forgiveness means that the forgiver needs to believe that you won’t behave that way again. Declaring your best intentions doesn’t work, it needs to be seen.

Being trustworthy means that people in your organisation behave ethically because it’s the right thing to do, not because it will make people trust them again. A reputation for trustworthiness is, again, not something you can just anoint yourself with.

A solid reputation is bestowed upon you and comes through an accumulation of other people’s personal experiences of you and your work.

Legendary investor Warren Buffett, the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, has provided the business world with a wealth of pithy and insightful quotes through his annual letters to shareholders.

One is said to be: “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. If you think about that, you’ll do things differently”.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. An initiative of The Ethics Centre, The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Article

Ethics Explainer: Respect

ArticleBeing Human