The power of community to bring change

The power of community to bring change

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 19 NOV 2019

On Thursday night, a group of impassioned supporters and philanthropists gathered for a raw look at the work required to get an Ethics Centre program off the ground.

It was our very first Pitch & Pledge event – a unique crowdfunding concept by The Funding Network where charities pitch their funding needs live to a room of curious minds.

The format required three of our program leaders – Alex Hirst, Sally Murphy and Matt Beard – to take to the stage to make a six minute appeal for support for their work. Alex shared why she believes the Festival of Dangerous Ideas is critical to a tolerant society, Sally argued why more people need access to our free counselling helpline, Ethi-call, and Matt canvassed the idea of a budding young philosopher to further our work.

Following their pitches and a barrage of interesting questions from the floor, our leaders were asked to leave the room for a nail-biting window of time while guests pledged their support for their favourite program.

In an electric, emotionally charged and heartwarming hour we raised over $80,000 across the three causes, as well as further pro-bono support. We are incredibly grateful for the generosity of those who attended, and invite you to take a look at the pitches below and consider if there’s one worthy of your backing as well.

1. Support a truly independent Festival of Dangerous Ideas

Alex compelled us to realise that 10 years on from the first Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) in 2010, it’s no longer just a world of dangerous ideas we are considering – it’s the dangerous realities we need to be afraid of. Our modern world of opinion echo chambers and media algorithms that serve to confirm our biases, has lead to an inability across society to have informed and hard conversations about opposing views.

FODI is about challenging our ways of thinking, not confirming them. Sharing personal anecdotes and stories from FODI followers, Alex captured, to a rapt crowd, the sheer necessity of expansive thinking and contested ideas.

“Unchallenged ideas are after all some of the most dangerous, and they are reaching us in more ways than ever before. Reaching right into the heart of the home, and into our everyday lives.”

“If we are unable to have hard conversations, if we are untrained at listening to the ideas that we just don’t want to hear, then our ability as a society to face these dangerous realities together doesn’t exist”.

Ticket sales from the annual festival cover just 50% of festival running costs. Alex, and FODI, need support to bring critical thinking back to challenge dangerous realities in 2020.

Donate here: https://www.thefundingnetwork.com.au/ethics-centre

2. Help Ethi-call guide people through life’s tough decisions

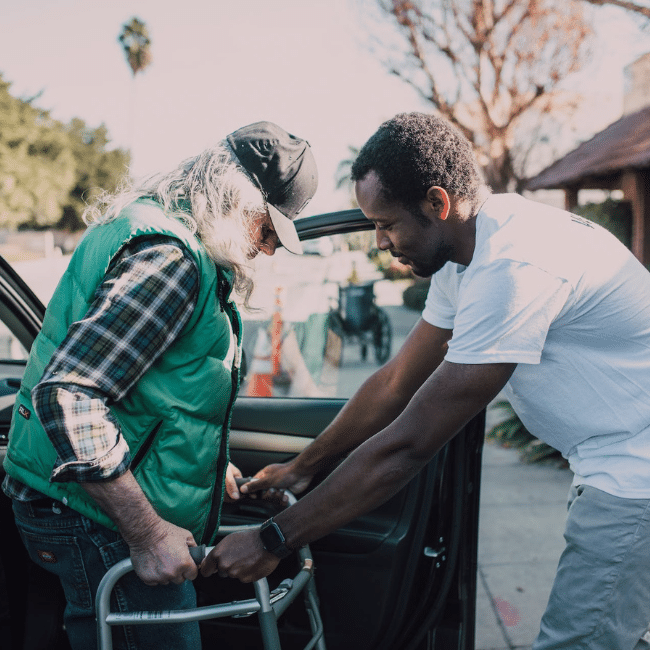

Sally knows challenging situations. As a volunteer Ethi-call counsellor and manager of the service, she’s heard first-hand the difficult and often crippling dilemmas people face, and the impact a call with a trained expert can have.

In a landscape where communities are lacking connection, where neighbours don’t drop in for tea, families don’t spend quality time and friendships take place in text messages, more people feel they don’t have anyone to talk to about the challenging and tricky issues that they are facing.

Ethi-call is a free and independent service. It allows callers to share their troubles, explore their options and think about a path where perhaps there was none before.

Delicately sharing the challenges of two callers to the service, Sally showed the breadth of issues the service can help shine a light on. Whether it’s a young Australian choosing between duty and desire, the very hard choice many of us face around aged care for our ageing parents or a rural farmer forced into making the most heartbreaking choices due to drought, choice is a shared human experience and one that we don’t have to face alone.

Ethi-call only works if people use it. And to use it, they need to know it exists. Sally’s hope was to raise enough funding to let more people in need know that this vital service exists and to upgrade call technology to support additional privacy, a barrier to calling for potential users in the past.

Donate here: https://www.thefundingnetwork.com.au/ethics-centre

3. Plant the seed for a better ideas and fund a Young Philosopher

Dr Matt Beard is a philosopher who knows the value of a curious mind. It’s that itch that makes you wonder why the world is the way it is, that drives you to question what you’ve learnt to find a better way. He’s spent his working life scratching that itch.

Philosophy, Matt believes, is curiosity in motion. The history of philosophy is littered with world-changers. And the history of world-changers is littered with philosophy like Martin Luther King, and the foundations of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It’s not just that they changed the world. It’s they were fuelled by the work of philosophy and philosophers.

At The Ethics Centre, we’ve spent thirty years developing new ideas and better worlds. We haven’t always gotten it right, and we’ve never done it alone, but there’s been one constant throughout the process – philosophy. From Primary Ethics in schools teaching children how to think critically, to Short & Curly downloaded over one million times, to Ethical by Design, a research paper that introduces much needed principles for designing ethical technology.

As one of just two philosophers on our staff, Matt says there are less philosophers, and less diversity of ideas than we need to address all the issues rising up out of the cracks in Australia. He says the ideas and possibilities for creating powerful positive change are endless, such as teaching ethics classes prisons, lowering recidivism rates, rethinking media ethics and the limits of free speech or understanding and addressing hate speech and political division in Australia.

But what we don’t have is the capital to support growing our staff. With more funding we can recruit, mentor and house the next generation of budding young philosophers at The Ethics Centre.

Donate here: https://www.thefundingnetwork.com.au/ethics-centre

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Article

Ethics Explainer: Respect

ArticleBeing Human

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Accepting sponsorship without selling your soul

Accepting sponsorship without selling your soul

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance 12 NOV 2019

The artistic director of the Sydney Festival Wesley Enoch does not shy away from controversy. So it’s no surprise he’s rattling cages with his views on artists accepting money from sponsors with unpalatable policies.

Take the money, he advises. Then use it to create work that expresses your opposition.

“I’m quite compromised a lot in the jobs I’ve done because you’re constantly looking for clean money. You are constantly looking for money that has no stigma attached to it and that comes from the joyous valuing of life,” he says.

“And I don’t think that exists. What you do with it is the most important thing.”

The CEO of the Biennale of Sydney, Barbara Moore, shares his view.

“If an arts organisation takes the position of determining right from wrong in a binary system, we’re not going to have very much art funding left,” she says, pragmatically.

Rather than focusing on the differences, arts organisations should be looking at where their values align and what they can achieve together, she says. Where there is dissent, an event such as the biennale should be a “safe space” to have a difficult discussion about it.

What these two cultural leaders are saying is that artists who feel ethically compromised by accepting money from governments or companies with whom they disagree may be missing a greater opportunity to be heard.

Enoch says his job is to articulate his own values and then let others make their decisions about whether they will sponsor the organisations he leads. However, the sponsorship has to be at “arm’s length”, he says.

“My job is to articulate my values and let others make their decisions. If that means sometimes biting the hand that feeds you, then so be it,” he says.

Enoch says he has a “very complex” relationship with governments, which are major sponsors of the arts, but also promulgate policies he disagrees with – such as mandatory sentencing and offshore detention centres.

“Do I take the money from governments? Yes. Do they stop me from speaking against them? No. And that’s the big thing for me.”

Enoch says he uses the same framework for corporate sponsorships and philanthropy. “They have to support me in doing what I’m doing.”

In 2014, the Biennale of Sydney was hit by a sponsorship crisis when it lost its principal funder, Transfield Holdings – the private company of the Belgiorno-Nettis family. The family, which founded and funded the biennale for 41 years, withdrew from the event after artists threatened a boycott over the role Transfield Services played as a contractor for Australia’s network of immigration detention centres.

At the time, the family-owned Transfield Holdings was a shareholder of facilities manager Transfield Services. It has since sold out its interest in the company.

Luca Belgiorno-Nettis, stepped down as chair of the biennale, even though the contract for the detention centres was awarded two years after he and his brother Guido had stepped down as directors of Transfield Services. They had stopped being directors in 2012, and the contract was awarded in 2014 – the same year as the biennale.

The family company sold out its 11.3 per cent shareholding in Transfield Services after the controversy and Spanish company, Ferrovial, became the new owner of Transfield Services (now called Broadspectrum) in 2016 and announced it was withdrawing from its involvement in detention centres.

Moore, who was head of benefaction (philanthropy) at the time, says it was a difficult time for the family, which she indicates had views on the issue that were more aligned to those of the artists than the protesters may have realised.

But only a couple of weeks away from the biennale’s opening, that aspect of the issue was lost in the “static”.

“We were caught off guard in a media storm,” she says.

The controversy, although painful at the time, did not have an impact on the future of the event. After a government review that confirmed the cultural importance of the biennale, the Neilson Foundation stepped in to take over principal sponsorship and now 45 per cent of the funding comes from three levels of government, with the remainder coming from private philanthropic sources.

“Actually, it has made us stronger because it was a moment for us to pull back and remember what our core values are,” says Moore.

Moore says she regrets that the Transfield controversy ended the partnership and was not used, instead, as an opportunity to engage artists and others around the issue of detention centres.

“We would absolutely take Transfield on as a partner again,” she says.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

New framework for trust and legitimacy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

We are on the cusp of a brilliant future, only if we choose to embrace it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

This tool will help you make good decisions

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

If it’s not illegal, should you stop it?

If it’s not illegal, should you stop it?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith Cris 12 NOV 2019

Gambling addict, David Harris, made a sincere attempt to put himself out of harm’s way. Owing $27,000 on three credit cards, he turned down an offer to increase his credit limit and informed the bank about his addiction.

Eleven days later, the bank offered him yet another increase.

Harris, a roofer by trade, borrowed $35,000 from his boss to repay his debts and the two of them went into a bank branch to close his account, but were told they had to talk to the bank by phone. When they called, they were told to visit a branch.

He cut up his credit card, but then later applied for another and quickly ran up a gambling debt of around the same amount. During all of this, he had been “peppered” with numerous unsolicited offers to increase his credit limit.

By the time Harris’ case was detailed in the Banking and Financial Services Royal Commission last year, his bank (the Commonwealth Bank) had already acted to restrict credit increases and credit card offers where problem gambling is identified.

Today, the bank has a Financial Assist Sensitive Matters team to provide financial assistance and guidance. Customers can also ask for a “gambling and cash block” to be put on their credit card to try to stop transactions that may be used for gambling.

However, at the time of Harris’ disclosure of his addiction to the bank in 2016, there were no processes in place pass that information to the parts of the bank assessing the creditworthiness of its customers.

The bank had not just enabled Harris to use borrowed money for gambling. By putting continual temptation into his path, it was also making it virtually impossible for an addict to stop.

Helping problem gamblers help themselves

Since the Royal Commission handed down its final report in February, other banks have also stepped up to help problem gamblers help themselves. The Bank of Queensland, Citibank and the Bendigo Bank have banned the use of credit cards for online betting.

In July, Macquarie Bank became the first of the larger banks to block credit card transactions for nights out at a casino, lottery tickets, sports betting and online gambling. The card will be declined regardless of whether the user has a problem with gambling. Macquarie has also capped cash advances at $1000.

Some banks offer customers the option to block their credit cards (with a 48-hour cooling-off period) and turn off credit card use for online transactions.

While those lobbying for safeguards have applauded these measures, there are inevitable counter-claims that they impinge on people’s freedom of choice.

The CEO of the peak body for financial counsellors in Australia, Financial Counselling Australia, Fiona Guthrie, says that efforts to put in safeguards are always met with the same protests.

“We get that argument all the time: that gambling is not illegal and so people have choices,” she says.

“The unspoken reason is that they would lose market share. They would not make as much money.”

“But, for me, it is like wearing seatbelts – making sure we don’t do things that are harmful. And the idea that you would borrow money and use it for gambling is clearly got to be a harmful practise.”

Choice is ‘moot’ when you are an addict

While some may argue that banks do not have the right to interfere in personal spending choices, Guthrie demurs, saying that banks have always decided what purposes are suitable for the credit they provide.

“Commercial organisations make decisions all the time about who they will engage with, who they will sell to and how they will sell and on what terms.”

Financial Counselling Australia director of policy and campaigns, Lauren Levin, says “Freedom of choice” becomes moot when someone is in the grip of an addiction: “They are not like everyone else”.

CBA executive general manager for retail, Clive van Horen, spoke about the freedom of choice argument in the Royal Commission when asked if his bank could identify whether people who apply for credit limit increases are spending large amounts on entertainment, takeaway food, alcohol, tobacco or gambling.

Van Horen replied: “With limits, yes we can. Ought we to? That’s a question of interpreting the guidelines”.

“The challenge we have as a bank is gambling is legal and, therefore, the choice – choice we’ve grappled with – is at what point do we say it’s not okay for an adult to choose how much to spend on different activities?

“You can quickly see the slippery slope that puts us on if we say ‘you can’t spend on gambling’. Well, then, what about other addictive spending on shopping or on alcohol or any other causes? This is what we’ve grappled with.

“Absent any clear legal or regulatory guideline, how do we determine when we intervene and impose limits?”

Lump-sum payments are also at risk

Levin argues that “doing nothing” is not a neutral position: “It comes with a really significant cost”, she says, pointing to the personal fallout from problem gambling.

Aside from the use of credit for gambling, the government and finance sector also need to turn their attention to the preservation of lump-sum payments and the proliferation of “payday lenders”, she says.

People who receive a lump sum of superannuation money or compensation for illness or accident are also vulnerable to blowing the lot on gambling, especially if they are in chronic pain, on heavy medication or suffer a mental illness such as depression.

Levin says people can transfer any amount of their own money into a gambling account without restriction. She remembers one man lost $500,000 compensation money in four months.

“People using their own money are desperate for tools that could help them not be damaged at a time when they are particularly vulnerable.” Levin says she would like to see banks provide a safe place to preserve the lump sum and a product that offers an income stream to those who have a problem with gambling.

Guthrie says she would like the Government to enact the recommendations from the review of Small Amount Credit Contracts (payday loans), including the proposal to cap repayments on these products to 10 per cent of a consumer’s net income per pay cycle.

“This would prevent over-commitment,” says Guthrie.

While the use of payday loans is common for problem gamblers, it is also true that regular payments to gambling sites is a “red flag” in terms of risk and is one of the top reasons for the rejection of a payday loan application.

Online payday lenders often promise money in your bank account within an hour of approval. They offer amounts of up to $2,000 with a contract term of between 16 days and 12 months and, in some cases, charge more than 400 per cent for payday loans and 800 per cent for consumer leases.

According to constitutional lawyer and activist Shireen Morris, 40 per cent of people who get a payday loan are unemployed, one-quarter get more than 50 per cent of their income from Centrelink, and the average number of loans per borrower is 3.64.

“One case study of loans taken out by Centrelink recipients showed a $700 washing machine ended up costing $2176, a $345 dryer ended up costing $3042 and a $498 fridge ended up costing $1690,” she wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethics in engineering makes good foundations

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The dangers of being overworked and stressed out

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The truth isn’t in the numbers

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY Cris

Do we have to choose between being a good parent and good at our job?

Do we have to choose between being a good parent and good at our job?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 6 NOV 2019

I’m half writing this, half thinking about whether it is the best use of a few precious, toddler-free moments.

“Framing the issue of work-life balance – as if the two were dramatically opposed – practically ensures work will lose out. Who would ever choose work over life?” writes work-life guru Sheryl Sandberg.

Who indeed?

Well, for one, those who can’t afford to walk away from a job. Unless you’re living very comfortably, you’ll usually be forced to choose work over life. But even setting aside the many people who find themselves in that situation, it’s not clear we live in a world that enables people to choose life over work. Take me, for example.

Today is Friday. It’s the beginning of my three-day weekend. Thanks to flexible working arrangements, Friday is my father-son day. We go to the park, get errands done, pop out to the zoo – it’s brilliant, and I wouldn’t swap it for anything. You’d think I’m the perfect demonstration of Sandberg’s argument, but I’ve got itchy feet. So here I am, writing an op-ed.

Or rather, I’m half writing, half thinking about whether this is the best use of a few precious, toddler-free moments. Would I rather get things done around the house and revel in the simple, domestic bliss of a clean kitchen or a floor free of stickers, marbles and other paraphernalia?

I feel this back-and-forth all the time. It’s a war of identities: the professional version of me is ambitious, busy, focused and demanding; domestic me is patient, spontaneous and calm (for the most part). To be honest, it’s exhausting, and it’s beginning to make me think we haven’t fully figured out what work-life balance really means.

At the moment, we think about work-life balance in terms of the way we allocate our time. A well-balanced life is one in which you can leave work at a reasonable hour, spend enough time on parental or annual leave with loved ones, and where parents can balance care obligations to enable both people to have flourishing lives and careers.

“A well-balanced life is one in which you can leave work at a reasonable hour, spend enough time on parental or annual leave with loved ones, and where parents can balance care obligations to enable both people to have flourishing lives and careers.”

A look at recent proposals in the work-life balance seems to support this: the four-day working week, gender-balanced leave policies, email restrictions and unlimited annual leave all march to the beat of the time-maximisation drum.

This is where I think Sandberg is right – there is something wrong with painting work and life as diametrically opposed, but it’s not what she thinks. It’s because it permits a world in which “work” and “life” are kept totally separate and are permitted to operate according to different norms and values.

My favourite example of this is the unintended viral sensation Robert Kelly, his kids Marion and James and his wife Jung-a Kim, who together conspired to make the best couple of minutes of television in BBC history. After the incident, Kelly copped criticism from some circles for failing to be a good father because he didn’t scoop his daughter up and pop her on his knee during an international broadcast interview. By contrast, the BBC praised Kelly for his professionalism.

Whether Kelly did the right thing or not depends on how you define him in that precise moment. Was he a father or a professor? For Kelly, in the midst of that moment, the dilemma is the same: who should he choose to be, right now?

Unfortunately, based on our current norms around professionalism, he can’t be both at the same time. According to the scripts he seems to have been judged by, Kelly needed to be detached, rational and stoic and simultaneously warm, unconditionally affectionate and responsive. And this is why I think the work-life balance discussion needs to go beyond time and begin to think about identity. We need to permit people to express their domestic identities in the workplace – to redefine what it means to be professional so that it’s not unrecognisable to the people who know us in our personal lives.

These are all good things, but I’m not sure they can do the job on their own. Australian men often don’t take all the parental leave they’re entitled to. There’s little point giving people all this time if those people don’t know what to do with it, or aren’t equipped to use it as they should.

“As we continue to deconstruct unhelpful, gendered divisions of labour that force women to take on domestic and emotional labour and leave men to seek paid employment, there’s a good chance more people are going to start facing these choices – between professional and domestic life.”

“As we continue to deconstruct unhelpful, gendered divisions of labour that force women to take on domestic and emotional labour and leave men to seek paid employment, there’s a good chance more people are going to start facing these choices – between professional and domestic life.”

This isn’t just important for wellbeing. Bringing “domestic virtues” of emotional expressiveness, vulnerability and the like into the workforce helps shape people’s character. Our environments shape who we are. The more we’re encouraged to be competitive, ambitious or whatever else in the workplace, the harder it will be to switch gears and express patience, humility or generosity at home.

The purpose of work-life balance is to help people to flourish, live happy lives outside of work and develop into well-rounded human beings. If we’re going to do that, we need to let people be well-rounded at work too.

This article was written for, and first published by The Guardian. Republished with permission.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Explainer, READ

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Immanuel Kant

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

We are pitching for your pledge

In celebration of our 30th anniversary which kicks off in November this year, we are preparing our very first live-crowdfunding ‘Pitch + Pledge’ night on Thursday 14 November.

Meet and hear directly from leaders of three of our flagship programs: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Ethi-call and our Young Philosopher initiative. Each speaker will pitch live on stage for six minutes each, and then answer the audiences questions. What follows is an unforgettable live-pledging experience, based on The Funding Network’s popular format.

1. Support a Truly Independent Festival of Dangerous Ideas

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas is Australia’s original big thinking festival – bringing leading minds from around the world to explore life’s most problematic and divisive issues.

Delivered in partnership with Sydney Opera House for almost a decade, last year marked the start of an exciting new phase for FODI as we branched out on our own. The 2018 festival was a triumphant sell-out, and audiences told us they walked away with a feast of new ideas and perspectives.

While FODI is well-attended and widely loved, it’s also a hugely risky and expensive event to stage. Our insistence on finding the best international storytellers, and keeping ticket prices affordable for broad audiences, pushes us into uncomfortable financial territory.

Your support will help us stage FODI as a break-even event, and allow us to keep doing it, year after year.

2. Help Us Reach More People in Need with Ethi-call

We’re enormously proud of Ethi-call. It’s our free, independent, national helpline available to all. The service provides expert and impartial guidance to help people make their way through life’s toughest challenges, when there’s nowhere else to turn.

Calls can be about almost anything – from professional issues (fraud, corruption, conflicts of interests) through to the deeply personal (birth, death, relationships, families).

There’s no other service like Ethi-call, so we receive calls from all over Australia, and all over the world. Your assistance will allow us to train more counsellors and ensure more people in need know the service exists.

3. Fund a Young Philosopher

Thirty years ago, a young philosopher with a keen interest in ethics and democracy, Dr Simon Longstaff, was appointed as The Ethics Centre’s first employee and Executive Director – a position he continues to hold today.

We’ve engaged a number of budding minds over the years to bring fresh thinking to our work, most recently Dr Matthew Beard, who plays an increasingly vital role in what we do.

We’re seeking funding to secure another bright young philosopher into our team – to apply their learnings to deliver insights and tools to help people build the skills and capacity to live according to their values and principles.

An opportunity to create a ripple effect of change

It will be a highly engaging and memorable evening for everyone involved and is an opportunity for you to get involved in some very exciting, critical projects here at The Ethics Centre.

We are putting our hearts and work on the line for your support. Pitch and Pledge will kick off at 5.30pm Thursday 14 November, at Clayton Utz offices, 1 Bligh St Sydney. Pledging starts from $100.

Please RSVP to rosemary.smithson@ethics.org.au with your details and your guests’ names to book your place to join us.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Article

Ethics Explainer: Respect

ArticleBeing Human

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why trust-building strategies should get the benefit of the doubt

Why trust-building strategies should get the benefit of the doubt

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker Cris 31 OCT 2019

You can’t blame people for feeling cynical. These days, it seems smart to distrust the motives of others and assume their every action is powered by self-interest.

You can’t go wrong expecting the worst, right?

There are so many reasons to be continually on your guard in an era of “alternative facts” and fallen idols. In recent times, all pillars of our society have revealed some rot at their core, whether it be in business, politics, media, religion, science or sport.

Scandalised headlines and royal commissions have lost their capacity to shock, yet there is still an argument for expecting moral behaviour from business. And there is a gulf between reasonable caution and cynicism.

Good things – positive progress – cannot happen unless we allow ourselves to believe in and support them.

I think most of us would consider ourselves to be altruistic, ready to put aside our self-interest (at least some of the time) for the benefit of others or a greater cause. And we know others who would behave the same way.

Common sense should then tell us that organisations and industries contain people whose days are powered by good intentions – even if the organisations they work within are caught up in unethical practices.

However, when those people get together to create positive change, the best way to kill it off is with an eye roll, shrug and disbelieving attitude.

In January this year, the energy industry’s Energy Charter took effect, with its 18 signatory companies in the electricity and gas industries voluntarily agreeing to disclose how they are measuring up to a set of principles that require businesses to:

- Put customers at the centre

- Improve affordability

- Provide safe, sustainable and reliable energy

- Improve customer experience

- Support customers who are in vulnerable circumstances

Having aggravated customers with inconsistent service and high prices, the industry itself accepted its effort to regain the public’s trust would be greeted with an “oh yeah?” by a disillusioned and distrustful public.

Electrical Trades Union of Australia national secretary, Allen Hicks, was reported as saying the charter was nothing but a “fig leaf” allowing the same for-profit practices to continue while real problems went unaddressed.

Energy Users of Australia chief executive, Andrew Richards, greeted the initiative with what he said was a “healthy scepticism”, while the NSW Energy and Water Ombudsman, Janine Young, said “positive cynicism” would be a more appropriate lens than blank disbelief.

Signatories to the charter submitted their first disclosure reports in October and the Energy Charter Independent Accountability Panel will publish an evaluation report on November 29.

The transparency of the process, in publishing the self-assessments of the signatories, should go some way to dispelling scepticism about the motivations and commitment of the participating businesses. I recently attended the Energy Charter Industry Working Group workshop where members articulated the challenges and learnings of the process. Industry regulators were present to hear the feedback, warts and all. It was a unique experience where fierce competitors came together, showed their vulnerability and contributed to creating a more sustainable industry.

When reading through the energy companies’ self-assessments, the wider community should acknowledge the honesty of owning up to mistakes or their failure to meet expectations.

The Banking and Finance Oath (The BFO) – which I have worked with for over 5 years – is another initiative to earn trust and has also had to combat sceptics and cynics. The BFO asks individuals to hold themselves to account.

While the number of signatories is relatively low, given the size of the industry, there are strong indications it is starting to make headway. Around 3,000 people have committed to the following principles:

Trust is the foundation of my profession

- I will serve all interests in good faith.

- I will compete with honour.

- I will pursue my ends with ethical restraint.

- I will help create a sustainable future.

- I will help create a more just society.

- I will speak out against wrongdoing and support others who do the same.

- I will accept responsibility for my actions.

In these and all other matters; My word is my bond.

In a speech at The BFO conference in August, chairman of APRA, Wayne Byres said initiatives such as the Oath are important building blocks for a stronger, more efficient, and more sustainable financial system. “They should be welcomed and embraced by industry leaders.”

When people ask whether the Energy Charter or The BFO are going to make a difference, they need to look to the longer term, rather than expecting immediate results. There needs to be a level of tolerance for mistakes and a willingness to allow time for correction.

While publicly holding themselves to a high standard, there are no quick fixes to culture change, and many of the problems that beset both sectors cannot be solved without political support and regulatory reform.

Coming back to the point about whether cynicism is a smart approach when it comes to assessing the motives of others, psychology has some pointers.

It is commonly believed that cynicism is a sign of intelligence, yet psychological research shows no such correlation. Instead, studies show that people who perform well in cognitive tasks are less cynical.

“ … holding a cynical worldview might represent an adaptive default strategy to avoid the potential costs of falling prey to others’ cunning,” say social psychologist Olga Stavrova of Tilburg University in the Netherlands and evolutionary psychologist Daniel Ehlebracht from the University of Cologne in Germany. Studies on the relationship between trust, health and finances find that thinking the worst tends to lead to worse results.

The psychologists cite US comedian Stephen Colbert, who told a university graduating class: “Cynicism masquerades as wisdom, but it is the farthest thing from it. Because cynics don’t learn anything. Because cynicism is a self-imposed blindness, a rejection of the world because we are afraid it will hurt us or disappoint us.”

Let’s hope the development of these voluntary initiatives that encourage self-reflection and accountability are met with a healthy scepticism, rather than a reflexive cynicism that seems to serve no-one.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Who are corporations willing to sacrifice in order to retain their reputation?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

What your email signature says about you

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

BY Cris

Thought Leadership: Ethics in Procurement

Ethics in Procurement Report: The Ethics Alliance

Ethics in Procurement examines the ethical issues and tensions that arise in payment of suppliers, and provides a framework for ensuring fair transactions.

The Ethics Alliance is a corporate community, designed to share challenges and take a collaborative approach to finding solutions. At our inaugural gathering, an Alliance member called out the crippling impact late payments was having on his business. Through conversation, it became evident this was an issue shared by many members and unintentionally caused by others, and was a problem we wanted to help solve.

This guidebook came together after a series of interviews with members and a follow up roundtable discussion that explored both systemic and principle-based solutions. It examines some of the procurement-based issues identified through that process, looking at the causes of ethical tension and offering frameworks for each stage of the procurement process.

Formulated as a practical solution, the paper considers common challenges including:

- Should companies have an open tender and invite all to bid, or save time and money by targeting known suppliers?

- Should companies accept the cheapest complying bid, or pay more to a company that distributes a proportion of its profits to a good cause?

- Should companies be transparent in their dealings with suppliers, or will this open them up to disputes?

- Is it reasonable for companies to impose a significant administrative burden in the first round of a tender process by asking for information which is not directly relevant to the project in question?

Plus, it provides a framework to make payment processes fair, practical and ethical.

"Organisations that are buying goods or services can encounter many forks in the road, requiring decisions on how to respond. By viewing those questions through an ethical lens, we are more able to make decisions that align with the purpose, values, and principles that our organisations are committed to - and that we may hold as individuals."

WHAT'S INSIDE?

Ensuring a fair transaction

Looking after your suppliers

Practical issues to be solved

Reasons you might have a problem

A practical framework

An ethical framework

AUTHORS

Contributors

Writing and Research

Ben Robinson lead the writing and research for this report. He has worked in various roles at The Ethics Centre since 2016. Ben studied Philosophy and Political Economy at the University of Sydney, and is a Graduate Ethics and Sustainability Consultant at Deloitte.

Member contributions

The following Ethics Alliance members generously gave their time to talk to us about the procurement issues affecting their business: Shell Australia, Macquarie Bank, Clayton Utz, The Reserve Bank of Australia, Allianz, TrinityP3, The Business Council of Australia, AIA Australia and Insurance Australia Group (IAG).

A special thank you to Shell Australia who generously shared their market leading approach to procurement with The Ethics Alliance, providing the context and structure for the practical framework offered in this report.

You may also be interested in...

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Raewyn Connell The Ethics Centre 15 OCT 2019

If we ask the question, ‘are men fragile?’ my answer would be that quite a number certainly are.

We can see this in the health data. Men, compared with women, have higher levels of some kinds of mental health problem – especially alcoholism and sociopathic disorders. Men, again compared with women, have higher levels of occupational injury and coronary heart disease, higher rates of completed suicide, and – especially young men – much higher rates of injury and death on the road.

These are all long-standing patterns, and society should provide support in the form of men’s health programmes. We should also ask why these patterns exist – given that men’s bodies are not notably weaker than women’s bodies. Which leads us to the question of masculinity.

If we ask the question, ‘is masculinity fragile?’ the answer looks different. Masculinity is a social pattern, and our societies usually define its hegemonic form in terms of power, aggression, wealth and authority. So it’s mainly men who are recruited to run the world.

We may celebrate a first female leader of some country or firm, but the enormous majority of Presidents, Prime Ministers and CEOs are actually blokes in suits. (93.4% of the CEOs of Fortune 500 corporations this year, for instance.) There have not been all that many women Popes, archbishops, chief muftis, abbots, generals, admirals, Treasurers or Directors of the CIA.

There’s a robust social basis for these patterns. Part of it is economic – for the real “gender gap”, look at the superannuation statistics. Part of it is institutional – even in our lovely universities, four-fifths of full professors are blokes, though admittedly some of them don’t wear suits.

Part of it is cultural – turn on the television, and you are likely to see a screen full of extremely fit young men giving a display of professional skill and force. Those who do it best become famous role models and are given a lot of money. Last year Cristiano Ronaldo took home 61 million dollars in salary from Real Madrid, plus 47 million in endorsements. And he was only the second highest paid footballer.

Of course there are other patterns of masculinity – we should really speak of masculinities in the plural. When the media speak of “toxic masculinity” they are pointing to a specific pattern of masculinity that is bidding for the dominant place by putting down alternatives. We have a spectacular example in the career of Mr Trump – it’s hard to miss the element of resentment and revenge in his story.

The patriarchal gender order is not a perfectly-functioning machine. Indeed, since the days of President Eisenhower and Sir Robert Menzies it has seen a deep erosion of legitimacy. What would they have made of the gay marriage survey! Well, we get a glimpse in the current authoritarian backlash around the world. Which goes to show, not that masculinity is fragile, but that gender orders change. They can change for the worse; I live in hope they will change for the better.

Raewyn Connell was one of the speakers at our IQ2 Debate ‘Masculinity – is it really so fragile?’. The debate took place at Sydney Town Hall Wednesday 23 October. She was joined by Catharine Lumby, Zac Seidler and David Leser. Watch the full debate here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

BY Raewyn Connell

is one of Australia’s leading social scientists, specialising in class, gender, education, global patterns in knowledge, and most prominently, masculinity. She is one of four speakers at our upcoming debate, 'Masculinity – is it really so fragile'.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Free speech has failed us

I used to believe in free speech. I used to believe in the power of rational discourse.

I used to believe in what Jurgen Habermas called the “unforced force” of the better argument. I used to believe in John Stuart Mill’s riff that free speech is what keeps superstition and stifling tradition at bay. I used to believe the solution to an abundance of bad speech was more speech.

However, I’m currently going through a somewhat unsettling process of reconsidering these deeply held views. The last two decades has been one long demonstration of the failures of public discourse to drive towards better solutions to the problems we face.

I hardly need to cite the failure of public discourse to prevent the folly of the wars following September 11 and the catastrophic regional destabilisation they caused, or to reform the economic institutions that caused the Global Financial Crisis, or to improve the response to it that ended up bailing out the perpetrators at the expense of the victims, or bring peace to the escalating culture wars that are fracturing nations, or prevent the national self immolation that is Brexit, or stop the election of a dangerously ill-informed narcissist of dubious moral character to the Presidency of the United States, or combat the ongoing misinformation campaign that is resisting action on one of the world’s most urgent challenges: dealing with climate change. And that’s not even an exhaustive list.

Free speech has failed to live up to its liberal promise. It has failed to float the best reasons and arguments to the top and sink the worst ones to the bottom.

Free speech has failed to live up to its liberal promise. It has failed to float the best reasons and arguments to the top and sink the worst ones to the bottom. It has failed to prevent those who actively work to pervert speech from winning over the voting public. It has empowered those who would wilfully employ their reach to promote their ideological agenda. Meanwhile, those who stick to the rules of rational discourse are left shuffling footnotes and politely yelling reasons into the void.

So when The Conversation announced recently that it will be taking a “zero-tolerance approach to moderating climate change deniers, and sceptics” in the comments on its articles, I was not shocked.

Once upon a time, we viewed #ClimateChange sceptics as merely frustrating. Not anymore.

As a publisher, we won’t perpetuate ideas that will destroy the planet.@mishaketch explains @ConversationEDU‘s zero-tolerance for climate deniers: https://t.co/VbRmFWWycC

— The Conversation (@ConversationEDU) September 18, 2019

Only a year ago, I would have agreed with the ABC’s Media Watch that “The Conversation is wrong to ban anyone’s views, unless they’re abusive, hateful or inciting violence.” I would have defended the right of the ignorant, misinformed and outright malicious to say their piece and have it shredded by other less ignorant, more informed and hopefully charitable readers.

After all, what’s the alternative? We shut down speech and enable one particular narrative to dominate? Who’s in charge of that narrative? Can we trust them to have more reliable access to the truth? What do we do if that narrative is wrong?

I’m still painfully aware of the importance of these questions, and how hard they are to answer in any satisfying way. And yet, the evidence is clear to me now that in many cases more speech is not always in the best interests of truth or humanity.

In good faith

What has fundamentally changed in recent months is the way I think about free speech and the possibility of rational discourse in general.

Free speech is not an absolute good; it is not an end unto itself. Free speech is an instrumental good, one that promotes a higher good: seeking the truth. That’s the canonical account from John Stuart Mill that still underlies much of our thinking around free speech today.

But free speech only fulfils its truth-seeking function when all agents are speaking in good faith: when they all agree that the truth is the goal of the conversation, that the facts matter, that there are certain standards of evidence and argumentation that are admissible, that speakers have a duty to be open to criticism, and that there are many modes of discourse that are inadmissible, such as intimidation, insults, threats and the wilful spread of misinformation. Mill assumed all too readily that such good will was commonplace.

But free speech only fulfils its truth-seeking function when all agents are speaking in good faith.

This doesn’t mean that all speech is truth-seeking. In fact, most everyday speech is not about the truth at all. Usually the correct answer to “does my bum look big in this” is “no”, irrespective of the truth. Most speech is about reinforcing relationships, establishing identity or passing the time. Some speech is about subjective issues or values which may not admit true or false answers. Free speech protects this too. But for some speech, the facts do matter, and that’s where free speech is failing us.

In order for truth-seeking free speech to work, we need strong social norms that promote good faith. And it’s precisely these norms that have broken down in recent years (not that they were ever very strong). And this is because humans are not nearly as rational as we (or Mill) would like to think. And we’re painfully easy to manipulate.

When I teach critical thinking, I give the usual cautionary spiel about not flinging out argumentative fallacies, like the old ad hominem, ad populum or slippery slope. But the very fact that I have to give that spiel is because these fallacies work. When employed effectively, you’ll “win” a lot more arguments using fallacies than by playing by the rules – if you consider persuading/intimidating/misleading someone to accept your point of view a “win.”

I similarly caution students to be wary of the power of appeals to emotion and the force of social pressure, and to be mindful of cognitive biases that can lead our thinking astray. Again, these are important because they are the mechanisms that actually motivate many of our beliefs and that can be most effectively used to persuade others.

What I don’t say – but maybe I should – is that critical thinking is useful when it comes to policing one’s own thoughts, but it’s pitifully impotent when it comes to changing others’ minds. If you start throwing syllogisms across the dinner table, or politely point out that someone is affirming the consequent at the pub, or hope that revealing the contradictions embedded in someone’s assumptions in a comment thread on Facebook is going to change their mind, you’re quickly going to find out you’ve joined the ranks of those politely yelling reasons into the void. I know only too well what that feels like.

Anti-social media

Compounding this is the fact that we have gone to great lengths to build new technologies that promote the worst features of bad faith discourse. If you wanted to design a means of communication that made rational argumentation as difficult as possible yet rewarded the use of every argumentative fallacy under the sun, you’d be hard pressed to top Twitter. It only allows enough characters to express conclusions, not premises. The Like button gives the same weight to the expert as the ignoramus. Status is earned through number of followers, which is like institutionalising the fallacy of ad populum.

Facebook is just as bad for different reasons. Not long ago, if you had a penchant for conspiracy theories, racial vilification or fringe anti-science theories, you’d be hard pressed to find enough like-minded nutjobs in your neighbourhood to hold a bi-monthly tin foil hat dinner. Now, you can join with thousands of like-minded cranks from all around the world on a daily basis to reinforce and radicalise your views.

There’s also evidence that a group of people with diverse views will tend to gravitate towards the most extreme views in the group. And that people who believe one conspiracy theory tend to believe in and share many. And that cultivating outrage only promotes more animosity towards one’s perceived opponents and encourages greater retributive invective and bad faith.

There’s also abundant evidence that people find falsehoods to be more credible the more often they encounter them, even if they’re posted by someone who’s debunking them. As such, falsehoods spread more easily on social media than facts. So the outrage industry is self-sustaining, as even those raging against them share them with their friends, thus spreading the poison even further. (This is why I urge everyone to STOP SHARING GARBAGE on social media, even if you’re intending to debunk it, but particularly if it just pisses you off. The beast feeds on your friends’ eyeballs.)

Add the well known bubble effect, which filters out dissenting views and reinforces in-group identity, and bad faith is all but guaranteed. Free speech in this context only facilitates a slide away from the truth.

That being so, it’s with some alarm that I note that Facebook is now exempting politicians from its normal community standards – the same standards that are intended to prevent bad faith discourse like hate speech and harassment. According to Facebook’s new VP of Global Affairs and Communications, the former UK politician Nick Clegg, it’s because Facebook’s crew “are champions of free speech and defend it in the face of attempts to restrict it. Censoring or stifling political discourse would be at odds with what we are about.”

Clegg invokes a tennis analogy to describe Facebook’s approach to speech: “our job is to make sure the court is ready – the surface is flat, the lines painted, the net at the correct height. But we don’t pick up a racket and start playing. How the players play the game is up to them, not us.”

Here’s a better analogy. The court was never flat. Human psychology means it started off warped, and it’s twisted even more by the technology created by Facebook itself. The players know this, and some are exploiting it to their advantage, and to humanity’s disadvantage. If free speech is meant to do anything at all positive, then it takes active intervention to flatten the court, not a hands-off wilful abdication of responsibility.

If free speech is meant to do anything at all positive, then it takes active intervention to flatten the court, not a hands-off wilful abdication of responsibility.

Hit prediction: this policy is going to be a disaster, and Facebook will revoke it with grievous apologies either before or after the 2020 US Presidential election after a spate of heinous posts by politicians are left to fester on our feeds.

What worries me the most is that those who understand the failings of free speech the best are the ones who know how to use speech to manipulate us to their ends. It’s the political operatives, the Cambridge Analytica’s, the climate change deniers, the alt-right meme machines, the political demagogues. They are the ones who benefit the most from free speech, not the experts, not the scientists, not the academics, not those individuals who are willing to do some homework and engage in good faith with an open mind.

So, to those who care about facts, evidence and the power of rational discourse to help us arrive at the truth, I say: WAKE UP. We’re losing, and with us, truth and humanity. The mongers of misinformation and agents of bad faith are driving us into the dirt, and we’re down here tilling the very soil that allows the weeds to flourish.

Shut it down

Free speech has failed us. That’s why I think The Conversation is justified in banning certain forms of well established misinformation on its site, whether it’s delivered by trolls or people who are misguided enough to believe it.

The Conversation as a website is predicated on the importance of expertise. It only publishes articles by qualified academics, and only allows them to write on areas in which they are experts. It encourages a diversity of views and debate amongst its authors. I know, because (full disclosure) I used to work there, editing the science and technology section. True to its name, The Conversation also wants to encourage discussion and debate amongst readers. But it is in no way obliged to give a platform to anyone. It is able to determine the standards of discourse in its own domain.

So if the “conversation” in the comments section slips well outside the bounds of respect for evidence, reason or good faith discourse that The Conversation seeks to promote, then it ought to be allowed to disqualify it. It’s not like the readers can’t spread their views on other platforms with lower standards. Sadly, there’s an abundance of those around these days. Freedom of speech doesn’t require everyone to allow just anyone to walk into in their garden and plant whatever they want.

Freedom of speech doesn’t require everyone to allow just anyone to walk into in their garden and plant whatever they want.

That said, I am convinced that we need some forums where free speech can operate in an expansive way. At the moment, I think universities are the best candidates, which is why I resist the deplatforming of academics or speakers on campus, no matter how controversial their views. Universities need to get better at managing this, because they’re one of the last bastions of truly open enquiry.

But I’m increasingly coming to believe that we need to get real about the failures of free speech in many public forums, and fight back against those who would pollute discourse with bad faith. I’m not convinced we should go as far as Herbert Marcuse, who argued that civil discussion was futile, so all that’s left is violence. But I do think we can’t maintain the naive position that “more speech is always a good thing.”

The paradox of free speech

I’ll be the first to say I don’t know what to do. But I have some initial ideas. I suspect there’s a short term and a long term solution. In the long term, we want to rehabilitate public discourse by encouraging good faith. That’s a decades long project, and one that will require the rebuilding of a great deal of social capital that has been degrading over decades.

This is not necessarily a project that is conducted through rational discourse itself. Rather, it’s something that requires constructive social discourse. It requires relationship building, the restoration of trust, the separation of belief from identity, and the buttressing of social norms that make rational discourse a possibility.

And in the short term, I’m increasingly open to shutting down speech that is not only conducted in bad faith, but is polluting discourse itself, so encouraging more bad faith. The problem of dealing with speech that corrupts speech is related to Karl Popper’s famed “paradox of tolerance.” If we believe that tolerance is good, how should we treat those who are intolerant? If we tolerate them, won’t they end tolerance? And if we don’t tolerate them, doesn’t that make us intolerant?

The solution to this paradox is elegantly expressed by Peter Godfrey-Smith and Benjamin Kerr in an article published on – ironically enough – The Conversation. Godfrey-Smith argues that in order to protect “first-order” of tolerance of individual actions – say, certain religious practices or having a homosexual relationship – means we must be “second-order” intolerant of actions that are themselves intolerant of these actions, and it’s in no way contradictory or hypocritical to do so. That’s why we have anti-discrimination laws that are explicitly intolerant of intolerance.

Similarly, in order to protect the power of free speech to help seek the truth, I think we need to be more intolerant of speech that subverts the very possibility of speech to seek the truth. Crucially, that doesn’t mean shutting down speech by people who are just ignorant or wrong. What it does mean is shutting down bad faith speech that muddies the waters, that spreads misinformation, that threatens or coerces, or that exploits known psychological biases to mislead.

in order to protect the power of free speech to help seek the truth, I think we need to be more intolerant of speech that subverts the very possibility of speech to seek the truth.

There’ll be a price to shutting down certain types of discourse in some forums. Some legitimate speech may be hampered. But if the price of not doing it is more polluted discourse, more bad faith, more wars, more Brexits, more Trumps, and a world that is more than 4 degrees warmer, then I know which side of the trade-off I prefer.

I still believe in the potential of free speech to seek the truth. I still believe it ought to be practiced in some forums. I still believe it’s something worth fighting to enable and preserve. But I think you only need to look at the last two decades – and speculate about the two decades to come – to realise that our current approach to free speech has failed. And the stakes are high.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Pragmatism

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio The Ethics Centre 8 OCT 2019

Most people believe it is a good idea to help out others in need, if and when we can. If someone falls over in front of us, we usually stop to see if they need a hand or to check if they are OK.

Donating to charity is also considered to be helping others in need, but we may not always see the person we are helping in this case. Even so, charitable donations are viewed as praiseworthy in our society. We receive a sticker for placing spare change into a coin collection tin, and our donations are tax deductible.

Yet most people see donating to charity as a ‘nice thing to do’, but perhaps not a ‘duty’, obligation or requirement. In Kantian terms, it is ‘supererogatory’, meaning that it is praiseworthy, but above and beyond the call of duty.

However, Peter Singer defends a stronger stance. He argues that we should help others – however we can. All of us. This may look different for different people. It could involve donating money, time, signing petitions, or passing along old clothes to those who need them, for example.

If we can help, then we should, Singer argues, because it results in the greatest overall good. The small efforts of those who can do something greatly reduce the pain and suffering of those who need welfare.

In order to illustrate this argument, Singer provides us with a compelling thought experiment.

The ‘drowning child’ thought experiment

From his 1972 article, ‘Famine, Affluence, and Morality’, Singer starts with a basic principle:

“if it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.”

This seems reasonable. He backs this claim up with the following concrete example:

“An application of this principle would be as follows: if I am walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning in it, I ought to wade in and pull the child out. This will mean getting my clothes muddy, but this is insignificant, while the death of the child would presumably be a very bad thing”.

Obviously, we agree, we should save the child from drowning, even if it comes with the inconvenience and cost of ruining some of our favourite, expensive clothes and shoes. The moral ‘weight’ of saving a life far outweighs the cost in this scenario.

Yet, Singer extends this claim even further.

He notes that if we agree with this principle, then what follows from it is quite radical. If we act on the idea that we should always prevent very bad things from happening, provided we are not sacrificing anything too costly to ourselves, this makes a moral demand upon us.

The biggest implication is that, for Singer, it does not matter whether the drowning child is right in front of us, or in another country on the other side of the world. The principle is one of impartiality, universalizability and equality.

I can easily donate the cost of a new pair of shoes to a respected charitable organisation and save a life with the funds from that donation. In the same way as a moral agent would wade into the pond to rescue the drowning child, we can make some relatively small effort that prevents a very bad thing from occurring.

The ‘very bad thing’ may be that a child in a developing country starves to death or dies because their family cannot afford the treatment for a simple disease.

The expanding moral circle

Now, even for those in favour of charitable giving, some may argue that our duty to help does not extend beyond national borders. It is easier to help the child ‘right in front of us’, they may say. Our moral circle of concern includes our family and friends, and perhaps our fellow Australians.

But I am convinced by Singer’s argument that we ought to expand our moral circle of consideration to those in other countries, to those who live on planet Earth with us. The moral obligation to alleviate suffering has no borders.

And we are now most certainly ‘global citizens’. Thanks to our technology and growing awareness of what occurs around the globe, we have outgrown a nationalistic model and clearly inhabit an international world.

Global Citizens

In his 2002 book, One World: the ethics of globalisation, Singer supports the notion of the global citizen which views all human beings as members of a single, global community. The global citizen is someone who recognises others as more similar to rather than different from oneself, even while taking seriously individual, social, cultural and political differences between people.

In a pragmatic sense, global citizens will support policies that extend aid beyond national borders and cultivate respectful and reciprocal relationships with others regardless of geographical distance or other differences (such as those related to race, religion, ethnicity, disability, sexuality, or gender identification).

For a long time now, Singer has also been pointing out that we are all responsible for important issues that are affecting each and every one of us. Back in 1972, he claimed, “unfortunately, most of the major evils – poverty, overpopulation, pollution – are problems in which everyone is almost equally involved.”

And, with our technology, media and the 24 hour news cycle, we are now confronted with the pain and suffering of those distant others in ways that ensure they are immediately present to us. We can no longer claim ignorance of the help required by others, as social media brings their images and pleas directly to our handheld devices.

So, do we have an obligation to alleviate suffering wherever it is found? Does this obligation extend beyond national borders? Should we do what we can to prevent very bad things from happening, provided in doing so we do not have to sacrifice anything too drastic or comparable? (for instance, we need not reduce ourselves to the levels of poverty of those we seek to assist in doing so).

If you answered yes, then you may already think of yourself as a global citizen.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships