Whose home, and who’s home?

Whose home, and who’s home?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith The Ethics Centre 17 AUG 2020

Australian citizens who live overseas and want to return to Australia, with some exceptions, now have to pay for their mandatory two-week hotel quarantine.

This new rule applies for those returning to New South Wales or Queensland. It means that a single adult returning home must have AUD $3000 to pay for their stay. Last week New Zealand announced a similar policy: citizens returning home to stay less than 90 days will be charged for their quarantine.

Announcing the policy, NSW Premier Gladys Berijiklian said “Australian residents have been given plenty of time to return home, and we feel it is only fair that they cover some of the costs of their hotel accommodation”.

The locution of having “been given” time to return home sounded curious to many of us who reside overseas. We were unaware that living elsewhere had been a matter of taking.

In the comments sections of news articles about the announcement, the Premier’s sentiment was echoed by other Australians. A recurring theme appeared: overseas Australians who returned home now are being selfish to expect taxpayer help

What could fairness require, in a pandemic? It is not fair that some people will get COVID and others will not. It is not fair that some will die while others survive. These are circumstances where a question about fairness is simply not askable; there is only tragedy, which does not have a possible equitable distribution.

One way to be unfair in a pandemic might be to expose other people to risk. People arriving from overseas certainly do that, and it is crucial to Australia’s efforts to contain the coronavirus that it curbs the risk from international travellers. Like many other countries, Australia was within its rights to close its borders early to international travellers in recognition of this risk.

The very concept of citizenship, however, prohibits closing borders entirely. No matter where citizens ordinarily live, their government has a duty to allow them to cross the border of their home. This is what it means to be a citizen.

There is a problem of incommensurability here. How does the need to mitigate a biothreat weigh against the standing rights of citizens to cross a border? One is a value of rights and obligations; the other is a value of consequences and threat reduction. Neither of these values presents itself in a standardised unit to be compared against the other.

The question is not quite “how do we make a good decision?” but “which kind of good should we be interested in?”. This is a fairly common problem.

Not all of the things we want governments to provide can be coherently measured against each other, so when they come into conflict, it’s not clear how to even begin making the trade. Privacy against safety, health against freedom, service provision against non-interference.

The Government appears to have chosen fairness as the value to adjudicate between the two. The Premier described the policy as “only fair”, since “Aussies overseas have had three or four months to figure out what they want to do”. Prime Minister Scott Morrison echoed this, saying overseas Australians “obviously delayed [their] decision”, and Winston Peters of the New Zealand First Party said that asking taxpayers to pay for fellow citizens’ quarantine was “grossly unfair”.

There are two features of the decision that challenge the terms of fairness here. One is that it seems only to apply to Australians overseas. We would not, for instance, describe it as “only fair” to deny Medicare coverage to an Australian at home who contracted COVID-19 after breaking quarantine rules, even though there is an argument that this is ‘only fair’. Like the quarantine fee, it would mean that those who had ‘plenty of time’ to follow the rules did not impose a burden on the taxpayer when an emergency befell them.

The second is that it is not clear that fairness is the value we should default to in the midst of a global pandemic. In an article for Guardian New Zealand, Elle Hunt suggested that these policies are a failure of empathy. “Discriminating against all but the most wealthy members of the diaspora is a rare failure of not just compassion but imagination – to reach a more equal solution, and to imagine the painful personal circumstances in which it might be warranted.”

Empathy asks different things of a government than fairness. It asks for mercy and the maximum provision of services to those who are suffering. It asks for an imaginative capaciousness about what life is like for citizens whose jobs, families, friends and visas would have been in peril if they had returned earlier. It asks for magnanimity, forgiveness, and generosity.

Empathy may not be a viable long term guiding principle for a political party. But in a pandemic, we may find that the alternative language of fairness and moralising either loses its footing entirely or forces us to absurd conclusions.

“Only fair” was how the Premier described the policy, but we have more values than only fairness. A global emergency may be the time to use some.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The erosion of public trust

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 6 AUG 2020

As Melbourne goes into the most intense lockdown measures we’ve seen during the Covid-19 pandemic, activity in the state grinds to a halt.

In media outlets around the country, contrarian commentators are running pell-mell to explain why the lockdowns are the wrong move, and why we should be hastening to open the economy, even if it means paying a price in lives.

Others have been sprinting at a similar speed to disprove them – perhaps moving too fast, and in so doing so, having the argument on their terms.

Consider two of the loudest critics of the purpose of the lockdown: UNSW Economics professor Gigi Forster and Adam Creighton, economics editor at the Australian newspaper. Forster has argued that the costs – measured in terms of overall wellbeing – are more greatly increased by our response to Covid-19 than by the virus itself.

Creighton’s arguments are related, though he has emphasised more the difference between quantity and quality of life. On the lockdowns in Melbourne, he recently tweeted “What’s the point in being alive if you can’t live?

Shameful what’s occurring in Victoria.

Effective dictatorship declared.

Devastating, destructive power of the state on full display.

Respect for the individual clearly irrelevant.

What’s the point in being alive if you can’t live?— Adam Creighton (@Adam_Creighton) August 2, 2020

Perhaps the loudest response to each of them has been to say that a successful economic exit from the COVID-19 pandemic relies on successfully controlling the virus through measures like lockdowns, social distancing and so on. Even on economic terms, it won’t work to allow the virus to run through the community. We can’t come back economically unless we succeed medically. It’s not a zero-sum game.

I’m not the right person to decide whether or not that argument is correct. But that’s not my primary concern either. Instead, my concern is that in arguing the facts on this particular issue – that economically we are better off by controlling the spread of the virus – we have granted them their first principle. Namely, that the correct course of action is whichever one makes the most sense economically and does the most work to maximise quality of life for the largest number of people.

In granting this principle, we’re rushing over a lot of controversial territory. For instance, we might want to take issue with Creighton’s argument on other grounds – that whilst it is important to be able to live fully, in order to so, we need to be alive. The idea that ‘life is for living’ only makes sense if we also say that some people shouldn’t be permitted to stay alive. And many people won’t want to say that.

The point is, the ‘maximise wellbeing’ argument implies a harsh form of utilitarianism. It suggests we accept that there are some people who will have to pay the price for our flourishing.

Maximising benefit still leaves some people to suffer. Usually, it means leaving the same people who have suffered before to suffer again. After all, the most vulnerable already have a low quality of life, so if they end up dying, statistically speaking, it doesn’t show up as much of a loss.

When we encounter arguments like those of Creighton and Forster, we have a choice to make: what matters most to us? Is our primary concern making as many people as possible as well off as we can? Or do we to stand in solidarity with those who are worst off, and refuse to flourish at their expense?

There are schools of thought and philosophers and arguments that will give you cover whichever way you make that choice. But it is a choice to be made. We can’t just interrogate the conclusions of these arguments, we need to question their starting (and often hidden) premises.

During this pandemic we have started to see some of the hidden premises bubble to the surface. Overwhelmingly, the result has been a discomfort at the idea that we get to decide who we are willing to sacrifice for our collective benefit.

I hope that’s an idea that we remember. Because that’s not a problem that started with COVID-19. Instead, it’s a trade-off that is hard–wired into our economic system. In many ways, it’s perfectly logical to suggest we let more people die from Covid-19 if it means we all benefit. After all, it’s what we’ve always done.

We need to recognise that it’s not just people who champion beliefs and values. It’s the very systems that inform and shape our world.

If we don’t want our collective benefit to be paid for by those who most need our care, we need to do more than debate the people floating this idea. We must interrogate the system that gave rise to those views at all. We need to recognise the ways in which it is our default setting and find the courage to imagine another way of doing things.

It’s often said there are no atheists in the foxholes. It feels like there are also few nihilists in a crisis. Circumstances like these sharpen our moral intuitions and surface underlying tensions in society.

Our responsibility, as well as getting through this and getting each other through this, is to ensure that in times of comfort we retain that ethical sharpness and continue to refuse to flourish when that requires others to fail.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Cris Parker The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

Emerging from the turbulence of COVID-19, we have the opportunity to escape the hold of our past and use moral imagination to explore a better future.

After months of living through disruption, old work habits and perceptions may no longer fit the ‘new normal’, says Michael Baur, Associate Professor in the Philosophy Department at Fordham University and an Adjunct Professor at Fordham Law School.

“There’s a very positive side to this, because it makes us realise that the seemingly obvious, natural way of operating is not so obvious anymore.” says Baur.

“It does afford us the ability to think a little bit more carefully about what we’re doing.”

A simple example may be that, after mastering virtual meetings, we realise that the regular face-to-face interstate meetings we thought to be essential are not, in fact, a necessary part of doing business. Instead of asking ‘can we do this online?’ we might now ask, ‘should we do this online, is there a good reason to do it in person?’

“It’s liberating, potentially, to be able to be thrown back and see that the seemingly natural is really not so natural and obvious after all,” says Baur.

Aspects of life previously unquestioned, such as our choices of where to live, send our kids to school or even the jobs we do, may be cast in a different light.

Speaking with Bob McCarthy, an Irish colleague, he spoke of the experience of the ‘Celtic Tigers’ during ten-year-plus period of economic growth prior to 2008. “Ireland had never experienced anything like it and our economy became the envy of the world. Of course, we lived in accordance with our new wealth and fame – two houses each, BMWs, ski holidays and buying chalets in Morzine”, says McCarthy.

Many rationalised their good fortune – ‘we’ve had it tough for so long we deserve a little luxury.’ So, when the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) crash came, it came hard. There was a 60% average fall in property prices, high unemployment, many family tragedies, house repossessions and years of debt to repay.

Bob said that the experience of crisis changed attitudes and behaviours, “Now, those of us who have been through this look at life, business, money, relationships, values, ethics through a different filter than before”.

He describes the experience of having benefitted from the pain. What had once seemed important during the times of excess are no longer important. What didn’t matter then, matters to him now. “Don’t get me wrong – not everything has changed. But for most the filter we use has changed”.

Baur says that, with the experience of COVID-19, we now have a similar opportunity to reset our aspirations, “When we were riding easy, just several weeks ago, we were in a state of deception.” He recognises that the pandemic has caused major economic shocks – perhaps even more severe than those caused by the GFC, “And now we can regroup. That seems to me a more positive, healthy way of thinking of it – that all of this wealth and expectation was not really ours to have to begin with.”

Bigger is not always better

The aftermath of the pandemic presents a good time to reassess our attitude to growth. The fact that almost all sectors of business have suffered means that there is a collective opportunity to slow down and reassess whether the purpose of business is to make more money for money’s sake, or to provide for human need.

Business is now attending to issues that were always there to be addressed – but remained largely ‘unseen’. By presenting itself as a ‘common enemy’, COVID-19 has caused us all to look up at the same time and respond to a suite of collective problems.

In many cases, our response has been an expression of human goodness, compassion and altruism. ‘Them’ has become ‘us’.

For example, Accor hotels, is opening up unused accommodation to support vulnerable people. Simon McGrath, Accor’s CEO, says, “Our doors are open,” said Accor’s McGrath “We have accommodation assets that can help people in times of need, and while the industry’s been devastated commercially, it doesn’t mean we can’t help.”

In a similar vein, UBER has partnered with the Women’s Services Network to provide 3,000 free rides to support those needing safe travel to or from shelters and domestic violence support services.

Australia was relatively unscathed by the GFC of 2008 and did not experience the large economic downturn felt elsewhere on the globe. Australia has also managed to flatten the curve and “none have been more successful than Australia and New Zealand at containing the coronavirus,” said Jonathan Rothwell, Gallup’s principal economist.

This is thanks to our strong public health system and our comprehensive testing regime, to the tracing of carriers and our strict self-isolation and physical distancing laws. We were also lucky that our geographic isolation bought us an extra 10 precious days to prepare.

However, Australia has not and will not escape the economic consequences of the pandemic – and our response to the threat it poses. So, how will we shape up when the challenge is an economic recession as opposed to a medical emergency? Will the good will and sense of common endeavour persist during the next phase of struggle? More interestingly still, will the sense of mutual obligation survive a return to posterity? Or will we resume our ‘old ways’?

Baur says an argument could be made that business and society in general did not make the most of the lessons to be learned from the GFC, more than a decade ago. Ireland’s Bob McCarthy, is of the same opinion, “We may be having an opportunity that would have been a lost opportunity from that time,” he says.

“What might be seen as a loss of opportunity, a loss of growth, in one limited respect, is really a darn good thing for everybody,” Baur says.

Echoing the same sentiment, Mike Bennetts CEO of Z Energy in New Zealand told audiences at the Trans – Tasman Business Circle that this virus has accelerated us into the future by 5 years, so “let’s make the most of it”. Our instinct is to seek comfort and confidence in the known which will mean going back to the way it was.

The challenge, now, is not only to create a new future but a better future. For that to happen we need to unleash a better version of ourselves.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Leading ethically in a crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Perils of an unforgiving workplace

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

FODI launches free interactive digital series

FODI launches free interactive digital series

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 1 MAY 2020

FODI Digital, announced today, is an exciting series of free, online conversations to be live-streamed on May 9 and 10.

The line-up will feature a selection of the international and Australian speakers originally slated for the live festival that was cancelled, by government order, as the COVID-19 lockdown came into effect last month.

“The theme for 2020’s live festival was Dangerous Realities and we seem to well and truly have encountered one. Critical thinking is essential, especially as we isolate further from our communities, families and global neighbours.” said Festival Director, Danielle Harvey.

Executive Director of The Ethics Centre and Co-Founder of FODI Simon Longstaff says FODI digital is a timely invitation to think critically.

“We may submit to a lockdown of our bodies, but never our minds. If ever there was a time to test the boundaries of our thinking … it is today!”

The series of online conversations takes inspiration from the original FODI 2020 theme of ‘Dangerous Realities’, with online sessions being streamed via the festival website. The series will interrogate the reality of the current pandemic and its wider implications for our world and society.

Audiences can contribute questions live while the discussions take place.

For Festival Director Danielle Harvey, there’s never been a more important time for these critical conversations. “Decisions are being made at every level that will shape how we live our lives both now and in the future.

“While we can’t present the program in the way originally planned, these digital conversations will address topics that really need to be put under the microscope. COVID-19 will hopefully end at some point, and understanding what kind of world we will then be entering is essential.”

Sessions include:

- The Truth About China – Former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd is joined by journalists Peter Hartcher and Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, with Human Rights Watch researcher Yaqiu Wang, and strategist Jason Yat-Sen Li, in a wide-ranging discussion about China;

- The Future Is History – Russian-American journalist, high-profile LGBTQI activist and outspoken critic of Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, Masha Gessen, shares her thoughts on Russia and the coming US elections;

- Snap Back To Reality – Philosopher Simon Longstaff leads a discussion with social researcher Rebecca Huntley, political journalist Stan Grant, and fellow philosopher Tim Soutphommasane, on the social shifts, policy and economic consequences that await us in a post-COVID-19 world;

- States of Surveillance – Futurist Mark Pesce, 3A Institute data expert Ellen Broad, and founder of Old Ways, New Angie Abdilla discuss the issue of digital surveillance for virus tracking and the potential threat posed by the ‘normalisation’ of government surveillance;

- Misinformation Is Infectious – First Draft’s Claire Wardle, tech journalist Ariel Bogle discuss COVID-19-related conspiracy theories and what they tell us about technology’s role in the spread of damaging misinformation;

- Stolen Inheritance – Australian youth leaders, Daisy Jeffrey, Audrey Mason-Hyde and Dylan Storer discuss their concerns for the world they will inherit: a world of debt, educational disadvantage, diminished job opportunities, climate catastrophe and … future pandemics;

- The Ethics of the Pandemic – Philosophers Matt Beard, Eleanor Gordon-Smith and Bryan Mukandi take a step back from the day-to-day dilemmas of the pandemic to try to understand what’s really going on, the lessons we learn and the hidden costs of the choices we make;

- Political Correct-Mess – Conservative Australian commentator Kevin Donnelly, journalist Chris Kenny, and journalist Osman Faruqi join journalist Sarah Dingle to dissect political correctness and ask, “Has it gone too far?”;

- Ageing is a Disease – Biologist David Sinclair talks about cracking and reversing the ageing process, which may help the elderly in their fight against a range of diseases and viruses.

The event will live stream straight from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas website across May 9-10. Visit www.festivalofdangerousideas.com to view the program.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

WATCH

Relationships

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Cris Parker The Ethics Centre 24 APR 2020

A senior executive starts making out-of-character decisions that reflect his personal fears. Teams are frozen in indecision as the ground continually shifts beneath them. Days become punctuated with emotional meltdowns from people you have always relied upon in a crisis.

At home, you might be disagreeing with loved ones about the right response to COVID -19. Is the situation as serious as officials claim? Or are people exaggerating the risks? What is the right amount of physical distancing? Why should the whole of a society bear the costs for the sake of the few? Is this even a fair way to frame the questions?

These are some of the signs that the prolonged impact of COVID-19 is causing moral fatigue in the people around you.

Moral fatigue can occur when the “right thing to do” is unclear. Who should bear the cost of protecting a business? What if personally caring for elderly parents risks exposing them to deadly infection? It can be exhausting to make decisions in this kind of ambiguity, day after day.

Michael Baur, Associate Professor in the Philosophy Department at Fordham University and an Adjunct Professor at Fordham Law School, says moral fatigue comes from situations where attempts to do good also result in “destroying a good”.

“People have often referred to the idea of moral fatigue as compassion fatigue or moral distress,” he told me on a zoom call from the US. “What we have in the current context is a situation that makes it increasingly difficult to understand if I’m doing the right thing. It’s no longer possible to assume that the good that I’m doing is unambiguously good,” he says.

It could be dangerous to keep running a business, for instance, if it means employees are in danger. “There’s a real conflict there. And there are no rules.”

Why people panic

Usually, as people go about their normal lives many actions are performed on “autopilot”. Typing on a keyboard, for instance, is done out of habit; the decision of which keys to hit doesn’t exercise mental exertion; one’s finger ‘do the work’. Baur says a crisis such as COVID-19 “jumbles” the keys on the keyboard. It changes the rules and worse still, you don’t know what those new rules are as they can change, minute-by-minute.

“It’s really disorienting,” says Baur. “People go back to what they know is safe, and they become more infantile, more self-protective and defensive.”

This is the kind of response that decreases our capacity to make good decisions. It leads to the hoarding behaviours we have seen in supermarkets, anxiety about money and a focus on individual survival.

Slow down and be more forgiving

Thinking about ‘just getting beyond this’ assumes a future state where the problem no longer exists and everything is the same as before. It’s too simplistic to suggest we will all be ok – many of us won’t be, unless we adapt.

A common result of moral fatigue can be impatience. When we try to think through frameworks that no longer serve us well we can become increasingly impatient, the more we do so, the more mistakes we make – leading to even more frustration.

Baur likens our situation to building the raft at the same time that you are using it to survive. He says, it’s okay to make mistakes because we’re all trying to refashion this raft, even as we’re stepping on top of each other trying to stay afloat. Mistakes will be made.

“You’re not alone. Everybody feels the same way. We have to be more forgiving of others and I think individuals have to be more forgiving of themselves in the sense that it’s okay to be freaked out. Everybody is.”

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

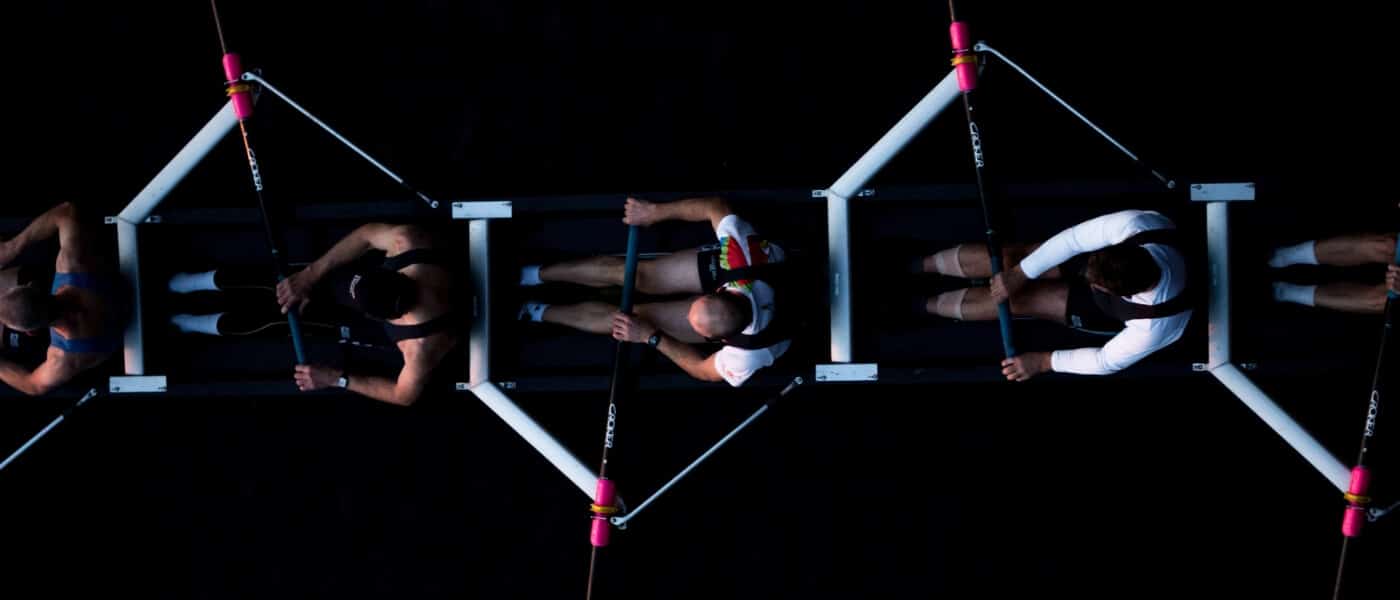

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Health + Wellbeing

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Karina Morgan 16 APR 2020

The coronavirus pandemic has affected nearly everything we do in our everyday lives. The things that give us joy and meaning – going to the gym, the beach, meeting friends for coffee – are no longer possible.

This is having a real impact on our mental health and capacity for good decision making. Beyond Blue have reported a four-fold increase in the number of calls and enquiries related to COVID-19 since March, a level far exceeding the period during the summer fires.

Our brains are wired to seek certainty and our neural circuits register unexpected events as threats. This triggers a fear response, known commonly as ‘fight or flight’, which causes a cascading chemical reaction in our bodies. That response prevents or impairs access to the higher levels of the brain where we deal with complex decisions.

So, it’s fair to say that uncertainty and fear reduce our capacity for quality decision making. This is, in part, because the area of impeded access involves the pre-frontal cortex, the part of our brain that actively processes information, accesses creative thinking and enables good decision making.

At its very core, ethics is about making good decisions. It asks us to consider all the ways we might act and to choose for the best. To take responsibility for our beliefs and our actions, and live a life that is entirely our own.

We know that many of you are facing challenging choices in circumstances that involve an unprecedented level of change and uncertainty in our individual and collective lives.

People are moving to work from home with kids in the house, facing job losses, closing businesses and deciding how to care for vulnerable loved ones. Many people are also experiencing the impacts of hyper-connection and feeling overwhelmed by the constant stream of new information.

With the sense of control and certainty taken from us, it’s easy for our decisions to be overcome by what we fear. With that in mind, it’s important to make time to find new activities that will help to activate the feel-good chemicals in our brains.

These seven activities can be practised while experiencing physical distancing. They are proven to slow down the stress response and boost your mood.

-

Take a nature break

2,500 years ago, Hippocrates, the Ancient Greek Physician and so-called ‘father of medicine’, said “walking is man’s best medicine”. Having invented the Hippocratic oath, he certainly wouldn’t lie! The moment you step outside the concrete jungle and into nature, your body shows its gratitude by releasing serotonin, a mood-regulating neurotransmitter. We are encouraged to stay at home. But if you have a backyard or nature reserve nearby, take regular breaks from the computer for fresh air or to use these spaces for exercise. Just be mindful to ensure you’re following recommendations and maintaining safe physical distancing in the process.

-

Move your body

Physical exercise acts like a power booster, it increases endorphins, the ‘peptide good guys’ that reduce pain perception and trigger positivity. Literally, happy days. Running and walking are great ways to shift pent-up energy. If you’re in self-isolation, try skip rope, something you could make, at a stretch, with a plastic cord or clothes line. A 32 year old French man ran the entire length of a marathon on his balcony during lockdown! Give yourself a tech-tox and move your body, ideally in nature, even if it’s just for ten minutes.

-

Take a bath

Many people experience a sense of calm around water and it’s no surprise if you consider the fact that our bodies are 60% water, and our brains more than 70%. Both Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine believe that the water element is crucial to rebalancing the body. With many beaches closed, look to what you can do within your own home. Fill up the bathtub and immerse your body in water. To super charge the experience you might even soften the lighting or drop in some essential oils to stimulate your senses.

-

Have a laugh

Laughter triggers the release of dopamine into the brain’s reward centre, giving you a high that lowers stress levels and increases your receptivity to pleasure. What may come as a surprise is that research also suggests that simply anticipating a laugh can have a similarly powerful effect. The expectation of something funny turns on our parasympathetic response system. So, it seems there’s never been a better time to practise your best ‘dad jokes’ on friends or the kids. There’s plenty of funny fodder available on streaming services. Check out Vulture’s list of the 50 best comedies on Netflix.

-

Practice yoga

The benefits of this ancient practise go far beyond the physical. In a yoga class, the combination of breath awareness and asana (postures) act to still the fluctuations of the mind and deepen your mind-body connection. Studies have shown that just a single one-hour yoga class can have a positive biochemical impact on your brain. Regular practise can reduce stress, anxiety, post traumatic stress disorder and depression. With traditional classes currently cancelled, many yoga teachers and studios are live streaming offerings, by donation or free of charge, for you to practise from home.

6. Listen to some tunes

Music makes your brain sing. You know that happy rush you get when your favourite song comes on the radio? It’s a chemical romance, one that lets off steam, injects the good vibes and let’s be real, is just a whole lot of fun. When music triggers your pleasure receptors dopamine is released into the striatum, the same part of the brain that responds to sex, chocolate, and is stimulated by artificial narcotics like cocaine. Research has also found that that some music has meditative qualities and can positively impact stress reduction and overall happiness. Fun fact: neuroscientists have found that listening to this song can reduce anxiety by up to 65%.

-

Dance it out

Dancing, like any other physical activity, releases neurotransmitters and endorphins to alleviate stress. Combining the dopamine response stimulated by music with these endorphins has the potential to supercharge your positivity. Plus, it’s almost certain that you’ll laugh along the way. Right now, you really can dance around the house like no one is watching. Prefer company? Have a virtual dance party. Many companies are rolling out video call dance breaks to manage the impacts of social isolation on extroverts in the workforce. Whether you want to do it with work, or friends, it’s easy to set up a time, pick a song, and all jump on a video call to dance it out together.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

LGBT…Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

BY Karina Morgan

Karina is a communications specialist, avid hiker and volunteer primary ethics teacher, with a penchant for the written word.

Moving work online

Moving work online

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Talya Wiseman The Ethics Centre 10 APR 2020

As the COVID-19 dominos continue to fall, many organisations are scrambling to rethink the way they work. These changes are happening in real time; on a scale both unprecedented and unpredicted.

The last pandemic of this nature, the Spanish Flu, occurred 100 years ago – well before anyone had dreamed up the internet, computers and video conferencing. In 2020, advances in technology, such as international flights, have allowed this virus to spread at a much faster rate. However, they have also afforded many organisations the opportunity to pivot their operations online.

Schools and universities have, for the most part, managed this at an incredibly fast pace. With barely any notice, teachers have become adept at using online delivery platforms and are coming up with new ways to engage their students online.

Students are able to continue their same classes via platforms like Zoom or Microsoft Teams; all the while knowing that the rest of their class is right there, learning alongside them.

Now that all but essential workers are urged to stay at home, ideas about working environments have also been forced to alter at an unusually rapid pace. For example, workplaces and teams have begun to adapt to meeting online. A popular meme doing the rounds at the moment depicts a scenario 40 years from now when a grandchild asks their grandparent with wonder “Go to work? You used to actually GO to work?”

It is incredible to see how many fundamental changes and shifts in thinking have occurred in such a short space of time. We simply had neither the time nor the opportunity to incorporate long policy discussions, carefully timed rollout plans or trial periods. Many organisations that previously assumed they needed a common workplace are now questioning the validity of this assumption.

What happens next?

The big question is this: when all of this is over and we return to normal, what will normal look like? Will organisations revert to their old ways? Or will we have seen the value in new patterns of working? Our eyes have been opened through this experience. Our assumptions about the nature of work have been challenged. Having reorientated towards online workplaces, will it be so easy to pivot back? And will we want to?

There are certainly benefits to workplaces accepting remote working as a viable option. Parents and carers, who previously struggled to convince their employers that they could effectively work from home, will likely find this argument much easier to make. If people have been able to fulfill their work duties in these most trying times, clearly it will be easier for them to continue to do so when it is an option they are choosing.

The stigma of working from home has rapidly been removed. It should no longer be seen as the ‘lesser’ option compared to attending an office. Organisations are finding innovative ways to ensure staff feel supported while working from home; while also maintaining expectations of staff – wherever they happen to be located.

The role of the physical workplace

However, there is a risk in realising just how easy it is to do things online. The role that work plays for individuals is much more than just providing an income. Work is also about fulfilment; it is about social interaction. The best initiatives can arise from bouncing ideas around with colleagues. Families can laugh together at the dinner table when sharing work stories and funny moments that occurred at the office. Colleagues can celebrate each other’s success and commiserate together when things don’t go as planned. Work is about so much more than ‘work.’

One of our principles, here at The Ethics Centre, is to “know your world and know yourself”. We believe in the importance of questioning who we are and being conscious of what we do. If the nature of work is fundamentally to change, we must recognise what we are giving up, as well as the opportunities that may arise. Just because we were rushed into this new reality doesn’t mean we can’t carefully consider the best way to move on from it.

Let’s not just fall back into old patterns. Let’s use this as an opportunity for questioning and for finding a better ‘normal’. That might well be a workplace that embraces flexible arrangements and is open to non-traditional office environments, while at the same time never losing touch with deeply human moments and interactions.

Perhaps we will realise that work, regardless of industry, is about purpose, fulfilment and human interaction.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

BY Talya Wiseman

is an experienced educator who has worked extensively in both the formal and experiential education space. At The Ethics Centre, Talya is the Educational Program Manager creating innovative, engaging and quality ethics-focused education

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Dennis Gentilin 9 APR 2020

Crises, especially as momentous as this one, have a habit of exposing leaders. At worst, they expose incompetence and self-interest. At best, they reveal courage, resilience and deep concern for others. It is the latter that is the hallmark of ethical leadership.

Make no mistake, these are challenging times. There are potentially some dark days ahead. Humanity has not faced a perilous situation of this magnitude in my lifetime.

Unfortunately, ethical leadership is not something that can be ‘switched’ on at will. In trying times, one cannot simply dust off the ethical leadership manual and, like a chameleon, transform one’s approach. The reason for this is that ethical leadership is honed through many years of practice.

Ethics is a long game

This is not a new idea. Aristotle described ethical virtue as a “hexis” – a state or disposition – that is shaped by our habits. We come to be ethical by acting ethically, consistently being guided by an ethical framework when making choices, regardless of how difficult this might be given the prevailing circumstances. This is what it means to be a person with integrity.

For this reason the COVID-19 pandemic will (and in some cases already has) reveal what leaders believe to be good (their values) and right (their principles). More importantly, it will reveal how committed they are to their ethical core. Those who have failed to make ethical practice a daily habit will find it difficult. They may already have stumbled or are perhaps struggling to win the trust of sceptical followers. For those who have made integrity central to their leadership, the turbulent waters will be somewhat easier to navigate. Making the ethical choice will come more instinctively.

There is also the possibility that ethical leadership will emerge in the current crisis from the most unlikely of places. People whom we may have thought were not cut out to deal with a crisis or a thrust into a position of leadership will rise to the occasion. Perversely, moments like these, instead of paralysing leaders, can provide greater clarity on what is the ‘right’ thing to do. The path one must take, although rocky, lights up and is clearly signed. A leader comes into their own.

Ethical leadership, not perfection

All this being said, one thing that we should not (and cannot) expect is ethical perfection. In situations like these where there are excruciating trade-offs associated with many decisions, ethical perfection cannot be defined. The available choices are evenly balanced, providing a myriad of possible outcomes that all have considerable merit. It would therefore be preposterous to think that any leader in these circumstances, no matter how ethical, will get everything ‘right’. We should respect those who are being called upon to make extraordinarily difficult decisions, with imperfect information, in a highly dynamic environment.

However, there are some minimal expectations we should expect from our leaders. We should expect a degree of candour and honesty, accepting that in some cases full transparency will do more harm than good. We should expect that the safety of people – particularly the most vulnerable – is prioritised, accepting that there will be unfortunate loss of life. Above all, we should expect leaders to act with sincerity, rely on the best available evidence and display ethical competence. ‘Winging it’, ‘intuition’ and ‘common sense’ are not enough.

We all have a role to play

We should also understand that ethical leadership is not reserved for those who sit highest in the hierarchy, especially in unprecedented moments like these. This is something that can’t be underestimated. Ethical leadership will need to emerge at every level of society if we are to find a way through what will be some very difficult weeks and months ahead. Do not discount our essential role as ethical citizens.

Jon Haidt, a professor of ethical leadership at the Stern School of Business at NYU, talks about how morality “blinds and binds”. It can evoke the passions and bind people around a common cause. However, in doing so, it can breed dogmatism and drive us into our ideological camps, blinding us to our common humanity.

For the first time in a while, the coronavirus has created a present and common cause that all of humanity can bind to. It will test our leaders and in doing so reveal those who make ethics more than a word in their by-line. It will produce benevolent and heroic acts among citizens that extreme circumstances like these so often educe. And hopefully, by producing a cause we can all be bound by, it will dampen some of the tribalism and self-interest that has been an unfortunate feature of some sectors of our society in recent times.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

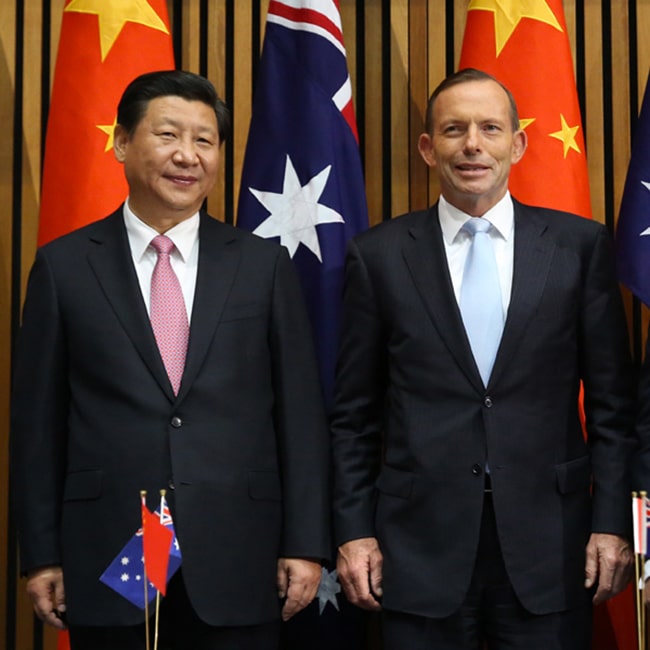

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Society + Culture

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Gen Z and eco-existentialism: A cigarette at the end of the world

BY Dennis Gentilin

Dennis Gentilin is an Adjunct Fellow at Macquarie University and currently works in Deloitte’s Risk Advisory practice.

Is it ok to visit someone in need during COVID-19?

Is it ok to visit someone in need during COVID-19?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 9 APR 2020

You’ve been hitting us up with your COVID-19 ethical questions. We’ve been sending our ethicists into the philosophy lab to cook up some answers.

This week, we’re talking about trade-offs. How do we the balance risks and potential harms from our behaviours against the value they might have?

I have family members who are at high-risk from COVID-19 but who are also at risk of mental stress from isolation, what should I prioritise – their physical safety or their psychological wellbeing?

When I was teaching medical students (about ethics, nobody wants me teaching them science), I was often relieved to find an openness to considering the holistic needs of the patient. They weren’t interested in healing the body at the expense of the mind. This was thanks in part to something called the ‘biopsychosocial model of health’, which basically suggests that we need to think of health at the intersection of the physical body, the mind and the environment we find ourselves in.

What this model reminds us of is that we don’t make trades between mental and physical health – those terms are somewhat of a misnomer. There aren’t different kinds of health; there’s just health. Someone who is suffering from a virus isn’t enjoying a healthy life; nor is someone whose depression is worsening as a result of isolation.

Think about it this way: if your family members were diabetic and needed to go to the pharmacy to fill their insulin prescription, you wouldn’t advise them not to go because they were high risk of COVID-19; because that’s not the only thing that’s going to set back their health. I’m not convinced you should think about their health any differently because the problem is mental rather than physical.

That said, it’s important to bear in mind that you should still do what you can to minimise the risk to your family members – not least because they may not be the only ones who are at increased risk of infection if you choose to visit. Again, think of the diabetes analogy. It would be unreasonable to tell them not to go to the pharmacy for fear of COVID-19, but it would be safer if someone who wasn’t high risk collected their prescription on their behalf.

By the same logic, if there are ways you can alleviate their sense of loneliness and isolation without increasing their risk, then you should do those things. You might not have to choose between minimising the risk of infection and helping a lonely family member at a time when loneliness is rife. But if you can’t, it’s helpful to remember that you’re dealing with risky options either way.

I’m struggling to decide whether I should visit my two loved ones in their aged care facilities right now. Do I leave them and trust they will get the correct care if the outbreak spreads or ‘check in’ and visit them?

Ever heard the story of the two wolves? It’s an old proverb. A Native American elder explains to a young man that there are two wolves inside us all. One represents the lesser demons of our nature, and the other the better angels. The wolves are in constant battle with one another to determine the kind of person we’ll be. ‘Which wolf wins?’, asks the young man. The elder responds, ‘the one you feed.’

In times of enormous stress and uncertainty, the two wolves duking it out inside us tend to be our attitudes toward control. One wolf screams ‘Jesus take the wheel!’ and surrenders all sense of agency – throwing in the towel and hoping for the best, taking no responsibility for the future. The other wolf cries, ‘let me drive!’ and tries to manage every possible variable to secure a half-decent outcome. And, just like the story goes, the wolf we feed – the one we reinforce through behaviour and habit – is the one that will win out.

The reason I share the story of the wolves with you is because your concern for loved ones doesn’t seem to be primarily about giving them social connection or making sure they’re not lonely. Rather, your question suggests what’s bothering you most is whether the carers will do a good job without you to check in. That kind of distrust is likely the product of one of two things: reason or anxiety.

Do you have reasons why you suspect the care for your loved ones will languish in your absence? If so, I can only imagine how heart-wrenching it must be to stay away at a time like this. However, if you’ve generally had good experiences and haven’t had any reason to distrust the staff until now, it’s worth reflecting on whether your inner micro-managerial wolf needs some time off to meditate.

I mean that sincerely – most of us need to meditate during this pandemic – to get clarity on how we manage uncertainty. Do we have trouble accepting our lack of control? Are we too lackadaisical or passive when shit hits the fan?

The truth is, I can’t answer the question of whether you should check in on your family – and in doing so expose them and everyone else at those aged care facilities – because I don’t know if you’ve got good reasons for concern. But let me plead with you on behalf of every person who has loved ones in aged care: if you’re doing this because you’re anxious and scared, please stay at home. We’re all scared for our loved ones, but hopefully you can see that resolving that fear by exposing the people you love to risk is as pointless as howling at the moon.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Michelle Bloom The Ethics Centre 6 APR 2020

COVID-19 has created a cascade of unprecedented changes to how we work, live and interact.

With many organisations moving online, managing restructures, significant job loss and transformation of existing roles and responsibilities, leaders need to be consciously aware of the impact of stress on individual and team performance.

Certain aspects of organisational behaviour can trigger threat reactions in people that impede their effectiveness and limit their ability to contribute to the success of the team. Research in neuroscience can inform our response to such situations, as the neural functioning of individuals within the workplace underlies the social nature of high performance.

What happens to us in stressful environments

The brain is a social organ. Studies by UCLA have found that when we feel excluded from play or rewards, our brains trigger a response from the same neural regions associated with the distress that comes with physical pain. This neurophysiological link has been explained as evolutionary, a developmental hangover from the dependency of infancy. As UCLA neuroscientist Matthew Liebermann puts it, “To a mammal, being socially connected to caregivers is necessary for survival”.

This neurological response has a number of implications for business and leaders navigating this current crisis – especially in regards to remote working and communicating organisational changes driven by COVID-19.

A person who feels their position and work to be valued, by their leaders, solely as an economic and rational transaction (labour for money) will likely feel betrayed, unrecognised and disengaged.

Research shows that each time a person feels like this, it is physiologically and psychologically analogous to a ‘blow to the head’ and is processed in the brain in the same way as physical pain. Naturally, our conscious selves rationalise the discomfort, but if this situation is chronic and ongoing, it is more likely that employees will begin to desensitise in self-protection. They will effectively push the discomfort away, so as to not feel it consciously. This shutting down of large parts of our response pathways disables us, making high-performance impossible.

Many studies, including Paul MacLean’s infamous “Triune Brain” theory, look at how fear responses negatively impact the quality of mental functioning. In more mild circumstances, the emotional centres associated with the limbic brain will interfere with the circuitry of the logical neo-cortex. In extreme circumstances, our ‘fight, flight, freeze’ response gets triggered, creating a chemical reaction that entirely hijacks the brain’s emotional centre, the amygdala, making logical thinking impossible.

However you conceptualise it, high emotion is disastrous for the adaptive thinking required for complex problems – so critical for ethical decision making.

Physiologically, the threat response ties up glucose and oxygen, as lower areas of the brain, more intimately concerned with survival, take precedence over higher centres. In threat situations, these resources are withheld from working memory, impairing the processing of new information or ideas, and slowing analytic thinking, creativity and problem solving.

Addressing the needs of the individual and the organisation

We’ve all heard that adults are poor learners, fundamentally intractable, or that their natural response to change is resistance. While elements of these statements are true, what is also true is that the adult brain continues to be highly plastic; albeit not as much as children or infants. That means that not only can behaviours change, but that the neural networks that underlie all thought and behaviour are in fact changing every day.

To increase the chances of your business being high-performing, David Rock’s SCARF Model, as outlined in his paper “SCARF: A Brain-Based Model for Collaborating with and Influencing Others,” suggests that leaders should look at how the organisation deals with the following aspects of individual functioning in the collective social system.

1. Certainty

Our brains are wired to crave certainty. This desire is underpinned by neural circuits that register unexpected events as gaps or errors. Because an assumed pattern is no longer functioning as it should, it is registered as a threat.

Think about how you respond when the car in front slams on the brakes. Normally, we can do multiple things at the same time when we drive – hold a conversation, listen to music, monitor what’s going on around us, think about the shopping list – but faced with a potential accident, your working memory is diminished. All other activities and thoughts must cease as you shift full attention to the potential threat ahead.

Some uncertainty can be intriguing and enjoyable; too much leads to panic and bad decisions. For many people right now, the levels of uncertainty – combined with imminent health and employment risks – will be triggering this aspect of the ‘fight or flight’ response. This impedes their capacity to access creative thinking and good decision making.

Of course, certainty is an illusion. However, people need a semblance of certainty in order to perform. Leaders need to build confidence in their people so they, in turn, can trust in individual and collective capability to work through whatever comes. Keeping a clear and regular stream of communication around how decisions are being made increases trust and promotes engagement. Chunking larger problems into shorter time frames also helps people feel more certain.

2. Status

As humans, our relative status within social systems matters. This is the basis for all competition, social hierarchy, and, conversely, much social unrest. Many organisations have processes and practices that threaten people’s status. Hierarchy reinforces a notion of ‘greater than’ and ‘less than’, while performance appraisals and coaching generally place one person in the position of being more knowledgeable, capable and powerful than the other. Unless these interactions are carefully considered and thoughtfully executed, they will feel threatening to an individual’s status.

Actions that enhance status include private, as well as public, recognition. In addition, the quality of interactions from leaders with their people can raise the self-status of those who sit lower in the hierarchy. Therefore, one of the most important (albeit intangible) skills of a leadership team is their capacity to interact with others in a respectful and status-enhancing way.

With staff working digitally, and from home, leaders need to innovate and find new ways to show this recognition. This will make people feel seen and valued for the work they do.

3. Autonomy

When people feel they can execute their own decisions, without interference, their felt stress is lower. In a 1977 study, residents of aged care facilities who had more agency and decision making rights, lived longer and healthier lives. While what they were deciding about was insignificant; their autonomy was critical. In another study, franchise owners principally left corporations citing work-life balance. Once in their own business, they generally worked longer hours, for less money, and nevertheless reported better work-life balance, because they were making their own decisions.

Delegation systems, hierarchy, confusing reporting lines, moribund policy and procedure, and parochial mindsets can all contribute to less agency for individuals in businesses. Often people are not aware that they are not delegating, that they are effectively withholding decision making from others.

Lack of autonomy is also closely linked with the phenomena of people not working ‘at the right level’. When leaders find themselves working at a level of complexity lower than where they should be working, the flow on to the rest of the organisation is usually inevitable.

4. Relationships

Perceived difference is another human threat-trigger. Collaboration, trust and empathy are predicated on perceiving that the ‘other’ is from the same social group as we are. The decision of friend or foe is usually made in milliseconds.

The organisational implications for bringing groups together are profound. Forming new relationships at this time, such as buddy systems or mentor programs, need to be carefully thought through so as to minimise the potential to ‘spook the horses’. The creation of productive strategic relationships requires repetition via multiple, sequential opportunities and reinforcement through the removal of organisational impediments.

5. Fairness

Fairness is a cognitive construct that motivates people so strongly they will persist in situations that are manifestly unfavourable because they value a perceived fairness on the part of an organisation or a cause. Consider how people historically have volunteered to fight in wars that are not their own, such as the Spanish Civil War, and are prepared to die based on apparent fairness.

People not only want to avoid being unfairly discriminated against, they will also often feel uncomfortable if they find themselves being unfairly favoured by a person or a situation.

Organisationally, the implications are similar and connected to that of certainty. People will be much more accepting of decisions and processes, as fair, if they are transparent.

Fairness is also related to status in that people will feel fairly dealt with if they perceive they are respected as a person and employee. These principles are often coded as ‘natural justice’. In some ways, fairness is an amalgam of the previous four areas of concern.

What leaders need to think about

The upshot for leaders is this – when you trigger a threat response in others, you make them less effective. When you make people feel good about themselves, clearly communicate your expectations and give agency through appropriate delegations, people feel a reward response which is intrinsically engaging – something your people want more of.

In situations where threat is felt to be ongoing, people typically experience burnout. This emotional exhaustion is a result of chronic over-stimulation of the fear centres of the brain. Physiologically, high levels of adrenalin and cortisol can only be supported for so long before they start to damage the nervous system.

Where these sorts of threatening social conditions are widespread, ongoing or both, each individual’s sub-optimal reaction is reinforced by the reactions of the people around them, magnifying the pattern. This looks like ‘learned helplessness’, passivity or protective withdrawal. Sometimes it drives an aggressive pattern where individuals seek authoritarian control over whatever small part of their world they feel they can have an effect on.

Practical steps that can be taken during COVID-19

If you’re an organisation transitioning working roles or letting go of staff due to the impacts of COVID closures, ensure you are both transparent and compassionate in your communications.

Be clear and straight forward about how government policy impacts your workers, keep them informed of the decisions being made and communicate the rationale behind them, particularly when they impact others.

When communicating changes, respect for the people affected is crucial. While your decisions have economic drivers, there are very real human costs associated with the outcomes.

Relationships and connection are of heightened importance now. Take care in implementing processes to foster positive relationships between people – whether by virtual catch ups, a mentor support system, or regular virtual check ins by managers with their staff to see how they are coping and adjusting.

Tension will also be high, and any perceived difference may trigger as a threat. Leaders will need to be conscious of how relationships are managed between staff who may be actively competing for scarce resources or roles, if facing redundancies.

None of these strategies ameliorates the situation

It is the responsibility of the leaders of the transformation to monitor if what is going on in their organisation is supporting or undermining people’s performance. If performance is being undermined, it is their responsibility to raise those instances to awareness of their peers in the leadership team, to mobilise and support staff to break the prevailing patterns and to experiment with alternative approaches.

Navigating the changes ahead won’t be easy, and for many this may be the hardest professional challenge they’ve had to face given the stakes have never been so high. But careful attention to how decisions are made and communicated is critical to staff safety and wellbeing in the current climate. And that’s never been more important.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pavan Sukhdev on markets of the future

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

READ

Business + Leadership

Meet James Shipton, our new Fellow uncovering the ethics of regulation

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights