Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 15 JAN 2026

The sequence of events that led to the cancellation of Adelaide Writers Week revolve around two central questions. First, what, if any, should be the limits of free speech? Second, what, if anything, should disqualify a person from being heard? In the aftermath of the Bondi Terror Attack, the urgency in answering these questions has seen the Commonwealth Parliament recalled specifically to debate proposed legislation that will, amongst other things, redefine how the law answers such questions.

Beyond the law, what does ethics have to say about such fundamental matters in which freedom, justice and security are in obvious tension?

I have consistently argued for the following position. First, there should be a rebuttable presumption in favour of free speech. That is, our ‘default’ position is that there should be as much free speech as possible. However, I have always set two ‘boundary conditions’. First, there should be a strict prohibition against speech that calls into question or denies the intrinsic dignity and humanity of another person. Anything that implies that one person is not as fully human as another would be proscribed. This is because every human rights abuse – up to and especially including genocide – begins with the denial of the target’s humanity. It is this denial that makes it possible for people to do to others what would otherwise be inconceivable. Second, I would prohibit speech that incites violence against an individual or group.

As will be obvious, these are fairly minimal restrictions. They still leave room for people to cause offense, to harangue, to stoke prejudice, to make people feel unsafe, and so on. That is why I have come to the view that something more is needed. In the past, I have struggled to find a principle that would allow for the degree of free speech that is needed to preserve a vibrant, liberal democracy while, at the same time, limiting the harm done by those who seek to wound individuals, groups or the whole of society by means of what they say.

In particular, how do you respond to someone who foments hatred of others – but falls just short of denying their humanity?

It recently occurred to me that the principle I have been looking for can be found in the most unlikely of places: the football field. I was never any good at sport and was always the obvious ‘weak link’ in any team. So, I took a particular interest in the maxim that one should “play the ball and not the person”. Of course, the idea is not exclusively one for sport. Philosophy has long decried the validity of the ad hominem argument – where you attack the person advancing an argument rather than tackle the idea itself. Christianity teaches one to ‘loathe the sin and love the sinner’. In any case, whether one takes the idea from the football field or the list of logical fallacies or from a religion, the idea is pretty easy to ‘get’. In essence: feel free to discuss what is being done – condemn the conduct if you think this justified. However, with one possible exception, do not attack those whom you believe to be responsible.

The one possible exception relates to those in positions of power – where a decent dose of satire is never wasted. That said, the powerful can make bad decisions without being bad people – and calling their integrity into question is often cruel and unjustified. Beyond this, if powerful people preside over wrongdoing, then let the courts and tribunals hold them to account.

The ‘play the ball’ principle commends itself as a practical tool for distinguishing between what should and should not be said in a society that is trying to balance a commitment to free speech with a commitment to avoid causing harm to others. It is especially important that this curbs the tendency of ‘bad faith’ actors (especially those with power) to cultivate an association between certain ideas and certain people. For example, we see this when someone who merely questions a political, religious or cultural practice is labelled as a ‘bigot’ (or worse).

In practice, we will now explicitly apply the ‘play the ball’ principle when curating of the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) – adding it to the matrix of issues we take into account when developing and presenting the program. FODI seeks to create spaces where it is ‘safe to’ encounter challenging ideas. For example, it should be possible to discuss events such as: the civic rebellion and repression in Iran, the Russian war with Ukraine, Israel’s response to Hamas’ terror attack, and so on … without attacking Iranians, Shia, Russians, Ukrainians, Israelis or Palestinians. Indeed, I think most Australians want to be able to discuss the issues – no matter how challenging – knowing that they will not be targeted, shunned or condemned for doing so.

I recognise that there are a couple of weaknesses in what I have outlined above. First, I know that some people identify so closely with an idea that they feel personally attacked even by the most sincerely directed question or comment.

Yet, in my opinion, a measure of discomfort should not be enough to silence the question. We all need to be mature enough to distinguish between challenges to our beliefs and threats to our identity.

Second, while the prohibition against the incitement of violence is clear, the other two I have proposed are much more ambiguous. As such, they might be difficult to codify in law.

Even so, these are principles that I think can be applied in practice – especially if we are all willing to think before we speak. A civil society depends on it.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture

Read me once, shame on you: 10 books, films and podcasts about shame

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

The Bondi massacre: A national response

The Bondi massacre: A national response

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 2 JAN 2026

What is the best response to the massacre of Jewish people at Bondi Beach? I ask that question knowing that the best response may not be the most popular.

For example, the debate about whether or not there should be a Federal Royal Commission has made it abundantly clear that people can reasonably and sincerely disagree about what should be done. The same debate has also revealed that some people have deliberately (and others inadvertently) politicised what should be a matter of broad national consensus – with the ideal response being of a kind that meets a number of core criteria. If ever there was a time to set politics aside in favour of a singular compassion for the Jewish Community and a high regard for the national (rather than partisan) interest, then this was it.

Although united in grief and anger, the Jewish Community is not of a single mind about what should now be done. Differences of opinion are to be expected. It is wrong to expect any group of people to hold a common position simply because they share aspects of identity. Furthermore, while the Jewish Community was the explicit target of the terrorists’ attack – and bore the brunt of the carnage – they are not the only Australians to have been wounded by the murderous rampage that took place on the first night of Hanukkah. The whole nation has been scarred … and now a host of other communities are left to ask, “What caused this to happen? What can be done to prevent this in the future? Who’s next?”.

Bearing all of this in mind, I have come to the conclusion that the best possible response cannot lie in a single measure. Instead, I think the whole nation will be best served by a multi-layered approach. Importantly, such an approach would see the Commonwealth Government go well beyond where it currently stands – but in a direction that, I propose, eclipses what has been called for so far.

Each element of our national response needs to be ‘fit-for-purpose’; tailored to meet a specific need. So, what are those needs? First, the Jewish Community needs answers about what caused the Bondi Massacre – and how it might have been prevented. Second, the nation needs to know if there is anything more that could have been done by our national intelligence and security services to identify and therefore prevent the terrorists from acting. Third, we all need to understand the genesis of hate-crimes (of which antisemitism is an especially virulent, but not the only, form) in Australia – and how this might be combatted in favour of resilient bonds of social cohesion that would enable us to maintain a vibrant, multicultural society in which every person can flourish, free from fear or prejudice.

The first need will be met by the proposed NSW Royal Commission that enjoys the unfettered support of the Commonwealth Government and its departments and agencies. That support needs to be offered with the whole-hearted endorsement of the Prime Minister and unwavering direction from his Cabinet. The Commonwealth should offer binding undertakings to hold to account any of its officers, including members of past and present Commonwealth governments, who are found by the Royal Commission to have contributed to the events in Bondi – either by act or omission. Under these conditions, the proposed NSW Royal Commission will be in a position to address all of the issues arising out of the specific terrorist attack of 14 December.

The second need will be met by the Richardson Review. It will be focused and completed within a relatively short period of time. Anyone who knows or who has worked with Dennis Richardson AC knows that the inquiry will be thorough and exacting. The general public may not see all that he finds and recommends – as national-security considerations will take priority for the sake of us all. However, we can trust that nothing will be overlooked.

The third need can be answered by a National Commission of Inquiry. Unlike a Royal Commission that has a defined legal form – and often seeks to find fault and punish wrongdoers – this Commission would be required to look at the deeper causes of which the Bondi Massacre is a treacherous and violent eruption. Those causes affect multiple communities – indeed, they are a cancer eating away at the soul of Australia. The Commission should have broad powers – but it should especially be enabled to convene individuals and groups from across the nation – to hear the stories of what is happening, the impact of hatred and what can be done to prevent this from metastasising into violence.

In my opinion, we should also put the lens on multiculturalism so that rather than merely celebrating the worthy characteristics of separate communities, we learn how to strengthen the bonds between them – and commit to doing so in practice.

I know that there will be some people in the community, especially the Jewish Community, who would prefer to see the Prime Minister establish a Royal Commission to investigate the scourge of antisemitism. There is something distinctive about the hatred directed at Jews – almost unfathomable given its dark persistence over millennia. However, what I have in mind would allow the Jewish experience to be given full voice – but in conditions where we see how it relates to the experience of others in the community. In itself, that will help forge common bonds – as always happens when we see ourselves reflected in the lives of others. Given the searing nature of events, a proposed Commission should prioritise its examination of antisemitism, before all else, reporting on this within twelve months of being established.

In putting forward this proposal, I sincerely believe that nothing will be lost – and much will be gained. I hope that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese might establish a Commission that embraces the whole nation – in all of its marvellous diversity – in order to find light at this terrible moment of darkness.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Life and Debt

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The problem with Australian identity

A message from Dr Simon Longstaff AO on the Bondi attack

A message from Dr Simon Longstaff AO on the Bondi attack

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 15 DEC 2025

On behalf of everyone who works at The Ethics Centre – our board, staff and volunteers – I am writing to all of our members and supporters to offer our heartfelt sympathy to those affected by the terrorist attack that took place, in Bondi, last night.

Some might observe that this is not the biggest atrocity to have taken place in the world this year. However, I do not believe that atrocities should be ranked according to the numbers of people killed and maimed. What defines such events, as evil, lies in the perpetrator’s intent to harm people; not because of what they have done, or what they believe – but simply because of who they are.

Last night was not an indiscriminate act of terror. People were targeted merely for being Jewish – men, women, children … people of every type and description. Whether you lived or died had nothing to do with one’s politics or opinions about the world. Simply being Jewish – indeed, simply being in the midst of the Jewish community – was enough for you to be targeted. This was antisemitism in its most violent form.

As I write this note, we still do not know what motivated the terrorists. However, nothing can make good what they did – cold-blooded murder can never be justified … no matter who does the killing, no matter who is the victim, no matter how many reasons are advanced.

Now, I fear that the cycle will take another turn for the worse. Members of other communities will fear that they will be tarred with the same brush as the terrorists – no matter what they have done, no matter what they believe – but simply because of who they are.

Surely, surely it is time to stop this vicious wheel from turning.

At The Ethics Centre, we believe in the intrinsic dignity of all persons – without exception. This recognition has no boundaries and, difficult as it may be, must extend even to those who visit terror upon us. At times like this, we should embrace our common humanity – and not give way to those who would stoke and exploit divisions for their own ends.

Many people will be hurting today – even if far removed from the carnage. Many will be angry or confused, or feeling helpless or just numb. I think I have felt all of those emotions since the tragic events of last evening began to unfold. However, in the midst of all of this, we can hold onto the fact that what happens next is not inevitable.

Our governments will take the lead in providing security – but only we, the people, can create the conditions of ‘belonging’ in which every person can feel safe in the warm embrace of a society that recognises the intrinsic dignity of all. In this, let’s not forget the bravery of those who confronted the gunmen, who rendered first aid, who comforted the dying or offered sanctuary within their homes. These people show what is possible when the good in us comes forth.

Making and sustaining just such a society – even in the face of terror – is what each of us can do. I hold onto that – and in the midst of pain and confusion hope you might do the same.

Image: Paul Lovelace / Alamy

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

LISTEN

Society + Culture

Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI)

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ask an ethicist: Am I falling behind in life “milestones”?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

AI and rediscovering our humanity

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 2 SEP 2025

With each passing day, advances in artificial intelligence (AI) bring us closer to a world of general automation.

In many cases, this will be the realisation of utopian dreams that stretch back millennia – imagined worlds, like the Garden of Eden, in which all of humanity’s needs are provided for without reliance on the ‘sweat of our brows’. Indeed, it was with the explicit hope that humans would recover our dominion over nature that, in 1620, Sir Francis Bacon published his Novum Organum. It was here that Bacon laid the foundations for modern science – the fountainhead of AI, robotics and a stack of related technologies that are set to revolutionise the way we live.

It is easy to underestimate the impact that AI will have on the way people will work and live in societies able to afford its services. Since the Industrial Revolution, there has been a tendency to make humans accommodate the demands of industry. In many cases, this has led to people being treated as just another ‘resource’ to be deployed in service of profitable enterprise – often regarded as little more than ‘cogs in the machine’. In turn, this has prompted an affirmation of the ‘dignity of labour’, the rise of Labor unions and with the extension of the voting franchise in liberal democracies, to legislation regulating working hours, standards of safety, etc. Even so, in an economy that relies on humans to provide the majority of labour required to drive a productive economy, too much work still exposes people to dirt, danger and mind-numbing drudgery.

We should celebrate the reassignment of such work to machines that cannot ‘suffer’ as we do. However, the economic drivers behind the widescale adoption of AI will not stop at alleviating human suffering arising out of burdensome employment. The pressing need for greater efficiency and effectiveness will also lead to a wholesale displacement of people from any task that can be done better by an expert system. Many of those tasks have been well-remunerated, ‘white collar’ jobs in professions and industries like banking, insurance, and so on. So, the change to come will probably have an even larger effect on the middle class rather than working class people. And that will be a very significant challenge to liberal democracies around the world.

Change to the extent I foresee, does not need to be a source of disquiet. With effective planning and broad community engagement, it should be possible to use increasingly powerful technologies in a constructive manner that is for the common good. However, to achieve this, I think we will need to rediscover what is unique about the human condition. That is, what is it that cannot be done by a machine – no matter how sophisticated? It is beyond the scope of this article to offer a comprehensive answer to this question. However, I can offer a starting point by way of an example.

As things stand today, AI can diagnose the presence of some cancers with a speed and effectiveness that exceeds anything that can be done by a human doctor. In fact, radiologists, pathologists, etc are amongst the earliest of those who will be made redundant by the application of expert systems. However, what AI cannot do replace a human when it comes to conveying to a patient news of an illness. This is because the consoling touch of a doctor has a special meaning due to the doctor knowing what it means to be mortal. A machine might be able to offer a convincing simulation of such understanding – but it cannot really know. That is because the machine inhabits a digital world whereas we humans are wholly analogue. No matter how close a digital approximation of the analogue might be, it is never complete. So, one obvious place where humans might retain their edge is in the area of personal care – where the performance of even an apparently routine function might take on special meaning precisely because another human has chosen to care. Something as simple as a touch, a smile, or the willingness to listen could be transformative.

Moving from the profound to the apparently trivial, more generally one can imagine a growing preference for things that bear the mark of their human maker. For example, such preferences are revealed in purchases of goods made by artisanal brewers, bakers, etc. Even the humble potato has been affected by this trend – as evidenced by the rise of the ‘hand-cut chip’.

In order to ‘unlock’ latent human potential, we may need to make a much sharper distinction between ‘work’ and ‘jobs’.

That is, there may be a considerable amount of work that people can do – even if there are very few opportunities to be employed in a job for that purpose. This is not an unfamiliar state of affairs. For many centuries, people (usually women) have performed the work of child-rearing without being employed to do so. Elders and artists, in diverse communities, have done the work of sustaining culture – without their doing so being part of a ‘job’ in any traditional sense. The need for a ‘job’ is not so that we can engage in meaningful work. Rather, jobs are needed primarily in order to earn the income we need to go about our lives.

And this gives rise to what may turn out to be the greatest challenge posed by the widescale adoption of AI. How, as a society, will we fund the work that only humans can do once the vast majority of jobs are being done by machines?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Taking the bias out of recruitment

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why trust-building strategies should get the benefit of the doubt

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

New framework for trust and legitimacy

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

Economic reform must start with ethics

Economic reform must start with ethics

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff 15 AUG 2025

With inflation tamed, interest rates falling and wages rising, the government of Anthony Albanese has worked itself into a position where it can now develop a range of longer-term economic initiatives.

With this in mind, the government will convene an Economic Roundtable next week to consider ideas about how to best to achieve sustainable prosperity.

I suspect that the Roundtable will focus on a range of ‘big ticket’ ideas for innovation and reform in areas such as tax, energy, infrastructure, industrial relations and the like. If all goes well, equal attention will be given to areas of social policy that have a major impact on the economy – including in areas such as childcare, mental health, social welfare, etc. Although not falling under a narrow heading of ‘economic policy’, all of these areas have a significant impact on the productive capacity of the Australian economy. In other words, a strong economy depends as much on sound ‘social’ policies as it does on sound ‘economic’ policies.

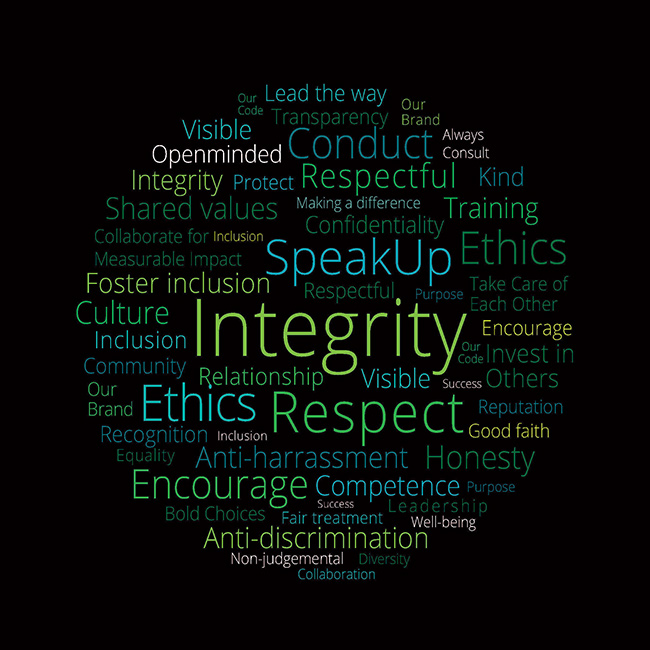

However, there is a deeper ethical dimension that we hope will also be taken into account. Over a period of four years, Deloitte Access Economics has been exploring the link between ethics and the economy. Most recently, its work has zeroed in on the connection between ethics and productivity. Their findings are as follows:

The relationship between ethics and productivity is increasingly recognised in economic literature and international practice.

There is capacity for trust and ethical behaviour to:

- Boost worker wellbeing and mental health, which are directly linked to labour productivity.

- Improve business performance, with higher ethical standards leading to stronger returns on investment.

- Reduce red tape, by lowering the perceived need for regulation in high-trust environments.

- Enable economic reform, by building public support for complex policy changes.

- Accelerate the uptake of technology, such as artificial intelligence, where trust remains a key adoption barrier.

This has remarkable implications for our nation’s prosperity (in both economic and social terms):

- A 10% improvement in ethical behaviour yields a 2.7% wage increase and a 1% gain in mental health, worth over $23 billion across the economy.

- A standard deviation increase in business governance is associated with a 7% increase in return on assets.

- Countries with higher social trust experience 15-19% fewer regulatory procedures to start a business.

- Aligning Australia’s trust levels with global leaders could lift GDP by $45 billion, or $1,800 per person.

There should be no mystery in this, and the effects are clear and simple. Much of it comes down to the possibility of reform (of any kind). Identifying areas of reform is relatively easy. The difficulty relies in their adoption. This is because all reform is subject to resistance from those who fear that they will be left worse off. In turn, strong resistance creates friction that either slows or prevents reform – inevitably leading to sub-optimal outcomes for society as a whole. The number of people who fear being left worse off is often greater than the number of people who will actually be adversely affected. Even when people recognise that they are likely to benefit from reform – they will still oppose it in the belief that the ‘people in charge’ cannot be trusted to ensure that the benefits and burdens are fairly distributed. In other words, it all boils down to questions of trust. And as economists have known since the dawn of their ‘dismal science’ – high trust=low cost and low trust=high cost.

Yet, trust itself is a function of ethical alignment. Ethics, and the trust it engenders, reduces ‘friction’. Thus, trust is a catalyst and enabler of productive reform. To put it simply:

Good ethics → improved trust → greater prosperity.

There are some deep paradoxes in this outcome. The most challenging of these is that although ethics produces a demonstrable economic dividend, it only has maximum effect if people act for non-instrumental reasons. In other words, ‘you don’t get the dividend if you do it for the dividend.’

We have long believed that the whole of Australia would benefit if, as a society, we invested more in revitalising our ‘ethical infrastructure’ alongside the physical and technical infrastructure that typically receives all of the attention and funding.

The evidence is clear that good ethical infrastructure enhances the ‘dividend’ earned from these more typical investments – while bad ethical infrastructure only leads to sub-optimal outcomes.

I doubt that the link between ethics, trust and prosperity will capture any headlines when the Economic Roundtable is convened. But wouldn’t it be great if it could at least be noted as a vital enabler of any reform that hopes to succeed.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

Reports

Business + Leadership

The Ethical Advantage

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 14 MAY 2025

One of the most potent allegories ever to be developed by a philosopher is Plato’s allegory of ‘the cave’.

The story centres around a community of people who are bound, from head to toe, while facing a wall. For the entirety of their lives, nothing is to be seen other than two-dimensional shadows cast by whatever passes between their backs and the source of illumination (the sun or a raging fire). Knowing of no other way to see the world, the chained viewers believe that all of reality is represented by the shadows they perceive. Worse still, they have no concept of ‘shadows’ that might shake their conviction that what they see is ‘real’.

Then, one fateful day, a single individual manages to break their bonds. Free to roam, they encounter a three-dimensional world of colour. Then – only then – do they realise that their life has been defined by error; that the shadows that they once took to represent the whole of reality are nothing more than a simplistic rendering of something far more complex, compelling and beautiful. Inspired by this new understanding, the person returns to liberate others. At first, they are mocked, labelled a lunatic and accused of heresy. Eventually, enough people are freed from their shackles and learn to see.

I used to think it was obvious that everyone would jump at the opportunity to be liberated from ignorance. Most of my working life has been animated by Socrates’ great maxim that, “the unexamined life is not worth living”. After all, is it not the capacity to acknowledge – but also to transcend – our instincts and desires, that makes us human? Is it not obvious that a refusal to examine our lives and to make conscious choices, is actually a refusal to embrace the fullness of our humanity? And is it not the task of philosophy – especially ethics – to equip us so that we might better manage complexity once the chains of unthinking custom and practice are loosened?

As it happens, the ‘shadows’ are far more attractive than I had supposed. In a world of increasing complexity, I have been surprised to see an increasing number of people yearning for their chains in the hope that they might recover the simpler two-dimensional world that they have left behind. I see this in an urge to force what is inherently complex into a deceptively simple form. This is an escape back into a world of shadows – an easier path than that of learning how better to deal with complex reality.

The truth is that most of the important things in life are complex. The ‘messiness’ of the human condition comes from the fact that we have the capacity to make conscious (and conscientious) choices in circumstances of radical uncertainty.

Too often, the choice is not between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ or ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. Values and principles of equal weight can pull us in opposite directions. It is easy to become ‘stuck’, or to face the prospect that the ‘least bad’ alternative is your only viable choice.

Ethics can help us address this messy reality. Not the impossible, flawed ideal of ‘ethical perfection’ – but rather being equipped to live in the uncomfortable light of reality … in all its complexity. We need people to become ‘champions for the common good’. For without dedicated care and attention, our ethical foundations begin to erode.

Ours is a complex world. But when we embrace the ethical dimension of our lives; when we step into the light, nothing can overwhelm and everything becomes possible.

With your support, The Ethics Centre can continue to be the leading, independent advocate for bringing ethics to the centre of everyday life in Australia. Click here to make a tax deductible donation today.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Lies corrupt democracy

One of the most potent threats to democracies is that their elections will be corrupted by lies.

No matter how attenuated in practice, the defining feature of democracies is that the exercise of power is conditional upon the consent of the governed. Consent confers authority. Without consent the exercise of power depends not on democratic legitimacy but instead on the brute force of the autocrat.

For consent to be meaningful, it must be informed. And nothing can be ‘informed’ if it is based on falsehood routinely peddled by those who deal in misinformation and disinformation.

There is nothing new in this. Since antiquity, citizens have always been susceptible to manipulation to skew political outcomes. The difference, today, lies in the speed at which a lie can spread and the breadth of the audience it can reach in an instant. There are also so few individuals or institutions who are trusted to guard and uphold the truth.

Ideally, we might hope that politicians would offer the first line of defence of truth. After all, they have a duty to prioritise the public interest ahead of personal or party interests. Few aspects of the public interest are as important and as obvious as the need to assure the integrity of our democratic elections. Politicians who lie fundamentally undermine the integrity – and therefore the legitimacy – of our elections. In doing so, they betray the public interest.

Despite this, Australia imposes very few penalties on politicians or parties who deliberately lie. This reluctance to punish falsehood is, in part, due to an equal commitment to free speech. We are right to be cautious about introducing measures that restrict free speech for fear of being punished for saying the ‘wrong thing’. It may also be the case that our legislators have a shared interest in not creating a ‘rod’ for their own backs – especially when they can see political advantage in being ‘economical with the truth’.

So, we largely depend on politicians to regulate themselves – with the apolitical Australian Electoral Commission left to manage the worst cases of misinformation and disinformation.

The good news is that politicians are mostly truthful. The bad news is that there are other actors, in the political space, who deliberately seek to manipulate the electorate by manufacturing and propagating misinformation and disinformation. Some of those responsible are state actors who seek to harm countries like Australia by creating or exploiting divisions. They are skilled at using our open information systems as vectors to create states of alarm, confusion and uncertainty – all of which introduces structural weakness and a reduced ability to mount a strong, united response to challenges. Other actors use misinformation and disinformation to advance their ideological or economic interests – by tilting an election in favour of their preferred outcome.

Unfortunately, this kind of interference is now common. Paradoxically, the more it is exposed, the greater the loss of trust in the information presented to us. And that suits the enemies of democracy very well. When a picture or video can be manipulated to the point where you cannot distinguish reality from fiction; when the voice on a phone call is a ‘clone’ based on a thirty second clip – yet is entirely credible; when nothing can be guaranteed to be what it seems to be – how, then, does a voter ever know that they are making an informed decision?

That problem has been solved by financial markets (which also depend on informed decision making) through the profession of auditing. Auditors belong to the profession of accounting. As such, they stand adjacent to the world of the ‘market’ which formally approves the pursuit of self-interest in the satisfaction of the wants of others. The profession of accounting is made up of people who freely choose to abandon the pursuit of self-interest in service of the public interest and a higher ‘good’ – namely the truth.

The role that accountants play in markets is mirrored by the role that journalists are supposed to play in politics – and especially in democracies. Unfortunately, just as some merchants can be relied upon to resort to deception in the pursuit of profits, so can some politicians be relied upon to do the same in the pursuit of victory. Professional journalists are supposed to help protect society from that risk – which is why they are so often lauded as the ‘fourth estate’.

In order to ensure the integrity of our democracy, we need politicians who can be trusted not to lie (even when it advantages them). We need regulators with increased power to identify, curb and punish the activities of those who lie and deceive. We need journalists who place their commitment to the disinterested pursuit of truth ahead of personal or commercial self-interest. We need to be able to distinguish between those who abuse the title ‘journalist’ as false cover and those who genuinely deserve to be trusted. Finally, we need to rally behind and reward media outlets that employ truth-tellers and cease engaging with those who treat the truth as a mere ‘optional extra’.

Fortunately, there are some amongst the political class who are taking steps to encourage truth in politics. A recent initiative, The Ethical Political Advertising Code (EPAC) affords an opportunity for people seeking election to make a public commitment to ‘truth in political advertising’.

Sponsored by Zali Steggall MP, this is a cause that should be apolitical in character – hopefully enjoying the support of any person who cares about the character and quality of our democracy. But this is not just a matter for politicians. It is also something that affects us all.

That is our test as citizens – to choose truth over mere entertainment, to prefer fact to falsehoods that pander to our prejudices.

With so much now at stake in the world, this is a test we must pass. But will we?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Locke

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 10 APR 2025

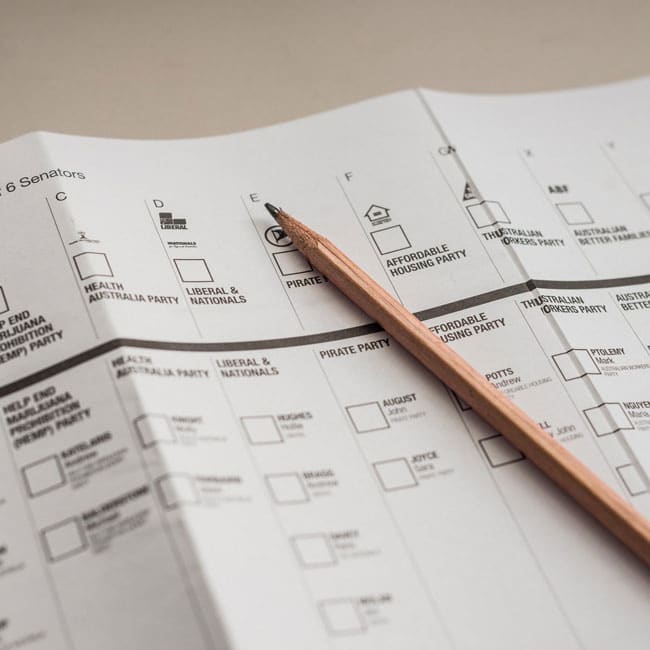

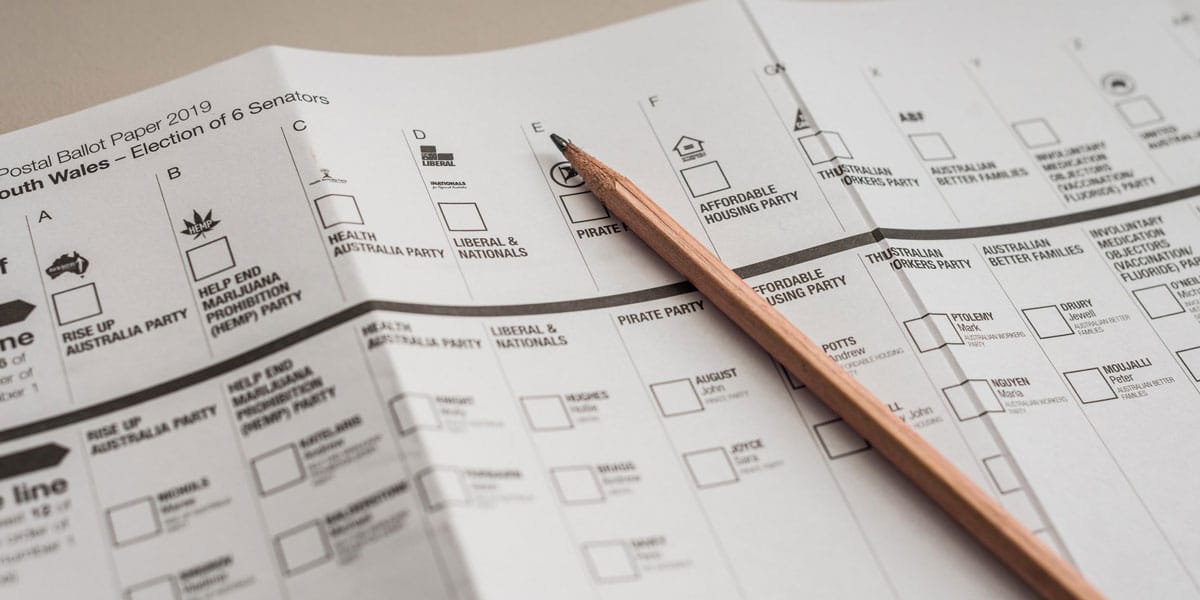

As time goes on, I’m feeling more disenfranchised by politics. I don’t trust any of the current politicians and it seems they don’t represent issues that are affecting everyday Australians, particularly as the inequality gap is widening. Why should I vote this upcoming election, and does my vote even matter?

The issue of voting in Australian elections is often clouded by the mistaken belief that ‘voting is compulsory’. This really annoys people who feel that it impinges on their liberty as citizens – a liberty that should include the right to decide not to vote. In fact, Australia does not impose ‘compulsory voting’. Instead, there is a policy of ‘compulsory turning up’. What we do when we enter the privacy of the polling booth is entirely up to us. We can cast a valid vote. We can leave the ballot paper unmarked. We can write a screed setting out our views. Basically, we can do whatever we like – just as long as we turn up, collect the voting papers and deposit them in the ballot box.

Some will still object to the need to turn up. It won’t matter to them that the need to do so is one of a very small set of obligations that our country has imposed on all its citizens to maintain a well-functioning democracy.

But let’s just assume that, either willingly or reluctantly, we find ourselves in the polling booth – ballot papers in hand – and have to decide whether or not to cast a valid vote. What should we have in mind as we decide?

First, it’s worth remembering that democratic elections do have the potential to bring about change. If we feel that something is wrong with society, then the vote you cast can, in principle and sometimes in practice, enable reforms for the better. It’s understandable to think that your individual vote might not amount to much. But the arc of history is directed by the aggregated effect of individual votes. Alone, this might not amount to much, but collectively it can change the world. Indeed, the fate of a government can sometimes rest on a foundation as fragile as a single vote in a marginal electorate.

Of course, not all of us live in marginal electorates. In apparently ‘safe’ seats it might seem like your vote will be wasted if you cast it for a candidate who apparently has no chance of beating the likely ‘favourite’. Yet, this thinking runs the risk of becoming self-fulfilling. You never know what might happen if just enough people make the same choice you do – and in doing so bring about an unanticipated victory for a candidate who seemed to have no chance of winning. There are many examples of once ‘safe’ seats being lost by major parties that have held them for generations. Just look at the rise in the number of community independents now sitting in our parliaments. They are only there because a majority of citizens preferred them to others and voted accordingly.

It can also work the other way – where you vote for a candidate who apparently already has enough votes to win. Your vote is not ‘redundant’ because the size of a candidate’s margin of victory can be seen as indicative of community support. A larger margin can lend a representative a greater mandate or more political capital to enact their agenda.

Another problem might be that there is not a single candidate or party that you could support in good conscience. There may not even be a ‘least bad’ (but acceptable) option. In any case, with preferential voting there are no ‘wasted votes’. Every ballot counts towards the eventual result. That is one of the problems with choosing to vote ‘informally’ (returning an unmarked ballot). Doing so will make no positive difference to the outcome. The only ‘upside’ is that you might feel that you avoid complicity in enabling an outcome that you could not support in any case.

Yet, perhaps part of our role as electors is to accept that there will be times when the best we can hope for is the ‘least bad’ result. We may have to reconcile ourselves to the fact that there will be occasions when nothing truly inspiring is on offer. If we’re denied the opportunity to vote for someone who reflects our values and principles – and advances our view of what makes for a good world – we might still see value in using our vote to help block those who would undermine everything we stand and hope for.

This brings us to one of the core reasons for voting. Unlike other political systems where authority is derived from God (theocracies) or wealth (plutocracies) or ‘virtue’ (aristocracies), in democracies the ultimate source of authority comes from those who are ‘the governed’ (the people). We get to decide how decisions are made – through popular control of what is in our Constitution. We also get to choose the representatives who will make laws on our behalf. In the end, we have as much control over the system of government as we choose to exercise.

What limits the exercise of that control is not the system – it is our willingness to become politically active.

If you like living in a democracy – but don’t want to get too involved in shaping the system – then there is a low-cost, potentially high impact way to help shape the way it operates. It is to vote.

Image: Gillian van Niekerk / Alamy Stock Photo

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Nurses and naked photos

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

An angry electorate

I recently attended a gathering of people who engage with a remarkably diverse range of Australians.

Members of this group are directly connected with both the wealthiest and poorest in society. Some are city folk; others firmly grounded in the lives of rural, regional and remote communities. They told of the experience and attitudes of people whose circumstances vary considerably – from the most secure to the most precarious in the land.

Remarkably, when asked about the ‘mood’ of the electorate, all told a similar story. Across all demographics, people are disappointed, frustrated and angry. Some of these feelings understandably arise out of the clear failure of our society to meet even the most basic needs of its members. For example, we were told of a regional city, in New South Wales, where 26% of the community are now experiencing food insecurity. That is, a quarter of the population experiencing days where they do not know if they will be able to secure the food they or their family need. We heard of young people – some from relatively affluent families – who doubt that they will ever be able to afford the ‘Australian Dream’ of a home of their own. For some, if not for all, the word ‘crisis’ is an entirely apt description of what far too many people are experiencing.

However, what this cannot explain is the anger felt by even the most affluent.

The seat of the fire is located in a shared (and growing) sense that too many of our politicians and media are ‘fiddling while Rome burns’. Instead of being wholeheartedly focused on the interests of the community, our leading politicians are perceived as being engaged in the trivial game of political-point-scoring, in pursuit of power for its own sake – rather than as a means for realising a larger vision of what could or should be.

This kind of anger is hard to extinguish. There comes a point when even a good policy is discounted by a public that cynically questions the politicians’ motives. This cynicism is exacerbated by a style of politics that is becoming increasingly partisan. One might reasonably doubt that there was ever a ‘golden age’ of politics in Australia. But the decline in widespread public participation in political parties has meant that a relatively small number of factionalised ideologues can take control of a major party. The way the numbers work, they can push increasingly extreme views – unhindered by the ‘sensible middle’ that used to prevail when major political parties really were ‘broad churches’.

I mention all of this because, as we know all too well in Australia, a single ember can easily give rise to a destructive conflagration.

My sense is that the Australian political landscape is bone dry, with the electoral tinder piling up. In this angry environment, one can foresee a moment of nihilistic abandonment; when the idea of ‘burning it all to the ground’ just might catch on.

This we have seen happen in other parts of the world. If only mainstream America had listened attentively to the complaints of people who genuinely felt abandoned by those occupying ‘the swamp’ in Washington DC. Ignored or labelled ‘deplorables’, President Trump became their ‘agent of destruction’. The same forces were at work in the Brexit referendum. A number of those who voted for leaving the EU doubted that their lives would improve. Instead, they took comfort in the fact that those who looked down on them would be worse off.

Our political elite must accept their fair share of responsibility for the increasing level of anger directed at the ‘system-as-a-whole’. However, as citizens of a democracy, we also have a critical role to play. While we might not be able to control our external environment, we are responsible for our response. Knowing what can happen when anger is let loose at its destructive worse, we need to exercise careful restraint and not enflame the situation.

Australian democracy has many faults. And there are plenty of people who have borne the burden of its failures. But it has also helped to sustain one of the world’s better societies. My hope is that politicians – irrespective of party or political persuasion – might take a moment to look beyond party or personal self-interest to ask if their conduct is strengthening or weakening our democracy in the eyes of the electorate. Democratic institutions are not the property of any government, party or faction. They belong to and are exclusively to be used for the benefit of the people. Those who tarnish or degrade those institutions are guilty of public vandalism. So, let’s hold those who do this individually responsible rather than abandon faith in our entire system of democratic governance. And if it happens to be the case that the problem is the system (as may be the case), then let’s work together to decide what would be better – and then build towards that positive outcome.

In turn, we need to dampen down the fires of anger – not be blinded by the smoke of our righteous indignation – no matter how justified it might be. We need a clear vision of what we think makes for a good society. And then we need to elect those who would help us to build rather than tear down.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

If you don’t like politicians appealing to voters’ more base emotions, there is something you can do about it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

If you don’t like politicians appealing to voters’ more base emotions, there is something you can do about it

If you don’t like politicians appealing to voters’ more base emotions, there is something you can do about it

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 5 MAR 2025

The way politicians attempt to garner our votes during an election campaign reveals a great deal about what they think of us as people.

Consider how many politicians try to shore up their standing in the polls by tapping into the emotions of fear and greed. Of the two, playing on personal and communal fear often takes precedence — not least because it is such an easy path to follow. A skilled politician will know how to exploit vulnerability by highlighting what is precarious about our situation and then offer a solution. They will identify an “enemy” who means to cause us harm, and then claim that only they can keep us safe. They will accentuate the differences between “us” and “them” so that they can present themselves as being “on our side”.

The trick is to start with a grain of truth. People are vulnerable. There are some who mean us harm. The community is often divided across boundaries of class, religion, culture, ethnicity and ideology. Next, take that grain of truth and turn it into a mountain that dominates our view of the world. Having ramped up the fear, the skilled politician then offers to come to the rescue — this time eliciting a sense of relief, even gratitude.

An appeal to greed is less dramatic — and often less potent. It is based on the assumption that most people will put self-interest ahead of a concern for others. As Jack Lang, the former Premier of New South Wales, once put it to a young Paul Keating, “Always back the horse named self-interest, son. It’ll be the only one trying.” So, a politician will often promise some kind of personal benefit — usually not to those who might most need what is on offer, but to those whose votes will deliver political victory.

But of course, there is nothing inevitable about politicians appealing to emotions like fear and greed. Such appeals have become part of the political playbook for one simple reason: they work. Campaign strategists are, after all, the ultimate pragmatists, and they would not routinely employ the tactics they do unless they had good reason to believe that they will prove successful.

The message we receive from politicians who resort to such tactics is that they do not believe voters are able to rise above what is base and ignoble.

Which is to say, they do not think of us capable of responding, with equal vigour and commitment, to a style of politics that appeals to something more noble in our character. Indeed, even when the negative tactics work with us, even if we succumb to fear or greed and cast our vote for those who appealed to the lowest common denominator, many of us are left feeling somewhat debased. The persistent question remains: “Is that really all that you think of us? Wasn’t there anything better in us to which you could have appealed?”

That is a very fair and serious question. The core tenet of a democracy is that all power and authority derives from “the people”. But what will be the quality of our democratic polity when the mirror held up to the community by its political leaders presents such a wretched image?

I do not pretend that Australians are an especially virtuous people. We are just as flawed as others — neither more nor less. Which means there are ample opportunities to appeal to what Abraham Lincoln called, in his first inaugural address, “the better angels of our nature”. Why is it not a staple of political discourse to offer a vision of shared prosperity? Why not dwell more on common security based on an account of social cohesion as a positive good, rather than as an antidote to division?

This style of politics — one grounded in hope and inclusion — is much harder work than the politics of deficit and division. But I think the effort is worth making because, at the end of an election cycle, we should be left feeling better about ourselves — both as individuals and as a society. That positive effect should be what every politician seeks to generate. Yes, they want to win, but I would hope it is not “win at any cost”. The ends never justify the means, in the crude sense some people argue to defend the indefensible.

Within a democracy, the outcome of elections ultimately lies in the hands of citizens. We are all equal at the ballot box. We are all able to weigh up the merits of what the candidates for public office put before us. In doing so, I think we should look behind the slogans to consider what underlying message is being conveyed. Do those seeking power hold us in high regard? Do they demonstrate that they recognise the good in us to which they then appeal? Or is their underlying message that they hold us in contempt — diminishing us even as they harvest our vote?

This article was originally published by ABC religion and Ethics.

Image by Jun Li / Alamy Stock Photo

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights