Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 6 DEC 2024

In 2001, Marcellus Williams was convicted of killing Felicia Gayle, found stabbed to death in her home in 1998.

Over two decades later, he was given the death penalty, directly against the wishes of the prosecutor, the jury and, notably, Gayle’s family.

Cases like this draw our attention to the nature of punishment and its role in delivering justice. We can think about justice, and hence what is just punishment, as a question about what we deserve. But who decides what we deserve, and on what basis?

There are many ways that people think about punishment, but generally it’s justified in some variation of the following: retribution, deterrence, rehabilitation, and/or restoration. These are not all mutually exclusive ideas either, but rather different arguments about what should be the primary purpose and mode of punishment

Purposeful Punishment

Punishment is often viewed through the lens of retribution, where wrongdoers are punished in proportion to their offenses. The concept of retributive justice is grounded in the idea that punishment restores balance in society by making offenders ‘pay’ in various ways, like prison time or fines, for their transgressions.

This perspective is somewhat intuitive for most people, as it’s reflected in our moral psychology. When we feel wronged, we often become outraged. Outrage is a moral emotion that often inspires thoughts of harming the wrongdoer, so retributive punishment can feel intuitively justified for many. And while it has roots in our evolutionary psychology, it can also be a harmful disposition to have in a modern context.

The 18th-century philosopher Immanuel Kant strongly defended retributive justice as a matter of principle, much like his general deontological moral convictions. Kant believed that people who commit crimes deserve to be punished simply because they have done wrong, irrespective of whether it leads to positive social outcomes. In his view, punishment must fit the crime, upholding the dignity of the law and ensuring that justice is served.

However, there are many modern critics of retributivism. Some argue that focusing solely on punishment in a retributive way overlooks the possibility of rehabilitation and societal reintegration. These criticisms often come from a consequentialist approach, focusing on how to create positive outcomes.

One of these is an ongoing ethical debate about the role of punishment as a deterrent. This is a consequentialist perspective that suggests punishment should aim to maximise social benefits by deterring future crimes. This view is often criticised because of its implications on proportionality. If punishment is used primarily as a deterrent, there is a high risk that people will be punished more harshly than their crimes warrant, merely to serve as an example. This approach can conflict with principles of fairness and proportionality that are central to most conceptions of justice. Some also consider it to be a view that misunderstands the motives and conditions that surround and cause common crime.

Other, more contemporary, consequentialist views on punishment focus on rehabilitation and restoration. Feminist philosophers, such as Martha Nussbaum, have proposed a broader, more compassionate view of justice that emphasises human dignity. Nussbaum suggests that a purely punitive system dehumanises offenders, treating them merely as vessels for punishment rather than as individuals with the capacity for moral growth and change.

They argue that this dehumanisation is a primary factor in high rates of recidivism, as it perpetuates the cycle of disadvantage that often underpins crime. Hence, an ability for change and reintegration is seen by some as crucial to developing pro-social methods of justice that decrease recidivism.

Importantly, these views are not inherently at odds with traditional punishment, like prison. However, they are critical of the way that punishment is enacted. To be in line with rehabilitative methods, prisons in most countries worldwide would need to see a significant shift towards models that respect the dignity of prisoners through higher quality amenities, vocations, education, exercise and social opportunities.

One unintuitive and hence potentially difficult aspect of these consequentialist perspectives is that in some cases punishment will be deemed altogether unnecessary. For example, if a wrongdoer is found to be impaired significantly by mental illness (e.g. dementia) to the extent that they have no memory or awareness of their wrongdoing, some would claim that any type of retributive punishment is wrong, as it serves no purpose aside from satisfying outrage. This can be a difficult outcome to accept for those who see punishment as needing to “even the scales”.

Justice and Punishment

The ethical implications of punishment become even more complex when considering factors like bias and the reality of disproportionate sentencing. For example, marginalised groups face more scrutiny and harsher sentences for similar crimes, both in Australia and globally. This disparity is often unconscious, resulting in a denial of responsibility at many steps in the system and a resistance to progress.

If punishment is disproportionately applied to disadvantaged groups, then it is not just. The ethical demand of justice is for equal treatment, where punishment reflects the crime, not the social status or identity of the offender.

Whether our idea of punishment involves revenge or benevolence, it’s important to understand the motivations behind our convictions. All the sides of the punishment spectrum speak to different intuitions we hold, but whether we are steadfast in our right to get even, or we believe an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind, we must be prepared to find the nuance for the betterment of us all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What does Adolescence tell us about identity?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

6 dangerous ideas from FODI 2024

From dangerous dissenters to powerful provocations – this year Festival of Dangerous Ideas speakers covered some of the thorniest dilemmas of our time.

Here are 6 things we learnt at FODI 2024:

Our ideological chambers can be dismantled, but only if we can listen to others

Sharing some of the more extreme responses to her work, cultural critic Roxane Gay examines the costs of unapologetically sharing bold ideas and opinions.

Speaking to the current state of fragmented discourse, where our political differences are more calcified than ever, Gay says “This mode of discourse assumes that what we believe in and our faith in what we know are so fragile that they cannot stand thoughtful engagement”. In her talk, she says there is still hope to create progress if we are able to become more elastic in our thoughts, “to stop screaming and start listening”.

The machines are killing our kids

Psychologist Jean Twenge makes the case that younger generations are suffering in life-altering ways because of the amount of time they spend looking at screens. Through years of research and millions of survey responses, she argues that since the proliferation of smartphones, adolescents and teens are increasingly and significantly more likely to suffer from symptoms of depression, while simultaneously are much less likely to engage in positive wellbeing practices like sleeping enough, seeing friends or exercising.

Twenge proposes that a radical shift in the amount we use our phones is needed (as young people, as parents and as a society) to reverse these harmful effects.

We need to engage in a culture of growth rather than cancellation

If podcast host Megan Phelps-Roper had left the extremist Westboro Baptist Church today, cancel culture might have meant she’d never have been forgiven, and she wouldn’t have become such a powerful voice for persuasion and reconciliation. Speaking on the Uncancelled Culture panel, Megan argues for a radical form of forgiveness, where we’re forced to recognise someone’s humanity, consider not just what they did but why, and take a chance on the possibility of redemption. While it can be difficult for us to set aside our sense of justice to engage with empathy, just as it can be difficult for us to express contrition for our own errors, but it’s only in doing so that we will shift from cancel culture to a culture of growth.

Coming to terms with our desire for something greater can help us understand the human condition

In a cheeky conversation and book reading, comedian and author David Baddiel says his desperate desire for God convinced him that there isn’t one. “Desire provides no frame for reality”, says Baddiel. This recognition can at once be a liberation from our impulses, while at the same time be a reminder and a call for us to embrace the common humanity that compels us all to crave order within the chaos of life.

In difficult conversations, the most effective tool to communicate with our opponent is empathy

One year on from the release of the divisive podcast series The Witch Trials of JK Rowling, host and former member of the Westboro Baptist Church Megan Phelps Roper, and podcast producer and journalist Andy Mills reflect on the radical power of listening when we come across viewpoints in direct opposition of our own.

As they dissect the reasoning that led them to wade into the difficult cultural conversation surrounding sex and gender, Phelps-Roper cites her previous experience talking at the 2018 Festival of Dangerous Ideas about leaving the Westboro Baptist church “Listening is not agreeing, empathy is not a betrayal of your cause… My life was profoundly changed by exactly that kind of dialogue. It’s what caused me to leave extremism and find meaning and love and freedom and grace in a world I’d been taught was evil”.

Denial sustains liberal imagination

How can a left leaning Western person reconcile the commitment to democracy and civil rights, with support for a state that practices apartheid? Academic Saree Makdisi argues it’s because we are living in a culture of denial. He says the mechanisms of occlusion, narrative and appealing to progressive Western values serve to make us overlook the world’s horrors.

Catch up on select FODI 2024 sessions, streaming on demand for a limited time only.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Freedom of expression, the art of…

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture

Read me once, shame on you: 10 books, films and podcasts about shame

Ethics explainer: The principle of charity

The principle of charity suggests we should assume good intentions about others and their ideas, and give them the benefit of the doubt before criticising them.

British philosopher and mathematician, Bertrand Russell, was one of the sharpest minds of his generation. Anyone deigning to offer a lecture in his presence at Cambridge University was sure to have every iota of their reasoning scrutinised and picked apart in excruciating detail.

Yet, it’s said that before criticising arguments, Russell would thank them warmly for sharing their views, then he might ask a question or two of clarification, then he’d summarise their position succinctly – often in more concise and persuasive terms than they themselves had used – and only then would he expose its flaws.

What Russell was demonstrating was the principle of charity in action. This is not a principle about giving money to the poor, it’s about assuming good intentions and giving others the benefit of the doubt when we interpret what they’re saying.

The reason we need charity when listening to others is that they rarely have the opportunity to say everything they need to say to support their view. We only have so many minutes in the day, so when we want to make an assertion or offer an argument, it’s simply not possible to account for every assumption, outline every implication and cover off all possible counterarguments.

That means there will inevitably be things left unsaid. Given our natural propensity to experience disagreement as a form of conflict, and thus shift into a defensive posture to protect our ideas (and, sometimes, our identity), it’s all too easy for us to fill in the gaps with less than charitable interpretations. We might assume the person speaking is ignorant, foolish, misled, mean spirited or riddled with vice, and fill the gaps with absurd assertions or weak arguments that we can easily dismantle.

We also have to decide whether they are speaking in good faith, or whether they’re just engaging in a bit of virtue signalling and didn’t really mean to offer their views up for scrutiny, or whether they’re trying to troll us. Again, it’s all too easy to allow our suspicions or defensiveness to take over and assume someone is speaking with ill intent.

However, doing so does them – and us – a disservice. It prevents us from understanding what they’re actually trying to say, and it blocks us from either being persuaded by a good point or offering a valid criticism where one is due. Failing to offer charity is also a sign of disrespect. And it’s well known that when people feel disrespected, they’re even more likely to double down on their defensiveness and fight to the bitter end, even if they might otherwise have been open to persuasion.

It’s probably no surprise to hear that the internet is a hotbed of uncharitable listening. Many people have been criticised, dismissed, attacked or cancelled because they have said or done something ambiguous – something that could be interpreted in either a benign or a negative light. Some commentators on social media are all too ready to uncharitably interpret these actions as revealing some hidden malice or vice, and they leap to condemnation before taking the time to unpack what the speaker really meant.

Charity requires more from us, but the rewards can be great. Charity starts by assuming that the person speaking is just as informed, intelligent and virtuous as we are – or perhaps even more so. It encourages us to assume that they are speaking in good faith and with the best of intentions.

It requires us to withhold judgement as we listen to what’s being said. If there are things that don’t make sense, or gaps that need filling, charity encourages us to ask clarificatory questions in good faith, and really listen to the answers. The final step is to repeat back what we’ve heard and frame it in the strongest possible argument, not the weakest “straw man” version. This is sometime referred to as a “steel man”.

Doing this achieves two things. First, the speaker will feel heard and respected. That immediately puts the relationship on a positive stance, where everyone feels less need to defend themselves at all costs, and it can make people open to listening to alternative viewpoints without feeling threatened.

Secondly, it gives you a fighting chance of actually understanding what the other person really believes. So many conversations end up with us talking past each other, getting more frustrated by the minute. Arriving at a point of mutual understanding can be a powerful way to connect with someone and have an actually fruitful discussion.

It is important to point out that exercising charity doesn’t mean agreeing with whatever other people say. Nor does it mean excusing statements that are false or harmful.

Charity is about how we hear what is being said, and ensuring that we give the things we hear every possibility to convince us before we seek to rebut them.

However, if we have good reason to believe that what they’re saying, after we’ve fully understood it in its strongest possible form, is false or harmful, then we need not agree with them. Indeed, we ought to speak out against falsehood and harm whenever possible. And this is where exercising charity, and building up respect, might make others more receptive to our criticisms, as were many of the people who gave a lecture in the presence of Bertrand Russell.

The principle of charity doesn’t come naturally. We often rail against views that we find ridiculous or offensive. But by practising charity, we can have a better chance of understanding what people are saying and of convincing them of the flaws in their views. And, sometimes, by filling in the gaps in what others say with the strongest possible version of their argument, we might even change our own mind from time to time.

This article has been updated since its original publication on 10 March 2017.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Immanuel Kant

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Now is the time to talk about the Voice

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

10 dangerous reads for FODI24

Exploring crumbling democracies and generational warfare to moral panic, The Festival of Dangerous Ideas returns 24-25 August to Carriageworks, Sydney.

FODI24 will create a sanctuary for those wanting to cut through the noise, ask hard questions and engage in good faith conversation about the most challenging issues of our time.

Sharpen your mind with 10 dangerous books from this year’s line-up of thinkers, artists, experts and disruptors. You know, the books you need to buy before they are banned, burnt or redacted forever…

Roxane Gay: Opinions

Focusing on the art of argument, this retrospective of essays and writings from culture critic Roxane Gay covers politics, race and identity, feminism, popular culture, and more.

Roxane Gay // How to Have Dangerous Ideas // Sat 24 August, 12:30pm

David Runciman: How Democracy Ends

A provocative book by political philosopher and historian David Runciman, asks the most trenchant questions that underlie the disturbing patterns of our contemporary political life.

David Runciman // Votes for 6 Year Olds // Sat 24 August, 4:30pm

Jean Twenge: iGen

Drawing from nationally representative surveys of 11 million young people as well as in-depth interviews, iGen is the first book to document the cultural changes shaping today’s teens and young adults, documenting how their changed world has impacted their attitudes, worldviews, and mental health.

Jean Twenge // The Machines Killing Our Kids // Sat 24 August, 10:15am

David Baddiel: The God Desire

A philosophical essay that utilises comedian David Baddiel’s trademarks of storytelling and personal anecdotes, offering a highly readable new perspective on the most ancient of debates.

David Baddiel // The God Desire // Sun 25 Aug, 6:45pm

Megan Phelps-Roper: Unfollow

A gripping memoir of escaping extremism, podcast host Megan Phelps-Roper uncovers her moral awakening, her departure from the Westboro Baptist Church, and how she exchanged the absolutes she grew up with for new forms of warmth and community. Her story exposes the dangers of black-and-white thinking and the need for true humility in a time of angry polarisation.

Megan Phelps-Roper & Andy Mills // The Witch Trials // Sat 24 Aug, 6:30pm

Jem Bendell: Breaking Together

In an era of societal collapse, academic Jem Bendell explores how the full pain of our predicament can liberate us into living more courageously and creatively.

Jem Bendell // Breaking Together // Sun 25 Aug, 3:45pm

Saree Makdisi: Tolerance is a Wasteland

Academic Saree Makdisi reveals the system of emotional investments and curated perceptions that sustains the liberal imagination of a progressive and democratic Israel.

Saree Makdisi // Tolerance is a Wasteland // Sun 25 Aug, 12:45pm

Masha Gessen: Surviving Autocracy

A guide to understanding and recovering from the calamitous corrosion of American democracy over the past few years from Russian-born writer and journalist Masha Gessen.

Masha Gessen // The War of the Narratives // Sat 24 August, 2:30pm

Jen Gunter: Blood

A book from the Internet’s OBGYN that fights myths and fear mongering with real science, inclusive facts, and shame-free advice on the topic that impacts more than 1.8 billion people worldwide: menstruation.

Jen Gunter // Lifting the Curse // Sun 25 Aug, 11:45am

Coleman Hughes: The End of Race Politics

Author Coleman Huges makes the case for a colorblind approach to politics and culture, warning that the so-called ‘anti-racist’ movement is driving us—ironically—toward a new kind of racism.

Coleman Hughes & Josh Szeps // A Colourblind Society: Uncomfortable Conversations Live // Sun 25 Aug, 4:45pm

These titles, plus more will be available at the Dangerous Books x Gleebooks popup – running 10am-8pm across 24-25 August at Carriageworks, Sydney. Check out the full FODI program at festivalofdangerousideas.com

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We are pitching for your pledge

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Meet James Shipton, our new Fellow uncovering the ethics of regulation

Meet James Shipton, our new Fellow uncovering the ethics of regulation

READBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 23 JUL 2024

We’re thrilled to announce we’ve appointed James Shipton as an Ethics Centre Fellow.

Former chair of ASIC and one of Australia’s top corporate regulators, James has over 20 years experience in regulation, financial markets, the law and academia, both internationally and in Australia.

Most recently, he was the Executive Director of Harvard Law School’s Program on International Financial Systems. Prior to that, his career has included Executive Director and Commission member of the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) of Hong Kong and almost a decade at Goldman Sachs in Hong Kong.

To welcome him, we sat down with James to discuss the role ethics plays when it comes to regulation and the banking and financial services industry.

Tell us, what draw you to a career in the financial services sector?

Finance always fascinated me ever since my father took me to the Melbourne Stock Exchange after school one day in the 1970s. I remember him taking me into the ‘open outcry’ market and explaining how the ‘chalkies’ wrote the bid and offer prices on black board on a mezzanine. It was exciting, noisy, and thrilling. I was hooked.

As I got older, I realised the important societal role finance played; in addition to its economic one. It facilitated modern life and allowed us all to plan for the future and prepare against risks. It is this interconnection between finance’s economic and social roles that fascinates me; that is also an intersection that is under-appreciated, including by people working in finance.

Reflecting on the Hayne Royal Commission and your role at ASIC are you now seeing some positive changes to the industry?

Yes and no. Paradoxically, the larger financial institutions were the ones who have moved in a more positive direction whilst various governments and government agencies have let the momentum slip from the Royal Commission. Perhaps, in part this was because of the pandemic but it was also ideological and/or political. The way I have described it, the Royal Commission provided a ‘sugar hit’ to ASIC and APRA; but that was fleeting, and we have returned to the status quo of lack of policy and funding prioritisation for those all-important regulators.

What kind of work will you be engaging with at The Ethics Centre?

I am currently writing a book on optimising regulation by improving regulatory design, governance, and strategy. As part of this project, I am developing ways and means for regulators and regulated persons to better understand each other; by doing so the purpose of regulation will more likely be achieved. There is a wonderful expression in Cantonese, ‘gai tong aap gong’ which translates to ‘the duck is talking to the chicken’. That is how I see regulators and the regulated; they both look similar, but they are each talking a completely different language and cannot understand the other.

Accordingly, I am working with the Centre to develop greater understanding between regulators and those regulated using ethics and professional integrity as a bridge.

I am also contributing to The Ethics Alliance & the BFSO Young Ambassadors by helping them to better understand the purpose of regulation as well as pass on some of my own professional challenges and experiences.

What does regulation mean to you? And where does ethics sit in the regulatory world?

‘Regulation’ is a much-misunderstood concept; particularly by regulators. Regulation is the modification of behaviours pursuant to norms in a sector of importance to society. Put simply, ‘regulators are in the behavioural modification business’. And since regulation is all about ‘norms’ and ‘behaviour’, ethics plays a large part in this equation.

Australia is commonly called a ‘nanny state’. From an international perspective do you think this is a fair label? As a society are we overregulating?

We have to move beyond the debate of ‘over’ or ‘under’ regulating and, instead, get regulation ‘right’. Regulatory systems are far from their optimal state because of a series or structural flaws. First of which is a lack of precision in the objectives or purpose of regulatory systems. My research suggests that most regulators lack a meaningfully precise articulation of their job; that articulation via their statutory purpose or ‘objectives’ is, usually, either as ‘wide a as the Nullarbor Plain’ or highly prescriptive but full of inconsistencies. Unlike central banks who have a clear, precise, and measurable mandates (financial stability, price stability, employment, and/or economic growth), regulators are left to interpret, execute, and then explain unclear, imprecise, and ultimately unmeasurable objectives. From this flows a raft of structural flaws that prevent regulators from ever succeeding (how can they if their definition of ‘success’ is unclear or absent!?).

Self-regulation has proven to realistically not be enough to steer people to making good choices, what do you think are the driving factors that prevent people from doing the right thing?

Self-regulation often (not always) fails for the same reason regulators fail; their objectives are unclear and/or they do not use the full suite of regulatory tools to change behaviour (especially enforcement). Regulation is the utilisation of incentives and disincentives to modify behaviour; rarely does one work without the other.

Do you think people who break the rules are bad or is it our systems that are bad?

A criminal barrister once described his clients to me as “bad, mad, or sad”, adding quickly that ‘most of them are just sad’. In the world of white colour crime, it is probably more a mixture of bad and sad; the latter usually seeing the person descend into the abyss of misconduct. Two must read books about this are: Nick Leeson’s Rogue Trader (how he triggered the collapse of Baring Bros.) and Wizard of Lies: Bernie Madoff and the Death of Trust by Diana Henriques.

Taking the ‘bad’ and ‘sad’ analogy further, our regulatory system needs to account for both. It must be as effective and credible as possible to disincentivise the ‘bad’ against wrongdoing; and incentivise the ‘sad’ to adhere to the purpose of regulation (again, this is why ‘regulatory purpose and objectives’ are so vital).

If you were to be an Australian ambassador to a country, which country would you choose and why?

India in a heartbeat. We have so much in common with India and the potential there – economic, cultural, and societal – is vast. (I also love the food).

And lastly the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

Its everything; its my guiding light. My personal motto is to ‘be a good person by doing good things in a good way’.

Image by Aaron Francis

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Blockchain: Some ethical considerations

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Ethics Explainer: Cancel Culture

When mass outrage is weaponised and encouraged, it can become more of a threat to the powerless than to those it’s intended to hold to account.

In 2017, comedian Louis C.K. was accused of several instances of sexual misconduct, to which he later admitted in full. This was followed by a few cancelled movies, shows and appearances before he stepped away from public life for a few years.

In 2022, lecturer Ilya Shapiro was put on leave following a tweet he posted a few days before he was employed. Shapiro contended that the university failed in its commitment to free expression by investigating his actions for four months, before reinstating him under the reason that he was not accountable to the university for actions taken before his employment started.

These are both instances of what some people would call “cancel culture”, yet they involve very different issues. To unpack them, we first need to define what we mean by cancel culture.

From around 2015 onwards, the term started gaining mainstream traction, eventually being named Word of the Year by Macquarie Dictionary in 2019:

“The attitudes within a community which call for or bring about the withdrawal of support from a public figure, such as cancellation of an acting role, a ban on playing an artist’s music, removal from social media, etc., usually in response to an accusation of a socially unacceptable action or comment by the figure.”

The quintessential examples of cancel culture are calls from groups of people online for various public figures to be stripped of support, their work boycotted, or their positions removed following perceived moral transgressions. These transgressions can be anything from a rogue tweet to sexual assault allegations, but the common theme is that they are deemed to be harmful and warrant some kind of reaction.

A notoriously contentious concept, cancel culture is defined, or at least perceived, differently based on the social, cultural and political influences of whom you ask. Though its roots are in social justice, some believe that it lacks the nuance needed to meet the ends it claims to serve, and it has been politicised to such an extent that it has become almost meaningless.

Defenders of accountability

The ethical dimensions of this phenomenon become clear when we look at the various ways that cancel culture is understood and perceived by different groups of people. Where some people see accountability, others see punishment.

Defenders of cancel culture, or even those who argue that it doesn’t exist, say that what this culture really promotes is accountability. While there are examples of celebrities being shamed for what might be conceived as a simple faux pas, they say that the intent of most people who engage in this action is for powerful to be held accountable for words and actions that are deemed seriously harmful.

This usually involves calls to boycott, like the ongoing attempts to boycott J.K. Rowling’s books, movies and derivative games and shows because of her vocal criticism of transgender politics since 2019, or like the many attempts to discourage people from supporting various comedians because of issues ranging from discriminatory sets to sexual misconduct and harassment.

Those who view cancel culture practices as modes of justice feel that these are legitimate responses to wrongdoings that help to hold people with power accountable and discourage further abuses of power.

In the case of Louis C.K., it was widely viewed that his sexual misconduct warranted his shunning and removal from upcoming media productions.

Public figures are not owed unconditional support.

While it’s not clear that this kind of boycotting does anything significant to remove any power from these people (they all usually go on to profit even further from the controversy), it’s difficult to argue that this sort of action is unethical. Public figures are in their positions because of the support of the public and it could be considered a violation of the autonomy we expect as human beings to say that people should not be allowed to withdraw that support when they choose.

Where this gets sticky, even for supporters of cancel culture, is when people with relatively little power become the targets of mass social pressure. This can lead to employers distancing themselves from the person, sometimes ending in job loss, to protect the organisation’s reputation. This is disproportionately harmful for disadvantaged people who don’t have the power or resources to ignore, fight, or capitalise on the attention.

This is an even further problem when we consider how it can cause a sense of fear to creep into our everyday relationships. While people in power might be able to shrug off or shield themselves from mass criticism, it’s more difficult for the average person to ignore the effects of closed or uncharitable social climates.

When people perceive a threat of being ostracised by friends, family or strangers because of one wrong step they begin to censor themselves, which leads to insular bubbles of thoughts and ideas and resistance to learning through discussion.

Whether this is a significant active concern is still unclear, though there is some evidence that it is an increasing phenomenon.

Defenders of free speech

Given this, it’s no surprise that the prevailing opposition to cancel culture is framed as a free speech and censorship issue, viewed by detractors as an affront to liberty, constructive debate, social and even scientific progress

Combined with this is a contention that cancelling someone is often a disproportionate punishment and therefore unjust – with people sometimes arguing that punishment wasn’t warranted at all. As we saw earlier, this is particularly a problem when the punishments are directed at disadvantaged, non-public figures, though this position often overstates the effect the punishments have on celebrities and others in significant power.

A problem with the claim that cancel culture is inherently anti-free speech is that, especially when applied to celebrities, it relies on a misconception that a right to free speech entails a right to speak uncontested or entitlement to be platformed.

In fact, similar to boycotting people we disagree with, publicly voicing concerns with the intention of putting pressure on public figures is an exercise in free speech itself.

Accountable free speech

An important way forward for both sides of issue is the recognition that while free speech is important, the limits of it are equally so.

One way we can do this is by emphasising the difference between bad faith and good faith discussion. As philosopher Dr Tim Dean has said, not all speech can or should be treated equally. Sometimes it is logical and ethical to be intolerant of intolerance, especially the types of intolerance that use obfuscating and bad faith rhetoric, to ensure that free speech maintains the power to seek truth.

Focusing on whether a discussion is being had in bad faith or good faith can differentiate public and private discourse in a way that protects the much-needed charitability of conversations between friends and acquaintances.

While this raises questions, like whether public figures should be held to a higher standard, it does seem intuitive and ethical to at least assume the best of our friends and family when having a discussion. We are in the best place to be charitable with our interpretations of their opinions by virtue of our relationships with them, so if we can’t hold space for understanding, respectful disagreement and learning, then who can?

Another method for easing the pressures that public censures can have on private discourse is by providing and practicing clear ways to publicly forgive. This provides a blueprint for people to understand that while there will be consequences for consistent or shameless moral transgressions, there is also room for mistakes and learning.

For a deeper dive on Cancel Culture, David Baddiel, Roxane Gay, Andy Mills, Megan Phelps-Roper and Tim Dean present Uncancelled Culture as part of Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2024. Tickets on sale now.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Ethics Explainer: WEIRD ethics

If you come from a Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic society, then you’re WEIRD. And if you are, you might think about ethics differently than a majority of people alive today.

We all assume that we’re normal (to at least some degree). And it’s natural to assume everyone else sees the world at least somewhat similarly to the way we do. This is such a pervasive phenomenon that even psychology researchers have fallen into this trap, and it has influenced the way they have conducted their studies and the conclusions they have drawn about human nature.

Many psychology studies purport to investigate universal features of the human mind using a representative sample of people. However, the problem is that these samples are not typical of humans. The usual test subject in a psychology study is drawn from a very narrow pool, with around 80 percent being undergraduate students attending a university in the United States or another Western country.

If human psychology really was universal, this selection bias wouldn’t matter. But it turns out our minds don’t all work alike, and culture plays a huge role in shaping how we think. Even features of our minds that were once believed to be universal, such as depth perception, vary from one culture to another. For example, American undergraduate students are far more likely to see the two lines in the classic Muller-Lyer illusion as being significantly different lengths, whereas San forages of the Kalahari in southern Africa are virtually immune to the illusion.

But it’s not just perception that varies among cultures. It’s also the way we think about right and wrong, which has serious ramifications for how we answer ethical questions.

WEIRD ethics

Imagine you and a stranger are given $100 to split between you. However, there’s a catch. The stranger gets to decide how much of the $100 to offer you and what proportion they get to keep. They could split it 50:50, or 90:10. It’s all up to them. If you accept their offer, then you both get to keep your respective proportions. But if you reject the offer, you both get nothing.

Now imagine they offered you $50. Would you accept? It turns out that most people from Western countries would. But what if they offer you $10, so they get to keep $90? Most WEIRDos would reject this offer, even if it means they miss out on a “free” $10. One way to look at this is that WEIRD subjects were willing to incur a $10 cost to “punish” the other for being unfair.

This is called the Ultimatum Game, and it’s much studied in psychology and economics circles. For quite some time, researchers believed it showed that people are naturally inclined to offering a fair split, and recipients were naturally willing to punish those who offered an unfair amount.

However, repeated experiments have since shown that this is largely a WEIRD phenomenon, and individuals from non-WEIRD cultures, particularly from small-scale societies, behave very differently. People from these cultures were far more likely to offer a smaller proportion to their partner, and the recipients were far more likely to accept low offers than people from WEIRD cultures.

So, instead of revealing some universal sense of fairness, what the Ultimatum Game did was reveal how different cultures, and different social norms, shape the way people think about fairness and punishment. Far from being universal, it turns out that much of our thinking about fairness is a product of the culture in which we were raised.

It’s conventional

Another fascinating discovery that emerged from comparing WEIRD with non-WEIRD populations was that different cultures think about ethics in very different ways.

Research by Lawrence Kohlberg in the United States in the 1970s uncovered patterns in how children develop their moral reasoning abilities as they age. Most children start off viewing right and wrong in purely self-interested terms – they do the right thing simply to avoid punishment. The next stage sees children come to understand that moral norms keep society functioning smoothly, and do the right thing to maintain social order. The third stage of development goes beyond social conventions and starts to appeal to abstract ethical principles about things like justice and rights.

While these stages have been observed in most WEIRD populations, cross-cultural studies have found that non-WEIRD people from small-scale societies don’t tend to exhibit the final stage, with them sticking to conventional morality. And this has nothing to do with lack of education, as even university professors in non-WEIRD societies show the same pattern of moral thinking.

So, rather than showing clear stages of moral development, Kohlberg’s research just revealed something unique about WEIRD people, and their cultural emphasis on autonomy, while many other societies emphasise community or divinity as the basis of ethics.

Who are you?

The research on WEIRD psychology, has led to a significant shift in the way that psychologists and philosophers think about morality. On the one hand, it has shown that many of our assumptions about human universals in moral thinking are strongly influenced by our own cultural background. And on the other, it has shown that morality is a hugely more diverse landscape than was often assumed by WEIRD philosophers.

It has also caused many people to reflect on their own cultural influences, and pause to realise that their perspective on many important ethical issues might not be shared by a majority of people alive today. That doesn’t mean that we should lapse into a kind of anything-goes moral relativism, but it does encourage us to exercise humility when it comes to how certain we are in our attitudes, and also seek strong reasons to support our ethical views beyond just appealing to the contingencies of our upbringing.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

READ

Society + Culture

6 dangerous ideas from FODI 2024

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does your body tell the truth? Apple Cider Vinegar and the warning cry of wellness

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 22 MAY 2024

New and challenging ideas are endangered species these days. They are surrounded by predators from all sides.

There are the entrenched interests that want to maintain the status quo. There are trolls who will beat them down just for laughs. Then there is the threat of cancellation by those who deem challenging ideas unworthy of being expressed at all.

Yet, as their natural habitat is being invaded, we as a society need these ideas to thrive more than ever before. We must continually challenge our assumptions, for history has shown us how often they end up being false. We must be wary of the status quo, and the powers that work to preserve it for their own benefit (and our detriment). We need to have open and honest conversations, lest our minds – and our ideas – become outdated and stale in a fast-moving world.

What we need is a sanctuary where new and challenging ideas can be nurtured and kept safe from the predators until they’re strong enough to be released into the wilderness and thrive. We need a space where they can be heard with open ears and challenged by open minds. A space where discourse is steered by good faith and reason rather than tribalism and fury.

FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey, says that is what The Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI, to its fans) is all about this year. “In a litany of entrenched ideas, 24-hour news cycles, shallow information and self-censorship, we desperately need a space where we can engage with challenging ideas in good faith.”

FODI is a “sanctuary”, not just as a refuge to keep us safe from the noise, the trolls and the bad faith speakers found in the wilderness of public discourse, but a space where we’re safe to engage with powerful and provocative ideas.

A lot is said about “safe spaces” these days. But they’re typically talking about only one type: “safe from…” spaces, where people can be protected from things that might be harmful, triggering, discriminatory or distressing. These spaces are important in a world filled with dangers, because we should always respect the inherent dignity and vulnerability of others, and seek to protect them from harm.

But if we only have “safe from…” spaces, we risk shutting down difficult conversations that we might have to have. We might stifle precisely the kinds of discourse that could make “safe from…” spaces less necessary. We can end up being coddled rather than becoming resilient or testing our own ideas.

FODI exemplifies another kind of safe space: “safe to…”. This is a space where people are able to express themselves authentically and in good faith without fear of reprisal, where they can engage with difficult and controversial topics that might even be deemed offensive in other contexts. These are the conversations we have to have if we’re to combat the problems that make “safe from…” spaces necessary.

“FODI is gives us an opportunity to hear powerful and provocative speakers from around the world talk on important and rousing topics,” says Harvey. It’s also a sanctuary. One where “audiences can engage with these ideas in a way that we, unfortunately, can’t in the wild. In our sanctuary you are safe from hype and safe to listen and to ask questions.”

Such a sanctuary needs to be carefully curated to enable open good faith engagement with dangerous ideas. That’s why this year’s FODI will be special. When you come to FODI, you will enter a sacred space, with a shared understanding of our mutual purpose and a will to create a better world. A space to let curiosity guide you, where good faith reigns, where you’re free from intimidation and shame for what you choose to believe and express, a safe place to think deeply about the world.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas returns 24-25 August 2024 to Carriageworks, Sydney. Subscribe for program updates at festivalofdangerousideas.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Where did the wonder go – and can AI help us find it?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 22 APR 2024

If you’re looking to start investing in the stock market (and you’ve stumbled across this article), chances are you might be investigating how you can do it ethically – without supporting companies that are actively causing harm to the world.

“Ethical investing” has no fixed definition in Australia, Life and Shares host Cris Parker points out in The Ethics Centre’s latest podcast. Susheela Peres Da Costa, Chair of the Responsible Investment Association of Australasia (RIAA), says typically ethical, or responsible, investing is about, “consumers assuming something is screened out of the portfolio – what you don’t invest in is a typical ethical investment question.”

But finding out which companies are involved in activities you don’t want to financially support is not as cut and dried as you might hope.

“There’s a lot of seductively simple solutions out there,” Peres Da Costa says, such as points-based system ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance Investing).

“Some of the most profitable companies involved in some of the most harmful activities actually do very well on some of the scoring systems,” Da Costa says, “because they’ve got great volunteering programs and programs for replacing their light bulbs with LEDs, and they give a lot of money to charity. But investors need to be smart about not falling for the gloss. As someone who’s professionally analysed company reports, I would never, ever believe anything in a value statement…”

“However, we really need to address the elephant in the room, which is actually the cost. It is just so expensive to obtain proper financial advice – to give you an example, the median price in Australia is $5,000 per year.”

Even if you don’t think of yourself as being in the stock market, if you have super in Australia, then your super fund is investing your money on your behalf. Happily, many super funds offer investment packages classified as “sustainable”, which aim to buy into clean and renewable energy shares and avoid companies involved in fossil fuels.

The RIAA ranks Australian super funds on their responsible investment approaches: its Responsible Investment Super Studies highlight funds that choose shares in companies that aim to do good for people and the earth and screen out those with poor or questionable practices.

Still, the waters are murky as to which companies are doing the most harm, and which are trying to do good. As Life and Shares host Cris Parker points out, one of the best performing sustainable exchange traded funds in the past year had a large holding in mining company BHP.

But that’s not necessarily a bad thing, says Da Costa. “It’s easy to think about mining companies as those that dig up the ground, tear down the trees and all those things. But they’re also the ones that are producing the lithium, for example, and all the rare earths that we need to transition from our dependence on fossil fuels. So I think one of the things you have to be really careful of is assuming that a company is one thing, good or bad.”

“One of the things you have to be really careful of is assuming that a company is one thing, good or bad.” – Peres Da Costa

Of course, there’s no legislation to prevent you from investing in whatever you want – and if you don’t buy shares in a particular company, someone else probably will. Unless you have the financial power to buy a controlling stake, you won’t be able to control board decisions as a shareholder. But it doesn’t mean you can’t try.

“If your objective is to have an impact in the world, then the levers that you have available to you are very different if you’re a consumer versus an institution, and you need to have a theory of change about how you have that impact,” Da Costa says.

A theory of change is a conceptual model outlining the specific actions and interventions your investments will use to achieve the desired impact. In the case of sustainability and climate change, this means putting your money into renewables, divesting from fossil fuel companies, and being an active shareholder – paying attention to what your invested companies are doing, and wielding your shareholder voting power at AGMs (Annual General Meetings).

One simple action that should be on every good global citizen’s to-do list is checking your super fund’s ethical position and investments, along with checking where your bank invests and if your power company uses renewables or coal and gas.

Looking to your own values and ethics, and using those as a guide to what you will and won’t invest in, is probably your best personal guide for how to invest ethically.

For instance, does it bother you to earn dividends from companies involved in mining and fossil fuels, weapons manufacturing, supply chains that aren’t signatories to sustainability or anti-slavery regulation, and alcohol, tobacco, or unethical pharmaceutical companies? Are you willing to make trade-offs and invest in a company doing harm in one area but good in another? As Da Costa says, you can’t assume “a company is one thing, good or bad.”

Whether you’re actively trading shares and avidly following financial news or just tinkering with your super investment options, the stock market will always be an ethical minefield. But with research and the knowledge of how to take control of your money and how it’s used, you can start investing more responsibly and purposefully.

Life and Shares unpicks the share market so you can make decisions you’ll be proud of. Listen now on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to spot an ototoxic leader

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Is technology destroying your workplace culture?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

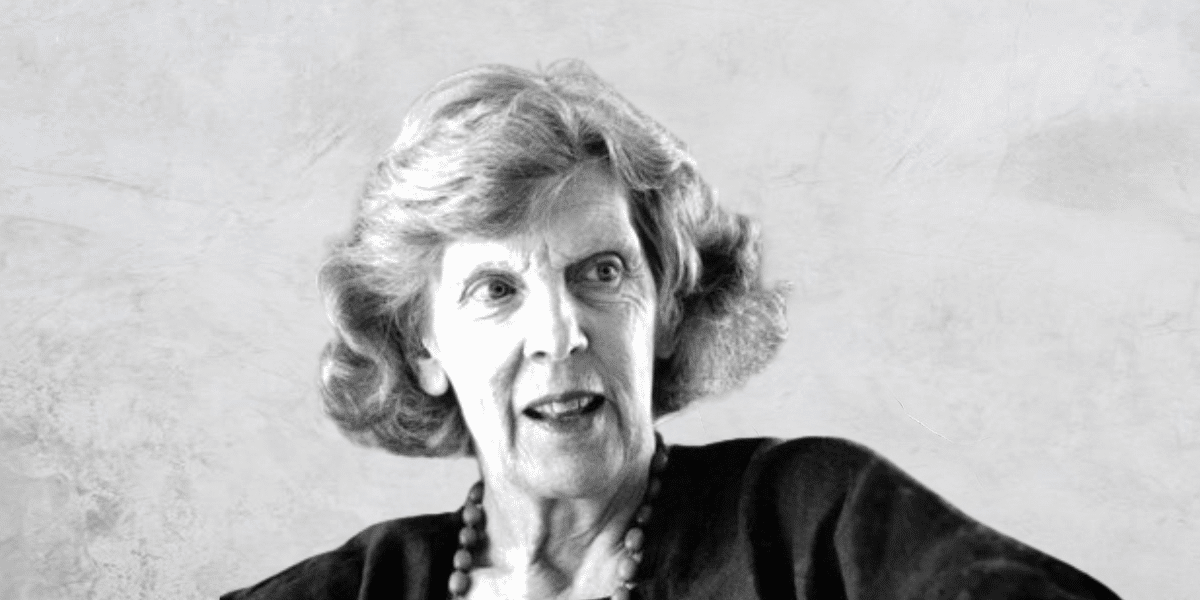

Big Thinker: Philippa Foot

Philippa Foot (1920-2010) is one of the founders of contemporary virtue ethics, reviving the dominant Aristotelian ethics in the 20th century. She introduced a genre of decision problems in philosophy as part of the analysis in debates around abortion and the doctrine of double effect.

Philippa Foot was born in England in 1920. While receiving no formal education throughout her childhood, she obtained a place at Somerville College, one of the two women’s colleges at Oxford. After receiving a degree in 1942 in politics, philosophy and economics, she briefly worked as an economist for the British Government. Besides this, she spent her life at Oxford as a lecturer, tutor, and fellow, interspersed with visiting professorships to various American colleges, including Cornell, MIT, City University of New York and University of California Los Angeles.

Virtue ethics

In the philosophical world, Philippa Foot is best known for her work repopularising virtue ethics in the 20th century. Virtue ethics defines good actions as ones that embody virtuous character traits, like courage, loyalty, or wisdom. This is distinct from deontological ethical theories which encourage us to think about the action itself and its consequences or purpose instead of the kind of person who is doing the action.

“What I believe is that there are a whole set of concepts that apply to living things and only to living things, considered in their own right. These would include, for instance, function, welfare, flourishing, interests, the good of something. And I think that all these concepts are a cluster. They belong together.”

The doctrine of double effect

Imagine you are the driver of a runaway trolley that is barrelling down the tracks. You have the option to do nothing, and let five people die, or the option to switch the tracks and kill one person.

This is Philippa Foot’s famous trolley problem. This thought experiment encourages us to think about the moral differences between actively causing death (e.g. pulling a lever to get the trolley to change tracks) and passively or indirectly causing death (doing nothing, allowing the trolley to kill five people). Utilitarians might argue that five deaths is far less desirable than one death, but many people instinctively feel that actively causing a death has a different moral weight than doing nothing.

Perhaps Foot’s most influential paper is The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of Double Effect, published in 1967. Here, she explains what is called the Doctrine of the Double Effect, which explains why some very bad actions (like killing) might be permissible because of their potentially positive outcomes. The trolley problem is one example of the doctrine of double effect, but she also uses various other cases.

“The words “double effect” refer to the two effects that an action may produce: the one aimed at, and the one foreseen but in no way desired. By “the doctrine of the double effect” I mean the thesis that it is sometimes permissible to bring about by oblique intention what one may not directly intend.”

For example, what if one person needed a large dose of a rare medicine to save their life, but that same amount of medicine could save the lives of five others who each needed less? Would we think that the “oblique intention” of a nurse who administers the medicine to one person instead of the five people is justified?

Foot finds that it would be wise to save the five people by giving them each a one-fifth dose of the medicine. However, she encourages us to interrogate why this feels different from the organ donor case, where we save five people who need organ transplants by sacrificing one person.

“My conclusion is that the distinction between direct and oblique intention plays only a quite subsidiary role in determining what we say in these cases, while the distinction between avoiding injury and bringing aid is very important indeed.”

When the trolley problem is taken to its logical conclusion, these fallacies become even more obvious. As John Hacker-Wright writes, the trolley problem “raises the question of why it seems permissible to steer a trolley aimed at five people toward one person while it seems impermissible to do something such as killing one healthy man to use his organs to save five people who will otherwise die.”

Foot has also contributed to moral philosophy with her writing on determinism and free will, reasons for action, goodness and choice, and discussions of moral beliefs and moral arguments.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

True crime media: An ethical dilemma

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture