Ethics Explainer: Longtermism

Longtermism argues that we should prioritise the interests of the vast number of people who might live in the distant future rather that the relatively few people who do live today.

Do we have a responsibility to care for the welfare of people in future generations? Given the tremendous efforts people are making to prevent dangerous climate change today, it seems that many people do feel some responsibility to consider how their actions impact those who are yet to be born.

But if you take this responsibility seriously, it could have profound implications. These implications are maximally embraced by an ethical stance called ‘longtermism,’ which argues we must consider how our actions affect the long-term future of humanity and that we should prioritise actions that will have the greatest positive impact on future generations, even if they come at a high cost today.

Longtermism is a view that emerged from the effective altruism movement, which seeks to find the best ways to make a positive impact on the world. But where effective altruism focuses on making the current or near-future world as good as it can be, longtermism takes a much broader perspective.

Billions and billions

The longtermist argument starts by asserting that the welfare of someone living a thousand years from now is no less important than the welfare of someone living today. This is similar to Peter Singer’s argument that the welfare of someone living on the other side of the world is no less ethically important than the welfare of your family, friends or local community. We might have a stronger emotional connection to those nearer to us, but we have no reason to preference their welfare over that of people more spatially or temporally removed from us.

Longtermists then urge us to consider that there will likely be many more people in the future than there are alive today. Indeed, humanity might persist for many thousands or even millions of years, perhaps even colonising other planets. This means there could be hundreds of billions of people, not to mention other sentient species or artificial intelligences that also experience pain or happiness, throughout the lifetime of the universe.

The numbers escalate quickly, so if there’s even a 0.1% chance that our species colonises the galaxy and persists for a billion years, then that means the expected number of future people could number in the hundreds of trillions.

The longtermism argument concludes that if we believe we have some responsibility to future people, and if there are many times more future people than there are people alive today, then we ought to prioritise the interests of future generations over the interests of those alive today.

This is no trivial conclusion. It implies that we should make whatever sacrifices necessary today to benefit those who might live many thousands of years in the future. This means doing everything we can to eliminate existential threats that might snuff out humanity, which would not only be a tragedy for those who die as a result of that event but also a tragedy for the many more people who were denied an opportunity to be born. It also means we should invest everything we can in developing technology and infrastructure to benefit future generations, even if that means our own welfare is diminished today.

Not without cost

Longtermism has captured the attention and support of some very wealthy and influential individuals, such as Skype co-founder Jaan Tallinn and Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz. Organisations such as 80,000 Hours also use longtermism as a framework to help guide career decisions for people looking to do the most good over their lifetime.

However, it also has its detractors, who warn about it distracting us from present and near-term suffering and threats like climate change, or accelerating the development of technologies that could end up being more harmful than beneficial, like superintelligent AI.

Even supporters of longtermism have debated its plausibility as an ethical theory. Some argue that it might promote ‘fanaticism,’ where we end up prioritising actions that have a very low chance of benefiting a very high number of people in the distant future rather than focusing on achievable actions that could reliably benefit people living today.

Others question the idea that we can reliably predict the impacts of our actions on the distant future. It might be that even our most ardent efforts today ‘wash out’ into historical insignificance only a few centuries from now and have no impact on people living a thousand or a million years hence. Thus, we ought to focus on the near-term rather than the long-term.

Longtermism is an ethical theory with real impact. It redirects our attention from those alive today to those who might live in the distant future. Some of the implications are relatively uncontroversial, such as suggesting we should work hard to prevent existential threats. But its bolder conclusions might be cold comfort for those who see suffering and injustice in the world today and would rather focus on correcting that than helping build a world for people who may or may not live a million years from now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Climate + Environment

Thought Experiment: The Last Man on Earth

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 22 DEC 2022

One surprising fact about Mike White, the creator, writer and director of HBO’s The White Lotus, is that he’s obsessed with and starred in a season of Survivor, the brutal reality TV show that pits strangers against each other in a complex game of wits and skill.

Of course White’s a Survivor junkie. The two seasons of The White Lotus – a soap opera-cum-murder mystery about a bunch of depraved rich people who exploit the surplus of expendable workers who man the titular hotel they stay at – are united by their fixation on the ways human beings outwit and outgame each other.

The White Lotus takes it as a given that human beings want things from each other, and use their (varying levels of) intelligence and power to get those things. There’s not an innocent in either season of the show, and their moral failings range from the petty and pathetic to the grand and soul-blemishing. Shane (Jack Lacy) kicks off the first season by whining and berating the hotel staff in order to get what he feels owed. Armond (Murray Bartlett), the long-suffering hotel manager, ignores one of his staff members when she goes into labour. They’re a den of thieves and miscreants, whose naked wants trump any sense of obligation to one another.

Even Tanya (Jennifer Coolidge), the only character who spans both instalments, is a hero only by virtue of being less openly murderous. Her slow realisation in the show’s second season that she is sat at the direct centre of a conspiracy motivated by greed is tragic, sure. But by the time we see her mutter her instantly iconic line about the gays who are trying to murder her, we’ve already watched her dangle her considerable wealth in front of Belinda (Natasha Rothwell) and then withdraw it, dishonestly, the moment she becomes the object of someone’s lustful affections.

These characters operate in what philosopher John Locke refers to as “the state of nature.” Locke, one of the founders of modern liberalism, believed that left to their own devices, without society, human beings live lives that are “nasty, brutish and short.” There is no sense of community, or solidarity, in the state of nature. All people want is what they want, and they live in a continuous state of never denying their desires.

So it goes in The White Lotus. The characters are nominally part of a culture – the kind of society that Locke hoped would block bad behaviour. After all, for Locke, mutual beneficence is the glue that holds us together – you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours. You refrain from killing me, so I won’t kill you either.

But Locke’s hope that the stratas and rules inherent in a society would keep its citizens ethical is blown apart by The White Lotus. Alliances form in the world of the show, sure. But these are temporary, fleeting, purely opportunistic. Belinda and Tanya don’t like each other. They need each other. Ethan (Will Sharpe) and Harper (Aubrey Plaza) might have a connection, but it’s not strong enough to hold together in the face of changing fortunes and friendships.

Importantly, so it goes across class divides. Though the show has been touted as part of a wave of modern works of art that take aim at the rich – from Parasite to The Menu – the show does not reserve its ire merely for the upper class. What sets The White Lotus apart from much “we are the 99%” cinema and television, is the way it examines the pressure that capital places on all citizens, the haves and the have nots alike.

Bitch Better Have My Money

Thorstein Veblen, the Austrian sociologist, is best known for his book The Theory Of The Leisure Class. Veblen examines the hallmarks of the elite, and finds one in common across a multitude of cultures. Simply put, Veblen says, rich people like excess. They like to spend money on things that they don’t have to spend money on.

The characters of The White Lotus are driven by this need for excess.

They want more than they could ever need. And because of this want, their lives are transformed into a series of opportunities. Wealth and power become means to garner more wealth and power.

The Di Grasso family of the second season are the perfect example of this. Some wealthy families have a “crest”, a pictorial representation of their values. The Di Grasso family’s crest would be a den of rats, ignoring their stockpile of food, and instead choosing to chew each other’s tails.

This is a family that, over generations, has learned that the world is nothing more than a series of goals, which lead to nothing but more goals. Bert (F. Murray Abraham), the family’s patriarch, has created a miniature culture that revolves around himself, in which sex is an opportunity for manipulation, wealth is an opportunity for manipulation, and love is an opportunity for manipulation.

And his brood, desperate to emulate him, and attract his affection – if only to get ahead themselves – have followed in his lead, even if they don’t realise it. For this family, nothing and no-one ever sits as they lay – nothing is discrete, or for itself. Bert might be viewed by the other characters as a mostly impotent, harmless old man, a wannabe peacemaker who has lost touch. But he is as single-minded as ever, even in his old age, and he spends the second season analysing the weakness of others, and then using those weaknesses for his own gain.

This opportunistic streak extends to the entire solar system of vapid and cruel characters in the second season. Tanya is exploited for her deep loneliness, and her own desire to exploit others stops her from realising the danger she’s in until too late. Lucia and Mia, the strongest-hearted characters of the second season, all things told, come into themselves as creatures who know how to get what they want, and what they have to do to get those things. No honour among thieves, and no values but the shifting goalpost of immorality, which reduces the world to a series of people to fuck over, and be fucked over by.

And for what? The striking thing about The White Lotus is how little this all means. All that suffering, all that exploitation, and the only prize at the end is a consolation prize. It’s not for nothing that each season’s murder turns out to be a whimper, rather than a bang. In the first season, Armond dies after a feces-based prank goes pathetically wrong, running himself into a blade. And in the second season, Tanya manages to (somewhat) extricate herself from a conspiracy to murder her, gun blazing, only to die thanks to an ungainly fall.

Checks out. If what marks the upper class is their fixation on the pointless, the too-much, then of course their fates are pointless too. Even those who win don’t win much. And those who lose – well, they lose hard, falling backwards into the den of conniving players that they have tried and failed to connive.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Barbie and what it means to be human

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The ethical honey trap of nostalgia

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

How to give your new year’s resolutions more meaning

How to give your new year’s resolutions more meaning

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY John Neil 21 DEC 2022

It’s that time of year again. For many of us the New Year is a time to make our annual resolutions.

For others it’s a time to briefly toy with the idea of making a resolution or two but never commit. And for others, depending on how badly the previous evening’s events transpired, the New Year’s Day hangover inspires at least one resolution – to never ever drink again.

Unfortunately, the majority of people don’t stick to their resolutions. Only 4-10% of people report following through on the resolutions they set at the beginning of the year (I wonder whether this figure includes those people that sarcastically claim that they have only one New Year resolution – to not make any New Year’s resolutions?).

The majority of resolutions fail because, well, we’re human beings. There are at least three factors behind this:

1. We overestimate the power of ‘will power.’ Often linked to adjacent concepts like resilience and impulse inhibition, the long-standing belief in psychology is that will power is a finite resource and people have varying reservoirs of it to draw on. The belief was that by bolstering our will power we’re better able to attain our goals and, by implication, those that don’t achieve their goals lack willpower. Unfortunately, it’s more complicated than that. Our ability to maintain choices and attain goals is as much about situational context, genetics, and socio-economic standing as it is about individual psychological traits.

2. As a result, any significant behaviour change requires long standing practice, environmental changes and thoughtfully designed behavioural cues in order to create pathways of reinforcement in order to form new habits. In short, even the simplest resolutions require habitual practice.

3. Most resolutions are goal focussed – stop smoking, lose weight – and for that reason they take on an instrumental importance, meaning they focus exclusively on achieving an end state or outcome. With the high level of difficulty in achieving these outcomes resolutions can become self-defeating – the end becomes the goal rather than a focus on the motivating reason that inspired the goal.

That’s not to say that New Year’s resolutions are a bad thing. We are hard-wired to demarcate life into phases. Birthdays, seasons, events, and the change of year are all relatively arbitrary events but are full of symbolic significance. They are moments that matter because we invest these occasions with meaning.

New Year’s resolutions at their best can provide a much-needed pause in the busyness of life to reflect and reassess what’s important to us.

So, as you pause and reflect on the year ahead, consider taking a different path when thinking about setting resolutions. Rather than listing goals, think instead about the qualities you’d like to cultivate in the year ahead. What qualities for you express the best aspects of a life well lived? Which of those would you choose to have more of in your life?

Known as virtues – those behaviours, skills or mindsets that are worthy to be regarded as features of living a good life. Wisdom, justice, and courage were on Aristotle’s shortlist.

Rather than setting goals like read more books or spend less time on my phone – think instead of the quality you are calling more of into your world – like being curious.

There are no limits or targets to being curious, there’s simply a conscious reflection which may lead to some different choices or new experiences.

Curiosity might lead you to pick up a book rather than slump on the couch in front of Netflix or it may prompt you to choose an interesting documentary about a topic you always wanted to know more on.

Being curious this year might also benefit your relationships. Being curious involves behaviours like asking more questions, seeking out different points of views and perspectives and being more open to opinions and beliefs that are different to the ones you hold. Practicing this virtue may lead to new and unexpected connections, making new friendships or forging even stronger relationships. It may even reduce conflict by helping you to be less triggered when confronted with views that are contrary to our own.

Being curious may also help with your lifestyle and eating habits. Rather than resolving to lose weight, be curious about trying different foods which may inspire some different meal choices from those that you might already know. By being curious you may be intrigued to occasionally switch out some of your habitual choices by actively seeking out different or healthier alternatives.

However, there’s no guarantee that being curious might not also lead you to consume a wider variety of chocolate or spend even more time on your phone as you may seek out even more information and distractions. That’s the challenge with cultivating qualities or virtues; you’ll need practical wisdom, as Aristotle calls it. It’s about finding the best balance between the virtue and its corresponding vices.

Rather than focus on resolutions as goals and outcomes – often with arbitrary measures of success like read more, rest more, learn another language – focus instead on the ‘why’ behind the quality you are wanting to cultivate. Research shows that being purposive and intentional helps people maintain their motivation and achieve the goals they set.

As you reflect on the year ahead take some time to think about those qualities you could do with a little more of. In fact, why wait for the New Year? I’m going to start today by practicing more gratitude. There’s no time like the present.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Want men to stop hitting women? Stop talking about “real men”

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

Why Australian billionaires must think “less about the size of their yard” and more about philanthropy

Why Australian billionaires must think “less about the size of their yard” and more about philanthropy

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Emma Elsworthy The Ethics Alliance 15 DEC 2022

Australians donated a record $1.16 billion last year but our mega-rich are laggards on the world stage for giving. Assistant Minister for Competition, Charities and Treasury, Andrew Leigh calls for Aussie billionaires to think less about their backyard size and more about their philanthropy.

An Australian-first report from the Centre for Social Impact (CSI) delved into who was giving and how much in 2021, finding a measly 2% of the top earners in the country gave a higher proportion of their income than the everyday Australian.

That’s despite the wealthiest 200 people owning 3.8% of the country’s wealth – some $555 billion – with the top five owning $143.28 billion alone. That means Australia’s giving total is 0.81% of the country’s GDP, behind Canada at 1%, half of New Zealand’s at 1.84%, and less than a third of the US’s, at 2.1%.

Indeed in the US, 90% of people earning over $1 million make tax-deductible donations, compared to only 55% of Australians earning the same amount. Why? The wealthy in Australia just aren’t thinking about giving enough, Leigh tells The Ethics Centre.

“I want the main topic of conversation among Australia’s successful business leaders not to be the size of your yard, but the impact that you’re making with your philanthropy – where your giving is going, how it’s changing lives, how you’re managing to have a transformative impact beyond the business,” Leigh says.

“I’m reaching out to many business leaders who are pioneers in terms of corporate philanthropy, and just asking them a simple question: ‘If you were in my shoes, how would you look to maximise impact giving in Australia?’”

And as the country emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic into a time of economic uncertainty with the cost of living surging, Australia’s charity sector faces new and frightening challenges in providing care to our most vulnerable.

Put simply, “there are more people to help and fewer people who are giving,” Leigh says.

Four out of five community sector charities struggled with an increased demand for services during the pandemic, the CSI report found. About half (54.9%) of aged care charities and income support charities (48%) made a loss or a small surplus in 2021 (whereas 44.2% of religious charities and 41% of emergency relief charities made a surplus).

“Our goal of doubling philanthropy by 2030 really is one that sits outside the business cycle. We want to permanently increase the level of generosity of Australians, not because we want government to step back, but because we think these challenges are so busy that government can’t do it alone,” he says.

And there’s plenty of reason for optimism, Leigh says, amid a growing list of billionaires parting with their wealth in the name of civic responsibility. Last December, Australia’s richest man and Atlassian co-founder Mike Cannon-Brookes and his wife Annie Cannon-Brookes vowed to invest $1.5 billion of their personal wealth to financial and philanthropic ventures aimed at fighting climate change.

Overseas, Bill Gates has pledged to part with “virtually all” of his wealth, while Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg made a 2015 pledge to donate 99% of his Facebook shares to charity. In September, Patagonia’s founder donated his entire company to the fight against climate change.

“I think it’s really apparent that a lot of the successful technology entrepreneurs in Australia have the mindset that they don’t want to leave most of their wealth to their kids. They want to give it back to the community,” Leigh says.

So how can Australian businesses emulate this groundswell to give? Consecutive lockdowns saw a reduction in corporate volunteering and pro bono services, replaced by corporate investments of products and cash. Leigh says this is a valuable opportunity to evolve our concept of giving into “impact giving”.

“We’re actually seeing quite a shift in corporate volunteering away from the sort of ‘let’s go and paint a fence on Friday’, to ‘let’s match up our skills to what the sector needs’ – more planned and more intentional corporate volunteering,” he says.

Leigh continues there is an abundance of unused corporate volunteering hours in the economy, and the MP has been meeting with businesses and the philanthropic community to discuss the smartest way to give back – the key to this, he says, is thinking about one’s “comparative advantage”, the special sauce that the next firm doesn’t have.

“The free training that’s being provided to community organisations by Canva, for example, allows designers from disadvantaged backgrounds to learn IT and design skills and get better earnings as a result. That’s something that only Canva can do.”

Leigh says for him it comes down to “putting the S back into ESG” – for Australian corporations and the billionaires that head them up to think deeply about the value of their social impact on Australia’s most needy.

“Let’s encourage a race to the top in supporting community organisations,” Leigh says.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Our economy needs Australians to trust more. How should we do it?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why we can’t learn from our past (and shouldn’t try to)

BY Emma Elsworthy

Before joining Crikey in 2021 as a journalist and newsletter editor, Emma was a breaking news reporter in the ABC’s Sydney newsroom, a journalist for BBC Australia, and a journalist within Fairfax Media’s regional network. She was part of a team awarded a Walkley for coverage of the 2019-2020 bushfire crisis, and won the Australian Press Council prize in 2013.

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

Why we can’t learn from our past (and shouldn't try to)

Why we can’t learn from our past (and shouldn’t try to)

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Emma Elsworthy 12 DEC 2022

Businesses make up around two-thirds of psychic Denise Litchfield’s readings. The Australian’s clairvoyant method “looks into the energy around their business and sees if a project needs tweaking”.

For instance, she tells journalist and author Gary Nunn, she once spotted an error in an email sequence that purportedly saved a person “thousands”.

Nunn’s book, The Psychic Tests, delves into the multi-billion dollar industry of predicting the future using what we know, and why humans are so keen to do so. A healthy sceptic, Nunn was astounded to learn psychics are called upon by everyone from your average Joe or Jane right up to CEOs and even presidents.

Former BBY chairman Glenn Rosewall, who oversaw the largest failure of an Australian stockbroking firm since the financial crisis, allegedly asked a psychic advice for wealth clues for four years, including insights about the stockbroking firm’s astrological charts, hiring staff, and budgets.

Even former US president Ronald Reagan and wife Nancy called upon astrology to guide their schedules in what was called “the most closely guarded domestic secret of the Reagan White House”, though it was not used in forming policies or decision-making, Reagan assured the public.

Cash-hungry mysticism aside, the powerful seeking predictions speaks to a deeply-held human emotion to prepare oneself for the future’s challenges. But as we enter into an era with several of what Adam Tooze dubs overlapping “tipping points”, we may find no amount of looking back and learning from our mistakes will help.

Tooze, a British historian and Director of the European Institute, told The Festival of Dangerous Ideas that there is “a fundamental paradox at work” – that is, “a desire to work from history, the sense that we can go nowhere else for inspiration, but to our past experience” to equip ourselves for what’s coming.

But, Tooze continues, “this is the issue of tipping points – that fundamentally oppressive sense that we live under in the current moment – that we are years, weeks, possibly hours away from some transformative event that is going to change the world, like the pandemic did to us in a matter of days in early 2020”.

Fast-forward to now and still-deadly pandemic, a rapidly heating planet, a war in Ukraine, and several key nations including the US and EU careening towards a recession next year doesn’t exactly make building a plan for the future straightforward. But that’s exactly what Treasurer Jim Chalmers did when he crafted the Albanese government’s austere first budget last month.

While in opposition, Chalmers told the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry that we have just lived through “the weakest decade of growth since the 1930s, stagnant business investment, productivity and wages, growing debt,” while simultaneously facing uncertainty about “the consequences of floods and war, when interest rates will rise, the challenges of falling real wages and skills shortages – all against the backdrop of a lingering pandemic”.

This, Tooze says, cuts to the bone of the problem of trying to predict the “radical future”. “What would it actually mean to craft policy which addressed the radical novelty, which our best guess suggests what the future holds in store?” he asks.

Sure, Tooze continues, we “entrust this task to experts, it could be their job to prepare endlessly for this radical future that will be radically different”. But, he says, it’s an incredibly oppressive burden that can “destabilise your sense of normality, it tends towards the apocalyptic, it tends towards almost a fantastical notion of the future”.

“And if it’s the difference between the past and the present, that opens up the space of history, then learning from history is going to be an inherently doomed exercise from the very beginning,” Tooze says.

Perhaps it is up to our private sector to save the world. Elon Musk might be making headlines for his disruptive leadership at Twitter (including an exodus of three-quarters of the staff), but Tesla remains one of the world’s most valuable companies in the world and the number one most valuable automaker, with a market capitalisation of more than US$840 billion.

How? By breaking new ground, rather than looking back, in accelerating the world’s transition to sustainable energy with electric cars, solar and integrated renewable energy solutions for homes and businesses, taking strides to slash the world’s automotive emissions (which make up 10% of Australia’s total) and cashing in along the way.

“After all, one person’s unsolved issue is another person’s business opportunity,” as Tooze put it.

But is appointing brainy futurist technocrats like Musk or successful Wall Street billionaires like the newly-minted British PM Rishi Sunak the solution to an unclear future? Tooze says it brings up a whole lot of other questions – namely whose interests would they really be serving, and how could we be sure they were drawing “the right inferences” from the past?

“The financial interests which are doing that job for them really have free rein for those elites, we would need them to be acting in a vacuum of social power, we would need them to be free to enact as it were, the technocratic logic, the derivations of the past, the present and the future … that we want to see them doing,” Tooze says.

If there’s one thing we can take from the past with confidence, he continues, it’s English economist John Maynard Keynes telling the BBC back in 1943 that “anything we can actually do, we can afford” – we are “immeasurably richer than our predecessors”, Maynard Keynes asked. So why does “sophistry, some fallacy, govern our collective action”?

In other words, Tooze says, we have the money and we have the brains to solve our challenges. Reimagining the system may remain a lofty goal for idealists, but the self-determining reality is that it comes down to the individual. “The problem is actually concerning ourselves getting our act together to do the things,” he says.

We have the money and we have the brains to solve our challenges. Reimagining the system may remain a lofty goal for idealists, but the self-determining reality is that it comes down to the individual.

“We will make shifts, we will look for compromises, we will find hustles. We’ll differ, we’ll react, we’ll adapt, we’ll crisis fight, we will ameliorate, and we will slouch, not towards utopia or disaster, it seems to me, but potentially, possibly, towards coping,” Tooze concludes.

“The central question that I think we need to focus on is this issue of timing. Is it going to be enough? Is it going to be fast enough? … Will we be able to keep pace with this reality that we face and that preoccupies and concerns us all?”

Tune into Adam Tooze’s FODI discussion, F=fail

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

United Airlines shows it’s time to reframe the conversation about ethics

Reports

Business + Leadership

Productivity and Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Between frenzy and despair: navigating our new political era

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

An ethical dilemma for accountants

BY Emma Elsworthy

Before joining Crikey in 2021 as a journalist and newsletter editor, Emma was a breaking news reporter in the ABC’s Sydney newsroom, a journalist for BBC Australia, and a journalist within Fairfax Media’s regional network. She was part of a team awarded a Walkley for coverage of the 2019-2020 bushfire crisis, and won the Australian Press Council prize in 2013.

“I’m sorry *if* I offended you”: How to apologise better in an emotionally avoidant world

“I’m sorry *if* I offended you”: How to apologise better in an emotionally avoidant world

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Sarah Wilson 8 DEC 2022

I’ve been wondering if we need to have a better look at the way we say sorry.

We live in a highly binary and individualistic world that struggles to repent well. Yet we are increasingly aware of – and flummoxed by – bad faith efforts at the gesture.

Witness the fallout from former Prime Minister Scott Morrisons’ baffling response speech to being censured last week in which he refused to apologise to the nation. I reckon we ache to do better; we want true healing.

We could start with looking at the way we so often insist on whacking the Almighty Absolving Qualifier “if” when we issue an “I’m sorry”. I’m sorry if you’re offended/upset/angry. We go and plug one in where a perfectly good “that” would do a far better job.

But an “if” negates any repentant intent. Actually, worse. It gaslights. It puts up for dispute whether the hurt or offence is actually being felt and whether it is legitimate. Attention switches to the victim’s authenticity and their right to feel injured. Did you actually get hurt? Hmmm….

Things get even more disconcerting when the quasi-apologiser thinks they have done something gallant with their qualified “I’m sorry”. And will gaslight you again if you pull them up on the flimsiness of it. What, so you can’t even accept an apology!

I had a rich, senior businessmen do the if-sorry job on me recently. “I’m sorry if you’re angry,” he said in a really rather small human way. Rather than standing there miffed, I replied, “Great! Yep, you definitely fucked up. And so I’m definitely and rightly angry. Now that’s established, sure, I’ll take on that you’d like to repent.”

I heard a well-known doctor on the radio the other morning very consciously (it seemed) drop the if from the equation when he had to apologise for making remarks about a minority group (in error) in a previous broadcast. “I’m sorry I said those things. I was wrong. I’m not going to justify myself. There are no excuses. I was in the wrong,” he said. It was a good, textbook apology and he probably wouldn’t land in trouble for it.

But, and it immediately begs, is that the point of an apology?

For the wrongdoer to stay out of trouble? For them to neatly right a wrong by going through a small moment of awkward, vulnerable exposure?

What about the victim? Where do they sit in apologies?

I recall listening to a radio discussion where all this was dissected. The point that grabbed me at the time was this: In our culture, the responsibility of ensuring that an apology is effective in bringing closure to a conflict mostly rests on the victim, the person being apologised to. No matter the calibre of the apology, it’s up to the person who has been wronged to be all “that’s ok, we’re sweet” about things. They are effectively responsible for making the perpetrator feel OK in their awkward vulnerable moment. (And to keep the pain shortlived.)

And so a successful apology rests in the victim’s readiness to forgive.

Which is all the wrong way around. At an individual-to-individual level it’s cheap grace. The wrongdoer gets absolved with so little accountability involved.

At a macro level, say with injuries like racism or sexism, we can see the setup is about a minority class forgiving, or bowing once again, to the powerful.

I managed to find the expert who’d led the discussion – Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, a New York-based Rabbi and scholar who’s written a book on the matter, On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World, a title that says it all, right?

Ruttenberg argues we are doing apologies inadequately and in a way that fails to repair the damage done precisely because we privilege forgiveness over repentance.

So how to apologise like you mean it

Drawing on the 12th Century philosopher Maimonides, Ruttenberg sets out five steps to a proper apology.

1. Confession

The wrongdoer fully owns that they did something wrong. There’s to be no blabbing of great intentions, or how “circumstances” conspired; no “if” qualifiers. You did harm, own it! Ideally, she says, the confession is done publicly.

2. Start to Change

Next, you the work to educate yourself, get therapy etc. Like, demonstrate you’re in the process of shifting your ways. You’re talk and trousers!

3. Make amends

But do so with the victim’s needs in mind. What would make them feel like some kind of repair was happening? Cash? Donate to a charity they care about?

4. OK, now we get to the apology!

The point of having the apology sitting right down at Step 4 is so that by the time the words “I’m sorry” are uttered, we, as the perpetrator, are engaged and own things. The responsibility is firmly with us, not the victim. By this late stage in the repenting process we are alive to how the victim felt and genuinely want them to feel seen. It’s not a ticking of a box kinda thing. Plus, we’ve taken the responsibility for bringing about closure, or healing, out of the victim’s hands.

5. Don’t do it again

OK, so this is a critical final step. But there’s a much better chance the injury won’t be repeated if the person who did the harm has complete the preceding four steps, according to Ruttenberg and Maimonides.

Does forgiveness have to happen?

I went and read some related essays by Rabbi Ruttenberg just now. The other point that she makes is that whether or not the victim forgives the perpetrator is moot. When you apologise like you mean it (as per the five steps), I guestimate that 90 per cent of the healing required for closure has been done by the perpetrator. And it happens regardless of whether the harmed party forgives, because the harm-doer sat in the issue and committed to change. The spiritual or emotional or psychological shift has already occurred.

I should think that, looking at it from a victim-centric perspective, this opened space allows the harmed party to feel more comfortable to forgive, should they choose to.

It’s a win-win, regardless of whether the aggrieved waves the forgiveness stick.

(The Rabbi notes that in Judaism, as opposed to Christianity, there is no compulsion for the harmed party to forgive.)

What *if* we offend or harm unintentionally?

I was presented with the above ethical quandary while writing this. Someone on social media commented that she’d wanted to approach me recently but felt she couldn’t because she had two kids in tow at the time. She figured I’d judge her for being a “procreator” given my climate activism work and anti-consumption stance. It was an unfortunate assumption. I had only last week written about how bringing population growth into the climate crisis blame-fest is wrong, ethically and factually (it’s not how many we are, it’s how we live).

Of course, her self-conscious pain was real. But did I need to repent if I’d done nothing wrong, and certainly not intentionally (indeed, I’d not acted, in bad faith or otherwise).

I decided there was still a very good opportunity to switch out an “if” for a “that”. I replied: “I’m sorry that you felt….”. And I was. I didn’t want her to have that impression of judgement from another, nor to feel so self-conscious. I was sorry in the broad sense of feeling bad for her. Feeling sorry can be a sense of tapping into a collective regret for the way things are, even if you are not directly responsible.

The real opportunity here was to take on responsibility for healing any hurt, and to speed it up. If I’d listed out and justified why this person was mistaken (wrong) in feeling as she did, I’d have also missed an opportunity to be raw and open to the broader pain of the human condition.

Doing good apology is essentially an act in correctly apportioning the tasks required to get the outcome that we are all after, which, for most adults, is growth, intimacy and expansion. Ruttenberg makes the point that some indigenous cultures work to this (more mature) style of repentance (as opposed to cheap grace), as well as various radical restorative justice movements. I note that the authors and elders who contributed to the Uluru Statement from the Heart often remind us that the document is an invitation to all Australians to grow into our next era.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

BY Sarah Wilson

Sarah Wilson is a multi-New York Times and Amazon best-selling author, podcaster, international keynote speaker, philanthropist and climate change advisor. Sarah is known globally for founding the I Quit Sugar movement – a digital wellness program and 13 award-winning books that sell in 52 countries – which saw millions around the world transform their health. In 2022 Sarah sold the business and gave everything to charity. Sarah is an experienced journalist and broadcaster. She was previously the editor of Cosmopolitan Australia at age 29; host of Masterchef Australia; was a News Corp journalist and columnist; and has hosted ABC’s Compass, Ten’s The Project and more. She is also a regular commentator on news and current affairs programs in Australia, the US and UK.

Ethics on your bookshelf

Ever wondered what we’re reading over at The Ethics Centre? Well here’s your chance! We asked some of our thought leaders for their best ethical reads this year.

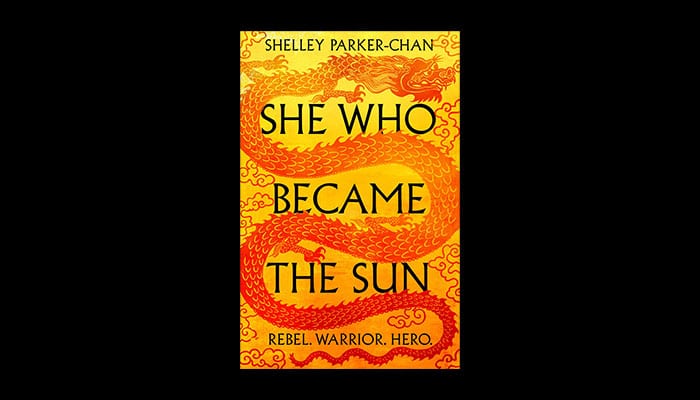

She Who Became the Sun by Shelley Parker-Chan

To take a break from reading so much non-fiction in prep for the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, our FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey returns to her first love – fantasy. This re-imagining of the rise to power of the Hongwu Emperor in 14th century China combines gender, rebellion, power and faith in a powerful and fun novel.

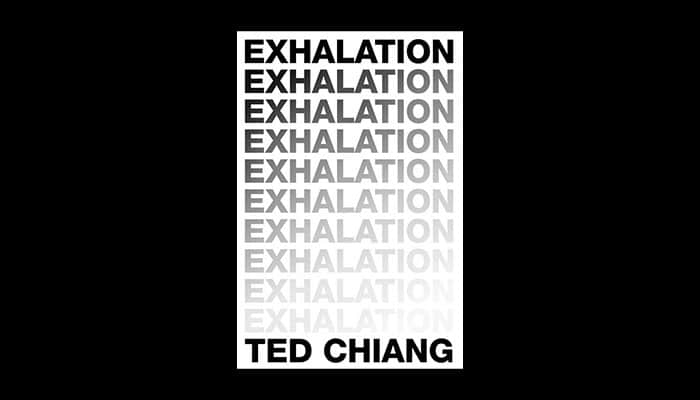

Exhalation by Ted Chiang

Our Senior Philosopher, Dr Tim Dean recommends this startling collection of science-fiction short stories, which is as philosophically stimulating as it is deeply engaging. Chiang is one of those precious few writers who genuinely groks both science and philosophy, and does both of them justice without compromising creativity or narrative. His ‘what if’ worlds are plausible and provocative, exploring themes like freedom, fate, existentialism, memory and moral responsibility.

How to be Perfect by Michael Schur

Whether you’re a philosophy buff or you have no idea who Plato is, our Youth Coordinator and philosopher, Daniel Finlay says Schur’s writing will have you laughing, learning, thinking and reflecting all at once. This is an engaging and entertaining introduction into lots of aspects of moral philosophy, with plenty of anecdotes and comparisons to keep you from feeling like you’re in school.

Stolen Focus by Johann Hari

Making decisions we can be proud of means that sometimes we need to do things we don’t want to or have the patience for. After reading Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus, our Director of the Ethics Alliance and the BFO, Cris Parker realised how easily we can be distracted, how desperately we can crave reward and that how the technology we take for granted is contributing to this. Stolen Focus identifies the ways we can lose our capacity to make choices and provides techniques to change that. The challenge for us now is actually implementing them!

The March of Folly by Barbara Tuchman

Our Executive Director, Dr Simon Longstaff says in exploring some of the worst decisions made in human history, The March of Folly reveals the root cause that lies in one of the great enemies of ethics – the baleful effects of unthinking custom. In this historical survey, Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Barbara W. Tuchman grapples with the pervasive presence through the ages, of failure, mismanagement, and delusion in government.

John Ashbery, Collected Poems 1991-2000

Philosopher and Ethics Centre Fellow, Joseph Earp doesn’t think that ethical education is complete without poetry, nor is poetry complete without John Ashbery. Ashbery is a strange, elliptical writer, who fosters attention, and shows us the rewards of paying attention. Which is where the ethics of it all comes in – what is the ethical life, if not one where we pay attention?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Society + Culture

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Philippa Foot

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We are pitching for your pledge

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 29 NOV 2022

Religious holidays like Christmas are not just for believers. They involve rituals and customs that can help reinforce social bonds and bring people together, no matter what their beliefs.

What is Christmas all about? On the one hand, it’s a traditional Christian religious holiday that celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ, the son of God. On the other hand, it’s a commercial frenzy, where people battle crowds in vast shopping centres blanketed in themed decorations to buy disposable trinkets that are destined to be handed over to disappointed relatives straining, but failing, to smile with their eyes.

Either way, if one is not overly devout or materialistic, Christmas might seem like something worth giving a miss. And if you’ve lost your religion entirely, it might seem appropriate to dispense with Christmas traditions.

The same applies for major holidays celebrated by other religions. If you do abandon Christmas – or Hanukkah, Diwali, Ramadan, etc – you’ll be missing out on an opportunity to participate in a ritualistic practice that is about more than the scriptures suggest, and certainly more than the themed commercial advertising represents.

This is because religious holidays like Christmas are not what they seem. They are not fundamentally about spirituality, as they purport to be. They’re certainly not about boosting economic activity, even if that’s what they’ve become. Rather, they’re about bringing people together to create shared meaning.

Anyone can benefit from this effect if they participate in the rituals and traditions of a religious holiday, including people of that religion who are no longer believers, as well as those outside of the culture who are welcomed in.

Do you believe in Santa Claus?

Religiosity is in decline in most countries around the globe, Australia included. In fact, Australia is in the top five nations in the world in terms of the proportion of self-declared atheists. And “no religion” is the fastest growing group, jumping from less than 1% of the population in 1966 to 38% in the latest Census figures from 2021. These numbers are even higher for young people, which suggests the move away from religion will continue into the future.

For the ‘new atheists,’ this looks like a good thing. Thinkers such as Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens and Sam Harris famously argued that religion is dangerous force that spreads unscientific beliefs and perpetuates social divisions. They have urged people to drop their spiritual beliefs and embrace a secular rational lifestyle.

There are merits to their arguments, but their bundling of religions’ problematic metaphysics with the traditions and rituals they promote overlooks that the two are not necessarily connected: one need not believe that three wise men tracked a mystical light in the sky to the birthplace of Jesus so they could give him gold, frankincense and myrrh in order to hand over a present to a loved one. It’s like how we already agree that one need not believe in Santa Claus in order to stuff the odd stocking.

The other thing the scorched Earth version of atheism overlooks is that the decline of religiosity has corresponded with an increase in social fragmentation in the modern world. Many people feel a sense of social isolation and disconnection from those around them, even if they live in the midst of a metropolis, which is contributing to the growing crisis in mental health.

This is not a new phenomenon. A similar pattern was observed by sociologists such as Émile Durkheim and Ferdinand Tönnies in the late 19th century. They attributed it to the rise of individualism over community as modern societies expanded following the industrial revolution. The erosion of community meant that individuals were left to seek their own meaning and purpose in life, as well as forge their own social connections.

This lean towards individualism affords each person some freedom in choosing what is meaningful for them, but it also involves a lot of work; it’s no mean feat to single-handedly create a grand structure to make sense of the world, to inform what we should value and what morals we should abide by. And there are many forces that are only too happy to sell their own vision to the individual, including all manner of pseudo-spiritual causes, conspiracy theories and self-help gurus. But the strongest force today is capitalism, which sells a vision of work and consumption that is superficially appealing but which many find to be ultimately hollow and unfulfilling.

One of the mechanisms sociologists identified that helped to ameliorate the individualistic tendency towards social disconnection and isolation was religion. But it wasn’t the spiritual dimensions of religion that did the most work, it was the rituals and traditions that brought people together to reinforce social connections and create shared meaning.

Rituals like gathering for an annual feast with family, which signifies a break from everyday consumption and gives us an opportunity to show care and respect for others as we feed them. Or gift-giving, which motivates us to think carefully about the most important people in our lives – who they are, what they care about, what they lack – and encourages us to find or make something, or use our wealth, to bring them joy. Even singing carols has an effect. The act of singing in unison is a potent way of bonding with those around us, and even the habit of complaining about our most hated Christmas tunes can bring people together.

Come together

There are many more rituals involved with Christmas, and many analogous rituals associated with the festivals of other religions.

While their surface details and spiritual justifications may differ, at their heart they’re all about one thing: bringing us closer together. They’re a form of social glue that is arguably much needed in today’s world.

While the differences between traditions can be a source of division, and the rise of multiculturalism and sensitivity towards other cultures can be a source of reservation when it comes to participating in rituals that are not ‘our own,’ we still have a lot to gain by continuing to practise festive rituals, even if we no longer subscribe to their supernatural pretexts. We also have a lot to offer if we welcome those of other cultural and religious traditions to share our rituals, and if we remain open to learn from and share in theirs.

On the surface, Christmas looks like it’s about spirituality or like it’s been co-opted by the market. But deep down, it’s one of many religious festivals that we can draw on to enrich our lives, ground ourselves in our family and community, and a way to create meaningful experiences with others to help us all live a good life.

Join Dr Tim Dean for The Ethics of Holidays on the 8th of December at 6:30pm. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Agape

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Is your workplace turning into a cult?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Amal Awad 25 NOV 2022

While ratings systems may encourage good behaviour on the part of the provider and recipient, it’s a hungry business model that is both anxiety-inducing and untrustworthy.

In Seth MacFarlane’s off-beat homage to Star Trek, The Orville, the increasingly earnest show becomes a series of cautionary tales. In one episode, Majority Rules, MacFarlane signals the dangers of the real world mirroring the online one. The crew of the Orville attempt to rescue a couple of imprisoned anthropologists from an Earth-like planet, where justice is meted out based on a system of public votes. In deep trouble, the public will determine their innocence with a ‘thumbs-up’ or ‘thumbs-down’.

I didn’t love the show, but Majority Rules lingers in my mind because even though determining a person’s freedom by public votes seems ludicrous, isn’t this happening daily online already, to varying degrees of severity?

There is, of course, the modern-day equivalent of the stocks. But instead of passers-by throwing fruit and jeering, people find ways to do it in 140 characters or less, hashtags optional.

But seemingly more innocuous judgments are made elsewhere, and they affect how we live, work and engage with others. When you consider the services and experiences that make up your daily life, how many of them involve ratings? Businesses rely on reviews from Google, Yelp, Trip Advisor and so on, as do we as consumers.

And of course, your transport and food delivery apps depend on them. The meal you ordered through a delivery app arrived soggy and not at all like it looked in the photo? Blame the rider who didn’t pedal fast enough, bypass the restaurant. Your food was terrible and the low-paid delivery rider is the low-hanging fruit. They get one star. Hated the music your Uber driver was playing? Give them a poor rating – though you should know, with Uber they can give you one back.

In November this year, it was reported that a study from the University of Bristol and University of Oxford found seven out of 10 gig economy workers were in a constant state of worry about negative reviews and the impact they would have on their livelihood. The lead author and sociologist, Dr Alex Wood, Lecturer in Human Resource Management and Future of Work at Bristol, noted: “It was shocking how workers expressed continuous worry about the potential consequences of receiving a single bad rating from an unfair or malevolent client, and how this could leave them unable to continue making a living.”

This anxiety over ratings is understandable. It’s not that criticism is a fresh concept (in the arts world, we are constantly subjected to review). But in the gig economy, not only can customer-generated scores sink or boost workers’ reputations, they culminate in an advertising and rewards system. The better you’re rated, the more accolades you receive, often in the form of badges that signal that you are a superstar. It’s a clever marketing tactic, because as consumers we follow the high ratings, but it’s also a way to encourage good behaviour all round because often apps rate both provider and consumer.

Ratings systems are surveillance and compliance systems, a very public message board, which mostly empower the consumer. But these ratings can also be used to falsely entice us.

Years ago, I employed the services of transcribers on a gig website. Despite having a catchy price point, the cost of the service, quite rightly, rose according to the needs of the job. And yet, the work was not done to a reasonable standard. I chose not to leave negative reviews, but the service providers pushed me to so I relented and gave them four out of five stars. I understood: they were trying to make a living. Then they sent me messages asking (borderline haranguing) me to change my review to a perfect score.

They were jockeying for work but cutting corners then demanding positive reviews. I gave in, feeling guilty, knowing that they were boosting their reliability to secure more work they didn’t seem capable of actually completing.

Meanwhile, try leaving an honest review on AirBnB, and you will understand why so many places are given rave reviews but fall short. No one wants to tell the truth when they are being judged back.

What a circular mess.

How can we trust ratings systems like this? Can scores be trusted given how freely, and sometimes anonymously, they can be applied? Meanwhile, even though ratings systems can be a useful barometer of a service provider’s reliability or competence, they may also be completely false endorsements. Increasingly, we are being warned about fake reviews, which set out to uplift or destroy a business. It pays to read comments carefully rather than rely on the rating itself.

We are increasingly being taught to assess every service or experience, and it is not a thorough, or necessarily fair, feedback system for either party to a transaction.

No longer are workers simply ‘freelancers’ if they are self-employed; in a world of food delivery and transport services, of competitive freelance websites like Fiverr and Upwork, everyday commerce has been twisted and turned into a thriving, cut-throat marketplace. One where workers’ rights are blurred, where bad reviews are doled out hastily, spitefully or truthfully, but without any oversight to ascertain their veracity.

The gig economy has long been examined for its flaws. Despite the opportunities and ease-of-access a casualised, sharing economy creates, with it comes crushing downsides: the dilution of employee rights, the lowering of fees just to secure the gig – and with that, quite likely, standards. Skilled workers get edged out of industries when they are undercut by less experienced people willing to do the job at a fraction of the actual cost.

Ratings systems encourage good behaviour but we are becoming hyper vigilant and more critical in the process. While business is booming, this explosion in feedback is not making us better workers or customers. Time will tell if this is, ultimately, bad for business. We already know that it is taking its toll on providers.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Women must uphold the right to defy their doctor’s orders

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Georgia Fagan 23 NOV 2022

Donald Trump has announced his second run for presidency in 2024. With a reputation for both passive and active violence, and a disregard for democratic integrity, the prospect of another Trump presidency is feared by many. But for others, his re-election would mark the promising return of a strong, capable leader. How do we begin to make sense of these contemporary communities which seem to either fear or revere their elected leaders? And are there ways such polarised receptions can ever be avoided?

Historian Ruth Ben-Ghiat knows just how Trump, operates. He’s following the strongman’s playbook, one that has four guiding features. Strongmen put their personalities at the front of their politics, they embrace machismo norms, relish in corruption, and do not shy away from the power of violence. We can use these insights to sniff out the strongmen lurking in systems of governance. Ben-Ghiat emphasises that we should be strongly motivated to do just this, as there is ‘too much at risk not to try’.

Cultish personalities are formed around these political leaders as they work to present themselves as ‘a man of the people’. They emphasise their standout character while simultaneously asserting themselves to be no different than the common citizen.

Their embracing of machismo, Ben-Ghiat explains, is reflected in hypermasculine behaviours, showcasing these examples with shirtless photos of both Trump and Putin. Women, they say, are ‘the enemy of the strongman’.

Corruption in the case of the strongman is of both the ‘moral and professional’ variety. We are told that the strongman commonly grants pardons which ‘free up criminals for service’, channelling those who some may take to be immoral offenders into positions of political power.

To convey their relationship to violence, Ben-Ghiat directs us to the presence of weapons in recent Republican political campaigns in the United States, telling us that these men ‘think they look strong, but it is really a sign of insecurity’. The strongman is making up for something.

Ben-Ghiat tell us that a contemporary commonality of these men is that they are often democratically elected, and that they pose considerable threats to the democratic systems in which they embed themselves.

Trump’s rallying tactics and his subsequent role in and commentary on the 2021 Capitol riot may be taken as emblematic of these strongman features. His mass appeal has been argued as being largely derived from ‘performative’ techniques that obfuscate his political goals or capacities more broadly. Trump continues to claim the democratic integrity of the United States to be under threat, asserting the actions of the Capitol rioters as warranted given the presence of electoral fraud in the country.

In these ways and others Trump seems to aptly align with Ben-Ghiat’s constructed, strongman persona. Impeachment, ongoing congressional hearings and public scrutiny evidently do little to undermine Trump’s confidence and his desire to reobtain the political power he once held.

There are mounting concerns that this phenomenon is not isolated to the United States. And that politicians globally can be seen as working to strengthen centralised systems of political power in ways which align with authoritarian leadership regimes. Could there be a risk that even the most historically democratic governments could begin to shift in comparable ways? If so, what could be done to manage that risk?

–

Pursuing political instigators of harm is a coherent goal and a strong incentive to Ben-Ghiat’s work. State leaders, even when democratically elected, are fashioned with powers that endow them the capacity to do both a world of good, and a world of harm. Many people were directly harmed by policies of the Trump administration; even more were harmed from the uncertainty his particular presence in office brought into their daily lives.

Ben-Ghiat recognises these sorts of harms and aims to call out the various features which they take as both forging and propagating them, egotistical, corruptive, and violent figureheads. When bundled together, these form the strongman, and for Ben-Ghiat the strongman should be our target.

If the goals of this work are the management of uncertainty and the desire to retain confidence in our capacity to uphold democratic structures and installed systems of justice, and we are sympathetic to these goals, we need ask what Ben-Ghiat’s approach to achieving them misses, or more poignantly, what it risks.

Bertrand Russel, not unlike Ben-Ghiat, was similarly sceptical of politicians. He remarks, “since politicians are divided into rival groups, they aim at similarly dividing the nation…”. Importantly distinct from Ben-Ghiat however, Russel’s scepticism is namely directed at the two-party political system as it stood in early 20th century Britain, and the impact this system has on the wider populations who comprise it.

Features of Ben-Ghiat’s strongman criteria are not in opposition to Russel’s characterisation of political figures more broadly. Yet Russel’s evaluations of these harm attend more heavily to the relationships that citizens, or voters, have to these politicians.

“The power of the politician, in a democracy” Russel writes, “depends upon his adopting the opinions which seem right to the average man”. For Russel, both the best and the worst of our politicians are reflections of and responsive to the ideas and sentiments of the populations they operate within.

The risk of Ben-Ghiat’s approach is that attending so heavily to the strongman, determining what he is and is not, may unhelpfully be turning our gaze away from our communities who, as Ben-Ghiat remarks, oftentimes democratically elect the very figureheads they and others wish to repudiate.

Sources of harm do not always come to us wrapped up in neat and tidy (shirtless) packages. Tirelessly seeking to group together ‘bad men’ can diminish our capacity to see other less precise but perhaps more pervasive sources of harm.

Comprehensively managing any risk a strongman may pose to our society will only be minimally addressed by stringing together various features that are said to necessarily render that man strong.

There is certainly time and space for the sort of work Ben-Ghiat dedicates themselves to.

Though if we are committed to protecting systems of democracy, and to ensuring that basic rights are genuinely upheld, we may be best served by turning our attention away from contemporary figureheads and towards those who cast their votes in favour of them, and to those systems of governance that forge and foster polarisation.

Naming and shaming the strongman, however accurately, will do little in the face of many who take his central features to be admirable strengths. Let us ensure that our pursuits of certainty and stability do not come at the cost of neglecting to engage with those around us who evidently have different assessments about just how risky a strongman really is.

Tune into Ruth Ben-Ghiat’s full FODI 2022 discussion, Return of the Strongman

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Banks now have an incentive to change

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights