Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Gordon Young 17 JAN 2019

Few topics bridge the ever widening divide between both sides of politics quite like the need to manage population growth.

Whether it’s immigration or environmental sustainability, fiscal responsibility or social justice. That the global population breached 7.5 billion in 2017 has everyone concerned.

We are at the point where the sheer volume of people will start to put every system we rely on under very serious stress.

This is the key idea motivating the centrist political party Sustainable Australia. Led by William Bourke and joined by Dick Smith, the party advocates for a non-discriminatory annual immigration cap at 70,000 persons, down from the current figure of around 200,000 – aimed at a “better, not bigger” Australia.

Join the first IQ2 debate for 2019, “Curb Immigration”. Sydney Town Hall, 26 March. Tickets here.

While the party has been accused of xenophobic bigotry for this stance, their policy makes clear they are not concerned about an immigrant’s religion, culture, or race. Their concern is exclusively for the stress greater numbers of migrants will place on Australia’s infrastructure and environment.

It is a compelling argument. After all, what is the point of the state if not to protect the interests of its citizens?

A Looming Problem

We should be concerned with the needs and interests of our international neighbours, but such concerns must surely be strictly secondary to our own. When our nearest neighbour has approximately ten times our population, squeezed into a landmass twenty five per cent Australia’s size, and ranks 113 places behind us in the Human Development Index, one can be forgiven for believing that limited immigration is critical for ongoing Australian quality of life.

This stance is further bolstered by the highly isolated, and therefore vulnerable nature of Australia’s ecosystem. Australia has the fourth highest level of animal species extinction in the world, with 106 listed as Critically Endangered and significantly more as Endangered or Under Threat.

Much of this is due to habitat loss from human encroachment as suburbs and agricultural lands expand for our increasing needs. The introduction of foreign flora and fauna can be absolutely devastating to these species, greatly facilitated by increased movement between neighbour nations (hence the virtually unparalleled ferocity of our quarantine standards).

While the nation may be a considerable exporter of foodstuffs, many argue Australia is already well over its carrying capacity. Any additional production will be degrading the land and our ability to continue growing food into the future.

The combination of ecological threats and socio-economic pressure makes the argument for limiting immigration to sustainable numbers a powerful one.

But it is absolutely doomed to failure.

Fortress Australia

If the objective of limiting immigration to Australia is both to protect our environment and maintain high quality of life, “Fortress Australia” will fail on both fronts. Why?

Because it does nothing to address the fundamental problem at hand. Unsustainable population growth in a world of limited resources.

Immigration controls may indeed protect both the Australian quality of life and its environment for a time, but without effective strategic intervention, the population burden in neighbouring countries will only continue to grow.

As conditions worsen and resources dwindle, exacerbated by the impacts of anthropogenic climate change, citizens of those overpopulated nations will seek an alternative. What could be more appealing than the enormous, low-density nation with incredibly high quality of life, right next door to them?

If a mere 10 percent of Indonesians (the vast majority of which live on the coast and are exceptionally vulnerable to climate change impacts) decided to attempt the crossing to Australia, we would be confronted by a flotilla equivalent to our entire national population.

The Dilemma

At this point we have one of two choices: suffer through the impact of over a decade’s worth of immigration in one go or commit military action against twenty-five million human beings. Such a choice is a Utilitarian nightmare, an impossible choice between terrible options, with the best possible result still involving massive and sustained suffering for all involved. While ethics can provide us with the tools to make such apocalyptic decisions, the best response by far is to prevent such choices from emerging at all.

Population growth is a real and tangible threat to the quality of life for all human beings on the planet, and like all great strategic threats, can only be solved by proactively engaging in its entirety – not just its symptoms.

Significant progress has been made thus far through programs that promote contraception and female reproductive rights. There is a strong correlation between nations with lower income inequality and population growth, indicating that economic equity can also contribute towards the stabilisation of population growth. This is illustrated by the decreasing fertility rates in most developed nations like Australia, the UK and particularly Japan.

Cause and Effect

The addressing of aggravating factors such as climate change – a problem overwhelmingly caused by developed nations such as Australia, both historically and currently through our export of brown coal– and continued good-faith collaboration with these developing nations to establish renewable energy production, will greatly assist to prevent a crisis occurring.

When concepts such as immigration limitations seek to protect our nation by addressing the symptoms, we are better served by asking how the problem can be solved from its root.

Gordon Young is an ethicist, principal of Ethilogical Consulting and lecturer in professional ethics at RMIT University’s School of Design.

MOST POPULAR

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

An ethical dilemma for accountants

ArticleBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Ethics in engineering makes good foundations

EssayBUSINESS + LEADERSHIP

Has passivity contributed to the rise of corrupt lawyers?

BY Gordon Young

Gordon Young is a lecturer on professional ethics at RMIT University and principal at Ethilogical Consulting.

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentScience + Technology

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2018

If you were born in 1989 or after, you haven’t yet voted in an election that’s seen a Prime Minister serve a full term.

Some point to social media, the online stomping grounds of digital natives, as the cause of this. As Emma Alberici pointed out, Twitter launched in 2006, the year before Kevin ’07 became PM.

Some blame widening political polarisation, of which there is evidence social media plays a crucial role.

If we take a look though, the thing that keeps killing our PMs’ popularity in the polls and party room is climate and energy policy. It sounds completely anodyne until you realise what a deadly assassin it is.

Rudd

Kevin Rudd declared, “Climate change is the great moral challenge of our generation”. This strategic focus on global warming contributed to him defeating John Howard to become Prime Minister in December 2007. As soon as Rudd took office, he cemented his green brand by ratifying the Kyoto Protocol, something his predecessor refused to do.

There were two other major efforts by the Rudd government to address emissions and climate change. The first was the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme(CPRS) led by then environment minister Penny Wong. It was a ‘cap and trade’ system that had bi-partisan support from the Turnbull led opposition party… until Turnbull lost his shadow leadership to Abbott over it. More on this soon.

Then there was the December 2009 United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen, officially called COP15 (because it was the fifteenth session of the Conference of Parties). Rudd and Wong attended the summit and worked tirelessly with other nations to create a framework for reducing global energy consumption. But COP15 was unsuccessful in that no legally binding emissions limits were set.

Only a few months later, the CPRS was ditched by the Labor government who saw it would never be legislated due to a lack of support. Rudd was seen as ineffectual on climate change policy, the core issue he championed. His popularity plummeted.

Gillard

Enter Julia Gillard. She took poll position in the Labor party in June 2010 in what will be remembered as the “knifing of Kevin Rudd”.

Ahead of the election she said she would “tackle the challenge of climate change” with investments in renewables. She promised, “There will be no carbon tax under the government I lead”.

Had she known the election would result in the first federal hung parliament since 1940, when Menzies was PM, she may not have uttered those words. Gillard wheeled and dealed to form a minority government with the support of a motley crew – Adam Bandt, a Greens MP from Melbourne, and independents Andrew Wilkie from Hobart, and Rob Oakeshott and Tony Windsor from regional NSW. The compromises and negotiations required to please this diverse bunch would make passing legislation a challenging process.

To add to a further degree of difficulty, the Greens held the balance of power in the Senate. Gillard suggested they used this to force her hand to introduce the carbon tax. Then Greens leader Bob Brown denied that claim, saying it was a “mutual agreement”. A carbon price was legislated in November 2011 to much controversy.

Abbott went hard on this broken election promise, repeating his phrase “axe the tax” at every opportunity. Gillard became the unpopular one.

Rudd 2.0

Crouching tiger Rudd leapt up from his grassy foreign ministry portfolio and took the prime ministership back in June 2013. This second stint lasted three months until Labor lost the election.

Abbott

Prime Minister Abbott launched a cornerstone energy policy in December 2013 that might be described as the opposite of Labor’s carbon price. Instead of making polluters pay, it offered financial incentives to those that reduced emissions. It was called the Emissions Reduction Fund and was criticised for being “unclear”. The ERF was connected to the Coalition’s Direct Action Plan which they promoted in opposition.

Abbott stayed true to his “axe the tax” slogan and repealed the carbon price in 2014.

As time moved on, the Coalition government did not do well in news polls – they lost 30 in a row at one stage. Turnbull cited this and creating “strong business confidence” when he announced he would challenge the PM for his job.

Turnbull

After a summer of heatwaves and blackouts, Turnbull and environment minister Josh Frydenberg created the National Energy Guarantee. It aimed to ensure Australia had enough reliable energy in market, support both renewables and traditional power sources, and could meet the emissions reduction targets set by the Paris Agreement. Business, wanting certainty, backed the NEG. It was signed off 14 August.

But rumblings within the Coalition party room over the policy exploded into the epic leadership spill we just saw unfold. It was agitated by Abbott who said:

“This is by far the most important issue that the government confronts because this will shape our economy, this will determine our prosperity and the kind of industries we have for decades to come. That’s why this is so important and that’s why any attempt to try to snow this through … would be dead wrong.”

Turnbull tried to negotiate with the conservative MPs of his party on the NEG. When that failed and he saw his leadership was under serious threat, he killed it off himself. Little did he know he would go down with it.

Peter Dutton continued with a leadership challenge. Turnbull stepped back saying he would not contest and would resign no matter what. His supporters Scott Morrison and Julie Bishop stepped up.

Morrison

After a spat over the NEG, Scott Morrison has just won the prime ministership with 45 votes over Dutton’s 40.

Killers

We have a series of energy policies that were killed off with prime minister after prime minister. We are yet to see a policy attract bi-partisan support that aims to deliver reliable energy at lower emissions and affordable prices. And if you’re 29 or younger, you’re yet to vote in an election that will see a Prime Minister serve a full term.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Why ethics matters for autonomous cars

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

On plagiarism, fairness and AI

Big thinker

Climate + Environment

7 thinkers improving our ethical understanding of the environment

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 20 AUG 2018

We’ve got NEGs, NEMs, and Finkels a-plenty. Here is a cheat sheet for this whole energy debate that’s speeding along like a coal train and undermining Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s authority. Let’s take it from the start…

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change – 1992

This Convention marked the first time combating climate change was seen as an international priority. It had near-universal membership, with countries including Australia all committed to curbing greenhouse gas emissions. The Kyoto Protocol was its operative arm (more on this below).

The Kyoto Protocol – December 1997

The Kyoto Protocol is an internationally binding agreement that sets emission reduction targets. It gets its name from the Japanese city it was ratified in and is linked to the aforementioned UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Protocol’s stance is that developed nations should shoulder the burden of reducing emissions because they have been creating the bulk of them for over 150 years of industrial activity. The US refused to sign the Protocol because the two largest CO2 emitters, China and India, were exempt for their “developing” status. When Canada withdrew in 2011, saving the country $14 billion in penalties, it became clear the Kyoto Protocol needed some rethinking.

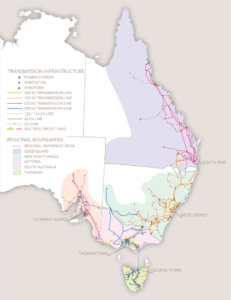

Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) – 1998

Forget the fancy name. This is the grid. And Australia’s National Electricity Market is one of the world’s longest power grids. It connects suppliers and consumers down the entire east and south east coasts of the continent. It spans across six states and territories and hops over the Bass Strait connecting Tasmania. Western Australia and the Northern Territory aren’t connected to the NEM because of distance.

The NEM is made up of more than 300 organisations, including businesses and state government departments, that work to generate, transport and deliver electricity to Australian users. This is no mean feat. Before reliable batteries hit the market, which are still not widely rolled out, electricity has been difficult to store. We’ve needed to continuously generate it to meet our 24/7 demands. The NEM, formally established under the Keating Labor government, is an always operating complex grid.

The Paris Agreement aka the Paris Accord – November 2016

The Paris Agreement attempted to address the oversight of the Kyoto Protocol (that the largest emitters like China and India were exempt) with two fundamental differences – each country sets its own limits and developing countries be supported. The overarching aim of this agreement is to keep global temperatures “well below” an increase of two degrees and attempt to achieve a limit of one and a half degrees above pre-industrial levels (accounting for global population growth which drives demand for energy). Except Australia isn’t tracking well. We’ve already gone past the halfway mark and there’s more than a decade before the 2030 deadline. When US President Donald Trump denounced the Paris Agreement last year, there was concern this would influence other countries to pull out – including Australia. Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott suggested we signed up following the US’s lead. But Foreign Minister Julie Bishop rebutted this when she said: “When we signed up to the Paris Agreement it was in the full knowledge it would be an agreement Australia would be held to account for and it wasn’t an aspiration, it was a commitment … Australia plays by the rules — if we sign an agreement, we stick to the agreement.”

The Finkel Review – June 2017

Following the South Australian blackout of 2017 and rapidly increasing electricity costs, people began asking if our country’s entire energy system needs an overhaul. How do we get reliable, cheap energy to a growing population and reduce emissions? Dr Alan Finkel, Australia’s chief scientist, was commissioned by the federal government to review our energy market’s sustainability, environmental impact, and affordability. Here’s what the Review found:

Sustainability:

- A transition to low emission energy needs to be supported by a system-wide grid across the nation.

- Regular regional assessments will provide bespoke approaches to delivering energy to communities that have different needs to cities.

- Energy companies that want to close their power plants should give three years’ notice so other energy options can be built to service consumers.

Affordability:

- A new Energy Security Board (ESB) would deliver the Review’s recommendations, overseeing the monopolised energy market.

Environmental impact:

- Currently, our electricity is mostly generated by fossil fuels (87 percent), producing 35 percent of our total greenhouse gases.

- We’re can’t transition to renewables without a plan.

- A Clean Energy Target (CET), would force electricity companies to provide a set amount of power from “low emissions” generators, like wind and solar. This set amount would be determined by the government.

-

- The government rejected the CET on the basis that it would not do enough to reduce energy prices. This was one out of 50 recommendations posed in the Finkel Review.

ACCC Report – July 2018

The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission’s Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry Report drove home the prices consumers and businesses were paying for electricity were unreasonably high. The market was too concentrated, its charges too confusing, and bad policy decisions by government have been adding significant costs to our electricity bills. The ACCC has backed the National Energy Guarantee, saying it should drive down prices but needs safeguards to ensure large incumbents do not gain more market control.

National Energy Guarantee (NEG)– present 20 August 2018

The NEG was the Turnbull government’s effort to make a national energy policy to deliver reliable, affordable energy and transition from fossil fuels to renewables. It aimed to ‘guarantee’ two obligations from energy retailers:

- To provide sufficient quantities of reliable energy to the market (so no more black outs).

- To meet the emissions reduction targets set by the Paris Agreement (so less coal powered electricity).

It was meant to lower energy prices and increase investment in clean energy generation, including wind, solar, batteries, and other renewables. The NEG is a big deal, not least because it has been threatening Malcolm Turnbull’s Prime Ministership. It is the latest in a long line of energy almost-policies. It attempted to do what the carbon tax, emissions intensity scheme, and clean energy target haven’t – integrate climate change targets, reduce energy prices, and improve energy reliability into a single policy with bipartisan support. Ambitious. And it seems to have been ditched by Turnbull because he has been pressured by his own party. Supporters of the NEG feel it is an overdue radical change to address the pressing issues of rising energy bills, unreliable power, and climate change. But its detractors on the left say the NEG is not ambitious enough, and on the right too cavalier because the complexity of the National Energy Market cannot be swiftly replaced.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The energy debate to date – recommended reads

The energy debate to date – recommended reads

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + Environment

BY The Ethics Centre 18 AUG 2018

Australia, we put it to you. ‘Is it too soon to ditch fossil fuels?’ We’ve waded through political waters and presented our shiniest pearls for your perusal.

Cheat Sheet

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

The Ethics Centre

18 October 2018

Before action must come knowledge. And before knowledge must come sorting through a heap of confusing, jargonistic, off-putting acronyms, reviews, and accords. Worry not, we’ve got your back and did it for you. Our cheat sheet will brush you up on all those names that keep getting dropped in the Australian energy debate like they’re hot coals.

Video

Australia’s energy crisis: “Absolute shambles, national embarrassment and a disgrace”

7.30, ABC News

Ian Verrender

13 Feb 2017

This 7.30 report is a perfect backgrounder to the mess that is Australia’s energy crisis. The NEM broke leaving hot and bothered South Australians without electricity (you read the cheat sheet so you know the NEM is a fancy acronym for the grid). A Victorian power plant that supplied 20 percent of the state’s energy simply closed shop. Renewables are unreliable but fossil fuels are killing the planet. Holy calamity!

Interactive

They Vote For You – How does your MP vote on the issues that matter to you?

Open Australia Foundation

If you’re rearing to parade your opinion, hold on. Haste makes waste. While we’re between elections, how about taking a look at how your local MP voted on energy? Did they champion a fast switch to renewables or continued support for fossil fuels like coal and gas? Forget what they said in the run up to an election and check out what they did.

Movie

And one for fun. Maybe a post-apocalyptic energy crisis isn’t so bad if we can also have double-necked flame guitars.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

“Animal rights should trump human interests” – what’s the debate?

Explainer

Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Longtermism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 18 APR 2018

We all know the way we shop is unsustainable.

Australians are the second biggest consumers of textiles worldwide. We throw more than 500,000 tonnes of the stuff into landfill every day. We only wear our garments seven times before throwing them away and still buy an average of twenty seven kilograms of new clothing each year.

The ethical fashion movement promotes a cull of fast fashion’s massive social and environmental impact. But why aren’t more people engaging in it?

We spoke to Clara Vuletich about the five biggest myths of ethical fashion – and if they’re keeping people out.

1. Ethical fashion has to be exclusive

It used to be the case that shopping ethically meant visiting tiny, hole-in-the-wall boutiques, which were either aggressively minimalist or bursting with colours a Crayola pack would be shy to wear. But it’s becoming mainstream.

Vuletich says big brands like H&M and Country Road are engaging with the ethical space in ways unique to their breadth and industry relationships. Another brand, Uniqlo, has introduced a recycling drive for customers to return their secondhand clothes. Though these actions are often met with a sceptical “But it’s just PR” comment, Vuletich says they are a step in the right direction.

‘The people that work in this space aren’t monsters’, she says. ‘They aren’t all ego-driven. It’s much more nuanced than that.’ The relationship a big brand like H&M has developed over decades with their primary garment supplier in Shanghai (for example) isn’t insignificant. They know their names, their families, their lives.

2. Ethical fashion has to be vegan, natural and eco-friendly

Catch-all phrases like natural, eco-friendly, or yes, ethical, are usually a sign to look further, warns Vuletich. Cotton, one of the most prolific materials worldwide, almost always produces toxic effluent from pesticides and dyes, and relies on infamously exploitative farming environments.

According to Levi’s, one denim pair of jeans is made with 2,600 litres of water. Polyester, a synthetic material derived from plastic, is far more easily recycled and reused than any other natural material.

But polyester can take up to 200 years to decompose. In landfill, wool creates methane gas. So which is better for the environment? The complexity of textile production makes it impossible to rank fabrics on a hierarchy of environmental sustainability.

3. Ethical fashion has to be local

Cutting down transport emissions does matter. But the fact is, unless we start growing cotton farms and erecting textile mills in our local communities, the creation of any piece of clothing will have some international process to it.

A ‘Made in Australia’ tag won’t always be the guarantor of quality and safe working conditions. Neither does a ‘Made in China’ tag mean poor workmanship and sweatshops (anymore).

For the quality, bulk, and turnaround the Australian fashion market wants, whether ethical or not, international processes are not an unfortunate by-product – they are crucial to its existence. Fabric manufacturing is one of the quickest ways for communities and countries to rise out of poverty and the solution isn’t to pull the rug out from under them.

4. Ethical fashion has to be expensive

If you’re looking for a new piece of clothing where every worker in the supply chain has been paid well, it stands to reason the final product will be expensive. If you don’t have money to burn, there are other clothing choices you can make that won’t exploit the earth and human race.

Vuletich is a big fan of secondhand shopping – think Salvos, Vinnies, U-Turn, Swop, Red Cross, Gumtree… Secondhand goods they may be, but that’s not a codeword for cheap, shoddy, or badly made. Instead of a fast fashion giant, your purchase funds a local charity, business, or market stall owner.

No extra resources were extracted for anyone to get that piece of clothing to you, nor was anyone enslaved to sew your new threads. It’s likely a local near the shop donated it, so transport emissions are low, and you’re also keeping something out of landfill.

5. Ethical fashion leads to social impact

Vuletich is wary of making huge claims. Slogans like ethical fashion will save the world are just that – slogans. The effectiveness of campaigns like the 1-for-1 business model have been thoroughly debunked, and it’s doubtful buying a pair of fair trade sandals will do as much good as a country changing their labour laws. But will it have some impact? She says yes.

For someone not in the industry, the complexity is overwhelming. Trying to track the supply chain of a polyester dress might take you to one factory in Turkey, while following the history of a pair of denim jeans will take you to China – if the clothing company even knows where their raw materials are sourced. The sheer scale of garment manufacturing is the main reason ethical fashion is intimidating, and that’s not taking into account consumer needs.

Fashion is personal. People want different things from their clothing – they might want it to be free of animal products, or for it to be breathable and comfortable, or for it to be made with as little impact to local communities as possible. They might want it to make them stand out, or to make them blend in.

They might want it to be easy and careless. But with the growing social, political and environmental consciousness around fashion, it’s difficult to stay unaware. Maybe it won’t change the world, but rest assured that the choices you make as a consumer do add up.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

David Pocock’s rugby prowess and social activism is born of virtue

LISTEN

Society + Culture

FODI: The In-Between

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to deal with people who aren’t doing their bit to flatten the curve

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Bill Mollison

Bill Mollison (1928—2016) was an Australian ecologist and the ‘father of permaculture’, a type of agricultural design and practice he created, named and taught.

Having co-wrote Permaculture One with his student and colleague David Holmgrem, Mollison later founded the Permaculture Institute of Tasmania and taught his Permaculture Design Course and Certificate (PDCC) all around the world.

Today, his philosophy has reached millions. His commitment to ethics brings philosophy back into the marketplace and onto the farm – down to its earthworms and well-tilled soil.

What is permaculture?

Permaculture is an ethical design framework for sustainable farming. It combines traditional farming methods of Indigenous and Aboriginal communities with renewable technologies and low-energy materials. Masanobu Fukuoka, a Japanese farmer and creator of “Do-nothing Farming”, is cited as another influence on Mollison’s farming philosophy.

Mollison believed that farming monocultures, like corn, or wheat, was unsustainable. Instead, he called for ‘food forests’ – a varied collection of plant and tree species that support equally as diverse animal life.

Like a delicate structure of checks and balances, the little relationships formed in such an ecosystem would keep it self-sufficient. According to Mollison, once complete, a successful permaculture design wouldn’t need any human touch at all.

What’s wrong with what we’ve got now?

Because monocultures are more efficient, fast and easy to harvest, they’ve been the go-to for industrial farming. But, according to Mollison, their future is limited, with no means to reproduce the same healthy ecosystem it profits from. In fact, it’s often expected to meet the surplus demand of nations that already have enough food.

Mollison considered this form of agriculture as unethical, self-destructive and “temporary”. Rather than people being relied on to provide yields, he wanted to make us another part of the agricultural web. No more, no less.

This, along with permaculture’s three core ethics (earth care, people care and fair share), would transform how plants, animals and humans all interact with each other. People – not just farmers – would turn into active stewards of the earth. The social and economic needs of interdependent communities would be satisfied and looked after, with global surplus distributed to those most in need.

Some people find his views noble, but unrealistic. Indeed, his repositioning of farming as political might be novel. But applying ethics to fulfil basic needs of food and shelter, to Mollison, is essential:

“The greatest change we need to make is from consumption to production, even if on a small scale, in our own gardens. If only 10% of us can do this, there is enough for everyone. Hence the futility of revolutionaries who have no gardens, who depend on the very system they attack, and who produce words and bullets, not food and shelter.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Society + Culture

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

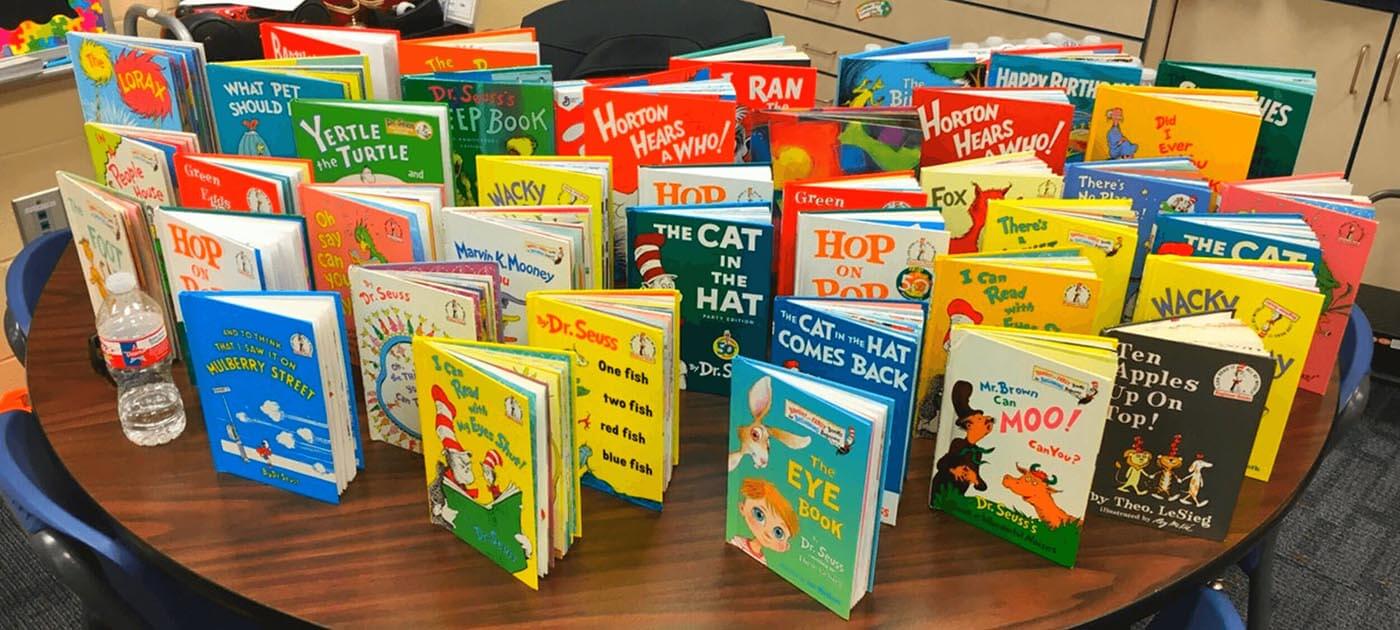

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipClimate + Environment

BY The Ethics Centre 5 JUL 2017

Where lying is the abuse of truth and harm the abuse of dignity, philosophers associate theft with the abuse of ownership.

We tend to take property for granted. People own things, share things or have access to things that don’t belong to them. We rarely stop to think how we come to own things, whether there are some things we shouldn’t be allowed to own or whether our ideas of property and ownership are adequate for everybody.

This is where English philosopher John Locke comes in.

Locke believed that in a state of nature – before a government, human made laws or an established economic system – natural resources were shared by everyone. Similar to a shared cattle-grazing ground called the Commons, these were not privately owned and so accessible to all.

But this didn’t last forever. He believed common property naturally transformed into private property through ownership. Locke had some ideas as to how this should be done, and came up with three conditions:

- First, limit what you take from the Commons so everyone else can enjoy the shared resource.

- Second, take only what you can use.

- Third, that you can only own something if you’ve worked and exerted labour on it. (This is his labour theory of property).

Though his ideas form the bedrock of modern private property ownership, they come with their fair share of critics.

Ancient Greek philosopher Plato thought collective property was a more appropriate way to unite people behind shared goals. He thought it was better for everyone to celebrate or grieve together than have some people happy and others sad at the way events differently affect their privately-owned resources.

Others wonder if it is complex enough for the modern world, where the resource gap between rich companies and poor communities widens. Does this satisfy Locke’s criteria of leaving the Commons “enough and as good”? He might have a criticism of his own about our current property laws – that they’ve gone beyond what our natural rights allow.

Some critics also say his theory denies the cultivation techniques and land ownership of groups like the Native Americans or the Aboriginal Australians. While Locke’s work serves as a useful explanation of Western conceptions of property ownership, we should wonder if it is as natural as he thought it was.

On the other hand, it’s likely Locke simply had no idea of the way in which Indigenous people have managed the landscape over millennia. Had he understood this, then he may have recognised the way Indigenous groups use and relate to land as an example of property ownership.

Karl Marx, and the closely associated philosophies of socialism and communism, prioritise common or collective property over private forms of property. He thought humanity should – and does – move toward co-operative work and shared ownership of resources.

However, Marx’s work on alienation may be a common ground. This is when people’s work becomes meaningless because they can’t afford to buy the things they’re working to make. They can never see or enjoy the fruits of their labour – nor can they own them. Considering the importance Locke places on labour and ownership, he may have had a couple of things to say about that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Who is to blame? Moral responsibility and the case for reparations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Office flings and firings

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 1 NOV 2016

The nation stops – and turns a blind eye.

The Melbourne Cup is the race that ‘convenes’ rather than ‘stops’ the nation. It’s a classic example of a moment when the abstraction that is the nation – large, sprawling, messy and diverse – is made temporarily and symbolically concrete. This is an illusion. But perhaps a necessary one.

The mega media sport spectacle is highly serviceable to the fantasy of the united nation because it is popular culture played out in real time. Sport is implicated in the idea of a singular Australian identity because it is apparently open and meritocratic, and also has operated historically as a vehicle for the projection of ‘Australianness’.

The Melbourne Cup represents the pros and cons of contemporary sport and society. It is devoted to pleasure as an interruption of the daily work routine that consumes more and more of our time. It is carnivalesque – fleetingly turning the world upside down.

But it is characterised by the range of excess demanded by consumer capitalism – risky financial expenditure, alcohol consumption and repressive co-optation. All of this activity is conducted using the body of the horse that is celebrated one minute and whipped the next, highly prized for sporting and breeding performance in some cases and turned into abattoir fodder in others.

National sporting spectacles are here to stay. The ‘people’, the state and the commercial complex demand them, but they should not be excuses for rampant collective self-delusion.

– David Rowe, Professor of Cultural Research at Western Sydney University.

If you loved horses, you wouldn’t treat them as commodities

We’re often told those involved in the horse racing industry truly love horses and treat them with the utmost respect. I have no doubt they believe that to be true, but their actions don’t support these claims.

If those working with horses truly loved them, they would spend time and money re-homing and appropriately retiring racehorses at the end of their careers. Instead, the evidence suggests racehorses are only loved when they have the potential to make money. When they’re injured or no longer able to race, they’re often sent off to the knackery without a second’s thought.

The racing industry pushes horses beyond their natural limits. This results in short careers and extensive injuries, such as those suffered by Admiral Rakti last year. Since Admiral Rakti’s death, 127 horses have died on Australian race tracks.

The ultimate image for this exploitative approach to racing is the whip, which desperately needs to be banned. In doing so, we would see horses performing at the peak of their natural ability rather than desperately running due to fear and pain.

– Elio Celotto, Campaign Director at the Coalition for the Protection of Racehorses.

The risks of horse racing are imposed on unwilling participants

Horse racing differs ethically from other sports. In other sports, it is the participant who freely decides to accept the risks. In horse racing, the risks are relatively low for the riders and extremely high for the animals.

It is not unethical to accept the risks of a given sport. Nor, in my view, is it always unethical to take the life of animals. The question is whether the costs of horse racing are reasonable, or whether they are unacceptably high.

Most Australians today would have ethical objections to entertainments such as bullfighting or dog fighting, or the use of non-domestic animals in circus acts. The number of horses slaughtered annually as a result of the racing industry far exceeds the number of animal deaths from most of these other entertainments.

The costs of the racing industry are unacceptably high. The situation is unlikely to improve as long as horse racing in Australia remains so closely tied to the enormous economic interests of the gambling industry.

– Ben Myers, Lecturer in Systematic Theology at United Theological College.

The Melbourne Cup sweep is harmless fun, but not in the classroom

The effects of gambling are an oft-discussed topic among my colleagues, but in the past week the discussion has been triggered by an all-staff email about the office’s annual Melbourne Cup Sweep. One staff member felt it was totally inappropriate for an organisation operating in mental health and wellbeing to be promoting in any way a day of socially acceptable statewide gambling.

I actually disagree, although not strongly. A sweep is a one-off, fixed price competition, not much different from a raffle. It’s in no way addictive in the way that poker machines and online betting can be.

The normalisation of gambling is certainly insidious. There is some evidence that the younger a person is when they have their first betting win, the more likely they are to develop problems down the track. So a sweep in a primary school does sound icky to me.

– Heather Grindley, Public Interest Manager at the Australian Psychological Society.

The spectacle is lost in a “feeding frenzy” of gambling

The Melbourne Cup is a genuine Australian icon. However, it’s now also a commodified hub for a gambling feeding frenzy. This is a tough time of year for people who are trying to restrain their gambling.

Effective regulation can undoubtedly reduce the harms associated with gambling. Cup Day should be a reminder that commercialised gambling corrupts sport and induces misery for many, including those who never gamble. Decent regulation might reduce super-profits but it would certainly help make Australia’s unique sporting and social environment safer, more fun and lot more enjoyable.

– Charles Livingstone, Senior Lecturer in Public Health and Preventive Medicine at Monash University.

The Melbourne Cup pits debauchery against dignity

As I write, many will be gathered in offices, pubs and racecourses around the country dressed to the nines. Fascinators, frocks, loud ties and sharp suits are the order of the day for the “world’s richest race”.

And yet by the end of it all, many punters will be staggeringly drunk – their state highlighted by its juxtaposition to their glamorous attire. Every year, tabloids gleefully post pictures of women in various stages of undress – simultaneously glorifying and shaming the debauchery that accompanies a race some revellers will likely miss, having already passed out.

Ultimately the Melbourne Cup is full of ethical polarities. It follows the highs and lows of the race itself. Fine champagne is popped in celebration as punters pass out from one too many drinks, horses are glorified as they are exploited, and once-off punters dress up and participate in the same gambling industry that destroys so many lives.

Racing Victoria were unavailable for comment but directed readers to their position on equine welfare.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What is all this content doing to us?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

4 questions for an ethicist

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: WEIRD ethics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why it was wrong to kill Harambe

Why it was wrong to kill Harambe

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + Environment

BY Clive Phillips The Ethics Centre 2 JUN 2016

The killing of Harambe the gorilla at Cincinnati Zoo this week has aroused public sentiment in a way reminiscent of the public outrage caused by the killing of Cecil the lion.

This was not an isolated incident. On at least two previous occasions small children have accidentally fallen into gorilla pens. On both occasions the children were ‘protected’ by a prominent gorilla in the group, one female and one male, incidents which were heralded as examples of cross species animal altruism.

The incidents occurred in 1986 and 1991 in Jersey Zoo and Brookfield Zoo respectively – when rapid response teams would have been unknown. They demonstrate that gorillas are not dangerous animals.

This is further supported by the fact some witnesses’ reports said that Harambe was actually protecting the child and had not demonstrated any malevolence.

Animal behaviour expert, Professor Gisella Kaplan of the University of New England, has confirmed that gorillas are not inherently aggressive and would likely have not wanted to harm the child – a result of their social lifestyle and herbivorous diet.

Nowadays zoos have Dangerous Animal Response Teams, which in the ten minutes since the boy entered the enclosure made the decision to euthanise the gorilla. Members of this team are typically trained by the police to react to a dangerous animal threatening a member of the public.

Zoo animals already sacrifice many rights for the sake of human entertainment, education, conservation, and scientific endeavour.

Their first priority is for the safety of the public, then zoo staff. Only after these are assured is the animal’s wellbeing considered. As evidence of such a policy, Thayne Maynard, Director of Cincinnati Zoo, expressed public regret for the loss of Harambe as a future breeding male, a loss of genetic diversity, without any consideration for Harambe’s rights.

Zoos should have a policy based on an ethical appraisal of potential incidents based on higher level principles. These would include utilitarian, deontological, and virtue ethics principles.

From a utilitarian perspective, the harm caused by shooting Harambe, to him, his family, human witnesses, and the public generally, may have outweighed the small risk to the child. Harambe’s family will mourn his loss and may even have been traumatised by the event.

Deontologists would argue taking Harambe’s life would never be justified by the small risk to the child – the shooting constitutes a supreme example of a speciesist approach.

Insights from virtue ethics show how this incident has damaged the zoo’s reputation. Public outcry has accused the zoo of having little regard for the rights of its animal occupants – although the safeguarding of the child’s life may be welcomed by some future visitors. Is this the action we would expect of a ‘good’ zoo?

Instead, the zoo seems to have acted from self-interest, afraid of potential litigation should the child be harmed. From a commercial angle a seventeen year old gorilla is worth $100,000 to $200,000; a child’s life many millions. However, the zoo is likely to experience reduced visitor numbers for a prolonged period, as well as being responsible for damage to the reputation of American zoos more generally.

The zoo may also be liable for placing visitors in a dangerous situation, something not unheard of in zoos around the world. Owners of swimming pools in Australia could teach the zoos a lot about preventing small children entering facilities, with detailed regulations and strict monitoring minimising any risk to children.

Some zoos may have deliberately sacrificed safety for an enhanced visitor experience, with limited barriers between the public and apparently dangerous animals.

Harambe’s killing may yet prompt a renewed movement to provide legal recognition of the rights of great apes.

Zoo animals already sacrifice many rights for the sake of human entertainment, education, conservation and scientific endeavour. Our ‘contract’ with zoo animals, where we provide nutrition, good health, and companionship in return for the animals sacrificing their freedom, right to live, and reproduce naturally in a state of good welfare, stack the terms heavily in our favour.

Indeed, killing a defenceless animal that had not shown any aggression is tantamount to tearing up that contract.

The ethical dilemma over whether to shoot Harambe might have been avoided if a movement known as The Great Ape Project had succeeded. For over twenty years a group of philosophers, primatologists, and anthropologists have attempted to gain great apes, including gorillas, rights through the United Nations that would include the right to life.

The movement is based on overwhelming evidence for self-consciousness and other higher level cognitive abilities in great apes, which are undoubtedly greater than in some disabled humans who are adequately protected in law.

Although this has gained support in some minority states, it has yet to gain widespread acceptance, primarily because of determined opposition from scientists who reserve the right to use chimpanzees – another great ape – for medical research. Harambe’s killing may yet prompt a renewed movement to provide legal recognition of the rights of great apes.

Just like Cecil the lion, the killers of Harambe are being judged in the arena of social media. The pattern of argument there suggests members of the public would have preferred that the zoo accept some risk to the child before taking the extreme action of killing a harmless gorilla.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

WATCH

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

How to build good technology

Big thinker

Climate + Environment

7 thinkers improving our ethical understanding of the environment

BY Clive Phillips

Clive Phillips is Chair of Animal Welfare and Director of the Centre for Animal Welfare Ethics at the University of Queensland.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

“Animal rights should trump human interests” – what’s the debate?

“Animal rights should trump human interests” – what’s the debate?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 22 MAR 2016

Are the ways humans subject animals to our own needs and wants justified?

Humans regularly impose our own demands on the animal world, whether it’s eating meat, scientific testing, keeping pets, sport, entertainment or protecting ourselves. But is it reasonable and ethical to do so?

Humans and animals

We often talk about humans and animals as though they are two separate categories of being. But aren’t humans just another kind of animal?

Many would say “no”, claiming humans have greater moral value than other animals. Humans possess the ability to use reason while animals act only on instinct, they say. This ability to think this way is held up as the key factor that makes humans uniquely worthy of protection and having greater moral value than animals.

“Animals are not self-conscious and are there merely as means to an end. That end is man.” – Immanuel Kant

Others argue that this is “speciesism” because it shows an unjustifiable bias for human beings. To prove this, they might point to cases where a particular animal shows more reason than a particular human being – for example, a chimpanzee might show more rational thought than a person in a coma. If we don’t grant greater moral value to the animal in these cases, it shows that our beliefs are prejudicial.

Some will go further and suggest that reason is not relevant to questions of moral value, because it measures the value of animals against human standards. In determining how a creature should be treated, philosopher Jeremy Bentham wrote, “… the question is not ‘Can they reason?’, nor ‘Can they talk?’, but ‘Can they suffer?’”

So in determining whether animal rights should trump human interests, we first need to figure out how we measure the value of animals and humans.

Rights and interests

What are rights and how do they correspond to interests? Generally speaking, you have a right when you are entitled to do something or prevent someone else from doing something to you. If humans have the right to free speech, this is because they are entitled to speak freely without anyone stopping them. The right protects an activity or status you are entitled to.

Rights come in a range of forms – natural, moral, legal and so on – but violating someone’s right is always a serious ethical matter.

“Animals are my friends. I don’t eat my friends.” – George Bernard Shaw

Interests are broader than rights and less serious from an ethical perspective. We have an interest in something when we have something to gain or lose by its success or failure. Humans have interests in a range of different projects because our lives are diverse. We have interests in art, medical research, education, leisure, health…

When we ask whether animal rights should trump human interests, we are asking a few questions. Do animals have rights? What are they? And if animals do have rights, are they more or less important than the interests of humans? We know human rights will always trump human interests, but what about animal rights?

Animal rights vs animal welfare

A crucial point in this debate is understanding the difference between animal rights and animal welfare. Animal rights advocates believe animals deserve rights to prevent them from being treated in certain ways. The exploitation of animals who have rights is, they say, always morally wrong – just like it would be for a human.

Animal welfare advocates, on the other hand, believe using animals can be either ethical or, in practice, unavoidable. These people aim to reduce any suffering inflicted on animals, but don’t seek to end altogether what others regard as exploitative practices.

As one widely used quote puts it, “Animal rights advocates are campaigning for no cages, while animal welfarists are campaigning for bigger cages”.

Are they mutually exclusive? What does taking a welfarist approach say about the moral value of animals?

‘Animal rights should trump human interests’ took place on 3 May 2016 at the City Recital Hall in Sydney.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Plato

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships