Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 23 SEP 2025

When I facilitate a Circle of Chairs conversation at The Ethics Centre, I always pause before starting and remind myself that I’m about to enter a potentially dangerous space. There are few domains that are as hotly contested and emotionally charged as ethics.

In this space, people might have their deepest values questioned, their most cherished views challenged, and they are likely to encounter people who hold radically different moral and political beliefs to their own.

Yet, after stepping into many Circles, I can’t think of a single time when I haven’t stepped out having witnessed a rich, deep and often challenging conversation that has left everyone feeling closer together as humans, even if they remain far apart in their views.

This is because we don’t just encourage any kind of speech in a Circle of Chairs. We do acknowledge the importance of free speech, not least because it’s our best means of challenging conventional wisdom, correcting errors and seeking the truth. But we also recognise that just protecting free speech sets a perilously low bar for the quality of discourse.

Now seems like a good time to talk about how we talk to each other. Especially so in the wake of conservative commentator, Charlie Kirk’s, assassination in the United States. That horrific event, coupled with two late night talk show hosts being taken off air in recent months, ostensibly due to comments made that have offended the Trump administration and its ideological allies, has sparked numerous conversations about the nature of good faith debate and the limits of free speech.

But if we just limit ourselves to removing speech that is directly harmful, hateful or incites violence, it still leaves a lot of room for speech that can be deceptive, offensive, divisive and dehumanising. Which is why at The Ethics Centre, we treat free speech as a baseline and add other norms on top that serve to promote constructive discourse.

These norms enable people to engage with views that are vastly different to their own – including arguing for their own perspectives and challenging those they believe are wrong – without things slipping into vitriol or worse.

I wonder if these norms might be useful when it comes to think about how we ought to speak to each other. And I stress: these are norms, not laws. They are expectations around how to behave. They’re not intended to be used to silence or punish those who fail to conform to them. They are offered as a guide for those who want to break out of the cycles of polarising and vilifying speech that we see all too often today.

Respect

The first norm is in some ways the simplest, but also the most important: respect. It states that we should always recognise others’ inherent humanity, no matter how obtuse or perverse their beliefs.

What this means is that we might choose not to say something if we think doing so will disrespect or injure their dignity as a person. We already do this in many domains of our lives. If someone has just lost a loved one, we might refrain from criticising the deceased, even if we have a genuine grievance. Likewise, we might choose not to say something we believe is true if it might dehumanise or objectify someone. As they say, “honesty without compassion is cruelty”.

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strongly challenge others’ beliefs, especially if we feel they are false or harmful. Sometimes, we should do so even if it might offend them. But there’s a pragmatic element: without mutual respect, our challenges will likely fall on deaf ears, triggering defensiveness rather than encouraging openness.

Showing respect to someone you disagree with is a powerful tool to build the kind of trust that is necessary to have them actually listen to what you have to say. And the more trust and respect you build, the less chance you have of being seen to be disrespectful, and the more frank you can afford to be when you speak.

Good faith

The second norm is to always speak in good faith. This has two elements. The first is that we speak with good intention, with the aim to understand, find the truth and make the world a better place, rather than speaking to intimidate, self-aggrandise or hide an insecurity. The second element is that we speak with intellectual honesty, acknowledging our fallibility and being open to the possibility of being wrong.

We all know it’s all too easy to slip into bad faith, especially when emotions run high or we feel threatened. We might utter a barbed comment, or defend a position we don’t really understand, or we dig in our heels so we don’t look dumb. We also know what it’s like to encounter bad faith, like when you dismantle someone’s argument only to discover they haven’t changed their mind. It’s infuriating, and it can rapidly devolve a conversation into mutual bad faith attacks. You know, like what we see on social media.

Charity

The third norm is charity, which is just the flip side of good faith. Charity means we assume good faith on behalf of the person we’re speaking to rather than assuming the worst about them and their beliefs. It means filling in the blanks with the best possible version of their argument instead of jumping to attack the weakest possible version.

Charity also means giving people an on-ramp back to good faith if we do discover they are speaking in bad faith. Rather than writing them off, we try to show respect and find some mote of common ground – a shared value or belief – and build on that until we can better understand where we diverge, and talk about that.

These norms don’t guarantee all speech will be constructive. They’re not always easy to implement – especially in the unregulated wilderness of social media. But see them as being more aspirational, a kind of soft expectation that we place on ourselves and hope to demonstrate to others through the way we speak.

When we’re mindful of them, they can change conversations. I’ve seen it happen many times. I’ve seen political opponents really listen to each other and acknowledge that the other has a point. I’ve seen a climate denier and an environmental activist hug after a long conversation. I’ve seen an anti-vaxxer thank a science journalist for disagreeing without calling them names. It won’t always go like that. But in a world where we’re thrust into proximity with those we disagree with, where the threat of political violence will always hover in the wings, ready to take the stage when speech fails, I’m convinced these three norms can make a difference.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Feminist porn stars debunked

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccines: compulsory or conditional?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Can beggars be choosers?

As a shockingly picky child who rejected everything from unpeeled apples to mashed potatoes, I was the victim of every method of persuasion my parents tried to expand my palate — bribes of candy, hiding foods in other foods, even heartfelt pleas about starving kids hungry enough to be grateful to eat anything.

I didn’t think that last part was true — I couldn’t imagine any hunger powerful enough to overcome my disgust at seafood. While this was the naive view of a privileged seven-year-old, I later realised I was right in a different way. Not about chicken nuggets being peak cuisine, but about the idea that emotional reactions to food — often dismissed as “wants” — cannot be ignored, even for those in need. This idea is central to one of the most significant problems we face in humanitarian aid.

While hunger does make us more receptive to different foods, there are limits to this acceptance. We see this clearly in the case study of Plumpy’Nut, an incredibly powerful Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) widely used to combat malnutrition. With its calorie and nutrient-rich mixture of peanut butter, milk powder, and essential vitamins, the paste helped 95% of the Malawian children in its first six-week trial in 2001 make a full recovery, while only 25% of children treated through hospitals did. It’s still being used today, including in the Gaza famine.

However, in her book First Bite (2015), Bee Wilson reveals a different side of this otherwise miraculous invention — its reception outside of Africa. In Bangladesh, a place where 2 in 3 children live in food poverty, the sweet, sticky paste hasn’t been nearly as well-received as we might think. Out of 149 Bangladeshi caregivers, six out of ten said Plumpy’Nut was not an acceptable food, and 37% of caregivers said it made their children vomit. Many children despised the smell of the peanuts, a food foreign to Bangladeshi cuisine, while others reviled its sweetness and thick texture. This is despite 112 parents also admitting that it had helped children gain weight.

It was as if they refused to accept that this strange brown paste, so unlike food as they knew it, could satisfy a child’s hunger even despite seeing real results.

If it were true that a “really hungry” child would eat anything, then residents of Dhaka slums ought to be overjoyed to receive free packets of Plumpy’Nut. However, they were clearly not, showing that food-induced disgust is psychologically and culturally hardwired rather than a mere matter of fussiness.

Cultural beliefs persist even in extreme conditions, so we must take them into account when designing effective humanitarian aid. Even under a utilitarian worldview that prioritises physiological “needs” over “wants” in an attempt to save as many lives as possible, aid only has good consequences if it is accepted. When it incites physical revulsion, the intended benefits vanish, leaving behind not only wasted resources but also preventable lifelong medical consequences. In order to truly “feed the most people,” providers of aid are ethically obligated to ensure that it aligns with cultural expectations.

However, this example also highlights a deeper moral problem. By ranking “needs” over “wants,” we send the message that people in need don’t deserve to have their preferences or cultures considered. When we treat the defining parts of someone’s identity as secondary, we risk dehumanising them — reducing them to interchangeable bodies to be fed, instead of people with dignity. Treating aid as a one-size-fits-all endeavour also renders the recipient’s cultural context, like the Bangladeshi aversion to peanuts, an inconvenient obstacle rather than essential knowledge. This perpetuates the core power imbalance of aid: the giver defines the problem and solution, while the receiver is stripped of agency, reduced to a passive vessel for Western benevolence, resulting in a reinforcement of dependency under the guise of charity rather than any true empowerment.

As philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues in her book Creating Capabilities (2011), true wellbeing isn’t merely about fulfilling basic biological requirements like calories. It’s about expanding the substantive freedoms and capabilities people have to live lives they value, including the ability to use their senses without revulsion, to participate in cultural practices, and to make choices about their own nourishment. Forcing a child to eat something they do not culturally see as food, despite its nutritional value, actively damages this capability.

This hierarchy of needs and wants therefore doesn’t alleviate suffering holistically — it trades one form of deprivation (hunger) for another (the denial of autonomy).

Even though research has now expanded into culturally appropriate RUTFs, such as a mung bean cake called “hebi” for use in Vietnam, it is revealing that these initiatives only began after the failure of Plumpy’Nut. When it comes to for-profit enterprises targeting wealthier consumers, market research is an essential part of preparation — think KFC rice and congee in China, or the Teriyaki McBurger in Japan. We know people have different palates across the world, and usually consider it. So why assume Plumpy’Nut would succeed unchanged in both Malawi and Bangladesh, two places with completely different cuisines?

We cannot simply rely on trial and error to improve the ways we distribute humanitarian aid. To truly help people — people, not just bodies to be sustained — we must consider the full picture of their identities. Dignity is the foundation upon which effective, lasting help is built because ultimately, humanitarianism that ignores the human is a contradiction. As citizens in a world where humanitarian crises dominate headlines, understanding these dynamics matters not just for policymakers, but for anyone who donates, protests, or speaks out in response to global events.

BY Sophie Yu

Sophie Yu is a Year 12 student at Redlands, Sydney, where she studies the International Baccalaureate. She is interested in philosophy, culture, and international affairs, and explores these through the mediums of public speaking, writing and the visual arts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

You’re the Voice: It’s our responsibility to vote wisely

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

3 Questions, 2 jabs, 1 Millennial

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

What happens when the progressive idea of cultural ‘safety’ turns on itself?

What happens when the progressive idea of cultural ‘safety’ turns on itself?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Hugh Breakey 4 SEP 2025

In mid-August, controversy enveloped the Bendigo Writers Festival. Just days before it began, festival organisers sent a code of conduct to its speakers – a code that drove more than 50 authors to make the difficult decision to pull out.

The code was intended to ensure the event’s safety, with a requirement to “avoid language or topics that could be considered inflammatory, divisive, or disrespectful”. Yet distressed speakers argued it made them feel culturally unsafe. Speakers on panels presented by La Trobe university were also required to employ a contested definition of antisemitism.

The incident is the most recent in a series of controversies in which progressive writers and artists have faced restrictions and cancellations, with organisations citing “safety” as the reason. They include libraries cancelling invited speakers and asking writers to avoid discussing Gaza, Palestine and Israel.

How did speech rules developed and promoted by the progressive left – rules promoting cultural safety and safe spaces – become tools that could be wielded against it?

Applying ‘safety’ to speech

Over recent years, “safety” – including in terms like “safe spaces” and “cultural safety” – has become a commonly raised ethical concern. Safe-speech norms often arise in the context of public deliberation, education and political speech.

“Safe spaces” are places where marginalised groups are protected against harassment, oppression and discrimination, including through speech like microaggressions, unthinking stereotypes and misgendering. Within safe spaces, protected groups are encouraged and empowered to speak about their experiences and needs.

Similarly, “cultural safety” refers to environments where there is no challenge or denial of people’s identities, allowing them to be genuinely heard. This can be crucial for First Nations communities, especially in health and legal contexts.

Safe-speech norms are therefore complex. They involve the freedom to speak, but also freedom from speech.

This way of thinking takes a broad view of the kinds of speech that can be interpreted as harmful or violent. Harmful speech does not just include hate speech and incitement. It also includes speech with unintended consequences and speech that challenges a person’s perceived identity.

These safe-speech norms, increasingly adopted in universities and other broadly progressive organisations, should be distinguished from “psychological safety”. This earlier concept refers to creating environments – such as workplaces – where it is safe to speak up, including to raise concerns or ask questions.

While psychological safety is a general norm protecting all parties, the more recent safe-speech norms protect specific marginalised groups. They aim to push back against larger systemic forces like racism or misogyny that would otherwise render those groups oppressed or unsafe. In some cases, the prioritisation of safety has led to deplatforming of speakers at universities.

With this special focus on oppressed minorities and heightened sensitivity to speech’s negative impacts, applying these norms has become a familiar part of progressive social justice efforts (sometimes pejoratively called “wokism”). Now, conservatives and others are employing the language of cultural safety to close down discussion of topics such as the war in Gaza.

Are safe-speech norms controversial?

By constraining what can be said, safe speech norms impinge on other potentially relevant ethical norms, such as those of public deliberation. These “town square” norms aim to encourage a diversity of views and allow space for a robust dialogue between different perspectives.

Public deliberation norms might be defended as part of the human right to free speech, or because arguing and deliberating with other people can be an important way of respecting them.

Alternatively, public deliberation can be defended by appeal to democracy, which requires more than merely casting votes. Citizens must be able to hear and voice different perspectives and arguments.

Those in favour of free speech and the public square will look suspiciously at safe-speech norms, worrying that they give rise to the well known risks of political censorship. Thinkers like Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff explicitly criticise “safetyism”, arguing the prioritisation of emotional safety inappropriately coddles young people.

Supporters of safe-speech norms might respond in different ways to these objections. One response might be that safety doesn’t intrude very much on dialogue anyway (at least, not on the type of dialogue worth having). Another response might be to challenge the value of public debate itself, seeing any system that does not explicitly work to support the marginalised as inherently oppressive.

Yet another response might be to query whether writers festivals are an apt place for public debate. Most speakers want an enjoyable experience and to promote their book (even when such books explore contentious ideas). Many in the audience will be supportive of the authors’ ideas and positions. Some will even be fans. Maybe it’s not so bad if most festival sessions are “love-ins”.

Prohibited vs. protected

In order to protect and empower specific marginalised groups, safe-speech norms both support and restrain speech. So long as the views of these protected groups are relatively aligned with each other, these norms work coherently. The speech that is being prohibited doesn’t overlap with the speech that is being protected.

But what happens when members of two marginalised groups have stridently opposed views and the words they use to decry injustice are called unsafe by their opponents? Once this happens, the speech that one group needs to be protected is the same speech that the other group needs prohibited.

Perhaps it was inevitable that the internal contradictions of safe-speech norms would eventually create such problems. In Australia, like many countries, this was triggered by the October 7 Hamas atrocity and Israel’s unrelenting and brutal military response. Jews and Palestinians are both vulnerable minorities who face the well known bigotries of antisemitism and Islamophobia respectively. They both can reasonably demand the protection of safe-speech norms.

However, is each side interested in respecting the other’s right to such norms? Author and academic Randa Abdel-Fattah has reportedly alleged on social media, that if you are a Zionist, “you have no claim or right to cultural safety”. In turn, she says she has been harrassed and threatened over her views on the war in Gaza, and public institutions hosting her “have been targeted with letters defaming me and demanding I be disinvited”.

Perhaps the time has come to acknowledge that safe speech norms were never as straightforward or innocuous as they first appeared. They require a form of censorship that not only involves choosing political sides, but inevitably making fine-grained judgements between which opposing minority deserves protection at the expense of the other.

Indeed, safe speech norms may themselves be exclusionary. The US organisation “Third Way” advocates for moderation and centre left policies. In a recent memo it said research among focus groups had consistently found ordinary people interpreted key terms from progressive political language as alienating and arrogant.

According to Third Way, the term “safe space” (among others) communicates the sense that, “I’m more empathetic than you, and you are callous to hurting others’ feelings.”

With all this in mind, I find it hard to disagree with author Waleed Aly’s recent reflection that “in arenas dedicated to public debate, safety makes a poor organising principle”. Efforts to support and include marginalised voices are laudable. However, safe-speech norms are a deeply problematic – and perhaps ultimately contradictory – tool to use in pursuing that worthy goal.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

BY Hugh Breakey

Hugh is Deputy Director at Griffith University’s Institute for Ethics, Governance and Law. His research spans the philosophical subdisciplines of political philosophy, normative ethics, moral psychology, governance studies and applied philosophy. His works explore the ethical challenges arising in such diverse fields as peacekeeping, institutional governance, climate change, sustainable tourism, safety industries, private property, medicine, and international law, published in journals including The Philosophical Quarterly, The Modern Law Review and Political Studies. He has taught philosophy and ethics at the University of Queensland, Queensland University of Technology and Bond University. Since 2013, Hugh has served as President of the Australian Association for Professional and Applied Ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Reports

Politics + Human Rights

The Cloven Giant: Reclaiming Intrinsic Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

3 Questions, 2 jabs, 1 Millennial

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 25 JUN 2025

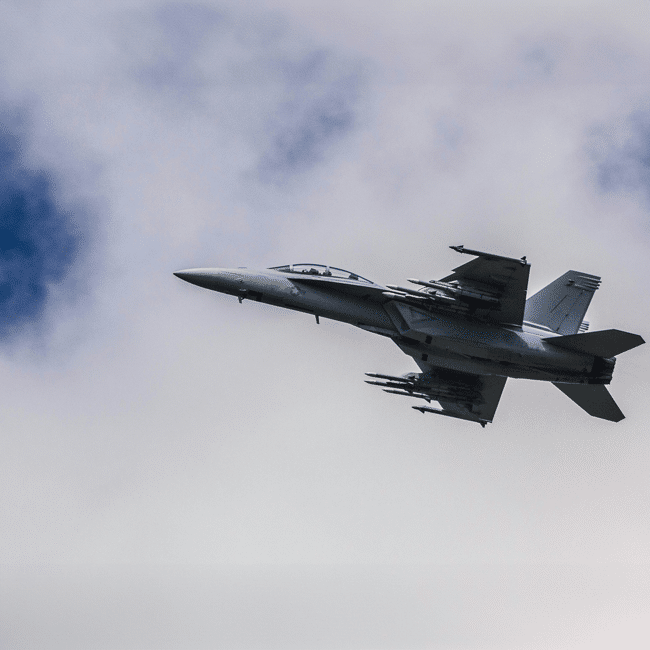

On 13 June 2025, Israel launched an unexpected series of attacks against military and nuclear facilities in Iran.

These attacks killed prominent politicians, military personal, and nuclear scientists, seriously damaging Iran’s air defences and its capacity to develop nuclear technology. A week later, the conflict escalated when the United States attacked heavily fortified nuclear facilities with some of its most powerful conventional weapons. President Trump claimed these strikes ‘obliterated’ Iran’s ability to develop nuclear technology.

The actions of Israel and the US have prompted widespread controversy, including questions about their legality, but I’m not interested in whether they had a legal right to strike Iran, but rather in whether these strikes were ethically justified.

Both Israel and the US have justified their attacks as self-defence. So let’s start with the claim that states have a moral right to self-defence. The realist tradition in international relations and international law often takes this right as read; a state has the right to self-defence qua being a state.

But this doesn’t really satisfy the question for someone interested in global ethics.

I, amongst others, ground the state’s right to self-defence in its status as the primary agent of justice with a responsibility to protect the individual human rights of its citizens against aggression. ‘Aggression’ here is limited to the application of direct military force. But what about circumstances where one hasn’t been attacked yet, but there is strong reason to believe that you will be?

This is where people who work in the ethics of war often employ the ‘domestic analogy’ and try to equate the state’s right of self-defence with an individual’s.

Let’s consider two test cases:

You get into an argument with your neighbour, they lose their temper and cock their fist to punch you. Would you be justified in throwing a punch first?

Second, you and your neighbour have been quarrelling. You hear rumours that they’ve been ‘talking trash’ about you and intimating that they are going to punch you when you least expect it. Would you be justified knocking on their door and punching them in the face?

In the case of the former, it seems ridiculous to say that you need to take the punch if you can stop it from coming, while the latter case seems unjustifiably aggressive. In one case the threat to you is imminent and unavoidable; the blow is coming unless you hit first. In the other case there is no imminent threat; it is in the future and there may be ways of de-escalating the conflict, such as a conciliatory fruit basket, or by calling the police.

If this analysis is correct, then a state may pre-empt an incoming attack when it has reliable intelligence that a hostile neighbour is mobilising for war, but it cannot do so based on the fear of a future attack that may be an unknown time away. In the case of Israel and Iran, it does not seem that Iran was on the cusp of attacking Israel, let alone attacking the United States. It’s analogous to the second test case, not the first.

However, the ‘domestic analogy’ does not seem to accurately encapsulate the ethical dilemmas that states face when considering the use of violence in self-defence.

The international system involves risks far beyond the type posed by personal self-defence, and the state has a responsibility to meet them as part of its duty to protect the rights of those within its borders

The question is whether in June 2025 Iran was able to put the basic rights of Israelis under sufficient threat to justify starting a war? The answer hinges on the prospect of Iran possessing – in the future – a relatively small arsenal of nuclear weapons. This would pose an existential threat to Israel in two ways. The first is their simple but immense destructive power; Israel is not a large country, so a few medium yield nuclear weapons would be enough to destroy its ability to defend itself and would kill potentially millions of non-combatants. Iran, however, does not need to use these weapons for them to be a threat. The second is that their existence would check Israel’s own (unacknowledged) nuclear arsenal and leave it vulnerable to a conventional war from its neighbours in which it would be at a possibly fatal disadvantage. It seems reasonable to say that a nuclear armed Iran would pose an existential threat to Israel’s ability to preserve the rights of those within its borders. However, it must be noted Iran certainly does not pose the same kind of existential threat to those within the USA.

This, however, does not settle the matter, because a key element of self-defence is that it can only occur when all other reasonable alternatives have been exhausted. It seems hard to imagine that this was the case. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action agreed in 2015 between Iran, the UN P5+1 and the European Union showed that there was at least a chance for a diplomatic solution to the Iran nuclear issue. This may be viewed as naïve by those who support Israel’s action, that it is the equivalent of hoping a fruit basket would appease the Mullahs, but it is not a wild utopian flight of fancy and these attacks are not without cost.

We must weigh the consequences of stretching the right of self-defence, because it is increasingly coming to look like a fig-leaf for a world where might makes right.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Making sense of our moral politics

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 JUN 2025

Want to understand politics better? Want to make sense of what the ‘other side’ is talking about? Then take a moment to reflect on your view of an ideal parent.

What kind of parent are you – either in reality or hypothetically? Do you want your children to build self-reliance, discipline, a strong work ethic and steel themselves to succeed in a dog-eat-dog world? Do you want them to respect their elders, which means acknowledging your authority, and expect them to be loyal to your family and community? Do you want them to learn to follow the rules, through punishment if necessary, knowing that too much coddling can leave them lazy or fragile?

Or do you want to nurture your children, so they feel cared for, cultivating a sense of empathy and mutual respect towards you and all other people? Do you want them to find fulfilment in their lives by exploring their world in a safe way, and discovering their place in it of their own accord, supported, but not directed, by you? Do you believe that strictness and inflexible rules can do more harm than good, so prefer to reward positive behaviour rather than threaten them with punishment?

Of course, few people will fall entirely into one category, but many people will feel a greater affinity with one of these visions over the other. This, according to American cognitive linguist, George Lakoff, is the basis of many of our political disagreements. This, he argues, is because many of us intuitively adopt a morally-laced metaphor of the government-as-family, with the state being the parents and the citizens the children, and we bring our preconceived notions of what a good family looks like and apply them to the government.

Lakoff argues that people who lean towards the first description of parenthood described above adopt a “Strict Father” metaphor of the family, and they tend to lean conservative or Right wing. Whereas people who lean towards the second metaphor adopt a “Nurturant Parent” metaphor of the family, and tend to lean more progressive or Left wing. And because these metaphors are so embedded in our understanding of the world, and so invisible to us, we don’t even realise that we see the world – and the role of government – in a very different light to many other people.

Strict Father

The Strict Father metaphor speaks to the importance of self-reliance, discipline and hard work, which is one reason why the Right often favours low taxation and low welfare spending. This is because taxation amounts to taking away your hard-earned money and giving it to someone who is lazy. Remember Joe Hockey’s famous “lifters and leaners” phrase?

The Right is also more wary of government regulation and protections – the so-called “nanny state” – because the Strict Father metaphor says we should take responsibility for our actions, and intervention by government bureaucrats robs us of our ability to make decisions for ourselves.

The Right is also more sceptical of environmental protections or action against climate change, because they subvert the natural order embedded in the Strict Father, which places humans above nature, and sees nature as a resource for us to exploit for our benefit. Climate action also looks to them like the government intervening in the market, preventing hard working mining and energy companies from giving us the resources and electricity we crave, and instead handing it over to environmentalists, who value trees more than people.

Implicit in the Strict Father view is the idea that the world is sometimes a dangerous place, that competition is inevitable, and there will be people who fail to cultivate the appropriate virtues of discipline and obedience to the rules. For this reason, the Right is less forgiving of crime, and often argues that those who commit serious crimes have demonstrated their moral weakness, and need to be held accountable. Thus it tends to favour more harsh punishments or locking them away, and writing them off, so they can’t cause any more harm.

Nurturant Parent

From the Nurturant Parent perspective, many of these Right-wing views are seen as either bizarre or perverse. The Nurturant Parent metaphor speaks to the need to care for others, stressing that everyone deserves a basic level of dignity and respect, irrespective of their circumstances.

It also acknowledges that success is not always about hard work, but often comes down to good fortune; there are many rich people who inherited their wealth and many hard working people who just scrape by, and many more who didn’t get the care and support they needed to flourish in life. For these reasons, the Left typically supports taxing the wealthy and redistributing that wealth via welfare programs, social housing, subsidised education and health care.

The Left also sees the government as having a responsibility to protect people from harm, such as through social programs that reduce crime, or regulations that prevent dodgy business practices or harmful products. Similarly, it believes that much crime is caused by disadvantage, but that people are inherently good if they’re given the right care and support. This is why it often supports things like rehabilitation programs or ‘harm minimisation,’ such as through drug injecting rooms, where drug users can be given the support they need to break their addiction rather than thrown in jail.

Implicit in the Nurturant Parent metaphor is that the world is generally a safe and beautiful place, and that we must respect and protect it. As such, the Left is more favourable towards environmental and climate policies, even if they mean that we might have to incur a cost ourselves, such as through higher prices.

Bridging the gap

Naturally, there’s a lot more to Lakoff’s theory than is described here, but the core point is that underneath our political views, there are deeper metaphors that unconsciously shape how we see the world.

Unless we understand our own moral worldview, including our assumptions about human nature, the family, the natural order or whether the world is an inherently fair place or not, then it’s difficult for us to understand the views of people on the other side of politics.

And, he argues, we should try to bridge that gap and engage with them constructively.

Part of Lakoff’s theory is that we absorb a metaphor of the family from our own experience, including our own upbringing and family life. That shapes how we make sense of things, like crime, the environment or even taxation policy. So we are already primed to be sympathetic towards some policies and sceptical of others. When we hear a politician speak, we intuitively pick up on their moral worldview, and find ourselves either agreeing or wondering how they could possibly say such outrageous things.

As such, we don’t start as entirely morally and political neutral beings, dispassionately and rationally assessing the various policies of different political parties. Rather, we’re primed to be responsive to one side more so than the other. As such, we don’t really choose whether to be Left or Right, we discover that we already are progressive or conservative, and then vote accordingly.

The difficulty comes when we engage in political conversation with people who hold a different metaphorical understanding of the world to our own. In these situations, we often talk across each other, debating the fairness of tax policy or expressing outrage at each others naivety around climate change, rather than digging deeper to reveal where the real point of difference occurs. And that point of difference could buried underneath multiple layers of metaphors or assumptions about the role of the government.

So, the next time you find yourself in a debate about tax policy, social housing, pill testing at music festivals or green energy, pause for a moment and perhaps ask a deeper question. Ask whether they think that success is due more to luck or hard work. Or ask whether the government has a responsibility to protect people from themselves. Or ask them which is more important: humanity or the rest of nature.

By pivoting to these deeper questions, you can start to reveal your respective moral worldviews, and see how they connect to your political views. You might not convince anyone to adopt your entrenched moral metaphors, but you might at least better understand why you each have the views you have – and you might not see political disagreement as a symptom of madness, and instead see it as a symptom of the inevitable variation in our understanding of the world. That won’t end your conversation, but it might start a new one that could prove very fruitful.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Power without restraint: juvenile justice in the Northern Territory

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

3 Questions, 2 jabs, 1 Millennial

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why compulsory voting undermines democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does ethical porn exist?

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 17 JUN 2025

The first two weeks of June 2025 have seen dramatic demonstrations in the United States against the Trump administration.

Against the backdrop of the President’s campaign of mass deportation, federal agents staged raids at a Home Depot and garment factories in Los Angeles. This triggered spontaneous and sometimes violent protests. Amidst television coverage giving the impression of widespread lawlessness, President Trump deployed some 4,000 members of the California National Guard and 700 U.S. marines – this was done despite the objections of Governor Gavin Newsom, LA Mayor Karen Bass, and the LA Police Department.

This is not unprecedented, but this was the first time troops were deployed on the streets of an American city since the 1992 LA Riots. It was also the first time since 1965 that the Guard was deployed over the objections of a state governor since Lydon Baines Johnson used them to protect citizens marching for civil rights in Alabama.

However, the context matters. These protests in LA in no way matched the scale of the LA Riots of forty years ago, which effectively shut down the city. In 2025 people were still travelling to work; Angelinos were posting photos of family fun from Disneyland. Secondly, Baines Johnson felt the necessity of nationalising the Guard in Alabama because of a widespread organised racist campaign of intimidation against civil rights activists. The was no comparable deprivation of rights in LA (possibly excepting the climate of fear created by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in the city’s Latino population).

The president has these powers, but they are expected to use them within the norms of ‘democratic restraint’ – they should only be used when there is great urgency. This was plainly not the case, considering the LA protests were effectively contained by the LAPD. Governor Newsom delivered a televised address in which he accused Trump of undermining the norms and institutions of democratic government in the United States and that California was being used to test a broader authoritarian power grab.

America is showing many of the signs of ‘democratic backsliding’. In How Democracies Die, political scientists at Harvard, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, have identified symptoms of a dying democracy. Many people think of military coups and tanks on the streets, but democracies often have slower, less spectacular deaths. Levitsky and Ziblatt show that elected leaders manage to neutralise and co-opt other branches of government; we have seen this with the collapse of moderate voices in the Republican Party and many express deep reservations about the Supreme Court’s independence after the genuinely shocking ruling for Trump v. United States which effectively placed the president above the law.

It is not just the institutional stress, but the growing incivility of civil society that is a concern, because institutions and constitutions do not defend themselves. They require people to unite to support common ways of life.

Americans are now deeply polarised. Political opponents are no longer competitors but enemies, or even traitors, to be silenced. It is impossible to disassociate this from the global pandemic of social media brain rot spreading disinformation, hatred, and conspiracy theories. The erosion of checks and balances coupled with the polarisation of civil society has enabled democratic norms to be slowly eroded to the extent that the President feels able to govern without traditional restraint.

So then what are the duties of citizens in a democracy that, if not dying, is looking terribly ill? This is not a partisan issue, but one that addresses the basic structure of society.

John Rawls wrote in A Theory of Justice, perhaps the greatest work of American political philosophy, that we all have a ‘natural duty’ to build and uphold just social institutions. This is because these institutions are the condition by which we can exercise our minimal autonomy. There is an assumption here that there is something intrinsically valuable about being able to think up and pursue one’s idea of a good life (so long as it doesn’t step on other people’s ability to do the same). You cannot do this if your choices are contingent on the will of a powerful person, whether it is your boss or the president. This is why the founders of the United States opted for a republic over a monarchy as the best guarantee of freedom from domination. It is a matter that should concern all Americans regardless of their political preferences.

Yet, it is a fragile system. On the last day of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Benjamin Franklin was asked by his friend Elizabeth Willing Powel whether the United States was to be a monarchy or a republic, to which he replied, “a republic if you can keep it”. It is easy to imagine states, especially ones as powerful as the United States, as permanent, but history is a graveyard of states, including many democracies.

What then are citizens to do in circumstances where democracy is failing? We find a suggestion in Franklin’s words. It is up to the people. What makes Franklin’s quote so interesting is that he addressed it to someone who could not even vote: a republic if you can keep it. The suggestion being that all people, even the disenfranchised, share this natural duty to preserve and uphold just institutions. The addressee of Franklin in the 21st century could well be the illegal immigrants who despite being demonised are an integral part of the American economy and society. The protests in LA may have been alarming, but they were a distress call from some of the most vulnerable people in the United States.

The question is how long can this continue? The problem with socialism, Oscar Wilde quipped, is that it takes up too many evenings. The same can be said about resisting authoritarianism. People need to live their lives, you can’t spend every waking hour protesting. Authoritarians know this and take their time eroding the guardrails and poisoning civil society. Trump with characteristic impatience is trying to do in months what took Viktor Orban and Hugo Chavez years to accomplish in much weaker democracies. The experience of the past two weeks may have chastened Trump, but it won’t stop him. The citizens of the United States are in a race against autocracy, but it is not a sprint. It is a marathon.

What every person in the United States, both citizens and non-citizens, must ask themselves is how best can I exercise my natural duty to support just institutions when they are under threat? It is an imperfect duty, meaning that it can be cashed out in numerous ways, but here are 3 suggestions:

- Vote for democracy: In instances of authoritarian capture people must put country above party. When a mainstream party, either of the left or the right, is infected by authoritarianism it is time to find a new political home until the fever breaks.

- Depolarise your politics: Democracies die when people lose what philosopher Michael Oakeshott called a ‘common tongue’ – the shared practices and customs that turns strangers into compatriots. Just as some people must make a new political home, others have a duty to welcome them. Your neighbour is not your enemy, even when you disagree.

- Take it to the streets: Vocal and visible rejection of authoritarianism by a united front reminds people that the decline of democracy is not inevitable; think of the contrast between the aptly named “No Kings” protests and Trump’s farcically shabby birthday parade. Public defiance is essential to maintain the health of civil society.

And it should also be said all of us observing from the sidelines must ask ourselves how we can exercise the same duty to prevent our democracies from going the same way.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

No justice, no peace in healing Trump’s America

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Paula McDonald 7 MAY 2025

US President Donald Trump declared earlier this year he would forge a “colour blind and merit-based society”.

His executive order was part of a broader policy directing the US military, federal agencies and other public institutions to abandon diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

Framing this as restoring fairness, neutrality and strength to American institutions, Trump argued DEI programs “discourage merit and leadership” and amounted to “race-based and sex-based discrimination”.

In Australia too, debates over gender quotas and “the war on woke” have repeatedly invoked meritocracy as a rallying cry against affirmative action.

The narrative of rewards going to the most qualified people is compelling. Yet decades of research show this is flawed. Far from being the great equaliser, an uncritical reliance on “merit” can perpetuate bias and inequality.

The myths of meritocracy

The merit rhetoric invokes the ideal of a neutral, objective system rewarding talent and effort, regardless of identity.

In theory, merit-based evaluations such as exams, performance reviews, employee recruitment processes and competitive bids, should be impartial.

In practice however, there are several myths associated with the notion of merit.

1. Merit is purely objective or unbiased

In the employment context for example, studies show that even so-called objective and standardised cognitive or aptitude tests can systematically favour men due to the type of questions asked.

Decision-makers may unknowingly redefine merit to fit whoever already belongs to a favoured group. A study of elite law firms, for example, found male applicants were rated as more qualified than identical resumes from women.

This is known as “plasticity of merit”, meaning the criteria of excellence can bend to preference, all while appearing objective.

Supposedly merit-based judgments can reflect unconscious bias, or comfort with candidates who fit a traditional mould. Over time, preference may be given to a particular type of candidate irrespective of their actual contribution. Privilege and prejudice can be baked into merit-based evaluations.

2. Merit can be separated from social and historical context

Meritocracy or the so-called meritocratic promise assumes a level playing field, where everyone competes under the same conditions.

In reality however, past inequalities shape present opportunities. What counts as merit is dynamic and socially shaped, not an eternal universal standard.

For example, during the second world war there was a shortage of male workers. Qualities women brought to jobs previously held by men such as capacity for teamwork were suddenly deemed meritorious. But these same qualities were downgraded when the men returned.

Merit is often defined in masculine terms. For example, physicality or hyper-competitive traits have long been seen as prerequisites for military service and policing.

This alignment of masculine norms with standards of merit has been termed “benchmark man”.

Science careers too were built in an era when women were largely excluded. They were predicated on long-hours work and total availability – requirements that clash with caregiving responsibilities. The result is women in STEM careers leave or are pushed out.

3. Outcomes are the result of personal choice or deficiencies, not structural barriers

Meritocracy carries a moral narrative: those at the top earned their place while those left behind didn’t measure up or chose not to compete.

Research shows, for example, that when women don’t advance, it’s explained as lifestyle choices, or they lack ambition, or have opted out to prioritise caregiving.

This narrative wilfully overlooks the structural constraints impacting choices. When a woman “chooses” a lower-paying, flexible job, it may be less about preference than inadequate social supports.

By accepting unequal outcomes as the natural result of individual choices, institutions can conveniently obscure disadvantage and discrimination and erase responsibility to correct inequities.

How the merit mandate undermines equality

Trump’s vision is to remove equity initiatives and programs that monitor or encourage fair hiring and promotion, cease training that alerts employees to hidden biases, and fire or reassign DEI staff.

This is conceptually flawed and will actually entrench the very biases and barriers that have kept institutions unequal.

In the military, for example – an area highlighted by Trump – leaders have recognised they need to foster more inclusive cultures.

For years, defence forces have grappled with sexual harassment, recruitment shortfalls and retention of skilled personnel. In Australia, the Australian Defence Force undertook major reviews to identify violent and sexist subcultures, understanding a more inclusive force is a more effective force.

Yet Trump’s order bars the Pentagon from even acknowledging historical sexism in the ranks.

Favouring the in-group

Removing equity measures under a banner of neutrality means hiring and promotion will increasingly rely on informal networks and subjective judgements. These can tilt in favour of the in-group – usually white, male and affluent.

DEI initiatives can increase representation of women, or people from diverse racial or cultural backgrounds, in an organisation or occupational group.

However, without challenging the norms of merit, or without broadening the definitions of talent and leadership, people in those groups may continue to feel like outsiders.

Australian experts and business leaders increasingly acknowledge objective merit is mythical.

Redefining merit

Fair rewards for effort can improve performance. However, we need to stop pitting merit against diversity. True fairness requires acknowledgement structural inequality exists and bias affects evaluations.

Organisations need to re-imagine merit in ways that work with inclusion, rather than against it. This includes refining hiring and promotion criteria to focus on competencies that are measurable and relevant.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

BY Paula McDonald

Paula McDonald is Professor of work and organisation and Director of the Work/Industry Futures Research Program in the QUT Business School. Prior to an academic career, Paula held clinical and research roles in health sector settings including child and adolescent psychiatry, medical education, primary care and public health. She is a registered psychologist with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

‘Woke’ companies: Do they really mean what they say?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why Anzac Day’s soft power is so important to social cohesion

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 29 APR 2025

Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks, Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Greta Thunberg, Vincent Lingiari, Malala Yousafzai.

For most, these names, and many more, evoke a sense of inspiration. They represent decades and centuries of steadfast moral conviction in the face of overwhelming national and global pressure.

Rosa Parks, risking the limited freedom she was afforded in 1955 America, refused to acquiesce to the transit segregation of the time and sparked an unprecedented boycott led by Martin Luther King Jr.

Frederick Douglass, risking his uncommon position of freedom and power as a Black man in pre-civil rights America, used his standing and skills to advocate for women’s suffrage.

There have always been people who have acted for what they think is right regardless of the risk to themselves.

This is moral courage. The ability to stand by our values and principles, even when it’s uncomfortable or risky.

Examples of this often seem to come in the form of very public declarations of moral conviction, potentially convincing us that this is the sort of platform we need to be truly morally courageous.

But we would be mistaken.

Speaking up doesn’t always mean speaking out

Having the courage to stand by our moral convictions does sometimes mean speaking out in public ways like protesting the government, but for most people, opportunities to speak up manifest in much smaller and more common ways almost every day.

This could look like speaking up for someone in front of your boss, questioning a bully at school, challenging a teacher you think has been unfair, preventing someone on the street from being harassed or even asking someone to pick up their litter.

In each case, an everyday occurrence forces us to confront discomfort, and potentially danger or loss, to live out our values and ideals. Do we have the courage to choose loyalty over comfort? Honesty over security? Justice over personal gain?

The truth is that sometimes we don’t.

Sometimes we fail to take responsibility for our own inaction. Nothing shows this better than the bystander effect: functionally the direct opposite to moral courage, the bystander effect is a social phenomenon where individuals in group or public settings fail to act because of the presence of others. Being surrounded by people causes many of us to offload responsibility to those around us, thinking: “Someone else will handle it.”

This is where another kind of moral courage comes into play: the ability to reflect on ourselves. While it’s important to learn how and when to speak up, some internal work is often needed to get there.

Self-reflection is often underestimated. But it’s one of the hardest aspects of moral courage: the willingness to confront and interrogate our own thoughts, habits, and actions.

If someone says something that makes you uncomfortable, the first step of moral courage is acknowledging your discomfort. All too often, discomfort causes us to disengage, even when no one else is around to pass responsibility onto. Rather than reckon with a situation or person who is challenging our values or principles, we curl up into our shells and hope the moment passes.

This is because moral courage can be – it takes time and practice to build the habits and confidence to tolerate uncomfortable situations. And it takes even more time and practice to prioritise what we think is right with friends, family and colleagues instead of avoiding confrontation in relationships that are already often complicated.

It can get even more complicated once we consider all of our options because sometimes the right ways to act aren’t obvious. Sometimes, the morally courageous thing to do is actually to be silent, or to walk away, or to wait for a better opportunity to address the issue. These options can feel, in the moment, akin to giving up or letting someone else ‘win’ the interaction. But that is the true test of moral courage – being able to see the moral end goal and push through discomfort or challenge to get there.

The courage to be wrong

The flipside to self-reflection is the ability to recognise, acknowledge and reflect with grace when someone speaks up against us.

It’s hard to be told that we’re wrong. It’s even harder to avoid immediately placing walls in our own defence. Overcoming that is the stuff of moral courage too – not just being able to confront others, but being able to confront ourselves, to question our understanding of something, our actions or our beliefs when we are challenged by others.

Whether these changes are worldview-altering, or simply a swapping of word choice to reflect your respect for others, the important thing is that we learn to sit with discomfort and listen. Listen to criticism but also listen to our own thoughts and figure out why our defences are up.

Because in the end, moral courage isn’t just about bold public stands. It’s about showing up—in big moments and more mundane ones—for what’s right. And that begins with the courage to face ourselves.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Trying to make sense of senseless acts of violence is a natural response – but not always the best one

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why certain things shouldn’t be “owned”

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What happens when the progressive idea of cultural ‘safety’ turns on itself?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Lies corrupt democracy

One of the most potent threats to democracies is that their elections will be corrupted by lies.

No matter how attenuated in practice, the defining feature of democracies is that the exercise of power is conditional upon the consent of the governed. Consent confers authority. Without consent the exercise of power depends not on democratic legitimacy but instead on the brute force of the autocrat.

For consent to be meaningful, it must be informed. And nothing can be ‘informed’ if it is based on falsehood routinely peddled by those who deal in misinformation and disinformation.

There is nothing new in this. Since antiquity, citizens have always been susceptible to manipulation to skew political outcomes. The difference, today, lies in the speed at which a lie can spread and the breadth of the audience it can reach in an instant. There are also so few individuals or institutions who are trusted to guard and uphold the truth.

Ideally, we might hope that politicians would offer the first line of defence of truth. After all, they have a duty to prioritise the public interest ahead of personal or party interests. Few aspects of the public interest are as important and as obvious as the need to assure the integrity of our democratic elections. Politicians who lie fundamentally undermine the integrity – and therefore the legitimacy – of our elections. In doing so, they betray the public interest.

Despite this, Australia imposes very few penalties on politicians or parties who deliberately lie. This reluctance to punish falsehood is, in part, due to an equal commitment to free speech. We are right to be cautious about introducing measures that restrict free speech for fear of being punished for saying the ‘wrong thing’. It may also be the case that our legislators have a shared interest in not creating a ‘rod’ for their own backs – especially when they can see political advantage in being ‘economical with the truth’.

So, we largely depend on politicians to regulate themselves – with the apolitical Australian Electoral Commission left to manage the worst cases of misinformation and disinformation.

The good news is that politicians are mostly truthful. The bad news is that there are other actors, in the political space, who deliberately seek to manipulate the electorate by manufacturing and propagating misinformation and disinformation. Some of those responsible are state actors who seek to harm countries like Australia by creating or exploiting divisions. They are skilled at using our open information systems as vectors to create states of alarm, confusion and uncertainty – all of which introduces structural weakness and a reduced ability to mount a strong, united response to challenges. Other actors use misinformation and disinformation to advance their ideological or economic interests – by tilting an election in favour of their preferred outcome.

Unfortunately, this kind of interference is now common. Paradoxically, the more it is exposed, the greater the loss of trust in the information presented to us. And that suits the enemies of democracy very well. When a picture or video can be manipulated to the point where you cannot distinguish reality from fiction; when the voice on a phone call is a ‘clone’ based on a thirty second clip – yet is entirely credible; when nothing can be guaranteed to be what it seems to be – how, then, does a voter ever know that they are making an informed decision?

That problem has been solved by financial markets (which also depend on informed decision making) through the profession of auditing. Auditors belong to the profession of accounting. As such, they stand adjacent to the world of the ‘market’ which formally approves the pursuit of self-interest in the satisfaction of the wants of others. The profession of accounting is made up of people who freely choose to abandon the pursuit of self-interest in service of the public interest and a higher ‘good’ – namely the truth.

The role that accountants play in markets is mirrored by the role that journalists are supposed to play in politics – and especially in democracies. Unfortunately, just as some merchants can be relied upon to resort to deception in the pursuit of profits, so can some politicians be relied upon to do the same in the pursuit of victory. Professional journalists are supposed to help protect society from that risk – which is why they are so often lauded as the ‘fourth estate’.

In order to ensure the integrity of our democracy, we need politicians who can be trusted not to lie (even when it advantages them). We need regulators with increased power to identify, curb and punish the activities of those who lie and deceive. We need journalists who place their commitment to the disinterested pursuit of truth ahead of personal or commercial self-interest. We need to be able to distinguish between those who abuse the title ‘journalist’ as false cover and those who genuinely deserve to be trusted. Finally, we need to rally behind and reward media outlets that employ truth-tellers and cease engaging with those who treat the truth as a mere ‘optional extra’.

Fortunately, there are some amongst the political class who are taking steps to encourage truth in politics. A recent initiative, The Ethical Political Advertising Code (EPAC) affords an opportunity for people seeking election to make a public commitment to ‘truth in political advertising’.

Sponsored by Zali Steggall MP, this is a cause that should be apolitical in character – hopefully enjoying the support of any person who cares about the character and quality of our democracy. But this is not just a matter for politicians. It is also something that affects us all.

That is our test as citizens – to choose truth over mere entertainment, to prefer fact to falsehoods that pander to our prejudices.

With so much now at stake in the world, this is a test we must pass. But will we?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Sportswashing: How money and politics are corrupting sport

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Trump and the failure of the Grand Bargain

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Luke Zaphir 14 APR 2025

In Australia, we have no formalised method of teaching people about politics, voting and elections. Most people vote the same way as their parents in their first elections, and won’t receive any more education beyond how-to-vote cards and electoral ads.

People under the age of 25 make up about 10% of all voters – that’s about ten thousand per electorate. They’re the most underrepresented group in political discourse and in elections. Not only that but young people will have to live with the consequences of these policies far longer than any other demographic.

Given that some elections come down to only a few hundred votes, the way we vote really does matter.

Our votes matter beyond the current election – they affect future elections too. The Australian Electoral Commission provides funding for every candidate or group that receives more than 4% of first preference votes. This means that even small groups can become big factors, influencing future elections and swaying the balance of power in parliament.

Finally, democracy works because it’s about communicating our needs and visions of the future. The major parties pay attention to how and why people vote. The Labor and Liberal parties have issues that they care about but others they overlook. A vote can shift the way the policy platforms of the major parties to discuss the issues we care about.

Here is a practical guide to critically think about your vote.

Step 1: Ignore the hype

Political parties are really good at demonising each other. They’ll accuse each other of being craven, lying, baby eating monsters. None of this is useful information. Almost every piece of political messaging from every party is propaganda designed to get your vote. They’ll frame the issues in terms of economics, jobs, the environment or tradition. This anchors our thinking in a way that is unhelpful for choosing a candidate, making it difficult to consider nuance and complexity.

Step 2: Value democratic integrity

Our democracy cannot function if our representatives are known liars, are demonstrably corrupt, or engage in unscrupulous mudslinging against other candidates. Everyone believes they are morally correct but if the candidate spends their time hurling insults, they’re actively toxic to our democracy. If the candidate is willing to say or do anything to get elected, they can’t be trusted to further the public good and should come last on the ballot.

Our democracy only functions if its processes are open, fair and honest. Recent changes to the ways political candidates are allowed to fundraise means that it may be easier for incumbents to stay in power, and harder for newcomers to challenge them. It’s worth looking into whether your member of parliament supported these changes, or aims for a level playing field.

Step 3: Think about your values

The most fundamental part of knowing who to vote for is knowing what your values are. There are an endless number of beliefs that we might hold. We might believe in universalism and benevolence (welfare for all, tolerance and understanding), which lead to policies like a universal basic income, investment in public broadcasters like the ABC, and increasing foreign aid. Values such as self-direction and achievement are more important to us (pursuing and gaining personal success) lead to policies that minimise taxation and deregulation. Voting against same-sex marriage or changes to the constitution to include First Peoples are examples of valuing tradition, whereas policies that block foreign investment or advocate turning back asylum seeker boats prioritise security.

There’s no such thing as ‘having bad values’, but it’s important to know what we believe, why we believe it, and prioritise these when it comes to elections. Ask yourself how important each of your principles and goals are in turn, and if your vote will move you further towards them.

Step 4: Think about what you’d like for the country

Now that you understand your values, think about how they inform the kind of country you want Australia to become. Political parties offer massive packages of policies containing aspects we agree with or may not like. Vote compasses can be useful at this point in this task – they have specific policy directions that allow us to precisely target what we would want to achieve in the country. This is an important step because we might agree with a party’s stated views but if their policies don’t match up, we’re not going to be represented well.

It’s common to agree with only part of a party’s political package. This is why we need to learn about all the candidates’ parties, their aims, and which best aligns with our own views. Preferential voting is a way of creating an order of best fit – with your number 1 preference going to the party that most aligns with your views, and each subsequent preference being the next best fit. The party that least represents your views should get your last preference.

Step 5: Learn about the parties

Labor and the Liberals are the most powerful and oldest parties in Australia. They aren’t exactly the same platforms as they once were, which is why second hand information from others may be out of date. The Greens are also a significant party and often hold the balance of power in the Legislative Assembly. There are many other parties that will be in your division and it’s worth looking into what they value and what their aim is specifically. There are many parties that focus on single issues that are important to them.

Step 6: Discover the candidates’ credentials and goals

The Australian Electoral Commission provides information about all currently enrolled candidates. Additionally, blogs like The Tally Room track candidates for each division and provide links to all of their personal websites.

A person’s qualifications and work history will tell us a bit about who someone is. Do they own a business? Ran a not-for-profit? Have they been a teacher or academic or front line retail worker? Have they been bankrupt? This is useful for telling us what kind of person we’re voting for and how they think.

Another important aspect is how clearly they’ve articulated their goals. Every party is in favour of good economic management, green technology and low unemployment figures. What matters is which they prioritise given the current context. It’s also worth considering what they plan in the long term – do they have a vision for Australia in 20 years? In 50? A party that only sees the future one electoral cycle ahead is one that will make short sighted decisions.

Lastly, if they can’t concisely say that they aim to enact a specific law or to increase a certain tax, we have reason to question their competence. A candidate can talk about the value of freedom all they want – without a stated goal, they either haven’t thought about it or they’re dog whistling.

Step 7: Judge the incumbent’s track record

The member of parliament for your division has a higher burden for gaining re-election because they have to defend their record. What have they done so far? What have they accomplished? How have they voted in the House of Representatives or Senate? Hansard is the official record of parliamentary speeches and votes. They Vote for You is a not-for-profit independent non-partisan organisation which tracks how the current member of parliament has voted (from Hansard). This includes their attendance (how often they do their job), and what they vote consistently for and against. This is particularly useful for us if we care about a specific issue – we can discover if the sitting member supports or votes against it in parliament.

A final thought

There are no wrong choices except those which are made with inaccurate information. This guide will take less than an hour and that’s not much to be conscientious about your vote once every three years. Democracy isn’t just about voting. It is in our civil discourse itself and how we share our perspectives.