The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 28 OCT 2022

More sporting and arts bodies are thinking hard about whom they’re willing to accept funding or sponsorship deals from. But how are they to weigh the competing interests of their organisations, players and artists, and the general public?

When First Nations netballer Donnell Wallam spoke out to seek an exemption from wearing the logo of major sponsor, Hancock Prospecting, she sparked a national conversation around the role of sponsorship in sport, and what voice players ought to have in choosing which sponsors they accept and which logos they wear on their jerseys.

In the case of Wallam, Netball Australia had just signed at $15 million sponsorship deal with Hancock Prospecting, run by Gina Reinhart, the daughter of the founder, Lang Hancock. This was seen by Netball Australia as a much-needed injection of funding to compensate for the multi-million dollar debt the sport’s governing body had accrued during years of COVID-19 lockdowns and travel restrictions.

But Wallam saw something else. Front of mind for her were comments made by Lang Hancock in a 1984 documentary where he advocated that any Indigenous peoples who had not been assimilated ought to be rounded up and sterilised.

After a weeks of debate and negotiation, Hancock Prospecting withdrew from the sponsorship deal, offering short-term funding until the sporting body could find a new sponsor. In a parting shot, the company released a statement saying “it is unnecessary for sports organisations to be used as the vehicle for social or political causes” and that “there are more targeted and genuine ways to progress social or political causes without virtue signalling or for self-publicity”.

However, there is good reason to believe that Wallam and Netball Australia’s actions were more than a ‘virtue signalling’ exercise, but rather part of an increasing trend of sporting bodies and other organisations thinking carefully about whom they accept funding from and which industries they are willing to be associated with.

In recent times, a group of high-profile Freemantle Dockers players and supporters have called for the club to drop oil and gas company Woodside Energy over concerns about climate change. Australian test cricket captain, Pat Cummins, has also declined to appear in any promotional material for Cricket Australia sponsor Alinta Energy, a move backed by former Wallabies captain, and ACT senator, David Pockock.

Arts organisations have been wrestling with similar questions for some years, prompted by incidents such as the Sydney Biennale in 2014 severing its relationship with Transfield, which operated immigration detention centres, after an artist boycott, and the Sydney Festival in 2022 deciding to suspend all funding agreements with foreign governments after an artist boycott due to a sponsorship agreement with the Israeli embassy.

So how should businesses and other organisations, including sporting and arts bodies, decide whom to accept money from? How should they weigh the interests of players, artists, supporters and the wider public with their financial needs and their organisational values? How do they avoid making rash decisions that themselves trigger a backlash?

How to decide

These are difficult questions to answer, which is why The Ethics Centre has developed a specialised decision-making approach, Decision Lab, to help businesses and other organisations navigate difficult ethical terrain and make better decisions.

The Decision Lab process is designed to bring implicit thinking and buried assumptions to the surface so they can be discussed and debated in the open, providing tools to evaluate decisions before they are committed to so that key considerations are not overlooked.

The foundation of the Decision Lab is gaining a deeper understanding of the organisation’s foundational purpose for being, its values and the principles that guide it. These ought to be the starting point of any big decision, but published mission statements and codes of ethics are often overwhelmed in practice by the organisation’s Shadow Values, which are woven into the unspoken culture. The Decision Lab seeks to bring these values to the surface so they can scrutinised, revised and applied as needed.

The Decision Lab also employs a decision-making model that follows a step-by-step process that covers all the elements necessary to make a comprehensive and defendable decision. This includes factoring in what is known, unknown and assumed, such as how the funding might positively or negatively impact the community, or how it might help to promote a cause that the organisation doesn’t believe in.

It also considers the impacts of a decision on all stakeholders, including the wider community and future generations, and not just those who are closely connected to the decision.

The process also teases out the specific clash of values and principles around a particular decision, which is useful because many dilemmas follow a similar form. So if an organisation has an existing solution to one problem, it might find it already has the necessary reasoning and jusification to respond to another situation that follows the same pattern.

Finally, the Decision Lab applies a ‘no regrets’ test to ensure that nothing has been overlooked. This helps avoid situations where a decision is made yet it runs into problems that could have been forseen if the organisation had applied a more rigorous decision making process, such as a counter-backlash by other segments of their community.

The Decision Lab supports the executive team to align their decisions with the organisation’s ethics framework and helps to communicate with all the key stakeholders the rationale for decisions. By applying a more rigorous decision-making process, an organisation is better able to balance competing interests, resulting in more ethical decisions aligned to its purpose, values and principles that will hold up in the face of scrutiny.

The Ethics Centre is a thought leader in assessing organisational cultural health and building leadership capability to make good ethical decisions. To find our more about Decision Lab, or arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Image by Nigel Owen / Action Plus Sports Images / Alamy

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Feeling rules: Emotional scripts in the workplace

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Getting the job done is not nearly enough

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Explainer: Getting to know Richard Branson’s B Team

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why we need land tax, explained by Monopoly

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Should corporate Australia have a voice?

Should corporate Australia have a voice?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Alliance Emma Elsworthy 24 OCT 2022

The Albanese government is preparing for the fight of its life to convince Australians an Indigenous advisory body, known as the Voice to Parliament, should receive a simple “yes” in a referendum due to take place in October 2023. But whether the Australian business community should abstain or pick a side in the campaign is a little more complex.

Some business leaders have already openly backed the Voice. CSL’s Brian McNamee called embedding Indigenous people into our Constitution for the first time nothing less than a “greater need” for the nation. Lendlease’s CEO Tony Lombardo said his company was “right behind” the Uluru Statement from the Heart and had urged his staff to think deeply about the constitutional amendment and the benefits for our First Nations peoples and the broader Australian community.

But business taking a public stance wasn’t always so. In decades prior, corporations strained to stay impartial by not weighing in on heavily politicised or social issues, seeing it as a polarising death wish amid the cohort of its customers who may err to the other side (though big political donations were a telling exception to this unofficial rule).

But the rise of social media in the era where progressive politics has assembled earth-shaking movements like Black Lives Matter, #MeToo and the fight to stop climate change has created a corporate environment where it’s not only expected companies to weigh in on big-ticket items – it’s great for business if they do.

Nearly 80% of Australians believe big brands should use their power to make an impact for real-world change on social and workplace inequality, according to research conducted by Nine and cultural insights agency FiftyFive5 – and it can turn into big bucks for corporations.

When beloved ice cream brand Ben & Jerry’s, which accounts for 3% of the worldwide market, announced in 2021 that it was stopping sales “in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT)” because it was “inconsistent with our values”, Ben & Jerry’s sales saw a 9% yearly growth (though frustrated parent company Unilever denied the two were linked).

And it seems the Albanese government is all but expecting corporate Australia to take a stance on the Voice one way or another. In 2019, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese declared to the Business Council of Australia that business should feel free to speak out on social issues that align with their values.

“The most successful businesses operate in ways that reflect the values of their employees and their customers,” the then-opposition leader said.

“You are not just takers of profit – you see yourselves as part of the community.”

Albanese’s comments followed a heated speech from Scott Morrison’s assistant minister Ben Morton declaring chief executives “too often succumb or pander to similar pressures from noisy, highly orchestrated campaigns of elites typified by groups such as GetUp or activist shareholders”, foreshadowing the Teal uprising in the May federal election.

But corporate activism doesn’t have to mean go woke or go broke – as long as a company is seen as being consistent with its long-held values, a customer base or wider community will accept a more conservative position on a social or political issue too, as Daniel Korschun and N. Craig Smith write for the Harvard Business Review.

“People are surprisingly accepting of a company’s political viewpoints as long as they believe that it is being forthright,” the pair write.

“When a company makes sudden changes to its procedures or identity, it can raise red flags, especially with consumers for whom reliability is essential.”

To this end, a corporate in Australia that openly supports the “Yes” campaign for the Voice to Parliament may first quietly seek to understand the company’s own history with Indigenous Australia to avoid damning accusations of “woke washing” from the public.

Director of The Ethics Alliance, Cris Parker suggests leaders seek the answer to questions like: how many First Nations people are employed at the organisation, and is it far less than the 3% in wider society? Has the organisation proactively supported these staff, providing a culturally sensitive environment that recognises Indigenous rights?

“Basically, are you living the values of whatever social issue internally that you are considering speaking out about publicly?” Parker says.

For instance, when Nike released its “Dream Crazy” campaign to support Colin Kaepernick taking a knee during the American national anthem to protest police brutality, some were quick to point out Nike’s own reputation for using the sweatshop labour of people of colour abroad in countries like China.

Further, hot-button issues can polarise people not only within the customer base but within the work culture. Parker suggests that a corporation may add the most value during this time by fostering an environment where people can respectfully share ideas and reflect on issues together.

“Perhaps standing on a pedestal isn’t the approach which will have the greatest impact. Perhaps the impact of corporations is to demonstrate the ability to create spaces where there can be civil and informed debate – not to provide the decision or choice but to impartially inform employees and encourage intelligent enquiry,” Parker continues.

“When organisations shift to a specific advocacy position, particularly if it’s about members of our community, they risk disempowering those members and really we should be supporting self-determination.”

The best way to do this? Go back to the work culture, Parker suggests, and seek to use organisational values to create space for discussion, where crucially, everyone can feel included in the conversation.

Image by Matt Hrkac

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The erosion of public trust

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY Emma Elsworthy

Before joining Crikey in 2021 as a journalist and newsletter editor, Emma was a breaking news reporter in the ABC’s Sydney newsroom, a journalist for BBC Australia, and a journalist within Fairfax Media’s regional network. She was part of a team awarded a Walkley for coverage of the 2019-2020 bushfire crisis, and won the Australian Press Council prize in 2013.

Big Thinker: Kimberlé Crenshaw

Kimberlé Crenshaw (1959-present) is one of the most influential feminist philosophers of our time. She is known for her advocacy for American civil rights, being a leading scholar of critical race theory, and pioneering what we now know as the third wave of feminism.

Crenshaw was born in Ohio, US in 1959. As a child, she grew up through the US civil rights and second wave feminist movements, both which occured throughout the 1960s and 70s. This time of revolutionary movements towards equality influenced how Crenshaw was raised.

“My mom was a little bit more radical and confrontational and my father was a little bit more Martin Luther King and ‘find common ground’. Which is probably why there are strains of both of those in my work.”

In 1984, Crenshaw graduated from Harvard Law School. At this time, there was only one woman and one Black professor of the 60 who were tenured. She is now a tenured professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and splits her time there with the Columbia School of Law in NYC.

Where do race and gender meet?

“I argue that Black women are sometimes excluded from feminist theory and antiracist policy discourse because both are predicated on a discrete set of experiences that often does not accurately reflect the interaction of race and gender.”

Crenshaw is most notable for coining the term “intersectionality,” which refers to the idea that when someone has multiple identities, it causes them to experience different and compounded forms of oppression. Rather than oppression being additive across multiple identities, intersectionality tells us that the experience of oppression will be multiplied. For example, a Black woman will experience discrimination because she is Black, because she is a woman, and also because she is a Black woman – which is a different kind of discrimination altogether.

“Because the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that does not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the particular manner in which Black women are subordinated.”

In the academic world, the term intersectionality debuted in Crenshaw’s 1989 paper Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. Many scholars would say that the publishing of this paper catalysed the third wave of feminism, which is characterised by advocates demanding a more wholistic type of equality for people of all genders, races, socioeconomic backgrounds, abilities, ages, and in all countries.

Two years after the paper was published, Crenshaw assisted Professor Anita Hill’s legal team during Judge Clarence Thomas’s confirmation hearing to the US Supreme Court in October of 1991. In an interview with the Guardian, she reflects that the experience cemented the need for an intersectional theory of social justice. It was clear that “race was playing a role in making some women vulnerable to heightened patterns of sexual abuse [a]nd … anti-racism wasn’t very good at dealing with that issue.”

Intersectionality finally appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary in 2015, where it is defined as “the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.”

A founder of critical race theory

“You can’t fix a problem you can’t name.”

Crenshaw has also spent a large part of her academic career developing and writing about what is now known as critical race theory. In its purest form, critical race theory is a 40-year-old academic framework that concerns itself with defining and understanding the plethora of ways that race impacts American institutions and systems, and how American institutions and culture uphold racist ideals. Crenshaw’s own definition, however, is more of a verb than a noun. For her, critical race theory is “a way of seeing, attending to, accounting for, tracing and analysing the ways that race is produced.”

One of the big cultural issues in the 21st century in America has been whether to teach critical race theory in public schools across the country. Parents and politicians across America have fought to remove what they think critical race theory is out of children’s education. They have argued that CRT is racist and teaches kids to “hate their own country.” Crenshaw now says she sees her work “as talking back against those who would normalise and neutralise intolerable conditions in our lives.”

Where to now?

Crenshaw continues to educate and inspire the next generation by teaching classes in Advanced Critical Race Theory, Civil Rights, Intersectional Perspectives on Race, Gender and the Criminalization of Women & Girls, and Race, Law and Representation at UCLA. At Columbia, she continues to work on the AAPF and through the forum, co-authored a paper in 2015 with Andrea Richie entitled Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women.

She regularly writes for a number of publications and provides commentary for the new outlets MSNBC and NPR. Crenshaw also hosts her own podcast Intersectionality Matters.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Australian debate about asylum seekers and refugees

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Nick Jarvis 14 OCT 2022

The world’s biggest social media platform’s slide into a cesspit of fake news, clickbait and shouty trolling was no accident.

“Facebook gives the most reach to the most extreme ideas. They didn’t set out to do it, but they made a whole bunch of individual choices for business reasons,” Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen said.

In her Festival of Dangerous Ideas talk Unmasking Facebook, data engineer Haugen explained that back in Facebook’s halcyon days of 2008, when it actually was about your family and friends, your personal circle wasn’t making enough content to keep you regularly engaged on the platform. To encourage more screentime, Facebook introduced Pages and Groups and started pushing them on its users, even adding people automatically if they interacted with content. Naturally, the more out-there groups became the more popular ones – in 2016, 65% of people who joined neo-Nazi groups in Germany joined because Facebook suggested them.

By 2019 (if not earlier), 60% of all content that people saw on Facebook was from their Groups, pushing out legitimate news sources, bi-partisan political parties, non-profits, small businesses and other pages that didn’t pay to promote their posts. Haugen estimates content from Groups is now 85% of Facebook.

I was working for an online publisher between 2013 and 2016, and our traffic was entirely at the will of the Facebook algorithm. Some weeks we’d be prominent in people’s feeds and get great traffic, other weeks it would change without warning and our traffic and revenue would drop to nothing. By 2016, the situation had gotten so bad that I was made redundant and in 2018 the website folded entirely and disappeared from the internet.

Personal grievances aside, Facebook has also had sinister implications for democracy and impacts on genocide, as Haugen reminds us. The 2016 Trump election exposed serious privacy deficits at Facebook when 87 million users had their data leaked to Cambridge Analytica for targeted pro-Trump political advertising. Enterprising Macedonian fake news writers exploited the carousel recommended link function to make US$40 million pumping out insane – and highly clickable – alt-right conspiracy theories that undoubtedly played a part in helping Trump into the White House – along with the hackers spreading anti-Clinton hate from the Glavset in St Petersburg.

Worse, the Myanmar government sent military officials to Russia to learn to use online propaganda techniques for their genocide of the Muslim Rohingya from 2016 onwards, flooding Facebook with vitriolic anti-Rohingya misinformation and inciting violence against them. As The Guardian reported, around that time Facebook had only two Burmese-speaking content moderators. Facebook has also been blamed for “supercharging hate speech and inciting ethnic violence” (Vice) in Ethiopia over the past two years, with engagement-based ranking pushing the most extreme content to the top and English-first content moderation systems being no match for linguistically diverse environments where Facebook is the internet.

There are design tools that can drive down the spread of misinformation, like forcing people to click on an article before they blindly share it and putting up a barrier between fourth person plus sharers, so they must copy and paste content before they can share or react to it. These have the same efficacy at preventing misinformation spread as third-party fact-checkers and work multi-lingually, Haugen said, and we can mobilise as nations and customers to put pressure on companies to implement them.

But the best thing we can do is insist on having humans involved in the decision-making process about where to focus our attention, because AI and computers will always automatically opt for the most extreme content that gets the most clicks and eyeballs.

For technology writer Kevin Roose, though, in his talk Caught in a Web, we are already surrounded by artificial intelligence and algorithms, and they’re only going to get smarter, more sophisticated, and more deeply entrenched.

70% of our time on YouTube is now spent watching videos suggested by recommendation engines, and 30% of Amazon page views are from recommendations. We let Netflix preference shows for us, Spotify curate radio for us, Google Maps tell us which way to drive or walk, and with the Internet of Things, smart fridges even order milk and eggs for us before we know we need them.

A commercialised tool one AI researcher told Roose about called pedestrian reidentification can identify you from multiple CCTV feeds, put that together with your phone’s location data and bank transactions and figure out to serve you an ad for banana bread as you’re getting off the train and walking towards your favourite café.

And in news that will horrify but not surprise journalists, Roose said we’re entering a new age of ubiquitous synthetic media, in which articles written by machines will be hyper personalised at point of click for each reader by crawling your social media profiles.

After 125 years of the reign of ‘all the news that’s fit to print’, we’re now entering the era of “all the news that’s dynamically generated and personalised by machines to achieve business objectives.”

How can we fight back and resist this seemingly inevitable drift towards automation, surveillance and passivity? Roose highlights three things to do:

Quoting Socrates, Know Thyself. Know your own preferences and whether you’re choosing something because you like it or because the algorithm suggested it to you.

Resist Machine Drift – this is where we unconsciously hand over more and more of our decisions to machines, and “it’s the first step in losing our autonomy.” He recommends “preference mapping” – writing down a list of all your choices in a day, from what you ate or listened to, to what route you took to work. Did you make the decisions, or did an app help you?

Invest in Humanity. By this he means investing time in improving our deeply human skills that computers aren’t good at, like moral courage, empathy and divergent, creative thinking.

Roose is optimistic in this regard – as AI gets better at understanding us and insinuating its way into our lives, he thinks we’re going to see a renewed reverence for humanism and the things machines can’t do. That means more appreciation for the ‘soft’ skills of health care workers, teachers, therapists, and even an artisanal journalism movement written by humans.

I can’t be quite as optimistic as Roose – these soft skills have never been highly valued in capitalism and I can’t see it changing (I really hope I’m wrong), but I do agree with him that each new generation of social media app (e.g. Tik Tok and BeReal), in the global West at least, will be less toxic than the one before it, driven by the demands of Millennials and Generation Z, and those to come.

Eventually, this generational movement away from the legacy social media platforms, which have become infected with toxicity, will cause them to either collapse or completely reshape their business model to be like newer apps if they’re going to keep operating in fragile countries and emerging economies.

And that’s one reason to not let the machines win.

Visit FODI on demand for more provocative ideas, articles, podcasts and videos.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

License to misbehave: The ethics of virtual gaming

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

On plagiarism, fairness and AI

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Politics + Human Rights

How to have a difficult conversation about war

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

BY Nick Jarvis

Nick Jarvis is a Sydney-based editor and writer on the arts, culture and technology. He's written for The Ethics Centre, the Walkleys, Sydney Festival, Sydney Film Festival, Vice and many Australian arts organisations. He currently works for Sydney Festival.

Should we abolish the institution of marriage?

Should we abolish the institution of marriage?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Anna Goodman 12 OCT 2022

As it stands, in the western world, marriage is the legal union between two people who are typically romantic or sexual partners. Some philosophers are now revisiting the institution of marriage and asking what can be done to reform it, and if it should exist at all.

The institution of marriage has been around for over 4,000 years. Historians first see instances of marriages popping up around 2350 BCE in Mesopotamia, or modern day Iraq. Marriage turned a woman into a man’s object whose primary purpose was producing legitimate offspring.

Throughout the following centuries and millennia, the institution of marriage evolved. As the Roman Catholic church grew in power throughout the 6th, 7th, and 8th centuries, marriage became widely accepted as a sacrament, or a ceremony that imparted divine grace on two people. During the Middle Ages, as land ownership became an important part of wealth and status, marriage was about securing male heirs to pass down wealth and increasing family status by having a daughter marrying a land-owning man.

“The property-like status of women was evident in Western societies like Rome and Greece, where wives were taken solely for the purpose of bearing legitimate children and, in most cases, were treated like dependents and confined to activities such as caring for children, cooking, and keeping house.”

The thinking that a marriage should be about love really only began in the 1500s, during a period now known as the Renaissance. Not much improved with regard to equality for women, but the movement did put forth the idea that two parties should enter a marriage consensually. Instead of women being viewed as property to be bought and sold with a dowry, women had more autonomy which elevated their social status. Into the 1700s, while the working class were essentially free to marry who they wanted (as long as they married people in the same social class), girls born into aristocratic families were betrothed as infants and married as teenagers in financial alliances between families.

But marriage doesn’t look like this anymore, right? It’s easy to forget that interracial marriage was illegal in the United States until 1967 and until 1985 in South Africa. Marital rape only became a crime in all American states in 1993. Australia only legalised gay marriage at the end of 2017, making it one of 31 countries to do so. In the 4,000 years of marriage, most legalised marriage equality has happened in the last 50 years.

The nasty history of marriage has prompted some philosophers to ask: is it time to get rid of the institution of marriage? Or, is it possible to reform?

An argument for the abolition of marriage

“Freedom for women cannot be won without the abolition of marriage.”

In the last hundred years, there has been plenty of discourse about where marriage fits into modern life. One notable voice, Sheila Cronan, a feminist activist who participated actively in the second wave feminist movement in America, argued that marriage is comparable to slavery, as women performed free labour in the home and were reliant on their husbands for financial and social protection.

“Attack on such issues as employment discrimination are superfluous; as long as women are working for free in the home we cannot expect our demands for equal pay outside the home to be taken seriously.”

Cronan believed that it would be impossible to achieve true gender equality as long as marriage remained a dominant institution. The comparison of marriage to slavery was hugely controversial, though, because white women had significantly better living conditions and security than slaves. In a modern, western context, Cronan’s article may seem like a bit of an overstatement on the woes of marriage.

Is there an alternative to abolition?

Another contribution to the philosophy of marriage is the work of Elizabeth Brake. Instead of abolishing marriage, she puts forward a theory in her 2010 paper What Political Liberalism Implies for Marriage Law called “minimal marriage,” which claims that any people should be allowed to get married and enjoy all the legal rights that come with it, regardless of the kind of relationship they are in or the number of people in it.

Brake argues that when the state allows some kinds of marriages but not other kinds, the state is asserting one kind of relationship as more morally acceptable than another. Marriage in the western world provides a number of legal benefits: visitation rights in hospitals if someone gets sick, fewer complications around joint bank accounts, and the right to inherit the estate if a partner dies, to name a few. It is also often viewed as a better or superior kind of relationship, so those who are not allowed to get married are seen as being in an inferior kind of relationship.

Take for example the case of two elderly women who are close friends and have lived together for the last 30 years. If one of the elderly women falls ill and needs to go to hospital, her friend might not be able to visit her because she is not a spouse or next-of-kin. If she passes away and her friend is not in her will, then the friend will have no say over what happens to her estate. The reason these friends were not married was because they felt no romantic attraction to each other. But Brake asks us: why should their relationship be seen as less valuable or less important than a romantic one? Why should their caring relationship not be afforded the legal rights of marriage?

Many legal rights are tied to marriage. In the US, there are over 1000 federal “statutory provisions,” or clauses written in the law, in which marital status is a factor in determining who gets a benefit, privilege, or right. Brake argues that reforming marriage to be “minimal” is the best way to ensure that as many people as possible have these legal rights.

So, what should the future of marriage be?

Many people today will say that the day they got married was one of the best days of their lives. However, just because we have a more positive view of it now does not erase the thousands of years of discriminatory history. In addition, practices such as child marriage and arranged marriages that no longer occur in the western world are still the norm in other parts of the world.

While Cronan presents a strong argument for abolishing marriage and Brake presents a strong argument for its reform , we need to examine the underlying social ills that make marriage so complicated. Additionally, there’s no guarantee that abolishing or reforming marriage will eliminate the sexism, racism, and homophobia that create the conditions for marriage to be so discriminatory in the first place. Marriage may not be creating inequality as much as it is a symptom of inequality. While the question of what to do with marriage is worth interrogating, it’s important to consider the larger role it might play in creating social change and working towards equality.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

I'd like to talk to you: 'The Rehearsal' and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 6 OCT 2022

Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal, perhaps one of the slipperiest works of modern television, aims to solve a very complex, deeply recurrent problem: how do we navigate our interpersonal relations, which are ever-changing, and filled with opportunities to let people down and harm those we love?

In the show, which constantly blends the real with the fake, the documentary with the theatrical, the off-kilter comedian Nathan Fielder’s solution is supposedly simple: he finds people who are preparing to have difficult conversations with friends and loved ones, and gives them the opportunity to rehearse these encounters ahead of time.

The idea behind this ridiculous, though oddly logical practice is thus: if these people have already rehearsed an uncomfortable exchange with a loved one, then they can predict for every variable. They can polish their approach. When conversations branch off into different directions, they will have accounted for that branching already, leaving them to always choose the best, most impactful response.

To aid his mentees in this practice, Fielder uses an ever-escalating series of interventions. He creates dialogue flow trees, in which conversations can be unveiled in their full myriad of possibilities. He stages strange obstructions, ranging from fake babies to simulated drug overdoses. He takes the joyous chaos of being what Jean-Paul Sartre called “a thing in a world” – an agent who is perceived by other agents, and whose actions affect them – and he tries to simplify it.

Saying The Rehearsal is definitively “about” anything is a mistake – it’s too ever-changing, too messy, for that. But certainly, in its focus on trying to do the right thing by simplifying a complex world so that it might be predicted, the show can serve as a model of the pitfalls of trying to rationalise and generalise. It is a warning to those philosophers from the analytic tradition who reduce a world that is precisely so joyous and beautiful because it is so chaotic. So complex. And so filled with the potential for harm.

Fielder’s methods for helping people confront their own mistruths, find love, or fit better into their communities, are guided by the principle of a kind of lopsided rationality. The methods are laughable, of course – Fielder is a comedian. But they follow a strict, internally coherent form of thought.

In essence, what Fielder tries to do is generalise. He takes the nuances of life’s difficult conversations, and he strips them down to their component parts – maps them out on a board, uses actors to play them out ahead of time.

For instance, in the show’s first episode, Fielder recruits Kor, a competitive and trivia-obsessed young man who is preparing to tell his close friends that he has lied for years about getting a master’s degree. Fielder hires an actress to play Kor’s most abrasive friend, gets that actress to uncover as much information as possible about the real person she is stepping into the shoes of, and then puts Kor and this performer in a set that precisely replicates the dimensions of the bar where the actual conversation will go down.

The method – reduce. Simplify. Abstract. And use that generalised version of a real-life situation to guide how the actual situation will play out. This kind of ethical reasoning is highly tempting to us. We often find ourselves drawn to it, as we move through our lives.

Sure, we might not go to the lengths that Fielder does in The Rehearsal. But we do practice tough conversations in the shower with ourselves, ahead of time. We draft and re-draft text messages, and base them on how we might imagine the person we send them to will respond. In essence, we use our “rationality” and “reason” to help us move through the world, drawing on past experiences to help us navigate future ones.

Trivia-obsessed Kor, in fact, is a specific example of this. He is most worried about revealing his deception to his abrasive friend because of how she’s behaved in the past. He rationalises that because he has seen her blow up at others, getting angry at the drop of a hat, that she’ll do the same in the future, and more specifically, do it to him. He starts with a real-world experience – incidents of her temper – and then generalises them to a rule – she will always get angry – using his rationality to try and deduce the future, and thus the best action.

But what this kind of rationality does not take into account is the way that human beings shift and change; the way that they surprise us. How often have we prepared for an outcome that hasn’t come to light? Stressed about confrontations that turn out not to be confrontations at all?

Rather than generalising away from the inherent changeability of those we love, or indeed any of those who we surround ourselves with, we should instead embrace what the philosopher Jurgen Habermas described as “communicative rationality.”

For Habermas, our rational faculties shouldn’t generalise us away from the world – they shouldn’t isolate us. Instead, they should be part of a process of “achieving consensus”, as Habermas put it. We make decisions with other people. While staying in contact with them.

This means, rather than being a witness to the world – viewing it and then reviewing it, and using what we see and learn to guide our ethics – we are an active participant in it. On this model, our thoughts, desires, and ethical behaviours are essentially collaborative. They are grounded in the real world, and the people around us.

Thus, on Habermas’ view, we never stop discussing, talking, engaging. We don’t do as Kor does – using his rationality to effectively step himself away from his abrasive friend, halting in the process of communicating with her. And we don’t do as Fielder does – creating an artificial replica of the world, rather than just living in the actual world.

When we take the Fielder method, instead of adopting Habermas’ position of making everything communicative, we lose that which makes the world what it is: its messiness, its changeability, its dynamic and fluid nature.

There is nothing logically wrong, broadly speaking, about the kind of rationality that involves a step away from the world – that leads us to run through possible outcomes in our head with ourselves. Difficult conversations do move through different points; do branch off. So it makes some kind of sense to imagine that we should be able to predict them. The error here is not one in internal consistency. The error is taking a step backwards from those around us when trying to work out what to do, rather than taking a step forward.

The joke of The Rehearsal is precisely that this internally consistent form of rationality is remarkably, laughably devoid of life. It’s cold. Alien. It aims to solve real world problems, but it does that by turning to a printed board of branching lines of dialogue, instead of other human beings.

And it’s not even useful. As it turns out, Kor, who is highly nervous about the encounter with his abrasive friend, has little to worry about. When he confronts her, rather than the actress he has been rehearsing with, she is largely unfussed. She doesn’t mind that Kor has misrepresented himself. She expresses understanding for his duplicity. It is all pretty chill. Laughably so, in fact.

What Kor shows us is the importance of remaining in the world. That means we might fail them – that we might do the wrong thing. But that’s better than hiding away in a world of Fielder’s whiteboards. Indeed, our failures tell us that we’re human, bungling from one awful mistake to another, trying, and then failing, and then, beautifully, trying again. Guided always by people. Living always in communities. Staying blissfully, painfully connected.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

How to improve your organisation’s ethical decision-making

How to improve your organisation’s ethical decision-making

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 4 OCT 2022

Are you confident in your organisation’s ability to negotiate difficult ethical terrain? The Ethics Centre’s Decision Lab is a robust process that can help expand your ethical decision-making capability.

Imagine you run a not-for-profit that helps people experiencing problem gambling. You are approached by a high-net-worth individual connected to the gambling industry who is interested in making a substantial donation to your organisation. Funding is always hard to come by and you know you could reach many more people in need with this money. Do you accept the donation?

Or imagine you are the CEO of a publicly listed consulting firm that is deciding whether to take on a new client in the fossil fuel industry. You suspect it would be unpopular with younger members of your staff and some of your other clients, but it’s a very lucrative contract and it would significantly boost your bottom line ahead of reporting season. Do you take on the client?

What if you sat on the board of a major corporation that is planning to make a public statement urging the government to adopt a new progressive social policy. The proposed policy does not impact your business directly, but a majority of your staff support it. However, you personally have misgivings about the policy and suspect some other employees do as well. Do you put your name on the public statement?

What would you do in each of these situations? If you do have an answer, could you explain how you arrived at your decision? Could you defend it in public? Could you defend it on the front page of the newspaper?

Dealing with ethically-charged situations like these is never easy. Not only do our decisions have a material impact on multiple stakeholders, but we also need to be able to communicate and justify them. This is complicated by the fact that many of the influences on our ethical decision-making are implicit, meaning we risk making decisions based on unexamined values or we might struggle to explain how we arrived at a particular conclusion.

This is why The Ethics Centre has developed Decision Lab, a comprehensive ethical decision-making toolkit that surfaces the implicit elements in ethical decision-making and provides a robust process to navigate the ethical dimensions of critical decisions for organisations big and small.

Decision Lab

The Decision Lab process begins by clarifying the organisation’s core purpose, values and principles. The purpose includes the organisation’s overall mission, which is what it is aiming to achieve, and its vision, which is what the world looks like when it has achieved it. The values are what the organisation believes to be good and the principles are the guiderails that guide decision-making.

Even organisations that have published mission statements and codes of conduct will find that employees will have different understandings of purpose, values and principles, and these differences can influence ethical decision-making in a profound way. By bringing these perspectives to the surface, the Decision Lab process enables the diversity to be recognised and engaged with constructively rather than leaving it implicit and having different individuals pulling in different directions.

The Decision Lab also explores the process of decision-making, testing critical assumptions and taking multiple perspectives into account to ensure no key elements are overlooked. Take the hypothetical above about the not-for-profit. It would be easy to focus on the issue of whether it is hypocritical to accept money from those associated with gambling in order to fight problem gambling. But it is also crucial to consider the impact on other stakeholders, such as the beneficiaries of the not-for-profit’s services, their families and communities, or consider whether the perception of hypocrisy might affect future fundraising.

Shadow values

The process also acknowledges common biases and influences that can derail decision-making. A common one is the organisation’s Shadow Values which are the hidden uncodified norms and expectations promoted often out of awareness that can influence how the entire organisation operates. For example, many organisations explicitly subscribe to values such as integrity, but the shadow values might promote loyalty, which could prevent an employee from calling out a senior manager who is misrepresenting the work being done for a client.

The Decision Lab then provides a checklist for decisions that can be used as a ‘no regrets test,’ ensuring that all relevant elements have been considered. For example, should the consulting firm reject the contract with the fossil fuel company, it could suffer a backlash from shareholders, who argue that the board has a responsibility to create value for shareholders within the law rather than pursue political agendas. The Decision Lab checklist would ensure that such eventualities are considered before the decision was made.

The decision-making process is then stress tested against a variety of hypothetical scenarios, such as those above, that are tailored to the organisation’s mission and circumstances. This allows participants to put ethical decision-making into practice, engage in constructive deliberation and learn how to evaluate options and develop implementation plans as a team.

On completion of the Decision Lab, The Ethics Centre provides a customised decision-making framework that is tailored to the organisation and its needs for future reference.

Open book

The Decision Lab is a powerful and practical tool for any organisation looking to improve its ethical decision-making. It also has other benefits, such as increases awareness of the lived organisational culture, including the beliefs, attitudes and practices shared amongst its people. It identifies how the current culture and systems are enabling or constraining the realisation of the organisation’s goals.

By unifying employees around a common purpose and encouraging values-aligned behaviour, it ensures that the entire organisation is working as a unit towards a shared vision. The deliberative process also helps to build a climate of trust within the organisation, which aids in avoiding and resolving conflicts, as well as promoting good decision-making.

Individuals and organisations are constantly making decisions that have wide-reaching impacts. The question is: are you doing it well? The Decision Lab can ensure that your organisation’s decision-making is done in an open, robust and constructive manner, producing more ethical decisions and contributing to a positive work culture.

The Ethics Centre is a thought leader in assessing organisational cultural health and building leadership capability to make good ethical decisions. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Or visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Give them a piggy bank: Why every child should learn to navigate money with ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Self-interest versus public good: The untold damage the PwC scandal has done to the professions

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

This tool will help you make good decisions

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big tech knows too much about us. Here’s why Australia is in the perfect position to change that

Big tech knows too much about us. Here’s why Australia is in the perfect position to change that

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Alliance Emma Elsworthy 30 SEP 2022

Consumer Rights Data will bring an era of “commercial morality”, experts say.

Who are you? The question springs to mind a list of identity pillars – gender, job title, city, political leaning or perhaps a zany descriptor like “caffeine enthusiast!”. But who does big tech think you are?

Most of the time, we live in digital ignorance of the depth of data being scraped from everything from our Google searches to our Apple Pay purchases. Occasionally, however, we become only too aware of our own surveillance – looking at cute dog videos, for instance, and suddenly seeing ads for designer dog leashes in our Facebook feed.

It gets darker. In the wake of the US rolling back abortion law Roe v Wade, American women were discouraged from tracking their periods using an app on their smartphones. Big tech, pundits warn, could know when you’re pregnant – or more chillingly, whether you remained so.

In July, a report from Australian-US cybersecurity firm Internet 2.0 found popular youth-focused social media app TikTok could see user contact lists, access calendars, scan hard drives (including external ones) and geolocate our phones – and therefore us – on an hourly basis.

It’s “overly intrusive” data harvesting, the report found, considering “the application can and will run successfully without any of this data being gathered”.

Android users are far more exposed than Apple users because iOS significantly limits what information an app can gather. Apple has what is known as a “justification system”, meaning if an app developer wants access to something, it has to justify the requirement before Apple will permit it.

Should we be worried about TikTok’s access to our inner lives? With simmering geotensions between Australia and China – perhaps. The app is owned by ByteDance, a Beijing-based internet company, and the report found that “Chinese authorities can actually access device data”.

Professor of Business Information Systems at the University of Sydney Uri Gal writes that “TikTok’s data can also be used to compile detailed user profiles of Australians at scale”.

“Given its large and young Australian user base, it is quite likely that our country’s future prime minister and cabinet members are being surveilled and profiled by China,” he warned.

Australia is in a strong position to take action on the better protection of consumer data. Our world-leading Consumer Data Right (CDR) is being rolled out across Australia’s banking, energy and telecommunication sectors, placing the right to know about us back into our own hands.

Could our consumer rights expand beyond privacy rights to include specific economic rights too? Almost certainly, under CDR.

For instance, energy consumers would no longer have to wade through confusing fine print to work out whether they’re getting the best (and cheapest) electricity deal – with a click of a button they’d have their energy usage data sent to a new potential supplier, and the supplier would come back with a comparison.

That means no endless forms of information required upfront by a new provider, no lengthy phone calls spent cancelling one’s current provider, and crucially, no last-minute left-field discounts from a provider to keep you as a customer.

“Within five years, it should have transformed commerce, promoted competition in many sectors, and simplified daily life,” according to The University of NSW’s Ross P Buckley and Natalia Jevglevskaja.

“Thirty years ago, most Australian businesses thought charging current customers more than new customers was unfair and the law reflected this – such differential pricing was illegal,” the pair continued.

“Today those standards of behaviour seem to have fallen away and this is reflected in more relaxed consumer laws. In many contexts, CDR should reinstitute a commercial morality, a basic fairness, that modern business practices have set aside.”

A rethink of what it means to operate with transparency is what motivates fintech Flare, which aims at transforming the way Australians earn and engage in the workplace with superannuation, banking, and HR services.

Flare’s Head of Strategy Harry Godber was actually one of the original architects of CDR’s launch, which took place during his time in government as a former senior government advisor to Liberal prime ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison.

“[CDR] is designed to get rid of those barriers, get rid of the information asymmetry and allow you to have as much information about your banking products as someone else in the market as your bank has about you,” Godber said.

It’s a great equaliser, he continues, in that data will no longer separate the “haves and the have-nots” in the consumer world – essentially, financial literacy won’t ensure a consumer gets a better deal on products.

“That is a huge step forward when it comes to distributing financial products in an ethical way,” he continued.

“Because essentially it means if all data is equal, if everybody has access to every financial institution’s open product data and knows exactly how they will be treated then acquiring a customer suddenly becomes a matter of having good products, and very little else.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is debt learnt behaviour?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

LISTEN

Business + Leadership

Leading With Purpose

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY Emma Elsworthy

Before joining Crikey in 2021 as a journalist and newsletter editor, Emma was a breaking news reporter in the ABC’s Sydney newsroom, a journalist for BBC Australia, and a journalist within Fairfax Media’s regional network. She was part of a team awarded a Walkley for coverage of the 2019-2020 bushfire crisis, and won the Australian Press Council prize in 2013.

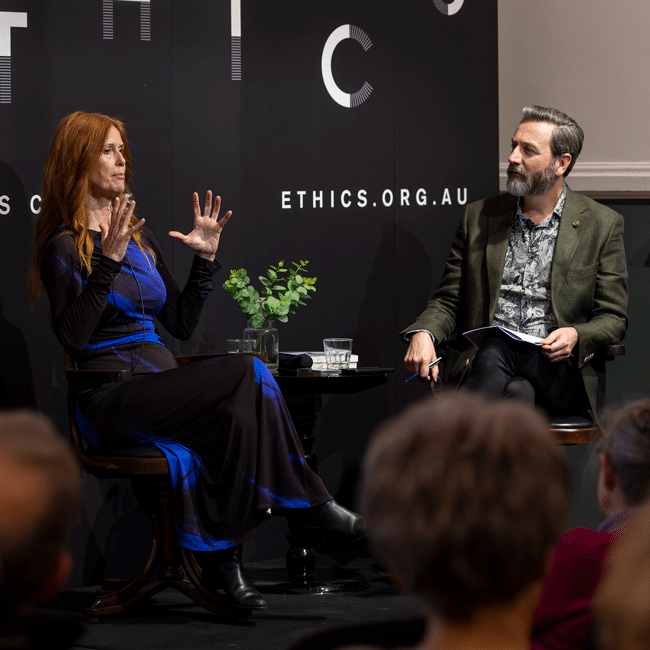

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 20 SEP 2022

Crime, culture, contempt and change – this year our Festival of Dangerous Ideas speakers covered some of the dangerous issues, dilemmas and ideas of our time.

Here are 5 things we learnt from FODI22:

1. Humans are key to combating misinformation

Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen says the world’s biggest social media platform’s slide into a cesspit of fake news, clickbait and shouty trolling was no accident – “Facebook gives the most reach to the most extreme ideas – and we got here through a series of individual decisions made for business reasons.”

While there are design tools that will drive down the spread of misinformation and we can mobilise as customers to put pressure on the companies to implement them, Haugen says the best thing we can do is have humans involved in the decision-making process about where to focus our attention, as AI and computers will automatically opt for the most extreme content that gets the most clicks and eyeballs.

2. We must allow ourselves to be vulnerable

In an impassioned love letter “to the man who bashed me”, poet and gender non-conforming artist, Alok teaches us the power of vulnerability, empathy and telling our own stories. “What’s missing in this world is a grief ritual – we carry so much pain inside of us, and we have nowhere to put the pain so we put it in each other.”

The more specific our words are the more universally we resonate, Alok says, “what we’re looking for as a people is permission – permission not just to tell our stories, but also to exist.”

3. We have to know ourselves better than machines do

Tech columnist and podcaster, Kevin Roose says “we are all different now as a result of our encounters with the internet.” From ‘recommended for you’ pages to personalisation algorithms, every time we pick up our phones, listen to music, watch Netflix, these persuasive features are sitting on the other side of our screens, attempting to change who we are and what we do. Roose says we must push back on handing all control to AI, even if it’s time consuming or makes us feel uncomfortable.

“We need a deeper understanding of the forces that try to manipulate us online – how they work, and how to engage wisely with them is the key not only to maintaining our independence and our sense of selves, but also to our survival as a species.”

4. We can use shame to change behaviour

Described by writer Jess Hill as “the worst feeling a human can possibly have”, the World Without Rape the panel discuss the universal theme of shame when it comes to sexual violence and its use as a method of control.

Instead of it being a weight for victims to bear, historian Joanna Bourke talks about shame as a tool to change perpetrator behaviour. “Rapists have extremely high levels of alcohol abuse and drug addictions because they actually do feel shame… if we have feminists affirming that you ought to feel shame then we can use that to change behaviour.”

5. Reason, science and humanism are the key to human progress

Steven Pinker believes in progress, arguing that the Enlightenment values of reason, science and humanism have transformed the world for the better, liberating billions of people from poverty, toil and conflict and producing a world of unprecedented prosperity, health and safety.

But that doesn’t mean that progress is inevitable. We still face major problems like climate change and nuclear war, as well as the lure of competing belief systems that reject reason, science and humanism. If we remain committed to Enlightenment values, we can solve these problems too. “Progress can continue if we remain committed to reason, science and humanism. But if we don’t, it may not.”

Catch up on select FODI22 sessions, streaming on demand for a limited time only.

Photography by Ken Leanfore

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Online grief and the digital dead

Big thinker

Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Matthew Liao

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Anna Goodman 13 SEP 2022

There will always be people in the world who have different opinions, values, and beliefs from our own. But this shouldn’t stop us from listening to those we know we disagree with, even if we think it’s unlikely that we will change our minds.

During part of the Covid-19 pandemic, I lived with my grandfather in rural Vermont, a small state in the north-east of the US. Being Australian, I had many opportunities to talk to people I would not have otherwise have had a chance to meet. Then, the 2020 presidential election between Joe Biden and Donald Trump rolled around, and it was all anyone could talk about.

My grandfather’s carer voted for Trump in 2020. I got to know her quite well – she’s a life-long rural north-easterner with a strong belief in individual self-sufficiency. We talked a lot about the differences between where we came from. Politics always comes up in conversation around an election, so naturally it came up that we would support different presidential candidates.

Most of the media that I consume and the majority of my social circle reinforce my liberal political views. Talking with my grandfather’s carer gave me a different perspective on why someone would vote for Trump. While her reasoning didn’t convince me to change my vote, I came to understand how my life led me to my beliefs on who should be president, and her life led to hers.

These conversations inspired me to think a little more about what we gain when we take the time to listen thoughtfully to people with different views, perspectives and opinions from ours. Here are three reasons (and a few tools) that can help us to gain the full benefit of listening to someone who has different beliefs from ours.

Be curious about reasons: both your own and others

Our values represent what we believe is good and bad in the world. But it’s uncommon for people to ‘choose’ their values. Instead, we are far more likely to adopt the values that our parents have and the dominant values of the communities we grow up in.

Nevertheless, we hold our values near and dear to our hearts. They form the foundations of our lives and who we are as people. Someone who has different values from us can feel as though they are a world away from us. In reality, it’s likely they just had a different upbringing, with access to different information and abided by different norms.

One tool we can use for finding the reasons behind certain views is to think like a philosopher and ask “why.” The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates is well known for doing this, with what we now call the Socratic method. Essentially, every time a claim is made, we can ask “why” until we get to some root cause or foundational reason.

The Socratic method can be used to interrogate the reasons behind both our own beliefs and the beliefs of others. Another tool was developed by Sakichi Toyoda, the founder of Toyota, who would ask “why” five times in order to get to the root cause of a problem. The same can be done when trying to get to the root of someone else’s beliefs. Asking “why” of our own beliefs and those of people around us (and people who aren’t around us) is an important part of recognising the differences in our experiences, and ultimately helps to paint a clearer picture of how our values and beliefs develop.

Be open to a broader understanding of the world

There is no doubt that we live in an increasingly polarised and divided world. Thanks to the internet, diverse and extreme views can now be easily shared, amplifying voices around the world. Often times, this creates echo chambers that shield us (and can even villainise) dissenting voices.

On top of this, we are creatures of habit. Our social media algorithms show us things we like, we read the same news sources each morning, and we catch up with our friends, who likely have similar values to us. The ‘other perspective’ is often pushed outside of our world view and can feel distant. It’s hard to understand why someone could have such different beliefs to us.

When I took the time to listen with the intention of understanding, I found that I had significantly more impactful and meaningful conversations. Most of my (limited) knowledge of American politics and sociology comes from a classroom, so it’s theory-based knowledge rather than knowledge grounded in experience. It’s one thing to read statistics and understand a theory in a classroom; it’s an entirely different thing to hear a personal story.

Listening to my grandfather’s carer talk about her experiences added a level of humanity into what I had learnt in a lecture hall. As a result, I have more empathy and understanding for people who have different life stories, and therefore different perspectives from mine. Being empathetic doesn’t mean necessarily changing our views, but rather humanising and understanding the multiple ways people form their understanding of the world.

Knowing when not to listen

I don’t want to take away from how difficult it is to really listen to someone who has fundamentally different beliefs from us. It can be emotionally draining and it requires the right headspace. It can also be harmful for individuals of marginalised identities to listen to views that discriminate against them, and be told to give those views equal consideration to non-discriminatory views.

The Socratic method can also be useful for determining when not to listen. If a belief is founded on a discriminatory, hateful, or untrue statement, it can help to provide grounds for not listening to a person’s point of view. Philosophers sometimes think about this through the framework of intellectual virtues, or qualities in a person that promote the pursuit of truth and intellectual flourishing. These virtues (such as empathy, integrity, intellectual responsibility and love of truth) can help us to discern good from bad foundational reasons that we might find by asking why.

At the end of the day, if we’re in the right headspace and feeling ready to learn, it’s a worthwhile practice for us to learn to listen and understand the reasons why people hold different views. In turn, we can reflect on our own views, and increase our empathy for those with different world views.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The problem with Australian identity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships