Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 12 SEP 2022

Critical Race Theory (CRT) seeks to explain the multitude of ways that race and racism have become embedded in modern societies. The core idea is that we need to look beyond individual acts of racism and make structural changes to prevent and remedy racial discrimination.

History

Despite debates about Critical Race Theory hitting the headlines relatively recently, the theory has been around for over 30 years. It was originally developed in the 1980s by Derrick Bell, a prominent civil rights activist and legal scholar. Bell argued that racial discrimination didn’t just occur because of individual prejudices but also because of systemic forces, including discriminatory laws, regulations and institutional biases in education, welfare and healthcare.

During the 1950s and 1960s in America, there were many legal changes that moved the country towards racial equality. Some of the most significant legal changes include the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which explicitly banned racial apartheid in American schools, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

These rulings and laws formally criminalised segregation, legalised interracial marriage and reduced restrictions in access to the ballot box that had been commonplace in many parts of America since the 1870s. There was also a concerted effort across education and the media to combat racially discriminatory beliefs and attitudes.

However, legal scholars noticed that even in spite of these prominent efforts, racism persisted throughout the country. How could racial equality be legislated by the highest court in America, and yet racial discrimination still occur every day?

Overview

Critical race theory, often shortened to CRT, is an academic framework that was developed out of legal scholarship that wanted to explain how institutions like the law perpetuates racial discrimination. The theory evolved to have an additional focus on how to change structures and institutions to produce a more equitable world. Today, CRT is mostly confined to academia, and while some elements of CRT may inform parts of primary and secondary education, very few schools teach CRT in its full form.

Some of the foundational principles of CRT are:

- CRT asserts that race is socially constructed. This means that the social and behavioural differences we see between different racialised groups are products of the society that they live in, not something biological or “natural.”

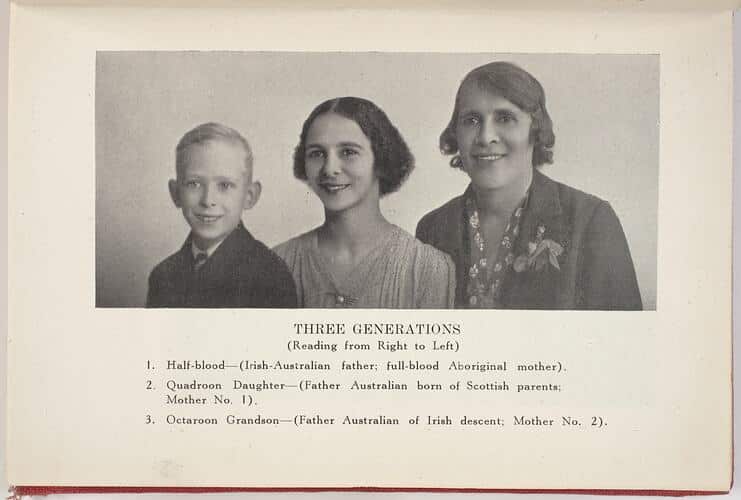

There is a long history of people using science to attempt to prove that there were significant social and psychological differences among people of different racial groups. They claimed these differences justified the poor treatment of people of different ‘inferior races’, or the ‘breeding out’ of certain races. This is how white Australians justified the atrocities committed in the Stolen Generations, such as the attempted ‘breeding out’ of Aboriginal people.

2. Racism is systemic and institutional. Imagine if everyone in the world magically erased all their racial biases. Racism would still exist, because there are systems and institutions that uphold racial discrimination, even if the people within them aren’t necessarily racist.

There are many examples of systemic and institutional racism around the world. They become evident when a system doesn’t have anything explicitly racist or discriminatory about it, but there are still differences in who benefits from that system. One example is the education system: it’s not explicitly racist, but students of different racial backgrounds have different educational outcomes and levels of attainment. In the US, this occurs because public schools are funded by both local and state governments, which means that children going to school in lower socioeconomic areas will be attending schools that receive less funding. Statistically, people of colour are more likely to live in lower socioeconomic areas of America. So, even though the education system isn’t explicitly racist (i.e., treating students of one racial background differently from students of a different racial background), their racial background still impacts their educational outcomes.

3. There is often more than one part of identity that can impact a person’s interaction with systems and institutions in society. Race is just one of many parts of identity that influences how a person will interact with the world. Different identities, including race, gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, religion and ability, intersect with each other and compound. This is an idea known as “intersectionality.”

Most of the time, it’s not just one part of a person’s identity that is impacting their experiences in the world. Someone who is a Black woman will experience racism differently from a Black man, because gender will impact experience, just like race. A wealthy Chinese-Australian person will have a different experience living in Australia than a working class Chinese-Australian person. Ultimately, CRT tells us that we need to look at race in conjunction with other facets of identity that impact a person’s experience.

Critical Race Theory and racism in Australia

As Australians, it’s easy to point the finger at the US and think “well, at least we aren’t as bad as them.” However, this mentality of only focusing on the worst instances of racism means we often ignore the happenings closer to home. A 2021 survey conducted by the ABC found that 76% of Australians from a non-European background reported experiencing racial discrimination. One-third of all Australians have experienced racism in the workplace and two-thirds of students from non-Anglo backgrounds have experienced racism in school.

In addition to frequent instances of racism, Australia’s history is fraught with racism that is predominantly left out of high school history textbooks. From our early colonial history to racial discrimination during the gold rush in the 1850s to anti-immigration rhetoric today, we don’t need to look far for examples of racial discrimination. A little known part of Australian history is that non-British immigrants from 1901 until the 1960s were told that if they moved to Australia, they had to shed their languages and culture.

Even though CRT originates in the US, it is a useful framework for encouraging a closer analysis of Australia’s racist history and how this has caused the imbalances and inequalities we see today. And once we understand the systemic and institutional forces that promote or sustain racial injustice, we can take measures to correct them to produce more equitable outcomes for all.

If you want to learn more about how race has impacted the world today, here are some good places to start:

- Nell Painter’s Soul Murder and Slavery – her work has focused on the generational psychological impact of the trauma of slavery. Here is an interview where Painter talks a little bit about her work.

- Nikole Hannah-Jones’ 1619 Project, with the New York Times – you can listen to the podcast on Spotify, which has six great episodes on some of the less reported ways that slavery has impacted the functioning of US society.

- Dear White People – a Netflix show that deals with some of the complications of race on a US college campus.

- Ladies in Black – a movie about Sydney c. 1950s, shows many instances of the casual racism towards refugees and immigrants from Europe.

For a deeper dive on Critical Race Theory, Claire G. Coleman presents Words Are Weapons and Sisonke Msimang and Stan Grant present Precious White Lives as Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Respect

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Why sometimes the right thing to do is nothing at all

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Steven Pinker

Steven Pinker (1954-present) is an experimental psychologist who is “interested in all aspects of language, mind, and human nature.” In 2021, Academic Influence calculated that he was the second-most influential psychologist in the world in the decade 2010-2020.

Steven Pinker is a Canadian-American cognitive psychologist, psycholinguist, popular science author and public intellectual. He grew up in Montreal, earning his Bachelor’s degree in experimental psychology from McGill University and his PhD from Harvard University. He is currently the Johnstone Family Professor in the Department of Psychology at Harvard.

At the start of his graduate studies, Pinker found himself interested in language, and in particular, language development in children. In 1994, he went on to publish the first of his nine books written for a general audience, entitled The Language Instinct. In the book, Pinker introduces the reader to some of the fundamental parts of language, and argues that language itself is an instinct that makes humans unique.

Language, society and the mind

Try and have a thought without any language. It might be an idea or a memory that appears in your mind with no words or internal monologue. It’s quite difficult to switch off the voice in our heads for more than a few seconds. Pinker researches this connection between language and how our minds work.

To date, Pinker is the author of nine books written for a general audience. He covers a wide range of topics and questions that get at the heart of how we learn languages and what this does to our minds. His book The Stuff of Thought (2007) looks at how language shapes the way we think. He begins by suggesting that when we use language, we are doing two things:

- Conveying a message to someone

- Negotiating the social relationship between ourselves and whoever we are speaking to

For example, when a professor stands at the front of a lecture hall and tells her students “may I have your attention, class is about to begin” the professor is doing two things. First, she is alerting her students that class is starting (the message), and second, she is operating within the professor-student hierarchy (the social relationship) in which students should give their attention.

Taking this framework for language, Pinker works to untangle some of the complicated questions around language, such as “Why do so many swear words involve topics like sex, bodily functions or the divine?” and “Why do some children’s names thrive while others fall out of favour?”

Trends of today: is violence declining?

Pinker’s academic interests and research extends beyond language. In 2011, he published The Better Angels of Our Nature, which makes the claim that violence in human societies has generally decreased steadily over time.

“Historical data from past centuries are far less complete, but the existing estimates of death tolls, when calculated as a proportion of the world’s population at the time, show at least nine atrocities before the 20th century (that we know of) which may have been worse than World War II.”

Violence in this case does not just mean war. Pinker also looks at collapsing empires, the slave trade, the murder of native peoples, treatment of children and religious persecution as acts of violence in the world. While it feels like we see and hear about a lot of violence today, he notes that it’s often because these are ‘newsworthy’ events.

“In the case of violence, you never see a reporter with a microphone and a sound truck in front of a high school announcing that the school has not been shot up today, or in an African capital noting that a civil war has not erupted.”

After establishing the trend of declining violence, he looks at historical factors that work to explain why we live in a less violent world. Some of these trends include increasing respect for women, the rise in technological progress, and more application of knowledge and rationality to human affairs.

Current work

Steven Pinker’s work has received a number of prizes for his books, including the William James Book Prize three times, the Los Angeles Times Science Book Prize, the Eleanor Maccoby Book Prize, the Cundill Recognition of Excellence in History Award, and the Plain English International Award. He has also served as an editor and advisor for a variety of scientific, scholarly, media and humanist organisations.

Steven Pinker still spends his time researching a diverse array of topics in psychology, language, historical and recent trends in violence, and neurobiology. One specific area he is currently researching is the role of common knowledge (i.e., things that we know other people know without having to say what we know) in language and other social phenomena.

Steven Pinker presents Enlightenment or Dark Age? as part of Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Now is the time to talk about the Voice

WATCH

Relationships

Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The new normal: The ethical equivalence of cisgender and transgender identities

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 1 SEP 2022

News is designed to grab your attention but not all of it is relevant to your life. The good news is you needn’t feel guilty for tuning out of news that makes you sad or angry and is out of your power to influence.

Two stories appear on your favourite news website. The first is about an adorable half-tonne walrus named Freya being euthanised in Norway because gormless onlookers refused to heed government advice to keep their distance.

The second covers China’s central bank cutting interest rates to stimulate growth while most other wealthy nations around the world are raising them to fight inflation.

Which of these stories grabs your attention the most? Which are you most likely to click on?

If you answered the first, then you’re not alone. In fact, the ‘popular right now’ lists on most news websites show that rogue wildlife invading metropolitan areas easily outrank stories speculating on China’s economic health.

But which most affects your life?

Even if you happened to be in Norway during the Freya saga, the news would be unlikely to impact your day-to-day goings on (unless it was a warning to steer clear of the beast). On the other hand, if China slips into recession, it could alter the global financial and geopolitical landscape, impacting everything from grocery prices to the prospect of war in Taiwan.

I’m not intending to shame you for clicking on the more sensationalist story. I did. We are only human, and Freya’s story pushes emotional buttons of care for native wildlife as well as outrage directed at the twits whose desire for a selfie caused the death of an innocent animal.

But what are we looking for when we switch on the radio or swipe that phone screen? What really is ‘news’? Through our cumulative clicks on news stories, what are we asking media outlets for? And is what we’re asking for doing us any good?

When we click on a story about horrific crime, a child abduction, a fatal shark attack or one of the countless stories about celebrity dalliances, what does it tell us about the world? Probably not much. In fact, these stories probably do more to distort our understanding of the world rather than clarifying it.

Horrific crimes do happen, but a lot less frequently than we might think. Child abductions by strangers are incredibly rare (that’s what makes them newsworthy when they happen). Shark attacks do happen, but you’re more likely to be injured driving to the beach than you are by in the toothy maw of a cartilaginous fish. And when it comes to celebrities, no-one is surprised that high status individuals living in a wealth and fame bubble behave just like us, only more so.

The deeper impact of news like this is that it normalises an abnormal image of the world, one coloured by our natural fascination with violence, tragedy, mortality, injustice, sexual indiscretion and scandal. Many of these things make the news because they’re exceptional in the modern world; it’s precisely because our society is more peaceful and stable than at just about any point in history that conflict and instability stand out.

But through constant exposure to the exceptional through news headlines, it eventually becomes normal. Studies have shown that Australians consistently overestimate the levels of violent crime in their neighbourhoods, due at least in part to the way crime, conflict and injustice are reported but lawfulness, peace and justice are not.

The torrent of sensational news also comes at an emotional cost, especially when we’re confronted with a daily litany of injustices from around the world. We are naturally inclined to experience outrage when we hear about how women are mistreated in Afghanistan, about civilians being killed in Ukraine or another mass shooting in school in the United States, and this outrage motivates us to take action to rectify it. But the simple fact is that we have limited power to act on most of the injustices that we encounter in the news. Mass media has expanded our sphere of perception to be global but our sphere of influence remains largely local.

This, in turn, can inspire feelings of disempowerment and hopelessness. And it can encourage us to seek to regain our sense of agency wherever we can. However, it’s far easier to regain a sense of agency, such as by complaining or calling people out on social media, than it is to have power over grand or distant events. Social media can make us feel like we’re doing something, like we’re fighting back against injustice, but much of that is illusory. Often all we’re doing is sharing the injustices around, getting other people outraged and further eroding their sense of agency.

Life is cacophonous. News is supposed to filter out the noise and reveal what is important, relevant and impactful so we can focus our attention on what really matters. But news has descended into its own form of cacophony. We often fall back on our gut to sense what is important, but our gut is far from impartial.

The point is not to stop engaging with the news. It’s not to blame ourselves or others for being human. It’s to remember that the news isn’t always healthy. It isn’t always relevant. It doesn’t always reveal the whole of the world as it really is.

The good news is we do retain some control, and we have some responsibility over what we choose to view, which outlets to follow, which stories to click on, which ones to share. It takes some discipline, but that’s what living ethically means: cultivating the discipline to do what’s right, not just what’s easy.

Sometimes it means choosing not to engage with certain news. We shouldn’t feel guilty about that. We can pick our battles and choose where to invest our emotional energy. If we choose wisely, we can engage with the portions of the world over which we have greater influence and actually change it for the better.

We might still click on that story about a rogue walrus being killed because of inconsiderate onlookers or be amused by the latest celebrity scandal, but we can also remain wise enough to know that these do not reflect the world as it is, only the world as it appears through the imperfect filter of the news.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Are there any powerful swear words left?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Read before you think: 10 dangerous books for FODI22

Read before you think: 10 dangerous books for FODI22

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 29 AUG 2022

Truth, trust, tech, tattoos and taboos – The Festival of Dangerous Ideas returns live to Sydney 17-18 September with big ideas, dicey topics and critical conversations.

From history and science, to art, politics, and economics, FODI holds issues up to the light – challenging, celebrating and debating some of the most complex questions of our times.

In partnership with Gleebooks, these 10 reads from this year’s line-up of thinkers, artists, experts and disruptors will sharpen your mind, put your mettle to the test and help you stay ahead of the discussion:

Beyond the Gender Binary by Alok Vaid-Menon

Talking from their own experiences as a gender non-conforming artist, Alok Vaid-Menon challenges the world to see gender in full colour.

Alok // Live at FODI22 // Beyond the Gender Binary // Sat 17 Sept // 7:15pm

Lies, Damned Lies by Claire G. Coleman

A deeply personal exploration of Australia’s past, present and future, and the stark reality of the ongoing trauma of Australia’s violent colonisation.

Claire G. Goleman // Live at FODI22 // Words are Weapons // Sun 18 Sept // 11am

See What You Made Me Do by Jess Hill

A confronting and deeply researched account uncovering the ways in which abusers exert control in the darkest, and most intimate, ways imaginable.

Jess Hill // Live at FODI22 // World Without Rape // Sun 18 Sept // 2pm

Enlightenment Now by Steven Pinker

Exploring the formidable challenges we face today – rather than sinking into despair we must treat them as problems we can solve.

Steven Pinker // Live at FODI22 // Enlightenment or a dark age? // Sun 18 Sept // 6pm

Futureproof: 9 rules for humans in the age of automation by Kevin Roose

A hopeful, pragmatic vision for how we can thrive in the age of AI and automation.

Kevin Roose // Live at FODI22 // Caught in a Web // Sat 17 Sept // 3pm

Rebel with a cause by Jacqui Lambie

The Senator’s memoir that is as fascinating, honest, surprising and headline-grabbing as the woman herself.

Jacqui Lambie // Live at FODI22 // On Blowing Things Up // Sat 17 Sept // 11am

The Uncaged Sky by Kylie Moore-Gilbert

The extraordinary true story of Moore-Gilbert’s fight to survive 804 days imprisoned in Iran, exploring resilience, solidarity and what it means to be free.

Kylie Moore-Gibert // Live at FODI22 // Expendable Australians // Sat 17 Sept // 4pm

Quarterly Essay 87: The Ethics and Politics of Public Debate by Waleed Aly & Scott Stephens

In this edition of Quarterly Essay, Aly and Stephens explore why public debate is increasingly polarised – and what we can do about it.

Waleed Aly & Scott Stephens present a special edition of The Minefield live at FODI22 // Contempt is Corroding Democracy // Sun 18 Sept // 3pm

Strongmen by Ruth Ben-Ghiat

A fierce and perceptive history, and a vital step in understanding how to combat the forces which seek to derail democracy and seize our rights.

Ruth Ben-Ghiat // Live at FODI22 // Return of the Strongman // Sat 17 Sept // 5pm

When America Stopped Being Greatby Nick Bryant

The history of Trump’s rise is also a history of America’s fall – not only are we witnessing America’s post-millennial decline, but also the country’s disintegration.

Nick Bryant // Live at FODI22 // American Decadence // Sun 18 Sept // 12pm

These titles, plus more will be available at the FODI Dangerous Books popup – running 10am-8pm across 17-18 September at Carriageworks, Sydney. Check out the full FODI program at festivalofdangerousideas.com

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Does ‘The Traitors’ prove we’re all secretly selfish, evil people?

READ

Society + Culture

10 dangerous reads for FODI24

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

We can help older Australians by asking them for help

We can help older Australians by asking them for help

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 26 AUG 2022

Older people are often undervalued and overlooked in our society – to their detriment, and ours.

A stranger knocked on our door the other day. She was promoting a service for older people who live alone. To counter the risk of an accident or sudden illness going unnoticed, a person could sign up to have a Red Cross volunteer call them every day.

It was heart-warming and heart-breaking; wonderful that an organisation was intervening to address the frightening risk of solitary suffering, terrible that the risk was so pervasive that it warranted an organisation intervening.

I was reminded of an initiative based in Africa that I’d heard about on Maya Shanka’s podcast A Slight Change of Plans, one that wasn’t designed to help older people, but to enlist their help.

The Friendship Bench was started in Zimbabwe by psychiatrist Dr Dixon Chibanda. Its goal was to alleviate pressure on the country’s health system by training ‘grandmothers’ (respected older women in the community) to meet people with common mild-to-moderate mental health disorders at a park bench, let them talk through their problems, and help them choose just one to try and solve.

Prospective volunteers, not to mention many of Chibanda’s peers, were sceptical at first, but he didn’t just train the grandmothers—he let them train him.

As a psychiatrist, Chibanda was schooled to avoid telling his own story or being vulnerable; his volunteers taught him the key to connecting with a person and building trust was a willingness to bend this rule.

They also told him that calling the park benches where the therapy took place ‘mental health benches’ as he’d planned would create such a stigma that no one would show up. Taking their advice, he renamed them ‘friendship benches’.

Randomised control trials have since shown therapy from trained community grandmothers to be remarkably effective. Better still, the volunteers benefit richly, gaining “a profound sense of purpose and a sense of belonging” from the work. “It’s a win/win,” Chibanda told Shanka. The “grandmothers” are helping people, “but it’s helping them too”.

Chibanda says one of the things he’s learned from the Friendship Bench is just how important connection is. The therapy doesn’t really start, he says, until the moment people connect.

The scheme has since been rolled out elsewhere; Chibanda says he’d like to see friendship benches all over the world. But I suspect the barriers in places like Australia would be even greater than those faced in Africa; not because of stigma surrounding mental health, but because of stigma surrounding “the elderly”.

Chibanda says his volunteers were considered custodians of local wisdom and culture. But in more individualistic, materialistic cultures, there’s a tendency to depict older people as burdensome instead.

From useless to used

Sarah Holland-Batt’s 2020 essay Magical Thinking and the Aged-care Crisis explores this tendency. She discusses inheritance impatience, elder abuse and mandated euthanasia in dystopian fiction, then declares: “the apocalypse has already arrived for Australia’s elderly”.

“We treat older people as a separate and subhuman class, frequently viewing them as a burden on their families, the community and the state,” she writes.

Immanuel Kant argued against treating people as mere resources, but according to Holland-Batt, our aged-care industry does precisely this; it mines people for profit. If Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre was right when he said the way we treat “the very young and the very old, the sick, the injured, and the otherwise disabled” is an important indicator of a community’s flourishing, ours is falling short.

I think of the way I’ve heard Indigenous people speak about their elders—with reverence and respect; of the biblical command to honour one’s parents; of the proverb that describes grey hair as a ‘crown of glory’.

When did assuming people have nothing more to offer once they’re ‘old’ become acceptable? When did we stop treasuring the kind of wisdom that builds with experience? And how dearly has it cost us?

A closer relationship, a broader perspective

What I loved most about the Friendship Bench was the image it evoked of people from different generations sitting side by side. I loved the underlying assumption that the elderly among us still have much to offer: an offering so unique they were the key to the initiative’s success. I also loved the idea the therapy took place not under fluorescent light, but shining sun.

The fact the volunteers benefited just as much as those they were there to help did not surprise me. Who doesn’t want to put the lessons learnt over the years to use? To see somebody suffering, and help? Not all, I grant, but many—maybe most.

If only Australia’s discussions about aged care were less reactive and more proactive. If only there were less talk of problems and more of potential.

Yes, as we grow old, we grow more dependent and less capable; we cannot deny the reality of declining physical and sometimes mental functioning. But our bodies will impose enough limits without generalised assumptions based on age imposing more. I know of people in their nineties who still work as volunteers. We’re all unique; our ageing and its timing will be too. And even when age does stop us from helping, makes us start depending more, it cannot take our value, our worthiness of care, respect, and love.

The biggest game-changer I can imagine when it comes to the way our society views and treats its older members, is a rise in intergenerational connection—better still, friendship.

In some respects, our society is more connected than ever before, but not in the ways that count the most. If we want to tackle loneliness, depression and despair, this must change. We not only have to change the way we act, we must change the way we think. ‘The elderly’ need us, and we need them.

Examine what it means to age and grow older, and how this impacts all our lives. Join us for The Ethics of Being Old on Thur 24 Oct 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Joshua Pearl 22 AUG 2022

Pick up a first-year undergraduate economics textbook on tax and you’ll likely be apprised that there are three desired features of a tax policy: simplicity, efficiency and fairness.

The importance of the first two are somewhat obvious. Simplicity, because taxpayers need to understand how to comply with the tax system. Efficiency, because if people can easily change their behaviour to avoid paying tax, there won’t be much revenue to fund government expenditure. But fairness, the third desired feature of tax policy, is more nebulous.

Tax fairness is important not merely because economists tell us so. Rather, Australia needs to consider tax fairness for reasons such as: ensuring the continued political legitimacy of the Australian governments; because tax inherently deals with issues of inequality; and for the very practical reason of helping us deliver tax system reform.

In a liberal country such as Australia, a well-accepted norm is that restrictions on individual freedom must be justified. And in liberal philosophy, the dominate way to justify government restrictions is by considering a “public reason” test, well-articulated by influential twentieth century philosopher John Rawls’ liberal principle of legitimacy:

“Political power is legitimate only when it is exercised in accordance with a constitution (written or unwritten) the essentials of which all citizens, as reasonable and rational, can endorse in the light of their common human reason”.

Restrictions that are arbitrary, unfair, exploitative or focus on benefitting a few at the expense of the many, undermine political legitimacy because they cannot be justified. Prohibiting the Nazi swastika might be justifiable because people have a right not to be vilified or feel physically threatened. But prohibiting tattoos or facial piercings, dress wear, beach outfits or more sinisterly, citizenship based on skin colour, because they offend certain sensibilities, are not legitimate forms of government coercion because they cannot be reasonably justified using the public reason test.

Rawls considered the public reason test would apply to areas in the public domain relating to judges, government officials, and politicians. And the public reason test applies to taxation as much as any other act of government coercion. Taxation, the compulsory, unrequited payment to government, is quite literally nothing, if it is not coercive. In Australia we pay around $600bn in tax each year, over $40,000 per working person.

If the tax system is unfair, it cannot be justified. And taxation that is unjustified etches away at the political legitimacy of the Australian government and, in turn, Australian democracy.

The two primary functions of tax are:

1. to fund public goods such as military, transport, education, police and the judiciary

2. to redistribute wealth and income, through policies such as pension payments, unemployment payments, childcare and paid parental leave. Therefore, because tax impacts wealth and income distribution, as well as economic inequality, the tax system has inherent fairness implications.

Wealth and income distribution, the second function of tax, determines economic inequality, an inherent fairness issue. And to determine the required tax level requires consideration of the level of wealth and income inequality we consider fair. It might be said this issue is more relevant today than in other times in our recent history; Australian inequality measures have increased steadily since the 1980s. But even if we consider current wealth and income inequality levels as acceptable, presumably there is a limit. It is unlikely that Australia would still be considered a fair country if we were a nation of 20 billionaires and twenty million paupers.

One might be tempted to try and decouple tax issues from fairness issues by claiming Australia and our tax system is fair so long as we have equality of opportunity; instead of worrying about wealth inequality and tax, we should focus on realising Australian cultural values such as a “fair go”, a value synonymous (according to the citizenship tests new citizens take) with “equality of opportunity”.

However, a “fair go” isn’t free. For a rich child and a poor child to have the same opportunities with respect to education, learning and a successful career, we require tax. For equality of opportunity to exist, the rich parent needs to contribute more tax to fund our education institutions than what the poor parent can afford. Here, issues of tax and fairness are bound.

A less philosophical reason as to why it’s important for Australia to consider tax system fairness relates to tax reform. The consensus among economists is the Australian tax system is uncompetitive, inefficient, too complex and out of date. And they may have a point.

Australia hasn’t had meaningful tax reform for decades and is out of step with international best practice. The Federal Government deficit is large and growing, thanks in part to the former government’s COVID-19 splurges (some necessary, some arguably less so). And Australian government debt is forecast to reach a trillion dollars in the coming years, a level that may limit or preclude policy responses to future wars, pandemics, financial crises or property market crashes (and the implications of muted policy options is not merely no pink batts or no JobKeeper in time of catastrophe, but no jobs, high unemployment and potential social unrest).

Yet despite the arguments of a host of economic experts, such as ANU’s Professor Robert Breunig the former Federal Treasury head Dr. Ken Henry, OECD and IMF mandarins, to name but a few, the Australian tax system remains as it is. While tax reform by its nature is challenging (there is always a loser – someone will be paying more), it’s hard not to think the focus on tax efficiency, tax competitiveness, tax complexity and so on and so forth, has failed to create the “burning platform” needed to drive policy change. A greater focus on the fairness of the Australian tax system may be what is required to buttress the valid but sometimes technical economic arguments for Australian tax system reform.

Considering fairness of the tax system is important for political legitimacy, inequality and practical reasons. A tax system that is fair strengthens our democracy by ensuring taxation remains justifiable. Tax fairness helps us realise Australian cultural values such as equality of opportunity. And a greater focus on tax fairness might help us undertake meaningful tax reform, delivering a tax system that is simple, efficient and fair.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Survivors are talking, but what’s changing?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

BY Joshua Pearl

Joshua Pearl is the head of Energy Transition at Iberdrola Australia. Josh has previously worked in government and political and corporate advisory. Josh studied economics and finance at the University of New South Wales and philosophy and economics at the London School of Economics.

Come join the Circle of Chairs

More than thirty years ago, philosopher and Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, Dr Simon Longstaff AO placed a dozen chairs in a circle in Martin Place in the centre of Sydney’s busy CBD. Next to them he put up a sign that said: “If you would like to discuss ideas with a philosopher join the circle”.

At first, the circle attracted little more than sidelong glances from curious passers-by. But it wasn’t long before people paused to read the sign, a few of them taking up the offer to occupy one of the chairs and start a conversation. Soon the circle was full and the discussion buzzing.

Simon discovered that many people had an unsated appetite for a different kind of conversation than the one that usually unfolded with friends, family and colleagues or, heaven forbid, online.

This was a kind of conversation where they could open up and express their deepest beliefs and attitudes, where they could ask questions without people presuming the worst about them, where they could have their ideas challenged without feeling judged or threatened, and where they could explore a topic before making up their mind.

Simon returned regularly to Martin Place with his circle of chairs, and each time more and more people stopped by to discuss ideas with him and the others seated around the circle. People started to come from far and wide to join in the conversation, having heard about it from friends or family. Rarely were chairs left empty.

With his Circle of Chairs, Simon had effectively created a space where people were safe to talk about difficult and challenging subjects. What made it work was that it wasn’t just free and unregulated discourse. Simon was able to bring his skills as a philosopher to facilitate the conversation and set appropriate norms that enabled people to speak and listen in good faith in ways that are difficult to achieve in everyday conversations.

This exercise all those years ago served as a crucial spark that led to the creation of The Ethics Centre, which still works to create safe spaces to discuss difficult and important subjects to this day.

Welcome to the conversation

Presented by The Ethics Centre, Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) is Australia’s original disruptive festival. By holding uncomfortable ideas up to the light and challenging thinking on some of the most persevering and difficult issues of our time, FODI aims to question our deepest held beliefs and desires.

Which is why Dr Simon Longstaff’s original vision of a Circle of Chairs is returning to this year’s FODI, in partnership with JobLink Plus. With six sessions held over the two days, we’re inviting festival goers to take up a chair and sit shoulder to shoulder with leading philosophers Dr Simon Longstaff, Dr Tim Dean and Dr Kelly Hamilton, who will be joined by special guest conversationalists to unpick some of modern life’s most dangerous ethical dilemmas.

Will you agree with your fellow FODI attendee’s views? Pull up a chair and join or simply watch the guided conversations unfold as together we examine how we’re really feeling, thinking and doing.

We hope to see more safe spaces opening up outside of FODI to help us all have the opportunity to share our authentic views and tackle the most challenging, and important, questions that we face today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Stopping domestic violence means rethinking masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Gender

Ethics Explainer: Gender

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 10 AUG 2022

Gender is a complex social concept that broadly refers to characteristics, like roles, behaviours and norms, associated with masculinity and femininity.

Historically, gender in Western cultures has been a simple thing to define because it was seen as an extension of biological sex: ‘women’ were human females and ‘men’ were human males, where female and male were understood as biological categories.

This was due to a view that espouses the idea that biology (i.e., sex) predetermines or limits a host of social, psychological and behavioural traits that are inherently different between men and women, a view often referred to as biological determinism. This is where we get stereotypes like “men are rational and unemotional” and “women are passive and caring”.

While most people reject biologically deterministic views today, most still don’t distinguish between sex and gender. However, the conversation is slowly beginning to shift as a result of decades of feminist literature.

Additionally, it’s worth noting that outside of Western traditions, gender has been a much more fluid and complex concept for thousands of years. Hundreds of traditional cultures around the world have conceptions of gender that extend beyond the binary of men and women.

Feminist Gender Theory

Feminism has had a long history of challenging assumptions about gender, especially since the late twentieth century. Alongside some psychologists at the time, feminists began differentiating between sex and gender to argue that many of the differences between men and women that people took to be intrinsic were really the result of social and cultural conditioning.

Prior to this, sex and gender were thought be essentially the same thing. This encouraged people to confer biological differences onto social and cultural expectations. Feminists argue that this is a self-fulfilling misconception that produces oppression in many different ways; for example, socially and culturally limiting attitudes that prevent women from engaging in “masculine” activities and vice versa.

Really, they say, gender is social and sex is biological. Philosopher Simone de Beauvoir famously said: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”.

Gender being social means that it’s a concept that is constructed and shaped by our perceptions of masculinity and femininity, and that it can vary between societies and cultures. Sex being biological means that it’s scientifically observable (though the idea of binary sex is also being questioned given there are over 100 million intersex people all over the world).

Philosophers like Simone de Beauvoir argued that gendered assumptions and expectations were so deeply engrained in our lives that they began to appear biologically predetermined, which gave credence to the idea of women being subservient because they were biologically so.

“Social discrimination produces in women moral and intellectual effects so profound that they appear to be caused by nature.”

Gender and Identity

Gender being socially constructed means that it is mutable. With this increasingly mainstream understanding, people with more diverse gender identities than simply that which they were assigned at birth (cisgender) have been able to identify themselves in ways that more closely reflect their experiences and expressions.

For example, some people identify with a different gender than what they were assigned at birth based on their sex (transgender); some people don’t identify as either man or woman, and instead feel that they are somewhere in between, or that the binary conception of gender doesn’t fit their experience and identity at all (non-binary). In many non-western cultures, gender has never been a binary concept.

Unfortunately, with the inherently identity-based nature of gender, a host of ethical issues arise mostly in the form of discrimination.

Transgender people, for example, are often the target of discrimination. This can be in areas as simple as what bathrooms they use to more complicated areas like participation in elite sports. Notably, these examples of discrimination are almost always targeted at transfeminine people (those who identify as women after being assigned men at birth).

Additionally, there are ethical considerations that have to be taken into account when young people, particularly minors, make decisions about affirming their gender. Currently, it’s standard medical practice for people under 18 to be barred from making decisions about permanent medical procedures, though this still allows them to (with professional, medical guidance) take puberty blockers that help to mitigate extra dysphoria linked to undergoing puberty in a gender the person doesn’t identify with.

Gender stereotypes in general also have negatives effects on all genders. Genderqueer people are often the targets of violence and discrimination. Women have historically been and are still oppressed in many ways because of systemic gender biases, like being discouraged to work in certain fields, being paid less for similar work or being harassed in various areas of their lives. Men also face harmful effects of rigid gender norms that often result in risk-taking behaviour, internalisation of mental health struggles, and encouraging violent or anti-social behaviour.

The Future of Gender

This has been an overview of the most common views on gender. However, there are also many variations on the traditional feminist view that other feminists argue are more accurate depictions of reality.

bell hooks was known to criticise some variations of gender that revolved around sexuality because they did not properly account for the way that class, race and socio-economic status changed the way that a woman was viewed and expected to behave. For example, many views of gender are from the perspective of white, western women and so fail to represent women in more marginalised circumstances.

Along similar lines, Judith Butler criticises the very idea of grouping people into genders, arguing that it is and will always be inherently normative and hence exclusionary. For Butler, gender is not simply about identity, it’s primarily about equality and justice.

Even some earlier gender theorists like Gayle Rubin argue for the eventual abolishment of gender from society, in which people are free to express themselves in whatever individual way they desire, free from any norms or expectations based on their biology and subsequent socialisation.

“The dream I find most compelling is one of an androgynous and genderless (though not sexless) society, in which one’s sexual anatomy is irrelevant to who one is, what one does, and with whom one makes love.”

Gender is currently a very active research and debate area, not only in philosophy, but also in sociology, politics and LGBTQI+ education. While theories about identity often result in conflict due to its inherently personal nature, it’s promising to see such a clear area where work by philosophers has significantly influenced public discourse with profound effects on many people’s lives.

For a deeper dive on gender, Alok Vaid-Menon presents Beyond the Gender Binary as part of Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why certain things shouldn’t be “owned”

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Joanna Bourke

Joanna Bourke (1963 – present) is an historian, academic and philosopher who specialises in understanding the history of social and cultural phenomena. Her work has profoundly shaped our understanding of many fundamental aspects of human experience.

Joanna Bourke was born in New Zealand, and lived in Zambia, Solomon Island, and Haiti as a young child. She graduated from Auckland University with a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Arts in history, and went on to complete her PhD at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra.

The dark parts of human experience

After writing her dissertation, titled Husbandry to Housewifery: Rural Women and Development in Ireland, 1890-1914 (1989), Bourke became interested in the experiences of men and women during wartime. Her work as a social and cultural historian has led her down a path of dealing with some of the less pleasant parts of being human, including topics such as pain, killing, war, violence, fear and rape. Bourke has been drawn to these elements of human experience because she feels that “these are the disciplines that have the most to offer us in terms of intellectual responses to current crises.”

Bourke’s book An Intimate History of Killing (1999) asks the question: what are the factors within society and in a war that turn a regular person into a good killer, or more politely, a good soldier? To answer her question, she uses excerpts from diaries, letters, memoirs and reports of Australian, British and American veterans of WWI, WWII and the Vietnam war. Bourke concludes that ordinary, gentle human beings can (and often do) become enthusiastic killers during a war because the structure of war encourages soldiers to feel pleasure from killing.

Some of her writing is also born out of personal experience. After a massive operation and a broken morphine drip, Bourke started thinking about pain and how difficult it is to describe in the English language. In her book The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers (2014), she concludes that “it is useful to think about pain in adverbial terms” because “it describes the way we experience something, not what is experienced.” As well as tracing the history of pain from the 1800s to present, she also details how factors such as race, class, gender and age have influenced the medical treatment of pain and often resulted in cruel abuse and neglect.

“Life’s too short for second editions.”

Joanna Bourke’s academic interests are vast. She has written 13 books and published over 100 articles, often tackling controversial and taboo topics.

In her recent book Loving Animals: On Beastiality, Zoophilia and Post Human Love (2020), Bourke argues that we should take a more nuanced approach to how we understand loving relationships between humans and non-human animals. When we take this more nuanced approach, Bourke finds that we are able to gain a clearer understanding of the nature of relationships, love and what we owe each other.

“I will be suggesting that animals are actors in society. This serves to challenge the anthropocentrism of history, human exceptionalism, and the idea that ‘culture’ is an entirely human preserve.”

Bourke begins by pointing out that “studies suggesting a link between bestiality and psychosis should be treated with caution due to sampling bias, because they were conducted on people already within the penal system, rather than a cross-section of the population.” She calls us to think about how we can so freely say that we love our pets, but turn a blind eye to slaughterhouses and factory farming. Bourke wants us to ask: what does it mean to love a non-human animal, and more broadly, what does it mean to love?

When we remove human exceptionalism from our understanding of human-animal relationships (which Bourke urges that we must), we can begin to think more about what we owe animals and how moral attitudes such as care, compassion, affection and pleasure are not unique to human beings.

Current work

Bourke is currently a professor of history at Birkbeck, University of London in England. She is also the Principal Investigator for a project called SHaME, or Sexual Harms and Medical Encounters. The project explores the medical and psychiatric aspects of sexual violence, with the aim of moving beyond the shame of sexual assault and address it as a global health crisis.

Her newest book Disgrace: Global Reflections on Sexual Violence, which has been partially motivated by her work with SHaME, will be available for purchase in Australia on August 15.

Joanna Bourke presents The Last Taboo as part of Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Tyson Yunkaporta

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to deal with people who aren’t doing their bit to flatten the curve

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Finance businesses need to start using AI. But it must be done ethically

Finance businesses need to start using AI. But it must be done ethically

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 2 AUG 2022

Banking and finance businesses can’t afford to ignore the streamlining and cost reduction benefits offered by Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Your business can’t effectively beat the competition marketing any product in the 21st century without using big data and AI. Given the immense amount of consumer data available – and the number of channels, segments and competitors – marketers need to use AI and algorithms to operate successfully in the online environment.

But AI must be used prudently. Business managers must be meticulous in setting up rules for the algorithms’ decision making to prevent AI, which lacks a human’s inherent moral and ethical guiding force, from targeting ads towards unsuitable or vulnerable customers, or making decisions that exacerbate entrenched racial, gender, age, socio-economic, or other disparities and prejudices.

The Banking and Finance Oath’s 2021 Young Ambassadors recognised a gap in the research and delivered report: AI driven marketing in financial services: ethical risks and opportunities. It unravels the complexities of AI’s impact across the financial services industry and government, and establishes a framework that can be applied to other contexts.

In a marketing environment, AI can be used to streamline processes by generating personalised content for customers or targeting them with individual offers; leveraging customers’ data to personalise web and app pages based on their interests; enhancing customer service with chatbots; and supporting a seamless purchasing journey from phone to PC to in-person at a storefront.

Machine learning algorithms draw from immense data pools, such as customers’ credit card transactions and social media click-throughs to predict the likelihood of customers being interested in a product, whether to show them an ad and what ad to show them. But there are ethical risks to navigate at every step – from the quality of the data used to how well the developers and business managers understand the business objectives.

Using AI for marketing in financial services comes with two significant risks. The first is the potential for organisations to be seen as preying on people in vulnerable circumstances.

AI has no moral oversight or human awareness – it simply crunches the numbers and makes the most advantageous and profitable decision to lead to a sales conversion.

And if that decision is to target home loan ads at people going through a divorce or a loved one’s funeral, or to target credit card ads at people who are unemployed or living with addiction, without proper oversight, there’s nothing to stop it.

The other risk is the potential for data misuse and threats to privacy. Customers have a right to their own data and to know how it’s being used – and what demographics they’re being placed in. If your data’s out of date or inaccurate, or missing in sections, you’ll be targeting the wrong people.

All demographics – including racial background, socio-economic status, and individual psychological profile – have the potential to be misused by AI to reinforce gender, racial, age, economic and other disparities and prejudices.

Most ethical failings in AI-driven marketing campaigns can be traced back to issues with governance – poor management of data and lack of communication between developers and business managers. These data governance issues include: siloed databases that don’t share definitions; datasets that don’t refresh quickly enough and become outdated; customer flags that are incorrect or missing; and too many people being designated as data owners, resulting in the deferral of responsibility.

In human driven decision making, there’s a clear line of command, from the Board, to management, to the frontline team. But in AI-driven decision making, the frontline team is replaced by two teams – the AI developers and the team of machines.

Communication gaps emerge where management may not be familiar with instructing AI developers and the field’s highly technical nature, and the developers may not be familiar with the jargon of the business. Training across the business can act to fill these gaps.

Before any business begins to integrate AI into its marketing (and overall) strategy, it’s crucial that it adopt a set of basic ethical principles, these being:

- Beneficence (or do good): personalise products to improve the customer’s experience and improve their financial literacy by delivering targeted advice.

- Non-maleficence (or do no harm): ensure your AI marketing doesn’t target customers in inappropriate or harmful ways.

- Justice: ensure your data doesn’t discriminate based on demographics and exacerbate racial, gender, age, socio-economic or other disparities or stereotypes.

- Explicability: you need to be able to explain how your AI system makes the decisions it does and the relation between its inputs and outputs. Experts should be able to understand its results, predictions, recommendations and classifications.

- Autonomy: at the company level, governance processes should keep humans informed of what’s happening; and at a customer level, responsible decision making should be supported through personalisation and recommendation tools.

The reality is that no business can afford to ignore the benefits AI offers, but the risks are very real. By acknowledging the ethical issues, businesses can seize the opportunities while mitigating the risks, benefiting themselves and their customers.

Download a copy of the report here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The 6 ways corporate values fail

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Society + Culture

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology