It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Tim Soutphommasane 25 NOV 2020

Citizenship isn’t often the stuff of inspiration. We tend to talk about it only when we are thinking of passports, as when migrants take out citizenship and gain new entitlements to travel.

When we do talk about the substance of citizenship, it often veers into legal technicalities or tedium. Think of the debates about section 44 of the Constitution or boring classes about the history of Federation at school. Hardly the stuff that gets the blood pumping.

Yet not everything that’s important is going to be exciting. The idea of citizenship is a critical foundation of a democratic society. To be a citizen is not merely to belong to such a society, and to enjoy certain rights and privileges; it goes beyond the right to have a passport and to cast a vote at an election.

To be a citizen includes certain responsibilities to that society – not least to fellow citizens, and to the common life that we live.

Citizenship, in this sense, involves not just a status. It also involves a practice.

And as with all practices, it can be judged according to a notion of excellence. There is a way to be a citizen or, to be precise, to be a good citizen. Of course, what good or virtuous citizenship must mean naturally invites debate or disagreement. But in my view, it must involve a number of things.

There’s first a certain requirement of political intelligence. A good citizen must possess a certain literacy about their political society, and be prepared to participate in politics and government. This needn’t mean that you can only be a good citizen if you’ve run for an elected office.

But a good citizen isn’t apathetic, or content to be a bystander on public issues. They’re able to take part in debate, and to do so guided by knowledge, reason and fairness. A good citizen is prepared to listen to, and weigh up the evidence. They are able to listen to views they disagree with, even seeing the merit in other views.

This brings me to the second quality of good citizenship: courage. Citizenship isn’t a cerebral exercise. A good citizen isn’t a bookworm or someone given to consider matters only in the abstract. Rather, a good citizen is prepared to act.

They are willing to speak out on issues, to express their views, and to be part of disagreements. They are willing to speak truth to power and willing to break with received wisdom.

And finally, good citizenship requires commitment. When a good citizen acts, they do so not primarily in order to advance their own interest; they do what they consider is best for the common good.

They are prepared to make some personal sacrifice and to make compromises, if that is what the common good requires. The good citizen is motivated by something like patriotism – a love of country, a loyalty to the community, a desire to make their society a better place.

How attainable is such an ideal of citizenship? Is this picture of citizenship an unrealistic conception?

You’d hope not. But civic virtue of the sort I’ve described has perhaps become more difficult to realise. The conditions of good citizenship are growing more elusive. The rise of disinformation, particularly through social media, has undermined a public debate regulated by reason and conducted with fidelity to the truth.

Tribalism and polarisation have made it more difficult to have civil disagreements, or the courage to cross political divides. With the rise of nationalist populism and white supremacy, patriotism has taken an illiberal overtone that leaves little room for diversity.

And while good citizenship requires practice, it can all too often collapse into curated performance and disguised narcissism: in our digital age, some of us want to give the impression of virtue, rather than exhibit it more truly.

Moreover, good citizenship and good institutions go hand in hand.

Virtue doesn’t emerge from nowhere. It needs to be seen, and it needs to be modeled.

But where are our well-led institutions right now? In just about every arena of society – politics, government, business, the military – institutional culture has become defined by ethical breaches, misconduct and indifference to standards.

And where can we in fact see examples of the common good guiding behaviour and conduct? In a society where public goods have been increasingly privatised, we have perhaps forgotten the meaning of public things. Our language has become economistic, with a need to justify the economic value of all things, as though the dollar were the ultimate measure of worth.

When we do think about the public, we think of what we can extract from it rather than what we can contribute to it.

We’ve stopped being citizens, and have started becoming taxpayers seeking a return. It’s as though we’re in perpetual search of a dividend, as though our tax were a private investment. As one jurist once put it, tax is better understood as the price we pay for civilisation.

But our present moment is a time for us to reset. The public response to COVID-19 has been remarkable precisely because it is one of the few times where we see people doing things that are for the common good. And good citizens, everywhere, are rightly asking what post-pandemic society should look like.

The answers aren’t yet clear, and we all should consider how we shape those answers. It may just be the right time for us to take citizenship seriously again.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Measuring culture and radical transparency

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Do we have to choose between being a good parent and good at our job?

BY Tim Soutphommasane

Tim Soutphommasane is a political theorist and Professor in the School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Sydney, where he is also Director, Culture Strategy. From 2013 to 2018 he was Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission. He is the author of five books, including The Virtuous Citizen (2012) and most recently, On Hate (2019).

Ethics Explainer: Consent

In many areas of life, being able to say “yes”, to give consent, and mean it, is crucial to having good relationships.

Business relationships depend on it: we need to be able to give each other permission to make contracts or financial decisions and know that the other person means it when they do.

It’s crucial to our relationships with experts who we rely on for critical services, like doctors, or the people who manage our money for us: we need to be able to tell them our priorities and authorise the plans they devise in light of those priorities. And romantic relationships would be nothing if we couldn’t say “yes” to intimacy, sexuality, and the obligations we take on when we form a unit with another person.

Giving permissions with a “yes” is one of our most powerful tools in relationships.

Part of that power is because a “yes” changes the ethical score in a relationship. In all the examples we’ve just seen, the fact that we said “yes” makes it permissible for another person to do something to or with us – when without our “yes”, it would be seriously morally wrong for them to do that very same thing. This difference is the difference of consent.

Defining Consent

Without consent, taking someone’s money is theft: with consent, it’s an investment or a gift. Without consent, entering someone’s home is trespass. With consent, it’s hospitality. Without consent, performing a medical procedure on someone is a ghoulish type of battery. With it, it’s welcome assistance.

The same action looks very morally different depending on whether we have said “yes”. This has led some moral philosophers to remark that consent is a kind of “moral magic”.

Interestingly, there are times when this moral magic can be cast even when a person has not said “yes”. In the political arena, for instance, many philosophers think it doesn’t take very much for you to have consented to be governed. Simply by using roads, or not leaving the territory your government controls, you can be said to have consented to living under that government’s laws.

The bar for what counts as consent is set a lot higher in other areas, like sexual contact or medical intervention. These are cases when even saying “yes” out loud might not be enough to cast the “moral magic” of consent: we can say “yes”, but still not have made it okay for the other person to do what they were thinking of doing.

For instance, if a person says “yes” to sex or to get a tattoo because they are drunk, at gunpoint, ill-informed, mistaken, or simply underage, most ethicists agree it would be wrong for a person to do whatever they have said “yes” too. It would be wrong to give them the tattoo or try to have sex with them, because even though they’ve said “yes”, they haven’t really given consent.

This leads philosophers to a puzzle. If saying “yes” alone isn’t enough for the moral magic of consent, what is?

Do we need the person to have a certain mental state when they say “yes”? If so, is it the mental state, the combination, or just the “yes” that really matters? This is a long and wide-ranging debate in philosophical ethics with no clear answer.

Free and Informed

Recently ethicist Renee Bolinger has argued that the real question is not what consent is, but how best to avoid the “moral risk” of doing wrong. She argues that in this light, we can see that what matters is not what consent is, but what our rules around consent should be, and those rules should consider consent a ‘performance’, or an action, such as speaking or signing something.

Some policy efforts have tried to come up with “rules about consent” that codify when and why a “yes” works its moral magic. There is the standard of “free and informed” consent in medicine, or “fair offers” in contracts law. Ethicists, however, worry that these restrictions are under-described, and simply push the important questions further down the line. For instance, what counts as being informed? What information must a person have, for their “yes” to count as permission?

We might think that knowing about the risks is important. Perhaps a person needs to know the statistical likelihood of bad outcomes. However, physicians know that people tend to over-prioritise relatively small risks, and in emotional moments can be dissuaded from a good treatment plan by hearing of “a three in a million” risk of disaster. So would knowledge of risk be sufficient for informed consent, or do we need to actually know the probability?

There is a final important question for our thinking about consent. Whatever consent is, are there actions you cannot consent to?

A famous court case called R v Brown established in 1993 that some levels of bodily harm are too great for a person to consent to, whether or not they would like to experience that harm. In any area of consent – medicine, financial, sexual, political – this is an important and open question.

Should people be able to use their powers of consent to do harm to themselves? The answer may depend on what we mean by harm.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethical issues and human resource development: some thoughts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to deal with an ethical crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

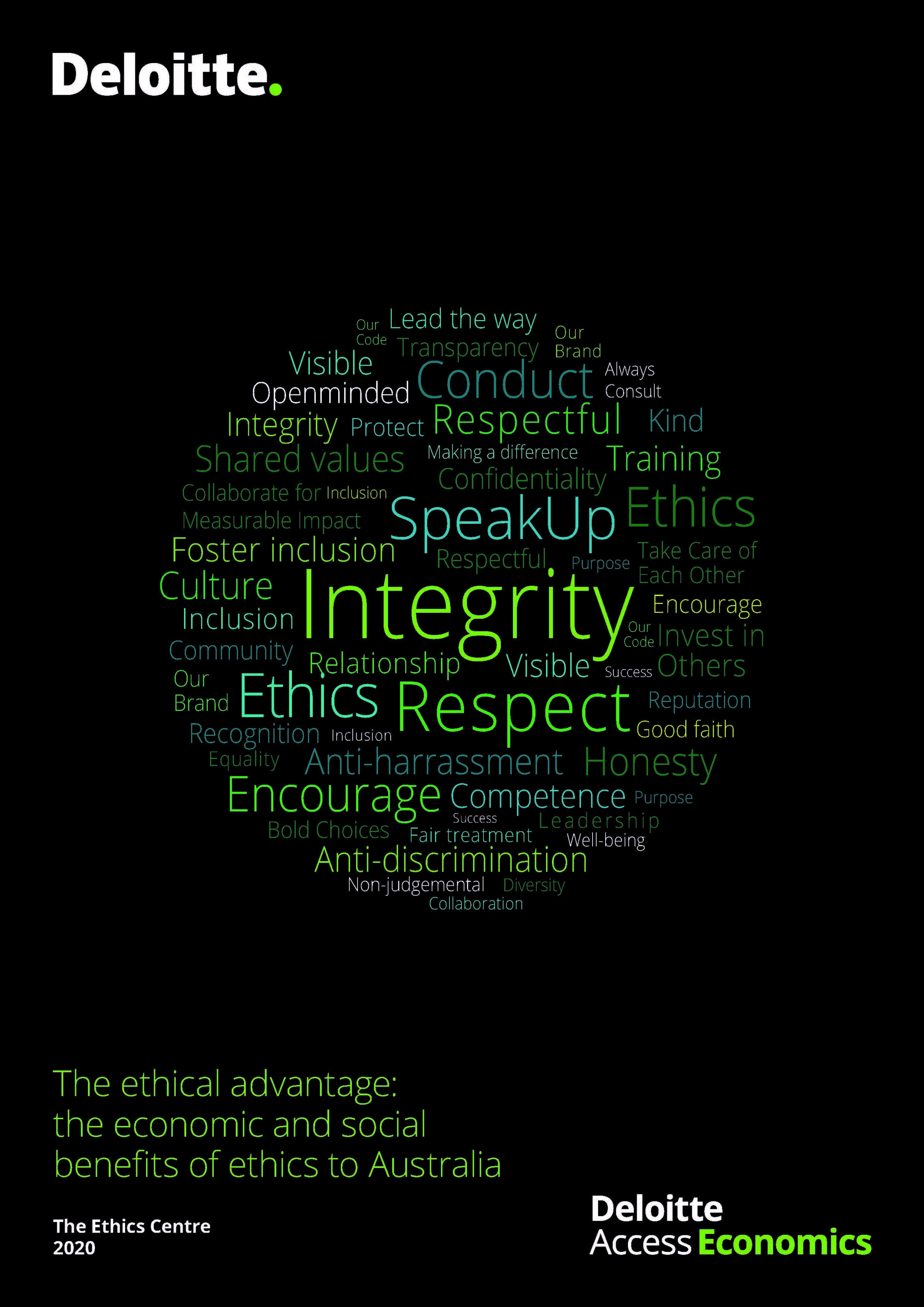

There’s something Australia can do to add $45b to the economy. It involves ethics.

There’s something Australia can do to add $45b to the economy. It involves ethics.

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 29 OCT 2020

Australia faces a perfect storm. An economic deficit, a global pandemic, an uncertain future of work, and long-term social and environmental change around the climate crisis and reconciliation with Indigenous Australians to name but a few.

Adding to this magnitude of challenges are the low levels of trust Australians have in our leaders and our neighbours. In fact, research has found that only 54% of Australians generally trust people they interact with, and as a nation we score ‘somewhat ethical’ on the Governance Institute’s Ethics Index.

How do we navigate the road ahead? One thing is abundantly clear: we need better ethics. That’s why we commissioned Deloitte Access Economics to find out the economic benefits of improving ethics in Australia.

The outcome is The Ethical Advantage, a report that uses three new types of economic modelling and a review of extensive data sets and research sources to mount the case for pursuing higher levels of ethical behaviour across society.

For the first time, the report quantifies the benefits of ethics for individuals and for the nation. The ethical advantage is in, and the findings are compelling. They include:

A stronger economy: If Australia was to improve ethical behaviour, leading to an increase in trust, – average annual incomes would increase by approximately $1,800. This in turn would equate to a net increase in total incomes of approximately $45 billion.

More money in Australians pockets: Improved ethics leads to higher wages, consistent with an improvement in labour and business productivity. A 10% increase in ethical behaviour is associated with up to a 6.6% in individual wages.

Better returns for Australian businesses: Unethical behaviour leads to poorer financial outcomes for business. Increasing a firm’s performance based on ethical perceptions, can increase return on assets by approximately 7%.

Increased human flourishing: People would benefit from improved mental and physical health. There is evidence that a 10% improvement in awareness of others’ ethical behaviour is associated with a greater understanding one’s own mental health.

The report’s lead author and Deloitte Access Economics partner, Mr John O’Mahony, said:

“No one would seriously argue that pursuing higher levels of ethical behaviour and focus was a bad thing, but articulating the benefits of stronger ethics is more challenging.”

“Our report examines the case for improving ethics as a way of addressing these broader economic and social challenges – and the nature and extent of the benefits that would accrue to the nation if we got this right.”

The report also identifies five inter–linked areas for improvement for Australia and its approach to ethics, supported by 30 individual initiatives:

- Developing an Ethical Infrastructure Index

- Elevating public discussions about ethics

- Strengthening ethics in education

- Embedding ethics within institutions

- Supporting ethics in government and the regulatory framework

The findings and recommendations demonstrate the value of The Ethics Centre’s continued contribution to Australian life. For thirty years, The Ethics Centre has aimed to elevate ethics within public debate, organisations, education programs and public policy. Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, Dr Simon Longstaff said the findings validate the impact of those activities and reveals the potential that can be unlocked with greater support.

“The compelling moral argument that ethical behaviour binds a society and its institutions in a common good is now, thanks to Deloitte Access Economics’ research and modelling, also a compelling economic argument. Best of all, we need not be perfect – just better.”

A copy of The Ethical Advantage can be found at this link.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why the future is workless

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Reports

Business + Leadership

Ethics in the Boardroom

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Should I have children? Here’s what the philosophers say

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Our economy needs Australians to trust more. How should we do it?

Our economy needs Australians to trust more. How should we do it?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Matthew Beard 29 OCT 2020

Imagine for a moment that your neighbour is a sweet, polite elderly man.

His partner has died and he lives alone. He has no family to speak of, and one day, his lifelong habit of purchasing lottery tickets pays off. He wins $50 million.

Suddenly, your brain starts ticking over. Statistically speaking, your neighbour doesn’t have too many years left. And when he dies, he’s likely to leave behind an enormous inheritance. What if you were the person he trusted to bequeath some of his wealth to? What would you do to earn his trust with so much on the line? Would you lie? Manipulate?

It’s important for us to ponder this, because new research from The Ethics Centre suggests Australia finds itself in a similar situation. According to figures produced by Deloitte Access Economics, if Australia was able to elevate its national trust score from 54% – its current level – to 65%, it would unlock $45 billion in GDP.

With so much on the line, it would be understandable to see political leaders and businesses looking for the fastest, most effective way to build trust. We assume more trust is better than less trust. However, that’s an assumption we need to be cautious of. “I have an issue with the connection of trust with growth,’ says Rachel Botsman, Trust Fellow at Oxford University’s Said Business School and author of Who Can You Trust?

“Trust,” Botsman explains, “is not always the goal. It’s intelligently placed trust.”

Consider this from the perspective of the elderly man in our imaginary story. For him, growing more trusting of his neighbour is only a good thing if his neighbour deserves to be trusted. If he trusts a dishonest neighbour who just wants his inheritance, that growth in trust isn’t something to celebrate. In fact, this increased trust is dangerous to him.

When we take the thought experience and apply it to Australia’s economy, the point still stands. As individuals, we don’t want to be more trusting of governments, organisations or markets unless they deserve our trust. Even if higher trust levels are good for GDP, it’s only good for us if it’s earned in the right way – ethically.

“Trust is the social glue of society,” says Botsman. “To manipulate that – because it can so easily be manipulated and tracked in terms of growth – feels wrong.”

Botsman has spent years speaking to businesses and governments about trust and encouraging them to value it. Today, she’s worried lots of her audience have missed her message.

She says, “I start this conversation about trust in organisations, and then a year later it’s become a commercial strategy. They’re trying to assess the return on investment, and, it’s like ‘no, that’s not that’s not I meant! When I meant ‘value’ I didn’t mean economic growth.”

Botsman worries about the effects of framing discussions around trust in the language of business and capitalism. Trustworthy decisions “might result in some kind of short-term financial loss, so it’s problematic that loss is caught up in the language of finance and money.”

Katherine Hawley, Professor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews, and author of How to Be Trustworthy, defines trustworthy people as those who avoid unfulfilled commitments and broken promises. Basically, Hawley sees trustworthiness as the absence of untrustworthiness. Untrustworthy people make promises they can’t keep and fail to meet their obligations. If you don’t do these things, you’re probably a trustworthy person.

However, Hawley is quick to add that being trustworthy doesn’t necessarily guarantee that people will actually trust you. “There can be a significant gap between whether you are trustworthy and whether people can see you to be trustworthy,” she says.

Botsman agrees, “one of the hardest things to get your head around with trust is that even if you behave in a way that you think is the most trustworthy, you are still not in control of whether that person gives you their trust.”

This is one reason why Botsman has begun to advise organisations to stop thinking about building trust, and start thinking about acting with integrity, “because the language of intentions, motives, honesty and whether they best serve the interests of customers is much harder for companies to hide behind than questions of trust.”

A focus on integrity also helps prevent us from seeking trust in an undifferentiated way – not caring whether it’s intelligent trust or not. It shifts our focus away from what other people are thinking and toward our own activities.

“You would hope that people would want to be ethical, not just seem to be ethical,” says Hawley. However, in case that principle doesn’t persuade some people, Hawley offers a word of caution. She describes a phenomenon called ‘betrayal aversion’, “People get more angry in situations in which they first trusted and then found out that was a mistake than when they just didn’t trust in the first place.”

This idea, which comes from the work of behavioural economist Cass Sunstein, is a sober warning to those who see trust as a tool – something to be collected because it’s useful for growth, profit or advantage. “The risk for these businesses is that if people come to find out this was going on, or even find out that was their motive, then that could be worse for them.”

There is a strong moral argument – especially during a recession – for pursuing economic growth. For some, the importance of growth is likely to be enough to justify pursuing trust by any means possible. However, Hawley gives us a good reason to pause.

Chasing trust in the wrong way is something untrustworthy people do. And that makes the trust you accrue a bad investment – it’s fragile. The slower, more carefully accumulated relational trust might not offer the same returns in the short term, but it’s based on something more stable: ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to improve your organisation’s ethical decision-making

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethics of workplace drinks, when we’re collectively drinking less

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s fiscal debt will cost Gen Z’s future

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Corporate tax avoidance: you pay, why won’t they?

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Businesses can’t afford not to be good

Businesses can’t afford not to be good

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 28 OCT 2020

A famous New Yorker cartoon depicts a businessman sitting by a campfire, still in his suit, speaking to two young children.

“Yes, the planet got destroyed,” he concedes. “But for a beautiful moment in time we created value for shareholders.”

The logic seems perverse, but more the worrying reality is that in reality, it’s quite pervasive. We’ve seen Royal Commissions into aged care and financial services, growing pressure on tech companies to address social issues and the overwhelming pressure for businesses to address climate change. Despite this, we have seen very few organisations making meaningful investments into ethics.

We should worry that we’re living in the campfire CEO’s beautiful moment in time.

At The Ethics Centre, we’ve spent over thirty years getting into what makes organisations tick. How they’re motivated, what they care about and what goals they serve. Time and again, we’ve seen how the real desire to act with integrity, uphold customer interests and attend to vulnerable people is pitted against business imperatives.

No matter how many scandals we see, the message still seems to be the same: while you’re successful, you can be ethical. But if you’re not successful, you’ll need to park your ethics till you are.

This is the campfire CEO’s logic. By focussing on the (often illusory) short–term value captured that ethical shortcuts can at times promise, businesses lose out in the long run. And thanks to new research commissioned by The Ethics Centre, we now know exactly how much businesses are losing out on by giving away the Ethical Advantage. We also know how much courageous businesses gain by making ethics a priority.

Research by Deloitte Access Economics has revealed that businesses who are seen as ethical – fair in business, transparent and open – enjoy a higher returns on assets. They are also less likely to have staff experiencing mental health issues, because when we believe the people around us are ethical, we experience less mental health challenges.

What’s more, if we are able to improve the ethical standing of enough people and businesses, we’ll not only boost business returns, we’ll improve wages and GDP. Nice guys are the tortoises of the business world. They finish first in the long run.

Cris Parker, head of the Ethics Alliance, a community of businesses committed to a more ethical way of working, says “when organisations make a concerted effort to invest in ethics, they create an environment where good intentions are just the beginning.”

She believes it is when ethics shifts from being a leader’s obligation to being a shared responsibility that real change happens. “It’s the cumulation of every employee serving that purpose, doing the right thing that really makes the difference. “

Realising these benefits requires us to recognise the source of the campfire CEO’s error: economic narrow-mindedness. The willingness to destroy the planet in favour of business returns (which is, in fairness, a caricature of most of today’s business leaders) demonstrates a failure to recognise how dependent our economy is on the wellbeing of the planet.

Similarly, pursuing economic returns without considering the means by which they’re achieved ignores the crucial role that trust, integrity and character plays in preserving our economy.

We don’t trade with people we think are going to betray us. We don’t invest when we can’t trust others to be careful with our investments.

Michelle Bloom leads The Ethics Centre’s consulting and leadership team. She believes ethical improvement requires us to embrace complexity rather than looking for simple solutions.

“Today, business leaders are dealing with very complex operating environments where action and bottom–line results are rewarded over reflection, perspective seeking and co-ordination. This haste to decide without deliberation limits leaders to mechanistic solutions where systemic, novel and context–specific approaches are required.”

Unfortunately, realising these benefits is harder than it seems.

Much like an optical illusion you can only properly see by looking away from it, the economic benefits of ethics are only likely to be realised by those who seek it with integrity rather than a hunger for profit.

Hypocrites and cynics need not apply for the ethical advantage. But for the sincere and the patient, results will come in time. However, it will require businesses to campaigning not just for their industries to be better as a whole, but for the large-scale Ethical Infrastructure investments Australia needs to ensure we have trustworthy markets, institutions and systems.

For Michelle Bloom, alongside large-scale change, organisations need to get their own house in order. “Embedding an Ethics Framework into the organisational system and its processes is the first step,” she says. Next is developing your leaders’ systemic and ethical thinking to make good decisions in complexity as well as ensuring the culture of the organisation aligns to your Ethics Framework.”

Each of these steps, alongside developing the capacity for good decision-making and embedding ethics into the design of all products and services, are markers of the kind of integrity that grants the Ethical Advantage.

In our line of work, we often hear from so-called pragmatist who see ethics as a nice idea that doesn’t work in the real world. The numbers are in, and it turns out the most pragmatic thing to do is make ethics a top priority. Anything else would be bad business.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

This tool will help you make good decisions

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethical issues and human resource development: some thoughts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Between frenzy and despair: navigating our new political era

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Ethical Infrastructure

Ethics Explainer: Ethical Infrastructure

ExplainerBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 27 OCT 2020

When we think about the kinds of things a society needs for its survival and flourishing, we tend to begin with the basic necessities.

A society needs enough food to feed everyone, road and transport infrastructure, housing. It needs laws to manage how people treat one another, systems of government to make decisions. In a modern society, complex communications and other forms of technical infrastructure are required.

Each of these this is a component of a society’s infrastructure. Each is essential to the common good, survival and wellbeing of a society. However, just as essential for the wellbeing of a society is ethical infrastructure – the formal and informal means by which society regulates the use of power by both public and private institutions to ensure it serves the common good.

The term ethical infrastructure has been used in a number of countries around the world, including The United States of America. However, it has typically been used to refer to systems of control, compliance and risk management. There is an opportunity to expand the idea of ethical infrastructure so it does not simply refer to the basic rules of public service.

A society can have a clear set of rules and principles about appropriate spending, disclosure of interests and so on, and still not have systems and institutions that serve the common good. We need only look at the United States for proof of this.

This is why it is better to consider ethical infrastructure to be a collection of institutions, systems, norms and processes that we use to ensure not only that society is operating effectively, but that it is operating ethically.

To understand why this is necessary, consider the fact that there is a person or group who is responsible for, and in control of, each piece of social, physical or digital infrastructure we have and need. This control confers power. The power to give or deny essential resources to some groups, to favour some people over others or to mismanage those resources due to incompetence, laziness or selfishness.

Handing this kind of power over to somebody without some assurance they will use it well would be reckless and foolish. Indeed, some of the most influential voices in Western political philosophy – Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Rawls – have argued that it’s only when the powerful are willing to act in the interests of those they are meant to serve that they should have any power at all. Ethical infrastructure refers to the means by which a society can ensure power is exercised in the common interest, and take meaningful action when it is not.

A clear example of a piece of ethical infrastructure would be laws, policies and systems protecting the actions of whistleblowers, who draw attention to unethical behaviour – often by the powerful. Many organisations lack appropriate systems and processes for employees to flag ethical issues, and even if they have these processes, there are often cultural factors that mean those processes don’t have the results they should. This can drive some whistleblowers to look for other avenues outside their organisation, but often do not feel supported – practically or legally – in doing so.

Thinking about an issue like this as a challenge of ethical infrastructure helps us see it as a systemic issue. It is not simply a matter of new laws. We also need to normalise new ways of thinking about dissenting, concerned or outspoken staff within our organisations.

We need to ensure individuals have the training and support they need to identify and draw attention to ethical issues and we must have appropriate accountability in cases where it appears important information has been covered up or kept secret. This complex and powerful network of norms, policies, institutions, processes and people is a society’s ethical infrastructure.

Each aspect of a society’s infrastructure is designed to allow its citizens to flourish: provided with the means to live prosperously, confidently, safely and well. Ethical infrastructure serves this goal in two ways. First, it ensures the other aspects of our infrastructure are serving everyone’s needs, and second, it gives people the confidence to take risks, act creatively and magnanimously, trust in their neighbours, leaders and institutions and feel confident in theirs and their loved ones futures.

Because without this, no amount of sophisticated infrastructure will secure what we’re all searching for: a life worth living.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Office flings and firings

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethics of making money from JobKeeper

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Self-interest versus public good: The untold damage the PwC scandal has done to the professions

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccination guidelines for businesses

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The Ethical Advantage

The ethical advantage: the economic and social benefits of ethics to Australia

We know what ethical failure costs – look at the billions of dollars paid by financial institutions in penalties and customer remediation since Hayne. But what are the economic benefits of ethical best practice? What can we gain economically by being more ethical as a nation?

Turning around the loss of trust in government, corporations and institutions could deliver Australians significant economic and social dividends. The Ethical Advantage’s exclusive new economic modelling by Deloitte Access Economics shows that if our leaders, businesses, institutions and everyday Australians made more ethical decisions, our GDP, wages, corporate returns and mental health would improve.

For the first time, the report quantifies the benefits of ethics for individuals and for the nation. An increase in ethical behaviour could raise Australians’ average income by $1,800 a year, lifting GDP by $45 billion. An increase in a company’s performance based on ethical perceptions can increase return on assets by about 7%. The modelling also reveals a host of individual and collective benefits for Australians across wages, trust and mental health.

The report also identifies five interlinked areas for improvement for Australia and its approach to ethics, supported by 30 individual initiatives. Download a copy to learn more.

ECONOMIC ADVANTAGE

$45,000,000,000

Lifting Australia's trust levels to that of global leaders would increase the GDP by $45 Billion

BUSINESS ADVANTAGE

7%

Improving a businesses ethical reputation can lead to a 7% increase in return on assets (ROA)

INDIVIDUAL ADVANTAGE

2.7%

A 10% increase in ethical behaviour is associated with a 2.7% increase in individual wages ($23 bil accumulative)

“It is only right to examine how ethical-decision making benefits society. It is not surprising that some of the benefits are demonstrable in economic terms. As a result, purposeful investment to build ethical infrastructure makes sense for our societies and our economies. As we strive to prosper within planetary boundaries and achieve truly inclusive societies, there is urgency to build trust and the capacity navigate these complex challenges. The practical initiatives proposed in this report provide a blueprint for building the ethical infrastructure we need. The recommendations are farsighted in their aims, and their systematic pursuit cannot start soon enough.”

NATHAN FABIAN

Chief Responsible Investment Officer, Principles for Responsible Investment and Chair, European Platform for Sustainable Finance.

“This is a fascinating report showing the value – in every sense of the word – of embedding more ethical reasoning in daily life. I don't think I have ever seen quite such a broad, evidence-based, and wise account of the state of ethics in a society. Perhaps its most important message is that ethics, and ethical reflection, should just be part of everyday decision-making, rather than something to be contracted out to specialists, or worried about only when things have gone badly wrong. Here is an impressive call for a bit more thoughtful examination in every aspect of our public as well as our private lives.”

SIR GEOFFREY MULGAN

CBE, Professor of Collective Intelligence, Public Policy and Social Innovation, University College London

“While there is constant criticism that the school curriculum is overcrowded, this report presents robust arguments why skilling young people around ethical decision-making is to equip them with a capability that not only benefits society and communities, but their own future resilience and wellbeing. If we want to develop independent, life-long learners through our education system – engaged citizens who can operate effectively in a complex, fast-changing and dynamic society – a capacity to think ethically must be a compelling foundation. The Greeks knew it. This new report explains why we may need to rediscover it.”

MARK SCOTT

Secretary, NSW Department of Education

“As our society goes through a time of profound change, both locally and globally, it is timely to reflect on the importance of ethics. This study makes a powerful economic case for investing in the development or improvement of ethics in our society. The real challenge is how we improve our ethical behaviour, both individually and as a society. Directors, as leaders of their organisation, have a key role to play. The days when boards ‘commanded respect’ are over. Directors must approach their task of governance with humility seeking to earn the respect and trust of all their stakeholders. Learning how to deploy an ethical framework to guide decision making is key to ensuring decisions are made in the best interests of the organisation after due consideration is given to the interests of relevant stakeholders.”

JOHN ATKIN

Chair, Australian Institute of Company Directors

“The continuing discussion of the role of ethics and ethical decision making in all our institutions is so important in uncertain times. Most Australians are still not sure we trust our institutions and younger Australians are more cynical about the underlying frameworks used to make decisions and trade-offs. This dissonance is not healthy and needs to be part of our path forward from COVID crisis management and a multitude of royal commission findings into trust, ethical decision-making and choices made. We need to find a way to be our best selves, every day. We need ways of continuing visibility of the measures of ethical standards and to be held accountable for improvement across all industries and sectors in Australia.”

ANN SHERRY

Chair, Unicef Australia

“On the back of numerous royal commissions and recent corporate events, this timely and important report holds a mirror to those of us in the director community, challenging us to understand what we expect of our leadership in governance and whether we have met stakeholder ethical considerations. Do the existing power structures and leadership models reinforce inertia because they benefit ourselves and the status quo at the expense of ethical outcomes? If we do not address these issues, the increasing cynicism around our governance will render us ineffective over time. Are we worthy of the community's trust?”

MING LONG AM

Chair, AMP Capital Funds Management; Deputy Chair, Diversity Council of Australia

“Of all the things that keep a society together, none is more important than a shared sense of ethics. Without it there can be no trust or shared sense of purpose and so no prospect of facing the challenges or realising the opportunities ahead. This report both explains why ethics matter and what we can do to strengthen their central role in our society and economy. Its work on the economic benefits of ethical behaviour is ground-breaking. We should not need an economic rationale for ethical behaviour but by quantifying the economic benefits, this report adds a compelling strand to advocacy on why ethics are foundational.”

PETER VARGHESE

Chancellor, The University of Queensland

“This is a major reform initiative which opens the gates for deep cultural and social change based on a foundation of substantial economic benefit. Australia would be wise to embrace these principled imperatives.”

STEPHEN LOOSLEY

Senior Fellow, Australian Strategic Policy Institute

AUTHORS

Authors

John O'Mahony

John O’Mahony is a Partner at Deloitte Access Economics in Sydney and lead author of The Ethical Advantage report. John’s econometric research has been widely published and he has served as a Senior Economic Adviser for two Prime Ministers of Australia.

Ben?

John O’Mahony is a Partner at Deloitte Access Economics in Sydney and lead author of The Ethical Advantage report. John’s econometric research has been widely published and he has served as a Senior Economic Adviser for two Prime Ministers of Australia.

Download The Ethical Advantage Report

Berejiklian Conflict

Berejiklian Conflict

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 14 OCT 2020

The next phase in the political life of NSW Premier, Gladys Berejiklian, depends on answers to three questions.

First, was her former relationship with Daryl Maguire not just ‘close’ but, in fact, an “intimate personal relationship”? Second, did the Premier make or participate in any decisions that could reasonably be expected to confer a private benefit on Mr Maguire? Finally, if the answer is ‘yes’ to each of these questions, then did Ms Berejiklian declare her interest in the Ministerial Register of Interests and seek the permission of Cabinet to continue to act?

Nothing else matters – not the Premier’s choice of friends, not her judgement … only the answer to those three questions.

The reason for this can be found in the NSW Ministerial Code of Conduct (the Ministerial Code) which has the force of Law. As might be expected, the Ministerial Code imposes obligations that are in addition to and are more onerous than, those applying to Members of Parliament.

The Preamble to the Ministerial Code of Conduct says, amongst other things, that, “In particular, Ministers have a responsibility to avoid or otherwise manage appropriately conflicts of interest to ensure the maintenance of both the actuality and appearance of Ministerial integrity.” With that end in mind, the Code not only takes account of the personal interests of individual Ministers – but also those of members of their families. It is here that the precise nature of the Premier’s relationship with Mr Maguire risks becoming a matter of public, rather than personal, interest. This is because the Ministerial Code of Conduct defines a “family member”, in relation to a Minister, as including, “any other person with whom the Minister is in an intimate personal relationship”.

‘Intimate’ is not a word used in the ICAC hearing to describe the Premier’s relationship with Mr Maguire.

Instead, it was agreed that theirs had been a “close personal relationship” – the precise nature of which was never explained. However, the evidence suggested that the words ‘close’ and ‘intimate’ may have been synonymous. If so, then Mr Maguire will have fallen within the definition of ‘family member’ during the period of his relationship with the Premier.

However, this (in itself) is neither here nor there. The nature of Ms Berejiklian’s relationship with Mr Maguire was (and should have remained) an entirely private matter up until the point where the Premier became involved in any Ministerial decision that “could reasonably be expected to confer a private benefit” on Mr Maguire. Only then did the public interest become engaged.

So, did any such decisions come before the Premier (acting alone or in Cabinet) during the period of her relationship with Mr Maguire? And if so, did she declare her interest as she is required to do under the Ministerial Code? The matter would then have been in the hands of her Cabinet colleagues as the final provision of the Code states that, “a ruling in respect of the Premier may be given if approved by the Cabinet”.

The Premier obviously knew something of Mr Maguire’s hopes and plans – even if she thought them to be fanciful. She knew of his financial exposure and the material impact that NSW Government decisions might have on his personal wealth. We also know that, for a time, Mr Maguire was at the centre of the Premier’s private affections. The issue is not that the Premier would have acted against the public interest for the benefit of Mr Maguire. I sincerely doubt that she would ever do so. It is most importantly a question of what was done to ensure the maintenance of both the actuality and appearance of Ministerial integrity.

The Premier had a formal obligation to declare her relationship with Mr. Maguire if, a) it was intimate, b) she was involved in deciding any matter that could reasonably be expected to confer a private benefit on him. It was then up to her Cabinet colleagues to rule on how she should proceed from there. Beyond settling these questions, the public has no legitimate interest in the private life of Gladys Berejiklian – except, perhaps, to extend to her our sympathy if she has been drawn inadvertently into a web of grief spun by a former friend.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The 6 ways corporate values fail

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Economic reform must start with ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

United Airlines shows it’s time to reframe the conversation about ethics

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Recovery should be about removing vulnerability, not improving GDP

Recovery should be about removing vulnerability, not improving GDP

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance Cris Parker 29 SEP 2020

Vulnerability demands attention and, in the past, where profits were prioritised business was preoccupied and vulnerable customers harmed.

Because of Covid 19 we can expect to see more vulnerability with multiple drivers. The pandemic has reminded us that we can all be vulnerable if the right (or wrong) circumstances occur.

A year ago, your vulnerable customer probably didn’t look like my daughter and her friends: cashed-up twenty-somethings, single, easy going and living alone. Nor did a dual-income household with primary school-aged kids automatically raise any red flags.

However, we are now realising the various ways that changes in circumstances can quickly render us vulnerable in both financial and non-financial ways. The physical, emotional and financial impacts of the pandemic challenge business to find new ways to recognise and forecast when people are experiencing hardship. Not least because many people who find themselves in hardship may be less likely to seek support.

We live in a society where wealth is a sign of success – particularly for those who have grown accustomed to a certain level of financial wellbeing. In this context, to be labelled vulnerable is a suggestion that you have failed in some way. There’s an element of shame or even a stigma attached to the label.

Vulnerability is so often positioned through an economic lens, the term synonymous with poverty, diminished capacity or poor decision-making. This means singles struggling with the mental health impacts of isolation and parents collapsing under the pressure of home-schooling may baulk at the idea of being labelled ‘vulnerable’.

Our new reality also requires fresh approaches to handling people who have experienced a sudden change in fortune. People who managed just fine in the “gig economy” are now in a precarious position in “insecure employment”. Those who took on huge debts to buy homes in our major cities are also under extreme financial pressure as the economy continues to slide.

I recently participated in a discussion with customer advocates from the financial services sector. One advocate revealed that estimated calculations were that we can expect around 30,000 homes to be lost as a result of the pandemic. A month ago (which seems an age in COVID-time), the Lowy Institute reported the number of unemployed would soon exceed 1.3 million. The jobless rate will climb to 10 per cent by the end of the year and still be above 8 per cent by the end of 2021, according to the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). In short, all evidence points toward an explosion in the amount of vulnerable people businesses are dealing with.

“Measured as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per head, Australia’s average living standards are falling and will take several years to return to the pre-pandemic level,” says the institute’s John Edwards, a former member of the Board of the RBA, and Adjunct Professor with the John Curtin Institute of Public Policy at Curtin University.

Our economy’s health is measured by our GDP. It’s the magic acronym: – the more it goes up, the better off our society is, or so they say. However, given the anticipated explosion of vulnerable customers and people facing financial hardship, it might be worth revisiting the role GDP plays in our understanding of economic health.

If our GDP recovers, but we see minimal reduction in the amount of vulnerable people – financially vulnerable or otherwise – is this really a recovery at all?

Measuring a society’s health by GPD can be a useful rule of thumb, says business ethicist Dr Ned Dobos, Senior Lecturer in International and Political Studies at the UNSW Canberra. However, it would be “wrong-headed” to put too much faith in it, Dobos argues that we need different metrics than relative material wealth to measure how we are going.

Dobos points to the research conducted by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, showing that more money will only make people happier up to a certain point – around $US75,000. But while extra money may make them feel more successful, it will not make them feel happier beyond that threshold.

“We’re continuing to measure the welfare of our society in terms of GDP, even though GDP has no proven connection to our sense of wellbeing anymore,” he says.

“We have fetishised material wealth, even though it’s not connected to the things that ultimately matter.”

Dobos hopes that a silver lining from the pandemic will be that, as a community, we have more understanding of people who are unemployed and that we realise that poverty is not a character defect.

“Surely people, after a period of time, would have to appreciate that with a million people in this country unemployed, [unemployment] must be something that is not entirely within their control,” he says. “We can’t have that many degenerates.”

Susan Dodds, Professor of Philosophy at La Trobe University, agrees. She says she would like to see a recognition that attaining wealth requires a fair degree of luck, rather than it being something one “deserved”.

She would prefer the discussion of economics shift from GDP to “talking about what makes for a decent life.”

There are large numbers of people who are working as casual, low-paid, low-skilled, itinerant workers – moving between nursing homes. There’s a reason for that: they’re not doing it because: ‘gee whiz, I’d love the flexibility’,” says Dodds.

Dodds says the pandemic is an opportunity to have another look at what a reasonable expectation of profit is. “The idea that we can get, year-on-year, a two per cent reduction in our costs in order to get an inflationary increase in our profits, making me comfortable with the amount of dividend I get, is really exploitative.”

What gets measured gets done. If our recovery is determined exclusively in terms of GDP, it might mean creating more vulnerable people, as organisations are incentivised to pursue relentless growth.

There has been a global push for more purposeful capitalism; Blackrock CEO Larry Fink wrote a letter to 500 CEOs last year addressing this issue. Closer to home, this year New Zealand is the first western country to design its entire budget based on wellbeing priorities. “We’re embedding that notion of making decisions that aren’t just about growth for growth’s sake, but how are our people faring?” Ardern said.

The ACT has identified that economic conditions, important as they may be, are not the only factors that contribute to the quality of life of Canberrans. In releasing the Budget in March 2020, the ACT Chief Minister Andrew Barr stated, “We are more than an economy – we are an inclusive, vibrant and caring community where we aim for everyone to share in the benefits of a good life both now and in the future.” The ACT Wellbeing Framework will inform Government priorities, policies, investment decisions and Budget priorities.

In his recent Ted Evans lecture, economist Professor Ian Harper, an RBA board member, reminded economists to talk to the public, to keep in touch with what the community thinks are important priorities.

“Apart from anything else, you learn so much about what really matters for people. Whether it’s the level of minimum wages, a level of interest rates, how banks are supervised, where you can open a pharmacy, when you can open a supermarket or where you can get treated for infectious disease,” says Harpers.

“No one should be surprised that an economist should worry about the human dimension of his craft – social science, it may be, but economics started out as moral philosophy.”

“Our quest to raise community welfare cannot be divorced from its foundation in a moral calculus. More to the point, if it is divorced from its moral foundations, then economic policymaking is more likely to diminish than enhance economic welfare.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Reports

Business + Leadership

A Guide to Purpose, Values, Principles

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Accepting sponsorship without selling your soul

Big thinker

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The case for reskilling your employees

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

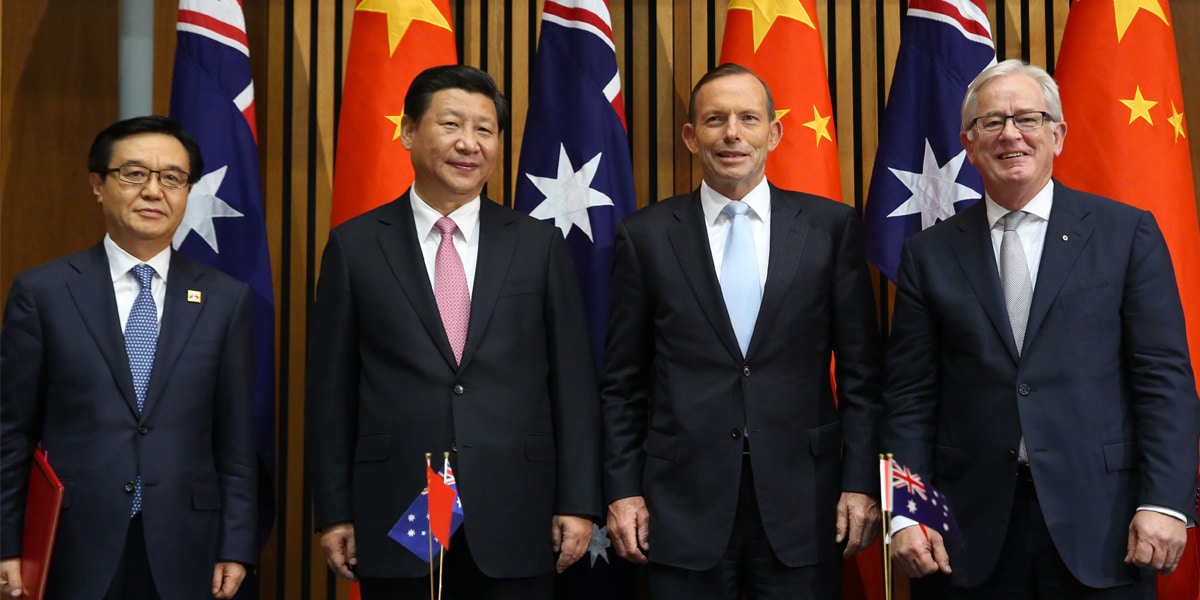

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Matthew Beard 17 SEP 2020

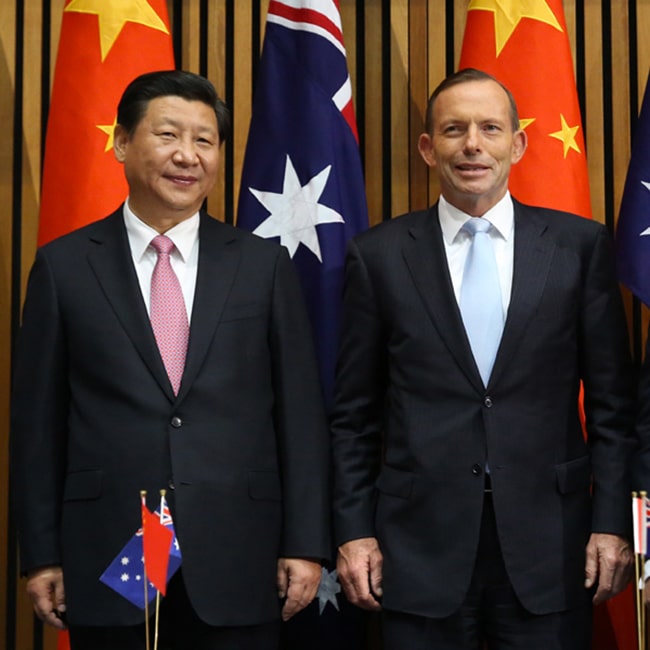

Former Aussie PM Tony Abbott’s recent appointment to an unpaid role as a trade adviser to the Johnson government in the UK has sparked controversy in both countries.

UK government MPs have continually been asked what it means to have a man who is, by the judgement of many in both countries, “a misogynist and a homophobe”, as well as a climate change denier and – more recently – sceptical about coronavirus lockdown measures.

In Australia, politicians, journalists and citizens have all questioned the appropriateness of a former Prime Minister accepting a position that leaves him serving a foreign government. Whilst Abbott has obligations under the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme that are designed to prevent conflicts of interest, there are many who believe Abbott is equipped with too much internal knowledge of Australia’s trade interests, internal party politics and regional issues in the Pacific – accrued as Prime Minister – for him to serve another government.

Given the range of questions that arise around both conflict and character, we made a list of some of the big ethical questions the Abbott situation brings up, and spoke to a few ethicists to help answer them.

1. Abbott is a private citizen now. Shouldn’t he be able to take any job he wants?

“Being Prime Minister isn’t like any other job,” says Hugh Breakey, a Senior Research Fellow at Griffith University’s Institute for Ethics, Governance and Law. “Abbott would have been privy to high level information and forward planning that he is obligated to hold secret.” If a potential employer of Abbott – whether in a paid role or not – would benefit from this situation, Breakey argues that it would give Abbott a conflict of interests.

But it’s not just a question of conflicts of interest. In situations like this, it is reasonable to consider whether this role was given as a “kind of payback for favourable treatment during his time in power,” Breakey says.

However, whilst Abbott’s appointment may generate potential conflicts of interest and are “legitimate lines of ethical inquiry”, Breakey believes they are not problems for Abbott’s appointment.

However, Simon Longstaff, executive director of The Ethics Centre, disagrees. “There just can be no guarantee that Britain’s interests will always coincide with Australia’s. Given this, the fact that one of our former Prime Ministers would ever serve a foreign power almost beggar’s belief,” he said.

2. If Abbott’s trade qualifications make him a good candidate, should we overlook his other beliefs and opinions?

“I believe that a representative of any country, in any honoured capacity like this one, should be a morally upstanding person. Tony Abbott is not that, given his history of misogyny, homophobia, and racism,” says Kate Manne, philosophy professor at Cornell University.

However, Hugh Breakey worries that an approach like this risks jeopardising our commitment to non-discrimination and supporting a diverse set of beliefs and ways of life. Sometimes, he says, ethics might require us to overlook the questionable beliefs of a potential political appointment.

“At least some of the views taken by Abbott on these matters have religious influences, and many similar (and, indeed, far more conservative) views are held by religious devotees across many of the world’s major faiths. Prohibiting from public offices and services all those who hold such views… would allow widespread religious discrimination.”

However, another complication arises when it comes to whose views and personality traits we tend to overlook. Cognitive biases, social norms and systemic beliefs like sexism and racism can mean we’re more likely to overlook controversial beliefs or difficult personalities when they belong to men, people who are straight or white.

Kate Manne suspects that “both women and non-binary people are far less likely to be viewed as truly qualified or competent, unless they’re also perceived as extraordinarily caring, kind, and what psychologists call ‘communal’.” She adds that the tendency to separate the professional and personal/political aspects of someone’s identity is “far less available to women and gender minorities.”

3. Should we label Abbott a misogynist or homophobe based only on his public comments and policies?

“The truth is, few people would know Tony Abbott well enough to say with any confidence what he truly feels or believes, and those who do know him paint a very different picture to the one sketched by his critics,” says Simon Longstaff. “A person can be opposed to same-sex marriage and yet not be a homophobe,” he adds.

However, for Kate Manne, the central question of misogyny or homophobia isn’t whether the person feels a certain way toward women or queer people, it’s what effect they have on those communities.

“Misogyny to me is not a personal failure or an individual belief system: it’s a system that polices and enforces a patriarchal order,” she says. “I define a misogynist in turn as someone who’s an ‘overachiever,’ or particularly active, in this system.”

Manne says, “misogyny on this view is less about what men like Abbott may or may not feel toward women, and more about what women face as a result of their toxic, obnoxious, and contemptuous behaviour.”

For Manne, this means Abbott can be reasonably called misogynist and homophobic on this basis. His status as a former PM and his very public comments have done considerable work to uphold a system that oppresses women and LGBTIQ+ people. She cites examples such as calling abortion the ‘easy way out’, standing next to a ‘ditch the witch’ sign or talking about feeling threatened by gay people as evidence of Abbott’s contributions.

4. How should we balance the need to reject some beliefs because they’re not morally acceptable or legitimate with our commitment to pluralism?

“Democracies gain critically in legitimacy by being able to conduct inclusive deliberations where diverse views can be raised and considered,” says Hugh Breakey.

“Naturally, no-one can or should expect immunity from social consequences for what they say in public discussion, Breakey adds. “The more that institutional sanctions are applied on the basis of positions taken in [controversial] debates the narrower the spectrum of positions that are likely to be defended, and the more that different views will fail to be represented.”

Kate Manne suggests a simple principle to test which voices we should accept as part of our political life: “It’s good to have a variety of voices, but those voices need not to silence or speak over the voices of other people,” she says.

“Abbott’s voice does not meet that simple test. “

Unlike Manne, Breakey doesn’t suggest Abbott’s views sit outside the realm of acceptable political opinions, he agrees with Manne’s principle. “If we want democracy to be more than the tyranny of the majority, or (worse still) rule by elites, then we need more civic tolerance afforded to those who think and speak in disagreeable ways.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is it fair to expect Australian banks to reimburse us if we’ve been scammed?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships