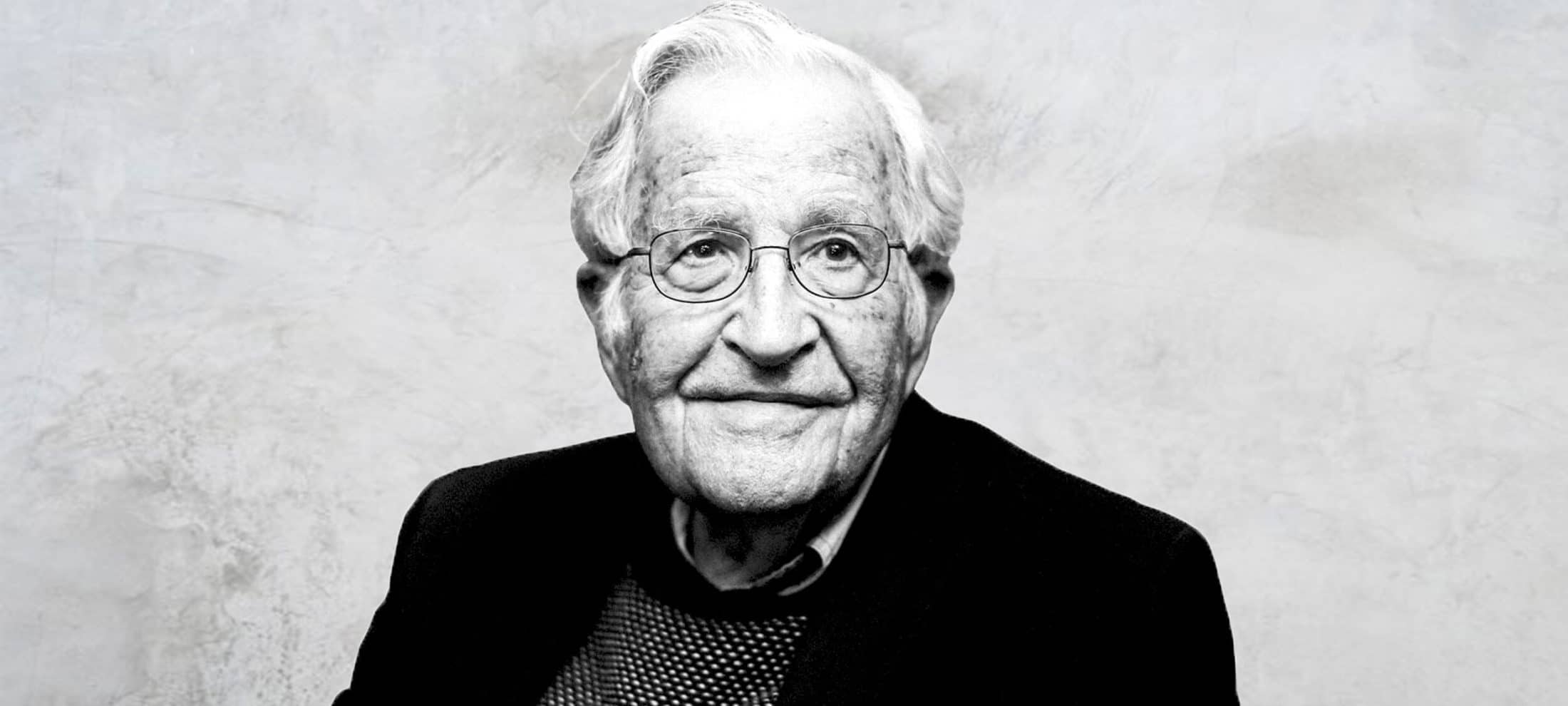

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 12 NOV 2018

Noam Chomsky (1928—present) is one of the foremost scholars and activists of our time.

With over a hundred books, thirty honorary degrees, and a generation of aspiring leftists behind him, Chomsky’s life puts a practical lens on the motto ‘protest is patriotic’.

The human tendency towards freedom

Chomsky earned a PhD in linguistics for his theory of “universal grammar”, a theory where all people are “born knowing” shared properties that underpin all human language. These properties, which create what he calls a “language acquisition device”, are what helps babies pick complex languages up instinctively.

According to Chomsky, while language’s laws and principles are fixed, the manner in which they are generated are free and infinitely varied. This view of human nature is one that runs through Chomsky’s attitudes to linguistics or politics: we must protect the innate human tendency towards freedom.

Pessimist of intellect

Chomsky’s opposition to war and totalitarianism started early. He wrote his first paper on the threat of fascism at ten. He opposed the Vietnam War while working at MIT, a military-funded university. He called Gaza the world’s “largest open-air prison” and said the US bears full responsibility for Israel’s war crimes.

Chomsky’s public denunciations of US foreign policy in Central America and East Timor, its interference in Middle Eastern elections and the shoot-first-ask-later’ type of diplomacy have drawn widespread ire and admiration. At the height of his fame in the 70s, it was discovered the CIA was keeping tabs on him and publicly lying about doing so.

Noam Chomsky’s consistent and vocal criticism of the US government comes from the belief that he, as a member of that country, holds a moral responsibility to stop it from committing crimes. That, and it’s far more effective than criticising a government that isn’t responsible for him.

“States are not moral agents; people are, and can impose moral standards on powerful institutions.”

Manufacturing consent

In what is arguably Chomsky’s most famous work, ‘Manufacturing Consent’, he outlined mainstream media’s complicity with government and business interests. He traced the capitalist formula of selling a product at a profit to the highest bidder in relation to the media. Here, people are the product and advertisers are bidding for our attention. Compare this with the monopoly social media has over our time and the ensuing competition for available ad space, and you’ll notice this line of argument growing in prescience.

Chomsky argued the advertising market is shaped by the external conditions of the state. It’s in their best interests to placate their ‘product’ and water down anything that would spur them to act against it. Any dissenting opinion is either ignored or presented as an anomaly. This is anti-democratic, said Chomsky, for a nation is only democratic insofar as government policy accurately reflects informed public opinion.

“If we don’t believe in free expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all.”

Speak truth to power

Fred Halliday, an Irish academic, has criticised Chomsky for overestimating the power and influence of the US. Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, Oxford historian Stephen Howe, and linguist Neil Smith, have called him a fierce and aggressive moral crusader, who dismisses critics as unqualified, mistaken, or even “charlatans“.

Today, Chomsky is outspoken on what he considers the two greatest threats to humanity: nuclear war and climate change. But with NEG scrapped, the Doomsday Clock inching to midnight, and Congress split, it looks unlikely that decisive action against either of these threats will be carried out anytime soon.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 11 NOV 2018

Eleanor Roosevelt (1884—1962) was an American diplomat and longest serving First Lady of the United States, best known for her work on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

She was affectionately dubbed “The First Lady of the World”. The thread running through her massive body of work is the single idea: fear threatens our lives and our democracies.

To live well means to live free from fear

Roosevelt lived in a world reeling from fascism. Though the Second World War had ended, the horrors of Nazism, the Holocaust and Stalinism revealed the depths people would succumb to out of fear and insecurity.

It wasn’t your garden variety type of fear she was concerned with. It was the type of widespread fear that debilitates courage, rewards conformity and stifles “the spirit of dissent”. By succumbing to this immobilising fear, Roosevelt said, we waste our lives.

“Not to arrive at a clear understanding of one’s own values is a tragic waste. You have missed the whole point of what life is for.”

Roosevelt wanted all people to know their values. As an influential public figure and patriotic American, she especially wanted this for her country.

This wasn’t without reason. The growing fear of political others (McCarthyism) and racial others (the push for segregation) mobilised Roosevelt and emboldened her stance. She didn’t want conformity to win.

“When you adopt the standards and the values of someone else or a community or a pressure group, you surrender your own integrity. You become, to the extent of your own surrender, less of a human being.”

Find a teacher in every person you meet

Roosevelt felt the danger of fear and conformity went beyond the trauma of war. It could quash “a spirit of adventure”, a way of viewing and experiencing everyday life that made you a better person.

She wasn’t talking about a thrill seeking, you-only-live-once, way of navigating the world. She meant close mindedness – denying your life experiences the opportunity to change your mind and mould your actions.

“Learning and living are really the same thing, aren’t they? There is no experience from which you can’t learn something. When you stop learning you stop living in any vital or meaningful sense. And the purpose of life is to live it, to taste experience to the utmost, to reach out eagerly and without fear for newer and richer experience.”

Roosevelt believed that everyone has something to teach you, and you are the ultimate beneficiary. Your character, your actions and your democratic polity.

And some might find being motivated by self-betterment alone to be selfish. After all, shouldn’t we do good simply because it is good? Isn’t it more noble to be motivated by what Kant called “good will”, or a moral duty?

Even if it’s possible that realizing motivation from a place of moral obligation is a higher ideal, Roosevelt was grounded in the everyday. She wasn’t concerned with principles the vast majority of a traumatised, distrustful nation would find out of reach, so she focused on the individual.

A principled life

The most remarkable thing about Roosevelt aren’t necessarily her ideals. It was her moral gumption to act on them even if they were unorthodox for the times or grossly unpopular.

She lobbied for greater intakes of World War II refugees when immigration was not supported by many Americans still reeling from the hardships of the Great Depression. She criticised her husband, President Franklin Roosevelt, for a policy intended to address the post-Depression housing market crash that segregated black and white citizens.

She broke with tradition by inviting African American guests to the White House. She spoke out against the internment of Japanese soldiers to the very population grieving the 2403 Americans they killed at Pearl Harbour (in comparison, it’s reported 55 Japanese lives were lost).

Roosevelt’s reputation for loving all has not gone unchallenged. She has been accused of taking sides in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a way that contravenes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights she worked on. While famous for wanting to protect displaced post WWII refugees, who were often Jewish, she felt the solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict was to resettle indigenous Palestinians in Iraq – the suggestion being she had a Zionist bias.

Roosevelt nevertheless maintains her name as a pioneer in humanitarian efforts who walked her talk. Fast forward to today’s polarised political spectrum, and her story reminds us the tools to make it through are there.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 26 SEP 2018

It’s no exaggeration to say the ideas of Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith (1723—1790) have shaped the world we live in.

By providing the core intellectual framework in defence of free markets, he positioned human liberty and dignity at the centre of trade and money – all for the common good.

Adam Smith, the pioneer

In the 18thcentury, the race to colonise as many resource rich places as possible meant powerful countries were often at war. Companies which added to the wealth of empires were protected by grateful governments, creating trade monopolies that seemed impossible to dismantle. This was the heyday of mercantilism.

Smith noticed how these actions created concentrations of wealth, benefiting the wealthy while the labour class struggled to survive. His first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, argued that the virtues of sympathy and reciprocity could tame greed.

His second, The Wealth of Nations, was about promoting a new way of approaching wealth that was as lucrative as it was just. The approach Smith adopted was multifaceted: economic, defensive, legal, and moral.

Smith argued that countries were competing for the wrong thing. Wealth wasn’t to be found in commodities like gold and silver. It resided in human labour and ingenuity. Smith encouraged countries that would normally look externally for wealth, suppressing the labour class and enslaving others, to look internally instead.

If the labour class could have the freedom to pick their job, all the while knowing the government would leave the money they made well alone, why wouldn’t they work hard at it? They would produce goods and services of even higher quality, and the government could buy these and trade them with each other. Everyone wins.

Collaboration would mean countries wouldn’t need to waste money on defence and war. They could save and accumulate capital, and invest that into better machinery, freeing people to work more productively. The labour class would grow richer, and so would the nation.

Smith stressed that in order for a free market to ensure fair pay for fair work, contracts had to be honoured, people had to keep their word, and governments mustn’t get into debt or take people’s property. Theft, negligence, mistakes, or irresponsible government spending must to be managed by the rule of law. And in the case of foreign powers, defence.

Thus, for Smith – a free market must rest on a sound ethical foundation. Given this, he argued for moral education of a kind that would lead people to be honourable and behave justly. This included the rich. Smith thought that an appeal to ‘enlightened’ self-interest might lead them to act honourably. By lavishing praise, accolades, and rewards on those who spend their wealth in charity, the rich gain the status and rank they really desire.

Adam Smith, the legacy

Claims of plagiarism, usury, inconsistency, racism, and all else aside, the major complaint directed towards Smith is his concept of the “invisible hand”. His observation that self-interested individuals end up benefiting the common good – that they are “led by an invisible hand to promote an end that was no part of his intention.” – has prompted some critics to label him naïve, idealistic, or even immoral.

The following quotation (misattributed to John Maynard Keynes) sums it up: “Capitalism is the astounding belief that the wickedest of men will do the wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone”. But that plays into the Smith = laissez-faire trap, and ignores the safeguards he proposed against human corruption.

Smith did not think greed was good, saying this removed “the distinction between vice and virtue”, nor did he believe business interests and the public interest necessarily coincide. Instead, his perspective was that market competition forced people to act in ways that benefited others, regardless of their intention. And when it failed to do that, an overarching authority should step in. For Smith, markets have no intrinsic value – they are merely tools for the betterment of life for all.

No doubt the world we live in now is vastly different to pre-Industrial Scotland. Mass media, the Internet, the textile industry, factory farms, surveillance, housing prices, offshore tax havens…much would have seemed strange and unfamiliar to Smith. But his work and legacy leave a lesson in economics, ethics, and politics – all the more prescient in a world where the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Farhad Jabar was a child – his death was an awful necessity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Israel or Palestine: Do you have to pick a side?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Gordon Young 21 SEP 2018

If the last decade of Australian politics has taught us anything it is this: democracy is a deeply flawed system.

Between the leadership spills, minority governments, ministerial scandals, legal corruption, and campaign donations, democracy is leaving more of us disillusioned and distrustful.

And that’s just in Australia.

Overseas, various ‘democratic’ governments have handed us Brexit, Russian election tampering (both domestically and abroad), the near collapse of the Euro, the Chinese Government’s Social Credit scheme, and the potentially soon-to-be-impeached Trump Presidency.

It’s not surprising that many are looking for an alternative system to run the country. Something simpler, more direct. Something efficient and easy.

Something like capitalism.

This may seem absurd on first reading – after all, how can an economic system replace the political governance of an entire nation? But capitalism is more than how we trade goods and services. It spills into a broader socio-economic theory that claims it can better represent people nationally and abroad than democracy ever could. This is known as neoliberalism.

Neoliberals argue that we don’t need to rely on the promises of unaccountable representatives to run the government. We can let competition decide. Just as a free market encourages better products, why don’t we let the free market encourage better governance?

If Bob does a better job fixing your car than Frank, employ Bob and vote for that quality as the standard. Frank either picks up his game or goes out of business. If your neighbouring electorate’s MP does a better job representing you, pay him and vote for his policy. If people value businesses that treat their employees well, those businesses will succeed and others will change their practices to compete.

Where democracy asks you to trust in the honour of your leaders, and only gives you a chance to hold them to account every few years, neoliberalism lets you exercise your choice every single time you spend your money, every single day.

This is far from fantasy thinking. It is this essential idea that drives ideas like ‘small government’, privatisation of state infrastructure, decreasing business taxes, and cutting ‘red tape’ – remove government interference from the system and leave the decisions up to the people themselves.

On paper it is the perfect system of government – a direct democracy where every citizen constantly drives policy based on what they buy and why.

Great, right? Well, only if you’re a fan of feudalism. Because that is what such a system would inevitably produce.

Consider this: within democracy, who is in control? The elected government obviously has the reigns of power during their term (to a frankly frightening degree), but how do they maintain that power?

By being elected, of course. Whether they like it or not, every three to four years they at least have to pretend they care about the needs of the people. In reality it’s hardly as simple as ‘one person, one vote’ – between campaign donations, lobby groups, ‘cash for access’, and good old-fashioned connections, some citizens will always have more power than others – but the fact remains that within democracy, the people in power still need to care about the whims of their citizens.

Now consider this: within this ideal capitalist, neoliberal, vote-with-your-dollar system, who is in control? If you express your interests in this system through your purchases, then power is dispersed based on how much you spend, right?

Who does the most spending? The people with the most money.

Here is the critical question and the sting in tail of the neoliberalism: why should the people in control of such a society, where power is determined by wealth alone, give the slightest damn about you?

Whether sincere or not, democracy requires the decision makers to court all citizens at least every election (and a lot more frequently than that, if they know what’s good for them). But in a purely capitalist society, why would the power-players ever need to consult those without significant wealth, power, or influence?

Even in a democratic world a mere 62 people already own more money than half of the entire world’s population, and exert titanic power upon the world’s markets that no normal citizen can ever hope to challenge.

Remove the political franchise that democracy guarantees every citizen by default, and you remove any and all controls of how those ultra-rich exert the power this wealth grants them.

So while we may criticise democracy for its inefficiencies, and fantasise how much better it would all be if government ‘were run like a business’, such idle complaints miss the key value of democracy – that in granting each and every citizen the inalienable right to an equal vote, none of them can safely be ignored by those who would aspire to power.

Perhaps you believe that the neoliberal utopia would be a better system, and the 1 percent would never decide to relegate the masses back to serfdom. But the fact that such a decision would now depend entirely on their whims, should be enough to terrify any sane citizen.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why Australian billionaires must think “less about the size of their yard” and more about philanthropy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ready or not – the future is coming

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just War Theory

BY Gordon Young

Gordon Young is a lecturer on professional ethics at RMIT University and principal at Ethilogical Consulting.

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 23 AUG 2018

As the Commonwealth Government ponders its response to the Ruddock Religious Freedom Review, it’s worth considering what people of faith may be seeking to preserve and what limits society might justifiably seek to impose.

The term ‘religious freedom’ encompasses a number of distinct but related ideas. At the core, it’s freedom of belief – in a god, gods or a higher realm or being.

Many religions make absolute (and often mutually exclusive) claims to truth, most of which cannot be proven. Religions rely, instead, on acts of faith. Next comes freedom of worship – the freedom to perform, unhindered, the rituals of one’s faith. Then there is the freedom to act in good conscience – to give effect to one’s religious belief in the course of one’s daily life and, as a corollary, not to be forced to act in a manner that would violate one’s sacred obligations. Finally, there is the freedom to proselytise – to teach the tenets of one’s religion to the faithful and to those who might be persuaded.

In a secular, liberal democracy the four types of religious freedom outlined above – to believe, to worship, to act and to proselytise – attract different degrees of liberty. For example, people are generally free to believe whatever takes their fancy, no matter how ill-founded or bizarre. This is not so in all societies. Some theocracies will punish ‘heretics’ for holding unorthodox beliefs. Acting out of belief – in worship, deeds and proselytising – is often subject to some measure of restraint. For example, pious folk are not permitted to set up a pulpit (or equivalent) in the middle of a main road. They are not permitted to beat a woman, even if the teaching of their religion allows (or requires) her chastisement. They are not permitted to let a child die because of a religious objection to life-saving medical procedures. Nor are they able to teach that some people are ‘lesser beings’, lacking intrinsic dignity, simply because of their gender, sexuality, culture, religion, and so on. In other words, there are boundaries set for the expression of religious belief, whatever those beliefs might be.

It is precisely the setting of such ‘boundaries’ that has become a point of contention. Some Australian religious leaders claim they should be exempt from the application of Australian laws that they do not approve, like anti-discrimination legislation. This is nothing new. As it happens, in Australia, a number of religions have long denied the validity of secular law, even to the extent of running parallel legal systems.

The Roman Catholic Church regularly applies Canon Law in cases involving the status of divorcees, the sanctity of the confessional, and so on. The Government of Australia might recognise divorce, but the Church does not. The following text is taken from the official website of the Archdiocese of Sydney: A divorce is a civil act that claims to dissolve a valid marriage. From a civil legal perspective, a marriage existed and was then dissolved. The Catholic Church … does not recognise the ability of the State to dissolve a marriage. An annulment, on the other hand, is an official declaration by a Church Tribunal that what appeared to be a valid marriage was actually not one (i.e, that the marriage was in fact invalid) [my emphasis].

In a similar vein, the Jewish community maintains a separate legal system that oversees the application of Halakhic Law through the operation of special Jewish religious courts called Beth Din. Given the precedents set by Christians and Jews, it’s not surprising that adherents of other faith groups, notably Muslims, are seeking the same rights to apply religious laws within their own courts and to enjoy exemptions from the application of the secular law.

“Fundamental human rights come as a ‘bundle’. They are indivisible.”

Given all of the above, are there any principles that we might draw on when setting the boundaries to religious freedom?

Human rights

Fortunately, the proponents of freedom of religion have provided an excellent starting point for answering this question. It begins with the core of their argument – that freedom of belief (religion) is a fundamental human right. Their claim is well founded. However, those who invoke fundamental human rights cannot ‘cherry pick’ amongst those rights, only defending those that suit their preferences.

Fundamental human rights come as a ‘bundle’. They are indivisible. It follows from this that if people of faith are to assert their claim to religious freedom as a fundamental human right, then the exercise of that freedom should be consistent with the realisation of all other fundamental human rights. Religious freedom is but one. It follows from this that any legislative instrument designed to create a legal right to freedom of religion must circumscribe that right to the extent necessary to ensure that other human rights are not curtailed. For example, a legal right to religious freedom should not authorise violence against another person. Nor should it permit discrimination of a kind that would otherwise be considered unlawful under human rights legislation.

If there is to be Commonwealth legislation, then it should establish an unrestricted right of belief and a rebuttable presumption in favour of acting on those beliefs. The limits to action should be that the conduct (either by word or deed): does not constrain the liberty of another person, does not subject another person to any form of violence, does not deny the intrinsic dignity of another person and does not violate the human rights of another person. Finally, it is essential that as a liberal democracy any Australian legislation specify that the tenets of a religion only apply to those who have freely consented to adopt that religion.

So, what might this look like in practice – say, in relation to same sex marriage now that it is lawful?

Baking cakes

Nobody should be compelled to believe that same sex marriage is ‘moral’. That is a matter of personal belief unrelated to the law. Second, it should be permissible to teach, to members of one’s faith group, and to advocate, more generally, that same sex marriage is immoral (a view I do not hold). The fact that something is legal leaves open the question of its morality. Third, no person should be required to perform a marriage if to do so would violate the dictates of their conscience. Roman Catholic priests refuse to marry heterosexual divorcees. Such marriages are allowed by the state – yet no priest is forced to perform such a marriage because to do so would make them directly complicit is an act their religion forbids. Such an allowance should only extend to those at risk of becoming directly complicit in objectionable acts. For example, such an allowance should not be granted to a religious baker not wanting to provide a wedding cake to a gay couple. Cakes play no direct role in the formalities of a civil marriage. So, unlike a pharmaceutical company that might justifiably object to becoming complicit through the supply of drugs to an executioner, a baker is never going to be complicit in the performance of a marriage. As such, a baker should be bound by law to supply his or her goods on a non-discriminatory basis. Of course, there will always be some who feel obliged to put the requirements of their religion before the law.

To act according to one’s conscience in an honourable choice. But only do this if you are willing to bear the penalty.

Dr Simon Longstaff is Executive Director of The Ethics Centre: www.ethics.org.au

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre Kym Middleton Aisyah Shah Idil 20 AUG 2018

Feminist firebrand or second wave scourge? When The Female Eunuch was published to international success, it was obvious Germaine Greer (1939—present) had hit a nerve – something she continues to do.

This article contains language and content that may be offensive to some readers.

Germaine Greer is an Australian writer and public intellectual who rose to international influence with her book published in 1970, The Female Eunuch. It was a watershed text in second wave feminism, a bestseller around the world, and it made Greer a household name.

Greer’s infamously bold voice and sense of humour permeates throughout the book. Her strong character and take no prisoners approach to public debate saw her regularly contribute to panels and broadcast media. Greer was launched into the public eye as a young, bolshie feminist star.

Since then, Greer has written many books spanning literature, feminism and the environment. She has become one of Australia’s most ‘no-platformed’ thinkers. Almost five decades on, we take a look at her contributions to feminist philosophy.

Human freedom is intrinsically tied to sexual freedom

Greer is a liberation, rather than equality feminist. She believed achieving true freedom for women meant asserting their uniquely female difference and “insisting on it as a condition of self-definition and self-determination”.

Greer wanted to be certain about this female difference, and for her, this certainty started with the body.

You can think of Greer’s claims like this:

- Women are sexually repressed.

- Men are not sexually repressed.

- The difference between men and women is their biological sex.

- Biological sex determines if you’re sexually repressed or not.

The second part of her argument is as follows:

- Women are expected to be ‘feminine’.

- Women are sexually repressed.

- The expectation to be ‘feminine’ is sexually repressive.

Greer is scathing in her portrayal of ‘femininity’. She claimed it kept women docile, repressed, and weak. It stifled women’s sexual agency, hence the ‘eunuch’, which was intrinsically tied to their humanity.

Only by liberating women sexually could they remove this imposed submissiveness and embrace the freedom to live the way they wanted.

“The freedom I pleaded for twenty years ago was freedom to be a person, with dignity, integrity, nobility, passion, pride that constitute personhood. Freedom to run, shout, talk loudly and sit with your knees apart.” – Germaine Greer (1993)

A feminist utopia is an anarchist utopia first

In the London Review of Books 1999, Linda Colley wrote, “Properly and historically understood, Greer is not primarily a feminist. More than anything else, she should be viewed as a utopian.”

For Greer, the greatest danger of the widespread female eunuch is not an unfulfilling sex life. It is in her being so concerned with femininity that she is incapable of political action. Greer believed this social conditioning was dire and its enforcers so embedded that revolution rather than reform was required.

Greer called for this revolution to start in the home. She spoke openly about topics that at the time were taboo: menstruation, hormonal changes, pregnancy, menopause, sexual arousal and orgasm. She decried the agents of femininity that she felt kept women trapped: makeup, constricting clothing, feminine hygiene products, stifling marriages, misogynistic literature and female sexual competitiveness. She reserved her greatest fury for widespread consumerism, which she believed kept women dependent on the systems that forged their own oppression.

Like Mary Wollstonecraft before her, Greer argued neither men nor women benefited from this. She called upon women to rebel again these “dogmatists” and create a world of their own. But the solution she presents is exploratory instead of pragmatic. Perhaps women could live and raise their children together, making their own goods and growing their own food. It would be somewhere pleasant like the rolling landscapes of Italy, with local people to tend house and garden. (It’s unclear whether these local people would be liberated too.)

Intellectual criticisms

Greer’s celebration of non-monogamous sex in The Female Eunuch and her derision of Western society’s obsession with sex in Sex and Destiny led critics to label her ideas slipshod and too inconsistent for a public intellectual.

The root of most criticisms and controversies surrounding Greer, tend to stem from her view of the sexes. Like other second wave feminists, she suggested biological sex determined women’s oppression. This stands in stark contrast to the perspectives of third wave feminists and queer theorists, such as Judith Butler, for whom gender’s learned behaviours play the crucial role.

Greer and her contemporaries are often criticised by third and fourth wave feminists for predicating their philosophies on a male/female binary. A binary that does not account for the broad chromosomal spectrums found among intersex people or the many ways in which individuals feel and express their gender.

Infamous commentary

Greer is not the docile feminine woman she warned of in The Female Eunuch. She has long been celebrated for bucking trends and being refreshingly bold and frank. She is also heavily criticised for being rude, offensive and out of touch. She has been described as having “the self-awareness of a sweet potato”, a “misogynist”, and “a clever fool”.

After she extolled the work of Australia’s first female Prime Minister Julia Gillard on an episode of ABC’s Q&A, she was slammed for criticising Gillard’s body and clothing:

“What I want her to do is get rid of those bloody jackets … They don’t fit. Every time she turns around you’ve got that strange horizontal crease which means they cut too narrow in the hips. You’ve got a big arse Julia…”

Social media lit up with calls for Greer to “shut up” after she linked rape and bad sex in the age of #MeToo:

“Instead of thinking of rape as a spectacularly violent crime – and some rapes are – think about it as non-consensual, that is, bad sex. Sex where there is no communication, no tenderness, no mention of love. We used to talk about lovemaking.”

It is probably Greer’s public statements around transgender women that have attracted the most protest. In an interview after an intense no-platforming campaign to cancel a lecture Greer was scheduled to give at Cardiff University on women and power in the 20th century, she said, “Just because you lop off your penis and then wear a dress doesn’t make you a fucking woman”.

This sentiment probably links with Greer’s ideas on sexed bodies. A sympathetic reading of the comment might see it as one about being born into oppression – a rather second wave feminist sentiment that echoes the racial and queer politics of the same era. An idea that’s sometimes cited as analogous to Greer’s controversial comment is that you cannot understand what it is to be black, unless you were born black and experienced discriminations since the day of your birth. Perhaps she was suggesting we cannot understand the oppression experienced by women and girls unless we are born into a female body. Perhaps not. Either way, the comment was received as incredibly offensive and naive to transgender women’s experiences.

“People are hurtful to me all the time. Try being an old woman. I mean for goodness sake! People get hurt all the time. I’m not about to walk on eggshells.” – Germaine Greer, 2015

Greer and second wave feminists generally are at odds with intersectional feminism which is prominent today. Intersectional feminism holds that many factors beyond sex marginalise people – age, race, nationality, disability, class, faith, sexual orientation, gender identity… Different women will be oppressed to varying degrees.

Whether Greer is a trailblazer or tactless provocateur, it is doubtless her ideas have influenced the political and personal and landscapes of gender relations and feminist thinking.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How far should you go for what you believe in?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 2 AUG 2018

This article was written for, and first published on the Australian Financial Review.

This much we know: a blistering series of scandals has led to a profound loss of trust – not just in Australia but across the developed world. Consequently, the issue of trust has become a hot topic – a new staple item on meeting agendas of cabinets, boards, conferences, etc.

However, what if the spotlight being shone on the topic of trust is blinding us so that we fail to see a far greater risk lurking in the shadows – the potential loss of legitimacy?

Creating Transparency

The Ethics Centre has just published a paper that raises this possibility and sounds a warning that should be heeded by those of us who believe in the virtues of the market economy. We do not argue that trust is unimportant. Instead, we make the case that while individuals and institutions can (and do) survive a loss of trust, they rarely (if ever) survive a loss of legitimacy.

“We do not argue that trust is unimportant. Instead, we make the case that while individuals and institutions can (and do) survive a loss of trust, they rarely (if ever) survive a loss of legitimacy.”

At the core of our argument is a simple truth of economics. A reduction in trust can be compensated for by an increase in the “deadweight” costs of surveillance and enforcement. The classic case is the making of agreements. A high trust context can see agreements made on the basis of a low-cost handshake (or its equivalent). Low trust contexts are burdened with the high costs of detailed contracts, enforcement provisions, litigation, etc.

The Definition

Bearing this in mind, we distinguish between the concepts of trust and legitimacy according to the following definitions:

Legitimacy is a recognised and well-founded right to claim a certain status, role or function.

Trust is a belief that a person or institution will perform their role or function in accordance with its obligations or where not bound by duty, in a predictable manner – often in accordance with its interests.

The less formal distinction is as follows: where low trust can be compensated for by a higher degree of checks and balances (deadweight costs), a loss of legitimacy cannot be compensated for at any cost.

Making The Case

Now, if you accept our argument that there is a difference between trust and legitimacy and that a loss of the latter is usually fatal, it soon becomes clear that some of our institutions are at grave risk. We see the early signs in a number of areas. In politics, it is not only political parties and politicians that risk losing legitimacy – it is the system of representative liberal democracy that is being called into question.

As the Lowy Institute has reported, a growing number of younger Australians doubt the capacity of democracy to respond to the challenges of modern life. In economics, there is growing scepticism about the legitimacy of an international economic order. Especially when the focus shifts to free trade and the operation of free markets. We see both trends converging in movements (sometimes dismissed and derided as mere populism) that are reshaping the political and economic landscapes in Europe, North America, Central America and at home.

The great risk in this is that each and every part of the political and economic ecosystem becomes tarred by the same brush – with the spiral of decline sucking in all…the good, the bad and the indifferent…without distinction.

Our Role

For its part, The Ethics Centre has a long history of calling attention to the ethical underpinnings of the free market…recalling that Adam Smith championed markets as the means by which to bring prosperity to all (and not just a few). We (again) make the case for free markets in this latest paper – but go one step further by outlining some core principles that we think should be adopted by corporations if they are to help maintain the legitimacy of the system upon which they ultimately depend.

At one level, the headline principles are deceptively simple: respect people, do no harm, be responsible and be transparent and honest. However, rather than simply state self-evident pieties, we have tied these principles back to the underlying concept of free markets as tools for increasing the stock of common good. These tools and mechanisms can only function, as intended, if participants do not lie, cheat or use their power oppressively.

“Businesses are struggling to develop enabling connections with communities. Their efforts are embedded in conversations about trust, social licence, shared value and so on.”

Businesses are struggling to develop enabling connections with communities. Their efforts are embedded in conversations about trust, social licence, shared value and so on. There are major programs to increase transparency – often as an alternative to trust (which makes transparency unnecessary). We argue that the problem with all of these efforts is that they fail to address the larger problem of a system whose parts are progressively undermining the legitimacy of the whole.

The good news is that the unravelling is reversible and that some fairly straightforward measures can be applied, but only if we rediscover the purpose of the free market and the economic actors that it sustains – for the good of all.

Visit https://ethics.org.au/trust-and-legitimacy/ to download a copy of the Trust, Legitimacy and the Ethical Foundations of the Market Economy report.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: René Descartes

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Online grief and the digital dead

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Calling out for justice

Calling out for justice

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Oscar Schwartz The Ethics Centre 19 JUL 2018

It’s probably the biggest phenomenon of calling out we’ve ever seen. On 15 October last year, in the wake of Harvey Weinstein being accused of sexual harassment and rape, actress Alyssa Milano tweeted:

“If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me too.’ as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.”

The phrase and hashtag ‘Me too’ powerfully resonated with women across the globe and became one of the most viral occurrences in social media history. Not only did the campaign become a vehicle for women to share their stories of sexual abuse and harassment, it had real world consequences, leading to the firing and public humiliation of many prominent men.

One of the fall outs of the #MeToo movement has been a debate about “call out culture”, a phrase that refers to the practice of condemning sexist, racist, or otherwise problematic behaviour, particularly online.

While calling out has been praised by some as a mechanism to achieve social justice when traditional institutions fail to deliver it, others have criticised call outs as a form of digital mob rule, often meting out disproportionate and unregulated punishment.

Institutional justice or social justice

The debate around call out culture raises a question that goes to the core of how we think justice should be achieved. Is pursuing justice the role of institutions or is it the responsibility of individuals?

The notion that justice should be administered through institutions of power, particularly legal institutions, is an ancient one. In the Institutes of Justinian, a codification of Roman Law from the sixth century AD, justice was defined as the impartial and consistent application of the rule of law by the judiciary.

A modern articulation of institutional justice comes from John Rawls, who in his 1971 treatise, A Theory of Justice, argues that for justice to be achieved within a large group of people like a nation state, there has to be well founded political, legal and economic institutions, and a collective agreement to cooperate within the limitations of those institutions.

Slightly diverging from this conception of institutional justice is the concept of social justice, which upholds equality – or the equitable distribution of power and privilege to all people – as a necessary pre-condition.

Institutional and social justice come into conflict when institutions do not uphold the ideal of equality. For instance, under the Institutes of Justinian, legal recourse was only available to male citizens of Rome, leaving out women, children, and slaves. Proponents of social justice would hold that these edicts, although bolstered by strong institutions, were inherently unjust, built on a platform of inequality.

Although, as Rawls argues, in an ideal society institutions of justice help ensure equality among its members, in reality social justice often comes into conflict with institutional power. This means that social justice has to sometimes be pursued by individuals outside of, or even directly in opposition to, institutions like the criminal justice system.

For this reason, social justice causes have often been associated with activism. Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s march in Montgomery, Alabama to protest unfair treatment of African American people in the courts was an example of a group of individuals calling out an unjust system, demanding justice when institutional avenues had failed them.

Calling out

The tension between institutional and social justice has been highlighted in debates about “call out culture”.

For many, calling out offends the principles of institutional justice as it aims to achieve justice at a direct and individual level without systematic regulation and procedure. As such, some have compared calling out campaigns like #MeToo to a type of “mob justice”. Giles Coren, a columnist for The Times of London, argues the accusations of harassment should be handled only by the criminal justice system and that “Without any cross-examination of the stories, the man is finished. No trials or second chances.”

But others see calling out sexist and racist behaviour online as a powerful instrument of social justice activism, giving disempowered individuals the capacity to be heard when institutions of power are otherwise deaf to their complaints. As Olivia Goldhill wrote in relation to #MeToo for Quartz:

“Where inept courts and HR departments have failed, a new tactic has succeeded: women talking publicly about harassment on social media, fuelling the public condemnation that’s forced men from their jobs and destroyed their reputations.”

Hearing voices

In his 2009 book, The Idea of Justice, economist Amartya Sen argues a just society is judged not just by the institutions that formally exist within it, but by the “extent to which different voices from diverse sections of the people can actually be heard”.

Activist movements like #MeToo use calling out as a mechanism for wronged individuals to be heard. Writer Shaun Scott argues that beyond the #MeToo movement, calling out has become an avenue for minority groups to speak out against centuries of oppression, adding the backlash against “call out” culture is a mechanism to stop social change in its tracks. “Oppressed groups once lived with the destruction of keeping quiet”, he writes. “We’ve decided that the collateral damage of speaking up – and calling out – is more than worth it.”

While there may be instances of collateral damage, even people innocently accused, a more pressing problem to address is how and why institutions we are supposed to trust are deaf to many of the problems facing women and minority groups.

Dr Oscar Schwartz is an Australian writer and researcher based in New York with expertise in tech, philosophy, and literature. Follow him on Twitter: @scarschwartz

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Existentialism

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Steven Pinker

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

We’re being too hard on hypocrites and it’s causing us to lose out

BY Oscar Schwartz

Oscar Schwartz is a freelance writer and researcher based in New York. He is interested in how technology interacts with identity formation. Previously, he was a doctoral researcher at Monash University, where he earned a PhD for a thesis about the history of machines that write literature.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Confucius

Big Thinker: Confucius

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 21 MAY 2018

Confucius (551 BCE—479 BCE) was a scholar, teacher, and political adviser who used philosophy as a tool to answer what he considered to be the two most important questions in life… What is the right way to rule? And what is the right way to live?

While he never wrote down his teachings in a systematic treatise, bite sized snippets of his wisdom were recorded by his students in a book called the Analects.

Underpinning Confucian philosophy was a deeply held conviction that there is a virtuous way to behave in all situations and if this is adhered to society will be harmonious. Confucius established schools where he gave lectures about how to maintain political and personal virtue.

“It is virtuous manners which constitute the excellence of a neighborhood.”

His ideas set the agenda for political and moral philosophy in China for the next two millennia and are emerging once again as an influential school of thought.

Humble beginnings

Confucius was born in 551 BC in a north-eastern province of China. His father and mother died before he was 18, leaving him to fend for himself. While working as a shepherd and bookkeeper to survive, Confucius made time to rigorously study classic texts of ancient Chinese literature and philosophy.

At the age of 30, Confucius began teaching some of the foundational concepts he formulated through his studies. He developed a loyal following and quickly rose up the political ranks, eventually becoming the Prime Minister of his province.

But at the age of 55 he was exiled after offending a higher ranking official. This gave Confucius an opportunity to travel extensively around China, advising government officials and spreading his teachings.

He was eventually invited back to his home province and was allowed to re-establish his school, which grew to a size of 3000 students by the time he died at age 72.

The golden age

Underpinning much of Confucius’ thought was a belief that Chinese society had forgotten the wisdom of the past and that it was his duty to reawaken the people, particularly the young, to these ancient teachings.

Confucius idealised the historical Western Zhou Dynasty, a time, he claimed, when living standards were high, people lived and worked in peace and contentment, the leaders carried out their duties in accordance with their rank, and the social order was stable and harmonious.

Confucius devoted his life to teaching the wisdom of this ancient society to his contemporaries in the hope of reinventing it in the present. For this reason, he didn’t claim to be an original thinker, but a receptacle of past wisdom. “I transmit but do not innovate”, he said.

Dao, de, and ren

While Confucius never wrote a systematic philosophical treatise, there are three intertwined concepts that run through his philosophy: Dao, De, and Ren.

Dao: Confucius interpreted Dao to mean a Way of living, or more specifically the right Way of living. This was not a concept he made up. It was already a central part of Chinese belief systems about the natural order of the universe. Dao is a slippery but profound concept suggesting there is a singular Way to live that can be intuited from the universe, and that all of life should be directed towards living this Way. If the Way is followed, the individual and society will be in perfect harmony.

De: Confucius saw De as a type of virtue that lay latent in all humans but that had to be cultivated. It was the cultivation of this virtue, Confucius believed, that allowed a person to follow the Way. It was in family life that people learned how to cultivate and practice virtuous behaviours. In fact, many of the main Confucian virtues were derived from familial relationships. For example, the relationship between father and son defined the virtue of piety and the relationship between older and younger siblings defined the virtue of respect. For this reason, Confucian ethics did not leave much room for an individual to exist outside of a family structure. Knowing where you stood in your family and your society was key to living a virtuous life.

Ren: While most Confucian virtues were cultivated within a strict social and family structure, ren was a virtue that existed outside this dynamic. It can be translated loosely as benevolence, goodness, or human-heartedness.

Confucius taught that the ren person is one who has so completely mastered the Way that it becomes second nature to them. In this sense ren is not so much about individual actions but what type of person you are. If you perform your familial duties but do not do so with benevolence, then you are not virtuous. Ren was how something was done, rather than the act itself.

Contemporary influence and relevance

Confucius’ influence on Chinese society during his life and in the two millennia since has been enormous. His sound bite like philosophies became China’s handbook on politics and its code of personal morality.

“He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it.”

It wasn’t until Mao’s Cultural Revolution that some of the basic tenets of Confucian ethics were publicly denounced for the first time. Mao was future oriented and utopian in his politics, and so Confucius’ idea of governance and ethics based in the ancient classics was considered dangerous and subversive. In fact, Mao’s Red Guards referred to the old sage as “The Number One Hooligan Old Kong”.

But in the past decade, the Communist Party has realised Confucius’ teachings might be useful again. The surge of wealth that has accompanied free market capitalism in China has meant that many of Mao’s ideologies no longer make sense for the government. This has prompted a resurgence of State led interest in Confucius as an alternative ideological underpinning for the current government.

While this is seen by many as a way for China to build a political future based on its philosophical past, others feel that the Communist Party has emphasised Confucian ideas about hierarchical social structure and obedience, while sidelining notions of virtue and benevolence.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Big Brother is coming to a school near you

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 21 MAY 2018

The idea of a UBI isn’t new. In fact, it has deep historical roots.

In Thomas More’s Utopia, published in 1516, he writes that instead of punishing a poor person who steals bread, “it would be far more to the point to provide everyone with some means of livelihood, so that nobody’s under the frightful necessity of becoming, first a thief, and then a corpse”.

Over three hundred years later, John Stuart Mill also supported the concept in Principles of Political Economy, arguing that “a certain minimum [income] assigned for subsistence of every member of the community, whether capable of labour or not” would give the poor an opportunity to lift themselves out of poverty.

In the 20th century, the UBI gained support from a diverse array of thinkers for very different reasons. Martin Luther King, for instance, saw a guaranteed payment as a way to uphold human rights in the face of poverty, while Milton Friedman understood it as a viable economic alternative to state welfare.

Would a UBI encourage laziness?

Yet, there has always been strong opposition to implementing basic income schemes. The most common argument is that receiving money for nothing undermines work ethic and encourages laziness. There are also concerns that many will use their basic income to support drug and alcohol addiction.

However, the only successfully implemented basic income scheme has shown these fears might be unfounded. In the 1980s, Alaska implemented a guaranteed income for long term residents as a way to efficiently distribute dividends from a commodity boom. A recent study of the scheme found full-time employment has not changed at all since it was introduced and the number of Alaskans working part-time has increased.

The success of this scheme has inspired other pilot projects in Kenya, Scotland, Uganda, the Netherlands, and the United States.

The rise of the robots

The growing fear that robots are going to take most of our jobs over the next few decades has added an extra urgency to the conversation around UBI. A number of leading technologists, including Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Bill Gates, have suggested some form of basic income might be necessary to alleviate the effects of unemployment caused by automation.

In his bestselling book Rise of the Robots, Martin Ford argues that a basic income is the only way to stimulate the economy in an automated world. If we don’t distribute the abundant wealth generated by machines, he says, then there will be no one to buy the goods that are being manufactured, which will ultimately lead to a crisis in the capitalist economic model.

In their book Inventing the Future, Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams agree that full automation will bring about a crisis in capitalism but see this as a good thing. Instead of using UBI as a way to save this economic system, the unconditional payment can be seen as a step towards implementing a socialist method of wealth distribution.

The future of work

Srnicek and Williams also claim that UBI would not only be a political and economic transformation, but a revolution of the spirit. Guaranteed payment, they say, will give the majority of humans, for the first time in history, the capacity to choose what to do with their time, to think deeply about their values, and to experiment with how to live their lives.

Bertrand Russell made a similar argument in his famous treatise on work, In Praise of Idleness. He writes that in a world where no one is compelled to work all day for wages, all will be able to think deeply about what it is they want to do with their lives and then pursue it. For many, he says, this idea is scary because we have become dependent on paid jobs to give us a sense of value and purpose.

So, while many of the debates about UBI take place between economists, it is possible that the greatest obstacle to its implementation is existential.

A basic payment might provide us with the material conditions to live comfortably, but with this comes the confounding task of re-thinking what it is that gives our lives meaning.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Billionaires and the politics of envy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

MIT Media Lab: look at the money and morality behind the machine

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights