Big Thinker: John Rawls

Is there a way to really get our societies to be fair for everyone?

This was the question John Rawls (1921-2002), American political philosopher and author of A Theory of Justice, attempted to answer. His work centres on social justice, privilege, and the distribution of resources in a society.

Rawl’s cake

Imagine it’s your birthday. Your parents decide to throw a party for you and your friends. When it’s time to cut the cake, your mother tells you, “You can cut the cake in whatever way you want to but you can’t choose the slice that you’ll get to have”.

Maybe you’d like a bigger slice of that cake. But since you don’t want to risk getting a small slice, you decide to cut equal sizes for everyone. Now you and your friends are happily munching away, knowing the cake was distributed as fairly as possible.

Fairness demands ignorance

Rawls thought most people’s definition of justice reflected what was good for them instead of anything shared or universal. You might think justice means owning the resources you’ve inherited, or you might think justice is about redistributing them. Whether intentionally or not, we all define justice in a way that gets us a little higher on the ladder. (Big slice for you, small slice for everyone else.)

To get to the core of things, Rawls asks us to imagine a situation where society doesn’t exist yet and no one knows where they will end up in life. What kind of society would you join knowing you could be somehow disadvantaged? If you entered this new world with no parents from childhood, a physical disability, intellectual impairment, financial hardship, or no access to school, what would you want it to be like?

If we each play along with Rawl’s hypothetical, we are likely to imagine fairness in a particular way. Rawls thought we would only join a society where everyone, no matter what circumstances we were born in, has their needs met.

Inequality needs to benefit everybody

Rawls’ conception of justice was based on society’s equal distribution of resources according to two principles.

The first principle is the equality principle. This says everyone should have access to the broadest possible range of civil liberties. Here the only limitation on our freedoms is what is necessary to give other people the same level of freedom. For this system to be fair, you can only be as free as everyone else.

The second principle is the difference principle. Any inequalities in society are only justified under two conditions:

1. There must be equality of opportunity. If there are going to be inequalities – like some people earning more money than others – they should be available to everyone. For example, if access to education increases people’s earning capacity, everyone should have the same access to education so everyone has the same chance to grow their wealth.

2. If there are any social disadvantages, they need to benefit the least advantaged people most. Rawls thought we should only be permitted to grow our personal wealth if we used it to benefit the poor. He wanted to keep the socioeconomically disadvantaged within a reasonable distance of the financially elite by redistributing resources. This was what he saw to be the fairest possible system.

If we were to imagine what the difference principle might look like in practice, it could be policies permitting people to leave inheritance to their children if the state is allowed to tax and distribute it to the poor.

Rawls’ challenge for political philosophy is to question whether a merit based system is as fair as people think. Was it only your work that got you to where you are today or did luck also play a role? If it was the latter, what does that tell us about justice?

Be consistent

Rawls was dedicated to finding the most reasonable political system possible. He believed the first step was to fill our parliaments with reasonable people. It might sound like a no brainer, but by reasonable he meant those with consistency and coherence between their various opinions and beliefs. He called this “reflective equilibrium”.

Imagine someone believes if employees do the same work, they should receive the same wage. Imagine they also opposed striving for pay parity between men and women. Rawls would say this person’s political beliefs are incompatible and therefore unreasonable. To achieve reflective equilibrium, one of these views will have to shift.

In fact, Rawls thought achieving genuine reflective equilibrium was impossible. Instead, we should try to get as near as we can to perfect synergy.

For those of us interested in ethics and politics, the reflective equilibrium is an important idea. We often form opinions based on gut reaction, instinct, or by focussing on the specifics of a situation.

Each of these approaches can at times be unreasonable and inconsistent. By forcing us to test how our different beliefs fit together, Rawls encourages us to do something very basic but very important: make sure our set of beliefs make sense.

First published March 2017. Updated August 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Time for Morrison’s ‘quiet Australians’ to roar

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s ethical obligations in Afghanistan

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

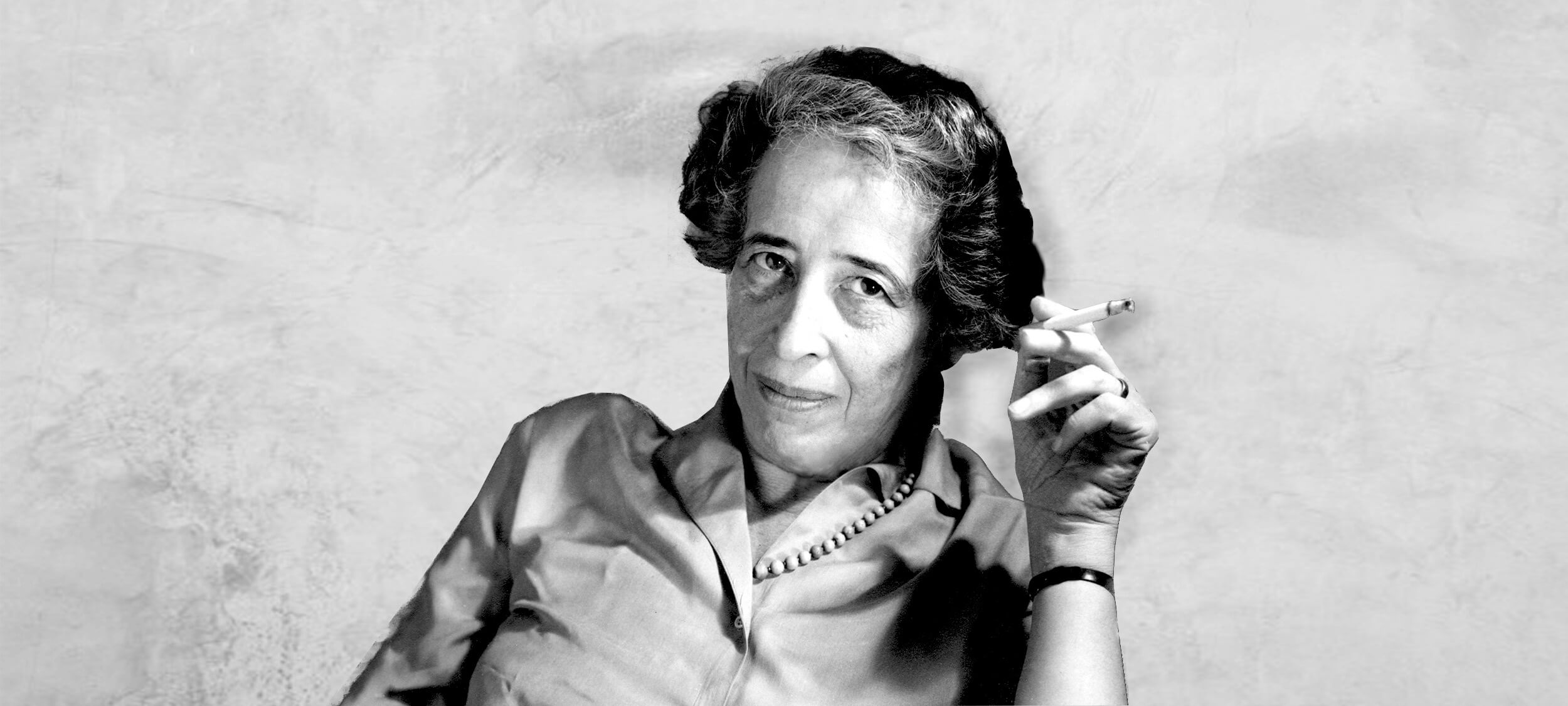

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Johannah “Hannah” Arendt (1906 – 1975) was a German Jewish political philosopher who left life under the Nazi regime for nearby European countries before settling in the United States. Informed by the two world wars she lived through, her reflections on totalitarianism, evil, and labour have been influential for decades.

We are still learning from this seminal political theorist. Her book The Origins of Totalitarianism sold out on Amazon in 2017, more than 60 years after it was first published.

Evil doesn’t need malicious intentions

Arendt’s most well known idea is “the banality of evil”. She explored this in 1963 in a piece for The New Yorker that covered the trial of a Nazi bureaucrat who shared the first name of Hitler, Adolf Eichmann. This later became a book called Eichmann in Jerusalem: Reflections on the Banality of Evil.

In Eichmann, Arendt found a man whose greatest crime was a lack of thinking. His role was to transport Jewish people from German occupied areas to concentration camps in Poland. Eichmann did not kill anyone first hand. He was not involved in designing Hitler’s final solution. But he oversaw the trains that took millions of people to their deaths. They were gassed in chambers or died along the way or in camps due to starvation, overwork, illness, cold, heat, or brutality. Eichmann’s only defence for his involvement in this atrocity was obedience to the law and fulfilling his duty.

Eichmann was so steadfast with this line of reasoning he even referenced the philosopher Immanuel Kant and his theory of moral duty. Kant argued morality was acting on your obligations, not your emotions or what will bring you benefit. For Kant, the person who helps the beggar out of empathy or a belief assisting is a pathway to heaven is not doing an act of good. Kant felt everyone is morally obliged to help the beggar, and they are especially virtuous if they act on this duty despite feeling repulsed or no rewarding sense of doing good.

This does not really suit Eichmann’s argument because Kant was emphasising our ability to reason above emotion. This is precisely where Eichmann failed. We can only guess but it seems likely he did his job without asking questions while feeling a sense of comfort in the safety of his salary and senior position during volatile times.

Arendt believed it was this lack of true thinking and questioning that paved the way to genocide. Evil on the scale of Nazism required far more Adolf Eichmanns than Adolf Hitlers.

Totalitarianism needs political apathy

In studying the causes of WWII, Arendt came across “the masses”. She believed totalitarian regimes needed this to succeed.

By “the masses”, she meant the enormous group of people who are politically disconnected from other members of society. They don’t identify with a particular class, religion, or group. Their lack of group membership deprives them of common interests to demand from government. These people have no interest in politics because they don’t have political clout. They are an unorganised cohort with different, often conflicting desires whose needs are easily disregarded by politicians.

But although these people take no active interest in politics they still hold expectations for the state. If politicians fail those expectations they face “the loss of the silent consent and support of the unorganised masses”. In response, they “shed their apathy” and look for an outlet “to voice their new violent opposition”.

The totalitarian leader emerges from this “structureless mass of furious individuals”. With the political apathy of the masses turned to hostility, leaders will rise by breaking established norms and ignoring the way politics is usually done. Arendt dramatically says they prefer “methods which end in death rather than persuasion”. In short, they’re less likely to build politics up than they are to tear it down because that’s what the masses want.

If this all sounds depressing, there is a solution embedded in Arendt’s writing: political engagement. The masses arise when individuals are lonely and politically disconnected. They are defined by a lack of solidarity or responsibility with other citizens.

By revitalising our political community we can recreate what Arendt sees as good politics. This is when people feel a sense of personal and political responsibility for the nation and are able to band together with other citizens who have common interests. When citizens are connected in solidarity with one another, the mass never occurs and totalitarianism is held at bay.

When work defines you, unemployment is a curse

Not all Arendt’s work was concerned with war and totalitarianism. In The Human Condition, she also offers a general critique of modernity. Drawing on Karl Marx, Arendt thought the industrial age transformed humanity from thinkers into “working animals”.

She thought most people had come to define themselves by their work – reducing themselves to economic robots. Although it’s not a central point of Arendt’s analysis, this reduction is a product of the same forces she sees in the banality of evil. It’s a triumph of ‘doing’ over ‘thinking’ and of humans finding easy ways to define themselves.

Arendt wasn’t just concerned because people were reducing themselves to working drones. She also worried the industrial age which had just redefined them was also about to rob them of their new identities. She believed within a few decades, technology would replace factory jobs. Many people’s work would vanish.

“What we are confronted with is the prospect of a society of labourers without labour, that is, without the only activity left to them. Surely, nothing could be worse.”

In a time when automation now threatens over half of jobs on average in OECD countries, Arendt’s predictions seem timely. Can we shift our identity away from work in time to survive the massive job reduction to come?

Published February 2017. Updated August 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Dirty Hands

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How we should treat refugees

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

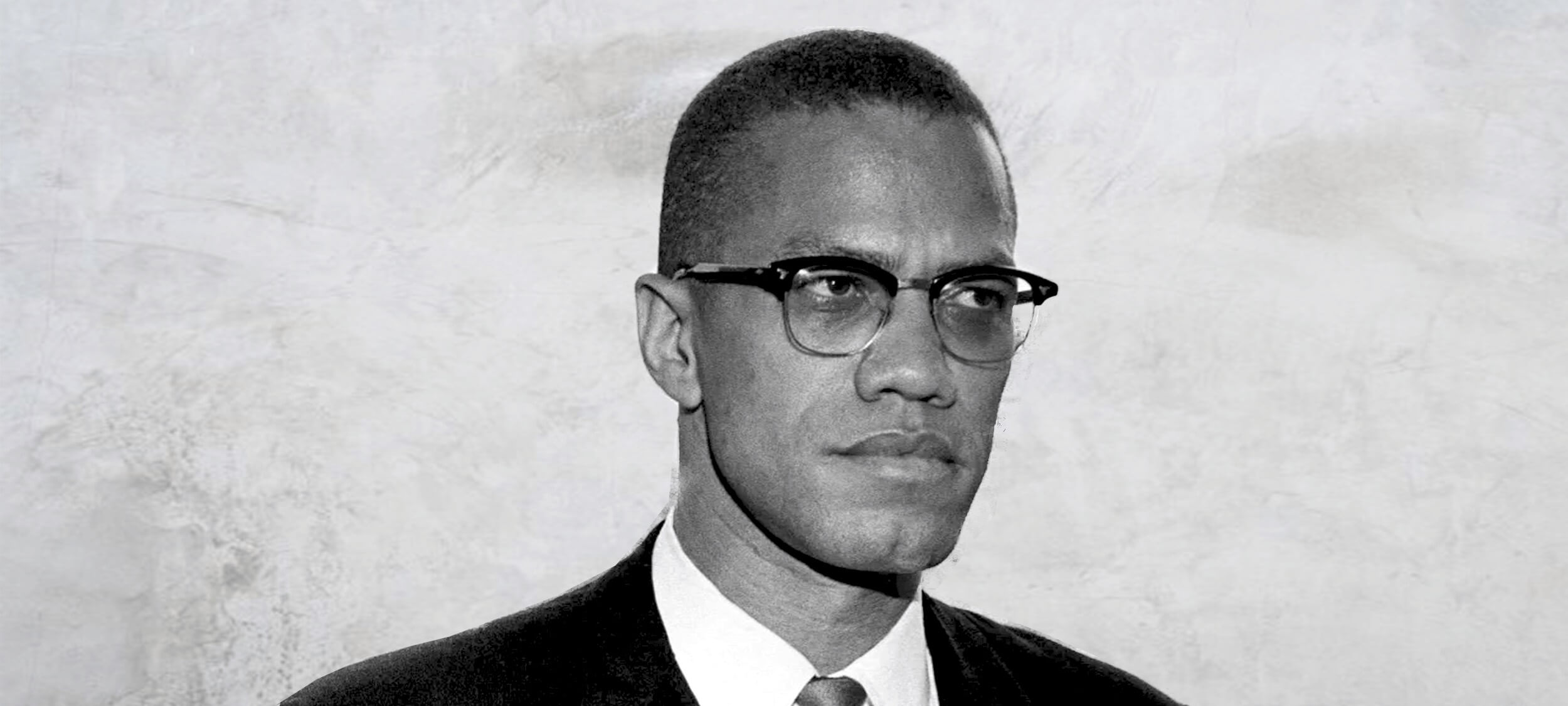

Ethics Explainer: Freedom of Speech

Ethics Explainer: Freedom of Speech

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 22 FEB 2017

Freedom of speech refers to people’s ability to say what they want without punishment.

Most people focus on punishment by the state but social disapproval or protest can also have a chilling effect on free speech. The consequences of some kinds of speech can make people feel less confident in speaking their mind at all.

Since most philosophers agree there is no such thing as absolute free speech, the debate largely focuses on why we should restrict what people say. Many will state, “I believe in free speech except…”. What comes after that? This is where the discussion on what the exceptions and boundaries to free speech are.

Even John Stuart Mill, who is so influential on this topic we need to discuss his ideas at length, thought free speech has limits. You would usually be free to say, “Immigrants are stealing our jobs”. If you say so in front of an angry mob of recently laid off workers who also happen to be outside an immigrant resource centre, you might cause violence. Mill believed you should face consequences for remarks like these.

This belief stems from Mill’s harm principle, which states we should be free to act unless we’re harming someone else. He thought the only speech we should forbid is the kind that causes direct harm to other people.

Mill’s support for free speech is related to his consequentialist views. He thought we should be governed by laws leading to the best long-term outcomes. By allowing people to voice their views, even those we find immoral, society gives itself the best chance of learning what’s “true”.

This happens in two ways. First, the majority who think something is immoral might be wrong. Second, if the majority are right, they’ll be more confident of their position if they’ve successfully argued for it. In either case, free speech will improve society.

If we silence dissenting views, it assumes we already have the right opinion. Mill said “all silencing of discussion is an assumption of infallibility”.

Accepting the limits of our own knowledge means allowing others to speak their mind – even if we don’t like what they’ve got to say.

As Noam Chomsky said, “If you’re in favour of freedom of speech, that means you’re in favour of freedom of speech precisely for views you despise”.

Free speech advocates tend to limit restrictions on speech to ‘direct’ harms like violence or defamation. Others think the harm principle is too narrow in definition. They believe some speech can be emotionally damaging, socially marginalising, and even descend into hate speech. They believe the speech that causes ‘indirect’ harms should also be restricted.

This leads people to claim citizens do not have the right to be offensive or insulting. Others disagree. Some don’t believe offence is socially or psychologically harmful. Furthermore, they suggest we cannot reasonably predict what kinds of speech will cause offence. Whether speech is acceptable or not becomes subjective. Some might find any view offensive if it disagrees with their own, which would see increasing calls for censorship.

In response, a range of theorists suggest offending is harmful and causes injury. They also say it has insidious effects on social cohesion because it places victims in a constant state of vulnerability.

In Australia, Race Commissioner Tim Soutphommasane is a strong proponent of this view. He believes certain kinds of speech “undermine the assurance of security to which every member of a good society is entitled”. Judith Butler goes further. She believes once you’ve been the victim of “injurious speech”, you lose control over your sense of place. You no longer know where you are welcome or when the next abuse will occur.

For these reasons, those who support only narrow limits to free speech are sometimes accused of prioritising speech above other goods like harmony and respect. As Soutphommasane says, “there is a heavy price to freedom that is imposed on victims”.

Whether you think offences count as harms or not will help determine how free you think speech should be. Regardless of where we draw the line, there will still be room for people to say things that are obnoxious, undiplomatic or insensitive without formal punishment. Having a right to speak won’t mean you are always seen as saying the right thing.

This encourages us to include ideas from deontology and virtue ethics into our thinking. As well as asking what will lead to the best society or which kinds of speech will cause harm, consider different questions. What are our duties to others when it comes to the way we talk? How would a wise or virtuous person use speech?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

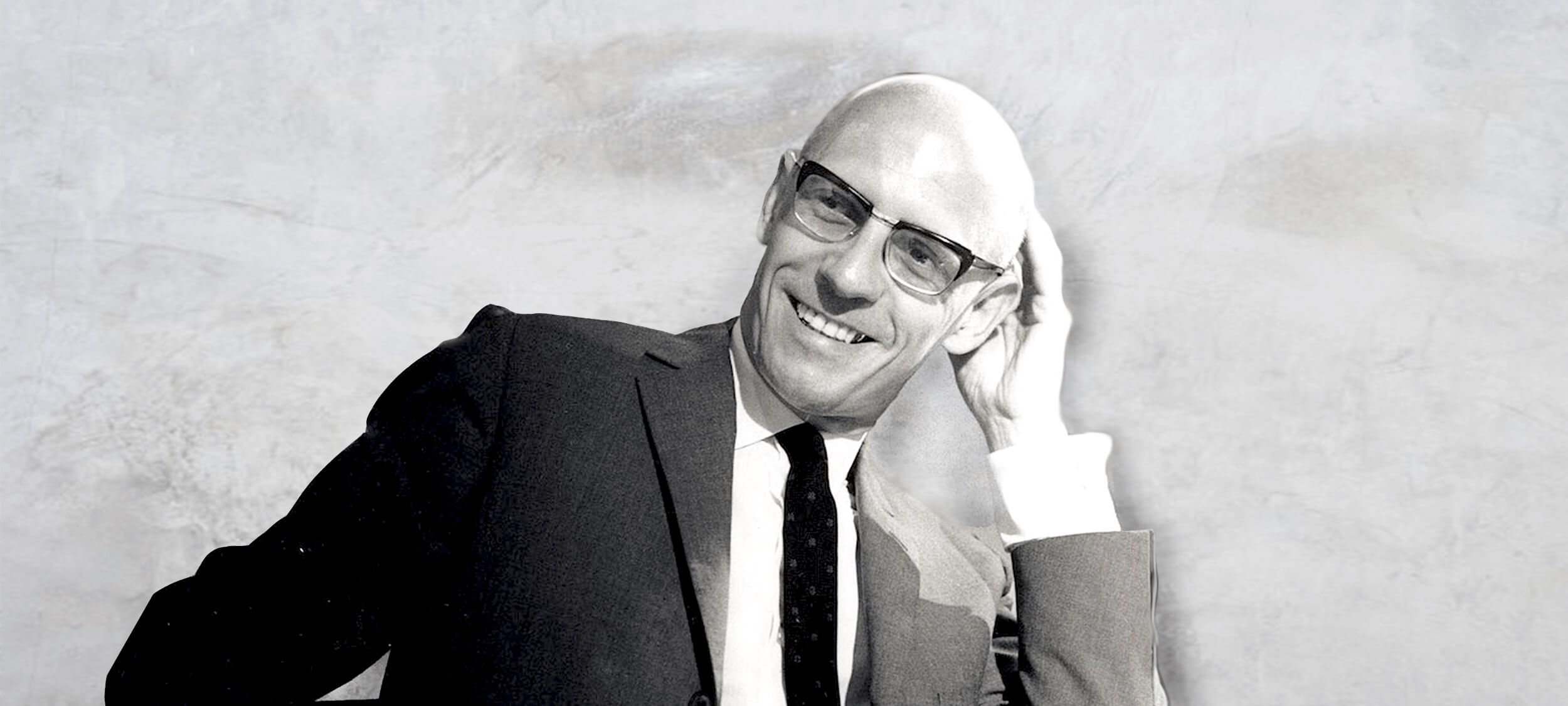

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 JAN 2017

When we say someone or something has dignity, we mean they have worth beyond their usefulness and abilities. To possess dignity is to have absolute, intrinsic and unconditional value.

The concept of dignity became prominent in the work of Immanuel Kant. He argued objects can be valuable in two different ways. They can have a price or dignity. If something has a price, it is valuable only because it is useful to us. By contrast, things with dignity are valued for their own sake. They can’t be used as tools for our own goals. Instead, we are required to show them respect. For Kant, dignity was what made something a person.

Dignity through the ages

Beliefs about where dignity comes from vary between different philosophical and religious systems. Christians believe humans have dignity because they’re made in the image of God. This is called imago dei. Kant believed humans possessed dignity because they’re rational. Others believe dignity is a way of recognising our common humanity. Some say it’s a social construct we created because it’s useful. Whatever its origin, the concept has become influential in political and ethical discourse today.

A question of human rights

Dignity is often seen as a central notion for human rights. The preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognises the “inherent dignity” of “all members of the human family”. By recognising dignity, the Declaration acknowledges ethical limits to the ways we can treat other people.

Kant captured these ethical limits in his idea of respect for persons. In every interaction with another person we are required to treat them as ends in themselves rather than tools to achieve our own goals. We fail to respect people when we treat them as tools for our own convenience or don’t give adequate attention to their needs and wishes.

When it comes to practical matters, it’s not always clear what ‘dignity and respect for persons’ require us to do. For example, in debates around assisted dying (also called assisted suicide or euthanasia) both sides use dignity to argue for opposing conclusions.

Advocates believe the best way to respect dignity is by sparing people from unnecessary or unbearable suffering, while opponents believe dignity requires us never to intentionally kill someone. They claim dignity means a person’s value isn’t diminished by pain or suffering and we are ethically required to remind the patient of this, even if the patient disagrees.

Who makes the rules?

There are also disputes about exactly who is worthy of dignity. Should it be exclusive to humans or extended to animals? And do all animals possess intrinsic value and dignity or just specific species? If animals do have dignity, we’re required to treat them with same respect we afford our fellow human beings.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Trust

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Constructing an ethical healthcare system

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Nurses and naked photos

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 27 OCT 2016

The harm principle says people should be free to act however they wish unless their actions cause harm to somebody else.

The principle is a central tenet of the political philosophy known as liberalism and was first proposed by English philosopher John Stuart Mill.

The harm principle is not designed to guide the actions of individuals but to restrict the scope of criminal law and government restrictions of personal liberty.

For Mill – and the many politicians, philosophers and legal theorists who have agreed with him – social disapproval or dislike (“mere offence”) for a person’s actions isn’t enough to justify intervention by government unless they actually harm or pose a significant threat to someone.

The phrase “Your freedom to swing your fist ends where my nose begins” captures the general sentiment of the principle, which is why it’s usually linked to the idea of “negative rights”. These are demands someone not do something to you. For example, we have a negative right to not be assaulted.

On the other hand, “positive rights” demand that others do certain things for us, like provide healthcare or treat us with basic respect. For this reason, the principle is often used in political debates to discuss the limitations of state power.

There’s no issue with actions that are harmful to the individual themselves. If you want to smoke, drink, or use drugs to excess, you should be free to do so. But if you get behind the wheel of a car while under the influence, pass second-hand smoke onto other people, or become violent on certain drugs, then there’s good reason for the government to get involved.

Attempting to define harm

The sticking point comes in trying to define what counts as harmful. Although it might seem obvious, it’s actually not that easy. For example, if you benefit by winning a promotion at work while other applicants lose out, does this count as being harmful to them?

Mill would argue no. He defines harms as wrongful setbacks to interests to which people have rights. He would argue you wouldn’t be harming anyone by winning a promotion because although their interests are set back, no particular person has a right to a promotion. If it’s earned on merit, then it’s fair. “May the best person win”, so to say.

A more difficult category concerns harmful speech. For Mill, you do not have the right to incite violence – this is obviously harmful as it physically hurts and injures. However, he says you do have the right to offend other people – having your feelings hurt doesn’t count as harm.

Recent debates have questioned this and claim that certain kinds of speech can be as damaging psychologically as a physical attack – either because they’re personally insulting or because they entrench established power dynamics and oppress minorities.

Importantly, Mill believed the harm principle only applied to people who are able to exercise their freedom responsibly. For instance, paternalism over children was acceptable since children are not fully capable of responsibly exercising freedom, but paternalism over fully autonomous adults was not.

Unfortunately, he also thought these measures were appropriate to use against “barbarians”, by which he meant non-Europeans in British colonies like India.

This highlights an important point about the harm principle: the basis for determining who is worthy or capable of exercising their freedom can be subject to personal, cultural or political bias. When making decisions about rights and responsibilities, we should be ever careful about the potential biases that inform who or what we apply them to.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Freedom and disagreement: How we move forward

WATCH

Relationships

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Ethics, morality & law

Ethics Explainer: Ethics, morality & law

ExplainerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 27 SEP 2016

Some people talk about their personal ethics, others talk about a set of morals, and everyone in a society is governed by the same set of laws. They can be easy to conflate.

Knowing the difference and relationship between them is important though, because they can conflict with one another. If the law conflicts with our personal values or a moral system, we have to act – but to do so we need to be able to tell the difference between them.

Ethics

Ethics is a branch of philosophy that aims to answer the basic question, “What should I do?” It’s a process of reflection in which people’s decisions are shaped by their values, principles, and purpose rather than unthinking habits, social conventions, or self-interest.

Our values, principles, and purpose are what give us a sense of what’s good, right, and meaningful in our lives. They serve as a reference point for all the possible courses of action we could choose. On this definition, an ethical decision is one made based on reflection about the things we think are important and that is consistent with those beliefs.

While each person is able to reflect and discover their own sense of what’s good, right, and meaningful, the course of human history has seen different groups unify around different sets of values, purposes and principles. Christians, consequentialists, Buddhists, Stoics and the rest all provide different answers to that question, “What should I do?” Each of these answers is a ‘morality’.

Morality

Many people find morality extremely useful. Not everyone has the time and training to reflect on the kind of life they want to live, considering all the different combinations of values, principles, and purposes. It’s helpful for them to have a coherent, consistent account that has been refined through history and can be applied in their day to day lives.

Many people also inherit their morality from their family, community or culture – it’s rare for somebody to ‘shop around’ for the morality that most closely fits their personal beliefs. Usually the process is unconscious. There’s a challenge here: if we inherit a ready-made answer to the question of how we should live, it’s possible to apply it to our lives without ever assessing whether the answer is satisfactory or not.

We might live our whole lives under a moral system which, if we’d had the chance to think about, we would have rejected in part or in full.

Law

The law is different. It’s not a morality in the strict sense of the word because, at least in democratic nations, it tries to create a private space where individuals can live according to their own ethical beliefs or morality. Instead, the law tries to create a basic, enforceable standard of behaviour necessary in order for a community to succeed and in which all people are treated equally.

Because of this, the law is narrower in focus than ethics or morality. There are some matters the law will be agnostic on but which ethics and morality have a lot to say. For example, the law will be useless to you if you’re trying to decide whether to tell your competitor their new client has a reputation for not paying their invoices, but our ideas about what’s good and right will still guide our judgement here.

There is a temptation to see the law and ethics as the same – so long as we’re fulfilling our legal obligations we can consider ourselves ‘ethical’. This is mistaken on two fronts. First, the law outlines a basic standard of behaviour necessary for our social institutions to keep functioning. For example, it protects basic consumer rights. However, in certain situations the right thing to in solving a dispute with a customer might require us to go beyond our legal obligations.

Secondly, there may be times when obeying the law would require us to act against our ethics or morality. A doctor might be obligated to perform a procedure they believe is unethical or a public servant might believe it’s their duty to leak classified information to the press. Some philosophers have argued that a person’s conscience is more binding on them than any law, which suggests to the letter of the law won’t be an adequate substitute for ethical reflection.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Kimberlé Crenshaw

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Social Contract

Social contract theories see the relationship of power between state and citizen as a consensual exchange. It is legitimate only if given freely to the state by its citizens and explains why the state has duties to its citizens and vice versa.

Although the idea of a social contract goes as far back as Epicurus and Socrates, it gained popularity during The Enlightenment thanks to Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Today the most popular example of social contract theory comes from John Rawls.

The social contract begins with the idea of a state of nature – the way human beings would exist in the world if they weren’t part of a society. Philosopher Thomas Hobbes believed that because people are fundamentally selfish, life in the state of nature would be “nasty, brutish and short”. The powerful would impose their will on the weak and nobody could feel certain their natural rights to life and freedom would be respected.

Hobbes believed no person in the state of nature was so strong they could be free from fear of another person and no person was so weak they could not present a threat. Because of this, he suggested it would make sense for everyone to submit to a common set of rules and surrender some of their rights to create an all-powerful state that could guarantee and protect every person’s right. Hobbes called it the ‘Leviathan’.

It’s called a contract because it involves an exchange of services. Citizens surrender some of their personal power and liberty. In return the state provides security and the guarantee that civil liberty will be protected.

Crucially, social contract theorists insist the entire legitimacy of a government is based in the reciprocal social contract. They are legitimate because they are the only ones the people willingly hand power to. Locke called this popular sovereignty.

Unlike Hobbes, Locke thought the focus on consent and individual rights meant if a group of people didn’t agree with significant decisions of a ruling government then they should be allowed to join together to form a different social contract and create a different government.

Not every social contract theorist agrees on this point. Philosophers have different ideas on whether the social contract is real, or if it’s a fictional way to describe the relationship between citizens and their government.

If the social contract is a real contract – just like your employment contract – people could be free not to accept the terms. If a person didn’t agree they should give some of their income to the state they should be able to decline to pay tax and as a result, opt out of state-funded hospitals, education, and all the rest.

Like other contracts, withdrawing comes with penalties – so citizens who decide to stop paying taxes may still be subject to punishment.

Other problems arise when the social contract is looked at through a feminist perspective. Historically, social contract theories, like the ones proposed by Hobbes and Locke, say that (legitimate) state authority comes from the consent of free and equal citizens.

Philosophers like Carole Pateman challenge this idea by noting that it fails to deal with the foundation of male domination that these theories rest on.

For Pateman the myth of autonomous, free and equal individual citizens is just that: a myth. It obscures the reality of the systemic subordination of women and others.

In Pateman’s words the social contract is first and foremost a ‘sexual contract’ that keeps women in a subordinate role. The structural subordination of women that props up the classic social contract theory is inherently unjust.

The inherent injustice of social contract theory is further highlighted by those critics that believe individual citizens are forced to opt in to the social contract. Instead of being given a choice, they are just lumped together in a political system which they, as individuals, have little chance to control.

Of course, the idea of individuals choosing not to opt in or out is pretty impractical – imagine trying to stop someone from using roads or footpaths because they didn’t pay tax.

To address the inherent inequity in some forms of social contract theory, John Rawls proposes a hypothetical social contract based on fundamental principles of justice. The principles are designed to provide a clear rationale to guide people in choosing to willingly agree to surrender some individual freedoms in exchange for having some rights protected. Rawls’ answer to this question is a thought experiment he calls the veil of ignorance.

By imagining we are behind a veil of ignorance with no knowledge of our own personal circumstances, we can better judge what is fair for all. If we do so with a principle in place that would strive for liberty for all at no one else’s expense, along with a principle of difference (the difference principle) that guarantees equal opportunity for all, as a society we would have a more just foundation for individuals to agree to a contract that in which some liberties would be willingly foregone.

Out of Rawls’ focus on fairness within social contract theory comes more feminist approaches, like that of Jean Hampton. In addition to criticising Hobbes’ theory, Hampton offers another feminist perspective that focuses on extending the effects of the social contract to interpersonal relationships.

In established states, it can be easy to forget the social contract involves the provision of protection in exchange for us surrendering some freedoms. People can grow accustomed to having their rights protected and forget about the liberty they are required to surrender in exchange.

Whether you think the contract is real or just a useful metaphor, social contract theory offers many unique insights into the way citizens interact with government and each other.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Time for Morrison’s ‘quiet Australians’ to roar

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How far should you go for what you believe in?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

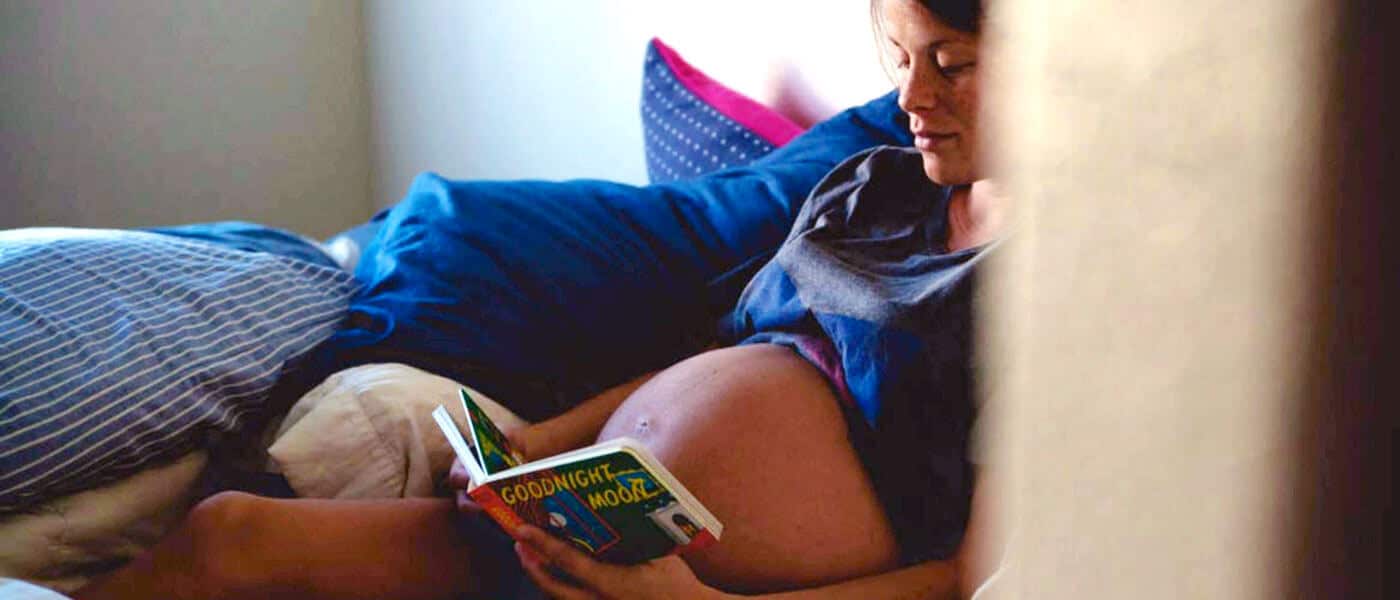

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY Hannah Dahlen The Ethics Centre 2 AUG 2016

Just try mentioning ‘birth plans’ at a party and see what happens. Hannah Dahlen – a midwife’s perspective

Mia Freedman once wrote about a woman who asked what her plan was for her placenta. Freedman felt birth plans were “most useful when you set them on fire and use them to toast marshmallows”. She labelled people who make these plans as “birthzillas” more interested in birth than having a baby.

In response, Tara Moss argued:

The majority of Australian women choose to birth in hospital and all hospitals do not have the same protocols. It is easy to imagine they would, but they don’t, not from state to state and not even from hospital to hospital in the same city. Even individual health practitioners in the same facility sometimes do not follow the same protocols.

The debate

Why the controversy over a woman and her partner writing down what they would like to have done or not done during their birth? The debate seems not to be about the birth plan itself, but the issue of women taking control and ownership of their births and what happens to their bodies.

Some oppose birth plans on the basis that all experts should be trusted to have the best interests of both mother and baby in mind at all times. Others trust the mother as the person most concerned for her baby and believe women have the right to determine what happens to their bodies during this intimate, individual, and significant life event.

As a midwife of some 26 years, I wish we didn’t need birth plans. I wish our maternity system provided women with continuity of care so by the time a woman gave birth her care provider would fully know and support her well-informed wishes. Unfortunately, most women do not have access to continuity of care. They deal with shift changes, colliding philosophical frameworks, busy maternity units, and varying levels of skill and commitment from staff.

There are so many examples of interventions that are routine in maternity care but lack evidence they are necessary or are outright harmful. These include immediate clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord at birth, episiotomy, continuous electronic foetal monitoring, labouring or giving birth laying down and unnecessary caesareans. Other deeply personal choices such as the use of immersion in water for labour and birth or having a natural birth of the placenta are often not presented as options, or are refused when requested.

The birth plan is a chance to raise and discuss your wishes with your healthcare provider. It provides insight into areas of further conversation before labour begins.

I once had a woman make three birth plans when she found out her baby was in a breech presentation at 36 weeks. One for a vaginal breech birth, one for a cesarean, and one for a normal birth if the baby turned. The baby turned and the first two plans were ditched. But she had been through each scenario and carved out what was important for her.

Bashi Hazard – a legal perspective

Birth plans were introduced in the 1980s by childbirth educators to help women shape their preferences in labour and to communicate with their care providers. Women say preparing birth plans increases their knowledge and ability to make informed choices, empowers them, and promotes their sense of safety during childbirth. Some (including in Australia) report that their carefully laid plans are dismissed, overlooked, or ignored.

There appears to be some confusion about the legal status or standing of birth plans. Neither is reflective of international human rights principles or domestic law. The right to informed consent is a fundamental principle of medical ethics and human rights law and is particularly relevant to the provision of medical treatment. In addition, our common law starts from the premise that every human body is inviolate and cannot be subject to medical treatment without autonomous, informed consent.

Pregnant women are no exception to this human rights principle nor to the common law.

If you start from this legal and human rights premise, the authoritative status of a birth plan is very clear. It is the closest expression of informed consent that a woman can offer her caregiver prior to commencing labour. This is not to say she cannot change her mind but it is the premise from which treatment during labour or birth should begin.

Once you accept that a woman has the right to stipulate the terms of her treatment, the focus turns to any hostility and pushback from care providers to the preferences a woman has the right to assert in relation to her care.

Mothers report their birth plans are criticised or outright rejected on the basis that birth is “unpredictable”. There is no logic in this.

Care providers who understand the significance of the human and legal right to informed consent begin discussing a woman’s options in labour and birth with her as early as the first antenatal visit. These discussions are used to advise, inform, and obtain an understanding of the woman’s preferences in the event of various contingencies. They build the trust needed to allow the care provider to safely and respectfully support the woman through pregnancy and childbirth. Such discussions are the cornerstone of woman-centred maternity healthcare.

Human Rights in Childbirth

Reports received by Human Rights in Childbirth indicate that care provider pushback and hostility towards birth plans occurs most in facilities with fragmented care or where policies are elevated over women’s individual needs. Mothers report their birth plans are criticised or outright rejected on the basis that birth is “unpredictable”. There is no logic in this. If anything, greater planning would facilitate smoother outcomes in the event of unanticipated eventualities.

In truth, it is not the case that these care providers don’t have a birth plan. There is a birth plan – one driven purely by care providers and hospital protocols without discussion with the woman. This offends the legal and human rights of the woman concerned and has been identified as a systemic form of abuse and disrespect in childbirth, and as a subset of violence against women.

It is essential that women discuss and develop a birth plan with their care providers from the very first appointment. This is a precious opportunity to ascertain your care provider’s commitment to recognising and supporting your individual and diverse needs.

Gauge your care provider’s attitude to your questions as well as their responses. Expect to repeat those discussions until you are confident that your preferences will be supported. Be wary of care providers who are dismissive, vague or non-responsive. Most importantly, switch care providers if you have any concerns. The law is on your side. Use it.

Making a birth plan – some practical tips

- Talk it through with your lead care provider. They can discuss your plans and make sure you understand the implications of your choices.

- Make sure your support network know your plan so they can communicate your wishes.

- Attending antenatal classes will help you feel more informed. You’ll discover what is available and the evidence is behind your different options.

- Talk to other women about what has worked well for them, but remember your needs might be different.

- Remember you can change your mind at any point in the labour and birth. What you say is final, regardless of what the plan says.

- Try not to be adversarial in your language – you want people working with you, not against you. End the plan with something like “Thank you so much for helping make our birth special”.

- Stick to the important stuff.

Some tips on the specific content of your birth plan are available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How far should you go for what you believe in?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

The road back to the rust belt

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Australian debate about asylum seekers and refugees

BY Hannah Dahlen

Hannah Dahlen is a professor of Midwifery at Western Sydney University and a practising midwife.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Just War Theory

Just war theory is an ethical framework used to determine when it is permissible to go to war. It originated with Catholic moral theologians like Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas, though it has had a variety of different forms over time.

Today, just war theory is divided into three categories, each with its own set of ethical principles. The categories are jus ad bellum, jus in bello, and jus post bellum. These Latin terms translate roughly as ‘justice towards war’, ‘justice in war’, and ‘justice after war’.

Jus ad bellum

When political leaders are trying to decide whether to go to war or not, just war theory requires them to test their decision by applying several principles:

- Is it for a just cause?

This requires war only be used in response to serious wrongs. The most common example of just cause is self-defence, though coming to the defence of another innocent nation is also seen as a just cause by many (and perhaps the highest cause).

- Is it with the right intention?

This requires that war-time political leaders be solely motivated, at a personal level, by reasons that make a war just. For example, even if war is waged in defence of another innocent country, leaders cannot resort to war because it will assist their re-election campaign.

- Is it from a legitimate authority?

This demands war only be declared by leaders of a recognised political community and with the political requirements of that community.

- Does it have due proportionality?

This requires us to imagine what the world would look like if we either did or didn’t go to war. For a war to be ‘just’ the quality of the peace resulting from war needs to superior to what would have happened if no war had been fought. This also requires we have some probability of success in going to war – otherwise people will suffer and die needlessly.

- Is it the last resort?

This says we should explore all other reasonable options before going to war – negotiation, diplomacy, economic sanctions and so on.

Even if the principles of jus ad bellum are met, there are still ways a war can be unjust.

Jus in bello

These are the ethical principles that govern the way combatants conduct themselves in the ‘theatre of war’.

- Discrimination requires combatants only to attack legitimate targets. Civilians, medics and aid workers, for example, cannot be the deliberate targets of military attack. However, according the principle of double-effect, military attacks that kill some civilians as a side-effect may be permissible if they are both necessary and proportionate.

- Proportionality applies to both jus ad bellum and jus in bello. Jus in bello requires that in a particular operation, combatants do not use force or cause harm that exceeds strategic or ethical benefits. The general idea is that you should use the minimum amount of force necessary to achieve legitimate military aims and objectives.

- No intrinsically unethical means is a debated principle in just war theory. Some theorists believe there are actions which are always unjustified, whether or not they are used against enemy combatants or are proportionate to our goals. Torture, shooting to maim and biological weapons are commonly-used examples.

- ‘Following orders’ is not a defence as the war crime tribunals after the Second World War clearly established. Military personnel may not be legally or ethically excused for following illegal or unethical orders. Every person bearing arms is responsible for their conduct – not just their commanders.

Jus post bello

Once a war is completed, steps are necessary to transition from a state of war to a state of peace. Jus post bello is a new area of just war theory aimed at identifying principles for this period. Some of the principles that have been suggested (though there isn’t much consensus yet) are:

- Status quo ante bellum, a Latin term meaning ‘the way things were before war’ – basically rights, property and borders should be restored to how they were before war broke out. Some suggest this is a problem because those can be the exact conditions which led to war in the first place.

- Punishment for war crimes is a crucial step to re-installing a just system of governance. From political leaders down to combatants, any serious offences on either side of the conflict need to be brought to justice.

- Compensation of victims suggests that, as much as possible, the innocent victims of conflict be compensated for their losses (though some of the harms of war will be almost impossible to adequately compensate, such as the loss of family members).

- Peace treaties need to be fair and just to all parties, including those who are guilty for the war occurring.

Just war theory provides the basis for exercising ‘ethical restraint’ in war. Without restraint, philosopher Michael Ignatieff, argues there is no way to tell the difference between a ‘warrior’ and a ‘barbarian’.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Freedom of expression, the art of…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Nurses and naked photos

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Learning risk management from Harambe

Learning risk management from Harambe

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Gav Schneider The Ethics Centre 2 JUN 2016

Traditional and social media channels were flooded with the story of Harambe, a 17-year-old western lowland silverback gorilla shot dead at Cincinnati Zoo on 28 May 2016 after a four-year-old boy crawled through a barrier and fell into his enclosure.

With the benefit of hindsight, forming an opinion is easy. There are already plenty being thrown around regarding the incident and who was to blame for the tragedy.

The need to kill Harambe is exceptionally depressing: a gorilla lost his life, the zoo lost a real asset, a mother was at risk of losing her child, and staff tasked by the zoo to shoot Harambe faced emotional trauma based on the bond they likely formed with him.

In technical risk management terms, the zoo seems to have been in line with best practice.

Overall, it was a bad state of affairs. Though the case gives rise to a number of ethical issues, one way to consider it is as a risk management issue – where it presents us with some important lessons that might prevent similar circumstances from happening in the future, and ensure they are better managed if they do.

In technical risk management terms, the zoo seems to have been in line with best practice.

According to Cincinnati Zoo’s annual report, 1.5 million visitors visited the park in 2014 to 2015. Included in those numbers are hundreds of parents who visited the zoo with children who didn’t end up in any of the animal enclosures.

According to WLWT-TV, this was the first breach at the zoo since its opening in 1978. There is no doubt the zoo identified this risk and managed it with secure (until now) enclosures. There is also little doubt relevant signage and duty of care reminders would have been placed around the zoo. Staff would assume parents would manage their children and keep them safe. In the eyes of most risk management experts, this would seem to be more than sufficient.

Organisations need to put energy and effort into so called ‘black swan’ events… that are unlikely but have immense consequences if they do occur.

However, as we have seen in several cases (including Cecil the Lion) it does not seem to be the incident itself that brings the massive negative consequences but rather social media, based on the fact that the internet provides a platform for everyone to be judge and jury.

This flags the massive shift required in the way we manage risk. If we look only at the financial losses to the zoo, their decision may seem logical and rational. They were truly put in a no-win position – an immediate tactical decision was required once Harambe began dragging the child around the water.

Imagine if they had decided to tranquillise Harambe and the four-year-old boy had died while they were waiting for the tranquillisers to take effect – what would the impact have been?

The true lesson regarding this issue lies in the need for organisations to put energy and effort into so-called ‘black swan’ events – ones that are unlikely but have immense consequences if they do occur. These events are often overlooked, based only on the fact they are unlikely, leaving organisations unprepared for when they do.

The ethics of what is right and wrong tend to blur when the masses have a platform to pass judgement.

Traditional risk management approaches try to allocate scores to things and then put associated resources to the highest ranking risk issues. In this case, a risk that was deemed managed actually occurred and the result was very negative.

Whether negligent or not, various social media commentators have held the mother accountable. It seems she has been held to account based not on what she did, but for the apparently unapologetic and callous way she responded to the killing of Harambe.

This shows us risk management needs to consider the human element in a way we previously haven’t. The ethics of what is right and wrong tend to blur when the masses have a platform to pass judgement. There are many lessons to be taken from this incident, including the following considerations:

- Risk management and duty of care should be incorporated in a more cohesive manner, focusing on applying a BDA approach (Before, During and After).

- Social media backlash adds a new dimension to the way organisations should make, report and defend their decisions.

- Individuals can no longer purely blame the organisation they believe responsible based on negligence or breach of duty of care. Even if the individual shifts blame onto the organisation entirely, and they are not held to account by the law, they will be held to account by the general public.

- We have entered an era where system- and process-based risk management needs to integrate human and emotive elements to account for emotional responses.

- Lastly – and unrelatedly – the question of why one story attracts massive public outcry and why another doesn’t raises ethical questions regarding the way we consume news, the way the media reports it, and the upsides and downsides of social media.

In short this is another case of how much work we still have to do – especially in the modern internet age – to proactively and ethically manage risk.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How far should you go for what you believe in?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights