Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

Ethics of care is a feminist approach to ethics. It challenges traditional moral theories as male-centric and problematic to the extent they omit or downplay values and virtues usually culturally associated with women or with roles that are often cast as ‘feminine’.

The best example of this may be seen in how ethics of care differs from two dominant normative moral theories of the 18th and 19th century. The first is deontology, best associated with Immanuel Kant’s ethics. The second is consequentialism, best associated with Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism and improved upon by John Stuart Mill.

Each of these moral theories require or encourage the moral agent to be unemotional. Moral decision-making is expected to be rational and logical, with a focus on universal, objective rules. In contrast, ethics of care defends some emotions, such as care or compassion, as moral.

On this view, there isn’t a dichotomy between reason and the emotions, as some emotions can be reasonable, morally appropriate or even helpful in guiding good decisions or actions. Feminist ethics also recognises that rules must be applied in a context, and real life moral decision-making is influenced by the relationships we have with those around us.

Instead of asking the moral decision-maker to be unbiased, the caring moral agent will consider that one’s duty may be greater to those they have particular bonds with, or to others who are powerless rather than powerful.

In a Different Voice

Traditional proponents of feminist care ethics include 20th century theorists Carol Gilligan and Nel Noddings. Gilligan’s influential 1982 book, In a Different Voice, claimed that Sigmund Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis and Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of moral development were biased and male-oriented.

On these dominant psychological accounts of human development, male development is taken as standard, and female development is often judged as inferior in various ways.

Gilligan argued if women are ‘more emotional’ than men, and pay more attention to relationships rather than rules, this is not a sign of them being less ethical, but, rather, of different values that are equally valuable. While Gilligan may have deemed these differences to be ‘natural’ and associated with sex rather than gender, these differences may well have been socially constructed and therefore the result of upbringing.

How might the ethics of care theorist resolve the classical ‘Heinz’ dilemma: Should a moral agent steal the required medicine he cannot afford to buy to give to his very sick wife, or stick to the rule ‘do not steal’, regardless of the circumstances? A tricky dilemma, to be sure, as there are competing duties here (namely, a positive duty to help those in need as well as a negative duty to avoid stealing).

Arguably, the caring person would place the relationship with one’s spouse above any relationship they may or may not have with the pharmacist, and care or compassion or love would outweigh a rule (or a law) in this case, leading to the conclusion that the right thing to do is to steal the medicine.

It’s worth noting that a utilitarian might also claim a moral agent should steal the medicine because saving the wife’s life is a better outcome than whatever negative consequences may result from stealing. However, the reasoning that leads to this conclusion is based on unemotional weighing of costs and benefits, rather than a consideration of the relationships involved and asking what love might demand.

Writing at the same time as Gilligan, Noddings also defended care as a particular form of moral relationship. She asserted that caring was “ethically basic” to humans and that it can be seen in children’s behaviour. While Noddings does not rule men out from being caring, it is usually women who feature in her examples of caregivers.

Noddings, like Gilligan, prioritises relationships that are between specific individuals in a particular context as the basis for ethical behaviour. This stands in contrast to the idea that morality involves following universal, abstract or purely logical moral rules.

Who cares?

Ethics of care has been influential in areas like education, counselling, nursing and medicine. Yet there have also been feminist criticisms. Some worry that it maintains a sexist stereotype and encourages or assumes women nurture others, even while society fails to value carers as they should.

Noddings and Gilligan both argue against this, saying that the capacity for care is a general human strength, and while it is empowering to acknowledge it as a positive capacity in women, it should be encouraged regardless of gender.

Join us for a timely conversation on the unseen perspectives, ethical dilemmas, and shifting cultural expectations around care – one of the most fundamental aspects of being human. The Ethics of Care is live and online on Thursday 28 August 2025 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

The transformative power of praise

The transformative power of praise

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Professor Bob Murray 11 MAY 2019

What is it about the legal industry that makes it so depressing? Well, it is not the work – but it could be exhaustion mixed with a lack of control about how much work they can handle and a shortage of appreciation from their bosses.

Psychologist and a scientist in behavioural neurogenetics, Bob Murray, says human beings are designed to work as little as 10 hours per week.

“If we work for more than 10 hours a week, it becomes stress,” he told a recent seminar in Sydney.

While that may seem an extreme position at first glance, it is important to understand what Professor Murray means by “work”.

“Work” is the stuff we do that is a grind. It is, perhaps, the administrative work that takes us away from the tasks that are meaningful or enjoyable.

“Work means not necessarily enjoying yourself, not necessarily relating. Human beings are relationship-forming animals. We are driven to surround ourselves with a network of supportive relationships and we can work hard and long… providing that we do it in the company of other people that we actually like, and that we enjoy the process of doing things with them.

“It’s not a question of how many hours you work. It’s whether you enjoy the process of doing that work. And whether you enjoy the people that you do it with”.

Murray said people come to work to be part of a tribe and to learn.

“So people in law firms are willing to stay there for long hours, providing they’re enjoying the process of learning what they’re doing,” he said.

Murray says 30 percent of all lawyers think about suicide once a year and 40 percent are clinically depressed.

A national survey of almost 1000 lawyers finds that excessive job demands, minimal control over workload and spillover of work commitments into personal life are some of the work-related factors correlated with poorer mental health outcomes.

“Concerns about the structure and culture of legal practice in Australia are also highlighted,” say the authors of the study, Lawyering Stress and Work Culture: An Australian Study, 2012-2013.

He says one relatively simple thing that employers and managers can do is to praise their people. However, only around 5 percent of people get praised once a day.

Praise is powerful because of its effect on the “feel good” chemicals we produce, like dopamine, which helps our brains work faster, smarter, and more creatively.

However, poorly given praise tends to antagonise people. Murray says there are three elements to effective praise:

What: The giver has to be specific about what they are praising. A generic “well-done team” can have the opposite effect.

How: This is the effort or the way someone has gone about something. It is the kind of praise you may give a child who comes last in a race, but stuck it out to the end, gave it their best effort and didn’t let the team down. It is not necessarily tied to success, but encourages and rewards the right behaviours.

Who: This is praise for the relationship. “ I really enjoy working with you. It’s great to have you as part of you of my team.” Murray says this kind of praise is less used in law firms than other kinds – but is the most powerful.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Businesses can’t afford not to be good

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Should corporate Australia have a voice?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

BY Professor Bob Murray

Professor Bob Murray, is a principal at consultancy Fortinberry Murray, was speaking on a panel, hosted by The Legal Forecast and Clarence Workplaces for Lawyers in Sydney.

Big Thinker: Buddha

Gautama Buddha lived during the 5th century BCE and was the founder of the Buddhist religion. He also developed a rich philosophical system of thought that challenged notions of permanence and personal identity.

Buddhism is typically considered a religion but it also has a strong philosophical foundation and has inspired a rich tradition of philosophical inquiry, especially in India and China, and, increasingly, Western countries.

Buddhism emerged from the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, an Indian prince who turned his back on a life of leisure and opulence. Instead, he sought to understand the causes of suffering and how we might be able to be liberated from it.

Coincidentally, Gautama Buddha lived around the 5th Century BCE, which is at a similar time to two other great philosophers in different corners of the world – Socrates in Ancient Greece and Confucius in China – both of whom sparked their own major philosophical traditions.

Desire, happiness and suffering

Like many philosophers – from Aristotle to Peter Singer – one might say the Buddha was interested in how to live a good life. The starting point of his teachings is that life is suffering, which sounds like a pessimistic start, but he was just reminding us none of us can escape things like illness, death, loss, or these days, doing our tax returns.

Buddha went on to explain suffering is not random or uncaused. In fact, he argued if we can come to understand the causes of suffering, then we can do something about it. We can even become liberated from suffering and achieve nirvana, which is a state of pure enlightenment.

Many philosophers believe this teaching is just as relevant today as it was over 2,000 years ago. We’re told today that we ought to be happy, and that happiness comes from being able to satisfy our desires. Our entire economy is predicated on this idea. So we work hard, earn money, get stressed, buy more stuff, yet many of us can’t seem to find deeper satisfaction.

It turns out that no matter what desires we satisfy, there are more desires that crop up to take their place. And there are some desires that never go away, like the desire for status or wealth, and some desires that can never be satisfied, like when we experience unrequited love. And when we can’t satisfy our desires, we experience suffering.

The Buddha said this is because we have our theory of happiness backwards. Happiness doesn’t come from satisfying ever more desires – it comes from reducing our desires so there are fewer that need to be satisfied. It’s only when we desire nothing and we can just be that we are truly free from suffering.

Thus the Buddha argues our suffering is not caused by the whims of an indifferent world outside of our control. Rather, the cause of suffering is within our own minds. If we can change our minds, we can find liberation from suffering. This led him to develop a theory of our minds and how we perceive reality.

Permanence

He said that one of the fundamental mistakes in the way we think about the world is to believe in the permanence of things. We assume (or desire) that things will last forever, whether that be our youth, our possessions or our relationships with loved ones, and we become attached to them.

So when they inevitably erode, decay or disappear – we grow old, our possessions wear out, our loved ones move on – we suffer. But this suffering is only because we failed to realise that nothing is permanent, that all things are in flux, and if we can come to enjoy things without being attached to them, then we would suffer less.

Tibetan Buddhist monks have a ritual where they spend weeks painstakingly creating incredibly detailed and beautiful mandalas made out of coloured sand. Then, once they’re finished, they ritualistically sweep the sand away, destroying the mandala, and drop the collected sand into a river to flow back into the world, representing their embrace of impermanence.

The self

Another core philosophical insight from Buddhism was to question our sense of self. It’s natural to believe there is something at the core of our being that is unchanging, whether that be our soul, mind or personality.

But the Buddha noted when you try to pin down what that permanent aspect of ourselves is, you find there’s nothing there, just a stream of impressions, thoughts and feelings. So our sense that there is a persistent self is ultimately an illusion. We are just as dynamic and impermanent as the rest of the world around us. And if we can realise this, we can release ourselves from the pretense of what we think we are and we can just be.

Interestingly, this is very similar to an observation made by the 18th century Scottish philosopher David Hume, who said when he introspected, he could never settle on the solid core to his self. Rather, his self was like a swarm of bees with no boundary and no hard centre, with each being an individual thought or experience. The Buddha would likely have enjoyed this analogy.

Meditation

One of the aspects of Buddhism that has had the most lasting impact is the practice of meditation, particularly mindful meditation. The recent mindfulness movement is based on a form of Buddhist meditation that encourages us to sit quietly and let our thoughts come and go without judgement. Essentially, we must ignore our thoughts in order to control and be free from them. Modern science has shown that this kind of meditation can reduce stress and improve our focus and mood.

Buddhism is not only the fourth largest religion in the world with over 500 million adherents today, and third largest in Australia, but it continues to be a rich vein of philosophical inquiry.

Western philosophy was rather slow to take Buddhism seriously, but there are now many Western philosophers who are engaging with Buddhist ideas about reality, knowledge, the mind, the self and ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kate Prendergast 24 APR 2019

It began in Oakden. Or, it began with the implosion of one of the most monstrously run aged care facilities in Australia, as tales of abuse and neglect finally came to light.

That was May 2017. Two years on, we are in the midst of the first Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, announced following a recommendation by the Scott Morrison government.

The first hearings began this year in Oakland’s city of Adelaide. They have seen countless brave witnesses come forward to share their experiences of what it’s like to live within the aged care system or see a loved one deteriorate or die – sometimes peacefully, sometimes painfully – within it.

In May, the third hearing round will take place in Sydney. This round will hear from people in residential aged care, with a focus on people living with dementia – who make up over 50 percent of residents in these facilities.

With our burgeoning ageing population, the number of people being diagnosed with dementia is expected to increase to 318 people per day by 2025 and more than 650 people by 2056.

Encompassing a range of different illnesses, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and Lewy body disease, its symptoms are particularly cruel, dissolving intellect, memory and identity. In essence, dementia describes the gradual estrangement of a person from themselves – and from everyone who knew them.

It is one of the most prevalent health problems affecting developed nations today – and one of the most feared. Contrary to widespread belief, one in 15 sufferers are in their thirties, forties and fifties.

Physical restraints

How do you manage these incurable conditions? How can you humanely care for the remnants of a person who becomes more and more unrecognisable?

One thing the Royal Commission has made clear: you don’t do it by defaulting to dehumanising mechanisms of restraint.

Unlike in the UK or the US, there are currently no regulations around use of restraints in aged care facilities. It is commonly resorted to by aged care workers if a patient displays physical aggression, or is a danger to themselves or others.

Yet it is also used in order to manage patients perceived as unruly in chronically understaffed facilities, when the risk of leaving them unsupervised is seen to be greater than the cost of depriving them their free movement and self-esteem. The problem of how to minimise harm in these conditions is an ongoing and high-pressure dilemma for staff.

Readers may remember the distressing footage from January’s 7.30 Report, in which dementia patients were seen sedated and strapped to chairs. One of them was the 72-year-old Terry Reeves. Following acts of aggression towards a male nurse, he was restrained for a total of 14 hours in a single day. His wife, however, had authorised that her husband be restrained with a lap belt if he was “a danger to himself or others”.

Maree McCabe, director of Dementia Australia, is vocal about why physical restraints should only be used as a last resort.

“We know from the research that physical restraint overall shows that it does not prevent falls,” she says. “In fact it may cause injury, and it may cause death.”

While there are circumstances where restraint may be appropriate McCabe says, “it is not there as a prolonged intervention”. Doing so, she says, “is an infringement of their human rights”.

After the 7.30program aired and one day before the Royal Commission hearings began, the federal government committed to stronger regulations around restraint, including that homes must document the alternatives they tried first.

Restraint by drugging

Another kind of restraint which has come into focus through the Royal Commission is chemical restraint. Psychotropic medication is currently prescribed to 80 percent of people with dementia in residential care – but it is only effective 10 percent of the time.

“We need to look at other interventions,” says McCabe. “The first to look at is: why is the person behaving in the way that they are? Why are they responding that way? It could be that they’re in pain. It could be something in the environment that is distressing them.”

She notes people with dementia often have “perceptual disturbances” – “things in the environment that look completely fine to us might not to someone living with dementia”. Wouldn’t you act out of character if your blue floor suddenly became a miniature sea, or a coat hanging on the door turned into the Babadook?

“It’s about people understanding of what it’s like to stand in the world of people living with dementia and simulate that experience for them,” says McCabe.

Whether through physical force or prescription, a dependence on restraint shows the extent to which dementia is misunderstood at the detriment of the autonomy and dignity of the sufferers. This misunderstanding is compounded by the fact that dementia is often present among other complex health problems.

Yet, and as the media may sensationally suggest, the aged care sector isn’t staffed by the callous or malicious. It is filled with good people, who are often overstretched, emotionally taxed and exhausted.

Dementia Australia is advocating for mandatory training on dementia for all people who work in aged care. This covers residential aged care, but could also extend to hospitals. Crucially, it encompasses community workers, too.

“Of the 447,000 Australians living with dementia, 70 percent live in the community and 30 percent live alone,” notes McCabe. “It’s harder to monitor community care, it’s less visible and less transparent. We have to make sure that the standards are across the board.”

It is only through listening to people living with dementia – recognising that while yes, they have a degenerative cognitive disease, they deserve to participate in the decision-making around their life and wellbeing – that our approach to it has evolved. Previously, people believed that it was dangerous to allow sufferers to cook, even to go out unaccompanied.

Likewise, it is crucial that we continue to afford people with dementia the full rights of personhood, however unfamiliar they may become. Only then can meaningful reform be made possible.

Besides, if for no other reason (and there are many other reasons), action is in our own selfish interest. The chances, after all, that you or someone you love will develop dementia are high.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Kate Prendergast

Kate Prendergast is a writer, reviewer and artist based in Sydney. She's worked at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Broad Encounters and Giramondo Publishing. She's not terrible at marketing, but it makes her think of a famous bit by standup legend Bill Hicks.

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 16 APR 2019

Free Will describes our capacity to make choices that are genuinely our own. With free will comes moral responsibility – our ownership of our good and bad deeds.

That ownership indicates that if we make a choice that is good, we deserve the resulting rewards. If in turn we make a choice that is bad, we probably deserve those consequences as well. In the case of a really bad choice, such as committing murder, we may have to accept severe punishment.

The link between free will and responsibility has both theological and philosophical roots.

Within theology, for example, the claim that humans are ‘made in the image of God’ (a central tenet of major religions like Judaism, Christianity and Islam) is not that they are the physical image of their creator.

Rather, the claim is made that humans are made in the ‘moral image’ of God – which is to say that they are endowed with the ‘divine’ capacity to exercise free will.

Of course, the experience of free will is not limited to those who hold a religious belief. Philosophers also argue that it would be unjust to blame someone for a choice over which they have no control.

Determinism is the belief that all choices are determined by an unbroken chain of cause and effect. Those who believe in ‘determinism’ oppose free will, arguing that that the belief that we are the authors of our own actions is a delusion.

Whereas scientific evidence has found there is brain activity prior to the sensation of having made a choice, we’re unable to resolve the question of which account is correct.

Should that gap close – and free will be proven to be an illusion, then the basis for ascribing guilt to those who act unethically (including criminals) will also be destroyed.

How could we justify punishing a person who claims that they had no choice but to do evil?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Scepticism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If you condemn homosexuals, are you betraying Jesus?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844—1900) is one of the most controversial figures in contemporary philosophy.

A German philosopher and cultural critic who is well known for his proclamations on God, truth, morality, power, aesthetics, the self and the meaning of existence, Nietzsche has had an enduring influence on Western philosophy.

Making use of a creative writing style, such as aphorisms and emotive essays, Nietzsche’s doctrines have been famously misappropriated by those seeking to further their own political ends (for example, Hitler and the alt-right). He was seen as an early existentialist because of his insistence on existence preceding essence, and the importance of looking to yourself – rather than God, society, family or friends – to identify what values you choose to live by.

Live your life like an artist

In Nietzsche’s first major work, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), the idea of living life creatively is embodied in his idea of living life as an artist. This involves combining two energies: the rational Apollonian and the passionate Dionysian. (In Greek mythology, Apollo is the god of logic and rational thinking, and Dionysus the god of instinct and emotion.)

Nietzsche worried the society of his time and classical thinkers like Socrates and Descartes– both Rationalists – only emphasised the Apollonian, neglecting the role of the Dionysian. Nietzsche thought it was important to balance our rationality with our sensual and passionate experience of life, and he saw this balance best depicted in ancient Greek tragedies.

Nietzsche insisted Greek tragedy achieves greatness through the inclusion of both Apollonian creative energy which is responsible for the dialogue, and Dionysian energy which inspires the music or chorus. In the plays, the two work together as the meaning of the words are enhanced by the accompanying melody. Using Greek dramatic artworks as an example, we can learn from great art to see the beauty in life.

“Without music, life would be a mistake.” – Nietzsche

The tragic spectator is united with others in the shared experience of being human. For Nietzsche, life without emotion, art and the creative energy of the Dionysian is bleak. A balance between Dionysus and Apollo allows for pluralistic and authentic modes of expression that are rational as well as creative. Aesthetic ideals also appear in his later writings, such as The Will to Power (1901), where Nietzsche writes, “Art as the redemptionof the man of action… Art as the redemption of the sufferer”.

Nietzsche advocated for a series of values or virtues we should adopt – namely, active, life affirming values, as opposed to the life denying or passive and ‘slave like’ values he detested. The latter he saw exemplified in the institutionalisation of Christianity, which, he believed, served to reinforce the power of the few at the expense of the many.

Believing the idea of a punitive God promoted by the church of his time to be a human invention, he famously declared:

“God is dead … And we have killed him.”

The Superman or Nietzsche’s Übermensch

Nietzsche emphasises an individualistic development and construction of self, summed up in the notion of the will to power. Claiming we ought to seek control over ourselves, Nietzsche holds up the Superman (yes, Nietzsche was misogynistic, but for our purposes we can extend this concept to include women), or Übermensch, as the pinnacle of human potentiality in terms of power and integrity in a broad sense of the word.

Nietzsche’s Übermensch is imagined as Zarathustra, a Christ-like figure who delivers an anti-sermon on the mount, a character with whom Nietzsche identifies. In The Gay Science (1882), it is the Superman who creates strengths out of his weaknesses and thus styles his character – a “great and rare art!”

This existentialist ideal – that each individual creates one’s self in a manner pleasing to them – threatens to collapse into extreme relativism or subjectivism. Yet, despite the fact the Superman goes “beyond good and evil”, Nietzsche is a moralist with definite views on what is condemnable.

“No one can construct for you the bridge upon which precisely you must cross the stream of life, no one but you yourself alone.” – Nietzsche

One way we are invited to test whether or not our chosen action is the right one is given to us in Nietzsche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence. “The Greatest Weight” in The Gay Science tells of a demon who confronts us, suggesting we must relive every single moment of our life, every choice and its consequences, eternally.

We are asked whether we would celebrate this as a gift or curse the unending misery it presents. The Superman would embrace the opportunity due to their authenticity and the fact they made each choice consciously, willing to accept full responsibility for their life.

Such a thought experiment offers an overly ambitious understanding of freedom and free will as a positive force. Yet it provides the reader with an interesting challenge when making decisions. Knowledge of an eternal recurrence would fundamentally change the way we lead our lives and inform the choices we make. If taken seriously, one could not help but try to act authentically – or, alternatively, not act at all.

Ever the rebellious teenager of philosophy, Nietzsche continues to give us pause for much thought, challenging us to live authentically and take unflinching responsibility for our lives.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

FODI launches free interactive digital series

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Cris Parker 20 MAR 2019

“I am a trusted advisor.” That is how the man described himself when he approached me at the end of a conference.

We had gathered to discuss the implications of the Royal Commission into banking and finance and how that industry could emerge with a stronger ethical backbone.

“What is the best way to get that ethical message across?” asked the man in front of me.

Well, part of the problem was right there on his business card. You can’t self-nominate trust. You have to earn it. You can’t appropriate it yourself with a wishful job title or marketing slogan. You have to do the work and leave it to others to decide if you can be trusted. Or not.

A greater focus on trust itself

Trust has been seen as a top business priority and growing in importance over the past few years, especially after the Global Financial Crisis of 2007 where people’s life savings were misused by the people in institutions that had promised to take care of them. The rise of the populist Occupy movement four years later was a warning shot to those in power that resonated globally.

However, much of the conversation since then about the poor reputation of business has failed to come to terms with the enormity of the task ahead. Trust is often spoken about as the currency that allows companies the privilege of taking care of another person’s wealth.

Not so much is said about the process of getting there – or even whether trust is the outcome companies should be focused on.

After all, having people’s trust does not necessarily mean that you are trustworthy.

Dealing in deception

Why should “trust” not be an end in itself? Well, US stockbroker and financial advisor Bernie Madoff was widely trusted by his wealthy investors before they realised they had been collectively fleeced of $US64.8 billion in the largest Ponzi scheme in history.

Closer to home in Australia, conman Hamish McLaren took $7.66 million from 15 separate victims – many of whom were referred to him by friends and family. McLaren was so trusted that one woman handed over her divorce settlement without even asking his last name.

McLaren is the subject of The Australian newspaper’s most recent podcast series “Who the Hell is Hamish?”.

Trust, by itself, is not always what it is cracked up to be.

Restoring confidence and trust

So the question is not “How can we get people to trust us again?”, but should be instead “What can we do to become trustworthy?”. Organisations need to focus on the process of getting there, rather than the result. It will take time, there needs to be consistency in behaviour and there’s an element of forgiveness that needs to be addressed.

Forgiveness means that the forgiver needs to believe that you won’t behave that way again. Declaring your best intentions doesn’t work, it needs to be seen.

Being trustworthy means that people in your organisation behave ethically because it’s the right thing to do, not because it will make people trust them again. A reputation for trustworthiness is, again, not something you can just anoint yourself with.

A solid reputation is bestowed upon you and comes through an accumulation of other people’s personal experiences of you and your work.

Legendary investor Warren Buffett, the chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, has provided the business world with a wealth of pithy and insightful quotes through his annual letters to shareholders.

One is said to be: “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. If you think about that, you’ll do things differently”.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. An initiative of The Ethics Centre, The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

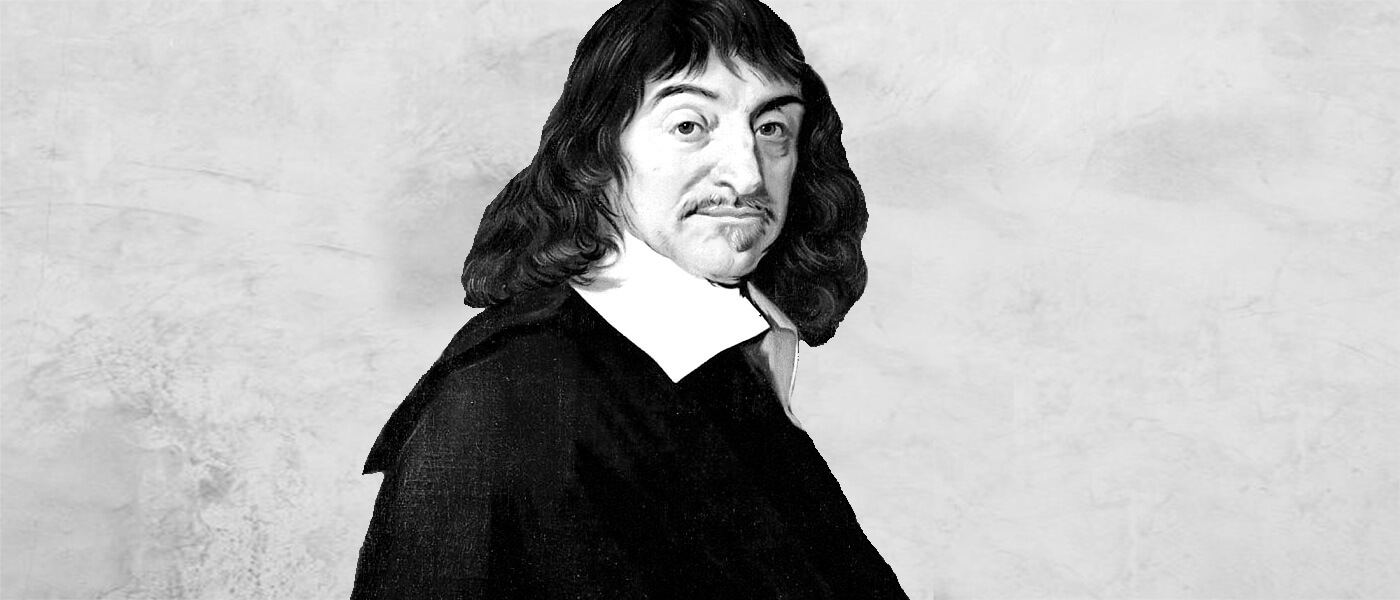

Big Thinker: René Descartes

René Descartes (1596—1650) is famous for the phrase, “I think, therefore I am”. He was a Frenchman writing in the early 17th century and was preoccupied with the question: What can we know for certain?

Descartes details a method of doubt in his key text Meditations on First Philosophy, published in 1641. It becomes crucial for rationalists that seek infallible knowledge. Rationalists rest their epistemological claims on pure reason, without recourse to the senses or experience (unlike the empiricists). Epistemology is the philosophical study of knowledge.

At a time when scholars were writing in Latin, Descartes wrote in French so anyone who was literate in the common language of his place could read his work. His writing style is friendly and approachable, so it feels as though you are having a conversation with him. His sceptical inquiry into what we can know commences with the question:

Can my senses be trusted?

Descartes describes himself sitting in front of a log fire in his wood cabin, smoking a pipe and questioning whether or not he can be sure that he is awake and alert as opposed to asleep and dreaming. How can we know the difference, he asks, when sometimes, in our dream state, we feel as though we’re awake even though we’re not?

Using the first person point of view, Descartes ponders on the fact that he tends to use his senses to be sure he exists and that the world around him is real, but the senses can sometimes be deceived. Our eyes often play tricks on us – as proven by any optical illusion – so how can we trust something that tricks us even once?

Cartesian scepticism (Cartesian being the adjective to describe the school of Decartes’ thought) concludes ultimately all I can be truly sure of is that I am a thinking thing. Descartes’ famously declared:

“Cogito ergo sum: I think therefore I am.”

Descartes posits the only thing I can be sure of is that I exist because even when I doubt that, there is an “I” doing the doubting. The “I” that thinks or doubts, must surely exist, he claims.

For Descartes the mind is more knowable than the body, and he equates the human Soul with the mind. For him, the mind is the essence of a person.

As a mathematician and a ‘natural scientist’ Descartes sought to prove that truths of the world were as immutable as rational, logical mathematic proofs. After he has proven that “I think, therefore I am” is as secure a foundation for knowledge as “1 + 1 = 2” Descartes goes on to use a thought experiment in order to consider whether we can be sure God exists.

The Evil Genius thought experiment

Descartes’ thought experiment of the evil genius asks us to imagine there exists, instead of an entirely good and powerful God, an entirely powerful, all-knowing Malevolent Demon. The idea here is that this Demon could make us think we are experiencing the world as it truly is, but we aren’t really. We could be tricked by this Evil Genius, and we may not be able to trust any knowledge we receive about the world from our senses. Ultimately Descartes relies upon an Ontological or Rational Argument to prove that God exists and if God exists, then we can trust our senses as God would not fool us in such a way as the Evil Demon might.

The incredibly powerful questions Descartes asks still inform many of our science fiction fears as we wonder whether or not the world truly is as it appears to us. We can still see the power of doubting and if we take this worry too seriously, we can imagine being paralysed with fear, unable to do anything! Many of us accept that our senses can be tricked but we know that we just have to go on trusting them anyway and hope for the best.

This sceptical method Descartes outlines whereby we check what we believe to be true and question what we assume to be real is useful if we think of it in terms of seeking evidence for the beliefs we are taught and the assumptions we hold. Considered in this way, Descartes offers us a great tool for self-reflection. However, if we take this thought experiment seriously we may never be sure that even we ourselves exist!

In the 18th century, David Hume suggested that even the assumption of an ‘I’ that doubts is an illusion. Hume says all we have to go on is a string of conscious experiences. Whether we are truly awake or dreaming right now is something we may not be able to answer with absolute accuracy, a doubt played out in famous films like The Matrix and Inception.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to help your kid flex their ethical muscle

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

After Christchurch

After Christchurch

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 19 MAR 2019

What is to be said about the murder of innocents?

That the ends never justify the means? That no religion or ideology transmutes evil into good? That the victims are never to blame? That despicable, cowardly violence is as much the product of reason as it is of madness?

What is to be said?

Sometimes… mute, sorrowful silence must suffice. Sometimes… words fail and philosophy has nothing to add to our intuitive, gut-wrenching response to unspeakable horror.

Thus, we bow our heads in silence… to honour the dead, to console the living, to be as one for the sake of others.

In that silence… what is to be said?

Nothing.

Yet, I feel compelled to speak. To offer some glimmer of insight that might hold off the dark — the dark shades of vengeance, the dark tides of despair, the dark pools of resignation.

So, I offer this. Even in the midst of the greatest evil there are people who deny its power. They are rare individuals who perform ‘redemptive’ acts that affirm what we could be. Some call them saints or heroes. They are both and neither. They are ordinary people who act with pure altruism – solely for the sake of others, with nothing to gain.

One such person is with me every day. The Polish doctor and children’s author, Janusz Korczak, cared for orphaned Jewish children confined to the Warsaw Ghetto. At last, the time came when the children were to be transported to their place of extermination. Korczak led his children to the railway station — but was stopped along the way by German officers. Despite being a Jew, Korczak was so revered as to be offered safe passage.

To choose life, all he need do was abandon the children. At the height of the Nazi ascendancy, Korczak had no reason to think that he would be remembered for a heroic but futile death. He had nothing to gain. Yet, he remained with the children and with them went to his death. He did so for their sake — and none other. In that decision, he redeemed all humanity — because what he showed is the other face of our being, the face that repudiates the murderer, the terrorist, the racist…the likes of Brenton Tarrant.

I know that many people do not believe in altruism. They will offer all manner of reasons to explain it away, finding knotholes of self-interest that deny the nobility of Janusz Korczak’s final act. They are wrong. I have seen enough of the world to know that pure acts of altruism are rare — but real. And it only takes one such act to speak to us of our better selves.

We will never know precisely what happened in those mosques targeted in Christchurch. However, I believe that, in the midst of the terror, there were people who performed acts of bravery, born out of altruism, of a kind that should inspire and ultimately comfort us all.

Most of these stories will be untold — lost to the silence. Of a few, we may hear faint whispers. But believe me, the acts behind those stories are every bit as real as the savagery they confronted and confounded. And even when whispered, they are more powerful.

Evil born of hate can never prevail. It offers nothing and consumes all — eventually eating its own. That is why good born of love must win the ultimate victory. Where hate takes, love gives — ensuring that, in the end, even a morsel of good will tip the balance.

You might say to me that this is not philosophy. Where is the crisp edge of logic? Where is the disinterested and dispassionate voice of reason? Today, that voice is silent. Yet, I hope you can hear the truth all the same.

Dr Simon Longstaff AO is Executive Director of The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

We are the Voice

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: René Descartes

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics Explainer: Plato's Cave

Plato’s allegory of the cave is a classical philosophical thought experiment designed to probe our intuitions about epistemology – the study of knowledge.

This story offers the reader an insight into one of Plato’s central concepts, namely, that eternal and unchanging ideas exist in an intellectual realm which we can only access through pure Reason.

Western philosophy may be traced back to Ancient Greece. We have a record of Socrates’ (469-399 BCE) oral teachings through the writings of his student, Plato (427-347 BCE). In these Socratic Dialogues, Socrates argues with his interlocutors in an effort to seek truth, meaning, and knowledge. Plato’s Republic is the best known of these and, in book VII, Socrates presents Glaucon (Plato’s older brother) with an unusual image:

Imagine a number of people living in an underground cave, which has an entrance that opens towards the daylight. The people have been in this dwelling since childhood, shackled by the legs and neck, such that they cannot move nor turn their heads to look around. There is a fire behind them, and between these prisoners and the fire, there is a low wall.

Rather like a shadow puppet play, objects are carried before the fire, from behind the low wall, casting shadows on the wall of the cave for the prisoners to see. Those carrying the objects may be talking, or making noises, or they may be silent. What might the prisoners make of these shadows, of the noises, when they can never turn their heads to see the objects or what is behind them?

Socrates and Glaucon agree that the prisoners would believe the shadows are making the sounds they hear. They imagine the prisoners playing games that include naming and identifying the shadows as objects – such as a book, for instance – when its corresponding shadow flickers against the cave wall. But the only experience of a ‘book’ that these people have is its shadow.

After suggesting that these prisoners are much like us – like all human beings – the narrative continues. Socrates tells of one prisoner being unshackled and released, turning to see the low wall, the objects that cast the shadows, the source of the noises as well as the fire.

While the prisoner’s eyes would take some time to adjust, it is imagined that they now feel they have a better understanding of what was causing the shadows, the noises, and they may feel superior to the other prisoners.

This first stage of freedom is further enhanced as the former prisoner leaves the cave (they must be forced, as they do not wish to leave that which they know), initially painfully blinded by the bright light of the sun.

The liberated one stumbles around, looking firstly only at reflections of things, such as in the water, then at the flowers and trees themselves, and, eventually, at the sun. They would feel as though they now have an even better understanding of the world.

Yet, if this same person returned to the dimly lit cave, they would struggle to see what they previously took for granted as all that existed. They may no longer be any good at the game of guessing what the shadows were – because they are only pale imitations of actual objects in the world.

The other prisoners may pity them, thinking they have lost rather than gained knowledge. If this free individual tried to tell the other prisoners of what they had seen, would they be believed? Could they ever return to be like the others?

The remaining prisoners certainly would not wish to be like the individual who returned, suddenly not knowing anything about the shadows on the cave wall!

Socrates concludes that the prisoners would surely try to kill one who tried to release them, forcing them into the painful, glaring sun, talking of such things that had never been seen or experienced by those in the cave.

Interpreting the Allegory of the Cave

There are multiple readings of this allegory. The text demonstrates that the Idea of the Good (Plato capitalises these concepts in order to elevate their significance and refer to the idea in itself rather than any one particular instantiation of that concept), which we are all seeking, is only grasped with much effort.

Our initial experience is only of the good as reflected in an earthly, embodied manner. It is only by reflecting on these instantiations of what we see to be good, that we can start to consider what may be good in itself. The closest we can come to truly understanding such Forms (the name he gives these concepts), is through our intellect.

Human beings are aiming at the Good, which Medieval philosophers and theologians equated with God, but working out what the good life consists of is not easy! Plato claims each Soul (or mind) chooses what is good, saying:

“But, whether true or false, my opinion is that in the world of knowledge the idea of good appears last of all, and is seen only with an effort.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Barbie and what it means to be human

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We need to talk about ageism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships