Big Thinker: Matthew Liao

Matthew Liao (1972 – present) is a contemporary philosopher and bioethicist. Having published on a wide range of topics, including moral decision making, artificial intelligence, human rights, and personal identity, Liao is best known for his work on the topic of human engineering.

At New York University, Liao is an Affiliate Professor in the Department of Philosophy, Director of the Center for Bioethics, and holds the Arthur Zitrin Chair of Bioethics. He is also the creator of Ethics Etc, a blog dedicated to the discussion of contemporary ethical issues.

A Controversial Solution to Climate Change

As the climate crisis worsens, a growing number of scientists have started considering geo-engineering solutions, which involves large-scale manipulations of the environment to curb the effect of climate change. While many scientists believe that geo-engineering is our best option when it comes to addressing the climate crisis, these solutions do come with significant risks.

Liao, however, believes that there might be a better option: human engineering.

Human engineering involves biomedically modifying or enhancing human beings so they can more effectively mitigate climate change or adapt to it.

For example, reducing the consumption of animal products would have a significant impact on climate change since livestock farming is responsible for approximately 60% of global food production emissions. But many people lack either the motivation or the will power to stop eating meat and dairy products.

According to Liao, human engineering could help. By artificially inducing mild intolerance to animal products, “we could create an aversion to eating eco-unfriendly food.”

This could be achieved through “meat patches” (think nicotine patches but for animal products), worn on the arm whenever a person goes grocery shopping or out to dinner. With these patches, reducing our consumption of meat and dairy products would no longer be a matter of will power, but rather one of science.

Alternatively, Liao believes that human engineering could help us reduce the amount of food and other resources we consume overall. Since larger people typically consume more resources than smaller people, reducing the height and weight of human beings would also reduce their ecological footprint.

“Being small is environmentally friendly.”

According to Liao, this could be achieved several ways for example, using technology typically used to screen embryos for genetic abnormalities to instead screen for height, or using hormone treatment typically used to stunt the growth or excessively tall children to instead stunt the growth of children of average height.

Reception

When Liao presented these ideas at the 2013 Ted Conference in New York, many audience members found the notion of wearing meat patches and making future generations smaller to be amusing. However, not everyone found these ideas humorous.

In response to a journal article Liao co-authored on this topic, philosopher Greg Bognar wrote that the authors were doing themselves and their profession a disservice by not adequately considering the feasibility or real cost of human engineering.

Although making future generations smaller would reduce their ecological footprint, it would take a long time for the benefits of this reduction in average height and weight to accrue. In comparison, the cost of making future generations smaller would be borne now.

As Bognar argues, current generations would need to devote significant resources to this effort. For example, if future generations were going to be 15-20cm shorter than current generations, we would need to begin redesigning infrastructure. Homes, workplaces and vehicles would need to be smaller too.

Liao and his colleagues do, however, recognise that devoting time, money, and brain power to pursuing human engineering means that we will have fewer resources to devote to other solutions.

But they argue that “examining intuitively absurd or apparently drastic ideas can be an important learning experience, and that failing to do so could result in our missing out on opportunities to address important, often urgent issues.”

While current generations may resent having to bear the cost of making future generations more environmentally friendly, perhaps it is a cost that we must bear.

Liao says, “We are the cause of climate change. Perhaps we are also the solution to it.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The rise of Artificial Intelligence and its impact on our future

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Hype and hypocrisy: The high ethical cost of NFTs

Hype and hypocrisy: The high ethical cost of NFTs

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Dr Tim Dean 24 MAY 2022

When you hear news of a collage fetching US$69.3 million (AUD$92.1 m) at a Christie’s auction or a pixelated punk selling for US$23.7 million (AUD$31.5 m), you’d be forgiven for thinking that there’s a new and exciting art market on the rise.

But the multi-million dollar sales and media buzz around non-fungible tokens (NFTs) mask a more complex and troubling picture of a technology that is plagued by a host of ethical problems. These include rampant scams, exacerbating wealth inequality, a staggering environmental impact and, not least, the exploitation of the artists NFTs were supposed to enrich.

It’s ironic that NFTs were originally conceived of as an ethical correction to an art market that often failed to reward artists for their effort.

One of the first NFTs was created in response to the rampant copying and sharing of digital artworks on the internet, often without attribution or compensation offered to the original artists.

The idea was to create a special kind of digital token that represented ownership of a particular artwork, similar to a digital receipt or the deed to a block of land. Artists could sell the tokens associated with their work in order to derive an income. It would also track who owned a particular artwork at any point in time, showing provenance all the way back to the original artist.

It was hoped NFTs would give artists more control over their work and create a thriving and lucrative market for them to make an income.

The blockchain seemed to be the ideal technology for creating just such a token, with it being a long ledger of transactions that is maintained by a decentralised network of computers. The most popular tokens on blockchains are cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin or Ether, but other kinds of tokens exist as well.

The big difference between a cryptocurrency token and an NFT is that the former are fungible, in the sense that any individual Bitcoin is functionally identical and worth the same amount as any other Bitcoin. In contrast, NFTs are non-fungible, so every one is unique and they might be worth very different amounts. Some NFTs also embed code that enable the artist to take a cut of all subsequent sales of that token, which could be a lucrative form of revenue if their art appreciates in value over time and is sold to new buyers.

What have I bought?

Since 2014, NFTs have evolved and become more sophisticated, many moving to the Ethereum blockchain. Most NFTs are essentially a record of ownership of a particular digital asset, like an image or video. It is important to note that the asset itself is not stored on the blockchain – it might be stored on one or more servers somewhere on the internet or offline – the NFT only contains a link or pointer to where the asset is stored.

In terms of moral rights, NFTs don’t give the owner control of the intellectual property, such as copyright, which usually remains with the artist. Owning one also doesn’t prevent the asset from being viewed, copied or downloaded by others; someone might have paid US$23.7 million for that digital punk but you can copy it to your heart’s content. Unlike traditional property, an NFT doesn’t give the owner a right to exclude others from using or benefiting from what they own.

All an NFT allows the owner to do is sell that NFT to someone else. It’s like buying the deed to a plot of land, except you’re not able to fence it off, and you can’t even prevent others from creating a second (or third, or fourth…) deed for the same plot of land.

So what does an NFT owner really own? It’s not the artwork, nor is it the right to prevent others from accessing it. What they own is the NFT. This has led some people to suggest that buying an NFT only offers “bragging rights” over a particular piece of art.

Even so, some clearly see value in that right to brag – sometimes to the tune of millions of dollars – but those bragging rights can come at a cost to many of the artists that NFTs were supposed to benefit.

Crypto patrons

One of the main selling points of NFTs is that they are a way to support artists. And there’s no doubt that some artists have done extremely well by selling NFTs. However, the promise of opening up new markets and new buyers to smaller and emerging artists has, so far, failed to materialise.

Like with conventional art, a majority of the revenue from NFT sales has flowed to a small minority of popular artists, with a tiny proportion of NFTs and buyers accounting for a vast majority of purchases and sales.

Thus, to date, NFTs have served to concentrate wealth among a few artists and investors rather than spread it around. And as new artists have entered the NFT sphere, it has only further crowded the space, lending greater advantage to those with the name recognition or resources to advertise their work.

There have been initiatives to encourage artists to create NFTs of their work in an attempt to tap into what appears to be a lucrative market, such as venture capitalist Mark Carnegie working with artists from the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre in Yirrkala in the Northern Territory. However, in order to create an NFT on the Ethereum network, the artist must pay blockchain processing fees, which could cost hundreds of dollars per transaction. If the artwork doesn’t sell and they don’t have financial backing, they might end up out of pocket.

Shark infested

NFTs have also stung many artists in other ways, particularly through plagiarisation, where someone else creates an NFT of their artwork and sells it without their knowing about it or receiving any revenue from it. This has forced some artists, like DC Comics artist Liam Sharp, off platforms like DeviantArt, where they previously displayed their work. The problem got so bad that in January 2022 one of the main platforms for trading in NFTs announced that over 80% of the NFTs created for free on its platform were “plagiarized works, fake collections, and spam.”

NFTs are also vulnerable to fraud. One popular scam is called wash trading, where one or more traders buy and sell NFTs amongst themselves, thereby inflating the price before selling them on to some unsuspecting buyer.

Another common scam is a rug pull. This is where someone generates buzz by announcing a new and exciting NFT project with big promises of future features. But after the creators sell the first tranche of NFTs, they close the project, take the money and run. Sometimes they have even locked the NFTs from being traded, preventing buyers from recouping any of their money by selling the NFTs on the open market.

Another example of NFT fraud includes classic social engineering, where scammers pretend to be official representatives of NFT marketplaces, thus gaining access to victims’ crypto wallets, enabling them to transfer cryptocurrency or NFTs into their own wallets.

All of these scams represent a deeper ethical problem than just a few miscreant operators exploiting rare loopholes. They’re due to fundamental problems with the NFT system itself because it contains few protections against these kinds of exploits.

If a commercial business opened an auction house that had no protections against people selling things they didn’t own, or failed to follow through on delivering promised goods, or that didn’t have robust policies to protect against social engineering scams, it would likely be closed down by regulators.

Decentralised means unregulated

One of the claimed merits of the blockchain is its unregulated nature. The network of technologies, financial tools, cryptocurrencies and NFTs is sometimes proudly referred to as decentralised finance (DeFi) by enthusiasts.

The deregulated nature of DeFi also means that users are not reliant on banks or other conventional institutions to handle transactions, so they are also not covered by the same regulations and protections that people enjoy when using a bank.

This has led some commentators, including prominent technology journalist Cory Doctorow, to refer to DeFi as “shadow banking 2.0”. This is a reference to the first generation of “shadow banking,” which included all the highly obscure and largely unregulated financial instruments that contributed to the global financial crisis in 2008.

Compounding the problem is the inclusion of “smart contracts” in many NFTs. These are small bits of code that trigger under particular circumstances, like allowing an artist to receive a future cut of sales. But smart contracts have also been used for nefarious purposes, such as directly stealing money from people who own NFTs.

Hot air

Every time you make a transaction on the Ethereum network, such as buying or selling an NFT, you burn through roughly 229 kilowatt hours (kWh) of power, generating 128 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). That’s about the same amount of energy consumed by a typical NSW home over two whole weeks. Ethereum, the most popular platform for NFTs, burns nearly 100 terawatt hours each year, which is comparable to the energy consumption of Ghana, emitting over 54 million tonnes of CO2e.

This is because blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum use vast amounts of computing power, distributed over countless individual computers around the world, in order to continually validate and cross-validate each new transaction. The cost is not only in terms of energy prices but also their impact on the planet.

While many other products label their carbon emissions, and many offer consumers low carbon options or carbon offsets, no such options are available for NFTs. In fact, if you were to offset the emissions of a single transaction at current Australian carbon credit prices of around $30 per tonne of CO2e, it would cost you about $4. And if you tried to offset the total emissions of the entire Ethereum network, it would cost $1.6 billion dollars – not that there’d likely be enough offsets to cover that carbon debt.

Is it ethical to buy NFTs?

Even if you care about artists deriving an income from their work and you want to open up new markets to smaller and emerging artists, then it’s difficult to justify NFTs on these grounds alone.

If you believe that an ethical marketplace ought to have basic consumer protections to prevent scams and fraud, then it’s difficult to endorse NFTs given their deregulated nature, complexity and the many loopholes that are vulnerable to abuse.

And if you consider yourself ethically responsible for the emissions that you produce, particularly those related to discretionary expenses, then it is difficult to justify the emissions required to make even a single NFT transaction.

All of this is entirely separate to considerations of whether NFTs are a good financial investment, whether they’re a virtual asset bubble, or even if NFTs represent something that carries meaningful property rights.

If you want to support artists, buy their art. Thankfully, there are many ways of doing so that don’t involve the blockchain, cryptocurrencies, DeFi or NFTs.

Artwork by Yuga Labs, Bored Ape Yacht Club, 2021

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

How to build good technology

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The “good enough” ethical setting for self-driving cars

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Why the EU’s ‘Right to an explanation’ is big news for AI and ethics

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Lucy Peach 1 APR 2022

Most people probably know more about the cycle on a washing machine than the one that got us all here. I’m talking about the menstrual cycle (again).

It’s true that we’ve made major gains in shedding some of the menstrual stigma in recent years but there is still a lack of awareness and interest in the cyclical lives of 26% of all people on Earth. There are real consequences to this.

For a start, menstrual education is still reduced to two things: the management of a period and how to control our capacity to reproduce. No one explained that the hormones of the menstrual cycle weren’t just for making babies and that my cycle hormones shape who and how I am. I didn’t know, that far from being an unpredictable rollercoaster (that I would internalise as constant feelings of being too much or not enough), that there was a pattern to the emotional landscape of my month, that there were predictable phases to the cycle that could be harnessed. That it was ok to feel differently from week to week.

At a tender age, I learnt that my body was a problem to be fixed, with pads, tampons and soon enough with the pill. I believed I was safest while my cycle was disarmed. Until I was ready for a baby, what was the point in having one at all or so I thought? The truth is, without ovulation, we have no hormones and therefore no cycle at all. I wonder, would I have been so eager to reject ovulation in favor of the pill during my teens and twenties had I known of this?

I didn’t know that there were short and long-term protective health benefits to ovulation that taking the pill would eliminate. I didn’t know it was common to feel depressed and flat while taking it. I felt crazy. Instead of cultivating care and curiosity for my young body and what it could do, I leant not to trust it.

This disregard for menstrual cycles extended to the scientific community such that until the 90’s, clinical trials for new drugs weren’t required to include women at all.

Because menstrual cycles were seen as too complicated, men were considered the biological norm.

It seems that even amid a growing movement of awareness and appreciation for menstrual cycles, this default male setting still persists.

When thousands and thousands of women and menstruators reported changes to their cycle after taking the Covid vaccine, their concerns were initially dismissed by the medical fraternity. Women were waved away and stress was cited as the probable culprit for the mostly temporary changes.

It is true that stress can wreak havoc on a cycle — and who hasn’t felt stressed in new ways since the arrival of the pandemic? But the real kicker, was that there was no proof to speak of; important early clinical trials investigating the side effects of the Covid vaccine failed to consider the impacts on women’s menstrual cycles. This glaring omission at such a critical juncture is menstrual stigma still in action. That women were dismissed before being asked about their experiences after the vaccine is an indictment into how far we haven’t come.

Women were dismissed before being asked about their experiences after the vaccine is an indictment into how far we haven’t come.

In the absence of due diligence, people worried and concerns for post vaccination fertility also proliferated, risking confidence in the vaccine unnecessarily.

Vaccines work by creating an immune response which can cause the body stress. It stands to reason that there might be side effects to our cycles when our immune system is triggered. The latest research was funded by the NIH and published in Obstetrics and Gynecology. It was confirmed that while changes were (on average) minor and temporary, it was true: there was an impact. After looking at three cycles before and after vaccination, on average, the impact on cycle length following vaccination was just under a day.

For people who had both shots within one cycle, the average cycle length extension was 2 days and of these people, there were 10% who experienced cycle delays of 8 days or more. All of these changes were reported to have been resolved within two subsequent cycles and there was no effect found on the length of the bleed itself. Obviously within all of the experiences that create averages, the range for individuals could be considerable but with variations of up to 8 days considered to be within the realm of a normal cycle, these results are generally reassuring. Furthermore, in another study with more than 2000 couples there was no difference found in fertility when comparing unvaccinated and vaccinated couples. Conversely, a Covid infection was associated with a temporary decline in male fertility. So far so good.

Research like this is a positive step after a bungled start and authors of the menstrual study have called for more investigation into how the Covid-19 vaccination could affect other aspects of menstruation such as pain and changes to the bleeding itself. Going forward, bigger sample sizes that also include menstruators with more varied experiences are important.

With access to information and the stains of stigma beginning to fade, women and menstruators are learning to listen to their bodies and to speak up about their experiences. To be wary of doctors who prescribe the pill to fix a period when it merely masks underlying issues. To demand better than the average wait time of eight years to receive an endometriosis diagnosis and subsequent treatments. Weary of being disregarded when it comes to our health, we are finally beginning to trust ourselves. As Lisa Hendrickson-Jack explains in ‘The Fifth Vital Sign’, the menstrual cycle gives us important insights and is a critical marker of our overall health, just like heart rate or body temperature. Understanding your menstrual cycle is basic body literacy that is crucial to wellness.

The changes to menstrual cycles may be no more significant than a sore arm, but that doesn’t mean we don’t deserve to know about them. Small changes can still be significant to people hoping to plan or avoid a pregnancy, for instance. We need vaccines to combat Covid but we also need to be informed.

If there are any silver linings to be had during Covid it’s that we know that the old ‘normal’ wasn’t working for many of us.

Women’s health has long been overlooked, under-researched and under reported and now perhaps the new normal is to consider women’s health from the outset.

Hopefully it will be for the future we are carrying.

Normalise asking people about their cycles whether you are a researcher, a doctor, a partner or even a friend. Normalise noticing your own cycle and how you feel throughout the month. Normalise expecting better.

Lucy Peach, day 28 and vaccinated.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Academia’s wicked problem

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The rise of Artificial Intelligence and its impact on our future

BY Lucy Peach

Lucy Peach is a long-time champion of the power of the menstrual cycle and an advocate for self-love and positive body literacy. She’s educated and empowered thousands with her theatre performances, workshops, and book, using science stories and songs to shift the period narrative in our culture from one of shame to one of pride. Lucy has spent the past two decades studying human biology, woman’s health & wellbeing, and Menstruality Leadership. She has a Bachelor of Science in human biology and biomedicine with honours in medicine, and a graduate diploma of education in human biology.

Ukraine hacktivism

Ukraine hacktivism

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff 2 MAR 2022

As reported by David Crowe in the Sydney Morning Herald, Ukraine’s Foreign Minister, Dmytro Kuleba, has recently called on individuals, from other countries, to join the fight against Russia’s invasion.

“Foreigners willing to defend Ukraine and world order as part of the International Legion of Territorial Defence of Ukraine, I invite you to contact foreign diplomatic missions of Ukraine”, he said on Sunday night.

It is important to note that it is illegal for Australians to take up this call. As things stand, Australians commit a criminal office if they fight for any formation other than properly constituted national armed forces. This prohibition was introduced to deter and punish Australians hoping to fight in the ranks of ISIS. However, it applies far more generally. As such, it proscribes an age-old practice of individuals engaging in warfare in support of causes they wish to champion. Unlike mercenaries (who will fight for whichever side will pay them the better price), there have been people, throughout history, willing to risk their lives and limbs for idealistic reasons.

More recent examples include those who joined the International Brigade to fight Fascist forces in Spain during the early part of the Twentieth Century, those who joined the Kurds to oppose ISIS, in recent years, and also those who fought with and for ISIS in order to establish a Caliphate in the Middle East.

It should be noted that the choices mentioned above are not morally equivalent – even though the underlying motivation is, essentially, the same. Those who opposed Fascism in the 1930s did not employ terrorism as a principal tactic. ISIS did – unrestrained by any of the ethical limitations arising out of the Just war tradition.

That tradition was developed to deal with forms of war which took place in real time and across real battlespaces where combatants and non-combatants could be killed by a direct encounter with a lethal weapon or its effects.

In recent days, this discussion has taken on a new character as volunteer ‘hacktivists’ have taken up virtual arms, on Ukraine’s behalf, in a cyber-war against Russian forces. Once again, there are non-Ukrainian nationals engaged in a conflict that pits them against an aggressor – not for financial reward, not for reasons of self-preservation but simply because they feel compelled to defend an ideal. Of course, there are bound to be some amongst their ranks who are just in it for the mischief. However, I think most will be sincere in their conviction that they are doing some good.

That said, there is some truth to the old adage that ‘the road to hell is paved with good intentions’. It is not enough to be realising a noble purpose. One also needs to employ legitimate means. It is this thought that lies behind the observation, by Canadian philosopher Michael Ignatieff, that the difference between a ‘warrior’ and a ‘barbarian’ lies in ethical restraint.

In an ideal world, those who belong to the profession of arms are trained to apply ethical restraint in their use of force. The allegations levelled against a few members of the SAS, in Afghanistan, indicate that there can be a gap between the ideal and the actual. However, in the vast majority of cases, Australia’s professional shoulders serve as ‘warriors’ rather than ‘barbarians’.

But what of the ethical restraint required of volunteer cyber-warriors? There are some general observations, as outlined by Dr Matt Beard and I in our publication Ethical By Design: Principles for Good Technology. Our first principle is that ‘CAN does NOT imply OUGHT’. That is, the mere fact that you can do something does not mean that you should!. However, I think that some of the traditional ethical restraints derived from ‘just war theory’ should also apply.

There are three principles of particular importance. First, you need to be satisfied that you are pursuing a just cause. Self-defence and the defence of others who have been attacked without just cause have always been allowed – with one proviso … your own use of force must be directed at securing a peace that is superior to that which would have prevailed if no force had been used.

That accounts for the ends that one might pursue. When it comes to the means, they need to accord with the principles of ‘discrimination’ and proportionality’. The first says that you may only attack a legitimate target (a combatant, military infrastructure, etc.). The second requires you only to use the minimal amount of force needed to achieve one’s legitimate ends.

President Putin’s forces have violated all three principles of just war. He has invaded another nation without just cause. He is targeting non-combatants (innocent women and children) and he is employing weaponry (and threatening an escalation) that is entirely disproportionate.

The fact that he does so does not justify others to do the same.

Volunteer cyber-warriors have to be extremely careful that in their zeal to harm Putin and his armed forces, they do not deliberately (or even inadvertently) harm innocent Russians who have been sucked into one man’s war.

Of course, this means fighting with the equivalent of ‘one arm tied behind the back’. The temptation is to fight ‘fire with fire’ – but that only leads to the loss of one of one’s ‘moral authority’. The hard lessons of history have taught us that this is a potent weapon in itself.

The law might not prevent a cyber-warrior from fighting on the side of Ukraine from a desk somewhere in Australia. However, one should at least pause to consider the ethical dimension of what you propose to do and how you propose to go about it.

There can be honour in being a cyber-warrior. There is none in being a cyber-barbarian.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Thought experiment: The original position

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why Anzac Day’s soft power is so important to social cohesion

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

You’re the Voice: It’s our responsibility to vote wisely

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Joseph Earp 22 FEB 2022

Dr. Chris Letheby, a pioneer in the philosophy of psychedelics, is looking at a chair. He is taking in its individuated properties – its colour, its shape, its location – and all the while, his brain is binding these properties together, making them parts of a collective whole.

This, Letheby explains, is also how we process the self. We know that there are a number of distinct properties that make us who we are: the sensation of being in our bodies, the ability to call to mind our memories or to follow our own trains of thought. But there is a kind of mental glue that holds these sensations together, a steadfast, mostly uncontested belief in the concrete entity to which we refer when we use the word “me.”

“Binding is a theoretical term,” Letheby explains. “It refers to the integration of representational parts into representational wholes. We have all these disparate representations of parts of our bodies and who we were at different points at time and different roles we occupy and different personality traits. And there’s a very high-level process that binds all of these into a unified representation; that makes us believe these are all properties and attributes of one single thing. And different things can be bound to this self model more tightly.”

Freed from the Self

So what happens when these properties become unbound from one another – when we lose a cohesive sense of who we are? This, after all, is the sensation that many experience when taking psychedelic drugs. The “narrative self” – the belief that we are an individuated entity that persists through time – dissolves. We can find ourselves at one with the universe, deeply connected to those around us.

Perhaps this sounds vaguely terrifying – a kind of loss. But as Letheby points out, this “ego dissolution” can have extraordinary therapeutic results in those who suffer from addiction, or experience deep anxiety and depression.

“People can get very harmful, unhealthy, negative forms of self-representation that become very rigidly and deeply entrenched,” Letheby explains.

“This is very clear in addiction. People very often have all sorts of shame and negative views of themselves. And they find it very often impossible to imagine or to really believe that things could be different. They can’t vividly imagine a possible life, a possible future in which they’re not engaging in whatever the addictive behaviours are. It becomes totally bound in the way they are. It’s not experienced as a belief, it’s experienced as reality itself.”

This, Letheby and his collaborator Philip Gerrans write, is key to the ways in which psychedelics can improve our lives. “Psychedelics unbind the self model,” he says. “They decrease the brain’s confidence in a belief like, ‘I am an alcoholic’ or ‘I am a smoker’. And so for the first time in perhaps a very long time [addicts] are able to not just intellectually consider, but to emotionally and experientially imagine a world in which they are not an alcoholic. Or if we think about anxiety and depression, a world in which there is hope and promise.”

A comforting delusion?

Letheby’s work falls into a naturalistic framework: he defers to our best science to make sense of the world around us. This is an unusual position, given some philosophers have described psychedelic experiences as being at direct odds with naturalism. After all, a lot of people who trip experience what have been called “metaphysical hallucinations”: false beliefs about the “actual nature” of the universe that fly in the face of what science gives us reason to believe.

For critics of the psychedelic experience then, these psychedelic hallucinations can be described as little more than comforting falsehoods, foisted upon the sick – whether mentally or physically – and dying. They aren’t revelations. They are tricks of the mind, and their epistemic value remains under question.

But Letheby disagrees. He adopts the notion of “epistemic innocence” from the work of philosopher Lisa Bortolotti, the belief that some falsehoods can actually make us better epistemic agents. “Even if you are a naturalist or a materialist, psychedelic states aren’t as epistemically bad as they have been made out to be,” he says, simply. “Sometimes they do result in false beliefs or unjustified beliefs … But even when psychedelic experiences do lead to people to false beliefs, if they have therapeutic or psychological benefits, they’re likely to have epistemic benefits too.”

To make this argument, Letheby returns again to the archetype of the anxious or depressed person. This individual, when suffering from their illness, commonly retreats from the world, talking less to their friends and family, and thus harming their own epistemic faculties – if you don’t engage with anyone, you can’t be told that you are wrong, can’t be given reasons for updating your beliefs, can’t search out new experiences.

“If psychedelic states are lifting people out of their anxiety, their depression, their addiction and allowing people to be in a better mode of functioning, then my thought is, that’s going to have significant epistemic benefits,” Letheby says. “It’s going to enable people to engage with the world more, be curious, expose their ideas to scrutiny. You can have a cognition that might be somewhat inaccurate, but can have therapeutic benefits, practical benefits, that in turn lead to epistemic benefits.”

As Letheby has repeatedly noted in his work, the study of the psychiatric benefits of psychedelics is in its early phases, but the future looks promising. More and more people are experiencing these hallucinations – these new, critical beliefs that unbind the self – and more and more people are getting well. There is, it seems, a possible world where many of us are freed from the rigid notions of who we are and what we want, unlocked from the cage of the self, and walking, for the first time in a long time, in the open air.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Can robots solve our aged care crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Mehhma Malhi 18 FEB 2022

The use of deepfake technology is increasing as more companies devise different models.

It is a form of technology where a user can upload an image and synthetically augment a video of a real person or create a picture of a fake person. Many people have raised concerns about the harmful possibilities of these technologies. Yet, the notion of deception that is at the core of this technology is not entirely new. History is filled with examples of fraud, identity theft, and counterfeit artworks, all of which are based on imitation or assuming a person’s likeliness.

In 1846, the oldest gallery in the US, The Knoedler, opened its doors. By supplying art to some of the most famous galleries and collectors worldwide, it gained recognition as a trusted source of expensive artwork – such as Rothko’s and Pollock’s. However, unlike many other galleries, The Knoedler allowed citizens to purchase the art pieces on display. Shockingly, in 2009, Ann Freedman, who had been appointed as the gallery director a decade prior, was famously prosecuted for knowingly selling fake artworks. After several buyers sought authentication and valuation of their purchases for insurance purposes, the forgeries came to light. The scandal was sensational, not only because of the sheer number of artworks involved in the deception that lasted years but also because millions of dollars were scammed from New York’s elite.

The grandiose art foundation of NYC fell as the gallery lost its credibility and eventually shut down. Despite being exact replicas and almost indistinguishable, the understanding of the artist and the meaning of the artworks were lost due to the lack of emotion and originality. As a result, all the artworks lost sentimental and monetary value.

Yet, this betrayal is not as immoral as stealing someone’s identity or engaging in fraud by forging someone’s signature. Unlike artwork, when someone’s identity is stolen, the person who has taken the identity has the power to define how the other person is perceived. For example, catfishing online allows a person to misrepresent not only themselves but also the person’s identity that they are using to catfish with. This is because they ascribe specific values and activities to a person’s being and change how they are represented online.

Similarly, deepfakes allow people to create entirely fictional personas or take the likeness of a person and distort how they represent themselves online. Online self-representations are already augmented to some degree by the person. For instance, most individuals on Instagram present a highly curated version of themselves that is tailored specifically to garner attention and draw particular opinions.

But, when that persona is out of the person’s control, it can spur rumours that become embedded as fact due to the nature of the internet. An example is that of celebrity tabloids. Celebrities’ love lives are continually speculated about, and often these rumours are spread and cemented until the celebrity comes out themselves to deny the claims. Even then, the story has, to some degree, impacted their reputation as those tabloids will not be removed from the internet.

The importance of a person maintaining control of their online image is paramount as it ensures their autonomy and ability to consent. When deepfakes are created of an existing person, it takes control of those tenets.

Before delving further into the ethical concerns, understanding how this technology is developed may shed light on some of the issues that arise from such a technology.

The technology is derived from deep learning, a type of artificial intelligence based on neural networks. Deep neural network technologies are often composed of layers based on input/output features. It is created using two sets of algorithms known as the generator and discriminator. The former creates fake content, and the latter must determine the authenticity of the materials. Each time it is correct, it feeds information back to the generator to improve the system. In short, if it determines whether the image is real correctly, the input receives a greater weighting. Together this process is known as generative adversarial network (GAN). It uses the process to recognise patterns which can then be compiled to make fake images.

With this type of model, if the discriminator is overly sensitive, it will provide no feedback to the generator to develop improvements. If the generator provides an image that is too realistic, the discriminator can get stuck in a loop. However, in addition to the technical difficulties, there are several serious ethical concerns that it gives rise to.

Firstly, there have been concerns regarding political safety and women’s safety. Deepfake technology has advanced to the extent that it can create multiple photos compiled into a video. At first, this seemed harmless as many early adopters began using this technology in 2019 to make videos of politicians and celebrities singing along to funny videos. However, this technology has also been used to create videos of politicians saying provocative things.

Unlike, photoshop and other editing apps that require a lot of skill or time to augment images, deepfake technology is much more straightforward as it is attuned to mimicking the person’s voice and actions. Coupling the precision of the technology to develop realistic images and the vast entity that we call the internet, these videos are at risk of entering echo chambers and epistemic bubbles where people may not know that these videos are fake. Therefore, one primary concern regarding deepfake videos is that they can be used to assert or consolidate dangerous thinking.

These tools could be used to edit photos or create videos that damage a person’s online reputation, and although they may be refuted or proved as not real, the images and effects will remain. Recently, countries such as the UK have been demanding the implementation of legislation that limits deepfake technology and violence against women. Specifically, there is a slew of apps that “nudify” any individual, and they have been used predominantly against women. All that is required of users is to upload an image of a person. One version of this website gained over 35 million hits over a few days. The use of deepfake in this manner creates non-consensual pornography that can be used to manipulate women. Because of this, the UK has called for stronger criminal laws for harassment and assault. As people’s main image continues to merge with technology, the importance of regulating these types of technology is paramount to protect individuals. Parameters are increasingly pertinent as people’s reality merges with the virtual world.

However, like with any piece of technology, there are also positive uses. For example, Deepfake technology can be used in medicine and education systems by creating learning tools and can also be used as an accessibility feature within technology. In particular, the technology can recreate persons in history and can be used in gaming and the arts. In more detail, the technology can be used to render fake patients whose data can be used in research. This protects patient information and autonomy while still providing researchers with relevant data. Further, deepfake tech has been used in marketing to help small businesses promote their products by partnering them with celebrities.

Deepfake technology was used by academics but popularised by online forums. Not used to benefit people initially, it was first used to visualise how certain celebrities would look in compromising positions. The actual benefits derived from deepfake technology were only conceptualised by different tech groups after the basis for the technology had been developed.

The conception of such technology often comes to fruition due to a developer’s will and, given the lack of regulation, is often implemented online.

While there are extensive benefits to such technology, there need to be stricter regulations, and people who abuse the scope of technology ought to be held accountable. As we see our present reality merge with virtual spaces, a person’s online presence will continue to grow in importance. Stronger regulations must be put into place to protect people’s online persona.

While users should be held accountable for manipulating and stripping away the autonomy of individuals by using their likeness, more specifically, developers must be held responsible for using their knowledge to develop an app using deepfake technology that actively harms.

To avoid a fallout like Knoedler, where distrust, skepticism, and hesitancy rooted itself in the art community, we must alert individuals when deepfake technology is employed; even in cases where the use is positive, be transparent that it has been used. Some websites teach users how to differentiate between real and fake, and some that process images to determine their validity.

Overall, this technology can help individuals gain agency; however, it can also limit another persons’ right to autonomy and privacy. This type of AI brings unique awareness to the need for balance in technology.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

BY Mehhma Malhi

Mehhma recently graduated from NYU having majored in Philosophy and minoring in Politics, Bioethics, and Art. She is now continuing her study at Columbia University and pursuing a Masters of Science in Bioethics. She is interested in refocusing the news to discuss why and how people form their personal opinions.

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 27 OCT 2021

Francesca Minerva is a contemporary bioethicist whose work largely includes medical ethics, technological ethics, discrimination and academic freedom.

A research Fellow at the University of Milan and the co-founder and co-editor of the Journal of Controversial Ideas, Francesca Minerva has published extensively within the field of applied ethics on topics such as cryonics, academic freedom, conscientious objection, and lookism. But she is best (if somewhat reluctantly) known for her work on the topic of abortion.

Controversy over ‘After-birth Abortion’

In 2012, Minerva and Alberto Giubilini wrote a paper entitled ‘After-birth Abortion: why should the baby live?’ The paper discussed the moral status of foetuses and newborn babies and argued that after-birth abortion (more commonly known as infanticide) should be permissible in all situations where abortion is permissible.

In the parts of the world where it is legal, abortion may be requested for a number of reasons, some having to do with the mother’s well-being (e.g., if the pregnancy poses a risk to her health, or causes emotional or financial stress), others having to do with the foetus itself (e.g., if the foetus is identified as having a chromosomal or developmental abnormality).

Minerva and Giubilini argue that if it’s permissible to abort a foetus for one of these reasons, then it should also be permissible to “abort” (i.e., euthanise) a newborn for one of these reasons.

This is because they argue that foetuses and newborns have the same moral status: Neither foetuses nor newborns are “persons” capable of attributing (even) basic value to their life such that being deprived of this life would cause them harm.

This is not an entirely original argument. Minerva and Giubilini were mainly elaborating on points made decades ago by Peter Singer, Michael Tooley and Jeff McMahan. And yet, ‘After-birth Abortion’ drew the attention of newspapers, blogs and social media users all over the world and Minerva and Giubilini quickly found themselves at the centre of a media storm.

In the months following the publication, they received hundreds of angry emails from the public, including a number of death threats.

The controversy also impacted their careers: Giubilini had a job offer rescinded and Minerva was not offered a permanent job in a philosophy department because members of the department “were strongly opposed to the views expressed in the paper”. Also, since most of the threatening emails were sent from the USA, they were advised not to travel to the USA for at least a year, meaning that they could not attend or speak at academic conferences being held there during that period.

So why did ‘After-birth Abortion’ attract so much attention compared to older publications on the same topic? While the subject matter is undoubtedly controversial, Minerva believes the circulation of the paper had more to do with the internet than with the paper itself.

Academic Freedom and the Journal of Controversial Ideas

“The Web has changed the way ideas circulate.” Ideas spread more quickly and reach a much wider audience than they used to. There is also no way to ensure that these ideas are reported correctly, particularly when they are picked up by blogs or discussed on social media. As a result, ideas may be distorted or sensationalised, and the original intent or reasoning behind the idea may be lost.

Minerva is particularly concerned about the impact that this may have on research, believing that fear of a media frenzy may discourage some academics from working on topics that could be seen as controversial. She believes that, in this way, the internet and mass media may pose a threat to academic freedom.

“Research is, among many other things, about challenging common sense, testing the soundness of ideas that are widely accepted as part of received wisdom, or because they are held by the majority of people, or by people in power. The proper task of an academic is to strive to be free and unbiased, and we must eliminate pressures that impede this.”

In an effort to eliminate some of this pressure, Minerva co-founded the Journal of Controversial Ideas, alongside Peter Singer and Jeff McMahan. As the name suggests, the journal encourages submissions on controversial topics, but allows authors to publish under a pseudonym should they wish to.

The hope is that by allowing authors to publish under a false name, academics will be empowered to explore all kinds of ideas without fearing for their well-being or their career. But ultimately, as Minerva says, “society will benefit from the lively debate and freedom in academia, which is one of the main incubators of discoveries, innovations and interesting research.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Climate + Environment

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The Ethics of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF)

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

Big thinkerScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 18 AUG 2021

We’re all familiar with the Einsteins and Hawkings of history, but there are many who have influenced the direction and development of science. Here are seven scientists and philosophers who have shaped how science is practiced today.

Tim Berners-Lee

Sir Timothy Berners-Lee (1955-present) is an English computer scientist. Most notably, he is the inventor of the World Wide Web and the first web browser. If not for his innovative insight and altruistic intent (he gave away the idea for free!), the way you’re viewing this very page may have been completely different. These days, Berners-Lee is fighting to save his vision. The Web has transformed, he says, and is being abused in ways he always feared – from political interference to social control. The only way forward is pushing for ethical design and pushing back against web monopolisation.

Legacy: The World Wide Web as we know it.

Jane Goodall

Dame Jane Goodall (1934-present) is an English primatologist and anthropologist. Over 60 years ago, Goodall entered the forest of Gombe Stream National Park and made the ground-breaking discovery that chimpanzees make and use tools and exhibit other human-like behaviour, including armed conflict. Since then, she has spent decades continuing her extensive and hands-on research with chimpanzees, written a plethora of books, founded the Jane Goodall Institute to scale up conservation efforts, and is forever changing the way humans relate to animals.

Legacy: “Only if we understand, will we care. Only if we care, will we help. Only if we help, shall all be saved.”

Karl Popper

Sir Karl Popper (1902-1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. He is best known as one of the greatest philosophers of science in the twentieth century, having contributed a new and novel way of thinking about the methodology of science. Against the prevailing empiricist idea that rationally acceptable beliefs can only be justified through direct experience, Popper proposed the opposite. In fact, Popper argued, theories can never be proven to be true. The best we can do as humans is ensure that they are able to be false and continue testing them for exceptions, even as we use these assumptions to further our knowledge. One of Popper’s most enduring thoughts is that we should rationally prefer the simplest theory that explains the relevant facts.

Legacy: The idea that to be scientific is to be fallible.

Marie Curie

Marie Curie (1867-1934) was a Polish-French physicist and chemist. She was a pioneer of radioactivity research, coining the term with her husband, and discovered and named the new elements “polonium” and “radium”. During the course of her extensive career, she was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize, and the first to be awarded two Nobel Prizes in two scientific fields: physics and chemistry. Due to the underfunded research conditions of time and ignorance about the danger of radiation exposure, it’s thought that a large factor in her death was radiation sickness.

Legacy: Discovering polonium and radium, pioneering research into the use of radiation in medicine and fundamentally changing our understanding of radioactivity.

René Descartes

René Descartes (1596-1650) was a French philosopher, mathematician and scientist. Descartes is most widely known for his philosophy – including the famous “I think, therefore I am” – but he was also an influential mathematician and scientist. Descartes’ possibly most enduring legacy is something high school students are very familiar with today – coordinate geometry. Also known as analytic or Cartesian geometry, this is the use of algebra and a coordinates graph with x and y axes to find unknown measurements. Descartes was also interested in physics, and it is thought that he had great influence on the direction that a young Isaac Newton took with his research – Newton’s laws of motion were eventually modelled after Descartes’ three laws of motion, outlined in Principles of Philosophy. In his essay on optics, he independently discovered the law of reflection – the mathematical explanation of the angle at which light waves are reflected.

Legacy: “The seeker after truth must, once in the course of his life, doubt everything, as far as is possible.”

Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958) was an English chemist and X-ray crystallographer who is most famous for her posthumous recognition. During her life, including in her PhD thesis, she researched the properties and utility of coal, and the structure of various viruses. She is now often referred to as “the forgotten heroine” for the lack of recognition she received for her contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA. Even one of the recipients of the Nobel Prize for the discovery of the DNA double helix suggested that Franklin should have been among the recipients, but posthumous nominations were very rare. Unfortunately, this was not her only posthumous brush with a Nobel Prize, either. One day before she and her team member were to unveil the structure of a new virus affecting tobacco farms, Franklin died of ovarian cancer. Over two decades later, her team member went on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the continued research on the virus. Since her death, she has been recognised with over 50 varying awards and honours.

Legacy: Foundational research that informed the discovery of the structure of DNA, coal and graphite.

Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky (1928-present) is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist and social/political critic. While Chomsky may be better known as a political dissident and social critic, he also played a foundational role in the development of modern linguistics and founded a new field: cognitive science, the scientific study of the mind. Chomsky’s research and criticism of behaviourism saw the decline in behaviourist psychology, and his interdisciplinary work in linguistics and cognitive science has gone on to influence advancements in a variety of fields including computer science, immunology and music theory.

Legacy: Establishing cognitive science as a formal scientific field and inciting the fall of behaviourism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Is it ok to use data for good?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

5 dangerous ideas: Talking dirty politics, disruptive behaviour and death

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we shouldn’t be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Who's to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 25 FEB 2021

News will soon return to Facebook, with the social media giant coming to an agreement with the Australian government. The deal means Facebook won’t be immediately subject to the News Media Bargaining Code, so long as it can strike enough private deals with media companies.

Facebook now has two months to mediate before the government gets involved in arbitration. Most notably, Facebook have held onto their right to strip news from the platform to avoid being forced into a negotiation.

Within a few days, your feed will return to normal, though media companies will soon be getting a better share of the profits. It would be easy to put this whole episode behind us, but there are some things that are worth dwelling on – especially if you don’t work in the media, or at a social platform but are, like most of us, a regular citizen and consumer of news. Because when we look closely at how this whole scenario came about, it’s because we’ve largely been forgotten in the process.

Announcing Facebook’s sudden ban on Australian news content last week, William Easton, Managing Director of Facebook Australia & New Zealand wrote a blog post outlining the companies’ reasons. Whilst he made a number of arguments (and you should read them for yourself), one of the stronger claims he makes is that Facebook, unlike Google Search, does not show any content that the publishers did not voluntarily put there. He writes:

“We understand many will ask why the platforms may respond differently. The answer is because our platforms have fundamentally different relationships with news. Google Search is inextricably intertwined with news and publishers do not voluntarily provide their content. On the other hand, publishers willingly choose to post news on Facebook, as it allows them to sell more subscriptions, grow their audiences and increase advertising revenue.”

The crux of the argument is this. Simply by existing online, a news story can be surfaced by Google Search. And when it is surfaced, a whole bunch of Google tools – previews, summaries from Google Home, one-line snippets and headlines – give you a watered-down version of the news article you search for. They give you the bare minimum info in an often-helpful way, but that means you never click the site or read the story, which means no advertising revenue or way of knowing the article was actually read.

But Facebook is different – at least, according to Facebook. Unless news media upload their stories to Facebook, which they do by choice, users won’t see news content on Facebook. And for this reason, treating Facebook and Google as analogous seems unfair.

Now, Facebook’s claims aren’t strictly true – until last week, we could see headlines, a preview of the article and an image from a news story posted on Facebook regardless of who posted it there. And that headline, image and snippet are free content for Facebook. That’s more or less the same as what Facebook says Google do: repurposing news content that can be viewed without ever having to leave the platform.

However, these link previews are nowhere near as comprehensive as what Google Search does to serve up their own version of news stories for the company’s own purpose and profit. Most of the news content you see on Facebook is there because it was uploaded there by media companies – who often design video or visual content explicitly to be uploaded to Facebook and to reach their audience.

However, on a deeper level, there seem to be more similarities between Google and Facebook than the latter wants to admit, because the size and audience base Facebook possesses makes it more-or-less essential for media organisations to have a presence there. In a sense, the decision to have a strategy on Facebook is ‘voluntary’, but it’s voluntary in the same way that it’s voluntary for people to own an attention-guzzling, data sucking smartphone. We might not like living with it, but we can’t afford to live without it. Like inviting your boss to your wedding, it’s voluntary, but only because the other options are worse.

Facebook would likely claim innocence of this. Can they really be blamed for having such an engaging, effective platform? If news publishers feel obligated to use Facebook or fall behind their competitors that’s not something Facebook should feel bad about or be punished for. If, as Facebook argue, publishers use them because they get huge value from doing so, it does seem genuinely voluntary – desirable, even.

Even if this is true, there are two complications here. First, if news media are seriously reliant on Facebook, it’s because Facebook deliberately cultivated that. For example, five years ago Facebook was a leading voice behind the ‘pivot to video’, where publishers started to invest heavily in developing video content. Many news outlets drastically reduced writing staff and investment in the written word, instead focussing on visual content.

Three years later, we learned that Facebook had totally overstated the value of video – the pivot to video, which served Facebook’s interests, was based on a self-serving deception. This isn’t the stuff of voluntary, consensual relationships.

Let’s give Facebook a little benefit of the doubt though. Let’s say they didn’t deliberately cultivate the media’s reliance on their platform. Still, it doesn’t follow obviously from this that they have no responsibility to the media for that reliance. Responsibility doesn’t always come with a sign-up sheet, as technology companies should know all too well.

French theorist Paul Virilio wrote that “When you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck; when you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash; and when you invent electricity, you invent electrocution.” Whilst Virilio had in mind technology’s dualistic nature, modern work in the ethics of technology invites us to interpret this another way.

If inventing a ship also invents shipwrecks, it might be up to you to find ways to stop people from drowning.

Technology companies – Facebook included – have wrung many a hand talking about the ‘unintended consequences’ of their design and accepting responsibility for them. In fact, speaking before a US Congress Committee, Mark Zuckerberg himself conceded as much, saying:

“It’s clear now that we didn’t do enough to prevent these tools from being used for harm, as well. And that goes for fake news, for foreign interference in elections, and hate speech, as well as developers and data privacy. We didn’t take a broad enough view of our responsibility, and that was a big mistake. And it was my mistake. And I’m sorry. I started Facebook, I run it, and I’m responsible for what happens here.”

It seems unclear why Facebook recognised their responsibility in one case, but seem to be denying it in another. Perhaps the news media are not reliant – or used by – Facebook in the same way as they are Google, but it’s not clear this goes far enough to free Facebook of responsibility.

At the same time, we should not go too far the other way, denying the news media any role in the current situation. The emergence of Facebook as a lucrative platform seems to have led the media to a Faustian pact – selling their soul for clicks, profit and longevity. In 2021 it seems tired to talk about how the media’s approach to news – demanding virality, speed, shareability – are a direct result of their reliance on platforms like Facebook.

The fourth estate – whose work relies on them serving the public interest – adopted a technological platform and in so doing, adopted its values as their own: values that served their own interests and those of Facebook rather than ours. For the media to now lament Facebook’s decision as anti-democratic denies the media’s own blameworthiness for what we’re witnessing.

But the big reveal is this: we can sketch out all the reasons why Facebook or the media might have the more reasonable claim here, or why they share responsibility for what went down, but in doing so, we miss the point. This shouldn’t be thought of as a beef between two industries, each of whom has good reasons to defend their patch.

What needs to be defended is us: the community whose functioning and flourishing depends on these groups figuring themselves out.

Facebook, like the other tech giants, have an extraordinary level of power and influence. So too do the media. Typically, we don’t to allow institutions to hold that kind of power without expecting something in return: a contribution to the common good. This understanding – that powerful institutions hold their power with the permission of a community they deliver value to – is known as a social license.

Unfortunately, Facebook have managed to accrue their power without needing a social license. All power, no permission.

This is in contrast to the news media, whose powers aren’t just determined by their users and market share, but by the special role we afford them in our democracy, the trust and status we afford their work isn’t a freebie: it needs to be earned. And the way it’s earned is by using that power in the interests of the community – ensuring we’re well-informed and able to make the decisions citizens need to make.

The media – now in a position to bargain with Facebook – have a choice to make. They can choose to negotiate in ways that make the most business sense for them, or they can choose to think about what arrangements will best serve the democracy that they, as the ‘fourth estate’, are meant to defend. However, at the very least they know that the latter is expected of them – even if the track record of many news publishers gives us reason to doubt.

Unfortunately, they’re negotiating with a company whose only logic is that of a private company. Facebook have enormous power, but unlike the media, they don’t have analogous mechanisms – formal or informal – to ensure they serve the community. And it’s not clear they need it to survive. Their product is ubiquitous, potentially addictive and – at least on the surface – free. They don’t need to be trusted because what they’re selling is so desirable.

This generates an ethical asymmetry. Facebook seem to have a different set of rules to the media. Imagine, for a moment, if the media chose to stop reporting for a fortnight to protest a new law. The rightful outrage we would feel as a community would be palpable. It would be nearly unforgivable. And yet we do not hold Facebook to the same standards. And yet, perhaps at this point, they’ve made themselves almost as influential.

There’s a lot that needs to happen to steady the ship – and one of the most frustrating things about it is that as individuals, there isn’t a lot we can do. But what we can do is use the actual license we have with Facebook in place of a social license.

If we don’t like the way a news organisation conducts themselves, we cancel our subscriptions; we change the channel. If you want to help hold technology companies to account, you need to let your account to the talking. Denying your data is the best weapon you’ve got. It might be time to think about using it – and if not, under what circumstances you might.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

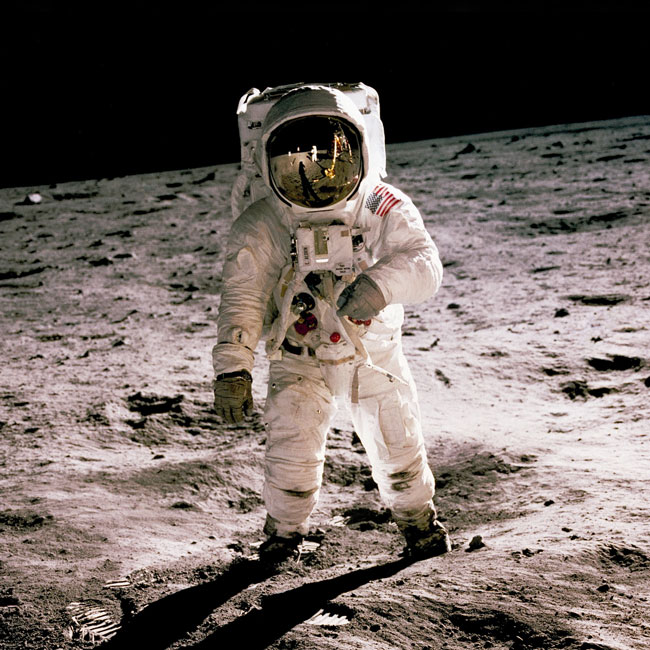

One giant leap for man, one step back for everyone else: Why space exploration must be inclusive

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Why the EU’s ‘Right to an explanation’ is big news for AI and ethics

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Space: the final ethical frontier

Space: the final ethical frontier

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 24 SEP 2020

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant once famously said “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and the more steadily we reflect on them: the starry heavens above and the moral law within.”

It probably didn’t occur to Kant that there would come a day when the moral law and the starry heavens would find themselves in a staring contest with one another. In fairness though, it’s been almost 250 years since he wrote that quote. Today, those starry heavens play an increasingly important role in human affairs. And wherever there are people making decisions, ethical issues are sure to follow.

To get to know this final ethical frontier, I had a chat with Dr Nikki Coleman, Senior Chaplain Ethicist with the Australian Air Force. Nikki is a bona fide space ethicist to help us get up to (hyper) speed with all the new issues around ethics in space.

Is space an environment?

One of the largest contributions of the field of environmental ethics has been to encourage people to consider the environment as having value independent of its usefulness to humans. Before environmental ethics emerged as a field, many indigenous cultures and religions had already embedded these beliefs in the way they lived and related to land.

“The idea of space is that it’s a ‘global commons’,” says Coleman. “It belongs to all of us on the planet, but also to future generations. We can’t just dump space debris. We have to be careful about how we utilise resources. Like the resources on Earth, these resources are finite. They don’t go on forever,” she says.

This echoes one of the most common arguments about preservation and sustainability. We take care of the planet not just for ourselves, but for future generations. The challenge is helping people to understand that custodianship of space means thinking about the long tail on the decisions we make now. In fact, it might be even more difficult when it comes to space because, well, space is big, and it’s a long way away and we’ll likely never go there ourselves.

“What happens in space is the same as what happens on Earth, but it’s more remote,” Coleman tells me. And yet, despite this, what happens in space affects us profoundly. Just as we rely on trees, ecosystems and other aspects of the natural environment, we are reliant on parts of space as well. “Even though these objects feel further away from us, we still have an interdependency and a relationship with space,” explains Coleman.

What role should private companies play?