Why are people stalking the real life humans behind ‘Baby Reindeer’?

Why are people stalking the real life humans behind ‘Baby Reindeer’?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 30 APR 2024

Baby Reindeer, the new Netflix miniseries based on a true story, opens with a simple act of kindness — Donny Dunn (Richard Gadd), a wannabe stand-up comedian, gives a customer a free cup of tea.

“I felt sorry for her,” Donny tells us in voiceover, as Martha (Jessica Gunning) wanders into the pub where he works. It is an action he will soon regret.

The two begin conversing; as they do, Martha becomes increasingly obsessed with the comedian. Simple affection morphs into something obsessive and painful – Martha begins bombarding Donny with texts and emails. Quickly, it becomes clear: Martha is a stalker, and Donny is her victim.

That’s not exactly a new story to be told onscreen. Fatal Attraction, The Hand That Rocks The Cradle, and When A Stranger Calls have all dealt with the significant fear and anxiety that being stalked can create – when you’re the victim of a stalker, you live on a constant knife’s edge, forever expecting the next email, the next escalation. These films capture that tension.

But what Baby Reindeer does additionally is depict – in a surprisingly complex way – the blend of emotions a victim can feel towards their stalker, not all of them strictly negative. And more than that, it explores the difficult histories that can make a stalking victim vulnerable to being harassed in the first place.

Which is why it is fascinating – and troubling – that such a complicated, nuanced show has led some viewers to begin replicating Martha’s behaviour to find the real people behind the story.

The complexity of the stalker/victim relationship

Stalking is, as philosopher Elizabeth Brake notes, composed of actions “which would normally be permissible; indeed, many stalking behaviors are protected liberties.” That makes it a complicated form of ethical wrong, one many stalkers take advantage of. There’s nothing bad about sending an email. There’s not even anything wrong with sending many emails – under specific circumstances. What makes stalking terrifying is the amount of communication, and, often, its intent.

Additionally, some stalkers are themselves dealing with trauma, or have been victims of a serious harm. This is what Baby Reindeer captures – Martha is harming Donny, but she herself has been harmed. More than that, Donny’s traumatic past – he is the victim of sexual assault – makes him open to her affection initially. These are two people who have suffered, and are continuing to suffer. They find each other, amidst the chaos of traumatic flashbacks, and a deep sense of purposelessness.

Perhaps if things were different, they might have become friends. After all, they are not so dissimilar, in some ways: Baby Reindeer ends with Donny finding himself in the exact position Martha was in when he first encountered her, relying on the random kindness of a bartender.

In this way, Baby Reindeer does not condemn Martha. Nor does it condemn Donny, even though they have both made mistakes. Instead, it sees their actions as deeply tied to past harms, a continuation of the cycle of abuse.

And a cycle that some viewers of the show are perpetuating.

Viewer as stalker

Since Baby Reindeer became a smash hit, some viewers have begun attempting to track down the real humans that inspired the show. As The Guardian notes, “online sleuths” (those are the article’s words), believe they’ve found the real-life Martha. But so obsessive and dangerous has been the search, that innocent people have been caught up in the fray – one man was mistakenly believed to be the television writer who assaulted Donny, and received death threats as a result.

But whether or not the “right” targets have been uncovered and attacked, such a response to the show is deeply unethical. Baby Reindeer itself doesn’t want to demonise Martha – so why are some viewers doing that themselves? Baby Reindeer is a cautionary story about letting passion overcome reason, and trying to track down people who don’t want to be tracked down. That stalking is being perpetuated in its name is a deep ethical wrong.

It’s also a common ethical issue in our modern age. Increasingly, online vigilantes – better to call them that than “sleuths” – have come to behave in a way that shows they believe under certain circumstances, normal ethical rules are waved away. Think of the targeted harassment that was directed towards the real people that stans assumed Ariana Grande’s or Taylor Swift’s new records were about. Or Beyonce’s ‘Beyhive’ hounding a women off social media. In all of these cases, the abuse was “justified” in the mind of the perpetrators. They believed an ethical crime had been committed, and so gave themselves free rein to punish right back.

So it goes in the case of Baby Reindeer. Martha wronged Donny; the TV writer assaulted him. In an increasingly punitive, carceral and old-school digital world, viewers are taking it on themselves to dole out their own justice, in order to reset wrongs.

In actual fact, they are not moral arbiters. They are committing a wrong themselves. And it is a wrong that we must call out.

Baby Reindeer urges us to consider human beings as complex – not deserving of punishment, but of understanding, even if we condemn their actions.

We can want someone to be far away from us, given the harms they have committed. But we must attempt to collectively return to a place where retributive justice – so often confused as “activism” – does not cloud our understanding of complexity. After all, as that final scene of Baby Reindeer shows, we could all find ourselves in Martha’s shoes.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

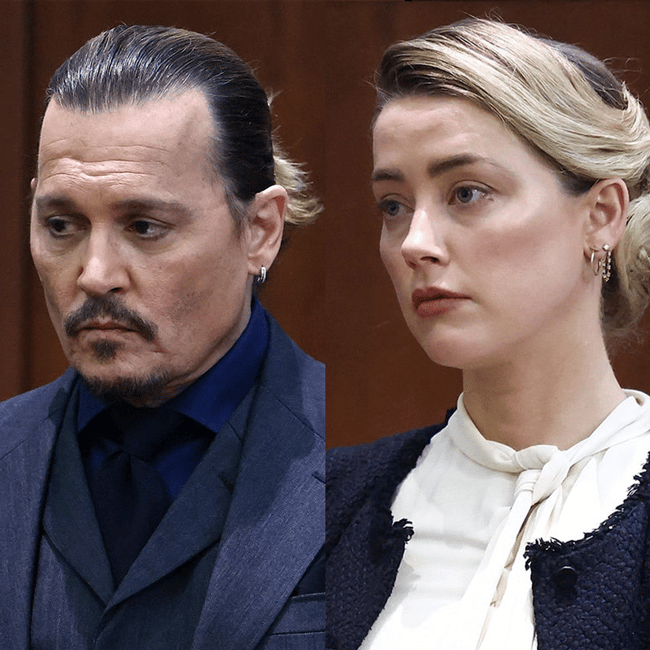

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Why Anzac Day’s soft power is so important to social cohesion

Why Anzac Day’s soft power is so important to social cohesion

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 25 APR 2024

Any country wishing to advance or defend its strategic interests has recourse to two types of power: hard and soft.

Richard Marles’ release of the government’s most recent Defence Strategic Review, coming as it does just before Anzac Day, provides an opportunity to examine how well Australia is positioned in relation to the oft-neglected “defensive” aspect of soft power.

Any potential adversary knows that a low-risk way to wound a diverse, multicultural society is to pick it apart until it turns against itself. They are right. Look at the cracks that have opened up at home under the strain of a distant war between the state of Israel and Hamas. It has led to a massive rise in antisemitism and a resurgence in Islamophobia.

Indeed, the first thought of many was that the murderous rampage at Bondi Junction was a terrorist attack connected to conflict in the Middle East. Two days later, a surge of communal violence was unleashed in response to the wounding of two clerics in a terrorist incident.

Thanks to good management by police, politicians and community leaders, our worst fears were not realised. However, we should be warned. Malicious actors will have been encouraged by evidence of how easy it would be to ignite the tinder of a larger conflagration. They will be readying themselves to stoke the embers with their weapons of choice: misinformation and disinformation. How can we defend against this?

There are two aspects of soft power in its defensive form that we must deploy now to build resilience for the future. First, we must work to restore trust in our private and public institutions. Second, we need to harness the power of unifying narratives.

The first of these tasks is essential if we are to protect ourselves against the corrosive effects of misinformation and disinformation. Our current approach mostly relies on regulation and surveillance to control the worst of it.

However, a liberal democracy with a commitment to free speech will always fight with the equivalent of one hand tied behind its back. So, we need to work twice as hard; investing in the development of individuals and institutions who can be trusted to offer sound guidance at times when it really matters.

Trustworthiness needs constant effort

When natural disasters strike, we all tend to look to the ABC for critical information – even those who are concerned about the national broadcaster and its editorial stance. Trust in our public institutions should not be the exception. It needs to become the norm. This will happen only if those institutions are consistently trustworthy.

Becoming trustworthy is an acquired skill. It needs constant effort. Trustworthiness is not something that can be produced by anti-corruption commissions, by regulation or surveillance. It requires investment in a positive commitment to ethics.

As a public, we need to know that our leaders merit our trust at times when it really matters. No matter what those dedicated to sowing the seeds of dissension might tell us, no matter what conspiracy theories might be abroad, we need good reason to believe that when it comes to the crunch, our leaders have the knowledge, skills and character to be relied on. In short, we need to invest in the nation’s “ethical infrastructure”.

Second, we need to make far more of our “secular myths”. Like all such stories, their power resides in something larger than the immediate facts. They speak to something deeper – which brings me to Anzac Day. Many nations ground their identity in stories of triumph, whether it be the defeat of an armed foe or the overthrow of an illegitimate or oppressive regime. Anzac Day offers something different.

Those of us who celebrate Anzac Day not only remember the fallen. We also find meaning in a striking example of “noble failure”.

To try your best. To venture all, even if you fail. To maintain honour, even to the end. These are ideals to which anyone can aspire – even if, in reality, we so often fall short.

This ideal is not bound by religion, culture, language or heritage. About 70 First Nations people fought at Gallipoli. The Turks, who won the engagement, still honour what took place – despite the horrors of war. People of all faiths and none have found moments of inspiration in a story that does not glorify war – only the spirit of those “warriors” who try to be and to do their best, even when they fail.

Of course, this is just one narrative. How many others are out there waiting to be deployed for the common good?

We spend billions of dollars on the implements of hard power. But on Anzac Day we should remember its complement – the soft power of a shared ethos that underpins a cohesive society and safety at home.

This article was originally published in The Australian Financial Review.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Politics + Human Rights

How to find moral clarity in Gaza

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Rawls

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 22 APR 2024

If you’re looking to start investing in the stock market (and you’ve stumbled across this article), chances are you might be investigating how you can do it ethically – without supporting companies that are actively causing harm to the world.

“Ethical investing” has no fixed definition in Australia, Life and Shares host Cris Parker points out in The Ethics Centre’s latest podcast. Susheela Peres Da Costa, Chair of the Responsible Investment Association of Australasia (RIAA), says typically ethical, or responsible, investing is about, “consumers assuming something is screened out of the portfolio – what you don’t invest in is a typical ethical investment question.”

But finding out which companies are involved in activities you don’t want to financially support is not as cut and dried as you might hope.

“There’s a lot of seductively simple solutions out there,” Peres Da Costa says, such as points-based system ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance Investing).

“Some of the most profitable companies involved in some of the most harmful activities actually do very well on some of the scoring systems,” Da Costa says, “because they’ve got great volunteering programs and programs for replacing their light bulbs with LEDs, and they give a lot of money to charity. But investors need to be smart about not falling for the gloss. As someone who’s professionally analysed company reports, I would never, ever believe anything in a value statement…”

“However, we really need to address the elephant in the room, which is actually the cost. It is just so expensive to obtain proper financial advice – to give you an example, the median price in Australia is $5,000 per year.”

Even if you don’t think of yourself as being in the stock market, if you have super in Australia, then your super fund is investing your money on your behalf. Happily, many super funds offer investment packages classified as “sustainable”, which aim to buy into clean and renewable energy shares and avoid companies involved in fossil fuels.

The RIAA ranks Australian super funds on their responsible investment approaches: its Responsible Investment Super Studies highlight funds that choose shares in companies that aim to do good for people and the earth and screen out those with poor or questionable practices.

Still, the waters are murky as to which companies are doing the most harm, and which are trying to do good. As Life and Shares host Cris Parker points out, one of the best performing sustainable exchange traded funds in the past year had a large holding in mining company BHP.

But that’s not necessarily a bad thing, says Da Costa. “It’s easy to think about mining companies as those that dig up the ground, tear down the trees and all those things. But they’re also the ones that are producing the lithium, for example, and all the rare earths that we need to transition from our dependence on fossil fuels. So I think one of the things you have to be really careful of is assuming that a company is one thing, good or bad.”

“One of the things you have to be really careful of is assuming that a company is one thing, good or bad.” – Peres Da Costa

Of course, there’s no legislation to prevent you from investing in whatever you want – and if you don’t buy shares in a particular company, someone else probably will. Unless you have the financial power to buy a controlling stake, you won’t be able to control board decisions as a shareholder. But it doesn’t mean you can’t try.

“If your objective is to have an impact in the world, then the levers that you have available to you are very different if you’re a consumer versus an institution, and you need to have a theory of change about how you have that impact,” Da Costa says.

A theory of change is a conceptual model outlining the specific actions and interventions your investments will use to achieve the desired impact. In the case of sustainability and climate change, this means putting your money into renewables, divesting from fossil fuel companies, and being an active shareholder – paying attention to what your invested companies are doing, and wielding your shareholder voting power at AGMs (Annual General Meetings).

One simple action that should be on every good global citizen’s to-do list is checking your super fund’s ethical position and investments, along with checking where your bank invests and if your power company uses renewables or coal and gas.

Looking to your own values and ethics, and using those as a guide to what you will and won’t invest in, is probably your best personal guide for how to invest ethically.

For instance, does it bother you to earn dividends from companies involved in mining and fossil fuels, weapons manufacturing, supply chains that aren’t signatories to sustainability or anti-slavery regulation, and alcohol, tobacco, or unethical pharmaceutical companies? Are you willing to make trade-offs and invest in a company doing harm in one area but good in another? As Da Costa says, you can’t assume “a company is one thing, good or bad.”

Whether you’re actively trading shares and avidly following financial news or just tinkering with your super investment options, the stock market will always be an ethical minefield. But with research and the knowledge of how to take control of your money and how it’s used, you can start investing more responsibly and purposefully.

Life and Shares unpicks the share market so you can make decisions you’ll be proud of. Listen now on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to spot an ototoxic leader

Reports

Business + Leadership

Trust, Legitimacy & the Ethical Foundations of the Market Economy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership

Political promises and the problem of ‘dirty hands’

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Blockchain: Some ethical considerations

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

On plagiarism, fairness and AI

On plagiarism, fairness and AI

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Stella Eve Pei-Fen Browne 19 APR 2024

Plagiarism is bad. This, of course, is by no means a groundbreaking or controversial statement, and seems far from a problem that is “being overlooked today”.

It is generally accepted that the theft of intellectual property is immoral. However, it also seems near impossible for one to produce anything truly original. Any word that one speaks is a word that has already been spoken. Even if you are to construct a “new” word, it is merely a portmanteau of sounds that have already been used before. Artwork is influenced by the works before it, scientific discoveries rely on the acceptance of discoveries that came before them.

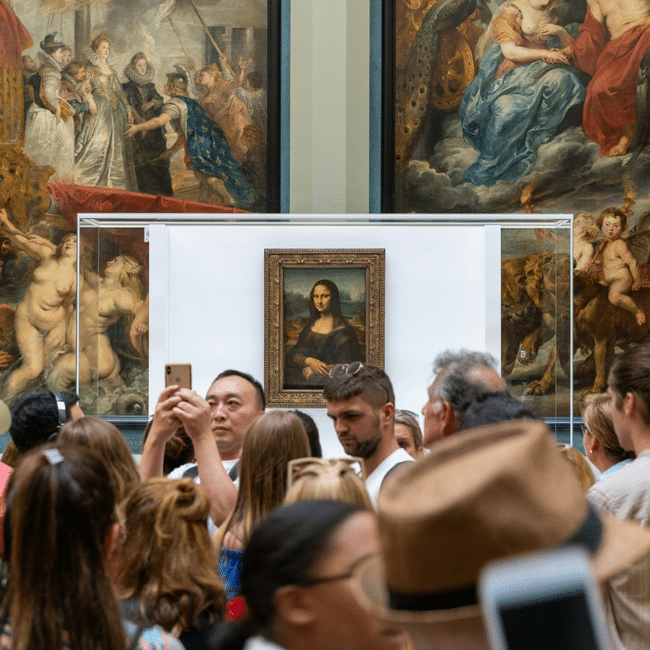

That being said, it is impractical to not differentiate between “homages”, “works influenced by previous works”, and “plagiarism”. If I was to view the Mona Lisa, and was inspired by it to paint an otherwise completely unrelated painting with the exact same colour palette, and called the work my own, there is – or at least, seems to be – something that makes this different from if I was to trace the Mona Lisa and then call it my own work.

So how do we draw the line between what is plagiarism and what isn’t? Is this essay itself merely a work of plagiarism? In borrowing the philosopher Kierkegaard’s name and arguments – which I haven’t done yet but shall do further on – I give my words credibility, relying on the authority of a great philosopher to prove my point. Really, the sparse references to his work are practically word-for-word copies of his writing with not much added to them. How many references does it take for a piece to become plagiarism?

In the modern world, what it means to be a plagiarist is rapidly changing with the advent of AI. Many schools, workplaces, and competitions frown upon the use of AI; indeed, the terms of this very essay-writing contest forbid its use.

Many institutions condemn the use of AI on the basis that it is lazy or unfair. The argument is as follows (though, it must be acknowledged that this is by no means the logic used by all institutions):

- It is good to encourage and reward those who put consistent effort into their work

- AI allows people to achieve results as good as others with minimal effort

- This is unfair to those who put effort into doing the same work

- Therefore, the use of AI should be prohibited on the grounds of its unfairness.

However, this argument is somewhat weak. Unfairness is inherent not only in academic endeavours, but in all aspects of life. For example, some people are naturally talented at certain subjects, and thus can put in less effort than others while still achieving better results. This is undeniably unfair, but there is nothing to be done about it. We cannot simply tell people to become worse at subjects they are talented at, or force others to become better.

If a talented student spends an hour writing an essay, and produces a perfectly written essay that addresses all parts of the marking criteria, whereas a student struggling with the subject spends twenty-four hours writing the same essay but produces one which is comparatively worse, would it not be more unfair to award a better mark to the worse essay merely on the basis of the effort involved in writing it?

So if it is not an issue of fairness, what exactly is wrong with using AI to do one’s work?

This is where I will bring Kierkegaard in to assist me.

Writing is a kind of art. That is, it is a medium dependent on creativity and expression. Art is, according to Kierkegaard, the finding of beauty.

The true artist is one who is able to find something worth painting, rather than one of great technical skill. A machine fundamentally cannot have a true concept of subjective “beauty”, as it does not have a sense of identity or subjective experiences.

Thus, something written by AI cannot be considered a “true” piece of writing at all.

“Subjectivity is truth” — or at least, so concludes Johannes Climacus (Kierkegaard’s pseudonym). The thing that makes this essay an original work is that I, as a human being, can say that it is my own subjective interpretation of Kierkegaard’s arguments, or it is ironic, which in itself is still in some sense stealing from Kierkegaard’s works. Either way, this writing is my own because the intentions I had while creating it were my own.

And that is what makes the work of humans worth valuing.

‘On plagiarism, fairness and AI‘ by Stella Eve Pei-Fen Browne is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Ukraine hacktivism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

BY Stella Eve Pei-Fen Browne

Stella Browne is a year 12 student at St Andrew’s Cathedral School. Her interests include philosophy, anatomy (in particular, corpus callosum morphology), surgery, and boxing. In 2021, she and a team of peers placed first in the Middle School International Ethics Olympiad.

Trying to make sense of senseless acts of violence is a natural response – but not always the best one

Trying to make sense of senseless acts of violence is a natural response – but not always the best one

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 APR 2024

Shock reverberated throughout Australia at the news of a frenzied knife attack in Sydney at Westfield Bondi Junction on 13 April — an attack that claimed the lives of six people and injured many more.

Naturally, such an event triggers a surge of news reporting and social media posts. But the news and social media conversation quickly pivoted from reporting the facts of the event to seeking answers. How could such a horrifying thing happen? What could drive someone to do something like this? Could it happen again? Could it happen near me? Am I safe?

Our minds naturally recoil from violence. But they recoil just as much from the prospect that violence can be random or senseless. We have a deep and abiding need to make sense of such horrors, to place them within a causal narrative that can help us understand how they fit in to the world around us. But in our search for a narrative, we can easily latch on to something convenient, whether or not it’s true.

Violence in search of a reason

For many people — particularly those on social media — the first narrative they turned to was terrorism. It’s not that they necessarily wanted it to be an act of terrorism. But terrorism is something that we all, sadly, understand only too well. By labelling the attack as “terrorism”, the attack ceases being random and becomes part of a system we can comprehend.

So, many people may have felt a slight sense of unease when the New South Wales police commissioner declared that it was not an act of terrorism. If not terrorism, what was it? What could possibly motivate such a horrific attack?

Then it emerged that the attacker targeted more women than men. So perhaps it was misogyny that motivated him? Perhaps he was one of these “incels” (or involuntary celibates) we sometimes hear about? But again, the details were unclear, so the speculation continued.

When the attacker’s mental health issues were revealed, that offered another way to make sense of the violence. People could draw on a well-known narrative of a broader mental health crisis across the nation. And while that might inspire greater attention and investment in mental health, it can also instil fear and suspicion of those who experience a range of conditions but pose no threat to the public, possibly leading to increased stigma or disadvantage.

And, of course, there’s the fact the attacker used a knife, which will inevitably lead to a conversation about whether we ought to regulate the sale of knives, even if that might hamper legitimate use and have done little to prevent this attack.

How to live with the uncertainty

Yet we must remember that it remains a distinct possibility this was a freak event, one that doesn’t fit into any clear causal narrative, and one that doesn’t tell us anything meaningful about whether such horrific attacks are likely to occur again in the future. It might be the case that there was little or nothing that could have been done to prevent it. Ultimately, it might just be a random and senseless act of violence, no matter how much our minds recoil from such a possibility.

It’s natural for us to seek meaning when we’re faced with apparently senseless violence, even if it can cause us to jump to conclusions or latch on to hasty solutions. What’s less natural is sitting with the uncertainty that comes with not knowing how or why this happened.

So, what to do?

First, we should forgive ourselves (and everybody else) for being human, and desperately wanting to live in a safe and predictable world. But second, we need to acknowledge that safety and predictability are often outside of our control. Even so, it doesn’t mean we are powerless. As the Stoics pointed out, we can still choose how to encounter the world, and likewise, which narratives to adopt to make sense of it.

Instead of focusing on the motivations of the attacker, which might always remain elusive, we can look to other parts of the picture, including those that reinforce our appreciation of our fellow humanity, even in the face of unspeakable tragedy. We can focus on the acts of heroism by individuals to hold back the attacker. Or on the bravery of the police officer who confronted him. Or the workers who hastened to protect the customers in their stores. Or the outpouring of support from the community to the victims and their families.

There is a strong narrative here, one that can boost our empathy for others and buttress us against tragedy, whether deliberate or random. But it might require us to allow some questions to go unanswered.

This article was originally published in ABC Religion and Ethics.

Image by Richard Milnes / Alamy

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What does Adolescence tell us about identity?

READ

Society + Culture

6 dangerous ideas from FODI 2024

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

The super loophole being exploited by the gig economy

The super loophole being exploited by the gig economy

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Nina Hendy 9 APR 2024

Imagine what it must feel like not to receive compulsory superannuation – despite it being a mandated part of our employment landscape for more than three decades. For many Australian workers this is a reality.

The Super Guarantee legislates that employers have to pay super contributions of 11 per cent of an employee’s ordinary time earnings, regardless of whether they’re a casual or full time employee.

But the legislation that is meant to protect working rights falls short for an increasingly large group of workers.

We’re referring to the gig economy, which appeared out of nowhere around 2006 when Menulog launched Australia’s first online meal delivery service and has since grown nine-fold to employ as many as 250,000 workers across platforms such as Upwork, Fiverr, Uber and Airtasker.

While the system is providing Australians with flexibility, autonomy and options for an additional source of income, its participants are also being exploited. More than half of gig workers are under 35 and a similarly a large number are international students and migrants who can struggle to get a foothold onto the career ladder in Australia – sometimes due to language or cultural setbacks. It appears nearly two decades later, the super system appears to still be playing catch-up with a changing workforce.

Despite some contractors being eligible to be paid super if they meet the additional eligibility requirements, gig economy workers miss out on the same rights as most working Australians. These workers trade basic workplace entitlements, such as sick leave and holiday pay, for flexibility, and critically, they also miss out on the Superannuation Guarantee, despite the national mandate.

Scratch the surface, and it’s clear to see that a significant loophole exists in current labour force regulations, meaning that most gig workers are likely to be classified as independent contractors.

The superannuation system was built to ensure that Australians can retire comfortably without having to rely on the Government-funded Age Pension, taking significant pressure off government coffers so that funds can be diverted into health, education and other critical infrastructures.

Quite simply, it’s a crime not to pay super. The Australian Taxation Office clamps down on employers that don’t pay superannuation in full, or who fail to keep adequate records. The system works well, and is under constant review as reforms continue to make improvements solely aimed at growing our retirement nest egg.

But despite the removal of the $450 threshold so that workers earning even a small amount from an employer in a month are still eligible for super, the legislation hasn’t yet caught up with the gig economy, creating a deep chasm between the haves, and the have nots.

This is because most gig workers are paid per job, and not as part of a company’s payroll. In the eyes of the Australian Taxation Office, these workers are considered self-employed, or sole traders. As such, any super they put aside for themselves is a choice, rather than a legal requirement.

As a result, gig workers risk falling well short of the super they should have accrued during their working life, bringing about longer term concerns around financial security. For example, if someone worked in the industry for a decade, their super balance upon retirement would dip to $92,000 less than a minimum wage employee. Consequently, gig economy workers are more likely to rely solely on the government-funded Age Pension in retirement.

This disparity raises questions about current superannuation legislation, which doesn’t go far enough to provide protections for all workers.

While Industry Super chief Bernie Dean has made public calls for gig workers to be paid super so they can be self-sufficient in retirement, it has so far fallen on deaf ears.

Fair Work Legislation sets out to close loopholes by creating minimum standards for all workers and proposes a new definition of casual employment, but until all workers earn the same rate of super regardless of how they are employed, it doesn’t look to be all that fair.

So what is our responsibility to those caught in the gap?

Long term disparities about who is and isn’t entitled to Super raises serious questions about inequities in the system and how we consider all types of workers as part of our community and the economy.

While real change comes with policy and regulation, workers do bear some responsibility to prevent inequity falling on them. With many workers in the industry lacking practical information about their rights, education is paramount. Users of the gig economy should seek to better understand industry rules and their options, which starts by asking the right questions: What protections do I have by taking on this job? What are the risks involved? Am I setting up the right fund for myself? And how can I best think about my future self?

And in the meantime, the law might just catch up with consideration for all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Women’s pain in pregnancy and beyond is often minimised

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Do organisations and employees have to value the same things?

BY Nina Hendy

Nina Hendy is an Australian business & finance journalist writing for The Financial Review, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and The New Daily.

True crime media: An ethical dilemma

In the realm of media and entertainment, the insatiable public appetite for gripping, real-life narratives has propelled the rise of one particular genre; true crime.

From podcasts and movies to videos on YouTube and TikTok, the last decade has witnessed unparalleled demand for crime stories. However, this surge prompts questions regarding the ethical issues inherent in true crime. By condemning the transgression of principles, the romanticised portrayal of perpetrators, and the dramatisation of suffering perpetuated by content creators, we can advocate for transformative legislation to harness the positive potential of the genre.

A glaring ethical issue present in true crime is the violation of consent and privacy of victims and families. Currently, media companies and influencers don’t require their consent when publishing content. The names, ages, backgrounds, and family details of victims are often laid bare for public consumption. This is overwhelming for victims and families, as their most painful and intimate experiences are shared with the world without their permission.

Additionally, these vulnerable stakeholders are subjected to online scrutiny, where netizens give unsolicited opinions and commentary. This reopens the scars left by the ordeals, as exemplified by Netflix’s recent docuseries Monster – Jeffrey Dahmer (2022). The families of Dahmer’s victims were not even informed of the production. Eric Perry, cousin of victim Errol Lindsey, tweeted, “it’s re-traumatising over and over again, and for what?”.

While some argue that the sympathy generated from productions could help families heal, it is imperative to recognise that individuals process sympathy in different ways. Even if sympathy comes from a well-meaning place, if it is uninvited, it may cause feelings of exposure and stress. Therefore, consent must be mandated to end the unethical violation of principles for monetary gain.

Another pressing ethical concern is the romanticised portrayal of perpetrators for increased viewership. Humans, in having adrenaline-craving brains and an inherent fascination with tragedy, are naturally attracted to crime.

Casting conventionally attractive actors to play serial killers, for example Zac Efron as Ted Bundy in Netflix’s 2019 film Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, exacerbates this attraction to a dangerous level. This promotes the toxic fan culture surrounding criminals on media platforms, portraying them as brooding, romantic ‘bad boys’. It gives perpetrators the spotlight and awe, whilst victims are shunned into the shadows.

The real-life consequences of romanticisation were seen in Cameron Herrin’s vehicular homicide case. Due to his physically attractive appearance, netizens on TikTok and Twitter rallied for sentence reduction through the #JusticeForCameron trend. However, this mostly contained irrelevant videos, such as fan edits of his face and highlight reels of his ‘hottest moments in court’, where netizens dubbed him “too cute to go to jail”. A ‘change.org’ petition for sentence reduction was created by fans and signed over 28,000 times, demonstrating how the romanticisation of killers in media has influenced the public to condone the actions of attractive criminals.

This was further confirmed by a 2010 Cornell University study, revealing, “in criminal cases, better-looking defendants receive lower sentences”. Hence, we must hold media producers accountable for romanticised content to stop glorifying the legacies of killers and trivialising their heinous crimes. As consumers, we must remain vigilant and conscious in remembering the monster behind the dazzling smile; a cold-blooded killer.

Furthermore, another ethical dilemma in true crime is the dramatisation of narratives for audience retention. True crime has surged in popularity recently, with a 60% increase in consumption in the US from 2020-2021. This was achieved through insensitive and exaggerated portrayals of people and events to create a ‘juicier’ story, exploiting the victims’ suffering and trauma for entertainment.

As exemplified by the true crime podcast Rotten Mango, content creators often create fictional characterisations of the people involved in the stories for their drama-hungry consumers. They fabricate victims’ thoughts and emotions during the ordeal based on their personal assumptions, which is insensitive to the memory of the victims. In response to Netflix’s Dahmer docuseries, Rita Isbell, sister of a victim, expressed her wish for Netflix to provide tangible benefits such as money to victims’ families. She stated, “if the show benefitted [the victims] in some way, it wouldn’t feel so harsh and careless.” Hence, the dramatisation of crime narratives for entertainment purposes must be restricted, and fictional fabrications of the ordeals banned.

The presently unethical and insensitive genre of true crime demands key changes to harness its positive potential.

We must implement legislation that mandates consent, holds media producers accountable for romanticised content, and restricts dramatisation of narratives.

This will transform the genre into a positive force that empowers those who have endured similar experiences, condemns perpetrators, provides support and closure to victims’ loved ones, and genuinely commemorates victims. By implementing these changes, true crime will evolve into an ethical and empathetic form of media that positively impacts our society.

‘True crime media: An ethical dilemma‘ by Jessica Liu is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

8 questions with FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey

BY Jessica Liu

Jessica Liu (15) is currently attending Abbotsleigh Senior School. At school, she enjoys humanities, maths, and French. Her hobbies include piano, debating and basketball.

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Zoe Timimi 3 APR 2024

We’re living through brutal and devastating times.

Apocalyptic scenes of mass bloodshed are being live-streamed to our phones by journalists who have millions of followers. Awareness of colonial brutality and conflict across the globe has permeated the minds of the Western social media generation on an unprecedented scale, as well as our government’s complicity in it.

Yet life goes on in Australia and across the West. Every week, thousands march through the Sydney CBD to protest genocidal violence in Palestine. We gather in Hyde Park where Palestinians tell us of the destruction of their families and homes, and then we march, passing queues spilling out of high-end shops and chanting ‘while you’re shopping, bombs are dropping’.

It feels as if I’m seeing the individualism that defines our consumer culture with fresh eyes. It’s always been there in plain sight, but suddenly I marvel at how obvious its function is, how it keeps us busy looking in the wrong direction by selling us an alluring dream.

The difference between our everyday and theirs is hard to comprehend. Increasingly I find myself consumed by these overwhelming contradictions; grief at the hands of terror states and the need to keep living in our society of supposed positivity.

I’m questioning how much of my time and energy is wrapped up in searching for the dream-like abundance and pleasure that modern capitalism promises me, unpicking everything I thought I knew about what I wanted from life. How can you feel pleasure in the face of horror?

Consumer culture paints a vision of the good life that’s full of pleasure, relaxation and joy. Influencers sell us manicured images of sun, sea and luxury food, showing us what a free and fulfilled life looks like. But unreachable for many, we often end up seeking consolation in smaller consumer pleasures, distracting ourselves with whatever repetitive hits of relief we can find after we finish our days at work. Dreams of abundance keep people sustained in oppressive systems, searching for a sparkling life that never arrives for most of us.

Dissatisfaction with this cycle of unfulfilling work and empty pleasure seeking has long simmered under the surface. But the lid is now off. The way meaning has been drained from our visions of the good life is brought into focus by brave journalists demanding we confront ugly truths. The daily effort to find pleasure, however small – the morning coffee, the new clothes, the office pizza parties, suddenly pale in significance to the scale and urgency of the problems that face us; the rot at the heart of our system has revealed itself. Discontent has turned to rage. Others feel it too – millions across the globe have been protesting for months on end, refusing to stay silent.

Philosopher and writer Mark Fisher wrote about the emptiness he observed in how his students experienced pleasure. He thought that despite the abundance of instantly pleasurable activities they engaged in, there was still a widespread sense that something was missing from life. He argued that just because we have an abundance of pleasure accessible instantly, it doesn’t mean that life is actually more pleasurable. In fact, he thought the opposite was true.

“Depression is usually characterized as a state of anhedonia, but the condition I’m referring to is constituted not by an inability to get pleasure so much as it is by an inability to do anything else except pursue pleasure.”

He’s not the only one to observe a widespread emotional decay brought on by the constant consumption of quick fix, disembodied pleasure. Kate Soper, in her book Post Growth Living, argues that we must dissociate pleasure and our vision of the good life from the culture of consumerism that so often promotes mindless and toxic pleasure seeking. Like Fisher, she points out how a seductive vision of comfort and abundance so often results in a sterile search for contentment that never comes. She argues that we urgently need to redefine our idea of the good life, asking us to imagine how collective life could transform if we placed care and ethics at the center of our priorities rather than consumer driven gratification.

What both of these writers pick up on is how meaning has been drained from life under Western capitalism, and how pleasure is so often used to plaster over deeply felt doom for the future. They both remind us that sustaining and rich fulfilment does not come from instant gratification.

I think many of us intuitively see that the most pleasurable things we can do with our lives are immaterial, found in the substance of considered, caring and meaningful relationships. What’s a much bigger task is to translate this into finding the pleasure in fighting for bigger social causes. To recognise that a good life must be built on an ethics of justice.

It’s about more than just making different consumer choices, about taking a few hours to go to a march instead of shopping. It’s about finding a set of values that you believe in, and acting in accordance with them, holding yourself and others accountable to the best of your ability with the time and resources you have. Acting with political principle is hard in a society that does everything it can to tempt you into hopelessness, but there is a growing appetite for it. In the face of unthinkable violence, so many have been searching for meaning bigger than the endless cycles of work and shopping.

We first need to recognise that if we want to build any meaningful future for ourselves, we can’t turn away from the dehumanisation of others. The good life isn’t built on collective denial of blistering injustice – burying our heads in the fake comforts of consumerism offers us a bleak future. Our own search for meaning brings us towards our interconnected struggle: Palestine and other occupied nations call for us to fight for justice – our ability to live good lives depends on that justice as well as theirs.

bell hooks said that there can be no love without justice. I think the same can be said for pleasure.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ethics on your bookshelf

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

BY Zoe Timimi

Zoe is passionate about all things mental health, community and relationships. She holds a BA in Sociology and an MA International Political Economy, but has spent the last few years working as a freelancer in various TV development and writing roles.

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Ruby Hamad 25 MAR 2024

Increasingly, it appears that constructive criticism and cynical attacks are being conflated. And perhaps it’s nowhere more apparent or more troubling than when it comes to criticism of the news media.

In 1993, Edward Said stunned the world of cultural criticism with his revolutionary critique of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. The literary professor and avowed lover of the Western literary canon reviewed Austen in a way like never before: as a cultural artefact that reflected and embodied the British imperial ethos.

Austen, he wrote, “synchronises domestic with international authority, making it plain that the values associated with such higher things as ordination, law, and propriety must be grounded in actual rule over and possession of territory.”

As both a critic and a fan, Said was surprised at accusations he was discrediting Austen. Rather, he was demonstrating that even novels ostensibly about domesticity could not be separated from the politics of the time.

Said showed that art not only can but must be both enjoyed and critiqued.

That criticism must, in other words, be constructive.

Said’s approach to criticism is more needed now than ever. Increasingly, it appears that constructive criticism and cynical attacks are being conflated.

I find this nowhere more apparent or more troubling than when it comes to criticism of the news media.

After The New York Times opened an Australian bureau several years ago, some readers and journalists complained its coverage was patronising. Such complaints, journalist and former Times contributor Christine Keneally said, indicated that locals felt it “considered itself superior to the local press”.

As I wrote at the time, “grievances included needlessly explaining Australia to Australians, engaging in parachute journalism, and not employing enough local journalists.” The newspaper wasn’t doing anything that Australian journalists don’t do as a matter of routine when covering foreign places. Whether wittingly or unwittingly, English-language media often assume an air of authority as they “explain” the local culture and events to their audience back home, adopting an almost anthropological tone that has been frequently and hilariously satirised.

The problem, then, was not the Times per se but Western approaches to journalistic “objectivity” that equate their own interpretations with fact.

Consequently, the criticism centred on mocking the Times rather than interrogating the broader problem of Western journalistic processes and assumptions. This merely served to make the Times defensive and resistant to the criticism.

It is futile to simply demand that journalists “do better” on certain issues or to single out specific publications when the problem so often comes down to Western media conventions as a whole.

How then should we go about it? Robust public constructive criticism of the press is vital. Not least because:

“There is everywhere a growing disillusionment about the press, a growing sense of being baffled and misled; and wise publishers will not pooh-pooh these omens.”

This quote could easily have been written last week but comes from legendary American editor Walter Lippmann in his 1919 essay ‘Liberty and the News’.

Lippmann urged fellow journalists not to reject criticism but use it as a means to improve. “We shall advance when we have learned humility,” he predicted hopefully. “When we have learned to seek truth, to reveal it and publish it; when we care more for that than for the privilege of arguing about ideas in a fog of uncertainty.”

Some of this antipathy towards critique could perhaps be explained by a lack of consensus of what critique actually is. The job of a critic is often misrepresented as being merely “to criticise”, telling us what is good and bad. However, the true role of a critic, explains culture writer Emily St. James, is “to pull apart the work, to delve into the marrow of it, to figure out what it is trying to say about our society and ourselves”.

Social media complicates our understanding further because of the difficulty of in reading people’s tone and intent online. Then there is also the unfortunate fact that social media is so often used deliberately as a platform to launch cynical, shaming attacks, which makes it even more challenging to distinguish criticism from cynicism.

This can be applied to the news media as easily as it can to novels or films.

As media scholar James W Carey observed, and as Said demonstrated in his critique of Austen, genuine criticism is not a “mark of failure or irrelevance, it is the sign of vigour and importance”.

Over many decades historians and scholars have agreed on the shape criticism should take. Namely, that criticism is an ongoing process of exchange and debate between the news media and its audience. That it should be grounded in knowledge rather than solely in emotion. That it should not be pedantic, petty, and shaming.

Media researcher Wendy Wyatt defined it simply as “the critical yet noncynical act of judging the merits of the news media”.

And as media scholar James W Carey observed – and Said demonstrated with Austen – genuine criticism is not a “mark of failure or irrelevance, it is the sign of vigour and importance”.

Lippmann and Wyatt advocated for criticism of the press by the press, such as a public editor or ombudsman hired by the publication solely to address readers’ concerns and complaints.

Others including Carey argued that true criticism can come only from the outside; from academics or authors that are not on the payroll to ensure fairness, and minimises the possibility of retribution. Many journalists, they warn, have been ostracised by their peers for daring to critique their own.

Much of the onus, then, falls to editors and publishers to open up the news media to constructive criticism, and to not “pooh-pooh” our concerns. But we, as individuals and as a society, all bear some responsibility for fostering a social climate that encourages such critique.

If we are to demand that journalists heed our criticism, we must also enter into it in good faith. Like journalism itself, any and all criticism should also be weighed up on its merits. Our ultimate goal should not be merely to shame journalists but to transform the news media in an ongoing process of reform and improvement.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

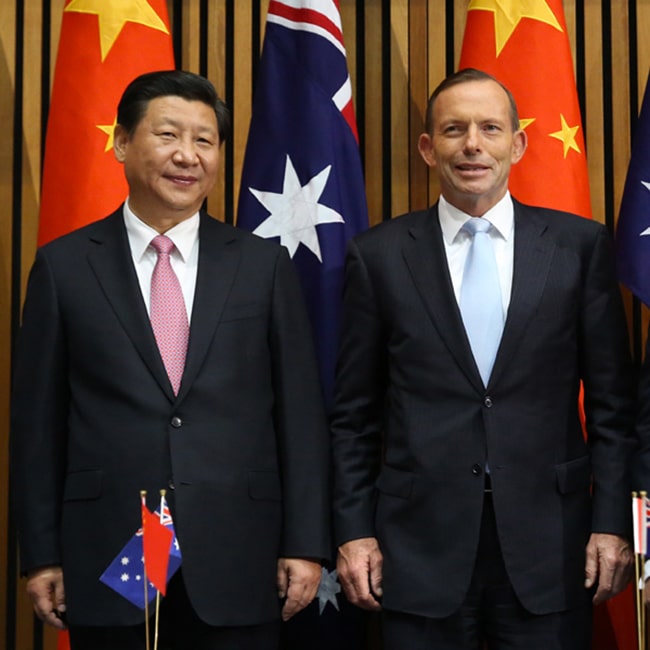

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

LISTEN

Society + Culture

FODI: The In-Between

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

He said, she said: Investigating the Christian Porter Case

BY Ruby Hamad

Ruby Hamad is a journalist, author and academic. Her nonfiction book White Tears/Brown Scars traces the role that gender and feminism have played in the development of Western power structures. Ruby spent five years as a columnist for Fairfax media’s flagship feminist portal Daily Life. Her columns, analysis, cultural criticism, and essays have also featured in Australian publications The Saturday Paper, Meanjin, Crikey and Eureka St, and internationally in The Guardian, Prospect Magazine, The New York Times, and Gen Medium.

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff Major General Paul Symon Dr Miah Hammond-Errey 19 MAR 2024

Better ethical approaches for individuals, businesses and organisations doesn’t just make moral sense. The financial benefits are massive, too.

It might seem a little ironic to take ethics advice from an intelligence agency that consciously deploys deception, yet it shows why access to ethical advice is vitally important. Indeed, we argue that the example of an ethics counsellor within ASIS demonstrates why every organisation should have (access to) an ethical adviser.

Ethics is often considered to be a personal or private activity, in which an individual makes decisions guided by an ethical code, compass or frame of reference. However, emerging technologies necessitate consideration of how ethics apply “at scale”.

Whether we are conscious of this (or not), ethical decisions are being made at the “back end” – or programming phase – but may not be visible until an outcome or decision, or user action, is reached at the other end of the process.

Miah Hammond-Errey describes in her book, Big Data, Emerging Technologies and Intelligence: National Security Disrupted, how “ethics at scale” is being driven by algorithms that seek to replicate human decision-making processes.

This includes unavoidable ethical dimensions, at increasing levels of speed, scope and depth – often in real time.

The concept of ethics at scale means that the context and culture of the companies and countries that created each algorithm, and the data they were trained on, increasingly shapes decisions at an individual, organisation and nation-state level.

Emerging technologies are likely to be integrated into work practices in response to the world itself becoming more complex. Yet, those same technologies may themselves make the ethical landscape even more complex and uncertain.

The three co-authors recently discussed the nexus of ethics, technology and intelligence, concluding there are three essential elements that must be acknowledged.

First, ethics matter. They are not an optional extra. They are not something to be “bolted on” to existing decision-making processes. Ethics matter: for our own personal sense of peace, to maximise the utility of new technologies, for social cohesion and its contribution to national security and as an expression of the values and principles we seek to uphold as a liberal democracy.

Second, there is a strong economic case for investing in the ethical infrastructure that underpins trust in and the legitimacy of our public and private national intuitions. A 10 per cent improvement in ethics in Australia is estimated to lead to an increase in the nation’s GDP of $45 billion per annum. This research also shows improving the ethical reputation of a business can lead to a 7 per cent increase in return on investment. A 10 per cent improvement in ethical behaviour is linked with a 2.7 to 6.6 per cent increase in wages.

Third, ethical challenges are only going to increase in depth, frequency and complexity as we integrate emerging technologies into our existing social, business and government structures. Examples of areas already presenting ethical risk include: using AI to summarise submissions to government, using algorithms to vary pricing for access to services for different customer segments or perhaps using new technologies to identify indicators of terrorist activity. That’s before we even get to novel applications employing neurotechnology such as brain computer interfaces.

Ethical challenges are, of course, not new. Current examples driven by new and emerging technologies include privacy intrusion, data access, ownership and use, increasing inequality and the impact of cyber physical systems.

However, an extant need for ethical rumination is, for now at least, a human endeavour.

As a senior leader of ASIS, with a background in the military, Major General Paul Symon (retd) strongly supported resourcing a (part-time) ethics counsellor. He was aware the act of cultivating agents, and the tradecraft involved, would inevitably demand moral enquiry by the most accomplished ASIS officers.

His belief was without a solid understanding of ethics, there was no standard against which the actions of the profession, or the choices of individuals, could be measured.

So, a relationship emerged with the Ethics Centre. A compact of sorts. Any officer facing an ethical dilemma was encouraged to speak confidentially to the ethics counsellor. The conversation and the moral reasoning were important.

General Symon guaranteed no career detriment to anyone who “opted out” of an activity so long as they had fleshed out their concerns with the ethics counsellor. Often, an officer’s concerns were allayed following discussion, and they proceeded with an activity knowing there was a justification both legally and ethically.

Perhaps if we’d had ethical advisers available across other institutions, we might have prevented some of the greatest moral failures of recent times, such as the pink batts deaths and robodebt.

If we had ethical advisers accessible to industry, then perhaps we’d have avoided the kind of misconduct revealed in multiple royal commissions looking into everything from banking and finance to the treatment of veterans to aged care.

We believe our work over years, including examples in defence and intelligence, demonstrates practical examples and the requirement to build our national capacity for ethical decision-making supported by sound, disinterested advice. That is one reason we support the establishment of an Australian Institute for Applied Ethics with the independence and reach needed to work with others in lifting our national capacity in this area.

Pledge your support for an Australian Institute of Applied Ethics. Sign your name at: https://ethicsinstitute.au/

This article was originally published in The Canberra Times.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Cancel Culture

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Life and Debt

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Accountability the missing piece in Business Roundtable statement

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture