The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 15 DEC 2023

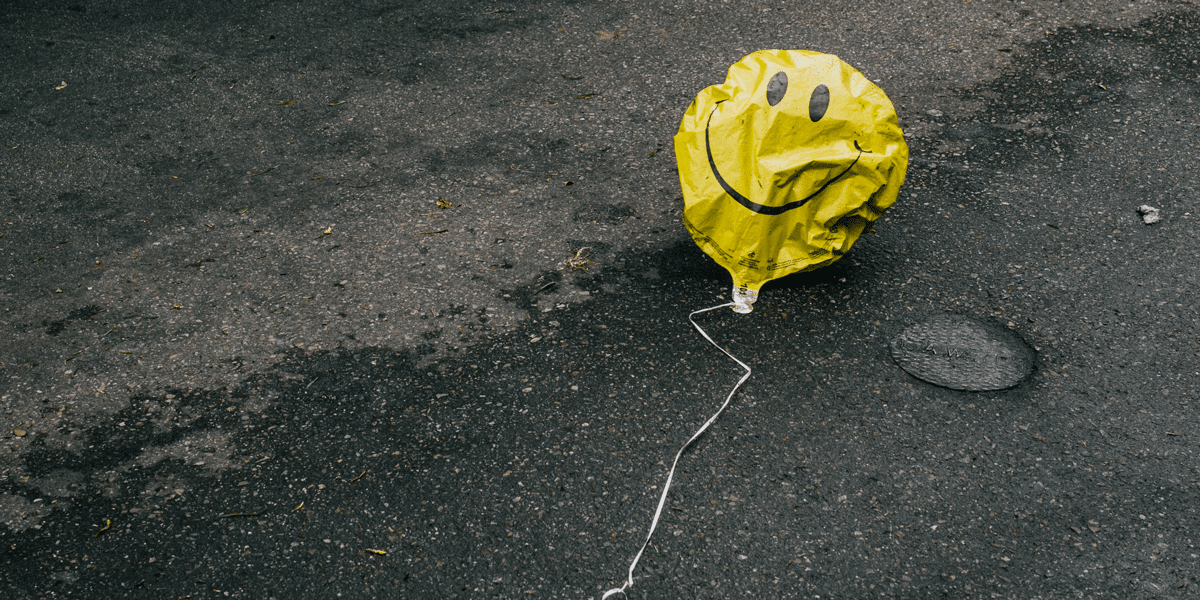

Can we be too nice? On the surface, it seems absurd to say we should put a cap on how nice we should be. But if we overdo it, we can end up shirking our other ethical obligations.

Skim the headlines or scroll through social media and you’d be forgiven for concluding that there’s a serious deficit of niceness in the world today, and if only people were a little more kind, compassionate and giving, then the world would be a much better place.

Imagine a nicer world where other drivers consistently backed off to let you merge lanes, or shrugged off your occasional failure to check a blind spot with a smile and a wave. Imagine a workplace where everybody lifted each other up, and covered for you when you needed a break. Imagine a world with more Dumbledores and fewer Snapes. Imagine a world without Karens.

Most philosophers have sought such a world by urging us to cultivate niceness. Confucious promoted the foundational virtue of ren, often translated as benevolence or humanity. Aristotle argued that the path to flourishing lay in cultivating virtues like magnanimity, generosity and patience. Christian scholars promoted temperance was a cardinal virtue. In more modern times, Peter Singer has said we ought to take the compassion we feel towards close family and friends and expand it to cover all sentient creatures, human and animal. In short: be nice.

But there’s also a catch with niceness. If we take it to excess, we can leave ourselves vulnerable to exploitation, fail in our ethical duties and even undermine the very moral foundations of our community.

This is because a world where everyone is fully trusting and selflessly giving is a ripe hunting ground for those who are willing to abuse that trust and get ahead by stepping on the backs of others.

The paradox of niceness

This phenomenon can be modelled using the popular game theoretic thought experiment, the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Imagine a situation where two bank robbers are arrested and held in separate cells, unable to communicate with each other. The police have no other witnesses, so they’re relying on the suspects’ testimony to prove the case against them. If both suspects confess, they’ll both receive a five-year sentence. If they both remain silent, then the police will only be able to charge them with a minor offense carrying a one-year sentence. However, if one of them testifies while their partner remains silent, then the dobber will be set free while their partner will go to jail for 10 years.

On the surface, it seems sensible for them both to remain silent. That would be the “nice” thing to do because it benefits them both. But there’s a twist. If one of the suspects believes that their partner will remain silent, then they have an opportunity to testify against them and get off scott-free, while their partner is thrown in the slammer. They also know that if they remain silent, then their partner will have an opportunity to dob them in. As a result, the most reasonable thing for either of them to do is dob on the other, which means they both end up with a harsher penalty than if they’d both cooperated and stayed silent.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma models a fundamental truth when it comes to social interaction: if we we’re nice, we all benefit, but there will always be a temptation to exploit the charity of others to get ahead, and in doing so, we can end up destroying the possibility of cooperation altogether.

There have been whole virtual tournaments using the Prisoner’s Dilemma to see what kinds of strategies – whether “nice” or “nasty” – will yield the best results for the agents playing the game. And it’s from these tournaments that another twist emerges.

In a single Prisoner’s Dilemma game, the nasty dobber has the upper hand, especially if their partner is nice. However, when the same agents play the game over and over, it turns out that it pays to be nice, because you’re likely to be punished in the next game if you’ve been nasty. When you add in some real-world flavour to the game, like making it so that agents can sometimes mistakenly defect when they meant to cooperate, it’s the nicer agents that come out on top.

But these simulations show that niceness has its limits. Those agents that are unconditionally nice tend to get exploited by nasty ones. However, those strategies that are conditionally nice, and that defect only to punish bad behaviour, do best of all.

Toxic niceness

Back in the real world, what this means is that it is possible to be too nice. If we’re unconditionally generous and forgiving, then we leave ourselves open to exploitation by people who will take advantage of our niceness.

It’s likely we all know someone who is a natural giver, someone whose empathy is overflowing and who goes out of their way to help everyone around them. These people are often much loved, but they can also be crushed under the weight of their own compassion, sometimes neglecting their own wellbeing, and it’s not uncommon for others to take advantage of their generosity.

Such unconditional niceness can also prevent us from punishing those who deserve it. You may have also worked for a manager who was overly forgiving, not only of minor transgressions, but also behaviour that was toxic or harmful to others. Punishment is inherently unpleasant, and the overly nice can be reluctant to mete it out, staying their hand while wrongdoers run amok. That not only undermines the moral community, but it makes it harder to hold people to account for their actions, preventing them from growing by learning from their mistakes.

Niceness is good. Be nice. But not so nice that you allow others to be nasty.

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Normativity

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

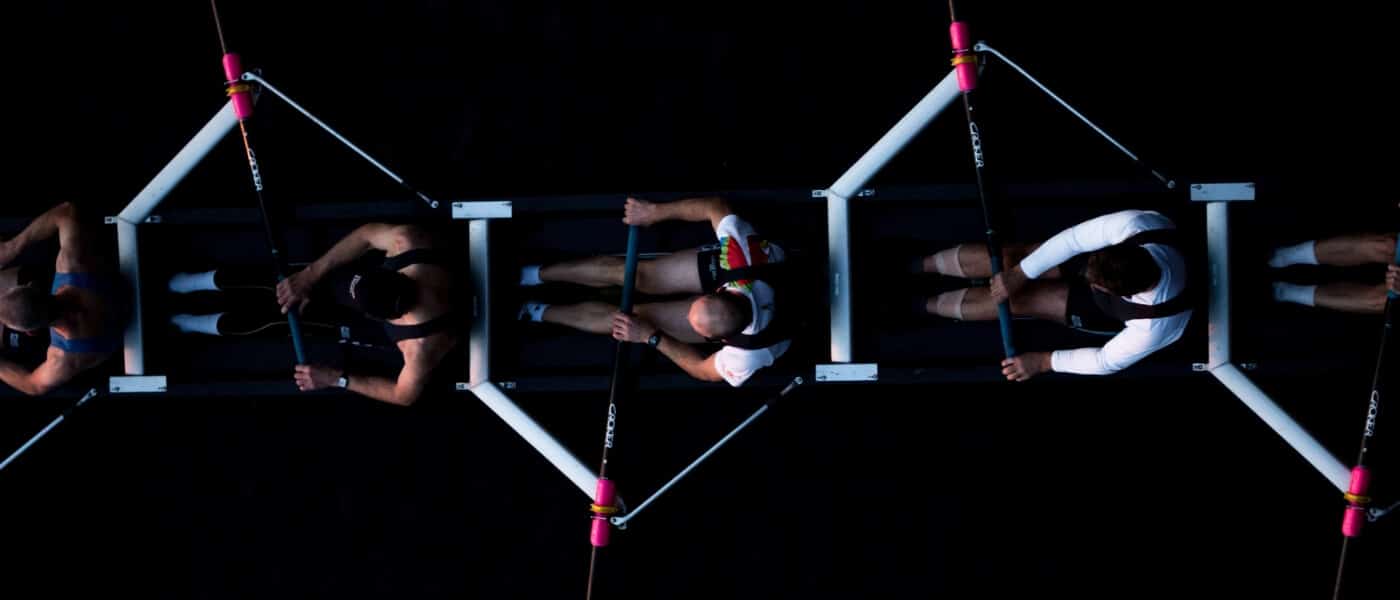

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why morality must evolve

11 books, films and series on the ethics of wealth and power

11 books, films and series on the ethics of wealth and power

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 7 DEC 2023

They say power corrupts. And for good reason. Ethics is in constant tension with power. The more power or money someone has, the more they can get away with.

A central concern of money and power is how those who have it should be allowed to use it. And a central concern of the rest of us is how people with money and power in fact do use it.

Here are 11 books, films, tv shows and podcasts that consider the ethics of wealth and power:

Parasite

A Korean comedic thriller film about poverty, the contrast between the rich and poor and the injustice of inequality.

Succession

An American satirical comedy-drama series detailing a powerful global media and entertainment conglomerate. Run by The Roy family, the unexpected retirement of the company’s patriarch ignites a power struggle.

Animal farm – George Orwell

A satirical novel of a group of anthropomorphic farm animals who rebel against their human farmer, hoping to create a society where the animals can be equal, free, and happy.

Generation Less – Jennifer Rayner, FODI

The Colonial Fantasy – Sarah Maddison

A call for a radical restructuring of the relationship between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and governments.

White Lotus

An American dark comedy-drama anthology series, which socially satires the various guests and employees of a resort, exploring what money and power will make you do.

The Deficit Myth – Stephanie Kelton

An exploration of modern monetary theory (MMT) which dramatically changes our understanding of how we can best deal with crucial issues ranging from poverty and inequality to creating jobs, expanding health care coverage, climate change, and building resilient infrastructure.

Squid game

A Korean survival drama series where hundreds of cash-strapped contestants accept an invitation to compete in children’s games for a tempting prize, but the stakes are deadly.

Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women – Kate Manne

A vital exploration of gender politics from sex to admiration, bodily autonomy, knowledge, power and care. In this urgent intervention, philosopher Kate Manne offers a radical new framework for understanding misogyny.

The Lehman Trilogy – Stefano Massini

Originally a novel, and since adapted into a three-act play, The Lehman Trilogy tells the story of modern capitalism through the saga of the Lehman brothers’ bank and their descendants.

Life and Debt podcast

Produced by The Ethics Centre, Life & Debt is a podcast series that dives into debt, what role it has in our lives and how we can make better decisions about it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ethics on your bookshelf

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

A note on Anti-Semitism

I was recently proud to join hundreds of others in signing an open letter condemning Anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and all other forms of discrimination.

The fact that such a letter needed to be written is deeply troubling. However, the world has been witness to the horrific consequences of remaining silent when the beast of race-based hatred begins to stir.

The great attraction of the statement I signed lay in its embrace of a positive principle that extends to every person – irrespective of their identity, conduct or circumstances. The principle of ‘respect for persons’ is the foundation upon which all human rights ultimately rest. It is an affirmation that every person has an irreducible, intrinsic dignity that cannot be reduced or forfeited. Although the rising incidence of Anti-Semitism may have prompted the statement, its concern extends to all who are at risk of harm.

Yet, what exactly is this harm? And how do we properly distinguish between vile acts of Anti-Semitism, on the one hand, and mere criticism on the other? For example, is holding Hamas accountable for the death of innocent non-combatants either ‘Anti-Palestinian’ or ‘Islamophobic? I think not. Nor is it Anti-Semitic to hold the State of Israel to account for acting in conformance with the laws of armed conflict. Both can be held accountable to the same standard without denying the intrinsic dignity of any individual or group.

Expressing sympathy for the plight of ordinary Palestinians, caught in the crossfire of an historically intractable dispute, does not amount to Anti-Semitism. Nor is it ‘genocidal’ to support the existence of the State of Israel (even while condemning many of the actions of its government).

Anti-Semitism is a very distinctive and potent form of evil. It denies the full and equal humanity of Jewish people – and endorses the destruction of their religion, culture, history and bodies. It has its own recognisable symbols – the Nazi Swastika, the ‘Heil Hitler’ salute (and associated symbology) – and revels in the despicable iconography of gas chambers and other elements in the apparatus of the Holocaust. It should be monitored and restrained with every ounce of energy and vigilance we can bring to bear. For where Anti-Semitism lives so there breeds all the other cesspools of hatred and despair.

So, it is unbearably sad when people loosely apply the label ‘Anti-Semitic’ on any occasion where Jewish people experience even the slightest form of annoyance, anger or discomfort.

We have been witness to an example of such ‘fast and loose’ language in the last couple of days. The ‘trigger’ incident was a decision by three actors to wear Palestinian Keffiyeh during the curtain call for Sydney Theatre Company’s opening performance of Chekhov’s The Seagull. The actors took this action without STC’s knowledge and without the support of the other cast members. Whether one agrees with the sentiment behind that statement is beside the point. In practice, they hijacked the company’s stage to make an entirely private, political statement. Now everyone else is left to pick up the pieces.

STC’s audience, supporters and donors are entitled to be annoyed by what occurred. So are the Board, management and members of the STC who had no knowledge of the planned stunt. Yet, nothing that was done on the night amounts to an act of Anti-Semitism. Naïve, perhaps. Unauthorised … certainly! Anti-Semitic … not at all.

To apply that label in the current circumstances is understandable when one considers the raw nerves and ancestral fears that are chafed in response to rising incidents of actual Anti-Semitism. However, over-reacting in this case (or others like it) brings about its own damage – especially when one part of our diverse, multicultural community bands together to boycott (‘cancel’) what it finds offensive. This approach did not help the cause of Christians and Muslims who have sought to censor those who offend or criticise. And I doubt that it will help the Jewish community. A diverse and vibrant community is made to seem monolithic in its outlook and concerns – separate from the whole.

I do not know if there are any Anti-Semites working at STC. However, I would be amazed if there were not at least some ardent critics of Israel (as there are amongst many Jewish people – the world over). But to be a critic of Israel is not the same as being an ‘Anti-Semite’. Of course, one can be both – but the distinction is vital and we all need to discern and apply the difference

Jewish people have every right to speak out when offended (a right we all enjoy). In doing so, they are often driven by fears grounded in millennia of persecution culminating in the Nazi’s ‘final solution’.

We should never be silent or indifferent in the face of Anti-Semitism. However, I fear that being fast and loose in labelling events and people as ‘Anti-Semitic’ risks undermining the significance of that terrible point in human history, which we must never do.

For the Holocaust stands for far more than the fate, alone, of the Jewish people. It is a potent warning of what horrors lurk within the human psyche and the power of that warning must never lose its place in humanity’s collective memory – for it threatens us all.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s ethical obligations in Afghanistan

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

The ethics of workplace drinks, when we’re collectively drinking less

The ethics of workplace drinks, when we’re collectively drinking less

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY Nick Jarvis 30 NOV 2023

There is no denying that alcohol is inextricably linked to Australia’s social DNA. Going to the pub with mates, drinking at a BBQ or picnic, at dinner parties, house parties, birthdays or gigs – all of these link “having a drink” with “having a good time” in our national consciousness.

A Roy Morgan research study in 2022 found that the majority (67.9%) of Australians had consumed alcohol in the last month, with the average Australian consuming nearly 10 litres of pure alcohol a year (2017-18 study).

In fact, a 2021 survey named Australians the heaviest binge drinkers in the world, finding we would binge an average of 27 times a year, almost double the global average – although overall alcohol consumption rates have been dropping since the early 2000s.

When it comes to work, alcohol is closely tied to socialising – Friday after work drinks, celebratory drinks to recognise a goal achieved, Christmas parties, launches, networking events; all of them invariably involve alcohol in some capacity. Some people might even say they can’t stomach a work social event unless alcohol is involved.

In some cultures binging is even built into work culture – in China, heavy drinking after a deal has been sealed is a time-honoured ritual, where everyone involved has to let their guard down and form a “moral contract” bound by heavy drinking together. In Japan, nomikai, or drinking parties, are an integral part of workplace culture for socialising and bonding, and everyone is expected to take part.

Alcohol certainly has its benefits as a social lubricant at work events, allowing people to bond together faster, but it also has its dark side – harassment after the lowering of inhibitions, saying something inappropriate to a colleague, potentially embarrassing yourself in front of your team or clients, even assault can follow heavy drinking with work mates.

Having work social rituals based around the consumption of alcohol is also exclusionary for those who choose not to drink, whether because of physical or mental health reasons, religious or cultural reasons, or because they’ve quit or just don’t want to. People may feel pressured to drink in work social spaces, to be social, to network and keep up with the team. A 2019 survey by the UK’s Drinkaware found that more than half of workers surveyed would like there to be less pressure to drink at work events.

And people are increasingly opting out of alcohol-fuelled leisure time, a trend led by the more risk-aware Gen Z. The 2019 National Drug Strategy Household Survey found that, in 2001, the people most likely to have consumed alcohol daily, used illicit drugs or smoked cigarettes were in their 20s. By 2019, that had changed to people in their 40s and 50s. The survey also found the number of people in their 20s who don’t drink at all increased from 9% to 22% between 2001 and 2019.

The drinks industry has adapted, with sales of zero alcohol substitutes rising over 100% in the two years to 2022, but in many cases our workplaces have not.

As more people are becoming ‘sober curious’, or trying to reduce their alcohol intake, it can make it awkward in the workplace when you decline an “al-desko” beer or to troop along to Friday after work drinks. Missing out on socialising with your colleagues can also be a barrier to making closer connections and friendships.

So what responsibility do workplaces have to their employees to offer alcohol free options for socialising, while also respecting the rights and choices of employees who want to drink responsibly?

Employers are mandated ethically and legally to provide safe, inclusive workplaces, and this should include respecting people’s decision to either drink alcohol or not drink alcohol and still be able to participate socially with their workmates and colleagues.

Rather than banning alcohol at work, providing zero alcohol drink options and alcohol-free bonding activities are an easy way employers can foster an inclusive environment, while respecting individual choice.

Just as we’ve seen the “smokers huddle” outside office buildings dwindle to near invisibility in the past ten years, I predict that we’ll soon see a marked increase in the availability of non-alcoholic options at work events and alternative socialising options that don’t come with any pressure, latent or otherwise, to imbibe. Which can only be a good thing for our livers and work-related hangxiety.

BY Nick Jarvis

Nick Jarvis is a Sydney-based editor and writer on the arts, culture and technology. He's written for The Ethics Centre, the Walkleys, Sydney Festival, Sydney Film Festival, Vice and many Australian arts organisations. He currently works for Sydney Festival.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Has passivity contributed to the rise of corrupt lawyers?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 23 NOV 2023

One of the first things I learned when travelling in Europe, knowing only English, was to prioritise learning the word “sorry” when preparing to enter a new country.

There’s nothing wrong with learning “hello”, “thank you” and “please”, “I am…” and “where’s the nearest…”, but if you’re going to learn one word by heart, that’s the one I’d recommend. If you get yourself in trouble, it will likely be the word you need the most.

I speak from experience. Picture a nineteen-year-old washing her hands in the fountain at the foot of The Spanish Steps. Unbeknownst to her, the police have just rebuked some fellow tourists for cooling their sweaty feet in the waters of this national treasure—and told the watching crowd to heed their warning, show respect.

When their whistles blew at me and I was asked to show my passport, I didn’t have the words to explain that I’d just been to the loo and had been unable to find a handle for the tap. This was before sensors became commonplace; perhaps there was a pedal, but I hadn’t thought to look. Instead, I’d opened the door (with difficulty—I’d already covered my hands in pink slimy soap) and headed for the next available water source.

I had my reasons, but I didn’t have the words to explain why I’d done what I’d done, and until some friends explained later, I couldn’t fully understand why what I’d done had been so very wrong.

I could say Lo siento, and did, repeatedly.

I was reminded of this incident when reflecting on the ways in which we use the word “sorry” in daily life.

Sometimes we’re not apologising at all—we’re expressing sympathy to a bereaved friend, or being polite to a stranger. The bereavement “sorry” might translate to: “I wish you didn’t have to go through this”, or “I really feel for you”. The polite “sorry” to a stranger might translate to “excuse me”, or “I excuse you”. It might not be “performative” at all; we use it as a statement, nothing more. Or we’ll say “sorry I’m late” when we’re not sorry, but are late. If we really are sorry we’re late; our eyes, our tone, must do the work.

At other times, we apologise when we needn’t; we say “sorry” if we burst into tears when we are “supposed” to be keeping it together, or if we’ve had to ask for help when we’d hoped to solve a problem on our own.

In the workplace, if we’ve been asked to do something we haven’t been trained to do, and need to take up a manager’s time to find out how, we might apologise when really, we’re just doing our job, and asking them to do theirs.

In the context of close friendship, pouring out our worries, or asking for help, or advice, or both, isn’t something to apologise for, it’s (in part) what friendship is for. I know this, yet I find myself behaving otherwise. Just the other day I said “sorry” to a friend while crying on the phone, even though when friends do this to me I tell them off. Being trusted in this way honours a person more than it puts them out. When you love someone, you want to help; real “sorry” territory is more likely to be shutting a loved one out, than letting them in.

This is because “real sorry territory” is using the word in the deepest sense of the word; it’s apologising for hurting someone. It’s not using the word to escape consequence, it’s using the word to express heartfelt regret for causing real harm and, rather than making excuses, choosing to take responsibility.

It can be easy to say “sorry” when we don’t really mean it—when we’re being polite, when we’re going through a motion, avoiding punishment. It’s easy to say it, even mean it, when we see we’ve made a dumb mistake: Lo siento! Lo siento! It can roll right off the tongue.

In the case of the Fontana della Barcaccia, I’m pretty sure my excuses would have only caused further offence. Looking back, I’m glad I couldn’t say another word. But that sorry didn’t cost me, it helped me.

It’s using the word to admit—to ourselves as much as to somebody else—that we’ve not only caused offence, but ongoing hurt, and to ask for undeserved forgiveness, that’s hard. Even if we haven’t done wrong technically, we might have had a chance to help, and turned away. Using “sorry” to express true regret—to “repent”—could be the rarest use of “sorry” there is.

The rarest and, when it’s sincere, when it changes how we think and act, the most powerful. A word that can mean little can mean much; can be the difference between making excuses, or facing the truth; between a wound that keeps on causing pain, and one that, finally, begins to heal.

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Plato’s Cave

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Respect

WATCH

Relationships

Moral intuition and ethical judgement

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Joseph Earp 20 NOV 2023

The original The Little Mermaid, an animated fable about a young woman searching – literally – for her voice, has what may seem like only a loose relationship with reality.

Sure, the film is filled with themes of yearning, the desire for autonomy, and a struggle for independence, all of which still resonate deeply with the lived experience of its target audience of young women. But it’s also populated with a singing fish, a cursed sea witch, and a range of colourful, deeply fantastical supporting characters.

But in our increasingly divided age, fantasy is not a simple proposition anymore. Just look at the culture war that the CGI-saturated remake of The Little Mermaid has been dragged into, with the film facing “backlash” from those who have argued that the casting of a black Ariel (Halle Bailey) represents a break from “reality”. Their argument – that this new Ariel is not the one they grew up with, a premise that rests on the idea that there is a “real” Ariel to be deviated from.

These arguments are, in essence, arguments about the nature of fantasy – about how fantastical these stories are allowed to be. Fantasy authors can do anything. So what should they do?

How much fantasy is allowed?

The Little Mermaid is not the only modern fantasy story that has been plunged into debates around diversity and representation. The characters of Rey and Rose Tico from Disney’s new Star Wars trilogy faced significant backlash for being female, while the series’ black Stormtrooper, Finn, was criticised as breaking the canon. Stormtroopers were clones, went the argument – so how could one of them be black? Indeed, racist backlashes against casting in fantasy have become so commonplace that Moses Ingram, who played the villainous Reva Sevander in the Obi-Wan Kenobi miniseries, started sharing some of the vile messages that she received.

Those responsible for these backlashes tend to argue that the casting of diverse actors “breaks canon”, and disrupts storytelling rules. Some fans will argue that as Stormtroopers are always white in the world of the Star Wars story, they always must be. This was the explanation for the backlash that met the casting of diverse actors in the new Lord of the Rings series, The Rings of Power – Tolkien’s world was white, went the argument, so any story told in that world should be too. Of course, these “fans” do not acknowledge the possibility that the canon of these stories could be racist, and that breaking the canon might be morally necessary. They merely hold to the story as it was written.

This is an argument about fantasy: about how “real” these stories should be. Fantasy authors can do anything, tell any story, infuse their characters with magical explanations that fly in the face of reality. But they do still have to abide but certain rules. No-one would enjoy the world of Hogwarts if J.K. Rowling constantly threw up magical explanations that defied one another to advance the plot. There needs to be some consistency; some “reality”.

Those who cry foul when diverse actors are cast in fantasy do so because they have smuggled a bad ethical argument into one about consistency.

They are making an ethical claim – they do not want to see diverse communities in their art – and pretending it is an aesthetic claim – that they are talking about stories, not about ethics.

In at least some cases, we can assume that this is just a bad faith argument: that these people know in our modern age that they cannot make an openly racist remark, and so scratch around in the world of aesthetics to disguise their bigotry. But even if these people really think that they’re talking about aesthetics, the mistake is to assume that ethics and aesthetics easily pull apart.

Your dreams aren’t divorced from the real world

In her landmark essay The Right To Sex, the philosopher Amia Srinivasan explores the moral weight of aesthetic choices. In her case, she was exploring those who express sexual preference – cis men who desire a certain kind of woman, for instance, with a certain body. But her conclusions are helpful for us here too.

In essence, Srinivasan wants to balance the freedom to choose – people should be able to desire whom they want to desire, and not be forced to change their desires by others – with the idea that some choices are bigoted or small-minded in some way – say, the person who only desires Asian women, or the person who doesn’t desire any Asian women at all.

What Srinivasan encourages is an interest in one’s own desires. She suggests people explore and understand why they want what they want, and to be aware that sometimes those wants can come from bad, unethical places. In essence, Srinivasan made it clear that purely aesthetic choices are actually ethical choices – that things that seem “merely a matter of taste” can actually come from bigotry.

So it goes with fantasy. The fantasy genre is one of dreams; of pure imagination. But that imagination is born from the real-world. And our real-world contains bigotry and hate.

Fantasy writers dream, but they dream in a way that is influenced by morals, preferences, and real-world concerns.

This isn’t just imaginative play. This is play that is responsive to the real world. And as such, ethics should remain a concern. There are people out there who say that they genuinely desire a white Ariel – that seeing a Caucasian mermaid is of tantamount importance to them. What Srinivisan teaches us, is that we do not need to see this desire as emerging from a vacuum. It’s not “just” taste. It’s taste formed from a society that for too long has prioritised white bodies.

It’s like the philosopher Regina Swanson writes.: “[Fantasy] writers bring form to formlessness, creating a narrative that arises from the deep inner places of the mind,” she has put it. “As such, fantasy can reveal our collective hopes, dreams, and nightmares.” Those hopes, dreams, and nightmares aren’t “just” fantasies. They’re meaningfully real.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

Big thinker

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Joanna Bourke

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

How to find moral clarity in Gaza

How to find moral clarity in Gaza

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 13 NOV 2023

Confronted by the horrors of war between Israel and Hamas, one is naturally drawn to those who offer moral certainty.

After all, it is repugnant to the soul to think that there is no sure ground for the revulsion we feel when confronted by the carnage unleashed on October 7th. Yet, to reject the dead hand of moral relativism does not mean that we must uncritically embrace one side or the other as being either wholly vicious or wholly virtuous.

Here, distinctions matter. For example, there is a vital difference between the Jewish people and the Government of Israel. Likewise, the Palestinian people are not defined by Hamas. When free to do so, many Jews and Palestinians are as one in criticising and condemning the actions of those, in power, who claim to be acting in their name. So, in our search for ethical clarity, we need tools to produce certainty while allowing us to discern relevant distinctions.

By way of background, I should mention that I have been teaching military ethics, both at home and abroad, for more than three decades. In that time, I have typically dealt with what occurs at the ‘pointy end’ of warfighting – with people of all ranks and many cultures. This has included sitting with generals, most of them active operational commanders, from twenty-five nations, as we have discussed some of the most challenging issues ever to be encountered by those who serve in the profession of arms. In the course of my work in this area, we have naturally focused on the requirements of Humanitarian Law and Just War Theory. Those requirements are routinely quoted at times such as these. However, I think that there are even more fundamental principles that can serve us well – whether military or civilian – as we seek to establish firm ground on which to stand.

The first and most fundamental of these principles is that of ‘respect for persons’. This principle requires us to recognise the intrinsic dignity of every person – irrespective of their culture, gender, sex, religion, etc. As such, no person or group can be used merely as a means to some other end. Thus, the prohibition against slavery. No person or group can be deemed ‘less than fully human’ – even those who engage in unspeakably wicked deeds. The torturer or genocidal murderer might forfeit their lives under some systems of justice – but never their intrinsic dignity. That is why we insist on minimum standards of care for prisoners of war – and even war criminals awaiting their fate. Those who deny others intrinsic dignity open the gates to the hells of torture, genocide and the like.

The second principle is captured in an aphorism derived from the Canadian philosopher, Michael Ignatieff. Ignatieff argues that the difference between a ‘warrior’ and a ‘barbarian’ is ‘ethical restraint’. The idea is reflected in principles like those of ‘proportionality’ (minimum force required) and ‘discrimination’ (only legitimate targets) that are a core part of military ethics. However, I think that Ignatieff takes us somewhat deeper. His concept of ethical restraint – as the basis for distinguishing between ‘warriors’ and ‘barbarians’ – asks us not only to consider actions but also intent.

For example, to mount an attack of the kind launched by Hamas on October 7th – with the clear intention of massacring and mutilating innocent civilians – is to be distinguished from military action that tries, with utmost sincerity, to limit the harm caused to non-combatants. Hamas knows that Israel will always prevail in a direct contest of arms. However, following the logic of ‘asymmetric warfare’ it also knows that if it can goad Israel into fighting a ground war in areas heavily populated by civilians then the latter’s strategic strength can be broken in line with a loss of moral authority at home and abroad.

But how do you retain the status of a ‘warrior’ against an opponent who is deliberate in their use of the tactics of the ‘barbarian’ – and whose success absolutely depends on the wounding and death of the innocent?

This brings me to a third principle – familiar the world over. Expressed by the Chinese philosopher, Confucius, in the form, “Do not do to others what you would not have done to yourself”, the same principle (or a version of it) can be found in Jewish writings: “What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow-man. This is the entire Law, all the rest is commentary” (Talmud, Shabbat 3id – 16th Century BCE). The same sentiment can be found expressed in the Hadith – the sayings and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad who is recorded as having said, “Not one of you truly believes until you wish for others that which you wish for yourself.” In a further formulation of the same basic principle, the Prophet is also recorded as having said, “Do unto all men as you would wish to have done unto you; and reject for others what you would reject for yourself.” Such precepts reflect the essence of the ‘Golden Rule’.

What then might be the implications for the current conflict if this widely recognised principle was given practical effect? Even the most savage Hamas terrorist, with an abiding hatred of the Jewish people, will refuse to countenance that a child of his be raped and murdered in pursuit of his cause. Nor would the most zealous defender of Israel allow the bombing of a Jewish hospital – even if a Hamas command centre is located beneath the structure. One hopes that both would refuse to do to others what they would not have done to their own. In short, the exercise of moral imagination (in which you stand in the others’ shoes) as required by the application of the Golden Rule, should produce just the kind of ethical restraint that Ignatieff calls for.

So, why the carnage?

One explanation lies in the violation of the first principle outlined above. Antisemitism of the kind written into the core ideology of Hamas is fueled by an ancient denial of the full and equal humanity of the Jewish people. It is the same denial that made the Holocaust possible – with Nazi propaganda deliberately dehumanising the Jews by comparing them to vermin. Extermination was the logical next step once the vicious premise had taken root. And that is why it chills one to the bone to hear the Israeli Defence Minister, Yoav Gallant, say that in the latest conflict, “We are fighting against human animals”. Israel is the one nation on earth where we might have hoped such words never to be uttered.

If one seeks moral clarity, it will not be found in a flag around which one can rally. It will not be found in ties of blood or history alone. It lies in the conscious application of principle – without fear or favour, beyond the ties of kinship.

This is not to say that one must set aside emotion. It is proper to grieve for family and friends and those closest to you in belief and culture. But sympathy, grief, anger and a lust for revenge are not the ground on which judgement must rest.

An edited version of this article was originally published in the Australian Financial Review.

Image: Justin Lane / AAP Photo

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The erosion of public trust

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Climate + Environment

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccines: compulsory or conditional?

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff 2 NOV 2023

For many years, I took it for granted that I knew how to see. As a youth, I had excellent eyesight and would have been flabbergasted by any suggestion that I was deficient in how I saw the world.

Yet, sometime after my seventeenth birthday, I was forced to accept that this was not true, when, at the end of the ship-loading wharf near the town of Alyangula on Groote Eylandt, I was given a powerful lesson on seeing the world. Set in the northwestern corner of Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria, Groote Eylandt is the home of the Anindilyakwa people. Made up of fourteen clans from the island and archipelago and connected to the mainland through songlines, these First Nations people had welcomed me into their community. They offered me care and kinship, connecting me not only to a particular totem, but to everything that exists, seen and unseen, in a world that is split between two moieties. The problem was that this was a world that I could not see with my balanda (or white person’s) eyes.

To correct the worst part of my vision, I was taken out to the end of the wharf to be taught how to see dolphins. The lesson began with a simple question: “Can you see the dolphins?” I could not. No matter how hard I looked, I couldn’t see anything other than the surface of the waves and the occasional fish darting in and out of the pylons below the wharf. “Ah,” said my friends, “the problem is that you’re looking for dolphins!” “Of course, I’m looking for dolphins,” I said. “You just told me to look for dolphins!” Then came the knockdown response. “But, bungie, you can’t see dolphins by looking for dolphins. That’s not how to see. What you see is the pattern made by a dolphin in the sea.”

That had been my mistake. I had been looking for something in isolation from its context. It’s common to see the book on the table, or the ship at sea, where each object is separate from the thing to which it is related in space and time. The Anindilyakwa mob were teaching me to see things as a whole. I needed to learn that there is a distinctive pattern made by the sea where there are no dolphins present, and another where they are. For me, at least, this is a completely different way of seeing the world and it has shaped everything that I have done in the years since.

This leads me to wonder about what else we might not see due to being habituated to a particular perspective on the world.

There are nine or so ethical lenses through which an explorer might view the world. Each explorer will have a dominant lens and can be certain that others they encounter will not necessarily see the world in the same way. Just as I was unable to see dolphins, explorers may not be able to see vital aspects of the world around them—especially those embedded in the cultures they encounter through their exploration.

Ethical blindness is a recipe for disaster at any time. It is especially dangerous when human exploration turns to worlds beyond our own. I would love to live long enough to see humans visiting other planets in our solar system. Yet, I question whether we have the ethical maturity to do this with the degree of care required. After all, we have a parlous record on our own planet. Our ethical blindness has led us to explore in a manner that has been indifferent to the legitimate rights and interests of Indigenous peoples, whose vast store of knowledge and experience has often either been ignored or exploited.

Western explorers have assumed that our individualistic outlook is the standard for judgment. Even when we seek to do what is right, we end up tripping over our own prejudice. We have often explored with a heavy footprint or with disregard for what iniquities might be made possible by our discoveries.

There is also the question of whether there are some places that we ought not explore. The fact that we can do something does not mean that it should be done. Inverting Kant’s famous maxim that “ought implies can,” we should understand that can does not imply ought! I remember debating this question with one of Australia’s most famous physicists, Sir Mark Oliphant. He had been one of those who had helped make possible the development of the atomic bomb. He defended the basic science that made this possible while simultaneously believing that nuclear weapons are an abomination. He put it to me that science should explore every nook and cranny of the universe, as we can only control what is known and understood. Yet, when I asked him about human cloning, Oliphant argued that our exploration should stop at the frontier. He could not explain the contradiction in his position. I am not sure anyone has yet clearly defined where the boundary should lie. However, this does not mean that there is no line to be drawn.

So how should the ethical landscape be mapped for (and by) explorers? For example, what of those working on the de-extinction of animals like the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger)? Apart from satisfying human curiosity and the lust to do what has not been done before, should we bring this creature back into a world that has already adapted to its disappearance? Is there still a home for it? Will developments in artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, gene editing, nanotechnology, and robotics bring us to a point where we need to redefine what it means to be human and expand our concept of personhood? What other questions should we anticipate and try to answer before we traverse undiscovered country?

This is not to argue that we should be overly timid and restrictive. Rather, it is to make the case for thinking deeply before striking out, for preparing our ethics with as much care as responsible explorers used to give to their equipment and stores.

The future of exploration can and should be ethical exploration, in which every decision is informed by a core set of values and principles. In this future, explorers can be reflective practitioners who examine life as much as they do the worlds they encounter. This kind of exploration will be fully human in its character and quality. Eyes open. Curious and courageous. Stepping beyond the pale. Humble in learning to see—to really see—what is otherwise obscured within the shadows of unthinking custom and practice.

This is an edited extract from The Future of Exploration: Discovering the Uncharted Frontiers of Science, Technology and Human Potential. Available to order now.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY Dr Chloe Watfern Dr Priya Vaughan 30 OCT 2023

As part of their 2023 Ethics Centre residency, researchers Dr Chloe Watfern and Dr Priya Vaughan collaborated with researchers, artists and service providers to explore creative approaches to climate distress, and the ethics of care for place, self, and community in the context of ecological crisis.

Why is it that we are touched most by the things closest to us? Touched, as in, made to feel something strongly, to care in its meanings as both a verb and a noun – to feel concern for and to want to protect or nurture a child, a parent, a special place, a garden, or the bird out the window. It’s a question with an obvious answer. Because they are close. Because they can be felt, sometimes even touched.

Traditional moral theories require us to be unemotional, rational, and logical. For example, we are thought (or urged) to objectively calculate the extent to which our actions will lead to a good outcome for the greatest number of people. However, in the context of our daily lives, an ethics of care highlights the pull of relationships and feelings, like love and compassion, in our moral decision-making.

Tentacle, n.

Zoology: A slender flexible process in animals, esp. invertebrates, serving as an organ of touch or feeling. (Oxford English Dictionary)

The first recorded use of the word “tentacle” in the English language was in 1764, when A. P. Du Pont wrote that “the fingers, or tentacles, end in a deep blue.”

At about this time, the industrial revolution was just beginning in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States. Humans in these places gradually, and then very rapidly, moved away from producing things by hand. Coal, iron and water were the core elements of this rapid transformation in societies, extraction and exploitation its drivers. Today, we are at the coal face of its legacy.

Where will all this lead? To a deep blue? To a burning world? To unaddressable environmental collapse? To rubble, ash, and mud?

Care in an era of climate distress

Certainly, we know and feel that the living systems of the earth have been deeply compromised by human activities. This knowledge is a source of intense distress for many of us. At the same time, the collapse of systems creates new and ancient forms of distress, as homes and lives are destroyed or radically altered.

More and more of us care as more and more of us are touched by the effects of our collective actions: biodiversity loss, pollution, global boiling. What might we do with our bare hands, our sentient bodies, to make up for all the loss on our horizon? And where is the horizon anyway?

Professor Timothy Morton refers to global warming, like evolution, or relativity, as a “hyperobject”: something that is very difficult to comprehend using the cognitive tools that we humans have evolved to possess. Climate is everywhere and nowhere, in Antarctic ice sheets and cow belches, in bees and babies, in the cloud and the web, in bushfire smoke and too much (or not enough) rain on a tin roof.

Does Earth’s climate care that it is boiling? We don’t know, because we don’t know how to ask. We can only guess.

Stories of care

During our residency at the Ethics Centre in May 2023, we asked humans to share their stories of care. Colleagues, friends, family members, clinicians, artists, researchers, elders, and knowledge keepers each brought an object that connected to community, self, or planetary care in the climate crisis. These objects – a clay pot, a biodegradable bin bag, leaves collected on country, a handful of seeds – held and evoked memories of grief and loss, but above all, connection with humans, more-than-humans, and places. Close encounters filled with care.

Seeking a way to capture and share these memories, we asked these humans to help us create a tentacular creature: part cephalopod, part bird, part plant, part insect, part fungi, part human, part bacteria, part virus, part landscape.

For us, this tentacular creation was the perfect creature to hold stories of care, responsibility, hope, and fear in the context of our precarious and precious world.

Neither and both human and animal, nature and artifice, Tentacular collapses fictious binaries that have, historically, enabled the climate crisis to be seen as a problem with ‘nature’, rather than the total phenomenon it is.

Each tentacle of this collective artwork reaches outwards, seeking connection and offering stories that speak to the ways we might care, in responsible and responsive ways, for ourselves, each other, and the wounded world. Here, we share some evocative snippets from the stories of care that each person offered:

Gadigal, Bidjigal and Yuin elder Aunty Rhonda Dixon–Grovenor grew up being taught to respect and care for country. She tells people “If we are in nature and enjoy it and care for it, then it nourishes us… Care is a relationship, it’s a two-way, it’s not just one person dominating.”

“Care is a relationship, it’s a two-way, it’s not just one person dominating.” – Aunty Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor

Academic Dr Barbara Doran reflects on the tuition of a beehive: “The bees connected me to a more nuanced relationship with nature… Now, I’m more aware of rain, of flowering patterns, of birds: the ecosystem is amplified in my eyes. But after the fires, I’ve noticed an echo-effect. They have been splitting more than they usually do. This year is the first season with no honey. I’m noticing these resonant patterns in a climate changed world. The hive is my teacher, healer and sharpener of antennas.”

Psychotherapist and Group Facilitator at We Al-li, Georgie Igoe asks us to consider threshold experiences: “For me, care means sitting with discomfort and uncertainty, opening ourselves up to the unknown – in the muck, in the grief, not sidestepping it but acknowledging its power.”

Installation artist and theatre-maker Brownyn Vaughan shares the wisdom of her favourite writers and of her favourite swimming place: “The Mahon pool brought me up, it’s my go-to-place… Professor Astrida Neimanis tells us we must stop trying to ascend and transform. Instead, we must submerge, become part of the water.”

Artist-survivor, and lived experience advocate, Lea Richards, mourns and advocates for the mountains: “Snow melt is mountain’s blood. I weep for the glaciers, so far from arid Australia, yet not separate. I imagine connections to those vanishing snows– a flow of water between us. If I conserve this precious blood, can I tend those far places, postpone the melting?”

Embedded in many, perhaps all, of these stories is a conviction that we need to, as Bronwyn said, submerge, to acknowledge our place in the meshwork of the world, and in so doing, to learn with and from the environment. This means burying ego, rejecting a hierarchy where humans are at the apex, and attending in quotidian ways to what is happening to us and around us. Let’s become like tentacles, feeling our way into a better relationship with the world we care so much about.

Tentacular, as part of the exhibition: Care is a Relationship is on display at UNSW Library until 17 November, 2023.

Find out more about The Ethics Centre Residency Program.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Climate + Environment

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Plato’s Cave

BY Dr Chloe Watfern

Dr Chloe Watfern works across the social sciences, humanities, and creative arts to tackle the big and interconnected challenges of our time, from social inclusion and mental health to climate change. She is currently working at Black Dog Institute (UNSW) and Maridulu Budyari Gumal SPHERE (Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise)’s Knowledge Translation Strategic Platform.

BY Dr Priya Vaughan

Dr Priya Vaughan takes an interdisciplinary, and participatory approach to health research, utilising arts-based and socially informed methodologies, knowledge translation (KT) strategies, and interventions to learn about and support mental health and wellbeing. She is currently working at Black Dog Institute (UNSW) and Maridulu Budyari Gumal SPHERE (Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise)’s Knowledge Translation Strategic Platform.

Israel or Palestine: Do you have to pick a side?

Israel or Palestine: Do you have to pick a side?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 27 OCT 2023

We are inclined to pick a side in complex conflicts, but doing so can diminish our ethical point of view.

In the early hours of 7 October 2023, Hamas launched a barrage of rockets from Gaza into Israel while armed terrorists crossed the border and began a rampage of death and destruction targeting civilians, including children. In the days that followed, Israeli forces retaliated by blockading Gaza, cutting off food, electricity and water supplies, and began bombarding the densely populated city, killing thousands of Palestinian civilians, including children.

When our news screens are filled with footage of such horrors, our moral minds cry out for justice. But justice for whom?

One of the quirks of our moral minds is that we tend to see the world in terms of black and white or good and evil. If we hear about a heinous or unjust act, our sympathies go out to the victims while outrage inspires us to want the perpetrators to be punished. This sorts the world into two categories: the wronged, who deserve sympathy and protection, and the wrongdoers, who are morally diminished or even dehumanised.

Another quirk of our moral minds is that we struggle with ambivalence, which is the ability to see something as being both good and bad at the same time. Once someone – or a group – are painted as the wronged, it’s difficult to also perceive them simultaneously as being wrongdoers in some other capacity. Attempting to do so creates an uncomfortable state of dissonance, and the easiest way to resolve it is to dismiss the troubling thought and collapse things back into black and white.

On top of this we have our personal connections and affiliations, or a sense of shared identity that can cause us to feel solidarity with one side rather than the other. This in-group solidarity is then reinforced through shared expressions of grief and outrage. It is also policed, with any signs of sympathy for the “other side” drawing stiff rebuke.

This is all natural. It’s how our moral minds are wired. So, it’s no surprise that in the case of the Israel-Palestine conflict, many people have already picked a side. But just because it’s a natural inclination doesn’t mean it’s always a healthy one.

Picking a side can shrink our view, making us see the world through that side’s ethical lens and dismissing other possibly valid perspectives.

This is particularly apparent when we’re faced with gaps in the information we receive – as we often are during times of conflict. We tend to fill ambiguity with our own biases, and we seek out information to reinforce our view while discounting evidence to the contrary.

Picking sides can also prevent us from seeing the bigger ethical picture. And in the case of the conflict between Israel and Palestine, the bigger picture is a long history laced with ethical complexities.

However, there is another way. It requires us to acknowledge, but not necessarily follow, our moral intuitions, and instead step back to take a more universal ethical point of view. This is not the same as a neutrality that is indifferent to the claims of either side or to questions of right and wrong. It is taking the side of principle, which is a basis by which we can judge all parties.

Justice for all

Most ethical frameworks offered by philosophers are universalist, in the sense that they apply equally to all morally worthwhile individuals in similar situations. So, if you believe that it’s wrong to kill a particular individual because they’re an innocent civilian, then you should also believe that it’s wrong to kill any individual who is an innocent civilian.

You might justify that in consequentialist terms, such as by arguing that killing innocent civilians causes undue and irrevocable harm, and that the world is a better place when civilians are protected from such harm. You could equally justify it using a rights-based ethics, such as by arguing that all people have a fundamental right to life and safety.

While philosophers have a variety of views on which specific ethical framework or universal principles we ought to adopt, there are some principles that are widely accepted, with many being coded into the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These include things like a right to life, liberty and security of person, a right to freedom of movement within the borders of one’s state, and that people shall not be arbitrarily deprived of property, as well as a right to the free expression of one’s religion.

The virtue of taking such a principled approach is that is gives us a bedrock upon which we can base our judgements of any action, agent or government. It promotes a sympathetic stance towards all suffering, and aims us towards justice for all, without shying away from condemning that which is harmful or unjust.

It might challenge our partisan feelings that favour the interests of one side over the other, but it urges us to condemn wrongdoing on any side, such attacks targeting civilians or waging war without ethical constraint.

A principled perspective also enables us to navigate complex ethical issues, such as saying that the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land might be unjust, but that it shouldn’t justify Hamas attacking civilians. Or that Hamas’s attacking civilians is clearly morally repugnant, but that shouldn’t justify the collective punishment of Gazans by Israel. And it can allow us to assert that Israel might have a right to defend its territory and citizens from attack, but it – indeed, all parties – must adhere to just war principles, such as proportionality and distinguishing between enemy combatants and civilians. And it ought to reinforce our commitment to seeing a lasting peace in the region, which will inevitably require some compromises on both sides.

Of course, even if everyone agreed on the same set of principles, there will still be substantial differences in interpretation or points of view. A principled stance must also acknowledge that there are fundamental incompatibilities between the interests and demands of both sides that no single ethical framework will be able to resolve without some kind of compromise. For example, when both sides claim certain sites as sacred, and demand exclusivity, there is no way to resolve that without compromise that will be deemed unacceptable to at least one side. However, such uncertainties and complexities don’t undermine the fact that the same universal principles ought to apply to all people involved.

Choosing to side with ethical principle rather than one side or the other is not without its challenges. It forces us to push back on some of our deep moral intuitions and sit with ambivalence and ambiguity. We might be admonished by both sides in the conflict for not backing all their claims, or called a traitor for criticising them. However, the strength is that we can respond to each of these challenges by resorting to the universal principles, compassion and desire for justice that underpins our views on both sides of the conflict.

While the internet and media landscape seem to urge us to take sides in any conflict, it is entirely possible – and often wise – to step back and apply a broader set of principles rather than fall in with a particular partisan perspective. Adopting such a principled stance doesn’t require that you have all the solutions to the conflict, it is sufficient that you have good reason to wish for a just and peaceful solution for all involved.

Image: AAP Photo / Erik S. Lesser

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights