How far should you go for what you believe in?

How far should you go for what you believe in?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Cameryn Cass 28 MAR 2023

Do we all have a right to protest? And does it count if it doesn’t result in radical change? Grappling with its many faces and forms, philosopher Dr Tim Dean, and human rights lawyer and chair of Amnesty International UK, Dr Senthorun (Sen) Raj unpack what it means to ethically protest in our modern society.

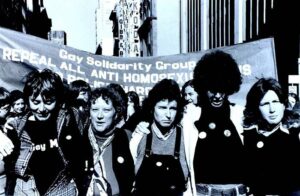

In the wake of 2023 World Pride and Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, Raj and Dean reflect on a fundamental question present in all protest: What is it you’re protesting?

The first challenge is in agreeing on what the problem is: Is it freedom we’re fighting for? Equal rights? Sustainability? From there, you’ve got to expose the fault to enough people who are motivated to join in on the resistance.

“We can hope for a better future, but is it enough to just hope?” – Sen Raj

Even if a protest is small in numbers, it can be lasting in impact; just consider Sydney’s first Mardi Gras. It was a relatively modest event that’s now grown to nearly 12,500 marchers and 300,000 spectators. But it began with a fraction of those numbers. Late in the evening on 24 June 1978, a group marched toward Hyde Park with a small stereo system and banners decorating the back of a single flat-bed truck, like a scaled-down parade float. The march intentionally coincided with anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall riots, which remains a symbol of resistance and solidarity among the gay and lesbian community. As the night progressed, police confiscated the truck and sound system. Eventually, 53 people were charged – despite having a permit to march – after they fought back in response to the police violence. To this, Ken Davis, who helped lead the march, said, “The police attack made us more determined to run Mardi Gras the next year.”

“Protest” has multiple meanings

A meaningful protest doesn’t have to be major like Mardi Gras. Sometimes, protests by brave individuals alone have extraordinary impacts.

Thích Quảng Đức, a Mahayana Buddhist monk, famously burned himself to death at a busy intersection in Vietnam on 11 June 1963. In the height of the Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam, Quảng Đức performed this self-immolation to protest Buddhist persecution. The harrowing photo of him calmly seated while burning alive touched all corners of the globe and inspired similar acts of sacrifice in the name of religious freedom.

Protests need not be so drastic, though, to have an impact. On 16 December 1965, a group of American students protested the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands with peace signs on them to school. When administrators told the students to remove the bands and they refused, they were sent home. Backed by their families, the Iowa school’s barring of student protest reached the Supreme Court. The famed Tinker v. Des Moines decision held that students don’t “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

The Tinker case is proof that protests, no matter how minor, can give rise to reformation. But we shouldn’t enter all protests with an expectation of radical change. Dean and Raj agree the assumption that transformation is the mark of a successful protest ought to be re-examined, as a clear outcome isn’t the only metric of success. As Raj said, “There is a tendency at times to assume that a protest will have a very clear message – a defined endpoint or outcome.”

Though progress might prove slow, it’s progress, nonetheless. We should act with the intention of spreading a message and entering a larger conversation that may or may not modify the status quo. Does a protest count for nothing if it doesn’t result in sweeping change? Is it not enough to ignite the spirit of defiance in just one soul? Or to simply express your authentic self even if it has no impact?

“For me, being queer, being trans, being part of a community that is marginalised and stigmatised for who you are or what you do, in itself, is a form of protest.” – Sen Raj

For members of the LGBTQIA+ community, Raj highlights how, “by virtue of existing, these individuals are being policed.” He says, “For me, being queer, being trans, being part of a community that is marginalised and stigmatised for who you are or what you do, in itself, is a form of protest.” So by refusing to conform and loving who they want, not holding themselves to gender or sexual norms, LGBTQIA+ people protest every day. It’s not a large mass gathering, but it’s a kind of protest, nonetheless. Authentic expression begets liberation; we ought not trivialise the importance of any protest, big or small, as it takes real courage to take part in something larger than yourself.

Does violence have a place in protests?

Just as protests can manifest in many forms, they can also be carried out differently.

Because tragedy and injustice are what usually catalyse protests, they’re often charged with strong – and sometimes overwhelmingly negative – emotions. It’s no surprise, then, that some protests turn violent.

But is violence ever permissible in a protest? And if police instigate it, do protesters have a right to protect themselves?

During the racial tensions in 1960s America, many protests ended in violence, especially by police. Images capture the savage behaviour in Birmingham, Alabama, where police unleashed high-powered hoses and dogs on Black protesters. In spite of such violence, they had no space to defend themselves; fighting back meant certain arrest. As Dean and Raj detailed in the discussion, sometimes authorities use this tendency towards self-defence to provoke violence and thus justify further oppression. Race riots persist in America as the fight against systematic racism and police brutality continues. The Black Lives Matter movement (BLM), founded in 2013 and popularised after a policeman wrongfully killed George Floyd in 2020, continues the fight for Black rights.

The fragility of protesting

The right to protest isn’t guaranteed and must be protected. In the absence of protest, the government and other institutions could operate unchallenged.

In Hong Kong, China enacted a new national security law in 2020 that’s a major barrier to protesting. Already, hundreds of protesters have been arrested. On paper, the law protects against terrorism and subversion, but in practice, it criminalises dissent. In the absence of protest, the powerful can ignore and silence the concerns of the masses. If a system is broken, binding together and protesting is an essential step in fixing it. Without protests, a broken system will remain broken.

“That’s what gives rise to protests, is that refusal. That refusal to allow for social or political worlds that oppress you to continue unchecked, and to say ‘Enough’.” – Sen Raj

Anti-protest laws aren’t a uniquely Hong Kong phenomenon. In April 2022, the New South Wales government passed more stringent legislation that punishes both protests and protesters that illegally dissent on public land. By blocking protests that prevent economic activity, critics say it’s an extremely undemocratic measure and threatens protests at large. Plus, it creates a hierarchy among protests, where some are viewed as valid while others aren’t. This raises the larger question of whether it’s the government’s place to determine which protests should be allowed. Does asking permission to protest do an injustice to the demonstration?

A way forward

It’s important to note that there’s no one way to protest. The textbook protest of a group of angry, fed-up citizens waving signs and shouting in the streets doesn’t always hold true. And so we’ve got to remember that protest need not look a certain way or foster radical change to be successful. It need not be a grandiose display of floats and intricate costumes parading down Oxford Street, like today’s Mardi Gras; sometimes it’s enough for one person to speak their mind.

Raj reminds us that protest ought to be messy, joyous and painful but should include care, respect and solidarity. He encourages us to abandon the stereotypical depiction of protest and embrace the possibility of many protests. It’s limiting to try and definitively define what it means. “Protest” is encapsulating of so many movements, minor and mammoth. Instead of trying to box it into one definition, let’s find beauty in its vastness.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

BY Cameryn Cass

Cameryn Cass is a curious writer and an editor-in-training who studied at Michigan State University. Her primary focus is environmental storytelling, as she deeply loves the natural world and intends to use her voice to defend it. Outside of work, she loves to hike, rock climb and practice yoga.

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan 21 MAR 2023

Parental leave policies are designed to support and protect working parents. However, we need to exercise greater imagination when it comes to the roles of women, family and care if we are to promote greater social equity.

In October 2022, prime minister Anthony Albanese announced a major reform to Australia’s paid parental leave scheme, making it more flexible for parents and extending the period that it covers. Labor’s reforms are undoubtedly an improvement over the existing scheme, which has been insufficient to address gender-based disadvantage.

Labor’s new arrangement builds on the current Parental Leave Pay (PLP) scheme. This entitles a primary carer – usually the mother – to 18 weeks paid leave at the national minimum wage, along with any parental leave offered by their employer. It runs in parallel to the Dad and Partner Pay scheme, which offers “eligible working dads and partners” two weeks paid leave at the minimum wage. Recipients of this scheme are required to be employed and recipients of both need to be earning less than ~$156,000 annually.

Albanese’s announced expansion of the PLP will increase it to 26 weeks paid leave by 2026, which can be shared between carers if they wish. Labor claims that this will offer parents greater flexibility while retaining continuity with the existing scheme.

Labor’s new scheme is an improvement over the older arrangement, but is it enough to move society closer to the goal of social equity? To do so, we need to do more to reduce the marginalisation of women economically, in the home and in the workplace, and to expand our imagination when it comes to parenthood and caring responsibilities.

Uneven playing field

Gender-based disadvantage is a global occurrence. Currently, being a woman acts as a reliable determining factor of that person’s social, health and economic disadvantage throughout their life. Paid parental schemes are one type of governmental policy that can facilitate and encourage the structural reform necessary to address gender-based disadvantage. Certain parental leave policies can help reconfigure conceptions about parenting, family and work in ways that better align with a country’s goals and attitudes surrounding both gender equity and economic participation.

Paid parental leave schemes that provide adequate leave periods, pay rates, and encourage shared caring patterns across households, can fundamentally impact the degree to which one’s gender acts a significant determining factor of their opportunities and wellbeing across their lifetime.

The Parenthood, an Australian not-for-profit, emphasises that motherhood acts as a penalty against women, children and their families. This penalty is experienced acutely by women who have children and manifests as diminished health and economic security, reducing women’s social capacity to achieve shared gender equity goals. Their research highlights that countries that offer higher levels of maternity and paternity leave, such as Germany, in combination with access to affordable childcare results in higher lifetime earnings and work participation rates for women.

Australia’s existing PLP scheme, on the other hand, works to both create and foster conditions that reduce the capacity for women to achieve the same social and economic security as their male peers. It hugely limits women’s capacity to return to work, to remain at home, and to freely negotiate alternative patterns of care with their partners. This in combination with a growing casualised workforce who remain unable to access adequate employer support emphasises the need for extensive policy amendments if we hope to realise our goals of social equity.

Labour’s proposed expansion incrementally begins to better align the PLP with the goals set forth by organisations like The Parenthood.

Providing women and their families with more freedom to independently determine their work and social structures may mark the beginning of a positive move against gender-based disadvantage. However, the proposed expansion is not a cure-all for a society that remains wedded to particular conceptions of women, parenting, and labour more broadly.

The working rights of mothers

We can see how disadvantage goes beyond parental leave by looking at how mothers are treated in workplaces such as universities. Dr Talia Morag at the University of Wollongong advocates for the working rights of mothers employed within her university. Prior to Albanese’s announcement, Morag emphasised the cultural resistance, or rather a lack of imagination, when it came to merging the concept of motherhood with an academic career.

Class scheduling, travel funding and networking capacities are all important features of an academic career that require attention and reconfiguration if mothers, especially of infants and young children, are to be sufficiently included and afforded equal capacities to succeed in university settings.

Even under expanded PLP schemes, mothers who breastfeed, for example, face difficulty when returning to work if they remain unsupported and marginalised in those workplaces. As Morag emphasises, many casual or early-career academic staff are unentitled to receive government PLP or university funded parental leave.

Critically, the associations between being woman and being taken to be an impediment to one’s workplace is not an issue faced solely by those who become mothers.

As Morag remarks, “it does not matter if you are or are not going to be a mother, you will be labelled as a potential mother for most of your career. And that will come with expectations and discrimination.”

The gender-based disadvantage emergent from these cultural associations will remain if broader cultural change is not sought alongside expanded PLP schemes.

Expanding our imaginations as to how current notions of motherhood, family and caring patterns can look will require the combined efforts of expanded PLP schemes and the creation of more hospitable working environments for parents. Women may remain being seen as potential mothers and potential liabilities to places of work, however this liability may slowly begin to shift.

We historically have, and seemingly remain, committed to reproducing our species. This means we continue to produce little people who grow up to experience pleasure, pain, and everything in between. If we also see ourselves as committed to managing some of that pain, to expanding the opportunities these little people get, as well as reducing how gender unfairly determines opportunity on their behalf, we will require policies that assist parents to do so.

Affording families this chance benefits not only mothers, or parents, but also their children, their children’s children, and all others in our communities. Granting parents the capacity to choose who works where and when can help us, incrementally, along a long path to a world that is perhaps more dynamic and equitable than we can even begin to envision.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

5 ethical life hacks

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Should I have children? Here’s what the philosophers say

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 3 MAR 2023

The undead are everywhere. It’s not just that our culture is obsessed with zombies, from The Walking Dead to The Last Of Us. It’s that our cultural discussions are zombies themselves – they just won’t die.

We go over the same old arguments time and time again, to no seeming progression or end. Just take the cultural discussions around depiction and endorsement where the lines have been drawn in the sand.

For those on one side of the line – the instigators of this particular debate – artists who depict monstrous acts are seen to be agreeing with these acts. The mere depiction of violence, for instance, is seen as a kind of thumbs up to that violence, tacitly encouraging it.

On this view, artists are moral arbiters, and the images and stories that they put out into the world have a significant, behaviour-altering effect. Depicting criminals means “normalising” criminals, which means that more viewers will believe that criminal acts are acceptable, and, theoretically, start doing them.

This view has a historical precedent. Art has long been political, used by states and religious groups in order to provide a form of moral instruction – consider devotional Christian paintings, which are designed to exhort viewers to better behaviour.

Certainly, there are still artists and artworks with a pointedly ethical and political mode of instruction. From government PSAs that borrow storytelling techniques that artists have used for years, to the glut of Christian-funded films like God Is Real, art objects have been designed as transmission devices for a particular point of ethical view. Even Captain Marvel, another in a seemingly unending glut of superhero movies, was created in partnership with the airforce, and depicts the military in a childishly positive light.

But acting as though all art has this moral framework – that everything is a form of fable, with a clear ethical message – is a mistake. Moreover, it elevates a discussion about art beyond what we usually think of as aesthetic principles, and into political ones. It’s not just that the instigators who view all art as essentially and simply instructional worry we’re getting worse art. It’s that they worry we’re getting more dangerous art.

In just the last 12 months, Martin Scorsese has been condemned at least three times in some circles of the internet for glorifying depravity with his films about criminal underbellies.

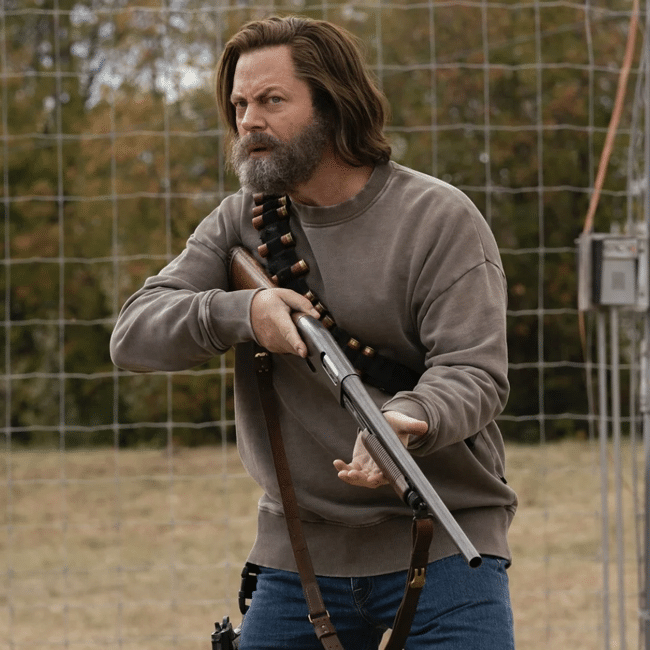

But the argument really saw its time in a sun that won’t set with the release of the bottleneck episode of The Last of Us, a much heralded – and deeply contentious – piece of television.

Fungal Zombies And Queer Representation

In the episode, Parks and Recreation’s Nick Offerman and The White Lotus’ Murray Bartlett embark upon a queer romance while the world ends around them. Though highlighted for its sensitivity in some corners of the discourse, the episode received significant pushback.

For writer Merryana Salem of Junkee, the episode was an example of “pinkwashing”, due to the fact that the characters value “individual liberty over community good.” As in – they try to survive during an apocalypse. Salem criticises the show for depicting queer characters looting and pillaging, rather than sharing resources. By aligning queer representation with selfish behaviour, Salem appears to be arguing that the show will platform and perhaps normalise libertarian values of the self as important above all others.

“Far from framing this attitude as negative, a song plays cheerily over Bill hoarding, looting resources, and setting up security systems that would prevent anyone in the immediate area from even using the electricity in the local plant”, Salem writes.

The argument here is simple. One act is shown onscreen instead of another. That is a choice. The choice, combined with the aesthetics around it – cheery music – means that this choice is designed to impress upon the audience the admirable nature of the character, even as he does less than admirable things.

What such an argument precludes, however, is the complexity inherent in the episode. The Last of Us’ showrunner, Craig Mazin, may not be pointing at good and bad as directly as his critics assume. Bill is a man trying to carve out love and life under impossible circumstances. In an ideal world, he wouldn’t be hoarding resources. In an ideal world, he would be living quietly, in a community. He doesn’t want to make do in the middle of a zombie outbreak.

The beauty of the episode, then, is the way it makes a case for the power of an easy love formed under uneasy circumstances. Bill’s flawed because he’s been made that way by an outbreak of, ya know, fungus zombies. And yet still he finds some crooked form of redemption in the arms of another.

That’s what is missing from so many of these debates about depiction versus endorsement – nuance.

Good storytellers don’t depict flatly. They depict with complexity. With differing shades of light and dark. And so their art should be analysed on those merits, with criticism that is itself complex.

But more than that, we need to ask ourselves, finally, whether depicting reprehensible acts onscreen really has the effect that these critics assume it does.

The Return Of The Big Bad

Take some of the most reprehensible people on television. Walter White of Breaking Bad. Tony Soprano of The Sopranos. Even Don Draper of Mad Men. These men, who washed over our screens during the start of the Golden Age of Television, do bad things.

More than that, they get rewarded for them. Tony is lavished with success of all forms – money, power, opportunity. Walter finds, through drug-dealing, a new level of self-confidence and authority. Don never gets a traditional comeuppance, unless you take the constant unease in his soul as a form of comeuppance.

These characters are explicitly rewarded – in some ways – for their immorality. They get away with it. Even Tony, whose fate is hinted at but never explicitly shown, gets a moment of peace before he goes. Don’s sitting there with a big old grin on his face the last time we see him. And sure, Walter gets snuffed out, but on his own vicious terms.

And so what? Are any of the creators behind these anti-heroes really suggesting that we should turn to crime or adultery? If they are, then they are not artists – they are salesmen.

Art is better when we treat it as nuanced, complex depictions that leave it to us to do the work of untangling.

Indeed, through immorality, these characters suggest that the only thing worse than these flawed and difficult characters is the world around them – the world that rewards them. It’s not Don that’s the isolated problem, cutting a swathe of heartbreak and cashing a big old cheque. It’s that the structure around him is misogynistic and capitalistic. He is the perfect product of his era. And the depiction of his moral crimes isn’t meant to encourage us to applaud those crimes. It’s meant – at least on one interpretation – to make us question the whole system that props us up.

It’s a mistake to hanker for art that only operates in one moral mode; that punishes the wicked, and celebrates the innocent. Not even fairy tales are that simplistic. We live in an era in which even our zombie TV shows are filled with nuance and complexity. Let’s engage in discourse worthy of that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Donation? More like dump nation

Donation? More like dump nation

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + Wellbeing

BY Amal Awad 27 FEB 2023

In the desire to clean up our living and mental spaces, we need not create a costly mess for charitable organisations receiving our donations.

Several years ago when I was producing for radio, I found myself knee-deep in the topic of minimalism. I was fascinated by the concept: living with a minimal number of possessions, replacing rather than accumulating, being ‘timeless’ rather than at the mercy of trends. At the forefront of the movement were Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus, aka The Minimalists, whom The New Yorker called ‘Sincere prophets of anti-consumerism’. They rose to fame with documentaries, a podcast and a best-selling book, all of which promoted this ‘minimalist lifestyle’.

A minimalist approach does not preclude you from purchasing the latest smartphone, it resists desiring that smartphone, which, like most on-trend technology, will either get superseded by a newer version within a year, or break the moment its two-year warranty has expired. (Remember your childhood TV that worked for 17 years?)

I interviewed Nicodemus and easily understood how his austere approach to housekeeping might have its appeal. What would it be like to not be weighed down by your possessions? To actually derive full use out of what you already owned? To simply not want the newest shiny thing?

At the heart of this approach is a mental philosophy that fuels a mindset, not just a way of life. Being a minimalist will mean you’re not part of the problem in what seems to be an ever-expanding consumerist wasteland. You’re better for the environment because you don’t accumulate. You’re not someone who, in the process of divesting yourself of unneeded possessions, overloads your local op shop because you have five different versions of a favourite item.

While the ability to not accumulate possessions may be harder to achieve for most people, as each new year rolls in with the proclamation of a ‘New Year, New Me’, we tend to become minimalists.

In a fever, we rule out bad habits and embrace healthy ones. Invariably, this involves some level of decluttering because we acknowledge that we are wasting money on things we don’t need.

And this is why it’s not uncommon to drive past a Vinnie’s in January and see half-opened bags of donations strewn across the pavement.

That ardent desire to strip away the baggage in our lives ends up becoming someone else’s problem when we dump donations, rather than engaging with charitable organisations and op-shops directly.

Unfortunately, this is a cumbersome, costly problem for the charitable organisations receiving these donations. Rather than an orderly, well-packed offering of useable items, charities are reporting the prevalence of irresponsible offloading of unusable items. As Tory Shepherd reported for The Guardian, “Australian charities are forking out millions of dollars to deal with donation ‘dumping’ at the same time that they are seeing rising demand for their services ‘as the cost-of-living crisis bites’”.

Not for the first time, we are seeing op shops plead with their local communities to not dump and run, leaving behind what is often rubbish, or items that the shop cannot accommodate, such as furniture. Following Covid lockdowns, we saw a similar phenomenon as people took stock of their lives and possessions—and left it to charities to take care of their unwanted items. The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) and Charitable Recycling Australia are pushing this message of responsible donating.

As a deeply consumerist society, we’re at the mercy of goods that are not built to last.

There is a need for donations; organisations like Vinnies are clearly welcoming of reusable, recyclable goods that can be repurposed. However, instead of owning the act of throwing something away, we might pass on the responsibility by giving it away and making it a charitable act. There are deeply-felt financial and practical impacts on these organisations when they have to clean up the mess of people who don’t take the time to sort through their possessions, or who are careless in how they deliver their donations. The resounding advice is that if it’s something you’d give to a friend, it’s suitable for a donation.

Not everyone can afford goods made of recyclable or sustainable material. But we can try to create a new way forward. We can reconsider our approach to ownership and divestment; buy what we need and try to purchase higher quality, sustainable goods whenever possible. We can also appeal to businesses to enact more sustainable practices. We can lobby local councils and government.

In the meantime, while it’s a positive that we don’t want to just throw things out, it does not take much to do a stocktake before offering up donations: is what am I giving away something I would give to someone I care about? Is it in working order? For large items, check with your op shop or organisation before delivering them. Don’t leave items in front of a closed shopfront. Don’t treat charities like a garbage dump.

There is tidying a la Marie Kondo but then there is medically-reviewed physical decluttering that research suggests is good for our mental health. Even digital decluttering can have a positive impact on our productivity. But it’s worth considering, when we divest ourselves of unwanted goods, whether we are making sustainable donations or trashing items simply to upgrade.

If we can accept that decluttering is good for us, does that not also suggest that having cleaner spaces with fewer possessions is a better way to live? Perhaps a more worthy and sustainable goal is to take some cues from the minimalist mindset. I’m all for annual purges but even better would be to not need to declutter in the first place.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

What your email signature says about you

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Big thinker

Climate + Environment

7 thinkers improving our ethical understanding of the environment

The Constitution is incomplete. So let’s finish the job

The Constitution is incomplete. So let’s finish the job

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 17 FEB 2023

On July 9, 1900, Royal Assent was given to the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900. This act made provision for a series of sovereign colonial states to come together and form “one indissoluble federal commonwealth”. Section 6 of the act defines the states. It lists by name an initial seven colonies – and allows for others to be admitted at a later time.

“Hang on,” you might object, “everyone knows that there were, and are, only six states. What’s this nonsense about there being a seventh?”

Well, the framers of the Constitution wanted to recognise all of the smaller sovereign states that might make up the larger whole. So, the list included New Zealand. Indeed, when in 1902 the Commonwealth Parliament determined who could vote in federal elections, it singled out New Zealand’s Maori people for inclusion – while excluding the vast majority of Australia’s own Indigenous peoples.

This is breathtaking.

If you are wondering what any of this has to do with the proposed referendum about the Voice to Parliament, then consider this.

Those who put together the Constitution never finished the job. They left out those with the greatest claim to sovereignty of all.

Now we have the chance to finish the job – to make our Constitution whole.

We are on the cusp of resolving one of the most profound questions we face as citizens: will we afford constitutional recognition to the descendants of those First Nations peoples whose sovereignty was ignored by the European colonists?

A number of arguments have been put forward as reasons to oppose constitutional recognition of First Nations peoples in the form of a Voice to Parliament. Those arguments include that a Voice:

- Weakens First Nations’ claims to sovereignty.

- Will not lead to a tangible improvement in the lives of Indigenous peoples.

- Is “racist” and undemocratic in that it affords a privilege to one “race” over all others.

- Will increase legal uncertainty – especially when interpreting the Constitution.

In every case, framing the debate in terms of sovereignty helps us to see why these objections, while sincerely made, are not well founded.

It is feared, by some, that constitutional recognition will weaken the claims to sovereignty made by First Nations peoples. However, the Australian Constitution specifically preserves the sovereignty of each of the states that were recognised at Federation. Furthermore, all of their state laws remain intact. The only effect of the Constitution is to render state laws inoperative to the extent that they are inconsistent with valid Commonwealth legislation. Rather than destroying sovereignty, the Constitution recognises and preserves it – even as earlier laws become attenuated.

It might be objected that the First Nations of pre-colonial Australia were not “sovereign states”. However, they meet all of the accepted criteria. They may have been small – but size of territory or population does not matter (think of Monaco, Liechtenstein, Tuvalu and so on – all states). The First Nations had clearly defined borders. They had distinct laws – and processes for their enforcement. They traded – domestically and internationally (for example, centuries of trade between the Makassan people of modern Indonesia and the Anindilyakwa people of the Groote Eylandt archipelago, and others). They fought wars over people and resources and to defend their territory. All of this was anticipated by British law and policy. It was only blind ignorance and prejudice that stopped the colonists recognising the sophisticated array of states they encountered here.

A second objection is that constitutional recognition will do little or nothing to “close the gap”. Surely, Indigenous peoples have a far better idea of what is needed to address the enduring legacies of colonisation than do the rest of us. Certainly, they could not do a worse job than we have so far. So, I believe a Voice to Parliament will make a positive difference in the material circumstances of First Nations peoples. However, while important, this misses the point.

Imagine someone heading out into remote Queensland in 1899 – to tell the people living there that remaining as a crown colony might lead to better outcomes in the future. There would have been a riot in response to the suggestion that Queensland should be left a colony while the rest of the colonial states formed a federation. Even the West Australians decided to join – not because Federation guaranteed a better outcome for the people of each state, but because of the dignity it conferred on citizens of the newly established nation. It’s the same for those forgotten or ignored when the first round of Constitutional crafting was done.

The next “bad” argument claims that the creation of a Voice confers a benefit on one group of people because of their “race” – and that to do so is racist and undemocratic. Once again, the argument fails to take account of First Nations peoples as members of sovereign states. Those states existed – certainly in Natural Law (and probably more formally) for centuries prior to colonisation. The citizens of those states were exclusively Indigenous – not as a matter of racial policy but as a simple fact of history. The same would have been true of other ancient states in other parts of the world which, at one time or another, would have been made up of groups of people related through kinship and so on.

So, if we see our late recognition of the peoples of the First Nations through the lens of sovereignty and citizenship, there is necessarily going to be overlap between that citizenship and membership of a distinct group of related people.

This is not about privileging one “race” over another. It is simply acknowledging the fact that the citizens of the First Nations that we hope to recognise are all bound by a kinship grounded in deep history.

Finally, we come to the argument that an amendment to the Constitution will cause legal uncertainty – with the High Court spending wasted hours in interpreting the new provisions of an amended Constitution. If this is a valid reason for not amending the Constitution, then it is better that we should not have had a Constitution at all. Every clause in the Constitution of 1900 is open to interpretation by the High Court. Indeed, the High Court has spent a vast amount of time interpreting provisions (especially concerning the valid powers of the commonwealth). So, yes, an amendment might lead to disputes in the Federal and High Court. So what? That happens every day in relation to sections of the Constitution that are more or less taken for granted.

Finally, I am happy to see a decreasing number of people are arguing that the voice will be a “third chamber” of parliament. It will not. The Voice will be able to make representations and to advise – using whatever mechanisms the Commonwealth Parliament prescribes. The Voice will decide nothing on its own. It cannot veto any act of parliament or decision of government.

First Nations peoples have asked for something very modest. They want to be recognised. They simply want to be heard in relation to matters that have a direct bearing on their lives.

Our Constitution is a pretty good document. However, its authors left something out. While recognising the sovereignty of all others (even Fiji was in the mix for a while), they overlooked those with the best claim of all.

Imagine a fence made without a gate, a car without brakes and a cake without icing. They’ll work well enough. But they’re not complete. That’s the deficiency in our Constitution – it also works well enough, but it is not complete.

Let’s recognise what was forgotten. Let’s finish the job.

This article was first published in The Australian.

For everything you need to know about the Voice to Parliament visit here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

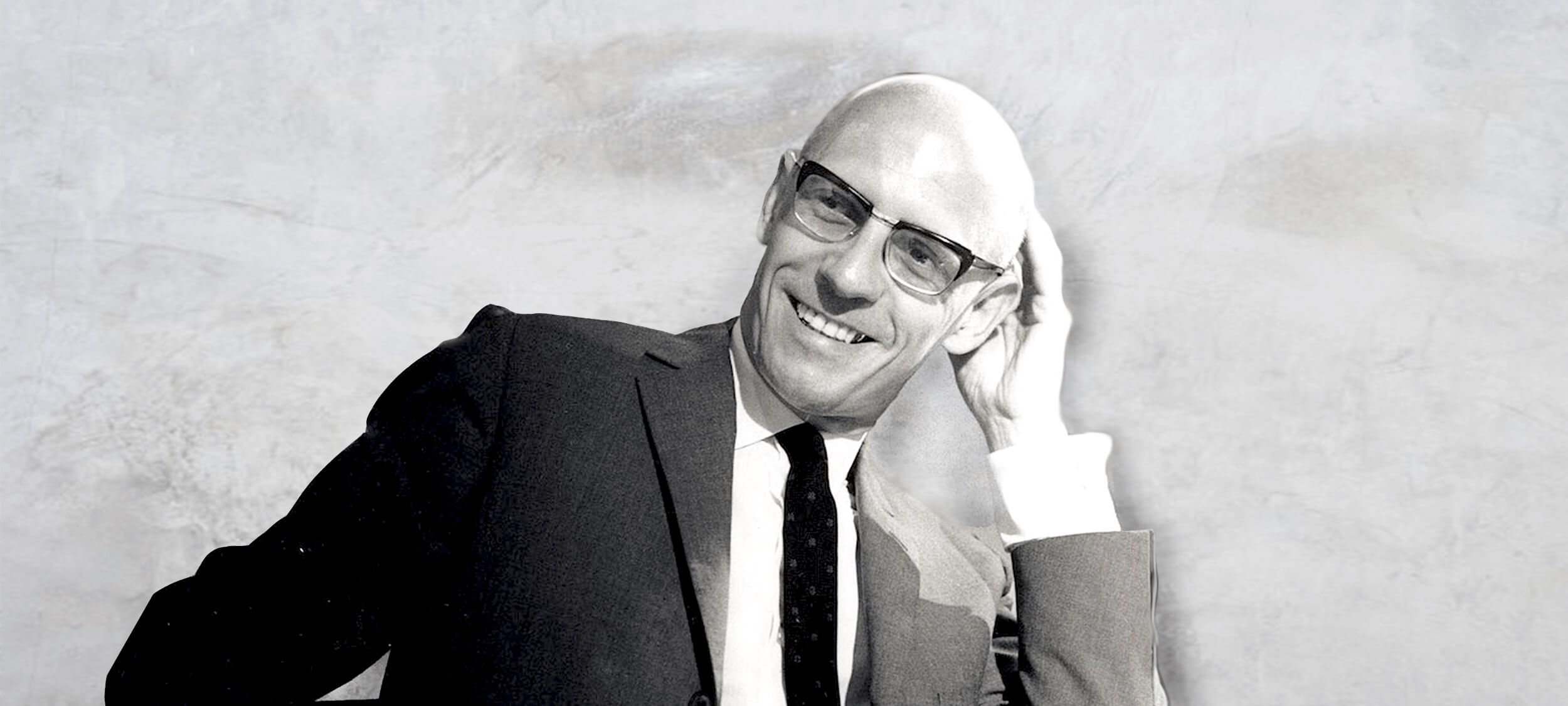

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Who’s your daddy?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Antisocial media: Should we be judging the private lives of politicians?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 9 FEB 2023

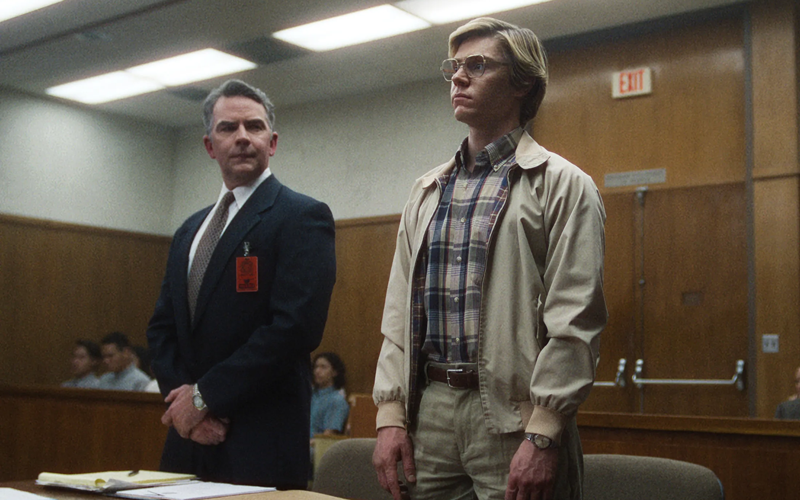

In January 2023, actor Evan Peters took to the stage to accept a Golden Globe for his performance as Jeffrey Dahmer in the surprise streaming success Monster – The Jeffrey Dahmer Story.

It was a moment of odd contrast. There was Peters, dressed in a Dior suit, surrounded by opulence of the highest order and luxuriating in the most comfort and security imaginable — rich, safe, protected — accepting an award for his portrayal of a serial killer. More than that, the families of Dahmer’s victims were nowhere to be seen. As the actor collected the gong, those whose lives had been forever shaped by the crimes of a serial killer — second-order victims, whose narratives had been used for art — were off-screen.

It was a moment that crystalised the strangeness of our modern obsession with true crime, an obsession that is taking over the entertainment industry, and swamping podcast feeds and our small screens. In swathes of the Western World, we are safer than ever before from the threat of another Dahmer — and yet, in our post-Making A Murderer world, ripped from the headlines stories of violence and immorality are everywhere, even as such experiences are becoming, for most of us, as alien as stories set on Mars.

And such stories have real-life victims who are still with us; still alive, and in many cases, still grieving. These people who deserve emotional security are being ignored and overwritten by Hollywood.

Why then can’t we get enough of Ed Gein, and Ted Bundy, and the mountain of murderers that fill up our screens? What are the ethics of engaging with these traumas casually, over dinner, or on our way to work? And what can we do to make this immensely popular sub-genre genuinely ethical?

Why Are We Getting Off On Murder?

It would be wrong to suggest that our current moment of true crime consumption is a total deviation from past trends. Stories of horror and amoral behaviour have been with us since at even earlier than the time of the Brothers Grimm — most oral storytelling revolved around bloodshed, deviants, and murder.

It would also be wrong to suggest that true crime is an empty or useless art form. Art is therapeutic because it allows us to explore and imagine heinous violence and immorality from the safety of our homes. It’s a tool for processing collective fear; collective horror. It’s a way for us to explore how we feel about our own moral systems, by examining the lives and actions of those who deviate from those systems.

However, it’s the “based on a true story” tag that makes true crime distinct. It is hard to imagine that Monster would have the same impact on the mass culture if it was a total fiction. The “true” in “true crime” is part of the sell.

Engaging in the world of true crime means engaging in a world where serial killers lurk around every corner. For those of us living in cities in the Western World, that is far from true. Serial killers were always the aberration to the rule. Now, they’re positively alien — in the U.S., serial crime makes up less than one percent of all crimes recorded. For those of us with class privilege, our deaths will come, most likely, from heart disease, not a sociopath in oversized glasses who will later mummify our heads.

Why true crime has blossomed in the context of these cultural shifts is hard to say. Could it be a result of the passivity baked into entertainment these days? So much of us binge shows to tune off, switch out, and relax on the couch. True crime is excitingly different. Podcasts like My Favourite Murder, or smash hits like Making A Murderer gives audiences an opportunity for further engagement that extends after the credits roll. You can read Wikipedia pages. You can listen to more podcasts; watch spin offs; read testimonies. And that means you can become a sort of detective of your own, sniffing out leads, becoming not just a watcher, but a researcher.

Blood On Whose Hands?

The cultural context for our obsession with true crime adds a string of ethical dilemmas to consuming it. For a start, our obsession is coming a time where we are more able than ever to educate ourselves on the crooked and fundamentally broken nature of the police force. Most true crime is ‘copaganda’, saturating the populace with the myth that most police officers are inventive, savvy artists stringing together clues, rather than overfunded, inadequate mental health professionals at best, and the violent arm of the state at worst.

True crime also plays uncomfortably into pre-existing racial divides. In most true crime shows produced in the United States, Australia and the UK, the victims come from ethnic backgrounds that are not white. The cops, by contrast, are white. The looming threat of the white savior narrative is thus unavoidable. Just as problematically, race is an unspoken presence in most true crime, rarely acknowledged, and glossed over by artists in favour of the flashier, gorier elements of these stories.

Finally, real-life crime means real-life victims. Dahmer’s victims have children; friends. These crimes leave intergenerational traces – there is a legacy of pain that drips down bloodlines after a life is cruelly and inhumanely snuffed out. Not only have these second-order victims lost a loved one, they’ve seen that loved one turned into newspaper headlines and bit players in a swathe of miniseries and podcasts.

Creators of true crime art have a responsibility to these families. The reason for this responsibility is two-fold. Firstly, these stories would, devastatingly, not have happened were it not for the victims. In the worst, most painful way, Dahmer was who he was because of the people he killed. His story is their story, and any Hollywood creative who tells that story and makes a dime is profiting off the pain of victims. Ryan Murphy, Monster’s creator, has a net worth of $150 million. Evan Peters has a net worth of $4 million. Both have enjoyed significant financial success from Monster that the second-order victims of Dahmer have not.

Creators of true crime art have a responsibility to these families… The worst moment of these people’s lives are being turned into entertainment.

The pain of those whose lives were affected by Dahmer provides the second reason for the responsibility of true crime artists — these victims and their families are just that. Victims. The worst moment of these people’s lives are being turned into entertainment. All the award shows that Peters and Murphy get to swan about at seem actively exploitative, given the human suffering that they took from real-life, and fashioned for the screen.

The way to resolve this responsibility is proper financial remuneration. These families deserve to be compensated for their stories, and for their pain. Moreover, such an obligation extends beyond just those involved with Monster, and implicate all true art creators, no matter the medium. How often have you listened to a true crime podcast, in which a grisly murder is being detailed, only to have your experience interrupted by a jocular advert for mattresses and at-home meal kits? These moments sit the grisly murder next to the adverts that make the creators of such content wealthy – throwing into focus that the true crime industry is just that — an industry.

Sure, in a capitalist system, all art has to be commercially minded to some extent – art is expensive to make, and artists deserve to be compensated. But the integration of advertising into true crime feels particularly craven. The money must be shared. Those who deserve to be paid should be paid.

None of this is an argument for shutting down true crime art, or censoring it or banning it in any way. True crime, for its flaws, serves a purpose. It can make us think about class; about context; about law. But to be truly ethical, true crime must shift its relation to the victims who are involved in these stories. Otherwise, there’s blood on the hands of more than just the murderers.

For more insights into our consumption of true crime, tune into the FODI22 discussion, The Crime Paradox

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Freedom of expression, the art of…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why we find conformity so despairing

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 8 FEB 2023

The fun of betting on uncertain outcomes is not a problem. But addiction, organised crime and ubiquity make excessive gaming a social ill that needs a policy fix.

Debate about the regulation of gambling has intensified to the point where the sound and fury from all sides risks obscuring the central issues that must be addressed. With that in mind, I would like to offer a perspective on how the issue appears when viewed through the lens of ethics – rather than commerce or politics.

The essence of gambling is to take on risk in anticipation of a hoped for (but uncertain) reward. In that sense, pedestrians “gamble” when they try to save time by dodging through traffic rather than walking to a designated crossing. The same goes for those who make an “educated guess” when investing in equities. Like the punter who puts down a “prudent bet” – based on studying the form, visiting the track and so on – an active investor who takes into account “the fundamentals” is gambling.

However, not all forms of gambling are equal. Some are built around systems of probability that are consciously tuned so as to enable “the house” to win more than their customers lose over time. So long as everyone knows this, there is nothing problematic about this form of gambling. It’s perfectly acceptable to choose to spend money on entertainment.

So, if the practice of gambling is so innocuous, why all the fuss?

The answer is to be found in three forms of harm that, although external to the practice of gambling, have become intimately connected to it: addiction, organised crime and ubiquity.

First, the most serious harms caused by gambling are to individuals who become addicted to it. However, it is essential that we note that the “evil” is addiction – not gambling as such. Addiction to work or sex or chocolate is all deeply problematic for those who are afflicted. However, that does not make work, sex or chocolate intrinsically harmful.

Unfortunately, some parts of the gambling industry seek to exploit the addictive tendencies of some people. There are wicked individuals and organisations who seek out means to “hook” people on their gaming product. They do this through conscious design of machines, experiences, incentives … almost anything. There is no “accident” in this. The trap is deliberately set and snares whoever it can catch.

At the lower level of complicity are those who do not design to capture the addict – but rather fail to take adequate steps to protect them from harm.

Let’s avoid ‘wowserism’ of a kind that presents gambling as the problem. It is not.

It is perfectly acceptable to design for fun, excitement, or enjoyment. However, people in the gambling industry have a particular obligation to use all effective means to minimise the risk of harm to those who are susceptible to addiction. Failing to do so leads to tragic outcomes – and there is no way people in the industry can wash their hands of blame for what might reasonably have been prevented, if only a sincere effort had been made to do so. Instead, some try to block reforms, simply to advance their commercial interests.

Second, as law-enforcement agencies have highlighted – again and again – organised crime has got its hooks into the gaming industry. Criminals see their “regulated losses” as an acceptable cost to bear for the convenience of being able to “launder” vast amounts of cash through gambling.

Once again, the “evil” of organised crime is not intrinsic to the practice of gambling. Crime is pernicious wherever it rears its ugly head. It is simply an unfortunate fact of history that, for selfish reasons, criminals have developed a close association with the gaming industry. However, there is nothing necessary about that connection – which can and should be severed.

Finally, there is the problem of “ubiquity”. One of my earliest published articles on this topic noted that while there is nothing intrinsically wrong with, say, church choirs, it would be unspeakably destructive of the common good to place one on every street corner. You can have too much of even the best things (not sure that church choirs count).

Gambling is everwhere! This is especially so now that the “gambling bug” lives inside our phones and other communication devices. I have seen the banking records of a person who, having been driven to an insane level of addiction, lost all the money awarded in a workers’ compensation payment by placing one bet … every six seconds.

The fact that a gaming company allowed this to happen is disgusting. It is almost as bad that we saturate our world with advertising that pretends this is never anything more than “a bit of fun with one’s friends”.

What does all of this mean for the current debate? First, let’s avoid “wowserism” of a kind that presents gambling as the problem. It is not.

However, if we wish to enjoy the fun of ethical gaming we must choose the means, as a society, to eliminate (or at least ameliorate) the evils of addiction, organised crime and ubiquity.

Despite claims to the contrary, the technology required for cashless gaming is already developed. It should be used with default daily betting limits that apply across all forms of gaming – on the track, in casinos, in clubs, online … wherever. And while we’re at it – can we regulate gambling advertising so that it does not invade every aspect of our lives … especially not those of children who are at risk of being convinced that betting on sport is better than playing it.

Some people doubt it is possible to run profitable gaming enterprises without exploiting the deadly trio of addiction, organised crime and ubiquity. I do not agree. Difficult? Yes. Impossible? No. Given that gambling can be a source of innocent joy, I think the effort is worth it.

This article was first published in The Australian Financial Review.

Disclosure: The Ethics Centre works with individuals and organisations committed to improving the ethical dimension of their business, including companies that either directly or incidentally have a connection with gambling.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Let the sunshine in: The pitfalls of radical transparency

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Blame

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

AI is not the real enemy of artists

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Dr Tim Dean 2 FEB 2023

Artificial intelligence is threatening to put countless artists out of work. But the greatest threat to artists is not AI, it’s capitalism. And AI could be the remedy.

“Socrates taking a selfie, Instagram, shot outside the Parthenon, wearing a white toga, white beard, white hair, sunlit.” That’s all the AI image generator Stable Diffusion needed to create the cover image for this article.

But instead of using artificial intelligence, I could have hired a photographer or purchased an image from a stock library to adorn this article. In doing so, I would have funnelled money to a human, who might have spent it on something else created by another human. Instead, I used AI, and no money left my pocket to flow through the economy.

And therein lies the threat posed by artificial intelligence to artists: when AI can produce nearly endless creative works at near zero marginal cost, what will this mean for people who make a living via their artistic talents?

While people have lamented the prospect of AI destroying jobs for years, the discussion has remained largely theoretical. Until now. With the advent of generative AI tools that are readily available to the public, like Stable Diffusion, DALL-E and ChatGPT, the prospect of massive job losses in creative industries is rapidly becoming a reality. Not surprisingly, many creative workers – including artists, illustrators, photographers and copywriters – are fearful for their livelihoods, and not without reason.

If we believe that creative expression is inherently meaningful, and the works it produces are intrinsically valuable, then this assault on artists’ jobs would be a net loss for humanity. It’s one thing for machines to replace labourers on farms; it’s another thing entirely for AI to empty studios of artists.

But despite all the lamentations about the impact of AI on art, when I dug deeper, I realised that it’s not really AI that poses the greatest threat to art. It’s capitalism. And instead of AI accelerating the decline of art, it could actually be the key that unshackles us from our current form of scarcity capitalism and allows art to genuinely flourish.

The alienation of art

As soon as art is brought into the market, it changes. Instead of a work’s value being defined in terms of its meaning or cultural significance, it becomes defined in terms of how much someone else is willing to pay for it. Art effectively becomes a product to be bought and sold.

Given the cost of producing art – and by “art” I mean all modes of creative expression, including music, dance, poetry, fiction, etc. – and the necessity of earning money to exchange for other goods, then art necessarily becomes professionalised.

This creates distinctions between different categories of artist. One is between those who create art for fun, so-called ‘amateurs’ (from the Latin amare, meaning “one who loves”), and those who create art for money, whom we can call ‘professionals’. The latter group, and society in general, tend to look down upon amateurs as engaging in art only frivolously or lacking the talent to make it in the competitive market.

The other distinction is among professionals, and is between those who work as commercial illustrators, designers, photographers, musicians, copywriters, etc., and the very small subset of their number, whom we might call ‘purists’, who are skilled or lucky enough to be able to produce the art they want, and can make a living out of it, either through selling to enthusiasts or collectors, or by securing grants. The purists, in turn, tend to look down on professionals as being sell-outs, or lacking the talent to make it in the rarefied art world.

The capitalist dynamic that produces these distinctions has the unfortunate consequence that many people choose not to create art at all, either because they don’t believe they are skilled enough to compete in the market, as if that were the only standard by which one might be measured, or they consider amateur art to be less than worthy. As a result of the commercialisation of art, there are likely many fewer painters, dancers, musicians and poets, than there might otherwise be.

Who’s under threat?

It’s important to recognise that when it comes to AI, it’s primarily the professionals who are at risk. These are the artists who produce the kinds of products that AI is increasingly able to create at lower cost.

AI doesn’t appear to present much of threat to purists, given that grant-givers and collectors are often spending based on the name in the corner as much as the other marks on the canvas, as it were. Purists can also do something that AI can’t: translate their personal experiences into creative expression. Amateurs are also not much at risk from AI because they don’t, for the most part, seek to derive an income from their works.

If we focus on professionals, we can see something else that the commodification and professionalisation of art have done: alienate the artist from their work.

Professionals often work to a brief defined by another person. Their art is often a means to a commercial end, such as capturing a prospective customer’s attention with a graphic or jingle, or by gussing up the interior of a restaurant. Some of this work can be deeply meaningful and rewarding, but much of it is far removed from what the artist would otherwise create were they not in dire need of money to pay the bills.

As one commenter on YouTube remarked: “As an artist I’m constantly conflicted with needing to make art that has ‘market value’ and can be sold to someone to financially support myself, and just making art for art’s sake because I want to make something that I like, and to express myself through the power of creativity.”

This alienation of the artist from the work they genuinely wish to produce has been discussed at length as far back as by Karl Marx. It’s also the reason why Pablo Picasso joined the Community Party.

It means that much of the art produced by professionals is, by its commercial nature, also helping to reinforce the very commercial system that binds it. This undermines one of the core social functions of art, which is to be a form of political expression, often employed to highlight and challenge the power structures that stifle and oppress humanity.

From this perspective, I saw that capitalism has already made the world hostile to art. AI is just worsening the situation of those have chosen to make a career out of their artistic talents.

AI acceleration

I can see two bad responses to this situation. The first is to attempt to stuff the AI genie back in the bottle. Some are attempting to do that right now, primarily through a series of court cases against some of the major generative AI companies under the pretence of copyright violation.

The outcome of these cases (assuming they are not settled or dismissed) will likely have a tremendous impact on the future of generative AI. However, it’s far from clear that US copyright law, where the cases are being held, will find that generative AI has done anything illegal. At best, the courts might require that artists are able to opt-in or opt-out of the datasets used to train AI. But even that seems unlikely.

The second bad response is to let AI run unfettered within the current economic paradigm, where it could destroy more jobs than it creates, put millions of professional artists out of work, and concentrate wealth and exacerbate inequality to an unprecedented degree. Should that happen, it’d create a genuine dystopia, and not just for artists.

The good news is that I can see at least one good solution. This is to leverage the power of AI to dramatically boost productivity and lower costs, and use that new wealth to improve everyone’s lives through a mechanism such as a universal basic income, greater subsidies or public funding, a shorter working week or a combination of them all.

I’m not alone in endorsing this idea about transforming capitalism. Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, which created ChatGPT and DALL-E, has argued something very similar in an essay called Moore’s Law for Everything. In it, he states that “we need to design a system that embraces this technological future and taxes the assets that will make up most of the value in that world – companies and land – in order to fairly distribute some of the coming wealth. Doing so can make the society of the future much less divisive and enable everyone to participate in its gains.”

This would likely be a multi-decadal project, but it would set us on a course that would decouple the work that we do from the income that we earn. This could release artists from the shackles of capitalism, as they’ll be increasingly able to produce the art that is meaningful for them without requiring that it be saleable in a competitive market.

It’d also free up more time for amateurs to explore their creative potential, possibly resulting in an explosion of art. Imagine how many people would pick up a paintbrush, pen or piano if they had the time and financial security to do so.

Much of that creative output will be low quality, but that’s not the point. If we believe that the creative act is inherently valuable, then it’s worth it. Plus, there are likely many people of startling artistic talent who are currently otherwise occupied earning a living to be able to explore and develop their abilities.

The decoupling of art from the market could also help liberate its political power, enabling more artists to question, challenge and offer solutions to society’s many problems without having their livelihood threatened.

The big question is how do we get from a world where AI is stripping people of their livelihoods to one where AI is freeing them from toil? There are no easy answers to that question. But it’s crucial to focus our attention on the root cause of the problem that artists face today, and that’s not AI, it’s capitalism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

But how do you know? Hijack and the ethics of risk

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Volt Bank: Creating a lasting cultural impact

Volt Bank: Creating a lasting cultural impact

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker 1 FEB 2023

Looking back, Steve Weston says, that Volt Bank, an innovative new player that intended to crack open the Australian banking oligopoly, was well positioned to show that banking could be done in a better and more ethical way. Unfortunately, it wasn’t to be.

“There was no one else in Australian banking that was doing what we were doing. We built something that didn’t exist elsewhere,” Steve says.

“I’m proud of so much, but I’ll take to the grave that feeling of disappointment of having to close the doors. We were so close to a full launch and being able to show everyone what we had built.”

It’s this kind of benevolent aspiration that characterises Steve, Volt’s founder and chief executive. The very same thing that prompted former customers to write to him, not in anger but in sympathy, following the collapse of the neobank in June last year.

Volt Bank returned $100 million in deposits to all customers and handed back its banking licence after it couldn’t raise enough capital to scale up its operations, leaving 140 staff and a despondent Weston in the aftermath. Everyone was disappointed.

“I got a lovely note from a guy… his dad is 96 years old and had put $240,000 into a Volt Bank account a couple of years ago as an inheritance for his grandkids. He opened his account using his phone without any help.”

“And his father told him how disappointed he was that Volt was so great and that they were closing down, and he’d had to take his money back.”

Rewind three years to January 2019 and North Sydney-based Volt Bank had become the first Australian startup to get a banking licence, following a rethink of the rules under the Morrison government prior to the damning findings of the 2018 Hayne Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry.

Steve and his team were determined not to squander an opportunity to offer Australians a better and fairer banking experience, building what the AFR described as “arguably the best mortgage lending platform in the industry”. Remarkably, Volt Bank’s innovative technology could issue mortgages in just 15 minutes as opposed to several days with most lenders.

Organisationally, Volt remained in the pilot phase and never opened its deposit book to the public, but the neobank did forge tough-to-secure industry partnerships with big names like PayPal, Cotton On and AFG.

There was a lot at stake, Steve remembers, in building something that could compete against established lenders like the powerful big four, but with prior positions at NAB, St George and more recently Barclays on his resume, Weston felt ready to give it a go.

Since arriving back in Australia in 2016, Steve had been vocal about the negative behaviours and systems he witnessed in the UK being repeated here in Australia. In 2017 at a Banking and Finance Oath conference, he implored the audience to consider necessary changes to ward off mistakes that were being made here that he had seen in the UK including lack of transparency, fairness and poor customer practice.

Not only did Steve seek to rethink banking, but he also sought to provide staff with an innovative and embracing environment where they could live and work within the values that Volt was offering to new customers.

“We made it fun like many fintechs, we did yoga and meditation, we had beers and the like,” he recalls.

“But more importantly, we were also about changing the world and doing things in a different and better way … there were great people on the team – not just technically smart, but good people who would walk over broken glass to make a real difference to society.”

“Our ambition and values were genuine, they weren’t just words on the wall. Our customers, business partners, shareholders, staff and even regulators could see and feel the different approach we were taking.”

Whilst Volt Bank had raised over $200m, to scale up it needed to raise significantly larger sums.

Turbulent market conditions – including the post pandemic economic downturn, Ukraine invasion and climbing interest rates the world over – and the 20% cap on single shareholders in Australian banks saw scores of large potential investors steer clear of investing in the Aussie neobank. Steve says they looked everywhere for capital, leaving “no stone unturned”.

Unable to raise the capital it needed, and the board voted to fold the bank on June 29th.

Steve says a fold is about so much more than a shortfall of capital, in banking or beyond – it’s about making the tough decision after weighing up ethical considerations. He hopes that other challenger banks will get an opportunity to bring the sort of change to the Australian banking market that the public is so keen to see. He says that is not just about offering fairer pricing and better service levels, it’s about bringing improved ethics to banking.

“When we talk about ethics, it’s not just about the issues highlighted in the Royal Commission like breaching regulations and charging dead people,” Steve says.

“It’s about not telling customers that you are going to put their interests at the heart of everything you do and then pricing products that only favour new customers. Banks can price products as they see fit but they should be far more transparent when the interest rates are not as good for loyal customers; the same ones that are supposedly being put at the centre of banks post-Royal Commission more ethical approach.”

Steve says he was comforted by the fact that almost all 140 staff at Volt went on to be snapped up by finance and tech titans ANZ, Commonwealth Bank, Xero, and Atlassian, and often with higher salaries too, he adds.

“We had more than 100 companies approach us, saying ‘we’re happy to take your staff’, including big banks, small banks, tech companies, retailers – many did pitches to the staff,” he remembers.

“And as it turned out, we didn’t only help our staff polish up their CVs and fine tune their interview skills, we also helped staff articulate the value they would offer to new employers.”

It’s this empathetic duty of care from Volt’s management that set the neobank apart – and Steve hopes that despite Volt not being able to continue under its own steam, that its impact will bring a positive impact to society.

“We spoke with our staff about taking their learnings from Volt about doing the right thing, to their new employers. It means Volt will have a positive rippling influence on a variety of industries, about how you should work – the culture, the ethics, and the integrity.”

The pain and shame of failure is often sought out by venture capitalists and business leaders in the US. It is viewed positively and seen as an opportunity for learning. Steve himself remains as determined as ever in the wake of Volt Bank’s collapse to shake up an industry mired by a reputation of misconduct and this time; he comes armed with the potent learnings of a failure done ethically. Whether that is embraced in Australia is yet to be seen.

“We were, in some ways, a poster child in terms of ethics, governance, compliance, openness … And like I said, the feedback from people was overwhelmingly positive, but we just couldn’t raise the capital we needed,” he says.

“I still have a fire in my belly to do right by society and it’s now burning more than ever because I’ve got to redeem myself and I’ve learned so much.”

And what of Volt’s industry-first 15-minute mortgage technology? Steve says, a sales process is underway. He’s hoping the technology can find a home and deliver improved outcomes for customers, something he admits will be an “interesting feeling” after the rise and fall of Volt Bank.

“On the one hand, that would be a kind of validation of what Volt’s tech was going to deliver, and on the other hand, it’ll be: ‘Why the hell couldn’t we raise the capital and have done it ourselves?’”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Big tech knows too much about us. Here’s why Australia is in the perfect position to change that

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Do organisations and employees have to value the same things?