Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Cris Parker The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

Emerging from the turbulence of COVID-19, we have the opportunity to escape the hold of our past and use moral imagination to explore a better future.

After months of living through disruption, old work habits and perceptions may no longer fit the ‘new normal’, says Michael Baur, Associate Professor in the Philosophy Department at Fordham University and an Adjunct Professor at Fordham Law School.

“There’s a very positive side to this, because it makes us realise that the seemingly obvious, natural way of operating is not so obvious anymore.” says Baur.

“It does afford us the ability to think a little bit more carefully about what we’re doing.”

A simple example may be that, after mastering virtual meetings, we realise that the regular face-to-face interstate meetings we thought to be essential are not, in fact, a necessary part of doing business. Instead of asking ‘can we do this online?’ we might now ask, ‘should we do this online, is there a good reason to do it in person?’

“It’s liberating, potentially, to be able to be thrown back and see that the seemingly natural is really not so natural and obvious after all,” says Baur.

Aspects of life previously unquestioned, such as our choices of where to live, send our kids to school or even the jobs we do, may be cast in a different light.

Speaking with Bob McCarthy, an Irish colleague, he spoke of the experience of the ‘Celtic Tigers’ during ten-year-plus period of economic growth prior to 2008. “Ireland had never experienced anything like it and our economy became the envy of the world. Of course, we lived in accordance with our new wealth and fame – two houses each, BMWs, ski holidays and buying chalets in Morzine”, says McCarthy.

Many rationalised their good fortune – ‘we’ve had it tough for so long we deserve a little luxury.’ So, when the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) crash came, it came hard. There was a 60% average fall in property prices, high unemployment, many family tragedies, house repossessions and years of debt to repay.

Bob said that the experience of crisis changed attitudes and behaviours, “Now, those of us who have been through this look at life, business, money, relationships, values, ethics through a different filter than before”.

He describes the experience of having benefitted from the pain. What had once seemed important during the times of excess are no longer important. What didn’t matter then, matters to him now. “Don’t get me wrong – not everything has changed. But for most the filter we use has changed”.

Baur says that, with the experience of COVID-19, we now have a similar opportunity to reset our aspirations, “When we were riding easy, just several weeks ago, we were in a state of deception.” He recognises that the pandemic has caused major economic shocks – perhaps even more severe than those caused by the GFC, “And now we can regroup. That seems to me a more positive, healthy way of thinking of it – that all of this wealth and expectation was not really ours to have to begin with.”

Bigger is not always better

The aftermath of the pandemic presents a good time to reassess our attitude to growth. The fact that almost all sectors of business have suffered means that there is a collective opportunity to slow down and reassess whether the purpose of business is to make more money for money’s sake, or to provide for human need.

Business is now attending to issues that were always there to be addressed – but remained largely ‘unseen’. By presenting itself as a ‘common enemy’, COVID-19 has caused us all to look up at the same time and respond to a suite of collective problems.

In many cases, our response has been an expression of human goodness, compassion and altruism. ‘Them’ has become ‘us’.

For example, Accor hotels, is opening up unused accommodation to support vulnerable people. Simon McGrath, Accor’s CEO, says, “Our doors are open,” said Accor’s McGrath “We have accommodation assets that can help people in times of need, and while the industry’s been devastated commercially, it doesn’t mean we can’t help.”

In a similar vein, UBER has partnered with the Women’s Services Network to provide 3,000 free rides to support those needing safe travel to or from shelters and domestic violence support services.

Australia was relatively unscathed by the GFC of 2008 and did not experience the large economic downturn felt elsewhere on the globe. Australia has also managed to flatten the curve and “none have been more successful than Australia and New Zealand at containing the coronavirus,” said Jonathan Rothwell, Gallup’s principal economist.

This is thanks to our strong public health system and our comprehensive testing regime, to the tracing of carriers and our strict self-isolation and physical distancing laws. We were also lucky that our geographic isolation bought us an extra 10 precious days to prepare.

However, Australia has not and will not escape the economic consequences of the pandemic – and our response to the threat it poses. So, how will we shape up when the challenge is an economic recession as opposed to a medical emergency? Will the good will and sense of common endeavour persist during the next phase of struggle? More interestingly still, will the sense of mutual obligation survive a return to posterity? Or will we resume our ‘old ways’?

Baur says an argument could be made that business and society in general did not make the most of the lessons to be learned from the GFC, more than a decade ago. Ireland’s Bob McCarthy, is of the same opinion, “We may be having an opportunity that would have been a lost opportunity from that time,” he says.

“What might be seen as a loss of opportunity, a loss of growth, in one limited respect, is really a darn good thing for everybody,” Baur says.

Echoing the same sentiment, Mike Bennetts CEO of Z Energy in New Zealand told audiences at the Trans – Tasman Business Circle that this virus has accelerated us into the future by 5 years, so “let’s make the most of it”. Our instinct is to seek comfort and confidence in the known which will mean going back to the way it was.

The challenge, now, is not only to create a new future but a better future. For that to happen we need to unleash a better version of ourselves.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why you should care about where you keep your money

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The role of ethics in commercial and professional relationships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

The business who cried ‘woke’: The ethics of corporate moral grandstanding

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Leading ethically in a crisis

Leading ethically in a crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

It is difficult to excel in the art of leadership at any time – let alone in the midst of a crisis. Yet, this is precisely when good leadership is at a premium.

Right now, we must ask: what is ‘good’ leadership and how should leaders respond to the demands placed upon them during periods of extraordinary ethical complexity?

In attempting to answer these questions, I am thrown back on my own experience of leadership – including at present. In that sense, this not a detached, objective account. Rather, it is a reflection on (and of) lived experience.

The first obligation of a leader is to see, and sense, the whole picture. This means being alive to the undercurrents of feeling and emotion flowing through the organisation, while simultaneously keeping a clear view of the evolving strategic landscape and being ‘present’ in the moment.

The good leader needs to ensure that no one affected by the crisis is either overlooked or marginalised. This is harder than it seems. When driven by the ‘lash of necessity’, it’s all too easy to favour some people because of their utility, while dismissing others as ‘dead weight’.

I have been struck by the number of times that people have said the current emergency requires them, albeit reluctantly, to be cold-hearted, brutal or even cruel. I realise that such comments do not reflect their personal inclination – but instead reflect their response to evident necessity. However, I think that ethical leaders have an obligation to challenge that tendency – not least by naming it for what it is.

This is not to say that issues of relative utility are unimportant. Nor is it the case that one should avoid difficult decisions – such as those that might lead to job losses. Rather, the leader’s job is to ensure that such decisions are not made on the basis of cold, dispassionate calculation. Instead, the leader has an obligation to ensure that the ethical weight of each decision is felt and the heft of the burden that falls from each decision is known.

The second requirement of ethical leaders is that they resist demands for a certainty they cannot or should not provide. This is easier said than done. There are some contexts in which the suspense of ‘not knowing’ can be thrilling; however, for most people operating under stress, confronting ‘the unknown’ reinforces a sense of powerlessness and is deeply unsettling.

Even so, ethical leaders should resist the temptation to offer people false certainty, no matter how much that might be desired. Instead, a good leader should be resolutely trustworthy by only claiming as ‘certain knowledge’ what is genuinely known. Otherwise, a leader’s integrity can be undermined by something as simple as a gap between what was asserted as fact and what is subsequently revealed to be true.

None of this is to suggest that people be denied glimmers of hope based on one’s best estimate. It is merely to counsel caution – especially when a delay can open up new possibilities. The recent and unexpected emergence of the Federal Government’s JobKeeper scheme is a good example.

Leading during a crisis requires an ability to foresee a future, preferred state and then ‘backcast’ to the present when making decisions. As noted above, in the course of a crisis, many decisions will be made under the ‘lash of necessity’.

In these circumstances, people will be driven to accept the harshest treatment as a ‘necessary evil’. However, a time will come when the crisis is relegated to the past and those who remain in an organisation will want to know what justified the sacrifice – especially that made by those who fell along the way.

Telling people that it was ‘necessary’ will not be enough. Instead, those who remain will require a positive justification that goes beyond ‘mere survival’. It is in the light of that positive justification that all of the preceding decisions need to be evaluated. So, leaders need to ask themselves, ‘is today’s decision going to foreclose on the future we hope to create’. In particular, will my present choice make my preferred future impossible? Will it delegitimise my future leadership?

Finally, leaders need to release themselves from the unrealistic expectation of ‘ethical perfection’. This is not to say that one should be careless in decision making. Rather, it is to recognise a fundamental truth of philosophy: that some ethical dilemmas are so perfectly balanced as to be, in principle, undecidable.

Yet, we must decide. The only reasonable standard to apply in such cases is that we are sincere in our judgement and competent in our capacity to make ethical decisions – a skill that can be learned and supported.

There are particular ethical challenges to be faced by leaders during times such as these. Critical decisions may have to be made alone. Not everything that could be said should be said. There are some options that need to be considered but not voiced – as they would cause unnecessary worry – only to remain dormant.

There are ‘gordian knots’ that may need to be cut rather than carefully unravelled over a period of time that is simply not available. There is the fact that the weaknesses in oneself (and others) will be revealed under pressure – and that unpleasant truths will need to be acknowledged and endured.

At times such as these, the things that sustain good leaders are an unshakeable sense of purpose and a solid core of personal integrity. One might protect others from the harshest of possibilities for as long as possible – but never oneself.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Between frenzy and despair: navigating our new political era

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Beyond the shadows: ethics and resilience in the post-pandemic environment

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethics of workplace drinks, when we’re collectively drinking less

WATCH

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

How to build good technology

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

In recent weeks, there has been a particularly intense debate about whether or not students should return to the classroom.

This article was first published by Crikey, in their weekly Ask the Ethicist column featuring Dr Simon Longstaff.

Much of that debate has focused on the interests of the children and their families. However, there is a third stakeholder group – the nation’s teachers – who need to be considered. Part ‘essential worker’, part ‘political football’, they have been celebrated on one hand and condemned on the other. So, what are the ethical obligations of those who teach our children during COVID-19.

As a starting point, let’s agree that education is a significant ‘good’ and that children should not be deprived of its benefits unless there are compelling reasons for doing so. Compelling reasons would include the potential risk of infection due to school attendance.

At present, the balance of evidence is that the risk of children becoming infected is low and that they are unlikely to be transmitters of the disease to adults – especially in well-controlled environments. However, why take any risk – if viable alternatives are available?

Here, we should note that the education of children has not been suspended during the crisis. Instead, it has continued by other – ‘online’ – means. This has required a massive effort by the teaching profession to ‘recalibrate’ the learning environment to support distance learning.

We should also note that the ability to provide distance education distinguishes teachers from other essential workers who, of necessity, must provide a face-to-face service. For example, while some doctors can consult with patients using ‘telemedicine’, most health care workers need to be physically present (e.g. when administering a flu injection, or caring for a bed-ridden patient, etc.).

So, if distance learning achieves the same educational outcomes as classroom teaching, teachers would not seem to be under any moral obligation to return to the classroom. However, the Federal Government has recently cited reports suggesting that online learning produces ‘sub-optimal’ outcomes for students (unwelcome news for children living in remote communities and educated by the ‘school of the air’).

If this is true, then it would suggest two things. First that the government should be massively increasing its investment in education for children who have no option but to engage in distance education. Second, that teachers should be heading back into the classroom.

However, what of the teacher who lives with people for whom COVID-19 is a particular threat … the aged and infirm? In those cases, the choice is not just a matter of balancing a public duty as an educator against a preference for personal safety. Rather, the teacher is caught in an ethical dilemma of competing duties.

In such a case, I think it would be reasonable for a teacher to claim they have a conscientious objection to returning to the classroom – grounded in a refusal to be the potential cause of harm to a loved one – especially when the only certain protection for the loved one is that the teacher remain isolated.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Joanna Bourke

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Moving work online

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to put a price on a life - explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 1 MAY 2020

In all the time I’ve spent teaching ethics – from trolley problems to discussions of civilian casualties at war to the ethics of firefighting – there have been a few consistent trends in what matters to people.

One of the most common is that in life-and-death situations, details matter. People want to know exactly who might die or be rescued: how old are they? Are they healthy? Do they have children? What have they done with their life?

What they’re doing, whether they know it or not, is exploring what factors could help decide which life it would be most reasonable, or most ethical to save, relative to the other lives on the table.

Moreover, it’s not only in times of war or random thought experiments that these questions arise. Every decision about where to allocate health resources is likely to have life-or-death consequences. Allocate more funding to women’s shelters to address domestic violence and you’ll save lives. However, how many lives would you save if that same money were used to fund more hospital beds, or was invested into mental health support in rural communities?

One widely-used method for ensuring health resources are allocated as efficiently as possible is to use QALY’s – quality-adjusted life years. QALY is an approach that was developed in the 1970’s to more precisely, consistently and objectively determine the effectiveness and efficiency of different health measures.

Here’s how it works: imagine a year of life enjoyed at full health. It gets assigned a score of 1. Every year of life lived at less than full health gets assigned a lower score. The worse off the person’s health, the lower the score.

For example, take someone who has to undergo chemotherapy for five years. They have full mobility, but have some difficulty with usual activities, severe pain and mild mental health challenges. They might be given a QALY score of 0.55.

Once we’ve gotten a QALY score, we then need to work out how much the healthcare costs. Then, it’s simple maths: multiply the cost by the QALY score and you get an idea of how much each QALY is costing you. Then you can compare the cost effectiveness of different health programs.

QALY’s are usually seen as a utilitarian method of allocating health resources – it’s about maximising the utility of the healthcare system as a whole. However, like most utilitarian approaches, what works best overall doesn’t work best in individual cases. And that’s where criticisms of QALY arise.

Let’s say two patients come in with the same condition – COVID-19. One of them is young, non-disabled and has no other health conditions affecting their quality of life. The other person is elderly, has a range of other health conditions and is in the early stages of dementia. Both patients have the same condition. However, according to the QALY approach, they are not necessarily entitled to the same level of care – for example, a ventilator if resources are scarce. The cost per QALY for the younger patient is far lower than for the elderly patient.

For this reason, QALY’s are sometimes seen as inherently unjust. They fail to provide all people with equal access to healthcare treatment. Moreover, as philosopher and medical doctor Bryan Mukandi argues, if two patients with the same condition are expected to have different health outcomes, there’s a chance that’s the result of historical injustices. Say, a person with type-2 diabetes receives a lower QALY score as a result, but type-2 diabetes is correlated with lower income, the scoring system might serve to entrench existing advantage and disadvantage.

Like any algorithmic approach to decision-making, QALYs present as neutral, mathematic and scientific. That’s why it’s important to remember, as Cathy O’Neil says in Weapons of Math Destruction, that algorithms are “opinions written in code.”

Embedded within QALY’s method are a range of assumption about what ‘full health’ is and what it is not. For instance, a variation on the QALY methodology call DALY – disability-adjusted life years – “explicitly presupposes that the lives of disabled people have less value than those of people without disabilities.”

An alternative to the QALY approach is to adopt what is known simply as a ‘needs-based’ approach. It’s sometimes described as a ‘first come, first served’ approach. It prioritises the ideal of healthcare justice above health efficiency – everyone deserves equal access to healthcare, so if you need treatment, you get treatment.

This means, to go back to our elderly and young patients with COVID-19, that whoever arrives at the hospital first and has a clinical need of a ventilator will get one. QALY advocates will argue that in times of scarcity, this is an inefficient approach that may border on immoral. After all, shouldn’t the younger person be given the same chance at life as the elderly person?

However, there is something radical underneath the needs-based approach. QALY’s starting point is that there are limited health resources, and therefore some people will have to miss out. A needs-based approach allows us to do something more radical: to demand that our healthcare is equipped, as much as possible, to respond to the demand. Rather than doing the best with what we have, we make sure we have what is necessary to do the best job.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The value of a human life

The value of a human life

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 1 MAY 2020

One of the most enduring points of tension during the COVID-19 pandemic has concerned whether the national ‘lockdown’ has done more harm than good.

This issue was squarely on the agenda during a recent edition of ABC TV’s Q+A. The most significant point of contention arose out of comments made by UNSW economist, Associate Professor Gigi Foster. Much of the public response was critical of Dr. Foster’s position – in part because people mistakenly concluded she was arguing that ‘economics’ should trump ‘compassion’.

That is not what Gigi Foster was arguing. Instead, she was trying to draw attention to the fact that the ‘lockdown’ was at risk of causing as much harm to people (including being a threat to their lives) as was the disease, COVID-19, itself.

In making her case, Dr. Foster invoked the idea of Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). As she pointed out, this concept has been employed by health economists for many decades – most often in trying to decide what is the most efficient and effective allocation of limited funds for healthcare. In essence, the perceived benefit of a QALY is that it allows options to be assessed on a comparable basis – as all human life is made measurable against a common scale.

In essence, the perceived benefit of a QALY is that it allows options to be assessed on a comparable basis – as all human life is made measurable against a common scale.

So, Gigi Foster was not lacking in compassion. Rather, I think she wanted to promote a debate based on the rational assessment of options based on calculation, rather than evaluation. In doing so, she drew attention to the costs (including significant mental health burdens) being borne by sections of the community who are less visible than the aged or infirm (those at highest risk of dying if infected by this coronavirus).

I would argue that there are two major problems with Gigi Foster’s argument. First, I think it is based on an understandable – but questionable – assumption that her way of thinking about such problems is either the only or the best approach. Second, I think that she has failed to spot a basic asymmetry in the two options she was wanting to weigh in the balance. I will outline both objections below.

In invoking the idea of QALYs, Foster’s argument begins with the proposition that, for the purpose of making policy decisions, human lives can be stripped of their individuality and instead, be defined in terms of standard units. In turn, this allows those units to be the objects of calculation. Although Gigi Foster did not explicitly say so, I am fairly certain that she starts from a position that ethical questions should be decided according to outcomes and that the best (most ethical) outcome is that which produces the greatest good (QALYs) for the greatest number.

Many people will agree with this approach – which is a limited example of the kind of Utilitarianism promoted by Bentham, the Mills, Peter Singer, etc. However, there will have been large sections of the Q+A audience who think this approach to be deeply unethical – on a number of levels. First, they would reject the idea that their aged or frail mother, father, etc. be treated as an expression of an undifferentiated unit of life. Second, they would have been unnerved by the idea that any human being should be reduced to a unit of calculation.

…they would have been unnerved by the idea that any human being should be reduced to a unit of calculation.

To do so, they might think, is to violate the ethical precept that every human being possesses an intrinsic dignity. Gigi Foster’s argument sits squarely in a tradition of thinking (calculative rationality) that stems from developments in philosophy in the late 16th and 17th Centuries. It is a form of thinking that is firmly attached to Enlightenment attempts to make sense of existence through the lens of reason – and which sought to end uncertainty through the understanding and control of all variables. It is this tendency that can be found echoing in terms like ‘human resources’.

Although few might express a concern about this in explicit terms, there is a growing rejection of the core idea – especially as its underlying logic is so closely linked to the development of machines (and other systems) that people fear will subordinate rather than serve humanity. This is an issue that Dr Matthew Beard and I have addressed in the broader arena of technological design in our publication, Ethical By Design: Principles for Good Technology.

The second problem with Dr. Foster’s position is that it failed to recognise a fundamental asymmetry between the risks, to life, posed by COVID-19 and the risks posed by the ‘lockdown’. In the case of the former: there is no cure, there is no vaccine, we do not even know if there is lasting immunity for those who survive infection.

We do not yet know why the disease kills more men than women, we do not know its rate of mutation – or its capacity to jump species, etc. In other words, there is only one way to preserve life and to prevent the health system from being overwhelmed by cases of infection leading to otherwise avoidable deaths – and that is to ‘lockdown’.

…there is only one way to preserve life and to prevent the health system from being overwhelmed by cases of infection leading to otherwise avoidable deaths – and that is to ‘lockdown’.

On the other hand, we have available to us a significant number of options for preventing or minimising the harms caused by the lockdown. For example, in advance of implementing the ‘lockdown’, governments could have anticipated the increased risks to mental health leading to a massive investment in its prevention and treatment.

Governments have the policy tools to ensure that there is intergenerational equity and that the burdens of the ‘lockdown’ do not fall disproportionately on the young while the benefits were enjoyed disproportionately by the elderly.

Governments could have ensured that every person in Australia received basic income support – if only in recognition of the fact that every person in Australia has had to play a role in bringing the disease under control. Is it just that all should bear the burden and only some receive relief – even when their needs are as great as others?

Whether or not governments will take up the options that address these issues is, of course, a different question. The point here is that the options are available – in a way that other options for controlling COVID-19 are not. That is the fundamental asymmetry mentioned above.

I think that Gigi Foster was correct to draw attention to the potential harm to life, etc. caused by the ‘lockdown’. However, she was mistaken not to explore the many options that could be taken up to prevent the harm she and many others foresee. Instead, she went straight to her argument about QALYs and allowed the impression to form that the old and the frail might be ‘sacrificed’ for the greater good.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

FODI launches free interactive digital series

FODI launches free interactive digital series

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 1 MAY 2020

FODI Digital, announced today, is an exciting series of free, online conversations to be live-streamed on May 9 and 10.

The line-up will feature a selection of the international and Australian speakers originally slated for the live festival that was cancelled, by government order, as the COVID-19 lockdown came into effect last month.

“The theme for 2020’s live festival was Dangerous Realities and we seem to well and truly have encountered one. Critical thinking is essential, especially as we isolate further from our communities, families and global neighbours.” said Festival Director, Danielle Harvey.

Executive Director of The Ethics Centre and Co-Founder of FODI Simon Longstaff says FODI digital is a timely invitation to think critically.

“We may submit to a lockdown of our bodies, but never our minds. If ever there was a time to test the boundaries of our thinking … it is today!”

The series of online conversations takes inspiration from the original FODI 2020 theme of ‘Dangerous Realities’, with online sessions being streamed via the festival website. The series will interrogate the reality of the current pandemic and its wider implications for our world and society.

Audiences can contribute questions live while the discussions take place.

For Festival Director Danielle Harvey, there’s never been a more important time for these critical conversations. “Decisions are being made at every level that will shape how we live our lives both now and in the future.

“While we can’t present the program in the way originally planned, these digital conversations will address topics that really need to be put under the microscope. COVID-19 will hopefully end at some point, and understanding what kind of world we will then be entering is essential.”

Sessions include:

- The Truth About China – Former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd is joined by journalists Peter Hartcher and Vicky Xiuzhong Xu, with Human Rights Watch researcher Yaqiu Wang, and strategist Jason Yat-Sen Li, in a wide-ranging discussion about China;

- The Future Is History – Russian-American journalist, high-profile LGBTQI activist and outspoken critic of Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, Masha Gessen, shares her thoughts on Russia and the coming US elections;

- Snap Back To Reality – Philosopher Simon Longstaff leads a discussion with social researcher Rebecca Huntley, political journalist Stan Grant, and fellow philosopher Tim Soutphommasane, on the social shifts, policy and economic consequences that await us in a post-COVID-19 world;

- States of Surveillance – Futurist Mark Pesce, 3A Institute data expert Ellen Broad, and founder of Old Ways, New Angie Abdilla discuss the issue of digital surveillance for virus tracking and the potential threat posed by the ‘normalisation’ of government surveillance;

- Misinformation Is Infectious – First Draft’s Claire Wardle, tech journalist Ariel Bogle discuss COVID-19-related conspiracy theories and what they tell us about technology’s role in the spread of damaging misinformation;

- Stolen Inheritance – Australian youth leaders, Daisy Jeffrey, Audrey Mason-Hyde and Dylan Storer discuss their concerns for the world they will inherit: a world of debt, educational disadvantage, diminished job opportunities, climate catastrophe and … future pandemics;

- The Ethics of the Pandemic – Philosophers Matt Beard, Eleanor Gordon-Smith and Bryan Mukandi take a step back from the day-to-day dilemmas of the pandemic to try to understand what’s really going on, the lessons we learn and the hidden costs of the choices we make;

- Political Correct-Mess – Conservative Australian commentator Kevin Donnelly, journalist Chris Kenny, and journalist Osman Faruqi join journalist Sarah Dingle to dissect political correctness and ask, “Has it gone too far?”;

- Ageing is a Disease – Biologist David Sinclair talks about cracking and reversing the ageing process, which may help the elderly in their fight against a range of diseases and viruses.

The event will live stream straight from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas website across May 9-10. Visit www.festivalofdangerousideas.com to view the program.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

David and Margaret spent their careers showing us exactly how to disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Cris Parker The Ethics Centre 24 APR 2020

A senior executive starts making out-of-character decisions that reflect his personal fears. Teams are frozen in indecision as the ground continually shifts beneath them. Days become punctuated with emotional meltdowns from people you have always relied upon in a crisis.

At home, you might be disagreeing with loved ones about the right response to COVID -19. Is the situation as serious as officials claim? Or are people exaggerating the risks? What is the right amount of physical distancing? Why should the whole of a society bear the costs for the sake of the few? Is this even a fair way to frame the questions?

These are some of the signs that the prolonged impact of COVID-19 is causing moral fatigue in the people around you.

Moral fatigue can occur when the “right thing to do” is unclear. Who should bear the cost of protecting a business? What if personally caring for elderly parents risks exposing them to deadly infection? It can be exhausting to make decisions in this kind of ambiguity, day after day.

Michael Baur, Associate Professor in the Philosophy Department at Fordham University and an Adjunct Professor at Fordham Law School, says moral fatigue comes from situations where attempts to do good also result in “destroying a good”.

“People have often referred to the idea of moral fatigue as compassion fatigue or moral distress,” he told me on a zoom call from the US. “What we have in the current context is a situation that makes it increasingly difficult to understand if I’m doing the right thing. It’s no longer possible to assume that the good that I’m doing is unambiguously good,” he says.

It could be dangerous to keep running a business, for instance, if it means employees are in danger. “There’s a real conflict there. And there are no rules.”

Why people panic

Usually, as people go about their normal lives many actions are performed on “autopilot”. Typing on a keyboard, for instance, is done out of habit; the decision of which keys to hit doesn’t exercise mental exertion; one’s finger ‘do the work’. Baur says a crisis such as COVID-19 “jumbles” the keys on the keyboard. It changes the rules and worse still, you don’t know what those new rules are as they can change, minute-by-minute.

“It’s really disorienting,” says Baur. “People go back to what they know is safe, and they become more infantile, more self-protective and defensive.”

This is the kind of response that decreases our capacity to make good decisions. It leads to the hoarding behaviours we have seen in supermarkets, anxiety about money and a focus on individual survival.

Slow down and be more forgiving

Thinking about ‘just getting beyond this’ assumes a future state where the problem no longer exists and everything is the same as before. It’s too simplistic to suggest we will all be ok – many of us won’t be, unless we adapt.

A common result of moral fatigue can be impatience. When we try to think through frameworks that no longer serve us well we can become increasingly impatient, the more we do so, the more mistakes we make – leading to even more frustration.

Baur likens our situation to building the raft at the same time that you are using it to survive. He says, it’s okay to make mistakes because we’re all trying to refashion this raft, even as we’re stepping on top of each other trying to stay afloat. Mistakes will be made.

“You’re not alone. Everybody feels the same way. We have to be more forgiving of others and I think individuals have to be more forgiving of themselves in the sense that it’s okay to be freaked out. Everybody is.”

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Karina Morgan 16 APR 2020

The coronavirus pandemic has affected nearly everything we do in our everyday lives. The things that give us joy and meaning – going to the gym, the beach, meeting friends for coffee – are no longer possible.

This is having a real impact on our mental health and capacity for good decision making. Beyond Blue have reported a four-fold increase in the number of calls and enquiries related to COVID-19 since March, a level far exceeding the period during the summer fires.

Our brains are wired to seek certainty and our neural circuits register unexpected events as threats. This triggers a fear response, known commonly as ‘fight or flight’, which causes a cascading chemical reaction in our bodies. That response prevents or impairs access to the higher levels of the brain where we deal with complex decisions.

So, it’s fair to say that uncertainty and fear reduce our capacity for quality decision making. This is, in part, because the area of impeded access involves the pre-frontal cortex, the part of our brain that actively processes information, accesses creative thinking and enables good decision making.

At its very core, ethics is about making good decisions. It asks us to consider all the ways we might act and to choose for the best. To take responsibility for our beliefs and our actions, and live a life that is entirely our own.

We know that many of you are facing challenging choices in circumstances that involve an unprecedented level of change and uncertainty in our individual and collective lives.

People are moving to work from home with kids in the house, facing job losses, closing businesses and deciding how to care for vulnerable loved ones. Many people are also experiencing the impacts of hyper-connection and feeling overwhelmed by the constant stream of new information.

With the sense of control and certainty taken from us, it’s easy for our decisions to be overcome by what we fear. With that in mind, it’s important to make time to find new activities that will help to activate the feel-good chemicals in our brains.

These seven activities can be practised while experiencing physical distancing. They are proven to slow down the stress response and boost your mood.

-

Take a nature break

2,500 years ago, Hippocrates, the Ancient Greek Physician and so-called ‘father of medicine’, said “walking is man’s best medicine”. Having invented the Hippocratic oath, he certainly wouldn’t lie! The moment you step outside the concrete jungle and into nature, your body shows its gratitude by releasing serotonin, a mood-regulating neurotransmitter. We are encouraged to stay at home. But if you have a backyard or nature reserve nearby, take regular breaks from the computer for fresh air or to use these spaces for exercise. Just be mindful to ensure you’re following recommendations and maintaining safe physical distancing in the process.

-

Move your body

Physical exercise acts like a power booster, it increases endorphins, the ‘peptide good guys’ that reduce pain perception and trigger positivity. Literally, happy days. Running and walking are great ways to shift pent-up energy. If you’re in self-isolation, try skip rope, something you could make, at a stretch, with a plastic cord or clothes line. A 32 year old French man ran the entire length of a marathon on his balcony during lockdown! Give yourself a tech-tox and move your body, ideally in nature, even if it’s just for ten minutes.

-

Take a bath

Many people experience a sense of calm around water and it’s no surprise if you consider the fact that our bodies are 60% water, and our brains more than 70%. Both Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine believe that the water element is crucial to rebalancing the body. With many beaches closed, look to what you can do within your own home. Fill up the bathtub and immerse your body in water. To super charge the experience you might even soften the lighting or drop in some essential oils to stimulate your senses.

-

Have a laugh

Laughter triggers the release of dopamine into the brain’s reward centre, giving you a high that lowers stress levels and increases your receptivity to pleasure. What may come as a surprise is that research also suggests that simply anticipating a laugh can have a similarly powerful effect. The expectation of something funny turns on our parasympathetic response system. So, it seems there’s never been a better time to practise your best ‘dad jokes’ on friends or the kids. There’s plenty of funny fodder available on streaming services. Check out Vulture’s list of the 50 best comedies on Netflix.

-

Practice yoga

The benefits of this ancient practise go far beyond the physical. In a yoga class, the combination of breath awareness and asana (postures) act to still the fluctuations of the mind and deepen your mind-body connection. Studies have shown that just a single one-hour yoga class can have a positive biochemical impact on your brain. Regular practise can reduce stress, anxiety, post traumatic stress disorder and depression. With traditional classes currently cancelled, many yoga teachers and studios are live streaming offerings, by donation or free of charge, for you to practise from home.

6. Listen to some tunes

Music makes your brain sing. You know that happy rush you get when your favourite song comes on the radio? It’s a chemical romance, one that lets off steam, injects the good vibes and let’s be real, is just a whole lot of fun. When music triggers your pleasure receptors dopamine is released into the striatum, the same part of the brain that responds to sex, chocolate, and is stimulated by artificial narcotics like cocaine. Research has also found that that some music has meditative qualities and can positively impact stress reduction and overall happiness. Fun fact: neuroscientists have found that listening to this song can reduce anxiety by up to 65%.

-

Dance it out

Dancing, like any other physical activity, releases neurotransmitters and endorphins to alleviate stress. Combining the dopamine response stimulated by music with these endorphins has the potential to supercharge your positivity. Plus, it’s almost certain that you’ll laugh along the way. Right now, you really can dance around the house like no one is watching. Prefer company? Have a virtual dance party. Many companies are rolling out video call dance breaks to manage the impacts of social isolation on extroverts in the workforce. Whether you want to do it with work, or friends, it’s easy to set up a time, pick a song, and all jump on a video call to dance it out together.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: The principle of charity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

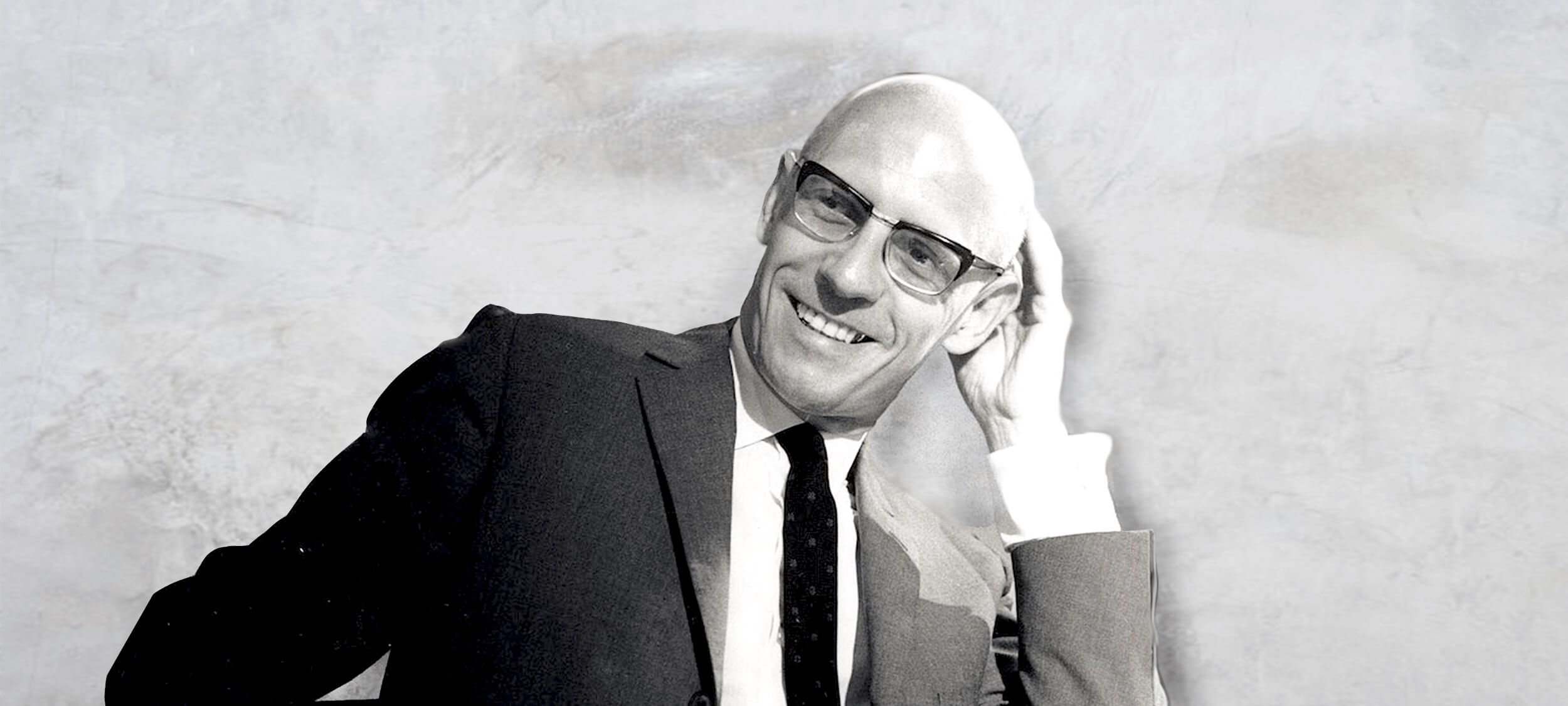

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

BY Karina Morgan

Karina is a communications specialist, avid hiker and volunteer primary ethics teacher, with a penchant for the written word.

Moving work online

Moving work online

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Talya Wiseman The Ethics Centre 10 APR 2020

As the COVID-19 dominos continue to fall, many organisations are scrambling to rethink the way they work. These changes are happening in real time; on a scale both unprecedented and unpredicted.

The last pandemic of this nature, the Spanish Flu, occurred 100 years ago – well before anyone had dreamed up the internet, computers and video conferencing. In 2020, advances in technology, such as international flights, have allowed this virus to spread at a much faster rate. However, they have also afforded many organisations the opportunity to pivot their operations online.

Schools and universities have, for the most part, managed this at an incredibly fast pace. With barely any notice, teachers have become adept at using online delivery platforms and are coming up with new ways to engage their students online.

Students are able to continue their same classes via platforms like Zoom or Microsoft Teams; all the while knowing that the rest of their class is right there, learning alongside them.

Now that all but essential workers are urged to stay at home, ideas about working environments have also been forced to alter at an unusually rapid pace. For example, workplaces and teams have begun to adapt to meeting online. A popular meme doing the rounds at the moment depicts a scenario 40 years from now when a grandchild asks their grandparent with wonder “Go to work? You used to actually GO to work?”

It is incredible to see how many fundamental changes and shifts in thinking have occurred in such a short space of time. We simply had neither the time nor the opportunity to incorporate long policy discussions, carefully timed rollout plans or trial periods. Many organisations that previously assumed they needed a common workplace are now questioning the validity of this assumption.

What happens next?

The big question is this: when all of this is over and we return to normal, what will normal look like? Will organisations revert to their old ways? Or will we have seen the value in new patterns of working? Our eyes have been opened through this experience. Our assumptions about the nature of work have been challenged. Having reorientated towards online workplaces, will it be so easy to pivot back? And will we want to?

There are certainly benefits to workplaces accepting remote working as a viable option. Parents and carers, who previously struggled to convince their employers that they could effectively work from home, will likely find this argument much easier to make. If people have been able to fulfill their work duties in these most trying times, clearly it will be easier for them to continue to do so when it is an option they are choosing.

The stigma of working from home has rapidly been removed. It should no longer be seen as the ‘lesser’ option compared to attending an office. Organisations are finding innovative ways to ensure staff feel supported while working from home; while also maintaining expectations of staff – wherever they happen to be located.

The role of the physical workplace

However, there is a risk in realising just how easy it is to do things online. The role that work plays for individuals is much more than just providing an income. Work is also about fulfilment; it is about social interaction. The best initiatives can arise from bouncing ideas around with colleagues. Families can laugh together at the dinner table when sharing work stories and funny moments that occurred at the office. Colleagues can celebrate each other’s success and commiserate together when things don’t go as planned. Work is about so much more than ‘work.’

One of our principles, here at The Ethics Centre, is to “know your world and know yourself”. We believe in the importance of questioning who we are and being conscious of what we do. If the nature of work is fundamentally to change, we must recognise what we are giving up, as well as the opportunities that may arise. Just because we were rushed into this new reality doesn’t mean we can’t carefully consider the best way to move on from it.

Let’s not just fall back into old patterns. Let’s use this as an opportunity for questioning and for finding a better ‘normal’. That might well be a workplace that embraces flexible arrangements and is open to non-traditional office environments, while at the same time never losing touch with deeply human moments and interactions.

Perhaps we will realise that work, regardless of industry, is about purpose, fulfilment and human interaction.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Capitalism is global, but is it ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

WATCH

Relationships

How to have moral courage and moral imagination

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

BY Talya Wiseman

is an experienced educator who has worked extensively in both the formal and experiential education space. At The Ethics Centre, Talya is the Educational Program Manager creating innovative, engaging and quality ethics-focused education

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Dennis Gentilin 9 APR 2020

Crises, especially as momentous as this one, have a habit of exposing leaders. At worst, they expose incompetence and self-interest. At best, they reveal courage, resilience and deep concern for others. It is the latter that is the hallmark of ethical leadership.

Make no mistake, these are challenging times. There are potentially some dark days ahead. Humanity has not faced a perilous situation of this magnitude in my lifetime.

Unfortunately, ethical leadership is not something that can be ‘switched’ on at will. In trying times, one cannot simply dust off the ethical leadership manual and, like a chameleon, transform one’s approach. The reason for this is that ethical leadership is honed through many years of practice.

Ethics is a long game

This is not a new idea. Aristotle described ethical virtue as a “hexis” – a state or disposition – that is shaped by our habits. We come to be ethical by acting ethically, consistently being guided by an ethical framework when making choices, regardless of how difficult this might be given the prevailing circumstances. This is what it means to be a person with integrity.

For this reason the COVID-19 pandemic will (and in some cases already has) reveal what leaders believe to be good (their values) and right (their principles). More importantly, it will reveal how committed they are to their ethical core. Those who have failed to make ethical practice a daily habit will find it difficult. They may already have stumbled or are perhaps struggling to win the trust of sceptical followers. For those who have made integrity central to their leadership, the turbulent waters will be somewhat easier to navigate. Making the ethical choice will come more instinctively.

There is also the possibility that ethical leadership will emerge in the current crisis from the most unlikely of places. People whom we may have thought were not cut out to deal with a crisis or a thrust into a position of leadership will rise to the occasion. Perversely, moments like these, instead of paralysing leaders, can provide greater clarity on what is the ‘right’ thing to do. The path one must take, although rocky, lights up and is clearly signed. A leader comes into their own.

Ethical leadership, not perfection

All this being said, one thing that we should not (and cannot) expect is ethical perfection. In situations like these where there are excruciating trade-offs associated with many decisions, ethical perfection cannot be defined. The available choices are evenly balanced, providing a myriad of possible outcomes that all have considerable merit. It would therefore be preposterous to think that any leader in these circumstances, no matter how ethical, will get everything ‘right’. We should respect those who are being called upon to make extraordinarily difficult decisions, with imperfect information, in a highly dynamic environment.

However, there are some minimal expectations we should expect from our leaders. We should expect a degree of candour and honesty, accepting that in some cases full transparency will do more harm than good. We should expect that the safety of people – particularly the most vulnerable – is prioritised, accepting that there will be unfortunate loss of life. Above all, we should expect leaders to act with sincerity, rely on the best available evidence and display ethical competence. ‘Winging it’, ‘intuition’ and ‘common sense’ are not enough.

We all have a role to play

We should also understand that ethical leadership is not reserved for those who sit highest in the hierarchy, especially in unprecedented moments like these. This is something that can’t be underestimated. Ethical leadership will need to emerge at every level of society if we are to find a way through what will be some very difficult weeks and months ahead. Do not discount our essential role as ethical citizens.

Jon Haidt, a professor of ethical leadership at the Stern School of Business at NYU, talks about how morality “blinds and binds”. It can evoke the passions and bind people around a common cause. However, in doing so, it can breed dogmatism and drive us into our ideological camps, blinding us to our common humanity.

For the first time in a while, the coronavirus has created a present and common cause that all of humanity can bind to. It will test our leaders and in doing so reveal those who make ethics more than a word in their by-line. It will produce benevolent and heroic acts among citizens that extreme circumstances like these so often educe. And hopefully, by producing a cause we can all be bound by, it will dampen some of the tribalism and self-interest that has been an unfortunate feature of some sectors of our society in recent times.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership