Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 18 SEP 2019

I recently came across a quote from philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau, talking about what it means to live well:

“To live is not to breathe but to act. It is to make use of our organs, our senses, our faculties, of all the parts of ourselves which give us the sentiment of our existence. The man who has lived the most is not he who has counted the most years but he who has most felt life. Men have been buried at one hundred who have died at their birth.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I found myself nodding sagely along as I read. Because life isn’t something we have, it’s something we do. It is a set of activities that we can fuse with meaning. There doesn’t seem much value to living if all we do with it is exist. More is demanded of us.

Rousseau’s quote isn’t just sage; it’s inspiring. It makes us want to live better – more fully. It captures an idea that moral philosophers have been exploring for thousands of years: what it means to ‘live well’ – to have a life worth living.

Unfortunately, it also illustrates a bigger problem. Because in our current reality, not everyone is able to live the way Rousseau outlines as being the gold standard for Really Good LivingTM.

This is a reality that professionals working in the aged care sector should know all too well. They work directly with people who don’t have full use of their organs, their faculties or their senses. And yet when I presented Rousseau’s thought to a room full of aged care professionals recently, they felt the same inspiration and agreement that I’d felt.

That’s a problem.

If the good life looks like a robust, activity-filled life, what does that tell us about the possibility for the elderly to live well? And if we don’t believe that the elderly can live well, what does that mean for aged care?

If you have been following the testimony around the Aged Care Royal Commission, you’ll be aware of the galling evidence of misconduct, negligence and at times outright abuse. The most vulnerable members of our communities, and our families, have been subject to mistreatment due in part to a commercial drive to increase the profitability of aged care facilities at the expense of person-centred care .

Absent from the discussion thus far has been the question of ‘the good life’. That’s understandable given the range of much more immediate and serious concerns facing the aged care sector, but it is one that cannot be ignored.

In 2015, celebrity chef and aged care advocate Maggie Beer told The Ethics Centre that she wanted “to create a sense of outrage about [elderly people] who are merely existing”. Since then she has gone on to provide evidence to the Royal Commission, because she believes that food is about so much more than nutrition. It’s about memory, community, pleasure and taking care and pride in your work.

Consider the evidence given around food standards in aged care. There have been suggestions that uneaten food is being collected and reused in the kitchens for the next meal; that there is a “race to the bottom” to cut costs of meals at the expense of quality, and that the retailers selling to aged care facilities wildly inflate their prices. The result? Bad food for premium prices.

We should be disturbed by this. This food doesn’t even permit people to exist, let alone flourish. It leaves them wasting away, undernourished. It’s abhorrent. But what should be the appropriate standard for food within aged care? How should we determine what’s acceptable? Do we need food that is merely nutritious and of an acceptable standard, or does it need to do more than that?

Answering that question requires us to confront an underlying question:

Do we believe aged care is simply about providing people’s basic needs until they eventually die?

Or is it much more than that? Is it about ensuring that every remaining moment of life provides the “sentiment of existence” that Rousseau was concerned with?

When you look at the approximately 190,000 words of testimony that’s been given to the Royal Commission thus far, a clear answer begins to emerge. Alongside terms like ‘rights’, ‘harms’ and ‘fairness’ –which capture the bare minimum of ethical treatment for other people – appear words such as ‘empathy’, ‘love’ and ‘connection’. These words capture more than basic respect for persons, they capture a higher standard of how we should relate to other people. They’re compassionate words. People are expressing a demand not just for the elderly to be cared for, but to be cared about.

Counsel assisting the Royal Commission, Peter Gray QC, recently told the commission that “a philosophical shift is required, placing the people receiving care at the centre of quality and safety regulation. This means a new system, empowering them and respecting their rights.”

It’s clear that a philosophical shift is necessary. However, I would argue that what’s not clear is if ‘person-centred care’ is enough. Because unless we are able to confront the underlying social belief that at a certain age, all that remains for you in life is to die, we won’t be able to provide the kind of empowerment you felt reading Rousseau at the start of this article.

There is an ageist belief embedded within our society that all of the things that make life worth living are unavailable to the elderly. As long as we accept that to be true, we’ll be satisfied providing a level of care that simply avoids harm, rather than one that provides for a rich, meaningful and satisfying life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Ethics Reboot: 21 days of better habits for a better life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 22 AUG 2019

What was your first lesson in courage? The first time someone told you to be brave – or explained to you that fear was something to be overcome, not something that should control you?

I can’t remember the very first moment I encountered the idea of courage, but the first I can remember – and the one that has stayed with me the longest – is this: “being brave doesn’t mean we looking for trouble.”

It is, of course, from Disney’s The Lion King. Mufasa, moments after saving his son, Simba, from ravenous hyenas, chastises his boy for putting himself and his friend in danger.

Simba’s journey in The Lion King is really a treatise on courage. From a reckless, thrill-seeking child, Simba loses his father and, believing himself responsible, flees from the social judgement that might bring.

Simba takes his father’s lesson too far: he doesn’t look for trouble, but when it finds him, he runs from it. He lives as an exile in a hedonistic paradise. Comfortable, apathetic, safe. For all his physical prowess, Simba is a coward.

Of course, by the end of the film Simba has found courage. He accepts his identity as the true king, admits his shame publicly, defeats Scar (his true enemy) and takes his place in the circle of life, complete with staggering musical accompaniment.

As well as having a soundtrack that’s jam-packed with bangers, it turns out the Lion King has a strong philosophical pedigree.

Courage as a virtue

The Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that courage was as virtue – a marker of moral excellence. More specifically, it was the virtue that moderated our instincts toward recklessness on one hand and cowardice on the other.

He believed the courageous person feared only things that are worthy of fear. Courage means knowing what to fear and responding appropriately to that fear.

For Aristotle, what mattered isn’t just whether you face your fears, but why you face them and what it is that you fear.

There is something important here. Your reasons for overcoming fear matter. They can be the difference between courage, cowardice and recklessness.

For instance, in Homer’s Iliad, the Trojan prince Hector threatens to punish any soldier he sees fleeing from the fight. In World War I, soldiers who deserted were executed.

Were these soldiers courageous? The only reason they risk death from the enemy is because they’re guaranteed to be killed if they don’t. The fear of death is still what drives them.

More courageous, says Aristotle, is the soldier who freely chooses to fight despite having no personal reason to do so besides honour and nobility. In fact, for Aristotle, this is the highest form of courage – it faces the greatest fear (death) for the most selfless reason (the nation).

Of course, Aristotle was an Ancient Greek bloke, so we should take his prioritising of military virtue with a grain of salt. Is death at war really to be so highly prized?

For one thing, in a culture like Ancient Greece or Troy, the failure to be an excellent warrior would be met with enormous dishonour. How many soldiers went to war for fear of dishonour? Is dishonour something to be rightly feared? And if so, whose dishonour should we fear?

Surely not that of a society whose moral compass prioritises victory over justice – risking your life to support a cause like that is reckless.

If courage means fearing dishonour from those who are morally corrupt, then a courageous enemy is worse than a cowardly one. Courage becomes like a superpower – making some people into heroes and others villains.

But there’s a deeper reason to doubt Aristotle’s idea of the highest courage. Whilst most of us do fear death, it’s not clear that it’s the thing we fear most. Even if we do fear death, we have a range of different reasons for doing so.

Our deepest fears

Perhaps my most visceral fear is of drowning. The thought of it is enough to make me feel short of breath. Perhaps that’s because of an experience when I was younger – when I was overseas I learned that my Dad nearly drowned. It was perhaps the first time I really had to come to grips with the fact he was mortal – and so was I – and all that I loved.

Today, I fear death because it would mean never seeing my children grow up. Never holding them one last time. Seeing my son’s first days at school. Hearing my daughter’s first words.

Worse, I wouldn’t be sure that they were safe and flourishing. If someone could guarantee that, perhaps I’d be less fearful of death. It’s not the death I fear; it’s what it represents: an incomplete life, failed commitments, unending love brought to a close.

Aristotle didn’t consider courage in the face of existential anxieties like these. What does it mean to live courageously in a world where all our loves, passions and projects expose us to pain and loss? To live is to have a nerve constantly exposed to the world – always vulnerable to suffering.

The French psychoanalyst and philosopher Anne Dufourmantelle argues that risk is an inherent part of living fully in the world. Risk-free living, she argues, is not living at all. Courage is as much about living despite knowing the exposed nerve of love and passion could trigger chest-tightening pain at any moment.

Yet so often we close ourselves from the world to keep ourselves safe. We self-censor not because we think we might be wrong, but because we fear upsetting the wrong person. We withdraw from relationships because we don’t want to be the one to take the leap. We tell ourselves stories in the shower of all the things we could do – could be – if only the world let us.

Existentialist philosophers have a name for this kind of self-deception: bad faith – a kind of failure to engage with the world as it really is and accepting ourselves as we are and as we could be.

Too often we think of courage purely as facing up to our fears. What that misses is how deeply connected our fears are with deeper beliefs about who we are, who we want to be, who we love and what we wish the world was.

A courageous truth

Maybe the truth of courage is that it’s all about truth. It’s about looking reality in the face and having the force of will not to turn away, despite the pain, the unpleasantness and the risk.

Maybe it’s about looking for long enough to see the joy in the pain; the beauty in the ugliness and the comfort that lies in the little risks we take every day.

Perhaps it’s only then we can know what’s worth dying for – and what’s worth living for. Certainly, Dufourmantelle gives us some hope of this. In 2017, she died in rough seas off the coast of France, having swum out to rescue two children caught in the surf.

The children survived, but how many of us would have dived in? How many would have hoped for a lifeguard? A stronger swimmer? For the children to rescue themselves?

I want to encourage you to think: are there rough waters you’re not jumping into for fear of the waves? Do you tend to dive in without counting the costs?

Dr Matt Beard was the host of The Ethics of Courage, alongside Saxon Mullins and Benjamin Law at The Ethics Centre on 21 August. This is a transcript of his opening address.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Power and the social network

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 30 JUL 2019

Until last week, you would have been forgiven for thinking a meme couldn’t trigger fears about international security.

But since the widespread concerns over FaceApp last week, many are asking renewed questions about privacy, data ownership and transparency in the tech sector. But most of the reportage hasn’t gotten to the biggest ethical risk the FaceApp case reveals.

What is FaceApp?

In case you weren’t in the know, FaceApp is a ‘neural transformation filter’.

Basically, it uses AI to take a photo of your face and make it look different. The recent controversy centred on its ability to age people, pretty realistically, in just a short photo. Use of the app was widespread, creating a viral trend – there were clicks and engagements to be made out of the app, so everyone started to hop on board.

Where does your data go?

With the increasing popularity comes increasing scrutiny. A number of people soon noticed that FaceApp’s terms of use seemed to give them a huge range of rights to access and use the photos they’d collected. There were fears the app could access all the photos in your photo stream, not just the one you chose to upload.

There were questions about how you could delete your data from the service. And worst of all for many, the makers of the app, Wireless Labs, are based in Russia. US Minority Leader Chuck Schumer even asked the FBI to investigate the app.

The media commentary has been pretty widespread, suggesting that the app sends data back to Russia, lacks transparency about how it will or won’t be used and has no accessible data ethics principles. At least two of those are true. There isn’t much in FaceApp’s disclosure that would give a user any sense of confidence in the app’s security or respect for privacy.

Unsurprisingly, this hasn’t amounted to much. Giving away our data in irresponsible ways has become a bit like comfort eating. You know it’s bad, but you’re still going to do it.

The reasons are likely similar to the reasons we indulge other petty vices: the benefits are obvious and immediate; the harms are distant and abstract. And whilst we’d all like to think we’ve got more self-control than the kids in those delayed gratification psychology experiments, more often than not our desire for fun or curiosity trumps any concern we have over how our data is used.

Should you be worried?

Is this a problem? To the extent that this data – easily accessed – can be used for a range of goals we likely don’t support, yes. It also gives rise to a range of complex ethical questions concerning our responsibility.

Let’s say I willingly give my data to FaceApp. This data is then aggregated and on-sold in a data marketplace. A dataset comprising of millions of facial photos is then used to train facial recognition AI, which is used to track down political dissidents in Russia. To what extent should I consider myself responsible for political oppression on the other side of the world?

In climate change ethics, there is a school of thought that suggests even if our actions can’t change an outcome – for instance, by making a meaningful reduction to emissions – we still have a moral obligation not to make the problem worse.

It might be true that a dataset would still be on sold without our input, but that alone doesn’t seem to justify adding our information or throwing up our arms and giving up. In this hypothetical, giving up – or not caring – means abandoning my (admittedly small) role in human rights violations and political injustice.

A troubling peek into the future

In reality, it’s really unlikely that’s what FaceApp is actually using your data to do. It’s far more likely, according to the MIT Technology Review, that your face might be used to train FaceApp to get even better at what it does.

It might use your face to help improve software that analyses faces to determine age and gender. Or it might be used – perhaps most scarily – to train AI to create deepfakes or faces of people who don’t exist. All of this is a far cry from the nightmare scenario sketched out above.

But even if my horror story was accurate, would it matter? It seems unlikely.

By the time tech journalists were talking about the potential data issues with FaceApp, millions had already uploaded their photos into the app. The ship had sailed, and it set off with barely a question asked of it. It’s also likely that plenty of people read about the data issues and then installed the app just to see what all the fuss is about.

Who is responsible?

I’m pulled in two directions when I wonder who we should hold responsible here. Of course, designers are clever and intentionally design their apps in ways that make them smooth and easy to use. They eliminate the friction points that facilitate serious thinking and reflection.

But that speed and efficiency is partly there because we want it to be there. We don’t want to actually read the terms of use agreement, and the company willingly give us a quick way to avoid doing so (whilst lying, and saying we have).

This is a Faustian pact – we let tech companies sell us stuff that’s potentially bad for us, so long as it’s fun.

The important reflection around FaceApp isn’t that the Russians are coming for us – a view that, as Kaitlyn Tiffany noted for Vox, smacks slightly of racism and xenophobia. The reflection is how easily we give up our principled commitments to ethics, privacy and wokeful use of technology as soon as someone flashes some viral content at us.

In Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology, Simon Longstaff and I made the point that technology isn’t just a thing we build and use. It’s a world view. When we see the world technologically, our central values are things like efficiency, effectiveness and control. That is, we’re more interesting in how we do things than what we’re doing.

Two sides of the story

For me, that’s the FaceApp story. The question wasn’t ‘is this app safe to use?’ (probably no less so than most other photo apps), but ‘how much fun will I have?’ It’s a worldview where we’re happy to pay any price for our kicks, so long as that price is hidden from us. FaceApp might not have used this impulse for maniacal ends, but it has demonstrated a pretty clear vulnerability.

Is this how the world ends, not with a bang, but with a chuckle and a hashtag?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We need to talk about ageism

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

A framework for ethical AI

WATCH

Relationships

What is ethics?

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 27 JUN 2019

I spent this weekend hearing from all corners what a wonderful Dad I am. It was quite lovely, and I’d very much like for it to happen more often.

This weekend I was effectively a sole parent as my wife was rendered bedridden by illness. For two days, I was in charge of a seven-week-old baby and almost three-year-old toddler.

Miracle of miracles – they didn’t die. In fact, I managed to feed and bath them, plus made sure they slept. I even packed them both up in the car and took them to a birthday party and back again.

An uneven playing field?

This is the Herculean labour that earned me torrents of praise. In fact, it didn’t just earn me praise – people messaged my bed-ridden wife not only with well-wishes, but to tell her how lucky she was. Oh, to have a co-parent like him!

I can’t imagine how frustrating these messages are for her to receive. I spend four days a week at work, which means she has the kids solo for those four days. In that time, she takes them to doctors appointments, libraries, playgrounds, feeds them, does an enormous amount of housework and manages, somehow, to keep herself alive.

What I did this weekend amounts to about 50% of what she does week in, week out. Guess how many people have texted me to say how lucky I am?

Less effort but more praise?

The double-standards here are staggering. They’re also incredibly unfair. To see someone receive more praise for less effort is profoundly invalidating – something about which women have been increasingly outspoken. It also makes social progress difficult – the more we see men’s modest contributions as incredibly generous and praiseworthy, the harder it is for women to ask more (even though what they’re asking for is entirely reasonable – lest we forget the last census, which reports that one in four men do zero housework).

What’s been less widely addressed is just how bad this double-standard is for men. I, and I would imagine most dads, want to be a great parent and partner. But that’s not helped by receiving praise for every little thing I do – it gives a false impression of exactly where I am on the spectrum: am I doing a great job, a terrible one, or just a mediocre one? It’s hard to tell through all the well-intended, generous praise.

Praise can be a double-edged sword

Praise is a powerful tool for behavioural change and moral growth. It can be used to help encourage people to do the right thing, remind them when they’ve slipped up and point out whose behaviour is a good example to follow. But that only works if the people offering praise have a clear idea of what’s actually worth praising – the praise in itself means nothing if it’s not properly calibrated.

And this is why the kind of praise I received is a problem. Taking care of your children is not exceptional, parenting-wise. It’s just what you’re supposed to do. Ditto, doing the laundry, cooking for the family, organising tradesmen to come and fix the house, planning birthday parties and all the other domestic activities that women do thanklessly and men do heroically. Or, at least, some men – again, one in four do no chores.

The sheer mass of men not pulling their weight makes it so easy for mediocrity to look amazing. The comedian Hannah Gadsby talks about how there is a line in the sand between ‘good men’ and ‘bad men’, but how it tends to be men who determine where that line is drawn. Similarly, as a dad I can always find a dad who isn’t doing quite as much as me and use that to determine how much I’m contributing. And, good news, I’m likely to have my self-image reinforced by praise and gratitude at every turn.

What’s more, there’s a social message embedded in that praise. Just as the text message said, women are told they should be grateful to have a partner who is not one of those who does no housework. Maybe he doesn’t do much – but it’s not nothing, so lucky you. Obviously, these narratives are very bad for equality.

They’re also, as I said, very bad for men who want to be great partners, parents and people. The school of ethical thought that most focusses on the kinds of questions I’m asking here is known as ‘virtue ethics’. Virtue ethics focusses on the kinds of character traits that are most likely to make people good and the kinds of activities that are likely to develop and model those characteristics.

Thinking in this way, we might be inclined to say that being a good parent requires the development of a bunch of different character traits – like compassion – and then practising those character traits by, say, holding a child gently while they have an emotional meltdown.

However, one the key ways we learn the virtues is by emulating role models. That means who we single out as role models is really important and – as we’ve said – what counts as ‘exemplary’ parenting can, for dads, be a pretty low bar. Not only does this leave a lot of cleaning up for the co-parents of men who have been sold this story, it undermines their ability to become who they really want to be: great dads.

What do we do about this? Well, for one thing, we should stop giving blokes a cookie just because they showed up. Reserve our praise for when it’s really deserved – and then hand it out equally. Great parenting is great parenting – just because it’s more common to see women in that role doesn’t mean they’re unworthy of praise.

Second, I think men have got to be critical about the kinds of feedback they receive. Before letting it stoke our egos, we need to consider whether or not it’s warranted. In an age of allyship and leaning in, social brownie points are pretty easy to come by for men. But we need to hold ourselves to a higher standard. As the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah writes, “a person of honour cares first of all not about being respected but about being worthy of respect.”

Matt Beard is a tired, okay dad.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Respect

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Employee activism is forcing business to adapt quickly

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Begging the question

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

How to build good technology

How to build good technology

WATCHBusiness + LeadershipClimate + EnvironmentScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 2 MAY 2019

Dr Matthew Beard explains the key principles to guide the development of ethical technology at the Atlassian 2019 conference in Las Vegas.

Find out why technology designers have a moral responsibility to design ethically, the unintended ethical consequences of designs such as Pokemon Go, and the the seven guiding principles designers need to consider when building new technology.

Whether editing a genome, building a driverless car or writing a social media algorithm, Dr Beard says these principles offer the guidance and tools to do so ethically.

Download ‘Ethical By Design: Principles For Good Technology ‘

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Feeling rules: Emotional scripts in the workplace

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Is technology destroying your workplace culture?

Is technology destroying your workplace culture?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 6 APR 2019

If you were to put together a list of all the buzzwords and hot topics in business today, you’d be hard pressed to leave off culture, innovation or disruption.

They might even be the top three. In an environment of constant technological change, we’re continuously promised a new edge. We can have sleeker service, faster communication or better teamwork.

This all makes sense. Technology is the future of work. Whether it’s remote work, agile work flows or AI enhanced research, we’re going to be able to do more with less, and do it better.

For organisations who are doing good work, that’s great. And if those organisations are working for the good of society (as they should), that’s great for us all.

Without looking a gift horse in the mouth though, we should be careful technology enhances our work rather than distracting us from it.

Most of us can probably think of a time when our office suddenly had to work with a totally new, totally pointless bit of software. Out of nowhere, you’ve got a new chatbot, all your info has been moved to ‘the cloud’ or customer emails are now automated.

This is usually the result of what the comedian Eddie Izzard calls “techno-joy”. It’s the unthinking optimism that technology is a cure for all woes.

Unfortunately, it’s not. Techno-joyful managers are more headache than helper. But more than that, they can also put your culture – or worse, your ethics – in a tricky spot.

Here’s the thing about technology. It’s more than hardware or code. Technology carries a set of values with it. This happens in a few ways.

Techno-logic

All technology works through a worldview we call ‘techno-logic’. Basically, technology aims to help us control things by making the world more efficient and effective. As we explained in our recent publication, Ethical by Design:

Techno-logic sees the world as though it is something we can shape, control, measure, store and ultimately use. According to this view, techno-logic is the ‘logic of control’. No matter the question, techno-logic has one overriding concern: how can we measure, alter, control or use this to serve our goals?

Whenever you’re engaging with technology, you’re being invited and encouraged to see the world in a really narrow way. That can be useful – problem solving happens by ignoring what doesn’t matter and focussing on what’s important. But it can also mean we ignore stuff that matters more than just getting the job done as fast or effectively as we can.

A great example of this comes from Up in the Air, a film in which Ryan Bingham (George Clooney) works for a company who specialise in sacking people. When there are mass layoffs to be made, Bingham is there. Until technology comes to call. Research suggests video conferencing would be cheaper and more effective. Why fly people around America when you can sack someone from the comfort of your own office?

As Bingham points out, you do it because sometimes making something efficient destroys it. Imagine going on an efficient date or keeping every conversation as efficient as possible. We’d lose something essential, something rich and human.

With so much technology available to help with recruitment, performance management and customer relations, we need to be mindful that technology is fit for purpose. It’s very easy for us to be sucked into the logic of technology until suddenly, it’s not serving us, we’re serving it. Just look at journalism.

Drinking the affordance Kool-Aid

Journalism has always evolved alongside media. From newspaper to radio, podcasting and online, it’s a (sometimes) great example of an industry adapting to technological change. But at times, it over adapts, and the technological cart starts to pull the journalistic horse.

Today, online articles are ‘optimised’ to drive engagement and audience. This means stories are designed to hit a sweet spot in word count to ensure people don’t tune out, they’re given titles that are likely to generate clicks and traffic, and the kinds of things people are likely to read tend to get more attention.

A lot of that is common sense, but when it turns out that what drives engagement is emotion and conflict, this can put journalists in a bind. Are they impartial reporters of truth, lacking an audience, or do they massage journalistic principles a little so they can get the most readers they can?

I’ll leave it to you to decide which way journalism as an industry has gone. What’s worth noting is that many working in media weren’t aware of some of these changes whilst they were happening. That’s partly because they’re so close to the day-to-day work, but it can also be explained by something called ‘affordance theory’.

Affordance theory suggests that technological design contains little prompts, suggesting to users how they should interact with it. They invite users to behave in certain ways and not others. For example, Facebook makes it easier for you to respond to an article with feelings than thinking. How? All you need to do to ‘like’ a post is click a button but typing out a thought requires work.

Worse, Facebook doesn’t require you to read an article at all before you respond. It encourages quick, emotional, instinctive reactions and discourages slow thinking (through features like automatic updates to feeds and infinite scroll).

These affordances are the water we swim in when we’re using technology. As users, we need to be aware of them, but we also need to be mindful of how they can affect purpose.

Technology isn’t just a tool, it’s loaded with values, invitations and ethical judgements. If organisations don’t know what kind of ethical judgements are in the tools they’re using, they shouldn’t be surprised when they end up building something they don’t like.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The case for reskilling your employees

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The anti-diversity brigade is ruled by fear

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Managing corporate culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

‘Hear no evil’ – how typical corporate communication leaves out the ethics

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Want your kids to make good decisions? Here’s what they need to learn

Want your kids to make good decisions? Here’s what they need to learn

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Matthew Beard 12 DEC 2018

Ask just about any parent what they want for their children and they’ll give you roughly the same answers: we want our kids to be happy, healthy and – perhaps most importantly – good.

For many parents, the goal is to raise children who are better than they are, contribute positively to the world around them, challenge cruelty, injustice and ignorance in the world and make a positive difference in other people’s lives.

Basically, what they’re wanting is that their kids grow up to be ethical people. So, if that’s what so many of us want, it’s worth understanding exactly what ethics is and how we might light the ethical spark in the next generation.

Ethics is a branch of philosophy – it asks questions about the nature of goodness, what makes something right and wrong, and what makes life worth living. As a branch of philosophy, it also leaves no stone unturned. It interrogates any and every claim about what’s right, what’s wrong and what’s ‘normal’.

Whenever we make a choice, we change the world in some small way. Before us are a whole bunch of different possible worlds – it’s up to us to decide which one we’ll turn into reality. Ethics helps us make sure we’re choosing the best of those possible worlds, but it takes practice to do it well.

That means if we’re going to help our kids be ethical people, we need to model ethical thinking in our homes and classrooms, on sports fields and video games and wherever kids are making decisions.

But how do we do it? Here are a few tried and true techniques the ABC’s Short & Curly team have used over the last few years.

1. Don’t be afraid to say ‘I don’t know’

It can be scary to say “I don’t know” – especially when we’re having a conversation with kids. As adults, we’re supposed to have all the answers, right? The problem is, sometimes we don’t. And neither do the young people we’re talking to.

The more we pretend we know it all, the more self-conscious others feel about engaging us in a real conversation, or worse – disagreeing with us! Philosophers use discussions and debate as a team activity – we use disagreement and criticism as a way to work together to find out what’s true.

What’s more, our beliefs about how the world works are often conditioned on what we’ve learned or been told is normal. What we know about fairness, honesty or whatever the topic is might not be the final answer – it could be conditioned by norms and beliefs we’ve been conditioned to believe, even if they don’t hold up to close analysis.

2. Be imaginative

Martha Nussbaum, one of the world’s pre-eminent philosophers, says “you can’t really change the heart without telling a story.” We’re narrative creatures – we’ve always used parables, fables, literature and film as ways of understanding the world around us.

Philosophers have tested their ideas through thought experiments and hypotheticals throughout time. They’re super weird, but they make for great road-trip fodder or dinner table debates.

Ethical reflection demands imagination. It requires us to be able to understand experiences we haven’t lived through and to empathise with people who might be radically different to us.

The next time you’re reading a book or watching a movie with your young one, that’s a moment for reflection. Did those characters do the right thing? How do you think that person felt? Would it have been OK if they’d broken that promise?

3. Don’t shut down a question

Some of our favourite one liners are actually really good ways of undermining ethical conversations. “Everybody does it”, “because I said so” and “you’ll understand when you’re older” are good examples. They rely on authority, tradition or experience as ways to cut off what might be a more productive conversation.

Sometimes, there’s not time for an ethical discussion, but rather than shutting it off with a one-liner, make a commitment to talk about it in more detail later, when you’ve got more time to explain yourself.

4. Question your assumptions

Our minds love telling stories – and we hate plot holes. If we don’t have the full story, we’ll often fill in the gaps with assumptions or inferences that don’t capture the full picture. Ethical conversations work best when they start by questioning what we think we know for sure. Are we starting our discussion on a good foundation?

5. Be curious and research

As well as checking our assumptions, ethics requires us to be curious and informed about the world around us. As much as many philosophers would beg to differ, we can’t understand the world from an armchair.

We need to do some research and uncover relevant facts. Bonus – while you’re doing some research together, you might be able to work together to understand the difference between a fact and an opinion, spot dodgy sources or filter out fake news.

6. Listen to and test your emotional responses

Our emotions are an important part of the way we make judgements, but they can sometimes run wild and lead us astray. Just because we find something disgusting, offensive or hurtful, doesn’t make it wrong. And just because we find something pleasant, fun or funny doesn’t mean it’s OK.

Add “yuck” and “yum” to your list of banned arguments – just because something makes you feel squeamish doesn’t make it bad. Listen to your emotions, but get curious about them – they need to be tested like everything else.

One final note: these tips won’t guarantee a kid won’t do the wrong thing sometimes – like all of us. But it will help you have a shared language for communicating, in a meaningful way, why what they did was wrong.

We all make judgements – it’s part of who we are – ethics helps us build the skills and character to ensure we’re making those judgements in ways that are alive to the world around us and the people within it. And like any skill, it’s easier to master if you start young.

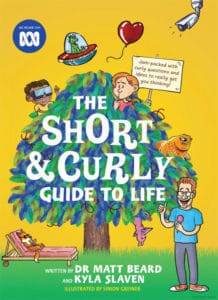

The Short & Curly Guide to Life

What makes something good or bad?

Why are things the way they are? How come it’s so hard to work out the right thing to do? The Short & Curly Guide to Life is an imaginative look at some of life’s biggest and trickiest questions. Figuring out what’s right is way more fun than you think!

Short & Curly Guide to Life is on sale at book stores around Australia and via major online retailers. You can also tune into the ABC Radio podcast, Short & Curly, here.

Matt Beard is the resident philosopher on the ABC Podcast Short & Curly, and the author of The Short & Curly Guide to Life (Penguin Random House). Find him on Twitter @matthewtbeard

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Academia’s wicked problem

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Donation? More like dump nation

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does ethical porn exist?

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

The moral life is more than carrots and sticks

The moral life is more than carrots and sticks

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Matthew Beard 16 NOV 2018

Almost everywhere I go to talk about ethics, I face some variation of the question: ‘Why be ethical?’ The question flummoxes and depresses me.

That’s partly because I can’t help but feel the question is basically ‘What’s in it for me?’ dressed up with a bit of academic, devil’s advocate flavour. But it’s also because to ask that question at all, you’ve got to have a pretty bleak sense of who people, at their core, really are.

But all the same, there are lots of people who have set out to answer precisely this question. Most of them are somehow connected to the world of institutions — government, business, non-profits and so on. You know, all the groups who studies suggest are haemorrhaging trust.

There’s nothing wrong with answering this question per se — in fact, it’s an interesting and challenging project that’s challenged philosophers since more or less the time the disciplined divorced from theology. But the answers are leaving me more-or-less equally disheartened as the questions themselves.

One common answer has to do with trust. And the thinking fits pretty well into the carrot/stick dialectic. The carrot approach goes a bit like this: data tells us ethical organisations are more trusted by other stakeholders, recruit and retain better staff and might even make more money.

The stick approach goes like this: unethical behaviour leads to a decline in trust, which leads to increased regulation, reporting and accountability. It stifles innovation, restricts opportunities and costs money.

The second answer is alluded to in the discussion of trust: regulation. The reason you should be ethical is because if you don’t we’ll catch you and hold you accountable for what you’ve done. People can’t be trusted to do the right thing, so we introduce safeguards to stop them from doing the wrong thing.

These two arguments boil down to self-interest on one hand and fear on the other. They respond to the part of humanity that is self-interested, petty and manipulative. That’s not necessarily a problem — failing to manage this aspect of humanity usually leaves the most vulnerable to suffer — but it’s an incomplete picture of who we are.

“The more we conflate ethics with trust, regulatory standards or “enlightened self-interest”, the less space we allow for morality to play a salvific role — not just to stop bad, but to make good.”

About 250 years ago, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote The Groundwork to the Metaphysics of Morals. Kant, in his brilliant but not-very-pithy way, argued that the only thing that has true moral worth is what he called ‘the good will’. The good will is the desire to do good for its own sake — regardless of the effects. Here’s Kant at his most poetic:

‘Even if by some particular disfavour of fate, or by the scanty endowment of a stepmotherly nature, this will should entirely lack the capacity to carry through its purpose; if despite its greatest striving it should still accomplish nothing, and only the good will were to remain … then, like a jewel, it would still shine by itself, as something that has full worth in itself.’

I worry that the way we talk about ethics today makes the formation of a good will, or some variation on it, impossible. This is because for regulatory and trust-based approaches to ethics, there’s always something outside morality that serves as motivation. It’s Santa Claus for grown-ups: we behave so we get presents instead of coal. And I’m not certain it works — I’m not inclined to trust someone who has ulterior motives for gaining my trust.

What’s more, it’s not clear how this approach to trust applies to groups who don’t need trust — think ‘too big to fail’ — and don’t have to fear regulation (perhaps they’re the ones who make the law). What reasons do they have for doing the right thing? And how might they define the right thing in a more morally sensitive way than pointing to their clean hands in the eyes of the law?

What is missing from this picture is anything that might generate a deep understanding — and love — of what’s good. The more we conflate ethics with trust, regulatory standards or “enlightened self-interest”, the less space we allow for morality to play a salvific role — not just to stop bad, but to make good.

I wholly understand the desire to minimise harm, prevent wrongdoing and serve justice. I also acknowledge the utility value in speaking the language of people’s desires — if people have been taught to think in terms of outcomes and self-interest, we may as well turn it to our advantage. But the more we do it, the more we entrench a mode of thinking that is at best narrow and at worst antithetical to the moral life itself.

It might still be that in the great moral trade-offs of life, protecting the vulnerable is more important that my high-minded philosophy. But we should at least know what we’re turning our back on — because in stopping people from doing bad, we might be preventing them from ever being good.

This article was originally written for Eureka St. Republished with permission.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Democracy is hidden in the data

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

When you hire a philosopher as your ethicist, you are getting a unicorn

When you hire a philosopher as your ethicist, you are getting a unicorn

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Matthew Beard 14 AUG 2018

If a tree falls on a philosopher in a forest and there is no one around to hear it, does she make a sound? Probably not, because she is undercover.

Philosophers are working in business and are applying their disciplined thinking processes to complex commercial and ethical problems – but you won’t find them listed on the organisational chart as philosopher-in-chief and seldom as the designated “ethicist”.

“We are unicorns, we are a bit rare”, says business ethicist and philosopher, Dr Petrina Coventry, who says she has spent her career being called something else.

“I’ve always hidden behind the HR brand because it is easier for people to cope with”, she explains. “If it takes pretending to be a pony to get the message across – so be it. We leave our horns at the door.”

Ethics officers bring a philosophical approach to thinking, decision making, strategy, branding, and communications. They work with all functions (marketing, legal, human resources, finance and others) to find the right way to do business.

“They are not compliance officers and they are not lawyers”, she says. They may carry business cards that announce them as chiefs of staff, people and performance or, occasionally chief operating officer.

Coventry says ethicists operating under other descriptors are trying to not “frighten the horses”.

“Going out and proud and saying you are a chief ethics offer will not get you very far”, says Coventry, a senior partner at Singapore based private equity company COI Capital and non-executive director of Beston Global Goods. She is also an industry professor and director of development at the University of Adelaide.

“People are frightened of the word [ethics]. They think you are making moral judgements about their character, that you are analysing them into ‘good’ or ‘bad’ based on their character, decision making or what they represent. And so, I try to avoid using the word ‘ethics’ if I can, because you can over use it and people just switch off.

“I don’t care what [title] I have to hide behind, whether it is ombuds or human resources. If it is not frightening, yet it helps them be a better person, be less stressed, be better thinkers … they are intrigued and they want more.” – Petrina Coventry

While being a company “ethicist” can be challenging to others, Philosophy has its own battle for acceptance in the corporate world.

Coventry, who has a doctorate in philosophy, says there is some suspicion in business circles that the discipline is esoteric, despite some of the world’s most successful executives and entrepreneurs having studied for philosophy degrees.

These people include activist investor Carl Icahn, hedge fund manager George Soros, former Time Warner CEO Gerald Levin, PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel, LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman, and Flickr cofounder and Slack CEO Stewart Butterfield. Not too flaky then.

Given the predominance of Silicon Valley CEOs on that list, it is perhaps unsurprising that technology companies are at the forefront of embracing ethicists (outside of the research, medical, and pharmaceutical sectors, which have a long history with ethics committees).

At this stage, most of the ethicists in tech have backgrounds in other areas, such as computer science (like former Google in-house design ethicist, Tristan Harris).

Coventry sees the beginning of a shift towards ethics, and away from compliance. She says:

“Compliance is cure, ethics is prevention.”

“It is a bit like having a doctor in-house rather than having to cart everybody off to the hospital because we forgot to go to the doctor.”

Outside of Silicon Valley, CEOs and their organisations are increasingly interested in acquiring more ethics expertise, especially now that scandals and failures now appear so frequent they may still shock, but no longer surprise.

“Stakeholder expectations have changed in the last ten years, partly due to increased transparency around corporate actions, but also due to the corresponding decline in trust regarding corporations and their leaders”, says Coventry, who has worked at executive level in “HR” at Santos, General Electric, and the Coca Cola Company.

Her first ethics role was in the 1990s, when she headed GE’s “ombuds” area in Asia, dealing with breaches in compliance and policy and workplace issues.

“The ombuds person is called on to mediate, negotiate, analyse problems that occur, and provide wise counsel and judgement, which is really what ethicists do”, she says.

In a world where the rules are constantly changing, situations are often unclear and legislation is unable to keep up with advances in science and technology, people have to make their own judgement calls about what is the right thing to do.

This has generated an interest in people who have an arts or philosophy background and can help develop better leaders and companies, she says.

“They are seeking a less emotional, less stressful, more thoughtful, more mindful, more sustainable approach, culture and leadership – and philosophy is born out of that.”

The Ethics Alliance brings different sectors of business together to discuss topics of importance.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Feeling rules: Emotional scripts in the workplace

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Moral injury is a new test for employers

Moral injury is a new test for employers

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 1 JAN 2018

When I am unsure if something is ethical, my favourite ‘ready reckoner’ is to apply the reflection test – I ask myself if I could look myself in the mirror after doing it.

Would my self-image be helped or hindered by the action? I could also call it ‘the slumber test’. Will I be able to sleep at night after doing what I’m setting out to do?

I’ve spent years studying the ethical and psychological toll that comes with doing things that stop us from meeting our own eyes in the mirror. There is a price that comes when we violate our most precious moral beliefs.

In military communities, this price is called a ‘moral injury’. Psychiatrist Jonathan Shay, the foundational voice on the subject, describes it poetically as “the soul wound inflicted by doing something that violates one’s own ethics, ideals, or attachments”.

This needs attention

As parochial as talk of souls might be, organisations should start paying attention to this risk for three reasons:

- So they can take steps to prevent their workers from being affected by moral injuries (basically, as an OH&S issue).

- So they know how to spot and manage moral injuries if they do occur.

- To figure out what support and remuneration they should offer if it turns out moral injuries are an ‘occupational hazard’.

The OH&S analogy is apt. Today, we expect organisations to think about their duty of care in a broad sense – taking an active interest in their employees’ wellbeing, seeking to reduce the risk of physical injuries, managing and minimising psychological stressors and mental illness, and providing fair training, support, and compensation when physical or mental stressors are likely to have a negative effect on employee wellbeing.

So, it follows that if some ethical issues can have an effect on wellbeing, they should be treated seriously by organisations claiming to care about their people.

How moral injury takes place

Moral injury is still a contested topic. Some people think it’s just a variation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), others think it’s no different from moral emotions like guilt, regret or remorse, and others still see it as something distinct.

Among veterans (who tend to dominate discussions of moral injury), the condition is seen as a condition akin to PTSD – a different kind of war trauma with different causes and different treatment pathways.

Whilst PTSD originates in feelings of fear and physical insecurity, moral injuries arise when we witness a betrayal or violation of our most deeply held beliefs about what’s right. It has to happen in a high stakes situation and the wrongdoing has to have been committed by someone in a position of ‘moral authority’ – a position you yourself might hold.

A group of US psychologists who have studied the issue offer a similar definition, describing moral injuries as “maladaptive beliefs about the self and the world” that emerge in response to the betrayal of what’s right. The injury is caused by the betrayal, but it’s in the beliefs and our response to them that it actually resides.

When we suffer a moral injury, our beliefs about ourselves, our world, or both are shattered in the wake of what we’ve witnessed or done.

Our moral beliefs are one of the ways we see the world and one of the ways we conceptualise ourselves. Everything flips when people no longer adhere to a ‘code’, good people are forced to do bad things for good reasons, or our different identities contradict one another.

This contradiction gives rise to ‘fragmentation’. Our moral beliefs, identities and actions no longer harmonise with one another. In the words of Les Miserables’ Inspector Javert, we find ourselves thrown into “a world that cannot hold”. Fragmentation demands reunification, and the way we go about this will determine both the extent of the moral injury and the likelihood of recovery.

How we respond to the conflict

If we can accept the critical event as being a rare product of extreme circumstances and a particular context, it’s possible to move on. We can accept guilt and seek forgiveness, admit our trust in a moral authority was betrayed and sever ties, or concede that the world is not as fair as we had thought.

This approach is relatively risk-free, albeit unpleasant.

However, if we are unable to see the event as context-dependent and, instead, see it as reflecting something universal – or worse, something about us – then a moral injury is likely to occur.

For example, if we have a handshake agreement to honour a business deal which is then betrayed, leading to widespread unemployment, we might decide that people are no longer trustworthy and either withdraw from them altogether or ‘get them before they get us’ next time. Either approach has an impact on a person’s ability to flourish in society.

Another possibility lies in concluding that we must be bad in order for us to have done what we did. Even if we were doing our duty without fault, guilt lingers and an employee could be permanently tainted by what they have done: “How can I say I am a good person when my actions resulted in this?”

Finally, we can recalibrate our moral beliefs. Perhaps, as many veterans argue, we were wrong to think the world was predictable or reliable to begin with. Maybe our moral injury isn’t an injury at all. Perhaps it’s a sign we’ve learned something new.

What employers can do

Moral injuries must be addressed because they affect a person’s future ethical decision making and their capacity for happiness.

This gives organisations another reason to have a robust ethical culture that guards against wrongdoing and refuses to ask people to act against their conscience.

However, this won’t always be possible. Sometimes professional demands require people to ‘get their hands dirty’, witness wrongdoing or even participate in something they feel contradicts their moral beliefs.

A committed parent may be required to decline an insurance claim, leaving the claimants – a family– homeless. How will he go home and sit with his children knowing his actions have put another family in jeopardy? A nurse may be legally prohibited from helping someone to end their life. Can she be a good person while allowing someone to needlessly suffer?

The question of moral injury has typically been posed as an individual problem but, if the OH&S analogy is a valid one, we should think about the responsibilities of organisations in the wake of what we’re learning.

An organisation violates its duty of care if it exposes workers to risk without reason, consent, support or fair compensation. Perhaps we might say the same for moral injuries, with one important caveat: it would be perverse and potentially corruptive to offer financial incentives for people to compromise their values and moral beliefs, offering a salary increase to be exposed to ethical risks, for instance.

A clear ethical purpose with which staff can identify and that is consistent with their moral beliefs is a more appropriate incentive. Not only might this prevent wrongdoing in the first instance, it can help reunify a fragmented identity if a moral injury does occur.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Are diversity and inclusion the bedrock of a sound culture?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

If it’s not illegal, should you stop it?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership