What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Joseph Earp 21 NOV 2024

On February 16, 2009, local police in Stamford, Connecticut received a highly unusual, and deeply horrifying 911 call – Sandra Herold, her voice hysterical, told them that her pet chimp, Travis, had attacked and was eating her friend. In the background of the call, along with the screams of the friend, police could hear the hollering of an enraged primate.

Sandra had purchased Travis over a decade prior. Their relationship was extremely, perhaps unnaturally close – she raised him as a human child, and after her own daughter died, Travis became her everything. Travis, who showed high levels of intelligence, ate with her at the dinner table. Each night, they slept side by side in the same bed.

There has been much speculation as to what flipped Travis into a rage. Sandra’s friend, the victim of his attack, was holding his favourite toy when he mauled her – an Elmo doll. Perhaps it was an instance of territorial aggression. Perhaps it was his unhealthy lifestyle, or the drugs that Sandra sometimes gave him; she had mixed Xanax into his tea, just before the attack. Regardless, the attack raises questions about the ethics of owning exotic pets – and what exactly makes them different to domesticated animals.

Animal ownership: Rights and wrongs

We live in a culture increasingly fascinated by the ethics of owning exotic pets. The pandemic-era Netflix smash hit Tiger King and the recent series Chimp Crazy take an outrageous look at the often eccentric people who choose to own lions, tigers, and primates. More often than not, these investigations into exotic pet ownership show the dark side of the industry – Joe Exotic of Tiger King fame was repeatedly accused of abusing his animals.

Private owners of exotic animals frequently commit clear ethical wrongs. “Many private owners try to change the nature of the animals by … mutilating them, or beating/electrocuting them into submission,” writes animal welfare expert Bobbi Brink. There is a fundamental attitude towards the animal that underpins these harms. Namely, the animal is being treated and defined wholly by its relationship to human beings, and what they can do for us. It becomes an object that owners can do what they wish with. Ownership of this type transforms a living being into what philosopher Immanuel Kant described as a “means” rather than an “end” – it is indistinguishable from property.

This is, in fact, the argument made by philosopher Gary L. Francione against all forms of pet ownership. Francione argues that there is no way to not see your pet dog as anything other than property – you control it, own it, reduce to it to a mere object. “As a practical matter, there is simply no way to have an institution of ‘pet’ ownership that is consistent with a sound theory of animal rights,” Francione writes. “‘Pets’ are property and, as such, their valuation will ultimately be a matter of what their ‘owners’ decide.” Elsewhere, writer Karen Dawn notes that solitary confinement is used to punish humans – according to her, for pack animals like dogs, life without others of their kind can arguably be considered solitary confinement.

However, there is a mutually beneficial nature to some forms of pet ownership. There is much to suggest that human evolution was shaped and moulded by our relationship with dogs – there is a mutual appreciation that goes both ways. We give them things, and they give us things back. This in turn builds an emotional connection that can give both humans and pets lives worth living. At least, some forms of pets.

The allure of power

The ownership of exotic animals is troubling because of the lopsided power dynamics at play. The mutual beneficence in the case of dogs simply does not apply when it comes to lions or chimps. They do not gain anything from being taken from their homes, locked away, and having their needs systematically and brutally unmet. Travis the chimp might have eventually committed an act of brutality – but his life before that point was filled with what philosopher Michel Foucault would describe as diffused, rather than acute, forms of brutality. It was the brutality of being separated from his species and his needs.

The question remains, then – why do people want to own exotic animals? What is the appeal? And what does that say about human nature?

Exotic animals represent the unknown; the other; the distinct. The drive of taking the other, “dominating” it and making it our own, is what philosopher Nietzsche called “the will to power.” According to Nietzsche, the dynamics of those who take, and those who are taken from, exist in all things – it makes sense they would also exist in our relationships with exotic pets.

There is some sense of perceived glory in taking a wild creature and bending it to your will, and often, unable to cater to their complicated needs, owners tend to restrict or harm exotic animals in some way.

This kind of domination is about the success of one way of living; proving the excellence of the recognisable, by making the unrecognisable more like it.

One of our most admirable traits as a species is our curiosity. Being interested in exotic animals, and in pets, speaks to that curiosity. We are drawn to what makes them tick. That in itself is not a problem. But we must ensure that our relationship is one defined by that curiosity; to that openness to a creature, and all that it wants and needs. In short – we don’t need to change the nature of the other, or what is different to us. We need to respect it.

Image: Tiger King, Netflix

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Women must uphold the right to defy their doctor’s orders

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

The ethics of friendships: Are our values reflected in the people we spend time with?

The ethics of friendships: Are our values reflected in the people we spend time with?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Anna Goodman 14 NOV 2024

Some psychologists believe that we become the average of the people we spend the most time with. However, this can make things complicated for our own morals, ethics, and values.

In the middle of 2020, Nobel Peace Prize recipient Malala Yousafzai was harassed on Twitter for endorsing her conservative friend at Oxford University. It made headlines around the world, with thousands of people commenting on who they felt they could and couldn’t be friends with out of principle.

While friendships often transcend differences of opinion, most people have limits on what values and beliefs they will tolerate in the people they spend time with. It’s important to ask ourselves: does being friends with someone mean agreeing with all their values and beliefs? Or can we be friends with someone we disagree with?

There is more to friendship than simply sharing values and beliefs

When we enter into a friendship, we are agreeing to a set of duties and expectations of what it means to be a good friend. These duties can involve providing support during difficult times, celebrating accomplishments, being caring and empathetic, and so on.

However, it’s unlikely we’ll have friends who we agree with 100% of the time. This could mean disagreeing with a choice they made, or realising that you have differing values about something. It is perfectly reasonable to disagree with a friend or hold an opposing view, and not be hypocritical in your own beliefs.

It’s important to interrogate, though, what this means for us. When Malala was harassed online for having a friend with different political views, it wasn’t because she herself expressed those views. Rather, it was because she supported a friend with different views, and that support supposedly had to have indicated something about her own values and beliefs.

Friendships, however, are so much more than shared values. Having people in our lives with different values and opinions can broaden our perspective on the world, while also providing us with the opportunity to question the reasoning behind our own beliefs.

Even though there is more to a person than both their views and the views of their friends, it is naïve to claim that our friends’ values don’t have an impact on us.

So, there has to be a threshold of tolerance in what we are willing to understand in our friends’ values. The ethical dilemma we find ourselves in is where we draw the line.

There is no doubt that some categories of opinions and values shouldn’t be given the same airtime as others. One way we can discern this is by asking: what are the implications on others in expressing or acting on this belief?

Some beliefs predominantly impact the individual who holds them. Food preferences, opinions about what clothes look good, or what music sounds best are unlikely to have a significant effect on the people in this person’s life.

However, expressing or acting on other kinds of beliefs can have obvious, negative impacts on certain groups of people such as racist, sexist or homophobic rhetoric, disinformation, and hate speech. Understanding that expressing some kinds of beliefs has an impact on the broader community characterises the harm of unchecked intolerance.

When we overlook a friend’s more severe hateful or discriminatory belief, we can become complicit in allowing a belief that harms others to go unchecked.

Overlooking a hateful or discriminatory belief the same way that we might overlook a difference in taste or preference makes it seem like we are condoning, if not supporting, that belief. For example, if your friend was continuously espousing hate speech and you didn’t call them out on it, it doesn’t matter if you didn’t partake in hate speech yourself. By letting it slide because it’s a friend, the harm of expressing these values is still being done. Challenging and speaking out about that belief doesn’t mean that we are being a bad friend – in fact, it usually means the opposite.

One possible solution: deal breakers

Even though we can’t expect to have all the same values as our friends, we might expect that we have the same deal breakers as them. A deal breaker is something like a value or personality trait that will cause a person to back out of a relationship or agreement. For example, one of the things that might connect us to our friends is that we all have a deal breaker that we won’t tolerate someone who is rude or unkind to strangers. Having the same deal breakers means that we draw the same line in the sand of what we will and won’t tolerate, rather than ensuring that we agree on every single value.

The concept of a deal breaker can be helpful with ethical value differences in our friends, too. For example, it could be that we’re happy with different approaches to ethical decision making, as long as we both won’t tolerate anything that harms others unnecessarily. Instead of making sure we agree with our friends entirely, we’re making sure we’re on the same page about the “non-negotiable” values we have.

As with most ethical issues, the answer is rarely black and white. In this case, the line we draw with what values we tolerate in our friends can often fluctuate due to external factors, including mental health and personal context.

At the end of the day, being someone’s friend shouldn’t mean that you have to defend every single belief that they have. I would hope that my friends feel that they can challenge my beliefs, and that I can do the same for them. However, it is important that we think about the deal breakers we have and hold our friends accountable for how their beliefs impact the broader population, and be willing to look inward when they do the same for us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

So your boss installed CCTV cameras

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

“Animal rights should trump human interests” – what’s the debate?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Trump and the failure of the Grand Bargain

Trump and the failure of the Grand Bargain

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

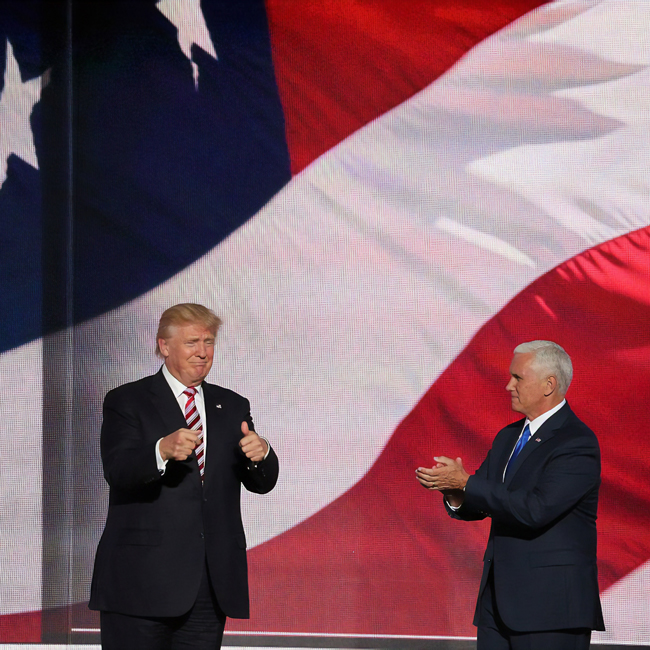

BY Tim Dean 11 NOV 2024

Work hard, play by the rules and you will have a successful and good life. Or so we’re told. Trump’s recent Presidential victory says a lot about how democracy has failed us.

It’s been a few days since it was announced that Donald Trump would be returning to the Oval Office after winning a decisive victory against Vice President Kamala Harris, and it already feels like 2016 again. Like then, many people are straining to make sense of how a man they deem to be morally bankrupt could have secured the votes of over 72 million Americans.

There will likely be pools of ink spilt attempting to explain the political and economic factors that returned Trump to the White House. But I want to view this moment through a broader moral lens. Because, while Trump’s first victory in 2016 might have been interpreted as a freak event, where a political outsider disrupted an otherwise healthy and functional democratic society, his second decisive victory suggests there’s something deeper and more pervasive at work – a failure that persists at the core of democratic society that Trump was able to exploit.

The Grand Bargain

Go to school, behave yourself, study hard, get a job (any job), work hard, pay your taxes and play by the rules. If you do all this, then society will ensure that you will be a success and enjoy a good life.

That’s what I call the ‘Grand Bargain’ of modern liberal democratic society. It goes by different names, with a different spin, in every democracy through terms like the “American Dream” or the “Great Australian Dream”. But it goes beyond just the idea that opportunity is open to all or that home ownership is a natural step towards financial security. It’s like an implicit agreement between the state and the individual: play by the rules and everything will be OK.

However, many people in ‘rich’ countries are not OK. I barely need to mention inflation, the rising cost of living, stagnant wages, unaffordable housing, exorbitant rent, the offshoring of jobs, the rise of insecure gig work, the closure of traditional industries and manufacturing, not to mention the fact that corporate profits are skyrocketing and the top 10% are doing better than ever. The Grand Bargain has been under pressure since the 1990s and, arguably, it’s been broken ever since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009.

And people are angry. This is not just because the failure of the Grand Bargain has resulted in real material disadvantage, but the anger has a moral dimension due to a deep sense of injustice at the failure of the state – especially politically and economically – to live up to its end of the Bargain.

Injustice breeds outrage, and outrage is a moral emotion that creates a desire to punish the perceived wrongdoer. In this case, the perceived wrongdoers are the political ‘elites’ who have been instrumental in promoting economic growth at the expense of the workers within that economy. In most modern liberal democracies, those elites include members of both the Left and the Right, especially since the neoliberal turn of the 1990s. So, over the last two decades, no matter who people vote for, the Grand Bargain has remained broken.

It doesn’t matter that Trump is part of this elite political class. It doesn’t matter that his policies are little more than a basket of fantasies that will almost certainly worsen the economic circumstances of most of those who voted for him while enriching the super rich even more.

What matters is that Trump has effectively given voice to those who feel that the Grand Bargain has failed, and that it’s politics-as-usual that has let them down.

And what Kamala Harris represented – as did Hillary Clinton before her – was politics-as-usual: a kind of politics that tinkered around the edges by providing small perks to certain groups to offset the huge systemic disadvantages they faced. Meanwhile, they were afraid to enact systemic change because that would require facing off against the powerful vested interests who continue to benefit from the current economic paradigm.

Identity crisis

But this is not the full picture. The Grand Bargain isn’t just about economics, it’s also about identity. In order to live a good life, we need more than just material prosperity, we also need to have our identity recognised and to experience a sense of pride.

Whether justified or not, large segments of the population in many liberal democracies have felt that their identity has been under attack. Neoliberal policies have taken away the work that gave them a source of meaning and pride in their lives. Multiculturalism has fragmented their communities, eroding social capital and leaving them feeling unmoored in their own neighbourhoods.

The recent historical reckoning over colonialism and racism has contributed to a narrative of shame directed at the beneficiaries of systemic discrimination, particularly white people. Similarly, the historical reckoning over sexism has promoted a narrative that many men feel has disempowered them and challenged a core feature of their identity.

I hasten to add that there is much that modern liberal societies must reckon with. But what’s of importance here is how that reckoning has been perceived by many people, especially at a time when their material circumstances have been increasingly precarious.

Meanwhile, the ‘elites’ – particularly on the progressive side of politics – led these attacks on identity, policing speech and behaviour, and perpetuating a narrative that expressions of pride in one’s heritage or culture, or any expression of concern about diversity, inclusion or the welfare of men was to be perceived as a form of bigotry. As a result, many people changed the way they spoke and behaved in public, but they didn’t change the way they thought.

Then along comes Trump. He didn’t change the way he spoke or behaved. He said what many people were thinking. He validated the identities of many people who felt under-recognised. He offered a counter-narrative of pride rather than shame.

Be bold

When you look at Trump’s victory through the moral lens of outrage directed at the failure of the Grand Bargain and at the narratives that cause people to feel shame, then it makes a lot more sense.

Trump was uniquely positioned to exploit this outrage, to give voice to the indignance that many Americans feel in being ‘left behind,’ and to offer a narrative of ‘greatness’ that promised to restore their pride.

It doesn’t matter whether his solutions are the right ones to fix the grievances he’s tapping into. What matters is that he validated public outrage at the failure of the Grand Bargain, and he presents himself as strong enough to do something about it even in the face of powerful vested interests (even if he, and his friends, are those vested interests).

Those who are concerned about the implications of a second Trump presidency, or who lament the rise of populism in democracies around the world, would do well to shift their attention from blaming voters and direct it towards restoring the Grand Bargain. That is not an easy thing to do. It will likely require facing off against powerful vested interests. But through this moment might come avenues to rectify the deeper failures of modern democratic societies and prevent the rise of populists who recognise those failures but whose solutions only make the problems worse, not better.

If there’s one lesson that Trump has for all politicians, it’s that if boldness and fearlessness coupled with a commitment to promote the interests of one’s supporters can overcome the many political drags that Trump brought to his campaign, imagine what it could to for someone of principle.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A note on Anti-Semitism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

We are witnessing just how fragile liberal democracy is – it’s up to us to strengthen its foundations

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Monty Badami 1 NOV 2024

Jill Stark, recently wrote a controversial piece likening athlete Nedd Brockmann’s 1600km charity run to a broader trend of men “repackaging mental health as mental toughness”, where the “blokeification of mental fitness” is “just toxic masculinity rebranded”.

She has since apologised for the headline, acknowledging that it “was reductive and clumsy and failed to capture the complexity of the issue”. But she also received a lot of vitriolic abuse that proved the very things she was trying to call out.

Whilst it’s not new for men to engage in extreme acts to prove themselves, there has been an increase in shirtless men on social media, with rock-hard abs and beards, embarking on extreme ritualistic adventures to reclaim their manhood. Men are going to brutal boot camps to develop their physical wellbeing, mental toughness, and “find their tribe” through a spartan lifestyle, a navy seal mindset and howling at the moon. Beating drums, near-naked wrestling, the rejection of alcohol, drugs, technology, women and other worldly distractions are the homo-social privations in this cult of masculinity, where Jordan Peterson is regularly quoted, and Andrew Tate is tolerated, if not revered.

Whilst I won’t tar Nedd Brockman with the same brush, there’s something about how he’s been received that could be used as a gateway to the manosphere.

The “no pain no gain” movement in men’s mental health, and the performative tribalism that goes along with it, has worrying similarities to the humiliating initiation rituals of university colleges, the military and cults. But it’s not the first time men have desired the return to an idealised “natural”, “tough” and masculine past.

Paradoxically, the term “toxic masculinity” emerged from the mytho-poetic men’s movement of the 80s and 90s. It was an explicit response, by men, to feelings of powerlessness at a time when the feminist movement was challenging traditional male authority. It was an attempt to navigate the social pressures placed upon men to be violent, competitive, independent, and unfeeling.

But toxic masculinity doesn’t simply condemn all men or male attributes. It refers to the rigid and excessive policing of masculine norms, such as dominance, self-reliance, and competition, that are harmful to men, women, and society overall. And this is how the performance of alpha-male, lone-wolf, toughness can be toxic. But we must consider the intent.

Is the focus on toughness an act of self-interest to stroke the ego? Is it necessarily tied to masculinity, and used to dominate other men? Or is it a mechanism for self-understanding, self-growth and service to the community?

How is Brockman’s achievement different to Jessica Watson sailing around the world? Or Grace Tame competing in ultra marathons and processing her trauma? Or Darius Sam, from the Lower Nicola First Nation in Canada, who ran 100 miles to raise awareness around addiction and mental illness, and to grapple with how these issues affected his life?

As an officer in the Australian Army, my training challenged me mentally, physically and emotionally to develop resilience and moral courage. But this was not about glory. My ego actually got in the way when I faced those dark places within. Sitting with my emotions and transcending my ego became a source of profound growth and self-understanding. For Stoics like Aurelius and Epictetus, they taught that resilience comes from within, based on inner values rather than external displays of strength.

When we look cross-culturally, extreme rituals are not only about the promotion of self, or masculinity. Ritual theatre and performance is also a way to create intense social bonds and transcend the self, with adaptive and evolutionary benefits. We can even see this in the strong feelings of community experienced by both men and women who do ultramarathons or cross-fit.

But what troubles me in this discussion is the assumption that external challenges are inherently masculine and performative, and internal ones are somehow feminine and more authentic. It’s a false binary that ignores the fact that this is beyond gender. It ignores how external challenges facilitate the journey within.

But, why do we necessarily associate anger, aggression and competition with masculinity? Why do we associate empathy, nurturing and care with femininity?

I’m not competitive or aggressive. In our home I’m seen as more empathetic. My wife is the opposite. She’s more decisive, and doesn’t like talking about her feelings. Does this make her less of a woman and me less of a man? Of course not. What’s more, we both possess all the qualities listed above, just in different measures.

Essentialist concepts of masculinity ignore the fact that there are many ways to be a man. Whether you define masculinity in “traditional” or “alternative” terms, you are still constraining it, and that can make it toxic.

And so, we need to interrogate the very definition of masculinity itself, so we can safely explore our sex and gender, and find healthy versions of what it means to be human in all its brilliant complexity.

We’re all at different stages of personal growth, so perhaps the answer is not simply “news-jacking” Nedd Brockman, stopping ultra-marathons or ice-baths, and lumping them in the same bucket as toxic “raw-dogging” masculinity. Perhaps the answer is the very thing we want those alpha-males to embody? Perhaps the answer is empathy and compassion?

Rather than pushing these men away, Mike Dyson, founder of The Good Blokes Co, an organisation that runs Healthy Masculinity Retreats, says:

“A lot of men think the conversation about masculinity is negative and dominated by women, so they are disengaging. Nothing is going to change if men are not having this conversation too.”

“We’re seeing a desire of men to explore toughness and resilience – and that’s because our culture of masculinity rewards the performances of toughness. So, we need to meet blokes where they are in order to take them to where they need to go.”

“Rigid masculinity is the thing that gets in the way of true resilience because it stops us talking about our emotions, so we have an opportunity and a responsibility to have a deeper conversation about this with the men in our communities”.

And perhaps that is precisely what Stark and Brockman are allowing us to do right now. We can actually draw men in with the language of mental toughness, and then open the conversation to include other things like service, humility, intimacy, emotional maturity, accountability, calling out your mates, and stopping gender-based violence. And this can be a really important thing to give young men as they navigate the internal and external challenges of what it means to be a man in the world today.

Further resources

Mental Health

Head to Health: https://www.headtohealth.gov.au/

Open Arms: https://www.openarms.gov.au/

Relationships Australia: https://relationships.org.au/

Talk2MeBro: https://www.talk2mebro.org.au/

Community Groups

The Man Walk: https://themanwalk.com.au/

Dads Group: https://www.dadsgroup.org/

Tough Guy Book Club: https://toughguybookclub.com/

Mens Shed: https://mensshed.org/

The Men’s Table: https://themenstable.org/

Immediate Support

Beyond Blue: https://www.beyondblue.org.au/

Men’s Line: https://mensline.org.au/

Lifeline: https://www.lifeline.org.au/

Studies and interactive resources

Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World: https://www.vivekmurthy.com/together-book

The Man Box Study: https://jss.org.au/programs/tmp-research/the-man-box/

The Good Blokes Co: https://www.goodblokes.co/

Healthy Male website: https://www.healthymale.org.au/mens-health-week-2023

For more, tune into the FODI24 panel discussion, Positive Masculinity:

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

5 ethical life hacks

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

True crime media: An ethical dilemma

BY Monty Badami

Dr Monty Badami is an Anthropologist and the Founder of Habitus, a social enterprise that gives you Lifehacks to be a Good Human! Monty combines evolutionary evidence with cross-cultural research to explain the secret to our adaptability and success as a species. He designs and delivers workshops that help people put more meaning and joy back into their lives.

Ask an ethicist: How to approach differing work ethics between generations?

Ask an ethicist: How to approach differing work ethics between generations?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker 25 OCT 2024

I place a great deal of importance on the work I do, I enjoy my time in the office, and spending time with my team. However, lately I have noticed a younger colleague of mine is slacking off. They frequently take sick leave, or call in to work from home, and it often feels like there’s no urgency to their tasks. I am starting to feel a growing sense of resentment, as this hardly feels fair to me or my colleagues. Is there a way I can approach what I consider to be a poor work ethic?

It’s natural to feel a sense of unfairness and frustration when you’re putting in the effort and others don’t seem to be keeping pace. After all, work is called work for a reason – it’s not meant to be effortless.

Addressing the fairness of workload and the impact it has on the workforce is being explored more and more as automation is being used to assist with tasks and we find ourselves for the first time working alongside five different generations.

As our behaviours are driven by our values and it’s worth considering how different generations bring different values and attitudes to the workplace. Research into generational attitudes toward work provides some useful insights:

The Silent Generation (1928-1945) value loyalty, job stability, long-term careers and staying with one company for decades.

Baby Boomers (1946-1964) value hard work, dedication, responsibility, job security and stability.

Generation X (1965-1980) value independence, self-sufficiency and personal responsibility.

Millennials (1981-1996) are the largest cohort working in business today. They seek purpose in their work, value personal development, and look for roles that allow for work-life integration.

Generation Z (1996-2010) value flexibility, work life balance, diversity, inclusion and well-being.

So, what does this mean for your situation? While each generation may have a distinct approach to work, shared values like fairness, accountability, and empathy can create not only common ground but also opportunities. Most employees, regardless of age, want to know that workloads are distributed equitably, and that everyone is contributing their part. When this balance seems off, frustration is understandable.

However, it’s worth considering that your colleague’s behaviour may stem from reasons beyond their control. They may be facing personal challenges or health concerns, and it’s helpful to understand that we’re often dealing with factors that aren’t always immediately obvious on the surface.

Accountability is another value shared across generations. Regardless of how we work – whether in the office or remotely – there’s an expectation that we should be held accountable for our work and deadlines.

It’s possible that your younger colleague isn’t fully aware of the expectations and may benefit from clearer communication, so they better understand the priority of their work. This could help address the perception that they lack motivation or urgency.

Focusing on outcomes rather than physical presence can bridge generational differences and shift the conversation towards ensuring the work gets done effectively, no matter where it’s completed.

At the same time, empathy and understanding are important, especially when considering values related to well-being. If your younger colleague is frequently working from home or taking sick days, it may be their way of managing their health in a more proactive manner than what might have been typical in earlier generations. This could be an opportunity to reassess your own attitudes to work and question how helpful it is to be working when you’re not feeling 100% or trialing different approaches to prevent burn-out.

Rather than letting frustration build, consider having an open and supportive conversation. This could open a dialogue that leads to a better understanding of how to ensure both their well-being and their work responsibilities are met.

Ultimately, acknowledging and recognising the different generational values can open up new ways of working together. Conversations can explore the impact of those differences and find solutions to any tensions. Addressing these issues through a balance of our shared human values such as fairness, accountability, and empathy can create a more harmonious work environment for everyone.

As Bob Dylan famously said, “The times they are a-changin’” and if you’re asking, “who’s Bob Dylan?”, check him out, I think you’ll love him.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The dangers of being overworked and stressed out

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

We are on the cusp of a brilliant future, only if we choose to embrace it

Explainer

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Ethical Infrastructure

Reports

Business + Leadership

A Guide to Purpose, Values, Principles

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

Is it fair to expect Australian banks to reimburse us if we’ve been scammed?

Is it fair to expect Australian banks to reimburse us if we’ve been scammed?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Nina Hendy 18 OCT 2024

I recently interviewed an 88-year-old woman who had been scammed out of $49,000. She acted quickly, and presumed the bank would be able to recoup her money.

In her case, she downloaded a third-party app, before logging into her bank account as instructed. She shared the security code with the scammer, enabling them to authorise the transaction before quickly realising she had been duped, hanging up the phone.

She had the account number where the money had been transferred to and an investigation was launched, but despite being a customer at her bank for 60 years, the bank said there was nothing they could do to get her money back.

How scammers operate

Scams are growing increasingly complex and sophisticated. Sometimes pretending to be from your bank, scammers might target you online or social media, or by phone, text or email. If they’re clever, they might give you some information that seems genuine to try and gain your trust, or may suggest there’s a problem to fix, such as a problem with your computer, an overpayment or suspicious activity on your account.

Collectively, Australians lost $2.7 billion to scams in 2023, with online dating and romance, investment, products and services, threat and extortion, employment, and impersonation scams among the most common. Victims are encouraged to report their scam to the National Anti-Scam Centre, but Scamwatch says people often feel ashamed, resulting in around 30 per cent of victims never reporting it.

There has been strong resistance from the banking sector to compensate scam victims. And while Financial Services Minister Stephen Jones has vowed to crack down on organisations that enable scams and don’t pay up, indicating a keenness to ‘redesign fraud out of the system’, banks reimbursing scam victims doesn’t appear to be on the government’s radar.

While the banks put the onus on their customers to ‘hear the alarm bells’, Labor wants scam victims to be compensated under a plan to fine banks and social media platforms $50 million and be forced to pay compensation if they fail to protect customers from scams.

The banks argue against reimbursing scam victims, saying it would create a honeypot effect that would entice criminals to target Australians more often. The other argument is that reimbursing funds lost in scams would make the crime ‘victimless’, making consumers even more attractive to money-hungry scammers.

Currently, if a customer in Australia transfers funds to the wrong account, the bank that sent the money is responsible for dealing with the complaint, rather than the bank that received the funds. The banks are also not obligated to repay scam victims.

Banks educate, not reimburse

Instead, banks have embarked on an education campaign reminding customers to remain vigilant to the threat of scammers, while the recently announced Scam-Safe Accord includes a $100 million investment by banks in a new confirmation of payee system to ensure people can confirm they are transferring funds to the person they intend to.

It’s a far cry from the UK, where most banks already voluntarily compensate customers who are tricked into sending money to scammers, but in a world first, authorities recently mandated that banks must refund fraud victims up to $EU85,000 within five days, unless they are at fault.

As of this month, a new shared liability proposal by the Payment Systems Regulator is expected to impact financial institutions around the world. The system makes both sides responsible for the reimbursement, which is hoped will encourage collaboration between all players to detect and prevent scams.

It’s a policy welcomed by CHOICE and the Consumer Action Law Centre, which wants the government to go a step further and establish a reimbursement model similar to that used in the UK. They work with victims, who often don’t ever emotionally recover from the ordeal.

Who is the onus on?

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) has been clear that banks aren’t doing enough to protect vulnerable customers. Despite this, the banks rely on a tenuous moral argument that suggests that customers will be less attentive and take greater risks if they think they are in line for compensation.

Perhaps Australian banks can take a leaf out of UK’s TSB Bank, which started reimbursing almost all customers who fell victim to scams about four years ago. The bank says the results were stunning, actually resulting in a reduction in fraud.

TSB says voluntarily reimbursing scam victims resulted in its share of losses sitting well below what it would expect for a bank of its size.

Examples of these gestures of goodwill can foster loyalty and trust between banks and their customers, beyond strict legal or educational obligations. While victims can face significant distress, offering reimbursement is an ethical way for banks to support their customers, helping both restore their financial and emotional well-being.

While there is an asymmetry of resources and knowledge when it comes to keeping our money safe, a shared responsibility acknowledges the ethical duty to continually improve safeguards when it comes to scams.

After all, it’s compassionate business practice and a shared burden that strengthens corporate character.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Explainer

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Social license to operate

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pavan Sukhdev on markets of the future

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

BY Nina Hendy

Nina Hendy is an Australian business & finance journalist writing for The Financial Review, The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and The New Daily.

How to have a difficult conversation about war

How to have a difficult conversation about war

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsPolitics + Human Rights

BY Tim Dean 4 OCT 2024

Many people feel they need to talk about the conflict unfolding in the Middle East, but others find that conversation distressing. Here’s how to have a conversation about ongoing conflicts in a safe way for everybody.

This year – and possibly for many years to come – October 7th is going to be a difficult day to endure for many people, not least those with a connection to Israel, Palestine, Lebanon and other countries in the Middle East. Even for those without a connection to those lands, the news of the conflict there is hard to avoid. Headlines are filled with tragedy, streets a filled with protestors, and walls are covered in posters howling in outrage or crying for justice for one side or the other.

In this environment, it’s not surprising that many people feel compelled to share their thoughts and feelings about the conflict. And it’s equally unsurprising that many others find it too distressing a topic to engage with, whether it’s because they are affected themselves or because they feel powerless to avert the unfolding tragedy.

People should also be forgiven for not engaging in an emotionally charged and potentially distressing conversation. While we should all have some awareness of major happenings around the world, we are not obligated to engage with those that don’t impact us or our community and are beyond our control.

However, a problem occurs when people of opposite dispositions meet, and some desperately want to talk about the conflict and others desperately want to avoid just such a conversation.

So, here are some approaches you can use if someone starts a conversation about the conflict, especially if that’s a conversation you’re not totally comfortable diving into.

Pause

Often, when we hear something that triggers a strong emotional reaction, especially if it’s a view we might disagree with, we react as we would to a physical threat: fight, flight or freeze.

Some reactively fight, and immediately push back with an alternative perspective. But if we start a conversation from a position of opposition, it shifts the dynamics into one of conflict rather than cooperation. That isn’t a problem if everyone has tacitly agreed to enter debate mode, but often that’s not the case, and conflict can easily trigger defensive reactions that cause the conversation to spiral into an unproductive clash, only heightening everyone’s emotions.

Others attempt to flee from the conversation, such as by changing the subject or even physically leaving the room. However, if the person raising the issue feels compelled to do so, they may remain unsatisfied and will just raise the issue again at another point. Freezing, on the other hand, may be perceived as tacit agreement to dive into the conversation, which might end up being harmful or distressing for those involved.

So, the first step for managing difficult conversations is to pause whenever you hit a point of contention or at the first indication of raised emotion, either in yourself or those you’re talking to. This gives you an opportunity to recognise and acknowledge your immediate reaction and quickly take stock of who else is in the conversation and what they might be feeling. And if we believe that someone in the conversation might be in genuine distress – including ourselves – then we can work to steer the conversation in a different direction.

Cast the net wider

One approach for steering a conversation away from potentially distressing content is to not engage with the content directly, but instead go “meta” and talk about what you’re talking about.

So, instead of sharing opinions or judgements about the conflict in the Middle East, ask questions about the conversation itself: why are people so invested in the conflict – especially if many of them don’t have a personal connection to those affected? How are people talking about it? Are the conversations going on around the country and in the media helping or are they divisive? How are these conversations affecting people, especially those who are connected to the conflict? How should we be talking about it?

Asking meta questions like these can shift the conversation away from the details and on to the human impact that the conversation is having. It can prompt everyone to reflect on their role – and responsibilities – when talking about potentially distressing subjects and cultivate empathy with those affected.

Going meta can also allow you to offer a more explicit invitation to take the conversation to another stage, giving everyone an opportunity to opt-in or opt-out. The meta conversation may have already helped to set some ground rules for how a conversation about the conflict might unfold, including what kind of language is appropriate and what kinds of topics are off limits out of respect for those affected.

Explore feelings

If you progress the conversation further – or if others feel compelled to do so – it doesn’t mean you need to dive straight into sharing your opinions on the conflict itself. Instead, there is another framing that can be equally, if not more constructive. This is the “expressive” frame.

Rather than asking people what they believe, invite them to share how the conflict makes them feel. This focuses the conversation on emotions and experience rather than opinions or judgements. There’s a subtle but important difference between the two.

We all have opinions and judgements about issues that are important to us, and are more than ready to offer reasons to support our attitudes. But as the American psychologist Jonathan Haidt has pointed out, many of these opinions and judgements ultimately stem from our emotional reactions.

When we experience outrage, for example, we immediately form a negative judgement of the perceived cause, and we often fish for reasons to support that judgement. This means that many of our reasons are post-hoc rationalisations of our emotional responses. If you start discussing these post-hoc rationalisations, you’re not really engaging with the root causes of how someone feels about an issue. Instead, it’s often far more fruitful to unpack the way they perceive the issue in the first place and discuss how that makes them feel.

Engaging in the expressive frame has another benefit: often people who have strong feelings about an issue have a deep need to have those feeling heard and validated by others. By asking how they feel and just listening to them and validating those feelings – without necessarily agreeing with their opinions – can satisfy them and might even prompt them to listen to how you feel about it.

Conversational scripts

Both the meta and expressive conversational modes are ways of engaging with difficult issues without tackling the substantive – and potentially harmful or distressing – content head on. They give you a chance at having a meaningful conversation that can be more sensitive and help protect those who might feel threatened or unsafe.

That said, it can be difficult in the heat of the moment to know what to say to shift the conversation to the meta or expressive frame. For this reason, it can be useful to have a few conversational scripts up your sleeve that you can whip out as needed.

If someone expresses outrage about some aspect of the conflict, the protests or political response, and you want to shift to the expressive frame, you could say: “I’ve been hearing about that everywhere. How do you feel when you hear about it?”

Or if you want to move away from commentary about distant news and ground it, perhaps ask: “Do you know anyone affected by the conflict? How are they faring?”

And if you want to shift to the meta frame, ask: “What do you think about the way people are talking about the conflict? Is that contributing to the division?”

Finally, it’s always useful to have some conversation exits ready and waiting in case things go off the rails or things become a bit too heated or distressing. You can say things like: “that reminds me of…”, or “I wanted to ask you about…”, or even “have you seen…”, and fill in the blanks with content that you think will be appealing to your conversation partner, whether that’s something about themselves (always a favourite topic), sport, popular culture or something else that everyone can relate to. There’s no shame in tactfully changing the subject when you feel a conversation has exhausted itself (or you).

Talking about difficult issues like the conflict in the Middle East can be distressing, but there are ways for you to take charge of the conversation and steer it in a way that is ethical, respectful and yet protects you and those around you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Anti-natalism: The case for not existing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

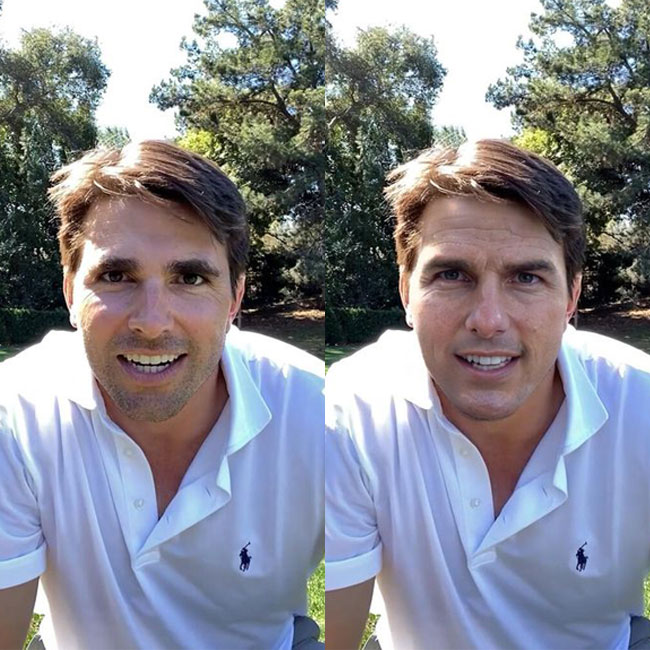

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

WATCH

Relationships

What is the difference between ethics, morality and the law?

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Schools of thought: What is education for?

Schools of thought: What is education for?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Georgia Fagan 3 OCT 2024

Education is often seen as an economic investment in our future. But philosophers have argued it could be so much more than this.

Education is often seen as a tool that we use to get us other things that we want; we tend to value education instrumentally. We know that the higher our educational attainment, the higher our future income, and most of us see this increase in future economic value as one of the central values of education. We understandably see greater financial security as a means to achieve greater happiness, a way to avoid stress and enjoy a greater sense of freedom and agency in our lives.

But what else could education be for that it seemingly isn’t for at the moment? What other value could it have for ourselves and the communities in which we are embedded?

Many people believe that economic instrumentality shouldn’t overshadow other potential goals of education. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum writes:

“We are living in a world that is dominated by the profit motive. The profit motive suggests to most concerned politicians that science and technology are of crucial importance for the future health of their nations… my concern is that other abilities, equally crucial, are at risk of getting lost in the competitive flurry, abilities crucial to the health of any democracy internally and to the creation of a decent world culture.”

Nussbaum is concerned that a failure to sufficiently interrogate what systems of education should be used for, leaves those systems vulnerable to a corporatisation that neglects their more comprehensive capacities.

Social critic Henry Giroux echoes these concerns, saying:

“You can’t have a democracy without informed citizens. That’s why education has to be at the centre of any discourse about democracy, and it isn’t. That’s where the left has failed. It has failed to run education. They failed because they believe that the most important structures of domination are entirely economic…”.

In 2027 the NSW primary school curriculum will undergo its biggest change in 30 years. Amongst this will be a new focus on democratic roles and the history of voting. Teaching students about democratic systems is useful, but it’s not enough. We must also teach them to interrogate their own beliefs and deliberate with others whose beliefs differ from their own. This is a skill which Nussbaum calls Socratic self-criticism. She describes it as “the ability to transcend local loyalties and to approach world problems as a ‘citizen of the world’; and, finally, the ability to imagine sympathetically the predicament of another person”.

For Nussbaum (and Socrates) education should aim to create citizens who are skilled in thinking for themselves, in reasoning well alone and with others. Similarly, Giroux thinks education should make individuals “aware of their own cultural capital… and their place in the world”. Nussbaum and Giroux both argue that education should not only give students what they need to lead economically comfortable lives, but also ensure that these lives are self-aware, and meaningfully engaged with the world around them.

Both theorists begin to suggest ways in which their theories can be made into practice. Giroux emphasises the need to engage students in discussions and forms of thinking that allow them to consider their own narratives about the world. This requires understanding the ways in which they are situated within it, and how that situatedness may differ from those around them.

This idea echoes Nussbaum’s argument that education should teach students to think critically about their own traditions. Both these proposals require curriculums that directly consider the perspectives of other people and cultures to stimulate critical self-reflection. Questions like: “what do I believe in and what are my reasons for those beliefs?”, “what do I think of the alternative beliefs?”, and finally, “do I or do I not want to change my thinking in this instance?”.

The development of aspects of Socratic self-criticism already exists as a byproduct of education curriculums, but Nussbaum and Giroux are motivating us to consider what it would look like to bring these aims to the centre of schooling. An example may be through the inclusion of a core subject concerning ethical deliberation. The best preliminary example of this sort of subject may be the Primary Ethics subject model. Currently, this is an hour long, weekly class carried out as an opt-in secular alternative to special religious education in NSW primary and secondary schools.

Any such subjects should not be forged as tools to impart ethical dogmas onto young students. Instead, they should be spaces for developing critical thinking skills which arise from debate and deliberation with existing perspectives and counter perspectives.

Education is a hugely powerful system, one which we should thoroughly and frequently interrogate. Are we using this system in a way that aligns with our goals, both local and global? What are those goals, have they recently changed? Are we equipping an entire generation with the tools they require to live comprehensively fulfilling and meaningful lives? The possibilities for our educational systems are boundless and it’s time that we begin realising this.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Joseph Earp 23 SEP 2024

The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, the 2005 young adult drama film, takes all of five minutes to set up its premise: what if you and your friends discovered the titular pair of jeans, which, despite your differences in size, fit you all perfectly? And, more than that, what if you all decided that these pants had magical behaviour-changing powers?

So far, so teen drama, particularly when the film starts unveiling the emotional canvas the film will play out on. Bridget (Blake Lively) has a crush, and a dead mother; Carmen (America Ferreira) is a child of divorce; Tibby (Amber Tamblyn) is stuck working a dead-end job.

But what is extraordinary about the film is the sensitivity with which it handles what could otherwise be tropes. Each of the heroine’s lives is disrupted by death and loss. They learn they are fallible; that they are subjected to forces they cannot control. They’re not whiny teenagers. They’re young people, making their way through the world – sometimes messily, but always with conviction.

The film is shockingly emotionally nuanced for a work of art made for, and about, teenagers. But what makes it more shocking is how plainly it exposes the absence of similar art for young men. The Sisterhood of The Traveling Pants – and films like it – are a core part of moral education, designed to validate young women in their feelings, both the positive and the negative. So, where is the male equivalent?

Art and moral education

None of this is to say that The Sisterhood of The Traveling Pants need only appeal to young women – the brush with which it paints is broad and vivid enough for those of any gender. But it still remains the case that the film was marketed to, and largely consumed by, young women. It sits alongside Stick It, She’s The Man, Riding In Cars With Boys, and Cinderella Story as part of an early 2000s trend of emotionally adult works directed towards young women. While these are stories are ostensibly about romance, they’re actually about self-discovery and self-possession.

Such films, as philosopher Greta T. Cullen observes, need not necessarily be “morally instructive” – as in, they don’t need to have all the moral answers. Instead, they ignite sympathy. They teach us both about our own world, and the worlds of those around us. As Cullen puts it, they “encourage an awareness of other people, their problems and sufferings.” Through that awareness, we can build a proper moral system – after all, it’s only when we understand how we affect other moral agents that we can decide how to treat them.

That, in fact, is precisely what makes art so important in moral education. The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants isn’t prescriptive – it doesn’t tell us exactly what we should do. In fact, its heroines make more mistakes than most: Tibby, whose life is changed by a young girl with cancer, initially declines to visit her dying friend in hospital. The film isn’t an instruction guide. Instead, it’s a sort of training ground for sympathy, reminding us of the impact we have on each other – and the seriousness with which we should take that impact. Art, at its best, makes the world bigger. And after it has done that, we get to decide what to do with all that extra space.

The stoic male hero

Art targeted at young men is far less interested in interiority. Consider the likes of Deadpool, Top Gun: Maverick, and The Fast and The Furious films. These works of art are not interested in emotional nuance in the same way as The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants is, because they’re not centred around emotionally changeable characters. Neither Deadpool nor Dominic Toretto need overcome internal obstacles – only external ones.

Art for young men tends to promote stoicism or, at the very least, inflexible leading men. Leads of young adult films directed at men are primarily unflappable – above all else, they value calm, and decisiveness. They are what Jon Brooks describes as “stoic superheroes”.

That’s not to say such art needs to be entirely dismissed – it has other uses. But the hole in male education around emotions – what we do with them, how they shape us – has profound knock-on effects.

When your heroes don’t validate you in your emotional complexity – in your essential fallibility – your moral life suffers. There is a loneliness to growing up without seeing a complex inner life on the screen. Films should, in some complicated way, forgive us. They should make it clear that we are not alone.

That loneliness is solidified by a further absence in young male cinema – a hole where there should be depictions of non-judgmental, accepting friendships. The “buddy comedy” genre does aim to rectify this gap, but such films are few and far between. The Sisterhood Of The Traveling Pants models genuine connection between its heroes, who are willing to be their true selves around each other. There is no real corollary for men.

There’s a sequence part way through The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants where Tibby, the teenage shelf-stacker, steps out into the quiet of the afternoon, surrounded by her middle-aged co-workers as they smoke in the sun. She says nothing; they say nothing.

Later, this will become the setting where Tibby learns not just about loss, but also about the hard-won work required to give life meaning. For the moment though, all that happens is that Tibby stands there, the sky orange around her, and takes pause. It’s a moment of true emotional vulnerability – a brief flash of Tibby sitting in her feelings.

And that vulnerability is important. Without that vulnerability, genuine emotional connection is impossible. Which is why the dearth of such moments in art aimed at young men has such worrying implications. Many men struggle with their own vulnerability; struggle to feel authentic, and true. From that comes loneliness. From that comes pain.

There is a hole in male education, and it’s shaped exactly like this film. And, more specifically, a hole shaped like the image of a young woman, standing in the sunshine, staring straight ahead, and then slowly walking offscreen.

Image: Warner Bros. Pictures

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Narcissists aren’t born, they’re made

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

What comes after Stan Grant’s speech?

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ask an ethicist: Is it OK to steal during a cost of living crisis?

Ask an ethicist: Is it OK to steal during a cost of living crisis?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 SEP 2024

The cost of groceries is spiralling out of control. Meanwhile, the major supermarkets are making a killing. I can barely afford the fuel to get to work, let alone fresh food for dinner. Surely, it’s OK for me to pilfer the odd packet of beef patties or punnet of strawberries?

It sometimes feels like the grand bargain of society is breaking down. We’re told that if we work hard, get a good education and don’t cause trouble then things will all work out – we’ll get a good job, be able to buy a home and we can still afford the odd luxury. But many of us are discovering that even when we play by the rules, we still feel like we’re falling behind.

And then we see the price of asparagus has gone up again. It’s not like asparagus farmers are getting rich. Neither are we. But the supermarket duopoly is. The outrage at this apparent injustice is understandable. And some of that outrage is tipping over into shoplifting, with the big supermarkets registering a surge in theft.

But – brace yourself – as an ethicist, I’m going to remind you that stealing is wrong. Well, it’s almost always wrong, especially if you’re only stealing out of a sense of outrage.

The thing about outrage is that it demands satisfaction. It motivates us to punish a perceived wrongdoer. But whom do we punish when the wrongdoing isn’t perpetrated by an individual but by an unjust system? It might feel justified to place a finger on the scale to tip things back in our favour by nabbing a few essentials (and the odd packet of TimTams). But in doing so, we risk letting one injustice lead to another without actually tackling the problem in the first place. We might feel like we deserve fairer prices – and I think we do – but stealing isn’t the way to make that happen.

But surely pilfering a couple of peaches and a jar of pickles is a victimless crime. The big supermarkets are making a motza, and they factor theft into their bottom line. That’s a trifling loss for them, and a nice peach and pickle cocktail for me.

Here’s a pickle for you. While a single instance of shoplifting might not have a big impact, every instance adds up. Because supermarkets do factor in theft to their prices, the more stuff that goes missing, the more they jack up prices – not to mention investing more in anti-theft technology. So, you’re in part contributing to the very problem that is motivating your theft. And those higher prices impact everyone, including those who might be struggling even more than you are.

At the heart of ethics is the idea that we should take responsibility for our actions. Do you want to be responsible for making the cost of living crisis worse?

Then there’s the matter of principle. Every time you feel justified stealing, you’re allowing others to use that same justification to steal. You’re effectively endorsing stealing in general.

One missing pickle jar might not make much of an impact on prices, but if everyone swipes something, then pickles can pretty quickly become out of reach.

OK, OK. I’ll redirect my outrage to writing sternly worded letters to the newspaper about grocery prices. But what if I’m starving because I can’t afford even a packet of Kraft singles to get through the day? Is stealing justified then?

As I said earlier, stealing is almost always wrong. But not always. Mortal peril is one case where most ethicists would say that it’s permissible to steal. Say your child is dying of a preventable disease and needs medication immediately, but your local supplier jacks up the price to an unaffordable level at the last moment and refuses to make an exception. If there’s no other ethical way to save your child’s life, then stealing could be forgiven.

However, that doesn’t mean raiding the lolly aisle. Note the “no other ethical way” bit. Generally, we’re obliged to do everything we can to work within the bounds of ethics and the law before we step outside of them. So, if you’re struggling to afford food, and there’s a food bank nearby that is willing to help you out, then that’s where you ought to turn before stuffing celery down your jumper.

Similarly, if there were some perverse law that prevented you from legitimately buying necessities, then you could pull a Martin Luther King Jr and ignore that law. As he said:

“One has not only a legal, but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.”

In short: stealing is bad, unless stealing will prevent something worse from happening. If not, then leave that punnet of strawberries alone and save your stamina for fighting the unjust system in other ways.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Gender quotas for festival line-ups: equality or tokenism?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture