Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Big thinkerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAR 2023

In a world where some women still struggle to have their voices heard, there are many female thinkers whose contributions throughout history have impacted our thinking today. This International Women’s Day, we’re celebrating five influential Australian philosophers, activists, academics and thinkers who have shaped our ethical landscape and beyond.

Kate Manne

Kate Manne (1983-present) is an Australian philosopher best known for her feminist, moral and social philosophies, and her work around misogyny and masculine entitlement. Notably, instead of thinking of misogyny as hatred for women, Manne redefines the word and focuses on its systematic nature, specifically in how law enforcement polices women and girls to uphold gender norms.

To illustrate masculine entitlement, Manne coined the term “himpathy”, which explains “the disproportionate … sympathy extended to a male perpetrator over his … less privileged, female targets in cases of sexual assault, harassment, and other misogynistic behaviour.” She took a deep dive into this idea in her 2020 book Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women and critiqued Justice Kavanaugh’s appointment to the US Supreme Court, despite allegations of sexual assault, as “himpathy” in action.

Marcia Langton

Marcia Langton (1951-present) is considered one of Australia’s top academics, anthropologists and geographers. As the great–great–granddaughter of survivors of the frontier massacres and a Yiman person, Langton uses her influential platform to advocate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. When her great aunt Celia Smith, an organiser of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, convinced her to work with the council in 1967, Langton was launched into her outspoken career of Aboriginal activism.

Since, she’s worked on vital pieces of research and legislation impacting Indigenous people and has held the Foundation Chair of Australian Indigenous Studies at University of Melbourne since 2000. More recently, she’s worked on the Voice to Parliament that would recognise First Peoples in the Constitution, permitting them “to have a say in the legislation that affects their lives.” To her, upholding Indigenous knowledge and rights goes beyond environmental preservation: It’s cultural preservation.

Veena Sahajwalla

Veena Sahajwalla (undisclosed-present) is an Australian scientist, inventor and professor. Named one of Australia’s 100 most influential engineers in 2015 and one of the 100 most innovative in 2016, Sahajwalla is putting New South Wales on a path to a net zero carbon, circular economy. Nicknamed “Queen of Waste”, she’s worked to repurpose everything from old clothes to beer bottles and abandoned mattresses. Growing up in Mumbai, India, she was introduced to the art of recycling through waste-pickers.

Her most famous invention, “Green Steel”, replaces coking coal in steel production with old, shredded tyres. The process is much less carbon-intensive and prevents 2 million tyres from hitting the landfill each year. This, in addition to her numerous other achievements – such as being councillor on the Australian Climate Council and opening the world’s first e-waste microfactory on the University of New South Wales’s campus – led to her being named Australian of the Year in 2022

Germaine Greer

Germaine Greer (1939-present) is a writer and regarded one of the major voices of the radical feminism movement in the latter half of the 20th century. Born in Melbourne, her 1970 book, The Female Eunuch, made her a household name where she argued the expectation for women to be feminine – in the clothes they wear, in marriage, in having a nuclear family – is what represses them. And so she calls for liberation, for revolution, because this repression cultivates political inaction.

Since then, she’s written several other books on feminism, literature and the environment. Of all her ideas and claims, she holds that freedom is the most dangerous, though critics say otherwise. Some of Greer’s views of have created controversy, including her views on gender binaries and expressions, rape and the #MeToo movement. While her audacious language, beliefs and controversy have cultivated furore at times, Greer remains a prominent participant in intellectual discourse and debate.

Val Plumwood

Val Plumwood (1939-2008) was an Australian philosopher, activist and ecofeminist. Her work focused on anthropocentrism and discouraging the idea that humans are superior to and separate from nature. This “standpoint of mastery”, as she called it, legitimised the “othering” of the natural world, which included women, indigenous and non-humans.

She experienced a major paradigm shift that coloured her opposition to anthropocentrism after she was attacked by a crocodile while canoeing alone at Kakadu National Park. She couldn’t believe such a thing was happening to her, a human. She went from being top of the food chain to part of it, having “no more significance than any other edible being.” To Plumwood, the flawed mindset of only human life mattering is the root of our planet’s degradation. She proposed nurturing the natural world for nature’s own good instead of our own, famously questioning, “Is there a need for a new, an environmental, ethic – an ethic of nature?”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Why I had a vasectomy at 30

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Agree to disagree: 7 lessons on the ethics of disagreement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 3 MAR 2023

The undead are everywhere. It’s not just that our culture is obsessed with zombies, from The Walking Dead to The Last Of Us. It’s that our cultural discussions are zombies themselves – they just won’t die.

We go over the same old arguments time and time again, to no seeming progression or end. Just take the cultural discussions around depiction and endorsement where the lines have been drawn in the sand.

For those on one side of the line – the instigators of this particular debate – artists who depict monstrous acts are seen to be agreeing with these acts. The mere depiction of violence, for instance, is seen as a kind of thumbs up to that violence, tacitly encouraging it.

On this view, artists are moral arbiters, and the images and stories that they put out into the world have a significant, behaviour-altering effect. Depicting criminals means “normalising” criminals, which means that more viewers will believe that criminal acts are acceptable, and, theoretically, start doing them.

This view has a historical precedent. Art has long been political, used by states and religious groups in order to provide a form of moral instruction – consider devotional Christian paintings, which are designed to exhort viewers to better behaviour.

Certainly, there are still artists and artworks with a pointedly ethical and political mode of instruction. From government PSAs that borrow storytelling techniques that artists have used for years, to the glut of Christian-funded films like God Is Real, art objects have been designed as transmission devices for a particular point of ethical view. Even Captain Marvel, another in a seemingly unending glut of superhero movies, was created in partnership with the airforce, and depicts the military in a childishly positive light.

But acting as though all art has this moral framework – that everything is a form of fable, with a clear ethical message – is a mistake. Moreover, it elevates a discussion about art beyond what we usually think of as aesthetic principles, and into political ones. It’s not just that the instigators who view all art as essentially and simply instructional worry we’re getting worse art. It’s that they worry we’re getting more dangerous art.

In just the last 12 months, Martin Scorsese has been condemned at least three times in some circles of the internet for glorifying depravity with his films about criminal underbellies.

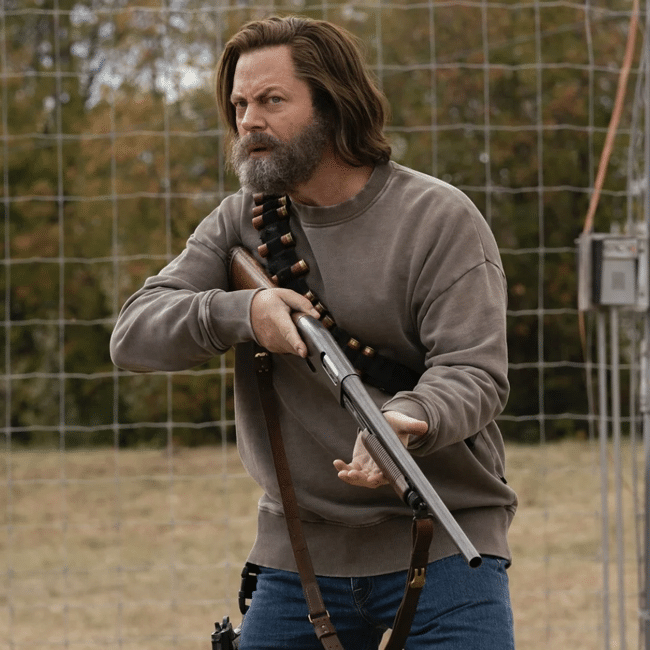

But the argument really saw its time in a sun that won’t set with the release of the bottleneck episode of The Last of Us, a much heralded – and deeply contentious – piece of television.

Fungal Zombies And Queer Representation

In the episode, Parks and Recreation’s Nick Offerman and The White Lotus’ Murray Bartlett embark upon a queer romance while the world ends around them. Though highlighted for its sensitivity in some corners of the discourse, the episode received significant pushback.

For writer Merryana Salem of Junkee, the episode was an example of “pinkwashing”, due to the fact that the characters value “individual liberty over community good.” As in – they try to survive during an apocalypse. Salem criticises the show for depicting queer characters looting and pillaging, rather than sharing resources. By aligning queer representation with selfish behaviour, Salem appears to be arguing that the show will platform and perhaps normalise libertarian values of the self as important above all others.

“Far from framing this attitude as negative, a song plays cheerily over Bill hoarding, looting resources, and setting up security systems that would prevent anyone in the immediate area from even using the electricity in the local plant”, Salem writes.

The argument here is simple. One act is shown onscreen instead of another. That is a choice. The choice, combined with the aesthetics around it – cheery music – means that this choice is designed to impress upon the audience the admirable nature of the character, even as he does less than admirable things.

What such an argument precludes, however, is the complexity inherent in the episode. The Last of Us’ showrunner, Craig Mazin, may not be pointing at good and bad as directly as his critics assume. Bill is a man trying to carve out love and life under impossible circumstances. In an ideal world, he wouldn’t be hoarding resources. In an ideal world, he would be living quietly, in a community. He doesn’t want to make do in the middle of a zombie outbreak.

The beauty of the episode, then, is the way it makes a case for the power of an easy love formed under uneasy circumstances. Bill’s flawed because he’s been made that way by an outbreak of, ya know, fungus zombies. And yet still he finds some crooked form of redemption in the arms of another.

That’s what is missing from so many of these debates about depiction versus endorsement – nuance.

Good storytellers don’t depict flatly. They depict with complexity. With differing shades of light and dark. And so their art should be analysed on those merits, with criticism that is itself complex.

But more than that, we need to ask ourselves, finally, whether depicting reprehensible acts onscreen really has the effect that these critics assume it does.

The Return Of The Big Bad

Take some of the most reprehensible people on television. Walter White of Breaking Bad. Tony Soprano of The Sopranos. Even Don Draper of Mad Men. These men, who washed over our screens during the start of the Golden Age of Television, do bad things.

More than that, they get rewarded for them. Tony is lavished with success of all forms – money, power, opportunity. Walter finds, through drug-dealing, a new level of self-confidence and authority. Don never gets a traditional comeuppance, unless you take the constant unease in his soul as a form of comeuppance.

These characters are explicitly rewarded – in some ways – for their immorality. They get away with it. Even Tony, whose fate is hinted at but never explicitly shown, gets a moment of peace before he goes. Don’s sitting there with a big old grin on his face the last time we see him. And sure, Walter gets snuffed out, but on his own vicious terms.

And so what? Are any of the creators behind these anti-heroes really suggesting that we should turn to crime or adultery? If they are, then they are not artists – they are salesmen.

Art is better when we treat it as nuanced, complex depictions that leave it to us to do the work of untangling.

Indeed, through immorality, these characters suggest that the only thing worse than these flawed and difficult characters is the world around them – the world that rewards them. It’s not Don that’s the isolated problem, cutting a swathe of heartbreak and cashing a big old cheque. It’s that the structure around him is misogynistic and capitalistic. He is the perfect product of his era. And the depiction of his moral crimes isn’t meant to encourage us to applaud those crimes. It’s meant – at least on one interpretation – to make us question the whole system that props us up.

It’s a mistake to hanker for art that only operates in one moral mode; that punishes the wicked, and celebrates the innocent. Not even fairy tales are that simplistic. We live in an era in which even our zombie TV shows are filled with nuance and complexity. Let’s engage in discourse worthy of that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The power of community to bring change

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Big thinkerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 15 FEB 2023

In celebration of Sydney World Pride and Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, we’ve profiled nine notable thinkers who have contributed to our understanding of gender, sexuality and identity in some way. Whether navigating such spaces themselves or contributing to prominent research in the field, these figures have propelled public awareness of LGBTQIA+ issues in a meaningful way.

Michael Foucault (he/him)

Michael Foucault (1926-1984) was a daring, outspoken French philosopher, historian and psychologist. Much of his work was concerned with power and the random, coincidental ways in which big ideas and movements manifest in public consciousness. He explored the idea of sexuality in great extent and the modern fixation to define it and attribute sexual relations to an identity. To him, such definitions and labels effectively “other” parts of the population whose sexual behaviours are seen as deviant from the norm, even though evidence of same sex relations is present throughout human history.

Foucault thoroughly explored these ideas in his study, The History of Sexuality. He did not believe sexuality could be definitively defined – and any attempt to define it, in his eyes, constrained the mobility of human sexuality, which he believed ought to be fluid. Foucault’s provocative ideas and the content of The History of Sexuality laid the foundation for what Teresa de Lauretis would later call “queer theory”.

Judith Butler (they/them)

Judith Butler (1954-present) is an American activist whose writings and philosophies colour their commitment to radical equality. They are best known for writing Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, which is widely considered a founding text of queer theory. In the world-renowned book, Butler rejects the stance that gender equals biology, instead viewing gender as a product of behaviours and self-expression. To them, gender is produced by performance and is the root of their idea of “gender performativity”.

To eliminate any confusion on its definition, Butler explains that “We are formed through gender assignment, gender norms and expectations. But we’re not trapped. We can work and play with them [and] open-up spaces that feel better or more real for us.”

Audre Lorde (she/her)

Professionally a poet, professor and philosopher, Audre Lorde (1934-1992) also proudly carried the titles of intersectional feminist, civil rights activist, mother, socialist, “Black, lesbian [and] warrior.” She is also the woman behind the popular manifesto “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Lorde’s self-expression and personal philosophy has became one of the greatest contributions to the discourse on discrimination and equality today. By offering an authentic depiction of the female, queer and Black experience, she portrayed the good, the bad and the complex. She felt academic discourse on feminism was white and heterosexual centric, lacking consideration of the lived realities so she put the stories of these women at the centre of her literature. An advocate for difference amongst human beings, Lorde’s difference was key to helping eradicate discrimination and moving forward in unity.

Raewyn Connell (she/her)

Raewyn Connell (1944-present) is an Australian sociologist. Born in Sydney, she approaches her research work with what she calls “southern theory”. Essentially, this perspective gives space to the global south’s backgrounds, which are often overshadowed by northern narratives. Connell was initially recognised for her research on class dynamics, exploring how class and power are inextricably linked and thus defined class as a social structure. This social framework propelled Connell into the realm of sexuality, which she also viewed as a social structure. Exploring how class influences and shapes gender, she understood gender as multi-dimensional and subject to change; something far beyond a mere aspect of our social identity.

In Masculinities – one of her most famous works — Connell coined the term “hegemonic masculinity”, which is the most dominant and socially celebrated version of a man. Though best known for her work in male studies, she explained that “my theoretical concern was the gender order as a whole; masculinity was one piece of the jigsaw”. Additionally, she’s written about her experience as a trans woman, gender equality, poverty, AIDS prevention and education.

Dennis Altman (he/him)

Dennis Altman (1943-present) is an Australian queer thinker and professor of politics at La Trobe University. His 1971 book, Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation, kickstarted his outstanding career that eventually led The Bulletin to name him one of the 100 most influential Australians. He primarily pondered the differences between radical gay activists who question heteronormative frameworks versus the tamer gay equality activists who demanded space in such frameworks. As time went on, Altman’s predictions of the normalisation of homosexuality laid out in his 1971 book proved correct. And though such advancements are certainly ones to celebrate, part of Altman mourns the radical roots of gay liberation.

For his complete support of gay rights, his opposition of same sex marriage might come as a surprise, but not if you consider the fact that he opposes marriage of any kind. In rejecting “the assumption that there is only one way of living a life”, Altman never married his partner of twenty years. He vehemently stands by the “equal right not to marry” and refuses to seek permission from the state and religious bodies that don’t want to sanction same sex relationships.

Susan Sontag (she/her)

Susan Sontag (1933-2004) was a relentless and prolific writer, philosopher, playwright, filmmaker and activist. She obsessively pursued the truth and had the courage to express it, no matter how unpalatable. To her, “All understanding begins with our not accepting the world as it appears.” Sontag’s first notable work, Notes on “Camp”, is what propelled her into the public eye, especially after it appeared in Time Magazine. Best known for detailing modern culture and aesthetics, her work expanded definitions of the word “camp” – for instance, using it to define works of art when they fail at being serious.

Her extremely publicised divorce from sociologist and cultural critic Philip Rieff in 1957 forced her into the public eye and involuntarily exposed her sexuality. Rather famously, after that event, she never formally came out as lesbian or bisexual. On this, in an interview with the New Yorker, she said, “That I have had girlfriends as well as boyfriends is what? Is something I never thought I was supposed to say since it seems to me the most natural thing in the world.”

Natalie Wynn (she/her)

Natalie Wynn (1988-present) is an American, Baltimore-based YouTube personality whose work aims to educate via theatrical entertainment and humour. In a play-like fashion, Wynn plays different characters and wears complex costumes to try and voice all sides of an issue, from which the audience can draw their own conclusions. On her channel, ContraPoints (like counterarguments), she tries to make people think; and beyond that, she wants them to question why they think that way in the first place. Wynn questions, “What matters more: The way things are or the way things look?”

As a transgender woman, many of her videos tackle trans experience, sexuality and gender roles. Wynn principally tries to depolarise conversations that typically divide people and humanise those who are questioning their own identity and sexuality. She claims that “in a free society, different people will have lots of different sexual lifestyles,” and she uses her platform to give space to such lifestyles.

Masha Gessen (they/them)

Masha Gessen (1967-present) is an unreserved, influential journalist, activist and author. Born in Russia, they relocated to America to realise greater sexual freedoms. Called “Russia’s leading LGBT rights activist” they have candidly discussed living in Russia as an openly gay person at the time – where homosexual propaganda is illegal and removing children from same sex households is possible.

Gessen has brought international queer issues into academic discourse to better understand the anti-queer movement, like that in Russia. They’ve blatantly critiqued Russia’s president Vladimir Putin since he was first elected and holds that former American president Donald Trump is “worse” than him. Gessen continues to expose injustices and Russia’s rise of LGBTQIA+ hate crimes in the wake of the state’s homophobia.

Alok Vaid-Menon (they/them)

Alok Vaid-Menon (they/them) is an internationally acclaimed writer, comedian, poet, and public speaker whose work explores themes of trauma, belonging, and the human condition. Their 2020 book Beyond the Gender Binary has been described as a “clarion call for a new approach to gender in the 21st century.”

Their approach to fundamental and often violent clashes with peace and compassion can feel radically hopeful. Vaid-Menon says “I’m fighting for trans ordinariness… I want to be able to walk down the street wearing what I want without it having to be an event.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Bondi massacre: A national response

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe our friends

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 9 FEB 2023

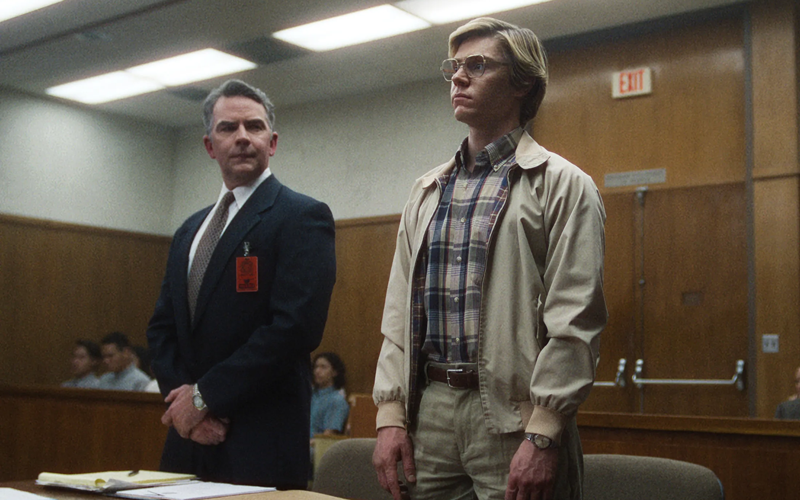

In January 2023, actor Evan Peters took to the stage to accept a Golden Globe for his performance as Jeffrey Dahmer in the surprise streaming success Monster – The Jeffrey Dahmer Story.

It was a moment of odd contrast. There was Peters, dressed in a Dior suit, surrounded by opulence of the highest order and luxuriating in the most comfort and security imaginable — rich, safe, protected — accepting an award for his portrayal of a serial killer. More than that, the families of Dahmer’s victims were nowhere to be seen. As the actor collected the gong, those whose lives had been forever shaped by the crimes of a serial killer — second-order victims, whose narratives had been used for art — were off-screen.

It was a moment that crystalised the strangeness of our modern obsession with true crime, an obsession that is taking over the entertainment industry, and swamping podcast feeds and our small screens. In swathes of the Western World, we are safer than ever before from the threat of another Dahmer — and yet, in our post-Making A Murderer world, ripped from the headlines stories of violence and immorality are everywhere, even as such experiences are becoming, for most of us, as alien as stories set on Mars.

And such stories have real-life victims who are still with us; still alive, and in many cases, still grieving. These people who deserve emotional security are being ignored and overwritten by Hollywood.

Why then can’t we get enough of Ed Gein, and Ted Bundy, and the mountain of murderers that fill up our screens? What are the ethics of engaging with these traumas casually, over dinner, or on our way to work? And what can we do to make this immensely popular sub-genre genuinely ethical?

Why Are We Getting Off On Murder?

It would be wrong to suggest that our current moment of true crime consumption is a total deviation from past trends. Stories of horror and amoral behaviour have been with us since at even earlier than the time of the Brothers Grimm — most oral storytelling revolved around bloodshed, deviants, and murder.

It would also be wrong to suggest that true crime is an empty or useless art form. Art is therapeutic because it allows us to explore and imagine heinous violence and immorality from the safety of our homes. It’s a tool for processing collective fear; collective horror. It’s a way for us to explore how we feel about our own moral systems, by examining the lives and actions of those who deviate from those systems.

However, it’s the “based on a true story” tag that makes true crime distinct. It is hard to imagine that Monster would have the same impact on the mass culture if it was a total fiction. The “true” in “true crime” is part of the sell.

Engaging in the world of true crime means engaging in a world where serial killers lurk around every corner. For those of us living in cities in the Western World, that is far from true. Serial killers were always the aberration to the rule. Now, they’re positively alien — in the U.S., serial crime makes up less than one percent of all crimes recorded. For those of us with class privilege, our deaths will come, most likely, from heart disease, not a sociopath in oversized glasses who will later mummify our heads.

Why true crime has blossomed in the context of these cultural shifts is hard to say. Could it be a result of the passivity baked into entertainment these days? So much of us binge shows to tune off, switch out, and relax on the couch. True crime is excitingly different. Podcasts like My Favourite Murder, or smash hits like Making A Murderer gives audiences an opportunity for further engagement that extends after the credits roll. You can read Wikipedia pages. You can listen to more podcasts; watch spin offs; read testimonies. And that means you can become a sort of detective of your own, sniffing out leads, becoming not just a watcher, but a researcher.

Blood On Whose Hands?

The cultural context for our obsession with true crime adds a string of ethical dilemmas to consuming it. For a start, our obsession is coming a time where we are more able than ever to educate ourselves on the crooked and fundamentally broken nature of the police force. Most true crime is ‘copaganda’, saturating the populace with the myth that most police officers are inventive, savvy artists stringing together clues, rather than overfunded, inadequate mental health professionals at best, and the violent arm of the state at worst.

True crime also plays uncomfortably into pre-existing racial divides. In most true crime shows produced in the United States, Australia and the UK, the victims come from ethnic backgrounds that are not white. The cops, by contrast, are white. The looming threat of the white savior narrative is thus unavoidable. Just as problematically, race is an unspoken presence in most true crime, rarely acknowledged, and glossed over by artists in favour of the flashier, gorier elements of these stories.

Finally, real-life crime means real-life victims. Dahmer’s victims have children; friends. These crimes leave intergenerational traces – there is a legacy of pain that drips down bloodlines after a life is cruelly and inhumanely snuffed out. Not only have these second-order victims lost a loved one, they’ve seen that loved one turned into newspaper headlines and bit players in a swathe of miniseries and podcasts.

Creators of true crime art have a responsibility to these families. The reason for this responsibility is two-fold. Firstly, these stories would, devastatingly, not have happened were it not for the victims. In the worst, most painful way, Dahmer was who he was because of the people he killed. His story is their story, and any Hollywood creative who tells that story and makes a dime is profiting off the pain of victims. Ryan Murphy, Monster’s creator, has a net worth of $150 million. Evan Peters has a net worth of $4 million. Both have enjoyed significant financial success from Monster that the second-order victims of Dahmer have not.

Creators of true crime art have a responsibility to these families… The worst moment of these people’s lives are being turned into entertainment.

The pain of those whose lives were affected by Dahmer provides the second reason for the responsibility of true crime artists — these victims and their families are just that. Victims. The worst moment of these people’s lives are being turned into entertainment. All the award shows that Peters and Murphy get to swan about at seem actively exploitative, given the human suffering that they took from real-life, and fashioned for the screen.

The way to resolve this responsibility is proper financial remuneration. These families deserve to be compensated for their stories, and for their pain. Moreover, such an obligation extends beyond just those involved with Monster, and implicate all true art creators, no matter the medium. How often have you listened to a true crime podcast, in which a grisly murder is being detailed, only to have your experience interrupted by a jocular advert for mattresses and at-home meal kits? These moments sit the grisly murder next to the adverts that make the creators of such content wealthy – throwing into focus that the true crime industry is just that — an industry.

Sure, in a capitalist system, all art has to be commercially minded to some extent – art is expensive to make, and artists deserve to be compensated. But the integration of advertising into true crime feels particularly craven. The money must be shared. Those who deserve to be paid should be paid.

None of this is an argument for shutting down true crime art, or censoring it or banning it in any way. True crime, for its flaws, serves a purpose. It can make us think about class; about context; about law. But to be truly ethical, true crime must shift its relation to the victims who are involved in these stories. Otherwise, there’s blood on the hands of more than just the murderers.

For more insights into our consumption of true crime, tune into the FODI22 discussion, The Crime Paradox

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 8 FEB 2023

The fun of betting on uncertain outcomes is not a problem. But addiction, organised crime and ubiquity make excessive gaming a social ill that needs a policy fix.

Debate about the regulation of gambling has intensified to the point where the sound and fury from all sides risks obscuring the central issues that must be addressed. With that in mind, I would like to offer a perspective on how the issue appears when viewed through the lens of ethics – rather than commerce or politics.

The essence of gambling is to take on risk in anticipation of a hoped for (but uncertain) reward. In that sense, pedestrians “gamble” when they try to save time by dodging through traffic rather than walking to a designated crossing. The same goes for those who make an “educated guess” when investing in equities. Like the punter who puts down a “prudent bet” – based on studying the form, visiting the track and so on – an active investor who takes into account “the fundamentals” is gambling.

However, not all forms of gambling are equal. Some are built around systems of probability that are consciously tuned so as to enable “the house” to win more than their customers lose over time. So long as everyone knows this, there is nothing problematic about this form of gambling. It’s perfectly acceptable to choose to spend money on entertainment.

So, if the practice of gambling is so innocuous, why all the fuss?

The answer is to be found in three forms of harm that, although external to the practice of gambling, have become intimately connected to it: addiction, organised crime and ubiquity.

First, the most serious harms caused by gambling are to individuals who become addicted to it. However, it is essential that we note that the “evil” is addiction – not gambling as such. Addiction to work or sex or chocolate is all deeply problematic for those who are afflicted. However, that does not make work, sex or chocolate intrinsically harmful.

Unfortunately, some parts of the gambling industry seek to exploit the addictive tendencies of some people. There are wicked individuals and organisations who seek out means to “hook” people on their gaming product. They do this through conscious design of machines, experiences, incentives … almost anything. There is no “accident” in this. The trap is deliberately set and snares whoever it can catch.

At the lower level of complicity are those who do not design to capture the addict – but rather fail to take adequate steps to protect them from harm.

Let’s avoid ‘wowserism’ of a kind that presents gambling as the problem. It is not.

It is perfectly acceptable to design for fun, excitement, or enjoyment. However, people in the gambling industry have a particular obligation to use all effective means to minimise the risk of harm to those who are susceptible to addiction. Failing to do so leads to tragic outcomes – and there is no way people in the industry can wash their hands of blame for what might reasonably have been prevented, if only a sincere effort had been made to do so. Instead, some try to block reforms, simply to advance their commercial interests.

Second, as law-enforcement agencies have highlighted – again and again – organised crime has got its hooks into the gaming industry. Criminals see their “regulated losses” as an acceptable cost to bear for the convenience of being able to “launder” vast amounts of cash through gambling.

Once again, the “evil” of organised crime is not intrinsic to the practice of gambling. Crime is pernicious wherever it rears its ugly head. It is simply an unfortunate fact of history that, for selfish reasons, criminals have developed a close association with the gaming industry. However, there is nothing necessary about that connection – which can and should be severed.

Finally, there is the problem of “ubiquity”. One of my earliest published articles on this topic noted that while there is nothing intrinsically wrong with, say, church choirs, it would be unspeakably destructive of the common good to place one on every street corner. You can have too much of even the best things (not sure that church choirs count).

Gambling is everwhere! This is especially so now that the “gambling bug” lives inside our phones and other communication devices. I have seen the banking records of a person who, having been driven to an insane level of addiction, lost all the money awarded in a workers’ compensation payment by placing one bet … every six seconds.

The fact that a gaming company allowed this to happen is disgusting. It is almost as bad that we saturate our world with advertising that pretends this is never anything more than “a bit of fun with one’s friends”.

What does all of this mean for the current debate? First, let’s avoid “wowserism” of a kind that presents gambling as the problem. It is not.

However, if we wish to enjoy the fun of ethical gaming we must choose the means, as a society, to eliminate (or at least ameliorate) the evils of addiction, organised crime and ubiquity.

Despite claims to the contrary, the technology required for cashless gaming is already developed. It should be used with default daily betting limits that apply across all forms of gaming – on the track, in casinos, in clubs, online … wherever. And while we’re at it – can we regulate gambling advertising so that it does not invade every aspect of our lives … especially not those of children who are at risk of being convinced that betting on sport is better than playing it.

Some people doubt it is possible to run profitable gaming enterprises without exploiting the deadly trio of addiction, organised crime and ubiquity. I do not agree. Difficult? Yes. Impossible? No. Given that gambling can be a source of innocent joy, I think the effort is worth it.

This article was first published in The Australian Financial Review.

Disclosure: The Ethics Centre works with individuals and organisations committed to improving the ethical dimension of their business, including companies that either directly or incidentally have a connection with gambling.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Reports

Business + Leadership

Ethics in the Boardroom

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 25 JAN 2023

Moral injury occurs when we are forced to violate our deepest ethical values and it can have a serious impact on our wellbeing.

In the 1980s, the American psychiatrist Jonathan Shay was helping veterans of the war in Vietnam deal with the traumas they had experienced. He noticed that many of his patients were experiencing high levels of despair accompanied by feelings of guilt and shame, along with a decline of trust in themselves and others. This led to them disengaging from their friends, family and society at large, accompanied by episodes of suicidality and interpersonal violence.

Shay realised that this was not posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), this was something different. Shay saw that these veterans were not just traumatised by what had happened to them, they were ‘wounded’ by what they had done to others. He called this new condition “moral injury,” describing it as a “soul wound inflicted by doing something that violates one’s own ethics, ideals, or attachments”.

The “injury” is to our very self-conception as ethical beings, which is a core aspect of our identity. As Shay stated about his patients, moral injury “deteriorates their character; their ideals, ambitions, and attachments begin to change and shrink.”

Moral injury is, at its heart, an ethical issue. It is caused when we are faced with decisions or directives that force us to challenge or violate our most deeply held ethical values, like if a soldier is forced to endanger civilians or a nurse feels they can’t offer each of their patients the care they deserve due to staff shortages.

Sometimes this ethical compromise can be caused by the circumstances people are placed in, like working in an organisation that is chronically under-resourced. Sometimes it can be caused by management expecting them to do something that goes against their values, like overlooking inappropriate behaviour among colleagues in the workplace in order to protect high performers or revenue generators.

Symptoms

There are several common symptoms of moral injury. The first is guilt. This manifests as intense discomfort and hyper-sensitivity towards how others regard us, and can lead to irritability, denial or projection of negative feelings, such as anger, onto others.

Guilt can tip over into shame, which is a form of intense negative self-evaluation or self-disgust. This is why shame sometimes manifests as stomach pains or digestive issues. Shame can be debilitating and demotivating, causing a negative spiral into despondency.

Excessive guilt and shame can lead to anxiety, which is a feeling of fear that doesn’t have an obvious cause. Anxiety can cause distraction, irritability, fatigue, insomnia as well as body and muscle aches.

Moral injury also challenges our self-image as ethical beings, sometimes leading to us losing trust in our own ability to do what is right. This can rob us of a sense of agency, causing us to feel powerless, becoming passive, despondent and feeling resigned to the forces that act upon us. It can also erode our own moral compass and cause us to question the moral character of others, which can further shake our feeling that the other people and society at large are guided by ethical principles that we value.

The negative emotions and self-assessment that accompany moral injury can also cause us to withdraw from social or emotional engagement with others. This can involve a reluctance to interact socially as well as empathy fatigue, where we have difficulty or lack the desire to share in others’ emotions.

Distinctions

Moral injury is often mistaken for PTSD or burnout, but they are different issues. Burnout is a response to chronic stress due to unreasonable demands, such a relentless workloads, long hours, chronic under resourcing. It can lead to emotional exhaustion and, in extreme cases, depersonalisation, where people feel detached from their lives and just continue on autopilot. But it’s possible to suffer from burnout even if you are not compromising your deepest ethical values; you might feel burnout but still agree that the work you’re doing is worthwhile.

PTSD is a response to witnessing or experiencing intense trauma or threat, especially mortal danger. It can be amplified if the individual survived the danger while those around them, especially close friends or colleagues, did not survive. This could be experienced following a round of poorly managed redundancies, where those who keep their jobs have survivor guilt. Thus, PTSD is typically a response to something that you have witnessed or experienced, whereas moral injury is related to something that you have done (or not been able to do) to others.

Moral injury affects a wide range of industries and professions, from the military to healthcare to government and corporate organisations, and its impacts can be easily overlooked or mistaken for other issues. But with a greater awareness of moral injury and its causes, we’ll be better equipped to prevent and treat it.

If you or someone you know is suffering from moral injury you can contact Ethi-call, a free and independent helpline provided by The Ethics Centre. Trained counsellors will talk you through the ethical dimension of your situation and provide resources to help understand it and to decide on the best course of action. To book a call visit www.ethi-call.com

The Ethics Centre is a thought leader in assessing organisational cultural health and building leadership capability to make good ethical decisions. We have helped a number of organisations across a number of industries deal with moral injury, burnout and PTSD. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Or visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 22 DEC 2022

One surprising fact about Mike White, the creator, writer and director of HBO’s The White Lotus, is that he’s obsessed with and starred in a season of Survivor, the brutal reality TV show that pits strangers against each other in a complex game of wits and skill.

Of course White’s a Survivor junkie. The two seasons of The White Lotus – a soap opera-cum-murder mystery about a bunch of depraved rich people who exploit the surplus of expendable workers who man the titular hotel they stay at – are united by their fixation on the ways human beings outwit and outgame each other.

The White Lotus takes it as a given that human beings want things from each other, and use their (varying levels of) intelligence and power to get those things. There’s not an innocent in either season of the show, and their moral failings range from the petty and pathetic to the grand and soul-blemishing. Shane (Jack Lacy) kicks off the first season by whining and berating the hotel staff in order to get what he feels owed. Armond (Murray Bartlett), the long-suffering hotel manager, ignores one of his staff members when she goes into labour. They’re a den of thieves and miscreants, whose naked wants trump any sense of obligation to one another.

Even Tanya (Jennifer Coolidge), the only character who spans both instalments, is a hero only by virtue of being less openly murderous. Her slow realisation in the show’s second season that she is sat at the direct centre of a conspiracy motivated by greed is tragic, sure. But by the time we see her mutter her instantly iconic line about the gays who are trying to murder her, we’ve already watched her dangle her considerable wealth in front of Belinda (Natasha Rothwell) and then withdraw it, dishonestly, the moment she becomes the object of someone’s lustful affections.

These characters operate in what philosopher John Locke refers to as “the state of nature.” Locke, one of the founders of modern liberalism, believed that left to their own devices, without society, human beings live lives that are “nasty, brutish and short.” There is no sense of community, or solidarity, in the state of nature. All people want is what they want, and they live in a continuous state of never denying their desires.

So it goes in The White Lotus. The characters are nominally part of a culture – the kind of society that Locke hoped would block bad behaviour. After all, for Locke, mutual beneficence is the glue that holds us together – you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours. You refrain from killing me, so I won’t kill you either.

But Locke’s hope that the stratas and rules inherent in a society would keep its citizens ethical is blown apart by The White Lotus. Alliances form in the world of the show, sure. But these are temporary, fleeting, purely opportunistic. Belinda and Tanya don’t like each other. They need each other. Ethan (Will Sharpe) and Harper (Aubrey Plaza) might have a connection, but it’s not strong enough to hold together in the face of changing fortunes and friendships.

Importantly, so it goes across class divides. Though the show has been touted as part of a wave of modern works of art that take aim at the rich – from Parasite to The Menu – the show does not reserve its ire merely for the upper class. What sets The White Lotus apart from much “we are the 99%” cinema and television, is the way it examines the pressure that capital places on all citizens, the haves and the have nots alike.

Bitch Better Have My Money

Thorstein Veblen, the Austrian sociologist, is best known for his book The Theory Of The Leisure Class. Veblen examines the hallmarks of the elite, and finds one in common across a multitude of cultures. Simply put, Veblen says, rich people like excess. They like to spend money on things that they don’t have to spend money on.

The characters of The White Lotus are driven by this need for excess.

They want more than they could ever need. And because of this want, their lives are transformed into a series of opportunities. Wealth and power become means to garner more wealth and power.

The Di Grasso family of the second season are the perfect example of this. Some wealthy families have a “crest”, a pictorial representation of their values. The Di Grasso family’s crest would be a den of rats, ignoring their stockpile of food, and instead choosing to chew each other’s tails.

This is a family that, over generations, has learned that the world is nothing more than a series of goals, which lead to nothing but more goals. Bert (F. Murray Abraham), the family’s patriarch, has created a miniature culture that revolves around himself, in which sex is an opportunity for manipulation, wealth is an opportunity for manipulation, and love is an opportunity for manipulation.

And his brood, desperate to emulate him, and attract his affection – if only to get ahead themselves – have followed in his lead, even if they don’t realise it. For this family, nothing and no-one ever sits as they lay – nothing is discrete, or for itself. Bert might be viewed by the other characters as a mostly impotent, harmless old man, a wannabe peacemaker who has lost touch. But he is as single-minded as ever, even in his old age, and he spends the second season analysing the weakness of others, and then using those weaknesses for his own gain.

This opportunistic streak extends to the entire solar system of vapid and cruel characters in the second season. Tanya is exploited for her deep loneliness, and her own desire to exploit others stops her from realising the danger she’s in until too late. Lucia and Mia, the strongest-hearted characters of the second season, all things told, come into themselves as creatures who know how to get what they want, and what they have to do to get those things. No honour among thieves, and no values but the shifting goalpost of immorality, which reduces the world to a series of people to fuck over, and be fucked over by.

And for what? The striking thing about The White Lotus is how little this all means. All that suffering, all that exploitation, and the only prize at the end is a consolation prize. It’s not for nothing that each season’s murder turns out to be a whimper, rather than a bang. In the first season, Armond dies after a feces-based prank goes pathetically wrong, running himself into a blade. And in the second season, Tanya manages to (somewhat) extricate herself from a conspiracy to murder her, gun blazing, only to die thanks to an ungainly fall.

Checks out. If what marks the upper class is their fixation on the pointless, the too-much, then of course their fates are pointless too. Even those who win don’t win much. And those who lose – well, they lose hard, falling backwards into the den of conniving players that they have tried and failed to connive.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In defence of platonic romance

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

How to give your new year’s resolutions more meaning

How to give your new year’s resolutions more meaning

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY John Neil 21 DEC 2022

It’s that time of year again. For many of us the New Year is a time to make our annual resolutions.

For others it’s a time to briefly toy with the idea of making a resolution or two but never commit. And for others, depending on how badly the previous evening’s events transpired, the New Year’s Day hangover inspires at least one resolution – to never ever drink again.

Unfortunately, the majority of people don’t stick to their resolutions. Only 4-10% of people report following through on the resolutions they set at the beginning of the year (I wonder whether this figure includes those people that sarcastically claim that they have only one New Year resolution – to not make any New Year’s resolutions?).

The majority of resolutions fail because, well, we’re human beings. There are at least three factors behind this:

1. We overestimate the power of ‘will power.’ Often linked to adjacent concepts like resilience and impulse inhibition, the long-standing belief in psychology is that will power is a finite resource and people have varying reservoirs of it to draw on. The belief was that by bolstering our will power we’re better able to attain our goals and, by implication, those that don’t achieve their goals lack willpower. Unfortunately, it’s more complicated than that. Our ability to maintain choices and attain goals is as much about situational context, genetics, and socio-economic standing as it is about individual psychological traits.

2. As a result, any significant behaviour change requires long standing practice, environmental changes and thoughtfully designed behavioural cues in order to create pathways of reinforcement in order to form new habits. In short, even the simplest resolutions require habitual practice.

3. Most resolutions are goal focussed – stop smoking, lose weight – and for that reason they take on an instrumental importance, meaning they focus exclusively on achieving an end state or outcome. With the high level of difficulty in achieving these outcomes resolutions can become self-defeating – the end becomes the goal rather than a focus on the motivating reason that inspired the goal.

That’s not to say that New Year’s resolutions are a bad thing. We are hard-wired to demarcate life into phases. Birthdays, seasons, events, and the change of year are all relatively arbitrary events but are full of symbolic significance. They are moments that matter because we invest these occasions with meaning.

New Year’s resolutions at their best can provide a much-needed pause in the busyness of life to reflect and reassess what’s important to us.

So, as you pause and reflect on the year ahead, consider taking a different path when thinking about setting resolutions. Rather than listing goals, think instead about the qualities you’d like to cultivate in the year ahead. What qualities for you express the best aspects of a life well lived? Which of those would you choose to have more of in your life?

Known as virtues – those behaviours, skills or mindsets that are worthy to be regarded as features of living a good life. Wisdom, justice, and courage were on Aristotle’s shortlist.

Rather than setting goals like read more books or spend less time on my phone – think instead of the quality you are calling more of into your world – like being curious.

There are no limits or targets to being curious, there’s simply a conscious reflection which may lead to some different choices or new experiences.

Curiosity might lead you to pick up a book rather than slump on the couch in front of Netflix or it may prompt you to choose an interesting documentary about a topic you always wanted to know more on.

Being curious this year might also benefit your relationships. Being curious involves behaviours like asking more questions, seeking out different points of views and perspectives and being more open to opinions and beliefs that are different to the ones you hold. Practicing this virtue may lead to new and unexpected connections, making new friendships or forging even stronger relationships. It may even reduce conflict by helping you to be less triggered when confronted with views that are contrary to our own.

Being curious may also help with your lifestyle and eating habits. Rather than resolving to lose weight, be curious about trying different foods which may inspire some different meal choices from those that you might already know. By being curious you may be intrigued to occasionally switch out some of your habitual choices by actively seeking out different or healthier alternatives.

However, there’s no guarantee that being curious might not also lead you to consume a wider variety of chocolate or spend even more time on your phone as you may seek out even more information and distractions. That’s the challenge with cultivating qualities or virtues; you’ll need practical wisdom, as Aristotle calls it. It’s about finding the best balance between the virtue and its corresponding vices.

Rather than focus on resolutions as goals and outcomes – often with arbitrary measures of success like read more, rest more, learn another language – focus instead on the ‘why’ behind the quality you are wanting to cultivate. Research shows that being purposive and intentional helps people maintain their motivation and achieve the goals they set.

As you reflect on the year ahead take some time to think about those qualities you could do with a little more of. In fact, why wait for the New Year? I’m going to start today by practicing more gratitude. There’s no time like the present.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer, READ

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

Big thinker

Relationships

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why hard conversations matter

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

“I’m sorry *if* I offended you”: How to apologise better in an emotionally avoidant world

“I’m sorry *if* I offended you”: How to apologise better in an emotionally avoidant world

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Sarah Wilson 8 DEC 2022

I’ve been wondering if we need to have a better look at the way we say sorry.

We live in a highly binary and individualistic world that struggles to repent well. Yet we are increasingly aware of – and flummoxed by – bad faith efforts at the gesture.

Witness the fallout from former Prime Minister Scott Morrisons’ baffling response speech to being censured last week in which he refused to apologise to the nation. I reckon we ache to do better; we want true healing.

We could start with looking at the way we so often insist on whacking the Almighty Absolving Qualifier “if” when we issue an “I’m sorry”. I’m sorry if you’re offended/upset/angry. We go and plug one in where a perfectly good “that” would do a far better job.

But an “if” negates any repentant intent. Actually, worse. It gaslights. It puts up for dispute whether the hurt or offence is actually being felt and whether it is legitimate. Attention switches to the victim’s authenticity and their right to feel injured. Did you actually get hurt? Hmmm….

Things get even more disconcerting when the quasi-apologiser thinks they have done something gallant with their qualified “I’m sorry”. And will gaslight you again if you pull them up on the flimsiness of it. What, so you can’t even accept an apology!

I had a rich, senior businessmen do the if-sorry job on me recently. “I’m sorry if you’re angry,” he said in a really rather small human way. Rather than standing there miffed, I replied, “Great! Yep, you definitely fucked up. And so I’m definitely and rightly angry. Now that’s established, sure, I’ll take on that you’d like to repent.”

I heard a well-known doctor on the radio the other morning very consciously (it seemed) drop the if from the equation when he had to apologise for making remarks about a minority group (in error) in a previous broadcast. “I’m sorry I said those things. I was wrong. I’m not going to justify myself. There are no excuses. I was in the wrong,” he said. It was a good, textbook apology and he probably wouldn’t land in trouble for it.

But, and it immediately begs, is that the point of an apology?

For the wrongdoer to stay out of trouble? For them to neatly right a wrong by going through a small moment of awkward, vulnerable exposure?

What about the victim? Where do they sit in apologies?

I recall listening to a radio discussion where all this was dissected. The point that grabbed me at the time was this: In our culture, the responsibility of ensuring that an apology is effective in bringing closure to a conflict mostly rests on the victim, the person being apologised to. No matter the calibre of the apology, it’s up to the person who has been wronged to be all “that’s ok, we’re sweet” about things. They are effectively responsible for making the perpetrator feel OK in their awkward vulnerable moment. (And to keep the pain shortlived.)

And so a successful apology rests in the victim’s readiness to forgive.

Which is all the wrong way around. At an individual-to-individual level it’s cheap grace. The wrongdoer gets absolved with so little accountability involved.

At a macro level, say with injuries like racism or sexism, we can see the setup is about a minority class forgiving, or bowing once again, to the powerful.

I managed to find the expert who’d led the discussion – Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, a New York-based Rabbi and scholar who’s written a book on the matter, On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World, a title that says it all, right?

Ruttenberg argues we are doing apologies inadequately and in a way that fails to repair the damage done precisely because we privilege forgiveness over repentance.

So how to apologise like you mean it

Drawing on the 12th Century philosopher Maimonides, Ruttenberg sets out five steps to a proper apology.

1. Confession

The wrongdoer fully owns that they did something wrong. There’s to be no blabbing of great intentions, or how “circumstances” conspired; no “if” qualifiers. You did harm, own it! Ideally, she says, the confession is done publicly.

2. Start to Change

Next, you the work to educate yourself, get therapy etc. Like, demonstrate you’re in the process of shifting your ways. You’re talk and trousers!

3. Make amends

But do so with the victim’s needs in mind. What would make them feel like some kind of repair was happening? Cash? Donate to a charity they care about?

4. OK, now we get to the apology!

The point of having the apology sitting right down at Step 4 is so that by the time the words “I’m sorry” are uttered, we, as the perpetrator, are engaged and own things. The responsibility is firmly with us, not the victim. By this late stage in the repenting process we are alive to how the victim felt and genuinely want them to feel seen. It’s not a ticking of a box kinda thing. Plus, we’ve taken the responsibility for bringing about closure, or healing, out of the victim’s hands.

5. Don’t do it again

OK, so this is a critical final step. But there’s a much better chance the injury won’t be repeated if the person who did the harm has complete the preceding four steps, according to Ruttenberg and Maimonides.

Does forgiveness have to happen?

I went and read some related essays by Rabbi Ruttenberg just now. The other point that she makes is that whether or not the victim forgives the perpetrator is moot. When you apologise like you mean it (as per the five steps), I guestimate that 90 per cent of the healing required for closure has been done by the perpetrator. And it happens regardless of whether the harmed party forgives, because the harm-doer sat in the issue and committed to change. The spiritual or emotional or psychological shift has already occurred.

I should think that, looking at it from a victim-centric perspective, this opened space allows the harmed party to feel more comfortable to forgive, should they choose to.

It’s a win-win, regardless of whether the aggrieved waves the forgiveness stick.

(The Rabbi notes that in Judaism, as opposed to Christianity, there is no compulsion for the harmed party to forgive.)

What *if* we offend or harm unintentionally?

I was presented with the above ethical quandary while writing this. Someone on social media commented that she’d wanted to approach me recently but felt she couldn’t because she had two kids in tow at the time. She figured I’d judge her for being a “procreator” given my climate activism work and anti-consumption stance. It was an unfortunate assumption. I had only last week written about how bringing population growth into the climate crisis blame-fest is wrong, ethically and factually (it’s not how many we are, it’s how we live).

Of course, her self-conscious pain was real. But did I need to repent if I’d done nothing wrong, and certainly not intentionally (indeed, I’d not acted, in bad faith or otherwise).

I decided there was still a very good opportunity to switch out an “if” for a “that”. I replied: “I’m sorry that you felt….”. And I was. I didn’t want her to have that impression of judgement from another, nor to feel so self-conscious. I was sorry in the broad sense of feeling bad for her. Feeling sorry can be a sense of tapping into a collective regret for the way things are, even if you are not directly responsible.

The real opportunity here was to take on responsibility for healing any hurt, and to speed it up. If I’d listed out and justified why this person was mistaken (wrong) in feeling as she did, I’d have also missed an opportunity to be raw and open to the broader pain of the human condition.

Doing good apology is essentially an act in correctly apportioning the tasks required to get the outcome that we are all after, which, for most adults, is growth, intimacy and expansion. Ruttenberg makes the point that some indigenous cultures work to this (more mature) style of repentance (as opposed to cheap grace), as well as various radical restorative justice movements. I note that the authors and elders who contributed to the Uluru Statement from the Heart often remind us that the document is an invitation to all Australians to grow into our next era.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn and feminism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

BY Sarah Wilson

Sarah Wilson is a multi-New York Times and Amazon best-selling author, podcaster, international keynote speaker, philanthropist and climate change advisor. Sarah is known globally for founding the I Quit Sugar movement – a digital wellness program and 13 award-winning books that sell in 52 countries – which saw millions around the world transform their health. In 2022 Sarah sold the business and gave everything to charity. Sarah is an experienced journalist and broadcaster. She was previously the editor of Cosmopolitan Australia at age 29; host of Masterchef Australia; was a News Corp journalist and columnist; and has hosted ABC’s Compass, Ten’s The Project and more. She is also a regular commentator on news and current affairs programs in Australia, the US and UK.

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Amal Awad 25 NOV 2022

While ratings systems may encourage good behaviour on the part of the provider and recipient, it’s a hungry business model that is both anxiety-inducing and untrustworthy.

In Seth MacFarlane’s off-beat homage to Star Trek, The Orville, the increasingly earnest show becomes a series of cautionary tales. In one episode, Majority Rules, MacFarlane signals the dangers of the real world mirroring the online one. The crew of the Orville attempt to rescue a couple of imprisoned anthropologists from an Earth-like planet, where justice is meted out based on a system of public votes. In deep trouble, the public will determine their innocence with a ‘thumbs-up’ or ‘thumbs-down’.

I didn’t love the show, but Majority Rules lingers in my mind because even though determining a person’s freedom by public votes seems ludicrous, isn’t this happening daily online already, to varying degrees of severity?

There is, of course, the modern-day equivalent of the stocks. But instead of passers-by throwing fruit and jeering, people find ways to do it in 140 characters or less, hashtags optional.

But seemingly more innocuous judgments are made elsewhere, and they affect how we live, work and engage with others. When you consider the services and experiences that make up your daily life, how many of them involve ratings? Businesses rely on reviews from Google, Yelp, Trip Advisor and so on, as do we as consumers.

And of course, your transport and food delivery apps depend on them. The meal you ordered through a delivery app arrived soggy and not at all like it looked in the photo? Blame the rider who didn’t pedal fast enough, bypass the restaurant. Your food was terrible and the low-paid delivery rider is the low-hanging fruit. They get one star. Hated the music your Uber driver was playing? Give them a poor rating – though you should know, with Uber they can give you one back.

In November this year, it was reported that a study from the University of Bristol and University of Oxford found seven out of 10 gig economy workers were in a constant state of worry about negative reviews and the impact they would have on their livelihood. The lead author and sociologist, Dr Alex Wood, Lecturer in Human Resource Management and Future of Work at Bristol, noted: “It was shocking how workers expressed continuous worry about the potential consequences of receiving a single bad rating from an unfair or malevolent client, and how this could leave them unable to continue making a living.”

This anxiety over ratings is understandable. It’s not that criticism is a fresh concept (in the arts world, we are constantly subjected to review). But in the gig economy, not only can customer-generated scores sink or boost workers’ reputations, they culminate in an advertising and rewards system. The better you’re rated, the more accolades you receive, often in the form of badges that signal that you are a superstar. It’s a clever marketing tactic, because as consumers we follow the high ratings, but it’s also a way to encourage good behaviour all round because often apps rate both provider and consumer.

Ratings systems are surveillance and compliance systems, a very public message board, which mostly empower the consumer. But these ratings can also be used to falsely entice us.

Years ago, I employed the services of transcribers on a gig website. Despite having a catchy price point, the cost of the service, quite rightly, rose according to the needs of the job. And yet, the work was not done to a reasonable standard. I chose not to leave negative reviews, but the service providers pushed me to so I relented and gave them four out of five stars. I understood: they were trying to make a living. Then they sent me messages asking (borderline haranguing) me to change my review to a perfect score.

They were jockeying for work but cutting corners then demanding positive reviews. I gave in, feeling guilty, knowing that they were boosting their reliability to secure more work they didn’t seem capable of actually completing.

Meanwhile, try leaving an honest review on AirBnB, and you will understand why so many places are given rave reviews but fall short. No one wants to tell the truth when they are being judged back.

What a circular mess.

How can we trust ratings systems like this? Can scores be trusted given how freely, and sometimes anonymously, they can be applied? Meanwhile, even though ratings systems can be a useful barometer of a service provider’s reliability or competence, they may also be completely false endorsements. Increasingly, we are being warned about fake reviews, which set out to uplift or destroy a business. It pays to read comments carefully rather than rely on the rating itself.

We are increasingly being taught to assess every service or experience, and it is not a thorough, or necessarily fair, feedback system for either party to a transaction.