A new guide for SME's to connect with purpose

A new guide for SME’s to connect with purpose

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 27 MAY 2020

Purpose, values and principles are the bedrock of every thriving organisation. With many facing a reset right now, we’ve released a guide to help small to medium sized businesses create a road map for good decisions and robust culture.

In the world of architecture, even the most magnificent building is only as strong as its foundations. The same can be said for organisations. In these times of constant change, a strong ethical culture is essential to achieving superior, long-term performance – driving behaviour, innovation, and every decision from hiring, through to partnerships and customer service.

The foundations for a high-performance culture are made up of three principal components: Purpose, Values and Principles.

Each is necessary. Each plays a specific role. Each complements the other to make a stable foundation for the whole. Together, they make up what we call an Ethics Framework.

PURPOSE (WHY) – An organisation’s reason for being.

Purpose explains the WHY; it is the reason an organisation exists and what it was set up to do or achieve. It’s a defining expression of what your organisation stands for in the world and why it matters.

VALUES (WHAT) – What is good.

Values shape the WHAT; they are the things that an organisation believes are good and worth pursuing. Values guide actions, activities and behaviours within an organisations by identifying what is of merit.

PRINCIPLES (HOW) – What is right.

Principles determine the HOW; helping to guide how an organisation obtains the things it thinks are good. If Values tell an organisation what to pursue, Principles tell them how they should go about getting those things.

The Ethics Centre has spent the past thirty years helping organisations to build and strengthen their ethical foundations. In many cases, we have been able to work directly with organisations. However, not every organisation has either the time or the funds needed to invest in specialist advice.

So, the Centre was pleased to accept a grant from The Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s Community Benefit Fund for the purpose of creating a ‘DIY Guide’ for ethics frameworks – with a special focus on the needs of small to medium-sized businesses. It goes beyond broad theory to offer practical, step-by-step guidance to anyone wanting to define and apply their own Purpose, Values and Principles.

The publication of this guide comes at an especially important time. The current pandemic is testing organisations as never before.

Indeed, COVID-19 is every bit as dangerous as an earthquake – except, in this case, it is the ethical foundations of organisations that will determine whether they stand or fall. In a time of crisis, weak foundations are susceptible to crumble, opening up an organisation to the risk it will make ‘bad’ decisions that will ultimately cost it dearly.

The Ethics Centre believes that prevention is better than cure. Our hope is that the practical guidance offered by this guide will provide owners and managers with the tools they need to build stronger, better businesses.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Capitalism is global, but is it ethical?

READ

Society + Culture

6 dangerous ideas from FODI 2024

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 19 MAY 2020

If multinational tech platforms paid more tax on the revenues they made in Australia, would they be in a better moral position to resist government attempts to force them to pay a ‘license fee’ to news media?

This article was first published by Crikey, in their weekly Ask the Ethicist column featuring Dr Simon Longstaff.

There are a couple of ways to look at this question – one as a matter of principle, the other through the lens of prudence. In terms of principle, I think that we should treat separately the issues of tax and the proposed ‘licence fee’. This is because each issue rests on its own distinct ethical foundations.

In the case of tax, all citizens (including corporate citizens) have an obligation to contribute to the cost of funding the public goods provided by the state. For example, a company like Google shares in the benefits of a society that is healthy, well educated, peaceful and effectively governed under the rule of law. All who draw on and benefit from such public goods should contribute to the cost of their generation and maintenance.

Instinctively, most citizens believe that we should each pay our ‘fair share’ of tax. However, that belief is at odds with the fact that our formal obligation is not to pay a fair amount of tax but, instead, to pay only the amount of tax due to be paid as defined by law. Most of us don’t have much choice about how we discharge this formal obligation – as our taxes are automatically remitted to the Australian taxation Office (ATO) by our employers.

However, most corporations, including Google, have considerable latitude when calculating the tax they think due. For example, corporations have a clear choice about the extent to which they move right to the edge of what the law allows: ‘avoiding’ (which is legal) but not ‘evading’ (which is illegal) tax obligations that, to an ordinary person, might seem to be due.

It is this approach to ‘tax planning’ that allows Google to earn revenue, in Australia, of $4.3B yet only pay tax of $100M. Google has a perfectly rational argument about how this can the case – and relies on the fact that it should only pay tax that is legally due.

However, as is the case with other multinational corporations who make similar calculations, Google’s position fails the ‘pub test’ in that it seems to be unfair? Why? Because it seems inherently improbable (and improper) that such massive local revenue should flow offshore to benefit people who contribute nothing to maintain the society that has made possible such a financial windfall.

The issue of Google paying a ‘licence fee’ to the creators of news content is somewhat different. In general, you’d think it a reasonable expectation that a company pay for the inputs it draws on to make a profit. After all, businesses pay for labour inputs (wages), for financial inputs (interest and dividends), for material inputs (cash outlays), etc. So, why not pay for content that is derived from other sources?

Of course, what’s good for the ‘goose’ should be good for the ‘gander’. Companies like News Corporation and Nine should also be asked if they pay for all of the inputs that they draw on to make a profit? For example, do they pay for all published opinion pieces, or for the interviews they conduct, etc.? However, in general, it seems reasonable to expect that Google (and other companies) should pay for what they derive from others.

Of course, Google does not agree – and is especially opposed to Australian proposals because, if adopted, they will set a precedent that other countries are likely to follow. It is this consideration that leads us to look at the issue through the lens of prudence.

Governments (of all political hues) are especially attentive to the demands of the media. What NewsCorp and Co. want, they usually get … unless opposed by the one force that wields even greater influence over the judgement of politicians – the force of public opinion. So, if Google wishes to prevent or limit the levying of a ‘licence fee’, its most potent ally might have been the Australian public.

However, the electorate is unlikely to back the interests of a company that is perceived not to back the interests of the people whose taxes provide the infrastructure on which Google depends for the enrichment of its overseas owners.

This is where principle and prudence align. Google (and other multinational corporations) should pay taxes that amount to a fair contribution to the maintenance of public goods. Had it done so, then Google might have many more friends who might stand beside it in its battle with other powerful corporations like NewsCorp and Nine.

I am not sure if arguments from principle or prudence will really carry much weight. Perhaps the situation needs to be expressed in the language of financial self-interest. Compared to a licence fee (which might be as high as $1B per annum), would a less aggressive approach tax planning have have been a good investment?

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz on diversity and urban sustainability

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Understanding the nature of conflicts of interest

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

So your boss installed CCTV cameras

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Are we ready for the world to come?

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 15 MAY 2020

We are on the cusp of civilisational change driven by powerful new technologies – most notably in the areas of biotech, robotics and expert AI. The days of mass employment are soon to be over.

While there will always be work for some – and that work is likely to be extremely satisfying – there are whole swathes of the current economy where it will make increasingly little sense to employ humans. Those affected range from miners to pathologists: a cross-section of ‘blue collar’ and ‘white collar’ workers, alike in their experience of displacement.

Some people think this is a far too pessimistic view of the future. They point to a long history of technological innovation that has always led to the creation of new and better jobs – albeit after a period of adjustment.

This time, I believe, will be different. In the past, machines only ever improved as a consequence of human innovation. Not so today. Machines are now able to acquire new skills at a rate that is far faster than any human being. They are developing the capacity for self-monitoring, self-repair and self-improvement. As such, they have a latent ability to expand their reach into new niches.

This doesn’t have to be a bad thing. Working twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week in environments that no human being could tolerate, machines may liberate the latent dreams of humanity to be free from drudgery, exploitation and danger.

However, society’s ability to harvest the benefits of these new technologies crucially depends on planning and managing a just and orderly transition. In particular, we need to ensure that the benefits and burdens of innovation are equitably distributed. Otherwise, all of the benefits of technological innovation could be lost to the complaints of those who feel marginalised or abandoned. On that, history offers some chilling lessons for those willing to learn – especially when those displaced include representatives of the middle class.

COVID-19 has given us a taste of what an unjust and disorderly transition could look like. In the earliest days of the ‘lockdown’ – before governments began to put in place stabilising policy settings such as the JobKeeper payment – we all witnessed the burgeoning lines of the unemployed and wondered if we might be next.

As the immediate crisis begins to ease, Australian governments have begun to think about how to get things back to normal. Their rhetoric focuses on a ‘business-led’ return to prosperity in which everyone returns to work and economic growth funds the repayment of debts accumulated during the the pandemic.

Attempting to recreate the past is a missed opportunity at best, and an act of folly at worst. After all, why recreate the settings of the past if a radically different future is just a few years away?

In these circumstances, let’s use the disruption caused by COVID-19 to spur deeper reflection, to reorganise our society for a future very different from the pre-pandemic past. Let’s learn from earlier societies in which meaning and identity were not linked to having a job.

What kind of social, political and economic arrangements will we need to manage in a world where basic goods and services are provided by machines? Is it time to consider introducing a Universal Basic Income (UBI) for all citizens? If so, how would this be paid for?

If taxes cannot be derived from the wages of employees, where will they be found? Should governments tax the means of production? Should they require business to pay for its use of the social and natural capital (the commons) that they consume in generating private profits?

These are just a few of the most obvious questions we need to explore. I do not propose to try to answer them here, but rather, prompt a deeper and wider debate than might otherwise occur.

Old certainties are being replaced with new possibilities. This is to be welcomed. However, I think that we are only contemplating the ‘tip’ of the policy iceberg when it comes to our future. COVID-19 has given us a glimpse of the world to come. Let’s not look away.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The problem with Australian identity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

WATCH

Relationships

How to have moral courage and moral imagination

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask the ethicist: Is it ok to tell a lie if the recipient is complicit?

Ask the ethicist: Is it ok to tell a lie if the recipient is complicit?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 13 MAY 2020

My employer sent me a questionnaire designed to test if my home working environment meets basic standards. If I’d answered truthfully I would have ‘failed the test’. But what’s the point in telling the truth when I have to work at home in any case? Was it wrong to lie on the form?

This article was first published by Crikey, in their weekly Ask the Ethicist column featuring Dr Simon Longstaff.

Although this ethical issue seems to fall on you – as the person receiving the survey – it actually starts with your employer’s decision to request this information in the first place. I assume they did so in order to meet their legal obligations … and perhaps conditions set by their insurer, etc.

However, the process they activated was not designed to cope with circumstances like the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, the occupational health and safety checks they are trying to use were developed for a time when working from home was the exception – rather than the rule.

Back then, it made excellent sense to check that those opting to work from home could do so with good lighting, an ergonomic chair … and all the other requirements one would reasonably expect to find in a safe, modern office environment.

However, for the time being, millions of people have no choice but to plonk themselves down a couch or at a kitchen table or … wherever … to work as best they can.

So, let’s imagine that your home environment is not especially suited for work? Suppose you pass on this information to your employer. Do we really think that they would rush over with a well-designed desk, chair, light, etc.?

Perhaps some might do so … but in the current circumstances I doubt that this would be the response. Even if one sets aside questions of cost – are there enough new chairs, desks, computers, etc. to make good the likely deficiencies in the working arrangements of a large percentage of the active workforce? I suspect not.

Given this, I imagine that many people have decided to collude (with their employer) in a ‘white lie’. Both sides know (but will not say) that to offer an honest response would probably be an exercise in futility.

With this in mind, ‘form’ triumphs over ‘substance’ – with employees signing off on a declaration that they know not to be strictly true – but that is practically required all the same.

Now, I know that thus might seem to be a fairly minor form of deception – something to be excused because deemed to be ‘necessary’. However, I reckon that it is never a good thing to lie – and that those who plead ‘necessity’ must first do everything they can to prevent this kind of dilemma from arising in the first place.

This is because even occasional acts of dishonesty can start to warp a culture because they suggest that core values and principles can be abandoned whenever the going gets tough.

In summary: I think it was wrong to lie on the form (even if understandable). However, it would have been far better – for all – if your employer had not put you in this invidious position in the first place.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How cost cutting can come back to bite you

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A new guide for SME’s to connect with purpose

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

United Airlines shows it’s time to reframe the conversation about ethics

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Cris Parker The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

Emerging from the turbulence of COVID-19, we have the opportunity to escape the hold of our past and use moral imagination to explore a better future.

After months of living through disruption, old work habits and perceptions may no longer fit the ‘new normal’, says Michael Baur, Associate Professor in the Philosophy Department at Fordham University and an Adjunct Professor at Fordham Law School.

“There’s a very positive side to this, because it makes us realise that the seemingly obvious, natural way of operating is not so obvious anymore.” says Baur.

“It does afford us the ability to think a little bit more carefully about what we’re doing.”

A simple example may be that, after mastering virtual meetings, we realise that the regular face-to-face interstate meetings we thought to be essential are not, in fact, a necessary part of doing business. Instead of asking ‘can we do this online?’ we might now ask, ‘should we do this online, is there a good reason to do it in person?’

“It’s liberating, potentially, to be able to be thrown back and see that the seemingly natural is really not so natural and obvious after all,” says Baur.

Aspects of life previously unquestioned, such as our choices of where to live, send our kids to school or even the jobs we do, may be cast in a different light.

Speaking with Bob McCarthy, an Irish colleague, he spoke of the experience of the ‘Celtic Tigers’ during ten-year-plus period of economic growth prior to 2008. “Ireland had never experienced anything like it and our economy became the envy of the world. Of course, we lived in accordance with our new wealth and fame – two houses each, BMWs, ski holidays and buying chalets in Morzine”, says McCarthy.

Many rationalised their good fortune – ‘we’ve had it tough for so long we deserve a little luxury.’ So, when the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) crash came, it came hard. There was a 60% average fall in property prices, high unemployment, many family tragedies, house repossessions and years of debt to repay.

Bob said that the experience of crisis changed attitudes and behaviours, “Now, those of us who have been through this look at life, business, money, relationships, values, ethics through a different filter than before”.

He describes the experience of having benefitted from the pain. What had once seemed important during the times of excess are no longer important. What didn’t matter then, matters to him now. “Don’t get me wrong – not everything has changed. But for most the filter we use has changed”.

Baur says that, with the experience of COVID-19, we now have a similar opportunity to reset our aspirations, “When we were riding easy, just several weeks ago, we were in a state of deception.” He recognises that the pandemic has caused major economic shocks – perhaps even more severe than those caused by the GFC, “And now we can regroup. That seems to me a more positive, healthy way of thinking of it – that all of this wealth and expectation was not really ours to have to begin with.”

Bigger is not always better

The aftermath of the pandemic presents a good time to reassess our attitude to growth. The fact that almost all sectors of business have suffered means that there is a collective opportunity to slow down and reassess whether the purpose of business is to make more money for money’s sake, or to provide for human need.

Business is now attending to issues that were always there to be addressed – but remained largely ‘unseen’. By presenting itself as a ‘common enemy’, COVID-19 has caused us all to look up at the same time and respond to a suite of collective problems.

In many cases, our response has been an expression of human goodness, compassion and altruism. ‘Them’ has become ‘us’.

For example, Accor hotels, is opening up unused accommodation to support vulnerable people. Simon McGrath, Accor’s CEO, says, “Our doors are open,” said Accor’s McGrath “We have accommodation assets that can help people in times of need, and while the industry’s been devastated commercially, it doesn’t mean we can’t help.”

In a similar vein, UBER has partnered with the Women’s Services Network to provide 3,000 free rides to support those needing safe travel to or from shelters and domestic violence support services.

Australia was relatively unscathed by the GFC of 2008 and did not experience the large economic downturn felt elsewhere on the globe. Australia has also managed to flatten the curve and “none have been more successful than Australia and New Zealand at containing the coronavirus,” said Jonathan Rothwell, Gallup’s principal economist.

This is thanks to our strong public health system and our comprehensive testing regime, to the tracing of carriers and our strict self-isolation and physical distancing laws. We were also lucky that our geographic isolation bought us an extra 10 precious days to prepare.

However, Australia has not and will not escape the economic consequences of the pandemic – and our response to the threat it poses. So, how will we shape up when the challenge is an economic recession as opposed to a medical emergency? Will the good will and sense of common endeavour persist during the next phase of struggle? More interestingly still, will the sense of mutual obligation survive a return to posterity? Or will we resume our ‘old ways’?

Baur says an argument could be made that business and society in general did not make the most of the lessons to be learned from the GFC, more than a decade ago. Ireland’s Bob McCarthy, is of the same opinion, “We may be having an opportunity that would have been a lost opportunity from that time,” he says.

“What might be seen as a loss of opportunity, a loss of growth, in one limited respect, is really a darn good thing for everybody,” Baur says.

Echoing the same sentiment, Mike Bennetts CEO of Z Energy in New Zealand told audiences at the Trans – Tasman Business Circle that this virus has accelerated us into the future by 5 years, so “let’s make the most of it”. Our instinct is to seek comfort and confidence in the known which will mean going back to the way it was.

The challenge, now, is not only to create a new future but a better future. For that to happen we need to unleash a better version of ourselves.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Israel Folau: appeals to conscience cut both ways

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Your donation is only as good as the charity you give it to

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Sunlight Test

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Leading ethically in a crisis

Leading ethically in a crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

It is difficult to excel in the art of leadership at any time – let alone in the midst of a crisis. Yet, this is precisely when good leadership is at a premium.

Right now, we must ask: what is ‘good’ leadership and how should leaders respond to the demands placed upon them during periods of extraordinary ethical complexity?

In attempting to answer these questions, I am thrown back on my own experience of leadership – including at present. In that sense, this not a detached, objective account. Rather, it is a reflection on (and of) lived experience.

The first obligation of a leader is to see, and sense, the whole picture. This means being alive to the undercurrents of feeling and emotion flowing through the organisation, while simultaneously keeping a clear view of the evolving strategic landscape and being ‘present’ in the moment.

The good leader needs to ensure that no one affected by the crisis is either overlooked or marginalised. This is harder than it seems. When driven by the ‘lash of necessity’, it’s all too easy to favour some people because of their utility, while dismissing others as ‘dead weight’.

I have been struck by the number of times that people have said the current emergency requires them, albeit reluctantly, to be cold-hearted, brutal or even cruel. I realise that such comments do not reflect their personal inclination – but instead reflect their response to evident necessity. However, I think that ethical leaders have an obligation to challenge that tendency – not least by naming it for what it is.

This is not to say that issues of relative utility are unimportant. Nor is it the case that one should avoid difficult decisions – such as those that might lead to job losses. Rather, the leader’s job is to ensure that such decisions are not made on the basis of cold, dispassionate calculation. Instead, the leader has an obligation to ensure that the ethical weight of each decision is felt and the heft of the burden that falls from each decision is known.

The second requirement of ethical leaders is that they resist demands for a certainty they cannot or should not provide. This is easier said than done. There are some contexts in which the suspense of ‘not knowing’ can be thrilling; however, for most people operating under stress, confronting ‘the unknown’ reinforces a sense of powerlessness and is deeply unsettling.

Even so, ethical leaders should resist the temptation to offer people false certainty, no matter how much that might be desired. Instead, a good leader should be resolutely trustworthy by only claiming as ‘certain knowledge’ what is genuinely known. Otherwise, a leader’s integrity can be undermined by something as simple as a gap between what was asserted as fact and what is subsequently revealed to be true.

None of this is to suggest that people be denied glimmers of hope based on one’s best estimate. It is merely to counsel caution – especially when a delay can open up new possibilities. The recent and unexpected emergence of the Federal Government’s JobKeeper scheme is a good example.

Leading during a crisis requires an ability to foresee a future, preferred state and then ‘backcast’ to the present when making decisions. As noted above, in the course of a crisis, many decisions will be made under the ‘lash of necessity’.

In these circumstances, people will be driven to accept the harshest treatment as a ‘necessary evil’. However, a time will come when the crisis is relegated to the past and those who remain in an organisation will want to know what justified the sacrifice – especially that made by those who fell along the way.

Telling people that it was ‘necessary’ will not be enough. Instead, those who remain will require a positive justification that goes beyond ‘mere survival’. It is in the light of that positive justification that all of the preceding decisions need to be evaluated. So, leaders need to ask themselves, ‘is today’s decision going to foreclose on the future we hope to create’. In particular, will my present choice make my preferred future impossible? Will it delegitimise my future leadership?

Finally, leaders need to release themselves from the unrealistic expectation of ‘ethical perfection’. This is not to say that one should be careless in decision making. Rather, it is to recognise a fundamental truth of philosophy: that some ethical dilemmas are so perfectly balanced as to be, in principle, undecidable.

Yet, we must decide. The only reasonable standard to apply in such cases is that we are sincere in our judgement and competent in our capacity to make ethical decisions – a skill that can be learned and supported.

There are particular ethical challenges to be faced by leaders during times such as these. Critical decisions may have to be made alone. Not everything that could be said should be said. There are some options that need to be considered but not voiced – as they would cause unnecessary worry – only to remain dormant.

There are ‘gordian knots’ that may need to be cut rather than carefully unravelled over a period of time that is simply not available. There is the fact that the weaknesses in oneself (and others) will be revealed under pressure – and that unpleasant truths will need to be acknowledged and endured.

At times such as these, the things that sustain good leaders are an unshakeable sense of purpose and a solid core of personal integrity. One might protect others from the harshest of possibilities for as long as possible – but never oneself.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

No justice, no peace in healing Trump’s America

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moving work online

Moving work online

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Talya Wiseman The Ethics Centre 10 APR 2020

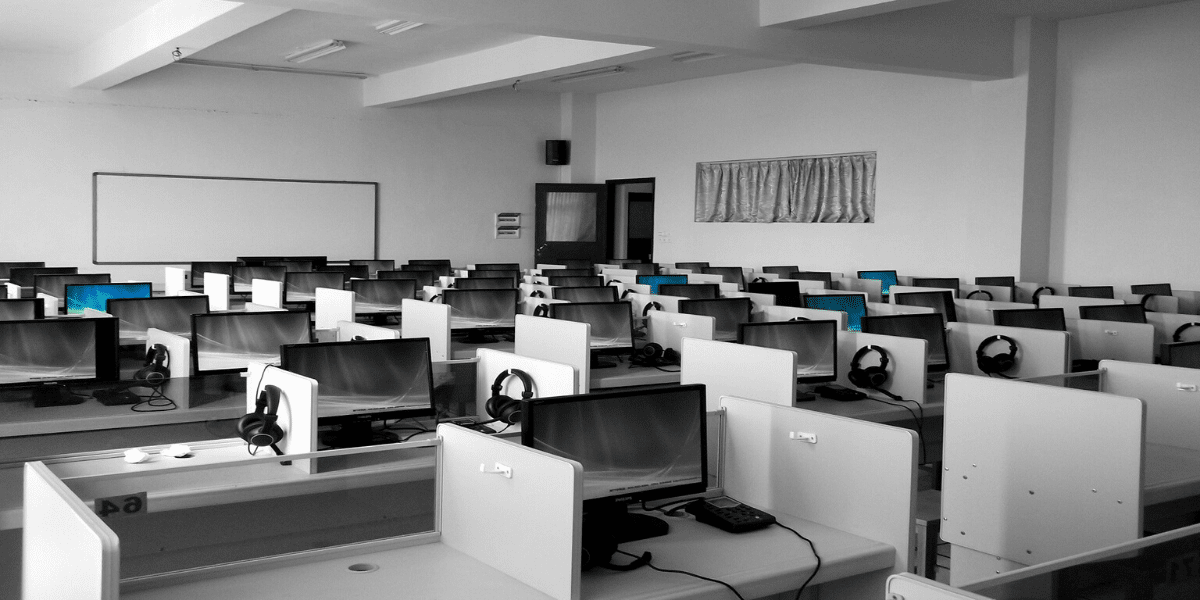

As the COVID-19 dominos continue to fall, many organisations are scrambling to rethink the way they work. These changes are happening in real time; on a scale both unprecedented and unpredicted.

The last pandemic of this nature, the Spanish Flu, occurred 100 years ago – well before anyone had dreamed up the internet, computers and video conferencing. In 2020, advances in technology, such as international flights, have allowed this virus to spread at a much faster rate. However, they have also afforded many organisations the opportunity to pivot their operations online.

Schools and universities have, for the most part, managed this at an incredibly fast pace. With barely any notice, teachers have become adept at using online delivery platforms and are coming up with new ways to engage their students online.

Students are able to continue their same classes via platforms like Zoom or Microsoft Teams; all the while knowing that the rest of their class is right there, learning alongside them.

Now that all but essential workers are urged to stay at home, ideas about working environments have also been forced to alter at an unusually rapid pace. For example, workplaces and teams have begun to adapt to meeting online. A popular meme doing the rounds at the moment depicts a scenario 40 years from now when a grandchild asks their grandparent with wonder “Go to work? You used to actually GO to work?”

It is incredible to see how many fundamental changes and shifts in thinking have occurred in such a short space of time. We simply had neither the time nor the opportunity to incorporate long policy discussions, carefully timed rollout plans or trial periods. Many organisations that previously assumed they needed a common workplace are now questioning the validity of this assumption.

What happens next?

The big question is this: when all of this is over and we return to normal, what will normal look like? Will organisations revert to their old ways? Or will we have seen the value in new patterns of working? Our eyes have been opened through this experience. Our assumptions about the nature of work have been challenged. Having reorientated towards online workplaces, will it be so easy to pivot back? And will we want to?

There are certainly benefits to workplaces accepting remote working as a viable option. Parents and carers, who previously struggled to convince their employers that they could effectively work from home, will likely find this argument much easier to make. If people have been able to fulfill their work duties in these most trying times, clearly it will be easier for them to continue to do so when it is an option they are choosing.

The stigma of working from home has rapidly been removed. It should no longer be seen as the ‘lesser’ option compared to attending an office. Organisations are finding innovative ways to ensure staff feel supported while working from home; while also maintaining expectations of staff – wherever they happen to be located.

The role of the physical workplace

However, there is a risk in realising just how easy it is to do things online. The role that work plays for individuals is much more than just providing an income. Work is also about fulfilment; it is about social interaction. The best initiatives can arise from bouncing ideas around with colleagues. Families can laugh together at the dinner table when sharing work stories and funny moments that occurred at the office. Colleagues can celebrate each other’s success and commiserate together when things don’t go as planned. Work is about so much more than ‘work.’

One of our principles, here at The Ethics Centre, is to “know your world and know yourself”. We believe in the importance of questioning who we are and being conscious of what we do. If the nature of work is fundamentally to change, we must recognise what we are giving up, as well as the opportunities that may arise. Just because we were rushed into this new reality doesn’t mean we can’t carefully consider the best way to move on from it.

Let’s not just fall back into old patterns. Let’s use this as an opportunity for questioning and for finding a better ‘normal’. That might well be a workplace that embraces flexible arrangements and is open to non-traditional office environments, while at the same time never losing touch with deeply human moments and interactions.

Perhaps we will realise that work, regardless of industry, is about purpose, fulfilment and human interaction.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Economic reform must start with ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Akrasia

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to improve your organisation’s ethical decision-making

BY Talya Wiseman

is an experienced educator who has worked extensively in both the formal and experiential education space. At The Ethics Centre, Talya is the Educational Program Manager creating innovative, engaging and quality ethics-focused education

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Dennis Gentilin 9 APR 2020

Crises, especially as momentous as this one, have a habit of exposing leaders. At worst, they expose incompetence and self-interest. At best, they reveal courage, resilience and deep concern for others. It is the latter that is the hallmark of ethical leadership.

Make no mistake, these are challenging times. There are potentially some dark days ahead. Humanity has not faced a perilous situation of this magnitude in my lifetime.

Unfortunately, ethical leadership is not something that can be ‘switched’ on at will. In trying times, one cannot simply dust off the ethical leadership manual and, like a chameleon, transform one’s approach. The reason for this is that ethical leadership is honed through many years of practice.

Ethics is a long game

This is not a new idea. Aristotle described ethical virtue as a “hexis” – a state or disposition – that is shaped by our habits. We come to be ethical by acting ethically, consistently being guided by an ethical framework when making choices, regardless of how difficult this might be given the prevailing circumstances. This is what it means to be a person with integrity.

For this reason the COVID-19 pandemic will (and in some cases already has) reveal what leaders believe to be good (their values) and right (their principles). More importantly, it will reveal how committed they are to their ethical core. Those who have failed to make ethical practice a daily habit will find it difficult. They may already have stumbled or are perhaps struggling to win the trust of sceptical followers. For those who have made integrity central to their leadership, the turbulent waters will be somewhat easier to navigate. Making the ethical choice will come more instinctively.

There is also the possibility that ethical leadership will emerge in the current crisis from the most unlikely of places. People whom we may have thought were not cut out to deal with a crisis or a thrust into a position of leadership will rise to the occasion. Perversely, moments like these, instead of paralysing leaders, can provide greater clarity on what is the ‘right’ thing to do. The path one must take, although rocky, lights up and is clearly signed. A leader comes into their own.

Ethical leadership, not perfection

All this being said, one thing that we should not (and cannot) expect is ethical perfection. In situations like these where there are excruciating trade-offs associated with many decisions, ethical perfection cannot be defined. The available choices are evenly balanced, providing a myriad of possible outcomes that all have considerable merit. It would therefore be preposterous to think that any leader in these circumstances, no matter how ethical, will get everything ‘right’. We should respect those who are being called upon to make extraordinarily difficult decisions, with imperfect information, in a highly dynamic environment.

However, there are some minimal expectations we should expect from our leaders. We should expect a degree of candour and honesty, accepting that in some cases full transparency will do more harm than good. We should expect that the safety of people – particularly the most vulnerable – is prioritised, accepting that there will be unfortunate loss of life. Above all, we should expect leaders to act with sincerity, rely on the best available evidence and display ethical competence. ‘Winging it’, ‘intuition’ and ‘common sense’ are not enough.

We all have a role to play

We should also understand that ethical leadership is not reserved for those who sit highest in the hierarchy, especially in unprecedented moments like these. This is something that can’t be underestimated. Ethical leadership will need to emerge at every level of society if we are to find a way through what will be some very difficult weeks and months ahead. Do not discount our essential role as ethical citizens.

Jon Haidt, a professor of ethical leadership at the Stern School of Business at NYU, talks about how morality “blinds and binds”. It can evoke the passions and bind people around a common cause. However, in doing so, it can breed dogmatism and drive us into our ideological camps, blinding us to our common humanity.

For the first time in a while, the coronavirus has created a present and common cause that all of humanity can bind to. It will test our leaders and in doing so reveal those who make ethics more than a word in their by-line. It will produce benevolent and heroic acts among citizens that extreme circumstances like these so often educe. And hopefully, by producing a cause we can all be bound by, it will dampen some of the tribalism and self-interest that has been an unfortunate feature of some sectors of our society in recent times.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Between frenzy and despair: navigating our new political era

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

BY Dennis Gentilin

Dennis Gentilin is an Adjunct Fellow at Macquarie University and currently works in Deloitte’s Risk Advisory practice.

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Michelle Bloom The Ethics Centre 6 APR 2020

COVID-19 has created a cascade of unprecedented changes to how we work, live and interact.

With many organisations moving online, managing restructures, significant job loss and transformation of existing roles and responsibilities, leaders need to be consciously aware of the impact of stress on individual and team performance.

Certain aspects of organisational behaviour can trigger threat reactions in people that impede their effectiveness and limit their ability to contribute to the success of the team. Research in neuroscience can inform our response to such situations, as the neural functioning of individuals within the workplace underlies the social nature of high performance.

What happens to us in stressful environments

The brain is a social organ. Studies by UCLA have found that when we feel excluded from play or rewards, our brains trigger a response from the same neural regions associated with the distress that comes with physical pain. This neurophysiological link has been explained as evolutionary, a developmental hangover from the dependency of infancy. As UCLA neuroscientist Matthew Liebermann puts it, “To a mammal, being socially connected to caregivers is necessary for survival”.

This neurological response has a number of implications for business and leaders navigating this current crisis – especially in regards to remote working and communicating organisational changes driven by COVID-19.

A person who feels their position and work to be valued, by their leaders, solely as an economic and rational transaction (labour for money) will likely feel betrayed, unrecognised and disengaged.

Research shows that each time a person feels like this, it is physiologically and psychologically analogous to a ‘blow to the head’ and is processed in the brain in the same way as physical pain. Naturally, our conscious selves rationalise the discomfort, but if this situation is chronic and ongoing, it is more likely that employees will begin to desensitise in self-protection. They will effectively push the discomfort away, so as to not feel it consciously. This shutting down of large parts of our response pathways disables us, making high-performance impossible.

Many studies, including Paul MacLean’s infamous “Triune Brain” theory, look at how fear responses negatively impact the quality of mental functioning. In more mild circumstances, the emotional centres associated with the limbic brain will interfere with the circuitry of the logical neo-cortex. In extreme circumstances, our ‘fight, flight, freeze’ response gets triggered, creating a chemical reaction that entirely hijacks the brain’s emotional centre, the amygdala, making logical thinking impossible.

However you conceptualise it, high emotion is disastrous for the adaptive thinking required for complex problems – so critical for ethical decision making.

Physiologically, the threat response ties up glucose and oxygen, as lower areas of the brain, more intimately concerned with survival, take precedence over higher centres. In threat situations, these resources are withheld from working memory, impairing the processing of new information or ideas, and slowing analytic thinking, creativity and problem solving.

Addressing the needs of the individual and the organisation

We’ve all heard that adults are poor learners, fundamentally intractable, or that their natural response to change is resistance. While elements of these statements are true, what is also true is that the adult brain continues to be highly plastic; albeit not as much as children or infants. That means that not only can behaviours change, but that the neural networks that underlie all thought and behaviour are in fact changing every day.

To increase the chances of your business being high-performing, David Rock’s SCARF Model, as outlined in his paper “SCARF: A Brain-Based Model for Collaborating with and Influencing Others,” suggests that leaders should look at how the organisation deals with the following aspects of individual functioning in the collective social system.

1. Certainty

Our brains are wired to crave certainty. This desire is underpinned by neural circuits that register unexpected events as gaps or errors. Because an assumed pattern is no longer functioning as it should, it is registered as a threat.

Think about how you respond when the car in front slams on the brakes. Normally, we can do multiple things at the same time when we drive – hold a conversation, listen to music, monitor what’s going on around us, think about the shopping list – but faced with a potential accident, your working memory is diminished. All other activities and thoughts must cease as you shift full attention to the potential threat ahead.

Some uncertainty can be intriguing and enjoyable; too much leads to panic and bad decisions. For many people right now, the levels of uncertainty – combined with imminent health and employment risks – will be triggering this aspect of the ‘fight or flight’ response. This impedes their capacity to access creative thinking and good decision making.

Of course, certainty is an illusion. However, people need a semblance of certainty in order to perform. Leaders need to build confidence in their people so they, in turn, can trust in individual and collective capability to work through whatever comes. Keeping a clear and regular stream of communication around how decisions are being made increases trust and promotes engagement. Chunking larger problems into shorter time frames also helps people feel more certain.

2. Status

As humans, our relative status within social systems matters. This is the basis for all competition, social hierarchy, and, conversely, much social unrest. Many organisations have processes and practices that threaten people’s status. Hierarchy reinforces a notion of ‘greater than’ and ‘less than’, while performance appraisals and coaching generally place one person in the position of being more knowledgeable, capable and powerful than the other. Unless these interactions are carefully considered and thoughtfully executed, they will feel threatening to an individual’s status.

Actions that enhance status include private, as well as public, recognition. In addition, the quality of interactions from leaders with their people can raise the self-status of those who sit lower in the hierarchy. Therefore, one of the most important (albeit intangible) skills of a leadership team is their capacity to interact with others in a respectful and status-enhancing way.

With staff working digitally, and from home, leaders need to innovate and find new ways to show this recognition. This will make people feel seen and valued for the work they do.

3. Autonomy

When people feel they can execute their own decisions, without interference, their felt stress is lower. In a 1977 study, residents of aged care facilities who had more agency and decision making rights, lived longer and healthier lives. While what they were deciding about was insignificant; their autonomy was critical. In another study, franchise owners principally left corporations citing work-life balance. Once in their own business, they generally worked longer hours, for less money, and nevertheless reported better work-life balance, because they were making their own decisions.

Delegation systems, hierarchy, confusing reporting lines, moribund policy and procedure, and parochial mindsets can all contribute to less agency for individuals in businesses. Often people are not aware that they are not delegating, that they are effectively withholding decision making from others.

Lack of autonomy is also closely linked with the phenomena of people not working ‘at the right level’. When leaders find themselves working at a level of complexity lower than where they should be working, the flow on to the rest of the organisation is usually inevitable.

4. Relationships

Perceived difference is another human threat-trigger. Collaboration, trust and empathy are predicated on perceiving that the ‘other’ is from the same social group as we are. The decision of friend or foe is usually made in milliseconds.

The organisational implications for bringing groups together are profound. Forming new relationships at this time, such as buddy systems or mentor programs, need to be carefully thought through so as to minimise the potential to ‘spook the horses’. The creation of productive strategic relationships requires repetition via multiple, sequential opportunities and reinforcement through the removal of organisational impediments.

5. Fairness

Fairness is a cognitive construct that motivates people so strongly they will persist in situations that are manifestly unfavourable because they value a perceived fairness on the part of an organisation or a cause. Consider how people historically have volunteered to fight in wars that are not their own, such as the Spanish Civil War, and are prepared to die based on apparent fairness.

People not only want to avoid being unfairly discriminated against, they will also often feel uncomfortable if they find themselves being unfairly favoured by a person or a situation.

Organisationally, the implications are similar and connected to that of certainty. People will be much more accepting of decisions and processes, as fair, if they are transparent.

Fairness is also related to status in that people will feel fairly dealt with if they perceive they are respected as a person and employee. These principles are often coded as ‘natural justice’. In some ways, fairness is an amalgam of the previous four areas of concern.

What leaders need to think about

The upshot for leaders is this – when you trigger a threat response in others, you make them less effective. When you make people feel good about themselves, clearly communicate your expectations and give agency through appropriate delegations, people feel a reward response which is intrinsically engaging – something your people want more of.

In situations where threat is felt to be ongoing, people typically experience burnout. This emotional exhaustion is a result of chronic over-stimulation of the fear centres of the brain. Physiologically, high levels of adrenalin and cortisol can only be supported for so long before they start to damage the nervous system.

Where these sorts of threatening social conditions are widespread, ongoing or both, each individual’s sub-optimal reaction is reinforced by the reactions of the people around them, magnifying the pattern. This looks like ‘learned helplessness’, passivity or protective withdrawal. Sometimes it drives an aggressive pattern where individuals seek authoritarian control over whatever small part of their world they feel they can have an effect on.

Practical steps that can be taken during COVID-19

If you’re an organisation transitioning working roles or letting go of staff due to the impacts of COVID closures, ensure you are both transparent and compassionate in your communications.

Be clear and straight forward about how government policy impacts your workers, keep them informed of the decisions being made and communicate the rationale behind them, particularly when they impact others.

When communicating changes, respect for the people affected is crucial. While your decisions have economic drivers, there are very real human costs associated with the outcomes.

Relationships and connection are of heightened importance now. Take care in implementing processes to foster positive relationships between people – whether by virtual catch ups, a mentor support system, or regular virtual check ins by managers with their staff to see how they are coping and adjusting.

Tension will also be high, and any perceived difference may trigger as a threat. Leaders will need to be conscious of how relationships are managed between staff who may be actively competing for scarce resources or roles, if facing redundancies.

None of these strategies ameliorates the situation

It is the responsibility of the leaders of the transformation to monitor if what is going on in their organisation is supporting or undermining people’s performance. If performance is being undermined, it is their responsibility to raise those instances to awareness of their peers in the leadership team, to mobilise and support staff to break the prevailing patterns and to experiment with alternative approaches.

Navigating the changes ahead won’t be easy, and for many this may be the hardest professional challenge they’ve had to face given the stakes have never been so high. But careful attention to how decisions are made and communicated is critical to staff safety and wellbeing in the current climate. And that’s never been more important.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does ethical porn exist?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Feel the burn: AustralianSuper CEO applies a blowtorch to encourage progress

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Has passivity contributed to the rise of corrupt lawyers?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The dangers of being overworked and stressed out

BY Michelle Bloom

Michelle Bloom is the Director of Consulting and Leadership at The Ethics Centre. Drawing on 30 years as a consultant, clinician, and organisational development specialist, she has worked with Australia’s largest organisations in developing and delivering solutions to assess and build value-driven leaders and cultures.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 MAR 2020

One of the most difficult decisions an employer will ever have to make is whether or not to dismiss employees during an economic downturn.

Invariably, those at risk of losing their jobs are competent, hard-working and loyal. They do not deserve to be unemployed – they are simply the likely victims of circumstances.

As one employer said to me recently, “I hate the idea of having to be ruthless – but I need to sack forty to save the jobs of four hundred”. So, what are the key ethical considerations an employer might take into account?

-

Save what can be saved

There is no honour in destroying all for the sake of a few. Even the few will eventually perish in such a scenario.

-

Give reasons

Be open and truthful. Throw open the books so that people can see the proof of necessity.

-

Retain the essential

Some people are of vital importance to the life of an organisation. However, when all other things are equal, protect the most vulnerable.

-

Cut the optional

The luxuries, the ‘nice-to-haves’ should not be funded. Use income for the essential purpose of preserving jobs.

-

Treat everyone with compassion

Both those who leave and those who remain will be wounded by the decisions you make – no matter how necessary.

-

Share the pain

consider offering everybody the opportunity to work less hours, for less money, in order to save a few jobs that might otherwise be lost.

-

Seek volunteers

If sacrifices must be made, invite your colleagues to be part of the decision. Some might prefer to step down – their reasons will vary. Honour their choice.

-

Honour your promises

If you have made a specific commitment to a member of staff, then you are bound by it – even in a crisis – unless it is impossible to discharge your obligation.

-

Minimise the damage

Those who lose their jobs should not be abandoned. How can they be supported by means other than a salary?

-

Look to the future

Make sure that your organisation has a purpose that can inspire those who remain – and justify the losses suffered during the worst of times.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Finance businesses need to start using AI. But it must be done ethically

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to spot an ototoxic leader

Explainer

Relationships