Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Daniel Finlay 8 JAN 2026

As a 16-year-old, I argued with my vegan friend about the various faults in his logic: how he couldn’t possibly be healthy, how we were meant to eat animals, and all the rest. I never could have imagined how embarrassed it would make me many years later.

I wasn’t particularly familiar with veganism as a teenager, but I have always loved animals. While the fervour to prove it wrong dissipated, my knowledge and exposure to it remained very minimal, like most people’s. A little later, I briefly dated someone who was vegetarian, who inevitably but mostly passively increased my exposure and knowledge. I decided to start looking into the validity of my confident preconceptions and realised that they were either completely unfounded or just exaggerated. It wasn’t many years later when I woke up in the middle of the night and decided that I needed to change my actions.

Veganuary

Coincidentally, 2014 was the year that I began changing my lifestyle to better reflect my values – the same year that a British nonprofit began an annual challenge called Veganuary: a call for people to try eating as if they were vegan for the first month of the year. You sign up for free and are provided with daily emails for a month that include information like recipes, cookbook pages, meal plans and general advice for how to navigate the change in habits.

All of this is well and good if you’re already curious about the idea of reducing your animal consumption, but what if you’re not? Let me try and pique your curiosity.

Why you should care

You might already consider yourself someone who cares. Most people do love animals in theory. If you see an injured bird, a run-over kangaroo, or an abused dog, you’re likely to have a compassionate response. But decades of socialisation, billions of dollars in misrepresentative marketing, and the ever-increasing distance between consumers and production means it’s easier than ever to ignore how our values contradict our everyday actions.

So please indulge me by considering the following responses to common arguments for eating animals.

To begin, let’s get the practical stuff out of the way:

Where will I get my protein? We need meat/dairy/eggs to give us all the nutrients we need.

This argument is as unfounded as it is ubiquitous, and one I wasn’t immune to earlier in my life either. Unfortunately, agricultural lobbying groups are much better at getting into the minds of average consumers, otherwise it would be common knowledge that all major dietetic associations agree on the safety (and benefits) of balanced vegan diets (and all types of vegetarian diets). That’s not to demonise the health of any other kind of balanced diet – you can be perfectly healthy on a regular omnivorous diet – but the ethical argument for showing compassion to animals doesn’t require it to be healthier than eating animals, only that it’s not bad for us. The overwhelming evidence shows that it is not.

The question is not “can I?” but “how would I like to?” That’s why something like Veganuary is such a good introduction, because having the initial support to change your shopping and eating habits makes the transition much easier.

It’s too hard.

Maintaining a balanced omnivorous diet is also too hard for most Australians – doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try! Sometimes we have to do difficult things for our own good or the good of others. You will likely find though, as I did, that the hardest part of changing your lifestyle is the social aspect. People can be judgemental, defensive, aggressive, and downright cruel despite your best attempts to minimise the impact that your choices have on others. Contrastingly, changing habits can be difficult in the short term but they soon become second nature. Staple recipes are easily replaced and substituted with similar-tasting alternatives.

Okay so maybe it won’t make my life worse personally, but it’s so bad for the environment. All those almond trees and soy crops use so much water and cause deforestation. We need animals to feed everyone.

Almond water usage obsession arose initially during the early-mid 2010s Californian droughts, where the majority of the world’s almonds are grown, at a time when almond consumption was skyrocketing. I’m not going to rush to almond’s defense, as we should definitely be prioritising mass consumption of soy and oat milk instead, but if we do want to compare it to the animal-derived alternative then almond is still better, using almost half the amount of water and causing almost five times less CO2 emissions.

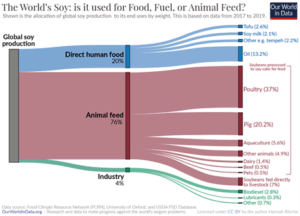

The idea that the soy used for soy milk, tofu, tempeh, etc is driving deforestation is another common myth:

“In fact, more than three-quarters (77%) of global soy is fed to livestock for meat and dairy production. Most of the rest is used for biofuels, industry, or vegetable oils. Just 7% of soy is used directly for human food products such as tofu, soy milk, edamame beans, and tempeh.”

Even further than this, the amount of land cleared for cow pastures is over 7 times that for total soy production. If you’re worried about the environment, reducing or eliminating your animal consumption is the best place to start.

I’ve heard that farming vegetables kills more animals (mice, insects, etc) than eating meat, so if we care about animals, we should really keep eating them.

As we’ve seen, most of these crops go to feeding farmed animals, which means that it is still much preferable to consume these crops ourselves, rather than producing magnitudes more to feed other animals to be killed. The same logic applies if you’re someone who would like to argue that plants have feelings, too.

If you’d like to read more about the arguments against veganism, please see here.

Starting the year right

The overarching consideration here from an ethical standpoint is to reduce unnecessary suffering. For me, this comes mainly from a consequentialist perspective. Suffering is bad, we want to see and contribute to less of it. Eating meat, dairy and eggs necessitates immense amounts of unnecessary suffering and death (even if you think killing an animal that lived a good life is okay, we cannot feed the world with that kind of production – factory farms exist to fill the demand). Therefore, we should stop contributing to that demand.

My suggestion isn’t to make a permanent change overnight, but simply to try something new. You can join millions of other people around the world who are trying out a month of reduced animal harm through Veganuary. Or maybe you’re someone who says things like “I could go vegan except I love cheese too much”. Well, use the start of this year to try being vegan except for cheese. You’ll probably find that the hardest part of doing good is taking the first uncomfortable step.

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

11 books, films and series on the ethics of wealth and power

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Standing up against discrimination

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

The Bondi massacre: A national response

The Bondi massacre: A national response

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 2 JAN 2026

What is the best response to the massacre of Jewish people at Bondi Beach? I ask that question knowing that the best response may not be the most popular.

For example, the debate about whether or not there should be a Federal Royal Commission has made it abundantly clear that people can reasonably and sincerely disagree about what should be done. The same debate has also revealed that some people have deliberately (and others inadvertently) politicised what should be a matter of broad national consensus – with the ideal response being of a kind that meets a number of core criteria. If ever there was a time to set politics aside in favour of a singular compassion for the Jewish Community and a high regard for the national (rather than partisan) interest, then this was it.

Although united in grief and anger, the Jewish Community is not of a single mind about what should now be done. Differences of opinion are to be expected. It is wrong to expect any group of people to hold a common position simply because they share aspects of identity. Furthermore, while the Jewish Community was the explicit target of the terrorists’ attack – and bore the brunt of the carnage – they are not the only Australians to have been wounded by the murderous rampage that took place on the first night of Hanukkah. The whole nation has been scarred … and now a host of other communities are left to ask, “What caused this to happen? What can be done to prevent this in the future? Who’s next?”.

Bearing all of this in mind, I have come to the conclusion that the best possible response cannot lie in a single measure. Instead, I think the whole nation will be best served by a multi-layered approach. Importantly, such an approach would see the Commonwealth Government go well beyond where it currently stands – but in a direction that, I propose, eclipses what has been called for so far.

Each element of our national response needs to be ‘fit-for-purpose’; tailored to meet a specific need. So, what are those needs? First, the Jewish Community needs answers about what caused the Bondi Massacre – and how it might have been prevented. Second, the nation needs to know if there is anything more that could have been done by our national intelligence and security services to identify and therefore prevent the terrorists from acting. Third, we all need to understand the genesis of hate-crimes (of which antisemitism is an especially virulent, but not the only, form) in Australia – and how this might be combatted in favour of resilient bonds of social cohesion that would enable us to maintain a vibrant, multicultural society in which every person can flourish, free from fear or prejudice.

The first need will be met by the proposed NSW Royal Commission that enjoys the unfettered support of the Commonwealth Government and its departments and agencies. That support needs to be offered with the whole-hearted endorsement of the Prime Minister and unwavering direction from his Cabinet. The Commonwealth should offer binding undertakings to hold to account any of its officers, including members of past and present Commonwealth governments, who are found by the Royal Commission to have contributed to the events in Bondi – either by act or omission. Under these conditions, the proposed NSW Royal Commission will be in a position to address all of the issues arising out of the specific terrorist attack of 14 December.

The second need will be met by the Richardson Review. It will be focused and completed within a relatively short period of time. Anyone who knows or who has worked with Dennis Richardson AC knows that the inquiry will be thorough and exacting. The general public may not see all that he finds and recommends – as national-security considerations will take priority for the sake of us all. However, we can trust that nothing will be overlooked.

The third need can be answered by a National Commission of Inquiry. Unlike a Royal Commission that has a defined legal form – and often seeks to find fault and punish wrongdoers – this Commission would be required to look at the deeper causes of which the Bondi Massacre is a treacherous and violent eruption. Those causes affect multiple communities – indeed, they are a cancer eating away at the soul of Australia. The Commission should have broad powers – but it should especially be enabled to convene individuals and groups from across the nation – to hear the stories of what is happening, the impact of hatred and what can be done to prevent this from metastasising into violence.

In my opinion, we should also put the lens on multiculturalism so that rather than merely celebrating the worthy characteristics of separate communities, we learn how to strengthen the bonds between them – and commit to doing so in practice.

I know that there will be some people in the community, especially the Jewish Community, who would prefer to see the Prime Minister establish a Royal Commission to investigate the scourge of antisemitism. There is something distinctive about the hatred directed at Jews – almost unfathomable given its dark persistence over millennia. However, what I have in mind would allow the Jewish experience to be given full voice – but in conditions where we see how it relates to the experience of others in the community. In itself, that will help forge common bonds – as always happens when we see ourselves reflected in the lives of others. Given the searing nature of events, a proposed Commission should prioritise its examination of antisemitism, before all else, reporting on this within twelve months of being established.

In putting forward this proposal, I sincerely believe that nothing will be lost – and much will be gained. I hope that Prime Minister Anthony Albanese might establish a Commission that embraces the whole nation – in all of its marvellous diversity – in order to find light at this terrible moment of darkness.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Schools of thought: What is education for?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

That’s not me: How deepfakes threaten our autonomy

LISTEN

Society + Culture

FODI: The In-Between

Feeling our way through tragedy

The emotions we feel in the wake of a tragedy, like the Bondi Beach shooting, are as intense as they are natural. What matters is how we act on them.

It was a typical relaxed summer Sunday evening. We had just finished dinner and I was on the couch watching TV while my wife was in the other room catching up with family over a video call. Then a wayward notification caused me to idly glance at my phone. A headline popped up on the screen, I caught my breath and switched on the news.

And in a matter of moments, the peace was shattered as the news came in that two men had opened fire on a group of people enjoying their own relaxed summer Sunday evening celebrating Hanukkah on Bondi Beach. A wave of emotions followed: horror, grief and outrage, followed by a gnawing sense of uncertainty. Were any of my friends or family there? What could drive someone to commit such an atrocity? Is anywhere safe?

These are typical emotions when confronted by sights such as these. The feelings well up from our bellies, fill our chest, overwhelm our minds. They are as primitive as they are potent. And they demand closure.

Yet emotions like these can be channelled in many different ways. Some forms of emotional closure are healthy. But other courses can end up causing more harm, either to ourselves or to others. And while it is easy to let these types of emotions consume us, it is crucial that we act on them ethically.

Horror and hope

Many creatures experience fear. It is a natural response to threat, and a potent motivator to remove ourselves from its presence. But our species is unique – as far as we know – in our ability to experience horror. Horror is also bound up with shock, disgust and dread. It is a response to the most acute violations of our humanity. The thing is, we don’t only experience horror when we are under threat, but when someone else is threatened. Underneath horror is a recognition of our shared sacred humanity and a revulsion at its desecration.

The problem is that the sense of horror triggered by an attack such as that at Bondi Beach on 14 December 2025 can change the way we see the world. In our aroused state, we become hyper vigilant to cues that might indicate future threats. And those cues will be associated with the location of the shooting, perhaps making us reluctant to go to Bondi Beach, or even causing us to fear going out in public at all.

If we allow emotion to take over, it can make the world feel less safe and other people seem more threatening.

But that response overlooks the fact that, despite the magnitude of the atrocity, this is an incredibly rare event perpetrated by only a few people. The fact that our feeling of horror is shared by millions of others around Australia and the world should serve as a reminder that the vast majority of us care deeply about our shared humanity, and it is those people that make the world safe. Should we retreat from the world out of fear, we do ourselves, and every decent horrified person around us, a disservice.

Following horror might be an overwhelming grief at the pain and suffering inflicted upon innocent people. This grief can lead to a feeling of powerlessness and despondency, one that again nudges us to retreat from the world. But, as painful as it is, our grief is proportional to our love. If we didn’t care for the lives of others – even people we have never met and will never know – then we wouldn’t feel grief. So we needn’t let grief strip us of our agency. Instead, we can let it remind us to lean into love and motivate us to reach out to others with greater patience and understanding.

A fire for justice

Possibly the most dangerous emotion in this list is outrage. This is another primitive emotion that motivates us to correct wrongdoing and punish wrongdoers. Outrage demands satisfaction, but it’s often not fussy about how that satisfaction is achieved. Great evils have been committed at the hand of outrage, and great injustices perpetrated to satisfy its call.

We must acknowledge when we feel outrage but be wary of its call to immediately find someone to blame and punish. Within an hour of the shooting, the media was already mentioning a name of one of the attackers, feeding the audience’s hunger for justice. But in its haste, it caught up an innocent man who then experienced unwarranted threats. Others rushed to blame the authorities for failing to prevent the attack or refusing to combat antisemitism.

Even when things look clear at first glance, we must remind ourselves that it’s all too easy to blame the wrong person or seek punishment just for the sake of satisfaction. And sometimes there is no one person to blame. Sometimes the causes of an atrocity are complex and interlaced. Sometimes there were multiple causes and nothing anyone could have done to prevent it. So we must temper outrage with a deeper commitment to genuine justice, lowering the temperature and working to understand the whole picture before calling for punishment.

I acknowledge that it can be difficult to pause in the heat of the moment, especially when we only have a fragmentary grasp of what’s going on and what caused it.

In times of uncertainty or ambiguity, we crave clarity and certainty. We seek out and latch on to the first available narrative that seems to make sense of a great tragedy. We like the feeling of being certain more than we like doing the work to interrogate our beliefs to ensure they warrant certainty.

We thus have a tendency to be drawn to narratives that align with our pre-existing beliefs or biases. Uncertainty and ambiguity can be like a Rorschach test. The patterns we see tell us more about ourselves than reality. If we don’t want to exacerbate injustice by generating or sharing false narratives that can cause real harm, we need to learn to sit with the uncertainty and dwell in the ambiguity. We are not naturally inclined to do so, but that only means we need to practice getting better at it.

The very fact we typically experience emotions like horror, grief, outrage and uncertainty speak to our deeper humanity. They speak to how much we care about others and living in a world where everyone deserves to be safe and thrive. If we allow the better angels of our nature to rise to the surface, and resist the temptation to satisfy our emotions in ways that cause more harm, we can respond in a genuinely ethical way.

Image by ZUMA Press, Inc / Alamy

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? The story of moral panic and how it spreads

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

A message from Dr Simon Longstaff AO on the Bondi attack

A message from Dr Simon Longstaff AO on the Bondi attack

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 15 DEC 2025

On behalf of everyone who works at The Ethics Centre – our board, staff and volunteers – I am writing to all of our members and supporters to offer our heartfelt sympathy to those affected by the terrorist attack that took place, in Bondi, last night.

Some might observe that this is not the biggest atrocity to have taken place in the world this year. However, I do not believe that atrocities should be ranked according to the numbers of people killed and maimed. What defines such events, as evil, lies in the perpetrator’s intent to harm people; not because of what they have done, or what they believe – but simply because of who they are.

Last night was not an indiscriminate act of terror. People were targeted merely for being Jewish – men, women, children … people of every type and description. Whether you lived or died had nothing to do with one’s politics or opinions about the world. Simply being Jewish – indeed, simply being in the midst of the Jewish community – was enough for you to be targeted. This was antisemitism in its most violent form.

As I write this note, we still do not know what motivated the terrorists. However, nothing can make good what they did – cold-blooded murder can never be justified … no matter who does the killing, no matter who is the victim, no matter how many reasons are advanced.

Now, I fear that the cycle will take another turn for the worse. Members of other communities will fear that they will be tarred with the same brush as the terrorists – no matter what they have done, no matter what they believe – but simply because of who they are.

Surely, surely it is time to stop this vicious wheel from turning.

At The Ethics Centre, we believe in the intrinsic dignity of all persons – without exception. This recognition has no boundaries and, difficult as it may be, must extend even to those who visit terror upon us. At times like this, we should embrace our common humanity – and not give way to those who would stoke and exploit divisions for their own ends.

Many people will be hurting today – even if far removed from the carnage. Many will be angry or confused, or feeling helpless or just numb. I think I have felt all of those emotions since the tragic events of last evening began to unfold. However, in the midst of all of this, we can hold onto the fact that what happens next is not inevitable.

Our governments will take the lead in providing security – but only we, the people, can create the conditions of ‘belonging’ in which every person can feel safe in the warm embrace of a society that recognises the intrinsic dignity of all. In this, let’s not forget the bravery of those who confronted the gunmen, who rendered first aid, who comforted the dying or offered sanctuary within their homes. These people show what is possible when the good in us comes forth.

Making and sustaining just such a society – even in the face of terror – is what each of us can do. I hold onto that – and in the midst of pain and confusion hope you might do the same.

Image: Paul Lovelace / Alamy

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The art of appropriation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Society + Culture

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Why leisure matters for a good life, according to Aristotle

Why leisure matters for a good life, according to Aristotle

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Ross Channing Reed 4 DEC 2025

In his powerful book “The Burnout Society,” South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues that in modern society, individuals have an imperative to achieve. Han calls this an “achievement society” in which we must become “entrepreneurs” – branding and selling ourselves; there is no time off the clock.

In such a society, even leisure risks becoming another kind of work. Rather than providing rest and meaning, leisure is often competitive, performative and exhausting.

People feeling pressure to self-promote, for example, might spend their free time posting photos of an athletic race or an elaborate vacation on social media to be viewed by family, friends and potential employers, adding to exhaustion and burnout.

As a philosopher and philosophical counselor, I study connections between unhealthy forms of leisure and burnout. I have found that philosophy can help us navigate some of the pitfalls of leisure in an achievement society. The celebrated Greek philosopher Aristotle, who lived from 384 to 322 B.C.E., in particular, can offer important insights.

Aristotle on self-development

Aristotle begins the famous Nicomachean Ethics by pointing out that we are all searching for happiness. But, he says, we are often confused about how to get there.

Aristotle believed that pleasure, wealth, honour and power will not ultimately make us happy. True happiness, he said, required ethical self-development: “Human good turns out to be activity of soul in accordance with virtue.”

In other words, if we want to be happy, Aristotle contended, we must make reasoned choices to develop habits that, over time, become character traits such as courage, temperance, generosity and truthfulness.

Aristotle is explicitly linking the good life to becoming a certain kind of person. There is no shortcut to ethical self-development. It takes time – time off the clock, time not engaged in some kind of entrepreneurial self-promotion.

Aristotle is also telling us about the power of our choices. Habits, he argues, are not just about action, but also motives and character. Our actions, he says, actually change our desires. Aristotle says: “By abstaining from pleasures we become temperate, and it is when we have become so that we are most able to abstain from them.”

In other words, good habits are the result of moving incrementally in the right direction through practice.

For Aristotle, good habits lead to ethical self-development. The converse is also true. To this end, for Aristotle, having good friends and mentors who guide and support moral development are essential.

How Aristotle helps us understand leisure

In an achievement society, we are often conditioned to respond to external pressures to self-promote. We may instead look to pleasure, wealth, honour and power for happiness. This can sidetrack the ethical development required for true happiness.

True leisure – leisure that is not bound to the imperative to achieve – is time we can reflect on our real priorities, cultivate friendships, think for ourselves, and step back and decide what kind of life we want to live.

The Greek word eudaimonia, often translated simply as happiness, is the term Aristotle uses to describe human thriving and flourishing. According to philosopher Jane Hurly, Aristotle views “leisure as essential for human thriving”. Indeed, “for both Plato and Aristotle leisure… is a prerequisite for the achievement of the highest form of human flourishing, eudaimonia”, as philosopher Thanassis Samaras argues.

While we may have limited means to acquire pleasure, wealth, honour and power, Aristotle tells us that we have control over the most important variable in the good life: what kind of person we will become. Leisure is crucial because it is time in which we get to decide what kind of habits we will develop and what kind of person we will become. Will we capitulate to achievement society? Or utilise our free time to develop ourselves as individuals?

When leisure is preoccupied with entrepreneurial self-promotion, it is difficult for moral development to take place. Free time that is not hijacked by the imperative to achieve is required for the development of a consistent relationship to oneself – what I call a relationship of self-solidarity – a kind of reflective self-awareness necessary to aim at the right target and make moral choices. Without such a relationship, the good life will remain elusive.

Leisure reimagined

Rather than adopting the achievement society’s formulation of the good life, we may be able to formulate our own vision. Without one’s own vision, we risk becoming mired in bad habits, leading us away from the moral development through which the good life becomes possible.

Aristotle makes it clear that we have the power to change not only our behaviours but our desires and character. This self-development, as Aristotle writes, is a necessary part of the good life – a life of eudaimonia.

The choices we make in our free time can move us closer to eudaimonia. Or they could move us in the direction of burnout.

The article was originally published in The Conversation.

BY Ross Channing Reed

Ross Channing Reed, Ph.D., teaches philosophy at Missouri University of Science and Technology. His areas of research include philosophical psychology and philosophical counselling, addiction, trauma, existentialism, ethics, and philosophy of religion.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Health + Wellbeing

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Twitter made me do it!

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Eudaimonia

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + Leadership

BY Dia Bianca Lao 24 NOV 2025

“If a human worker does $50,000 worth of work in a factory, that income is taxed. If a robot comes in to do the same thing, you’d think we’d tax the robot at a similar level,” Bill Gates famously said. His call raises an urgent ethical question now facing Australia: When AI replaces human labour, who pays for the social cost?

As AI becomes a cheaper alternative to human labour, the question is no longer if it will dramatically reshape the workforce, but how quickly, and whether the nation’s labour market can adapt in time.

New technology always seems like the stuff of science fiction until its seamless transition from novelty to necessity. Today AI is past its infancy and is now shaping real-world industries. The simultaneous emergence of its diverse use cases and the maturing of automation technology underscores how rapidly it’s evolving, transforming this threat into reality sooner than we think.

Historically, automation tended to focus on routine physical tasks, but today’s frontier extends into cognitive domains. Unlike past innovations that still relied on human oversight, the autonomous nature of emerging technologies threatens to make human labour obsolete with its broader capabilities.

While history shows that technological revolutions have ultimately improved output, productivity, and wages in the long-term, the present wave may prove more disruptive than those before. In 2017, Bill Gates foresaw this looming paradigm shift and famously argued for companies to pay a ‘robot tax’ to moderate the pace at which AI impacts human jobs and help fund other employment types.

Without any formal measures, the costs of AI-driven displacement will likely mostly fall on workers and society, while companies reap the benefits with little accountability.

According to the World Economic Forum, while AI is predicted to create 69 million new jobs, 83 million existing jobs may be phased out by 2027, resulting in a net decrease of 14 million jobs or approximately 2% of current employment. They also projected that 23% of jobs globally will evolve in the next five years, driven by advancements in technology. While the full impact is not yet visible in official employment statistics, the shift toward reducing reliance on human labour through automation and AI is already underway, with entry-level roles and jobs involving logistics, manufacturing, admin, and customer service being the most impacted.

For example, Aurora’s self-driving trucks are officially making regular roundtrips on public roads delivering time- and temperature-sensitive freight in the U.S., while Meituan is making drone deliveries increasingly common in China’s major cities. We now live in a world where you can get your boba milk tea delivered by a drone in less than 20 minutes in places like Shenzhen. Meanwhile in Australia, Rio Tinto has also deployed fully autonomous trains and autonomous haul trucks across its Pilbara iron ore mines, increasing operational time and contributing to a 15% reduction in operating costs.

Companies have already begun recalibrating their workforce, and there is no stopping this train. In the past 12 months, CBA and Bankwest have cut hundreds of jobs across various departments despite rising profits. Forty-five of these roles were replaced by an AI chatbot handling customer queries, while the permanent closure of all Bankwest branches has seen the bank transition to a digital bank, with no intention of bringing back the lost positions. While some argue that redeployment opportunities exist or new jobs might emerge, details remain vague.

Is it possible to fully automate an economy and eliminate the need for jobs? Elon Musk certainly thinks so. It’s no wonder that a growing number of tech elite are investing heavily to replace human labour with AI. From copywriting to coding, AI has proven its versatility in speeding up productivity in all aspects of our lives. Its potential for accelerating innovation, improving living standards and economic growth is unparalleled, but at what cost?

What counts as good for the economy has historically benefited a select few, with technology frequently being a catalyst for this dynamic. For example, the benefits of the Industrial Revolution, including the creation of new industries and increased productivity, were initially concentrated in the hands of those who owned the machinery and capital, while the widespread benefits trickled down later. Without ethical frameworks in place, AI is positioned to compound this inequality.

Some proposals argue that if we make taxes on human labour cheaper while increasing taxes on AI machines and tools, this could encourage companies to view AI as complementary instead of a replacement for human workers. This levy could be a means for governments to distribute AI’s socioeconomic impacts more fairly, potentially funding retraining or income support for displaced workers.

If a robot tax is such a good idea, then why did the European Parliament reject it? Many argue that taxing productivity tools could hinder competitiveness. Without global coordination to implement this, if one country taxes AI and others don’t, it may create an uneven playing field and stifle innovation. How would policymakers even define how companies would qualify for this levy or measure how much to tax, when it’s hard to attribute profits derived from AI? Unlike human workers’ earnings, taxing AI isn’t as straightforward.

The challenge of developing policies that incentivise innovation while ensuring that its benefits and burdens are shared responsibly across society persists. The government’s focus on retraining and upskilling workers to help with this transition is a good start, but they cannot address all the challenges of automation fast enough. Relying solely on these programs risk overlooking structural inequities, such as the disproportionate impact on lower-income or older workers in certain industries, and long-term displacement, where entire job categories may vanish faster than workers can be retrained.

Our fiscal policies should adapt to the evolving economic landscape to help smooth this shift and fund social safety nets. A reduction in human labour’s share in production will significantly impact government revenue unless new measures of taxing capital are introduced.

While a blanket “robot tax” is impractical at this stage, incremental changes to existing taxation policies to target sectors that are most vulnerable to disruption is a possibility. Ideally, policies should distinguish the treatment between technologies that substitute for human labour, and those that complement them, to only disincentivise the former. While this distinction can be challenging, it offers a way to slow down job displacement, giving workers and welfare systems more time to adapt and generate revenue to help with the transition without hindering productivity.

As Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella warns, “With this empowerment comes greater human responsibility — all of us who build, deploy, and use AI have a collective obligation to do so responsibly and safely, so AI evolves in alignment with our social, cultural, and legal norms. We have to take the unintended consequences of any new technology along with all the benefits, and think about them simultaneously.”

The challenge in integrating AI more equitably into the economy is ensuring that its broad societal benefits are amplified, while reducing its unintended negative consequences. AI has the potential to fundamentally accelerate innovation for public good but only if progress is tied to equitable frameworks and its ethical adoption.

Australia already regulates specific harms of AI, protecting privacy and personal information through the Privacy Act 1988 and addressing bias through the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs). These examples show that targeted regulation is possible. However, the next step should include ethical guardrails for AI-driven job displacement, such as exploring more equitable taxation, redistribution policies, and accountability frameworks before it’s too late. This transformation will require joint collaboration from governments, companies, and global organisations to collectively build a resilient and inclusive AI-powered future.

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future by Dia Bianca Lao is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ 2025 Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

BY Dia Bianca Lao

Dia Bianca Lao is a marketer by trade but a writer at heart, with a passion for exploring how ethics, communication, and culture shape society. Through writing, she seeks to make sense of complexity and spark thoughtful dialogue.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

It’s time to consider who loses when money comes cheap

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

Who gets heard? Media literacy and the politics of platforming

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Aubrey Blanche 20 NOV 2025

In an age where emotionally charged information travels faster than ever, the ability to critically evaluate what we read, watch, and share is the cornerstone of responsible citizenship. It’s essential that we’re able to strengthen our media literacy skills to detect bias, maintain trust and safeguard the integrity of public discourse.

Since the rise of generative AI, we have become inundated with content. It’s easier to generate and disseminate information than ever before. When content is cheap, it’s curation and discernment that becomes ever more critical.

And this matters – how information travels influences policy, the bounds of acceptable discourse, and ultimately how our society functions. This means that each of us, whether a social media user, producer of a major national news program, or just someone chatting with a friend, has an obligation to ensure that the truth we share contributes to human flourishing.

What is verifiable?

The reality is that a huge amount of the information we have access to is, well, fake. Media literacy equips people to recognise bias, detect misinformation, and understand the motives behind content creation. Without these skills, we and those around us become vulnerable to manipulation, whether through sensational headlines, deepfakes, or algorithm-driven echo chambers.

Verifying information before sharing is a critical part of media literacy. Every click and share amplifies a message, whether true or false. For example, deepfakes of Scott Morrison and other politicians have been used to perpetuate investment scams. When inaccurate information spreads unchecked, it can fuel polarisation, erode trust in institutions, and even endanger lives. Taking a moment to analyse the source, check for corroboration in other trusted places, and question the credibility of a claim is a small act with enormous impact. It transforms passive consumers into active participants in a healthier information ecosystem.

Whose truth?

What we see as objective is intrinsically shaped by the voices we are exposed to, and how often. This is as true for our social media feeds as it is for the nightly news. The messages that reach us are all in some way biased, meaning that they possess some kind of embedded agenda. But what we most often mean when we talk about bias, is a systematic and repeated filtering or skewing of information to conform to a particular or narrow agenda or worldview.

Because of this, we should be wary of potential bias when issues are covered by individuals or organisations with financial or political interests at stake. For example, jurisdictions around the world are currently wrestling with questions of how training large language models (LLMs) relates to fair use of copyrighted work. In Australia, the government recently ruled out a special exception for AI models to be trained on Australian works without explicit permission or payment. While there was public consultation conducted, prominent voices didn’t all agree with protecting the labor and output of creators as a priority.

Before the federal government made the determination, powerful members of the technology industry were consulted by journalists for their views on how the interests of AI labs and creators should be considered. These voices included those whose financial holdings include investments in the type of AI companies (and their methods) being discussed. Platforming voices with these interests has important implications for setting the terms of the debate as potentially more pro-technology, rather than encouraging a balance of perspectives.

While this specific issue is critical because it’s an issue that affects all of us, it also illustrates a way that we can practice media responsibly.

When we are sharing information, we should consider the interests and ideological alignment of those who are sharing.

Where possible, we should seek to provide a balanced set of perspectives, and ideally one in which any conflicts of interest are clear and disclosed.

Who gets platformed?

There is no free marketplace of ideas. The question of what voices and perspectives are platformed and held up as truth, whether in the media or on our feeds, greatly impacts our our own narratives of events. For example, since October 2023, more than 67,000 Gazans have been killed by Israeli forces. While the genocide has received significant media coverage, the perspectives of people impacted haven’t been equitably represented in mainstream media sources. Recently, a study found that only one Palestinian guest had been booked to share their views on major US Sunday news shows (which set the national agenda) in the last 2 years. In the same period, 48 Israeli guests had been given airtime.

If we assume that Israeli guests do not have a monopoly on the truth, this pattern looks alarming. While this study didn’t speak to the views of the guests, a reasonable person would assume that such a skew in the identities and affiliations represented present a rather one-sided view of events on the ground.

In this case, the platforming also speaks to the relative power of the perspectives. Despite the Palestinian community having the greatest lived experience of harm, their voices are effectively silenced. As we consider from whom we share information, we should always consider the following questions:

- Which individuals or groups have greater access to institutions – media or otherwise – to share their experience?

- In the case of conflict, are opposing forces equally powerful (eg in terms of financial resources, alliances, etc)?

- Who is marginalised, and what is the impact of not platforming that voice?

In today’s media environment, we are flooded with information. This means that the responsibly each of us must take in our sphere of influence has increased proportionally. In order to act as responsible members of our community, we must question which voices we’re highlighting.

BY Aubrey Blanche

Aubrey Blanche is a responsible governance executive with 15 years of impact. An expert in issues of workplace fairness and the ethics of artificial intelligence, her experience spans HR, ESG, communications, and go-to-market strategy. She seeks to question and reimagine the systems that surround us to ensure that all can build a better world. A regular speaker and writer on issues of responsible business, finance, and technology, Blanche has appeared on stages and in media outlets all over the world. As Director of Ethical Advisory & Strategic Partnerships, she leads our engagements with organisational partners looking to bring ethics to the centre of their operations.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

It’s time to increase racial literacy within our organisations

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

We are witnessing just how fragile liberal democracy is – it’s up to us to strengthen its foundations

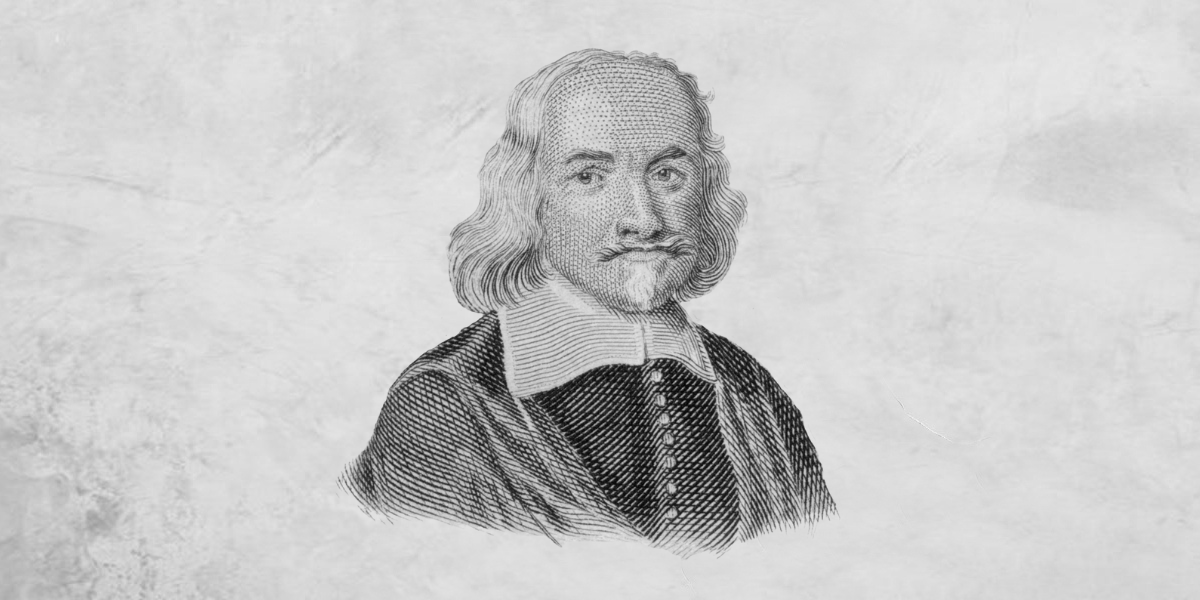

Big Thinker: Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his explanation of the role of government as an insurer of security, which has had an enduring influence on understandings of political philosophy.

Living through the displacement of the English Civil War (1642-1651), Hobbes was grappling with the question of how societies could keep peace and ensure stability, amid conflict and self-interest. The period was marked by social upheaval with the collapse of royal authority, clashes between the government and monarchy and insecurity, which led to him thinking about the manifestations of power, the human condition and the role of government.

His approach to understanding human behaviour was methodical and scientific, being deeply influenced by the scientific revolution of the time. Hobbes believed that human societies, like physical systems, could be understood through cause and effect and that understandings of order and stability were derived from the predictability of human behaviour and power structures.

The state of nature

It was from this historical and intellectual backdrop that Hobbes produced his most famous work, Leviathan (1651). His masterwork Leviathan: The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, garnered him fame for creating what would later become known as the Social Contract Theory, a framework that explains and justifies the exchange that free, equal and rational citizens make in surrendering certain freedoms in return for collective order and protection. This same contract also serves to provide legitimacy to governments and their use of power and authority over citizens.

In Leviathan and his other work, Hobbes disagrees with Aristotle that humans are naturally suited to life as citizens within a state. Hobbes instead argues that humans are not equipped to be rational citizens, as we are easily swayed, often short sighted and highly competitive. He believes these characteristics make humans more predisposed to violence and war rather than political order, with no natural self-restraint. Hobbes states that in this state of nature, without government and order, the life of man is “poor, nasty, brutish and short”, largely due to the insecurity and conflict. Everyone is free and equal, without any rules or restrictions to their actions and coupled with a self interested nature and limited resources, life in this state is a constant struggle.

The social contract

To escape this constant struggle in this state of nature, Hobbes argues that people, through reason, collectively agree to create a social contract. Hobbes believes that political order is only formed when human beings voluntarily give up some of their rights and freedoms, in exchange for order and security from a common authority, the leviathan (a ruler).

Hobbes uses the Leviathan as a metaphor for a powerful ruler or government that embodies the collective will of the people, possessing absolute authority to maintain peace and prevent society from descending back into chaos. Hobbes conception of a social contract and the role of the sovereign or leviathan, refers to these key characteristics:

- The sovereign or leviathan’s power must be absolute – only one authority, as divided power invites factionalism.

- The contract is driven by the purpose of security.

- Individuals cannot revoke the contract once it’s been made, as it would risk bringing back chaos.

- The contract is between the people and the sovereign is not party to this agreement. However, if the sovereign fails to maintain peace and security, the contract loses legitimacy and people return to the state of nature.

This framework for the social contract theory by Hobbes, was adopted by John Locke and Jean-Jaques Rousseau. However, they differed from Hobbes by offering a more optimistic view of human behaviour and the role of government. Critical responses tended to focus on a lack of accountability measures on the leviathan who has expansive absolute power. Locke for example took a liberal view, involving limited government and argued the leviathan was mutually obligated within a social contract, rather than subjects being expected to obey unconditionally to avoid the collapse of civil society.

Hobbes’s ideas continue to shape how government and authority is understood. While very few modern states reflect the vision of an absolute sovereign, the core principles of the social contract theory remain central to political thought. The consent of citizens to be governed in exchange for protection and the rule of law persists. However, in modern liberal democracies, the power of governments is placed under greater scrutiny through constitutions, elections and other checks and balances. Hobbes’s theory provides the foundation for understanding why societies form governments, even as modern democracies reinterpret his ideas to prioritise liberty, representation, and accountability alongside security and order.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Why sometimes the right thing to do is nothing at all

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Berejiklian Conflict

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What it means to love your country

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Social Contract

Should we be afraid of consensus? Pluribus and the horrors of mainstream happiness

Should we be afraid of consensus? Pluribus and the horrors of mainstream happiness

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 12 NOV 2025

Partway through Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the author neatly summarises one of the more troubling questions that undercuts civilisation: is it ethical for widespread happiness to come at the expense of the discontent of select individuals? Or, to put it simply: do the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few?

“Let’s assume that you were called upon to build the edifice of human destiny so that men would finally be happy”, the troubled Ivan Karamazov says. “If you knew that, in order to attain this, you would have to torture just one single creature, would you agree to do it?”

That one question has been probed and explored time and time again in the years since Karamazov was published, most notably in Ursula LeGuin’s sci-fi story The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, in which the happiness of a flourishing city depends totally on the torture of a young girl. But it has perhaps never been as thoroughly – not to mention amusingly – explored to the extent that it is in Pluribus, the new sci-fi show from Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan.

In Gilligan’s re-telling, near-global happiness is an external force: a virus of sorts, which turns the world’s population into a hive mind of mutually contented drones. The one miserable, unlucky individual whose perpetual unhappiness sets her apart from the mainstream: Carol Sturka (Rhea Seehorn), who appears to be immune to the virus. Or rather, temporarily immune, given much of the early episodes of the show follows the rising, blackly comic threat of the hive mind searching for ways to make Carol one of them.

“Once you see how wonderful it is….” a member of the hive mind tells Carol early on, speaking to her directly from her television set. The hive promises happiness, peace and the end of all human conflict. What they also represent: the tyranny of mainstream thought, an enforced and established consensus where majority rules, no matter how discontented outliers might be. And where happiness itself is dangerously considered the main goal of all human existence.

The problem with happiness

One of Gilligan’s masterstrokes is to set Carol out of the mainstream even before the virus spreads. When we meet her, she’s a beloved romantasy author who can’t stand either the mindless content that she churns out, or the horde of rabid fans who adore her. In the first episode, her business/life partner Helen (Miriam Shor) mocks Carol’s dislike of adulation, teasing that she’s a perpetual miser, illogically rejecting the good time that’s being offered to her.

But when the mainstream offers mere happiness, we should reject it, as both Gilligan and Dostoyevsky seem to suggest. A life of contentment and fitting in with the crowd isn’t an ethical good in and of itself. As the rise of increasingly deranged social media slop proves – the kind of quick dopamine fix provided by TikTok – there’s so much more to life than merely being entertained.

The person who sits in their room all day watching Instagram reels could conceivably be very happy, but wouldn’t we all suggest that they might want more? Should they in fact pursue something greater and more important than simply having a good time?

This is the threat posed by Pluribus’ hive. In an ideal world, happiness should be a kind of side effect of good, not something to be pursued blindly for its own sake. As in, happiness should be what happens when we achieve virtuous behaviours – when we care for others, or pursue a flourishing life. And it certainly should not be enforced by the mainstream at the expense of individual freedoms and wants.

Even as Pluribus’ plot progresses, and it is revealed that Carol’s unhappiness is a very literal threat to the hive – when she lashes out at them, members of the hive abruptly die – the needs of those who sit in the mainstream should never be held above the deep unhappiness of those who also must operate within the world. Not only because enforcing the desires of the collective onto the individual is a harm in itself, but because sometimes – maybe even often – the desires of the collective aren’t particularly desirable.

In praise of conflict

Pluribus slowly encourages us to be suspicious of the idea that the hive are actually as happy as they claim to be. Do we really think that happiness is only a flood of dopamine throughout our body? If so, then as the philosopher Robert Nozick once asked, wouldn’t we therefore choose to step into a machine that did nothing but probe our dopamine receptors for all eternity, living an artificial life where we submit to being little more than switches that can be flipped in order to produce joy?

It doesn’t seem like many of us consider happiness only that. Happiness is what happens when we go to the other side of hardship; when we set ourselves goals and then achieve them. Ultimately, it’s a response to conflict and unhappiness, not the absence of conflict and unhappiness altogether.

Enforced mainstream happiness isn’t just ethically harmful for those who have it enforced upon them; it might be harmful to those who actively want it.

In the age of AI, these issues have never been more timely. In fact, Gilligan himself seems aware of this: each episode of Pluribus ends with a message, hidden in the credits, that reads, “this show was made by humans”.

We live in an era where tech companies constantly promise us that AI will bring ease, contentment, and the ability to fit in with our co-workers, friends and family – with the collective. Even if AI can do our jobs for us, or write tricky text messages to our loved ones, decreasing our discomfort, why would we even want that?

Now more than ever, we should follow Carol’s lead and become perpetual sourpusses. As it turns out, being a grump might be one of the most ethical things of all.

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What is all this content doing to us?

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture

Read me once, shame on you: 10 books, films and podcasts about shame

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Society + Culture

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Standing up against discrimination

Standing up against discrimination

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Mariam Sawan 11 NOV 2025

A fantastic opportunity arrived when Courage to Care NSW and The Ethics Centre launched a pivotal program for young people across our state, proudly funded by Multicultural NSW’s Compact Grant program. The focus? One of the most pressing struggles Australians continue to face or witness: discrimination.

Over three days, Year 9 and 10 students from across the Illawarra gathered at the Wollongong Youth Centre to take part in the Common Ground program. Together, we learnt not only to recognise discrimination in its many forms but also to challenge and overcome it, helping to build a community where everyone feels safe and accepted, regardless of culture, background, or ability.

Before participating in the program, I understood discrimination only as something “bad” – a simple wrong we were all taught to avoid, without ever questioning why it happens or what sustains it.

Growing up with a multicultural background, I have faced many stereotypical insults, but I never really saw them as a big deal. I knew discrimination existed, but I only saw it at face value – people saying hurtful things to make themselves feel better. Through a series of activities, case studies and creative programs, Common Ground showed me just how complex it is. While I knew discrimination could involve gender, religion, disability, and age, I had assumed it only appeared in big, obvious ways like bullying. I had not considered the smaller, everyday forms such as jokes, exclusion, or subtle assumptions. I learnt how hidden these forms of discrimination can be, shifting my mindset completely. Now I am more empathetic and aware, thinking about the meaning behind a joke rather than dismissing it and have the confidence and practical skills needed to fight what can only be described as a virus of hatred.

What stood out most was how effortlessly the organisers drew us into a topic we’d all heard about countless times before. But this time, it felt different. We were guided by “value cards” that highlighted the program’s principles, especially the three C’s: curiosity, carefulness, and courage. These sparked deep discussions about what those values meant to each of us, encouraging us to explore the issue of discrimination on a personal level.

I had previously thought curiosity was only about seeking knowledge, but the program taught me it is about listening and understanding people’s experiences without judgment. Carefulness is not just about thinking before speaking; it is also about considering how my actions affect others. Courage is having the confidence to try something new and to challenge discrimination respectfully. Hearing how other students approached these values showed me there is more than one way to make a difference and that small actions can matter just as much as big ones. My perspective changed completely.

The activities Common Ground provided were equally eye-opening. An online game showed how misinformation spreads like wildfire on social media, shaping perceptions and fuelling prejudice. Another exercise asked us to “buy privileges” for a child, using only a limited budget. The unfairness of unequal resources became painfully clear as some children could afford opportunities while others missed out. In our final group project, we created videos exploring real experiences of discrimination and brainstorming ways to combat it.

The third and final day brought together students from across the Wollongong LGA for a mix of learning, competition, and celebration. Two teams tied for the People’s Choice Award, with powerful presentations on racial and religious discrimination. The overall winners, however, tackled racial discrimination in a striking way. Their victory came with $1,000 in prize money, which they generously donated to Illawarra Multicultural Services, an organisation that supports migrants and refugees with housing, jobs, and community support.

By the end of the program, the message was clear. We, as young people, had not only learned how to recognise discrimination – even in its subtlest forms – but also how to respond with confidence, safety, and integrity.

The Common Ground program didn’t just teach us about injustice; it empowered us to become catalysts for change, fostering communities built on diversity, inclusiveness, and support.

Common Ground is a workshop program for Year 9-10 students that empowers them to stand up against discrimination. We’re taking expressions of interest for schools in South West Sydney to join this free program in Term 2, 2026. Register your school’s interest today by contacting us at learn@ethics.org.au.

BY Mariam Sawan

Mariam Sawan is a high school student who enjoys learning about how people can make a positive impact in their community and understanding people’s points of view. After participating in the Common Ground program on discrimination, she was inspired to write the article “Standing Up Against Discrimination”. Through her writing, she hopes to encourage others to treat everyone with fairness and respect and to feel empowered to speak up against injustice.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Duties of care: How to find balance in the care you give

Explainer

Relationships