Economic reform must start with ethics

Economic reform must start with ethics

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff 15 AUG 2025

With inflation tamed, interest rates falling and wages rising, the government of Anthony Albanese has worked itself into a position where it can now develop a range of longer-term economic initiatives.

With this in mind, the government will convene an Economic Roundtable next week to consider ideas about how to best to achieve sustainable prosperity.

I suspect that the Roundtable will focus on a range of ‘big ticket’ ideas for innovation and reform in areas such as tax, energy, infrastructure, industrial relations and the like. If all goes well, equal attention will be given to areas of social policy that have a major impact on the economy – including in areas such as childcare, mental health, social welfare, etc. Although not falling under a narrow heading of ‘economic policy’, all of these areas have a significant impact on the productive capacity of the Australian economy. In other words, a strong economy depends as much on sound ‘social’ policies as it does on sound ‘economic’ policies.

However, there is a deeper ethical dimension that we hope will also be taken into account. Over a period of four years, Deloitte Access Economics has been exploring the link between ethics and the economy. Most recently, its work has zeroed in on the connection between ethics and productivity. Their findings are as follows:

The relationship between ethics and productivity is increasingly recognised in economic literature and international practice.

There is capacity for trust and ethical behaviour to:

- Boost worker wellbeing and mental health, which are directly linked to labour productivity.

- Improve business performance, with higher ethical standards leading to stronger returns on investment.

- Reduce red tape, by lowering the perceived need for regulation in high-trust environments.

- Enable economic reform, by building public support for complex policy changes.

- Accelerate the uptake of technology, such as artificial intelligence, where trust remains a key adoption barrier.

This has remarkable implications for our nation’s prosperity (in both economic and social terms):

- A 10% improvement in ethical behaviour yields a 2.7% wage increase and a 1% gain in mental health, worth over $23 billion across the economy.

- A standard deviation increase in business governance is associated with a 7% increase in return on assets.

- Countries with higher social trust experience 15-19% fewer regulatory procedures to start a business.

- Aligning Australia’s trust levels with global leaders could lift GDP by $45 billion, or $1,800 per person.

There should be no mystery in this, and the effects are clear and simple. Much of it comes down to the possibility of reform (of any kind). Identifying areas of reform is relatively easy. The difficulty relies in their adoption. This is because all reform is subject to resistance from those who fear that they will be left worse off. In turn, strong resistance creates friction that either slows or prevents reform – inevitably leading to sub-optimal outcomes for society as a whole. The number of people who fear being left worse off is often greater than the number of people who will actually be adversely affected. Even when people recognise that they are likely to benefit from reform – they will still oppose it in the belief that the ‘people in charge’ cannot be trusted to ensure that the benefits and burdens are fairly distributed. In other words, it all boils down to questions of trust. And as economists have known since the dawn of their ‘dismal science’ – high trust=low cost and low trust=high cost.

Yet, trust itself is a function of ethical alignment. Ethics, and the trust it engenders, reduces ‘friction’. Thus, trust is a catalyst and enabler of productive reform. To put it simply:

Good ethics → improved trust → greater prosperity.

There are some deep paradoxes in this outcome. The most challenging of these is that although ethics produces a demonstrable economic dividend, it only has maximum effect if people act for non-instrumental reasons. In other words, ‘you don’t get the dividend if you do it for the dividend.’

We have long believed that the whole of Australia would benefit if, as a society, we invested more in revitalising our ‘ethical infrastructure’ alongside the physical and technical infrastructure that typically receives all of the attention and funding.

The evidence is clear that good ethical infrastructure enhances the ‘dividend’ earned from these more typical investments – while bad ethical infrastructure only leads to sub-optimal outcomes.

I doubt that the link between ethics, trust and prosperity will capture any headlines when the Economic Roundtable is convened. But wouldn’t it be great if it could at least be noted as a vital enabler of any reform that hopes to succeed.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

A foot in the door: The ethics of internships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: How to approach differing work ethics between generations?

Give them a piggy bank: Why every child should learn to navigate money with ethics

Give them a piggy bank: Why every child should learn to navigate money with ethics

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Dr. Helen Hoang 12 AUG 2025

“Mum, why can we buy toys, but others can’t?”

My son’s question seemed simple, but behind it lay deeper questions about scarcity and fairness. And like many parents, I found myself unprepared to explain a system even most adults struggle to fully understand.

Growing up in a remote village in northern Vietnam, I experienced scarcity first-hand. Only one child per family could attend school while the rest worked. These were choices shaped by poverty and silence. Worse, no one asked why. And that’s what drew me to economics: to find not just answers, but better questions and solutions.

What if we taught kids not just how economies work, but why they work that way? What if, from a young age, they learned that the economy isn’t just numbers, but a system shaped by values, power, and people? It could transform their worldview and their future.

Australia is facing a quiet crisis in economic and financial literacy. More than 1 in 6 Australian 15-year-olds fail basic financial literacy. The issue is particularly stark among young women: only 15% meet standards, compared to 28% of boys. Meanwhile, enrolments in Year 12 economics have dropped by nearly 70% since the 1990s. The Reserve Bank of Australia warns that a lack of economic understanding not only limits personal well-being but also weakens national participation. The National Australia Bank has reported increasing financial vulnerability among youth with low literacy levels.

But this isn’t just a gap in knowledge, it’s a growing divide in civic understanding.

Why financial and economic literacy must be taught with ethics

Too often, financial and economic literacy are conflated. In truth, they are distinct yet deeply complementary. Financial literacy teaches individuals how to manage money. Economic literacy explains the systems shaping those decisions. One is practical, the other structural.

What’s missing is ethics – understanding who the economy should serve. This requires critical thinking about values, justice, and responsibility. It involves teaching children that every economic decision is a moral one, and that their choices can help shape a fairer world.

By teaching financial and economic literacy alongside ethics, we not only teach survival skills, but cultivate thoughtful participants in a fairer economy.

This approach encourages them to assess trade-offs, consider long-term impacts, and understand the values reflected in their choices. It sharpens understanding of the hidden costs of our financial choices: the underpaid worker behind a “cheap” shirt, the personal data exchanged for a “free” app, and so on. In learning to not just ask “Can I afford this?” but “What does this cost others?”, students can develop both agency and empathy.

Three timeless economic lessons every child should learn

1. Choices and scarcity aren’t just a constraint, they’re questions of justice

Economics begins with scarcity: we live in a world of limited resources, so choices must be made. But helping children make smart trade-offs is often where financial literacy stops.

Ethical economics asks a harder question: Why are some people forced to make impossible choices while others never have to choose at all?

Our resources are not evenly distributed, and how they are distributed reveals the underlying values of our economic systems. Furthermore, the mechanics of limited choices reveal the moral concerns of our society, issues ethical economics serve to investigate.

When we teach children only to manage scarcity, to see limited choice as inevitable, we risk normalising injustice. But when we teach them to understand and question it – Who sets the rules? Who is left out? Why? – we nurture civic responsibility and moral courage.

2. Incentives and transactions: the ethics beneath every exchange

Children learn the logic of trade early: stickers for chores, screen time for good behaviour, lunchbox swaps at school. These are their first lessons in transactional incentives, one of economics’ most powerful tools.

But incentives are not morally neutral. They reflect what we value and who we reward.

When we teach economics as just transactions, kids learn to see the world only through profit and loss. Ethics, however, reminds us that not all trades are fair or impassioned, and not all incentives are neutral. Behind every transaction is a judgement. Behind every incentive is a set of assumptions. Without accounting for context, incentives risk rewarding privilege while penalising disadvantage.

Teaching children to recognise this helps them move beyond “getting what you deserve” to asking: Who is allowed to participate?

This teaches not just how to respond to incentives, but how to question what they promote and whom they serve.

3. Markets need morality

Markets are often framed as natural forces: efficient, self-correcting, and impartial. But they’re not.

Scottish economist Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” theory describes how individual self-interest can lead to collective benefit. Yet Smith, also a moral philosopher, warned that markets only work when anchored in trust, justice and social responsibility.

English economist and philosopher John Maynard Keynes also argued that when markets fail, as they do during crises like the Great Depression, governments have an ethical obligation to intervene. During COVID-19, children saw this play out in real time: their parents receiving stimulus payments, rent relief or panic buying. But did they understand why?

Well, they should. That’s the real lesson: markets need rules, and rules need values. Who gets what, and why? These questions encourage children to investigate systemic motives and hold them accountable to their ethical obligations. Teaching students that both markets and governments are designed by people and reflect our collective choices helps them understand they can shape these systems too.

Raising ethical citizens, not just economic agents

Teaching economic literacy without ethics risks raising informed consumers but disengaged citizens. But when we teach children that every economic choice reflects a set of values, we equip them with something far more powerful than a calculator; we give them a moral compass.

As Nobel Laureate Esther Duflo reminds us, ethical economic education is not about ideology. It is about humility, empathy and evidence. It is about empowering people to improve lives, not only their own, but others’.

So yes, give a child a piggy bank, and they may save for life. But teach them how economies work, who they serve, and what they exclude, and they will reimagine those systems with care. That is what it means to raise not just capable earners, but ethical citizens. And that is what we owe the next generation.

BY Dr. Helen Hoang

Dr. Helen Hoang is an economist, the founder and author of "Economics for Kids: Lessons from Fables to Fairy Tales," a series designed to make economics enjoyable and accessible for children. She advocates for early economic education through storytelling and real-world learning experiences.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Activist CEO’s. Is it any of your business?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Recovery should be about removing vulnerability, not improving GDP

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How cost cutting can come back to bite you

Four causes of ethical failure, and how to correct them

Four causes of ethical failure, and how to correct them

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 30 JUL 2025

Sometimes good people do bad things. It’s important to understand why so we can respond ethically.

The news is filled with stories of everyday people doing bad things. A small business owner might underpay workers, a senior manager in a corporation could be cutting corners to improve profit margins, or a protester damages a precious artwork to promote their cause.

It’s natural to feel outrage when we hear about incidents like this. We might condemn the perpetrator and want to see them punished. But not every wrongdoer is a moustache twirling villain. Often, they’re otherwise good people who are perfectly ethical in other aspects of their lives. This makes their bad behaviour especially puzzling.

If we don’t understand what motivates their behaviour, then we risk responding in a way that won’t fix the problem, or might even make things worse. Here are four different reasons why good people do bad things and some ways to prevent or correct them.

1. Weakness of will

Temptation is everywhere. Sometimes we know something is wrong, but we are tempted to do it anyway because we know doing so will benefit us. The small business owner might be tempted to increase their profits by paying their staff below minimum wage. Or your neighbour could be tempted to poison a beautiful old tree that is protected by council because it’s blocking their view.

When we’re faced with temptation, and if we think we can get away with it, it takes willpower to stop us from doing the wrong thing. Yet, all too often, willpower is insufficient to stop us. This weakness of will, called “akrasia” by Aristotle, is one of the main causes of unethical behaviour.

There are two dimensions to weakness of will: the first is desire, which sits in tension with willpower. As such, one way to prevent weakness of will is to cultivate the virtue of self-control. However, it may not be prudent to rely on self-control entirely, given that it’s an all-too finite resource for many of us.

So, the other approach is to reduce temptation. That could mean removing the source of the temptation from our presence, like hiding the chocolate cookies in the cupboard rather than leaving them out on the kitchen table. It can also mean increasing accountability, such as through transparency and oversight. We’re less likely to be tempted to do something wrong if we feel we’re unlikely to get away with it.

2. Moral blindness

All too often, people simply don’t see that what they’re doing is wrong. Like the banker who is so focused on earning a commission that they turn a blind eye to money laundering. Or the manager who doesn’t realise that they keep unfairly promoting staff who have a similar ethnicity to them.

This is moral blindness. Sometimes it might be excusable, like if they had no way of knowing that they were causing harm. But, ignorance is not always an excuse. We must all be mindful of how our actions affect others, and we can’t avoid responsibility if we could have reasonably anticipated that our actions were unethical.

There’s also the problem of wilful obliviousness, which is where we avoid thinking too hard about what we’re doing because, deep down, we know it could be wrong. It’s like refusing to watch an exposé on animal abuse in farms because we don’t want to stop eating meat.

This is also a common phenomenon in workplaces, where workers can become distracted by chasing KPIs or boosting profits, and ethical concerns fall into the background. The Banking Royal Commission found many instances of wrongdoing because many financial institutions had a culture that rewarded sales over all else.

This is the danger of unthinking custom and practice. When people operate in a culture that is highly conformist, with incentives that reward unethical behaviour, they are less likely to reflect on or question whether what they’re doing is ethical.

One way to combat moral blindness is to create a culture of curiosity, where everyone is encouraged to reflect on and openly question their practices as well as the decisions of leadership. Another preventative is for organisations to be mindful of the goals they set and ensure they are not creating incentives to act unethically.

3. External constraint

Sometimes our hands are tied, and we’re forced to do something we know is wrong. In some cases, there might be nothing we can do to avoid the bad outcome, like a police officer who is forced to shoot someone who is threatening other people’s lives. In other cases, it’s because we’re faced with a moral dilemma, like choosing between keeping a promise to a friend or breaking that promise so they can get the help they need.

External constraints can lead to dirty hands, where someone is forced to do something bad to prevent something even worse from happening. In extreme cases, it can also lead to moral injury, which can cause them to lose faith in their own moral core and become detached or despondent.

An obvious way to prevent external constraints from leading to unethical behaviour is to remove the constraints themselves. That could involve anticipating problematic situations before they occur or making sure that people always have options to do the right thing. However, that’s not always possible. If so, then we should recognise that sometimes people do bad things because they had no other choice, which might result in us being more lenient when it comes to punishing them or correcting the behaviour.

Another way to deal with the problem of external constraints is to cultivate moral courage and moral imagination. Bolstering moral courage makes it easier for people to do the right thing, even when they know doing so might come at a cost. Moral imagination, on the other hand, helps people to expand their possible range of actions, and the chance they might find a way to get around the constraints.

4. Ethical disagreement

When an activist throws paint at a beloved artwork to protest the impact of fossil fuels on climate change, or your local childcare centre refuses to accept children who have not been vaccinated, you might think they’re doing something wrong, even though they are doing what aligns with their deepest moral principles.

We live in a highly diverse world, with countless different moral perspectives and multiple ethical frameworks to guide our behaviour. Until such time that humanity can come together and agree on a common set of values and principles to direct everyone’s behaviour, then ethical disagreement will persist.

One of the compromises we make to live in a liberal society is that we will tolerate some behaviour we believe is unethical, as long as others tolerate our behaviour that they consider to be unethical. Of course, there are limits to tolerance, but it means there will inevitably be cases where two different moral perspectives will clash. The danger is that it’s very easy to judge someone as being a bad person when they are actually acting out of an ethical motive.

This is not to say we can’t criticise them for doing it. Instead, the existence of ethical disagreement highlights the need to create spaces for people to engage with diversity in a safe and constructive way, and to know when we should tolerate or oppose someone else’s actions. If we’re able to recognise that someone is acting out of principle rather than malice, we might engage with them differently compared to going straight to condemnation or punishment.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

So your boss installed CCTV cameras

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

READ

Business + Leadership

Meet James Shipton, our new Fellow uncovering the ethics of regulation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY Dr Daniella J. Forster John Neil 24 JUL 2025

Society asks our teachers to juggle a range of morally rich roles: mentor, motivator, counsellor, disciplinarian, social worker, colleague, and even co-parent – all while guiding academic growth. Arguably the most important of these is being a role model of integrity.

Integrity is more than a momentary choice; it is a core around which personal identity is woven. Personal integrity shows up in daily promises we keep to ourselves – whether finishing a lesson plan after hours or practising a skill no one else will see.

Moral integrity, philosopher Lynne McFall argues, “consists in standing fast by the principles that define who we are”, even when convenience tempts us to drift. In classrooms, those twin forms of integrity are non-negotiable: professional codes embed them, students sense them, and communities scrutinise them. When public trust wavers, integrity is the educator’s most persuasive lesson.

Daniella Forster teaches teachers, and for many of her students, teaching will be more than a job – it’s a calling rooted in a commitment to make a difference for young people. This sense of purpose forms part of teachers’ moral integrity, shaping how they navigate the emotional and ethical demands of the profession. It is also something that can be learned. In class recently, one of Daniella’s pre-service teachers said “I guess as new grad teachers you feel like you can’t speak up, you feel like you don’t have a professional judgment, like you are not qualified enough, or you don’t have enough experience to make your own decisions. But no, you have a responsibility to protect your own integrity and be able to speak up for yourself.”

The multiple overlapping ethical responsibilities teachers are asked to fulfil create complex relational obligations that can challenge their personal boundaries and values. For example, a teacher in an under-resourced community may feel powerless to support students lacking essentials like books, food, or stability. Systemic issues, like poor funding and overcrowded classrooms, can leave them frustrated and guilty for falling short of their moral duty to provide quality education and care.

Enter EdEthics – a growing field that supports educators in confronting ethical dilemmas, much like bioethics does for healthcare. EdEthicists help shape ethical school cultures, guide policy, and offer moral clarity in times of crisis. During the pandemic, Daniella was part of a team of EdEthicists who offered teachers from seven countries guided discussions about the pressures they were facing and how they grappled with exacerbated moral challenges. Teachers expressed their relief in finding ways to interpret and articulate their ethical responsibilities and values and surface underlying assumptions that were examined more closely.

As education evolves, so too must our understanding of the ethical landscape teachers navigate daily. Strengthening moral reflection and support systems isn’t just good practice – it’s essential for a resilient and values-driven education system.

Moral psychology teaches us that knowing the right path doesn’t guarantee we’ll follow it. Most of us can recall a moment when we acted against our own standards and felt the sting of regret – sometimes only after seeing the fallout for others. Psychologists call the deeper wound moral injury: a breach that “ruptures one’s sense of self and leads to moral disorientation”. Moral injury strikes when circumstances push a person to betray their core values, fracturing the very integrity that guides action. It particularly faces teachers when they feel forced to act against their moral and professional identity. Teachers often face this strain when professional values collide, especially when policies offer little clarity on what should take priority .

A unique form of “teacher distress” according to researcher Doris Santoro is ‘demoralisation’, which occurs when teachers are no longer able to receive moral rewards such as when they can “believe that their work contributes to the right treatment of … their students”. Those who have a “strong sense of professional ethics are more likely to experience demoralisation than teachers who have a more functional approach to their work”. Demoralisation means some of its most vocationally committed teachers leave the profession, but there are ways to resist.

While teachers are primarily tasked with building meaningful relationships to support student learning, they work alongside professionals whose ethical priorities differ – school counsellors, learning support and administrators for instance. These colleagues may prioritise student wellbeing, compliance or test performance, creating tension in decision-making and collaboration. It can be a challenge, too, to raise moral uncertainty with colleagues, or to burden them with our concerns, and find safe spaces to talk with them about sensitive issues.

Moral emotions are one of the primary lenses through which teachers view their workday. Feelings such as gratitude, inspiration, pride – and on the darker side, anger, contempt, disgust, guilt, and shame – shape what we notice and how we judge it. These snap judgments crystalise into moral intuitions that steer classroom decisions in an instant. Shame plays a particularly potent role in moral injury. Where guilt condemns an action, shame condemns the self, making it a powerful catalyst for moral injury when educators feel forced to act against their principles.

It’s crucial that teachers develop expertise in how to identify and address ethical issues common in education and establish structured, collegial spaces for deeper reflection. It is difficult to do this during a school day, but important for self-care and the care of colleagues. Making space for safe, ethically guided dialogue along with the development of skills in identifying and responding to ethical issues in the profession is crucial.

What we wish to see is moral repair. When something feels off or goes wrong, it’s easy to jump straight into fixing the problem. But sometimes, what looks like a simple issue is actually part of something deeper. Undertaking moral inquiry can support moral repair. Asking ‘what went wrong?’ both reflectively and verbally with others as a form of interpersonal thinking, questioning assumptions and shared inquiry is a way to create an opportunity to reconstruct one’s habits and the structures which create harm.

Moral injury is not solved by becoming more resilient to factors causing stress at work. Rather, if teachers were to become more resilient to moral injuries against their professional values, this is likely to look like cynicism, defeat and moral detachment – resulting ultimately in ‘demoralisation’. Turning to EdEthicists – specialists in educational ethics – can help schools move away from harmful policies and toward practices that align with teachers’ living moral values. Their guidance supports educators in maintaining integrity, and the work of moral repair – finding a refreshed moral centre from which to teach.

Renewal begins by creating space for collective moral reflection. Creating structured, collegial spaces – after-school ethics circles, reflective supervision using ethical metalanguage and tools, teasing out case studies, or peer-mentoring sessions – where teachers can surface uncertainties and re-examine difficult moments without fear seeds the conditions for renewal and grows ethical confidence in the profession to navigate moral complexity.

If you are a teacher or educator interested in participating in a co-design process to develop professional learning to address moral injury, contact us at learn@ethics.org.au

BY Dr Daniella J. Forster

Dr Daniella J. Forster is an educational ethicist, researcher, and teacher educator with qualifications in philosophy and as a secondary teacher at the School of Education, University of Newcastle, Australia. An Australian leader in normative case study methodology, professional codes and moral dimensions of teaching, with a concern for education’s role in strengthening justice. Current 2025-2026 ADVANCE Research Fellow. Vice President of the Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia and Advisory Board member of Primary Ethics. Visiting Fellow with Justice in Schools/Ed Ethics at Harvard Graduate School of Education.

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

This tool will help you make good decisions

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

‘Woke’ companies: Do they really mean what they say?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethical redundancies continue to be missing from the Australian workforce

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Anna Goodman 1 JUL 2025

Young people can often feel torn between the desire to find or start a good job that is financially rewarding while striving to make a positive impact in the world. How should we aim to prioritise the balance between investing in ourselves, our skill sets, and what we feel the world needs?

In 2023, I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in philosophy. For most of the first part of my life, my identity centered around learning and being a student. I spent my days in class, reading and writing, and discussing with my close friends about how we wanted to make the world a better place.

Figuring out what I wanted to do after university was a challenge. I knew what I cared about: making sure I continued learning, having opportunities to experience different industries while working with lots of different people, and earning enough money to be able to live well (and maybe save a little). Outside of work, I knew I wanted to be in a place where I would continue to grow to become a true, happy version of myself.

Now two years out of university, I have spent one of those years working as an analyst at a consulting firm. While it is hard work, I’m reaching my career goals of working in different industries, receiving a high investment in training, and earning enough to be a renter in Sydney.

During Christmas break in 2024, about nine months into full time work, I hit a natural point of reflection. Slowing down gave me time to think about what I really wanted from work, and life. I had been working some pretty long hours (as is common in many graduate jobs), and I started to think about what felt worth it to me.

Moral guilt started to creep in, as I began to wonder if I should be spending my time trying to do something more aligned with what I learnt at university and having a career with more purpose. However, with a challenging job market and the continuously rising cost of living, my “logical” brain wonders if it is the right time to make a career move.

So, how can we think about these big career and life decisions in a clear, methodical way?

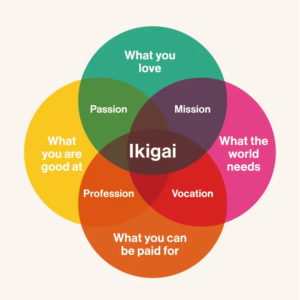

Ikigai and finding our purpose

It’s hard to distill anything as vast and complex as “work in general” or “life in general” using a simple, one-dimensional framework. That being said, it’s not a new question to ask and reflect on what constitutes meaning in our work and in our lives.

One way we can start to unpack this tension is using the Japanese concept of ikigai – translated roughly to “driving force”. Writers Francesc Miralles and Hector Garcia published their book Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life in 2016, after spending a year travelling around Japan. They interviewed more than 100 elderly residents in Ogimi Village, Okinawa, a community known for its longevity, and one thing that these seniors had in common is that they had something worth living for, or an ikigai.

Ikigai can be summarised into four components:

- What you love

- What you are good at

- What the world needs

- What you can get paid for

Asking these questions can get us closer to understanding what intrinsically motivates us and what gives us our reasons for waking up in the morning. Garcia recounts from his interviews with elderly residents in Okinawa: “When we asked what their ikigai was, they gave us explicit answers, such as their friends, gardening, and art. Everyone knows what the source of their zest for life is, and is busily engaged in it every day.”

Reading this, I can’t help but wonder if these answers are a simplification for argument’s sake. Striking a balance between earning enough money to do what I love in my free time (while also paying my bills) and doing something good for the world feels really challenging.

So, how can we make this framework feel more attainable for young people today?

Narrowing the scope

Something I was regularly told as I was applying to graduate jobs was that no one’s first job is perfect. In general, this can be a helpful premise, especially given our interests, circumstances, and contexts can change significantly over time.

One of the ways I began to feel less overwhelmed is by narrowing the ikigai questions around what gives my life meaning to what is giving my life meaning right now. It’s hard to see how I can make a positive contribution to the world through my work, unless I build up skills and knowledge over time that will allow me to have that impact.

For example, when I ask questions about what I love and what I am good at, these answers have changed substantially through my years of formal education and now as a worker. Right now, I have a set of skills I’m good at, however, these will evolve throughout my life and so will my enjoyment of them. In the short term, I enjoy the skills in research, analysis, and problem solving that my current job offers, because I know these are getting me closer to my long-term goal of being able to think pragmatically about key global issues and how we might be able to work to solve them. So, maybe it isn’t always helpful to ask the question “what am I good at” without also asking how this has changed, and how this might continue to change.

As young people, we’re changing and growing up in a world that feels unpredictable and unstable. Technology, culture, politics, economics, and the climate are almost unrecognisable from 10 or 15 years ago. It makes sense that trying to answer our four pillars of ikigai are challenging questions to try and answer if we’re thinking about a time span that gets us through most of our adult lives.

We need ethically minded people in all parts of the world, learning skills and becoming versions of themselves they are proud of. While our jobs are important in teaching and helping us figure out where in the world we want to go, we are more than the work that we do, and our careers, lives, and interests will almost certainly continue to evolve.

Part of graduating is realising that there is a whole wide world of options. This can be liberating and exciting, as well as stressful and overwhelming. By focusing on the “right now” – with regards to what we want, what suits our skills, and what the world needs – hopefully we can begin to wade through the complexities of post-grad life and start to carve a path that is fulfilling, fun and good for society.

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Bondi massacre: A national response

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A win for The Ethics Centre

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureBusiness + Leadership

BY Tim Dean 19 MAY 2025

Arts organisations need to strengthen their ethical decision making and communication if they’re to avoid getting caught in controversy.

Which value should arts organisations prioritise? Artistic expression? Or the creation of safe and inclusive spaces, free from divisive issues and the possibility of offence? They often have to choose one because it’s impossible to prioritise both.

Yet, rightly or wrongly, arts organisations are facing demands that they promote both values, with some voices calling for them to prioritise safety at the expense of expression. The sheer impossibility of attempting to satisfy both values – or at least not failing in one of them and triggering a costly backlash – must be keeping the leaders of arts organisations across the country up at night.

There has always been an inherent tension between the values of artistic expression and safety (broadly defined), so there will inevitably be situations where maximising one will compromise the other. Push expression to the extreme and art can be dehumanising or promote hatred. Push safety to the fore and art would lose its power to challenge dominant narratives. This is why the arts have always had to balance the two, often leaning in favour of artistic expression, but with red lines that make things like bigotry or hate speech off-limits.

The challenge today is that we live in an increasingly fractious, polarised and volatile environment, where issues such as the conflict in Gaza are dividing communities and eroding trust and good faith. Where, in times past, onlookers might have treated an ambiguous artwork with charity, now they see endorsement of terror. Where an artist might once have been forgiven for making an off-hand remark in support of a humanitarian cause they believe in, they are now interpreted as promoting hate. This milieu has contributed to many voices – often powerful voices – calling to lower the bar for what is considered “unsafe” and, as a result, seeking to overly constrain expression.

How are arts organisations to continue to fulfil their mandate in such an environment? Given that the issues facing them are fundamentally ethical in nature, the answer comes in strengthening their ethical foundations. One way of doing that is formally adopting a clearly articulated set of values (what they think is good) and principles (the rules they adhere to) that become the sole standard for judgement when individuals make decisions on behalf of their organisation.

Couple that with robust processes for engaging in ethical decision making, and the organisation benefits from making better decisions – and avoiding hasty ones driven by panic or expedience – and is also better able to justify those decisions in the public sphere. There might still be some who criticise the decision, but even a cynic will be forced to acknowledge the consistency and integrity of the organisation.

Of course, arts organisations are not monolithic entities. Leaders and staff will inevitably vary in what they personally think is good and bad or right and wrong. And while individuals have a clear right to decide whether or not they will work with or support a particular organisation, no person can impose their own personal values and principles on those they work with. So, organisations need to have internal processes that allow this diversity to be acknowledged, while arriving at a single set of values and principles that can guide the organisation’s decisions.

And they need to do this without allowing “shadow values and principles” to subvert them. Many organisations have a lovely list of words pinned to the wall or splashed across the ‘About’ page on their website. But their internal culture promotes a different set of values by rewarding or punishing certain behaviours. As a result, it’s possible for an organisation to say it prioritises artistic expression but its actions show it values the patronage of wealthy supporters more, and it’s willing to compromise the former to satisfy the latter.

A truly ethical organisation will be self-aware enough to recognise shadow values and principles when they emerge, and a truly enlightened leadership will be able to redirect the culture towards promoting their stated values and principles.

All of this requires work. But it can be done. I have seen it first hand. I’ve worked with multiple arts organisations to help them better understand the values and principles that they wish to promote, and workshopped a range of scenarios to put its decision making processes to the test.

What would they do if an artist they’ve programmed posts something inflammatory on social media a week before they’re scheduled to perform? What if it was a controversial work from a decade ago? What are the red lines in terms of expression and what are they willing to defend? What would they do if a high-profile donor threatens to pull funding if they don’t deplatform an artist they object to? How should they treat an artist who uses the platform they’ve been given by the organisation to make a political comment unrelated to their work?

The organisations I’ve worked with have answers to these questions. The answers might not satisfy everyone, and they might involve compromises, but they are consistent with the values and principles that drive the organisation.

There may be no single correct answer to many of the ethical challenges that arts organisations face, but there are better and worse answers. Having a robust ethical framework and decision making processes won’t make arts organisations immune to controversy, but it will help them avoid much of it, and enable them to respond with integrity to whatever comes their way.

If you’re an individual or an organisation facing a difficult workplace decision, The Ethics Centre offers a range of free resources to support this process. We also offer bespoke workshops, consulting and leadership training for organisations of all sizes. Contact consulting@ethics.org.au to find out more.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

In the court of public opinion, consistency matters most

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

5 dangerous ideas: Talking dirty politics, disruptive behaviour and death

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Leaders, be the change you want to see.

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Paula McDonald 7 MAY 2025

US President Donald Trump declared earlier this year he would forge a “colour blind and merit-based society”.

His executive order was part of a broader policy directing the US military, federal agencies and other public institutions to abandon diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

Framing this as restoring fairness, neutrality and strength to American institutions, Trump argued DEI programs “discourage merit and leadership” and amounted to “race-based and sex-based discrimination”.

In Australia too, debates over gender quotas and “the war on woke” have repeatedly invoked meritocracy as a rallying cry against affirmative action.

The narrative of rewards going to the most qualified people is compelling. Yet decades of research show this is flawed. Far from being the great equaliser, an uncritical reliance on “merit” can perpetuate bias and inequality.

The myths of meritocracy

The merit rhetoric invokes the ideal of a neutral, objective system rewarding talent and effort, regardless of identity.

In theory, merit-based evaluations such as exams, performance reviews, employee recruitment processes and competitive bids, should be impartial.

In practice however, there are several myths associated with the notion of merit.

1. Merit is purely objective or unbiased

In the employment context for example, studies show that even so-called objective and standardised cognitive or aptitude tests can systematically favour men due to the type of questions asked.

Decision-makers may unknowingly redefine merit to fit whoever already belongs to a favoured group. A study of elite law firms, for example, found male applicants were rated as more qualified than identical resumes from women.

This is known as “plasticity of merit”, meaning the criteria of excellence can bend to preference, all while appearing objective.

Supposedly merit-based judgments can reflect unconscious bias, or comfort with candidates who fit a traditional mould. Over time, preference may be given to a particular type of candidate irrespective of their actual contribution. Privilege and prejudice can be baked into merit-based evaluations.

2. Merit can be separated from social and historical context

Meritocracy or the so-called meritocratic promise assumes a level playing field, where everyone competes under the same conditions.

In reality however, past inequalities shape present opportunities. What counts as merit is dynamic and socially shaped, not an eternal universal standard.

For example, during the second world war there was a shortage of male workers. Qualities women brought to jobs previously held by men such as capacity for teamwork were suddenly deemed meritorious. But these same qualities were downgraded when the men returned.

Merit is often defined in masculine terms. For example, physicality or hyper-competitive traits have long been seen as prerequisites for military service and policing.

This alignment of masculine norms with standards of merit has been termed “benchmark man”.

Science careers too were built in an era when women were largely excluded. They were predicated on long-hours work and total availability – requirements that clash with caregiving responsibilities. The result is women in STEM careers leave or are pushed out.

3. Outcomes are the result of personal choice or deficiencies, not structural barriers

Meritocracy carries a moral narrative: those at the top earned their place while those left behind didn’t measure up or chose not to compete.

Research shows, for example, that when women don’t advance, it’s explained as lifestyle choices, or they lack ambition, or have opted out to prioritise caregiving.

This narrative wilfully overlooks the structural constraints impacting choices. When a woman “chooses” a lower-paying, flexible job, it may be less about preference than inadequate social supports.

By accepting unequal outcomes as the natural result of individual choices, institutions can conveniently obscure disadvantage and discrimination and erase responsibility to correct inequities.

How the merit mandate undermines equality

Trump’s vision is to remove equity initiatives and programs that monitor or encourage fair hiring and promotion, cease training that alerts employees to hidden biases, and fire or reassign DEI staff.

This is conceptually flawed and will actually entrench the very biases and barriers that have kept institutions unequal.

In the military, for example – an area highlighted by Trump – leaders have recognised they need to foster more inclusive cultures.

For years, defence forces have grappled with sexual harassment, recruitment shortfalls and retention of skilled personnel. In Australia, the Australian Defence Force undertook major reviews to identify violent and sexist subcultures, understanding a more inclusive force is a more effective force.

Yet Trump’s order bars the Pentagon from even acknowledging historical sexism in the ranks.

Favouring the in-group

Removing equity measures under a banner of neutrality means hiring and promotion will increasingly rely on informal networks and subjective judgements. These can tilt in favour of the in-group – usually white, male and affluent.

DEI initiatives can increase representation of women, or people from diverse racial or cultural backgrounds, in an organisation or occupational group.

However, without challenging the norms of merit, or without broadening the definitions of talent and leadership, people in those groups may continue to feel like outsiders.

Australian experts and business leaders increasingly acknowledge objective merit is mythical.

Redefining merit

Fair rewards for effort can improve performance. However, we need to stop pitting merit against diversity. True fairness requires acknowledgement structural inequality exists and bias affects evaluations.

Organisations need to re-imagine merit in ways that work with inclusion, rather than against it. This includes refining hiring and promotion criteria to focus on competencies that are measurable and relevant.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

BY Paula McDonald

Paula McDonald is Professor of work and organisation and Director of the Work/Industry Futures Research Program in the QUT Business School. Prior to an academic career, Paula held clinical and research roles in health sector settings including child and adolescent psychiatry, medical education, primary care and public health. She is a registered psychologist with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Money talks: The case for wage transparency

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Constructing an ethical healthcare system

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Office flings and firings

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker 14 APR 2025

“We’re in this together” is easy to say, but much harder to do – especially when people’s livelihoods, land, and the planet’s future are at stake.

Australia is committed to reducing emissions and shifting to renewable energy. However, for many rural and regional communities – particularly those tied to coal, gas, or agriculture, they sit at the crossroads of opportunity and uncertainty. These areas are rich in culture, industry, and community and are also heavily shaped by commercial imperatives – the need for jobs, services, and sustainable growth.

Unfortunately, climate action can feel more like an impending threat than a shared opportunity. These communities often experience change as something done to them, rather than with them.

Bridging this gap demands more than just policy and technology. Climate change is one of the biggest challenges of our time, but tackling it isn’t just about switching to solar panels or building wind farms either. It’s about ethical cooperation – a commitment to fairness, transparency, and shared responsibility in how we plan and implement climate solutions. If not done ethically, commercial development can disrupt local culture, raise living costs, and put pressure on fragile ecosystems.

At its heart, cooperation is about shared goals. But in climate policy, those goals don’t always look the same to everyone. For city campaigners, a ‘just transition’ means phasing out coal and gas. For a local worker in Gladstone or the Hunter Valley, it might sound like job losses without a safety-net.

Different philosophical perspectives can help us to understand how we can apply ethical cooperation as we pursue our shared goals. Whether it’s about consequences, duties and obligations, or people’s rights, all are underpinned with the values and principles of transparency, fairness, and mutual respect and dignity.

‘Just transition’ sounds good, but what does it mean in practice? As researchers Marshall and Pearce put it: “Many people in regional communities have no concrete understanding as to what a ‘just transition’ refers to and do not find it to be authentically their syntax”.

The proposed Hunter Transmission Project in NSW, for example, has been met with strong resistance from landowners. While the project is intended to support clean energy infrastructure, many locals say the process lacked transparency and ignored community concerns about land use, agriculture, and environmental impacts.

British philosopher Onora O’Neill focuses on trust and consent in cooperative systems. She argues that ethical cooperation requires conditions where all parties have genuine capacity to consent, particularly in asymmetrical relationships (e.g. government vs local communities). These principles have been embedded in The Clean Energy Council’s national guide which advises that developers must prioritise “clear, accessible and accurate information” and ensure projects are co-designed with communities to reflect cultural, economic and environmental priorities.

When AGL closed Liddell Power Station in 2023, the company committed to a transition plan. But many workers reported uncertainty and a lack of clarity about what would come next. For a transition to be truly ‘just’, it needs to include more than retraining promises. It needs local job pipelines, early engagement, and co-designed solutions.

Israeli philosopher Yotam Lurie says that once people engage in joint activity, they take on moral obligations to each other. In the case of climate action, that means governments, industries and communities must not only work together, but they must also do so with care, trust, and respect.

Rural resistance often stems from real economic vulnerabilities and perceived exclusion from decision-making, not from climate denial.

Encouragingly there are areas where we are seeing ethical cooperation working well.

In Gippsland, Victoria, the Gunaikurnai people are working with renewable energy developers to co-design solar projects. These partnerships embed cultural knowledge, ensure local employment, and protect Country showing that ethical cooperation isn’t just a principle. It’s a practical strategy for success.

The First Nations Clean Energy Network has also shown how co-owned and co-designed projects can reduce costs, build trust, and deliver long-term economic and environmental benefits.

Climate change is often framed as a technical problem. But it’s also a human one. If we want a sustainable future, we must build it together with ethics, empathy, and equity at the centre.

As Australian philosopher, Peter Singer suggests, we are morally obligated to reduce the suffering of others which would support a coordinated action where affluent corporations aid vulnerable groups, such as rural or Indigenous communities affected by the energy transition.

Governments and companies have a responsibility to fund and support this process. That includes advisory boards, transparent impact assessments, and long-term partnerships built on trust.

If we want rural and regional communities to lead rather than lag in the net-zero transition, we need to take ethical cooperation seriously and build trust within the human system. Sometimes the hardest part is putting aside self-interest, regardless of the good intent and work together to understand the shared purpose. Acknowledging the tensions and being honest about the trade-offs is a strong place to start. This can be done through deep listening and ‘story telling’ that demonstrates respect for cultural and ecological values, rather than just economic ones.

Tackling climate change is not just about reducing emissions, it’s about justice and fairness, because “we’re in this together” only works when everyone has a say, and everyone has a stake.

The Energy Charter is a member of the Ethics Alliance and a one-of-a-kind, CEO-led coalition of energy organisations united by a shared passion and purpose: delivering for customers and empowering communities in the energy transition.

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The role of ethics in commercial and professional relationships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Feeling rules: Emotional scripts in the workplace

Feeling rules: Emotional scripts in the workplace

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY Elena Walsh 26 FEB 2025

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg recently lauded the virtues of company cultures that can ‘celebrate the aggression’. The comment sparked backlash, with many commentators arguing that ‘no one thrives in an aggressive environment’ and that anger and pride have no place at work.

There are many reasons this topic is highly charged. One is that people, on the whole, tend to dislike being told what to feel (even more than they dislike being told what to do).

The aversion is not difficult to explain. Long before the development of the neocortex, our ancestors relied exclusively on the limbic brain, which prompted fast, instinctive responses to a quickly changing and often treacherous physical and social landscape. We fought in anger, ran from danger in fear, and withdrew in disgust from contaminated food. We used our emotions to navigate the world and express our needs, which kept us alive. So to be told not to feel what we feel, and act accordingly can be perceived as a threat to our ability to act adaptively to life. And it is this adaptive ability that constitutes, in part, our sense of being autonomous and free.

And yet, as we mature, we learn to reign in our emotions for the sake of the collective. We live and operate within workplaces and other social institutions that ask us to limit our emotional repertoire to support the collective. Freud thought the laws binding civilised societies required us to ‘sacrifice [our] instincts’, in order to ‘leave no one […] at the mercy of brute force’. Civilisation is a trade-off: it imposes necessary restrictions on freedom that no-one can escape, in turn offering protection from harm and mutual reciprocity.

So, what emotions should we express in the workplace? And should we suppress spontaneous emotional expression in order to conform to emotional scripts?

An emotional script is a bit like a script for a scene in a play. It prescribes a set of emotions appropriate to a given workplace culture, setting, or situation, and asks us to play the role. A basic ‘professionalism’ script, for instance, which exists in most workplaces, asks employees to remain calm and composed, regardless of stress or frustration.

Many workplace scripts have obvious value, such as the script for showing appreciation and gratitude after someone gives a presentation, or using warm salutations in an email.

Others carry potential for harm. The ‘customer-facing pleasantness’ script demands frontline staff treat customers in a friendly and accommodating way, regardless of their true feelings. Many companies train and require frontline workers to display smiles when with customers, some even insisting that these smiles be ‘real’ and not fake. The demand to show a ‘real’ smile whenever interacting with a customer, even if they are rude or aggressive, demands significant emotional labour. Constantly suppressing true emotion to conform with an emotional script is, in essence, method acting. It takes energy.

We can all engage in (and perhaps even enjoy) some method acting from time to time. But too much leads to burnout and, in severe cases, can harm mental health. The British paediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott used the term ‘false self’ to describe rigid and pervasive patterns of emotional masking in which a person loses track of the difference between their ‘real’ self and their mask. Winnicott thought the false self was an adaptation to traumatic early caregiving environments in which genuine emotional expression was unsupported or punished, leading individuals to develop a protective façade.

Of course, masking in the workplace as an adult is much less harmful, both because a mature adult is less vulnerable than a child, and also because an adult can ‘take off’ their mask when they leave work.

Nonetheless, excessive emotional labour can still cause harm, and studies of marginalised groups in the workplace attest to this. Many studies show that women are often expected to conform to a ‘nurturing and motherly’ emotional script when interacting with male colleagues or bosses.

Another well-studied phenomenon is the pressure faced by Black men and women to repress their anger, even in situations that clearly warrant it, in order to not conform to the stereotype of the ‘angry Black man [or woman]’. Studies have found that Black women frequently experience traumatic stress symptoms in the workplace due to the strain of conforming to emotional scripts that forbid anger and encourage nurture. These are consequences of the felt need to mask too often and too well, even whilst experiencing microaggressions or more blatant forms of discrimination. Studies have also shown that workplaces that encourage traditionally ‘masculine’ traits are tied to burnout, high worker turnover, anxiety, and poor wellbeing in both male and female workers (and regardless of race).

Balancing the script

While some degree of emotional restraint might be necessary, it seems that too much can be harmful. How do we draw the line?

Freud’s claim that a healthy suppression of ‘instinct’ helps avoid ‘brute force’ was meant to describe how civilisation overcame the philosophy of ‘might makes right’. This philosophy claims that the basis for morality and social order is rightly and naturally set by the most powerful, not by principles of goodness, justice, or fairness. In other words, Freud thought that a reasonable amount of emotional repression would lead to mutual reciprocity and fairer outcomes, overcoming the domination of the less powerful by those with more.

In fact, the ‘professionalism’ script, understood in its original twentieth-century sociological sense, was not simply a common and expected workplace convention. Rather, it was seen as a powerful means to increase the stability and civility of social systems.

One answer, then, is that emotional repression is good when it supports ideals of justice and fairness, and not when it perpetuates oppression and marginalisation of individuals or groups.

Finding balance might require assessing situations as they arise, with an eye for whether individuals are being treated equally and fairly. This vigilance is important, given that we are in an age where more workplaces are beginning to explicitly prescribe emotional scripts, as well as conduct surveillance to ensure compliance.

An emotional script may be, in the end, a poor person’s substitute for true emotional intelligence, which provides us with the ability to flexibly deviate from and conform to prescribed scripts dependent on the situation at hand, and with a genuine concern for the common good. Acquiring this skill is difficult for all of us, but likely surpasses the rigidity of any single emotional ideal.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Workplace ethics frameworks

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

The road back to the rust belt

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Between frenzy and despair: navigating our new political era

BY Elena Walsh

Elena Walsh is a lecturer in philosophy at the University of Wollongong, working across the philosophy of science and the science of emotion. She also has expertise in moral psychology and Buddhist and Asian philosophical traditions. Her current research examines the role of emotion in intelligent systems and the ethical governance of AI. Elena completed her PhD at the University of Sydney in 2020 and has previously held roles as a policy advisor for the NSW Department of Premier and Cabinet and as a researcher at UNSW’s Practical Justice Initiative.

The near and far enemies of organisational culture

The near and far enemies of organisational culture

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY John Neil 13 FEB 2025

While an organisation might be judged by its profitability or reputation, it is ultimately defined by its culture.

Culture influences everything: individual and team performance, change management, and how the organisation navigates complexity and uncertainty. And when companies face ethical scandals or breaches, the root cause is often be traced back to cultural issues.

Culture isn’t just about employee engagement; it’s about how an organisation functions at its core. Yet culture is notoriously difficult to define and measure. Turning to traditional methods like employee surveys, pulse checks, or 360-degree reviews can be insightful, but they rarely provide a complete picture. A more profound understanding lies beneath the surface by identifying and understanding the role an organisation’s “shadow values” play in shaping their culture. These are the implicit, unspoken attitudes and beliefs that profoundly influence behaviour, often in ways that are not immediately apparent, but which are often key drivers that explain the ethical challenges an organisation experiences.

Shadow values: The invisible force shaping culture

By recognising and understanding shadow values, organisations can make meaningful improvements, aligning both individual and collective behaviours with the company’s goals.

Corporate values, such as collaboration, integrity, or innovation, are stated, documented, and promoted. However, even companies with admirable stated values can experience significant ethical failures due to the existence of implicit, shadow values that run counter to their formal values.

At their worst, shadow values and principles run in opposition to official values. At their best, shadow values provide a nuanced expression of what an organisation actually values. Either way, they are an essential element of identifying and measuring an organisation’s actual operating culture.

The positive side of shadow values and principles can be demonstrated by a financial services company The Ethics Centre worked with where “putting members first” was identified a shadow principle. This principle was so deeply embedded that when employees faced ambiguous situations where decisions and actions weren’t guided by clear policies or procedures, they defaulted to acting in the best interests of their members, even though this value was not formally part of the organisation’s stated principles.

On the other hand, shadow values and principles can also have a negative impact on an organisation’s culture. Another company we worked with had the common shadow principle of ‘shareholders matter most.’ As a publicly listed company providing essential services, providing value and managing and responding to multiple stakeholders was part and parcel of day-to-day business. However, this shadow principle become a default when trade-offs invariably had to be made between various stakeholder interests. This engendered a high level of cynicism and disaffection with staff who heard a lot about the importance of customer service and the value of staff but other actions – workload, resourcing, remuneration, and informal communication from managers – led them to infer that they existed only insofar as they met shareholder’s interests.

Near and far enemies: A Buddhist lens

To better understand and identify the impact of shadow values and principles on an organisation’s culture we can borrow the concepts of near and far enemies from Buddhism.

In Buddhism, the Four Brahmavihārā (compassion, loving-kindness, empathetic joy, and equanimity) represent the highest virtues humans should cultivate. Each of these virtues has a “far enemy,” which is an obvious opposite, and a “near enemy,” which closely resembles the virtue but is actually a distortion.

For example, the far enemy of compassion is cruelty – easily identifiable and universally understood as negative. And because it is easily identifiable and its manifestations and impact are readily recognised, it can be directly addressed.

The near enemy, however, is pity. Pity masquerades as compassion, superficially appearing to embody the traits of compassion. However, this is only a superficial resemblance as pity creates a sense of distance or condescension, because it stems from feeling sorry for someone rather than genuinely empathising with their experience. Pity lacks the connection and motivation to act that true compassion entails.

The near enemies in organisational culture

This concept of near and far enemies is incredibly helpful when diagnosing the shadow values that can function as root causes of organisational culture failings.

Just as it is in the case of the Brahmavihārā, while the far enemies of a company’s values are easy to spot and address, the near enemies are more insidious, because they masquerade as positive behaviours, and as such they exercise a disproportionate impact on people’s decision making and actions.

In an organisation The Ethics Centre worked with, “collaboration” was codified as a core company value. The far enemy of collaboration is competition, which is relatively easy to identify. If employees begin hoarding information or undermining one another, it’s clear that competition has taken root, supplanting the value collaboration and steps can be taken to address it.

However, competition wasn’t the root challenge for this company; it was harmony, a near enemy of collaboration. While harmony seems positive, it can manifest as a reluctance to engage in constructive conflict or make difficult decisions.

In the case of this company, a large incumbent experiencing organic year on year growth, their strategic challenge was shifting the culture to be one that was more responsive, innovative and adaptable to change. However, harmony as a shadow value was so deeply embedded as a shadow value that employees avoided conflict at all costs. Decisions were often delayed, and consensus-driven processes became bureaucratic, impeding the company’s ability to be agile and responsive to the changing environment and future competitive pressures, with innovative ideas often deferred.

Another example comes from a large financial services firm that codified “excellence” as a core value.

While the far enemy of excellence is easily and readily identifiable as mediocrity, it played little role in explaining some of the foundational ethical challenges the company was facing. Instead, it was ‘success,’ the near enemy of excellence, which was a core driver of cultural misalignment. ‘Success’ can give the appearance of excellence, however while excellence is about high standards of consistent performance and achieving great results through effort and learning, success had a singular focus on achieving results for their own sake, regardless of the means by which those results were achieved.

This near enemy generated a range of systemic organisational challenges including:

- An increasingly competitive internal environment – described by many staff as ‘dog-eat-dog’ resulting in people avoiding senior appointments.

- A proliferation and reliance on individual sales targets/performance payments, which promoted a highly competitive work environment which undermined teamwork and mutual accountability.

- Competing KPI’s that weren’t aligned across the business, undermining integrity in an attempt to get sales or outdo other teams to achieve different KPIs.

- Withholding information for internal competitive advantage – business units across the company did not disclose information or actively withheld it out of self-interest.

Combatting the near enemies

A company’s culture is complex, influenced by both visible and invisible forces. While explicit values like collaboration or excellence are important, it’s the shadow values operating beneath the surface that often have the greatest impact on behaviour. By understanding the near and far enemies of their values, companies can better align their culture with their strategic goals, fostering an environment that supports both individual and organisational success. The challenge lies in identifying these shadow values and addressing them before they become barriers to progress.