People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kate Prendergast 24 APR 2019

It began in Oakden. Or, it began with the implosion of one of the most monstrously run aged care facilities in Australia, as tales of abuse and neglect finally came to light.

That was May 2017. Two years on, we are in the midst of the first Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, announced following a recommendation by the Scott Morrison government.

The first hearings began this year in Oakland’s city of Adelaide. They have seen countless brave witnesses come forward to share their experiences of what it’s like to live within the aged care system or see a loved one deteriorate or die – sometimes peacefully, sometimes painfully – within it.

In May, the third hearing round will take place in Sydney. This round will hear from people in residential aged care, with a focus on people living with dementia – who make up over 50 percent of residents in these facilities.

With our burgeoning ageing population, the number of people being diagnosed with dementia is expected to increase to 318 people per day by 2025 and more than 650 people by 2056.

Encompassing a range of different illnesses, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and Lewy body disease, its symptoms are particularly cruel, dissolving intellect, memory and identity. In essence, dementia describes the gradual estrangement of a person from themselves – and from everyone who knew them.

It is one of the most prevalent health problems affecting developed nations today – and one of the most feared. Contrary to widespread belief, one in 15 sufferers are in their thirties, forties and fifties.

Physical restraints

How do you manage these incurable conditions? How can you humanely care for the remnants of a person who becomes more and more unrecognisable?

One thing the Royal Commission has made clear: you don’t do it by defaulting to dehumanising mechanisms of restraint.

Unlike in the UK or the US, there are currently no regulations around use of restraints in aged care facilities. It is commonly resorted to by aged care workers if a patient displays physical aggression, or is a danger to themselves or others.

Yet it is also used in order to manage patients perceived as unruly in chronically understaffed facilities, when the risk of leaving them unsupervised is seen to be greater than the cost of depriving them their free movement and self-esteem. The problem of how to minimise harm in these conditions is an ongoing and high-pressure dilemma for staff.

Readers may remember the distressing footage from January’s 7.30 Report, in which dementia patients were seen sedated and strapped to chairs. One of them was the 72-year-old Terry Reeves. Following acts of aggression towards a male nurse, he was restrained for a total of 14 hours in a single day. His wife, however, had authorised that her husband be restrained with a lap belt if he was “a danger to himself or others”.

Maree McCabe, director of Dementia Australia, is vocal about why physical restraints should only be used as a last resort.

“We know from the research that physical restraint overall shows that it does not prevent falls,” she says. “In fact it may cause injury, and it may cause death.”

While there are circumstances where restraint may be appropriate McCabe says, “it is not there as a prolonged intervention”. Doing so, she says, “is an infringement of their human rights”.

After the 7.30program aired and one day before the Royal Commission hearings began, the federal government committed to stronger regulations around restraint, including that homes must document the alternatives they tried first.

Restraint by drugging

Another kind of restraint which has come into focus through the Royal Commission is chemical restraint. Psychotropic medication is currently prescribed to 80 percent of people with dementia in residential care – but it is only effective 10 percent of the time.

“We need to look at other interventions,” says McCabe. “The first to look at is: why is the person behaving in the way that they are? Why are they responding that way? It could be that they’re in pain. It could be something in the environment that is distressing them.”

She notes people with dementia often have “perceptual disturbances” – “things in the environment that look completely fine to us might not to someone living with dementia”. Wouldn’t you act out of character if your blue floor suddenly became a miniature sea, or a coat hanging on the door turned into the Babadook?

“It’s about people understanding of what it’s like to stand in the world of people living with dementia and simulate that experience for them,” says McCabe.

Whether through physical force or prescription, a dependence on restraint shows the extent to which dementia is misunderstood at the detriment of the autonomy and dignity of the sufferers. This misunderstanding is compounded by the fact that dementia is often present among other complex health problems.

Yet, and as the media may sensationally suggest, the aged care sector isn’t staffed by the callous or malicious. It is filled with good people, who are often overstretched, emotionally taxed and exhausted.

Dementia Australia is advocating for mandatory training on dementia for all people who work in aged care. This covers residential aged care, but could also extend to hospitals. Crucially, it encompasses community workers, too.

“Of the 447,000 Australians living with dementia, 70 percent live in the community and 30 percent live alone,” notes McCabe. “It’s harder to monitor community care, it’s less visible and less transparent. We have to make sure that the standards are across the board.”

It is only through listening to people living with dementia – recognising that while yes, they have a degenerative cognitive disease, they deserve to participate in the decision-making around their life and wellbeing – that our approach to it has evolved. Previously, people believed that it was dangerous to allow sufferers to cook, even to go out unaccompanied.

Likewise, it is crucial that we continue to afford people with dementia the full rights of personhood, however unfamiliar they may become. Only then can meaningful reform be made possible.

Besides, if for no other reason (and there are many other reasons), action is in our own selfish interest. The chances, after all, that you or someone you love will develop dementia are high.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Kate Prendergast

Kate Prendergast is a writer, reviewer and artist based in Sydney. She's worked at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Broad Encounters and Giramondo Publishing. She's not terrible at marketing, but it makes her think of a famous bit by standup legend Bill Hicks.

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Kym Middleton 21 MAR 2019

Immigration is the hot election issue connecting everything from mismanaged water and mass fish deaths in the Murray Darling to congested cities and unaffordable housing.

The 2019 IQ2 season kicks off with ‘Curb Immigration’ on 26 March. It’s something Prime Minister Scott Morrison promised to do today if re-elected and opposition leader Bill Shorten has committed to considering.

Here’s a collection of ideas, research, articles and arguments covering the debate.

New migrants to go regional for permanent residency, under PM’s plan

Scott Morrison, SBS News / 20 March 2019

Prime Minister Scott Morrison revealed his immigration plan today. He confirmed reports he will lower the cap on Australia’s immigration intake from 190,000 to 160,000 for the next four years. He announced 23,000 visa places that require people to live and work in regional Australia for three years before they can apply for permanent residency. “It is about incentives to get people taking up the opportunities outside our big cities” and “it’s about busting congestion in our cities”, Morrison said.

————

Australian attitudes to immigration: a love / hate relationship

The Ethics Centre, The New Daily / 24 January 2019

You’ll hear Australians talk about our country as either a multicultural utopia or intolerant mess. This article charts many recent surveys on our attitudes to immigration. The results show almost equal majorities of us love and hate it for different reasons, suggesting individual people both support and reject immigration at the same time. We’re complex creatures.

————

Post Populism

Niall Ferguson, Festival of Dangerous Ideas / 4 November 2018

At the Festival of Dangerous Ideas on Cockatoo Island, Niall Ferguson presented his take on the five ingredients that have bred the nationalistic populism sweeping the western world today. Point one: increased immigration. Listen to the podcast or watch the video highlights. Elsewhere, Ferguson points to Brexit and the European migrant crisis and predicts, “the issue of migration will be seen by future historians as the fatal solvent of the EU”.

————

Human Flow movie

Ai Weiwei / 2017

Part documentary and part advocacy, Human Flow is a film by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei that “gives a powerful visual expression” to the 65 million people displaced from their homes by climate change, war or famine. It is not the story of ‘orderly migration’ based on skilled visas or spatial planning policies, but rather, one of mass flows across countries and continents.

————

Government needs to wake up to impact of population boom

PM, ABC RN / 23 February 2018

IQ2 guest and human geographer Dr Jonathan Sobels is interviewed by Linda Mottram on the impact of Australia’s population growth on the continent’s natural environment. He’s not the only person concerned about this. A 2019 study by ANU found 75 percent of Australians agree the environment is already under too much pressure with the current population size.

————

Counter-terrorism expert Anne Aly: ‘I dream of a future in which I’m no longer needed’

Greg Callaghan, The Sydney Morning Herald / 18 November 2016

Dr Anne Aly is a counter terrorism expert come politician with “instant relatability”, according to this feature piece on her. Get to know more about her interesting life and career before catching her at IQ2 where she’ll argue against the motion ‘Curb Immigration’. Aly is the Labor Member for the West Australian electorate of Cowan and first female Muslim parliamentarian in Australia.

————

Event info

Get your IQ2 ‘Curb Immigration’ tickets here

Satya Marar & Jinathan Sobels vs Anne Aly & Nicole Gurran

27 March 2019 | Sydney Town Hall

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

After Christchurch

After Christchurch

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 19 MAR 2019

What is to be said about the murder of innocents?

That the ends never justify the means? That no religion or ideology transmutes evil into good? That the victims are never to blame? That despicable, cowardly violence is as much the product of reason as it is of madness?

What is to be said?

Sometimes… mute, sorrowful silence must suffice. Sometimes… words fail and philosophy has nothing to add to our intuitive, gut-wrenching response to unspeakable horror.

Thus, we bow our heads in silence… to honour the dead, to console the living, to be as one for the sake of others.

In that silence… what is to be said?

Nothing.

Yet, I feel compelled to speak. To offer some glimmer of insight that might hold off the dark — the dark shades of vengeance, the dark tides of despair, the dark pools of resignation.

So, I offer this. Even in the midst of the greatest evil there are people who deny its power. They are rare individuals who perform ‘redemptive’ acts that affirm what we could be. Some call them saints or heroes. They are both and neither. They are ordinary people who act with pure altruism – solely for the sake of others, with nothing to gain.

One such person is with me every day. The Polish doctor and children’s author, Janusz Korczak, cared for orphaned Jewish children confined to the Warsaw Ghetto. At last, the time came when the children were to be transported to their place of extermination. Korczak led his children to the railway station — but was stopped along the way by German officers. Despite being a Jew, Korczak was so revered as to be offered safe passage.

To choose life, all he need do was abandon the children. At the height of the Nazi ascendancy, Korczak had no reason to think that he would be remembered for a heroic but futile death. He had nothing to gain. Yet, he remained with the children and with them went to his death. He did so for their sake — and none other. In that decision, he redeemed all humanity — because what he showed is the other face of our being, the face that repudiates the murderer, the terrorist, the racist…the likes of Brenton Tarrant.

I know that many people do not believe in altruism. They will offer all manner of reasons to explain it away, finding knotholes of self-interest that deny the nobility of Janusz Korczak’s final act. They are wrong. I have seen enough of the world to know that pure acts of altruism are rare — but real. And it only takes one such act to speak to us of our better selves.

We will never know precisely what happened in those mosques targeted in Christchurch. However, I believe that, in the midst of the terror, there were people who performed acts of bravery, born out of altruism, of a kind that should inspire and ultimately comfort us all.

Most of these stories will be untold — lost to the silence. Of a few, we may hear faint whispers. But believe me, the acts behind those stories are every bit as real as the savagery they confronted and confounded. And even when whispered, they are more powerful.

Evil born of hate can never prevail. It offers nothing and consumes all — eventually eating its own. That is why good born of love must win the ultimate victory. Where hate takes, love gives — ensuring that, in the end, even a morsel of good will tip the balance.

You might say to me that this is not philosophy. Where is the crisp edge of logic? Where is the disinterested and dispassionate voice of reason? Today, that voice is silent. Yet, I hope you can hear the truth all the same.

Dr Simon Longstaff AO is Executive Director of The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is modesty an outdated virtue?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe to our pets

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Why sometimes the right thing to do is nothing at all

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Doing good for the right reasons: AMP Capital’s ethical foundations

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 15 MAR 2019

IT entrepreneur Joanne Cooper wants consumers to be able to decide who holds – and uses – their data. This is why Alexa and Siri are not welcome in her home.

Joanne won’t go to bed with her mobile phone on the bedside table. It is not that she is worried about sleep disturbances – she is more concerned about the potential of hackers to use it as a listening device.

“Because I would be horrified if people heard how loud I snore,” she says.

She is only half-joking. As an entrepreneur in the field of data privacy, she has heard enough horror stories about the hijacking of devices to make her wary of things that most of us now take for granted.

“If my device, just because it happened to be plugged in my room, became a listening device, or a filming device, would that put me in a compromising position? Could I have a ransomware attack?”

(It can happen and has happened. Spyware and Stalkerware are openly advertised for sale.)

Taking back control

Cooper is the founder of ID Exchange – an Australian start-up aiming to allow users to control if, when and to whom they will share their data. The idea is to simplify the process so that people will be able to visit one platform to control access.

This is important because, at present, it is impossible to keep track of who has your data and how much access you have agreed to and whether you have allowed it to be used by third parties. If you decide to revoke that access, the process is difficult and time-consuming.

Big data is big business

The data that belongs to you is liquid gold for businesses wanting to improve their offerings and pinpoint potential customers. It is also vital information for government agencies and a cash pot for hackers.

Apart from the basic name, address, age details, that data can reveal the people to whom you are connected, your finances, health, personality, preferences and where you are located at any point in time.

That information is harvested from everyday interactions with social media, service providers and retailers. For instance, every time you answer a free quiz on Facebook, you are providing someone with data.

Google Assistant uses your data to book appointments

With digital identity and personal data-related services expected to be worth $1.58 trillion in the EU alone by 2020, Cooper asks whether we have consciously given permission for that data to be shared and used.

A lack of understanding

Do we realise what we have done when we tick a permission box among screens of densely-worded legalese? When we sign up to a loyalty program?

A study by the Consumer Policy Research Centre finds that 94 per cent of those surveyed did not read privacy policies. Of those that did, two-thirds said they still signed up despite feeling uncomfortable and, of those, 73 per cent said they would not otherwise have been able to access the service.

And, what we are getting in return for that data? Do we really want advertisers to know our weak points, such as when we are in a low mood and susceptible to “retail therapy”? Do we want them to conclude we are expecting a new baby before we have had a chance to announce it to our own families?

Even without criminal intent, limited control over the use of our data can have life-altering consequences when it is used against us in deciding whether we may qualify for insurance, a loan, or a job.

“It is not my intention to create fear or doubt or uncertainty about the future,” explains Cooper. “My passion is to drive education about how we have to become “self-accountable” about the access to our data that will drive a trillion-dollar market,” she says.

“Privacy is a Human Right.”

Cooper was schooled in technology and entrepreneurialism by her father, Tom Cooper, who was one of the Australian IT industry’s pioneers. In the 1980s, he introduced the first IBM Compatible DOS-based computers into this country.

She started working in her father’s company at the age of 15 and has spent the past three decades in a variety of IT sectors, including the PC market, consulting for The Yankee Group, as a cloud specialist for Optus Australia, and financial services with Allianz Australia.

Starting ID Exchange in 2015, Cooper partnered with UK-based platform Digi.me, which aims to round up all the information that companies have collected on individuals, then hand it over those individuals for safekeeping on a cloud storage service of their choosing. Cooper is planning to add in her own business, which would provide the technology to allow people to opt in and opt out of sharing their data easily.

Cooper says she became passionate about the issue of data privacy in 2015, after watching a 60 Minutes television segment about hackers using mobile phones to bug, track and hack people through a “security hole” in the SS7 signaling system.

This “hole” was most recently used to drain bank accounts at Metro Bank in the UK, it was revealed in February.

Lawmakers aim to strengthen data protection

The new European General Data Protection Regulation is a step forward in regaining control of the use of data. Any Australian business that collects data on a person in the EU or has a presence in Europe must comply with the legislation that ensures customers can refuse to give away non-essential information.

If that company then refuses service, it can be fined up to 4 per cent of its global revenue. Companies are required to get clear consent to collect personal data, allows individuals to access the data stored about them, fix it if it is wrong, and have it deleted if they want.

The advance of the “internet of things” means that everyday objects are being computerised and are capable of collecting and transmitting data about us and how we use them. A robotic vacuum cleaner can, for instance, record the dimensions of your home. Smart lighting can take note of when you are home. Your car knows exactly where you have gone.

For this reason, Cooper says she will not have voice-activated assistants – such as Google’s Home, Amazon Echo’s Alexa or Facebook’s Portal – in her home. “It has crossed over the creepy line,” she says.

“All that data can be used in machine learning. They know what time you are in the house, what room you are in, how many people are in the conversation, keywords.”

Your data can be compromised

Speculation that Alexa is spying on us by storing our private conversations has been dismissed by fact-checking website Politifact, although researchers have found the device can be hacked.

The devices are “always-on” to listen for an activating keyword, but the ambient noise is recorded one second at a time, with each second dumped and replaced until it hears a keyword like “Alexa”.

However, direct commands to those two assistants are recorded and stored on company servers. That data, which can be reviewed and deleted by users, is used to a different extent by the manufacturers.

Google uses the data to build out your profile, which helps advertisers target you. Amazon keeps the data to itself but may use that to sell you products and services through its own businesses. For instance, the company has been granted a patent to recommend cough sweets and soup to those who cough or sniff while speaking to their Echo.

In discussions about rising concerns about the use and misuse of our data, Cooper says she is frustrated by those who tell her that “privacy is dead” or “the horse has bolted”. She says it is not too late to regain control of our data.

“It is hard to fix, it is complex, it is a u-turn in some areas, but that doesn’t mean that you don’t do it.”

It was not that long ago that publicly disagreeing with your employer’s business strategy or staging a protest without the protection of a union, would have been a sackable offence.

But not today – if you are among the business “elite”.

Last year, 4,000 Google employees signed a letter of protest about an artificial intelligence project with the Department of Defense. Google agreed not to renew the contract. No-one was fired.

Also at Google, employees won concessions after 20,000 of them walked out protesting the company’s handling of sexual harassment cases. Everyone kept their jobs.

Consulting firms Deloitte and McKinsey & Company and Microsoft have come under pressure from employees to end their work with the US Department of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), because of concerns about the separation of children from their illegal immigrant parents.

Amazon workers demanded the company stop selling its Rekognition facial recognition software to law enforcement.

Examples like these show that collective action at work can still take place, despite the decline of unionism, if the employees are considered valuable enough and the employer cares about its social standing.

The power shift

Charles Wookey, CEO of not-for-profit organisation A Blueprint for Better Business says workers in these kinds of protests have “significant agency”.

“Coders and other technology specialists can demand high pay and have some power, as they hold skills in which the demand far outstrips the supply,” he told CEO Magazine.

Individual protesters and whistle-blowers, however, do not enjoy the same freedom to protest. Without a mass of colleagues behind them, they can face legal sanction or be fired for violating the company’s code of conduct – as was Google engineer James Damore when he wrote a memo criticising the company’s affirmative action policies in 2017.

Head of Society and Innovation at the World Economic Forum, Nicholas Davis, says technology has enabled employees to organise via message boards and email.

“These factors have empowered employee activism, organisation and, indeed, massive walkouts –not just around tech, by the way, but around gender and about rights and values in other areas,” he said at a forum for The Ethics Alliance in March.

Change coming from within

Davis, a former lawyer from Sydney, now based in Geneva, says even companies with stellar reputations in human rights, such as Salesforce, can face protests from within – in this case, also due to its work with ICE.

“There were protesters at [Salesforce annual conference] Dreamforce saying: ‘Guys, you’re providing your technology to customs and border control to separate kids from their parents?,” he said.

Staff engagement and transparency

Salesforce responded by creating Silicon Valley’s first-ever Office of Ethical and Humane Use of Technology as a vehicle to engage employees and stakeholders.

“I think the most important thing is to treat it as an opportunity for employee engagement,” says Davis, adding that listening to employee concerns is a large part of dealing with these clashes.

“Ninety per cent of the problem was not [what they were doing] so much as the lack of response to employee concerns,” he says. Employers should talk about why the company is doing the work in question and respond promptly.

“After 72 hours, people think you are not taking this seriously and they say ‘I can get another job, you know’, start tweeting, contact someone in the ABC, the story is out and then suddenly there is a different crisis conversation.”

Davis says it is difficult to have a conversation about corporate social activism in Australia, where business leaders say they are getting resistance from shareholders.

“There’s a lot more space to talk about, debate, and being politically engaged as a management and leadership team on these issues. And there is a wider variety of ability to invest and partner on these topics than I perceive in Australia,” says Davis, who is also an adjunct professor with Swinburne University’s Institute for Social Innovation.

“It’s not an issue of courage. I think it’s an issue with openness and demand and shifting culture in those markets. This is a hard conversation to have in Australia. It seems more structurally difficult,” he says.

“From where I stand, Australia has far greater fractures in terms of the distance between the public, private and civil society sectors than any other country I work in regularly. The levels of distrust here in this country are far higher than average globally, which makes for huge challenges if we are to have productive conversations across sectors.”

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 14 FEB 2019

James Baldwin was one of the great American writers of the twentieth century.

His elegant, articulate and keenly perceptive work bore witness to the hostile, day-to-day realities in which African Americans lived, and the psychological implications of racism for society as a whole.

His fifth novel, If Beale Street Could Talk, is no exception. Forty-four years after it was published, Moonlight director Barry Jenkins has adapted it for the screen.

A different type of love story

A hypnotic, visually sumptuous and intimate love story, Beale Street has little of the structure of a traditional romance. The film begins, for instance, with the generic arc of courtship already complete. We first see the two young protagonists – Tish Rivers and her boyfriend Alfonzo ‘Fonny’ Hunt – walking slowly together in a park, their affections clear and perfectly mirrored. Growing up as childhood friends in the Bronx, there was never a time they did not love each other.

The story instead bears testimony to the resilience of love, and the strength it endows those who have faith in it. Here, we witness its many forms arrayed against a vast, malicious and coldly impersonal system which is rigged to destroy black lives and fracture the most precious of bonds.

Barely a minute into screen time, the plot throws Fonny (Stephan James) behind a glass wall. He’s in jail after being accused of rape. To his accuser and certainly the police, his innocence is irrelevant. As a black man, his identity in the white cultural imagination is as a violent savage – he was always-already condemned, regardless of his actions. It is through this transparent barrier that Tish (KiKi Layne) tells him that she is carrying his child.

When the past and present merge

Following this revelation, the story diverges in two interweaving streams of past and present. One, filled with hope and secret joys, sees the young couple come to understand each other as man and woman, while nursing dreams of a future together. In the second narrative, hope is not a simple impulse but an inviolable duty, as their baby swells in Tish’s womb, Fonny’s case stagnates and despair threatens. Each scene is freighted with the viewer’s knowledge that the lovers’ destiny is not their own.

Tish’s tale

This second narrative is also very much Tish’s story, and shifts its focus to a different kind of love. Beale Street is most affecting in its portrait of the Rivers family, who support Tish wholly and will do whatever they must to fight for her and the new life within her. Regina King won a Golden Globe for her portrayal of Tish’s mother Sharon, who embodies a fierce, calm and indominable maternal courage. Her father Joseph (played with a rich, growling warmth by Colman Domingo) and older sister Ernestine (Teyonah Parris) readily take on the role of advocate and defender.

Their unity has its foil in Fonny’s family, the Hunts, who refuse to partake in any struggle they did not ask for. Headed by a spiteful and Godfearing mother, who curses her unborn grandchild and rationalises prison as a place in which Fonny can find the Lord, theirs is a pride born of self-serving weakness. The Rivers’ contrasting pride is one born of unassailable dignity and a determination to act, in spite of the odds arrayed against them.

“What do you think is going to happen?” asks Mr Hunt when Joseph lays out a plan for them to steal from their workplaces to help their children.

“What we make happen.”

“Easy to say,” Hunt protests.

“Not if you mean it,” Joseph levelly responds.

Emotional explotation

Through these characters, Beale Street puts forward the case for love as the single most steadfast bastion against the dehumanising machine of systemic oppression. Those characters without this vital force are vulnerable to emotional exploitation – betraying family and friends to protect themselves. Hunt’s mother sacrifices her son rather than align herself with his fate.

Fonny’s old friend Daniel also deserts him when his words could have saved him, his integrity broken by the terror of returning to a prison that broke him. And Fonny’s accuser is so traumatised, she is locked in a prison of her own pain, insensible and insensitive the suffering of others.

None of these individuals are free. Living in a constant wash of fear without refuge or reprieve has deprived them of their integrity, transforming them into actively complicit agents in the perpetuation of a racist structure. This, Baldwin’s story reveals, is perhaps the most wretched and insidiously effective mechanism of tyranny.

Racial tensions

Daniel is sure that white man is the devil. But Beale Street itself doesn’t espouse this view. At crucial junctures, white allies take risks to intercede against social, economic, police and court racial injustice. A Jewish real estate agent grants the lovers a path to an affordable home. An old storekeeper stands up to a reptilian policeman. And Fonny’s lawyer is a ‘white boy just out of college’.

At two hours, the film is languid and poetic, with gorgeous cinematography by James Laxton. The deliberate slow pacing and the use of frequent close-ups demands of the viewer they recognise the central (and very beautiful) characters as subjects. In a culture which frequently effaces black bodies, fetishises them, or arbitrarily fashions them into villains, these images are quietly radical. The film plays out between the steady gaze of the two lovers, and plays within the gaze of an audience that can’t look away.

Quietly significant too, is the film’s inclusion of moments which are superfluous to the plot, but vital to the immersive legacy of Beale Street. One, impossible to forget: Tish’s parents swaying before a jazz record in the family loungeroom, holding each other close, smiling in the new knowledge of themselves as grandparents to be.

Final thoughts

Opening in Australia on Valentine’s Day, Jenkins’ film is a tender dream of two lovers trapped in a too-real nightmare. It is not difficult to remember that this nightmare still torments the freedoms of racial minorities in America, ‘the land of the free’, and other nations too – whether they characterise themselves as progressive democracies or not.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

8 questions with FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Constitution is incomplete. So let’s finish the job

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Absolutism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Karen Wyld 24 JAN 2019

Like clockwork, every January Australians question when is, or even if there is, an appropriate time to celebrate the nationhood of Australia.

Each year, a growing number of Australians acknowledge that the 26thof January is not an appropriate date for an inclusive celebration.

There are no sound reasons why the date shouldn’t be changed but there are plenty of reasons why the nation needs to change.

I’ve written about that date before, its origins and forgotten stories and recent almost-comical attempts to protect a public holiday. I choose not to repeat myself, because the date will change.

For many, the jingoism behind Australia Day is representative of a settler colonialism state that should not be preserved. A nation that is not, and has never been fair, free or young. So, I choose to put my energy into changing the nation. And I am not alone.

People are catching up and contributing their voices to the call to change the nation, but this is not a new discussion. On 26 January 1938, on the 150thanniversary of the British invasion of this continent, a group of Aboriginal people in NSW wrote a letter of protest, calling it a Day of Mourning. They asked the government to consider what that day meant to them, the First Peoples, and called for equality and justice.

Since 1938, the 26thof January continues to be commemorated as a Day of Mourning. The date is also known as Survival Day or Invasion Day to many. Whatever people choose to call that day, it is not a date suitable for rejoicing.

It was inconsiderate to have changed the date in 1994 to the 26th January. And, now the insensitivity is well known, it’s selfish not to change the date again. The only reasons I can fathom for opposition to changing the date is white privilege, or perhaps even racism.

These antiquated worldviews of white superiority will continue to haunt Australia until a critical mass has self reflected on power and privilege and whiteness, and acknowledges past and present injustices. I believe we’re almost there – which explains the frantic push back.

A belief in white righteousness quietened the voices of reason and fairness when the first fleet landed on the shores of this continent. And it enabled colonisers and settlers to participate in and/or witness without objection decades of massacres, land and resource theft, rape, cultural genocide and other acts of violence towards First Peoples.

The voice of whiteness is also found in present arguments, like when the violence of settlement is justified by what the British introduced. It is white superiority to insist science, language, religion, law and social structures of an invading force are benevolent gifts.

First Peoples already had functioning, sophisticated social structures, law, spiritual beliefs, science and technology. Combining eons of their own advances in science with long standing trade relations with Muslim neighbours, First Peoples were already on an enviable trajectory.

Tales of white benevolence, whether real or imagined, will not obliterate stories of what was stolen or lost. Social structures implanted by the new arrivals were not beneficial for First Peoples, who were barred from economic participation and denied genuine access to education, health and justice until approximately the 1970s.

Due to systemic racism, power and privilege, and social determinants, these introduced systems of justice, education and health still have entrenched access and equity barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Changing the nation involves settler colonialists being more aware of the history of invasion and brutal settlement, as well as the continuing impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It involves an active commitment to reform, which includes paying the rent.

The frontier wars did not result in victory for settler colonialists, because the fight is not over. The sovereignty of approximately 600 distinctly different cultural/language groups was never ceded. Despite generations of violence and interference from settler colonialists, First Peoples have not been defeated.

“You came here only recently, and you took our land away from us by force. You have almost exterminated our people, but there are enough of us remaining to expose the humbug of your claim, as white Australians, to be a civilised, progressive, kindly and humane nation.”

‘Aborigines Claim Citizen Rights!: A Statement of the Case for the Aborigines Progressive Associations’, The Publicist, 1938, p.3

Having lived on this continent for close to 80,000 years and surviving the violence of colonisation and ongoing injustices of non-Indigenous settlement, the voices of First Peoples cannot be dismissed. The fight for rights is not over.

The date will change. And, although it will take longer, the nation will change. There are enough still standing to lead this change – so all Australians can finally access the freedoms, equality and justice that Australia so proudly espouses.

Karen Wyld is an author, living by the coast in South Australia

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Is it time to curb immigration in Australia?

Is it time to curb immigration in Australia?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 24 JAN 2019

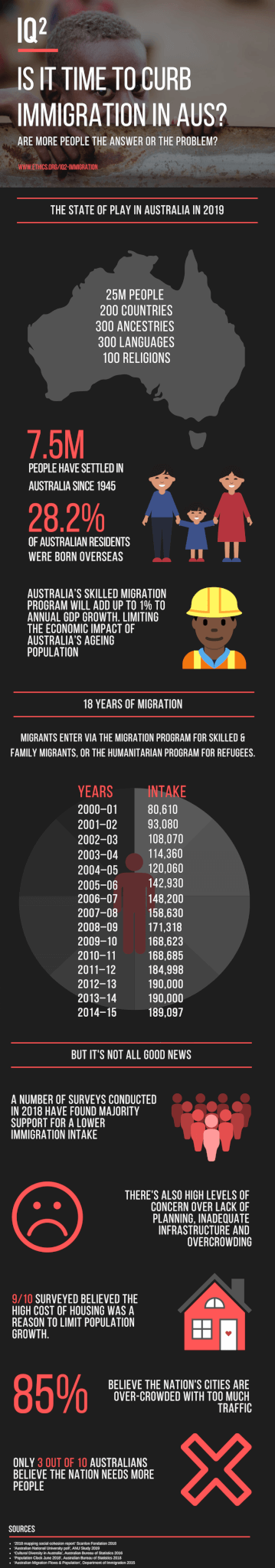

To curb or not to curb immigration? It’s one of the more polarising questions Australia grapples with amid anxieties over a growing population and its impact on the infrastructure of cities.

Over the past decade, Australia’s population has grown by 2.5 million people. Just last year, it increased by almost 400,000, and the majority – about 61 percent net growth – were immigrants.

Different studies reveal vastly different attitudes.

While Australians have become progressively more concerned about a growing population, they still see the benefits of immigration, according to two different surveys.

Times are changing

In a new survey recently conducted by the Australian National University, only 30 percent of Australians – compared to 45 percent in 2010 – are in favour of population growth.

The 15 percent drop over the past decade is credited to concerns about congested and overcrowded cities, and an expensive and out-of-reach housing market.

Nearly 90 percent believed population growth should be parked because of the high price of housing, and 85 percent believed cities were far too congested and overcrowded. Pressure on the natural environment was also a concern.

But a Scanlon Foundation survey has revealed that despite alarm over population growth, the majority of Australians still appreciate the benefits of immigration.

In support of immigration

In the Mapping Social Cohesion survey from 2018, 80 percent believed “immigrants are generally good for Australia’s economy”.

Similarly, 82 percent of Australians saw immigration as beneficial to “bringing new ideas and cultures”.

The Centre for Independent Studies’ own polling has shown Australians who responded supported curbing immigration, at least until “key infrastructure has caught up”.

In polling by the Lowy Institute last year, 54 percent of respondents had anti-immigration sentiments. The result reflected a 14 percent rise compared to the previous year.

Respondents believed the “total number of migrants coming to Australia each year” was too high, and there were concerns over how immigration could be affecting Australia’s national identity.

While 54 percent believed “Australia’s openness to people from all over the world is essential to who we are as a nation”, trailing behind at 41 percent, Australians said “if [the nation is] too open to people from all over the world, we risk losing our identity as a nation”.

Next steps?

The question that remains is what will Australia do about it?

The Coalition government under Scott Morrison recently proposed to cap immigration to 190,000 immigrants per year. Whether such a proposition is the right course of action, and will placate anxieties over population growth, remains to be seen.

Join us

We’ll be debating IQ2: Immigration on March 26th at Sydney Town Hall, for the full line-up and ticket info click here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Gordon Young 17 JAN 2019

Few topics bridge the ever widening divide between both sides of politics quite like the need to manage population growth.

Whether it’s immigration or environmental sustainability, fiscal responsibility or social justice. That the global population breached 7.5 billion in 2017 has everyone concerned.

We are at the point where the sheer volume of people will start to put every system we rely on under very serious stress.

This is the key idea motivating the centrist political party Sustainable Australia. Led by William Bourke and joined by Dick Smith, the party advocates for a non-discriminatory annual immigration cap at 70,000 persons, down from the current figure of around 200,000 – aimed at a “better, not bigger” Australia.

Join the first IQ2 debate for 2019, “Curb Immigration”. Sydney Town Hall, 26 March. Tickets here.

While the party has been accused of xenophobic bigotry for this stance, their policy makes clear they are not concerned about an immigrant’s religion, culture, or race. Their concern is exclusively for the stress greater numbers of migrants will place on Australia’s infrastructure and environment.

It is a compelling argument. After all, what is the point of the state if not to protect the interests of its citizens?

A Looming Problem

We should be concerned with the needs and interests of our international neighbours, but such concerns must surely be strictly secondary to our own. When our nearest neighbour has approximately ten times our population, squeezed into a landmass twenty five per cent Australia’s size, and ranks 113 places behind us in the Human Development Index, one can be forgiven for believing that limited immigration is critical for ongoing Australian quality of life.

This stance is further bolstered by the highly isolated, and therefore vulnerable nature of Australia’s ecosystem. Australia has the fourth highest level of animal species extinction in the world, with 106 listed as Critically Endangered and significantly more as Endangered or Under Threat.

Much of this is due to habitat loss from human encroachment as suburbs and agricultural lands expand for our increasing needs. The introduction of foreign flora and fauna can be absolutely devastating to these species, greatly facilitated by increased movement between neighbour nations (hence the virtually unparalleled ferocity of our quarantine standards).

While the nation may be a considerable exporter of foodstuffs, many argue Australia is already well over its carrying capacity. Any additional production will be degrading the land and our ability to continue growing food into the future.

The combination of ecological threats and socio-economic pressure makes the argument for limiting immigration to sustainable numbers a powerful one.

But it is absolutely doomed to failure.

Fortress Australia

If the objective of limiting immigration to Australia is both to protect our environment and maintain high quality of life, “Fortress Australia” will fail on both fronts. Why?

Because it does nothing to address the fundamental problem at hand. Unsustainable population growth in a world of limited resources.

Immigration controls may indeed protect both the Australian quality of life and its environment for a time, but without effective strategic intervention, the population burden in neighbouring countries will only continue to grow.

As conditions worsen and resources dwindle, exacerbated by the impacts of anthropogenic climate change, citizens of those overpopulated nations will seek an alternative. What could be more appealing than the enormous, low-density nation with incredibly high quality of life, right next door to them?

If a mere 10 percent of Indonesians (the vast majority of which live on the coast and are exceptionally vulnerable to climate change impacts) decided to attempt the crossing to Australia, we would be confronted by a flotilla equivalent to our entire national population.

The Dilemma

At this point we have one of two choices: suffer through the impact of over a decade’s worth of immigration in one go or commit military action against twenty-five million human beings. Such a choice is a Utilitarian nightmare, an impossible choice between terrible options, with the best possible result still involving massive and sustained suffering for all involved. While ethics can provide us with the tools to make such apocalyptic decisions, the best response by far is to prevent such choices from emerging at all.

Population growth is a real and tangible threat to the quality of life for all human beings on the planet, and like all great strategic threats, can only be solved by proactively engaging in its entirety – not just its symptoms.

Significant progress has been made thus far through programs that promote contraception and female reproductive rights. There is a strong correlation between nations with lower income inequality and population growth, indicating that economic equity can also contribute towards the stabilisation of population growth. This is illustrated by the decreasing fertility rates in most developed nations like Australia, the UK and particularly Japan.

Cause and Effect

The addressing of aggravating factors such as climate change – a problem overwhelmingly caused by developed nations such as Australia, both historically and currently through our export of brown coal– and continued good-faith collaboration with these developing nations to establish renewable energy production, will greatly assist to prevent a crisis occurring.

When concepts such as immigration limitations seek to protect our nation by addressing the symptoms, we are better served by asking how the problem can be solved from its root.

Gordon Young is an ethicist, principal of Ethilogical Consulting and lecturer in professional ethics at RMIT University’s School of Design.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Gordon Young

Gordon Young is a lecturer on professional ethics at RMIT University and principal at Ethilogical Consulting.

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Oliver Jacques 15 JAN 2019

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Australia’s two biggest states are moving in opposite directions when it comes to adoption. While New South Wales is accused of tearing families apart, is Victoria right to deny children a voice?

A new stolen generation is coming to you soon.

Or so you would think if you read the reaction to recent NSW reforms aimed at making adoption easier.

NSW Parliament has passed new laws placing a two year time limit on a child staying in foster care. After this time, the state can pursue adoption if a child can’t safely return home, even if birth parents don’t agree.

Critical articles across media raised the spectre of another stolen generation.

An open letter signed by 60 community groups said the NSW Government was “on a dangerous path to ruining lives and tearing families apart”. Indigenous writer Nayuka Gorrie tweeted, “Adoption without parental consent is kidnapping”.

But should a parent really have the right to block the adoption of the child they neglected?

Laws prohibit journalists from identifying people involved in child protection cases so media coverage rarely includes the views of children, even after they turn 18. The laws exist to protect vulnerable minors, but such voices could add some balance to the debate and explain why NSW is ahead in putting children first.

Foster care crisis

Out-of-home care adoption – where legal parenting rights are transferred from birth parents to foster parents – is extremely rare in Australia. Last year, there were 147 children foster care adoptions. That’s a tiny fraction of the 47,000 Australian children living in out-of-home care.

Previously, kids could be placed in state care simply because they were born to a single mother or an Aboriginal woman.

These days, child protection workers only remove children if their lives are in danger due to repeated abuse or neglect.

While foster care is supposed to be a temporary arrangement, children on average spend 12 years in care, often bouncing from one temporary home to another.

It’s no surprise more than a third of foster children end up homeless soon after leaving care.

Permanent care instead of adoption

While NSW is trying to make adoption easier, Victoria is not. None of the more than 10,000 children in Victorian state care were adopted last year.

Victorian children who can’t return home are placed in ‘permanent care’, where they remain a ward of the state but are housed by the same foster carers until age 18.

Paul McDonald, CEO of Anglicare Victoria, describes permanent care as a “win-win-win” for children, birth parents and foster carers. He argues it provides stability for children without changing their legal status “so dramatically”.

Ignoring children’s voices

Former AFL player Brad Murphy, who grew up in Victorian permanent care, begs to differ. “From a child’s perspective, you don’t always feel secure in permanent care,” he said. “I longed for adoption. I wanted to belong to my foster parents, I wanted the same surname.”

Victoria didn’t allow him to be adopted by his loving foster carers because his birth father wouldn’t provide consent.

Murphy believes the Victoria Government should give children a say. “When I was 3 years old, I was calling my foster carer ‘Mum’, as I do now at age 33. I always knew what I wanted”.

The other problem with denying children an adoption choice is they continue to belong to the state. “Government were making all the decisions in my life. And like everything with government, it’s never done quickly,” Murphy said.

He often missed out on school camps and excursions because bureaucrats didn’t sign off permission.

Brad was placed in foster care at 16 months of age. Soon after, his mother ‘did a runner’ to Western Australia. His father was in jail for most of his childhood.

“I was never going back to my birth parents. If birth parents don’t make any effort to change their ways, why should the child suffer any longer?”

Case for reform

There are other parents, though, who want to change their ways but support is scarce. Housing, counselling and rehab facilities across Australia are lacking for low income families.

Some argue we should devote more resources toward keeping vulnerable families together, rather than promoting adoption reform.

There is no reason why we can’t do both. Help families where change is possible, but give children a choice when it’s not.

Though separating children from birth parents can prove traumatic, so is constant abuse. Some kids are terrified of their parents and want stability and the feeling of belonging with their new family.

In NSW, caseworkers must ask children what they want, if they’re old enough to understand. Prospective adoptive parents must educate kids about their history and culture. Birth parents can remain connected to children when it’s safe and in the child’s interests.

Overseas studies show adopted children have better life outcomes than those who remain in long term foster care.

Adoption won’t work for everyone, but it could benefit many kids.

Those criticising NSW reforms should also ask the Victorian government why it continues to deny children the basic human right to be heard.

Are you facing an ethical dilemma? We can help make things easier. Our Ethi-call service is a free national helpline available to everyone. Operating for over 25 years, and delivered by highly trained counsellors, Ethi-call is the only service of its kind in the world. Book your appointment here.

Oliver Jacques is a freelance journalist and writer.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Kate Manne

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Exercising your moral muscle

BY Oliver Jacques

Oliver Jacques is a freelance writer and tutor based in Griffith, NSW. His writing has appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald, The Guardian, ABC, SBS, Daily Telegraph, Herald Sun, Eureaka Street and The Shovel. He has a Masters Degree in Public Policy at ANU; a graduate certificate in journalism at UTS; and has completed courses in copywriting and search engine optimisation at the Australian Writers Centre.

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY Aisyah Shah Idil ethics 30 NOV 2018

It’s been called dangerous, unethical and a game of human Russian roulette.

International outrage greeted Chinese scientist He Jiankui’s announcement of the birth of twin girls whose DNA he claims to have altered using the gene editing technique CRISPR. He says the edit will protect the twins, named Lulu and Nana, from HIV for life.

“I understand my work will be controversial”, Jiankui said in a video he posted online.

“But I believe families need this technology and I’m ready to take the criticism for them.”

The Center for Genetics and Society has called this “a grave abuse of human rights”, China’s Vice Minister of Science and Technology has issued an investigation into Jiankui’s claims, while a UNESCO panel of scientists, philosophers, lawyers and government ministers have called for a temporary ban on genetic editing of the human genome.

Condemnation of his actions have only swelled after Jiankui said he is “proud” of his achievement and that “another potential pregnancy” of a gene edited embryo is in its early stages.

While not completely verified, the news has been a cold shock to the fields of science and medical ethics internationally.

“People have naive ideas as to the line between science and application”, said Professor Rob Sparrow from the Department of Philosophy at Monash University. “If you believe research and technology can be separated then it’s easy to say, let the scientist research it. But I think both those claims are wrong. The scientific research is the application here.”

The fact that we can do something does not mean we should. Read Matt Beard and Simon Longstaff’s guide to ethical tech, Ethical By Design: Principles of Good Technology here.

The ethical approval process of Jiankui’s work is unusual or at least unclear, with reports he received a green light after the procedure. Even so, Sparrow rejects the idea that countries with stricter ethical oversight have some responsibility to relax their regulations in order to stop controversial research going rogue.

“Spousal homicide is bound to happen. That doesn’t mean we don’t make it legal or regulate it. Nowadays people struggle to believe that anything is inherently wrong.

“Our moral framework has been reduced to considerations of risks and benefits. The idea that things might be inherently wrong is prior to the risk/benefit conversation.”

But Jiankui has said, “If we can help this family protect their children, it’s inhumane for us not to”.

Professor Leslie Cannold, ethicist, writer and medical board director, agrees – to a point.

“The aim of this technology has always been to assist parents who wish to avoid the passing on of a heritable disease or condition.

“However, we need to ensure that this can be done effectively, offered to everyone equally without regard to social status or financial ability to pay, and that it will not have unintended side effects. To ensure the latter we need to proceed slowly, carefully and with strong measurements and controls.

“We need to act as ‘team human’ because the changes that will be made will be heritable and thereby impact on the entire human race.”

If Jiankui’s claims are true, the edited genes of the twin girls will pass to any children they have in the future.

“No one knows what the long term impacts on these children will be”, said Sparrow.

“This is radically experimental. [But] I do think it’s striking how for many years people drew a bright line at germline gene editing but they drew this line when gene editing wasn’t really possible. Now it’s possible and it’s very clear that line is being blurred.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

We are the Voice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Big thinker

Science + Technology