Is it ethical to splash lots of cash on gifts?

Is it ethical to splash lots of cash on gifts?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 10 DEC 2018

Whether you’re a tearer, a folder, a scruncher, or a chucker, there’s nothing like opening a wrapped gift that’s especially suited to you.

Amid the hugs and backslaps it’s hard to say who it’s more satisfying for – the giver or the receiver.

But when little Millie gets the new PlayStation while Amir’s staring at his plastic water gun, the thin film of politeness peels away. We don’t just wonder why we have the gifts we do. We wonder how much they cost.

This holiday season, we’re exploring the ethical dimensions of splurging on gifts. Are there unspoken rules for those with deeper pockets? Is it killing the spirit of generosity to peer at the price tag? Or is keeping mum about money letting us pretend we don’t owe things to each other all the time?

Christmas conundrums? Book a free appointment with Ethi-call. A non-partisan, highly trained professional will help you navigate any ethical minefields this holiday season.

There are so many different kinds of purposes tied to gift giving on Christmas, or any large celebration. We like to think of these sorts of gifts as intrinsically good, making them different from bribes given for personal gain.

For some, gifts are an informal way to foster love and support in mutual relationships. They encourage closeness and dependencies between social circles to reveal links our individualism tends to hide.

They’re known to shape our moral character and encourage selfless generosity, even to remove feelings of emotional debt that have accumulated throughout the year. Though we speak of gifts as just ways to “show love and appreciation”, our reasons are often more layered than that.

This doesn’t have to be self-indulgent navel-gazing. Examining the purpose of a gift matters because it encourages us to consider if that special, one-of-a-kind purchase is the only way to fulfil it. What duties or consequences should you consider before making that jump?

The duties of gifting

If you are feeling the end of year pinch, you have a duty to yourself to make sure the gift giving season doesn’t put you into financial strife. But if that conflicts with the duty to be fair to your friends and family, ask yourself what matters more. After all, gifts are often an exchange, and appreciating someone’s thoughtfulness can come with offering a similarly tasteful gift of your own.

If the gift is for a friend or peer, we might worry about setting an expectation or precedent we can’t fulfil. If it’s for someone who would struggle to fork out a similar amount of money for a gift, would this leave them feeling uncomfortably tied to you? And if you want to spread the holiday cheer, this leaves your pool of lucky recipients fairly limited.

Nor can the growing consciousness around our impact on the environment be ignored. Are these gifts worth the cost to landfills, unethical supply chains, and our collective duty to preserve the health of the land we live on?

But let’s not dwell on the negative. There are heaps of positive consequences too. Don’t forget the good that comes from making the people around you feel extra special and appreciated. If you struggle with miserliness, or excessive penny pinching, this could be a win-win way to encourage generosity in you, and make someone else very happy. It’s always worth thinking of how your actions reflect your character.

When all is said and done, the holidays are a time to rest. The softening pleasures of food, drink, company and play don’t have to get in the way of a well examined life. In fact, slowing down our frenetic, demanding lives to allow time to recuperate may be just what we need most: the modest admission that we cannot do everything perfectly. Good enough is good enough.

That’s the spirit!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 7 DEC 2018

Before there were candles and doughnuts, there was a Greek king and some very pissed off Jews.

Right now, Jews all around the world are observing Hanukkah. It began on the 2nd of December and will last until the 10th.

Even though it’s nicknamed “The Festival of Lights” for its distinctive candles, Hanukkah is also a nod to military rebellion. Here’s how the story goes.

It’s the second century BCE. The Greek Selucid Empire is in power and Antiochus, the king, wants the Jewish community to finally abandon their traditions and fully embrace wider Greek culture.

Some Jews had already assimilated. But for Antiochus to have total control over the empire, the pocket of devout ones need to as well. Since they’re not giving up without a fight, he decides imperial force is necessary.

Antiochus vandalises their most sacred temple and bans Jews from praying or performing ritual sacrifice there. An altar to Zeus is propped up, pigs are sacrificed on it, Sabbath is forbidden and circumcision is banned. Dissenters are killed. Judaism is outlawed by the state.

Predictably, there is large scale revolt. The Maccabees, a Jewish warrior family, violently seize the temple back. Once they and their allies purify it to their standards and replace the pagan icons with their own, they finally light the menorah, the sacred lampstand in the temple.

There’s only just enough oil to light the candles for one day. But according to legend, these candles miraculously stayed lit for eight entire days, marking them as a victorious time of “joy and honour”.

This is why on Hanukkah, Jews traditionally eat festive foods fried in oil and light their own lamps. Each day, they eat potato fritters called latkes and jelly doughnuts called soufjanyiot, sing special songs, play dreidel games and recite prayers. People give presents and money, and kids get chocolate coins. It’s an eight-day feast of leisure.

But it wasn’t always like that. Some rabbis have understandably been uncomfortable with Hanukkah’s military undertones. Others have pointed out that celebrating the conflict between Jewish secularism and fundamentalism is a little odd.

But with the advent of Zionism and the state of Israel, Hanukkah has taken on new life. From a minor holiday that emphasised the miracle of the oil, Hanukkah today is seen as a symbol of resistance against injustice and oppression.

It’s now been nearly eight decades since the Holocaust. There is a menorah in Midtown Manhattan dedicated to the victims of the Pittsburgh synagogue mass shooting. There is another in front of Brandenburg Gate where the Nazi flags once hung.

Amid rising concern over anti-Semitism, illiberalism in Israel, and contradictions of ‘Jewish Christmas’, maybe it’s the historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah that is the most Jewish thing of all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Ethics Explainer: Hope

We hope for fine weather on weekends and the best for our buddies – an obvious statement that hardly screams ethics.

But within our everyday desires for good things, lies a duty to each other and ourselves to only act on reasonably held hopes.

The ethics of hope

One of Immanuel Kant’s simple but resonant maxims is ‘ought implies can’. In other words, if you believe someone has an ethical responsibility to do something, it must be possible. No person is under any obligation to do what is impossible. You might call me a bad person for failing to fly through the sky and save someone falling from a great height. But your condemnation will be rejected as ill-founded for the simple reason only fictional characters can perform that feat.

Many other things – including extremely difficult things – are reasonably expected of others. A person might promise to climb Mount Everest (or at least make a serious attempt) prior to their 50thbirthday. This might present the greatest challenge imaginable. Yet we know scaling the heights of Everest is possible. As such, the person who made this promise is bound to honour their commitment.

Of course, at the time of making such a promise, no person can know with absolute certainty they will be able to meet the obligation they have taken on. There are just too many variables outside of their control that can frustrate their best laid plans. Weather conditions might lead to the closure of the mountain. The need to provide personal care to a loved one could extend well beyond any anticipated period. Given this, our ethical commitments are almost always tinged with a measure of hope.

What is hope?

Hope is an expectation that some desirable circumstance will arise. Hope sometimes blends into something closer to ‘faith’ – where belief about a state of affairs cannot be proven. However, for most people, most of the time, ‘hope’ is a reasonable expectation.

For example, if a person makes commitments that critically depend on other people keeping their promises, that person cannot know for certain they can honour their word. Yet, if these people are known and trusted, perhaps based on past experience, then a hopeful dependence on their performance would be reasonable.

The same can be said of other commitments, such as promising to meet for a picnic on a particular day. You might make the plan in the hopeful expectation of fine weather and do so with good grounds based on a checked forecast predicting clear skies.

There are two things to be noted here. First, some aspects of hope depend (for their reasonableness) on the ethical commitments of other people (for example, to keep promises). It follows there will often be a reciprocal ethical aspect to the practice of ‘reasonable’ hoping.

Second, it’s not enough to be naively hopeful. Instead, one needs to take reasonable efforts to ensure there is some basis for relying on a hoped-for circumstance. This is especially so if the hoped-for circumstance is of critical importance to matters of grave ethical significance – such as making a promise to someone.

Given this, there may be good grounds to calibrate commitments in line with the degree to which you might reasonably hope for a particular circumstance to prevail. For example, rather than making an open commitment to meet for a particular picnic on a particular day it might be better to qualify the point by saying, “I promise to meet you if the weather is fine”.

‘It’s not enough to be naively hopeful.’

We often see the absence of this kind of forethought when it comes to the promises made by politicians during elections. They will make promises – probably based on hopeful projections about the future – only to find themselves accused of lying or having acted in bad faith when the promise is not honoured.

It’s insufficient for the politician to say they merely ‘hoped’ to be able to keep their word and that they now find their situation to be unexpectedly different. It would have been far better and far more responsible to qualify the promise in line with what might explicitly and reasonably be hoped for.

Two final comments. First, it should be understood a person often has some control over whether or not their hopes can be realised. As such, each person is responsible for those of their actions that impinge on the way they meet their obligations – we are not simply ‘bystanders’ who can idly hope for certain outcomes without lifting a finger to make them manifest.

Second, given our inability to know what the future holds, hope always plays a role in the process of making ethical commitments. The key thing is to be reasonable in what we hope for and to calibrate our commitments accordingly.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 4 DEC 2018

Turning a perceived disability into a new way of solving problems, Temple Grandin (1947—present) has revolutionised the meat-processing industry and changed the way the world views autism.

Temple Grandin is an autism advocate and animal scientist who works to improve animal treatment in the livestock industry. Grandin has also changed public perceptions of autism, helping educators to maximise the strengths of those with autism, rather than focusing only on deficiencies.

An animal lover and meat eater, Grandin has used her autistic trait of “thinking in pictures” to design livestock facilities and educate meat produces on how to minimise animal suffering. As a result, she says there’s been ‘light years of improvement’ in an industry where half of all cattle in the United States are handled in facilities she designed.

This isn’t enough for some animal rights activists though, who accuse her of trying to soften the image of a ‘violent’ sector.

Thinking like a cow

Temple Grandin did not talk until she was three and a half years old. She struggled to communicate throughout her childhood, and other students bullied her at school.But there was one high school teacher, Mr Carlock, who saw something special in her. He mentored the troubled girl and encouraged her to study science.

Shocked by the cruelty she saw in abattoirs, Grandin combined her love for science and animals by fixating on designs to improve animal welfare in these facilities. Grandin knew she learned better by visualising, rather than reading and hearing long strings of words. In this respect, her thinking pattern was similar to animals, who don’t ‘speak’ a language.

She observed cattle in slaughterhouses, seeing how they responded to fear, senses, smells and visual memories. When cows can see they’re about to be killed, they panic, fall and injure themselves. To combat this, Grandin invented the curved loading chutes, which block their vision of what’s ahead, keeping them calm.

This not only improves animal welfare, it saves producers the cost of cattle death, injury and bruising – which also reduces the quality of meat. Grandin has spent her career designing livestock facilities to improve the way animals are treated.

In 1997, she worked with McDonalds after activists exposed animal torture on their production plants. She helped the fast food chain clean up cruel practices and restore its public image.

In 2010, Time Magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people in the world for her work in animal welfare.

We need autistic minds

Grandin has also changed public perceptions of autism, a condition relatively unknown when she grew up. She argues people on the autism spectrum – who tend to struggle with verbal communication but think in pictures – can provide more insight in certain fields than those who think in a more conventional mathematical way.

“Visual thinking is an asset for an equipment designer. I am able to ‘see’ how all parts of a project will fit together and see potential problems.”

Grandin encourages teachers to develop the strengths of autistic children, and has devised clever ways to combat perceived flaws.Like many on the spectrum, she is oversensitive to touch. “I always hated to be hugged”, she says.

So at age 18, she built a ‘squeeze machine’ – two hinged wooden boards lined with foam rubber, which allows users to control the amount and duration of pressure applied. Therapy programs across the United States continue to utilise squeeze machines, with research showing they help relieve stress in users.

Hero or villain?

While considered a hero in the autism community, Grandin’s work divides animal welfare activists. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), the world’s largest animal rights group, appreciate and publish her work. Others, like biologist Marc Bekoff, hold that no animal in captivity can enjoy a pleasant life. Bekoff would rather see Grandin encourage people not to consume factory farmed animals; to him, “‘slightly better’ isn’t good enough”.

“No animal who winds up in the factory farm production line has a good or even moderately good life.” – Marc Bekoff

Grandin’s retort is that without meat eaters, farm animals would have no life at all. She argues if animals are going to die anyway, it’s important to minimise their suffering.

Does this apply to humans too?

The New York Times once asked her if she’d consider helping to make capital punishment more humane. Her response was blunt.

“I have read things about the malfunctions of the electric chair… I know how to fix it, but I will not use my knowledge to have any involvement in that. I will not cross the species barrier to help kill people. Period.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does your body tell the truth? Apple Cider Vinegar and the warning cry of wellness

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

5 ethical life hacks

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Double-Effect Theory

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 23 NOV 2018

Technology needs to be designed to a set of basic ethical principles. Designers need to show how. Matt Beard, co-author of a new report from The Ethics Centre, demands more from the technology we use every day.

In The Amazing Spider-Man, a young Peter Parker is coming to grips with his newly-acquired powers. Spider-Man in nature but not in name, he suddenly finds himself with increased reflexes, strength and extremely sticky hands.

Unfortunately, the subway isn’t the controlled environment for Parker to awaken as a sudden superhuman. His hands stick to a woman’s shoulders and he’s unable to move them. His powers are doing exactly what they were designed to do, but with creepy, unsettling effects.

Spider-Man’s powers aren’t amazing yet; they’re poorly understood, disturbing and dangerous. As other commuters move to the woman’s defence, shoving Parker away from the woman, his sticky hands inadvertently rip the woman’s top clean off. Now his powers are invading people’s privacy.

A fully-fledged assault follows, but Parker’s Spider-Man reflexes kick in. He beats his assailants off, sending them careening into subway seats and knocking them unconscious, apologising the whole time.

Parker’s unintended creepiness, apologetic harmfulness and head-spinning bewilderment at his own power is a useful metaphor to think about another set of influential nerds: the technological geniuses building the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’.

Sudden power, the inability to exercise it responsibly, collateral damage and a need for restraint – it all sounds pretty familiar when we think about ‘killer robots’, mass data collection tools and genetic engineering.

This is troubling, because we need tech designers to, like Spider-Man, recognise (borrowing from Voltaire) that “with great power comes great responsibility”. And unfortunately, it’s going to take more than a comic book training sequence for us to figure this out.

For one thing, Peter Parker didn’t seek and profit from his powers before realising he needed to use them responsibly. For another, it’s going to take something more specific and meaningful than a general acceptance of responsibility for us to see the kind of ethical technology we desperately need.

Because many companies do accept responsibility, they recognise the power and influence they have.

Just look at Mark Zuckerberg’s testimony before the US Congress:

It’s not enough to connect people, we need to make sure those connections are positive. It’s not enough to just give people a voice, we need to make sure people aren’t using it to harm other people or spread misinformation. It’s not enough to give people control over their information, we need to make sure the developers they share it with protect their information too. Across the board, we have a responsibility to not just build tools, but to make sure those tools are used for good.

Compare that to an earlier internal memo – which was intended to be a provocation more than a manifesto – in which a Facebook executive is far more flippant about their responsibility.

We connect people. That can be good if they make it positive. Maybe someone finds love. Maybe it even saves the life of someone on the brink of suicide. So we connect more people. That can be bad if they make it negative. Maybe it costs a life by exposing someone to bullies. Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools. And still we connect people.

We can expect more from tech companies. But to do that, we need to understand exactly what technology is. This starts by deconstructing one of the most pervasive ideas going around called “technological instrumentalism”, the idea that tech is just a “value-neutral” tool.

Instrumentalists think there’s nothing inherently good or bad about tech because it’s about the people who use it. It’s the ‘guns don’t kill people, people kill people’ school of thought – but it’s starting to run out of steam.

What instrumentalists miss are the values, instructions and suggestions technologies offer to us. People kill people with guns, and when someone picks up a gun, they have the ability to engage with other people in a different way – as a shooter. A gun carries a set of ethical claims within it – claims like ‘it’s sometimes good to shoot people’. That may indeed be true, but that’s not the point – the point is, there are values and ethical beliefs built into technology. One major danger is that we’re often not aware of them.

Encouraging tech companies to be transparent about the values, ethical motivations, justifications and choices that have informed their design is critical to ensure design honestly describes what a product is doing.

Likewise, knowing who built the technology, who owns it and from what part of the world they come from helps us understand whether there might be political motivations, security risks or other challenges we need to be aware of.

Alongside this general need for transparency, we need to get more specific. We need to know how the technology is going to do what it says it’ll do and provide the evidence to back it up. In Ethical by Design, we argue that technology designers need to commit to a set of basic ethical principles – lines they will never cross – in their work.

For instance, technology should do more good than harm. This seems straightforward, but it only works if we know when a product is harming someone. This suggests tech companies should track and measure both the good and bad effects their technology has. You can’t know if you’re doing your job unless you’re measuring it.

Once we do that, we need to remember that we – as a society and as a species – remain in control of the way technology develops. We cultivate a false sense of powerlessness when we tell each other how the future will be, when artificial intelligence will surpass human intelligence and how long it will be until we’ve all lost our jobs.

Technology is something we design – we shape it as much as it shapes us. Forgetting that is the ultimate irresponsibility.

As the Canadian philosopher and futurist Marshal McLuhan wrote, “There is absolutely no inevitability, so long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Relativism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Elisabeth Shaw 23 NOV 2018

If the problem isn’t in your head or before your eyes, check your ethics.

Ethical decision making isn’t always easy. It can cause stress, anxiety and conflict. Elisabeth Shaw helps ease the tension.

We tend to see human suffering as having two separate branches: psychological and physical. Life events like loss, abuse, disasters or health issues blend the two together, but rarely do we consider including a third. Ethical.

Rita and her two sisters were grieving their mother’s death. Rita had been named as executor.

Over the last few months, Rita had been researching her family tree. She talked with her mother about her memories. Rita learned her mother had a boyfriend she left when she chose her father, and that she deeply regretted her decision.

In my experience as a team leader for Ethi-call, a helpline for people working through ethical conflicts and dilemmas, I commonly hear of peoples’ worry, anxiety and internal conflict about the decisions at hand. People who are anxious tend to ruminate, become preoccupied, sometimes withdraw from social supports and can have disrupted sleep. This can further compromise good decision making.

Research on emotions and ethical decision-making consistently notes the importance of fostering greater emotional capacity and skill. People who are stressed, tired or emotionally conflicted may find the requirement to make quick yet effective and sound decisions more challenging.

A couple of weeks before she died she confessed to Rita she had a son to that man. He had been offered for adoption – a decision that affected her whole life. Rita located the son through an online search.

But emotional maturity is a life-long project. When we are faced with an ethical decision, we have to act quickly and decisively. Sometimes the emotional capacity we need is not yet developed. What should we do?

We now understand unethical decision making tends to be more intuitive and automatic. By contrast, ethical decision making is rational, considered and deliberate. You may not be aware of the ethical dimension of your decision or that you’ve acted unethically – “it just seemed like the thing to do”.

She told her sisters, as Rita believed her mother would want her to find him and include him in the Will distribution. But her siblings were horrified at her proposal. “It’s him or us!” they said.

Stressed people often isolate themselves, making decisions based on anxiety, urgency and reactivity. Isolation is a major issue. Our desire to get rid of a burdensome problem can spur us to act quickly, without taking adequate time for reflection. We are also limited by our own imaginations and life experience.

Rita was torn in her loyalty to her mother, her commitment to family and her siblings. All options seemed flawed and her grief was compounding her distress.

Comparing notes with others can help us see more possibilities and calm ourselves enough to proceed effectively. At the same time, consulting too many people – or worse, the wrong people – can be equally distressing. Hearing conflicting, dogmatic opinions can be stressful as we worry about being judged negatively for declining to act on someone else’s advice.

What we’ve learned from our callers is that they want a pressure-free, neutral and objective space to explore their concerns. Without the bias of colleagues or close friends and the pressure of fast decision making, people can often find their own wisdom and create a reasonable and effective plan of action.

Ethi-call is one way to discover such a space, but it isn’t the only option. We can unlock our own ethical resources by reaching out to wise friends or mentors, allowing adequate time for reflection without being rushed or by challenging ourselves to think more creatively.

Rita thought she had to make a definite decision but she had more work to do before she could. Time was on her side – the probate process can be a long period and lots happened in her family in a short period.

Ethical issues are not always neatly resolved. They need to be deconstructed and disentangled, and achieving room to breathe and think is quite a lot in itself. Sorting out all the different influences, options and relationships takes time and careful thought. But taking care to find a framework to progress the decision, to come to a values driven plan and then live peacefully with one’s decision is work worth doing.

Was Rita leaping to conclusions about her mother’s wishes? Did her brother want to be part of the family at all? With time Rita was able to determine how she felt and how to act. What she ended up doing doesn’t matter. What matters is the way she reached her decision.

Are you currently dealing with an ethical dilemma? A conversation with an objective, independent person can really help. Book a free call with Ethi-call, our confidential ethics helpline.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The new normal: The ethical equivalence of cisgender and transgender identities

BY Elisabeth Shaw

Elisabeth Shaw is a clinical and counselling psychologist, CEO of Relationships Australia and Senior Consultant at The Ethics Centre.

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 NOV 2018

Being tied in a knot of lies, the danger of scepticism, micro-dosing LSD and dismantling bi-partisan politics were just some of the themes threaded throughout this year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas.

Thousands crossed the threshold into the Festival’s new home on Cockatoo Island. Two days, 31 sessions, and 45 speakers later, they left with a feast of ideas and new perspectives.

For the first time, the island’s unique location and new full-day festival pass meant that you could delve deeper into FODI than ever before.

Caliphate host Rukmini Callimachi shared aching stories of violence and honour in ISIS camps; conservative historian Niall Ferguson forced us all to rethink before we retweet; and pop-culture savant Chuck Klosterman had us empathising with the unlucky aliens who colonise us.

“Hard truths, fleshy realities, blunt edged disagreement and sharp new ideas – all mixed together with a throng of people in an iconic location that spoke alongside the artists and speakers. It was a brilliant amalgam, FODI at its best,” said Dr Simon Longstaff, co-founder, co-curator, and executive director of The Ethics Centre.

For the first time, the island’s unique location and new full-day festival pass format allowed FODI-goers to attend a number of the 31 sessions and delve deeper into different topics and viewpoints while enjoying talks and panels, art installations, ethics workshops and even a touch of cabaret!

Even the master-of-all-trades, Stephen Fry, couldn’t avoid the glamour. A standing ovation roared through Sydney’s Town Hall for his delivery of the inaugural keynote, The Hitch. In honour of his dear friend, the late Christopher Hitchens, Fry had the sold-out venue in oscillating between stitches of laugher and solemn agreement when he lamented the lost art of disagreement in an age of deepening extremes.

Thinkers from around the globe tackled issues of truth, trust and technological disruption, including Caliphate podcast host and New York Times ISIS foreign correspondent Rukmini Callimachi, British conservative commentator Niall Ferguson, AI man-of-the-moment Professor Toby Walsh, and pop-culture savant Chuck Klosterman.

The sold out festival drew crowds of over 16,500 seats across the weekend, with #FODI trending across social media channels all weekend.

The Centre is enormously proud of this festival which we started a decade ago to provide a space to talk about the issues that divide and baffle us without tearing tearing ourselves and each other apart. And we’re thrilled it’s been a continued success in 2018 with a fantastic new partner, The University of New South Wales Centre for Ideas, and a fitting new home.

If you weren’t able to join us, many of our sessions were recorded and we’ll be releasing them over the coming weeks and months.

We’ll keep you posted in our enews or follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn for more release updates.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ANZAC day lie

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is modesty an outdated virtue?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

From capitalism to communism, explained

From capitalism to communism, explained

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 NOV 2018

Everything, from your clothes to your phone to the train you last caught, has gone through what economists call ‘the means of production’.

This is the way a commercial good or service is created and sold, all the way from its raw materials to how it arrives in your hands… or to your platform.

Most of these things (also referred to as capital) can only be created as a result of collective effort. No individual can reliably ensure everyone in a country of twenty-five million has a safe way to dispose of their waste or a place to go to when they’re sick. One person can’t even meet the most basic requirement of that population and ensure sure everyone is fed.

Of course, these things cost money to maintain. Whenever cost is involved, people want to know who pays. This is where it gets hairy. If one person owns ‘the means of production’, they have to pay for everything – and keep any and all profit made. If everyone involved owns ‘the means of production’ collectively, they share the cost – and any profit.

This is where the branches of different economic systems begin.

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic systemwhere the ‘means of production’ and resulting capital are owned by private individuals and businesses. It is based on voluntary relationships of supply and demand instead of centralised (usually government) planning.

This system is rooted in classical liberal philosophy and its conception of the rational, freethinking, autonomous individual. It claims market competition forces people to act in a way that benefits others, regardless of their intention.

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system borne out of opposition to capitalism where the ‘means of production’ are collectively owned and shared. It prioritises production for use rather than profit and achieves this through centralised planning – like a government.

The value of whatever is produced is determined by the amount of time and labour required, not market supply and demand. Socialism claims sharing resources and work according to need, rather than competition, creates a more equitable and secure society.

Communism

Communism is a utopian political economic system where a society is reorganised without hierarchy, states, money or class. The ‘means of production’ are shared communally and private property is non-existent or severely restricted. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published the seminal political pamphlet on this, A Communist Manifesto in 1848.

Communism’s modern adherents claim it has not happened yet, while its critics cite Maoist China, Stalin’s Soviet Union, the Cold War, and many other historical crises to signal its danger.

Fascism

Fascism is an economic system based on self-sufficiency of the state, ethnic purity, and one-party ownership over the means of production. There’s usually a dictatorial leader and little to no tolerance of political opposition. Fascism claims the strength of a nation comes from unity and unity depends on fixed identities.

Though commonly associated with Nazi Germany, many other countries have been considered fascist at some point too, such as Brazil, Iraq and Japan.

Laissez-faire

Laissez-faire translates to ‘leave alone’ or ‘let them do’. Laissez-faire is an economic system that leaves transactions and trade free from government regulation, subsidies, tariffs, and privileges. It claims the economy is a natural system and the market is an organic part of it. Government interference hinders something nature can mediate.

Which economic-political system is best?

When discussing what economic system we prefer, it’s important to know what we’re talking about. The economies of most modern countries today are rarely pure capitalism or pure socialism. Most have a mixed capitalist system where private individuals or businesses make profit off labour, while operating within government regulations.

At the bare bones of economic theory, you find philosophy. Questions like ‘What is the purpose of government?’, ‘What is a human right?’, ‘What can we expect from our relationships?’, or ‘What does equality and justice look like?’ inform the different perspectives that manifest into policy.

Which one would you stand for?

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe our friends

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 18 NOV 2018

Your child is getting married. A mixture of pride, grief and trepidation have been gathering steam for a while now.

You don’t know how you’re going to feel on the day, but when you see your child go through one of the most ubiquitous rites of passage there is, you can’t guarantee there won’t be tears of love.

Except for one snag.

You don’t like their fiancé.

It’s heartbreaking. What should have been a moment of elation at your child’s joy is soured. You don’t understand why they’re making such a huge commitment to their partner or how you will live with that choice.

Perhaps you don’t think they’re good enough, or you don’t get along with them as much as you’d like. Maybe you see them bringing unhappiness into your child’s life – now or in the future. They might have strange attitudes to parenting or relationships. They might seem plain dangerous. Either way, there’s one question you’re asking…

What should you do?

In this situation, consider what a good parent looks like. Do they support, protect, and nurture their child? Do they allow them to make their own mistakes? Are they honest and fair?

Being honest may mean causing great hurt. Being fair may mean accepting the consequences of your child’s independence. Protecting your child may mean treating your fears as truth. But to what end? And by what means?

Wedding dilemmas splitting you in two? Book a free appointment with Ethi-call. A non-partisan, highly trained professional will help you see through chiffon to make decisions you can live by.

On one hand, what actions present you as the person you want to be? Are they the actions of someone courageous, patient, and wise? Or someone petty, panicky, and controlling?

On the other hand, what actions risk damaging the relationship between you and your child? Or your future child-in-law? What situation necessitates speaking up? Or more drastic measures?

If you decide your concerns aren’t that serious, is there a way you could use this situation to build a stronger relationship with your child and a better understanding of the partner they love?

A lot of the time, when we are faced with an ethical dilemma, we see in binaries. Black or white, either or. Taking the time to slow down our thinking and consider the situation in different ways can help new pathways emerge – even if that means stepping back and living with the decisions another person has made.

So, before you end up expressing your reservations in panic, blame, and threats to boycott the wedding, take a breath. Step back, contemplate who you aspire to be as parent, what actions you feel are right and available to you and get creative.

If you or someone you know is experiencing violence and need help or support, please contact 1800RESPECT. Call 000 for Police and Ambulance help if you are in immediate danger.

Ethi-call is a free national helpline available to everyone. Operating for over 25 years, and delivered by highly trained counsellors, Ethi-call is the only service of its kind in the world. Book your appointment here.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ad Hominem Fallacy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

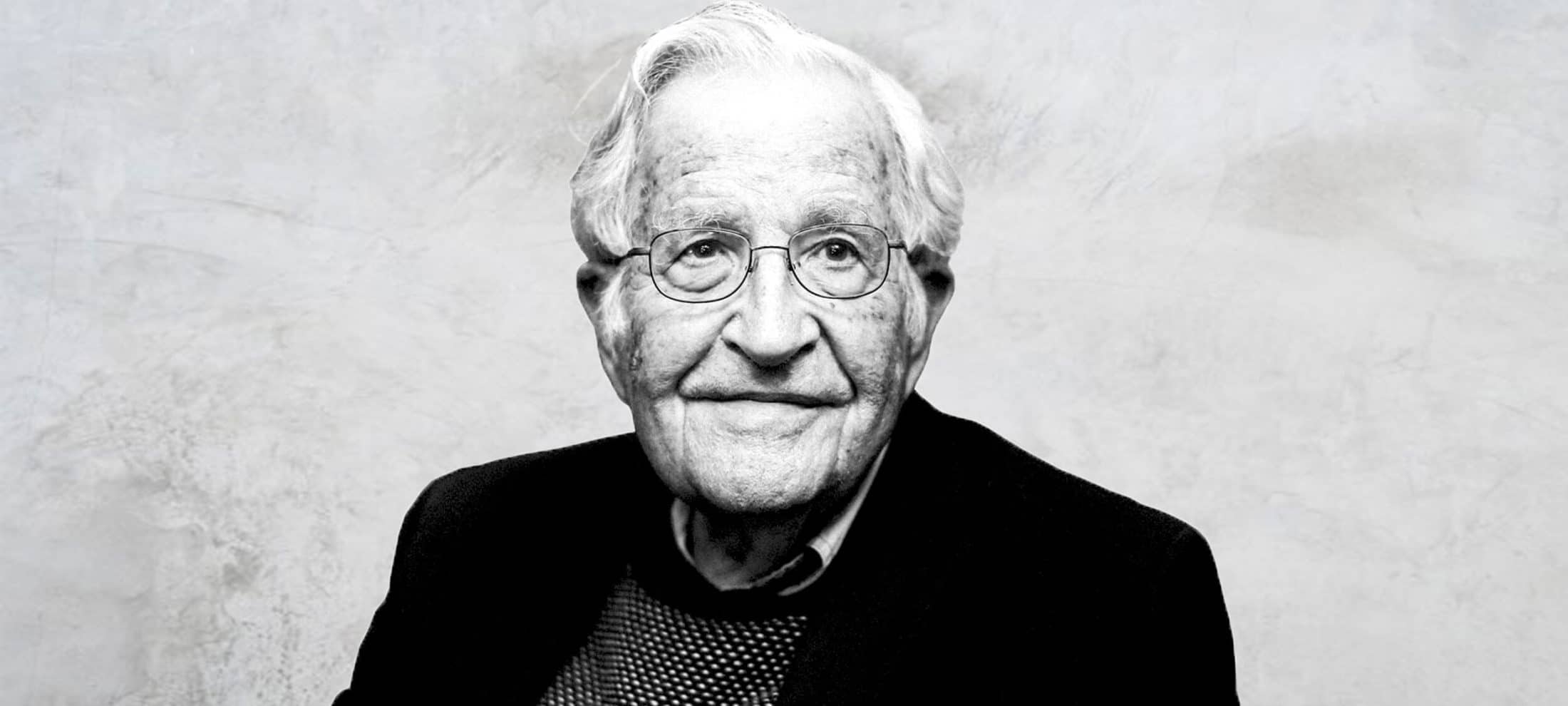

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 12 NOV 2018

Noam Chomsky (1928—present) is one of the foremost scholars and activists of our time.

With over a hundred books, thirty honorary degrees, and a generation of aspiring leftists behind him, Chomsky’s life puts a practical lens on the motto ‘protest is patriotic’.

The human tendency towards freedom

Chomsky earned a PhD in linguistics for his theory of “universal grammar”, a theory where all people are “born knowing” shared properties that underpin all human language. These properties, which create what he calls a “language acquisition device”, are what helps babies pick complex languages up instinctively.

According to Chomsky, while language’s laws and principles are fixed, the manner in which they are generated are free and infinitely varied. This view of human nature is one that runs through Chomsky’s attitudes to linguistics or politics: we must protect the innate human tendency towards freedom.

Pessimist of intellect

Chomsky’s opposition to war and totalitarianism started early. He wrote his first paper on the threat of fascism at ten. He opposed the Vietnam War while working at MIT, a military-funded university. He called Gaza the world’s “largest open-air prison” and said the US bears full responsibility for Israel’s war crimes.

Chomsky’s public denunciations of US foreign policy in Central America and East Timor, its interference in Middle Eastern elections and the shoot-first-ask-later’ type of diplomacy have drawn widespread ire and admiration. At the height of his fame in the 70s, it was discovered the CIA was keeping tabs on him and publicly lying about doing so.

Noam Chomsky’s consistent and vocal criticism of the US government comes from the belief that he, as a member of that country, holds a moral responsibility to stop it from committing crimes. That, and it’s far more effective than criticising a government that isn’t responsible for him.

“States are not moral agents; people are, and can impose moral standards on powerful institutions.”

Manufacturing consent

In what is arguably Chomsky’s most famous work, ‘Manufacturing Consent’, he outlined mainstream media’s complicity with government and business interests. He traced the capitalist formula of selling a product at a profit to the highest bidder in relation to the media. Here, people are the product and advertisers are bidding for our attention. Compare this with the monopoly social media has over our time and the ensuing competition for available ad space, and you’ll notice this line of argument growing in prescience.

Chomsky argued the advertising market is shaped by the external conditions of the state. It’s in their best interests to placate their ‘product’ and water down anything that would spur them to act against it. Any dissenting opinion is either ignored or presented as an anomaly. This is anti-democratic, said Chomsky, for a nation is only democratic insofar as government policy accurately reflects informed public opinion.

“If we don’t believe in free expression for people we despise, we don’t believe in it at all.”

Speak truth to power

Fred Halliday, an Irish academic, has criticised Chomsky for overestimating the power and influence of the US. Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker, Oxford historian Stephen Howe, and linguist Neil Smith, have called him a fierce and aggressive moral crusader, who dismisses critics as unqualified, mistaken, or even “charlatans“.

Today, Chomsky is outspoken on what he considers the two greatest threats to humanity: nuclear war and climate change. But with NEG scrapped, the Doomsday Clock inching to midnight, and Congress split, it looks unlikely that decisive action against either of these threats will be carried out anytime soon.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Employee activism is forcing business to adapt quickly

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships