David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 17 JAN 2025

David Lynch’s Blue Velvet – the film that turned an outsider auteur into something approaching a genuine cultural sensation – is, even after all these years, a hard watch.

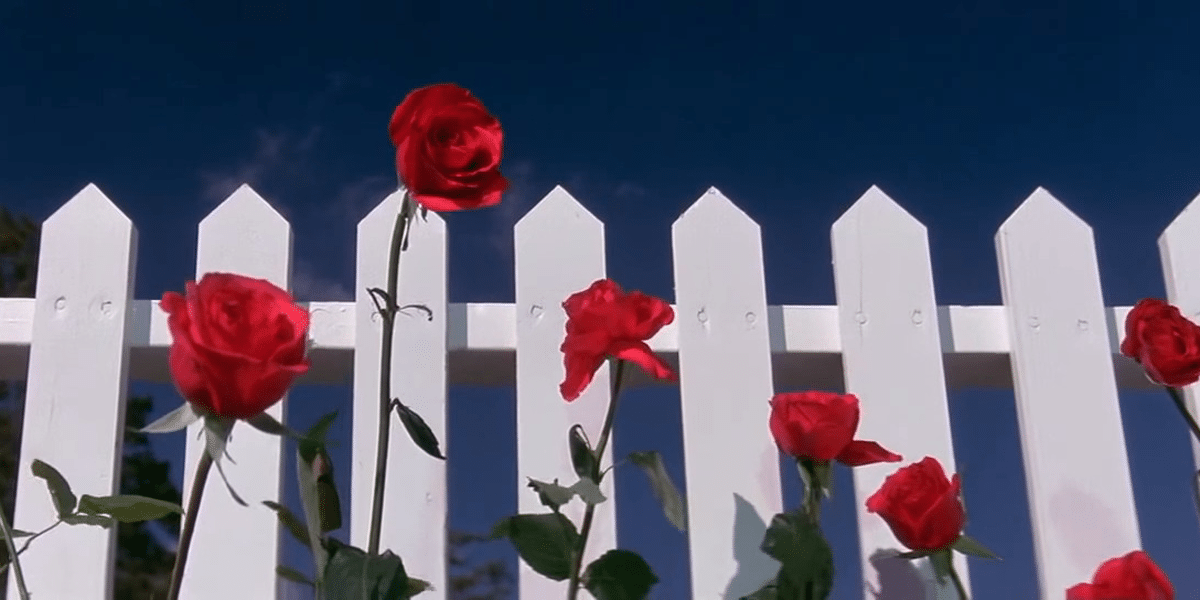

The film sets up its thesis almost immediately. A montage of quaint images of small-town life, all blue skies and white picket fences, is disrupted by tragedy – the father of the film’s hero, Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) collapses in his yard, killed by a heart attack. The man’s dog laps at the hose clung in his dead, tight hands. And then Lynch’s camera, still exploring, does something both beautiful and terrible: it burrows under the soil, where a nightmarish cacophony of insects forage.

So there it is, Blue Velvet’s message – that beneath Americana, with its bright smiles and cups of coffee, lies horror. From that starting point, rape, torture and abuse abound, as Jeffrey’s voyeurism sends his path crashing into the orbit of Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper, in one of cinema’s most terrifying performances, all gritted teeth and mummy issues). We watch Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) get tortured in various ways; we see Jeffrey beaten and humiliated. And perhaps most unsettlingly of all, we come to realise that the likes of Frank, a personification of pure evil, are more plentiful than we might ever want to believe. Even, if not especially, here, where the skies are blue.

The world is wild at heart and weird on top

Much has been made of this quality found in the films of Lynch, who died today after a battle with emphysema – the contrast between ethical virtue, and deep ethical horror. Throwing up these two disparate forces – good and evil – was the modus operandi of Lynch’s one-of-a-kind career.

Twin Peaks, his hit television show, unraveled the angelic exterior of murdered teenager Laura Palmer, and pit her against another of Lynch’s satanic figures, the supernatural drifter Bob. Wild at Heart, one of the more underrated films he ever made, plunged a loving young couple, Sailor and Lula, into an impossibly evil world. And The Elephant Man, a black-and-white muted howl of pain, saw a man with disabilities try to find hope amongst objectification and cruelty.

But what is not often discussed about Lynch is that he did find beauty, time and time again. Contrary to what some have written, Lynch’s veneer of smiles and blue skies wasn’t some ironic posturing, established merely to make the horror more horrifying. Other filmmakers have untangled the way that evil thrives in darkness, out of sight – that’s not what made Lynch special.

Lynch’s power – his genius, even – is that he believed fully in both of the forces that make the world what it is, the darkness and the light.

This is a rare sort of ethical dialectics: rare both in art, and in our personal lives. Believe too deeply in the evil of the world, and you will simply never get out of bed. Ignore that evil, and strive forward as though it isn’t there, and you will fall prey to an ignorance that will make you a poor ethical actor. The real trick in all things is to understand that truth, if we ever find it, exists in the middle of extremes.

Hence the model of the archetypal Lynch hero: Dale Cooper (MacLachlan, again), the handsome, profoundly odd detective hero of Twin Peaks. Dale has a goofy, almost unrepentant enthusiasm. He loves coffee; he loves pie; he loves the town of Twin Peaks. He’s all broad smiles, and dorky thumbs up, perpetually grinning to the small town residents that come to love him. But this optimism doesn’t exist in spite of the darkness of the world – it exists because of it.

That understanding is expressed through his deep affection for Laura Palmer, the dead young woman he never met. The more he learns about Laura, believed by the town to be the perfect all-American girl, the more he loves her, even as he comes to see the precise shape of her demons.

Lynch’s lesson is contained here. Cooper doesn’t choose to believe in the goodness of people at the expense of acknowledging their capacity for great harm. He understands that the world is built, in many ways, for cruelty to flourish; for abusers to thrive, for casual unkindness to go unremarked upon. And he also understands that, surprisingly, time and time again, human beings will decide to love each other.

The art life

This complicated optimism was also at the heart of Lynch’s deeply inspiring life outside of filmmaking. Like Cooper, Lynch was a famous lover of little treats, the kind of tiny slithers of goodness that aren’t just a distraction from the world – they are the world. There are countless memes of Lynch expounding the beauty of a good cup of coffee; enjoying two cookies and a Coke in the back seat of a car; and, perhaps most movingly of all, speaking lovingly of the importance of what he called “the art life.”

For Lynch, the art life was painting, thinking, and making things with your hands. “I had this idea that you drink coffee, you smoke cigarettes, and you paint, and that’s it”, Lynch said once, happily. There is horror in this world, but being an artist isn’t just an aesthetic choice – it’s an ethical one. Being an artist means being curious; looking; creating.

Rather than being swamped by the inexorable downward slide of humanity, the artistic life allows one to see the things that make us, at the end of the day, so blessed. So loved.

Blue Velvet contains that hope in its final scene. After taking a long drive through hell, the film wraps up not with an image of suffering or pain. Instead, one of its last shots is a robin sitting on a branch. A robin – that most ordinary of birds, so small as to be invisible, but a symbol, built up over the course of the film, representing love itself. “Maybe the robins are here,” Jeffrey says, cautiously. But, despite it all, they are.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Sex ed: 12 books, shows and podcasts to strengthen your sexual ethics

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 7 JAN 2025

If I were a reviewer at a writers’ festival and I spotted an author whose work I’d praised – but also criticised – I’d be tempted to look the other way.

But, far from avoiding Christos Tsiolkas at last year’s Canberra Writers’ Festival, literary critic and Festival Artistic Director, Beejay Silcox chose to share the stage with him.

When asked if she felt uncomfortable, Silcox said that because she felt she’d done her job well – reflecting on the work, dealing with it on its own terms, choosing her words carefully – she didn’t. If she couldn’t be honest about “the loveliest man in Australian literature”, she didn’t deserve her job.

She did, however, describe that job as “inherently uncomfortable”. It’s the reason people often call her “brave”. But Silcox doesn’t share their view. “If what I do counts for bravery in our culture, we are f*cked,” she told the audience. “I know what bravery looks like; I’ve seen brave people. I’m just being honest.”

Point taken. There’s a difference between being honest and being brave. Honesty might require bravery, but the words aren’t interchangeable. If we use words like “bravery” too readily, we broaden its definition and reduce its potency.

It was the expanded application of certain words, that led psychology professor Nick Haslam to coin the term “concept creep”. More than a decade ago, he started noticing the widespread adoption of certain psychological terms in non-clinical settings was broadening people’s conceptions of harm. In a recent ABC interview, he said more expansive definitions of terms like “abuse” and “bullying” have had clear advantages, such as making it easier to call out bad behaviour. But mistakenly framing an unpleasant experience as “trauma”, or speaking as if ordinary worries constitute anxiety disorders, can make people feel, and become, more fragile.

This year, Australia introduced legislation that gives employers a positive duty to protect workers from psychosocial hazards and risks. It’s right to recognise that psychosocial harm can be as damaging as physical harm, but it’s important to understand what psychological safety isn’t. As Harvard business school professor Amy Edmondson stresses, it isn’t “feeling comfortable all the time”. It isn’t simply safety from discomfort, it’s safety to engage in conversations that might be uncomfortable. A manager should be able to gently raise an issue with an employee that might make them feel uncomfortable, without being accused of deliberately “violating” their safety – and vice versa. But I’ve heard managers, and educators, express concern that even well-intentioned, carefully delivered, feedback, could be perceived as an attack.

We can be uncomfortable and still be safe. If we lose this distinction, if managers in workplaces and teachers in schools, parents in the home and politicians in parliament, feel obliged to keep everyone comfortable all the time, we’ll end up in dangerous territory. We’ll be less able to express our views, and less able to hear each other out, less able to learn from each other.

Honest, measured, criticism plays an important role in society. We need to value it; even (perhaps especially) if it’s hard to hear. We also need to recognise that avoiding exposure to any and all discomfort will only heighten the sensation; and consider the merit, case by case, of facing it.

So, what might this look like?

C.S Lewis said that if you look for truth, “you may find comfort in the end”, but if you look for comfort, “you will not get either comfort or truth”. He wasn’t talking about performance reviews or reports or assignments, but the principle is still relevant.

If I seek the truth about my performance at work, I might find ways to improve it, gaining competence and confidence. A by-product will be a broader comfort zone. If I only want to hear praise, I can look for people who will only give it or find ways to only get it. I can avoid trying if I think I’ll fail, or I can start cheating to ensure success. In the short-term I might feel better, but over time, I’ll be progressively worse off.

We need more expansive conversations – more discomfort which, through exposure, will expand our comfort zones and increase our resilience. Silcox talks about how we need fewer “gatekeepers” – those who close doors and shut down important conversations – and more “locksmiths” – those who open them.

We can start by considering the way we speak, and think, and act. Are we using words that make others more cautious, risk averse, fearful, fragile, than they need to be? What about when talking to ourselves? Are we so focussed on staying safe from risk, that we forget about how many risks are safe to take? With this in mind, we can resolve to sit with discomfort, to recognise the doors that it can open, that comfort can’t. We can welcome feedback, even ask for it; embrace challenges, even set them for ourselves; replace complete avoidance, with strategic exposure. And if we’re in positions of authority, we can give those we oversee genuine permission to try and fail and try again.

It’s natural to avoid discomfort. But if we continually avoid what’s hard, it will feel harder still. If we want to talk about what matters and do it well; exercise moral courage; make a difference in the world – we’ll have to expand our comfort zones, not narrow them. We’ll have to take some risks. But do you know what else is risky? Sitting still.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to help your kid flex their ethical muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to pick a good friend

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Only love deserves loyalty, not countries or ideologies

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

The ethics of pets: Ownership, abolitionism and the free-roaming model

The ethics of pets: Ownership, abolitionism and the free-roaming model

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY William Salkeld 16 DEC 2024

“If there are no dogs in heaven, I want to go where they go”, said the American performer, Will Rogers.

It is no secret that we are deeply connected to the animals we keep as pets. In Australia, most pet owners would like to think they treat their animals well. 52% of Australians consider their pets to be family members, and in 2021 Australians spent $30.7 billion on food, healthcare, and enrichment for their cats and dogs.

Studying animal ethics, I used to believe that pet ownership was a good thing. Following the arguments of moral philosopher Christine Korsgaard and many others, I saw it as a mutually beneficial situation. We provide our animals with the necessary conditions for a good life, such as food, shelter, healthcare, love and attention. In return, they provide us with companionship and countless other life-affirming benefits.

As long as we can provide our pets with the kind of life that is good for them, then having pets is a good thing, I reasoned. After all, how could I deny that my family’s Golden Retriever, Ruby, lived a charmed life full of play, food, and affection? As I would soon find out, the ethics of pet-keeping is far more complicated than ensuring our furry friends are ‘well taken care of’.

My view about pets was turned upside down after listening to a podcast with legal scholar and animal ethicist Gary Francione. Francione is an abolitionist, meaning that he believes that we should abolish all use and ownership of nonhuman animals, including pets. To understand this view, it is first important to understand the history of domesticated animals and pets.

Domesticated animals are those animals like dogs, cats, or sheep who have adapted or ‘tamed’ because of or by humans. While the jury is still out on how wolves initially interacted with humans to become dogs, humans have subsequently spent millennia forcibly breeding dogs to make them less aggressive, ‘cuter’, or specialised in some activity like cattle herding. Or, in the case of my family’s Golden Retriever, Ruby, it seems she has been bred to chew up sofas and love carrots (don’t ask).

As Francione puts it, we have domesticated dogs and cats into a state of perpetual childhood where they are dependent on us for basic care. Yet, unlike children, cats and dogs don’t grow up and become independent; they remain in a state of dependency for their entire lives.

The animals we keep as pets are a subset of domesticated animals. The concept of pet ownership in Western countries is surprisingly recent, beginning in the Victorian era. Our entitlement to owning pets has not existed throughout history, meaning we should be critical of current ethical attitudes towards pets.

For abolitionists like Francione, the problem of pet ownership is twofold. One, the state of dependency is problematic because we have bred animals to become dependent on us. Imagine if someone raised their child to be completely dependent on them and to never reach true adulthood; we would likely call it emotional abuse. Yet in the case of pets, it is considered ‘proper training’.

Second is the problem of ownership and possession. Animals (including pets) are treated as property in the law. It’s even in the name: ‘pet ownership’. Most of us know that animals are sentient, and perhaps even that they are individuals with rights. However, if this was truly the case, then it would be nonsensical that an animal could be ‘owned’ as property in the same way it is morally outrageous for a human to be owned.

For these two reasons, abolitionists like Francione think that if we could wave a magic wand, we should remove all domesticated animals like cats and dogs who depend on us from existence. While we should adopt and care for the current animals that are already alive, we should also aim to abolish the institution of owning pets.

The abolitionist position is confronting and uncomfortable. I love my dog Ruby, and I was initially defensive against Francione’s argument. Has my family really been doing something wrong by pouring hours of our lives and thousands of our (my parents’) dollars into caring for a dog who we treat as a member of a family? Even if we have not personally been doing anything wrong, the world without cats and dogs that Francione envisages seems like a slightly less happy world.

I was struggling with this dilemma when my partner and I met a cat at a guesthouse in Malaysia’s Cameron Highlands, curled up in a box in the corner of the reception. When we asked the guesthouse owners what his name was, they said that he didn’t have a name yet because he only arrived three weeks earlier.

He, the cat, had picked them. In return for his company, the guesthouse owners gave him as much kibble as he would like and took him to the vet. On the same trip, I also learned that in Türkiye, many people have a ‘tab’ at the vet they use for vagabond cats who choose to live with them. This framework of domesticated animals without ‘owners’ is what I call the ‘free roaming’ model, an idea tentatively welcomed by animal studies scholar Claudia Hirtenfelder that, as Eva Meijer argues, acknowledges the agency of nonhuman animals.

Perhaps a more familiar example of a free-roaming animal is the life of the eponymous dog from the beloved Australian film, Red Dog. In the film, Red Dog is no one’s pet. Rather, he is cared for by the employees of a mine in Western Australia’s Pilbara and eventually decides to live with an American man named John Grant. Red Dog has agency, and [spoiler alert] uses that agency to travel across Australia in search of John after his premature death.

The key difference between free-roaming domesticated animals and pets is that these animals are not owned. Yes, many free-roaming cats and dogs may still depend on some human care, but they have a choice in how and from whom they receive that care.

The free-roaming model is not perfect, however. According to the Humane Society, 25% of outdoor (commonly referred to as ‘feral’) kittens do not survive past 6 months. This is not the case for kittens bred in captivity. And while some cats are lucky, like the one we met in Malaysia, many endure lives of illness and famine. And, as Korsgaard points out, domesticated cats are a predatorial threat to native wildlife, which is why, for example, they are not allowed outside without a leash in the Australian Capital Territory.

For the free-roaming model of animal companionship to work, we would have to make our urban spaces more hospitable to other animals. There would have to be a significant attitude shift in our tolerance of animals in public spaces where we usually don’t see them.

Until that day, perhaps the best thing we can do is adopt pets from shelters like the RSPCA, rather than breeders who perpetuate the institution of animal dependency and pet ownership. However, the free-roaming model gives hope for a post-pet world. As Korsgaard puts it:

“There is something about the naked, unfiltered joy that animals take in little things—a food treat, an uninhibited romp, a patch of sunlight, a belly rub from a friendly human—that reawakens our sense of the all-important thing that we share with them: the sheer joy and terror of conscious existence.”

This article won the 2024 Young Writers’ Competition 18-29 category.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Read before you think: 10 dangerous books for FODI22

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

‘The Zone of Interest’ and the lengths we’ll go to ignore evil

BY William Salkeld

William Salkeld is a PhD candidate with the school of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University, researching interspecies democratic theory. He is interested in animal and environmental ethics, political philosophy, animal minds and cognition, and moral philosophy.

Rethinking the way we give

Whether it’s helping out a neighbour in need, assisting a stranger living rough on the streets or being asked at the checkout to donate $2 to charity, we are all, at some point, involved in the action of giving.

The giving of service. The giving of time. The giving of money. We often find ourselves giving from a place of good intention, but not fully understanding the consequences of our actions.

Away from home, when travelling in a developing country, it’s especially difficult to ignore the begging children on the streets, families living in overcrowded homes and poverty, the absence of healthcare and the poor state of schools.

In 2006, Australian philanthropist Tara Winkler witnessed the distressing realities of children living in poverty whilst visiting a Cambodian orphanage. She was so moved that she returned a year later with money she had fundraised, ready to work hard to improve the children’s quality of life. During her time as a volunteer, she discovered that the orphanage’s director was abusive and misappropriating donations, an occurrence not unheard of in the industry. Winkler also learnt that most ‘orphans’ still had their families but were living in these institutions to escape the poverty cycle.

Attempting to save these children, Winkler established her own orphanage in 2007, only to realise it was further fueling Cambodia’s widespread misuse and exploitation of orphanages, causing harm to children and separating families. She has since developed the Cambodia Children’s Trust, an organisation that aims to address root causes of poverty and family unit breakdown through social work and locally based initiatives involving education and healthcare, providing sustainable and positive futures for at-risk communities.

By spotlighting this story, I am not aiming to discourage the act of giving but rather to motivate individuals to have a more considered approach on how we give and to whom. As highlighted in philosopher Peter Singer’s book, The Life You Can Save, ‘perhaps those who do not research think that it will be too difficult to find out what charities offer better value, so they may as well give to whatever charity last caught their eye’. This is reflected in Australia’s Giving Report from 2019, when it was recorded that 41% of Australians would donate more money in the next 12 months if they better understood where their money would be spent, whilst 23% hoped for more transparency about the cause and its regulations.

So, how can we shift these figures and guide people toward more impactful giving choices?

Let’s take a look at UNICEF. According to their Donate Where Need is Greatest appeal, of each dollar donated, 80 cents is specifically directed towards helping vulnerable children, 14 cents to essential fundraising costs and six cents to administration.

Given these figures alone, it’s difficult to assess the lasting impression of this particular campaign, so we have to look further. We discover their main goal is to break the vicious cycle of poverty by providing small initiatives that will have beneficial, long-term effects. A donation of 84 dollars equates to 84,000L of clean drinking water made accessible to some of the most at-risk children and their communities around the world. This small change results in the difference between a safe and healthy child to one who might face life-threatening illnesses through contaminated water supplies. At this point, we can gauge that donations will be properly utilised by this cause and will be incredibly significant to the lives of these children, stressing the importance of who we give to rather than a quantitative measure.

However, it’s a big ask for everyday people, simply trying to do their part, to pause and assess how their time and money could best be spent. Sometimes, it is just simpler and seems just as effective to donate to any charity that loosely relates to an ethical issue that matters most to us. To make better decisions when it comes to giving, online organisations such as The Life You Can Save and GiveWell can help evaluate and recommend high-impact, cost-effective and evidence-based charities, proving that everyone has the potential to make a meaningful impact.

By taking a few extra measures to reflect and consider where and how we direct our intentions, we can make more ethical choices that result in sustainable outcomes and give to others in a way that transforms their lives for the better.

This article won the 2024 Young Writers’ Competition Under 18s category.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

LISTEN

Society + Culture

Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI)

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Freedom of expression, the art of…

BY Serei Bayley

Serei is a 15-year-old high school student currently attending Redlands. Interested in commerce and history subjects, she has aspirations to study law or business at a university overseas. She loves travelling and spending summer days at the beach. Earlier in 2024, Serei visited Cambodia, where she was inspired by her interactions with various NGOs, which motivated her to write this piece.

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 6 DEC 2024

In 2001, Marcellus Williams was convicted of killing Felicia Gayle, found stabbed to death in her home in 1998.

Over two decades later, he was given the death penalty, directly against the wishes of the prosecutor, the jury and, notably, Gayle’s family.

Cases like this draw our attention to the nature of punishment and its role in delivering justice. We can think about justice, and hence what is just punishment, as a question about what we deserve. But who decides what we deserve, and on what basis?

There are many ways that people think about punishment, but generally it’s justified in some variation of the following: retribution, deterrence, rehabilitation, and/or restoration. These are not all mutually exclusive ideas either, but rather different arguments about what should be the primary purpose and mode of punishment

Purposeful Punishment

Punishment is often viewed through the lens of retribution, where wrongdoers are punished in proportion to their offenses. The concept of retributive justice is grounded in the idea that punishment restores balance in society by making offenders ‘pay’ in various ways, like prison time or fines, for their transgressions.

This perspective is somewhat intuitive for most people, as it’s reflected in our moral psychology. When we feel wronged, we often become outraged. Outrage is a moral emotion that often inspires thoughts of harming the wrongdoer, so retributive punishment can feel intuitively justified for many. And while it has roots in our evolutionary psychology, it can also be a harmful disposition to have in a modern context.

The 18th-century philosopher Immanuel Kant strongly defended retributive justice as a matter of principle, much like his general deontological moral convictions. Kant believed that people who commit crimes deserve to be punished simply because they have done wrong, irrespective of whether it leads to positive social outcomes. In his view, punishment must fit the crime, upholding the dignity of the law and ensuring that justice is served.

However, there are many modern critics of retributivism. Some argue that focusing solely on punishment in a retributive way overlooks the possibility of rehabilitation and societal reintegration. These criticisms often come from a consequentialist approach, focusing on how to create positive outcomes.

One of these is an ongoing ethical debate about the role of punishment as a deterrent. This is a consequentialist perspective that suggests punishment should aim to maximise social benefits by deterring future crimes. This view is often criticised because of its implications on proportionality. If punishment is used primarily as a deterrent, there is a high risk that people will be punished more harshly than their crimes warrant, merely to serve as an example. This approach can conflict with principles of fairness and proportionality that are central to most conceptions of justice. Some also consider it to be a view that misunderstands the motives and conditions that surround and cause common crime.

Other, more contemporary, consequentialist views on punishment focus on rehabilitation and restoration. Feminist philosophers, such as Martha Nussbaum, have proposed a broader, more compassionate view of justice that emphasises human dignity. Nussbaum suggests that a purely punitive system dehumanises offenders, treating them merely as vessels for punishment rather than as individuals with the capacity for moral growth and change.

They argue that this dehumanisation is a primary factor in high rates of recidivism, as it perpetuates the cycle of disadvantage that often underpins crime. Hence, an ability for change and reintegration is seen by some as crucial to developing pro-social methods of justice that decrease recidivism.

Importantly, these views are not inherently at odds with traditional punishment, like prison. However, they are critical of the way that punishment is enacted. To be in line with rehabilitative methods, prisons in most countries worldwide would need to see a significant shift towards models that respect the dignity of prisoners through higher quality amenities, vocations, education, exercise and social opportunities.

One unintuitive and hence potentially difficult aspect of these consequentialist perspectives is that in some cases punishment will be deemed altogether unnecessary. For example, if a wrongdoer is found to be impaired significantly by mental illness (e.g. dementia) to the extent that they have no memory or awareness of their wrongdoing, some would claim that any type of retributive punishment is wrong, as it serves no purpose aside from satisfying outrage. This can be a difficult outcome to accept for those who see punishment as needing to “even the scales”.

Justice and Punishment

The ethical implications of punishment become even more complex when considering factors like bias and the reality of disproportionate sentencing. For example, marginalised groups face more scrutiny and harsher sentences for similar crimes, both in Australia and globally. This disparity is often unconscious, resulting in a denial of responsibility at many steps in the system and a resistance to progress.

If punishment is disproportionately applied to disadvantaged groups, then it is not just. The ethical demand of justice is for equal treatment, where punishment reflects the crime, not the social status or identity of the offender.

Whether our idea of punishment involves revenge or benevolence, it’s important to understand the motivations behind our convictions. All the sides of the punishment spectrum speak to different intuitions we hold, but whether we are steadfast in our right to get even, or we believe an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind, we must be prepared to find the nuance for the betterment of us all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

3 Questions, 2 jabs, 1 Millennial

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Critical thinking in the digital age

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Daniel Finlay 28 NOV 2024

Yesterday I crossed the street to avoid talking to an acquaintance.

Not because I don’t like them. Not because I was in a rush. But because I often feel a deep aversion to participating in small pleasantries or having to socialise when I’m mentally unprepared.

This is only one in a list of anti-social tendencies I’ve noticed myself developing during my adult life.

A lot of them seem more mundane than crossing the street, too. When’s the last time you took off your headphones and casually spoke to a stranger on the train or at the shops? Have you gotten to you know your neighbours or your barista? If a small accident happens in public, do you shy away or pretend you didn’t notice?

Community and Individualism

Recently on TikTok, something that’s caught my attention is a renewed focus on the benefits of and desire for community and how that conflicts with our increasingly individualistic mindsets.

Friction between these two ideas seems unavoidable: community involves a focus on the people around you, and individualism involves a focus on yourself. Go too far in either direction and you’ll inevitably begin to neglect the other.

In his video “This is one of my hills”, creator NotWildlin responds to the view held by some that we don’t owe strangers pleasantries. His gripe isn’t necessarily that we do owe strangers anything, but rather that this attitude appeared to be coming from people who were simultaneously frustrated with the lack of opportunity for community around them. Specifically, they had been advocating for more third places.

Coined by the sociologist Ray Oldenburg in his book The Great Good Place, third places are communal public spaces where casual conversation is the primary (but not necessarily only) activity, and the space is neutral, welcoming, cozy, accessible, playful and homely. Importantly, these spaces are separate from the home, our first place, and from work or study, our second place.

These are places where it’s encouraged to interact with strangers, with a sense of openness for conversation and general interaction with local community.

So, NotWildlin’s argument is this:

If you are the kind of person who laments a decline of local community, who wants to build social capital through things like third places, then how can you also justify being habitually anti-social?

Instead of thinking about pro-social habits as something we owe, we should think about them as something we want to develop in the name of community.

This argument honestly rocked me a little, as someone who is becoming increasingly community-minded, while also holding desperately onto my inalienable right to be left alone.

However, it does seem to me, as an extension of NotWildlin’s point, that a focus on third places is a misprioritisation. On a systemic level, yes, there could be more local government support in creating welcoming public spaces to encourage community. On the other hand, many areas in populous Australian cities do have third places that go underutilised. How many younger people do you know that use libraries, public gardens or other community centres? The deeper problem in my estimation is social and cultural.

Keeping the (inner) peace

Once we leave the education system, many people become creatures of habit, and that unfortunately can extend to the way we view relationships and interact with others. We’re less open to even fleeting interactions with strangers, we might be content with our small circle of friends and unenthusiastic about adding to the noise. We have our routines and any effort outside of them can feel like a small burden.

Unfortunately, that spells disaster for building community. Around the same time as NotWildlin, an Australian creator Jordan Stacey posted a video about the relationship between routine and community. She unpacks the idea that community requires compromise in ways that threaten our often highly sought after bubbles of routine, and too often community is neglected in favour of maintaining these routines.

Stacey talks through this with two main points. Firstly, routine is only a symptom of a broader desire for comfort and convenience. The reason that someone might struggle to accept a spontaneous invitation in lieu of their quiet night in watching tv (for example) is the same reason many people avoid interactions with strangers. And to some extent, this seems obvious, natural and maybe even justified. Why would we want to be uncomfortable or inconvenienced?

But arguably, this is a case of wanting to have your cake and eat it too – at least for those of us who envision a time in the future where we’re surrounded by supportive relationships within thriving communities – because as a reciprocal support network, community necessitates intermittent inconvenience.

If we want to develop and be surrounded by relationships in which we can find support, we also have to be willing to forgo some of our solitude and peace and embrace the inconvenience of being pro-social.

Stacey’s second point is that we live in a world that almost necessitates this level of comfort-protection; that causes us to frame these aspects of community as inconveniences rather than incidental aspects of functioning and fulfilling relationships.

“If you’re working 40 hours a week – a nine to five – the only way, for a lot of people, that this is actually maintainable is through a hefty routine.

The systems we live under directly limit our time and put pressure on our leisure. Our routines often block out weeknights to relax and recover and relegate the majority of our social time to the weekend, creating a sense of isolation throughout the week.

It is also, I would argue, the same inner-peacekeeping measure that motivates our aversion to public interactions. Talking to strangers on our commute or in the lift is a similar disruption to our routines – to the books or podcasts or music that get us from point A to point B without having to cast our attention to the people around us.

Creating Community

All this is not to say that we need to start making forced conversation with strangers. As I write, I’m sitting on a quiet train and would frankly be annoyed if I was interrupted by an overly outgoing commuter. And that’s okay, sometimes.

What I think we should take from this discourse, though, is a readiness to confront our own anti-social dispositions when we reflect that we’re consistently prioritising routine or comfort over building relationships.

While we might dream of a world in which we’re surrounded by supportive relationships and vibrant communities, we’re much less conscious of the personal cost of that dream. The reality is, community doesn’t materialise from thin air – it’s built, moment by moment, through countless small interactions and shared experiences. And yes, those moments often come at the expense of our personal comfort and carefully curated routines.

These compromises aren’t things to shy away from, but reminders that meaningful relationships and thriving neighbourhoods are more than just social policy or urban planning – they’re about us. About stepping out of our bubbles. About choosing to inconvenience ourselves in small, deliberate ways that foster connection.

Maybe the next time we feel the urge to shrink into ourselves, we can choose differently, because community isn’t just something we want—it’s something we create. And creating it means showing up, no matter how uncomfortable it feels in the moment.

The question isn’t whether we owe strangers pleasantries – it’s whether we’re willing to invest in the world we want to live in.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When identity is used as a weapon

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Monty Badami 1 NOV 2024

Jill Stark, recently wrote a controversial piece likening athlete Nedd Brockmann’s 1600km charity run to a broader trend of men “repackaging mental health as mental toughness”, where the “blokeification of mental fitness” is “just toxic masculinity rebranded”.

She has since apologised for the headline, acknowledging that it “was reductive and clumsy and failed to capture the complexity of the issue”. But she also received a lot of vitriolic abuse that proved the very things she was trying to call out.

Whilst it’s not new for men to engage in extreme acts to prove themselves, there has been an increase in shirtless men on social media, with rock-hard abs and beards, embarking on extreme ritualistic adventures to reclaim their manhood. Men are going to brutal boot camps to develop their physical wellbeing, mental toughness, and “find their tribe” through a spartan lifestyle, a navy seal mindset and howling at the moon. Beating drums, near-naked wrestling, the rejection of alcohol, drugs, technology, women and other worldly distractions are the homo-social privations in this cult of masculinity, where Jordan Peterson is regularly quoted, and Andrew Tate is tolerated, if not revered.

Whilst I won’t tar Nedd Brockman with the same brush, there’s something about how he’s been received that could be used as a gateway to the manosphere.

The “no pain no gain” movement in men’s mental health, and the performative tribalism that goes along with it, has worrying similarities to the humiliating initiation rituals of university colleges, the military and cults. But it’s not the first time men have desired the return to an idealised “natural”, “tough” and masculine past.

Paradoxically, the term “toxic masculinity” emerged from the mytho-poetic men’s movement of the 80s and 90s. It was an explicit response, by men, to feelings of powerlessness at a time when the feminist movement was challenging traditional male authority. It was an attempt to navigate the social pressures placed upon men to be violent, competitive, independent, and unfeeling.

But toxic masculinity doesn’t simply condemn all men or male attributes. It refers to the rigid and excessive policing of masculine norms, such as dominance, self-reliance, and competition, that are harmful to men, women, and society overall. And this is how the performance of alpha-male, lone-wolf, toughness can be toxic. But we must consider the intent.

Is the focus on toughness an act of self-interest to stroke the ego? Is it necessarily tied to masculinity, and used to dominate other men? Or is it a mechanism for self-understanding, self-growth and service to the community?

How is Brockman’s achievement different to Jessica Watson sailing around the world? Or Grace Tame competing in ultra marathons and processing her trauma? Or Darius Sam, from the Lower Nicola First Nation in Canada, who ran 100 miles to raise awareness around addiction and mental illness, and to grapple with how these issues affected his life?

As an officer in the Australian Army, my training challenged me mentally, physically and emotionally to develop resilience and moral courage. But this was not about glory. My ego actually got in the way when I faced those dark places within. Sitting with my emotions and transcending my ego became a source of profound growth and self-understanding. For Stoics like Aurelius and Epictetus, they taught that resilience comes from within, based on inner values rather than external displays of strength.

When we look cross-culturally, extreme rituals are not only about the promotion of self, or masculinity. Ritual theatre and performance is also a way to create intense social bonds and transcend the self, with adaptive and evolutionary benefits. We can even see this in the strong feelings of community experienced by both men and women who do ultramarathons or cross-fit.

But what troubles me in this discussion is the assumption that external challenges are inherently masculine and performative, and internal ones are somehow feminine and more authentic. It’s a false binary that ignores the fact that this is beyond gender. It ignores how external challenges facilitate the journey within.

But, why do we necessarily associate anger, aggression and competition with masculinity? Why do we associate empathy, nurturing and care with femininity?

I’m not competitive or aggressive. In our home I’m seen as more empathetic. My wife is the opposite. She’s more decisive, and doesn’t like talking about her feelings. Does this make her less of a woman and me less of a man? Of course not. What’s more, we both possess all the qualities listed above, just in different measures.

Essentialist concepts of masculinity ignore the fact that there are many ways to be a man. Whether you define masculinity in “traditional” or “alternative” terms, you are still constraining it, and that can make it toxic.

And so, we need to interrogate the very definition of masculinity itself, so we can safely explore our sex and gender, and find healthy versions of what it means to be human in all its brilliant complexity.

We’re all at different stages of personal growth, so perhaps the answer is not simply “news-jacking” Nedd Brockman, stopping ultra-marathons or ice-baths, and lumping them in the same bucket as toxic “raw-dogging” masculinity. Perhaps the answer is the very thing we want those alpha-males to embody? Perhaps the answer is empathy and compassion?

Rather than pushing these men away, Mike Dyson, founder of The Good Blokes Co, an organisation that runs Healthy Masculinity Retreats, says:

“A lot of men think the conversation about masculinity is negative and dominated by women, so they are disengaging. Nothing is going to change if men are not having this conversation too.”

“We’re seeing a desire of men to explore toughness and resilience – and that’s because our culture of masculinity rewards the performances of toughness. So, we need to meet blokes where they are in order to take them to where they need to go.”

“Rigid masculinity is the thing that gets in the way of true resilience because it stops us talking about our emotions, so we have an opportunity and a responsibility to have a deeper conversation about this with the men in our communities”.

And perhaps that is precisely what Stark and Brockman are allowing us to do right now. We can actually draw men in with the language of mental toughness, and then open the conversation to include other things like service, humility, intimacy, emotional maturity, accountability, calling out your mates, and stopping gender-based violence. And this can be a really important thing to give young men as they navigate the internal and external challenges of what it means to be a man in the world today.

Further resources

Mental Health

Head to Health: https://www.headtohealth.gov.au/

Open Arms: https://www.openarms.gov.au/

Relationships Australia: https://relationships.org.au/

Talk2MeBro: https://www.talk2mebro.org.au/

Community Groups

The Man Walk: https://themanwalk.com.au/

Dads Group: https://www.dadsgroup.org/

Tough Guy Book Club: https://toughguybookclub.com/

Mens Shed: https://mensshed.org/

The Men’s Table: https://themenstable.org/

Immediate Support

Beyond Blue: https://www.beyondblue.org.au/

Men’s Line: https://mensline.org.au/

Lifeline: https://www.lifeline.org.au/

Studies and interactive resources

Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World: https://www.vivekmurthy.com/together-book

The Man Box Study: https://jss.org.au/programs/tmp-research/the-man-box/

The Good Blokes Co: https://www.goodblokes.co/

Healthy Male website: https://www.healthymale.org.au/mens-health-week-2023

For more, tune into the FODI24 panel discussion, Positive Masculinity:

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

BY Monty Badami

Dr Monty Badami is an Anthropologist and the Founder of Habitus, a social enterprise that gives you Lifehacks to be a Good Human! Monty combines evolutionary evidence with cross-cultural research to explain the secret to our adaptability and success as a species. He designs and delivers workshops that help people put more meaning and joy back into their lives.

Schools of thought: What is education for?

Schools of thought: What is education for?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Georgia Fagan 3 OCT 2024

Education is often seen as an economic investment in our future. But philosophers have argued it could be so much more than this.

Education is often seen as a tool that we use to get us other things that we want; we tend to value education instrumentally. We know that the higher our educational attainment, the higher our future income, and most of us see this increase in future economic value as one of the central values of education. We understandably see greater financial security as a means to achieve greater happiness, a way to avoid stress and enjoy a greater sense of freedom and agency in our lives.

But what else could education be for that it seemingly isn’t for at the moment? What other value could it have for ourselves and the communities in which we are embedded?

Many people believe that economic instrumentality shouldn’t overshadow other potential goals of education. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum writes:

“We are living in a world that is dominated by the profit motive. The profit motive suggests to most concerned politicians that science and technology are of crucial importance for the future health of their nations… my concern is that other abilities, equally crucial, are at risk of getting lost in the competitive flurry, abilities crucial to the health of any democracy internally and to the creation of a decent world culture.”

Nussbaum is concerned that a failure to sufficiently interrogate what systems of education should be used for, leaves those systems vulnerable to a corporatisation that neglects their more comprehensive capacities.

Social critic Henry Giroux echoes these concerns, saying:

“You can’t have a democracy without informed citizens. That’s why education has to be at the centre of any discourse about democracy, and it isn’t. That’s where the left has failed. It has failed to run education. They failed because they believe that the most important structures of domination are entirely economic…”.

In 2027 the NSW primary school curriculum will undergo its biggest change in 30 years. Amongst this will be a new focus on democratic roles and the history of voting. Teaching students about democratic systems is useful, but it’s not enough. We must also teach them to interrogate their own beliefs and deliberate with others whose beliefs differ from their own. This is a skill which Nussbaum calls Socratic self-criticism. She describes it as “the ability to transcend local loyalties and to approach world problems as a ‘citizen of the world’; and, finally, the ability to imagine sympathetically the predicament of another person”.

For Nussbaum (and Socrates) education should aim to create citizens who are skilled in thinking for themselves, in reasoning well alone and with others. Similarly, Giroux thinks education should make individuals “aware of their own cultural capital… and their place in the world”. Nussbaum and Giroux both argue that education should not only give students what they need to lead economically comfortable lives, but also ensure that these lives are self-aware, and meaningfully engaged with the world around them.

Both theorists begin to suggest ways in which their theories can be made into practice. Giroux emphasises the need to engage students in discussions and forms of thinking that allow them to consider their own narratives about the world. This requires understanding the ways in which they are situated within it, and how that situatedness may differ from those around them.

This idea echoes Nussbaum’s argument that education should teach students to think critically about their own traditions. Both these proposals require curriculums that directly consider the perspectives of other people and cultures to stimulate critical self-reflection. Questions like: “what do I believe in and what are my reasons for those beliefs?”, “what do I think of the alternative beliefs?”, and finally, “do I or do I not want to change my thinking in this instance?”.

The development of aspects of Socratic self-criticism already exists as a byproduct of education curriculums, but Nussbaum and Giroux are motivating us to consider what it would look like to bring these aims to the centre of schooling. An example may be through the inclusion of a core subject concerning ethical deliberation. The best preliminary example of this sort of subject may be the Primary Ethics subject model. Currently, this is an hour long, weekly class carried out as an opt-in secular alternative to special religious education in NSW primary and secondary schools.

Any such subjects should not be forged as tools to impart ethical dogmas onto young students. Instead, they should be spaces for developing critical thinking skills which arise from debate and deliberation with existing perspectives and counter perspectives.

Education is a hugely powerful system, one which we should thoroughly and frequently interrogate. Are we using this system in a way that aligns with our goals, both local and global? What are those goals, have they recently changed? Are we equipping an entire generation with the tools they require to live comprehensively fulfilling and meaningful lives? The possibilities for our educational systems are boundless and it’s time that we begin realising this.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

READ

Society + Culture

6 dangerous ideas from FODI 2024

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Ethics Centre Nominated for a UNAA Media Peace Award

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Joseph Earp 23 SEP 2024

The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, the 2005 young adult drama film, takes all of five minutes to set up its premise: what if you and your friends discovered the titular pair of jeans, which, despite your differences in size, fit you all perfectly? And, more than that, what if you all decided that these pants had magical behaviour-changing powers?

So far, so teen drama, particularly when the film starts unveiling the emotional canvas the film will play out on. Bridget (Blake Lively) has a crush, and a dead mother; Carmen (America Ferreira) is a child of divorce; Tibby (Amber Tamblyn) is stuck working a dead-end job.

But what is extraordinary about the film is the sensitivity with which it handles what could otherwise be tropes. Each of the heroine’s lives is disrupted by death and loss. They learn they are fallible; that they are subjected to forces they cannot control. They’re not whiny teenagers. They’re young people, making their way through the world – sometimes messily, but always with conviction.

The film is shockingly emotionally nuanced for a work of art made for, and about, teenagers. But what makes it more shocking is how plainly it exposes the absence of similar art for young men. The Sisterhood of The Traveling Pants – and films like it – are a core part of moral education, designed to validate young women in their feelings, both the positive and the negative. So, where is the male equivalent?

Art and moral education

None of this is to say that The Sisterhood of The Traveling Pants need only appeal to young women – the brush with which it paints is broad and vivid enough for those of any gender. But it still remains the case that the film was marketed to, and largely consumed by, young women. It sits alongside Stick It, She’s The Man, Riding In Cars With Boys, and Cinderella Story as part of an early 2000s trend of emotionally adult works directed towards young women. While these are stories are ostensibly about romance, they’re actually about self-discovery and self-possession.

Such films, as philosopher Greta T. Cullen observes, need not necessarily be “morally instructive” – as in, they don’t need to have all the moral answers. Instead, they ignite sympathy. They teach us both about our own world, and the worlds of those around us. As Cullen puts it, they “encourage an awareness of other people, their problems and sufferings.” Through that awareness, we can build a proper moral system – after all, it’s only when we understand how we affect other moral agents that we can decide how to treat them.

That, in fact, is precisely what makes art so important in moral education. The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants isn’t prescriptive – it doesn’t tell us exactly what we should do. In fact, its heroines make more mistakes than most: Tibby, whose life is changed by a young girl with cancer, initially declines to visit her dying friend in hospital. The film isn’t an instruction guide. Instead, it’s a sort of training ground for sympathy, reminding us of the impact we have on each other – and the seriousness with which we should take that impact. Art, at its best, makes the world bigger. And after it has done that, we get to decide what to do with all that extra space.

The stoic male hero

Art targeted at young men is far less interested in interiority. Consider the likes of Deadpool, Top Gun: Maverick, and The Fast and The Furious films. These works of art are not interested in emotional nuance in the same way as The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants is, because they’re not centred around emotionally changeable characters. Neither Deadpool nor Dominic Toretto need overcome internal obstacles – only external ones.

Art for young men tends to promote stoicism or, at the very least, inflexible leading men. Leads of young adult films directed at men are primarily unflappable – above all else, they value calm, and decisiveness. They are what Jon Brooks describes as “stoic superheroes”.

That’s not to say such art needs to be entirely dismissed – it has other uses. But the hole in male education around emotions – what we do with them, how they shape us – has profound knock-on effects.

When your heroes don’t validate you in your emotional complexity – in your essential fallibility – your moral life suffers. There is a loneliness to growing up without seeing a complex inner life on the screen. Films should, in some complicated way, forgive us. They should make it clear that we are not alone.

That loneliness is solidified by a further absence in young male cinema – a hole where there should be depictions of non-judgmental, accepting friendships. The “buddy comedy” genre does aim to rectify this gap, but such films are few and far between. The Sisterhood Of The Traveling Pants models genuine connection between its heroes, who are willing to be their true selves around each other. There is no real corollary for men.

There’s a sequence part way through The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants where Tibby, the teenage shelf-stacker, steps out into the quiet of the afternoon, surrounded by her middle-aged co-workers as they smoke in the sun. She says nothing; they say nothing.

Later, this will become the setting where Tibby learns not just about loss, but also about the hard-won work required to give life meaning. For the moment though, all that happens is that Tibby stands there, the sky orange around her, and takes pause. It’s a moment of true emotional vulnerability – a brief flash of Tibby sitting in her feelings.

And that vulnerability is important. Without that vulnerability, genuine emotional connection is impossible. Which is why the dearth of such moments in art aimed at young men has such worrying implications. Many men struggle with their own vulnerability; struggle to feel authentic, and true. From that comes loneliness. From that comes pain.

There is a hole in male education, and it’s shaped exactly like this film. And, more specifically, a hole shaped like the image of a young woman, standing in the sunshine, staring straight ahead, and then slowly walking offscreen.

Image: Warner Bros. Pictures

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Other

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Kate Manne

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ask an ethicist: Is it OK to steal during a cost of living crisis?

Ask an ethicist: Is it OK to steal during a cost of living crisis?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 SEP 2024

The cost of groceries is spiralling out of control. Meanwhile, the major supermarkets are making a killing. I can barely afford the fuel to get to work, let alone fresh food for dinner. Surely, it’s OK for me to pilfer the odd packet of beef patties or punnet of strawberries?

It sometimes feels like the grand bargain of society is breaking down. We’re told that if we work hard, get a good education and don’t cause trouble then things will all work out – we’ll get a good job, be able to buy a home and we can still afford the odd luxury. But many of us are discovering that even when we play by the rules, we still feel like we’re falling behind.

And then we see the price of asparagus has gone up again. It’s not like asparagus farmers are getting rich. Neither are we. But the supermarket duopoly is. The outrage at this apparent injustice is understandable. And some of that outrage is tipping over into shoplifting, with the big supermarkets registering a surge in theft.

But – brace yourself – as an ethicist, I’m going to remind you that stealing is wrong. Well, it’s almost always wrong, especially if you’re only stealing out of a sense of outrage.

The thing about outrage is that it demands satisfaction. It motivates us to punish a perceived wrongdoer. But whom do we punish when the wrongdoing isn’t perpetrated by an individual but by an unjust system? It might feel justified to place a finger on the scale to tip things back in our favour by nabbing a few essentials (and the odd packet of TimTams). But in doing so, we risk letting one injustice lead to another without actually tackling the problem in the first place. We might feel like we deserve fairer prices – and I think we do – but stealing isn’t the way to make that happen.

But surely pilfering a couple of peaches and a jar of pickles is a victimless crime. The big supermarkets are making a motza, and they factor theft into their bottom line. That’s a trifling loss for them, and a nice peach and pickle cocktail for me.

Here’s a pickle for you. While a single instance of shoplifting might not have a big impact, every instance adds up. Because supermarkets do factor in theft to their prices, the more stuff that goes missing, the more they jack up prices – not to mention investing more in anti-theft technology. So, you’re in part contributing to the very problem that is motivating your theft. And those higher prices impact everyone, including those who might be struggling even more than you are.

At the heart of ethics is the idea that we should take responsibility for our actions. Do you want to be responsible for making the cost of living crisis worse?

Then there’s the matter of principle. Every time you feel justified stealing, you’re allowing others to use that same justification to steal. You’re effectively endorsing stealing in general.

One missing pickle jar might not make much of an impact on prices, but if everyone swipes something, then pickles can pretty quickly become out of reach.

OK, OK. I’ll redirect my outrage to writing sternly worded letters to the newspaper about grocery prices. But what if I’m starving because I can’t afford even a packet of Kraft singles to get through the day? Is stealing justified then?

As I said earlier, stealing is almost always wrong. But not always. Mortal peril is one case where most ethicists would say that it’s permissible to steal. Say your child is dying of a preventable disease and needs medication immediately, but your local supplier jacks up the price to an unaffordable level at the last moment and refuses to make an exception. If there’s no other ethical way to save your child’s life, then stealing could be forgiven.

However, that doesn’t mean raiding the lolly aisle. Note the “no other ethical way” bit. Generally, we’re obliged to do everything we can to work within the bounds of ethics and the law before we step outside of them. So, if you’re struggling to afford food, and there’s a food bank nearby that is willing to help you out, then that’s where you ought to turn before stuffing celery down your jumper.

Similarly, if there were some perverse law that prevented you from legitimately buying necessities, then you could pull a Martin Luther King Jr and ignore that law. As he said:

“One has not only a legal, but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.”

In short: stealing is bad, unless stealing will prevent something worse from happening. If not, then leave that punnet of strawberries alone and save your stamina for fighting the unjust system in other ways.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What it means to love your country

Explainer

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Aesthetics

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Philippa Foot

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture