Let’s cure the cause of society’s ills, and not just treat the symptoms

Let’s cure the cause of society’s ills, and not just treat the symptoms

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff 25 JUN 2024

The lead up to June 30th, is critically important for organisations, like The Ethics Centre, that depend on tax-deductible donations in order to make ends meet. Every organisation has a compelling claim to make for why their cause is deserving of support.

Some have ‘natural constituencies’ defined by the specific nature of the issue to be addressed. For example, medical research institutes will focus on those touched by the various diseases they work to treat and to cure. Other charities have a clear focus on solving one clearly defined problem, like homelessness, and can point to the specific impact that every dollar of charitable giving can have.

And then there are organisations like The Ethics Centre – where the work ranges across the whole span of human affairs with an impact that may take decades, if ever, to register. Consider this … How do you capture the significance of the countless bad things that did not happen as a direct result of good ethics leading to good decision making?

Yet, ours is a story that needs to be told – again and again. It’s not just a matter of ‘rattling the tin’ in the hope of securing a few more donations. Please believe me when I say we need them – as never before. However, there is also real and growing sense in which the need for ‘ethics’ is growing greater with each passing day.

Poverty, inequality and disadvantage are not ‘natural’ aspects of the human condition. Nor is it inevitable that the earth should be ravaged by our species. Rather, the root cause of social and environmental degradation lies in the character and quality of human choice – the most powerful force on this planet. Knowing this to be so, philosophers have spent millennia working to understand the underlying structure of human choice and how it might be harnessed for good rather than ill. Ethics is the branch of practical philosophy that addresses this question.

Australia stands on the cusp of a brilliant future. It has everything any society could need: vast natural resources, abundant clean energy and an unrivalled repository of wisdom held in trust by the world’s oldest continuous culture supplemented by a richly diverse people drawn from every corner of the planet.

As such, Australia could become the most prosperous and just society the world has ever known. However, whether or not this future can be grasped depends not on our natural resources, our financial capital or our technical nous. The ultimate determinant lies in the public’s willingness to trust those who will lead the process of translating the vision into reality.

Thus, we see the effects of ethical failure not only in its most obvious symptoms. Its corrosive effects can also be seen in the loss of public trust in nearly all of our major public and private institutions. This loss of trust has come at precisely the time when it is most needed – when we should be able to rely on those institutions to help guide society as it navigates a landscape of increasing complexity.

Australia lacks a peak organisation with a mandate to address the major ethical questions of our age. Significant legal questions can be referred to the Australian Law Reform Commission. The Productivity Commission performs a similar function in relation to questions of economic significance. No such body exists to consider ethical questions – such as are encountered on a daily basis. For example: should we deploy lethal autonomous weapons systems? What are the implications of embracing modern manufacturing techniques that will make many existing jobs redundant? Should we be moving to tax consumption and/or the means of production rather than labour so as to preserve the capacity to offer a social ‘safety net’? Is access to a ‘home’ (as opposed to ‘shelter’) a basic human right? And so on …

The Ethics Centre has spent 35 years building the foundations upon which to build a world-first, national Ethics Institute. But, as of today, that still remains a dream. Meanwhile, we have the work of the moment. It includes offering our Ethi-call service, the world’s only free national helpline for people with ethical issues. Its greatest impact is when it helps to prevent the kind of ‘moral injury’ that does so much harm to mental health. And then there are events like the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) one of the few places left where reasonable people can gather together and engage in the civilising art of ‘principled disagreement’. These are just some of the things we do in order to help bring ethics to the centre of everyday life.

I come back to one central point. If you’d like to address causes over symptoms then please consider supporting ethics. It’s simple: better ethics make for a better world. Even a few dollars can help that to be as true in reality as it is in principle.

With your support, The Ethics Centre can continue to be the leading, independent advocate for bringing ethics to the centre of everyday life in Australia. Click here to make a tax deductible donation today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Recovery should be about removing vulnerability, not improving GDP

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

It’s time to talk about life and debt

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Banks now have an incentive to change

Reports

Business + Leadership

Ethics in the Boardroom

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Critical thinking in the digital age

It’s a usual Friday night; you’re at a friend’s place. A hush falls over the group as one of the boys pipes up: “Yeah nah but Andrew Tate has some good ideas too”.

Hopefully, you’ve never found yourself in this position, but you might know someone who has. Figures like Andrew Tate, known for his proud advocacy of misogyny among young men, aren’t uncommon on social media and their followings are microcosms of a much larger issue: a deficit of critical thinking in online education and spaces.

Unfortunately, social media platforms aren’t adequately removing hate speech or radicalising figures, nor can we expect filters and rules to ever be enough. With this in mind, we need ways of educating (often young) viewers on how to decide what and who to trust.

I recently attended a live recording of the Principle of Charity podcast at Sydney Writers’ Festival where this idea was raised with comparisons between non-fiction books and videos. Philosopher A.C. Grayling and art historian and content creator Mary McGillivray spoke at length about the various limitations of each medium. While both were reluctant to take polarising positions, eventually a sticking point did arise.

Grayling argued that the relative accessibility and ease of creating social media content makes it more dangerous, given its ability to platform those with little-to-no credibility or expertise. This echoes an interesting evolutionary theory called “costly signalling”, which says the more someone invests in sending a message – i.e. the more “costly” it is for them – the more likely it is to be trustworthy. On the other hand, the less someone invests in sending a message – the “cheaper” it is – the more likely it is to be untrustworthy or noisy. This is one reason why handwritten letters tend to be more thoughtful than fleeting social media posts. McGillivray’s response was two-fold.

Firstly, she noted that there are plenty of questionable published books out there by charlatans and the like – books that prey on insecurities to make sales, or simply peddle well-disguised misinformation. So, this isn’t a problem unique to social media.

Secondly, to which Grayling conceded, traditional avenues of information dissemination are often gatekept behind propriety, things like formal educational status or money. This is the flip side to costly signalling when applied to humans: only those who can “afford” to make costly communications will be heard and believed, so the wealthy and powerful will often dominate public discourse.

There are significant benefits, then, to having a medium that’s accessible to those who have never been afforded the circumstances to engage in these systems. There is still a trade-off: low-cost communication means potential for an oversaturation of inaccurate or useless information, but that is something we must contend with if we want to avoid restricting these things to the already-rich-and-powerful.

McGillivray herself is in the middle of a PhD, not yet an expert in the eyes of academia, yet she has amassed a huge following for her historical art analysis and edutainment (educational entertainment). Using her MPhil in History of Art and Architecture, she is able to produce well-researched and engaging videos that educate an audience that might not otherwise have been introduced to the topic at all.

Unfortunately, it’s especially easy for poor video information to also garner audiences because of its reliance on charisma above all else. We can be easily swayed by charisma as we passively consume it, because passive consumption leaves us more open to suggestion.

We can be prone to dismissing legitimate information and being overly charitable towards frauds based almost entirely on aesthetics.

Whom should we listen to?

Who qualifies as an expert, and when is being an expert relevant?

To figure this out, we have to talk about the combination of trust and critical thinking. Regardless of whether we’re picking up a book or scrolling on our phones, we need to know whether we can trust what we’re consuming and who we’re consuming it from, else we become yet another cog in machines of misinformation.

Unfortunately, there are many forces in the world that try to deceive us every day, from advertisers to influencers to corporations to politicians. To gain a good sense for what to trust, we need to know what to distrust by developing our critical thinking skills. This process isn’t simple, yet anyone can do it.

The first step is acknowledging that we are sometimes gullible and generally easy to convince with rhetoric. Speaking quickly, using jargon, seeming confident, having a high production quality are all things we intuitively associate with intelligence or expertise and yet they can often act as a distraction from the incoherence of the information being presented to us. This isn’t our fault – they’re designed and used specifically to lower our intellectual guards – but it is something we can learn to recognise and counter.

On top of this, even when we are capable of being critical of what we consume, we’re often bombarded with so much information that it makes it almost impossible anyway. In these situations, we rely on heuristics and biases to varying degrees of success. These mental shortcuts let us make faster decisions, but that speed often comes at a cost of accuracy.

Being discerning of sources

One clear thing to look for is the source of the information.

Check if the information comes from a generally trusted source, like a government website, a university, a peer-reviewed study or a reputable news outlet. While it’s dangerous to be overly sceptical, it is important to note that critical thinking should also extend to sources you trust. Just like anything else, governments, universities or other sources can be biased in certain ways, and being aware of those biases can help you understand the motivations behind different ways of presenting otherwise accurate information.

For example, news with a repeated focus on or omittance of a certain group of people can imply to viewers a false sense of significance. Without context, even accurate information can be used to misrepresent a wider picture.

There are many organisations dedicated to fact-checking and bias-checking news and politics, so using them alongside your broader consumption of information can give you a more comprehensive perspective on different issues. For fact-checking of global news trends, there is the International Fact Checking Network, or in Australia there is the Australian Associated Press Fact Check. These resources can help us identify common misinformation trends.

However, there are other ways to train ourselves to be aware of our own biases when we consume media and especially news. For example, Ground News is an organisation that collates news stories from thousands of sources and demonstrates how the same stories are presented differently depending on the general political slant of the publication. This is an effective way of learning about how even subtle differences in language can have a drastic impact on our interpretation of news. Using resources like this is a good way to develop media literacy by training yourself to recognise patterns in media coverage.

Critical reflection

Many people aren’t going to get their information straight from the source, though. Let’s say you have found an author or a creator that you like. Maybe your friend even told you about it. How do you know if you should trust them?

Again, the first thing to check is where they’re getting their information from. If they’re presenting evidence, then check that that evidence is coming from a place that you know to be trustworthy. This isn’t a check that you need to do all the time but putting this effort in at least at the beginning will give you a foundation for trusting this person in the future.

If they aren’t presenting empirical evidence, you can check their credentials and history. Do they have reputable qualifications in a relevant field? Do they have a relevant lived experience to speak from? Do they have a history of presenting accurate information? Is what they’re saying consistent with their own points and with what you know from trusted sources?

While not all necessary, these are all different ways of making sure that you critically reflect on the news and media you consume.

Other useful ways to engage critically with media are to challenge yourself to identify different aspects of it. The intended audience can tell you a lot about a publication, like what their motivations or affiliations might be. You can identify this by looking at the language used and asking yourself how it reflects who it is trying to speak to. You can also find potential bias by imagining how the information might sound different if it was written with another kind of audience in mind.

Another method of testing your understanding of a piece of news is to try to identify what the intended message is by summarising it in 1-2 sentences. Doing this is a good way to practice understanding the implications of lots of bits of information as a whole. It will also help you to ascertain underlying assumptions that are made without the viewer’s comprehension. Identifying these assumptions will help prevent you from being misled.

For example, there is a general implicit assumption that if something is in the news, then it is important. But you might not agree with that. Sometimes things are reported on or spoken about to cause them to seem important, so by questioning that foundational assumption we can begin to critique the content and motivations behind certain information.

Identifying these can help you determine how to process the information being presented to you and whether you need to scrutinise it further. Developing critical thinking skills to increase your media literacy is an important part of ethical consumption because it helps us navigate systems of power and slowly prevents the spread of harmful information and ideas.

The Principle of Charity is a podcast that injects curiosity and generosity back into difficult conversations, bringing together two expert guests with opposing views on big social issues.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

Self-presentation with the collapse of the back and front stage

Self-presentation with the collapse of the back and front stage

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Beth Anderson John Neil 12 JUN 2024

The digital revolution has ushered us into a theatre where the stage extends into our living rooms, and the audience is always watching. Nowhere has this been more evident than in the context of work.

In the pandemic-driven shift from office to home (and back again), the curtains between personal and professional lives have not just been pulled back but torn down. This has changed not only where we work, but how we work, and crucially, how we are seen by our colleagues. It also has radical implications for what it means to be ‘authentic’ in the workplace.

Where the pre-2020 professional may have meticulously managed their work persona, the pandemic era has introduced authenticity by default, for better or worse. This collision of worlds invites us to question: In the blur between ‘onstage’ and ‘offstage’, which parts of ourselves do we bring to the virtual office table?

Presenting our authentic selves

David Hume, a prominent Scottish philosopher of the 18th century, radically destabilised our notions of a consistent, singular self. In A Treatise of Human Nature, Hume argued that our perceptions are the only real things about us and that these perceptions are constantly changing.

He famously stated, “When I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe anything but the perception.”

In essence, Hume’s view of the self as a ‘bundle’ of perceptions challenges the idea of a singular, unchanging and enduring entity. Instead, our sense of self is more like a series of fluid, dynamic experiences that are related but distinct, with no unifying core or essence. This perspective has had a significant influence on later philosophical thought, particularly in discussions about personal identity and the nature of the self.

Given that for Hume, the self is a collection of changing perceptions, it might follow that our self-presentation is inherently fluid and adaptable. This adaptability might imply a level of control, as different situations or contexts bring different perceptions to the forefront, thus altering our self-presentation.

Rather than managing a stable, singular identity, self-presentation for Hume may be more about managing perceptions, both internal (how we perceive ourselves) and external (how others perceive us).

Hume also acknowledges the influence of external factors like social context and relationships on our perceptions. This indicates that while individuals might have some control over their self-presentation, it is also shaped by external circumstances beyond their complete control.

Self-presentation on the new office ‘stage’

In 1959, the influential sociologist Erving Goffman explained self-presentation as how we try to control how others see us. Drawing on theatrical metaphor, Goffman, noted the different roles we play in front of different audiences. He also highlighted the importance of ‘backstage’ spaces – private areas in which we are free to drop any act without spoiling the performance.

Current workplace paradigms, however, often involve catching glimpses of life behind the scenes. We increasingly perform our work roles immersed in the geography of our non-work selves while trying to create some separation between the two. Self-presentation in these new liminal spaces is therefore less straightforward than it might first appear and, again, poses questions about authenticity.

Pre-2020, jokes about pairing waist-up office wear with below-desk pyjamas were largely targeted at newsreaders. However, the pandemic-driven move from office to home sent many of us hurtling into colleagues’ worlds like never before.

The abrupt pivot to online meetings flung open virtual doors into our colleagues’ sanctuaries – spaces that were once off-limits to our professional personas. The sanctity and intimacy of the home, traditionally a retreat from the public gaze, became a shared space, albeit digitally, and often reluctantly.

The unexpected cameo of a pet, the soft murmur of children playing in the background, or the occasional appearance of a spouse served as reminders of the complex lives beyond the professional facades we maintain. These moments, while humanising, also signalled a tectonic shift in our understanding of authenticity.

As we continue to navigate this uncharted territory, it’s clear that our pre-pandemic understanding of privacy needs re-evaluating. The distinctions between work and private life must be redefined to protect the sanctity of both.

Employers and employees alike must collaboratively develop new norms and etiquettes that respect personal boundaries while accommodating the realities of our interconnected digital lives.

Examining authenticity

Identity curation is a core part of self-presentation, and we do it constantly. It is this curation that radically undermines claims of self-authenticity. In many workplaces, the move online merely highlighted ambiguities or inconsistencies in thinking about authenticity that were always there.

The language of authenticity is pervasive in the workplace; it features in mission statements, company values and even competency frameworks yet is rarely defined by organisations in any meaningful way.

The idea of an authentic self underpins the relatively recent introduction of the notion of ‘bringing your whole self to work.’ We have witnessed a radical shift from earlier 20th-century conceptions of workplace conformity and strict adherence to a professional persona that often required suppressing personal identities and emotions, to a workplace culture that rhetorically valorises the uniqueness of individual’s ‘lived experience’ and the expression of people’s unique perspectives and backgrounds in the workplace.

However, it still begs the question as to what precisely constitutes an individual’s authentic self? And which modes of authenticity are valued over others?

Expecting employees to somehow just be authentic – a complex and debated concept in an era of multiple states of self-presentation – is therefore an unreasonable ask, whether offline, online or moving between the two.

Recent discussions on authenticity in the workplace highlight a complex landscape where the concept is both lauded for its potential to enhance individual well-being and critiqued for its unintended consequences. Hamilton and Almeida at the LSE Business Review point out that an authentic work environment can be beneficial to psychological health and performance outcomes, yet the narrow social norms of professionalism often limit who can genuinely express themselves without repercussions, leading to assimilation and code-switching.

Furthermore, Hamilton and Almeida also found that authenticity can become a source of cognitive strain and alienation when individuals feel compelled to align with dominant group norms, which may conflict with their innate values and personal identities. This is particularly challenging for minority groups within organisations, as the pressure to conform can lead to psychological distress and inhibit genuine self-expression.

Critiques also focus on the potential for a culture of authenticity to inadvertently perpetuate social inequalities, as those who cannot or choose not to conform to the dominant narrative of authenticity might self-segregate or face negative work-related consequences. Additionally, the pursuit of authenticity can stifle dissent and innovation, as uniformity of thought undermines the benefits of a diverse workforce.

The call for authentic self-expression in the workplace must be balanced with a conscious effort to foster an inclusive environment where diverse voices are not just heard but valued. This requires leadership that understands and actively manages the dynamics of group identity, as well as a collective effort among employees to embrace and respect differences.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ready or not – the future is coming

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Holly Kramer on diversity in hiring

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Is technology destroying your workplace culture?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

What are millennials looking for at work?

BY Beth Anderson

Beth has spent over 15 years in leadership and ethical consultancy roles across the UK non-profit and public sectors. Much of her career has involved identifying ‘what works’ in a way that synthesises knowledge from research, policy and practice.

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

In defence of platonic romance

When I was young and like many little girls, I was bewitched by all things magical and had a keen sense of romantic sensitivity.

I would regularly claim to spot mermaids in the froth of breaking waves and would meticulously construct fairy circles in my grandmother’s garden. These tendencies would lead me to weave fanciful and elaborate dreams about my future, mainly about love. In all the rituals, potions and stories I concocted as a young girl, there’s one that sticks out in my mind.

One particular holiday in the Blue Mountains, my cousin and I were around twelve – the age when many children start to fully understand what awaits them in teenagerhood – namely, romance. One night, under a full moon, I proposed a plan – we would cast a spell to summon our future partners and design our prince charmings. Petals were gathered from the flowering bushes that surrounded our accommodation and a large plastic salad bowl was stolen from the kitchenette and filled with water. With great reverence and solemnity, we sat on the deck and threw petals into the bowl. As each one hit the surface, we would say aloud a quality that we wanted in a future partner.

“Tall!”

“Nice!”

“Dark hair!”

When the ritual was over and the bushes were bare of their flowers, we threw the contents of the bowl out onto the lawn quite matter-of-factly. Completed with confidence, we did not doubt that what had transpired between us that night had set us up very nicely for when we were grown women. Now, as a young woman with aspirations for a career as a writer and a bachelor’s degree under my belt, I look back and question, with the opportunity of a full moon and a ritual, why did I only wish for a romantic relationship with a man?

In my developing mind, I had an understanding that women found their identity in being the object of romantic love. To be loved by a man was equated to being accomplished – one day when I was clever enough and pretty enough, I would be chosen. However, there’s little personal autonomy as an object.

Many pioneers of third-wave feminism have fought against the objectification of women and for their greater value in society. Much of their activism has focused on the role of women in social and political spaces. At twenty-two years old I’m still learning how to navigate my position in the world as a young woman. My sense of accomplishment with my career and my education has not always been constant. Upon reflection, there’s a source of value and abundance in my life that is disconnected from any metric measure of success – my friendships. Throughout the dawn of my adult years, my most impactful, and intimate relationships have been with my close female friends. If our platonic relationships were treated as reverently as our romantic ones, what would be possible?

Philosopher Simone de Beauvoir described the desire to love and be loved as part of the structure of human existence. Her 1949 work The Second Sex explores women as the ‘other’ in society and how men and women often develop asymmetrical expectations of love. De Beauvoir discusses heterosexual love as being either ‘authentic’ or ‘inauthentic’. Within her framework, to achieve authentic love, both lovers need to maintain their individuality. But in the context of heterosexual monogamy and the biological family unit, is this even possible for women?

Many women are often first and foremost identified as wives and mothers, essentially, they have relational autonomy. Relational autonomy proposes that as the ‘Self’ is related to those around us in various ways, the way we identify ourselves cannot be a practice that is achieved alone. While an explanation such as this may relate positively to ideas of community and comradery, many women experience a loss of self as wives and mothers.

Many women in heterosexual relationships must, to some degree, be experiencing inauthentic love – described by De Beauvoir as being based on inequality between the sexes:

“[Men] never abandon themselves completely […] they remain sovereign subjects; the woman they love is merely one value among others; they want to integrate her into their existence, not submerge their entire existence in her. By contrast, love for the woman is a total abdication for the benefit of a master.”

If our support systems and our identity are entangled with relationships that have an inherent power imbalance, is there space for authentic love? While De Beauvoir’s outlook may appear characteristically existential, there is a faint yet unmistakable silver lining. If heterosexual relationships leave women devoid of true identity and autonomy, what is left? Our female friendships.

Within my female friendships, I’ve rediscovered something from my childhood that’s been lacking in my romantic relationships with men – magic. There’s something about friendships between women that makes pagan behaviour seem reasonable. I can understand why medieval witches were often accused of dancing naked around bonfires; I would do that too for my best friends.

To be clear, I’m not saying that people don’t need romance or romantic relationships, nor am I saying that all heterosexual relationships cause harm to the women in them. Romantic relationships can be a source of unique joy and adventure. Where they become problematic is when they are the centre of our personal universes. As for romance, there’s space and, arguably, a necessity for it in our platonic relationships too. I implore you to buy a bouquet of flowers for your dearest female friend and see what good it does.

With platonic relationships at the centre of our worlds, there’s a web of support and intimacy without the power imbalance inherent in some heterosexual relationships.

By decentralising the role of romantic love in our lives and valuing other relationships just as equally, there’s an opportunity for community building, deep understanding, and cultivation of our own personal identity.

If, at twelve years old, under that Blue Mountains moon, I had wished for an ideal best friend – when, as an adult, my romantic relationships fell short of the mark again and again, it wouldn’t have felt like I had as far to fall. Rather than the sun dropping out of my personal solar system, I’d lose a moon or two. Still a knock to the system, just not an earth-shattering one. Perhaps, feminism and gender equality can be aided and progressed by revolutionary love for our friends.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

BY Layla Zak-Volpato

Layla is a 22-year-old writer and poet living and working in and around Eora/Sydney. With an educational background in ecology and wildlife conservation, her work focuses heavily on the ethical and moral dilemmas of the anthropocene. Through a creative lens, Layla examines the intersections between gender, identity, philosophy and environmental issues. She aspires to use these themes as the backbone for a career as a scientific communicator who utilises both creative and informative literary forms.

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 22 MAY 2024

New and challenging ideas are endangered species these days. They are surrounded by predators from all sides.

There are the entrenched interests that want to maintain the status quo. There are trolls who will beat them down just for laughs. Then there is the threat of cancellation by those who deem challenging ideas unworthy of being expressed at all.

Yet, as their natural habitat is being invaded, we as a society need these ideas to thrive more than ever before. We must continually challenge our assumptions, for history has shown us how often they end up being false. We must be wary of the status quo, and the powers that work to preserve it for their own benefit (and our detriment). We need to have open and honest conversations, lest our minds – and our ideas – become outdated and stale in a fast-moving world.

What we need is a sanctuary where new and challenging ideas can be nurtured and kept safe from the predators until they’re strong enough to be released into the wilderness and thrive. We need a space where they can be heard with open ears and challenged by open minds. A space where discourse is steered by good faith and reason rather than tribalism and fury.

FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey, says that is what The Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI, to its fans) is all about this year. “In a litany of entrenched ideas, 24-hour news cycles, shallow information and self-censorship, we desperately need a space where we can engage with challenging ideas in good faith.”

FODI is a “sanctuary”, not just as a refuge to keep us safe from the noise, the trolls and the bad faith speakers found in the wilderness of public discourse, but a space where we’re safe to engage with powerful and provocative ideas.

A lot is said about “safe spaces” these days. But they’re typically talking about only one type: “safe from…” spaces, where people can be protected from things that might be harmful, triggering, discriminatory or distressing. These spaces are important in a world filled with dangers, because we should always respect the inherent dignity and vulnerability of others, and seek to protect them from harm.

But if we only have “safe from…” spaces, we risk shutting down difficult conversations that we might have to have. We might stifle precisely the kinds of discourse that could make “safe from…” spaces less necessary. We can end up being coddled rather than becoming resilient or testing our own ideas.

FODI exemplifies another kind of safe space: “safe to…”. This is a space where people are able to express themselves authentically and in good faith without fear of reprisal, where they can engage with difficult and controversial topics that might even be deemed offensive in other contexts. These are the conversations we have to have if we’re to combat the problems that make “safe from…” spaces necessary.

“FODI is gives us an opportunity to hear powerful and provocative speakers from around the world talk on important and rousing topics,” says Harvey. It’s also a sanctuary. One where “audiences can engage with these ideas in a way that we, unfortunately, can’t in the wild. In our sanctuary you are safe from hype and safe to listen and to ask questions.”

Such a sanctuary needs to be carefully curated to enable open good faith engagement with dangerous ideas. That’s why this year’s FODI will be special. When you come to FODI, you will enter a sacred space, with a shared understanding of our mutual purpose and a will to create a better world. A space to let curiosity guide you, where good faith reigns, where you’re free from intimidation and shame for what you choose to believe and express, a safe place to think deeply about the world.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas returns 24-25 August 2024 to Carriageworks, Sydney. Subscribe for program updates at festivalofdangerousideas.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Explainer

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Aesthetics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

How The Festival of Dangerous Ideas helps us have difficult conversations

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Strange bodies and the other: The horror of difference

Strange bodies and the other: The horror of difference

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 21 MAY 2024

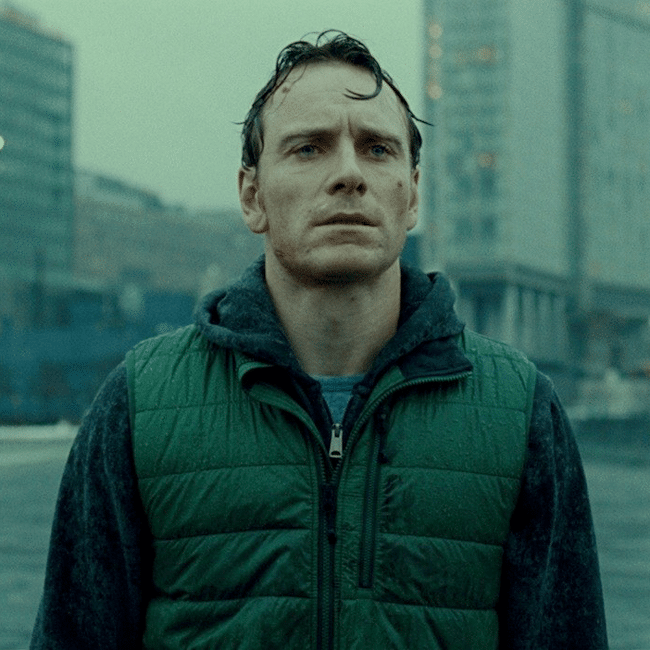

Love Lies Bleeding, the new film by director Rose Glass, is a simple girl-meets-girl noir story. At least, for about half of its running time.

Set in a nowhere town populated by gun nuts and ne’er-do-wells, it opens with a chance encounter between Lou (Kristen Stewart) and Jackie (Katy O’Brian). The former’s trapped in this dump because she needs to protect her sister, and the latter has sailed in to try and pursue her dreams of becoming a bodybuilding superstar. They shoot each other up with steroids, make food for each other, and fall in love.

They are, from the outset, different. They don’t fit into this place, with its villains and deadbeats. Not just because they are queer – but because they want for more, and desire something bigger than the diners and gun ranges on offer.

Which is the impetus for Love Lies Bleeding’s sudden, mid-film shift. The more Lou and Jackie fall out of step with the town, the more they begin to literally change. Jackie, always strong, starts to become superhumanly so. Her body expands outrageously, until, before the audience has really noticed what is going on, she is a giant, dwarfing the town and its denizens.

In this way, Love Lives Bleeding owes more to the cinematic genre of body horror than it does to the noir trappings it initially flirts with. And more than that, it investigates one of body horror’s key themes – the way that difference can manifest not just in our minds, but on our skin.

The mind and the body, the body and the mind

Body horror as a genre is a continuation of the work of philosopher Baruch Spinoza. For Spinoza, the body and the mind are the same thing – the one substance. They are “numerically identical”, as in, there is no separation whatsoever between them. When you point to the mind, you are also pointing to the body. Indeed, Spinoza was a monist – as in, he believed that all things were made from one singular “entity.” Spinoza called this entity nature; some have called it God.

Importantly, this monism means that for Spinoza, our emotions, thoughts, and desires are inherently embodied. On Spinoza’s view, we are not just a brain, controlling a fleshy automaton of a body. We are in our own skin. Or, more precisely, we are our own skin. Anything that we think or want expresses itself physically, because our brain is inherently physical.

This view tells us interesting things about both body horror cinema, and about otherness. Namely, that if we are ‘other’ – if we step outside the mainstream of sexuality, gender, or ability – then that otherness will manifest ourselves in our body. There is no hiding our difference on this view; no successful way to “pass”, as though we are part of the established norm. Anything that we think and feel will make us physically different, and therefore will be able to be read by others. We will always be a square peg in a round hole, and everybody will always know it.

Love Lies Bleeding takes the most extreme version of this perspective – Jackie’s gigantism is a physical manifestation of her difference that means she can’t fit through doorways, let alone pass as one of the town’s regular citizens. She is other, which means she doesn’t just occupy mental states that run against the mainstream. Her difference changes how she carries herself in the world – and how she is perceived.

The othered body and its power

Body horror films do more than merely diagnose the physical manifestations of otherness, however. They also pass a sort of moral judgment on it. Many entries into the genre don’t see this otherness as something to be avoided, or stripped away. Indeed, they see it as something to be embraced – a source of considerable power.

Take, for instance, Carrie, directed by Brian DePalma, in which a young alienated woman discovers that she has telekinetic powers. Carrie is the subject of relentless bullying – in the opening scene, we see her body shamed for its difference, as she has a period in the communal shower, much to the cruel glee of her schoolmates.

But when she discovers that which makes her different is the same thing which makes her special, she becomes significantly stronger. The film’s bloodbath of an ending, in which Carrie decimates those who have humiliated her, is a strange sort of coronation – Carrie is literally wearing a crown while she murders a roomful of her enemies. She’s stopped trying to fit in. Instead, she has thoroughly, wholeheartedly embraced her otherness.

This is point of view is also backed up in the literature about Spinoza. As many Spinoza scholars have noted, understanding is the key to Spinoza’s project – he believed in the ethical value of the accumulation of knowledge – and because of his monism, this understanding is one centred in the body. “For Spinoza the critical task is to formulate an ethics of knowing, which begins with an understanding that body and mind are two attributes of the same substance,” write Paul Stenner and Steven D. Brown. “Increasing the capacity of the body to both be affected and affect others is the means by which the knowing subject progresses.”

In these body horror films, assimilation with the status quo is impossible – how could Carrie, with her telekinesis, ever be like others? How could Lou, the giant, ever pretend to be different? But more than that, however, assimilation is not even desirable. Instead, these films are a rallying cry to those who do not fit into boxes; to the outcasts. They say, “any changes will be noticeable on your skin, so you cannot hide them.” And they say, “any changes will be noticeable on your skin, so you should not hide them.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture

Read me once, shame on you: 10 books, films and podcasts about shame

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Critical thinking in the digital age

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Tim Dean 14 MAY 2024

Ethical protest is a crucial element of liberal democracy. But protesters and universities must tread a fine line to allow good faith expression while preventing unethical forms of speech.

In parallel to the conflict raging in Gaza, another front has emerged in the form of pro-Palestine protest camps at universities across the United States and Australia.

The protesters have called for a ceasefire in Gaza and for their host universities to sever any connections with defence companies that support Israel’s war effort, including divestment of stock in any companies with ties to Israel. Meanwhile, Jewish lobbies have claimed that the protests are stoking antisemitism and compromising the safety of Jewish students.

In the US, these camps have triggered a significant, and occasionally violent, backlash from authorities. Both Columbia University and the University of California, Los Angeles have called in police and riot squads to break them up, leading to hundreds of arrests. Australian campuses have so far refrained from such a forceful response, but there are increasing calls from some voices, to close them down.

How should universities and other authorities respond to these protests? What kinds of protest are deemed acceptable? Which cross the line and should be shut down?

Ethical protest

Every citizen of a liberal democracy has the right to protest against injustice. But protesters and authorities must tread a fine line between allowing justified forms of expression while preventing forms that incite, dehumanise, vilify or cause undue disruption or damage to private or public property.

But what counts as incitement when slogans are interpreted in different ways by different people? What constitutes vilification, when many in the Jewish community perceive criticism of Israel as being antisemitic? Is it undue disruption if a camp prevents uninvolved students from attending their classes? Can a protest movement prevent fringe elements from coopting it to promote extreme views or violence?

These are difficult questions to answer for both protesters and universities. However, a better understanding of the limits of ethical protest can guide those running the camps to ensure they remain within the bounds of what is justifiable speech, and authorities, so they don’t end up suppressing legitimate forms of expression.

In good faith

A crucial feature of ethical protest is that protesters are acting in good faith, which means they are acting with the intention to call out what they genuinely believe to be an injustice.

This means the protesters need to have just cause, and ensure their expression doesn’t stray outside of this justification. In the case of the pro-Palestine camps, there are arguments that can provide just cause, including statements of concern from the United Nations, governments and other world leaders about the impact that the conflict is having on innocent civilians and the lasting damage to infrastructure that could harm future generations of Palestinians who played no part in Hamas’s terrorist attacks of October 2023.

However, there have been some pro-Palestine protesters who have stepped outside of bounds of this just cause, such as threatening Jewish students or saying Hamas deserves “unconditional support”.

A major challenge for the pro-Palestine camps is to keep emotions, especially outrage, in check. This is because justifiable outrage and heated emotion against injustice can easily tip over into calls for unjustified retribution against the perceived wrongdoers. While protesters may not intend to carry out any hyperbolic threats they express verbally, they can still service to threaten, intimidate and dehumanise. A sense of solidarity with one’s cause can also lead people to refrain from criticising problematic views or actors within their own “tribe” for fear of appearing disloyal.

Universities and other authorities are right to clamp down on any individuals who engage in such bad faith forms of expression. However, if protest leaders clearly demonstrate that they repudiate violence and dehumanising claims, and actively police their own ranks, then the universities ought to draw a distinction between the protest movement as a whole and individuals who overstep the line.

Interpretation

Bad faith expression is complicated by ambiguous slogans, such as “intifada” or “from the river to the sea”. Many people interpret the former as a call for resistance, while others associate it with the Palestinian uprisings starting in the 1980s. And some interpret the latter slogan as a call for peace within the region while others hear it as a call for the elimination of the Israeli state.

It is inevitable that symbols will be interpreted in different ways, and it is impossible to ensure that a symbol will only have one meaning. It’s also impossible to prevent fringe elements from appropriating a symbol and potentially tainting its meaning.

However, protest organisers can be clear about the intended meaning of symbols, promote good faith interpretations and suppress their use when they overstep into representing a clear threat to others. People perceiving the symbol should also exercise charity in their interpretation, rather than assuming the worst possible interpretation. Only in clear cases where the symbol is being used consistently in a bad faith manner should authorities step in to suppress its use.

Language matters

Language that is critical of the Israeli government has also been interpreted by some as being inherently antisemitic, and often such criticism has been laced with antisemitic sentiment. However, it is possible in principle to be critical of the Israeli government and its policies without being antisemitic. Were that not the case, then a significant proportion of the Jewish population of Israel would itself be deemed antisemitic due to its strong opposition to the current government’s policies. It is also possible to condemn terrorism and Hamas’ October 7 2023 attacks against civilians and also condemn the scale of collateral damage in Gaza as a result of the Israeli offensive.

It is important for those critical of the Israeli government to be clear in their use of language to not imply any antisemitic sentiment, just as it is important for those listening to exercise charity in how they interpret such statements.

Disruption

Many protests cause disruption. Indeed, disruption is sometimes a means to draw attention to an issue that might be otherwise overlooked by the public. However, ethical protest requires that the organisers minimise their impact on bystanders, especially those who are not responsible for the injustice being protested.

If the disruption becomes disproportionate, or it tips over into serious property damage, then authorities can be justified in placing restrictions on the protest and prosecuting any individuals who are involved in damaging acts. However, authorities must be very careful in how they do so, as targeting the entire protest can end up suppressing legitimate speech and can also backfire, causing more disruption or damage.

More space for protest, not less

Often the most prudent response to a protest is for universities to give the protesters more space for expression, not less. Despite the demands issued by many protesters, one core goal is often simply to be heard and acknowledged. Even if the other demands, such as divestment, are not met, protesters may still feel satisfied if they are given the space and respect to be seen and heard.

If universities give the protesters a platform to express their good faith arguments – and equal space for others to oppose them in good faith – and they can manage it safely, then it can take a great deal of pressure off the protest movement, which might otherwise lash out in more destructive ways.

It is also crucial that the protests do not turn violent. One trigger for such violence is overly forceful policing, as we have seen in the United States. By increasing the pressure on protesters, especially if that pressure is exerted by police, who are trained to use force when necessary to achieve their objectives, then protesters can lash out or act in self-defence. This can, in turn, motivate an even more forceful crackdown, leading to a spiral that can end in violence or riots. Better to take the pressure off and give the protesters the space to act peacefully and in good faith rather than set their backs against the wall.

It is impossible to guarantee that any protest will unfold entirely without cost or error. But as long as the protesters are acting in good faith, with just cause, and if they police their own members to prevent unethical behaviour, then universities ought to give the protesters the space to do so peacefully and with minimal impact.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Ethics, morality & law

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Politics + Human Rights

How to find moral clarity in Gaza

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Australia’s fiscal debt will cost Gen Z's future

Australia’s fiscal debt will cost Gen Z’s future

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Enoch Strickland 10 MAY 2024

When my HECS debt exceeded $50,000, my jaw dropped, and I wondered how I’d ever pay it off. In contrast, my father enjoyed a free tertiary education when he was my age and entered the workforce unburdened by debt. Is that fair?

The Baby Boomer generation faced huge challenges, like post-war reconstruction, promoting civil rights and living with the prospect of nuclear war. But it had its boons too. This is the generation that benefited from a buoyant labour market, cheap housing and enjoyed free university thanks to the Whitlam Government. Today, a booming housing market is helping to fund a luxurious retirement for many of that generation.

On top of this, middle-aged and older Australians have disproportionately benefited from government spending in recent years – spending that has been funded by taking on debt that younger generations will have to pay off. So not only do younger generations not have the benefits that older Australians have enjoyed, but they have the added burden of government debt.

It’d be like if I was able to avoid paying my HECS debt for my university degree by foisting that debt on my children. I would benefit from the education and its employment opportunities, but my children would bear the cost. Just as that would be unfair, so too are Boomers passing government debt onto younger generations while they get to enjoy the benefits of government spending today.

This is the problem of intergenerational injustice when it comes to government debt. Fiscal spending is, by nature, short-term and aims to solve economic problems quickly. In moderation, it isn’t bad. However, in excess it disproportionately benefits people who are working at the time. Younger and future generations then bear the brunt of debt repayments accumulated by previous governments, while receiving fewer immediate benefits from the public spending financed by that debt. In contrast, older individuals enjoy the immediate advantages of government expenditure without the long-term responsibility of repaying the accumulating fiscal debt.

For example, the large government spending during the COVID-19 pandemic has left Australia with a debt in excess of $800 billion. That is around 38% of Australia’s GDP. This means for the next 20-30 years, when today’s young Australians will be entering the workforce, their taxpayer dollars will not go into benefiting the society they live in, but rather repaying these loans. If the government cannot repay those loans, it must either increase taxes or spend less. It means young people potentially could lose healthcare benefits or have less personal money due to increased taxation or cuts in services.

Philosopher Juliana Uhuru Bidadanure argues that we should be focused on relational equality at a moment in time. Relational equality emphasises the significance of social relationships and interdependence in achieving a more equitable society, highlighting the need to address and transform the structural conditions that perpetuate inequality.

Younger people today should not have to financially suffer today because it is expected that their lives will improve later.

Likewise older people in nursing homes shouldn’t be punished because they had a good life earlier. Everyone, regardless of age, should be entitled to a good life. Debt ultimately undermines this principle of relational equality if the benefits are only short term, as an unfair burden is placed unto future generations.

Jobseeker is another example contributing to this inequality. Members of Generation Z who weren’t working or on Youth Allowance during the pandemic received no government benefits, much of which were funded by debt. So, over the next two decades, it will fall mainly on Generation Z to repay that debt, even though they received the least benefit from it. In fact, someone born today will likely have to pay off a portion of that debt in their first job even though they were not alive to experience the COVID-19 stimulus. Older generations will not live long enough to see through the long-term consequences of debt, but young people today will.

It is important to note that not all debt is bad, such as long-term spending as investments today can greatly benefit future generations. Unlike pandemic-related debt, which disproportionately benefited older people, expenditure on infrastructure contributes to the collective good and is eventually enjoyed by younger people when projects are completed, demonstrating a more equitable form of financial responsibility.

In addressing the pervasive issue of intergenerational injustice fuelled by fiscal government debt, we must advocate for policies that prioritise relational equality now. Balancing the scales requires a nuanced approach, moderating short-term fiscal spending, focusing on the impact of spending in the long-term through investments in projects like infrastructure.

Governments need to ensure that they are careful with how their spending today will impact future generations. Short-term spending promises before an election are an example of short-term thinking from our political establishment. Naturally, voters who benefit from such spending might be inclined to support such policies. But they should be mindful of not only their self-interest but the interests of future generations, including their children and grandchildren.

Meanwhile, Generation Z would benefit from advocating for balanced government budgets, for it is in their interests. Young people should always be cautious whenever they hear the words “fiscal”, “stimulus” and “injection” into an economy. Because, in the future, if those government actions risk a debt blowout, they are the ones that will have to pay for that intervention in the future.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Big thinker

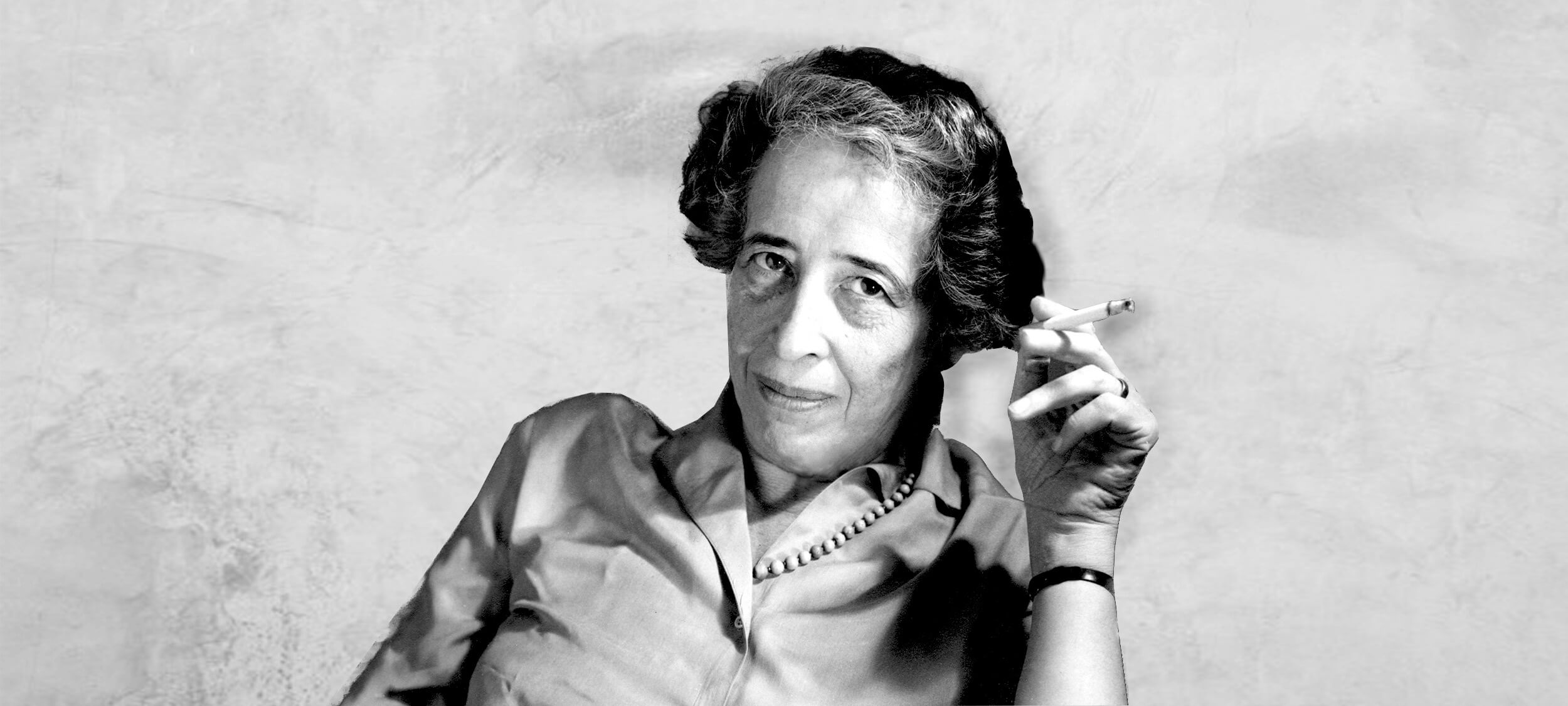

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Self-interest versus public good: The untold damage the PwC scandal has done to the professions

BY Enoch Strickland

Enoch is currently studying a Bachelor of International Security Studies and Politics, Philosophy and Economics at ANU in Canberra, but was born in Alice Springs, NT. He grew up and graduated there and has a strong passion to help those most vulnerable in Australian society. His hometown is currently experiencing a crime wave, (Kmart and Target are rumoured to be closing down – removing cheap clothes options in Central Australia) and a health crisis. He wants to bring further insight from his own experiences to help further understand how we can bring services to remote communities and why governments are responsible for this.

Productivity isn’t working, so why not try being more ethical?

Productivity isn’t working, so why not try being more ethical?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Ross Gittins 6 MAY 2024

Economists and business councils have been telling us for years that we must improve our productivity if we want to be more prosperous but, so far, they’ve had little success. Surely, there’s something else we could try?

As we’ll see, it’s something for Treasurer Jim Chalmers to ponder as he puts the finishing touches to next Tuesday’s budget.

Economists have many strengths, but they don’t win many prizes for thinking outside the box. Productivity is the obvious way to increase our prosperity but, despite all the admonition, for years it’s been hard to achieve, both here and in the other rich economies. It’s clear there’s a lot economists don’t know about how productivity is improved.

So, is there nothing else we could do to improve the way the economy works and the satisfaction it brings us? Of course there is – particularly when you remember this isn’t just about dollars and cents. Don’t you think life would be better if we could do all our earning and spending in an economy that generated less angst?

I’m indebted to Dr Simon Longstaff of the Ethics Centre for reminding me that behaving more ethically would be a good way to get better results from the economy.

Huh? How does that work? Let me tell you.

Ethics is a set of beliefs about the right way for people and organisations to behave, particularly in their relations with other people. Often, the right thing for us to do in particular circumstances is obvious.

It’s obvious, for example, that we should (almost) always obey the law. It’s just that obeying the law isn’t always convenient or inexpensive. And sometimes when our own interests are top of mind, it’s hard to see what’s obvious to everyone else.

In any case, because differing groups of people have differing beliefs and motives and objectives, ethical dilemmas – deciding what’s the right thing to do in all the circumstances – are common, particularly in business. That’s why we have a new profession of ethicists offering advice to organisations, of which Longstaff is the most prominent.

But what’s that got to do with the economy?

Well, let’s be clear. The only reason we should need to do the right thing is that it’s the right thing to do. And the only reward we should expect is being able to sleep well at night in the knowledge that we’re treating people justly, often at some cost to ourselves.

However, as Deloitte Access Economics has demonstrated in a report for the Ethics Centre, there is a strong “business case” for behaving ethically. A case that makes sense not just for individuals and businesses, but also for the treasurers and Treasuries responsible for improving the way the economy’s working.

The case rests on an obvious, but often forgotten truth: market economies rely on a high degree of trust.

Trust between buyers and sellers. Trust that you’re not selling me a dud. Trust that your cheque won’t bounce.

Trust that you’ll let me return it if there’s a problem. Trust that you’ll honour your promise to service the thing for the next X years. Trust that you won’t pinch someone else’s bag from the airport carousel. Trust that you’ll repay the money I lent you.

Trust that if I let you check yourself out at my supermarket, you won’t slip in a few things you didn’t ring up. Trust that if I work for you, you’ll treat me fairly. Trust that the law will back me up if you do the wrong thing.

Point is, the more confident we are that we can trust each other – trust the businesses we deal with – the more smoothly and cheaply the economy runs and the more business gets done. When we have to spend a lot of money on security and making sure we’re not ripped off, the costs mount up, and we end up not doing all the transactions we could.

So, how do we get more trust into the economy? How do workers, employers and businesses get themselves a good reputation? By always behaving ethically. (I could say this also applies to politicians, but that would be pushing it.)

Research by Access Economics finds evidence that fewer unethical decisions lead to better mental and physical health for individuals. And evidence that unethical behaviour leads to poorer financial outcomes for business. And evidence that ethical behaviour results in higher wages.

But Access also reminds us of the evidence that our ethical standards could be a lot higher than they are. The World Values Survey finds that only a bit over half of Australians think most people can be trusted. The Governance Institute finds that, on a scale running from minus 100 to plus 100, Australia ranks at plus 45, or “somewhat ethical”.

Then there’s the string of royal commissions finding unethical or even illegal behaviour in institutional responses to child abuse, misconduct in the banking industry, and aged care. And that’s before we get to the epidemic of “wage theft” that so many otherwise respectable big businesses have had to admit to – all of it purely accidental, apparently.

OK, OK, we could do a lot better, with that producing tangible economic benefits. But how? Well, one approach would be for economists and econocrats to switch their sermonising from productivity to ethical behaviour.

Perhaps not. What would help is for ethical questions to get a lot more of our attention. As sociologists understand, but most economists don’t, businesses – like the rest of us – tend to want to do what others are doing. If we’re all being ethical, I don’t want to be seen as uninterested in ethical behaviour.

If we could give ethics a higher profile, we’d probably get more of it.

If expert advice on ethical problems was more readily available, more would be asked for. If there were more training and meetings and conferences on the topic, more decisions would be examined for their ethical implications.

Longstaff’s Ethics Centre has a proposal to improve our “ethical infrastructure” by teaming up with the universities of Sydney and NSW to establish an Australian Institute of Applied Ethics, which would be open to receiving requests from governments and the private sector to report on major ethical questions facing the nation. It would be a bit like the Productivity Commission or the Australian Law Reform Commission, but it would not be a government body.

It would also contribute to education, training and leadership development, building the practical skills of good decision-making on ethical issues in the private and public sectors.

Copying the pattern used to establish the hugely successful Melbourne-based Grattan Institute, the proposal is for the federal government to contribute $30 million towards a $40 million one-off endowment. The new institute would be funded from the earnings on this endowment, plus earnings from providing education, training and other services.

We’ll learn on budget night whether Chalmers and his boss are acting on this sensible idea for achieving a better economy, or whether they will be content with more platitudes on the need for greater productivity.

This article was originally published in The Sydney Morning Herald.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Feel the burn: AustralianSuper CEO applies a blowtorch to encourage progress

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

David Pocock’s rugby prowess and social activism is born of virtue

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why purpose, values, principles matter

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsClimate + Environment

BY Pia Curran 3 MAY 2024

According to the United Nations, the global population will increase by two billion over the next thirty years. This gives the idea of intergenerational justice particular weight. But philosophers struggle to discern the existence, nature and extent of any moral duty owed to future generations.

Issues of remoteness, non-identity, and economics leave many fixed in the parochialism of the present. Using British philosopher, Derek Parfit’s ‘person-affecting principle’ and the threshold notion of harm to argue that current generations do owe a moral duty to their heirs, existential threats to present and future people, such as climate change, should be dealt with through a pragmatic, sociological focus on distributive justice, encouraging a reinterpretation of justice as inter-temporal.

Relations between generations are ‘relations of domination’. Future people either have not come into existence, or they are too young to access the full rights of a democratic citizen. For some, this belies a ‘moral imperative to give voice to the voiceless’. Others resist giving ethical considerations to non-specific, non-existent things, and the future consequences of our actions are not certain. Indeed, future generations have not done anything to warrant our consideration, so obligations must come from some intrinsic value placed on human life.

Israeli political scientist, Avner de-Shalit suggests the existence of a ‘transgenerational community’ to which we owe a duty because we share ‘cultural interaction and moral similarity’. But deciphering how far into time this community stretches is difficult, and de-Shalit does not adequately address the different levels of obligation felt towards today’s youth and remote future people, with whom it is difficult to feel part of a community.

A more convincing argument is Derek Parfit’s ‘person-affecting principle,’ the ‘fundamental ethical requirement that humans have an obligation not to affirmatively harm a person.’

If everyone should be treated with respect and dignity no matter when they are born, we ought not to make decisions that will cause harm to future persons.

This deontological position is strengthened when considering an adaptation of Australian philosopher Peter Singer’s classic thought experiment. If it is equally important for an adult in Nepal who sees a drowning child to save the child as it is for you to save a drowning child in front of you, then spatial distance must be irrelevant to moral responsibility to prevent harm. By extension, why should temporal distance be any different? Tensions surrounding the personhood of the unborn should not keep present people from refraining from acts that will harm the interests of future people, whether or not they actually come into existence.

But Parfit does not define the meaning of ‘harm’, nor what level of care is owed to future generations. If a policy is criticised because it is predicted to worsen future standards of living, it could be said that all actions have some consequence for the lives of future people. If the act results in certain people not coming into existence, they cannot really be said to have been ‘harmed’ by the policy, because they never became a person.

Defining ‘harm’ through the notion of the threshold abates this problem. It does not require individuals to be worse off at a point in time than they otherwise would had a harmful act not been performed, only that they are worse off than they ought to be. Individuals are harmed if they come into existence in a sub-threshold state. This extends the notion of moral responsibility and intrinsic rights across time so that, ‘no child should do worse than some minimum standard that is determined by reference to the entire society,’ taking basic requirements such as food, water and shelter as a given.

Determining this threshold, however, is difficult. Buchanan suggests ‘better than our current median’ as an antidote to ‘better than me,’ because this acknowledges intragenerational disadvantage. The economic practice of ‘discounting’ the future, by contrast, entails a willingness to act on a preference for current generations. This discount rate ‘dramatically diminishes the significance of policy effects on future generations.’

The issue then becomes one of balance. How do we balance our obligations not to inflict harm on ourselves, and the sometimes competing aim to not inflict harm on future individuals? Focusing on fiscal policy, Buchanan suggests a focus on ‘distributive justice,’ pressing the need to weigh all claims and redistribute resources away from the ‘richest’ to the ‘poorest,’ irrespective of when those people may be alive. For example, higher taxation for the rich and more investment in welfare and public infrastructure of the future. The aim is to reach a level of wellbeing ‘according to which both currently and future living people are able to reach a sufficientarian threshold.’

Issues posing existential threats to present and future people have a particular moral primary in terms of harms to avoid. Climate change, especially rising global temperatures, poses irreversible and universal damage. Using the threshold concept of harm, one assumes that future generations ought to live in a clean and safe environment, and current generations ought to act in ways that avoid environmental degradation. But, given that sustainable energy is more expensive than fossil fuels, there exists a tension between economic growth and ecological protection.

Irish sociology lecturer, Tracey Skillington takes a sociological rather than philosophical approach, arguing that ‘the needs of the capitalist present have taken precedence over all other concerns,’ noting the insufficient efforts taken to prevent environmental harm. If all focus is on present concerns, justice is not equitably distributed to the future. Skillington sees this as a flaw in the present liberal-democratic political infrastructure.