Israel or Palestine: Do you have to pick a side?

Israel or Palestine: Do you have to pick a side?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 27 OCT 2023

We are inclined to pick a side in complex conflicts, but doing so can diminish our ethical point of view.

In the early hours of 7 October 2023, Hamas launched a barrage of rockets from Gaza into Israel while armed terrorists crossed the border and began a rampage of death and destruction targeting civilians, including children. In the days that followed, Israeli forces retaliated by blockading Gaza, cutting off food, electricity and water supplies, and began bombarding the densely populated city, killing thousands of Palestinian civilians, including children.

When our news screens are filled with footage of such horrors, our moral minds cry out for justice. But justice for whom?

One of the quirks of our moral minds is that we tend to see the world in terms of black and white or good and evil. If we hear about a heinous or unjust act, our sympathies go out to the victims while outrage inspires us to want the perpetrators to be punished. This sorts the world into two categories: the wronged, who deserve sympathy and protection, and the wrongdoers, who are morally diminished or even dehumanised.

Another quirk of our moral minds is that we struggle with ambivalence, which is the ability to see something as being both good and bad at the same time. Once someone – or a group – are painted as the wronged, it’s difficult to also perceive them simultaneously as being wrongdoers in some other capacity. Attempting to do so creates an uncomfortable state of dissonance, and the easiest way to resolve it is to dismiss the troubling thought and collapse things back into black and white.

On top of this we have our personal connections and affiliations, or a sense of shared identity that can cause us to feel solidarity with one side rather than the other. This in-group solidarity is then reinforced through shared expressions of grief and outrage. It is also policed, with any signs of sympathy for the “other side” drawing stiff rebuke.

This is all natural. It’s how our moral minds are wired. So, it’s no surprise that in the case of the Israel-Palestine conflict, many people have already picked a side. But just because it’s a natural inclination doesn’t mean it’s always a healthy one.

Picking a side can shrink our view, making us see the world through that side’s ethical lens and dismissing other possibly valid perspectives.

This is particularly apparent when we’re faced with gaps in the information we receive – as we often are during times of conflict. We tend to fill ambiguity with our own biases, and we seek out information to reinforce our view while discounting evidence to the contrary.

Picking sides can also prevent us from seeing the bigger ethical picture. And in the case of the conflict between Israel and Palestine, the bigger picture is a long history laced with ethical complexities.

However, there is another way. It requires us to acknowledge, but not necessarily follow, our moral intuitions, and instead step back to take a more universal ethical point of view. This is not the same as a neutrality that is indifferent to the claims of either side or to questions of right and wrong. It is taking the side of principle, which is a basis by which we can judge all parties.

Justice for all

Most ethical frameworks offered by philosophers are universalist, in the sense that they apply equally to all morally worthwhile individuals in similar situations. So, if you believe that it’s wrong to kill a particular individual because they’re an innocent civilian, then you should also believe that it’s wrong to kill any individual who is an innocent civilian.

You might justify that in consequentialist terms, such as by arguing that killing innocent civilians causes undue and irrevocable harm, and that the world is a better place when civilians are protected from such harm. You could equally justify it using a rights-based ethics, such as by arguing that all people have a fundamental right to life and safety.

While philosophers have a variety of views on which specific ethical framework or universal principles we ought to adopt, there are some principles that are widely accepted, with many being coded into the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These include things like a right to life, liberty and security of person, a right to freedom of movement within the borders of one’s state, and that people shall not be arbitrarily deprived of property, as well as a right to the free expression of one’s religion.

The virtue of taking such a principled approach is that is gives us a bedrock upon which we can base our judgements of any action, agent or government. It promotes a sympathetic stance towards all suffering, and aims us towards justice for all, without shying away from condemning that which is harmful or unjust.

It might challenge our partisan feelings that favour the interests of one side over the other, but it urges us to condemn wrongdoing on any side, such attacks targeting civilians or waging war without ethical constraint.

A principled perspective also enables us to navigate complex ethical issues, such as saying that the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land might be unjust, but that it shouldn’t justify Hamas attacking civilians. Or that Hamas’s attacking civilians is clearly morally repugnant, but that shouldn’t justify the collective punishment of Gazans by Israel. And it can allow us to assert that Israel might have a right to defend its territory and citizens from attack, but it – indeed, all parties – must adhere to just war principles, such as proportionality and distinguishing between enemy combatants and civilians. And it ought to reinforce our commitment to seeing a lasting peace in the region, which will inevitably require some compromises on both sides.

Of course, even if everyone agreed on the same set of principles, there will still be substantial differences in interpretation or points of view. A principled stance must also acknowledge that there are fundamental incompatibilities between the interests and demands of both sides that no single ethical framework will be able to resolve without some kind of compromise. For example, when both sides claim certain sites as sacred, and demand exclusivity, there is no way to resolve that without compromise that will be deemed unacceptable to at least one side. However, such uncertainties and complexities don’t undermine the fact that the same universal principles ought to apply to all people involved.

Choosing to side with ethical principle rather than one side or the other is not without its challenges. It forces us to push back on some of our deep moral intuitions and sit with ambivalence and ambiguity. We might be admonished by both sides in the conflict for not backing all their claims, or called a traitor for criticising them. However, the strength is that we can respond to each of these challenges by resorting to the universal principles, compassion and desire for justice that underpins our views on both sides of the conflict.

While the internet and media landscape seem to urge us to take sides in any conflict, it is entirely possible – and often wise – to step back and apply a broader set of principles rather than fall in with a particular partisan perspective. Adopting such a principled stance doesn’t require that you have all the solutions to the conflict, it is sufficient that you have good reason to wish for a just and peaceful solution for all involved.

Image: AAP Photo / Erik S. Lesser

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Trump and the failure of the Grand Bargain

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The erosion of public trust

Big Thinker: Karl Marx

Karl Marx (1818-1883) was a philosopher, economist, and revolutionary thinker whose criticisms of capitalism and breakdowns of class struggle continue to influence contemporary thought about economic inequality and the worth of individual labour.

He was not only a prominent figure in the world of philosophy but also a key player in economic and political theory. Marx’s life and work were deeply intertwined with the tumultuous historical backdrop of the 19th century, marked by the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism.

Born in Trier, Prussia (now in Germany), Marx began with a focus on law and philosophy at the University of Bonn and later at the University of Berlin. During his time in Berlin, he encountered the ideas of G.W.F. Hegel, whose methods significantly influenced Marx’s own philosophical approach.

In collaboration with Friedrich Engels, Marx developed and refined his ideas, culminating in some of the most influential works in the history of political philosophy. For example, his infamous The Communist Manifesto (1848) and Das Kapital (1867, 1885, 1894).

Historical materialism and class struggle

One of Marx’s central ideas was historical materialism, a theory that analyses the evolution of societies through the lens of economic systems. According to Marx, the structure of a society is primarily determined by its mode of production: the ways commodities and services are produced and distributed, and the social relations that affect these functions. In capitalist societies, the means of production are privately owned, leading to a class-based social structure separating the owners and the workers.

Marx’s analysis of class struggle underscores the ethical imperative of addressing economic inequality. He argued that under capitalism, the bourgeoisie (owners of the means of production) exploit the proletariat (the working class) for their own profit. This exploitation, he claims, is the engine that drives the capitalist system, where workers are paid less than the value of their labour while the bourgeoisie reap the profits. This exploitation also results in alienation, where workers are estranged from the full effects of their labour and, Marx argues, even from their own humanity.

Marx’s arguments call for a reevaluation of the inherent fairness of such a system. He questions the morality of a society where wealth and power are concentrated in the hands of a few while the masses toil in poverty. This is an ethical challenge that continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about income inequality and social justice.

Marx’s critique challenges us to consider whether a society that values profit and efficiency over the well-being and fulfillment of its members is ethically justifiable.

To address this concern, Marx envisioned a classless society, where the means of production would be collectively owned. This transition, he believed, would eliminate the inherent exploitation of capitalism and lead to a more just and equitable society. While the practical realisation of this vision has proven challenging, it remains a foundational ethical ideal for some, emphasising the need to confront economic disparities for the sake of human dignity and fairness.

Critique of capitalism and commodification

Marx’s critique of capitalism extended beyond its class divisions. He also examined the profound impact of capitalism on human relationships and the commodification of virtually everything, including labour, under this system. For Marx, capitalism reduced individuals to mere commodities, bought and sold in the labour market.

Marx’s critique of commodification highlights the importance of valuing individuals beyond their economic contributions. He argued that in a capitalist society, individuals are often reduced to their economic worth, which can erode their sense of self-worth and dignity. Addressing this ethical concern calls for recognising the intrinsic value of every person and fostering functions in societies that prioritise human well-being over profit.

The communist vision

Marx’s ultimate vision was communism, a classless society where resources would be shared collectively. In such a society, the state as we know it would wither away, and individuals would contribute to the common good according to their abilities and receive according to their needs.

This communist vision raises questions about the ethics of property and ownership. It challenges us to rethink the distribution of resources in society and consider alternative models that prioritise equity and communal well-being. While achieving a truly communist society might be complex or even out of reach, the aspiration of creating a world where everyone’s needs are met and individuals contribute to the best of their abilities is still a general ethical ideal many people intuitively strive for.

Despite this, Marx’s ideas have faced much criticism. Many believe that a classless society with a centralised power risks authoritarianism, Marx’s economic planning lacked detail, communism goes against human nature of self-interest and competition, and historical and contemporary communist systems face large practical challenges.

In spite of, and sometimes because of, these challenges, Marx’s ideas continue to spark ethical discussions about economic inequality, commodification, and the nature of human relationships in contemporary society. His legacy serves as a reminder of the enduring importance of grappling with questions of justice, equality, and human dignity in our ever-evolving social and economic landscapes.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

What your email signature says about you

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

‘Hear no evil’ – how typical corporate communication leaves out the ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethics of making money from JobKeeper

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pay up: income inequity breeds resentment

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 6 OCT 2023

Ethical dilemmas are, by their nature, uncomfortable or difficult to tackle, but they can also teach us a lot about our own values and principles and prepare us for an ethically complex world.

You’re about to take a major exam that will determine whether you get accepted into a potentially life-changing course. But you hear that there’s a leaked copy of the exam paper doing the rounds, and other students are studying it carefully. There are only a precious few spots available in your desired course, and if you don’t also sneak a peek at the leaked exam paper, you are likely to miss out. Should you cheat by looking at the leaked exam paper, given you know other students are doing the same?

How about if you found out that the company you work for was partnering with an overseas contractor known for running sweatshops and flouting labour laws, meanwhile your company’s branding is all about how ethical and sustainable it is. Would you speak out to management, or on social media, even if doing so might cost you your job and income?

If these scenarios give you pause, you’re not alone. Each represents a different kind of ethical dilemma we might come across, and by their nature they can be highly unsettling and difficult – if not impossible – to resolve in a way that satisfies everyone involved.

But what makes something an ethical dilemma? It’s important to note that an ethical dilemma is not a simple question of doing the ‘right’ thing or the ‘wrong’ thing, like whether you should lie to cover up for something bad that you did.

A genuine ethical dilemma arises when there is a clash between two values (i.e., what you think is good) or principles (i.e., the rules you follow). Or it can be a choice between two bad outcomes, like knowing that whatever you do, someone will get hurt.

That’s what makes them so uncomfortable; we feel like whatever choice we make will involve some kind of compromise.

All in the mind

One way to prepare yourself to face real-world ethical dilemmas is to strengthen your moral muscle by practicing on hypothetical scenarios – a staple of philosophy classes.

Consider this: you’re the captain of a sinking ship, and the lifeboat only has room for five passengers. Yet there are seven people aboard the ship, including yourself. Whom do you choose to board the lifeboat? The pregnant woman? The ageing brain surgeon? The fit young fisherman? The teenage twins? The reformed criminal who is now a priest? Yourself?

Or how about this: you’ve just started your shift as the only surgeon in a small but high-tech hospital. As you walk into your ward, you’re presented with five dying patients. You know nothing else about their personal details except that each is suffering from a different organ failure. Without assistance, all will die within 24 hours. However, at that moment, a healthy patient is wheeled in for an unrelated minor procedure. You also know nothing about their personal circumstances, but you do know they have five perfectly healthy organs. Were you to allow that patient to die (as they will without treatment) you know you could save the lives of the other five dying patients. Would you allow one to die to save five?

Each of these scenarios is carefully constructed to put pressure on your ethical intuitions and force you to make difficult decisions.

Tackling a hypothetical dilemma gives you an opportunity to reflect on your own values and principles, and search for good reasons to justify your choices.

Even if the hypothetical situation is absurdly unreal, you can still learn a lot about yourself and your ethical stance by considering how you would act in these cases.

Your first impulse might be to try and change the circumstances to eliminate or minimise the dilemma. We might speculate that we could squeeze another person on the lifeboat, or that the organ transplants may not succeed, and that might make our decisions easier. This is entirely natural – and sensible – especially because dilemmas in the real world are rarely as clear cut. But dodging the dilemma misses the point of the exercise.

You might decide that a consequentialist approach is the best one for the lifeboat scenario, causing you to pick the people who might end up leading the richest lives or having the most positive impact on others. But you might decide that a deontological approach is most appropriate for the surgeon’s dilemma, arguing that it’s inherently wrong to withhold treatment from an ‘innocent’ patient, even if it ends up saving lives.

It’s important to remember that hypothetical dilemmas like this are designed so that there’s likely no simple answer that will satisfy everybody. Even reasonable people can disagree about what course of action to take. That’s fine. The important bit is not really the answer you come to but the reasons you give to support it. That’s what ethics is all about: finding good reasons to act the way we do.

Most of us are likely to go through life without ever having to put people in lifeboats or contemplate the death of one to save five, but by testing ourselves with these dilemmas we can build our ethical muscles and be more ready to face other dilemmas that world could throw at us at any time.

If you’re struggling with a real-life ethical dilemma, it can be tough finding the best path forward. Ethi-call is a free independent helpline offering decision-making support from trained ethics counsellors. Book a call today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Confucius

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

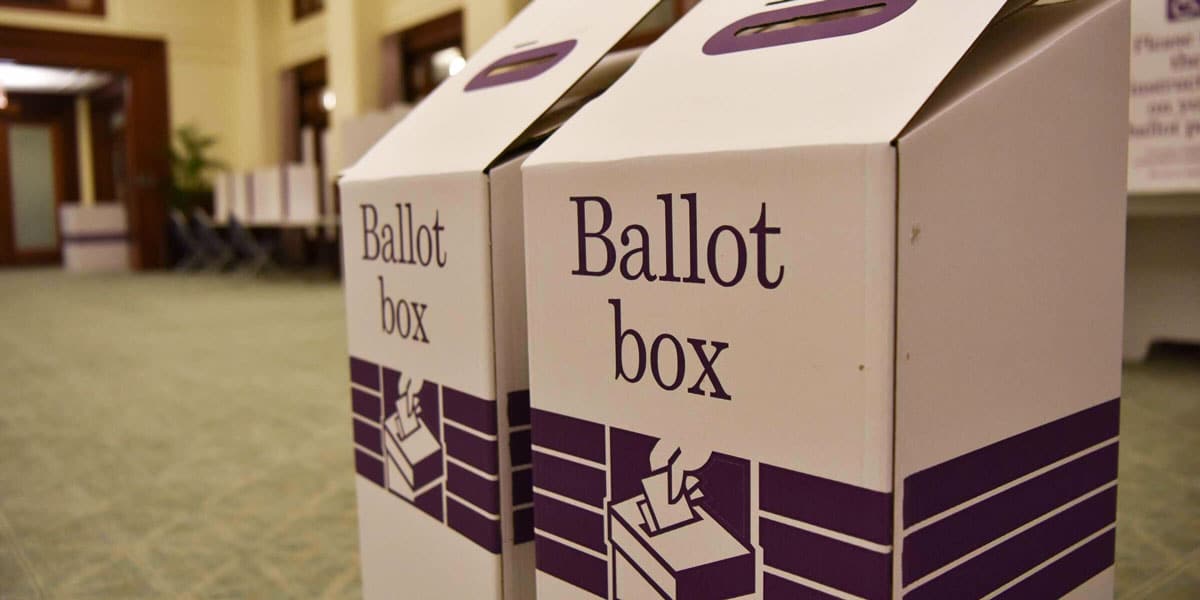

You’re the Voice: It’s our responsibility to vote wisely

You’re the Voice: It’s our responsibility to vote wisely

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 13 SEP 2023

The Voice referendum is a high stakes decision that could affect many thousands of lives, and that means we have an ethical responsibility to choose how we vote carefully.

Not all decisions are created equal. Some are trivial in their consequences, like whether you choose the chocolate or strawberry ice cream for dessert. Some have higher stakes, like whether you decide to prioritise your career over travelling the world. Yet, these decisions still only affect how you live and are unlikely to impact anyone else.

You can make these decisions in a considered or a flippant way. Or you can choose to not make them at all (although doing so is still making a choice, of sorts). With low stakes personal decisions, you don’t even need to have a good reason for choosing what you do. The only person to whom you owe a justification is yourself – and you can always choose to free yourself of that burden.

But there are other kinds of decisions, ones that impact not just us but other people too. Decisions like these demand more from us and we cannot be so flippant with them. In these cases, we have a greater ethical responsibility to come to a more considered position, to weigh up the options more carefully, and be ready to justify our decision with good reasons.

This is the type of decision are we making when it comes to the Voice to Parliament referendum.

The stakes

In the case of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, the stakes are whether Indigenous peoples are afforded constitutional protection for a consultatory body that will advise government on legislation affecting their communities – a body that cannot be legislated away with a change of government.

Leading Indigenous figures representing peoples from across Australia and the Torres Strait have asked the Australian people to make the constitutional change because they believe such a consultatory body will have a significant impact on the wellbeing of their peoples and will help correct over two centuries of political disempowerment and discrimination.

Be a good citizen

So, you have a decision to make, one that will likely have a significant impact on a vulnerable population. That places an ethical responsibility on each registered voter to take the decision seriously. This means not treating it flippantly and having a principled reason for voting, regardless of which way you vote. This is what it means to be a “good citizen”.

It’s easy to think of citizenship as simply affording us rights, such a right to have a say in how we’re governed or a right to be treated fairly under the law. However, citizenship also bestows upon us responsibilities, like voting in elections and serving on a jury if called.

But these are just the minimal responsibilities involved in citizenship. We need to do more to be a “good citizen”, including keeping ourselves engaged in issues of public significance and maintaining a basic level of political literacy. A good citizen also doesn’t just grumble about the state of society, they act to make it better. Finally, a good citizen sees themselves as members of an interconnected society, and is willing to make sacrifices or compromise for the common good. So, a good citizen will see the Voice referendum as an opportunity to exercise their responsibilities and engage with the issue actively to make an informed decision.

Be informed

The good news is that there is an abundance of information readily available for each of us to come to a principled decision. However, there is also a wealth of misinformation and disinformation floating around as well. Some of this is shared due to genuine confusion and some is spread by bad faith actors who have their own motivations for attempting to sway votes.

Explore what you really think

This is why it’s important to look at who is speaking and understand their motivations, which might not always be reflected in their arguments. Many people are motivated to vote one way or the other simply because that’s how their perceived political allies are voting, or they might be swayed by unconscious biases and use plausible sounding arguments as post-hoc rationalisations for how they feel deep down.

You can tell that someone is pushing post-hoc rationalisations when you successfully challenge their argument, such as by showing they have been duped by misinformation, but they still don’t change their mind. In this case, simply throwing more facts at them is unlikely to sway them.

A more successful approach is to be sceptical that the first reasons they give are the true motivations for their views. Instead, ask more questions about why they believe what they do and what they’re concerned will happen if the vote doesn’t go their way. Ask questions about how they can be confident their facts are true or what it would take to change their mind.

Rather than positioning yourself as an opponent, try taking the stance as a fellow traveller trying to get to the bottom of the matter. If you’re able to show respect, build trust and lower defensiveness, you’ll have a better chance of opening their mind to alternative perspectives – although it’s also crucial to remain open to alternate perspectives yourself.

There is no right answer

This is because there is no one “right answer” to the referendum question. Reasonable people can disagree on whether a Voice to Parliament is the best mechanism to promote the welfare and representation of Indigenous peoples, or whether a Voice ought to be enshrined in the constitution. When discussing the issue with others, it’s easy to assume that people who disagree with us must harbour some problematic views or that they are simply misguided. Resist that urge and ask questions that aim to tease out good reasons for or against the Voice.

The stakes involved in the Voice referendum mean that we should all take our responsibility to vote in a considered way seriously, and we should be mindful of how we make our decision. Even though there are many pressing issues facing the Australian public, from the cost of living through to climate change, that doesn’t mean we can’t also engage with the longstanding issue of Indigenous disadvantage, especially because there’s often not much we can do about many big issues but we’ve been explicitly invited to have a say on the Voice.

For everything you need to know about the Voice to Parliament visit here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

A foot in the door: The ethics of internships

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

Imagine a large, cosmopolitan city, where people from uncountable backgrounds and with numerous beliefs all thrive together. People embrace different cultural traditions, speak varying languages, enjoy countless cuisines, and educate their children on diverse histories and practices.

This is the kind of pluralism that most people are familiar with, but a diverse and culturally integrated area like this is specifically an example of cultural pluralism.

Pluralism in a general sense says there can be multiple perspectives or truths that exist simultaneously, even if some of those perspectives are contradictory. It’s contrasted with monism, which says only one kind of thing exists; dualism, which says there are only two kinds of things (for example, mind and body); and nihilism, which says that no things exist.

So, while pluralism more broadly refers to a diversity of views, perspectives or truths, cultural pluralism refers specifically to a diversity of cultures that co-exist – ideally harmoniously and constructively – while maintaining their unique cultural identities.

Sometimes an entire country can be considered culturally pluralistic, and in other places there may be culturally pluralistic hubs (like states or suburbs where there is a thriving multicultural community within a larger more broadly homogenous area).

On the other end of the spectrum is cultural monism, the idea that a certain area or population should have only one culture. Culturally monistic places (for example, Japan or North Korea) rely on an implicit or explicit pressure for others to assimilate. Whereas assimilation involves the homogenisation of culture, pluralism encourages diversity, often embracing people of different ethnic groups, backgrounds, religions, practices and beliefs to come together and share in their differences.

A pluralistic society is more welcoming and supportive of minority cultures because people don’t feel pressured to hide or change their identities. Instead, diverse experiences are recognised as opportunities for learning and celebration. This invites travel and immigration, and translates into better mental health for migrants, the promotion of harmony and acceptance of others, and enhances creativity by exposing people to perspectives and experiences outside of their usual remit.

We also know what the alternative is in many cases. Australia has a dark history of assimilation practices, a symptom of racist, colonial perspectives that saw the decimation of First Nations people and their cultures. Cultural pluralism is one response to this sort of cultural domination that has been damaging throughout history and remains so in many places today.

However, there are plenty of ethical complications that arise in the pursuit of cultural plurality.

For example, sociologist Robert D. Putnam published research in 2007 that spoke about negative short-medium term effects of ethnically diverse neighbourhoods. He found that, on average, trust, altruism and community cooperation was lower in these neighbourhoods, even between those of the same or similar ethnicities.

While Putnam denied that his findings were anti-multicultural, and argues that there are several positive long-term effects of diverse societies, the research does indicate some of the risks associated with cultural pluralism. It can take a large amount of effort and social infrastructure to build and maintain diverse communities, and if this fails or is done poorly it can cause fragmentation of cultural communities.

This also accords with an argument made by journalist David Goodhart, that says people are generally divided into “Anywheres” (people with a mobile identity) and “Somewheres” (people, usually outside of urban areas, who have marginalised, long-term, location-based identities). This incongruity, he says, accounts for things like Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, because they speak to the Somewheres who are threatened by changes to their status quo. Pluralism, Goodhart notes, risks overlooking the discomfort these communities face if they are not properly supported and informed.

Other issues with pluralism include the prioritisation of competing cultural values and traditions. What if one person’s culture is fundamentally intolerant of another person’s culture? This is something we see especially with cultures organised around or heavily influenced by religion. For example, Christianity and Islam are often at odds with many different cultures around issues of sexual preference and gendered rights and responsibilities.

If we are to imagine a truly culturally pluralistic society, how do we ethically integrate people who are intolerant of others?

Pluralism as a cultural ideal also has direct implications for things like politics and law, raising the age-old question about the relationship between morality and the law. If we want a pluralistic society generally, how do the variations in beliefs, values and principles translate into law? Is it better to have a centralised legal system or do we want a legal plurality that reflects the diversity of the area?

This does already exist in some capacity – many countries have Islamic courts that enforce Sharia law for their communities in addition to the overarching governmental law. This parallel law-enforcement also exists in some colonised countries, where parts of Indigenous law have been recognised. For example, in Australia, with the Mabo decision.

Another feature of genuine cultural pluralism that has huge ethical implications and considerations is diversity of media. This is the idea that there should be (that is, a media system that is not monopolised) and diverse representation in media (that is, media that presents varying perspectives and analyses).

Firstly, this ensures that media, especially news media, stays accountable through comparison and competition, rather than a select powerful few being able to widely disseminate their opinions unchecked. Secondly, it fosters a greater sense of understanding and acceptance by exposing people to perspectives, experiences and opinions that they might otherwise be ignorant or reflexively wary of. Thirdly, as a result, it reduces the risk that media, as a powerful disseminator of culture, could end up creating or reinforcing a monoculture.

While cultural pluralism is often seen as an obviously good thing in western liberal societies, it isn’t without substantial challenges. In the pursuit of tolerance, acceptance and harmony, we must be wary of fragmenting cultures and ensure that diverse communities have adequate social supports to thrive.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 11 JUL 2023

Judith Jarvis Thomson (1929-2020) is one of the most influential ethicists and metaphysicians of the 20th century. She’s known for changing the conversation around abortion, as well as modernising what we now know as the trolley problem.

Thomson was born in New York City on October 4th, 1929. Her mother was Catholic of Czech heritage and her father was Jewish, who both met at a socialist summer camp. While her parents were religious, they didn’t impose their beliefs on her.

At the age of 14, Thomson converted to Judaism, after her mother died and her father remarried a Jewish woman two years later. As an adult, she wasn’t particularly religious but she did describe herself publicly as “feel[ing] concern for Israel and for the future of the Jewish people.”

In 1950, Thomson graduated from Barnard College with a Bachelor of Arts (BA), majoring in philosophy, and then received a second BA in philosophy from Cambridge University in England in 1952. She then went on to receive her Masters in philosophy from Cambridge in 1956 and her PhD in philosophy from Columbia University in New York in 1959.

Violinists, trolleys and philosophical work

Even though she had received her PhD from Columbia, the philosophy department wouldn’t keep her as a professor as they didn’t hire women. In 1962, she began working as an assistant professor at Barnard college, though she later moved to Boston University and then MIT with her husband, James Thomson, for the majority of her career.

Thomson is most famous for her thought experiments, especially the violinist case and the trolley problem. In 1971, Thomson published her book A Defense of Abortion, which presented a new kind of argument for why abortions are permissible during a time of heightened debate in the US as a result of the second wave feminist movement. Arguments that defended a woman’s right to an abortion circulated feminist publications and eventually led to the Supreme Court ruling in favour of Roe v. Wade (1973).

“Opponents of abortion commonly spend most of their time establishing that the foetus is a person, and hardly any time explaining the step from there to the impermissibility of abortion.” – Judith Jarvis Thomson

The famous violinist case asks us to imagine if it is permissible to “unplug” ourselves from a famous violinist, even if it is only for nine months and being plugged in is the only thing keeping them alive. As Thomas Nagel said, “she expresses very clearly the essentially negative character of the right to life, which is that it’s a right not to be killed unjustly, and not a right to be provided with everything necessary for life.” To this day, the violinist case is taught in classrooms and recognised as one of the most influential thought experiments arguing for the permissibility of abortion.

Thomson is famous for another famous thought experiment, the trolley problem. In her 1976 paper “Killing, Letting Die and the Trolley Problem,” Judith Jarvis Thomson articulates a famous thought experiment, first imagined by Philippa Foot, that encourages us to think about the moral relevance of killing people, as opposed to letting people die by doing nothing to save them.

In the trolley problem thought experiment, a runaway trolley will kill five innocent people unless someone pulls a lever. If the lever is pulled, the trolley will divert onto a different track and only one person will die. As an extension to Foot’s argument, Thomson asks us to think if there is something different about pushing a large man off a bridge, thereby killing him, to prevent five people from dying from the runaway trolley. Why does it feel different to pull a lever rather than push a person? Both have the same potential outcomes and distinguish between killing a person and letting a person die.

In the end, what Thomson finds is that oftentimes, the action as well as the outcome are morally relevant in our decision making process.

Legacy

Thomson’s extensive philosophical career hasn’t gone unnoticed. In 2012, she was awarded the American Philosophical Association’s prestigious Quinn Prize for her “service to philosophy and philosophers.” In 2015, she was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Cambridge, and then in 2016 she was awarded another honorary doctorate from Harvard.

Thomson continues to inspire women in philosophy. As one of her colleagues, Sally Haslanger, says: “she entered the field when only a tiny number of women even considered pursuing a career in philosophy and proved beyond doubt that a woman could meet the highest standards of philosophical excellence … She is the atomic ice-breaker for women in philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Billionaires and the politics of envy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The rights of children

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics explainer: Normativity

Have you ever spoken to someone and realised that they’re standing a little too close for comfort?

Personal space isn’t something we tend to actively think about; it’s usually an invisible and subconscious expectation or preference. However, when someone violates our expectations, they suddenly become very clear. If someone stands too close to you while talking, you might become uncomfortable or irritated. If a stranger sits right next to you in a public place when there are plenty of other seats, you might feel annoyed or confused.

That’s because personal space is an example of a norm. Norms are communal expectations that are taken up by various populations, usually serving shared values or principles, that direct us towards certain behaviours. For example, the norm of personal space is an expectation that looks different depending on where you are.

In some countries, the norm is to keep distance when talking to strangers, but very close when talking to close friends, family or partners. In other countries, everyone can be relatively close, and in others still, not even close relationships should invade your personal space. This is an example of a norm that we follow subconsciously.

We don’t tend to notice what our expectation even is until someone breaks it, at which point we might think they’re disrespecting personal or social boundaries.

Norms are an embodiment of a phenomenon called normativity, which refers to the tendency of humans and societies to regulate or evaluate human conduct. Normativity pervades our daily lives, influencing our decisions, behaviors, and societal structures. It encompasses a range of principles, standards, and values that guide human actions and shape our understanding of what’s considered right or wrong, good or bad.

Norms can be explicit or implicit, originating from various sources like cultural traditions, social institutions, religious beliefs, or philosophical frameworks. Often norms are implicit because they are unspoken expectations that people absorb as they experience the world around them.

Take, for example, the norms of handshakes, kisses, hugs, bows, and other forms of greeting. Depending on your country, time period, culture, age, and many other factors, some of these will be more common and expected than others. Regardless, though, each of them has a or function like showing respect, affection or familiarity.

While these might seem like trivial examples, norms have historically played a large role in more significant things, like oppression. Norms are effectively social pressures, so conformity is important to their effect – especially in places or times where the flouting of norms results in some kind of public or social rebuke.

So, norms can sometimes be to the detriment of people who don’t feel their preferences or values reflected in them, especially when conformity itself is a norm. One of the major changes in western liberal society has been the loosening of norms – the ability for people to live more authentically themselves.

Normative Ethics

Normativity is also an important aspect of ethical philosophy. Normative ethics is the philosophical inquiry into the nature of moral judgments and the principles that should govern human actions. It seeks to answer fundamental questions like “What should I do?”, “How should I live? and “Which norms should I follow?”. Normative ethical theories provide frameworks for evaluating the morality of specific actions or ethical dilemmas.

Some normative ethical theories include:

- Consequentialism, which says we should determine moral valued based on the consequences of actions.

- Deontology, which says we should determine moral value by looking at someone’s coherence with consistent duties or obligations.

- Virtue ethics, which focuses on alignment with various virtues (like honesty, courage, compassion, respect, etc.) with an emphasis on developing dispositions that cultivate these virtues.

- Contractualism, informed by the idea of the social contract, which says we should act in ways and for reasons that would be agreed to by all reasonable people in the same circumstances.

- Feminist ethics, or the ethics of care, which says that we should challenge the understand and challenge the way that gender has operated to inform historical ethical beliefs and how it still affects our moral practices today.

Normativity extends beyond individual actions and plays a significant role in shaping societal norms, as we saw earlier, but also laws and policies. They influence social expectations, moral codes, and legal frameworks, guiding collective behavior and fostering social cohesion. Sometimes, like in the case of traffic laws, social norms and laws work in a circular way, reinforcing each other.

However, our normative views aren’t static or unchangeable.

Over time, societal norms and values evolve, reflecting shifts in normative perspectives (cultural, social, and philosophical). Often, we see social norms culminating in the changing of outdated laws that accurately reflected the normative views of the time, but no longer do.

While it’s ethically significant that norms shift over time and adapt to their context, it’s important to note that these changes often happen slowly. Eventually, changes in norms influence changes in laws, and this can often happen even more slowly, as we have seen with homosexuality laws around the world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There’s no good reason to keep women off the front lines

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How much should politics influence my dating decisions?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we shouldn’t be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 22 MAY 2023

Later this year Australians will be asked to vote in a referendum on a Voice to Parliament. Can this conversation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander constitutional recognition reconcile the truth of Australia’s past? Or have we embarked on a new era of reckoning with the risk that comes with a referendum?

In April 2022, Proud Wiradjuri and Wailwan woman and lawyer, Teela Reid sat down with Dr Simon Longstaff AO to discuss what reckoning means to her, what we need to make an informed decision on this vote, and what it means for us – collectively and individually.

Dr Simon Longstaff: When I think of reckoning, three things come to mind. Firstly, there’s ‘reckoning’ as in finding your bearings, dead reckoning. There’s another sense in which you reckon up the bill. And then there’s the third sense in which reckoning can be taken as a moment of recognition of one’s responsibilities and making us confront the reality of who and where we are, and what we’ve done. Perhaps we can touch on all three of those…

Teela Reid: My essay, Reckoning, Not Reconciliation, was born out of a frustration with the concept of reconciliation. I had attempted to dismiss it in some ways – whether that was to be provocative or just trying to grapple with my own sense of the world. The past three, almost four decades, has been defined in so-called Australia under this notion of reconciliation. And so, for me, as a Wiradjuri Wailwan woman, the life that I have been fortunate to live, had nothing to do with reconciliation, but it was in fact in spite of it. For me, having grown up in my community with the stories of my ancestors, my paternal and maternal lineages being hounded onto missions, laws passed so we couldn’t speak our native tongue, this notion of reconciliation kind of popped up.

I remember growing up in that community and then walking into school where we were trained that this notion of reconciliation was to make us feel good. There was almost a sense of denial of the truth. I remember, for example, learning about the Anzacs and there were no soldiers that we were told about that were Aboriginal men or women. And then I’d walk home and my grandparents would sit me around the campfire and give me a whole different education.

I remember just feeling really frustrated with the world. I want to unravel that and unpack this notion of reckoning. To me, it’s about everyone on this continent embracing the discomfort of the hard work we need to get done.

Dr Simon Longstaff: How do you look at the obligations you have – in a structure where elders still are the most significant decision makers within a community – and the need to balance that cultural obligation with obligations arising in a structure like the law; where it’s about the quality of reason, the precision of language and the authority of precedent?

Teela Reid: The western law is a discipline, it’s a practice. I vividly recall being at law school wanting to throw my textbooks up against the library when we were learning about Dicey’s rule of law where we’re all equal before the law. I remember thinking “How do I reconcile this with the stories that I know?” Clearly, the law has never treated my people fairly. There’s never been a fair go in this country for First Nations Peoples. So having those stories in my heart and in my spirit, I still took the opportunity that I was given to go to law school and now to practice law. It’s something I don’t take lightly at all, because I think we would be much worse off as a peoples if we were to take those opportunities for granted and not do the hard yards and live out those opportunities to empower our people.

Dr Simon Longstaff: Can these different definitions of ‘reckoning’ exist side by side? Or is that a very significant tension in your life?

Teela Reid: It’s a constant tension, to be very frank. It is a very constant tension to not lose yourself as a First Nations woman in this place that’s now called Australia and you’re constantly walking a fine line. When I think about reckoning, it’s also about power. It’s about who has the authority to make decisions in different contexts while at the community level our governance systems operate in a very specific way. I think that’s what Australia forgets. We have very ancient governance systems here still very much intact. They might not be written in legislation or rule books, but they’re passed down orally through our ways of knowing and being.

We have this higher order in Australia where there’s parliament, there’s states, there’s territories, there’s people making all these different decisions, but at the very heart of that, there is still the omission of the First Nations and there’s still an act of erasure in that. And the symbols are everywhere. It’s in the flag, it’s in the anthem, it’s in these ways that Australians speak their identity that I just don’t relate to.

Dr Simon Longstaff: The concept of ‘payback’ is sometimes misunderstood as if it’s based in the need for revenge. Instead, it’s about those who have done wrong making restoring balance to the community – paying back what has been taken to those who have suffered loss. Is that the kind of reckoning that you have in mind – bringing it to that point where people recognise loss as a give and take?

Teela Reid: It’s about the reconciling of the balance. There does need to be compensation, there does need to be these tough decisions and reparations for what First Nations Peoples have lost there.

The other way in which I see it, there is a level of discomfort that comes down to this truth telling notion that we’re going to need to embrace. Where Australians are at now – each one of you are advocates, you’re campaigners. You have agency in this movement. Reckoning is going to be a really difficult process, unlike reconciliation where we’ve all felt good with our wraps, our cupcakes and our teas. No, this is going to be quite difficult.

For so long, for 250+ years, as a nation we’ve avoided that discomfort that comes with trying to heal these wounds. Because you might not see the physical wounds, but they’re very deep and they’re intergenerational. When we think of reckoning, we’re all going to have to step up to the plate. And often what happens in a truth telling process, it’s that First Nations Peoples get the onus of having to speak our truth, when in fact white Australia needs to speak its truth. What did your ancestors do to my ancestors? Let’s start to have an open dialogue and take responsibility for that pain. Because I don’t think that we can heal until we reckon with the discomfort and the pain that I think as a nation is going to take many years to get through.

Dr Simon Longstaff: Whatever the result, the proposed referendum on a Voice to Parliament is going to be an extraordinary moment. What are your hopes at this point?

Teela Reid: I hope that people are willing to step up and be engaged and make informed choices for themselves in a conversation that should absolutely be based on the facts and not one in which we should be enlivening racism or anything like that. I do believe it’ll pass. I think there is so much goodwill in the Australian community.

If you look at history, the most successful referendum in 1967, shows that Australians actually feel very deeply on this issue. I’ve travelled to lots of different parts of the country, and engaged with fence seaters or people who want to protest to these kinds of conversations. By the end of it, you sit down, you listen, you work through these conversations and people’s hearts really get it.

Dr Simon Longstaff: Is this a beginning of a new set of possibilities in this country?

Teela Reid: I do believe it is. We all know the Uluru Statement has called for a First Nation’s Voice. One of the things I am grappling with both in the legal sense and the moral sense, it’s the enormous compromise our people have to make decade after decade after decade for this nation to just have a breakthrough. It happened with land rights. The Barunga Statement was gifted to Hawke. Hawke promised a treaty, he gave the nation reconciliation. It’s probably why we’re three, four decades behind right now. I don’t think that Prime Ministers like Hawke should be revered for what they’ve done. Even around when Whitlam came in for his short time in power, there were decades of activism and movements that were demanding big things, big changes. And it was only because of that activism that within those three, four years there was able to be this watershed moment of legislation and changes.

One of the things I am grappling with both in the legal sense and the moral sense, it’s the enormous compromise our people have to make decade after decade after decade for this nation to just have a breakthrough.

And so here I am thinking now, there’s another compromise being made. Perhaps this is more my moment of having to grapple with the way in which compromises are made in the political space.

I hope that everyday Australians are able to take this opportunity this year to actually reflect and educate themselves on the bigger picture and part of the story to this. Because we’re only really seeing it through that one little kind of myopic lens now that there’s going to be one ballot box and you’re going to be voting yes or no. But there is so much more to this.

Simon Longstaff: Are you optimistic that people understand this? Can we resolve the question of legitimacy?

Teela Reid: I do believe it’ll pass, yes. I think there’s so much good faith and goodwill in the people. The strategy behind this movement is correct. Going to the people and not the politicians is what changed this nation. At every single turning point the only reason it’s on the national agenda is because of everyday Australians. It won’t be easy. I think that people shouldn’t get complacent about where we are now. Between now and the ballot box, every single one of you is going to have start your own campaign. Take this extremely seriously. For someone like me, it doesn’t stop.

For everything you need to know about the Voice to Parliament visit here.

This is an abridged version of In Conversation with Teela Reid. Watch the full discussion below.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Politics + Human Rights

How to have a difficult conversation about war

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAY 2023

We’re thrilled to announce we’ve appointed Dr Gwilym David Blunt as an Ethics Centre Fellow.

A writer and commentator on global politics and philosophy, David has spent time as a Senior Lecturer in International Politics at City, University of London and as a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Cambridge. Now based in Australia, David has published numerous books, appeared on ABC The Drum and Monocle Daily, and has written for The Conversation, ABC and International Affairs.

To welcome him, we sat down with David to discuss the important role ethics can play when it comes to politics, human rights and philanthropy.

What attracts you to the field of philosophy?

We are often told to ‘go with your gut’ when making decisions. This has always struck me as genuinely terrible advice. Our instincts can be conditioned by any number of prejudices or misconceptions. Philosophy is a way of interrogating these instincts and thinking systematically about hard questions.

How does your background in international politics and human rights shape your approach to philosophy and ethics?

International politics fascinates me because it is often treated as a place where ethics don’t apply. It’s seen as a place in which raw power determines the norms that govern politics, something that few would say is acceptable in domestic politics. Yet, this seems ridiculous.

Take the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many people around the world reacted in horror because wars of aggression are wrong. This is more than an intuition. Self-determination is grounded in an ethical judgement that people have a right to determine their collective destiny without interference. We might question the scope of this right, but most people will agree that at the very minimum it prohibits wars of aggression. There is clearly a place for ethics in world politics.

In fact it is more than a place, there is an urgency for ethics in world politics. The Covid-19 pandemic clearly showed how humanity as a whole faces shared challenges. The viruses that cause pandemics and the greenhouse gases that cause climate change don’t respect the arbitrary lines we draw on maps. We cannot hide behind closed borders and hope it all just goes away. These threats raise ethical questions about duties and responsibilities, where burdens lie, and what we owe to the future.

What kind of work will you be engaging with at The Ethics Centre?

The Ethics Centre is hosting me while I work on my next book which is on philanthropy. This is a topic that I’ve been interested in for a long time, but was on the side burner until the pandemic brought it back into focus. My work usually looks at the grimmer aspects of political philosophy, such as war, terrorism, and extreme inequality. So, it is nice to be working on something that gives some reasons to be hopeful about humanity. Although philanthropy raises a lot of interesting questions about justice, reputation laundering, and fairness.

I’ll also be writing some articles and assisting as a media spokesperson.

Which philosopher has most impacted the way you think?

It’s difficult to pick one, but I think it would have to be Philip Pettit, who isn’t a household name, but, along with Quentin Skinner, revived republicanism in political philosophy, which is what grounds my work. Now, don’t confuse republicanism with Donald Trump or right-wing MAGA politics or even with anti-monarchism. Republicanism is at its core a philosophy of freedom; it’s central claim is no person can be free if they are under the arbitrary power of someone else.

You have also done a lot of research on poverty and the distribution of wealth. What role do you think philanthropy and charity has or should have in that space?

I like to compare philanthropy with the façade of a building. It is something that beautifies, but it isn’t necessary to create a stable and functional structure. To continue this analogy, the parts of a building that keep it up, foundations and reinforced concrete, these are the province of justice. My worry with philanthropy is that it is taking up those structural roles, that it is subverting the role of justice. This isn’t a trivial matter because philanthropy is often characterised by the arbitrary power that republicans tend to worry about. Access to healthcare or education should not rest on the whim of a wealthy person, even if they are a good person, these are things that all people are owed as matter of right.

Your recent book Global Poverty, Injustice and Resistance argues our right to politically resist. We’re currently seeing some extreme cases of human right infringements around the world – what’s an example of resistance you’ve noticed that seems to be having a significant effect?

Resistance is such an interesting subject, because it covers such a wide range of activities. Most people tend to think of revolutions or mass civil disobedience as the paradigm examples of resistance, but I find the less visible forms of resistance more compelling.

I think the best example is illegal or irregular immigration for socio-economic reasons. This topic is one that generates a lot of extreme feelings in wealthy states like Australia and the United States, which is why I find it interesting. People who flee extreme poverty are voting with their feet against our current global political system, where many people are denied a reasonably dignified human life simply because they were born in the wrong country.

Many people’s first instinct is to say that illegal immigrants are doing something wrong, because they are breaking the law, but this goes back to what I said that the beginning of this interview: our instincts can be wrong.

We need to seriously start asking questions about why people cross borders illegally. It takes a lot for someone to leave their home to go to a distant land where they might know no one, have to learn new customs and language, and there is a chance they might die in the journey. We need to think about our complicity with the economic systems that produce avoidable poverty and exacerbate climate change, the push factors for this sort of migration. My hope is that this may help to create systemic change.

What are you reading, watching or listening to at the moment?

For work, I’m finishing up reading Paul Vallely’s massive Philanthropy: From Aristotle to Zuckerberg which is a good accessible examination of philanthropy and re-reading Will MacAskill’s What We Owe the Future for a short piece I’m working on. And I’m also revisiting some of the greatest hits of republicanism from Pettit and Skinner for a new YouTube series I’m doing.

For pleasure, I’m reading Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, which is really amazingly written. She’s one of those people who makes me actively jealous of their wordcraft. And I’m reading my wife I, Claudius before bed.

Watching, we are doing a nostalgia trip and rewatching the X-Files, which is fun even if the last few seasons are pretty bad. The sad thing about watching it in 2023 is that fringy, conspiracy theory stuff was just fun entertainment 30 years ago and now it has turned extremely sinister, which kind of drains a bit of the joy out of it.

Listening, I’m a big Last Podcast on the Left fan, because sometimes I just need to learn about cults, aliens, cryptids, and true crime. And since moving to Australia I’ve been getting into Australian music and have been bingeing King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

Putting it simply, ethics is my ‘bullshit detector’; it helps me recognise my own bullshit, which keeps me from being complacent, and the bullshit of society at large, which seems to be really piling up.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why morality must evolve

LISTEN

Relationships, Society + Culture

Little Bad Thing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ethics of friendships: Are our values reflected in the people we spend time with?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Big thinkerClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 28 APR 2023

Committed to individualism and credited as the father of transcendentalism, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher and poet.

Initially on a path to follow his father’s footsteps and serve in the Christian ministry, Emerson attended Harvard’s Divinity School to become a pastor. But as time went on and he delved deeper into his religious studies, he realised an unignorable sense of detachment and divergence from the traditional religious values he was immersed in. And so he left the Second Unitarian Church and decided to forge his own path.

“To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.”

Emerson’s influential career began with public lectures in Boston that would inspire some of his most renowned essays and ideas. His lectures centred on human culture, English literature, biography and philosophy. He was known for popularising the major movement known as transcendentalism.

The Father of Transcendentalism

“Transcendental” was initially coined by philosopher Immanuel Kant in his theory of transcendental idealism. It’s a theory of perception that holds space and time, along with our five senses, are all subjective experiences and don’t exist outside of the human experience.

Even though Kant coined the term, Emerson is regarded as the father of transcendentalism.

Emerson’s transcendentalism, which became one of America’s first literature and philosophical movements, holds that we ought to be doubtful of knowledge we get from our five senses or even logic and reason; the only trustworthy source of knowledge manifests itself in our personal intuition and self-revelations.

In one of his first lectures, “The Uses of Natural History”, Emerson planted the initial seed for the movement when he explained science as something innately human. He emphasised nature to be an extension of one’s self: “the whole of Nature is a metaphor or image of the human mind.”

His book-length 1836 essay “Nature” is what officially and explicitly defined transcendentalism.

In essence, transcendentalists believe nature is paramount: all their ideals are rooted in the natural world. They believe all things are inherently good, humans and nature alike. In much the same way, transcendentalists see the divinity – the “God” – in everything and everyone. As Emerson wrote, “I am part or particle of God.” Transcendentalists also believe in the human potential for achieving greatness and genius.

Emerson is responsible for introducing a number of people to metaphysical concepts for the first time. A group he helped found in the late 1830’s called the Transcendental Club had dangerous conversations that critiqued societal institutions of the time, such as organised religion and slavery. Its members included prominent thinkers of the time, like Henry David Thoreau and Margaret Fuller, and allowed a space for transcendentalist ideas to grow.

Self-Reliance

As the title of one of his most famous essays, “Self-Reliance” describes one of his principal philosophies: relying solely on ourselves. Emerson’s transcendentalism has been equated to romantic individualism because of his emphasis on the self. For understanding and greatness, Emerson believed we ought only to rely on ourselves and trust our intuition. In fact, he believed the only thing separating the common person from “greatness” is that the “greats” have the gall to admit precisely what they’re feeling when they feel it. As humans, much of our experiences and emotions are shared, and Emerson saw beauty in such commonalities.

At the same time, he cited conformity as a major barrier to achieving greatness. He thought we should be comfortable and proud of being distinctly ourselves. He praised individuality and the pursuit of achieving “an original relation to the universe” by tuning inwards.

The key to unlocking genius is listening to what Emerson called our “creative insight”. He felt such insight was decidedly divine, God’s way of individually speaking to us. This insight is necessary for anyone to accomplish anything meaningful, and so Emerson encouraged everyone to trust their own creative insight over societal ones. Listening to our divinity, our creative insight, yields a life lived authentically.

“It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.”

It’s these transcendentalist ideologies that would eventually inspire philosopher Henry David Thoreau to reject society and go into the woods in order “to live deliberately and front only the essential facts of life”. And that same line of thinking is what inspired Christopher McCandless, an infamous American adventurer, to abandon family and escape to Fairbanks, Alaska in the 1990s. His story of living in the solitude of wilderness was later popularised in the film and novel Into the Wild.

Although some find wisdom and beauty in Emerson’s fierce admiration of solitude and complete rejection of groupthink, others see privilege in his ideals. Not everyone is able to exercise free will; not everyone can afford to stray from the norm and escape their social circumstances. And so to some, his ideas are lofty and unattainable, less you have the power of class and money on your side.

Beyond privilege, others see selfishness in his philosophies. By tuning inwards and considering only our own needs and desires, what is lost? What might we sacrifice when we neglect those around us? When we disregard even our loved ones? And yet, Emerson never said anything definitively:

“But it is the fault of our own rhetoric that we cannot strongly state one fact without seeming to belie some other. I hold our actual knowledge is very cheap.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Virtue Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment

Why it was wrong to kill Harambe

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships