People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Cris Parker 5 SEP 2023

Advancements in technology have shown greater efficiency and benefits for many. But if we don’t invest in human-centric thinking, we risk leaving our most vulnerable behind.

As businesses from the private and public sector continue to invest in improved digital processes, tools and services, we are seeing users empowered with greater information, accessibility and connectivity.

However as critical services for healthcare, lifestyle and support systems have become increasingly digitised, the barriers for vulnerable, remote or digitally excluded individuals must also be considered against these benefits.

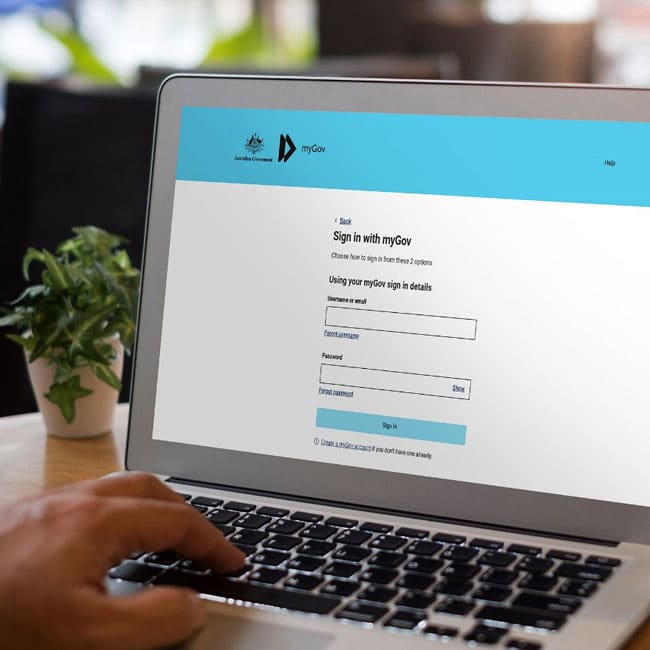

It’s no wonder the much-maligned MyGov app underwent an audit review earlier this year, resulting in a major overhaul of the service. Reading through their chat rooms and forums where customers can express their experiences, comments like these fill the pages:

“…If you’re trying to do something online, even if you’ve got a super reliable connection, you can spend hours wandering around in a fog because there’s no transparency about – they’re not trying to make it easy for people.”

“You need to have acquired the technology to do it, but you get on their websites, and I don’t know who designs their systems. But you’ve got to be psychic to be able to follow what they want. In order to get what you need, you’ve got to run through this maze, it’s complete bullshit.”

“And you’re already putting elderly people and keeping them in a home, it all goes online and digital, they stop having that outside interaction. It’s another chip away of community. That’s where the isolation comes in.”

Reading these statements, you get a sense of the frustration and confusion felt, not just due to time wasted but also the loss of a personal connection and agency. These experiences can lead users to doubt the reliability of business’ processes and chip away at the trust in their systems.

The Australian Digital Inclusion Index cites digital inclusion as “one of the most important challenges facing Australia.” Their 2023 key findings presented that digital inclusion remains closely linked to age and increases with education, employment and income.

So, as technology becomes more ubiquitous in our lives, how do we maintain human centric thinking? How do we avoid exacerbating existing inequalities while maintaining respect, autonomy and dignity for all?

Looking for some answers, I spoke to Jordan Hatch, a First Assistant Secretary at the Australian Government and someone who is passionate about designing for user needs. Hatch is currently working with the care and support economy task force in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, exploring some of the challenges and opportunities across the care sector.

Hatch is acutely aware that amidst this digital transformation, the welfare of vulnerable individuals remains a priority. He explains human-centered design principles must play a crucial role in shaping digital solutions. Importantly, understanding the user base, including different cohorts and their specific needs, is foundational to designing inclusive services. Extensive research and involvement of First Nations communities, individuals with low digital literacy, or limited internet access are also essential to developing solutions that address their unique challenges.

Hatch explains how technology is transforming the face-to-face experience. He says the digitisation of services has prompted a re-evaluation of the role of physical service centres. The integration of digital and in-person channels is allowing for streamlined processes and improved customer experiences.

A great example is Service NSW, which has become a centralised hub offering access to several support services. The availability of digital options has not led to the exclusion of those who prefer face-to-face interactions. On the contrary, it has allowed for a more comprehensive and improved service for individuals seeking in-person assistance. The digital transformation has become a means to augment the service experience, rather than replacing it. When visiting a Service NSW centre, you are met by a representative who directs you to a computer and, if required, walks you through the online process, offering personalised support. This evolution caters to diverse needs, ensuring that the face-to-face experience remains valuable while offering alternative modes of engagement.

Of course, increasing the capability and use of technology has its downside. Digital interactions have become a societal norm and an opportunity for scams. This has led to a number of digital hoops users are obliged to make in an attempt to protect their data and privacy. This process can impact the users’ wellbeing as passwords are lost or forgotten and the digital path is often confusing.

Hatch explains in this learning journey, how a shift in his perception occurred regarding the relationship between security and usability. Previously, it was believed that security and usability were at opposite ends of the spectrum—either systems were easy to use but lacked security, or they were secure but difficult to navigate. However, recent technological advancements have challenged this notion. Innovations emerged, offering enhanced security measures that were user-friendly. For example, modern password theories promoted the use of longer passphrases consisting of simple words, resulting in both stronger security and increased user-friendliness.

Technological transformation is a process and technology is not a panacea – it is a steppingstone and an opportunity for simplification and identifying unique solutions. What we can’t do is allow technology to overshadow the need to address regulation and the complexity it can create.

Hatch shares an insight from Edward Santos, the former Human Rights Commissioner to Australia: the prevalent mindset of the technology world being, “move fast and break things”. This is often seen as innovation, and an opportunity to learn from failure and adapt. However, in the realm of public service, where real people’s lives are at stake, the stakes are higher. The margin for error in this context can have tangible consequences for vulnerable individuals.

Slowing down is not necessarily the solution, particularly when you see or experience the harm caused by a misalignment between requirements and the capacity to meet them. It is the work Jordan Hatch describes where the issue is not when, but how services are designed and delivered that will make the difference.

The intersection between technology and policy creates an opportunity for regulators and digital experts to come together. Rather than digitise what exists, they can identify the unnecessary complexities and streamline the rules. This then creates a win-win situation – through the lens of human-centred design, it facilitates the digitisation process and creates a simpler regulatory framework for those who choose not to use a digital process.

With this approach we can design technology to work for us rather than against us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why you should care about where you keep your money

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

The ethics of drug injecting rooms

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to build a successful culture

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 1 SEP 2023

Fittingly, for a show set in the brutal, immediate environment of a commercial kitchen, The Bear opens with a brutal, immediate metaphor for grief.

In the opening scene of the show, Carmy (Jeremy Allen White) traverses a bridge in the middle of the night. We know nothing of this man yet. He moves fearfully, slowly. And in a moment, we see why – there’s a vicious bear across from him, reared up and snarling, and Carmy is desperately, fearfully trying to placate it.

Within an episode, the symbolism is obvious. The bridge represents what we will soon come to see as an uncomfortable, dangerous transition Carmy has been thrust into – he has left behind a world of chef superstardom, in order to take over ownership of the middling sandwich shop left to him after the suicide of his brother. And the bear? It is the manifestation of the grief he has been left with; this terrible, unpredictable thing, that he has no idea how to confront, or how to contain.

On its surface, The Bear is about kitchen life. It nails perfectly the stress; the heat; the ugly mechanics of what goes into our food. Anthony Bourdain was right – when you eat out, and get served a dish on a perfectly clean plate, what you haven’t seen is the often literal blood, sweat, and tears that produces it. The Bear spends its two seasons documenting those bodily fluids in sometimes gratuitous detail.

But as its opening scene establishes, what The Bear is really about is untethering. More specifically, the way that grief untethers – the way it throws us back into a world we thought we knew but is now suddenly unfamiliar to us, as we stand under its hot kitchen lights, naked and afraid.

What grief does to us

Carmy is a man with his own dark past. In flashbacks, we see him abused by kitchen bosses. We learn more about Michael, his dead brother, who struggled with addiction. And, drip by drip, we learn about the family dynamics and pressures that made Michael both who he was, and who he died as, and who Carmy once was.

What we also learn is the way that grief can provide a sort of brutal reset of personhood. When we lose someone close to us – whether it be a family member, as in the case of Carmy, or a lover, or a friend – we speak often of losing something of ourselves too.

This cuts to the beauty of human interaction – something that the philosopher Derek Parfit often wrote about. Love, be it familial, platonic, or romantic, erodes the boundaries between the self and other. Our natural inclination as humans to learn about each other, to take on the cares and emotional states of those close to us, to constantly empathise and put ourselves in other’s shoes, makes us less like distinct individual entities, and more like what the philosopher Anette Baier once called “heirs and successors to those that we care about.”

This is beautiful, yes, but it also makes us deeply vulnerable. It means that death and suicide doesn’t just have the power to remove one human being from the world. It means that death and suicide has the power to remove part of us as well.

The philosopher Bryanna Moore has written about this in her paper ‘The Three Moral Dimensions of Grief.’ Moore understands human beings as relationally defined. She takes a sort of refined, tweak “no self” view of personal identity. On her reading, we are not hermetically sealed entities, with some stable, unchanging identity. We are who we are because of who we love, hate, and spend time with.

So for Moore, grief “reveals something vital about the way in which we relate to ourselves around us.” When Carmy loses Michael, he is forced into what Moore calls “a powerful reassessment and reevaluation of the self’s relation to the world.” This explains in great part why Carmy decides to take on Michael’s restaurant. It’s not just guilt that makes him want to help the brother who he could not help in life. It’s that he now no longer knows who he is. He is fresh and untethered. There is a gap, where Michael once was, but there’s also a gap where Carmy once was.

The moral value of grief

Robert C. Soloman, another philosopher who has written extensively about grief, argues in tandem with Moore that grief’s power to untether us makes it, to some extent, “morally excellent.” Soloman starts with the idea that grief is morally obligatory. As in, if someone we care about dies, and we do not grieve, then we have done something immoral – we have failed in some way. Grief is a necessity; it isn’t just some replacement of the love we once felt towards the departed, it is that love, taking on a new form.

For Soloman, the excellence comes from the way that grief represents an “emotional process.” It’s not just a feeling, a discrete emotional state that comes over us. It’s something that builds, grows and changes. This, we quickly find, is true with Carmy. We see him move constantly through different stages and states of grief, at times anger, at other times remorseful; always on the move, and always finding himself plunged into new emotions.

As to what kind of process grief is, it’s one of reconstruction. When we are untethered by loss, we are then forced to get to work on rebuilding ourselves. Grief heightens and sharpens us, makes us present in activities and choices. Carmy finds himself suddenly lit up by chefing in a way that he has not been before, dealing with the chaos of his new restaurant, but immersed in it, and learning new things about himself as a result.

It’s Moore who points out that rebuilding oneself need not always be positive, or moral. After all, there are many people who respond to traumatic events by becoming a new type of person, but a worse one – meaner, angrier, less forgiving. Grief gives us a blank slate, and it’s up to us what we then build on top of that slate.

The goodness of grief, then, comes from the way that it makes us present; intentional. So often we move through life making choices passively; letting things happen to us. When we are left with nothing, and we must rebuild, every choice becomes heightened – we become aware of them, in a way that we were not before.

Grief can wake us up from a stupor, shake us out of immoral patterns that we did not even realise that we had fallen into.

This, we see, happen with Carmy. Slowly, sure. He makes mistakes. He hurts others. He fails. But he is, after his hard reset, aware. Paradoxically – beautifully – a death has made him, quite to his surprise, suddenly and thrillingly alive. In that way, Michael’s passing wasn’t just a loss. It was, against the odds, a gift. And there is beauty in the way that Carmy takes it in his pale, open hands.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Will I, won’t I? How to sort out a large inheritance

WATCH

Relationships

Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Luara Ferracioli 17 AUG 2023

A liberal society like Australia should recognise that many intimate relationships matter, and in its approach to immigration the federal government should try as much as possible not to prioritise some relationships over others — unless it has a very good rationale for doing so.

A recent report by the Scanlon Foundation has shed some important light on how the current family migration scheme in Australia is failing foreign-born citizens, permanent residents, and their adult parents who want to join them in Australia.

According to the report, there are almost 140,000 Australian residents waiting between 12 and 40 years to be permanently reunited with their parents. The best route is to fork over $48,365 per parent. This contributory visa currently has an expected processing period of 12 years. The cheaper, non-contributory version of this visa costs $4,990 per parent and the application may take 29 years to process.

Since the Parkinson review into Australia’s migration system was established in September 2022, much of the public commentary has focused on the unfairness of leaving adult citizens and their parents in limbo. The expert panel itself puts it bluntly: “Providing an opportunity for people to apply for a visa that will probably never come seems both cruel and unnecessary.”

There is no doubt that the government urgently needs to reform its approach to migration, and visas need to be processed within a reasonable time-frame so that prospective immigrants can move on with their lives. There are, however, two other unfair elements baked into the Australian family migration system that also need addressing.

First, there is the cost of the contributory visas. A visa of almost $50,000 only allows affluent foreign-born citizens to bring their parents to Australia. But if this visa is meant to promote the interest we all have in enjoying territorially located intimate relationships in an on-going fashion, then it is grossly unjust that the wealthy are given a much better shot at having that interest protected.

The second unfairness is perhaps even more under-appreciated. Why prioritise parents as opposed to other adults that citizens and permanent residents might care deeply about? Whereas some are no doubt very close to their parents, others are very close to an uncle, an aunt, or a third-degree cousin. Whereas some individuals long to spend more quality time with a parent, others would really like to live closer to their best friend.

This point becomes clearer when we recognise that sometimes friends are much more emotionally dependent on one another than immediate family members. A citizen who would genuinely lead a much better life if her best friend was allowed to move to Australia then lacks access to a visa that allows a fellow citizen to bring an adult parent into the country, irrespective of how emotionally close they are.

My point is not that the government should assess the level of intimacy between an adult citizen or permanent resident and a parent.

As a liberal society, we need to respect people’s right to privacy, and be extremely careful not to give bureaucrats power to pass judgements about people’s lives in ways that are prone to be informed by sexist, racist, and classist biases.

My point is only that, in a liberal society like Australia, many intimate relationships matter, and the government should try as much as possible not to prioritise some relationships over others unless it has a very good rationale for doing so. Ultimately it was this important requirement that saw many commentators object to Victorian premier Dan Andrews’s exclusion of friends from the remit of the COVID bubble in 2020, and why at some point the state of Victoria pivoted to allowing friends to visit each other during lockdown.

A fair alternative to an unfair immigration system?

But short of completely opening our international borders, is there a solution available to the Australian government? As I see it, the federal government can have a broader intimate relationship visa that is available to all citizens and permanent residents at a reasonable fee. Because the number of interested parties will be very high, the government can then combine that visa with a lottery scheme that gives every adult citizen and permanent resident an equal chance to bring someone they care deeply about to Australia.

In response to suggestions that a lottery scheme should be taken seriously, the author of the Scanlon report writes:

“Just like the faint hope that visa processing times will be faster than anticipated, the slim chance of winning a spot in the lottery will leave families banking on dreams, rather than adjusting to the realities of their situation and fully settling in Australia.”

As someone who has parents overseas, I don’t see why this would leave me “banking on dreams”. We all understand how lotteries work, and we all understand that when everyone has an equal interest in accessing a good or opportunity — in this case, reunification with a loved one — but that good or opportunity cannot be provided to everyone, a lottery may be the only fair way to go about it.

Australians have no appetite for open borders, so we need to come up with a fair way to run our migration schemes. In a world full of refugees whose lives are at risk, it is hard to show that an injustice has taken place when adult citizens are prevented from bringing a parent to Australia. At the same time, if some parents will be allowed to join their adult children in Australia on a permanent basis, we better have a fair system that gives all citizens and permanent residents an equal chance to reunite with someone they care deeply about.

This article was originally published by ABC Religion & Ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Respect

BY Dr Luara Ferracioli

Luara Ferracioli is Associate Professor in Political Philosophy at the University of Sydney and ARC DECRA fellow. She was awarded her PhD from the Australian National University in 2013, and has held appointments at the University of Oxford, Princeton University, and the University of Amsterdam. Her first book Liberal Self-Determination in a World of Migration was published in 2022 with Oxford University Press, and her new book Parenting and the Goods of Childhood is forthcoming (with Oxford University Press).

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

Imagine a large, cosmopolitan city, where people from uncountable backgrounds and with numerous beliefs all thrive together. People embrace different cultural traditions, speak varying languages, enjoy countless cuisines, and educate their children on diverse histories and practices.

This is the kind of pluralism that most people are familiar with, but a diverse and culturally integrated area like this is specifically an example of cultural pluralism.

Pluralism in a general sense says there can be multiple perspectives or truths that exist simultaneously, even if some of those perspectives are contradictory. It’s contrasted with monism, which says only one kind of thing exists; dualism, which says there are only two kinds of things (for example, mind and body); and nihilism, which says that no things exist.

So, while pluralism more broadly refers to a diversity of views, perspectives or truths, cultural pluralism refers specifically to a diversity of cultures that co-exist – ideally harmoniously and constructively – while maintaining their unique cultural identities.

Sometimes an entire country can be considered culturally pluralistic, and in other places there may be culturally pluralistic hubs (like states or suburbs where there is a thriving multicultural community within a larger more broadly homogenous area).

On the other end of the spectrum is cultural monism, the idea that a certain area or population should have only one culture. Culturally monistic places (for example, Japan or North Korea) rely on an implicit or explicit pressure for others to assimilate. Whereas assimilation involves the homogenisation of culture, pluralism encourages diversity, often embracing people of different ethnic groups, backgrounds, religions, practices and beliefs to come together and share in their differences.

A pluralistic society is more welcoming and supportive of minority cultures because people don’t feel pressured to hide or change their identities. Instead, diverse experiences are recognised as opportunities for learning and celebration. This invites travel and immigration, and translates into better mental health for migrants, the promotion of harmony and acceptance of others, and enhances creativity by exposing people to perspectives and experiences outside of their usual remit.

We also know what the alternative is in many cases. Australia has a dark history of assimilation practices, a symptom of racist, colonial perspectives that saw the decimation of First Nations people and their cultures. Cultural pluralism is one response to this sort of cultural domination that has been damaging throughout history and remains so in many places today.

However, there are plenty of ethical complications that arise in the pursuit of cultural plurality.

For example, sociologist Robert D. Putnam published research in 2007 that spoke about negative short-medium term effects of ethnically diverse neighbourhoods. He found that, on average, trust, altruism and community cooperation was lower in these neighbourhoods, even between those of the same or similar ethnicities.

While Putnam denied that his findings were anti-multicultural, and argues that there are several positive long-term effects of diverse societies, the research does indicate some of the risks associated with cultural pluralism. It can take a large amount of effort and social infrastructure to build and maintain diverse communities, and if this fails or is done poorly it can cause fragmentation of cultural communities.

This also accords with an argument made by journalist David Goodhart, that says people are generally divided into “Anywheres” (people with a mobile identity) and “Somewheres” (people, usually outside of urban areas, who have marginalised, long-term, location-based identities). This incongruity, he says, accounts for things like Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, because they speak to the Somewheres who are threatened by changes to their status quo. Pluralism, Goodhart notes, risks overlooking the discomfort these communities face if they are not properly supported and informed.

Other issues with pluralism include the prioritisation of competing cultural values and traditions. What if one person’s culture is fundamentally intolerant of another person’s culture? This is something we see especially with cultures organised around or heavily influenced by religion. For example, Christianity and Islam are often at odds with many different cultures around issues of sexual preference and gendered rights and responsibilities.

If we are to imagine a truly culturally pluralistic society, how do we ethically integrate people who are intolerant of others?

Pluralism as a cultural ideal also has direct implications for things like politics and law, raising the age-old question about the relationship between morality and the law. If we want a pluralistic society generally, how do the variations in beliefs, values and principles translate into law? Is it better to have a centralised legal system or do we want a legal plurality that reflects the diversity of the area?

This does already exist in some capacity – many countries have Islamic courts that enforce Sharia law for their communities in addition to the overarching governmental law. This parallel law-enforcement also exists in some colonised countries, where parts of Indigenous law have been recognised. For example, in Australia, with the Mabo decision.

Another feature of genuine cultural pluralism that has huge ethical implications and considerations is diversity of media. This is the idea that there should be (that is, a media system that is not monopolised) and diverse representation in media (that is, media that presents varying perspectives and analyses).

Firstly, this ensures that media, especially news media, stays accountable through comparison and competition, rather than a select powerful few being able to widely disseminate their opinions unchecked. Secondly, it fosters a greater sense of understanding and acceptance by exposing people to perspectives, experiences and opinions that they might otherwise be ignorant or reflexively wary of. Thirdly, as a result, it reduces the risk that media, as a powerful disseminator of culture, could end up creating or reinforcing a monoculture.

While cultural pluralism is often seen as an obviously good thing in western liberal societies, it isn’t without substantial challenges. In the pursuit of tolerance, acceptance and harmony, we must be wary of fragmenting cultures and ensure that diverse communities have adequate social supports to thrive.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is existentialism due for a comeback?

Today feels eerily like the age that spawned the philosophy of radical freedom in defiance of the absurdity of life. Perhaps it’s time for a revival.

Parenting during the Covid-19 pandemic involved many new and unwelcome challenges. Some were obvious, practical things, like having the whole family suddenly working and learning under one roof, and the disruptions caused by lockdowns, isolation, and being physically cut off from extended family and friends.

But there were also what we might call the more existential challenges, the ones that engaged deeper questions of what to do in the face of radical uncertainty, absurdity and death. Words like “unprecedented” barely cover how shockingly the contingency of our social, economic and even physical lives were suddenly exposed. For me, one of the most confronting moments early in the pandemic was having my worried children ask me what was going to happen, and not being able to tell them. Feeling powerless and inadequate, all I could do was mumble something about it all being alright in the end, somehow.

I’m not sure how I did as a parent, but as a philosopher, this was a dismal failure on my part. After all, I’d been training for this moment since I was barely an adult myself. Like surprisingly many academic philosophers, I was sucked into philosophy via an undergraduate course on existentialism, and I’d been marinating in the ideas of Søren Kierkegaard in particular, but also figures like Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Albert Camus, ever since. These thinkers had described better than anyone such moments of confrontation with our fragility in the face of an uncaring universe. Yet when “the stage sets collapse”, as Camus put it, I had no great insight to share beyond forced optimism.

In fairness, the existentialists themselves weren’t great at giving advice to young people either. During World War II, Sartre was approached by a young pupil wrestling with whether to stay and look after his mother or join the army to fight for France. Sartre’s advice in reply was “You are free, therefore choose” – classic Sartre, in that it’s both stirringly dramatic and practically useless. But then, that’s all Sartre really could say, given his commitment to the unavoidability of radical choice.

Besides, existentialism itself seems to have fallen out of style. For decades, fiction from The Catcher in the Rye through to Fight Club would valorise a certain kind of existential hero: someone who stood up against mindless conformity, exerting a freedom that others – the unthinking masses that Heidegger derisively called das Man, ‘the They’ – didn’t even realise they had.

These days, however, that sort of hero seems passé. We still tell stories of people rejecting inauthentic social messages and asserting their freedom, but of an altogether darker sort; think Joaquin Phoenix’s take on the Joker, for example. Instead of existentialist heroes, we’ve got nihilists.

I can understand why nihilism staged a comeback. In her classic existentialist manifesto, The Ethics of Ambiguity, Simone de Beauvoir tells us that “Nihilism is disappointed seriousness which has turned in upon itself.” For some time now, the 2020s have started to feel an awful lot like the 1920s: worldwide epidemic disease, rampant inflation and rising fascism. The future that was promised to us in the 1990s, one of ever-increasing economic prosperity and global peace (what Francis Fukuyama famously called the “end of history”) never arrived. That’s enough to disappoint anyone’s seriousness. Throw in the seemingly intractable threat of climate change, and the future becomes a source of inescapable dread.

But then, that is precisely the sort of context in which existentialism found its moment, in the crucible of occupation and global war. At its worst, existentialism can read like naïve adolescent posturing, the sort of all-or-nothing philosophy you can only believe in until you’ve experienced the true limits of your freedom.

At its best, though, existentialism was a defiant reassertion of human dignity in the face of absurdity and hopelessness. As we hurtle into planetary system-collapse and growing inequality and authoritarianism, maybe a new existentialism is precisely what we need.

Thankfully, then, not all the existential heroes went away.

Seeking redemption

During lockdowns, after the kids had gone to bed, I’d often retreat to the TV to immerse myself in Rockstar Games’ epic open-world first-person shooter Red Dead Redemption II. The game is both achingly beautiful and narratively rich, and it’s hard not to become emotionally invested in your character: the morally conflicted, laconic Arthur Morgan, an enforcer for the fugitive Van Der Linde gang in the twilight of the Old West. [Spoiler ahead.]

That’s why it’s such a gut-punch when, about two-thirds of the way through the game, Arthur learns he’s dying of tuberculosis. It feels like the game-makers have cheated you somehow. Game characters aren’t meant to die, at least not like this and not for good. Yet this is also one of those bracing moments of existential confrontation with reality. Kierkegaard spoke of the “certain-uncertainty” of death: we know we will die, but we do not know how or when. Suddenly, this certain-uncertainty suffuses the game-world, as your every task becomes one of your last. The significance of every decision feels amplified.

Arthur, in the end, grasps his moment. He commits himself to his task and sets out to right wrongs, willingly setting out to a final showdown he knows that, one way or another, he will not survive. It’s a long way from nihilism, and in ‘unprecedented’ times, it was exactly the existentialist tonic this philosopher needed.

We are, for good or ill, ‘living with Covid’ now. But the other challenges of our historical moment are only becoming more urgent. Eighty years ago, writing in his moment of oppression and despair, Sartre declared that if we don’t run away, then we’ve chosen the war. Outside of the Martian escape fantasies of billionaires, there is nowhere for us, now, to run. So perhaps the existentialists were right: we need to face uncomfortable truths, and stand and fight.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Nihilism

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

BY Pat Stokes

Dr Patrick Stokes is a senior lecturer in Philosophy at Deakin University. Follow him on Twitter – @patstokes.

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 9 AUG 2023

If we are to engage with the ethical complexity of the world, we need to learn how to hold two contradictory judgements in our mind at the same time.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

– Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

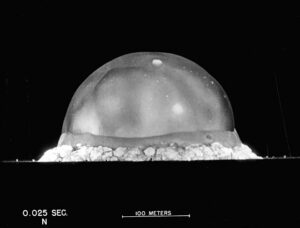

A fraction of a second after the first atomic bomb was detonated in New Mexico in 1945, a dense blob of superheated gas with a temperature of over 20,000 degrees expanded to a diameter of 250 metres, casting a light brighter than the sun and illuminating the surrounding valley as if it were daytime. We know what the atomic blast looked like at this nascent moment because there is a black and white photograph of it, taken using a specialised high-speed camera developed just for this test.

I vividly remember seeing this photo for the first time in a school library book. I spent long stretches contemplating the otherworldly beauty of the glowing sphere, marvelling at the fundamental physical forces on display, awed and diminished by their power. Yet I was also deeply troubled by what the image represented: a weapon designed for indiscriminate killing and the precursor to the device dropped on Nagasaki, taking over 200,000 lives – most civilians.

I’m not the only one to have mixed feelings about the atomic test. The “father” of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer – the subject of the new Christopher Nolan film – expressed pride at the accomplishment of his team in developing a weapon that could end a devastating war, but he also experienced tremendous guilt at starting an arms race that could end humanity itself. He reportedly told the U.S. President Harry S. Truman that his involvement in developing the atomic bomb left him feeling like he had blood on his hands.

In expressing this, Oppenheimer was displaying ethical ambivalence, where he held two opposing views at the same time. Today, we might regard Oppenheimer and his legacy with similar ambivalence.

This is not necessarily an easy thing to do; our minds often race to collapse ambivalence into certainty, into clean black and white. But it’s also an important ethical skill to develop if we’re to engage with the complexities of a world rendered in shades of grey.

In all things good, in all things bad

It’s rare that we come across someone or something that is entirely good or entirely bad. Fossil fuels have lit the darkness and fended off the cold of winter, but they also contribute to destabilising the world’s climate. Natural disasters can cause untold damage and suffering, but they can also awaken the charity and compassion within a community. And many of those who have offered the greatest contributions to art, culture or science have also harboured hidden vices, such as maintaining abusive relationships in private.

When confronted by these conflicted cases, we often enter a state of cognitive dissonance. Contemplating the virtues and vices of fossil fuels at the same time, or appreciating the art of Pablo Picasso while being aware of his relationship towards women, is akin to looking at the word “red” written in blue ink. Our minds recoil from the contradiction and race to collapse it into a singular judgement: good or bad.

But in our rush to escape the discomfort of dissonance, we can cut ourselves off from the full ethical picture. If we settle only on the bad then we risk missing out on much that is good, beautiful or enriching. The paintings of Picasso still retain their artistic virtues despite our opinion of its creator. Yet if we settle only on the good, then we risk excusing much that is bad. Just because we appreciate Picasso’s portraits doesn’t mean we should endorse his treatment of women, even if his relationships with those women informed his art.

Ambivalence doesn’t mean withholding judgement; we can still decide that the balance falls clearly on one side or the other. But even if we do judge something as being overall bad, we can still appreciate the good in it.

The key is to learn how to appreciate without endorsement. Indeed, how to appreciate and condemn simultaneously.

This might change the way we represent some historical figures. If we want to acknowledge both the accomplishments and the colonial consequences of figures like James Cook, that might mean doing so in a museum rather than erecting statues, which by their nature are unambiguous artifacts intended to elevate an individual in the public eye.

Despite our minds yearning to collapse the discomfort of ambivalence into certainty, if we are to engage with the full ethical complexity of world and other people, then we need to be willing to embrace good and bad simultaneously and with nuance, even if that means holding contradictory attitudes at the same time.

So, while I remain committed to the view that nuclear weapons represent an unacceptable threat to the future of humanity, I still appreciate the beauty of that photo of the first atomic test. It does feel contradictory to hold these two views simultaneously. Very well, I contradict myself. I, like every facet of reality, contain multitudes.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Barbie and what it means to be human

Barbie and what it means to be human

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 7 AUG 2023

It was with a measure of apprehension that I recently travelled to the cinema to watch Greta Gerwig’s Barbie.

I was conscious of being an atypical audience member – with most skewing younger, female and adorned in pink (I missed out on all three criteria). However, having read some reviews (both complimentary and critical) I was expecting a full-scale assault on the ‘patriarchy’ – to which, on appearances alone, I could be said to belong.

Warning: This article contains spoilers for the film Barbie

However, Gerwig’s film is far more interesting. Not only is it not a critique of patriarchy as a singular evil, but it raises deep questions about what it means to be human (whatever your sex or gender identity). And it does this all with its tongue firmly planted in the proverbial cheek; laughing not only at the usual stereotypes but, along the way, at itself.

The first indication that this film intends to subvert all stereotypes comes in the opening sequence – an homage to the beginning of Stanley Kubrick’s iconic film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Rather than encountering a giant black ‘obelisk’ that reorients the history of humankind, a group of young girls wake to find a giant Margot Robbie looming over them in the form of ‘Stereotypical Barbie’. Until that time, the girls have been restricted to playing with baby dolls and learning the stereotypical roles allotted to women in a male-dominated world.

What happens next is instructive. Rather than simply putting aside the baby dolls in favour of the new adult form represented by Barbie, the girls embark on a savage work of destruction. They dismember the baby dolls, crush their skulls, grind them into the dirt. This is not a gentle awakening into something that is more ‘pure’ than what came before. From the outset, we are offered an image of humanity that is not one in which the divide between ‘good’ and ‘bad’, ‘dominant’ and submissive’, ‘peaceful’ and ‘violent’ is neatly allocated in favour of one sex or another. Rather, virtues and vices are shown to be evenly distributed across humanity in all its variety.

That the violent behaviour of the little girls is not an aberration is made clear later in the film when we are introduced to ‘Weird Barbie’. She lives on the margins of ‘Barbieland’ – both an outcast and a healer – whose status has been defined by her broken (imperfect) condition. The damage done to ‘Weird Barbie’ is, again, due to mistreatment by a subset of girls who treat Barbie in the same way depicted in the opening scenes. Then there is ‘Barbieland’ itself – a place of apparent perfection … unless you happen to be a ‘Ken’. Here, the ‘Patriarchy’ has been replaced by a ‘Matriarchy’ that is invested with all of the flaws of its male counterpart.

In Barbieland, Kens have no status of their own. Rather, they are mere cyphers – decorative extensions of the Barbies whom they adorn. For the most part, they are frustrated by, but ultimately accepting of, their status. The conceit of the film is an obvious one: Barbieland is the mirror image of the ‘real world,’ where patriarchy reigns supreme. Indeed, the Barbies (in all their brilliant variety) believe that their exemplary society has changed the real world for the better, liberating women and girls from all male oppression.

Alas, the real world is not so obliging – as is soon discovered when the two worlds intersect. There, Stereotypical Barbie (suffering from a bad case of flat feet) and Stereotypical Ken are exposed to the radically imperfect society that is the product of male domination. Much of what they find should be familiar to us. The film does a brilliant job of lampooning what we might take for granted. Even the character of male-dominated big business comes in for a delightful serve. The target is Mattel (which must be commended for its willingness to allow itself to be exposed to ridicule – even in fictional form).

Unfortunately, Ken (played by Ryan Gosling) learns all the wrong lessons. Infected by the ideology of Patriarchy (which he associates with male dominance and horse riding) he returns to Barbieland to ‘liberate’ the Kens. The contagion spreads – reversing the natural order; turning the ‘Barbies’ into female versions of the Kens of old.

Fortunately, all is eventually made right when Margot Robbie’s character, with a mother and daughter in tow, returns to save the day.

But the reason the film struck such a chord with me, is because it raises deeper questions about what it means to be human.

It is Stereotypical Barbie who finally liberates Stereotypical Ken by leading him to realise that his own value exists independent of any relationship to her. Having done so, Barbie then decides to abandon the life of a doll to become fully human. However, before being granted this wish by her creator (in reality, a talented designer and businesswoman of somewhat questionable integrity) she is first made to experience what the choice to be human entails. This requires Barbie to live through the whole gamut of emotions – all that comes from the delirious wonder of human life – as well as its terrors, tragedies and abiding disappointments.

This is where the film becomes profound.

How many of us consciously embrace our humanity – and all of the implications of doing so? How many of us wonder about what it takes to become fully human? Gerwig implies that far fewer of us do so than we might hope.

Instead, too many of us live the life of the dolls – no matter what world we live in. We are content to exist within the confines of a box; to not think or feel too deeply, to not have our lives become more complicated as when happens when the rules and conventions – the morality – of the crowd is called into question by our own wondering.

Don’t be put off by the marketing puffery; with or without the pink, this is a film worth seeing. Don’t believe the gripes of ‘anti-woke’, conservative commentators. They attack a phantom of their own imagining. This film is aware without being prescriptive. It is fair. It is clever. It is subtle. It is funny. It never takes itself too seriously. It is everything that the parody of ‘woke’ is not.

It is ultimately an invitation to engage in serious reflection about whether or not to be fully human – with all that entails. It is an invitation that Barbie accepts – and so should we.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Send in the clowns: The ethics of comedy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

Explainer, READ

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Tyson Yunkaporta

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 7 AUG 2023

“I have blood on my hands.” This is what Robert Oppenheimer, the mastermind behind the Manhattan Project, told US President Harry Truman after the bombs he created were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki killing over an estimated 226,000 people.

The President reassured him, but in private was incensed by the ‘cry-baby scientist’ for his guilty conscience and told Dean Acheson, his Secretary of State, “I don’t want to see that son of a bitch in this office ever again.”

With the anniversary of the bombings this week while Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer is in cinemas, it is a good moment to reflect on the two people most responsible for the creation and use of nuclear weapons: one wracked with guilt, the other with a clean conscience.

Who is right?

In his speech announcing the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Truman provided the base from which apologists sought to defend the use of nuclear weapons: it “shortened the agony of war.”

It is a theme developed by American academic Paul Fussell in his essay Thank God for the Atom Bomb. Fussell, a veteran of the European Theatre, defended the use of nuclear weapons because it spared the bloodshed and trauma of a conventional invasion of the Japanese home islands.

Military planners believed that this could have resulted in over a million causalities and hundreds of thousands of deaths of service personnel, to say nothing of the effect on Japanese civilians. In the lead up to the invasion the Americans minted half a million Purple Hearts, medals for those wounded in battle; this supply has lasted through every conflict since. We can see here the simple but compelling consequentialist reasoning: war is hell and anything that brings it to an end is worthwhile. Nuclear weapons, while terrible, saved lives.

The problem is that this argument rests on a false dichotomy. The Japanese government knew they had lost the war; weeks before the bombings the Emperor instructed his ministers to seek an end to the war via the good offices of the Soviet Union or another neutral state. There was a path to a negotiated peace. The Allies, however, wanted unconditional surrender.

We might ask whether this was a just war aim, but even if it was, there were alternatives: less indiscriminate aerial attacks and a naval blockade of war materials into Japan would have eventually compelled surrender. The point here isn’t to play at ‘armchair general’, but rather to recognise that the path to victory was never binary.

However, this reply is inadequate, because it doesn’t address the general question about the use of nuclear weapons, only the specific instance of their use in 1945. There is a bigger question: is it ever ethical to use nuclear weapons. The answer must be no.

Why?

Because, to paraphrase American philosopher Robert Nozick, people have rights and there are certain things that cannot be done to them without violating those rights. One such right must be against being murdered, because that is what the wrongful killing of a person is. It is murder. If we have these rights, then we must also be able to protect them and just as individuals can defend themselves so too can states as the guarantor of their citizen’s rights. This is a standard categorical check against the consequentialist reasoning of the military planners.

The horror of war is that it creates circumstances where ordinary ethical rules are suspended, where killing is not wrongful.

A soldier fighting in a war of self-defence may kill an enemy soldier to protect themselves and their country. However, this does not mean that all things are permitted. The targeting of non-combatants such as wounded soldiers, civilians, and especially children is not permitted, because they pose no threat.

We can draw an analogy with self-defence: if someone is trying to kill you and you kill them while defending yourself you have not done anything wrong, but if you deliberately killed a bystander to stop your attacker you have done something wrong because the bystander cannot be held responsible for the actions of your assailant.

It is a terrible reality that non-combatants die in war and sometimes it is excusable, but only when their deaths were not intended and all reasonable measures were taken to prevent them. Philosopher Michael Walzer calls this ‘double intention’; one must intend not to harm non-combatants as the primary element of your act and if it is likely that non-combatants will be collaterally harmed you must take due care to minimise the risks (even if it puts your soldiers at risk).

Hiroshima does not pass the double intention test. It is true that Hiroshima was a military target and therefore legitimate, but due care was not taken to ensure that civilians were not exposed to unnecessary harm. Nuclear weapons are simply too indiscriminate and their effects too terrible. There is almost no scenario for their use that does not include the foreseeable and avoidable deaths of non-combatants. They are designed to wipe out population centres, to kill non-combatants. At Hiroshima, for every soldier killed there were ten civilian deaths. Nuclear weapons have only become more powerful since then.

Returning to Oppenheimer and Truman, it is impossible not to feel that the former was in the right. Oppenheimer’s subsequent opposition to the development of more powerful nuclear weapons and support of non-proliferation, even at the cost of being targeted in the Red Scare, was a principled attempt to make amends for his contribution to the Manhattan Project.

The consequentialist argument that the use of nuclear weapons was justified because in shortening the war it saved lives and minimised human suffering can be very appealing, but it does not stand up to scrutiny. It rests on an oversimplified analysis of the options available to allied powers in August 1945; and, more importantly, it is an intrinsic part of the nature of nuclear weapons that their use deliberately and avoidably harms non-combatants.

If you are still unconvinced, imagine if the roles were reversed in 1945: one could easily say that Sydney or San Francisco were legitimate targets just like Hiroshima and Nagasaki. If the Japanese dropped an atomic bomb on Sydney Harbour on the grounds that it would have compelled Australia to surrender thereby ending the “agony of war”, would we view this as ethically justifiable or an atrocity to tally alongside the Rape of Nanking, the death camps of the Burma railroad, or the terrible human experiments conducted by Unit 731? It must be the latter, because otherwise no act, however terrible, can be prohibited and war truly becomes hell.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What does Adolescence tell us about identity?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

10 films to make you highbrow this summer

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Ukraine hacktivism

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

While the stories of Virginia Woolf are not traditionally considered as works of philosophy, her literature has a lot to teach us about self-identity, transformation, and our relationship to others.

“A million candles burnt in him without his being at the trouble of lighting a single one.” – Virginia Woolf, Orlando

Woolf was not a philosopher. She was not trained as such, nor did she assign the title to herself, and she did not produce work which follows traditional philosophical construction. However, her writing nonetheless stands as comprehensive, albeit unique, work of philosophy.

Woolf’s books, such as Orlando, The Waves, and Mrs Dalloway, are philosophical inquiries into ideas of the limits of the self and our capacity for transformation. At some point we all may feel a bit trapped in our own lives, worrying that we are not capable of making the changes needed to break free from routine, which in time has turned mundane.

Woolf’s characters and stories suggest that our own identities are endlessly transforming, whether we will them to or not.

More classical philosophers, like David Hume, explore similar questions in a more forthright manner. Also reflecting on matters of the stability of personal identity, Hume writes in his A Treatise of Human Nature:

“Our eyes cannot turn in their sockets without varying our perceptions. Our thought is still more variable than our sight; and all our other senses and faculties contribute to this change; nor is there any single power of the soul, which remains unalterably the same, perhaps for one moment. The mind is a kind of theatre…”

Woolf’s books make similar arguments. Rather than stating them in these explicit forms, she presents us with characters who depict the experience that Hume describes. Woolf’s surrealist story, Orlando, follows the long life of a man who one day awakens to find themselves a woman. Throughout we are made privy to the way the world and Orlando’s own mind alters as a result:

“Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than to merely keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world’s view of us.”

When Hume describes the mind as a theatre, he suggests there is no core part of ourselves that remains untouched by the inevitability of layered experience. We may be moved to change our fashion sense and, as a result, see the world treat us differently in response to this change. In turn, we are transformed, either knowingly or unknowingly, by whatever this new treatment may be.

Hume suggests that, while just as many different acts take place on a single stage, our personal identities also ebb and flow depending on whatever performance may be put before us at any given time. After all, the world does not merely pass us by; it speaks to us, and we remain entangled in conversation.

While Hume constructs this argument in a largely classical philosophical form, Woolf explores similar themes in her works through more experimental ways:

“A million candles burnt in him”, she writes in Orlando, “without his being at the trouble of lighting a single one.”

Using the gender transforming character of Orlando, Woolf examines identity, its multiplicity, and how, despite its being an embodied sensation, our sense of self both wavers and feels largely out of our control. In the novel, any complexities in Orlando’s change of gender are overshadowed by the multitude of other complexities in the many transformations that one embarks in life.

Throughout the book, readers are also given the opportunity to reflect on their own conceptions of self-identity. Do they also feel this ever-changing myriad of passions and selves within them? The character of Orlando allows readers to consider whether they also feel as though the world oftentimes presents itself unbidden, with force, shuffling the contents of their hearts and minds again and again. While Hume’s Treatise aims to convince us that who we are is constantly subject to change, Orlando gives readers the chance to spend time with a character actively embroiled in these changes.

A Room of One’s Own presents a collated series of Woolf’s essays which explore the topics of women and fiction. Though non-fictional, and evidently a work of critical theory, Woolf meditates on her own experience of acquiring a large, lifetime inheritance. She reflects on the ways in which her assured income not only materially transformed her capacities to pursue creative writing, but also how it radically transformed her perceptions of the individuals and social structures surrounding her:

“No force in the world can take from me my [monthly] five hundred pounds. Food, house and clothing are mine for ever. Therefore not merely do effort and labour cease, but also hatred and bitterness. I need not hate any man; he cannot hurt me. I need not flatter any man; he has nothing to give me. So imperceptibly I found myself adopting a new attitude towards the other half of the human race. It was absurd to blame any class or any sex, as a whole. Great bodies of people are never responsible for what they do. They are driven by instincts which are not within their control. They too, the patriarchs, the professors, had endless difficulties, terrible drawbacks to contend with.”

While Hume tells us, quite explicitly, about the fluidity of the self and of the mind’s susceptibility to its perceptual encounters, Woolf presents her readers with a personal instance of this very phenomenon. The acquisition of a stable income meant her thoughts about her world shifted. Woolf’s material security afforded her the freedom to choose how she interacts with those around her. Free from dependence, hatred and bitterness no longer preoccupied her mind, leaving space for empathy and understanding. The social world, which remained largely unchanged, began telling her a different story. With another candle lit, and the theatre of her mind changed, the perception of the world before her was also transformed, as was she.

If a philosopher is an individual who provokes their audiences to think in new ways, who poses both questions and ways in which those questions may be responded to, we can begin to see the philosophy of Virginia Woolf. Woolf’s personal philosophical style is one that does not set itself up for a battle of agreement or disagreement. Instead, it contemplates ideas in theatrical, enlivened forms which are seemingly more preoccupied with understanding and exploration rather than mere agreement.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Truth & Honesty

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to pick a good friend

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Come join the Circle of Chairs

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

What is all this content doing to us?

Three years ago, the eye-wateringly expensive television show See aired. Starring Jason Momoa, the budget for the show tapped out at around a million dollars per episode, a ludicrous amount of money even in today’s age.

As to what See is about – well, that’s not really worth discussing. Because chances are you haven’t seen it, and, in all likelihood, you’re not going to. What matters is that this was a massive piece of content that sank without a single trace. Ten years ago, a product like that would have been a big deal, no matter whether people liked it or not. It would have been, regardless of reception, an event. Instead, it’s one of a laundry list of shows that feel like they simply don’t exist.

This is what it means to be in the world of peak content. Every movie you loved as a kid is being rebooted; every franchise is being restarted; every actor you have even a passing interest in has their own four season long show.

But what is so much content doing to us? And how is it affecting the way we consider art?

The tyranny of choice

If you own a television, chances are you have found yourself parked in front of it, armed with the remote, at a complete loss as to what to watch. Not because your choices are limited. But because they are overwhelmingly large.

This is an example of what is known as “the tyranny of choice.” Many of us might believe that more choice is necessarily better for us. As the philosopher Renata Salecl outlines, if you have the ability to choose from three options, and one of them is taken away, most of us would assume we have been harmed in some way. That we’ve been made less free.

But the social scientists David G. Myers and Robert E. Lane have shown that an increase in choice tends to lead to a decrease in overall happiness. The psychologist Barry Schwartz has explained this through what he understands as our desire to “maximalise” – to get the best out of our decisions.

And yet trying to decide what the best decision will be takes time and effort. If we’re doing that constantly, forever in the process of trying to analyse what will be best for us, we will not only wear ourselves down – we’ll also compare the choice we made against the other potential choices we didn’t take. It’s a kind of agonising “grass is always greener” process, where our decision will always seem to be the lesser of those available.

The sea of content we swim in is therefore work. Choosing what to watch is labour. And we know, in our heart of hearts, that we probably could have chosen better – that there’s so much out there, that we’re bound to have made a mistake, and settled for good when we could have watched great.

The big soup of modern life

When content begins to feel like work, it begins to feel like… well, everything else. So much of our lives are composed of labour, both paid and unpaid. And though art should, in its best formulation, provide transcendent moments – experiences that pull us out of ourselves, and our circumstances – the deluge of content has flattened these moments into more capitalist stew.

Remember how special the release of a Star Wars movie used to feel? Remember the magic of it? Now, we have Star Wars spin-offs dropping every other month, and what was once rare and special is now an ever-decreasing series of diminishing returns. And these diminishing returns are not being made for the love of it – they’re coming from a cynical, money-grubbing place. Because they need to make money, due in no small part to their ballooning budgets, they are less adventurous, rehashing past story beats rather than coming up with new ones; playing fan service, instead of challenging audiences. After all, it’s called show business for a reason, and mass entertainment is profit-driven above all else, no matter how much it might enrich our lives.

This kind of nullifying sameness of content, made by capitalism, was first outlined by the philosophers Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer. “Culture now impresses the same stamp on everything,” they wrote in Dialectic of Enlightenment. “Films, radio and magazines make up a system which is uniform as a whole and in every part.”

Make a choice

So, what is to be done about all this? We obviously can’t stop the slow march of content. And we wouldn’t even want to – art still has the power to move us, even as it comes in a deluge.

Of course, being more aware of what we consume, and when we consume it, and why won’t stop capitalism. But it will change our relationship with art.

The answer, perhaps, is intentionality. This is a mindfulness practice – thinking about what we’re doing carefully, making every choice with a weight and thrust. Not doing anything passively, or just because you can. But applying ourselves fully to what we decide, and accepting that is the decision that we have made.

The filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard once said that at the cinema, audience goers look up, and at home, watching TV, audience goers look down. As it turns out, we look down at far too much these days, regardless of whether we’re at home or in the cinema. We take content for granted; allow it to blare out across us; reduce it to the status of wallpaper, just something to throw on and leave in the background. It becomes less special, and our relationship to it becomes less special too.

The answer: looking up. Of course, being more aware of what we consume, and when we consume it, and why won’t stop capitalism. But it will change our relationship with art. It will make us decision-makers – active agents, who engage seriously with content and learn things through it about our world. It will preserve some of that transcendence. And it will reduce the exhausting tyranny of choice, and make these decisions feel impactful.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The morals, aesthetics and ethics of art

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights