To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Isabella Vacaflores 11 MAR 2022

The western world has responded to Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine by imposing a historically large suite of economic sanctions upon them. Are such measures likely to cripple the kremlin, or are they merely wreaking havoc on the lives of innocent civilians?

Following the invasion, Lina, a 21-year-old living in Russia, found herself suddenly locked out of her OnlyFans account. Her loss of livelihood and income as an adult content creator was a direct consequence of comprehensive sanctions imposed upon her country. Taking to Twitter to voice her discontent, Lina wrote “I don’t support this war, but I became its hostage”.

Although OnlyFans has since reinstated Russian owned accounts, this has not stopped ordinary citizens from being caught in the crossfire of a war they do not necessarily condone. The rapidly plummeting value of the ruble coupled with aggressive boycotts has seen the cost of living skyrocket, causing many to question who is truly paying for this war.

Porn stars and geopolitics are worlds apart, as are innocent civilians and armed combatants. Universally recognised international humanitarian law tells us that jus in bello (justice in war) means protecting people not involved in the conflict from unnecessary hardship. The use of economic sanctions as an alternative to boots on ground intervention has challenged this principle, punishing everyone from the oligarchy to sex workers in one fell swoop.

Russia is a relatively impoverished, repressed, socioeconomically divided and bellicose country. The average citizen does not enjoy the same social and economic freedoms as those in the nations that sanction them. Such diplomatic measures might seem unethical because they have the potential to make innocent lives even more miserable – so why is the international community so trigger-happy when it comes to implementing them?

Sanctions in brief

The latent power of sanctions as a tool of foreign policy was revealed through the Blockade of Germany during WWI, where the restriction of maritime goods by naval boats played a crucial role in securing victory for the Allies. Taking this lesson into their stride, the League of Nations (superseded by the United Nations) began threatening the use of an “economic weapon” to reign in troublesome countries such as Italy and Japan, mostly unsuccessfully.

Using a mix of coercive tools ranging from the withdrawal of diplomatic and economic relations to boycotting sporting games, nations (usually acting collectively) set out to back their targeted regime into a corner. Coupled with the external pressure of being unable to access vital resources and capital, sanctions are designed to deteriorate living standards and stoke discontent to the point where governments are faced with the choice of kowtowing to international pressure or risk facing civil war.

Nowadays, sanctions are more ubiquitous than ever, despite having a demonstrably mixed track record.

The trade embargo in Cuba has cost the country over $130bn and has been in place for over 60 years. Nevertheless, the communist government has endured, with sanctions doing little more than providing the government with a scapegoat for its tanking economy. Research suggests that sanctions meet their stated objectives only 34 per cent of the time.

On the other hand, many credit such measures with delivering a fatal blow to apartheid in South Africa and nuclear proliferation in Iran. Even if such sanctions aren’t always successful, their utility can be viewed as largely symbolic, allowing nations to turn ideological enemies and human rights abusers into international outcasts, all without firing a single shot.

The ethics of using sanctions

From a consequentialist perspective – which looks to outcomes rather than intentions when it comes to making a moral judgement – the case for sanctions looks rather grim. To be ethically justified in pursuing such measures, those enacting this policy would want to be guaranteed that their actions are helping, not causing unnecessary hurt.

Perhaps a recognition of this principle was the reason why OnlyFans was so quick to backflip on their boycott. If only those pulling vodka from supermarket shelves and Dostoevsky from university reading lists could make this same calculus. These grandstanding gestures are not the kinds of actions that will meaningfully impact the course of war. If anything, they distract from a lack of meaningful action, erstwhile promoting xenophobic discourse.

It is worth noting that Joe Biden was referring to Putin, not his motherland, when he instructed the world to make the aggressor a “pariah on the international stage”. We would do well to remember the distinction between a country’s elite and their citizens (particularly in countries with low levels of democracy, like Russia) before implementing sanctions that treat them as one and the same.

As acknowledged by the United Nations, arguably the biggest international advocate for multilateral sanctions, sanctions often cause disproportionate economic and humanitarian harm to the very people they seek to protect. Additionally, such actions often cause collateral damage to otherwise uninvolved countries. Underscoring these issues is a lack of historical evidence to support the effectiveness of such measures.

Some may work their way around this point by arguing that such measures would shorten the war through crippling the economy, thereby negating some of the fallout for innocent civilians. However, the facts show otherwise – Sanctions stand the best chance of success when they are short, targeted, and implemented against a democratic government.

The measures in place against the kremlin meet none of these criteria, all but guaranteeing a prolonged amount of suffering for innocent civilians. To this end, imposing sanctions could be considered unethical.

Nevertheless, countries often justify their use of sanctions by claiming that they have a humanitarian duty to act against perceived injustice and moral violations. Accordingly, the ethicality of this decision must be judged to a different standard; if an actor is fulfilling their obligations as a member of the international community, then they are acting morally (a theory known as deontology).

This line of reasoning does not hold when it comes to the sanctions placed on Russia. Firstly, these actions replace a perceived injustice with perhaps an even greater one – the unnecessary involvement of innocent civilians in a conflict that is largely beyond their control. Some may justify this by arguing a responsibility to punish wrongdoers irrespective of the consequences, but the fact that all countries in the world are signatory to the principles of jus in bello vis-à-vis the Geneva Convention indicates a more binding duty. Undeniably, Russia has broken this code of conduct many times over, but moral decisions are not conducted on a tit-for-tat basis.

Secondly, they are not principally sound. Russia is one of the world’s largest suppliers of energy, yet curiously, this industry is largely exempt from most sanctions. We are unlikely to see this change significantly until the world moves away from fossil fuels altogether. Moreover, the international community will fail to cripple the kremlin unless it is willing to endure some short-term sacrifice for a greater duty.

Altogether, if those imposing sanctions are attempting to do so morally, they are failing. History has shown us what happens when we attempt to choke a country economically and politically, and it is ugly. We should be suspicious of the idea that sanctions are the only way for us to respond to misbehaving countries.

This is not to excuse citizens from the crimes of their government, but to call into question why the international community is so willing to use a tool that inevitably punishes the innocent, vulnerable, and often powerless (noting that this economic weapon is so often wielded against autocratic regimes).

The facts cannot be ignored; the elites responsible for the unprovoked invasion of Ukraine will continue to dodge sanctions through the likes of anonymous international bank accounts, foreign sympathisers and, increasingly, cryptocurrency. Meanwhile, people like Lina will shoulder the brunt of this burden.

All is fair in love and war – but some things are fairer than others, like avoiding the use of debunked tactics that mess with innocent lives needlessly. Without considering the ethicality of their behaviour, the international community risks causing an entirely avoidable humanitarian crisis which undermines the very principles that they to defend. We must think twice before we applaud those that are quick to sanction lest we cause more injustices to be committed.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jelaluddin Rumi

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

BY Isabella Vacaflores

Isabella is currently working as a research assistant at the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership. She has previously held research positions at Grattan Institute, Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet and the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University. She has won multiple awards and scholarships, including recently being named the 2023 Australia New Zealand Boston Consulting Group Women’s Scholar, for her efforts to improve gender, racial and socio-economic equality in politics and education.

Ethics Explainer: Power

Ethics Explainer: Power

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 11 MAR 2022

“If a white man wants to lynch me, that’s his problem. If he’s got the power to lynch me, that’s my problem. It’s not a question of attitude; it’s a question of power.” – Stokely Carmichael

A central concern of justice is who has power and how they should be allowed to use it. A central concern of the rest of us is how people with power in fact do use it. Both questions have animated ethicists and activists for hundreds of years, and their insights may help us as we try to create a just society.

A classic formulation is given by the eminent sociologist Max Weber, for whom power is “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance”. Michel Foucault, one of the century’s most prominent theorists of power, seems to echo this view: “if we speak of the structures or the mechanisms of power, it is only insofar as we suppose that certain persons exercise power over others”.

A rival view holds that instead of being a relation, power is a resource: like water, food, or money, power is a resource that a particular person or institution can accrue and it can therefore be justly or unjustly distributed. This view has been especially popular among feminist theorists who have used economic models of resource distribution to talk about gendered inequalities in social resources, including and especially power.

Susan Moller Okin is one prominent voice in this tradition:

“When we look seriously at the distribution of such critical social goods as power, self-esteem, opportunities for self-development … we find socially constructed inequalities between them, right down the list”.

What’s the difference between these two views? Why care? One answer is that our efforts to make power more just in society will depend on what kind of thing it is: if it’s a resource, such that problems of unfair power are problems of unequal distribution, we might be able to improve things by removing some power from some people – that way, they would no longer have more than others. This strategy would be less likely to work if power was a relation.

In addition to working out what power is, there are important moral questions about when it can be ethically used. This is a pressing question: As long as we live in societies, under democratic governments, or in states that use police forces and militaries to secure our goals, there will be at least one form of power to which everyone is subject: the power of the state.

The state is one of the only legitimate bearers of the power to use violence. If anyone else uses a weapon or a threat of imprisonment to secure their goals, we think they’re behaving illegitimately, but when the state does these things, we think it is – or can be – legitimate.

Since Plato, democracies have agreed that we need to allow and centralise some coercive power if we are to enforce our laws. Given the state’s unique power to use violence, it’s especially important that that power be just and fair. However, it’s challenging to spell what fair power is inside a democracy or how to design a system that will trend towards exemplifying it.

As Douglas Adams once wrote:

“The major problem with governing people – one of the major problems, for there are many – is that no-one capable of getting themselves elected should on any account be allowed to do the job”.

One recurring question for ‘fairness’ in political power is whether the people governed by the relevant political authority have a to obey that authority. When a state has the power to set laws and enforce them, for instance, does this issue a correlate duty for citizens to obey those laws? The state has duties to its people because it has so much power; but do people have reciprocal duties to their state, also rooted in its power?

Transposing this question into our personal lives, it’s sometimes thought that each of us has a kind of moral power to extract behaviour from others. If you don’t keep your promise, I can blame or sanction you into doing what you said you would. In other words, I can exercise my moral power to make claims of you. Does this sort of power work in the same way as political power? Is it possible for me to abuse my moral power over you; using it in ways that are unjust or unfair – and might you have a duty to obey that moral power?

Finally, we can ask valuable questions about what it is to be powerless. It’s certainly a site of complaint: many of us protest or object when we feel powerless. But how should we best understand it? Is powerlessness about actually being interfered with by others, or simply being susceptible to it, or vulnerable to it? For prominent philosopher Philip Pettit (AC), it’s the latter – to be “unfree” is to be vulnerable or susceptible to the other people’s whims, irrespective of whether they actually use their power against us.

If we want a more ethically ordered society, it’s important to understand how power works – and what goes wrong when it doesn’t.

Join us for the Ethics of Power on Thurs 14 March, 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Enough and as good left: Aged care, intergenerational justice and the social contract

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Volt Bank: Creating a lasting cultural impact

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Get mad and get calm: the paradox of happiness

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 3 MAR 2022

The invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces in the early hours of 24 February 2022 came as a violent shock to most onlookers.

Even after the visible buildup of Russian forces and weeks of sabre rattling by Russian President Vladimir Putin, the images of rockets striking apartment blocks and tanks rolling through city streets triggered an outpouring of support for Ukraine from people within Australia and around the world.

But those who dwell on social media might have seen some voices express a different perspective: that the focus on Ukraine is suggestive of a darker underlying bias on behalf of the onlookers; that the conflict has only gained so much attention because the victims of the war are white Europeans.

The argument suggests that if the victims were non-white, such as those involved in the ongoing wars in Yemen, Syria or Ethiopia, then the media and Western onlookers would be far less engaged.

So is it wrong to focus our attention acutely on the war in Ukraine while investing less energy on conflicts in other parts of the world, especially if those conflicts affect non-white people? Is it OK to care more about a war in Europe than it is a war in Africa or the Middle East?

We can unpack the argument in a few different ways. The least charitable interpretation is that it’s an accusation of racism, suggesting that people who care about the war in Ukraine only care because the victims are white. That might be true for some onlookers, but it’s highly doubtful that this applies to the majority of people.

Rather, there are many reasons why someone in Australia might place great significance on the events unfolding in Ukraine. First of all is the shock factor, particularly given the relative stability and lack of open wars between nations in Europe since the end of the Second World War. This means the war in Ukraine is not just a concern for that region but is of tremendous global significance, with the potential to reshape the geopolitical landscape in a way that could affect people around the world. In this way, the war in Ukraine very much qualifies as being worthy of our attention due to its historical significance.

There’s also the matter of familiarity, in the sense that Ukraine is a modern, industrialised and democratic nation that shares many political and moral values with countries like Australia. Beyond the human toll, the invasion represents an attack against values that most Australians cherish.

Many Australians also have friends, family or coworkers with connections to Ukraine or other European countries who are impacted by the war. To them, the war is not just news of distant events but is felt in their immediate circles in a way that other conflicts might not be. Of course, there are many Austrlians who are also affected by conflicts in other parts of the world, such as in Syria and Yemen.

Finally, on a more mundane level, the war in Ukraine is likely to have a material impact on our lives through its destabilisation of the international economy, as well as on commodity prices such as wheat and oil, in a way that most other ongoing conflicts don’t.

All this said, while the above can help explain why someone might take a more acute interest in the war in Ukraine, it doesn’t answer the ethical question of whether they should take greater interest in conflicts elsewhere at the same time. It’s possible that these explanations don’t justify an undue focus on one population experiencing conflict rather than another.

A more charitable interpretation of the argument is that all suffering deserves our attention, all violence deserves our rebuke and all people involved in wars deserve our empathy. This stems from a universalist ethic, such as that promoted by philosophers like Peter Singer. It argues that all people deserve equal concern, no matter their background, ethnicity or nationality. Singer famously argued that if you’d dive into a pond to save a drowning child, even at the cost of muddying your clothes and being late to work, then you ought to be willing to incur a similar cost to save the life of a dying child on the other side of the world.

From this perspective, the same reasons that justify our empathy towards the suffering of the Ukrainian people should similarly apply to the people of Yemen, Ethiopia, Syria and elsewhere.

However, a truly universalist ethic is difficult, if not impossible, to fully achieve in practice. Few people would be willing to take the ethic to the extreme, and treat strangers in distant countries with as much care and concern that they reserve for our family. If this is so, then it is difficult to know where to draw the line around who deserves more or less of our concern.

Furthermore, everybody has a finite budget of time, emotional energy and power to act. It is not possible to be engaged with every conflict, every injustice and every instance of ethical wrongdoing taking place in the world, let alone to be able to act on them. It might be reasonable for people to choose where to invest their limited energy, or to preserve their energy for causes they can positively impact. That doesn’t mean they don’t care about other issues, only that they’ve chosen to do good where they can.

Which brings us to the most charitable interpretation of the argument, which is that any conflict should remind us of the horrors of war, and should motivate us to extend our empathy to people who are suffering anywhere in the world. The saturation media footage of violence and destruction in Ukraine can help us better understand the plight of people living through other conflicts. The plight of embattled civilians in Kyiv can help us better understand and empathise with people living in Aleppo in Syria or Sanaa in Yemen.

It is unlikely that those promoting this argument on social media would want people to retreat from engaging with all news of conflict or suffering, whether it is in Europe or elsewhere. Rather, we might forgive people for having some bias in where they choose to direct their attention, while reminding them that all people are deserving of ethical consideration. Moral consideration need not be a zero-sum game; elevating our concern for one population doesn’t have to come at the expense of concern for others.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ad Hominem Fallacy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Barbie and what it means to be human

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Tolerance

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 28 FEB 2022

Euphoria has been, for almost two years now, approaching a fever pitch of horror, addiction, heartbreak and self-destruction.

Its assembled cast of characters – most notably Rue (Zendaya), who starts the first season emerging straight out of rehab – sit constantly on the verge of total nervous collapse. They are always one bad party away from cataclysmic suffering, their lives hanging in a painful balance between “just about getting by” and “absolute devastation.”

Indeed, even if its utter melodrama means that Euphoria doesn’t actually reflect how high school is – who could cram in that much explosive melancholy before the lunch bell? – it certainly reflects how high school feels. There are few experiences more tortured and heightened than being a teenager, when your whole skin feels on fire, and possibilities splinter out from in front of your feet at every single moment. There is the sense of the future being unwritten; of your life being terrifyingly in your own hands.

But what does Euphoria’s constant hysteria do to its viewers, particularly its younger ones? If the devastation of adolescence really is that severe, then are artists failing, somehow, if they merely reflect that devastation? Should we ask our art to serve an instructional purpose; to pull us out of the traps we have built for ourselves? Or should art settle into those traps, letting their metal teeth sink into their skin?

Image: Euphoria, HBO

The Long History Of “Evil” Art

The question of the moral responsbility of artists is particularly pertinent in the case of Euphoria because of its emphasis on what have been typically viewed as “illicit” activities, from drug-taking to underage sex. These are – to the great detriment of a truly free society – taboo subjects, deemed inappropriate for discussion in public spaces, and condemned to be whispered, rather than shouted about.

Indeed, there is a long history of conservatives and moral puritans rallying against artworks that they feel ‘glamorize’ or somehow indulge bad and illegal behaviour. Take, for instance, the Satanic Panic that gripped the United Kingdom in the ‘80s. Shortly after the advent of home video, the market became flooded with what were then termed “video nasties”, a wave of cheaply made horror films that actively marketed themselves for their moral repugnance. The point was how many taboos could be broken; into how much blood and muck and horror that filmmakers could sink themselves, like half-formed and discarded babies being thrown to rest in a mud puddle.

This, to many pro-censorship thinkers at the time, was seen as a kind of moral crime – an unspeakable act, with the ability to influence and addle the minds of Britain’s younger generation. The demand from conservatives was that art be a way of modelling good ethical behaviour, and the worry, expressed furiously in the tabloids, was that any other alternative would lead to the breakdown of society itself.

So no, the question as to whether art should be instructional is not new; the fear that it might lead the minds of the younger generation astray far from fresh. Euphoria might seem relentlessly modern, with its lived-in cinematic voice, and its restless politics. But it is part of a tradition of artworks that submerge themselves in darkness and despair; vice and what some, most of them on the right, deem the immoral.

The Unspoken Becomes Spoken

The mistake made, however, by those who imagine such art is failing an explicit moral purpose, a kind of sentimental education, rests on an outdated and functionally useless understanding of morality. These critics imagine that there is just one way to live well. They believe in uncrossable boundaries of taboo and immorality; that there are iron-wrought moral rules, and that any art that breaks those rules will lead to some kind of negative and harmful shifting of what is acceptable amongst the citizens of any democratic society.

But why should we believe that morality is so strict? We would do well to move away from an objective, centralised view of morality, where there exists a list of rules, printed in indelible ink somewhere, that are inflexible and pre-ordained. Societally, as well as personally, change is the only constant. If we abide by a set of constructed ethical principles that do not reflect that change, we will be forever torn between a possible future and a weighty past, bogged down in a system of conduct that no longer represents the complexity of what it means to be human.

If we have any true moral imperative, it is to constantly be in the process of testing and re-shaping our morals. It was John Stuart Mill who developed a similar concept of truth – who believed that we could only remain honest, and democratic, if we were forever challenging that which we had taken for granted. Art is a process of this moral re-shaping. Great art need not shy away from that which we hold to be “good” or “right”, or, on the flipside, “harmful” and “taboo.”

It is not that art need to be amoral, free from ethical concerns, with artists resisting any urge to provide some form of moral instruction – it is that we need to let go of the idea that this moral instruction can only take the form of propping up old and unchanging notions of goodness. The immoral and the moral are only useful concepts if they teach us something about how to live, and they will only teach us something about how to live if we make sure they are forever being tested and examined.

Finding Yourself

Image: Euphoria, HBO

This is what Euphoria does. By basking in that which has been taken as illicit – in particular, the sex and chemical lives of America’s teenagers – the show makes the unspoken spoken. It draws into focus an outdated and ancient view of the good life, and challenges us to stare our conceptions of self-perpetuation and self-destruction in the face.

Rue, forever in the process of re-shaping herself in the shadow of her great addiction, makes mistakes. Cassie (Sydney Sweeney), Euphoria’s shaking, panic-addled heart, makes even more. Both of them stray from pre-written social conceptions of the “good girl”, dissolving an ancient and harmful angel/whore dichotomy, and proving that there are no static boundaries between what is admirable and what is abhorrent.

Just as the show itself skirts back and forth across the line between our notions of the ethical and the immoral, so too do these characters forever find themselves testing the limits of what is good for them, and those around them. They are flawed, vulnerable people. But in these flaws – in this very notion of trembling possibility, the rules of good conduct forever being written in sand – they do provide us with a moral education. Not one that rests on simplistic notions of what we should do, and when. But one that proves that as both a society, and as individuals in that society, we should always be taking that which has been shrouded in darkness and throw it – sometimes painfully – into the light.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Relativism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Joseph Earp 22 FEB 2022

Dr. Chris Letheby, a pioneer in the philosophy of psychedelics, is looking at a chair. He is taking in its individuated properties – its colour, its shape, its location – and all the while, his brain is binding these properties together, making them parts of a collective whole.

This, Letheby explains, is also how we process the self. We know that there are a number of distinct properties that make us who we are: the sensation of being in our bodies, the ability to call to mind our memories or to follow our own trains of thought. But there is a kind of mental glue that holds these sensations together, a steadfast, mostly uncontested belief in the concrete entity to which we refer when we use the word “me.”

“Binding is a theoretical term,” Letheby explains. “It refers to the integration of representational parts into representational wholes. We have all these disparate representations of parts of our bodies and who we were at different points at time and different roles we occupy and different personality traits. And there’s a very high-level process that binds all of these into a unified representation; that makes us believe these are all properties and attributes of one single thing. And different things can be bound to this self model more tightly.”

Freed from the Self

So what happens when these properties become unbound from one another – when we lose a cohesive sense of who we are? This, after all, is the sensation that many experience when taking psychedelic drugs. The “narrative self” – the belief that we are an individuated entity that persists through time – dissolves. We can find ourselves at one with the universe, deeply connected to those around us.

Perhaps this sounds vaguely terrifying – a kind of loss. But as Letheby points out, this “ego dissolution” can have extraordinary therapeutic results in those who suffer from addiction, or experience deep anxiety and depression.

“People can get very harmful, unhealthy, negative forms of self-representation that become very rigidly and deeply entrenched,” Letheby explains.

“This is very clear in addiction. People very often have all sorts of shame and negative views of themselves. And they find it very often impossible to imagine or to really believe that things could be different. They can’t vividly imagine a possible life, a possible future in which they’re not engaging in whatever the addictive behaviours are. It becomes totally bound in the way they are. It’s not experienced as a belief, it’s experienced as reality itself.”

This, Letheby and his collaborator Philip Gerrans write, is key to the ways in which psychedelics can improve our lives. “Psychedelics unbind the self model,” he says. “They decrease the brain’s confidence in a belief like, ‘I am an alcoholic’ or ‘I am a smoker’. And so for the first time in perhaps a very long time [addicts] are able to not just intellectually consider, but to emotionally and experientially imagine a world in which they are not an alcoholic. Or if we think about anxiety and depression, a world in which there is hope and promise.”

A comforting delusion?

Letheby’s work falls into a naturalistic framework: he defers to our best science to make sense of the world around us. This is an unusual position, given some philosophers have described psychedelic experiences as being at direct odds with naturalism. After all, a lot of people who trip experience what have been called “metaphysical hallucinations”: false beliefs about the “actual nature” of the universe that fly in the face of what science gives us reason to believe.

For critics of the psychedelic experience then, these psychedelic hallucinations can be described as little more than comforting falsehoods, foisted upon the sick – whether mentally or physically – and dying. They aren’t revelations. They are tricks of the mind, and their epistemic value remains under question.

But Letheby disagrees. He adopts the notion of “epistemic innocence” from the work of philosopher Lisa Bortolotti, the belief that some falsehoods can actually make us better epistemic agents. “Even if you are a naturalist or a materialist, psychedelic states aren’t as epistemically bad as they have been made out to be,” he says, simply. “Sometimes they do result in false beliefs or unjustified beliefs … But even when psychedelic experiences do lead to people to false beliefs, if they have therapeutic or psychological benefits, they’re likely to have epistemic benefits too.”

To make this argument, Letheby returns again to the archetype of the anxious or depressed person. This individual, when suffering from their illness, commonly retreats from the world, talking less to their friends and family, and thus harming their own epistemic faculties – if you don’t engage with anyone, you can’t be told that you are wrong, can’t be given reasons for updating your beliefs, can’t search out new experiences.

“If psychedelic states are lifting people out of their anxiety, their depression, their addiction and allowing people to be in a better mode of functioning, then my thought is, that’s going to have significant epistemic benefits,” Letheby says. “It’s going to enable people to engage with the world more, be curious, expose their ideas to scrutiny. You can have a cognition that might be somewhat inaccurate, but can have therapeutic benefits, practical benefits, that in turn lead to epistemic benefits.”

As Letheby has repeatedly noted in his work, the study of the psychiatric benefits of psychedelics is in its early phases, but the future looks promising. More and more people are experiencing these hallucinations – these new, critical beliefs that unbind the self – and more and more people are getting well. There is, it seems, a possible world where many of us are freed from the rigid notions of who we are and what we want, unlocked from the cage of the self, and walking, for the first time in a long time, in the open air.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The rise of Artificial Intelligence and its impact on our future

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Now is the time to talk about the Voice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 FEB 2022

Ethics is about engaging in conversations to understand different perspectives and ways in which we can approach the world.

Which means we need a range of people participating in the conversation.

That’s why we’re excited to share that we have recently appointed Dr Tim Dean as our Senior Philosopher. An award-winning philosopher, writer, speaker and honorary associate with the University of Sydney, Tim has developed and delivered philosophy and emotional intelligence workshops for schools and businesses across Australia and the Asia Pacific, including Meriden and St Mark’s high schools, The School of Life, Small Giants and businesses including Facebook, Commonwealth Bank, Aesop, Merivale and Clayton Utz.

We sat down with Tim to discuss his views on morality, social media, cancel culture and what ethics means to him.

What drew you to the study of philosophy?

Children are natural philosophers, constantly asking “why?” about everything around them. I just never grew out of that tendency, much to the chagrin of my parents and friends. So when I arrived at university, I discovered that philosophy was my natural habitat, furnishing me with tools to ask “why?” better, and revealing the staggering array of answers that other thinkers have offered throughout the ages. It has also helped me to identify a sense of meaning and purpose that drives my work.

What made you pursue the intersection of science and philosophy?

I see science and philosophy as continuous. They are both toolkits for understanding the world around us. In fact, technically, science is a sub-branch of philosophy (even if many scientists might bristle at that idea) that specialises in questions that are able to be investigated using empirical tools, hence its original name of “natural philosophy”. I have been drawn to science as much as philosophy throughout my life, and ended up working as a science writer and editor for over 10 years. And my study of biology and evolution transformed my understanding of morality, which was the subject of my PhD thesis.

How does social media skew our perception of morals?

If you wanted to create a technology that gave a distorted perception of the world, that encouraged bad faith discourse and that promoted friction rather than understanding, you’d be hard pressed to do better than inventing social media. Social media taps into our natural tendencies to create and defend our social identity, it triggers our natural outrage response by feeding us an endless stream of horrific events, it rewards us with greater engagement when we go on the offensive while preventing us from engaging with others in a nuanced way. In short, it pushes our moral buttons, but not in a constructive way. So even though social media can do good, such as by raising awareness of previously marginalised voices and issues, overall I’d call it a net negative for humanity’s moral development.

How do you think the pandemic has changed the way we think about ethics?

The COVID-19 pandemic has both expanded and shrunk our world. On the one hand, lockdowns and border closures have grounded us in our homes and our local communities, which in many cases has been a positive thing, as people get to know their neighbours and look out for each other. But it has also expanded our world as we’ve been stuck behind screens watching a global tragedy unfold, often without any real power to fix it. But it has also made us more sensitive to how our individual actions affect our entire community, and has caused us to think about our obligations to others. In that sense, it has brought ethics to the fore.

Tell us a little about your latest book ‘How We Became Human, And Why We Need to Change’?

I’ve long been fascinated by the story of how we evolved from being a relatively anti-social species of ape a few million years ago to being the massively social species we are today. Morality has played a key part in that story, helping us to have empathy for others, motivating us to punish wrongdoing and giving us a toolkit of moral norms that can guide our community’s behaviour. But in studying this story of moral evolution, I came to realise that many of the moral tendencies we have and many of the moral rules we’ve inherited were designed in a different time, and they often cause more harm than good in today’s world. My book explores several modern problems, like racism, sexism, religious intolerance and political tribalism, and shows how they are all, in part, products of our evolved nature. I also argue that we need to update our moral toolkit if we want to live and thrive in a modern, globalised and diverse world, and that means letting go of past solutions and inventing new ones.

How do you think the concepts of right and wrong will change in the coming years?

The world is changing faster than ever before. It’s also more diverse and fragmented than ever before. This means that the moral rules that we live by and the values that drive us are also changing faster than ever before – often faster than many people can keep up. Moral change will only continue, especially as new generations challenge the assumptions and discard the moral baggage of past generations. We should expect that many things we took for granted will be challenged in the coming decades. I foresee a huge challenge in bringing people along with moral change rather than leaving them behind.

What are your thoughts on the notion of ‘cancel culture’?

There are no easy answers when it comes to the limits of free speech. We value free speech to the degree that it allows us to engage with new ideas, seek the truth and to be able to express ourselves and hear from others. But that speech comes at a cost, particularly when it allows bad faith speech to spread misinformation, to muddy the truth, or dehumanise others. There are some types of speech that ought to be shut down, but we must be careful how the power to shut down speech is used. In the same way that some speech can be in bad faith, so too can be efforts to shut it down. Some instances of “cancelling” might be warranted, but many are a symptom of mob culture that seeks to silence views the mob opposes rather than prevent bad kinds of speech. Sometimes it’s motivated by a sense that a speaker is not just mistaken but morally corrupt, which prevents people from engaging with them and attempting to change their views. This is why one thing I advocate strongly for is rebuilding social capital, or the trust and respect that enables good faith discourse to occur at all. It’s only when we have that trust and respect that we will be able to engage in good faith rather than feel like we need to resort to cancelling or silencing people.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

Ethics is what makes our species unique. No other creature can live alongside and cooperate with other individuals on the scale that we do. This is all made possible by ethics, which is our ability to consider how we ought to behave towards others and what rules we should live by. It’s our superpower, it’s what has enabled our species to spread across the globe. But understanding and engaging with ethics, figuring out our obligations to others, and adapting our sense of right and wrong to a changing world, is our greatest and most enduring challenge as a species.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Other

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Mehhma Malhi 18 FEB 2022

The use of deepfake technology is increasing as more companies devise different models.

It is a form of technology where a user can upload an image and synthetically augment a video of a real person or create a picture of a fake person. Many people have raised concerns about the harmful possibilities of these technologies. Yet, the notion of deception that is at the core of this technology is not entirely new. History is filled with examples of fraud, identity theft, and counterfeit artworks, all of which are based on imitation or assuming a person’s likeliness.

In 1846, the oldest gallery in the US, The Knoedler, opened its doors. By supplying art to some of the most famous galleries and collectors worldwide, it gained recognition as a trusted source of expensive artwork – such as Rothko’s and Pollock’s. However, unlike many other galleries, The Knoedler allowed citizens to purchase the art pieces on display. Shockingly, in 2009, Ann Freedman, who had been appointed as the gallery director a decade prior, was famously prosecuted for knowingly selling fake artworks. After several buyers sought authentication and valuation of their purchases for insurance purposes, the forgeries came to light. The scandal was sensational, not only because of the sheer number of artworks involved in the deception that lasted years but also because millions of dollars were scammed from New York’s elite.

The grandiose art foundation of NYC fell as the gallery lost its credibility and eventually shut down. Despite being exact replicas and almost indistinguishable, the understanding of the artist and the meaning of the artworks were lost due to the lack of emotion and originality. As a result, all the artworks lost sentimental and monetary value.

Yet, this betrayal is not as immoral as stealing someone’s identity or engaging in fraud by forging someone’s signature. Unlike artwork, when someone’s identity is stolen, the person who has taken the identity has the power to define how the other person is perceived. For example, catfishing online allows a person to misrepresent not only themselves but also the person’s identity that they are using to catfish with. This is because they ascribe specific values and activities to a person’s being and change how they are represented online.

Similarly, deepfakes allow people to create entirely fictional personas or take the likeness of a person and distort how they represent themselves online. Online self-representations are already augmented to some degree by the person. For instance, most individuals on Instagram present a highly curated version of themselves that is tailored specifically to garner attention and draw particular opinions.

But, when that persona is out of the person’s control, it can spur rumours that become embedded as fact due to the nature of the internet. An example is that of celebrity tabloids. Celebrities’ love lives are continually speculated about, and often these rumours are spread and cemented until the celebrity comes out themselves to deny the claims. Even then, the story has, to some degree, impacted their reputation as those tabloids will not be removed from the internet.

The importance of a person maintaining control of their online image is paramount as it ensures their autonomy and ability to consent. When deepfakes are created of an existing person, it takes control of those tenets.

Before delving further into the ethical concerns, understanding how this technology is developed may shed light on some of the issues that arise from such a technology.

The technology is derived from deep learning, a type of artificial intelligence based on neural networks. Deep neural network technologies are often composed of layers based on input/output features. It is created using two sets of algorithms known as the generator and discriminator. The former creates fake content, and the latter must determine the authenticity of the materials. Each time it is correct, it feeds information back to the generator to improve the system. In short, if it determines whether the image is real correctly, the input receives a greater weighting. Together this process is known as generative adversarial network (GAN). It uses the process to recognise patterns which can then be compiled to make fake images.

With this type of model, if the discriminator is overly sensitive, it will provide no feedback to the generator to develop improvements. If the generator provides an image that is too realistic, the discriminator can get stuck in a loop. However, in addition to the technical difficulties, there are several serious ethical concerns that it gives rise to.

Firstly, there have been concerns regarding political safety and women’s safety. Deepfake technology has advanced to the extent that it can create multiple photos compiled into a video. At first, this seemed harmless as many early adopters began using this technology in 2019 to make videos of politicians and celebrities singing along to funny videos. However, this technology has also been used to create videos of politicians saying provocative things.

Unlike, photoshop and other editing apps that require a lot of skill or time to augment images, deepfake technology is much more straightforward as it is attuned to mimicking the person’s voice and actions. Coupling the precision of the technology to develop realistic images and the vast entity that we call the internet, these videos are at risk of entering echo chambers and epistemic bubbles where people may not know that these videos are fake. Therefore, one primary concern regarding deepfake videos is that they can be used to assert or consolidate dangerous thinking.

These tools could be used to edit photos or create videos that damage a person’s online reputation, and although they may be refuted or proved as not real, the images and effects will remain. Recently, countries such as the UK have been demanding the implementation of legislation that limits deepfake technology and violence against women. Specifically, there is a slew of apps that “nudify” any individual, and they have been used predominantly against women. All that is required of users is to upload an image of a person. One version of this website gained over 35 million hits over a few days. The use of deepfake in this manner creates non-consensual pornography that can be used to manipulate women. Because of this, the UK has called for stronger criminal laws for harassment and assault. As people’s main image continues to merge with technology, the importance of regulating these types of technology is paramount to protect individuals. Parameters are increasingly pertinent as people’s reality merges with the virtual world.

However, like with any piece of technology, there are also positive uses. For example, Deepfake technology can be used in medicine and education systems by creating learning tools and can also be used as an accessibility feature within technology. In particular, the technology can recreate persons in history and can be used in gaming and the arts. In more detail, the technology can be used to render fake patients whose data can be used in research. This protects patient information and autonomy while still providing researchers with relevant data. Further, deepfake tech has been used in marketing to help small businesses promote their products by partnering them with celebrities.

Deepfake technology was used by academics but popularised by online forums. Not used to benefit people initially, it was first used to visualise how certain celebrities would look in compromising positions. The actual benefits derived from deepfake technology were only conceptualised by different tech groups after the basis for the technology had been developed.

The conception of such technology often comes to fruition due to a developer’s will and, given the lack of regulation, is often implemented online.

While there are extensive benefits to such technology, there need to be stricter regulations, and people who abuse the scope of technology ought to be held accountable. As we see our present reality merge with virtual spaces, a person’s online presence will continue to grow in importance. Stronger regulations must be put into place to protect people’s online persona.

While users should be held accountable for manipulating and stripping away the autonomy of individuals by using their likeness, more specifically, developers must be held responsible for using their knowledge to develop an app using deepfake technology that actively harms.

To avoid a fallout like Knoedler, where distrust, skepticism, and hesitancy rooted itself in the art community, we must alert individuals when deepfake technology is employed; even in cases where the use is positive, be transparent that it has been used. Some websites teach users how to differentiate between real and fake, and some that process images to determine their validity.

Overall, this technology can help individuals gain agency; however, it can also limit another persons’ right to autonomy and privacy. This type of AI brings unique awareness to the need for balance in technology.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ANZAC day lie

Big thinker

Relationships

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

BY Mehhma Malhi

Mehhma recently graduated from NYU having majored in Philosophy and minoring in Politics, Bioethics, and Art. She is now continuing her study at Columbia University and pursuing a Masters of Science in Bioethics. She is interested in refocusing the news to discuss why and how people form their personal opinions.

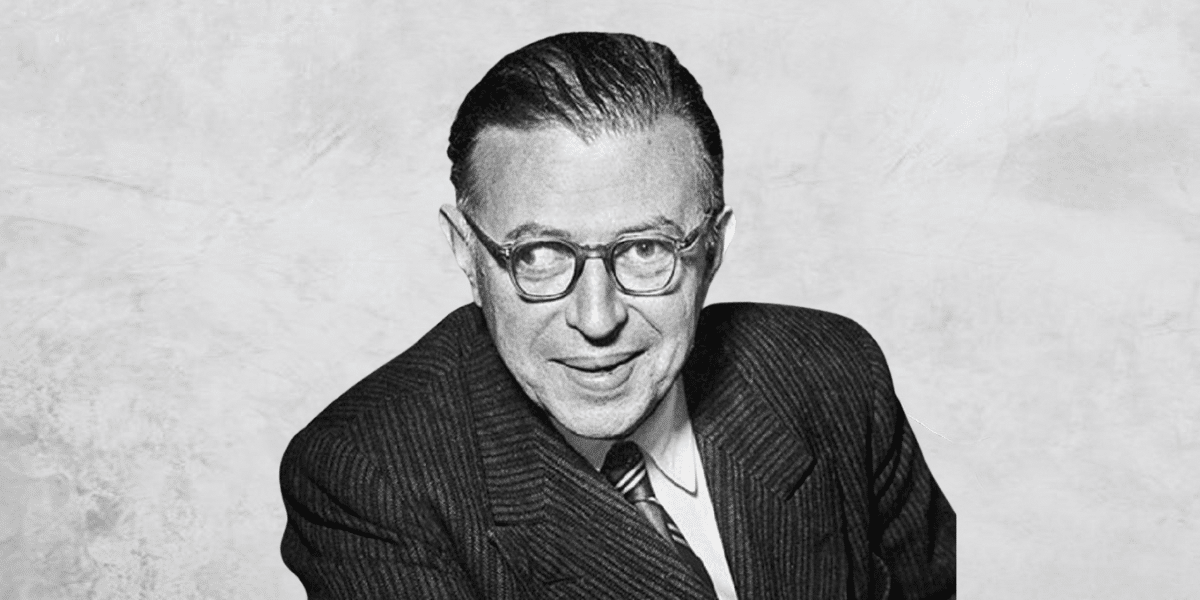

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) is one of the best known philosophers of the 20th century, and one of few who became a household name. But he wasn’t only a philosopher – he was also a provocative novelist, playwright and political activist.

Sartre was born in Paris in 1905, and lived in France throughout his entire life. He was conscripted during the war, but was spared the front line due to his exotropia, a condition that caused his right eye to wander. Instead, he served as a meteorologist, but was captured by German forces as they invaded France in 1940. He spent several months in a prisoner of war camp, making the most of the time by writing, and then returned to occupied Paris, where he remained throughout the war.

Before, during and after the war, he and his lifelong partner, the philosopher and novelist Simone de Beauvoir, were frequent patrons of the coffee houses around Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. There, they and other leading thinkers of the time, like Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, cemented the cliché of bohemian thinkers smoking cigarettes and debating the nature of existence, freedom and oppression.

Sartre started writing his most popular philosophical work, Being and Nothingness, while still in captivity during the war, and published it in 1943. In it, he elaborated on one of his core themes: phenomenology, the study of experience and consciousness.

Learning from experience

Many philosophers who came before Sartre were sceptical about our ability to get to the truth about reality. Philosophers from Plato through to René Descartes and Immanuel Kant believed that appearances were deceiving, and what we experience of the world might not truly reflect the world as it really is. For this reason, these thinkers tended to dismiss our experience as being unreliable, and thus fairly uninteresting.

But Sartre disagreed. He built on the work of the German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl to focus attention on experience itself. He argued that there was something “true” about our experience that is worthy of examination – something that tells us about how we interact with the world, how we find meaning and how we relate to other people.

The other branch of Sartre’s philosophy was existentialism, which looks at what it means to be beings that exist in the way we do. He said that we exist in two somewhat contradictory states at the same time.

First, we exist as objects in the world, just as any other object, like a tree or chair. He calls this our “facticity” – simply, the sum total of the facts about us.

The second way is as subjects. As conscious beings, we have the freedom and power to change what we are – to go beyond our facticity and become something else. He calls this our “transcendence,” as we’re capable of transcending our facticity.

However, these two states of being don’t sit easily with one another. It’s hard to think of ourselves as both objects and subjects at the same time, and when we do, it can be an unsettling experience. This experience creates a central scene in Sartre’s most famous novel, Nausea (1938).

Freedom and responsibility

But Sartre thought we could escape the nausea of existence. We do this by acknowledging our status as objects, but also embracing our freedom and working to transcend what we are by pursuing “projects.”

Sartre thought this was essential to making our lives meaningful because he believed there was no almighty creator that could tell us how we ought to live our lives. Rather, it’s up to us to decide how we should live, and who we should be.

“Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself.”

This does place a tremendous burden on us, though. Sartre famously admitted that we’re “condemned to be free.” He wrote that “man” was “condemned, because he did not create himself, yet is nevertheless at liberty, and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does.”

This radical freedom also means we are responsible for our own behaviour, and ethics to Sartre amounted to behaving in a way that didn’t oppress the ability of others to express their freedom.

Later in life, Sartre became a vocal political activist, particularly railing against the structural forces that limited our freedom, such as capitalism, colonialism and racism. He embraced many of Marx’s ideas and promoted communism for a while, but eventually became disillusioned with communism and distanced himself from the movement.

He continued to reinforce the power and the freedom that we all have, particularly encouraging the oppressed to fight for their freedom.

By the end of his life in 1980, he was a household name not only for his insightful and witty novels and plays, but also for his existentialist phenomenology, which is not just an abstract philosophy, but a philosophy built for living.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Relativism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

Research shows that physical appearance can affect everything from the grades of students to the sentencing of convicted criminals – are looks and morality somehow related?

Ancient philosophers spoke of beauty as a supreme value, akin to goodness and truth. The word itself alluded to far more than aesthetic appeal, implying nobility and honour – it’s counterpart, ugliness, made all the more shameful in comparison.

From the writings of Plato to Heraclitus, beautiful things were argued to be vital links between finite humans and the infinite divine. Indeed, across various cultures and epochs, beauty was praised as a virtue in and of itself; to be beautiful was to be good and to be good was to be beautiful.

When people first began to ask, ‘what makes something (or someone) beautiful?’, they came up with some weird ideas – think Pythagorean triangles and golden ratios as opposed to pretty colours and chiselled abs. Such aesthetic ideals of order and harmony contrasted with the chaos of the time and are present throughout art history.

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, c.1490

These days, a more artificial understanding of beauty as a mere observable quality shared by supermodels and idyllic sunsets reigns supreme.

This is because the rise of modern science necessitated a reappraisal of many important philosophical concepts. Beauty lost relevance as a supreme value of moral significance in a time when empirical knowledge and reason triumphed over religion and emotion.

Yet, as the emergence of a unique branch of philosophy, aesthetics, revealed, many still wondered what made something beautiful to look at – even if, in the modern sense, beauty is only skin deep.

Beauty: in the eye of the beholder?

In the ancient and medieval era, it was widely understood that certain things were beautiful not because of how they were perceived, but rather because of an independent quality that appealed universally and was unequivocally good. According to thinkers such as Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, this was determined by forces beyond human control and understanding.

Over time, this idea of beauty as entirely objective became demonstrably flawed. After all, if this truly were the case, then controversy wouldn’t exist over whether things are beautiful or not. For instance, to some, the Mona Lisa is a truly wonderful piece of art – to others, evidence that Da Vinci urgently needed an eye check.

Consequently, definitions of beauty that accounted for these differences in opinion began to gain credence. David Hume famously quipped that beauty “exists merely in the mind which contemplates”. To him and many others, the enjoyable experience associated with the consumption of beautiful things was derived from personal taste, making the concept inherently subjective.

This idea of beauty as a fundamentally pleasurable emotional response is perhaps the closest thing we have to a consensus among philosophers with otherwise divergent understandings of the concept.

Returning to the debate at hand: if beauty is not at least somewhat universal, then why do hundreds and thousands of people every year visit art galleries and cosmetic surgeons in pursuit of it? How can advertising companies sell us products on the premise that they will make us more beautiful if everyone has a different idea of what that looks like? Neither subjectivist nor objectivist accounts of the concept seem to adequately explain reality.

According to philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and Francis Hutcheson, the answer must lie somewhere in the middle. Essentially, they argue that a mind that can distance itself from its own individual beliefs can also recognize if something is beautiful in a general, objective sense. Hume suggests that this seemingly universal standard of beauty arises when the tastes of multiple, credible experts align. And yet, whether or not this so-called beautiful thing evokes feelings of pleasure is ultimately contingent upon the subjective interpretation of the viewer themselves.

Looking good vs being good

If this seemingly endless debate has only reinforced your belief that beauty is a trivial concern, then you are not alone! During modernity and postmodernity, philosophers largely abandoned the concept in pursuit of more pressing matters – read: nuclear bombs and existential dread. Artists also expressed their disdain for beauty, perceived as a largely inaccessible relic of tired ways of thinking, through an expression of the anti-aesthetic.

Nevertheless, we should not dismiss the important role beauty plays in our day-to-day life. Whilst its association with morality has long been out of vogue among philosophers, this is not true of broader society. Psychological studies continually observe a ‘halo effect’ around beautiful people and things that see us interpret them in a more favourable light, leading them to be paid higher wages and receive better loans than their less attractive peers.

Social media makes it easy to feel that we are not good enough, particularly when it comes to looks. Perhaps uncoincidentally, we are, on average, increasing our relative spending on cosmetics, clothing, and other beauty-related goods and services.

Turning to philosophy may help us avoid getting caught in a hamster wheel of constant comparison. From a classical perspective, the best way to achieve beauty is to be a good person. Or maybe you side with the subjectivists, who tell us that being beautiful is meaningless anyway. Irrespective, beauty is complicated, ever-important, and wonderful – so long as we do not let it unfairly cloud our judgements.

Step through the mirror and examine what makes someone (or something) beautiful and how this impacts all our lives. Join us for the Ethics of Beauty on Thur 29 Feb 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Israel Folau: appeals to conscience cut both ways

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why morality must evolve

If you read the news or spend any time on social media, then you’d be forgiven for thinking that there’s a lack of morality in the world today.

There is certainly no shortage of serious social and moral problems in the world. People are discriminated against just because of the colour of their skin. Many women don’t feel safe in their own home or workplace. Over 450 million children around the world lack access to clean water. There are whole industries that cause untold suffering to animals. New technologies like artificial intelligence are being used to create autonomous weapons that might slip from our control. And people receive death threats simply for expressing themselves online.

It’s easy to think that if only morality featured more heavily in people’s thinking, then the world would be a better place. But I’m not convinced. This might sound strange coming from a moral philosopher, but I have come to believe that the problem we face isn’t a lack of morality, it’s that there’s often too much. Specifically, too much moral certainty.

The most dangerous people in the world are not those with weak moral views – they are those who have unwavering moral convictions. They are the ones who see the world in black and white, as if they are in a war between good and evil. They are ones who are willing to kill or die to bring about their vision of utopia.

That said, I’m not quite ready to give up on morality yet. It sits at the heart of ethics and guides how we decide on what is good and bad. It’s still central to how we live our lives. But it also has a dark side, particularly in its power to inspire rigid black and white thinking. And it’s not just the extremists who think this way. We are all susceptible to it.

To show you what I mean, let me ask you what will hopefully be an easy question:

Is it wrong to murder someone, just because you don’t like the look of their face?

I’m hoping you will say it is wrong, and I’m going to agree with you, but when we look at what we mean when we respond this way, it can help us understand how we think about right and wrong.

When we say that something like this is wrong, we’re usually not just stating a personal preference, like “I simply prefer not to murder people, but I don’t mind if you do so”. Typically, we’re saying that murder for such petty reasons is wrong for everyone, always.

Statements like these seem to be different from expressions of subjective opinion, like whether I prefer chocolate to strawberry ice cream. It seems like there’s something objective about the fact that it’s wrong to murder someone because you don’t like the look of their face. And if someone suggests that it’s just a subjective opinion – that allowing murder is a matter of personal taste – then we’re inclined to say that they’re just plain wrong. Should they defend their position, we might even be tempted to say they’re not only mistaken about some basic moral truth, but that they’re somehow morally corrupt because they cannot appreciate that truth.

Murdering someone because you don’t like the look of their face is just wrong. It’s black and white.

This view might be intuitively appealing, and it might be emotionally satisfying to feel as if we have moral truth on our side, but it has two fatal flaws. First, morality is not black and white, as I’ll explain below. Second, it stifles our ability to engage with views other than our own, which we are bound to do in a large and diverse world.

So instead of solutions, we get more conflict: left versus right, science versus anti-vaxxers, abortion versus a right to choose, free speech versus cancel culture. The list goes on.

Now, more than ever, we need to get away from this black and white thinking so we can engage with a complex moral landscape, and be flexible enough to adapt our moral views to solve the very real problems we face today.

The thing is, it’s not easy to change the way we think about morality. It turns out that it’s in our very nature to think about it in black and white terms.

As a philosopher, I’ve been fascinated by the story of where morality came from, and how we evolved from being a relatively anti-social species of ape a few million years ago to being the massively social species we are today.

Evolution plays a leading role in this story. It didn’t just shape our bodies, like giving us opposable thumbs and an upright stance. It also shaped our minds: it made us smarter, it gave us language, and it gave us psychological and social tools to help us live and cooperate together relatively peacefully. We evolved a greater capacity to feel empathy for others, to want to punish wrongdoers, and to create and follow behavioural rules that are set by our community. In short: we evolved to be moral creatures, and this is what has enabled our species to work together and spread to every corner of the globe.

But evolution often takes shortcuts. It often only makes things ‘good enough’ rather than optimising them. I mentioned we evolved an upright stance, but even that was not without cost. Just ask anyone over the age of 40 years about their knees or lower backs.

Evolution’s ‘good enough’ solution for how to make us be nice to each other tens of thousands of years ago was to appropriate the way we evolved to perceive the world. For example, when you look at a ripe strawberry, what do you see? I’m guessing that for most of you – namely if you are not colour blind – you see it as being red. And when you bite into it, what do you taste? I’m guessing that you experience it as being sweet.

However, this is just a trick that our mind plays on us. There really is no ‘redness’ or ‘sweetness’ built into the strawberry. A strawberry is just a bunch of chemicals arranged in a particular way. It is our eyes and our taste buds that interpret these chemicals as ‘red’ or ‘sweet’. And it is our minds that trick us into believing these are properties of the strawberry rather than something that came from us.

The Scottish philosopher David Hume called this “projectivism”, because we project our subjective experience onto the world, mistaking it for being an objective feature of the world.

We do this in all sorts of contexts, not just with morality. This can help explain why we sometimes mistake our subjective opinions for being objective facts. Consider debates you may have had around the merits of a particular artist or musician, or that vexed question of whether pineapple belongs on pizza. It can feel like someone who hates your favourite musician is failing to appreciate some inherently good property of their music. But, at the end of the day, we will probably acknowledge that our music tastes are subjective, and it’s us who are projecting the property of “awesomeness” onto the sounds of our favourite song.

It’s not that different with morality. As the American psychologist, Joshua Greene, puts it: “we see the world in moral colours”. We absorb the moral values of our community when we are young, and we internalise them to the point where we see the world through their lens.

As with colours, we project our sense of right and wrong onto the world so that it looks like it was there all along, and this makes it difficult for us to imagine that other people might see the world differently.

In studying the story of human physical, psychological and cultural evolution, I learnt something else. While this is how evolution shaped our minds to see right and wrong, it’s not how morality has actually developed. Even though we’re wired to see our particular version of morality as being built into the world, the moral rules that we live by are really a human invention. They’re not black and white, but come in many different shades of grey.

You can think of these rules as being a cultural tool kit that sits on top of our evolved social nature. These tools are something that our ancestors created to help them live and thrive together peacefully. They helped to solve many of the inevitable problems that emerge from living alongside one another, like how to stop bullies from exploiting the weak, or how to distribute food and other resources so everyone gets a fair share.

But, crucially, different societies had different problems to solve. Some societies were small and roamed across resource-starved areas surrounded by friendly bands. Their problems were very different from those of a settled society defending its farmlands from hostile raiders. And their problems differed even more from those of a massive post-industrial state with a highly diverse population. Each had their own set of challenges to solve, and each came up with different solutions to suit their circumstances.

Those solutions also changed and evolved as their societies did. As social, environmental, technological and economic circumstances changed, societies faced new problems, such as rising inequality, conflict between diverse cultural groups or how to prevent industry from damaging the environment. So they had to come up with new solutions.